Abstract

This article systematically assesses the likelihood of effective implementation of several key options to reduce global biodiversity loss, including ‘conventional’ biodiversity policies, such as expanding protected areas, and policies primarily developed for other purposes but with potential positive side effects for biodiversity, such as ambitious climate change mitigation efforts, forest protection, and sustainable fishing practices. While existing studies highlight the technical feasibility of implementing such policy options, their political feasibility is rarely considered in detail. Political feasibility refers to the constraints that either make agreement on policies difficult in the first place for limit or prohibit the effective implementation of agreed policies. Drawing on a broader research project that models the effectiveness of international environmental regimes based on the robust findings of regime theory, we utilize a novel assessment framework to study the political barriers and opportunities to the implementation of biodiversity policies at the global level. The analysis suggests that focusing on those options that are technically less ambitious is more likely to be implemented in the short term. In conclusion, the article highlights the importance of analyzing the institutional and governance-related aspects of policies to reduce biodiversity loss.

1. Introduction

Biodiversity loss has both local implications and inherently global dimensions, requiring global solutions (Swanson Citation1995). Models of biodiversity loss show a decline in vertebrate populations by nearly one third since 1971 and indicate that among ‘selected vertebrate, invertebrate and plant groups, between 12% and 55% of species are currently threatened with extinction’ (CBD Secretariat Citation2010, p. 24, 26). Increased understanding of the importance of biodiversity across multiple dimensions indicates that the damages caused by these trends are widespread and severe. Consequently, loss of biodiversity threatens to, inter alia, negatively affect the tourism industry, leading to lowered agricultural productivity through lowered soil fertility and disruptions of insect crop pollination; reduce global fish catches; complicate natural hazard management; lead to the destruction of genetic resources that are of value for medicine, agriculture, and ecosystem resilience; and destroy biodiversity that is of invaluable cultural significance for many societies (UNEP Citation2007; OECD Citation2008; CBD Secretariat Citation2010). The economic implications of biodiversity loss are estimated at potentially hundreds of billion US$ (UNEP Citation2007, p. 161). Furthermore, the poorest people are likely to suffer disproportionately due to a greater dependence on local ecosystems for livelihood security (UNEP Citation2007, p. 158; OECD Citation2008; CBD Secretariat Citation2010). The direct and indirect drivers of biodiversity loss are projected to continue largely unabated in the coming decades.

These developments have encouraged an increased focus on policy options to effectively address biodiversity loss. In the words of Global Biodiversity Outlook (CBD 2010):

Well-targeted policies focusing on critical areas, species and ecosystem services are essential to avoid the most dangerous impacts on people and societies. Preventing further human-induced biodiversity loss for the nearterm future will be extremely challenging, but biodiversity loss may be halted and in some aspects reversed in the longer term, if urgent, concerted and effective action is initiated now in support of an agreed long-term vision.

Such studies are part of a broader attempt to develop scenarios of biodiversity loss and to model the effects of different policies to address it (e.g., Alkemade et al. Citation2009). However, while many of the suggested strategies are technologically and economically viable, they are not always politically feasible. Political feasibility refers to the constraints that either make agreement on policies difficult in the first place or limit or prohibit the effective implementation of agreed policies. Furthermore, in contrast to modeling and scenario-building, studies on political feasibility and implementation (and particularly attempts at modeling this) remain limited. This paper addresses these research lacunae by systematically evaluating the potential effectiveness of those four strategies for addressing global biodiversity loss that already have been agreed upon by international or transnational actors (as opposed to those potential strategies for which no current cooperative structure exists, such as inducing global dietary changes). The four concrete institutions analyzed in this paper, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), also provide a balanced assessment in terms of international and transnational governance initiatives.

By applying an assessment framework detailing the factors that affect the effective implementation (and thereby also indirectly the potential effectiveness) of cooperative agreements to address biodiversity loss, this paper has two concrete aims: first, it illustrates the added value of using a formalized assessment framework (building on political science and International Relations scholarship) to evaluate the political feasibility of policy options (in addition to existing analyses that focus only on the technical feasibility); second, this paper examines which of the four already existing strategies scores highest in terms of effective implementation. Based on an application of our assessment framework to the four concrete options, we contend that the strategy that is currently most feasible is expanding protected areas (by intensifying implementation of the work of the CBD on protected areas), although its contribution toward reducing global biodiversity loss may be modest. In addition, we also argue that a generic trade-off exists between international approaches that have a higher potential impact (as they are universal in their reach) and transnational approaches that have fewer barriers toward effective implementation but a lower level of ambition. In sum, our paper highlights the importance of analyzing the institutional and governance-related aspects of policies to reduce biodiversity loss – at both international and transnational levels – and thereby contributes to the broader quest for effective governance strategies for combating biodiversity loss within the context of global environmental change (e.g., Kenward et al. Citation2011).

The next section will outline our assessment framework, focusing on factors that support or hinder successful implementation of international and transnational policies. Section 3 provides a detailed assessment of the four concrete cases in terms of their likelihood of implementation. Section 4 discusses implications of our findings.

2. Assessment framework: building on international regime theory

Effectively addressing global biodiversity loss will require significant behavioral, technological, and institutional change. However, not all potential strategies of achieving such change are equally realistic to be implemented. Thus, the framework outlined below assesses the likelihood of implementation of different strategies for reducing global biodiversity loss. Drawing on the international regime literature (a subfield of the discipline of International Relations), the framework identifies factors that have a positive influence on implementing agreed upon policies (what we refer to as regime implementation). A detailed version of the analytical framework applied in this article can be found in Dellas et al. (Citation2011) and de Vos and colleagues (2013). As a consequence of the choice of academic literature underlying our framework, we focus only on those strategies that need to be implemented through international or transnational cooperative action (as opposed to strategies that potentially could be implemented by actors unilaterally). This is justified, first, by the global aspiration of biodiversity conservation. Given the pervasive nature of biodiversity loss, its geographic spread, and the underlying drivers, actions by individual states will not be sufficient to substantially reduce biodiversity loss. Second, as all policies suggested have potential impacts on markets and competitiveness (PBL Citation2010), it is highly unlikely that states would pursue costly biodiversity policies unilaterally, instead of attempting to reach an international agreement that would level the playing field. Consequently, this paper assumes that the strategies to reduce loss in MSA will be realized through international or transnational cooperation (in the form of successful formation and implementation of an international or transnational regime), although other alternative strategies at sub-national, national and regional levels are also theoretically conceivable (see, e.g., Smith et al. Citation2003). In the empirical analysis, we focus both on regimes that are public (agreements formed among states) and those that are private (agreements formed among non-state actors).

An international regime can be understood as the formalized rules and norms that govern the behavior of actors in the international system within a given issue area (Krasner Citation1983).Footnote1 The academic literature on international environmental regimes provides numerous hypotheses regarding factors that increase or diminish the likelihood of effective regime implementation (Bernauer Citation1995; Sprinz & Helm Citation1999; Breitmeier et al. Citation2006). The framework summarized below synthesizes and integrates these findings into a formalized set of rules, which allows the analyst to assess the likelihood of implementation of policies (for a comprehensive discussion of scientific findings on regime implementation, see Dellas et al. Citation2011).Footnote2

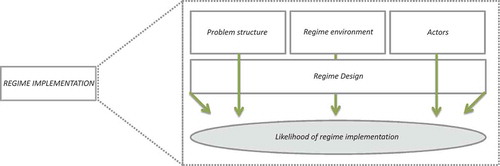

During the regime implementation stage, four characteristics define the likelihood of effective regime implementation: the attributes of the environmental problem to be regulated (problem structure); the constraints and autonomy of the negotiating parties and the addressees of the regulations, e.g., economic sectors (labeled actors); other institutions, organizations, and norms in the wider international system that influence the actors’ preferences (regime environment); and the components of the institutional structure (regime design). An overview of the framework can be found in . Assuming that these four building blocks are favorable, regime implementation (i.e., potential effectiveness of the regime) will be more likely than under unfavorable conditions.

Before the following subsections discuss each of these conceptual building blocks in more detail, we briefly reflect on the limitations of our assessment framework. First, while the issues examined under each conceptual building block follow from robust findings of international regime literature, they remain products of interpretation. Hence, different experts might disagree on the nuances. Second, it is important to note that the literature surveyed for this paper is not a completely coherent body of scholarship in itself. Rather, it incorporates a wide range of underlying purposes and meta-theories that require the analyst to make interpretations. Third, not all relevant literatures on cooperation between actors (such as economic or psychological theory) have been incorporated. The concepts included here are derived from a limited and clearly defined field of research on international institutions, thus guaranteeing a minimum coherence in terms of underlying ontological and epistemological assumptions. We, however, acknowledge that our theoretical bias toward neoliberal institutionalism (regime theory) excludes other plausible accounts of the likelihood and effectiveness of international cooperation. Fourth, the factors included in this paper are by no means meant to be conclusive, but rather represent a preliminary list that could be expanded or refined. The relation of the different factors to each other is also not set in stone and needs to be examined further; for example, we currently lack information on the weighting of different variables, and therefore this paper assumes that all factors are equally important. Finally, it is important to emphasize that our assessment framework does not examine whether the rules implemented by a regime are sufficiently stringent for a significant impact on the problem that led to its creation. The following sections outline the building blocks of the assessment framework in more detail.

2.1. Problem structure

Environmental problems have different attributes, degrees of difficulty, and complexity. Consequently, different problem types call for different solutions. Scholars have identified various characteristics of problem structure that have implications for regime formation and implementation (Young Citation1999; Miles et al. Citation2002; Hovi et al. Citation2003). This section provides a short description of some of the key characteristics of problem structure that our framework examines.

First, problems can be distinguished as either collaboration or coordination problems. Collaboration problems exist in situations where the costs and benefits of a problem and its potential solutions are unevenly distributed in favor of some actors (Underdal Citation2002, p. 20). Characteristic examples of such cases are problems of transboundary pollution, or common-pool resources. Often, a country that pollutes neighboring ones only pays a part of the costs, but enjoys all the benefits. Such characteristics make reaching agreement on how to address a collaboration problem, and ensuring compliance, difficult. Coordination problems, on the other hand, still require cooperative efforts, but with the difference that actors’ preferences and interests converge. Typical examples of such problems are measures to control air or marine traffic (Underdal Citation2002).

Second, problems can be distinguished as either systemic or cumulative environmental problems. While the activities causing systemic problems do not necessarily take place at a global scale, their physical impacts are global. Emissions of greenhouse gases or ozone depleting gases are, thus, systemic environmental problems; although the emission of these gases is asymmetrically distributed throughout the world, they spread throughout the whole atmosphere. Conversely, the causes of cumulative problems are local in nature but widely replicated, thus leading to a change in the overall environment (Turner et al. Citation1990). The regime literature suggests that implementation of regimes tackling cumulative problems may be less successful, since the lack of immediate cross-border implications makes the detection of noncompliance less likely. Conversely, noncompliance with the provisions of regimes tackling systemic environmental problems has global impacts.

And, third, the regulation costs actors face complying with the rules of a regime are an important explanation for how difficult it is to solve the environmental problem (e.g., Barrett Citation1999; Biermann & Siebenhüner Citation2009). Solutions to some problems can have significant environmental benefits at relatively low cost, whereas in other cases the cost of action is high and the environmental benefits are less clear, thus deterring actors from regime formation and implementation. However, regulation costs are not fixed, as, for example, technological innovations can reduce regulatory costs. Conversely, prolonged inaction may lead to an increase in the costs of reversing the damage.

2.2. Actors

The interests and power of actors are often seen as important factors in explaining the operation of international regimes. This section presents some key actor-centered characteristics for regime implementation found in the literature. Asymmetry of interest between actors that are significant for causing or addressing a problem can hamper regime implementation by diminishing participation in the regime (Underdal Citation2002, p. 17–20).

It is important to differentiate between participation by states that are powerful and states that are important for the creation of a regime governing a particular issue due to their stake in the cause and/or solution of the problem.Footnote3 For example, in the case of the International Whaling Commission, participation by traditional or aboriginal whaling states was definitely important for addressing the problem of whaling (Andresen Citation2002). However, not all of these states can necessarily be considered powerful. Not only the support of powerful or important states can encourage regime implementation, but also the participation of high-level ministerial representatives from the negotiating countries rather than lower-level delegates at conferences of the parties (COPs), as political pressure on decision-makers is maintained (Skjærseth Citation2002, Citation2006).

Furthermore, when multiple economic sectors need to be regulated to address an environmental issue, this may affect regime implementation negatively. This is because ‘transsectoral problems require concerted action among relevant public authorities both horizontally, and vertically’ (Skjærseth Citation2002, p. 179). Several agencies and ministries may be affected by the task of regulating the issue and have to coordinate amongst each other, in addition to the relevant ministries of other countries.

2.3. Regime environment

The embedding of a regime in a larger institutional framework increases the likelihood of regime implementation. Furthermore, institutional interplay may have positive or negative implications for regime implementation. In the case of most environmental regimes, some interaction exists with other institutions, in particular, as the number of institutional arrangements addressing environmental and other issues is increasing. Institutional interplay can be negative, for example, when the provisions of regimes contradict each other, as is the case with the climate change and the ozone depletion regimes (Young Citation2008, p. 123, 124). However, interplay can also be positive and reinforce the activities of a regime, particularly when they are working on similar issues.

2.4. Regime design

Following this review of the context variables, this section will discuss six variables associated with ‘regime design’, which plays an important role in regime implementation. First, since many environmental problems are characterized by high scientific uncertainty, improved scientific understanding could encourage improvements in the way the problem is managed or solved. Therefore, the extent to which a particular regime promotes scientific knowledge generation can have an indirect, albeit significant, impact on regime implementation by encouraging behavioral and policy changes, which can in turn lead to the solution or improvement of the environmental problem (Andresen et al. Citation2000; Mitchell Citation2008). Such knowledge generation typically occurs through large-scale international scientific assessments, such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). However, Mitchell et al. (Citation2006) indicate that the influence of such assessments also varies according to whether its intended audience considers the assessment to be salient, credible, and legitimate. Another dimension of knowledge generation is the promotion of public awareness, thus raising the salience of the problem on global and national policy agendas.

Second, while full compliance does not guarantee success at attaining environmental improvement (for example, if the goals of a regime are rather unambitious or if not all major contributors to an environmental problem participate in a regime) (Mitchell Citation2008), strong compliance mechanisms are generally considered important for regime implementation. The strength or weakness of regime compliance mechanisms can be ranked in three levels. At the weakest level, there is no compliance mechanism. At an intermediate level, each party establishes a mechanism for monitoring regime implementation. Finally, a strong compliance mechanism not only monitors implementation, but also has the authority to apply sanctions on non-compliant parties (Young Citation1999, p. 88–97).

Further issues that are important for compliance and compliance mechanisms are the precision of the rules established by the regime, as well as to what extent they are legally binding. Therefore, scholars have also worked on evaluating to what extent a regime leaves room for interpretation regarding the goals and targets that are to be achieved, and whether the conditions of obligation are explicit (Abbott et al. Citation2000).

Third, positive incentives or side-payments can also be important aspects of regime design by helping states to comply with its rules. Positive incentives are particularly important in cases of involuntary noncompliance, when states are willing to comply but lack the necessary capacity to do so. They can have the form of financial assistance, transfer of technological expertise, or other bilateral assistance outside the framework of the treaty, and have been included in various agreements such as the Montreal Protocol, the Kyoto Protocol, and the CBD (Brown Weiss & Jacobson Citation1998). Fourth, differentiation of rules may also contribute to increased regime implementation by allowing rules to be adapted for the different capacities and responsibilities for an environmental problem of actors.

Fifth, mechanisms for reporting and implementation review allow parties to international agreements to exchange data, monitor activities, assess the adequacy of commitments, and handle poor implementation (Victor et al. Citation1998). Such mechanisms are, thus, also important for monitoring compliance and deciding on adequate measures in cases of noncompliance. Sixth, and finally, a strong secretariat can be central to the regime’s implementation. To be characterized as strong, it has to be autonomous in developing policies and have adequate financial resources (Biermann & Siebenhüner Citation2009).

This list of factors explaining effective implementation of international and transnational environmental regimes should not be considered conclusive. However, we have decided to include only factors that are relatively straightforward to observe and verify. Not addressed here, due to a lack of unambiguous evidence, are: participation by stakeholders (e.g., nongovernmental organizations – NGOs), decision rules, cumulative or crosscutting cleavages, relative strengths of pushers and laggards during negotiations, and transaction costs. When analyzing the different factors, we differentiate between those that act as barriers to effective regime formation and implementation, those that are ambiguous due to insufficient data or could work in multiple directions, as well as those that are predicted to have a positive effect on influencing effective regime implementation to reduce biodiversity loss.

The following section will apply the assessment framework to several cases of existing international and transnational cooperation where full implementation could have significant benefits for reducing biodiversity loss. The application of the framework allows us to identify which cases have the highest likelihood of successful implementation and therefore should be prioritized politically.

3. Assessing options for reducing global biodiversity loss

A significant reduction of biodiversity loss of 50% by 2050 requires full implementation of all the strategies outlined in Section 1. In the case of some of these strategies, such as changes in agricultural practices to increase productivity and reduce post-harvest losses and changing diets toward less meat-intensive consumption patterns, concerted action at the international level is thus far lacking. Thus, these are cases where regime formation still has to take place. However, for the other strategies discussed in Section 1, international cooperation is already somewhat more established. For example, expansion of protected areas is a priority of the CBD, making marine fishing efforts more sustainable and improving forest management are the goals of certification schemes such as the MSC and FSC, and climate change mitigation is mandated under the UNFCCC. Our framework does not examine the actual impact of these agreements on biodiversity, but whether the context and design variables relating to this regime indicate a high potential likelihood of implementation. Furthermore, the level of ambition of these institutions does not correspond to what research has identified as necessary for a significant contribution to reducing global biodiversity loss (see below for an overview of these schemes and their ambitions). Nonetheless, these institutions will be discussed here because these instruments are the most congruent with the corresponding strategy to reduce biodiversity loss. Comparing their likelihood of successful implementation allows us to, first, test our assessment framework, and second, identify which strategies are most likely to be implemented (and thus contribute to reducing biodiversity loss) and why. This allows us to suggest priorities in addressing biodiversity loss and what may need to be done to overcome barriers to implementation.

Table 1. Overview of agreements.

Table 2. Overview of barriers to regime implementation.

provides an overview of the four cases included in this analysis and the corresponding barriers and opportunities to implementation identified in each case. The MSC and FSC have fewer favorable conditions (indicated by factors colored in green) than the UNFCCC and CBD. Overall, fewer factors are listed for the MSC and FSC, as some information is not available or some categories do not apply. Both the UNFCCC and CBD have regime designs that are favorable (e.g., rule differentiation, scientific knowledge generation). While the CBD is also characterized by a number of neutral or ambiguous (yellow) factors, the UNFCCC is hampered by several clearly unfavorable (red) factors, mostly related to the problem structure and actor interests. Thus, overall, the CBD’s program on protected areas emerges as the option that is most feasible to be implemented. The following paragraphs will shortly discuss the key findings for each case (note that not each category listed in the table is discussed in the paragraphs below).

3.1. Sustainable forest certification – likelihood of effective regime implementation

A number of international programs and institutions have worked on the formulation of common principles and commitments on improved forest management, although the implementation of these commitments remains limited (Visseren-Hamakers & Glasbergen Citation2007). However, substantial attempts to implement sustainable forest management practices have occurred in the context of voluntary market-based forest certification (Gulbrandsen Citation2008). Thus, this section considers what factors encourage or hinder the implementation of voluntary certification schemes.

3.1.1. Barriers to implementation

According to the assessment framework, three concrete barriers to implementation of forest certification as a biodiversity policy exist: the collaborative and cumulative nature of the problem (forest degradation and deforestation) and the negative interplay with other environmental institutions, in particular climate change and biodiversity related.

3.1.2. Ambiguous factors

While asymmetry of interest among key actors is a clear barrier to implementation of voluntary forest certification schemes, at least to a limited extent current forest certification schemes allow for differentiation of rules, which may attenuate this. Thus, forest owners are able to choose between different certification standards. For example, FSC Germany and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) Germany have been found to have very different rules regarding issues such as pesticide use, choice of species for replanting, and requirements for setting aside forest areas (Rametsteiner & Simula Citation2003). And, in some cases, certification schemes specify only overarching, guiding standards, leaving the details to be hammered out by national committees to be sensitive to national differences (an example of such an umbrella standard is the PEFC). However, while such differentiation may be attractive for some reasons (e.g., to preserve the rights of access to a forest by indigenous groups), it may also undermine some of the benefits of forest certification. For example, the PEFC, which allows national committees to define the details of certification criteria, is also frequently criticized for enabling forest companies to choose standards that are less stringent than those promoted by the FSC (Gulbrandsen Citation2005, p. 43, 46; Chan & Pattberg Citation2008).

A potential drawback for certification schemes is the lack of a strong compliance mechanism. Certification schemes do check for compliance. Indeed, it has been argued that voluntary forest certification schemes such as the FSC and PEFC are in some cases better at ensuring compliance than national authorities, as in ‘most tropical countries, forest legislation is poorly enforced outside certified forests’ (van Bueren Citation2010, p. 11). However, while some certification schemes such as the FSC have rather stringent compliance checking procedures, forest certification schemes ‘lack the traditional enforcement capacities associated with the sovereign state’ (Bernstein & Cashore Citation2004, p. 33, 23). Thus, while they can refuse to grant or revoke certification in case of noncompliance, forest certification schemes do not possess any sanction mechanisms and therefore lack a ‘strong’ compliance mechanism. Nonetheless, for the forestry companies that voluntarily subject themselves to the certification process, having their certification suspended as a sanction for noncompliance may be a substantial compliance mechanism, as the ‘reward’ of certification may improve their reputation or allow them to charge a price premium for their products (Gulbrandsen Citation2008).

Rule precision is a further ambiguous factor with respect to forest certification implementation. To be conducive to reducing global biodiversity loss, the standards and indicators used by the certification schemes must be clear and measurable, in particular also those pertaining to biodiversity conservation. Many forest certification schemes are well developed, with clear criteria and indicators. However, these criteria are not necessarily concerned with biodiversity conservation, thus there may be a need to emphasize ‘clarity and consistency to ensure that biodiversity conservation requirements are not diluted’ (van Bueren Citation2010; Zagt et al. Citation2010, p. vii).

3.1.3. Positive factors

The limited number of economic sectors directly involved in forest certification is considered a positive factor for implementation. In addition, as multiple certification schemes exist that cater for different constituencies within the overall economic sector of forestry (e.g., the FSC being favored by environmental interests, while the PEFC is endorsed by forest owners), barriers to implementation due to divergence of actors’ interests are very low.

With respect to problem structure, regulation costs have been found to have a limited impact on the likelihood of implementation of forest certification. While some studies have highlighted the negative implications for small holders and actors in the developing countries more generally (Pattberg Citation2006; Dingwerth Citation2008), the overall continuous growth of certified forest area around the world indicates that regulation costs are not a major obstacle toward implementation.

Mechanisms for regular reporting and implementation review also increase the likelihood of regime implementation. This is part of the regular procedures of many forest certification schemes; For example, the FSC regularly checks whether a certified forestry continues to comply with its standards (van Kuijk et al. Citation2009, p. 20).

In sum, our assessment indicates that voluntary forest certification is an issue marked by much ambiguity, resulting from the diversity of certification schemes, lack of rule precision, and inability to adequately sanction noncompliance, despite good monitoring mechanisms and relatively low regulation costs.

3.2. Sustainable fisheries certification – likelihood of effective regime implementation

This section examines the likelihood of implementation of sustainable fisheries certification. Overexploitation and depletion of marine fish stocks has substantial implications for marine biodiversity. It has therefore been suggested that a feasible way to address this issue is to reduce fishing efforts to maximum sustainable yield (MSY) levels, and compensate for the reduction in fish catches by additional aquaculture (PBL Citation2010). Many existing fisheries organizations and instruments are far from the ambition of the recommendation to reduce fishing efforts to MSY levels (for example, some Regional Fisheries Management Organizations conduct research, provide loose guidelines, or establish protected areas, but do not establish and monitor sustainable catch levels). Others focus only on specific species, families, or orders (such as tuna, salmon, and whales), or on fisheries in specific regions (such as the Mediterranean or South Pacific). Considering this discrepancy with the option to reduce catch levels to MSY levels immediately or in the near future, this section examines implementation of voluntary fisheries certification schemes, such as the MSC. Certification schemes such as the MSC operate globally and certify the sustainable fishing practices of any wild capture fishery. The number of public and private, international, regional, and national fisheries certification schemes has been estimated at ‘400 and rising’ (FAO Citation2008, p. 26), indicating the increasing popularity and proliferation of this marine fisheries certification as a strategy to combat overfishing (Kalfagianni & Pattberg Citation2013).

3.2.1. Barriers to implementation

While rule precision may contribute to implementation, inaccuracy and lacking precision of rules is often criticized by many of the currently active marine fisheries certification schemes (Accenture Citation2009). In some cases, this makes measurement and verification of the criteria open to interpretation, and may encourage ‘arbitrary ecolabeling decisions’ (Sainsbury Citation2010, p. 1). Clearly, a problem that certification schemes need to address in the future is to develop rules that are both precise and flexible enough to be applied to both small- and large-scale, developed and developing country fisheries.

With respect to regime environment, one issue that may hinder implementation is negative interplay with other regimes. In the case of fisheries certification, the potential negative interactions with the World Trade Organization (WTO) have received significant attention, as the certification standards may be discriminatory (e.g., if the high cost of demonstrating compliance with them prohibits smaller fisheries or fisheries from poorer countries to apply), and thus may also create obstacles to trade (FAO Citation2008, Citation2010; Accenture Citation2009). Furthermore, it has been argued that the standards of private certification organizations may reproduce similar rules already required by the authorities in the exporting or importing countries (FAO Citation2008, p. 96). Nonetheless, there have been substantial efforts to ensure that certification standards are not discriminatory to products from particular countries or producers.

3.2.2. Ambiguous factors

With respect to regime design, one factor that may mitigate the asymmetry of non-state interests discussed above is differentiation of rules. Actors interested in certification can choose between different eco-labels that differ in terms of the level of rigor, consistency of testing, and even the issues that are certified (for example, issues that are examined may include the ecological sustainability of fisheries and ecosystems, traceability of certified products through the supply chain, fair trade, workers’ rights, and/or environmental impact assessments such as carbon footprint (Accenture Citation2009)). Not only are products certified by different eco-labels necessarily comparable, but also fisheries seeking the benefits of labeling may also be able to choose between different certification schemes that focus on criteria that are easiest for them to fulfill. This type of (not necessarily intentional) differentiation of rules is thus not wholly desirable, however, efforts to address this situation do exist, e.g., through the guidelines for marine capture fisheries eco-labeling developed and refined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Fisheries and Aquaculture Department since 2005 (Sainsbury Citation2010, p. iv).

A further aspect of regime design that is ambiguous in the case of fisheries certification schemes are side-payments. While voluntary certification is currently not associated with any systematic provision of side-payments, the FAO supports the provision of ‘funding to support eco-label certification in developing States’, where fisheries may face more significant financial obstacles to meeting the sustainability criteria of certification schemes, and moreover in demonstrating their adherence to those criteria (Sainsbury Citation2010, p. 28).

With respect to regime design, a strong compliance mechanism is a further component of successful regime implementation, particularly in the case of collaboration problems. In the case of voluntary fisheries certification, compliance works somewhat differently than in the context of formal, legally binding international agreements. Thus, compliance with the criteria of a standard is assessed by a second- or, ideally, a third-party actor. Furthermore, in the case of the MSC, for example, fisheries are also regularly re-assessed and monitored to ensure ongoing compliance with sustainable fishing criteria (Sainsbury Citation2010, p. 18). However, in many cases, the strength of compliance assessments is reduced by the fact that the sustainability assessments of many certification schemes rely on imprecise criteria (Accenture Citation2009). Moreover, a substantial weakness regarding compliance with fisheries certification is the general lack of sanctions and corrective measures (FAO Citation2008, p. 100).

3.2.3. Positive factors

Similar to the case of forest certification, the limited number of economic sectors involved in fisheries certification is a positive factor for implementation. The existence of multiple certification schemes catering for different constituencies that we observed in the forestry case is also visible in fisheries certification (Kalfagianni & Pattberg Citation2013). Therefore, barriers to implementation due to divergence of actors’ interests are very low.

With respect to problem structure, regulation costs for verifying and monitoring adherence to environmental and social standards are borne by the certification schemes and the fishing companies that wish to be certified. Although the cost of applying for certification and complying with the requirements of a standard might hinder a more widespread implementation of some standards, there are incentives to apply for standard certification as well (such as the possibility to charge a price premium or to use certification for promotional purposes). However, similar to the forest certification arena, regulation costs have been found to have a limited impact on the likelihood of implementation of fisheries certification. One indicator is the relatively high level of standard uptake within the fisheries sector. While all voluntary certification schemes account for 22% of the world’s fisheries, MSC alone certifies 12% (Kalfagianni & Pattberg Citation2013, p. 130).

In sum, our assessment indicates that voluntary fisheries certification is an issue marked by some barriers to implementation, such as the lack of rule precision and negative institutional interplay. Additional ambiguity can be identified with respect to the development of side-payments and compliance mechanisms, while rule differentiation has both positive and negative aspects to it. The two positive factors include the limited number of economic sectors involved and the low regulation costs.

3.3. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – likelihood of effective regime implementation

This section discusses the likelihood of regime implementation of the UNFCCC. The UNFCCC is an international treaty that broadly aims to contribute to a reduction and stabilization of greenhouse gas emissions by its signatories. As the name indicates, it is a framework treaty that itself does not specify greenhouse gas emissions reductions in detail. These were to be specified in subsequent protocols such as the Kyoto Protocol. This protocol specifies collective emissions reductions of six greenhouse gasses by at least 5% (relative to the 1990 baseline) for the Annex I countries. The UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol are not ambitious enough to limit greenhouse gas concentration at 450 ppm. Nonetheless, evaluating the likelihood of successful implementation of the Kyoto Protocol, based on the rules defined in the assessment framework, gives an indication of the issues that would need to be addressed by a more ambitious successor agreement to the Kyoto Protocol.

3.3.1. Barriers to implementation

With respect to the problem structure of climate change mitigation, the projected regulation costs are higher than those of any of the other strategies discussed in this report. Thus, estimates for stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations at 450 ppm range from 1% to 3% of global gross domestic product (GDP), or roughly 1200 billion US$ annually (UNEP Citation2008; PBL Citation2009), although implementing the Kyoto Protocol is significantly less costly. However, it has been emphasized that the cost of climate change mitigation rises significantly the longer action is delayed, and that even though spending 2% or 3 % of global GDP on climate change mitigation may seem high, global military spending is similarly high at 2.5% (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Citation2007; Stern Citation2007; UNEP Citation2008).

A further issue that may affect regime implementation negatively is the large number of economic sectors that is needed for effective regulation. For example, for the year 2000, the most significant contributions to greenhouse gas emissions were assumed to come from transportation, 13.5%; electricity and heat, 24.6%; land-use change, 18.2%; and agriculture, 13.5% (Baumert et al. Citation2005; UNEP Citation2008, p. 44). Thus, regarding the number of sectors that need to be regulated, this option also far exceeds the other strategies discussed in this paper.

Furthermore, implementation may be impeded by multiple dimensions of asymmetry of interest between powerful states and/or important states, involving issues such as the differing responsibilities and capabilities of states. Determining responsibilities and commitments for emissions reductions is not necessarily straightforward, and has been a consistent issue of contention from COP15, (COP15 was held in Copenhagen in 2009) when, for example, countries such as China and India were taken aback by the demands to make commitments to make emissions reductions as well, to the most recent COP18 (COP18 was held in Doha in 2012), where, for example, a second Kyoto Protocol commitment period was agreed on, but several countries that were previously included in the Kyoto Protocol refused to accept binding targets (Russia, Japan, and New Zealand) and one even completely refused to participate in a second commitment period (Canada). Asymmetry between states also exists in terms of their vulnerability to climate change, as well as their capacity to respond and adapt to it. Thus, developing countries ‘are especially vulnerable to climate change because of their geographic exposure, low incomes, and greater reliance on climate sensitive sectors such as agriculture’ (Stern Citation2007, p. 104).

With respect to regime design factors influencing implementation, the UNFCCC regime secretariat can be considered weak; while it has a substantial budget, its autonomy is limited as a consequence of the strong asymmetry of interest: ‘most parties do not want a strong and independent climate secretariat, which (…) possibly favours the interests of one group of parties over those of another’, and may have significant social and economic consequences for the affected countries (Busch Citation2009, p. 254). Considering the divergent interests of different parties, the climate secretariat has a difficult task finding a middle ground and is limited to being a ‘technocratic bureaucracy’ (Busch Citation2009, p. 260), and is reluctant to develop its own policy proposals (Biermann & Siebenhüner Citation2009, p. 329).

With respect to regime environment, the climate change regime is characterized by both positive and negative interplay. In addition to numerous possible direct interactions, for example, with the CBD (encouraging plantations under the Kyoto Protocol would be undesirable for forest biodiversity), more diffuse potential interactions exist as well, including for example that ‘trade liberalization advanced by the World Trade Organization (WTO) may lead to rising GHG emissions due to induced growth in international trade’ (Oberthür Citation2006, p. 56). Other interactions with WTO law were identified by Zelli and van Asselt (Citation2010). One potential area of interplay is the flexibility mechanisms in the Kyoto Protocol; thus, for example, the provisions on international emissions trading are directed at developed countries, and ‘could be considered a form of trade discrimination since it effectively excludes the large majority of developing countries as well as third parties to the Kyoto Protocol from emissions trading’ if emissions credits were considered to fall under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) (Zelli & van Asselt Citation2010, p. 81). Furthermore, various trade-related policies could be in conflict with WTO law, for example, government procurement policies permitted under the climate regime, and implemented to achieve emissions limitations, could also be in conflict with WTO rules on this issue (Zelli & van Asselt Citation2010, p. 83).

3.3.2. Ambiguous factors

The targets of the Kyoto Protocol are also legally binding, which is one aspect that increases the likelihood of regime implementation. However, as mentioned above, fewer countries accepted the second commitment period compared to the first one, significantly reducing the level of ambition.

3.3.3. Positive factors

While the problem structure of climate change mitigation may be complex, for example, characterized by strong interest asymmetry, the regime design scores well on many categories included in the assessment framework. For example, to address interest asymmetry, emphasis within the Kyoto Protocol and UNFCCC is generally placed on differentiation of rules, based on the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’ of states; for example, only Annex 1 countries committing themselves to greenhouse gas emissions reductions under the Kyoto Protocol.

Furthermore, regime design mechanisms that increase scientific knowledge generation, synthesis, and dissemination are likely to increase regime implementation. This is an area that has received significant amount of attention in the context of the climate regime, for example, through the establishment of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA). Furthermore, the bodies of the climate regime consult the scientific advice provided by the IPCC.

The Kyoto Protocol has a strong compliance mechanism. Article 18 calls on its signatories to define ‘appropriate and effective procedures and mechanisms to determine and to address cases of noncompliance with the provisions of this Protocol, including through the development of an indicative list of consequences, taking into account the cause, type, degree and frequency of noncompliance’. In particular, Annex 1 parties must comply with their emission targets and ‘the methodological and reporting requirements for greenhouse gas inventories’ (UNFCCC Citation2010, p. 1). These greenhouse gas inventories are not only a significant part of checking for (non)compliance, but are also part of the climate regime’s mechanism for regular reporting and implementation review, a further issue that is identified as contributing to an increased likelihood of regime implementation in the assessment framework. Greenhouse gas inventories are to be compiled using the agreed methodologies developed by the IPCC, and in a common format, to ensure comparability (Yamin & Depledge Citation2004, p. 333–338).

The implications of noncompliance involve parties having to make the missed emissions reductions in the following commitment period as well as an extra 30%, to present a compliance action plan, and its right to take part in emissions trading is temporarily suspended (UNFCCC Citation2010). Such compliance action plans and suspension of eligibility for emissions trading also apply to parties failing to comply with reporting requirements.

Side-payments also make regime implementation more likely, and in the Kyoto Protocol they are also intended to address the issue of different capabilities between states to implement an agreement and adapt to the problem of climate change. Thus, based on their emissions and capacity to cope, the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol ‘mandate financial and technological transfers from Parties with more resources to those less well endowed and more vulnerable’ (Yamin & Depledge Citation2004, p. 264). The paragraphs of Article 4 in the UNFCCC require the provision of financial resources to aid in implementation, reporting, adaptation, and technology transfer, while similar rules also apply under Article 11 of the Kyoto Protocol. While neither document specifies the amount of funding to be provided, this is to be specified in greater detail in subsequent agreements. Overall, side-payments generated through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) of the Kyoto Protocol (amounting to 22 billion US$ for climate change mitigation activities in developing countries between 2004 and 2008), have also been compared favorably to the funding mechanisms of other regimes, such as the CBD (UNEP/CBD/SP/PREP/1: 16).

With respect to regime environment, in addition to the negative regime interplay mentioned earlier, there is also a strong potential for positive interplay with other regimes. Thus, depending on how it is implemented, climate change mitigation can have significant positive effects for biodiversity protection. With respect to legal interactions with the WTO, Zelli and van Asselt (Citation2010, p. 84) have also identified possible positive interactions, such as ‘the removal of trade barriers in favour of climate-friendly goods or services, and the development and transfer of low-emission technologies’.

In sum, our assessment indicates that while the UNFCCC and its Kyoto Protocol are characterized by a favorable regime design, the problem structure is also far more problematic than in the other cases discussed here.

3.4. Convention on biological diversity’s protected area policy – likelihood of effective regime implementation

This section assesses the likelihood of regime implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity’s work on protected areas. Thus, while the success of the CBD regarding the different issues it addresses varies significantly, this paper focuses only on CBD work on protected areas, as this most closely reflects the strategy evaluated in PBL (Citation2010): expanding protected area coverage to 20% of all terrestrial ecoregions (for a review of the technical potential of protected areas, see Mora and Sale (Citation2011)).

The CBD encourages contracting parties to ‘establish a system of protected areas or areas where special measures need to be taken to conserve biological diversity’ and ensure adequate management of these protected areas (Article 8), targets which are elaborated on in several specific CBD programs. The CBD work on protected areas was reaffirmed in the new Strategic Plan for 2011–2020: target 5 calls for at least halving the rate of loss of all natural habitats, and where feasible bringing it close to zero, while target 11 supports coverage by protected areas for terrestrial inland, coastal, and marine areas by at least 17% and 10%, respectively.

3.4.1. Barriers to implementation

The problem structure of issues tackled by the CBD has several potentially obstructive characteristics. Thus, establishing protected areas tackles a cumulative problem that is furthermore also a collaboration problem. As mentioned earlier, the regime literature suggests that cumulative problems may face difficulties in regime formation, as well as implementation, since the lack of immediate cross-border implications makes the detection of noncompliance less likely. The fact that the costs and benefits of the problem and its potential solutions are unevenly distributed in favor of some actors is what furthermore makes this a collaboration problem (Underdal Citation2002, p. 20).

Some components of regime design are able to contribute to a higher likelihood of implementation, even where preconditions are problematic due to an unfavorable problem structure. For example, a strong compliance mechanism can contribute to implementation despite collaboration problems. Collaboration problems such as biodiversity loss are difficult to address because the incentives to cheat are strong for participants, as it is not visible in the short term, while cheating is just as beneficial as cooperation in the short term. In such cases, a strong compliance mechanism (i.e., one that imposes sanctions in cases of noncompliance) is likely to encourage more implementation. However, in the CBD, ‘sanctioning power is almost non-existent’ (Le Prestre Citation2004, p. 71; Siebenhüner Citation2009). While compliance review is possible through national reports (required by CBD Article 26) and National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs), which are the key implementation mechanisms of the CBD and its Strategic Plans (according to Article 6(a) of the Convention), several parties have not yet adopted NBSAPs (Prip et al. Citation2010, p. 1), and not all have handed in national reports.

3.4.2. Ambiguous factors

One aspect of the regime design of the CBD that makes effective compliance mechanisms and sanctions problematic is the lack of appropriate indicators for some of the goals specified in the Strategic Plans. Without sufficiently precise indicators, it is difficult to adequately determine the compliance with some of the targets. Thus, as has been highlighted recently, ‘the suite of internationally developed biodiversity and ecosystem service indicators is limited, and significant gaps exist’, in particular regarding genetic or ecosystem changes (UNEP/IPBES/3/INF/2: 6–7).

In cases where compliance mechanisms are weak, mechanisms for regular reporting and implementation review can contribute to effective regime implementation. With regard to the CBD, some improvements are possible in this area. Key instruments for reporting to the CBD are the national reports. However, not all parties to the convention consistently provide these, with national reports having been submitted by less than 150 countries (out of 193 signatories) by 2010 (CBD Secretariat Citation2010). Specifically for the CBD program of work on protected areas, an additional mechanism for reporting and implementation analysis is the gap analysis, which requires countries to assess whether ‘a protected area system meets protection goals set by a nation or region to represent its biological diversity’ (CBD Secretariat Citation2007, p. 1), and implement the necessary measures to address any existing regulatory gaps. Furthermore, recent discussions at COP10 indicate an increased interest in possible additional measures for implementation review, such as ‘voluntary peer review mechanisms’ (UNEP/CBD/SP/PREP/1: 16).

One potentially beneficial aspect of the CBD regime design is that it involves the possibility of side-payments. In the case of the CBD, side-payments take several forms, such as financial assistance and technology transfer. Specifically, side-payments are included in the CBD under Articles 15 (governing access to genetic resources), 16 (access to and transfer of technologies), 18 (technical and scientific cooperation), and 19 (handling of biotechnology and distribution of its benefits). Article 20 furthermore emphasizes the financing responsibility of developed countries which are obliged to provide developing countries with adequate financial support to meet the obligations of the Convention. Furthermore, pursuant to Articles 15 and 19 in particular, the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-Sharing emphasizes the fair and equitable sharing of benefits from the use of genetic resources. Overall, by focusing on far more than a traditional conservation approach, the CBD treaty ensures that ‘environmental and developmental interests were integrated to meet both the conservation interests of the North and the development interests of the South’ (Siebenhüner Citation2009, p. 266). Thus, by including side-payments in several articles and subsequent protocols, the likelihood of implementation of the CBD may be increased. However, as was emphasized at COP10, the necessary resource mobilization has in practice fallen short, with many parties identifying a lack of resources and economic incentives as key reasons constraining implementation (UNEP/CBD/SP/PREP/1: 15–16).

One last aspect of regime design that is ambiguous in the case of the CBD is precision of rules. The CBD is a framework treaty, thus it is a rather general document that lacks precise targets. The subsequent protocols, decisions, and recommendations provide more specific information on protected areas. Greater precision also comes in the form of strategic plans which provide clear targets and timetables. While there is little room for interpretation regarding these targets, the strategic plans and recent discussions at COP10 highlight the need for more precise indicators (UNEP/CBD/SP/PREP/1: 18). Thus, the current set of indicators measuring progress toward each target is sufficient to establish broad trends in biodiversity loss. However, as the Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 indicates, the degree of certainty is low or medium (or no indicators have been established at all) for 6 of the 15 indicators (CBD Secretariat Citation2010). Thus, precision of rules in the case of the CBD can be classified as medium.

3.4.3. Positive factors

While the problem structure of establishing protected areas faces significant barriers, one aspect is mostly favorable, namely the costs of regulation. While the costs of establishing protected areas can differ significantly depending on the quality, status and effectiveness of the protected areas and high estimates of the cost of effective protection of only existing protected areas indicate an annual cost of up to nearly 8 billion US$ (James et al. Citation2001; Bruner et al. Citation2004), the overall costs, even with an expansion of protected areas, are significantly lower than regulation costs of some of the other strategies that may have positive implications for biodiversity conservation. For example, the costs of achieving greenhouse gas stabilization at 450 ppm have been estimated at 1200 billion US$ annually for greenhouse gas reduction (PBL Citation2009, p. 13). Thus, while funding of already existing protected areas in developing countries is ‘consistently less than what studies estimate to be adequate’ (Bruner et al. Citation2004, p. 1121), overall regulation costs to ensure that current protected areas are not simply ‘paper parks’ and expand protected areas are far more attainable than regulation costs for some other strategies discussed in this paper. Furthermore, a consideration of costs of inaction or, alternatively, benefits of regulation suggests further incentives for regime implementation. Thus, protected areas provide significant values not only through the conservation of biodiversity, but also, for example, by supporting local livelihoods (TEEB Citation2009).

The CBD benefits from actor interests that are consistently favorable to the implementation of protected areas, as it is an issue whose regulation affects few economic sectors, making coordination among different ministries less problematic. Furthermore, asymmetry of interest between powerful and important states within the issue area is generally low, and therefore participation in the CBD is generally rather high. There are currently only four countries that are not parties to the convention: the United States, Andorra, the Vatican, and South Sudan (several countries with limited recognition are also not parties). Nonparticipation of the latter three is not significant for the implementation and expansion of protected areas. However, the fact that the United States has signed, but not ratified the treaty could have greater implications, as it can be considered both a powerful state and an important state within the issue area (due to its vast territory and many different ecoregions). Therefore, continued nonparticipation by the United States could hamper progress toward increasing protected areas by 20% of all ecoregions. However, the US nonparticipation is mostly based on the fact that the CBD turned out not to be a pure conservation treaty (an idea the United States strongly supported and that reflects existing measures in the United States), but that it also addressed issues of ‘equity and economic development’ (McGraw Citation2004, p. 11). In this area, the United States already has relatively strong policies in place, with, for example, 22.8% of its terrestrial and marine territory covered by protected areas, exceeding the CBD-protected area target.

Asymmetry of interest with respect to protected areas could also arise from the potential social, political, and economic implications of establishing protected areas. For example, depending on how they are implemented, protected areas could lead to the displacement of communities and loss of access to land and resources (Agrawal & Redford Citation2009). However, expansion of protected areas does not necessitate deeper lifestyle shifts such as changes in production and consumption patterns associated with problems such as climate change.

Some aspects of regime design may also further decrease the negative implications of asymmetry between actor interests. In particular, in the case of the CBD, differentiated rules are included to allow for this. Thus, Article 20(2) places a responsibility on developed countries to ‘provide new and additional financial resources to enable developing country Parties to meet the agreed full incremental costs to them of implementing measures which fulfill the obligations of this Convention’. Article 20(4) is an even more explicit differentiation of rules as it highlights that developing country parties are only obliged to implement their commitments to the extent that developed country parties implement their obligations to provide financial resources and technology transfer. Furthermore, not only are the regime rules differentiated, they are also legally binding, which contributes to effective regime implementation.

Other aspects of CBD regime design are also rather favorable to effective regime implementation. For example, the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA), established by CBD Article 25, can be seen as a mechanism for scientific knowledge generation, synthesis, and dissemination, thus supporting regime implementation. An ‘important function of SBSTTA is thought to be the socialization of delegates of developing countries and industrialized countries alike into the science and norms of the regime’, thus establishing consensual scientific knowledge (Le Prestre Citation2004, p. 85). Based on the scientific knowledge it produces and reviews, the SBSTTA has made more than 136 recommendations to the COP. The scientific information provided by the bodies of the CBD is furthermore ‘by and large seen as scientifically credible and politically neutral’ (Siebenhüner Citation2009, p. 270).

Additional regime mechanisms for scientific knowledge generation include the Global Biodiversity Outlook, which is a regularly published synthesis of the current knowledge on biodiversity and biodiversity loss. Furthermore, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) will be a mechanism similar to the IPCC, and could contribute significantly by synthesizing the vast available scientific information in the area, as well as supporting credibility, consensual scientific knowledge, and addressing knowledge gaps by conducting research (TEEB Citation2009). Considering these various mechanisms for scientific knowledge generation, this can be considered a strong characteristic supporting regime implementation in the case of the CBD.

Lastly, according to our framework, the likelihood of regime implementation is also increased by the presence of a strong, autonomous secretariat. In the case of the CBD, it seems that the Convention Secretariat neither has a very significant budget, nor is very autonomous, as it remains attached to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (while other treaty secretariats, such as the climate and desertification secretariats, are independent) (Siebenhüner Citation2009, p. 276). The implications of this attachment are that some important budgetary and staffing decisions, for example, are still often made by UNEP, although the secretariat has gradually increased its competences in these areas (Siebenhüner Citation2009). Despite this, the CBD secretariat is generally considered to be ‘small but effective’ (Siebenhüner Citation2009, p. 265). Indeed, in comparison to the secretariats of other treaties and international organizations such as the climate secretariat, for example, it stands out as having substantial cognitive and normative influence, by demonstrating its expertise, providing independent ideas and policy proposals (Biermann & Siebenhüner Citation2009, p. 328–333).

In sum, our assessment indicates that despite some factors with an ambiguous or clearly negative effect on regime implementation, overall, the likelihood of successful implementation is high.

4. Conclusions

Reducing and eventually halting biodiversity loss is one of the key challenges of environmental governance in the decades to come. Innovative policy options are urgently needed. However, while a range of strategies exist that have the technical potential to substantially reduce biodiversity loss, few of these options are also politically feasible. For a number of promising strategies, such as global dietary change, the prospects of cooperating at the international level are dim. Other potentially effective strategies for reducing biodiversity loss – such as climate change mitigation, expanding protected areas, and increasing sustainable forestry and fishing practices – could be pursued through already existing international and transnational environmental regimes. This paper has analyzed the potential of these existing institutions (CBD, UNFCCCC, FSC, and MSC) to contribute to reducing biodiversity loss.

Our analysis has indicated that effectively implementing a strategy on increasing protected areas through the CBD is the most feasible option, while substantial barriers to implementation remain in the case of the climate change regime and its biodiversity implications. Pursuing a reduction of biodiversity loss by focusing on sustainable forestry and fishing practices is also feasible, but in these cases, fewer positive factors could be identified.

The finding that the CBD protected area policy is the most likely to be implemented successfully is hardly surprising, considering that it is the only instrument explicitly targeting biodiversity concerns. However, it suggests that, despite discussions whether protected areas are an appropriate instrument for biodiversity conservation and protection (e.g., Agrawal & Redford Citation2009), this may still be the best instrument currently available. We may need better and carefully managed protected areas to avoid undesirable side effects. Nonetheless, our analysis suggests that in the short term, it may be best to focus on this instrument.

It is also worth noting that the ambiguous factors and barriers to implementation identified in all four cases are not necessarily static; In some cases, it is possible to modify the context variables and thus further increase the likelihood of regime formation or implementation. For example, in cases where the responsibility for a problem is distributed unequally among actors (or their capabilities to address the problem effectively), differentiation of rules can contribute to addressing such impediments. Thus, while the CBD protected areas program may be the most likely strategy to be implemented in the short term, other more far reaching strategies for reducing global biodiversity loss may become available in the long term, as problem structures and actor interests change over time.

This paper also provided a first test case for our assessment framework. While we acknowledge that the type of analysis that can be done with this framework is limited, and it is furthermore not equally suitable for all cases (for example, it is less applicable to cases of private-sector regulation, such as the FSC and MSC), we nonetheless believe that future options for reducing biodiversity loss should be assessed for their political feasibility and potential implementation. We also acknowledge that the framework currently lacks precise indicators for some of the variables, thus comparison of, e.g., regulation costs is relative to the cases studied, rather than based on a consistent measurement scale of high, medium, and low regulation costs. Nonetheless, the framework provides a useful starting point for comparing the political feasibility of different policy options to reduce biodiversity loss. While the ambition level is too low both at the international and transnational level, this study clearly demonstrates that well-crafted institutions matter. Improving them therefore becomes a key challenge for everyone concerned about the current state of biodiversity governance.

List of acronyms: CBD – Convention on Biological Diversity CDM – Clean Development Mechanism COP – Conference of the Parties FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FSC – Forest Stewardship Council GDP – Gross Domestic Product GHG – Greenhouse Gas GATT – General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade IPBES – Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services IPCC – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change MSA – Mean Species Abundance MSC – Marine Stewardship Council MSY – Maximum Sustainable Yield NBSAPs – National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans NGO – NonGovernmental Organization OECD – Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development PBL – Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency PEFC – Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification RIL – Reduced Impact Logging SBSTA – Subsidiary Body on Scientific and Technological Advice (UNFCCC) SBSTTA – Subsidiary Body on Scientific Technical and Technological Advice (CBD) TEEB – The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity UNEP – United Nations Environment Programme UNFCCC – United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change WTO – World Trade Organization

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues Jesper Berséus, Frank Biermann, Sofia Frantzi, Henk Hilderink, Peter Janssen, Marcel Kok, Arthur Petersen, and Martine de Vos for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Financial support by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency in the context of the project ‘Modelling Governance and Institutions for Global Sustainability Politics’ (ModelGIGS) is gratefully acknowledged.

Notes

1. Following recent scholarship in the field of global environmental governance, we assume that there is no qualitative difference between inter-governmental and non-state regimes.

2. The framework is structured along the common differentiation between the regime formation and regime implementation phase (Underdal Citation2002, p. 6). For this analysis, we only focus on regime implementation, assuming that an institutional framework already exists.

3. Note that this specific category does not apply to non-state transnational regimes such as the FSC and MSC discussed further below.

References

- Abbott KW, Keohane RO, Moravcsik A, Slaughter AM, Snidal D. 2000. The concept of legalization. Int Organ. 54:401–419.

- Accenture. 2009. Assessment study of on-pack, wild-capture seafood sustainability certification programmes and seafood ecolabels. Dublin: Accenture.

- Agrawal A, Redford K. 2009. Conservation and displacement: an overview. Conserv Soc. 7:1–10.

- Alkemade R, van Oorschot M, Miles L, Nellemann C, Bakkenes M, ten Brink B. 2009. GLOBIO3: a framework to investigate options for reducing global terrestrial biodiversity loss. Ecosystems. 12:374–390.

- Andresen S. 2002. The International Whaling Commission (IWC): more failure than success? In: Miles EL, Underdal A, Andresen S, Wettestad J, Skjaerseth JB, Carlin EM, editors. Environmental regime effectiveness: confronting theory with evidence. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press; p. 379–403.

- Andresen ST, Skodvin A, Underdal, Wettestad, J, editors. 2000. Science and politics in international environmental regimes: between integrity and involvement. New York (NY): Manchester University Press.

- Barrett S. 1999. Montreal versus Kyoto: international cooperation and the global environment. In: Kaul I, Grunberg I, Stern MA, editors. Global public goods: international cooperation in the 21st century. Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 192–219.

- Baumert KA, Herzog T, Pershing J. 2005. Navigating the numbers: greenhouse gas data and international climate policy. Washington (DC): World Resources Institute.

- Bernauer T. 1995. The effect of international environmental institutions: how we might learn more. Int Organ. 49:351–377.

- Bernstein S, Cashore B. 2004. Non-state global governance: is forest certification a legitimate alternative to a global forest convention? In: Kirton J, Trebilcock M, editors. Hard choices, soft law: combining trade, environment, and social cohesion in global governance. Aldershot: Ashgate Press; p. 33–64.

- Biermann F, Siebenhüner B. 2009. The influence of international bureaucracies in world politics: findings from the MANUS research program. In: Biermann F, Siebenhüner B, editors. Managers of global change: the influence of international environmental bureaucracies. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press; p. 319–349.

- Breitmeier H, Young OR, Zürn M. 2006. Analyzing international environmental regimes: from case study to database. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press.

- Brown Weiss E, Jacobson HK, editors. 1998. Engaging countries: strengthening compliance with international environmental accords. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press.

- Bruner AG, Gullison RE, Balmford A. 2004. Financial costs and shortfalls of managing and expanding protected-area systems in developing countries. BioScience. 54:1119–1126.

- Busch PO. 2009. The climate secretariat: making a living in a straitjacket. In: Biermann F, Siebenhüner B, editors. Managers of global change: the influence of international environmental bureaucracies. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press; p. 245–264.

- CBD Secretariat. 2007. Ecological gap analysis [Internet]. [cited 2010 Oct 20]. Available from: http://www.cbd.int/protected-old/gap.shtml

- CBD Secretariat. 2010. Global biodiversity outlook 3. Montreal: Convention on Biological Diversity.

- Chan S, Pattberg P. 2008. Private rule-making and the politics of accountability: analyzing global forest governance. Global Environ Politics. 8:103–121.

- Dellas E, Pattberg P, Berséus J, Frantzi S, Kok M, de Vos M, Janssen P, Biermann F, Petersen A. 2011. Modeling Governance and Institutions for Global Sustainability Politics (ModelGIGS): theoretical foundations and conceptual framework. IVM-Report W11/005. Amsterdam: Institute for Environmental Studies.

- De Vos M, Janssen P, Frantzi S, Pattberg P, Petersen A, Biermann F, Kok M. 2013. Formalizing knowledge on international environmental regimes: a first step towards integrating political science in integrated assessments of global environmental change. Environ Modell Softw. 44:101–112.

- Dimitrov R. 2003. Knowledge, power, and interests in environmental regime formation. Int Stud Q. 47:123–150.

- Dimitrov R. 2005. Hostage to norms: states, institutions and global forest politics. Global Environ Politics. 5:1–25.

- Dingwerth K. 2008. Private transnational governance and the developing world: a comparative perspective. Int Stud Q. 52:607–634.

- FAO. 2008. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Rome: FAO.

- FAO. 2010. Post-harvest losses aggravate hunger: improved technology and training show success in reducing losses. FAO [Internet]. [cited 2010 Oct 30]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/news/story/0/item/36844/icode/en/

- Gulbrandsen L. 2005. Explaining different approaches to voluntary standards: a study of forest certification choices in Norway and Sweden. J Environ Policy Plann. 7:43–59.

- Gulbrandsen L. 2008. Accountability arrangements in non-state standards organizations: instrumental design and imitation. Organ. 15:563–583.

- Hovi J, Sprinz DF, Underdal A. 2003. The Oslo-Potsdam solution to measuring regime effectiveness: critique, response, and the road ahead. Global Environ Politics. 3:74–96.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. Climate change 2007: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC.

- James A, Gaston K, Balmford A. 2001. Can we afford to conserve biodiversity? BioScience. 51:43–52.