Abstract

Threats to biodiversity from increasing populations and poverty has resulted in the use of investments in livelihoods support activities as economic incentives for natural resource and biodiversity conservation in Ghana. Examples of such activities include woodlots, beekeeping, snail breeding, and mushroom farming. In order to assess and evaluate the effectiveness of these activities as tools for conservation planning and resource allocation, it is essential to document their use for environmental conservation. This study presents a consolidated documentation of the use of livelihoods support activities for natural resource and biodiversity conservation in Ghana. This documentation includes the specific activities, the number of such interventions since they were first used until 2010, their geographical distribution in the country, and implementation strategies. The methods used in this study include thematic and chronological analysis of conservation project reports, interviews with project managers, collection of primary data on the specific activities, and focus group discussions with participants of livelihoods support activities in rural Ghana. Seventy-one different types of livelihoods support activities belonging to eight categories have been employed for conservation in Ghana since 1993. The majority of these activities were based on non-timber forest products. A chronological trend analysis indicated an increasing tendency to make livelihoods support activities part of conservation projects in Ghana. These activities have become very relevant to Ghana’s current collaborative policy because they are used to buy-in local support for natural resource and biodiversity conservation.

Introduction

Globally, increasing human populations and poverty have dramatically accelerated the degradation of biodiversity as well as the depletion of natural resources. This has precipitated the urgent need for economic incentives such as livelihoods support activities (LSAs) for natural resource and biodiversity conservation (McNeely Citation1988; United Nations Environmental Programme Citation2004; Ayoo Citation2008) in towns and villages located near protected areas.

The principal aim of investing in such activities was to induce local communities to mitigate their impacts on natural resources and biodiversity. As economic instruments for conservation, they are mechanisms that aim at changing behaviors of economic agents by internalizing costs to natural resource utilization (Ekpe Citation2012). For purposes of natural resource and biodiversity conservation, LSAs are usually local economic activities that are promoted and used to complement, and not to replace, other conservation strategies such as existing regulations, conservation education, and protection activities. Examples of such activities include woodlots, beekeeping, snail breeding, mushroom farming, and animal husbandry. LSAs used for conservation are usually funded by governments, non-governmental organizations, and under financial assistance in multi-lateral agreements with international organizations. In developing countries, such funds are usually small targeted grants and transfer payments designed to provide financial support for organizations involved in sustainable livelihoods and environmental conservation activities (United Nations Environmental Programme Citation2004). These funds are used to support local economic activities that have minimal environmental impacts, usually in communities located on the fringes of natural resource areas such as protected areas. These investments also aim to bridge the profitability gap between unsustainable activities and sustainable alternatives, and thus induce actors to conserve biodiversity or use its components in a sustainable manner (United Nations Environmental Programme Citation2004). Most LSAs involve more efficient use of natural resources to generate additional income but in a few cases they do not involve the use of natural resources (Tropenbos International Citation2005). From the perspective of recipient communities, LSAs are a form of compensation for limiting and/or restricting access to and exploitative rights to resources. In Ghana, conservationists have been employing investments in a number of LSAs for natural resource and biodiversity conservation purposes for some years now. These LSAs have significant social and political support. Consequently, they have become important conservation tools.

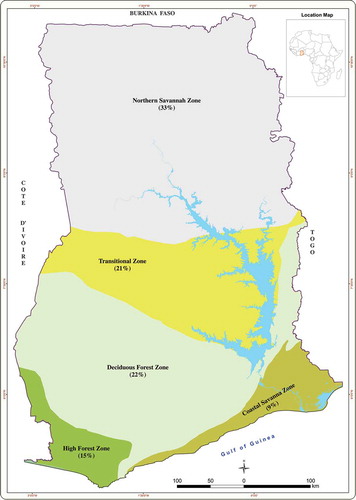

Ghana’s climate is tropical and the natural vegetation cover and its distribution over many areas of Ghana are closely related to the distribution of mean annual rainfall (Ntiamoa-Baidu et al. Citation2001). The vegetation formations include a coastal zone and a forest zone in the south, a transition zone in the mid-areas, and a northern savannah zone. There are two main types of forest zones: the high forest zone and deciduous forest zone. The high forest zone consists largely of evergreen forests and is located in the south west of Ghana. The deciduous forest zone is located in the central and southeastern parts of the country. The northern savannah occupies the largest area of about 45% of the land area; and the coastal savannah zone of covers the smallest area of about 5%. Land use in Ghana includes crop farming, forestry, cattle grazing, urbanization, protected areas, and tree plantations of cocoa, rubber, timber.

There is inadequate information on the biological resources in the marine and other aquatic systems in Ghana. However, so far, 2974 indigenous plant species, 504 fishes, 221 species of amphibians and reptiles, 728 birds, and 225 mammals have been recorded; with three species of frogs, one species of lizard, and 23 species of butterflies reported to be endemic to the country (Ministry of Environment and Science of Ghana Citation2002). About 16% of Ghana’s land surface area has been set aside to conserve representative samples of her natural ecosystems in the form of forest reserves, national parks, and wildlife reserves including various traditional forms of conservation (Ministry of Environment and Science of Ghana Citation2002). However, increasing pressure from agricultural expansion, mining, timber extraction and other economic activities have negatively impacted the biological resources of the country such that deforestation rate of about 22,000 ha annually in the early 2000s (Ministry of Environment and Science of Ghana Citation2002). The economic loss to the nation through deforestation and land degradation in the early 1990s has been estimated at about US$54bn, which was about 4% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (Tutu et al. Citation1993 as cited by Ministry of Environment and Science of Ghana Citation2002).

Before becoming a British Colony, natural resources in Ghana were managed through traditional land tenure systems. According to Kotey et al. (Citation1998), the current forest management policy of collaborative management has evolved through three main phases, namely the consultative phase, the ‘timberization’ phase, the ‘diktat’ phase. The historical phases of formal natural resource management, with special focus on forest management are presented in .

Table 1. Historical phases of forest management policy in Ghana.

This historical perspective of formal natural resource management, especially in forests in Ghana provides a basis for understanding the history of using LSAs for biodiversity conservation in Ghana. This is because using LSAs may help in getting communities’ trust and cooperation in the current collaborative phase, after decades of ‘timberization’ and diktat which alienated communities.

Documentation of LSAs used for natural resource and biodiversity conservation in Ghana is scattered in workshop reports, technical project reports and media reports. This situation could be because LSAs have been implemented by non-governmental organizations, community-based organizations, government agencies and international development agencies. The primary reporting obligations of these agencies have been to the immediate requirements of their donors. Donors work independently of each other and so consolidating the impacts of their interventions is rare. LSA investments are usually managed as micro-credits. Therefore, evaluating success has been focused on outputs such as the number of people benefitting, the number of activities and loan repayment rates. In addition, academic involvement in the implementation of LSAs for biodiversity conservation has been minimal. Research on the use of LSAs in Ghana as alternative livelihoods projects in mining areas (Aryee et al. Citation2003; Hilson & Banchirigah Citation2009; and Temeng & Abew Citation2009) and as part of the government’s poverty alleviation programs (Botchway Citation2001) have largely focused on their role in reducing poverty. Studies on their use for conservation are rare and restricted to their potential for forest conservation (Owusu Citation2001), ecotourism as a conservation tool (Owusu Citation2008), and their use in microcredit schemes for integrated agriculture (Adu-Anning et al. Citation2005). Similar studies (Sargent et al. Citation1994; Richards Citation1995) have focused on the use of incentives in sustainable forest management with particular emphasis on timber production. No study has consolidated information on the use of LSAs for natural resource and biodiversity conservation in Ghana. Such documentation is necessary as an initial step for assessing and evaluating the use of LSAs as a tool for natural resource policy planning in the country. This paper puts in a nutshell the historical trend of the frequency of use of LSAs for natural resource and biodiversity conservation in Ghana, the specific activities, their geographical distribution, and implementation strategy.

Methodology

Data collection and analysis

Information for this study was derived from primary and secondary data sources of biodiversity conservation programs in various parts of Ghana. Primary data, which included information about specific LSAs at the village level, were collected during the months of November 2009 through May 2010 during field visits to 22 towns and villages that participated in LSAs for conservation in Ghana. These towns and villages were located in the coastal savannah, transitional, and the deciduous forest zones of the country. The data were collected during focus group discussions with conservation managers, community leaders, LSA beneficiary groups and their leaders. Secondary data about LSA use in biodiversity and natural resource management projects in Ghana were collected from published project and workshop reports. Other sources include literature and official websites of local, national, and international development agencies working in Ghana as detailed in Appendix.

The historical trend of the number of LSA interventions used in each year was determined by reviewing historical literature such as Kotey et al. (Citation1998), and pre-colonial documents about the Gold Coast (Ghana’s colonial name) dating back to 1953, as well as other project reports which were available on the website of The World Bank. Records of LSAs were reviewed and analyzed to determine the number of projects or programs that employed LSAs (LSA projects) and those that did not employ LSAs (non-LSA projects), as well as the year of implementation of LSAs used for natural resource and biodiversity conservation. Due to the wide range of percentage values (from 0 to 100), a semi-logarithm plot (base 10) of the dependent variable (percentage of LSA versus non-LSA projects) was employed to show the historical trend.

In addition to the primary data collected, the specific LSAs were documented by reviewing environmental conservation literature, especially project reports and published documentation of the history of forestry in Ghana. A key literature source was the reports on 170 small conservation projects implemented under the United Nations Development Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNDP/GEF) Small Grants Program (GEF/SGP Citation2010). The specific activities were categorized on the basis of the type of natural resource product or service and/or agro-economic sector that the LSA targeted. The frequencies of the LSA were the number of the different LSA beneficiary groups and/or activities. For purposes of natural resource and biodiversity conservation planning in protected areas, the specific LSAs which could be located within protected areas, and the ones which could not be located in protected areas were identified.

The geographical distribution of LSAs was determined by enumerating all documented LSA interventions in Ghana and tallying them according to the geographically distinct vegetation zones in which they were implemented. These zones included coastal savanna zone, high forest zone, deciduous forest zone, transitional zone, and northern savanna zone. The reason for using these ecological was because each of these zones has certain distinct biological resources, and this will facilitate future research to evaluate the effects of LSAs on biodiversity.

Results

History of using livelihoods support activities for conservation in Ghana

Out of a total of 162 site-based natural resource and biodiversity conservation projects or programs analyzed, 112 employed LSAs while 50 did not. The earliest conservation project in Ghana that actively involved resource-fringe communities was the Forest Resources Management Project (FRMP), which was funded by the World Bank from 1988. This project started during the late diktat phase (Kotey et al. Citation1998) when there was a crisis in forest management from an increasing demand for agricultural land, technological advances, growing importance of forests as genetic resources, increasing value and concerns for biodiversity, institutional changes as well as the international paradigm shifts in forest management (Owusu Citation2001). The FRMP involved capacity building of government agencies in forest management, and did not employ LSAs. For projects that employed LSAs, the earliest record of LSA used for biodiversity conservation was in 1993 (GEF/SGP Citation2010). This was a small project in northern Ghana, which supported women farmers to grow economic fruit trees and woodlots in order to reduce the impact of fuel wood harvesting which was threatening biodiversity.

The historical trend analysis using the best-fit linear logarithmic (base 10) curves indicate that since 1993, there has been a significantly increasing (R2 = 0.5087) tendency for LSA use for natural resource and biodiversity conservation purposes in Ghana (). This graph also indicates a more sharp corresponding decrease in percentage of non-LSA projects.

The specific livelihoods support activities used for conservation in Ghana

A total of 71 specific LSA types belonging to eight categories and 21 sub-categories were identified (). The categories included perennial crops, annual crops, livestock (including poultry), water resources, agro-processing, non-timber forest products (NTFPs), services, and rural non-food products. Woodlots for timber and fuelwood, as well as beekeeping, non-timber forest products and nature tourism were all determined to be LSAs that could be effectively located within a protected area.

Table 2. Livelihoods support activities (LSAs) used for conservation in Ghana.

About the possibility of locating LSAs in protected areas, 137 individual LSA activities could be located within protected areas while 219 could not be located within protected areas. A z-proportions test indicated that these two frequencies were significantly different (N = 356, p < 0.0001, z = 12.0416). This suggests that fewer LSAs could be located within protected areas, which are the main locations for biodiversity conservation in Ghana.

The highest number (102) of LSA cooperatives and/or activities were for non-timber forest products (NTFPs), followed by livestock-keeping (70) and annual crop cultivation (42). Activities involving water resources had the lowest frequency (). The highest frequency of LSAs involving NTFPs could be accounted for if we assume that the natural resource conservation strategy was aimed at increasing the supply of non-timber forest resources for community members.

The geographical distribution of livelihoods support activities in Ghana

Out of a total of 112 biodiversity conservation projects that had LSA components, the highest proportion (33%) was recorded in the northern savanna area and the lowest of 9% was recorded in the coastal area (). Most of the projects in the northern savanna were small projects under UNDP/GEF Small Grants Programme in Ghana.

Discussion

Historical trend, types, and location of livelihoods support activities

The fact that the GEF/SGP was the first natural resource and biodiversity conservation project to include LSAs was confirmed by further literature review. The World Bank (Citation2000) indicated that in 1997, the GEF/SGP was the only source of an Implementation Manual for the Community Investment Fund component (LSA components) of a conservation project in the country. The highest rate of increase in LSA use for natural resource and biodiversity conservation was recorded from 1993 to 2000. Ghana’s current collaborative forest policy was completed, adopted, and promoted during these years. This trend of LSA use over the period helped to explain how important LSAs have become for conservation managers in Ghana. More specifically and importantly, the very sharp decrease in the non-LSA projects after 2000 suggest that conservation projects and managers have not been able to do without including LSAs as part of project due to the significant social and political support for LSAs. This particular issue was identified in two projects, which modified their implementation strategies to increase involvement of communities by increasing the projects’ focus on income-generating activities (IGAs) in resource-fringe communities. These projects were the Northern Savanna Biodiversity Conservation Project (NSBCP) funded by The World Bank and other bilateral developmental partners of Ghana in 2005 and the Participatory Forest Resource Management Project in the Transitional Zone of the Republic of Ghana (PAFORM) funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in 2006.

Specific LSAs supported in an area may be influenced by the location, culture, and the resources in the area. For example, beekeeping was more common in forest areas than in savanna areas. Similarly, animal husbandry was most common in the northern savanna where it is a very common practice to keep goats and sheep as part of household income source. The highest frequency of LSA involving NTFPs could be explained by the strategy to increase supply of non-timber forest resources for community members that participate in LSA programs. This is also due to the fact the forest contribute to all aspects of rural life by providing food, fodder, fuel, medicine, building materials, cultural symbols, and ritual artefacts (Falconer Citation1996). Also the high number of livestock activities and groups could be explained by the high number of LSA projects in the northern savanna area where animal husbandry for sheep and goats is a very common income generating activity. The level of investments in annual crops as conservation LSAs could be explained by the agrarian economy in most rural areas in Ghana. Amanor (Citation1994) points out the favorable conditions exist in farming communities for environmental actions and development approaches based on sustainable development, since these areas have suffered from the negative effects of degradation. The low number of water resources groups could also be explained by the small number of LSAs in the coastal areas and the relatively smaller attention given to water resources conservation as compared to forest vegetation and terrestrial wildlife conservation in Ghana. Most LSA activity sites were not located within protected areas even though that may not be detrimental to biodiversity. This could be because the classical conservation paradigm of excluding anthropogenic factors still lingers in biodiversity conservation and management. With the current forest conservation practices, this may be applicable only within community forests.

The high number of LSA projects in the northern savanna could be explained by the relatively large size of the area, high poverty levels and the high environmental stress in the area. The high poverty levels contribute to high dependence on and exploitation of natural resources, hence the need for economic incentives for biodiversity conservation. The high environmental stress is due to the lowest mean annual rainfall and only one annual rainy season in the area. In addition, there are few government managed conservation areas in this zone, hence the intervention of the GEF/SGP program to support NGO activities that enhance conservation. The lowest record of LSAs in the coastal zone could be explained by the relatively small area covered by the coast. In addition, due to the high density of human settlements in coastal areas (Small & Nicholls Citation2003), there are relatively smaller areas available for biodiversity conservation. This result could also be accounted for by the fact that coastal and marine biodiversity conservation in Ghana has not been attractive to policy makers because the understanding of coastal resources is focused on fish production from the sea and coastal lagoons, thus leading to inadequate protection of high biodiversity areas such as wetlands. The low number of LSAs in the high forest zone could also be explained by the high number of government-managed conservation areas in this zone. The GEF/SGP projects, which formed about 83% of the LSA projects, were located in areas that have few conservation areas managed by government agencies. Also, due to favorable climatic conditions, the stress on natural resources in the forest areas is relatively lower.

Potentials of using livelihoods support activities as incentives for conservation

McNeely (Citation1988) outlines five objectives that can be addressed by incentives to conserve biological resources at the village level. These objectives include capacity building in activities that do not deplete biological resources, reduce pressure on marginal lands for agriculture, concentrate agricultural production on the most productive lands, and conserve traditional knowledge, compensation of community members for income lost through access limitations, and restrictions on the use of protected biological resources. Assessing the potential of how LSA use in Ghana achieves these objectives can be used to determine their potential for conservation. The capacity building objective was largely achieved because of training programs in basic business management and novel agricultural practices in most LSA programs. The training programs also provided the opportunity to increase conservation education, improve financial management, and group dynamics among community members. There were very few programs intended to reduce agricultural pressure on marginal lands, even though that could serve conservation purposes better. LSA programs could work to increase crop production through the improvement of soil fertility through agroforestry or by introducing better yielding crops or animals. The objective of concentrating agricultural production on the most productive lands was difficult to influence because farmers do not have the ability to determine where to cultivate their crops. In Ghana, where an individual cultivates is determined by the family or clan he or she belongs to, or the ability to buy or lease land. Conserving traditional knowledge by LSAs would involve investing in, maintaining and propagating natural resources which had been used to sustain the local food systems, health and traditions of an area. In order to achieve this, it may be necessary to promote the propagation and improved packaging of herbal medicine because of the decreasing forests and inadequate documentation of the medicinal values of plants in Ghana. Such activities empower local communities, help to sustain cultural practices which have maintained these communities for centuries, and provide local employment. Intellectual rights need to be protected, though.

This study has shown how important LSAs have become in natural resource and biodiversity conservation in Ghana. A demand and supply classification of economic instruments used for natural resource and biodiversity conservation (Ekpe Citation2012) indicates that LSAs are supply instruments. This is because they directly affect the supply of resources. In some cases, LSAs have been used to replenish plant resources through enrichment planting of timber and other useful trees in forests, as well as planting of mangroves in wetlands. The LSAs were however not used to directly increase populations of wild animals, though there is the potential to increase snail populations by reintroducing eggs and young ones into protected areas. One major outcome of the inclusion of LSAs in small conservation projects in Ghana was their contribution to community natural resource conservation. This was evident in that the UNDP/GEF SGP projects resulted in about 2500 square kilometers (250,000 hectares) of land outside protected areas being placed under effective community management (Global Environment Facility Citation2008). Ghana’s current Forest and Wildlife Policy (Ministry of Lands and Forestry of Ghana Citation1994) uses a collaborative conservation strategy. Effective implementation of this policy requires support from communities located near protected areas or other high biodiversity value areas. This necessary social support, poverty, and increasing demand for natural resources make the need for economic incentives such as LSAs very important for biodiversity conservation, in Ghana. These collaborations for resource management can be effective by working with Collaborative Resource Management Areas (CREMAs), which are geographically defined areas that include one or more communities, and that have agreed to manage natural resources in a sustainable manner. CREMAs are the primary institutional mechanism being utilized by the government of Ghana for implementing collaborative resource management outside protected areas (Agidee Citation2011), and so can be a sustainable vehicle for long-term conservation interventions. Such long-term interventions will enable affordable and efficient pre-intervention studies, program monitoring, and post-intervention studies to determine the effects of interventions such as LSAs.

In conclusion, the use of LSAs as part of conservation programs has not been without challenges. Very few LSAs were directly aimed at increasing natural resources and biodiversity within the resource base or protected areas – in situ development of biological resources. Another key challenge was the delay in releasing funds for some activities, which resulted in some materials becoming available during the wrong seasons. However, inclusion of LSAs in small conservation projects in Ghana especially by the UNDP/GEF SGP projects, contributed to conservation of lands outside protected areas. The country’s current collaborative conservation policy and the consequent need to provide economic incentives for communities to support conservation efforts make LSAs very important. In order to understand the roles that LSAs play in the lives of poor communities located on the fringes of protected areas, it is necessary to evaluate their socioeconomic values from the perspective of the beneficiaries and the villages and towns they live in. This will include determining the resource use factors such as competition for access to and use of resources, options or alternatives and opportunity costs, that determine what LSAs are employed in an area. It is also important to understand how LSAs affect biodiversity conservation in Ghana. This requires research on how LSAs affect attitudes and behaviors toward the environment, and the effect of these on biodiversity. This kind of research is necessary to inform future conservation projects how to strategize LSAs in projects in order to achieve biodiversity conservation outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the UNDP/GEF Small Grants Programme in Ghana, Forest Services Division of the Forestry Commission of Ghana, Ghana Wildlife Society, and Okyeman Environment Foundation for providing project resources for this study. We thank communities in the Afadjato-Agumatsa and Atewa areas for access to LSA participants. Thanks to E. Cudjoe for field assistance and L. Becker for GIS assistance. E.K.E was supported by the International Tropical Timber Organization, International Foundation for Science, and the West African Research Association.

References

- Adu-Anning C, Atuah L, Duku S, Edusah SE, Fialor SC, Sey S. 2005. Micro-credit as an instrument to promote indigenous food resources in Ghana. International Centre for Development-oriented Research in Agriculture (ICRA) Working Document Series 123.

- Agidee Y. 2011. Forest Carbon in Ghana: spotlight on Community Resource Management Areas. Katoomba Group’s Legal Initiative Country Study Series. Washington, DC: Forest Trends.

- Amanor KS. 1994. Ecological knowledge and the regional economy: environmental management in the Asesewa District of Ghana. Dev Change. 25:41–67.

- Aryee BNA, Ntibrey BK, Atorkui E. 2003. Trends in the small-scale mining of precious minerals in Ghana: a perspective on its environmental impact. J Clean Prod. 11:131–140.

- Ayoo C. 2008. Economic instruments and the conservation of biodiversity. Manage Environ Qual: Int J. 19:550–564.

- Botchway K. 2001. Paradox of empowerment: reflections on a case study from northern Ghana. World Dev. 29:135–153.

- Ekpe EK. 2012. A review of economic instruments employed for biodiversity conservation. Consilience: J Sustain Dev. 9:16–32.

- Falconer J. 1996. Developing research frames for non-timber forest products: experiences from Ghana. Chapter 8 In: Perez MN, editor. Current issues in non-timber forest product research: proceedings of the Workshop “Research on NTFP”, Hot Springs, Zimbabwe, 28 August - 2 September 1995. Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research.

- Global Environment Facility (GEF). 2008. Joint evaluation of the GEF Small Grants Programme. Washington, DC: GEF Evaluation Office; p. 89.

- Global Environment Facility/Small Grants Programme (GEF/SGP). 2010. Project reports of the Global Environment Facility/Small Grants Programme of the United Nations Development Programme, Ghana Projects; [cited 2010 Sep 15]. Available from: http://sgp.undp.org/index.cfm?module=SGP&page=ContactCountry&CountryID=GHA.

- Hilson G, Banchirigah SM. 2009. Are alternative livelihood projects alleviating poverty in mining communities? Experiences from Ghana. J Dev Stud. 45:172–196.

- Kotey ENA, Francois J, Owusu JGK, Yeboah R, Amanor KS, Antwi L. 1998. Falling into place. Policy that works for forests and people series number 4. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- McNeely JA. 1988. Economics and Biological Diversity: developing and Using Economic Incentives to Conserve Biological Resources. Gland: IUCN.

- Ministry of Environment and Science of Ghana. 2002. National biodiversity strategy for Ghana [Internet]. [cited 2012 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.cbd.int/doc/world/gh/gh-nbsap-01-en.pdf

- Ministry of Lands and Forestry of Ghana. 1994. Forest and Wildlife Policy [Internet]. [cited 2011 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.fcghana.com/publications/laws/foresty_wildlife_policy/index.html

- Ntiamoa-Baidu Y, Owusu EH, Daramani DT, Nuoh AA. 2001. Ghana. In: Fishpool LDC, Evans MI, editors. Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands: priority sites for conservation. Newbury: Pisces Publications and BirdLife International – BirdLife Conservation Series No. 11; p. 367–389.

- Owusu EH. 2001. The Potential of Afadjato-Agumatsa Conservation for Ecotourism Development [ Unpublished PhD Thesis]. Canterbury: DICE, University of Kent.

- Owusu EH. 2008. Ecotourism as a conservation tool – a case of Afadjato–Agumatsa Conservation Area, Ghana. J Sci Technol. 28:166–177.

- Richards M. 1995. Role of demand side incentives in fine grained protection: a case study of Ghana’s tropical high forest. For Ecol Manage. 78:225–241.

- Sargent C, Husain T, Kotey NA, Mayers J, Prah E, Richards M, Treue T. 1994. Incentives for the sustainable management of the Tropical High Forest in Ghana. Commonw For Rev. 73:155–163.

- Small C, Nicholls RJ. 2003. A global analysis of human settlement in coastal zones. J Coastal Res. 19:584–599.

- Temeng VA, Abew JK. 2009. A review of alternative livelihoods projects in some mining communities in Ghana. Eur J Sci Res. 35:217–228.

- The World Bank. 2000. The Implementation Completion and Results Report of the Coastal Wetlands Management Project (CWMP). The World Bank.

- Tropenbos International. 2005. Alternative livelihoods and sustainable resource management. Inkoom DKB, Okae Kissiedu K, Owusu Jnr B, editors. Tropenbos International Ghana Workshop Proceedings 4. Proceedings of a workshop held in Akyawkrom; Apr 1; Ghana. Wageningen: Tropenbos International.

- Tutu KA, Ntiamoah-Baidu Y, Asuming-Brempong S. 1993. The economics of living with wildlife in Ghana. Report prepared for The World Bank, Environment Division; 85pp.

- United Nations Environmental Programme. 2004. Economic instruments in biodiversity-related multi-lateral environmental agreements. New York: United Nations Publications.

Appendix Sources of data on the use of livelihoods support activities in Ghana