Abstract

Cultural ecosystem services (ES) are particularly challenging to value as well as to subsequently incorporate in scientific assessments and environmental management actions and programmes. In this paper, we apply a cultural ES typology to an Australian water resources case at a location of major indigenous cultural significance, the Brewarrina Aboriginal fish traps, and consider the potential implications for water planning. Data from qualitative interviews with indigenous custodians demonstrates diverse cultural values and associated benefits with respect to the fish traps themselves and to their connectivity with another key water site, an upstream lagoon. Supported by additional analyses of water planning legislation, flow requirements, and non-indigenous tourist values, we analyse the applicability of the typology and the implications for water planning. Key issues include: the distinction between values and benefits; whose values and which cultural ES benefits are identified and managed; the challenges of categorising indigenous aspirations within cultural ES frameworks; and the implications for water planning of indigenous perspectives on connectivity. Case studies of culturally specific minorities are useful for testing cultural ES frameworks because they posit conceptual and categorisation challenges. In addition, ‘culture’ is often of strategic and symbolic value for such minorities, representing the key means by which they gain access to, and traction within, natural resource planning and prioritisation processes.

Introduction

Allocating freshwater resources among different users who hold diverse and sometimes competing values relating to water is a key planning and management challenge in river basins worldwide. Within environmental management domains, there is now greater recognition that social action, including human interaction with the environment, is informed by an array of values (O’Brien & Guerrier Citation1995). Throughout the world, an added dimension to this challenge is acknowledging and integrating indigenous values into natural resource management (NRM) (Bark et al. Citation2012). As interest in the human dimensions of environmental management and biodiversity conservation has increased, defining and integrating social and cultural values into planning frameworks have become a key focus. This trend is particularly evident in relation to water resources, which have widespread social and cultural significance (Johnston et al. Citation2011, Citation2012). A more pluralistic consideration of resource management is increasingly embracing differences in knowledge, resource use and values between and within social groups (Norton Citation2000), and resource managers are expected to take into account differences in human perspectives attributed to cultural background and religious beliefs (Jackson Citation2006).

Different disciplines attribute diverse meanings to the word ‘value’. For example, although many people use the term synonymously with price, economists are more likely to use the word when considering the extent to which a particular good or service contributes to the well-being of an individual or of society, whereas social scientists are more likely to use the phrase ‘value system’ when talking about either an individual’s or a society’s set of principles, norms and beliefs. Transmitted by cultural and social processes, values are often shared within groups of people, and conformity with or resistance to group values can be an important way of expressing identity. This paper builds on the growing number of studies that apply value concepts in water management (Keeler et al. Citation2012). It draws on a large and diverse literature on ‘values’ and this includes: their definition (Heberlein Citation1981); categorisation – for example held versus assigned (Brown Citation1984; Brown & Manfredo Citation1987; Adamowicz et al. Citation1998), intrinsic versus instrumental (Reser & Bentrupperbäumer Citation2005), use versus non-use (Pearce Citation1993; Bateman et al. Citation2003), and cultural and social values (Graeber Citation2001; McIntyre-Tamwoy Citation2004; Jackson Citation2006); elicitation (Hatton MacDonald et al. Citation2013); and their use in conservation (Norton Citation2000; Jepson & Canney Citation2003).

In terms of approaches to valuation, the ecosystem service (ES) framework is increasingly ascendant in ecological economics and in wider environmental and NRM discourse (MEA Citation2005; Fisher et al. Citation2008; TEEB Citation2010; Bateman et al. Citation2013; Tallis et al. Citation2013). In adopting the framework, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment noted that humans receive a variety of different ES – categorised as provisioning, regulating, cultural and supportive services – which contribute to a variety of constituents of human and social well-being, such as security, health, social relations, food, and freedom of choice and action (MEA Citation2005). Within the ES framework, cultural ES have been identified as particularly challenging to value and to incorporate into decision making (Chan et al. Citation2012; Satz et al. Citation2013), particularly as the term ‘culture’ can have a diverse range of meanings (Kroeber & Kluckhohn Citation1952). Categorisations of ‘cultural’ ES refer to, for example, aesthetics, spiritual inspiration, individual and collective identity, and the recreation benefits that people obtain through direct and indirect interactions with ecosystems (de Groot et al. Citation2002; MEA Citation2005; TEEB Citation2010). More recent classifications of cultural ES identify underlying principles, virtues, preferences and value dichotomies (Chan et al. Citation2012; Ruiz-Frau et al. Citation2013). Chan et al. (Citation2012) explain that contemporary definitions of cultural ES in environmental decision making have tended to conflate services/benefits and values. In practice, case studies of ethnic and indigenous minorities may be particularly powerful for interrogating the overall importance, as well as the potential intensity and diversity, of cultural values and benefits within an ES framework.

Operationalising the ES approach raises issues of how cultural ES enter into the decision-making process. In what instances can cultural ES be valued monetarily and is this a worthy objective? It can be argued that valuing cultural ES through monetary approaches can result in more equitable treatment, particularly when considered alongside other market-based values, such as provisioning ES, e.g. irrigated agricultural production. Yet, monetarily valuing cultural ES depends on how well they map to the total economic value (TEV) framework utilised in environmental economics (Pearce Citation1993; Bateman et al. Citation2003) and the availability of funds to undertake original research or best practice benefit transfer (NOAA Citation1996). In instances where standard environmental economics valuation methodologies are not appropriate, there is the possibility of relying on other methodologies such as ranking (Satz et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, managing for cultural ES benefits may not fully address underpinning cultural values. Whether or not all water-related cultural values can be identified and addressed in water-resources planning depends on how flexible and capable planners and planning frameworks are in taking account of the human-environment relations, interactions and practices that generate and sustain specific cultural values rather than just those that result in measurable benefits.

In Australia, water planning is the ‘process for transparently determining the distribution of water resources over time. It is the central mechanism used by governments and communities in making water management and allocation decisions to meet specific productive, environmental and social objectives’ (NWC Citation2011, p. 2). Australia has a long history of water planning and our focus is on Australia’s largest river basin, the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB, ). Recent basin-scale water reform (Water Act 2007) required the development of a Basin Plan, which resulted in research into water values, water planning and management (Jackson et al. Citation2010; Hampstead Citation2011; Commonwealth of Australia Citation2011, Citation2012). There is a statutory requirement in the Water Act 2007 to have ‘regard’ to indigenous issues (Water Act 2007, ss. 21(4)(v)). Basin Plan (Citation2012; Commonwealth of Australia Citation2012), has reset the balance between human-consumptive and environmental water uses in the MDB; however, it does not explicitly address the issue of water flows to recover, support and enhance indigenous values in the basin.

For a range of reasons, progress towards meeting indigenous claims and expectations with respect to water has been slow throughout Australia (NWC Citation2011; Bark et al. Citation2012; Tan & Jackson Citation2013). As a consequence, the cultural and economic expectations of indigenous Australians remain an ‘unmet demand on the water system’, according to the most recent review of Australian water reform (NWC Citation2011, p. 9). The intangible values that indigenous people regard as critical to their sense of identity, cultural and customary management practices, spiritual beliefs, and livelihoods, are difficult to quantify and, for this and other reasons, can be overlooked when other water users are competing for clearly defined amounts of water (Maclean et al. Citation2014). In the highly over-allocated systems of the MDB, allocating water for indigenous uses has been contentious (Weir Citation2009; Jackson Citation2011). Robust valuation techniques are needed to assist in the determination of indigenous water requirements, consistent with the Basin Plan (Citation2012), and in articulating the consequences of any trade-offs. Effectively identifying and valuing indigenous water requirements is of national significance given the imperatives established by current Australian water policy to improve indigenous access to water and protect indigenous water cultures and traditions, but is also of international interest as it provides practical lessons in valuation techniques and issues.

In this paper we explore cultural ES frameworks, notably the typology developed by Chan et al. (Citation2012) and how it can be operationalised in water planning. We use a case study of indigenous interests in water sharing in rural New South Wales (NSW). Our analysis aims to improve the effectiveness of the ES framework in decision-making by: (i) distinguishing values from benefits; and (ii) seeking ways to appropriately treat diverse kinds of values (Chan et al. Citation2012). Data from qualitative interviews with traditional custodians demonstrates a diverse set of cultural values and associated benefits that warrant attention from water planners who are currently required to meet the statutory goal of incorporating indigenous values in water allocation planning. In utilising this framework (Chan et al. Citation2012), we draw on additional analyses of water planning legislation, flow requirements and non-indigenous tourist values to identify what types of information may be useful in assessing performance against objectives and targets relating to indigenous cultural values as well as inter-related ecological and economic values.

Study site and methods

The case study is located in NSW where a Water Sharing Plan (WSP) is a statutory instrument. The regional town of Brewarrina, NSW, is located on the Barwon–Darling River, which is an unregulated river in the upper MDB that flows through the Condamine catchment in a south-westerly direction from the Queensland-NSW border (see ). The Condamine catchment is representative of a large Australian dryland river system, and key characteristics include its low gradient and large floodplain, climatic variability and arid to semi-arid conditions. Australia’s Sustainable Rivers Audit (MDBA Citation2012) rates the overall ecological health of the catchment as ‘poor’.

The Brewarrina Aboriginal fish traps are a complex arrangement of stone pens, channels and rock walls covering 400 m of the Barwon River bed (see ). The site is referred to as ‘Baiame’s Ngunnhu’ by indigenous people because it was named after an ancestral creation being who created the traps for local people during a time of major drought. The traps were used and continue to be used today to catch fish in receding floodwaters. As the largest known feature of their kind in Australia, the fish traps are regarded as an outstanding example of pre-European contact aquaculture. The age is unknown but they may be one of the oldest continuing human constructions in the world.Footnote1 The site demonstrates ‘advanced knowledge of engineering, physics, water ecology and animal migration to catch large numbers of fish in traps and is also steeped in legend’ (Jones Citation2011, p. 134). The fish traps are also an important historical inter-tribal meeting place for indigenous groups from the surrounding area in particular the Ngemba people who are the custodians of the site, as well as the Murrawarri, Euahlayi, Weilwan, Ualari and Barranbinya people (BSC Citation2011; see Figure from Mathews Citation1907). According to zoologist Theodore Roughley, writing in the 1950s,

[s]everal tribes had the right of fishing in this dam, though each tribe was strictly forbidden to take fish from any portion not allotted to it. The principal fish caught were Murray cod, callop, silver perch and freshwater catfish. They were recovered from the traps either by hand, net or spear, and during times of flood they were dived for (Roughley Citation1951 cited in Roberts 2010, p. 22).

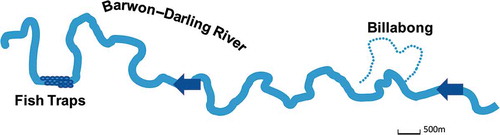

In recognition of their significance, the fish traps were included on Australia’s National Heritage List in 2005 (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2005). Upstream of the fish traps is the Ngemba billabongFootnote2 an Indigenous Protected Area (IPAFootnote3) managed by the Ngemba people. The IPA was declared in November 2010. The two sites are treated in cultural terms as one complex site (see for a schematic representation of the Ngemba stretch of the Barwon–Darling River). The billabong connects to the river during floods; it fills and provides habitat for fish and yabbies (freshwater crayfish) and recreational and cultural opportunities for the Ngemba community. The fish traps were constructed to catch fish in the receding floodwaters, i.e. they are exposed during low flows when it is no longer possible to catch fish in the billabong. In the past, Ngemba fishing (and cultural) activity shifted location with river flow conditions (Maclean et al. Citation2012).

Figure 3. Conceptualisation of the Ngemba stretch of the Barwon–Darling River (Source: Authors’ conceptualisation).

Our case study was developed with the Ngemba people, and it was chosen as the result of: (1) research ties established during an earlier scoping study on MDB water sharing reform and Indigenous communities (Jackson et al. Citation2010); (2) the presence of the Brewarrina Aboriginal fish traps as a significant cultural asset which adds another dimension to water planning; and (3) the existence of State WSP that explicitly seek to allocate water to and manage for indigenous cultural values (see Tan & Jackson Citation2013 for detail on four types of special purpose licenses introduced for indigenous interests. No other State in the MDB has such provisions).

The study incorporates data derived from a mixed methodological approach. The primary data underpinning this paper is derived from single and group qualitative interviews and associated value elicitation with traditional custodians. This approach enabled participants to speak about past and contemporary values, as well as to highlight future aspirations for water sharing and ongoing management of the river, and the two sites (Maclean et al. Citation2012).Footnote4 This field interview data was augmented by three additional research processes: an analysis of relevant literature and water planning policy and legislation (Jackson & Langton Citation2012; Tan & Jackson Citation2013); an examination of specific flow requirements associated with the billabong (Maclean et al. Citation2012); and an exploration of the monetary value (through tourism) of indigenous cultural heritage (Maclean et al. Citation2012).

The data was re-analysed by the project team and reconfigured using the framework for cultural ES benefits developed by Chan et al. (Citation2012). Potential metrics to chart progress towards incorporating these benefits in water planning or other NRM processes were also identified. This step was undertaken as the WSP explicitly incorporates a requirement to assess ‘the extent of recognition of spiritual, social and customary values of water to Aboriginal people’ (NSW Citation2012, Part 2, Clause 12 (i)). One of nine performance indicators used to measure success towards meeting the objectives of the WSP, is: ‘the extent of recognition of spiritual, social and customary values of water to Aboriginal people’ (NSW Citation2012, Part 2, Clause 12 (i)). Two other performance indicators, measuring change in the ecological value of key water sources and their dependent ecosystems and change in economic benefits derived from water extraction and use (Clause 12(e) and (h)), are also related in important ways to the benefits indigenous people derive from the site.

Results

In we classify indigenous cultural ES benefits according to the categories of benefit developed by Chan et al. (Citation2012). For each benefit we also note if there is data available (denoted with a ‘√’), if it is reflected in legislation, the WSP for the river reach (NSW Citation2012), or in National Heritage Listing (denoted with a ‘√’ and acronym for the legislation etc.) and illustrate Ngemba perspectives using quotes from Maclean et al. (Citation2012) (page number(s) in brackets). Chan et al. (Citation2012) also identify a range of additional specifications (kinds of value) that can be used to further elucidate each category of benefit. This additional specification is represented as a series of value dichotomies (self-oriented vs. other-oriented, individual vs. group, physical vs. metaphysical, etc.). These were found to be challenging to apply to the field data (see comments on this topic in the ‘Discussion’ section), and so are not represented here. In addition, a crucial component of the field data elucidated by indigenous research participants related to aspirations for the future and it was unclear how exactly to deal with such a research finding within the framework adopted – does an ‘aspiration’ constitute a ‘benefit’ and if not, how should such matters of primary importance to field participants be communicated within a cultural ES approach? We chose to treat culturally-oriented aspirations as a component of cultural ES benefits and therefore to classify them according to the subcategories of the framework. However in order to distinguish aspirations as a distinct and critically important subset, they are demarcated in the table in italics.

Table 1. Cultural ES benefits, potential metrics, availability of data and inclusion in legislation, planning or management arrangements, and Ngemba perspectives.

presents the reanalysis of four data sources: the interview responses from indigenous participants, the preliminary travel cost study, the eco-hydrological modelling, and review of policy and planning documents. It shows that there currently is a range of data and avenues for protecting the sites and for allowing indigenous contributions to management, though this is not comprehensive. Examining the comments from the indigenous research participants demonstrate that classification of them into the values (and aspirations) identified in the framework was not always straightforward. In a number of cases, multiple categories were potentially possible. Nevertheless, with the inclusion of the aspirations, a clear theme that emerged with relevance to water planning is connectivity. In the field interviews, Ngemba participants expressed strong interest in managing the billabong and river holistically, increasing the quantity of water flowing in the river and thus into the billabong (as they explained that the billabong should be connected to the river at times of high flow). We discuss this theme and the incorporation of cultural values, as distinct from cultural benefits, in water sharing plans next.

Discussion

Analyses of social relations and practice in fields such as social impact assessment, archaeology and heritage management have historically been limited by both the conceptual separation of natural and cultural spheres and by problems in defining culture (King Citation1998; English Citation2002). Byrne et al. (Citation2003) and McIntyre-Tamwoy (Citation2004) argue that, like the North American experience, Australian cultural heritage practice has focused on sites and buildings with values treated ‘as synonymous with objects or elements’ (McIntyre-Tamwoy Citation2004, p. 291). Within frameworks that emphasise a material view of heritage, the distinguishing features of an indigenous cultural landscape for example tend to be reduced to site identification and management according to archaeological techniques and values (Avery Citation1993; English Citation2002; Jackson Citation2006). English (Citation2002) describes what is lost when an ‘archaeological’ approach is taken:

By providing data about tangible objects, it avoids the complex values associated with people’s connections to place and their interaction with the landscape around them. These values are often intangible and not easily encompassed by the myth that planning is an objective exercise and hence value free. (p. 219)

We find evidence for Jackson’s (Citation2006) contention that an outcome of this cultural heritage paradigm is that water resource managers will look to heritage management practice for guidance in matters considered ‘cultural’. Yet, as noted in the ‘Introduction’, ES frameworks and valuation techniques are of growing significance in NRM decision making, and therefore definitions of ‘culture’ that emerge from such frameworks may become increasingly influential. In either case, the importance of appropriately comprehensive and inclusive definitions of cultural values should be emphasised.

In examining cultural ES, Chan et al. (Citation2012) note the importance of the demarcation of values and benefits, as the conflation of the two is a noted pitfall in ES studies. In the WSP under study here, value is the primary terminology used: ‘the extent of recognition of spiritual, social and customary values of water to Aboriginal people’ (NSW Citation2012, Part 2, Clause 12 (i)). Based on the analysis undertaken here and reflecting cultural heritage influences, there is evidence of this conflation in the Brewarrina case – the current management approach emphasises the archaeology of the fish trap site and the immediate ‘benefits’ associated with that site, rather than adopting a landscape-scale perspective that would manage the Ngemba stretch of the Barwon–Darling River as a whole and more accurately reflect the holism underlying indigenous values. In addition, managing for these wider values would also enhance benefits – a landscape approach would improve the health of the billabong and its capacity to produce fish and invertebrates that are then captured in the fish traps.

Moving from the general value/benefit distinction to the application of the framework itself, the process of classification illuminated synergies and gaps between theoretical concepts and field data from a context in which ‘culture’ is a critical consideration. Firstly, the fieldwork highlighted a component of values that we delineated as future aspirations. These aspirations reinforce other prominent themes articulated by Ngemba participants, like connectivity and holism and cultural responsibility to sustain cultural assets in an ecological/landscape context. The inclusion of an aspiration category revealed how thoughtfully the community has considered the role of ecological and hydrological processes in sustaining their life, livelihoods and culture.

As Indigenous values and benefits encompass both individual sites and local connectivity between sites this presents an issue of scale for water planning. In this case study, a key relevant scale for indigenous custodians is a particular river reach, rather than a single water-dependent site (likely to be the focus of cultural heritage legislation) and/or the entire catchment/river (likely to be the focus of water planning). This suggests that multiple geographic scales and connectivities need to be incorporated into water planning processes to effectively address indigenous perspectives and priorities.

Taking the issue of connectivity more broadly, it can be understood in a range of ways in terms of cultural ES – hydrological and ecological connectivity between the Ngemba billabong and the fish traps, between people and the river, between cultural practices and hydrological knowledge of water flows and waterway ecologies, and between Dreamtime (Creation) stories and their encoded rules and current management practices. These aspects of cultural value expand the importance of the fish trap site from one that is significant for its archaeological value to one with multiple social, cultural, ecological and economic values, as well as recognition of the key stewardship role of traditional owners and custodians. System holism is central to indigenous water cultures from the Darling River region (Muir et al. Citation2010) and elsewhere (Barber Citation2005; Bradley Citation2010), yet it is difficult to place within current typologies that demarcate categories of value (economic, cultural, ecological) and/or posit oppositions such as those made by Chan et al. (Citation2012): self-oriented vs. other-oriented, individual vs. group, physical vs. metaphysical, etc. Future research could field test these value dichotomies and address the value of system holism (see Johnston et al. Citation2011 for an example) or what has become known in heritage circles as a cultural landscape approach (Byrne et al. Citation2003).

In water planning terms, there are potentially diverse implications arising from an increased focus on connectivity: greater general alignment with indigenous concepts of landscape holism; potential enablement of specific indigenous resource ownership and management aspirations; and potential for increased non-indigenous values if the fish trap site is conceptually and functionally situated as part of a dynamic region containing numerous features of significance. The inclusion of the site in existing heritage registers flags this possibility – that it is already valued by non-indigenous people, even those who will never visit it (as are other indigenous sites, see Rolfe & Windle Citation2006; Zander et al. Citation2010). Furthermore, the travel cost results (Maclean et al. Citation2012) provide a preliminary monetary valuation for those who do visit, suggesting that, at the level of local benefit, there is the potential for increased regional economic benefits through appropriate management. Such attention to system holism in water planning is particularly attractive when it can demonstrate no-regrets pathways in water allocations – when, for example, clear benefits accrue for cultural tourism, indigenous values, and ecological connectivity with minimal impact on other water users (e.g. , Options, Ngemba perspectives).

A further implication relates to the inter-relationships between the cultural and other values that are the subject of management focus, including monitoring activity. The WSP has multiple objectives and performance indicators that include: to recognise indigenous values, measure change in the ecological value of key water sources and consequent economic benefits or costs arising from water extraction. Indigenous people also have multiple objectives and, as this case shows, their cultural values have evolved over centuries of interacting with a particular river reach and an associated flow regime that replenished the billabong and provided food resources and fishing opportunities. The river’s historical flow regime has been altered in recent decades to the detriment of water bodies of major ecological and cultural significance. Maclean et al. (Citation2012) hypothesised that by returning the observed flow regime and flood metrics to a ‘natural’ or ‘pre-development’ pattern, the function of the billabong as a habitat for native fish – a key management objective of the Ngemba – would also be satisfied. The case study highlights the need for water planners to draw out the eco-hydrological connectivities and links to human values and benefits in their assessments prior to making water allocation decisions and in subsequent monitoring and plan evaluation (Finn & Jackson Citation2011).

From a policy and legislative perspective, existing water planning frameworks face considerable challenges in acknowledging indigenous water needs and in allocating water for a suite of indigenous values, including economic, subsistence, cultural, etc. (Finn & Jackson Citation2011; Bark et al. Citation2012; Jackson & Barber Citation2013). In some instances, identifiably indigenous cultural values (and associated cultural ES) may be highly distinct from those experienced by other Australians interacting with the same ecosystems (Strang Citation1997). There is scope to move away from monetary valuation – only ES assessments through use of deliberative approaches such as ranking (Satz et al. Citation2013), as well as approaches like ours that appropriately treat diverse kinds of values and seek to incorporate them and related community aspirations into decision making. In the Barwon–Darling water resource planning area there are a number of indigenous-specific entitlements available to indigenous communities to protect water-dependent values and benefit from water access, including entitlements that can provide water for cultural purposes, environmental purposes and for the protection of native title (Tan & Jackson Citation2013). At the time of writing, Ngemba people have not yet obtained any water under these indigenous-specific entitlements.

In mounting a successful case for water allocations in a Basin where competition for water is high, environmental degradation manifest and indigenous access negligible (Tan & Jackson Citation2013), indigenous communities will need a clear understanding of their water requirements and a persuasive account of the potential benefits of having them met. The mapping of benefits to Chan’s basic typology (alongside the collection of biophysical and economic data as well as community aspirations) will, we hope, assist in this task. A systematic treatment of values and benefits, as shown above, accompanied by eco-hydrological analysis and economic valuation is an essential first step in operationalising the ES approach in water planning to meet the broad range of values embedded in aquatic landscapes.

Conclusion

Assessing the cultural values of the Brewarrina Aboriginal fish traps illustrates the multiple approaches and the kinds of data that could support water planning in addressing the values, needs, and aspirations articulated by indigenous people. The fish traps are a product of human ingenuity, and the society that devised, maintained and continues to manage them believes that the fish trap and billabong system was created by the ancestor being, Baiame, during the Dreamtime. Furthermore, the integrity and utility of that system are dependent on sufficient hydrological flows and on human observance of custom and law. From this perspective, maintaining socio-ecological system productivity, and the benefits the system provides, demands attention to social relations and ethics of care and reciprocity between people, place, ancestors and non-human nature. The data therefore demonstrates the significance of connectivity, incorporating connectivity between: people and water; past, present and future; people and ancestors (human and non-human); and local, reach and basin-scale hydrological and ecological processes (Maclean et al. Citation2012).

In some ways, this emphasis on connectivity reflects the integrative intentions of the ES approach in linking ecology with human well-being. As demonstrated here, the application of the ES approach, specifically the identification and categorisation of cultural ES benefits, can be a useful exercise in identifying what may otherwise be treated by separate legislative instruments (e.g. cultural heritage and water planning respectively). In this respect, although highly constrained in its scope, the framework can serve an initial unifying purpose. However, taking connectivity in the more extended sense of deep inter-relationships and flows between people, places, times, and physical and metaphysical entities provides a more extensive challenge to conventional valuation methods. In general, we found that indigenous values pertaining to holism and connectivity are not well represented in scholarly efforts to categorise cultural ES, suggesting that this is a particularly difficult question for the approach to accommodate.

The challenge of incorporating connectivity highlights the wider question of equity and justice in ES assessments. We define justice as encompassing: the initial identification of whose values and benefits are included in assessments (non-indigenous tourists, farmers, present-day Ngemba people, future generations, etc.); how the benefits of cultural ES are perceived to flow; and therefore the decisions that are taken to ensure the ongoing protection of such benefits. Given contemporary debates about the merits of ES approaches, studies such as this which use diverse human cultural attachments to land and waterscapes to challenge and interrogate ES frameworks can be useful in unsettling the Eurocentric, neoliberal ontological distinction between nature as producer of goods and services and humans as consumers which lies at the heart of the concept (Jackson & Palmer Citation2014). Therefore, the relative capacity of such assessments to make particular cultural perspectives visible is directly related to the level of equity and justice that management decisions based on such assessments can reasonably affect. The growing significance of the ES approach in NRM decision making means that sensitivity to the kinds and scope of perspectives ES frameworks can enable (and disable) is an increasingly important issue.

Acknowledgements

We thank both organisations and the Ngemba community. We also thank Dr Matthew Colloff, CSIRO, and Emeritus Professor Angela H. Arthington, Griffith University, for reviewing an earlier version of this paper and for the helpful advice of two anonymous reviewers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2. A billabong is an ox bow lake that fills periodically during flood flows.

3. Indigenous Australians who have gained recognition of ownership to their traditional country can enter into an agreement with the Australian Government to promote biodiversity and cultural resource conservation (see Australian Government Citation2013).

4. Fieldwork was undertaken with the Ngemba community on three separate trips in 2011 and 2012. The research plan was approved by CSIRO’s Human Ethics Committee. A research agreement was negotiated with the Ngemba Billabong Restoration and Landcare Group; it included a process for free and prior informed consent.

References

- Adamowicz W, Beckley T, Hatton MacDonald D, Just L, Luckert M, Murray E, Phillips W. 1998. In search of forest resource values of indigenous peoples: are nonmarket valuation techniques applicable? Soc Nat Res Int J. 11:51–66.

- Australian Government. 2013. Indigenous protected areas [Internet]. [revised 2014 Jan 15]. Available from: http://www.environment.gov.au/indigenous/ipa/

- Avery J. 1993. From preservation of land to land rights: the relevance of land rights to protection of Aboriginal sacred sites. In: Bartlett R, editor. Resource development and Aboriginal land rights, centre for commercial and resources law. Perth (WA): University of Western Australia; p. 113–129.

- Barber M. 2005. Where the clouds stand: Australian Aboriginal attachments to water, place, and the marine environment in Northeast Arnhem land [PhD Thesis]. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Bark R, Garrick D, Robinson C, Jackson S. 2012. Adaptive basin governance and the prospects for meeting Indigenous water claims. Environ Sci Policy. 19–20:169–177.

- Basin Plan. 2012. Water Act 2007 – Basin Plan 2012. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Bateman I, Lovett A, Brainard J. 2003. Applied environmental economics. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Bateman IJ, Harwood AR, Mace GM, Watson RT, Abson DJ, Andrews B, Binner A, Crowe A, Day BH, Dugdale S, et al. 2013. Bringing ecosystem services into economic decision-making: land use in the United Kingdom. Science. 341:45–50.

- Bradley J. 2010. Singing saltwater country: journey to the songlines of Carpentaria. Melbourne: Allen and Unwin.

- Brown PJ, Manfredo MJ. 1987. Social values defined. In: Decker DJ, Goff GB, editors. Valuing wildlife: economics and social perspectives. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; p. 12–23.

- Brown TC. 1984. The concept of value in resource allocation. Land Econ. 60:231–246.

- [BSC] Brewarrina Shire Council. 2011. Brewarrina 2022: community strategic plan for Brewarrina Shire. Brewarrina (NSW): Brewarrina Shire Council; p. 37.

- Byrne D, Brayshaw H, Ireland T. 2003. Social significance: a discussion paper. Hurstville: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Research Unit, Cultural Heritage Division.

- Chan KMA, Satterfield T, Goldstein J. 2012. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol Econ. 74:8–18.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2005. Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No. S 94, June 3, 2005 [Internet]. [revised 2014 Aug 5]. Available from: http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/ba18eab5-1a30-4f5d-af0d-d3f555f56b83/files/105778.pdf

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2011. Water Act 2007. An Act to make provision for the management of the water resources of the Murray–Darling Basin, and to make provision for other matters of national interest in relation to water and water information, and for related purposes. Act No. 137 of 2007 as amended. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2012. Water Amendment (Long-term Average Sustainable Diversion Limit Adjustment) Bill. A Bill for an Act to amend the Water Act 2007 in relation to long-term average sustainable diversion limits, and for related purposes. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- de Groot RS, Wilson MA, Boumans RMJ. 2002. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol Econ. 41:393–408.

- English A. 2002. More than archaeology: developing comprehensive approaches to Aboriginal heritage management in NSW. Aust J Environ Manage. 9:218–227.

- Finn M, Jackson S. 2011. Protecting Indigenous values in water management: a challenge to conventional environmental flow assessments. Ecosystems. 14:1232–1248.

- Fisher B, Turner K, Zylstra M, Brouwer R, Groot RD, Farber S, Ferraro P, Green R, Hadley D, Harlow J, et al. 2008. Ecosystem services and economic theory: integration for policy-relevant research. Ecol Appl. 18:2050–2067.

- Graeber D. 2001. Toward an anthropological theory of value: the false coin of our own dreams. New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Hamstead M. 2011. Improving Water Planning Processes: priorities for the next five years in Connell D. In: Grafton Q, editor. Basin futures. Water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Hatton MacDonald D, Bark R, MacRae A, Kalivas T, Grandgirard A, Strathearn S. 2013. An interview methodology for exploring the values that community leaders assign to multiple-use landscapes. Ecol Soc. (special issue) 18:29.

- Heberlein TA. 1981. Environmental attitudes. Zeitschrift fur Umweltpolitik. 2:241–270.

- Jackson S. 2006. Compartmentalising culture: the articulation and consideration of Indigenous values in water resource management. Aust Geogr. 37:19–31.

- Jackson S. 2011. Indigenous water management in the Murray-Darling Basin: priorities for the next five years, in Grafton Q. In: Connell D, editor. Basin futures: water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin. Canberra: ANU E-Press; p. 163–178.

- Jackson S, Barber M. 2013. Recognition of indigenous water values in Australia’s northern territory: current progress and ongoing challenges for social justice in water planning. Plann Theory Pract. 14:435–454.

- Jackson S, Langton M. 2012. Trends in the recognition of indigenous water needs in Australian water reform: the limitations of ‘cultural’ entitlements in achieving water equity. J Water Law. 22:109–123.

- Jackson S, Moggridge B, Robinson C. 2010. The effects of change in water availability on Indigenous communities of the Murray-Darling Basin: a scoping study. Report to the Murray-Darling Basin Authority. Canberra: CSIRO; 190 pp.

- Jackson S, Palmer L. 2014. Reconceptualizing ecosystem services: possibilities for cultivating and valuing the ethics and practices of care. Prog Hum Geogr. doi:10.1177/0309132514540016

- Jepson P, Canney S. 2003. Values-led conservation. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 12:271–274.

- Johnston B, Hiwasaki L, Klaver I, Ramos Castillo A, Strang V, editors. 2012. Water, cultural diversity, and global environmental change. Paris: UNESCO-IHP and Springer.

- Johnston RJ, Segerson K, Schultz ET, Besedin EY, Ramachandran M. 2011. Indices of biotic integrity in stated preference valuation of aquatic ecosystem services. Ecol Econ. 70:1946–1956.

- Jones D. 2011. The water harvesting landscape of Budj Bim and Lake Condah: whither world heritage recognition. In: Elkadi H, Xu L, Coulson J, editors. Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference of the Association of Architecture Schools of Australasia, Geelong, VIC: Deakin University, School of Architecture & Building; p. 131–142.

- Keeler BL, Polasky S, Brauman KA, Johnson KA, Finlay JC, O’Neill A, Kovacs K, Dalzell B. 2012. Linking water quality and well-being for improved assessment and valuation of ecosystem services. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:18619–18624.

- King TF. 1998. How the archeologists stole culture: a gap in American environmental impact assessment practice and how to fill it. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 18:117–133.

- Kroeber AL, Kluckhohn C. 1952. Culture: a critical review of concepts and definitions. Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology Papers, 47. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University.

- Maclean K, Bark RH, Moggridge B, Jackson S, Pollino C. 2012. Ngemba water values and interests Ngemba old mission Billabong and Brewarrina aboriginal fish traps (Baiame’s Nguunhu). Canberra: CSIRO.

- Maclean K, Robinson CJ, Natcher D. 2014. Consensus building or constructive conflict? Aboriginal discursive strategies to enhance participation in natural resource management in Australia and Canada. Soc Nat Res. 1–15. doi:10.1080/08941920.2014.928396

- Mathews RH. 1907. Notes on the Aborigines of New South Wales. Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer.

- McIntyre-Tamwoy S. 2004. Social value, the cultural component in natural resource management. Aust J Environ Manage. 11:289–299.

- MDBA. 2012. Sustainable Rivers Audit 2: the ecological health of rivers in the Murray–Darling Basin at the end of the Millennium Drought (2008–2010). Summary. Canberra: Murray-Darling Basin Authority.

- [MEA] Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. . Ecosystems and Human Well-being: synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Muir C, Rose D, Sullivan P. 2010. From the other side of the knowledge frontier: indigenous knowledge, social–ecological relationships and new perspectives. Rangeland J. 32:259–265.

- [NOAA] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1996. Natural resource damage assessments. 15 CFR Part 990. Final rule. Fed Reg. 61(4):440–510.

- Norton B. 2000. Biodiversity and environmental values: in search of a universal earth ethic. Biodivers Conserv. 9:1029–1044.

- NSW. 2012. Water sharing plan for the Barwon-Darling unregulated and alluvial water sources 2012 [Internet]. [cited 2014 Nov 18]. Available from: http://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/viewtop/inforce/subordleg+488+2012+cd+0+N/

- NWC. 2011. National water planning report card 2011, Canberra: National Water Commission.

- O’Brien M, Guerrier Y. 1995. Values and the Environment: an Introduction. In: Guerrier Y, Alexander N, Chase J, O’Brien M, editors. Values and the environment: a social science perspective. London: John Wiley; p. xiii/xvii.

- Pearce D. 1993. Economic values and the natural world. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Reser JP, Bentrupperbäumer J. 2005. What and where are environmental values? Assessing the impacts of current diversity of use of ‘environmental’ and ‘World Heritage’ values. J Environ Psychol. 25:125–146.

- Rolfe J, Windle J. 2006. Valuing Aboriginal cultural heritage across different population groups. In: Rolfe J, Bennett J, editors. Choice modelling and the transfer of environmental values. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; p. 216–244.

- Roughley TC. 1951. Fish and fisheries of Australia. Sydney: Angus and Robertson; p. 322.

- Ruiz-Frau A, Hinz H, Edwards-Jones G, Kaiser MJ. 2013. Spatially explicit economic assessment of cultural ecosystem services: non-extractive recreational uses of the coastal environment related to marine biodiversity. Marine Policy. 38:90–98.

- Satz D, Gould RK, Chan KMA, Guerry A, Norton B, Satterfield T, Halpern BS, Levine J, Woodside U, Hannahs N, et al. 2013. The challenges of incorporating cultural ecosystem services into environmental assessment. AMBIO. doi:10.1007/s13280-013-0386-6

- Strang V. 1997. Uncommon ground: cultural landscapes and environmental values. Berg: Oxford.

- Tallis H, Guerry A, Daily GC. 2013. Ecosystem services. In: Levin SA, editor. Encyclopaedia of biodiversity. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; p. 96–104.

- Tan P, Jackson S. 2013. Impossible dreaming: does Australia’s water law and policy fulfil Indigenous aspirations? Environ Planned Law J. 30:132–149.

- TEEB. 2010. The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: ecological and economic foundations. London: Earthscan.

- Weir J. 2009. Murray River Country: an ecological dialogue with traditional owners. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Zander KK, Garnett S, Straton A. 2010. Trade-offs between development, culture and conservation-willingness to pay for tropical river management among urban Australians. J Environ Manage. 91:2519–2528.