Abstract

We examined existing policy instruments of the Indian forest, wildlife, and environment sectors for the period 1927–2008 to (a) assess their strengths and weaknesses in addressing information, market and policy failures in ecosystem service provision in the Indian Himalayan region and (b) determine if they were informatory or regulatory in nature and whether they encouraged the use of market-based instruments. Our analysis revealed that Indian policy measures can be categorized into four eras: Production (1927–1972), Protection (1972–1988), Community Participation (1988–2006), and Climate Change and Globalization (2006 onwards). The policies of the earlier two eras were largely regulatory in nature. From 1988 onwards, community participation in biodiversity conservation has made the policies more informatory and market-based. The recognition that Himalayas are a distinct ecosystem, crucial for their services but vulnerable to climate change impacts, has come about only with the National Mission on Sustaining Himalayan Ecosystem. Given the multiple stakeholders in Indian Himalayas and the off-site nature of ecosystem services, a complementarity of instruments and their ability to address the consequences of local decisions on downstream ecosystem services are essential. A participatory and sectorally coordinated mixed governance approach is needed to sustain ecosystem services in the region.

1. Introduction

The concept of ecosystem services has become an important model for linking the functioning of ecosystems with human well-being (Fisher et al. Citation2009). But even as demand for ecosystem services is growing, human actions are diminishing the capability of ecosystems to meet these demands. Sound natural resource management strategies can often reverse ecosystem degradation and enhance the contributions of ecosystems to human well-being (MEA Citation2005). In recent years, a large and rapidly growing body of research has been seeking to identify, characterize and value ecosystem goods and services (Bagstad et al. Citation2013) and strategize ways to ensure their continuous provision.

A study conducted by UNEP-WCMC indicated that there is a high degree of coverage of ecosystem services in policy instruments but this is still inadequate because the concept of ecosystem services evolved recently and there are constraints to defining, assessing, and regulating impacts on ecosystem services (CBD & UNEP-WCMC Citation2012). The understanding of the complementarities and inter-linkages of ecosystem services is limited (Pagiola et al. Citation2004). Consequently, they have largely been ignored in both domestic and international markets and land-use law and policy decisions (Barbier Citation2007; TEEB Citation2010). Till recently, international and national legislative measures were not designed to safeguard ecosystem services. Hence, the negative impacts of development policies often resulted in repercussions for the availability and provision of ecosystem services.

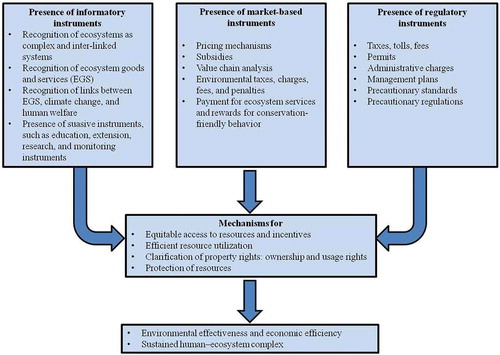

Current ecosystem-based approaches have suggested that policies and measures be adopted that take into account the role of ecosystem services in reducing societal and ecological vulnerability through multi-sectoral and multi-level approaches (Andrade et al. Citation2011). Economists, environmentalists, and lobbyists have proposed various types of policy mix (), arguing that ‘single-instrument’ or ‘single-strategy’ approaches are misguided and when used individually fail to address complex causes of ecosystem service degradation (e.g. Gunningham & Sinclair Citation1999; Ring & Schroter-Schlaak Citation2011).

Figure 1. Indian policy instrument mixes for natural resource conservation and their expected outcomes.

The policy mix approach works toward building and working with the strengths of individual instruments, even as it compensates for their weaknesses through additional or complementary instruments. Gunningham and Young (Citation1997) classified the policy instruments as being (a) motivational that shift individual and community preference functions and (b) informative that inform people about relationships between resource management practice and the environment.

The literature dealing with policy issues on ecosystem services (Goulder & Parry Citation2008; de Groot et al. Citation2010; Ring & Schroter-Schlaak Citation2011) addresses policy instruments as following:

Regulatory, which aim to regulate the use of natural resources through protection and planning. They include provision of permits, zoning or planning, and control of environmentally degrading activities. Regulatory approaches can promote efficiency, but they inhibit innovation and impose unnecessary costs.

Market-based instruments (MBIs), which aim to introduce behavioral change by changing prices in existing markets rather than through explicit directives and by specifying the revised rights and obligations. MBIs can be price based or quantity based (such as environmental taxes, charges, fees, and penalties that will internalize negative externalities), payment for ecosystem services, and rewards for conservation-friendly behavior. Taxes, subsidies, tradable permits, and auctions of property rights are a few MBIs that economists have long recommended for efficient environmental policy-making (Seccombe-Hett Citation2000; Badola et al. Citation2014).

Informative and motivational, such as education, extension, research, and monitoring, which aim to inform communities about the relation between human activities and their impact on the environment.

International debates on strategies to sustain ecosystem services have emphasized the need to revisit natural resource policies and legislative measures to ensure that they contain regulatory mechanisms and backups in the form of MBIs and motivational approaches. This need is more pronounced for the Himalayas, which are (a) important for the lives and livelihood security of a large number of people, (b) critical for sustaining provisioning, regulatory, and supportive functions of other ecosystems, and (c) fragile.

The Indian Himalayas are one of the richest and most complex regions in the world from geological, biological, and cultural points of view. They cover approximately 5,91,000 km2 or 18% of India’s land surface. Located at the junction of the Palearctic, Afro-Tropical and Indo-Malayan realms, they are widely considered to be one of the global hotspots of biodiversity and account for 50% of India’s forests and 40% of the species endemic to the Indian sub-continent (Semwal et al. Citation1999). The Himalayas are the water tower of the Indian sub-continent. Major rivers of the region have their origin here (Government of India Citation2010). The Himalayas provide vital ecosystem services for the ecological and economic security of the people living downstream. They are a repository of geological and agricultural assets and harvested wild goods, besides being a center of cultural, social, and religious identity to a large number of people (Saxena et al. Citation2001; Birch et al. Citation2014). However, the Himalayas are also one of the most degradation-prone and fragile mountain ranges in the world. They are more vulnerable due to geological reasons, the stress caused by the increasing human population, exploitation of natural resources, and effects of climate change, which have multifaceted repercussions on human well-being (Liu & Chen Citation2000; Dyurgerov & Meier Citation2005). The temperature increase is predicted to be more noticeable in the Himalayan region (INCCA Citation2010; Singh et al. Citation2011) with resultant impacts such as glacial melts, sediment mobilization, drought, landslides, and flash floods (Dale et al. Citation2001; Wulf et al. Citation2012). These impacts have resulted in reduced productivity of natural and human modified ecosystems, loss of tourism revenue, infrastructure and food and water security for the communities living in the region (WHO Citation2012; Badola et al. Citation2014; Smith Citation2014) Notwithstanding all this, the Himalayas have remained at the periphery of policy space (http://himlayaforum.org). The failure to recognize the economic value of the Himalayan ecosystem services and to address the issues of sustainability using policy tools has been cited as the primary cause of the continued degradation of this vulnerable ecosystem (Singh Citation2002; Blaikie & Muldavin Citation2004). There is increasing concern that this apathy will lead to a rapid decline in the provisioning, regulatory, supporting, and cultural services of this region and adversely impact the provision of ecosystem services downstream. Numerous scientific and political forums have underpinned the uniqueness, environmental challenges, and political legacies of the Himalayan region and the need to address the extremely diverse environmental threats faced by the region in policy-making (Blaikie & Muldavin Citation2004; Gautam et al. Citation2013).

The objectives of this review are to (a) analyze the existing policy instruments of the forest, wildlife, and environment sector for their strengths and weaknesses in addressing the challenges of ecosystem service management in the Himalayas and (b) identify the policy gaps or failure of the policies as informatory, market-based, and regulatory instruments for promoting sustainable management of ecosystem services in the region.

2. Approach and methods of analysis

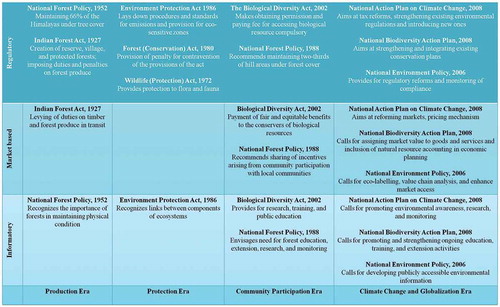

In India, the natural resource sector is largely governed by the policies of the forest, wildlife, and environment sector; however, the policies of other sectors, such as rural development, agriculture, tribal affairs, and defense also impact it. We restricted this review only to the acts and policies of the forest, wildlife, and environment sector of the Government of India that have a bearing on the Himalayan region ().

Table 1. List of environmental acts and policies of India examined for this analysis.

The analysis covers a period of about 90 years, from the enactment of the Indian Forest Act, 1927 (IFA) (which forms the basis of subsequent forest acts and policies), to the promulgation of the National Action Plan on Climate Change, 2008 (NAPCC). The NAPCC is the first policy document in India that deals with the Himalayas as a separate and crucial ecosystem. Based on the key national policy milestones we divided the period from 1927 to 2008 into four eras ():

Production Era (1927–1972): During this period, forest management was closely linked with commercial interests since the ‘need for realization of maximum annual revenue from forests’ was considered vital and the relevance of forests in meeting the needs of development and foreign trade during the colonial and post-colonial period was given prominence in managing forests.

Protection Era (1972–1988): This was the period when the degradation of forests was realized and highlighted by conservationists in India and measures were taken to provide legal protection to the flora and fauna in their natural habitat.

Community Participation Era (1988–2006): The National Forest Policy (NFP), 1988, was a total turnaround in the government’s stand on local people and forests. It was the initiation of community participation in forest and wildlife management. The policies and acts formed during this era recognized and legalized the links between human welfare and natural ecosystems.

Climate Change and Globalization Era (2006 onwards): It was only with the promulgation of the National Environment Policy, 2006 (NEP), that the impacts of climate change were addressed. A further step in this direction was the promulgation of the NAPCC.

Figure 2. The four eras of forest, wildlife, and environment sector policies in India and the focus of policy instruments.

For this study, the term ‘policy’ is defined as a system of law, regulatory measure, or course of action concerning conservation of natural resources and the environment. The term ‘policy instrument’ refers to a set of guidelines adopted by the state to implement and achieve the desired effect of a particular policy, while the term ‘governance’ is used for the formal and informal institutions used to manage natural resources and environment. Original policy documents were examined to understand the nature of the instruments used for managing natural resources and to address information, market, and policy failures in ecosystem service provision in the Himalayas and to evaluate if the policies are informatory or regulatory in nature and whether they encourage the use of MBIs. Additionally, the published literature and government records were also consulted to substantiate the aforesaid material.

Each document was further assessed on the basis of the following parameters: whether the policies (a) recognize the Himalayas as a complex and inter-linked system, (b) recognize the Himalayas as a provider of ecosystem goods and services, (c) recognize the linkages between the goods and services provided and their vulnerability to climate change, (d) have provisions for suasive instruments, such as dissemination of information, training and extension, education, and research, (e) contain regulatory measures such as permits, administrative charges, formulation of management plans, and setting of standards needed for protecting the ecosystem and its components, (f) encourage the use of MBIs, such as consistent pricing, value chain analysis, subsidies, and quality checks, and (g) clarify property rights through public provisions, specifying ownership and use rights. The indicators ‘a–d’ indicate that a document is informatory; ‘e’ indicates a regulatory document; and ‘f–g’ indicate that a policy is market based.

3. Results

3.1. Changing dimensions of policies and legislative measures impacting ecosystem services

The present environmental legislative framework of India broadly comes under the purview of the Environment Protection Act, 1986 (EPA). The law related to management of forests and wildlife is contained in the IFA, Forest Conservation Act, 1980 (FCA), and Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (WPA). The forest policy of the country has been shaped by its colonial and post-colonial circumstances (Badola Citation1995). The directives of colonial forest policy were governed by considerations of imperialism and commercialism, that is, meeting the need for wood for railways and for the two world wars and assuring a steady revenue for the state. For example, the IFA, specifically denied people any rights over forest produce ‘simply because they were domiciled there’ (Table S1). Independence made little difference to the position of people in relation to forests. The NFP, 1952, retained the concept of ‘reserved forests’, now justified in the name of ‘national need’, and placed such forests under the exclusive control of the forest department (Arora Citation1994). The NFP, 1952, asserted the ‘need for realization of maximum annual revenue from forests’, and the relevance of forests in meeting the needs of defence, river valley projects, industry, and communication were emphasized. Although these and subsequent policy statements mention the need for maintaining the ecological integrity of forests, the approach of the state continued to reflect a lack of recognition of ecosystem services, focusing only on exploitable forest products. Villagers lost their sense of ‘belongingness’ to the forest and came to feel that any self-denial they might exercise in using the forest would simply end up in the forest being appropriated by the government. While traditional institutions continued to exist, their role as mechanisms for regulating resource use among their members became more or less redundant. Thus, common property resources under communal control now became open access resources and were consequently liable to be used in an exhaustive manner (Gadgil & Iyer Citation1989). This was a classic case of market and policy failures.

With the enactment of the WPA and the launch of Project Tiger the same year, there was a steady increase in the area under national parks and sanctuaries with an implicit focus on maintaining the natural systems. However, the approach to forest and wildlife conservation focused on patrolling by guards and imposition of penalties to discourage encroachment and illegal activities. Commonly, the people living in and around forest areas were the relatively poor inhabitants of agricultural villages. Even if they had other sources of income, which were most often seasonal, given their limited purchasing power, they depended totally on the surrounding forest for their fuel, fodder, timber, and, sometimes, food requirements. The result was a number of protests and social conflicts over forest resource use. This and the failure of the state to control degradation of forests through its traditional policing approaches were important factors in reorienting natural resource management policy toward people’s participation (). The subsequent amendments to the WPA in 2002, 2006, and 2013 addressed these issues and created space for incorporating human livelihood and development concerns in wildlife conservation (Table S1).

In the NFP, 1988, for the first time it was emphasized that the forests were not to be commercially exploited but were to contribute to conservation of soil and the environment and meet the subsistence needs of local people. However, this approach was largely driven by the tenets of involving local communities in forest management and meeting their needs rather than securing the provision of ecosystem services. Yet, it did open the way for correcting the market and policy failures related to ecosystem services, albeit indirectly. The recent policy, the NAPCC, has recognized the fact that climate change may ‘alter the distribution and quality of India’s natural resources and adversely affect the livelihood of its people’. Among its guiding principles is ‘engineering new and innovative forms of market, regulatory and voluntary mechanisms to promote sustainable development’ (Government of India Citation2008). Each of India’s 35 states and union territories has been asked to prepare a state-level action plan as an extension of the NAPCC contextualized within local governance constraints (INCCA Citation2010; Smith Citation2014). Acknowledging the challenge due to climate change and the commitment of the government to address these, the union Ministry of Environment and Forests was renamed as Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change. The Ministry on 14 October 2009 launched the Indian Network for Climate Change Assessment (INCCA). The INCCA was conceptualized as a network-based scientific program designed to assess the drivers and implications of climate change through scientific research, and develop decision support systems and capacity for management of climate change-related risks and opportunities.

Through the National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem (NMSHE), the NAPCC recognizes the loss of ecosystem services of the region and its vulnerability to climate change and aims to conserve biodiversity, forest cover, and other ecological values of the Himalayas. A detailed analysis of the key features, strengths, and weaknesses of the policies impacting the Himalayan region has been provided in Table S1.

3.2. Inter-sectoral legislative measures

The efforts of the forest department and the rural department to achieve inter-sectoral cooperation for managing natural resources, particularly in hill areas, resulted in the implementation of the Integrated Watershed Development Program, which aimed at economic improvement of the local communities and protection of watersheds. The Guidelines for Watershed Development, 2000, covered the various watershed development schemes of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Environment and Forests and Climate Change. The common guidelines thus propagated the holistic area-oriented Integrated Watershed Development (IWD) involving comprehensive treatment plans including soil and moisture conservation, water harvesting structures, horticulture and pasture development, and upgrading of existing common property resources. The IWD recognizes the multiple functionality of the watersheds, involves local people in the decision-making process, ensures equitable access to resources, and promotes multi-layered and multi-stakeholder involvement; yet, it does not address the uncertainties due to climate change and does not account for settling of rights in places where protected areas were created. The implementation of recent policies such as the NEP, National Biodiversity Action Plan (NBAP), and the NAPCC hinges on substantial inter-sectoral coordination.

3.3. Efficacy of policy instruments in ecosystem service management

The Indian environmental and forest policy has been modified from time to time to adapt it to changing political–economic conditions. It has substantially contributed toward minimizing environmental degradation and maintaining the ecological integrity of natural systems. While the policies of the Production Era were largely focused on marketable goods such as timber and non-timber forest products (NTFPs) provided by natural ecosystems, those of the Protection Era were largely regulatory and focused on a ‘hands-off’ approach as far as natural ecosystems were concerned (). In the policies promulgated during these two periods, informatory and market instruments remained in the backseat. In the IFA, policy implementation was in the form of levying duty on timber and forest produce. A clear mention of ecosystem services and well-defined rules for protecting and enhancing them came only with the NEP. All subsequent action plans and programs of the Indian Government have identified maintaining the sustainability of ecosystem goods and services as being their primary agenda. However, the need for a concerted policy focus on the Himalayas due to their ecological characteristics, human interface, and vulnerability to climate change, was addressed only by the NAPCC.

3.4. Policy as informatory instruments

The NFP, 1952 was the pioneer law that recognized the Himalayas as complex and interlinked ecosystems. It also recognized the importance of forests for continued provision of water and for human well-being. However, till 1988, the laws acknowledged only timber and NTFPs (goods) and their contribution to human well-being. The NFP, 1988, recognized the provision of both goods and services by forests. Except for the NEP and the NAPCC, the policies have remained silent on the linkages between the ecological health of the Himalayas, climate change, and human well-being.

It is clear that none of the policies recognized the multifunctional aspects of the Himalayas and the challenges of the impacts of climate change on them or related opportunities. The NAPCC has provisions for sustaining the Himalayan region through conservation of biodiversity and restoration of the forest cover and other ecological values. The NBAP drew attention towards valuation of ecosystem services provided by natural ecosystems and suggested the use of valuations in national accounting and decision-making processes (Table S2).

3.5. Policy as market instruments

MBIs have been used in Indian forest sector laws since 1927, when the IFA made provisions for levying duty on forest produce in transit. The WPA provides a comprehensive list of wild plants and animals that cannot be traded. The NFP, 1988, Biological Diversity Act, 2002 (BDA), NEP, NBAP, and NMSHE provide measures for reducing the environmental impacts on and unsustainable use of ecosystem goods and services. These legislative measures emphasize the need for incorporating the cost of depletion of natural resources in the decisions of economic actors to reverse the tendency to treat these resources as ‘free goods’ and to pass the costs of degradation to other sections of society or to future generations thus integrating environmental concerns in economic and social development.

The NFP, 1988, BDA, NEP, and NBAP are legislative and guiding measures for ensuring equitable incentive sharing. The NFP, 1988, encourages substitution of wood and efficient utilization of forest produce, including non-wood forest products, to meet national needs. It is now increasingly recognized that efficiency in the production and use of goods and services can be improved by having a proper mountain-specific value chain analysis of a mountain ecosystem’s goods and services, such as medicinal and aromatic plants and livestock products (Hoermann et al. Citation2010; Badola et al. Citation2011). The NEP and NBAP aim to ensure efficient use of environmental resources by incorporating economically feasible and socially acceptable incentives such as value addition and direct markets. The NBAP provides examples of approaches incorporating value chain analysis and value addition in attaining sustainable development and economic uplift of local communities (Table S2).

3.6. Policy as regulatory instruments

The IFA and the WPA advocated limited and restricted use of forest and natural resources to ensure the protection of natural resources. The policies emerging from the forestry sector have laid particular emphasis on maintaining the integrity of ecosystems by containing any destructive activity, such as grazing, within limits. The National Forest Policies of 1952 and 1988 provide for maintaining tree cover on the hill and non-hill regions of the country through afforestation plans. The FCA has a provision of imposing penalties for contravention of its provisions through imprisonment. The EPA lays down emission standards. The ‘polluter pays’ principle emerges in the EPA, wherein a person responsible for a discharge of an environmental pollutant exceeding the prescribed limits is bound to pay for the remedial measures incurred during the abatement of the pollutant. The BDA ensures regulated access to biological resources by levying charges and mandating permissions for accessing or collecting biological resources for commercial purposes. The NEP provides for regulatory reforms: revisiting the policy and legislative framework to follow a holistic and integrated approach to the management of the environment and natural resources; inclusion of environmental considerations in sectoral policy-making; and strengthening of relevant linkages among various agencies at the central, state, and local self-government levels charged with the implementation of environmental policies. It recommends the implementation of multi-stakeholder partnerships involving the forest department, land-owning agencies, local communities, and investors, with obligations and entitlements clearly defined for each partner (Table S2).

3.7. Regulation of property rights

Previous legislative measures, such as the Indian Forest Policies of 1894 and 1952 and the IFA governed as they were by colonial and commercial interests, failed to address equitable access to the Himalayan resources since these measures brought land resources under government rule and ownership, alienating local communities. The National Commission on Agriculture, 1976, recommended that a social forestry program be promoted to meet the needs of user groups and provided for differential institutional arrangements for different stakeholder groups outside the limits of reserved and protected forests. These recommendations are reflected in the forest policies framed in1988 and afterwards.

Regulation and clarification of property rights (ownership and use rights) are considered crucial when dealing with the issue of market failure arising due to the notions of ‘free goods’ and ‘easy access’. Nonetheless property rights, particularly the usage rights of local communities, have remained ambiguous in almost all the policies although the FCA and NEP provide for legal recognition of traditional entitlements of forest-dependent communities. The FCA prohibits interference with the rights of local communities, such as Nistar rights (land set apart to meet the requirements of fuel, fodder, timber, and other necessities) (Ramanathan Citation2002) or concessional use rights provided under the IFA. The BDA and NEP provide for securing the intellectual property rights of conservers of biological resources and local communities, respectively (Table S2).

The Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA), of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs seeks to clarify the rights of forest-dwelling communities. Contradictions and a lack of coherence between the objectives of the policies of the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change and the Ministry of Tribal Affairs have led to more confusion. The National Forest Commission, 2003, is of the opinion that recognition of the FRA will be harmful to the interests of forests and the ecological security of the country, and it would be bad in law and in open conflict with the rulings of the Supreme Court in 2000. Legislation, therefore, needs to be framed to provide forest-dwelling communities a right to a share of forest produce on an ecologically sustainable basis.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The NFP, 1952, was a pioneer in recognizing the link between forests, denudation of the Himalayas, and their contributions to human well-being. Therefore, it advocated maintaining 66% of the Himalayas under tree cover. Yet, the need to place a market value on goods and services provided by natural ecosystems received attention through the NEP and NBAP only when these became buzzwords. The NEP echoed the need to include natural resource accounting in economic decisions, and the NBAP called for valuation of biodiversity as an integral part of pre-appraisal of projects. But most conservation plans focus on biodiversity and ignore the importance of ecosystem services (Singh Citation2002). Using the biodiversity approach may neglect areas that are degradation prone and are crucial for human welfare. However, to adapt and mitigate environmental degradation and climate change impact, policies based on prevailing scientific information are needed (Hertin et al. Citation2007; Eriksson et al. Citation2009).

The lack of understanding regarding the role of the Himalayas in providing ecosystem services and their contribution to human well-being has created an information gap about the opportunity costs of putting land to different uses, namely conservation, agriculture, development, and tourism. To manage or regulate ecosystem services, it is important to have information about their quantity, quality, and economic worth (PCAST Citation2011). Resource uses create markets, and vice versa, and pricing and incentive mechanisms regulate these processes (TEEB Citation2010). Although putting a price on ecosystem services may not be enough to ensure their sustainability, this step may modify ‘everyday behaviour and decisions toward a future in which nature is no longer seen as a luxury we cannot afford, but as something essential for sustaining and improving human well-being everywhere’ (Daily et al. Citation2009).

Our analysis reveals that the Indian legislative measures and policy have so far been regulatory in nature. It was more prominent in the policies of the Production and Protection eras, which aimed at controlling the forest and forest produce to derive the maximum revenue and conserving them through a conventional ‘isolationist approach’ (Pretty & Pimbert Citation1995). The policies of the Community Participation era had informatory and market instruments to some extent. It is only in the recent era of Climate Change and Globalization that all the three instruments are being addressed, albeit the focus remains regulatory. Property rights, particularly usage rights of local communities, have remained ambiguous in almost all the policies, although the NEP provides for legal recognition of traditional entitlements of forest-dependent communities. None of the earlier policies addressed the issue of differential institutional arrangements to manage different ecosystems or the issues of climate change. For sustainable environmental governance, the informatory, regulatory, and market instruments need to have positive synergistic interactions. Because of the cross-cutting nature of ecosystem services, they are not confined to a single subject or a single administrative agency, department, or ministry; their management and sustainability require national commitments and a policy portfolio approach combining several measures (Gunningham & Young Citation1997; Dernbach & Mintz Citation2011; Ring & Schroter-Schlaak Citation2011). In the context of the Himalayas, the above is reflected in the NAPCC through the NMSHE that proposes to network knowledge institutions to develop a coherent database on scientific and social dimensions of conserving the Himalayas; detect and decouple natural and anthropogenic causes of environmental change; assess the consequences of climate change and study traditional systems for community’s adaptation to it; develop sustainable tourism and resource development; raise awareness among stakeholders in the region; assist states in the Indian Himalayan region with informed actions; and develop regional cooperation with neighboring countries (Government of India Citation2010; Smith Citation2014). However, the success of implementation of NMSHE remains to be seen.

To achieve the goals of biodiversity conservation and ecosystem service provision, policies need combinations of instruments that protect natural ecosystems through direct regulation (or command-and-control), economic (or price-based) instruments that provide positive incentives to promote the compatibility of use with biodiversity conservation, and information provision (or moral suasion). Given the multiple uses and stakeholders in the Indian Himalayas and the off-site nature of the ecosystem services, a complementarity of instruments and an ability to address the consequences of local decisions on distant ecosystem services are essential (Seppelt et al. Citation2011; Balthazar et al. Citation2015). Acts, such as the IFA and WPA that are regulatory in nature are important for securing a safe minimum standard for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem service provision. However, given the antagonism generated due to their regulatory nature and to address the opportunity costs of ecosystem service provision and to provide information that may lead to motivation and self-regulation, effective implementation of policies (NFP, 1988; NEP; NBAP; BDA; and NMSHE) that have market-based and informatory instruments becomes important. Policy mixes are even more relevant in sustained provision of ecosystem services because multiple sector policies come into play, be it in a synergistic way or through adverse effects (Ring & Schroter-Schlaak Citation2011; Ring et al. Citation2011; Andrés et al. Citation2012).

The integration of conservation into decision-making processes will be aided by, among others, moving from confrontation to participatory efforts seeking a wide range of benefits and thereby developing a broader vision for conservation (e.g. Theobald et al. Citation2005; Manning et al. Citation2006; Goldman et al. Citation2007; Pejchar et al. Citation2007). This vision should be able to provide space for community-based self-organized systems for biodiversity conservation to co-exist along with state-imposed policies and take lessons from other countries (e.g. Ostrom et al. Citation1999).

The emerging policy framework for the Himalayas needs to address the ecological issues and human well-being in the face of growing anthropogenic pressures and climate change impacts, and develop the stakes of local communities in the conservation and maintenance of ecosystem services by promoting an enabling governance environment in the region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2015.1030694.

Supplemental Online Material

Download PDF (112.9 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the Director and the Dean, WII for logistic support. We thank friends and colleagues at the WII for discussions and comments on the earlier version of this manuscript. We greatly appreciate the constructive comments received from anonymous referees, which substantially improved the quality of this paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrade A, Córdoba R, Dave R, Girot P, Herrera-F B, et al. 2011. Draft Principles and Guidelines for Integrating Ecosystem-Based Approaches to Adaptation in Project and Policy Design: A Discussion Document. CEM/IUCN, CATIE. Kenya: Commission on Ecosystem Management, IUCN.

- Andrés SM, Mir LC, Van Den Bergh JC, Ring I. 2012. A framework for the design of conservation policies based on a scientific understanding of the relation between ecosystem services and biodiversity. Available from: www.connect-biodiversa.eu/wp-content/uploads/D5-11. pdf

- Arora D. 1994. From state regulation to people’s participation: case of forest management in India. Econ Polit Weekly. 29:691–698.

- Badola R. 1995. Critique of People Oriented Conservation Approaches in India: An Entitlements Approach. Discussion paper. Study report. IDS Sussex.

- Badola R, Barthwal S, Hussain SA. 2011. Assessment of Policies and Institutional Arrangements for Rangeland Management in the Indian Hindu Kush Himalayas. Report submitted to ICIMOD, Nepal.

- Badola R, Hussain SA, Dobriyal P, Barthwal S. 2014. An Integrated Approach to Reduce the Vulnerability of Local Communities to Environmental Degradation in Western Himalayas. Study report. Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India.

- Bagstad KJ, Semmens DJ, Waage S, Winthrop R. 2013. A comparative assessment of decision-support tools for ecosystem services quantification and valuation. Ecosyst Serv. 5:27–39. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.07.004

- Balthazar V, Vanacker V, Molina A, Lambin EF. 2015. Impacts of forest cover change on ecosystem services in high Andean mountains. Ecol Indic. 48:63–75. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.07.043

- Barbier EB. 2007. Valuing ecosystem services as productive inputs. Econ Policy. 22:178–229. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2007.00174.x

- Birch JC, Thapa I, Balmford A, Bradbury RB, Brown C, Butchart SH, et al. 2014. What benefits do community forests provide, and to whom? A rapid assessment of ecosystem services from a Himalayan forest, Nepal. Ecosyst Serv. 8:118–127. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.03.005

- Blaikie PM, Muldavin JSS. 2004. Upstream, downstream, China, India: the politics of environment in the Himalayan region. Ann Assoc Am Geog. 94:520–548. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.00412.x

- CBD, UNEP-WCMC (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre). 2012. Best policy guidance for the integration of biodiversity and ecosystem services in standards, Montreal. Tech Ser. 73:52.

- Daily GC, Polasky S, Goldstein J, Kareiva PM, Mooney HA, Pejchar L, Ricketts TH, Salzman J, Shallenberger R. 2009. Ecosystem services in decision making: time to deliver. Front Ecol Environ. 7:21–28. doi:10.1890/080025

- Dale VH, Joyce LA, McNulty S, Neilson RP, Ayres MP, Flannigan MD, Hanson PJ, Irland LC, Lugo AE, Peterson CJ, et al. 2001. Climate change and forest disturbances. BioSci. 51:723. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0723:CCAFD]2.0.CO;2

- de Groot RS, Fisher B, Christie M, Aronson J, Braat L, Gowdy J, Haines-Young R, Maltby E, Neuville A, Polasky S, et al. 2010. Integrating the ecological and economic dimensions in biodiversity and ecosystem service valuation. In: Kumar P, editor. The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: the ecological and economic foundations. London: Earthscan; p. 9–40.

- Dernbach JC, Mintz JA. 2011. Environmental laws and sustainability: an introduction. Sustainability. 3:531–540. doi:10.3390/su3030531

- Dyurgerov MB, Meier MF. 2005. Glaciers and the Changing Earth System: A 2004 Snapshot. Boulder: Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado.

- Eriksson M, Jianchu X, Shrestha AB, Vaidya RA, Nepal S, Sandström K. 2009. The changing Himalayas: impact of climate change on water resources and livelihoods in the Greater Himalayas. Kathmandu: International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development Publication; p. 1–23.

- Fisher B, Turner RK, Morling P. 2009. Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecol Econ. 68:643–653. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.09.014

- Gadgil M, Iyer P. 1989. On the diversification of common property resource use by the Indian society. In: Berkes F, editor. Common property resources: ecology and community based sustainable development. London: Belhaven Press; p. 240–255.

- Gautam MR, Timilsina GR, Acharya K. 2013. Climate Change in the Himalayas: Current State of Knowledge. Policy research working papers. The World Bank Development Research Group Environment and Energy Team. WPS6516.

- Goldman RL, Thompson BH, Daily GC. 2007. Institutional incentives for managing the landscape: inducing cooperation for the production of ecosystem services. Ecol Econ. 64:333–343. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.01.012

- Goulder LH, Parry IWH. 2008. Instrument choice in environmental policy. Rev Environ Econ Policy. 2:152–174. doi:10.1093/reep/ren005

- Government of India. 2008. National Action Plan on Climate Change. Prime Minister’s Council on Climate Change. Available from: http://www.moef.nic.in/downloads/home/Pg01-52pdf

- Government of India. 2010. National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem under National Action Plan on Climate Change. Available from: http://dst.gov.in/scientific-programme/NMSHE_June_2010. pdf

- Gunningham N, Sinclair D. 1999. Integrative regulation: a principle‐based approach to environmental policy. Law & Soc Inquiry. 24:853–896. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.1999.tb00407.x

- Gunningham N, Young MD. 1997. Toward optimal environmental policy: the case of biodiversity conservation. Ecol Law Q. 24:243–298.

- Hertin J, Jordan A, Turnpenny J, Nilsson M, Russel D, Björn N. 2007. Rationalising the policy mess? Ex ante policy assessment and the utilisation of knowledge in the policy process. Berlin: Freie Universitat Berlin.

- Hoermann B, Banerjee S, Kollmair M. 2010. Labour migration for development in the Western Hindu Kush–Himalayas: understanding a livelihood strategy in the context of socioeconomic and environmental change. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

- INCCA (Indian Network for Climate Change Assessment). 2010. Climate Change and India: A 4x4 Assessment. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. Available from: http://www.moef.nic.in/downloads/public-information/fin-rpt-incca.pdf.

- Liu X, Chen B. 2000. Climatic warming in the Tibetan plateau during recent decades. Int J Climatol. 20:1729–1742. doi:10.1002/1097-0088(20001130)20:14<1729::AID-JOC556>3.0.CO;2-Y

- Manning AD, Fischer J, Lindenmayer D. 2006. Scattered trees are keystone structures – implications for conservation. Biol Conserv. 132:311–321. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.04.023

- MEA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment). 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: the Assessment Series (four volumes and summary). Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Ostrom E, Burger J, Field CB, Norgaard RB, Policansky D. 1999. Revisiting the commons: local lessons, global challenges. Science. 284:278–282. doi:10.1126/science.284.5412.278

- Pagiola S, von Ritter K, Bishop J. 2004. Assessing the economic value of ecosystem conservation. Environment Department Paper. 101. Washington (DC): The World Bank Environment Department.

- PCAST (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology). 2011. Report to the President- sustaining environmental capital: protecting society and the economy. Report to the President. Washington (DC): Biodiversity Preservation and Ecosystem Sustainability Working Group.

- Pejchar L, Morgan P, Caldwell M, Palmer C, Daily GC. 2007. Evaluating the potential for conservation development: biophysical, economic, and institutional perspectives. Conserv Biol. 21:69–78. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00572.x

- Pretty JN, Pimbert MP. 1995. Beyond conservation ideology and the wilderness. Nat Resour Forum. 19:5–14. doi:10.1111/j.1477-8947.1995.tb00588.x

- Ramanathan U. 2002. Common land and common property resources. In: Jha PK, Ed. Land Reforms in India, Volume 7, Issues of Equity in Rural Madhya Pradesh. New Delhi: Sage.

- Ring I, Schröter-Schlaack C, Barton DN, Santos R, May P. 2011. Recommendations for assessing instruments in policy mixes for biodiversity and ecosystem governance. In: David N, Barton K, Margrethe KT, Irene R, editors. POLICYMIX technical brief [Internet]. vol. 5, p. 1–24. [cited 2014 Jan 15]. Available from: http://policymix.nina.no

- Ring I, Schroter-Schlaak C 2011. Justifying and assessing policy mixes for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem service provision. Paper presented at the special session on ‘Instrument Mixes for Biodiversity Policies’. ESEE 2011, Istanbul.

- Saxena KG, Rao KS, Sen KK, Maikhuri RK, Semwal RL. 2001. Integrated natural resource management: approaches and lessons from the Himalaya. Conserv Ecol. 5:14.

- Seccombe-Hett T. 2000. Market-based instruments: if they’re so good, why aren’t they the norm? World Economics. J Curr Econ Anal Policy. 1:101–126.

- Semwal RL, Nautiyal S, Rao KS, Maikhuri RK, Bhandari BS. 1999. Structure of forests under community conservation: a preliminary study of Jardhar village initiative in Garhwal Himalaya. ENVIS Bull- Himalayan Ecol Dev. 7:16–27.

- Seppelt R, Dormann CF, Eppink FV, Lautenbach S, Schmidt S. 2011. A quantitative review of ecosystem service studies: approaches, shortcomings and the road ahead. J Appl Ecol. 48:630–636. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01952.x

- Singh SP. 2002. Balancing the approaches of environmental conservation by considering ecosystem services as well as biodiversity. Curr Sci. 82:1331–1335.

- Singh SP, Bassignana-Khadka I, Karky BS, Sharma E. 2011. Climate change in the Hindu Kush-Himalayas: the state of current knowledge. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development. Kathmandu: Hill Side Press; 102 p.

- Smith T. 2014. Climate vulnerability in Asia’s high mountains: how climate change affects communities and ecosystems in Asia’s water towers. Washington (DC): World Wildlife Fund; p. 1–104.

- TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity). 2010. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity for Local and Regional Policy Makers. Available from: ISBN 978-3-9812410-2-7. http://www. teebweb. org/wpcontent/uploads/StudyReport/TEEB.

- Theobald DM, Spies T, Kline J, Maxwell B, Hobbs NT, Dale VH. 2005. Ecological support for rural land-use planning. Ecol Appl. 15:1906–1914. doi:10.1890/03-5331

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2012. Atlas of health and climate. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Wulf H, Bookhagen B, Scherler D. 2012. Climatic and geologic controls on suspended sediment flux in the Sutlej River Valley, western Himalaya. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 16:2193–2217.