ABSTRACT

A growing number of nations aim to design coastal plans to reduce conflicts in space and safeguard ecosystems that provide important benefits to people and economies. Critics of coastal and ocean planning point to a complicated process with many actors, objectives, and uncertain outcomes. This paper explores one such decision-making process in Belize, which combines ecosystem service modeling, stakeholder participation, and spatial planning to design the country’s first integrated coastal zone management plan, officially approved by the government in August 2016. We assessed risk to three coastal-marine habitats posed by eight human uses and quantified current and future delivery of three ecosystem services: protection from storms, catch and revenue from lobster fishing, and tourism expenditures to identify a preferred zoning scheme. We found that a highly adaptive team of planners, scientists, and analysts can overcome common planning obstacles, including a dearth of data describing the health of the coastal zone and the many uses it supports, complicated legal and political landscapes, and limited in-country technical capacity. Our work in Belize serves as an example for how to use science about the ways in which nature benefits people to effectively and transparently inform coastal and ocean planning decisions around the world.

EDITED BY Joao Rodrigues

Introduction

As 75 million people are born each year and similar numbers seek to raise their standard of living (Population Reference Bureau Citation2013), the Earth’s coastal and marine ecosystems face expanding pressure from fisheries, aquaculture, energy production, land-based pollution, shipping, recreation, other development activities, and climate change (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Citation2005; Halpern et al. Citation2008; Worm et al. Citation2009). The growing intensity and diversity of uses co-occurring in coastal zones have also led to conflicts among sectors competing for limited space. The cumulative impacts of these stressors increase risk of habitat degradation (Hobday et al. Citation2011; Williams et al. Citation2011; Samhouri and Levin Citation2012; Arkema et al. Citation2014), often leading to the loss of benefits that natural systems provide to people and species. Different terms, including coastal and ocean planning, marine spatial planning, coastal zone management, and land-sea planning, are often used synonymously in the gray and peer-reviewed literature. For the ease of communication, we use the term coastal and ocean planning to describe how human and natural systems at the land-sea interface can be managed for multiple uses and across sectors to sustain the productivity of the coastal zone (Ruckelshaus et al. Citation2008; Halpern et al. Citation2012; White et al. Citation2012) and meet the needs of present and future generations (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity Citation2004; UN General Assembly Citation2010; European Commission Citation2011). Several proposed frameworks can be used to guide coastal and ocean planning (Arkema et al. Citation2006; Leslie and McLeod Citation2007; Day Citation2008; Beck et al. Citation2009; Ehler and Douvere Citation2009; Kittinger et al. Citation2014), many of which suggest incorporating ecosystem services and integrated risk to species and habitats as elements of decision-making (Koehn et al. Citation2013; Arkema et al. Citation2014).

Tools for embedding ecosystem services into stakeholder-driven planning processes

Recent technological advances have made it possible for planners and researchers to couple stakeholder knowledge with science-based methods (Douvere Citation2008; Ehler Citation2008; Beck et al. Citation2009) that quantify the myriad risks to ecosystems and the benefits they afford to people now and in the future (TEEB Citation2010; Guerry et al. Citation2012, Citation2015; Ruckelshaus et al. Citation2015). Stakeholder involvement is deemed to be a necessary ingredient for successful outcomes in coastal and ocean planning (Leslie and McLeod Citation2007; Lynam et al. Citation2007), since it creates the conditions for salient information about how ecosystem services are used and valued to be collected and integrated into planning considerations, increasing stakeholder support for the resulting plans. Flexible decision-support tools that encourage early participation by stakeholders (Cárcamo et al. Citation2014) may enhance the quality of decisions by incorporating more transparent, comprehensive information sources (Reed Citation2008), increase the perception that the decisions are legitimate (Cash et al. Citation2003; UNEP and IOC-UNESCO Citation2009), and strengthen stakeholder knowledge (Gissi and de Vivero Citation2016) and social capital (Chess and Purcell Citation1999; Blackstock et al. Citation2012). Stakeholder visions and values (Rosenthal et al. Citation2015; Ruckelshaus et al. Citation2015) can support planning and policy (Douvere and Ehler Citation2009; Domínguez-Tejo et al. Citation2016) by elaborating how alternative management decisions today could affect ecosystems and the benefits they provide to people in the future.

The need for an integrated management plan in Belize

Governments seek to improve ecological, economic, and social outcomes for their citizens but often struggle to deliver these in an effective and transparent manner, especially when it comes to coastal- and marine-related sectors (Day et al. Citation2008; Agostini et al. Citation2010; Guerry et al. Citation2012; White et al. Citation2012; Arkema and Ruckelshaus Citation2017). Demand is growing for examples of places that have engaged in coastal and ocean planning and how managers have used practical approaches and tools to balance development with the need to protect the environment. The Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System (BBRRS) was added in 2009 to UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger and to date remains on this list based on threats related to the removal of mangrove cover, unsustainable coastal development, and offshore oil exploration. With the coastal nation of Belize at a crossroads, a recent government-led planning process offers a real-world example and relevant lessons to other countries engaging in coastal and ocean planning around the world.

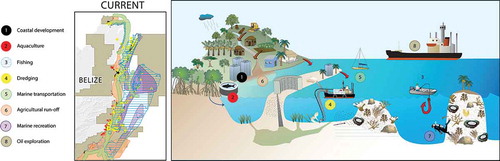

Belize is home to the largest unbroken section of the Mesoamerican Reef system, extensive seagrass meadows, and all four species of mangroves native to the Caribbean (Neal et al. Citation2008). These ecosystems support a diversity of marine species, including the endangered West Indian manatee and green, hawksbill, and loggerhead sea turtles. Coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrasses also are critical to the economy and people of Belize. A 2009 study estimated the value of Belize’s coral reefs and mangroves at between $395 and 559 million USD per year (Cooper et al. Citation2009) and more than 60% of the population depends directly or indirectly on the goods and services provided by coastal and marine ecosystems (Statistical Institute of Belize Citation2010; WWF Citation2016). Tourism, fisheries, real estate, and agricultural industries underlie the economic health of the country; however, they paradoxically threaten the ecosystems that make these activities possible (Rosenthal et al. Citation2012; ).

Figure 1. Many coastal and marine uses co-occur in Belize’s coastal zone. Map depicts distribution of uses under the current management scenario (year 2010). Graphic courtesy of the Healthy Reefs Initiative.

To address these conflicts, the Government of Belize passed the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1998, which recognized the need for multi-sectoral planning to sustain habitats and their contributions to Belizeans’ well-being. The Act called for an integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) plan that would be national in scope while incorporating political, ecological, social, and technological drivers at subnational scales (Coastal Zone Management Act, Revised Edition Citation2003). The Act designated the Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute (CZMAI) to address issues of rapid development, overfishing, population growth, and environmental problems in the coastal zone and tasked it with designing an integrated management plan. The overall goal of the plan was to maintain ecosystem integrity while ‘ensuring the delivery of ecosystem service benefits for present and future generations of Belizeans and the global community’ (CZMAI Citation2016, p. 4).

One of the biggest obstacles to creating a robust, science-based plan that would safeguard Belize’s natural assets was a dearth of tools and limited synthesis of existing data. Another challenge was a transparent approach to identify shared objectives and methods to assess alternative management actions and recommendations. National and local agencies in Belize struggled to manage conflicting interests and mandates and to make defensible, enduring decisions in managing coastal resources. Limited progress was made toward a national plan until 2010, when a collaboration formed between CZMAI and Natural Capital Project (NatCap). CZMAI led the policy design and stakeholder engagement and NatCap developed and tested new technical methods and tools. Together, our team codeveloped ecosystem service information within a stakeholder engagement process to inform the design of Belize’s first ICZM plan.

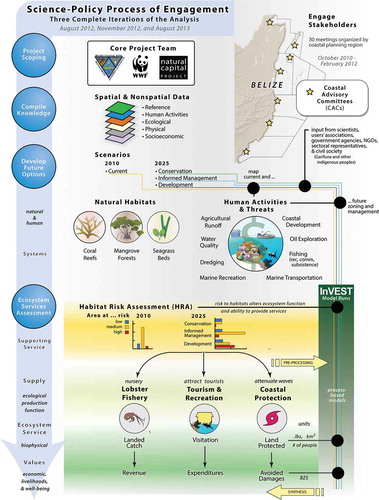

In this article, we offer a roadmap for leveraging ecosystem services information to help managers and stakeholders identify risks and measure how different decisions can meet coastal and ocean planning objectives based on lessons learned during a 6-year engagement. Building on the framework proposed by Rosenthal et al. (Citation2015), we describe four key steps in the science-policy process applied in coastal Belize: (1) project scoping and stakeholder engagement, (2) compiling knowledge to quantify ecosystem services and map coastal and marine ecosystems and human activities, (3) developing future zoning and management options, and (4) conducting an ecosystem service assessment: learning through iteration. These four steps were conducted iteratively, with a final result culminating in a coastal zone management plan approved by the Belizean government in 2016. Through repeated stakeholder engagement and valuation of fisheries, coastal protection, and tourism benefits, we identified data gaps, advanced our models, validated early findings, and improved science-based management recommendations over time. Here, we present the techniques used to synthesize and communicate change in the value of ecosystem services to stakeholders and policy-makers and discuss approaches used to convey the ability of alternative management options to meet planning objectives. We conclude by drawing out lessons from our experience in Belize that can inform other coastal and ocean planning processes.

Methods

We designed an integrated management plan for Belize through an iterative process that elicited input from local stakeholders and experts, employed the best available science, involving codevelopment of methods and metrics among scientists and decision-makers, and produced tools for planners to use in ongoing adaptive management. Using an ecosystem services framework (Rosenthal et al. Citation2015; Ruckelshaus et al. Citation2015), we evaluated changes in the benefits flowing from three natural habitats (coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass meadows) to people under alternative options for management (Arkema et al. Citation2015), referred to hereafter as scenarios. The scenarios for management of the coastal zone were elicited and refined through stakeholder engagement and modeling of ecosystem services. We leveraged several essential elements for a successful planning process, including an authoritative coastal zone management body (CZMAI), expertise in natural and social sciences (NatCap), and the necessary relationships to connect policy priorities to science. The following subsections describe the four key steps in the planning process.

Project scoping and stakeholder engagement

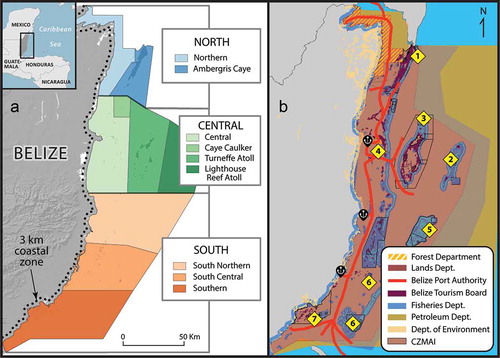

To articulate a strategy for the overall planning process, CZMAI first reached out to local leaders, university and NGO scientists, and government agencies through in-person meetings, interviews, and an online survey. Initial feedback suggested the need for a proactive and adaptive planning approach to address national marine and coastal issues within a specified timeframe, and to enable monitoring and evaluation. To this end, CZMAI outlined four objectives for the ICZM Plan: (1) encourage sustainable resource use, (2) support integrated development planning, (3) build alliances to benefit Belizeans, and (4) adapt to climate change (CZMAI Citation2016). This set the stage for a larger, more extensive public engagement and knowledge-building process to support CZMAI’s mandate of managing multiple uses across jurisdictions (), reducing user conflicts, and safeguarding ocean and coastal benefits.

Figure 2. (a) ICZM region including a 3-km inland boundary (dotted line) and territorial waters. CZMAI divides the coastal zone into nine planning regions based on geographical, biological, administrative, and economic similarities; (b) jurisdictional boundaries and co-management agreements across government agencies, mandates, and NGOs including (1) Blue Ventures, (2) Belize Audubon Society, (3) Turneffe Atoll Sustainability Association, (4) Friends of Swallow Caye, (5) Wildlife Conservation Society, (6) Southern Environmental Association, and (7) Toledo Institute for Development and Environment (TIDE).

During initial consultations, two key questions were asked: (1) which sectors and human uses in the coastal zone require improved management and (2) where should these sectors and uses be located in the future? Participants listed a variety of activities and described the relationship between these activities and coastal and marine ecosystems, including potential risks posed to their livelihoods and safety. Through these discussions, CZMAI and NatCap identified three priority benefits that coastal and marine ecosystems in Belize provide to people: catch and revenue from fisheries, visitors and expenditures from tourism, and protection from storms. We used the stakeholders’ responses and our own knowledge of key activities to identify eight human uses. We then mapped these uses under the current management conditions and several alternative scenarios for the future management of the coastal zone (see the ‘Compiling knowledge to quantify ecosystem services and map coastal and marine ecosystems and human activities’ and ‘Developing future zoning and management options’ sections).

CZMAI convened stakeholders in a variety of ways and multiple times. Throughout the process, stakeholders contributed data, codeveloped scenarios, and reviewed and refined the scientific products that were incorporated into the ICZM Plan. Coastal Advisory Committees (CACs) or similar stakeholder engagement fora, formed in each of the nine coastal planning regions (), included representatives from government, local and national NGOs, sectors that use the coastal and marine zones (such as producers’ or users’ associations for agriculture, tourism and fishing), academia, and civil society (such as indigenous peoples). In particular, CACs helped to create storylines for future management scenarios and corresponding maps depicting the possible spatial extent and intensity of future activities. From October 2010 to February 2012, CZMAI organized 30 CAC and public meetings with over 200 people across Belize’s nine coastal planning regions. During these consultations, CZMAI facilitated discussions about local uses of the coastal zone, documented recommendations for future uses, presented the science and tools underlying the ecosystem service analysis, and sought feedback on modeled results.

To illustrate the power of an ecosystem services approach, we digitized recommendations from participants, ran models, and created maps highlighting where three ecosystem services changed under different scenarios and how this could lead to trade-offs among benefits flowing to different groups of stakeholders. Communication through maps was an avenue through which CZMAI could relay how mangroves forests, for example, were at risk of degradation from coastal development. Because mangroves support spiny lobster populations, which in turn support fishers, the health of mangroves was important to the Belize Fisheries Department, a key entity whose support would be important for the ICZM Plan. Fisheries Department staff saw value in ecosystem services information (e.g., linking the health of mangroves to lobster fisheries) to explain to stakeholders and decision-makers that key habitats support the export value of spiny lobster, a critical part of the Belizean economy. Fisheries staff in turn shared additional data on the lobster fishery with CZMAI to incorporate in further iterations of the ecosystem service analysis. This transparent, iterative process strengthened our collaboration with fisheries staff, elicited valuable feedback that improved the rigor of the analysis, and generated buy-in for the planning process.

Compiling knowledge to quantify ecosystem services and map coastal and marine ecosystems and human activities

We designed a knowledge acquisition and management strategy to consider first how data would be used during the process (Halpern et al. Citation2012; Rosenthal et al. Citation2015) and what information would be needed to address the planning objectives in a way that would resonate with stakeholders. Research suggests that a data collection strategy helps anticipate data needs, designs plausible alternative scenarios, identifies gaps and options for ecosystem service analysis, and develops a program for monitoring and evaluation of results (Hockings Citation2003; Boyd and Banzhaf Citation2007; McKenzie et al. Citation2014). Of particular importance to our process was gaining an understanding of which metrics for ecosystem services would be of interest to stakeholders and government planners (Day Citation2008; Cornu et al. Citation2014). By metrics, we mean the biophysical, socioeconomic, and cultural units necessary to quantify current and future ecosystem services. Early outputs from our predictive models based on coarse, globally available datasets served as a foundation for discussions with stakeholders and managers about which metrics would be meaningful to them. We could then collect the necessary data to both model these services and quantify them in specific ways, including the amount of risk posed by different activities to critical habitats, fisheries catch (lbs) and revenue ($), visitation (number of people) and expenditures ($) by tourists, and land protection (m2) and avoided damages ($) from storm-induced flooding and erosion.

Another category of data and knowledge compilation was the mapping of human activities and natural features, which we did in close collaboration with various government agencies and NGOs. Our initial inventory of data revealed dispersed information sources. No one agency or organization maintained a central data repository characterizing the coastal zone. Thus, we compiled information from databases collected and housed by ministries and departments in the Belizean government and through regional efforts to monitor seagrasses and mangroves (i.e., Wabnitz et al. Citation2008; Cherrington et al. Citation2010). We also extracted and digitized relevant information from planning documents and policies, often meeting directly with local experts and stakeholders to understand how and where they use and interact with coastal resources, including reefs and culturally important areas. shows examples of the types of information collected, such as the elevation and shape of the coastline, the distribution of coastal and marine habitats, expenditures by tourists, the value of coastal assets, and maps of human activities (e.g., traditional fishing grounds, dredging of sediment for shipping channels or aquaculture).

Table 1. Types of data and knowledge used by scientists and managers to quantify ecosystem services and to inform the 2016 Belize ICZM Plan.

After information was acquired, we faced additional data management challenges, including the need to process and combine incongruences in surveys across acquisition dates, spatial resolution, and mapping units. To keep spatial representations of each human activity distinct and avoid common pitfalls associated with mismatches in scale of data, we mapped coastal and ocean uses at the scale used for national and regional zoning. We compiled the individual activities described by stakeholders during the scoping phase into categories they identified. CZMAI mapped coastal and marine activities as eight general use zoning categories: coastal development, marine transportation, dredging, fishing, marine recreation, oil exploration, aquaculture, and agricultural runoff (CZMAI Citation2016). These zoning categories (or ‘zones’) established a clear starting point for different sectors to communicate how and where compatible uses could co-occur in the future. For example, the marine transportation zone mapped pathways of both water taxis and cruise ships but did not differentiate the two activities.

CZMAI’s role as lead coastal resource manager enabled our team to forge relationships with information officers from both the public and private sectors. When gathering information and filling knowledge gaps, we were strategic in deciding who would make the request and how to describe our intended use of the data. We thought carefully about how ICZM could help individual departments meet their objectives and this enabled our team to shape the ICZM Plan to be consistent with missions of different agencies and NGOs. We made every effort to include providers of data in future consultations – giving them the opportunity to see how their data, knowledge, and expertise were incorporated into the planning process, and to correct errors or misuse of data. For example, CZMAI invited the Belize Fisheries Department to a demonstration of an early version of the spiny lobster fishery model built around their survey data (Little and Watson Citation2005; De Leon González et al. Citation2008) to provide feedback and inform the model development process.

Developing future zoning and management options

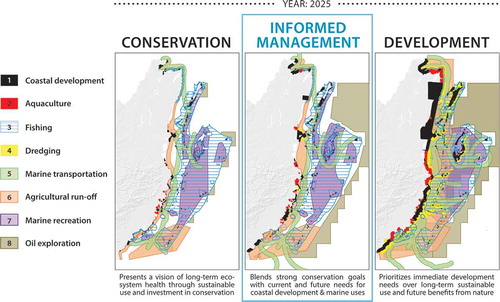

Stakeholders from each planning region had different opinions about future uses of Belize’s coastal zone, underscoring the complex challenges faced by government agencies, resource managers, and policy-makers in evaluating trade-offs between specific investment opportunities and their environmental or economic impacts (Reed et al. Citation2009; Maguire et al. Citation2012). CZMAI staff organized stakeholder consultations to elicit storylines describing alternative values and visions of the future. Together the team created three distinct cross-sectoral scenarios based on existing and alternative development proposals and stakeholder preferences. Scenario analyses were used to frame the management options under consideration, guide the spatial planning process so that it met the planning objectives (sustained future economy, access to traditional fisheries, and security from coastal hazards), and to design well-defined interventions for addressing management objectives in the face of future climate (Henrichs et al. Citation2010).

As a first step, we used stakeholder input and management objectives to design two extreme scenarios to bookend the range of future planning options. The Conservation future prioritized a vision of long-term environmental health through conservation of existing ecosystems. The Development scenario storyline presented a vision of rapid economic growth based on natural resource utilization and urban expansion. It prioritized immediate development needs and the interests of coastal developers and extractive industries over the proactive preservation of ecosystem services. As the process progressed, this scenario came to represent a plausible future for the coastal zone where construction and development occurred without zoning guidelines. We also designed a third, Middle-of-the-road, scenario that merged elements of the Conservation and Development scenarios.

The three future scenarios varied by the configuration and intensity of human use, which helped isolate key drivers of change affecting the ecosystem services of interest to stakeholders and policy-makers. The team started this process by coarsely mapping descriptions of plausible futures, considering the current distribution of human activities, existing and pending government plans, and stakeholders’ values and preferences. We refined maps of alternative futures by adjusting assumptions about how human uses would be managed – and their effects on coastal ecosystems – under the alternative scenarios, based on input from stakeholders, scientists, and further modeling. At smaller scales, we included details such as where marinas could be built or which areas needed industry or tourism development. The resulting spatial representations of human use () described possible action plans that included a diversity of perspectives about how the future should look and where decisions made now could impact the flow of coastal and marine benefits to people in the future.

Figure 3. Zones of human use for three alternative future management scenarios in the year 2025. Scenario storylines are based on a 15-year vision of the future using 2010 state-of-play as the baseline. As described in Arkema et al. (Citation2015), the final iteration of the Informed Management scenario was ultimately chosen as the preferred scenario for the integrated coastal zone management plan (CZMAI Citation2016).

Conducting an ecosystem service assessment: learning through iteration

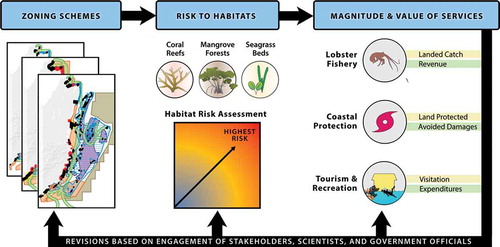

We built and tested several ecosystem service models (Arkema et al. Citation2015) to predict how changes in coral, seagrass, and mangrove habitats – and different scenarios of management of those habitats identified by stakeholders – would lead to changes in the amounts of protection from storms, lobster harvest, and tourism revenues. Spatial estimates of value were computed with models from the Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) software (Sharp et al. Citation2016). First, risk to key habitats posed by the eight human activities was mapped and measured with the InVEST habitat risk assessment (HRA) model (Arkema et al. Citation2014; ). The InVEST HRA model draws on an ecological risk assessment approach to identify risk to natural habitats by accounting for locations of specific activities. Maps and summary tables identified where cumulative risk from multiple stressors is greatest now and in the future, and which specific human activities contribute to this risk.

Figure 4. Conceptual model of the stakeholder-driven process undertaken by CZMAI and NatCap to co-develop methods, tools, and results. Risk to habitats posed by the intensity and distribution of human activities described in zoning scenarios can alter ecosystem function and its ability to provide services (habitat risk assessment). InVEST models were applied in Belize to map and measure this risk and then to map and value three ecosystem services in biophysical and economic units.

Next, risk maps produced by HRA served as ecosystem inputs for three InVEST ecosystem service models: (1) fisheries production, using habitat distribution, life-history information, and survival parameters to estimate the volume of spiny lobster harvest (Arkema et al. Citation2015), (2) coastal protection, to quantify the protective services provided by nearshore habitats in terms of avoided erosion and flood mitigation (Guannel et al. Citation2015, Citation2016), and (3) tourism, to predict spatial shifts in visitors and visitor related expenditure based on the locations of natural habitats and other features that factor into people’s decisions about where to recreate (Wood et al. Citation2013). We produced spatially explicit values for ecosystem services in both biophysical and economic units to communicate how management decisions made today would influence changes to key benefits in the future.

To improve the legitimacy and accuracy of our understanding of how management recommendations affect key ecosystem services in Belize, we repeatedly revisited each step in the entire science-policy process as part of three distinct iterations (August 2012, November 2012, and August 2013; ). Because each iteration required significant time and partner engagement, our team was able to complete only three iterations over the lifetime of the project. Our initial ecosystem service analyses revealed that the Middle-of-the-road scenario would result in nearly as much risk of degraded habitats and associated services as the Development scenario. Inherent in CZMAI’s design of the process was repeated refinement of the Middle-of-the-road scenario by relocating human activities to safeguard ecosystems and support sustainable development of coastal resources based on the results of our scientific models (see below and Arkema et al. Citation2015). This middle option drew out commonalities between two distinct stakeholder perspectives, highlighted the drawbacks of certain Conservation and Development alternatives, and gained support because it integrated stakeholder feedback. The revised Middle-of-the-road scenario came to be known as the Informed Management scenario, and by the end of the process, this spatial arrangement of human activities was substantially different from what it initially started as. By treating the Informed Management scenario as a dynamic view of potential future activities shaped by stakeholder reactions to each iteration of the management scenarios and corresponding ecosystem service results, our team was able to begin building consensus around a shared future vision.

Figure 5. Ecosystem services provide useful metrics for coastal and ocean planning. Our science-policy process of engagement contains explicit hypotheses about (1) human activities and earth processes, (2) ecosystem processes, condition, and distribution, and (3) benefits flowing to people from ecosystems.

The first complete draft of the Belize ICZM Plan underwent a 30-day public review from 16 May to 12 June 2013. This mandated review period provided the project team with avenues through which to collect feedback and to incorporate improvements into a final iteration of the zoning scheme and ecosystem service analyses, completed in August 2013. CZMAI reached out directly to stakeholders through regional CACs, television and radio ads, announcements in print news and media, convened public meetings in coastal regions, and shared educational materials related to the process. NatCap compiled feedback from two online surveys (n = 200), administered during the initial scoping period and after the first round of scenarios was developed, to determine the level of satisfaction with participation in the planning process. Additionally, CZMAI and NatCap staff conducted 14 key informant interviews to gather more in-depth feedback on the science-policy process and stakeholder engagement. The coastal planning and ecosystem services teams () based in Belize and the United States continued refining the scenarios, data, and scientific models. To improve the zoning in the scenario selected for the management plan, our team identified regions where the InVEST models indicated that ecosystem service delivery would decrease relative to the present scenario and made small adjustments in the location and extent of zones to improve ecosystem service delivery for a final national zoning scheme, which stakeholders reviewed.

Table 2. Roles and responsibilities of the core project team, collaborators, stakeholders and government officials and their specific contribution to the scoping phase, stakeholder engagement, design and eventual implementation of Belize’s first ICZM Plan.

Results

Our analysis of ecosystem services revealed differences in benefits across scenarios, driven in part by the variation in risk posed by human activities to sensitive habitats. For instance, in planning regions where large areas of habitat experienced significant impacts due to the combined effects of multiple uses, model results suggested declines in lobster catch and revenue and greater exposure of coastal populations to hazards. The coastal protection provided to Belizean people and infrastructure varied among future zoning scenarios and planning regions due to differences in the functional habitat available for reducing exposure and risk during storm events. The results were also influenced by differences in socioeconomic factors among scenarios, especially for tourism and coastal protection benefits. Returns from these two services were highest under an Informed Management scenario due to changes in the coastal development layer, extent of higher value property, and amount of infrastructure to support tourism (Arkema et al. Citation2015).

Numerical and mapped outputs from the ecosystem service models, combined with comparative graphs and summary tables, illustrated clear differences across planning regions and alternative future plans in the amount of land protected and property damage that was avoided due to the presence of mangrove forests, coral reefs, and seagrass meadows (in Arkema et al. Citation2015, Figure 2; Appendix). Ministry representatives expressed a preference for communicating the value of coastal protection services by showing how the coastline would change as a result of more intense storm events and rising seas under different scenarios. Our subsequent visuals were able to demonstrate how mangrove, coral reef, and seagrass ecosystems, together with other habitats in the seascape, provide important co-benefits, helping the coastal zone recover during non-storm events and ensuring the long-term viability of the system (Guannel et al. Citation2016).

Based on findings from surveys and interviews conducted during the planning process, we learned that repeated engagement made stakeholders feel more committed to the process and optimistic about the potential for positive outcomes. We heard that the technical elements of our approach (e.g., use of maps and quantitative data, incorporation of stakeholder ideas and values into the assessment) were some of the main reasons stakeholders were continuing to participate in the process. However, feedback also suggested that our team could improve communication about data inputs, clarify how and why quantitative models were being used, and translate the jargon of ecosystem services into layman’s terms. Finally, we were able to infer the importance of good facilitation during CAC consultations to resolve conflicts and retain stakeholder involvement in the process.

Synthesizing and communicating information

CAC members helped the team develop and present compelling narratives and clear conclusions based on their understanding of which information about nature’s benefits would resonate with policy-makers and stakeholders. It was notable to local leaders, for example, that under the Informed Management scenario, spiny lobster catch was predicted to increase by more than 25% nationally, compared to current returns. Also of note, tourism expenditures by visitors to the Northern planning region for the Informed Management scenario were double that of a Development future (see Appendix). Feedback from participants of the planning process helped us continually adapt our approach to synthesizing results. We were able to break through common obstacles to effective engagement by conveying stories and actionable recommendations that offered stakeholders something to react to, created opportunities for additional dialogue, and, most importantly, ensured transparency in the process.

Three ways of visualizing results – by location, by amount, and by service – were found to be relevant and comprehensible to stakeholders because it allowed them to identify synergies (‘win–wins’) and trade-offs among human uses and ecosystem benefits at both the national and planning region scale. The visuals embedded in the Plan (CZMAI Citation2016) built on previous techniques for communicating ecosystem services information and illustrating how alternative scenarios affect monetary and non-monetary outcomes (Raudsepp-Hearne et al. Citation2010; Guerry et al. Citation2012; White et al. Citation2012; Bateman et al. Citation2013; Waite et al. Citation2014). As an example, coastal protection and tourism were a win–win under the preferred Informed Management scenario in the three southern planning regions. The trade-off was that ecosystem risk was greater and fisheries revenue lower for that scenario relative to the Conservation scenario in those regions. However, fisheries revenue increased and risk to habitats decreased in the Informed Management scenario relative to the current situation. By assessing spatial variation in services and their values and then converting standard model outputs into relevant metrics, we produced a suite of visualizations that ultimately made sense to participants in the planning process.

Outreach for the ICZM plan

A variety of outreach tools were deployed to inform the public and private sectors about the ICZM planning process and how alternative decisions can have better or worse outcomes for both people and nature. A social simulation, called ‘Tradeoff! Best Coast Belize’, at a November 2012 workshop highlighted three important ocean objectives expressed by Belizeans: coastal protection, tourism, and fisheries. The game board displayed colorful maps and included a point system to help government officials, sector representatives, scientists, and students understand the types of data, tools, assumptions, and considerations that go into ecosystem service approaches for decision-making, and how human choices can influence change (Verutes and Rosenthal Citation2014). Belize’s National Emergency Management Organization also used maps and graphs from the Plan to support their disaster risk reduction plans, specifically to illustrate where changes in coastal protection services would lead to more at-risk populations and infrastructure, including coastal access points, schools, and emergency services. An online map viewer, available through CZMAI’s website in early 2013, enabled both public and private interests to interact with multimedia displays of scenario storylines and emerging analytical results (Natural Capital Project Citation2013). These outreach tools and products offered a more accessible, dynamic content stream and helped readers to understand potential implications of the draft Plan.

The ICZM plan approval process

The review, endorsement, and ultimate approval of the Belize ICZM Plan by the CZM Advisory Council, CZMAI Board, Cabinet, and Parliament was central to the science-policy process and required new syntheses and communications. Repeated engagement of key stakeholders over several months in mid-2015 enabled the CZMAI to inform and educate them about the Plan’s content and implications. This secured buy-in for the Plan and created momentum for its final approval. The steps taken to move the Plan through the legally required processes and formal channels for approval in accordance with the Coastal Zone Management Act are listed in .

Table 3. Key activities and timelines toward approval of the Belize ICZMP from 2015 to 2016.

In October 2015, with only one step remaining in the Plan’s approval process (submission of a formal request to the Cabinet for Plan approval and endorsement), Belize’s Prime Minister called elections for early November 2015. This resulted in the immediate dissolution of the Cabinet and postponement of the Plan’s approval until a new Government of Belize Administration assumed office. The elections also had implications for the CZMAI Board, which was dissolved and subsequently reappointed under a newly realigned Ministry (Agriculture, Fisheries, Forestry, the Environment, and Sustainable Development). It was essential at this stage in the process to demonstrate how the draft Plan reflected master plans, national development strategies, and planning frameworks. Subsequent to the November elections, CZMAI reached out to its new Minister in order to cultivate support for the Plan once again and conduct a second public review period in late 2015, following the appointment of a new Board of Directors for the Ministry. Feedback collected during this final stage of review informed the design of outreach products and events, including a Coastal Awareness Week in March 2016 to coincide with the official launch of the Plan.

Discussion

After 20 years of relationship building, scientific advances, and local-capacity strengthening, Belize’s Cabinet endorsed the ICZM Plan on 22 February 2016 (CZMAI Citation2016) and its Parliament officially approved it by affirmative resolution on 28 August 2016. This spatial plan, described as visionary by UNESCO (Citation2016), considers the needs of multiple sectors and stakeholders, advances the management of coastal and marine ecosystems, and explicitly accounts for nature’s benefits to people. Building on coastal and ocean planning approaches around the globe, we codeveloped an approach to incorporate stakeholder visions and values – through changes in ecosystem services and risk to habitats – into an integrated management plan for the coastal nation of Belize. By sharing results at key decision points, obtaining feedback, and revising the scientific methods, we were able to refine and improve our approach, while also maintaining the technical rigor, and ensuring local visions and values informed the process. This stakeholder-driven process involved the coproduction of new data and tools to map the present condition of Belize’s marine ecosystems and design alternative zoning configurations that considered existing legal mandates, jurisdictional boundaries, policies, strategies, and region-specific management guidelines.

Next steps: implementation and action plan

The Belize ICZM Plan is a framework for national action 'to facilitate improved management of coastal and marine ecosystems so as to maintain their integrity while ensuring the delivery of ecosystem benefits for present and future generations of Belizeans and the global community' (CZMAI Citation2016, p. 4). Given the political complexities and financial realities facing the CZMAI and other agencies tasked with managing Belize’s coastal zone, an implementation and action plan is necessary to guide their efforts in translating the strategic steps outlined in the ICZM Plan into concrete action and coordinate state and non-state actors around future actions required, including comprehensive tracking, monitoring, and evaluation of progress. Implementation and monitoring began in 2016. A recent loan from the Inter-American Development Bank to the Ministry of Tourism for implementing Belize’s Sustainable Tourism Plan is a promising advance (Arkema and Ruckelshaus Citation2017).

Limitations and simplifications

The InVEST ecosystem service models were designed and tailored to report service returns at Belize’s national and planning region scales. The quality and scarcity of input data, and the uncertainty of the models, was a limiting factor. We did not consider advances in technology as a driver of change in the future management scenarios (Villasante and Sumaila Citation2010) or explicitly consider climate change impacts in the ecosystem services valuation. Ecosystem service beneficiaries were assumed to be uniform across the study area in the absence of information to properly disaggregate by demographic or beneficiary type (Boyd and Banzhaf Citation2007; Daw et al. Citation2011; Myers et al. Citation2013), limiting what can be said about the environmental justice of the zoning scheme (Flannery and Ellis Citation2016).

To address some of these limitations, CZMAI has partnered with technologists, NGOs, and sustainability science students to design a monitoring protocol. Given the short time horizon for this coastal plan (2010–2025) and resource constraints, we mapped human uses at the zoning scale, which was sufficient for answering questions related to near-term decisions and policies but could be improved and more finely delineated in the future. Since the Plan will be revised over a 4-year time period, CZMAI’s Data Centre under the Marine Conservation & Climate Adaptation Project is responsible for managing an inventory of development sites and activities for cayes and coastal areas within the nine planning regions. This will serve to assess ICZM Plan compliance and monitor proper implementation of the development guidelines for each region within the 4-year time period. To fulfill the final strategic objective, CZMAI intends to incorporate climate change effects in an updated ecosystem service assessment as they revisit the Plan.

Lessons learned

Change takes time. The process described here took 6 years, building on efforts from many institutions and individuals in Belize since the 1990s, and benefited from long-term commitment by the core team and flexible, multi-year philanthropic and institutional resources. Turnover of professionals in government and allied institutions, as well as other realities facing national development planning, is likely to make similar processes take longer than anyone imagines at the outset. Without the long-term institutional commitment and flexible resources from engaged donors supporting the team and our work, the Belize Plan might not have been adopted. Our core team, separated by more than 6000 km, was limited to conducting three major iterations. It’s likely that further iterations could have made additional, marginal improvements to the Plan and scientific tools.

Previous planning efforts by NatCap and others highlight the importance of scientists, planners, and stakeholders codeveloping objectives, scenarios, science, and tools to ensure that resulting plans and policies will facilitate responsible decision-making and be meaningful to those involved (Cash et al. Citation2003; McKenzie et al. Citation2014; Ruckelshaus et al. Citation2015; Schultz et al. Citation2015; Posner et al. Citation2016). Yet, effective stakeholder engagement requires clear, frequent, and thoughtful communication to a diverse set of stakeholders for successful and broadly supported science-policy processes like coastal and ocean planning (Rosenthal et al. Citation2015; Arkema and Ruckelshaus Citation2017). Many people and institutions, including environmental organizations, government agencies and ministries, local universities, and civil society, supported the process in Belize by providing valuable local knowledge. The ICZM Plan gained support from various sectors and interests – from tourism to fishing to environmental organizations – because stakeholders felt that they could inform the process and could see how the science and policy questions were relevant to their interests. This came from multiple, sequential interactions using visual products, like maps and cumulative impacts, with metrics that were important to stakeholders, such as lobster catch and revenue and expenditures from tourism.

Embedding ecosystem services into the Belize planning process resulted in a science-based and stakeholder-supported plan. We found that bringing together science, policy, and stakeholders can have beneficial outcomes for each element of the process. We believe that an ecosystem service approach facilitates the interaction between these three elements. In particular, we find that good practice in coastal and ocean planning applies a stepwise, iterative approach to engage stakeholders, incorporates different visions and values into coastal plans, keeps partners informed, and enables researchers to improve data and methods over time.

Initially, we struggled to harmonize seemingly disparate information sources, but a unique combination of regional monitoring data, expert opinion, and nontraditional sources advanced our understanding of anthropogenic threats and conservation needs in the coastal zone. The development of simple, open-source models (Arkema et al. Citation2013, Citation2015; Wood et al. Citation2013; Guannel et al. Citation2015, Citation2016) gave the plan a base in existing scientific and stakeholder information that could be understood and assessed by people in Belize affected by coastal and ocean management decisions. CZMAI staff served as early end-users enabling the NatCap team to codify user requirements, house the models in planner-friendly tools (http://www.naturalcapitalproject.org), and incorporate capacity development into the planning process. Repeatedly revisiting steps in the process improved scientific outputs over time, enhanced buy-in among stakeholders, and supported uptake by policymakers to move the process forward through key decision points. This made the process more transparent and refined communication products to be easier to update during future plan revisions, which are anticipated every four years.

Our experience indicates that coastal plans that consider trade-offs among alternative scenarios by comparing key metrics for ecosystem services will resonate more deeply with local people, planners, government officials, and policy-makers. The framework presented here is designed to be modular, offering scalable solutions to coastal nations seeking to assess the response of ecosystem services and biodiversity to different policy and management options, meet sustainable development goals (Pereira et al. Citation2013; Geijzendorffer et al. Citation2015), or Open Standards conservation targets (Conservation Measures Partnership Citation2013; Grantham et al. Citation2010), and its utility should not be limited to places with similar environmental, social, or political conditions. Using a portfolio of conservation strategies and actions outlined in the ICZMP, our in-country partners are in dialogue with the Government of Belize to address the key indicators needed for the BBRRS to be removed from UNESCO’s ‘in danger’ list.

Conclusion

Through an ecosystem services approach that involved stakeholders, we worked with Belizeans to consider different visions for future environmental stewardship and economic prosperity. We mapped eight human uses and designed alternative coastal plans to protect values expressed by local communities. Spatially explicit information for three ecosystem services was translated into useful, specific recommendations for management and policies. The preferred zoning scenario, Informed Management, designated areas for preservation, restoration, and development uses, offering the potential for interagency coordination and management at both the national scale and within Belize’s nine coastal planning regions. Most importantly, the scenarios and approaches to modeling future change were codeveloped by scientists, policy-makers, and stakeholders. By documenting our approach and the lessons we took from it, we suggest a comprehensive, science-based, community-driven process for planning that can be applied in new places seeking sustainable development and economic growth to promote the long-term viability of their coasts and oceans.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the organizations who provided local knowledge and support during this process. First, Melanie McField of the Healthy Reefs Initiative for making the initial connection and advising the project partners; A. Guerry, J. Toft, G. Guannel, J. Faries, J. Silver, R. Griffin, D. Fisher, K. Wyatt, and many others at the Natural Capital Project for leading the development and testing of marine InVEST models; Wildlife Conservation Society for fisheries data; V. Gillett, C. Gillett, I. Gillett, Miss Hazel, and the entire Coastal Zone family for hosting the NatCap team during site visits and in-country workshops; J. Robinson, E. Cherrington, L. Burke, H. Fox, and E. Selig for reviewing early findings. We also acknowledge the contribution of countless researchers, managers, and specialists who worked tirelessly since the Coastal Zone Act of 1998. Without your commitment and patience, a national ICZM Plan for Belize would not have been possible. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers whose suggestions greatly improved the manuscript. Vector images of coral, mangrove, and seagrass were obtained from the Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (ian.umces.edu/imagelibrary/).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agostini VN, Margles SW, Schill SR, Knowles JE, Blyther RJ. 2010. Marine zoning in Saint Kitts and Nevis: a path towards sustainable management of marine resources. The Nature Conservancy. [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://www.marineplanning.org/Case_Studies/StKitts_Report.html.

- Arkema KK, Abramson SC, Dewsbury BM. 2006. Marine ecosystem-based management: from characterization to implementation. Front Ecol Environ. 4(10):525–532.

- Arkema KK, Guannel G, Verutes G, Wood SA, Guerry A, Ruckelshaus M, Kareiva P, Lacayo M, Silver JM. 2013. Coastal habitats shield people and property from sea-level rise and storms. Nat Clim Chang. 3:913–918.

- Arkema KK, Verutes G, Bernhardt JR, Clarke C, Rosado S, Canto M, Wood SA, Ruckelshaus M, Rosenthal A, McField M, et al. 2014. Assessing habitat risk from human activities to inform coastal and marine spatial planning: a demonstration in Belize. Environ Res Lett. 9:114016.

- Arkema KK, Verutes GM, Wood SA, Clarke-Samuels C, Rosado S, Canto M, Rosenthal A, Ruckelshaus M, Guannel G, Toft J, et al. 2015. Embedding ecosystem services in coastal planning leads to better outcomes for people and nature. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 112:7390–7395.

- Arkema KK, Ruckelshaus M. 2017. Transdisciplinary research for conservation and sustainable development planning in the Caribbean. In: Levin P, Poe M, editors. Conservation in the anthropocene ocean: interdisciplinary science in support of nature and people. San Diego (CA): Elsevier.

- Bateman IJ, Harwood AR, Mace GM, Watson RT, Abson DJ, Andrews B, Binner A, Crowe A, Day BH, Dugdale S, et al. 2013. Bringing ecosystem services into economic decision-making: land use in the United Kingdom. Science. 341(6141):45–50.

- Beck M, Ferdaña Z, Kachmar J, Morrison KK, Taylor P. 2009. Best practices for marine spatial planning. Arlington (VA): The Nature Conservancy; [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://www.marineplanning.org/pdf/msp_best_practices.pdf.

- Blackstock KL, Waylen KA, Dunglinson J, Marshall KM. 2012. Linking process to outcomes – internal and external criteria for a stakeholder involvement in river basin management planning. Ecological Econ. 77:113–122.

- Boyd J, Banzhaf S. 2007. What are ecosystem services? The need for standardized environmental accounting units. Ecological Econ. 63(2):616–626.

- Bureau Population Reference. 2013. World population factsheet (pdf). Population Reference Bureau. [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://www.pbr.org.

- Cárcamo PF, Garay-Flühmann R, Squeo FA, Gaymer CF. 2014. Using stakeholders’ perspective of ecosystem services and biodiversity features to plan a marine protected area. Environ Sci Policy. 40:116–131.

- Cash DW, Clark WC, Alcock F, Dickson NM, Eckley N, Guston DH, Jager J, Mitchell RB. 2003. Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 100(14):8086–8091.

- Cherrington EA, Hernandez BE, Trejos NE, Smith OA, Anderson EA, Flores AI, Garcia BC. 2010. Technical report: identification of threatened and resilient mangroves in the Belize barrier reef system. Panama: Water Center for the Humid Tropics of Latin America and the Caribbean (CATHALAC).

- Chess C, Purcell K. 1999. Policy analysis public participation and the environment: do we know what works? Environ Sci Technol. 33(16):2685–2692.

- Coastal Zone Management Act, CAP 329, Laws of Belize, Revised Edition. 2003. Belmopan: Government Printer; [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://www.coastalzonebelize.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/cap329.pdf.

- Conservation Measures Partnership. 2013. Open standards for the practice of conservation. [accessed 2017 Jun 10]. http://cmp-openstandards.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/CMP-OS-V3-0-Final.pdf.

- Cooper E, Burke L, Bood N. 2009. Coastal capital of Belize. The economic contribution of Belize’s coral reefs and mangroves. Washington (DC): World Resources Institute.

- Cornu E, Kittinger JN, Koehn JZ, Finkbeiner EM, Crowder LB. 2014. Current practice and future prospects for social data in coastal and ocean planning. Conserv Biol. 28(4):902–911.

- CZMAI. 2016. Belize integrated coastal zone management plan. Belize City: Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute (CZMAI); [accessed 2016 Sep 19]. http://www.coastalzonebelize.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/BELIZE-Integrated-Coastal-Zone-Management-Plan.pdf.

- Daw T, Brown K, Rosendo S, Pomeroy R. 2011. Applying the ecosystem services concept to poverty alleviation: the need to disaggregate human well-being. Environ Conserv. 38(4):370–379.

- Day J. 2008. The need and practice of monitoring, evaluating and adapting marine planning and management—lessons from the Great Barrier Reef. Mar Pol. 32:823–831.

- Day V, Paxinos R, Emmett J, Wright A, Goecker M. 2008. The marine planning framework for South Australia: a new ecosystem-based zoning policy for marine management. Mar Pol. 32:535–543.

- De Leon González ME, Carrasco RG, Carcamo RA. 2008. A Cohort analysis of Spiny Lobster from Belize. [accessed 2016 Sep 5]. http://www.ub.edu.bz/download.php?f=nrm/Carcamo_R_lobster.pdf.

- Domínguez-Tejo E, Metternicht G, Johnston E, Hedge L. 2016. Marine spatial planning advancing the ecosystem-based approach to coastal zone management: a review. Mar Pol. 72:115–130.

- Douvere F. 2008. The importance of marine spatial planning in advancing ecosystem-based sea use management. Mar Pol. 32(5):762–771.

- Douvere F, Ehler CN. 2009. New perspectives on sea use management: initial findings from European experience with marine spatial planning. J Environ Manage. 90(1):77–88.

- Ehler C. 2008. Conclusions: benefits, lessons learned, and future challenges of marine spatial planning. Mar Pol. 32(5):840–843.

- Ehler C, Douvere F. 2009. Marine spatial planning, a step-by-step approach towards ecosystem-based management. [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://www.oceandocs.org/handle/1834/4475.

- European Commission. 2011. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Publications Office of the European Union. [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/marine/pdf/1_EN_ACT.pdf.

- Flannery W, Ellis G. 2016. Exploring the winners and losers of marine environmental governance (edited interface collection). Plann Theory Pract. 17(1):121–151.

- Geijzendorffer IR, Regan EC, Pereira HM, Brotons L, Brummitt N, Gavish Y, Haase P, Martin CS, Mihoub JB, Secades C. 2015. Bridging the gap between biodiversity data and policy reporting needs: an essential biodiversity variables perspective. J Appl Ecol. 53(5):1341–1350.

- Gissi E, de Vivero JLS. 2016. Exploring marine spatial planning education: challenges in structuring transdisciplinarity. Mar Pol. 74:43–57.

- Grantham HS, Bode M, McDonald-Madden E, Game ET, Knight AT, Possingham HP. 2010. Effective conservation planning requires learning and adaptation. Front Ecol Environ. 8(8):431–437.

- Guannel G, Ruggiero P, Faries J, Arkema K, Pinsky M, Gelfenbaum G, Guerry A, Kim CK. 2015. Integrated modeling framework to quantify the coastal protection services supplied by vegetation. J Geophys Res. 120(1):324–345.

- Guannel G, Arkema KK, Ruggiero P, Verutes G. 2016. The power of three: coral reefs, seagrasses and mangroves protect coastal regions and increase their resilience. PLoS One. 11(7):e0158094.

- Guerry AD, Polasky S, Lubchenco J, Chaplin-Kramer R, Daily GC, Griffin R, Ruckelshaus M, Bateman IJ, Duraiappah A, Elmqvist T, et al. 2015. Natural capital and ecosystem services informing decisions: from promise to practice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 112(24):7348–7355.

- Guerry AD, Ruckelshaus MH, Arkema KK, Bernhardt JR, Guannel G, Kim C-K, Marsik M, Papenfus M, Toft JE, Verutes G, et al. 2012. Modeling benefits from nature: using ecosystem services to inform coastal and marine spatial planning. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manage. 8:107–121.

- Halpern BS, Diamond J, Gaines S, Gelcich S, Gleason M, Jennings S, Lester S, Mace A, McCook L, McLeod K, et al. 2012. Near-term priorities for the science, policy and practice of Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning (CMSP). Mar Pol. 36(1):198–205.

- Halpern BS, Walbridge S, Selkoe KA, Kappel CV, Micheli F, D’Agrosa C, Bruno JF, Casey KS, Ebert C, Fox HE, et al. 2008. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science. 319(5865):948–952.

- Henrichs T, Zurek M, Eickhout B, Kok K, Raudsepp-Hearne C, Ribeiro T, van Vuuren D, Volkery A. 2010. Ecosystems and human well-being: a manual for assessment practitioners. Washington (DC): Island Press.

- Hobday AJ, Smith ADM, Stobutzki IC, Bulman C, Daley R, Dambacher JM, Deng RA, Dowdney J, Fuller M, Furlani D, et al. 2011. Ecological risk assessment for the effects of fishing. Fish Res. 108(2–3):372–384.

- Hockings M. 2003. Systems for assessing the effectiveness of management in protected areas. BioScience. 53(9):823–832.

- Kittinger JN, Koehn JZ, Le Cornu E, Ban NC, Gopnik M, Armsby M, Brooks C, Carr MH, Cinner JE, Cravens A, et al. 2014. A practical approach for putting people in ecosystem-based ocean planning. Front Ecol Environ. 12(8):448–456.

- Koehn JZ, Reineman DR, Kittinger JN. 2013. Progress and promise in spatial human dimensions research for ecosystem-based ocean planning. Mar Pol. 42:31–38.

- Leslie HM, McLeod KL. 2007. Confronting the challenges of implementing marine ecosystem-based management. Front Ecol Environ. 5(10):540–548.

- Little SA, Watson WH III. 2005. Differences in the size at maturity of female american lobsters, Homarus americanus, captured throughout the range of the offshore fishery. J Crust Biol. 25(4):585–592.

- Lynam T, Jong WD, Sheil D, Kusumanto T, Evans K. 2007. A review of tools for incorporating community knowledge, preferences, and values into decision making in natural resources management. Ecol Soc. 12(1):5.

- Maguire B, Potts J, Fletcher S. 2012. The role of stakeholders in the marine planning process—stakeholder analysis within the Solent, United Kingdom. Mar Pol. 36(1):246–257.

- McKenzie E, Posner S, Tillmann P, Bernhardt JR, Howard K, Rosenthal A. 2014. Understanding the use of ecosystem service knowledge in decision making: lessons from international experiences of spatial planning. Environ Plann C. 32:320–340.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being. Washington (DC): Island Press; [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/index.htm.

- Myers S, Gaffikin L, Golden CD, Ostfeld RS, Redford K, Ricketts T, Turner WR, Osofsky SA. 2013. Human health impacts of ecosystem alteration. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 110(47):18753–18760.

- Natural Capital Project. 2013. Belize ICZM plan map viewer. [accessed 2016 Aug 15]. http://www.geointerest.frih.org/NatCap.

- Neal D, Ariola E, Muschamp W. 2008. Vulnerability assessment of the Belize coastal zone. In: UNFCCC, editor. Enabling activities for the preparation of Belize’s Second National Communication (SNC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) project. Belize: United Nations Development Programme.

- Pereira HM, Ferrier S, Walters M, Geller GN, Jongman RHG, Scholes RJ, Bruford MW, Brummitt N, Butchart SHM, Cardoso AC, et al. 2013. Essential biodiversity variables. Science. 339(6117):277–278.

- Posner S, McKenzie E, Ricketts TH. 2016. Policy impacts of ecosystem services knowledge. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 113:1760–1765.

- Raudsepp-Hearne C, Peterson GD, Bennett EM. 2010. Ecosystem service bundles for analyzing tradeoffs in diverse landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 107(11):5242–5247.

- Reed MS. 2008. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biol Conserv. 141(10):2417–2431.

- Reed MS, Graves A, Dandy N, Posthumus H, Hubacek K, Morris J, Prell C, Quinn CH, Stringer LC. 2009. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J Environ Manage. 90(5):1933–1949.

- Rosenthal A, Verutes G, Arkema K, Clarke C, Canto M, Rosado S, Wood S. 2012. InVEST scenarios case study: coastal Belize developing scenarios to assess ecosystem service tradeoffs: natural capital project. World Wildlife Fund. [accessed 2016 Aug 5]. http://www.naturalcapitalproject.org/pubs/Belize_InVEST_scenarios_case_study.pdf.

- Rosenthal A, Verutes G, McKenzie E, Arkema KK, Bhagabati N, Bremer LL, Olwero N, Vogl AL. 2015. Process matters: a framework for conducting decision-relevant assessments of ecosystem services. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manage. 11(3):190–204.

- Ruckelshaus M, Klinger T, Knowlton N, DeMaster DP. 2008. Marine ecosystem-based management in practice: scientific and governance challenges. BioScience. 58(1):53–63.

- Ruckelshaus M, McKenzie E, Tallis H, Guerry A, Daily G, Kareiva P, Polasky S, Ricketts T, Bhagabati N, Wood SA, et al. 2015. Notes from the field: lessons learned from using ecosystem service approaches to inform real-world decisions. Ecological Econ. 115:11–21.

- Samhouri JF, Levin PS. 2012. Linking land- and sea-based activities to risk in coastal ecosystems. Biol Conserv. 145(1):118–129.

- Schultz L, Folke C, Österblom H, Olsson P. 2015. Adaptive governance, ecosystem management, and natural capital. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 112(24):7369–7374.

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. 2004. The ecosystem approach, (CBD guidelines) Montreal: secretariat of the convention on biological diversity; p. 150. [accessed 2016 May 5]. https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/ea-text-en.pdf.

- Sharp R, Tallis HT, Ricketts T, Guerry AD, Wood SA, Chaplin-Kramer R, Nelson E, Ennaanay D, Wolny S, Olwero N, et al. 2016. InVEST user’s guide. The Natural Capital Project, Stanford University. [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://data.naturalcapitalproject.org/nightly-build/invest-users-guide/html/.

- Statistical Institute of Belize. 2010. Belize population and housing census 2010. Belmopan: The Statistical Institute of Belize. [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://www.sib.org.bz/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Census_Report_2010.pdf.

- TEEB. 2010. Mainstreaming the economics of nature: a synthesis of the approach, conclusions and recommendations of TEEB. [accessed 2016 Aug 27]. http://www.teebweb.org/publication/.

- UN General Assembly. 2010. Oceans and law of the sea, division for ocean affairs and the law of the sea. Reports of the secretary-general. [accessed 2015 Aug 25]. http://www.un.org/depts/los/ecosystem_approaches/ecosystem_approaches.htm.

- UNEP and IOC-UNESCO. 2009. An assessment of assessments, findings of the group of experts. Start-up phase of a regular process for global reporting and assessment of the state of the marine environment including socio-economic aspects. Paris: IOC-UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2016. Danger listed site Belize barrier reef gets visionary integrated management plan. [accessed 2016 Sep 1]. http://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1455/.

- Verutes GM, Rosenthal A. 2014. Using simulation games to teach ecosystem service synergies and trade-offs. Environ Pract. 16(3):194–204.

- Villasante S, Sumaila UR. 2010. Estimating the effects of technological efficiency on the European fishing fleet. Mar Pol. 34(3):720–722.

- Wabnitz CC, Andréfouët S, Torres-Pulliza D, Müller-Karger FE, Kramer PA. 2008. Regional-scale seagrass habitat mapping in the Wider Caribbean region using Landsat sensors: applications to conservation and ecology. Rem Sens Environ. 112(8):3455–3467.

- Waite R, Burke L, Gray E, van Beukering P, Brander L, MacKenzie E, Pendleton L, Schuhmann P, Tompkins, EL. 2014. Coastal capital: ecosystem valuation for decision making in the Caribbean. World Resources Institute. [accessed 2015 Aug 9]. http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/362289.

- White C, Halpern BS, Kappel CV. 2012. Ecosystem service tradeoff analysis reveals the value of marine spatial planning for multiple ocean uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 109(12):4696–4701.

- Williams A, Dowdney J, Smith ADM, Hobday AJ, Fuller M. 2011. Evaluating impacts of fishing on benthic habitats: a risk assessment framework applied to Australian fisheries. Fish Res. 112(3):154–167.

- Wood SA, Guerry AD, Silver JM, Lacayo M. 2013. Using social media to quantify nature-based tourism and recreation. Sci Rep. 3:2976.

- World Wide Fund for Nature. 2016. Protecting people through nature report: natural world heritage sites as drivers of sustainable development. Gland: WWF; [accessed 2016 Jul 19]. http://assets.worldwildlife.org/publications/867/files/original/WWF_Dalberg_Protecting_people_through_nature_LR_singles.pdf.

- Worm B, Hilborn R, Baum JK, Branch TA, Collie JS, Costello C, Fogarty MJ, Fulton EA, Hutchings JA, Jennings S, et al. 2009. Rebuilding global fisheries. Science. 325(5940):578–585.