ABSTRACT

Trust has been acknowledged as an important aspect of interorganizational relationships. Yet, limited attention has been paid to the importance of trust in the light of coopetitive interactions, i.e. simultaneously cooperating and competing. Research on trust has started to acknowledge that more trust may not always be better, and that trust and distrust are separate and distinct phenomena. Whilst coopetition research has mentioned the important role of trust, the potential role of distrust is even less acknowledged, although it may be particularly relevant due to the tensions, risks, and uncertainties involved. The purpose of this paper is to identify limitations and gaps in the extant literature on trust in coopetition, bring promising research opportunities into light, and create an agenda for future research focused on the roles of both trust and distrust in coopetition. By means of a systematic literature review, we find that the importance of trust in different phases of coopetition has been acknowledged by prior research, yet deeper explanations of how, when, and why different aspects of trust and distrust matter to coopetition are missing. A normative view on trust prevails and the potential fruitfulness of distrust is neglected. Based on these limitations, an agenda including six promising research avenues is constructed.

1. Introduction

Trust is critical for interorganizational relationships (Gulati, Citation1995; McEvily & Zaheer, Citation2005; Nielsen, Citation2011; Poppo & Zenger, Citation2002; Robson, Katsikeas, & Bello, Citation2008) and particularly relevant in the light of interpartner competition (Krishnan, Martin, & Noorderhaven, Citation2006). While we see trust as a phenomenon fundamentally rooted in the individual level, we acknowledge its multi-level nature (Fulmer & Dirks, Citation2018) as it diffuses within the social context of groups and organisations and can take the form of interorganizational trust (Vanneste, Citation2016; Zaheer, McEvily, & Perrone, Citation1998). Interorganizational trust has been argued to reduce concerns about partner opportunism, foster cooperation, and facilitate knowledge sharing (Das & Teng, Citation1998; Dirks & Ferrin, Citation2001; Nielsen & Nielsen, Citation2009). Especially when a relationship involves increased interdependence, risks, and uncertainty, the importance of trust is amplified (Das & Teng, Citation2004; Latusek & Vlaar, Citation2018; Li, Citation2012; McEvily, Perrone, & Zaheer, Citation2003; Schilke & Cook, Citation2015). Following this notion, Li (Citation2017) has called for research that pays further attention to trust-as-choice under conditions of uncertainty and vulnerability.

Such conditions are particularly salient in relationships involving coopetition, which refers to simultaneous pursuit of cooperation and competition (Bengtsson & Kock, Citation2000). Contributing to a deeper understanding of the multifaceted interactions within interorganizational relationships (Dorn, Schweiger, & Albers, Citation2016; Padula & Dagnino, Citation2007), the concept of coopetition has attracted increased scholarly attention (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, Citation2016). This body of research suggests that cooperation and competition are not opposite ends on a single continuum and do not cancel each other out; rather they take place on two separate continua and can simultaneously take place (Bengtsson, Eriksson, & Wincent, Citation2010). Approaching cooperation and competition as a duality enables a realisation of the dual benefits of the two logics of interaction, i.e. cooperating to be able to share knowledge, gain access to strategically important resources, and jointly create value, while simultaneously competing to remain alert, stimulate one another, and individually attain a bigger share of that value. A typical example of successful coopetition is the partnership between Samsung Electronics and Sony Corporation, which enabled two fierce competitors to cooperate and create a new generation of LCD panels (Gnyawali & Park, Citation2011). To realise the fruitfulness of coopetition, however, firms engage in tension-filled interactions and their choosing to become vulnerable to the partner-competitor, involves a leap-of-faith. This, because relying on a partner with partially conflicting interests could also lead to negative consequences. While coopetition is seen as potentially more beneficial than alliances without competitive elements (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, Citation2009), it has also been described as a double-edge sword (Bouncken & Fredrich, Citation2012) and an uncertain endeavour, in which trust is suggested to play an important role.

Due to increased interpartner uncertainty and the risks involved, coopetition has been argued to ‘produce[s] a unique context for trust, in that a firm must trust its partner in two quite different ways’ (Morris, Koçak, & Özer, Citation2007, p. 41). This implies that trust needs to be present both in the cooperative arena (i.e. in their willingness to cooperate) and in the competitive arena (i.e. that they will not engage in harmful competitive actions). Building upon this, we argue that coopetition fulfils three critical elements, which according to Li (Citation2012) constitute a context particularly relevant to study trust within. First, coopetition entails interdependence, increased levels of uncertainty, and concerns about partner opportunism. Second, in coopetitive interactions control mechanisms cannot easily be implemented. Third, the consequences of failure may be more severe as the partner is at the same time a competitor.

Whereas a number of calls have been made for studying the role of trust in coopetition, recognising its importance (see for example Dorn et al., Citation2016), there is still limited knowledge on whether, to what extent, and how these calls have been addressed. In this paper, we argue that investigating the current state of research on trust in coopetition is important because it can facilitate a synthesis of the extant literature. Importantly, further research on this topic can be encouraged, and a bridge between trust and coopetition scholars can be developed with unique benefits for both literature streams. On the one hand, the context of coopetition can provide trust scholars with important insights into the sources, nature, and role of trust in interorganizational relationships. On the other hand, coopetition research will benefit from drawing upon insights provided by research devoted to trust within and between organisations to increase the understanding of the multi-level nature of coopetition and what drives coopetition emergence, management, and evolution. With this in mind, we conduct a narrow systematic literature review (Crossan & Apaydin, Citation2010) on how trust has been studied in coopetition, with the purpose of identifying limitations and gaps, bringing promising research opportunities into light, and creating an agenda for future research focused on the roles of both trust and distrust in the simultaneous pursuit of cooperation and competition. While a broader review addressing a more general phenomenon would uncover more insights on the role of trust, and would allow a synthesis of a broader body of research, the narrowness of our review (i.e. focusing only on coopetition) enables us to build a more precise research agenda.

The review follows Bengtsson and Raza-Ullah’s (Citation2016) coopetition driver-process-outcomes (DPO) framework integrating critical themes within research on coopetition. It also draws upon and extends the work of Nielsen (Citation2011) on the coevolution of trust and alliances by specifically focusing on interorganizational relationships involving simultaneous cooperation and competition and the specificities thereof.

In the following section, the specificities of coopetition are presented, and selected aspects identified in prior research on trust (i.e. dimensionality, types, levels, dynamic nature) are discussed. This theoretical background served as a guide to the reading and analysis of the papers under review and facilitated the coding process, as key concepts discussed in the extant literatures on trust and coopetition were mobilised for analysing the included contributions. Thereafter, the methods used for selecting and analysing the papers are described. Finally, after presenting the results of the review in Section 4, the paper concludes by offering a research agenda for both coopetition and trust scholars.

2. Theoretical background: Constructing a guide for the literature review

2.1. Insights from the coopetition literature

Referring to the simultaneous presence of cooperation and competition, the concept of coopetition (Ansari, Garud, & Kumaraswamy, Citation2016; Bengtsson & Kock, Citation2000; Gnyawali & Park, Citation2011) contributes to a deeper understanding of the multifaceted interactions that take place between and among organisations (Padula & Dagnino, Citation2007). As Dorn et al. (Citation2016, p. 1) note, ‘the rise of coopetition reflects an increasing awareness of the complexity of relations between economic agents’. In particular, whereas cooperation and competition have traditionally been seen as opposites, or as different ends of the same continuum, in research on coopetition the cooperative and competitive dimensions are approached as on two separate continua (Bengtsson et al., Citation2010; Luo, Citation2007). Depending on the level of focus, definitions of coopetition vary. With a focus on dyadic coopetition, for instance, Bengtsson and Kock (Citation2000, p. 412) define coopetition as the ‘dyadic and paradoxical relationship that emerges when two firms cooperate in some activities, such as in a strategic alliance, and at the same time compete with each other in other activities’. While in the former definition the focus is on a pair of competing firms and the two dimensions of coopetition are divided between activities (e.g. two direct competitors cooperate in a technology development project and at the same time compete in commercialising the products), coopetition has also been studied in value-nets (see Brandenburger & Nalebuff, Citation1996), where cooperation and competition are divided between actors (e.g. firm A cooperates with firm B that has close linkages with firm C that is a competitor to firm A) and in buyer-supplier relationships (Wilhelm & Sydow, Citation2018).

In this paper, we view coopetition as an interactive, dynamic and multi-level social process, which is shaped by both sides of a relationship as individuals interact, as the market develops, and as firms make different strategic moves and countermoves. As a multi-level process, the different levels interact, and influence each other (Chiambaretto & Dumez, Citation2016). Importantly, while coopetitive interactions take place between firms, individuals and their perceptions, actions, and interactions play a vital role in this process (Dahl, Kock, & Lundgren-Henriksson, Citation2016) and prior studies have called for more research efforts on the microfoundations of coopetition (Bouncken, Gast, Kraus, & Bogers, Citation2015). It is worthy to note, however, that coopetition between individuals may be a distinct phenomenon that has not been addressed in this body of literature and is not part of the focus of our review. The dynamic and multi-level nature of coopetition is highlighted by the coopetition driver-process-outcomes (DPO) framework suggested Bengtsson and Raza-Ullah (Citation2016). This framework is important for this review as it guides the reading of the papers in terms of where in this framework trust is discussed in the reviewed papers. Drivers of coopetition refer to aspects motivating firms to engage in coopetition (i.e. the antecedents of the interaction). The extant research on the process-related aspects of coopetition has focused on tensions and how the relationship is managed, while the outcomes are related to performance, innovation, knowledge, or relation (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, Citation2016).

Moreover, this review is guided by prior research asserting that coopetition is a beneficial yet tension-filled and uncertain endeavour. As with alliances, coopetition can, for example, give access to strategically important resources, enable cost reduction, and enhance firm performance (Das & Teng, Citation2000; Gnyawali & Park, Citation2011; Luo, Citation2007). In addition, coopetition brings added benefit as competitors possess similar knowledge of markets and technologies (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, Citation2009). This has been argued to empower coopetitors to together determine the nature of technological standards, to disrupt the structure of the industry in which they operate (Gnyawali & Park, Citation2011) and to facilitate radical-business model innovations (Ritala & Sainio, Citation2014). Empirical studies have highlighted the beneficial role of coopetition for large corporations such as Sony and Samsung (as previously mentioned). Similarly, Le Roy and Fernandez (Citation2015) show that TAS and Astrium, two rivals and leaders in the European space industry, jointly developed an innovation programme to manufacture telecommunication satellites. There is also empirical support for the fruitfulness of coopetition for SMEs. For instance, high-tech SMEs in the ICT industry in Sweden engage in coopetition to ensure their long-term survival (Näsholm, Bengtsson, & Johansson, Citation2018) and local craft breweries in Germany improved their market reach and growth by cooperating with their competitors (Kraus, Klimas, Gast, & Stephan, Citation2019).

On the other hand, coopetition is also challenging to manage as it includes tensions, risks, and uncertainties. First, coopetition is paradoxical as it embodies opposing forces of cooperation and competition, which can both stimulate the relationship and jeopardise the realisation of sought benefits. Prior research has found that tensions and contradictions, such as value creation versus value appropriation, and knowledge sharing versus knowledge protection, (Fernandez & Chiambaretto, Citation2016) arise at multiple levels (Le Roy & Fernandez, Citation2015). For example, on the individual level, coopetition can entail stress, as conflicting emotions and identifications (Näsholm & Bengtsson, Citation2014). Second, coopetition involves the risks of partner opportunism and unintentional knowledge leakage (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, Citation2009) even more than non-competitive alliances as the partners are at the same time competitors. The behaviour of a competitor as a partner becomes even less predictable and potentially more detrimental, making behavioural uncertainty a major concern in coopetition (Krishnan et al., Citation2006) and trust even more critical.

Whereas the abovementioned particularities of coopetition make trust particularly relevant for understanding the processes of coopetition, prior literature reviews on coopetition indicate that trust has not received adequate attention in coopetition research. While these reviews most often do not particularly discuss trust (e.g. Bouncken et al., Citation2015; Walley, Citation2007), trust is mentioned in a few reviews as critical in coopetition and as a promising research topic. When mentioned, it is referred to only as a relational mechanism for managing coopetitive interactions (Dorn et al., Citation2016) or as a relationship-related outcome of coopetition (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, Citation2016). Complementing these reviews, our narrow literature review sheds light on this under-researched area in the coopetition literature and supports the creation of a well-grounded and concise research agenda on the distinct roles of trust and distrust along the different phases of coopetition.

2.2. Insights from the trust literature

Prior research suggests that trust is an interactive process (Dietz, Citation2011) closely related to uncertainty and risk (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Citation1995; Das & Teng, Citation1998). Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies (Citation1998, p. 439) define trust as, ‘confident positive expectations regarding another’s conduct’. However, trust also includes the willingness to become vulnerable based on these confident positive expectations (Li, Citation2017; McEvily & Tortoriello, Citation2011) and on beliefs about the other’s trustworthiness in terms of ability, benevolence, and integrity (Mayer et al., Citation1995) or predictability and reliability (for a discussion on dimensions of trust, see Dietz & den Hartog, Citation2006). In other words, trust is not only attitudinal, but also reflects intentionality (McEvily et al., Citation2003) as trust ‘transforms the attitude to a behaviour’ (Li, Citation2017, p. 9). Trust influences how actions taken by the partner are interpreted and how their future behaviour is assessed (Dirks & Ferrin, Citation2001), and a decision to trust under uncertainty and vulnerability is made, i.e. trust-as-choice (Li, Citation2017). This process includes an assessment, a decision, a risk-taking act, and feedback on the initial assessment (Dietz, Citation2011, p. 215), which is not viewed here as a linear and stepwise process. In addition, this paper adopts the view that trust-as-choice includes an element of calculated expectation, yet considering difficulties in predicting behaviour there is also a less rational component of trust (Lumineau, Citation2017; McEvily et al., Citation2003). Further, acknowledging the multi-level nature of trust, trust is seen as a fundamentally individual-level phenomenon, which can also diffuse within the boundaries of an organisation and across organisations over time (Currall & Inkpen, Citation2002, Citation2006; McEvily & Zaheer, Citation2005). Thus, trust is shaped by the interactions between social actors situated at multiple levels.

Another important insight from prior literature guiding the reading and analysis of the papers in this review, is that trust plays different roles depending on the evolutionary phase of an alliance. The model by Nielsen (Citation2011) illustrates that first, trust serves as an antecedent during the early alliance formation phase, as it influences partner selection and motivates firms to rely on others for fulfilling demanding strategic goals. Second, trust may serve as a moderator during the implementation phase, meaning that trust influences contract negotiation, complements monitoring of the partner, facilitates the emergence of plural governance, and enhances resource integration and knowledge exchange. Third, Nielsen (Citation2011) suggests that trust can also be an outcome of a relationship, which influences perceptions of risks and determines the very continuity of the alliance. Following a similar notion, Akrout (Citation2015) suggests that different forms of trust (i.e. calculative, cognitive and affective) are more important at different phases of a buyer-supplier relationship (i.e. exploration, expansion, and maintenance).

Further, the view that trust has both a bright and a dark side is adopted. Trust is an important social element for interorganizational relationships (Zaheer et al., Citation1998) because, among other benefits, it facilitates transparency, openness, embracement of uncertainty, smooth information and knowledge sharing, joint problem solving, and reduction of negotiation and monitoring costs (Claro, Hagelaar, & Omta, Citation2003; Dyer & Chu, Citation2003; Latusek & Vlaar, Citation2018; McEvily & Zaheer, Citation2005; Möllering, Citation2001; Schilke & Cook, Citation2013). Yet, despite the beneficial role of trust in interorganizational relationships, prior research has suggested that too much trust may also entail detrimental effects and can lead to unsuccessful judgments about the nature of the relationship, or about the intentions of the partner. In particular, drawbacks of trust relate to strategic inflexibility, overconfidence, limited motivation to negotiate and monitor the other party, persistence of non-productive relationships, and inability to realise partner opportunism (e.g. Patzelt & Shepherd, Citation2008; Skinner, Dietz, & Weibel, Citation2014). Here it is suggested that considering both positive and negative aspects of trust is particularly relevant when collaborating with competitors, due to the inherent risks of opportunism and misappropriation.

Moreover, this paper builds upon an emerging body of literature suggesting that trust and distrust are two distinct phenomena, with different benefits and drawbacks (Bijlsma-Frankema, Sitkin, & Weibel, Citation2015; Cho, Citation2006; Dimoka, Citation2010; Engelke, Hase, & Wintterlin, Citation2019; Guo, Lumineau, & Lewicki, Citation2017; Lewicki et al., Citation1998; Lumineau, Citation2017; McKnight & Chervany, Citation2001; Saunders, Dietz, & Thornhill, Citation2014). Challenging the traditional view that trust and distrust are the opposite ends of a continuum (Schoorman, Mayer, & Davis, Citation2007), this emerging stream of research suggest that trust and distrust coexist and can be experienced simultaneously (Guo et al., Citation2017). Distrust, which is based on, ‘confident negative expectations regarding another’s conduct’ (Lewicki et al., Citation1998, p. 439), is suggested to help firms and individuals in dealing with uncertainty but in a different way than trust. Whereas trust relates to hope and faith in the partner, distrust is rooted in value incongruence (Connelly, Miller, & Devers, Citation2012) and facilitates uncertainty management by prescribing vigilance and scepticism, stimulating alertness, encouraging information seeking from alternative sources, and by supporting constructive suspicion (Guo et al., Citation2017).

The theoretical arguments that trust and distrust can be seen as two separate phenomena and that absence of trust does not necessarily mean existence of distrust (Lewicki et al., Citation1998) have also been supported by a few empirical studies (Bijlsma-Frankema et al., Citation2015; Guo et al., Citation2017). For example, in an experimental study with 49 business school students, Komiak and Benbasat (Citation2008) found that building trust and creating distrust are fundamentally distinct and separate processes. These results are supported by Saunders et al. (Citation2014), who provide evidence that trust and distrust not only represent different sets of expectations, but also have distinct behavioural manifestations. Bijlsma-Frankema et al. (Citation2015) showed that distrust is more pervasive in character than trust. In addition to this, research has shown that trust and distrust have distinct influences on the intentions of social actors. Ou and Sia (Citation2010) identified that trust has a stronger influence on positive intentions than the influence that distrust has on negative intentions. Further, supporting the distinction of trust and distrust, Dimoka (Citation2010) empirically verified that trust and distrust consist of different dimensions (i.e. trust relates to assumptions about the partner’s credibility and benevolence, whereas distrust is associated with assumptions about the partner’s discredibility and malevolence), and that they activate different areas of the brain (i.e. trust mainly activates the reward area of the brain and distrust is associated with intense emotions and fear of loss). What is more, prior research has found that trust and distrust differ in the way they influence contract specificity, meaning that they have a distinct impact on interorganizational contracting (Connelly et al., Citation2012). Building on the findings of the above studies, a cornerstone of our suggested research agenda is that trust and distrust are distinct phenomena with discrete nature, drivers, and cognitive and behavioural consequences.

The next section presents the methods for the literature review, describing both how the papers were selected, and how the analysis took place, based on the abovementioned insights from the extant literatures on trust and coopetition.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Selection of the papers

To gain an in-depth understanding of how trust has been discussed in research on coopetition, a systematic literature review (Crossan & Apaydin, Citation2010) was performed using two databases: ISI Web of Knowledge's Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and EBSCO host web's Business Source Premier. The search was of coopetition and trust in both the title and the topic fields of ISI and the title and the abstract fields of EBSCO. To specifically examine research using the concept coopetition and following Bouncken et al. (Citation2015), the search items ‘coopet*’ and ‘co-opet*’ were used. We acknowledge that the narrowness of our review is a limitation, as a broader search would allow a synthesis of a broader and more informative body of research. At the same time, we consider it a strength as it enables the creation of a precise research agenda on trust and distrust in coopetition and facilitates the creation of a solid bridge for trust and coopetition researchers. The choice to limit our review specifically to coopetition was based on the argument that it is a phenomenon with very specific, counter-intuitive and unique characteristics for the study of trust and distrust. Although trust also has been studied in the broader literature on interorganizational cooperation and on horizontal alliances, this body of research often sees competition as harmful for interorganizational alliances. We argue that in simultaneously upholding cooperation and competition, both trust and distrust are critical as they play important roles not only in the cooperative, but also in the competitive arena.

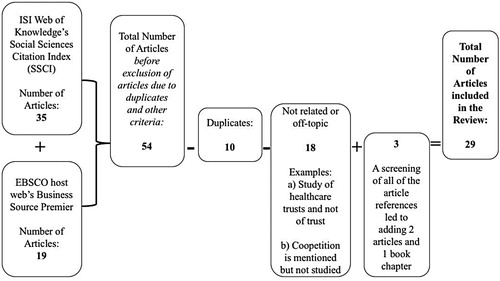

The search was done in April 2019 and resulted in a total of 29 papers, after removing duplicates or papers that were off-topic and adding three contributions (i.e. Castaldo & Dagnino, Citation2009; de Araujo & Franco, Citation2017; Morris et al., Citation2007). These were seen as relevant as they: (i) were frequently referred when coopetition scholars discussed trust-related issues, (ii) directly address trust in coopetition and (iii) mention both concepts in the title and/or abstract (Dorn et al., Citation2016; Wassmer, Citation2010). The process of selecting the papers is illustrated in .

3.2. Analysis of the papers

The analysis of the papers was conducted in three steps. First, the papers were carefully read by both authors, who independently identified and summarised a number of aspects about each paper; purpose, methodology, context, industry, and key findings. Second, the focus was on how the papers included in the review approached a number of aspects of trust, namely definition, type and dimensions, role of trust, level on which trust was discussed, and if distrust was mentioned. These aspects were chosen based on the theoretical background presented in Section 2 and were used as a guide to the analysis of the papers. The coding took place based on these key aspects and we used QSR NVivo 11, which supported the coding process, enabled an initial categorisation of the papers based on their approach to trust, and allowed an early identification of promising research opportunities. This initial categorisation of the papers was discussed and put into an excel file for further comparison. Finally, the findings were further analysed based on the trust-alliance co-evolutionary research model by Nielsen (Citation2011), and the Drivers, Process, Outcomes (DPO) framework of coopetition suggested by Bengtsson and Raza-Ullah (Citation2016). Then, following Wiesmann, Snoei, Hilletofth, and Eriksson (Citation2017), the findings were compared and discussed by both researchers in order for researcher triangulation to take place (Flick, Citation2009). The findings, which served as a platform for identifying unaddressed research areas and for creating a research agenda, are presented in the following section.

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive analysis and overview of the research under review

Although the importance of trust has long been recognised in the body of literature devoted to interorganizational relationships, scholars focusing on coopetition have more recently started to consider this aspect. 72.4% of the papers included in this review were published since 2014, following the overall trend of growth in research articles on the topic of coopetition, as illustrated by other literature reviews (e.g. Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, Citation2016; Bouncken et al., Citation2015; Dorn et al., Citation2016). There a noticeable peak in the number of publications in 2016, which can be explained by a number of special issues on coopetition that were published that year. This shows an emerging interest in the study of trust in coopetition and provides an additional argument for the importance of this literature review and the need for an agenda for future research on the role of trust in coopetition.

Further, research providing insights about the role of trust in coopetition has been published in relatively high-ranked journals (e.g. Industrial Marketing Management, Research Policy, Tourism Management), with a large proportion (6) of them being found in Industrial Marketing Management. This is in line with the general trend in coopetition research as this journal has dedicated several special issues to the topic.

An overview of the publications under review, the manner in which trust is discussed, the methodology used, the studied empirical context and what issue of coopetition is in focus can be found in . Regarding the research methodologies utilised in the publications under review, it has been found that the majority (52%) are qualitative studies (15 in total). One article is classified as applying both qualitative and quantitative methods, nine are quantitative studies, and four out of the 29 contributions are conceptual. This again seems to follow a trend in coopetition research, as the majority of the empirical research on coopetition has been qualitative (Dorn et al., Citation2016), which has been explained by the complex nature of coopetition (Bouncken et al., Citation2015) and the development of the field over time (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, Citation2014).

Table 1. Overview of the publications under review.

Further, the included empirical papers study a variety of different industries and empirical contexts. Many of them focus on more traditional industries, such as steel, construction, and manufacturing. For instance, Tidström (Citation2014) studied a relationship between four competing firms in the steel industry that engaged in coopetition, which enabled them to share information on working practices, exchange knowledge on current market trends and gain benefits from co-specializing, but at the same time remain competitors and offer competing solutions to similar customer bases. Also, a big proportion of the papers (6) discuss the role of trust in the context of tourism. Czernek and Czakon (Citation2016) study, for instance, dyadic coopetition in a Polish tourism region, where rival tourism firms cooperate with each other to jointly promote a tourism destination and create value together, but at the same time remain competitors to individually capture part of that value. While six studies included in this review study fast moving, high-tech, and IT industries, we expected more interest in the role of trust in these types of cases. This since coopetition is not only more common, and particularly fruitful in knowledge-intensive industries (Gnyawali & Park, Citation2011), but interpartner risks are also more salient making trust even more crucial.

4.2. Content analysis

An in-depth analysis of the papers has shown that trust has been studied as an antecedent or driver of coopetition in the formation phase, as a means to manage coopetition in the implementation phase and as a critical success factor of coopetition in the evolution phase.

4.2.1. Trust as an antecedent of coopetition

A few studies devoted to trust in coopetition have discussed trust as a critical element influencing the choice to engage in cooperative relationships with competitors. provides information about the key findings in this stream of coopetition research.

Table 2. Key contributions on the role of trust in coopetition formation.

As shown in , this group of studies has provided insights into the types of trust facilitating coopetition emergence and that different trust-building mechanisms are more important than others depending on the type of coopetition (i.e. network and dyadic coopetition). For instance, it has been reported that while calculation-based trust is important for engaging in dyadic coopetition (Czernek & Czakon, Citation2016), this type of trust does not encourage the formation of network coopetition (Czakon & Czernek, Citation2016). Also, Czakon and Czernek (Citation2016) found that intention-based trust in network coopetition can even result in distrust, which is explicitly presented as harmful and as a source of a decision to avoid coopetition. Further, while some studies discuss the multidimensionality of trust (e.g. de Araujo & Franco, Citation2017), others define trust in a broader and unidimensional manner (e.g. Chim-Miki & Batista-Canino, Citation2017; Kraus et al., Citation2019). This together with the limited number of studies on trust at this phase of coopetition, implies that in the extant coopetition research the multifaceted nature of trust as an antecedent of coopetition remains at large unaddressed. While it has been highlighted that trust matters to coopetition formation, more research is needed to identify the mechanisms through which different types and dimensions of trust (and distrust) facilitate and/or impede the emergence of different types of coopetition.

4.2.2. Trust as a means to manage coopetition

The majority of articles in this review focus on the importance of trust for dealing with the challenging nature of coopetition. Key findings of studies approaching trust as a means to manage coopetition are presented in . In particular, coopetition studies have found that trust enhances coordination (Peters & Pressey, Citation2016), facilitates joint action (Huang & Chu, Citation2015) and encourages interfirm exchange (Baruch & Lin, Citation2012).

Table 3. Key contributions on the role of trust in coopetition implementation.

The importance of trust has been linked to the management of the tension-filled and uncertain nature of coopetition. Touching upon an interesting and promising research topic, studies have noted that trust supports the management of contradictory demands and reduces the negative potential of tensions stemming from coopetition (Fernandez & Chiambaretto, Citation2016; Tidström, Citation2014). Yet different types of tensions may also be related to different types and/or dimensions of trust and/or distrust, which constitutes a noteworthy gap in the extant literature. Further, regarding trust and uncertainty management, Bouncken, Clauß, and Fredrich (Citation2016) found, for instance, that trust is important in vertical coopetition, because it constitutes the cornerstone of relational governance, which reduces uncertainty for the partners. Similarly, many studies approach trust as an informal safeguard against opportunism especially in innovation-related activities (Bouncken & Fredrich, Citation2012; Ratzmann, Gudergan, & Bouncken, Citation2016) and others report that trust-building mechanisms serve as a vehicle to deal with challenges in inter-cluster coopetition, such as the risk of identity loss (Cusin & Loubaresse, Citation2018). In regard to trust building, it has also been shown that third parties can act as knowledge brokers facilitating management of tensions in internal coopetition (Chiambaretto, Massé, & Mirc, Citation2019) or as trust builders supporting the implementation of network coopetition (Porto Gomez, Otegi Olaso, & Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, Citation2016).

Moreover, trust complements contractual complexity and dependency (Ratzmann et al., Citation2016) facilitating the implementation of plural governance, which has found to favour coopetition and improve innovation performance (Bouncken et al., Citation2016). Additionally, although it has been suggested that constructive synergies can be derived from the dialogue between trust and distrust (Guo et al., Citation2017), only one paper discusses that a balance between trust and distrust is needed for successful management of coopetition (Pressey & Vanharanta, Citation2016). Finally, the findings of Grafton and Mundy (Citation2016) that trust does not play a significant role in light of risks stemming from network coopetition and of Idrees, Vasconcelos, and Ellis (Citation2018) that, ‘trust is not a pre-requisite to cooperation nor to related knowledge sharing’ (p. 1369), suggest that a normative perspective on the role of trust in coopetition needs to be avoided.

4.2.3. Trust as a critical success factor of coopetition

In a few papers (one conceptual and two empirical studies), trust is seen as an important relational outcome and key success factor of coopetition (). In particular, it has been suggested that the existence of trust in the evolution phase of a coopetitive relationship represents an indicator of successful coopetition among SMEs (Thomason, Simendinger, & Kiernan, Citation2013) and also, it has empirically been found that trust is part of what defines success in network coopetition (Osarenkhoe, Citation2010). Further, in a mixed-method study of firms coopeting in the manufacturing industry in Hong Kong, Chin, Chan, and Lam (Citation2008) show that for a relationship between coopetitors to be fruitful, the development of trust is a critical success factor and a necessary social element for the maintenance of a relationship. This since problems between the partners are more easily solved, common goals are encouraged, and the adoption of a mutual organisational culture is supported. These papers are in line with the idea that relational outcomes are critical for maintaining coopetitive relationships and for deriving related benefits (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, Citation2016).

Table 4. Key contributions on the role of trust as a critical success factor.

4.2.4. Coevolution of trust and coopetition

To argue for the importance of trust in coopetition, a lot of the studies included in this review refer to a book chapter (Castaldo & Dagnino, Citation2009), which develops a conceptual model showing how trust and coopetition coevolve over time. Drawing upon the idea that trust transforms from one type to another depending on the maturity of a relationship (Lewicki & Bunker, Citation1995; Shapiro, Sheppard, & Cheraskin, Citation1992), Castaldo and Dagnino (Citation2009) suggest that trust and coopetition coevolve, and that different types of trust (i.e. calculus/deterrence-based, knowledge-based, and identification-based trust) are required during different stages of coopetition. They adopt the view that trust can be of three different types depending on what grounds trust is built and depending on the phase of the relationship. It is also argued that the development of trust can indicate changes in coopetition. When trust increases or decreases, the dominant type of trust that emerges is different, showing that the underlying dynamics of the interaction change. As the process evolves, more emphasis is placed on the social aspect (i.e. identification-based trust), in contrast to the initial stages where the economic logic is more prevailing (i.e. deterrence/calculative-based trust). The view that trust and coopetition coevolve, but different types of trust matter during different phases of coopetition is in line with the co-evolutionary research model suggested by Nielsen (Citation2011). The coevolution of trust and coopetition is a suggestion that remains to be studied empirically, which could also be expanded by discussing the role of distrust, which has been neglected.

To sum up, despite trust not being the main focus of many of the articles included in this review, it has been suggested and shown that trust plays a critical role in coopetition. Yet, more research is needed on this topic. In a considerable number of papers included in this review, trust is suggested as a relevant direction for further research. For instance, Fernandez and Chiambaretto (Citation2016), who study control mechanisms for managing tensions related to information in coopetition, highlight that studying the role of trust between individuals in the implementation of informal mechanisms to manage coopetition is a promising research avenue. Another interesting research direction is provided by Peters and Pressey (Citation2016), who call for more research on the role of trust in temporary organisations involving coopetition. That more research efforts are needed on trust in coopetition is also communicated by Czernek and Czakon (Citation2016) and Castaldo and Dagnino (Citation2009). With this in mind and based on the identified gaps and limitations of the studies on trust in the extant coopetition literature, we build a research agenda of six promising research avenues, which is presented in the next section.

5. An agenda for future research on the roles of trust and distrust in coopetition

5.1. Research avenue 1. Types and dimensions of trust and distrust and the relation between them in different coopetitive contexts

As trust is not a key focus of several of the coopetition papers included in this review, most of the papers do not draw on the extant literature on organisational trust in the way they define and treat the concept. A general pattern is that trust is treated as a psychological state neglecting that trust includes not only an assessment of the trustee’s trustworthiness, but also a decision to rely on another party (Li, Citation2017) under conditions of uncertainty and risks. To this end, this paper calls for more conceptual precision in relation to trust (i.e. clear definition, explicit statement of the type of trust, clear presentation of the level on which trust is studied) in coopetition studies. Also, future coopetition research could draw more upon the literature on trust in strategic alliances, for example in using and testing established measures and relationships (for a review on trust measures, see McEvily & Tortoriello, Citation2011), to see whether the nature of coopetition influences such relationships.

Furthermore, coopetition research needs to acknowledge the multidimensional nature of trust, by taking into account dimensions of trustworthiness such as ability, integrity (Mayer et al., Citation1995), predictability or reliability (Dietz & den Hartog, Citation2006). Trust can play different roles in different phases of coopetition and therefore, it is critical to consider types and dimensions of trust in different phases of coopetition. Similarly, these aspects need to be taken into consideration when trust is approached as a means for managing coopetition or as an outcome of coopetition. In addition, different types of coopetition (e.g. network-dyadic; vertical-horizontal) and differences in intensity of cooperation and competition in relation to trust and distrust may be important to consider. Also, the particularities of the business environment in which a dyadic relationship is embedded (e.g. speed of development and knowledge intensity of the industry) may make certain types of trust and/or distrust more important.

Moreover, more studies are needed to shed light on the conceptual relationship between trust and distrust (Guo et al., Citation2017) and this paper suggests that the very ‘both/and’ ontology of coopetition makes interorganizational relationships involving simultaneous cooperation and competition a particularly relevant arena for doing so. To expand the debate on whether trust and distrust are distinct or not (Lewicki et al., Citation1998; Schoorman et al., Citation2007), one could look, for example, at the antecedents and manifestations of trust and distrust in coopetition or the distinct and even complementary roles that each can play in different phases of coopetition. Corresponding to our call for considering different types and dimensions of trust in coopetitive interactions, we suggest that following the same is needed when studying the role of distrust in coopetition. In addition to this, a promising line of inquiry relates to how and why trust repair is different than distrust management in the context of coopetition.

5.2. Research avenue 2. Trust and distrust in the light of uncertainty and risks in coopetition

Risk and uncertainty are fundamental elements of trust, therefore a fruitful endeavour for research on coopetition would be to consider different dimensions and types of trust, and how these are linked to types of risks stemming from coopetition at different stages of a relationship. While risk is what has most commonly been discussed in relation to coopetition, we draw on research seeing uncertainty and risk as different, and call for further research addressing uncertainty in coopetition. This as uncertainty signifies that potentialities and probabilities thereof cannot always be predicted in an accurate manner, and cannot always be mitigated (Vilko, Ritala, & Edelmann, Citation2014). Following this idea, it could be argued that while a dimension of trust (e.g. benevolence) or type of trust (e.g. identification-based trust) may relate to a certain type of uncertainty (e.g. behavioural uncertainty), another may relate to a certain type of risk (e.g. performance risk). Thus, future research could link different types of uncertainties and risks with the multidimensional character of trust. In addition, a relevant question to pursue is whether trust and distrust matter differently for coping with different types of potentialities existing on different levels (i.e. behavioural, environmental, and interpretive uncertainty). For instance, Kostis and Näsholm (Citation2018) suggest that trust and distrust can synergistically support firms to embrace uncertainty by practicing watchful blindness.

5.3. Research avenue 3. Trust and distrust in the light of competing demands and tensions in coopetition

The third research direction proposed in this paper is associated with the importance of trust and distrust for managing competing demands stemming from the simultaneous pursuit of cooperation and competition. Looking at how trust and/or distrust influence the management of coopetition requires more precision in regards to the different types of competing demands stemming from simultaneous cooperation and competition. This since, prior research suggests that competing demands can be of different types (e.g. dilemma, trade-off, dialectic, duality, paradox) based on a number of distinguishing features that require different responses (Gaim, Wåhlin, Cunha, & Clegg, Citation2018). Drawing upon this, one could argue that depending on the type of the competing demands coopetitors face, the necessity of trust and/or distrust varies. A further examination of this issue could provide insights into how various types of competing demands can be managed and whether or how the associated effects of them can be prevented, reduced, or embraced due to the simultaneous existence of trust and distrust. As pointed out in coopetition research managing tensions and balancing competition and cooperation are key challenges in coopetition. By addressing trust and distrust in relation to different types of competing demands, additional insights into what constitutes the balancing act can be provided.

5.4. Research avenue 4. The dark side of trust and the bright side of distrust in coopetition

The normative view on trust is prevailing in almost all of the papers included in this review. According to this logic, trust is always positive, and more trust is always better. There are a couple of papers that underline the need to challenge this view, yet they go no further in discussing the repercussions of over-embeddedness of trust, nor the role of distrust in dealing with them. Considering the double-edged sword nature of coopetition and its ‘both/and’ philosophy (e.g. two-continuum approach), studying trust and distrust in coopetition from a non-normative perspective is particularly important. Compared to purely cooperative endeavours, this context is suitable for understanding how, when, and why trust can be detrimental and how, when, and why distrust can provide unique benefits. Thus, future research could delve into the relationship between trust and distrust as separate phenomena that coexist and influence each other along the course of a coopetitive arrangement and we encourage a particular focus on distrust.

Furthermore, coopetitive interactions are not always perceived the same way by both partners and this is why perceptions of trust may differ between partners. Although trust (and distrust) is shaped by both sides of a relationship, only one paper included in this literature review approaches coopetition from a dual perspective (de Araujo & Franco, Citation2017). To study both sides is important, especially due to the potential of trust asymmetry between the partners, an issue that future research could also investigate.

5.5. Research avenue 5. Coevolution of trust and distrust in both the cooperative and competitive arenas of coopetition

In coopetition, as the partners simultaneously cooperate and compete, trusting and distrusting may influence both the way firms and individuals exchange resources and knowledge in the cooperative arena, and the efforts of the firms to fulfil their own interests in the competitive arena. Whereas trust is often connected to cooperation, this paper suggests that different dimensions and/or types of trust can also facilitate or constrain competition. Similarly, distrust may be relevant not only for firms to remain competitors, but also to achieve cooperative efforts. In other words, future research on trust in coopetition could investigate the complex linkages between trust, distrust, and the two inextricably linked elements of coopetition. As proposed by Castaldo and Dagnino (Citation2009), trust can be utilised in order to understand how coopetition changes over time, yet empirical investigation is needed and we suggest that complementing this with distrust can be even more fruitful.

5.6. Research avenue 6. Trust, distrust and the microfoundations of coopetition

Studying (dis)trust, an inherently individual-level phenomenon, which can diffuse within and across organisations, can be a valuable lens for understanding the role of individuals’ perceptions, actions and interactions in coopetition. Considering that there is a need to understand how the different levels of coopetition interrelate (Raza-Ullah, Bengtsson, & Kock, Citation2014), this paper supports the view that ‘future research should seek to more thoroughly address the antecedents, dynamics and consequences of [dis]trust within coopetitive relationships on all levels of analysis’ (Dorn et al., Citation2016, p. 12). By addressing this call, deeper insights into the microfoundations of coopetition can be provided and linkages between different levels of coopetition can be identified. As trust is cultivated at the individual-level, yet develops at group and interorganizational levels, it may influence and be influenced by aspects situated at different levels of coopetition. The walk in this path can be supported by gaining insights from bodies of literature focusing on mixed-motive interactions, as in social dilemmas (Balliet, Citation2010; Balliet & Van Lange, Citation2013), in negotiation processes (Druckman, Lewicki, & Doyle, Citation2019) or in interactions with increased interdependence (Gerpott, Balliet, Columbus, Molho, & de Vries, Citation2018). Further, future studies could investigate what mechanisms are at work in order for interpersonal (dis)trust to transform into interorganizational (dis)trust in different types of coopetition.

6. Concluding remarks

The purpose of this paper was to identify limitations and gaps in the extant literature on trust in coopetition, bring promising research opportunities into light, and create an agenda for future research focused on the roles of both trust and distrust in the simultaneous pursuit of cooperation and competition. The findings of our literature review establish that while trust ‘has become a central concept in explaining business behaviour’ (Bachmann & Inkpen, Citation2011, p. 281) and has been acknowledged as important for interorganizational interactions, it has received limited attention by coopetition scholars. Prior literature reviews on trust in strategic alliances (e.g. Nielsen, Citation2011), have mainly focused attention on how cooperation can be promoted in interorganizational relationships and have approached trust from a more normative point of view, as emphasis is placed on the beneficial role of trust in facilitating cooperative processes. Our literature review complements reviews on trust in cooperation and highlights that in the simultaneous presence of both cooperation and competition, trust is not only important for enabling processes related to cooperation (e.g. knowledge sharing), but also for dealing with contradictions and tensions entailed by coopetition (e.g. balancing knowledge sharing and knowledge protection). Our review takes the perspective that trust can also be detrimental for the maintenance of coopetitive interactions and that distrust is a distinct phenomenon which can interact with trust and lead to fruitful synergies in the face of challenges stemming from coopetition. Following this notion and building on the identified limitations and gaps, the proposed agenda includes six research avenues on the distinct roles of trust and distrust in coopetition ().

Table 5. Promising research avenues and key topics and questions.

To sum up, the agenda developed in this paper encourages coopetition researchers to pay closer attention to the underlying mechanisms through which trust and distrust enable and constrain coopetitive interactions at multiple levels. However, it also brings to the attention of trust scholars a unique context for studying trust and draw insights to avoid ‘either/or’ polarizations and adopt a ‘duality-rooted approach to trust’ (Li, Citation2017, p. 2). The research avenues suggested in this paper hopefully will encourage further research bridging interorganizational trust and coopetition research, thereby providing benefits for both literature streams.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Associate Editor Steven Lui and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and guidance in revising this paper. We are also thankful to Maria Bengtsson for her useful comments in earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributor

Angelos Kostis is a PhD Candidate in Entrepreneurship at Umeå School of Business, Economics and Statistics. His research interest lies in behavioural strategy and uncertainty in interorganisational relationships. He is currently doing research on the dynamics of trust and distrust and on the role of digital artefacts in the context of interorganisational relationships involving coopetition and interdependence. He has published in European Management Journal.

Harryson Näsholm is an Associate Professor in Management at Umeå School of Business, Economics, and Statistics, Sweden. Her research interest lies mainly in individuals' experiences of alternative careers and forms of organising. She is currently doing research on coopetition and interorganisational relationships, and on the influence of individuals and their experiences. She has published in journals such as Long Range Planning, Industrial Marketing Management, and Journal of Business Environment.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akrout, H. (2015). A process perspective on trust in buyer–supplier relationships. “calculus” An intrinsic component of trust evolution. European Business Review, 27(1), 17–33.

- Ansari, S., Garud, R., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2016). The disruptor's dilemma: TiVo and the US television ecosystem. Strategic Management Journal, 37(9), 1829–1853.

- Bachmann, R., & Inkpen, A. C. (2011). Understanding Institutional-based trust building processes in inter-organizational relationships. Organization Studies, 32(2), 281–301.

- Balliet, D. (2010). Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54(1), 39–57.

- Balliet, D., & Van Lange, P. A. (2013). Trust, punishment, and cooperation across 18 societies: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(4), 363–379.

- Baruch, Y., & Lin, C. P. (2012). All for one, one for all: Coopetition and virtual team performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(6), 1155–1168.

- Bengtsson, M., Eriksson, J., & Wincent, J. (2010). Co-opetition dynamics-an outline for further inquiry. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 20(2), 194–214.

- Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2000). Coopetition in business networks—to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

- Bengtsson, M., & Raza-Ullah, T. (2016). A systematic review of research on coopetition: Toward a multilevel understanding. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 23–39.

- Bijlsma-Frankema, K., Sitkin, S. B., & Weibel, A. (2015). Distrust in the balance: The emergence and development of intergroup distrust in a court of law. Organization Science, 26(4), 1018–1039.

- Bouncken, R. B., Clauß, T., & Fredrich, V. (2016). Product innovation through coopetition in alliances: Singular or plural governance? Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 77–90.

- Bouncken, R. B., & Fredrich, V. (2012). Coopetition: Performance implications and management antecedents. International Journal of Innovation Management, 16(5), 1–28.

- Bouncken, R. B., Gast, J., Kraus, S., & Bogers, M. (2015). Coopetition: A systematic review, synthesis, and future research directions. Review of Managerial Science, 9(3), 577–601.

- Brandenburger, A., & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-opetition. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Castaldo, S., & Dagnino, G. B. (2009). Trust and coopetition: The strategic role of trust in interfirm coopetitive dynamics. In G. B. Dagnino, & E. Rocco (Eds.), Coopetition strategy (pp. 94–120). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Chiambaretto, P., & Dumez, H. (2016). Toward a typology of coopetition: A multilevel approach. International Studies of Management & Organization, 46(2-3), 110–129.

- Chiambaretto, P., Massé, D., & Mirc, N. (2019). All for one and one for all?”-knowledge broker roles in managing tensions of internal coopetition: The ubisoft case. Research Policy, 48(3), 584–600.

- Chim-Miki, A. F., & Batista-Canino, R. M. (2017). Partnering based on coopetition in the interorganizational networks of tourism: A comparison between Curitiba and Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil. Revista brasileira de gestão de negócios, 19(64), 219–235.

- Chin, K. S., Chan, B. L., & Lam, P. K. (2008). Identifying and prioritizing critical success factors for coopetition strategy. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 108(4), 437–454.

- Cho, J. (2006). The mechanism of trust and distrust formation and their relational outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 82(1), 25–35.

- Claro, D. P., Hagelaar, G., & Omta, O. (2003). The determinants of relational governance and performance: How to manage business relationships? Industrial Marketing Management, 32(8), 703–716.

- Connelly, B. L., Miller, T., & Devers, C. E. (2012). Under a cloud of suspicion: Trust, distrust, and their interactive effect in interorganizational contracting. Strategic Management Journal, 33(7), 820–833.

- Crick, J. M. (2019). Moderators affecting the relationship between coopetition and company performance. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 34(2), 518–531.

- Crossan, M. M., & Apaydin, M. (2010). A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1154–1191.

- Currall, S. C., & Inkpen, A. C. (2002). A multilevel approach to trust in joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3), 479–495.

- Currall, S. C., & Inkpen, A. C. (2006). On the complexity of organizational trust: A multi-level co-evolutionary perspective and guidelines for future research. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 235–246). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Cusin, J., & Loubaresse, E. (2018). Inter-cluster relations in a coopetition context: The case of Inno'vin. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 30(1), 27–52.

- Czakon, W., & Czernek, K. (2016). The role of trust-building mechanisms in entering into network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 64–74.

- Czernek, K., & Czakon, W. (2016). Trust-building processes in tourist coopetition: The case of a Polish region. Tourism Management, 52, 380–394.

- Dahl, J., Kock, S., & Lundgren-Henriksson, E. L. (2016). Conceptualizing coopetition strategy as practice: A multilevel interpretative framework. International Studies of Management & Organization, 46(2-3), 94–109.

- Damayanti, M., Scott, N., & Ruhanen, L. (2018). Space for the informal tourism economy. The Service Industries Journal, 38(11-12), 772–788.

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (1998). Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 491–512.

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (2000). Instabilities of strategic alliances: An internal tensions perspective. Organization Science, 11(1), 77–101.

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (2004). The risk-based view of trust: A conceptual framework. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(1), 85–116.

- de Araujo, D. v. B., & Franco, M. (2017). Trust-building mechanisms in a coopetition relationship: A case study design. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(3), 378–394.

- Della Corte, V., & Aria, M. (2016). Coopetition and sustainable competitive advantage. The Case of Tourist Destinations. Tourism Management, 54, 524–540.

- Dietz, G. (2011). Going back to the source: Why do people trust each other? Journal of Trust Research, 1(2), 215–222.

- Dietz, G., & den Hartog, D. N. (2006). Measuring trust inside organisations. Personnel Review, 35(5), 557–588.

- Dimoka, A. (2010). What does the brain tell us about trust and distrust? Evidence from a functional neuroimaging study. MIS Quarterly, 34(2), 373–396.

- Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2001). The role of trust in organizational settings. Organization Science, 12(4), 450–467.

- Dorn, S., Schweiger, B., & Albers, S. (2016). Levels, phases and themes of coopetition: A systematic literature review and research agenda. European Management Journal, 34(5), 484–500.

- Druckman, D., Lewicki, R. J., & Doyle, S. P. (2019). Repairing violations of trustworthiness in negotiation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(3), 145–158.

- Dyer, J. H., & Chu, W. (2003). The role of trustworthiness in reducing transaction costs and improving performance: Empirical evidence from the United States. Japan, and Korea. Organization Science, 14(1), 57–68.

- Engelke, K. M., Hase, V., & Wintterlin, F. (2019). On measuring trust and distrust in journalism: Reflection of the status quo and suggestions for the road ahead. Journal of Trust Research, 9(1), 66–86.

- Eriksson, P. E. (2008). Achieving suitable coopetition in buyer–supplier relationships: The case of AstraZeneca. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 15(4), 425–454.

- Fernandez, A. S., & Chiambaretto, P. (2016). Managing tensions related to information in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 66–76.

- Flick, U. (2009). An Introduction to Qualitative research methods. London: Sage Publications.

- Fulmer, A., & Dirks, K. (2018). Multilevel trust: A theoretical and practical imperative. Journal of Trust Research, 8(2), 137–141.

- Gaim, M., Wåhlin, N., Cunha, M. P., & Clegg, S. (2018). Analyzing competing demands in organizations: A systematic comparison. Journal of Organization Design, 7, 1.

- Gerpott, F. H., Balliet, D., Columbus, S., Molho, C., & de Vries, R. E. (2018). How do people think about interdependence? A multidimensional model of subjective outcome interdependence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(4), 716–742.

- Gnyawali, D. R., & Park, B. J. (2011). Co-opetition between giants: Collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 650–663.

- Grafton, J., & Mundy, J. (2016). Relational contracting and the myth of trust: Control in a co-opetitive setting. Management Accounting Research, 36, 24–42.

- Gulati, R. (1995). Social structure and alliance formation patterns: A longitudinal analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(4), 619–652.

- Guo, S. L., Lumineau, F., & Lewicki, R. J. (2017). Revisiting the foundations of organizational distrust. Foundations and Trends in Management, 1(1), 1–88.

- Huang, H. C., & Chu, W. (2015). Antecedents and consequences of co-opetition strategies in small and medium-sized accounting agencies. Journal of Management & Organization, 21(6), 812–834.

- Idrees, I. A., Vasconcelos, A. C., & Ellis, D. (2018). Clique and elite: Inter-organizational knowledge sharing across five star hotels in the Saudi Arabian religious tourism and hospitality industry. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(6), 1358–1378.

- Komiak, S. Y., & Benbasat, I. (2008). A two-process view of trust and distrust building in recommendation agents: A process-tracing study. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 9(12), 727–747.

- Kostis, A., & Näsholm, H. M. (2018). Balancing trust and distrust in strategic alliances. In T. K. Das (Ed.), Managing trust in strategic alliances (pp. 103–127). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Kraus, S., Klimas, P., Gast, J., & Stephan, T. (2019). Sleeping with competitors: Forms, antecedents and outcomes of coopetition of small and medium-sized craft beer breweries. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(1), 50–66.

- Krishnan, R., Martin, X., & Noorderhaven, N. G. (2006). When does trust matter to alliance performance? Academy of Management Journal, 49(5), 894–917.

- Latusek, D., & Vlaar, P. W. (2018). Uncertainty in interorganizational collaboration and the dynamics of trust: A qualitative study. European Management Journal, 36(1), 12–27.

- Le Roy, F., & Fernandez, A. S. (2015). Managing coopetitive tensions at the working-group level: The rise of the coopetitive project team. British Journal of Management, 26(4), 671–688.

- Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1995). Trust in relationships: A model of development and decline. In B. B. Bunker, J. Z. Rubin & Associates (Eds.), Conflict, cooperation and justice: Essays inspired by the work of Morton Deutsch (pp. 133–173). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 438–458.

- Li, P. P. (2012). When trust matters the most: The imperatives for contextualising trust research. Journal of Trust Research, 2(2), 101–106.

- Li, P. P. (2017). The time for transition: Future trust research. Journal of Trust Research, 7(1), 1–14.

- Lumineau, F. (2017). How contracts influence trust and distrust. Journal of Management, 43(5), 1553–1577.

- Luo, Y. (2007). A coopetition perspective of global competition. Journal of World Business, 42(2), 129–144.

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

- McEvily, B., Perrone, V., & Zaheer, A. (2003). Trust as an organizing principle. Organization Science, 14(1), 91–103.

- McEvily, B., & Tortoriello, M. (2011). Measuring trust in organisational research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Trust Research, 1(1), 23–63.

- McEvily, B., & Zaheer, A. (2005). Does trust still matter? Research on the role of trust in interorganizational exchange. In R. Bachman, & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 280–300). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. L. (2001). Trust and distrust definitions: One bite at a time. In R. Falcone, P. S. Munindar, & Y. H. Tan (Eds.), Trust in cyber-societies (pp. 27–54). Berlin: Springer.

- Möllering, G. (2001). The nature of trust: From Georg Simmel to a theory of expectation, interpretation and suspension. Sociology, 35(2), 403–420.

- Morris, M. H., Koçak, A., & Özer, A. (2007). Coopetition as a small business strategy: Implications for performance. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 18(1), 35.

- Näsholm, M. H., & Bengtsson, M. (2014). A conceptual model of individual identifications in the context of coopetition. International Journal of Business Environment, 6(1), 13–14.

- Näsholm, M. H., Bengtsson, M., & Johansson, M. (2018). Coopetition for SMEs (1ed.). In A. S. Fernandez, P. Chiambaretto, F. Le Roy, & W. Czakon (Eds.), The Routledge companion to coopetition strategies (pp. 390–397). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nielsen, B. B. (2011). Trust in strategic alliances: Toward a co-evolutionary research model. Journal of Trust Research, 1(2), 159–176.

- Nielsen, B. B., & Nielsen, S. (2009). Learning and innovation in international strategic alliances: An empirical test of the role of trust and tacitness. Journal of Management Studies, 46(6), 1031–1056.

- Osarenkhoe, A. (2010). A study of inter-firm dynamics between competition and cooperation– A coopetition strategy. Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 17(3-4), 201–221.

- Ou, C. X., & Sia, C. L. (2010). Consumer trust and distrust: An issue of website design. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 68(12), 913–934.

- Padula, G., & Dagnino, G. B. (2007). Untangling the rise of coopetition: The intrusion of competition in a cooperative game structure. International Studies of Management and Organization, 37(2), 32–52.

- Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2008). The decision to persist with underperforming alliances: The role of trust and control. Journal of Management Studies, 45(7), 1217–1243.

- Peters, L. D., & Pressey, A. D. (2016). The co-ordinative practices of temporary organisations. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 31(2), 301–311.

- Poppo, L., & Zenger, T. (2002). Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strategic Management Journal, 23(8), 707–725.

- Porto Gomez, I., Otegi Olaso, J. R., & Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M. (2016). Trust builders as open innovation intermediaries. Innovation, 18(2), 145–163.

- Pressey, A. D., & Vanharanta, M. (2016). Dark network tensions and illicit forbearance: Exploring paradox and instability in illegal cartels. Industrial Marketing Management, 55, 35–49.

- Pressey, A. D., Vanharanta, M., & Gilchrist, A. J. (2014). Towards a typology of collusive industrial networks: Dark and shadow networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(8), 1435–1450.

- Ratzmann, M., Gudergan, S. P., & Bouncken, R. (2016). Capturing heterogeneity and PLS-SEM prediction ability: Alliance governance and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 4593–4603.

- Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 189–198.

- Ritala, P., & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2009). What's in it for me? Creating and appropriating value in innovation-related coopetition. Technovation, 29(12), 819–828.

- Ritala, P., & Sainio, L. M. (2014). Coopetition for radical innovation: Technology, market and business-model perspectives. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 26(2), 155–169.

- Robson, M. J., Katsikeas, C. S., & Bello, D. C. (2008). Drivers and performance outcomes of trust in international strategic alliances: The role of organizational complexity. Organization Science, 19(4), 647–665.

- Saunders, M. N., Dietz, G., & Thornhill, A. (2014). Trust and distrust: Polar opposites, or independent but co-existing? Human Relations, 67(6), 639–665.

- Schilke, O., & Cook, K. S. (2013). A cross-level process theory of trust development in interorganizational relationships. Strategic Organization, 11(2), 281–303.

- Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2007). An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 344–354.

- Shapiro, D. L., Sheppard, B. H., & Cheraskin, L. (1992). Business on a handshake. Negotiation Journal, 8(4), 365–377.

- Skinner, D., Dietz, G., & Weibel, A. (2014). The dark side of trust: When trust becomes a ‘poisoned chalice’. Organization, 21(2), 206–224.

- Thomason, S. J., Simendinger, E., & Kiernan, D. (2013). Several determinants of successful coopetition in small business. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 26(1), 15–28.

- Tidström, A. (2014). Managing tensions in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 261–271.

- Vanneste, B. S. (2016). From interpersonal to interorganisational trust: The role of indirect reciprocity. Journal of Trust Research, 6(1), 7–36.

- Vilko, J., Ritala, P., & Edelmann, J. (2014). On uncertainty in supply chain risk management. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 25(1), 3–19.

- Walley, K. (2007). Coopetition: An introduction to the subject and an agenda for research. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 11–31.

- Wassmer, U. (2010). Alliance portfolios: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 36(1), 141–171.

- Wiesmann, B., Snoei, J. R., Hilletofth, P., & Eriksson, D. (2017). Drivers and barriers to reshoring: A literature review on offshoring in reverse. European Business Review, 29(1), 15–42.

- Wilhelm, M., & Sydow, J. (2018). Managing coopetition in supplier networks–a paradox perspective. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 54(2), 22–41.

- Zaheer, A., McEvily, B., & Perrone, V. (1998). Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organization Science, 9(2), 141–159.