ABSTRACT

The purpose of the current paper is to examine the development in the nature of followers’ trust in the leader during funding reform oriented organisational changes in a higher education organisation (HEO). Funding systems of HEOs are subjects of public reform. This development has pushed the organisations towards more business-oriented management and organisational culture and has created a demand for the communication of the leadership to maintain followers’ trust towards the leader and the organisation. The focus of this study is on the receiving end of this leader communication. Prior studies show that trust has a significant meaning in organisational contexts in strengthening members’ willingness to work towards mutual goals, interact with other members, and reduce self-protecting behaviour. The data of this qualitative case study comprises primary data consisting of followers’ texts and complementary data of a job satisfaction survey. The data was analysed using typology, which provided the basis for creating a metaphor for the findings. The findings suggest that during times of change in an organisational environment, the nature of followers’ trust in the leader seems to develop from an interpersonal level to an institutional level.

Introduction

The focus of this study is on the receiving end of leader communication. More precisely, the focus is on the perceptions, feelings and understanding followers have of leader communication during organisational funding reform and how followers’ trust in the leader develops in this process. Empirically, the process of the development of the nature of followers’ trust in the leader is also in the scope of the study. Trust in a crisis is also a crisis of trust (Möllering, Citation2013, p. 299). In a crisis, in this case an unexpected funding reform, the meaning of an organisation’s ability to function and keep the followers engaged, is central. From an organisational perspective, prior studies have repeatedly shown that trust has significant meaning in organisational contexts as it strengthens members’ willingness to work towards mutual goals, interact with other members, and reduce self-protecting behaviour (e.g. Burke et al., Citation2007; Colquitt et al., Citation2007; Kramer, Citation1996; Tyler, Citation2003, p. 556). On the other hand, from the perspective of the followers of the organisation, financial difficulties, e.g. induced by a funding reform, cause a high risk of losing one’s job and livelihood. According to prior research, high-vulnerability, high-stakes and high-uncertainty situations seem to result in a conscious decision-making process of trusting (Li, Citation2012; Möllering, Citation2014; Schoorman et al., Citation2016; van Houwelingen et al., Citation2017).

The context of the study is HEOs during a historic funding reform (Kosonen et al., Citation2015; Salminen & Ylä-Anttila, Citation2010). In times of crisis, the eyes of the followers turn to the leader and, hence, the role of the leadership can be central to the survival of the organisation. Typically, organisational crises demand changes in the role of the leader while, at the same time, the operating ability of the organisation is under external pressure. Crises can have debilitating effects on vital processes in organisations, and in such disruptions, people may rely on their managers to cope (Gagné et al., Citation2020). While public funding is diminishing and the need for other sources of income is a matter of survival for HEOs, the legal forms of HEOs are also changing to resemble private entities traditionally used for business operations (Kuismanen & Spolander, Citation2012; Salminen & Ylä-Anttila, Citation2010). Private funding in HEOs comprises both donations and the commercialisation of research and education. The demand for expertise in business, such as marketing, productizing, and economic production of ‘goods and services,’ is evident. One can say a paradigm shift in higher education is underway.

The changes that seem to result from the above developments highlight the meaning of follower engagement and trust in the HEO. Therefore, the research question of the current study is: How does followers’ trust in the leader develop during a funding reform in an HEO? Our paper makes contributions to the theoretical discussion of development of the nature of trust during disruptions: the role of trust in the performance of an organisation during funding reform and, further, the development of the nature of trust during a high-vulnerability and high-stakes situation. The practical implication of our study is to benefit higher education management by providing a deepened understanding of how trust within an HEO develops during funding reform and how it reflects follower engagement with the HEO during financial crisis.

Conceptual foundation

Individual and organisational trustworthiness

Our focus is on intra-organisational trust: that is, employees’ trust in their employing organisation. Therefore, regarding the context of our study, we build our conceptual framework on the nature of trust, role-based trust, and voluntary deference. Expectancies regarding the trustworthiness of the other party emerge in a variety of trust definitions. Expectations in the definitions of trust are related to positive expectations of trustworthiness (Fulmer & Gelfand, Citation2012). Competence (ability), benevolence (goodwill), integrity (honesty), and predictability are often presented as dimensions of trustworthiness (Burke et al., Citation2007; Dietz & Den Hartog, Citation2006; Mayer et al., Citation1995). Ability, benevolence and integrity (hereafter ABI) are the immediate precursors of trust in the model of organisational trust, according to which several characteristics of both parties lead to trust (Mayer et al., Citation2011). In the model, the distinction between trust and trustworthiness is crucial as trustworthiness refers to the characteristics of the trustee (Mayer et al., Citation1995). Repeatedly throughout the prior literature, the trustee attributes on an interpersonal level are his or her perceived trustworthiness. Firstly, scholars explain that ability (competence) refers to the extent to which the trustee has knowledge and professional skills (Dietz, Citation2011). Secondly, benevolence and goodwill refer to the confidence that one’s wellbeing will be protected by the trustee (e.g. Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000), therefore, loyalty, caring, supportiveness, and openness may be included in the construct of benevolence (Mayer et al., Citation1995). Benevolence is defined as a desire for and sensitivity to concern for others and expressions of altruism (Krot & Lewicka, Citation2012). Thirdly, integrity refers to honesty, the character, and authenticity of the trustee (Dietz, Citation2011), in other words, to a congruence between what the parties say and what they do, although it may have numerous other meanings. Integrity is judged by previous behaviours, reputation, the similarity of values, and consistency between words and actions (Mayer et al., Citation1995), and refers to moral principles, including fairness, justice, consistency, and promise fulfilment (Colquitt et al., Citation2007). In conclusion, the ABI framework appears to encompass multidimensional and overlapping, yet differentiable, concepts.

Scholars have distinguished between trust and confidence, with the latter seen as more assumed and unquestioned, especially in cases where no alternative options are considered (Seligman, Citation1997). Typically, trust refers to interpersonal trust, whereas confidence is seen as more systematic, such as trust in institutions and abstract systems, where relationships between actors are indirect, systemic, and impersonal (Seligman, Citation1997). Impersonal, institutional and personalised sources of trust are distinguishable (Shapiro, Citation1987) along with reputation, third party testimonies (vs. rumours), and role-based assumptions as sources of trust within organisations (Dietz, Citation2011). The co-existence of institutional and interpersonal trust is recognised (Dietz, Citation2011). Drawing on the prior trust literature, the different effects, meanings, and consequences of trust can be iden-tified at different organisational levels due to the reciprocal nature of trust (Fulmer & Gelfand, Citation2012).

Lewicki and Bunker (Citation1996, pp. 119–123) suggest in their well-known model of trust in work-life relationships that the types of trust are linked in sequential iteration in which achievement of trust at one level enables the development of trust at the next level. The first level is called calculus-based trust, and it is based on the consistency of behaviour. The second type is knowledge-based trust, and it is grounded in behavioural predictability. Knowledge-based trust occurs when one has enough information about others to understand them and accurately predict their likely behaviour. The third type of trust is called identification-based trust and it is based on a complete empathy with the other party’s desires and intentions (Lewicki & Bunker, Citation1996).

Regarding the role of trust in contexts of crisis and uncertainty, trust in an organisation or institution that an individual is embedded in can work as a means of reducing perceived vulnerability (Dirks, Citation2006). Institutional trust is a concept considered alongside character-based trust in the leader: if followers lack confidence in the leader, trust in the organisation or the institution might increase their willingness to follow the leader despite a low level of trust in the leader’s character (Dirks, Citation2006). When institutional trust exists, individual parties of the relationship can develop trust without prior individual experiences of the safety of the institution (Bachmann, Citation2011); the institution has valued the trustworthiness of the other institution on behalf of the members for them to engage freely in trusting relationships. Organisational trustworthiness is affected and evaluated by accurate information, fair decisions and procedures, and open communication (Whitener et al., Citation1998). A situation of high uncertainty, such as diminishing funding that threatens jobs within an organisation, leads members to re-evaluate and refigure their trust towards the employing organisation. Trust-as-choice (Li, Citation2012; Li, Citation2017) or active trust (Gustafsson et al., Citation2021) under high uncertainty, high vulnerability and high stakes require a ‘leap of faith’ (Möllering, Citation2006) that falls outside the comfort zone into the discomfort zone of the trustor, which can be overcome by making a hard choice or decision (Li, Citation2012). In this sense, trust-as-choice captures the true nature of trust in terms of a leap of faith, rather than confidence that does not require such a leap of faith (Li, Citation2012).

Within the ABI framework, whilst ability and integrity are related to cognitive aspects of trust, benevolence is recognised as an affect-based aspect of trust (Colquitt et al., Citation2007; Mayer et al., Citation1995; McAllister, Citation1995). Ability and competence refer to the extent to which the trustee has knowledge and skill (Dietz, Citation2011). Therefore, in work relationships trust is typically based on competence as a dimension of trustworthiness. In this study, we focus on cognitive aspects of trustworthiness while studying followers’ perceptions of leader communication. A leader’s behaviour according to his official role in the organisation is recognised as a cognition-based form of trust, since it is evaluated more by the followers’ heads instead of hearts (Tomlinson et al., Citation2020). Our study adopts this paradigm.

Role-based trust

Role-based trust has characteristics of a multiple-level phenomenon. In this paper, we rely on Kramer’s (Citation1999) proposal that role-based trust constitutes a form of depersonalised trust because it is predicated on the knowledge that a person occupies a role in the organisation rather than specific knowledge about the person’s capabilities, dispositions, motives, and intentions. It is shown that people within an organisation have confidence in the fact that role occupancy signals both an intent to fulfil any fiduciary responsibilities and obligations related to the role and also the competence to carry them out; individuals can adopt a sort of presumptive trust based upon knowledge of relations (Kramer, Citation1999). He states that this can result even without personalised knowledge or history of prior interaction.

The reasons for role-based trust occurring are common knowledge and presumptions with respect to how organisational roles are entered. Kramer (Citation1999) continues that depending on the role there can be significant barriers to entry to the role and specific training is usually expected. The higher the role in the hierarchy of the organisation, the more perceptions of accountability and responsibility are connected to the role (Kramer, Citation1999). Kramer (Citation1999) proposes that roles function to reduce uncertainty regarding the role occupant’s trust-related intentions and capabilities; therefore, roles can reduce the need and cost of negotiating trust when interacting with others and can facilitate unilateral acts of cooperation and coordination, even when other dimensions usually connected to trust are missing. Therefore, organisational crisis and reforms might be fatal to role-based trust as it is quite a fragile form of trust. Dietz (Citation2011) brings the meaning of context to role-based trust, stating that we may trust someone because of contextual factors that make the evaluation of trustworthiness more predictable. The shared context is found to be a source of trust in several theories (Korsgaard et al., Citation2015; Kramer, Citation1999; Mishra & Mishra, Citation1994; Tyler et al., Citation1996; Zaheer & Kamal, Citation2011) whether it is organisational membership, national surroundings, or other kinds of a social community. The role is always held by a person and in this context role-based trust should be analysed as an interpersonal trust relationship. However, the role is usually something that ‘belongs’ or is closely related to an organisation, so in this context role-based trust would be a trust relationship between a follower and the organisation.

The context of this study, a financial crisis of an HEO, results in a high-vulnerability situation for the followers. According to prior research, in such situations, trusting behaviour seems to take depersonalised forms (Li, Citation2012, Citation2017; Möllering, Citation2014; Schoorman et al., Citation2016). The focus of our study is on the perceptions, feelings and understanding followers have of leader communication during this high-uncertainty time and how the leader is performing in the role they hold. Further, in the context of our study, the role of the leadership is crucial to the performance and mere survival of the organisation. According to Yang et al. (Citation2020), it seems that leader communication that is assertive, clear, and supportive has a significant positive effect on trust, and verbal aggressiveness has a significant negative effect on follower trust. Newman et al. Citation2020) found a positive relationship between followers’ perceptions of leaders’ effective use of communications and followers’ perception of their unit’s performance. Further, the study also found that trust strengthens the relationship between perceived leader communication effectiveness and team performance results (Newman et al., Citation2020).

Voluntary deference

Voluntary deference is defined as acquiescing to additional requests (van der Toorn et al. Citation2011). Kramer (Citation1999) proposes that efficient organisational performance depends on individuals’ feelings of obligation toward the organisation, their willingness to comply with its directives and regulations, and their willingness to voluntarily defer to organisational authorities. Dependence on an authority leads people to trust in the authority and to give him or her greater discretion in making the decisions, furthermore, it leads to a feeling of personal responsibility to defer to the decisions the authority makes and to actual deference to requests of the authority (van der Toorn et al., Citation2011).

This is because it would be costly and impractical for organisational authorities, such as the knowledge-based education organisation in this study, to spend their time monitoring and reflecting on performance or justifying all of their actions to the members of the organisation (Kramer, Citation1999). In this study, we focus on leader communication during a financial crisis, which can be anticipated as negative from the follower perspective. During major organisational change members re-evaluate the organisation’s trustworthiness and hence their engagement with the organisation (Kahn, Citation1990; Whitener et al., Citation1998). The meaning of interactional justice is highlighted when the outcome of leader communication is anticipated to be negative, significant, and unexpected; the recipients of the news, the followers, accept the news and are more satisfied with the outcomes when the message is delivered with leader interactional fairness (Patient & Skarlicki, Citation2010, p. 556).

Although prior studies on interactional justice imply that, from the perspective of informational justice, followers’ perceptions of fairness depend on whether they receive an adequate explanation for decisions that affect them (O’Reilly et al., Citation2015, p. 172), it has also been shown that people are more likely to accept even unfavourable outcomes if they trust the authority’s motives and intentions. For example, fairness, availability and promise fulfilment are connected to judgments of an authority’s trustworthiness (Kramer, Citation1999).

The uniting features of the trustworthiness attributes of organisational authorities are good intentions, fairness, and ability or competence to perform the role (Kramer, Citation1999). Kramer (Citation1999) states that the meaning of trust is more central when the outcome of the authority’s actions is unfavourable to the followers, as people seem to need to believe that the authority makes fair decisions even when the outcomes are not what they hoped for. In this kind of situation, individuals’ commitment to the organisation and/or the authority must be strong enough to be able to perceive an organisational benefit from the outcome, rather than focusing on individual benefit (Kramer, Citation1999).

Perceptions of authorities as legitimate lead people to voluntarily accept and obey decisions from these authorities (Tyler, Citation2003). The underlying motivation for followers’ voluntary deference to authorities involves relational judgments about their treatment by these authorities (Tyler, Citation1997). Legitimacy is usually operationalised not only in terms of trust and confidence, but also in terms of deference to and empowerment of authorities (van der Toorn et al., Citation2011). It seems that when judging the legitimacy of authorities, people care more about integrity than they do about competence (Tyler, Citation1997). In his relational model, Tyler (Citation1997) lists trustworthiness, interpersonal respect, and neutrality as the most important aspects of the implementation of problem-solving approaches in organisational actions and further states that there can be a substantial variety of substantive outcomes. Evaluation of the authorities’ trustworthiness leads to followers’ willingness to defer to the authorities; neutrality, trusted motives and respectful treatment of followers are interpreted as benevolence. The enactment of benevolence is suggested by Patient and Skarlicki (Citation2010, p. 573) who encourage leaders to take the recipients’ perspective while delivering negative news and to imagine how the unwelcome news can affect the employees’ lives. Followers’ identification with the group(s) that the authority represents seems to strengthen their willingness to defer to the authority: people internalise group values, and this leads to voluntarily following the decisions of group authorities (Patient & Skarlicki, Citation2010).

Voluntary deference refers to voluntarily complying with an individual’s wishes, desires and suggestions; compliance without threat or coercion (Anderson, Citation2015, p.575). Anderson and colleagues (2015) refer to Blau (Citation1964), who states that, ‘To earn the deference as well as the respect of others, it is not enough for an individual to impress them with his outstanding qualities; he must use these abilities for their benefit’ (p. 162). This underscores the aspect of benevolence, which we consider a key dimension of trustworthiness.

Within a university faculty, cooperation has a different meaning to within a traditional professional organisation (Graso et al., Citation2014). Faculty members traditionally have highly or completely independent job descriptions. Interdependence between faculty members in a university organisation is considerably lower than in, e.g. a team organisation (Graso et al., Citation2014). The professional outcomes of individual faculty members are usually independent of the research and teaching success of other faculty members. There is less need for cooperation between peers, which can result in faculty members being distrustful of others and highly protective of their work and, consequently, to minimal voluntary exchange of knowledge and information. However, cooperation in the form of following organisational procedures is vital for the performance of educational organisations, since through transparency and uniform ways of action, fairness and equality are guaranteed for the students. The independent nature of faculty members’ roles could pose a challenge to what could be called organisational cooperation, especially in times when budget cuts are inevitable and affect all faculty members. There might be resistance to cooperating against actions that aim for better efficiency (Graso et al., Citation2014).

In the light of these and other recognised faculty characteristics (Graso et al., Citation2014), the voluntary nature of followers in an HEO deferring to the authority of leaders and to organisational benefit could have a distinctive formation compared to members of more business-oriented organisations. Fairness perceptions of followers are socially constructed, and fairness expectations are fuelled by interpersonal observations and inferences (Van Houwelingen et al., Citation2017). Therefore, fairness enactment is seen as a result of a complex interplay of organisational factors, such as the behaviour of the leader and the variables of the physical environment (Van Houwelingen et al., Citation2017, 340). HEOs are often physically divided into several locations, which could lead to mediated interaction between a leader and followers, mostly via email or other electronic channels of information.

To sum up the theoretical framework of the paper, we discuss followers’ trust perceptions at two levels: trust towards the leader as ‘a messenger’, and trust towards the organisation the leader is representing. At the interpersonal level, when communicating a situation of organisational change to stakeholders, the leader triggers among individual followers a trustworthiness evaluation of the leader in their role, as well as a trustworthiness evaluation of the organisation. At the organisational level, the followers evaluate their willingness to defer to the organisation’s authority and the terms of employment as well as to the terms of the organisational culture. Follower perceptions of trustworthiness are related to the willingness to defer to a work-related authority.

Empirical setting and methods

The empirical study follows a qualitative research strategy. The main approach of this research is a case study. Scholars (Eisenhardt, Citation1989, p. 534; Hartley, Citation2004, p. 323) suggest a case study as a research strategy when the aim is to understand the dynamics present within single settings. Yin (Citation2014) adds that case studies are rich, empirical instances of a phenomenon that are typically based on a variety of data sources. Higher education during a funding reform is the context in which the phenomenon of leader communication and followers’ trust in the leader is studied here and, for reasons of history, current state and easy research access, a Finnish University of Applied Sciences (UAS) was selected as a representative organisation within this context. We recognise our study as abductive research. Many researchers use both induction and deduction in different phases of their study, which means that you move iteratively between these two during the research process. Abduction refers to the process of moving from the everyday descriptions and meanings given by people to categories and concepts that create the basis of an understanding, or an explanation of the phenomenon described (Eriksson & Kovalainen, Citation2016).

Data collection

This study contains both primary and complementary data. The primary data was collected for this study and, to confirm and support the analysis, complementary data provided by the target organisation was added. The primary data of this study, consisting of 62 follower-written texts, was collected at staff meetings in the target organisation.

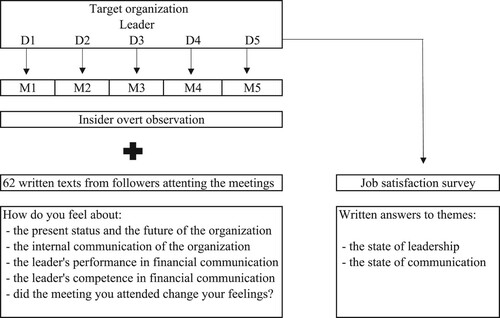

The target organisation is a Finnish University of Applied Sciences (UAS), and the insider observation by the first author was conducted in spring 2014 when the effects of the funding reform mentioned in the introduction had been happening for several years, but were still ongoing. The organisation was divided into five different administration divisions at the time of data collection, and the leader of the organisation (D1, D2, D3 … in the following ), the president, had the custom of visiting staff meetings in these divisions once a year. The first author was a member of the target organisation at the time of data collection and was granted a research permit by the leader to both observe and collect data at the staff meetings. The research permit included taking field notes of the meetings. All followers attending were told at the beginning of the meeting that the meeting was being observed for research purposes, who was the observer among them, and that they were going to be asked to write down their feelings at the end of the meeting anonymously. The divisions were separated from each other by administration, but also by location. Excluding this tour of the staff meetings (M1, M2, M3 … in the following ), most communication from the president to followers was in digital form, emails, a blog, newsletter, and sparse formal occasions with face-to-face communication. During this tour, the president gave speeches on the current state of the organisation, with almost identical content in all the meetings. In the speeches given at the data collection situations, the president described the financial situation in the target organisation as a battle, frequently using war analogies. Diminishing public funding and the authorities regulating it were narrated as an outside threat to the organisation, and the president strove to engage followers to join the battle for survival.

At the end of each of these meetings, the participating followers were asked to give written comments on eight topics. The topics concerned the president’s communication in the meeting and in the organisation more generally, their perception of the competence of the communicators of the organisation, and their perceptions of the organisation as an employer in the current situation and in the future. Altogether 62 followers reported their perceptions and feelings for this study. The field notes taken by the author focused on recording the emotional climate of the meeting after the leader’s speech on the financial situation.

Complementary data were provided by the target organisation. The complementary data provided support to the primary data findings, as the answers to the job satisfaction survey were given to the employer on similar topics as to the primary data. This allowed more depth in the analysis process. The target organisation carries out an employee satisfaction survey annually. The 2014 survey covers the same period that the primary data was collected. The employees, referred to as followers in this study, answered a questionnaire on several topics concerning the organisation and their work conditions. The followers were invited to give open answers to supplement their questionnaire answers for each topic. Open answers on the topic of leadership were used in this study as complementary data.

Data analysis

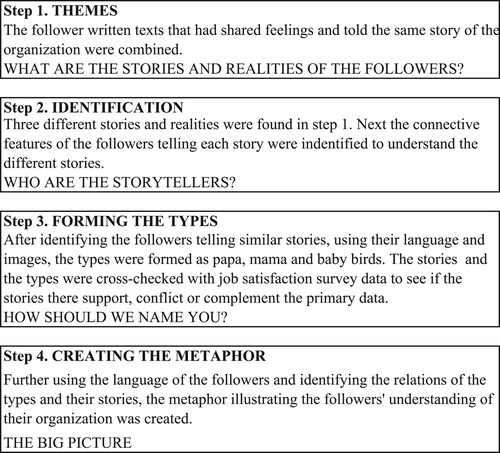

The primary and complementary data were analysed using the method of typology explained below to achieve the aim of deepening understanding of the followers’ perceptions of trust and feelings towards their leader and organisation. Typology was used as a basis for creating a metaphor that describes and interprets the results in their unique context.

In the data analysis process, a typological approach of generating overarching categories that include similarities in their underlying dimensions was used to classify units of study. Reiche et al. (Citation2017, p. 557) describe typology, as a method, as more than a remarkably straightforward means of classification, but as ‘conceptually derived, interrelated sets of ideal types, each of which constitutes a unique combination of attributes that will determine relevant outcomes’. This study aims to understand the perceptions of trust and the feelings followers have towards or related to their leader and the organisation in a unique context of higher education.

The typological analysis was conducted by first organising similar texts together under each topic. Topics were concerned with the leader’s communication in meetings and in the organisation more generally, the followers’ perceptions of the competence of the communicators of the organisation, and their perceptions of the organisation as an employer in the current situation and in the future. By similar, we refer to texts that told ‘the same story’ about each topic. Each text had the follower’s identifying information including sex, duration of employment in the target organisation (less than 5 years, 5–10 years, more than 10 years), main job function (faculty, administration or research, development, and innovation (RDI)), and the division where they attended the observed staff meeting.

After forming groups of similar comparable stories under each topic reported, the focus of the analysis turned to identifying the information in each group. Which followers are telling which side of the story? At the heart of the interpretive paradigm is the idea of a shared social reality that is formed and developed through reflection on the participants’ experiences. The followers’ perceptions of the situation in their organisation are the main interest of this study. The second step of the typology was to form the actual types of analysis. Bringing the similar features of the stories together shaped the followers into three diverse types that were identifiable in the responses given for each separate topic. The development of these types led to the creation of a metaphor that crystallized the results of this study in the case context.

Before the typology forming process, the complementary data was organised using qualitative content analysis. The data from the leadership topic of the survey were organised under themes formed based on the research question of this study: leader communication, the financial situation of the organisation, and trust. The complementary data was used with the observation field notes to cross-check the stories of the primary data for conflicting, complementing, or supporting information. The process of analysis is summarised in the following .

The use of metaphor in reporting the qualitative study

To crystallize the findings, we have chosen a metaphorical way of reporting the main findings in line with the qualitative, interpretative approach of the study. The most important building blocks of organisational theories are empirical data, theoretical concepts, and metaphors (Boxenbaum & Rouleau, Citation2011). Metaphors can convey surprising understanding of the topic under consideration. While metaphor represents a controversial component of organisational theories (Boxenbaum & Rouleau, Citation2011; Morgan, Citation1983), the importance of metaphor in both organisational theorising and everyday life is clear, providing a source of creativity and inspiring scholars to integrate metaphors with theoretical concepts (Boxenbaum & Rouleau, Citation2011; Tourish & Hargie, Citation2012).

The original meaning of the term metaphor, derived from the Greek ‘metapherein’, is transference (Merriam-Webster dictionary). A qualitative approach allows, and particularly recommends, metaphorical language for describing research findings. For example, Janesick (Citation2000) uses metaphor as a tool to surprise the reader. In reporting our findings, metaphors are utilised due to their innovative and generative powers (Boyd, Citation1993). For example, a metaphorical way of reporting has been recently adopted in trust research (Kosonen & Ikonen, Citation2019; Savolainen & Ikonen, Citation2016). At its best, a scientific metaphor generates new insight into conceptual development, providing more than a neutral depiction of a phenomenon (Knudsen, Citation2005; Tourish & Hargie, Citation2012). In fact, a good deal of our social reality is understood and explained in metaphorical terms (Tourish & Hargie, Citation2012). Therefore, the use of metaphors in scholarship is important for empirical analysis due to their ability to visualise organisational processes and phenomena from multiple perspectives, highlighting the heuristic quality of conceptualising (Cornelissen, Citation2005; Fleming, Citation2005; Savolainen & Ikonen, Citation2016). However, a metaphorical way of reporting the findings of a study has its weaknesses. The challenges of visualising are multiple. For example, on the one hand, while metaphorical illustrations can plainly point out the essential features of the studied phenomenon, its nuances may be obscured. On the other hand, metaphors can be a double-edged sword, since dominant metaphors can become a limitation or restriction, like ‘a prison, locking us into unquestioned forms of understanding and doing research’ (Alvesson, Citation2018). Nonetheless, researchers need to constantly question their own choices and assumptions and reflect on them as part of the research process (Eriksson & Kovalainen, Citation2016).

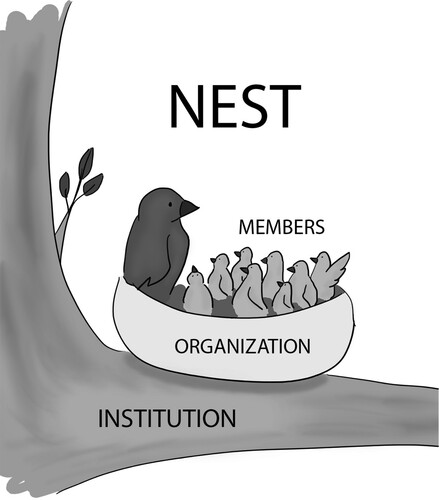

Key findings

This study aims to answer the question: How does followers’ trust develop during a funding reform in an HEO? The target organisation of this study was in a never-before-seen situation during data collection. The atmosphere was both anticipative and restless as the meaning of the funding reform began to unfold both nationwide and within the organisation. During the data collection, in both the observations and written texts the followers repeatedly referred to the president’s office as the ‘eagle’s nest’, and it seemed that all eyes were turned and all ears tuned to what ‘the nest’ and ‘the eagle’ would do in the situation at hand. Therefore, this analogy formed the basis for the metaphorical reporting of the results of this study.

The typological analysis focused on similar stories about the target organisation. Three types of storytellers were identified. The types were named, drawing on one of the follower’s quotes, as follows. The first group of storytellers reporting similar perceptions and feelings were identified as ‘mama birds’ and mainly represented female followers with long experience in the HEO, mainly in faculty or administration job functions. The mama birds group included faculty members from all disciplines, although the social services and health care disciplines were strongly represented. The second group, identified as ‘papa birds’, were mainly male followers with extensive experience in the target organisation and representing all three main job functions: faculty, administration and RDI. The ‘papa bird’ faculty members represented all disciplines, although engineering and business faculties were most represented. The third group identified through the stories were ‘baby birds’. Baby birds had less experience of the target organisation than the other birds and they represented all main job functions and both sexes. In the following analysis we present some example quotes from the data. The quotes have identifying information and were chosen for their representativeness of the story told per type.

Mama birds reported a rather pessimistic story of their organisation. They showed a great deal of criticism and doubt about the competence of the people responsible for the organisation, both the leader and the leaders below him responsible for communication. Mama birds seemed to have a neutral attitude towards the organisation as an employer and tended to consider higher education to have been a much more stable work environment prior to the funding reform. The mama birds are concerned about the future of the organisation:

‘It's a challenge [the future of the organization]. Management should guarantee opportunities for personnel development and training. A good result cannot be reached in the long run if faculty competence does not develop. The tightening of resources eats time from creativity and innovation.’ (Female, faculty, over 10 years in the target org., Social and Health Care)

‘The economy is tightening, which results as a decrease in resources and an increase in the load on work.’ (Female, faculty, over 10 years in the target org., Engineering and Business)

They have doubts about the leader’s competence to manage the organisation in the exceedingly difficult financial situation, which is seen as a major outside threat to the organisation as an employer. The financial information shared by the leader in the staff meeting raised negative thoughts and feelings among the mama birds, especially the way it was communicated and presented to the followers, for example:

‘Yes, we are led by fear, but we are starting to get used to it.’ (Female, faculty, 5–10 years in the target org., Culture and Arts)

Mama birds reported that the information shared with them at the staff meeting did not influence their previous perceptions and feelings towards the leader and the organisation, as described in the following excerpt:

‘Declaratory, a basic ‘heroic story’. Communicators feel self-confident that the listener is best placed to believe what is said. There is no room for discussion, no interaction, no respect is paid to the listeners. (Higher) education is not just a business, even if the financial review is meant to make it feel like a mere business.’ (Female, faculty, over 10 years in the target org., Social and Health Care)

The papa birds’ story of the organisation can be described as more neutral or hopeful. They reported the organisation to be a good employer and that they have confidence in its ability to stay that way in the future, even if the financial situation seems to raise concern:

‘[The target organization will] Continue as a regional educator and expert organization [in the future], either independent or allied. Interesting plans or visions under the current leadership. If the plans are implemented, they will strengthen the position of the organization.’ (Male, faculty, 5–10 years in the target org., Engineering and Business)

‘Predicting the future is difficult, but clearly, it is visible that the mid-decade years are still a struggle. The strong will survive and I believe [the target organization] is one of the strong ones. The world is changing and with it, we also have to change.’ (Male, administration, over 10 years in the target org., Engineering and Business)

The papa birds felt that the institution of HE in Finland is stronger than just one organisation’s struggle with budget cuts combined with the organisation’s status as a local developer:

‘I believe [the target organization] still exists even after five years, although age classes continue to decrease. However, political and educational situation nationally can change rapidly.’ (Male, administration, less than 5 years in the target org., Administration Services)

On the topic of the leader’s competence, the papa birds seemed to have a lack of trust, though they reported confidence in the persons responsible throughout the organisation; the organisation is believed to have the ability to choose the most qualified person for each position:

‘Sometimes, I am ashamed of the way management comes to present things — it's not professional.’ (Male, faculty, over 10 years in the target org., Engineering and Business)

‘At least between the lines, you could read that it had been understood how serious neglect in the financial management had been committed in the past, the childish escape behind the municipal section still (although [leader] was responsible for this destructive action). It is hoped that management will understand to better use the expertise within the organization.’ (Male, faculty, over 10 years in the org., Engineering and Business)

‘Most of the time, the actions of the top management do not insure me. [The target organization] is a big limited liability company that affects several stakeholders. If [the leader] acts ineptly and ill-advised, it will have significant implications.’ (Male, faculty, over 10 years in the org., Engineering and Business)

The financial information shared in the meeting stirred negative feelings among the papa birds. They reported that for them the leader is not a credible communicator of financial matters, and the information given raised concerns that not all consequences of the budget cuts had yet been seen:

‘It seems the management is in a complete panic. As an employee, I feel like the management gets entangled in the work of the subordinates even when they don’t know what their job description is.’ (Male, faculty, over 10 years in the target org., Engineering and Business)

Like the mama birds, the papa birds reported that the meeting and the interaction with the leader during it did not change their prior perceptions of the leader or the organisation.

The third group in this typology, identified as the ‘baby birds’, had less experience of the organisation than the other two groups with no distinctive gender. Baby birds told a positive and trusting story of their organisation. They have confidence in the people responsible for the organisation and the organisation's ability to function as a reliable employer. Baby birds reported that they feel the employer is caring:

‘A very caring [employer] and striving to keep our jobs — thanks the [leaders]!’ (Female, faculty, less than 5 years in the target org., Social and Health Care)

‘[The target organization] is a good and responsible employer. The salaries are paid when they are supposed to. The employer demonstrates responsibility for the well-being of employees.’ (Male, administration, less than 5 years in the target org., Administration Services)

Baby birds reported feeling doubt towards the leader as the representative of the organisation, even though the organisation is trusted by them to choose competent people for each role. Baby birds seemed to feel that the organisation’s future is positive:

‘I’m pleased and positively surprised by the nature of the employer, the [target] University of Applied Sciences, e.g. on issues of transparency, though a lot of changes and challenges are going on I think the way things are handled is good and there is constant development.’ (Female, faculty, less than 5 years in the target org., Social and Health Care, I)

The baby birds reported that the information about the financial situation shared at the meeting raised positive feelings and trust towards the organisation's ability to survive and thrive in the times to come, even if there are outside threats in the form of diminishing funding:

‘We seem to be in a cash crisis, but we’ll deal with it -> trust in leadership.’ (Female, faculty, less than 5 years in the target org., Social and Health Care, II)

As with the other groups, baby birds reported no change in their perceptions and feelings towards the organisation and the leader after communication and interaction with the leader at the meeting.

All the birds reported feeling a shared responsibility for the future of the organisation. There seems to be a mutual understanding that all members of the organisation need to participate in finding savings and tolerate the degradation of benefits for the common good. The common good was mentioned as saving as many jobs as possible and maintaining the organisation’s capability to function. The key findings are illustrated metaphorically as a shaking nest in .

Complementary data provided by the target organisation consisted of employees’ open responses to the yearly job satisfaction survey. The responses were given on the topic of leadership. This data had no identifying information other than the follower’s administrative division. Complementary data includes a basic statistical analysis of the general perceptions of followers answering the job satisfaction survey. This complementary data was first arranged using thematic analysis. According to the statistical data, the trend with respect to the leadership topic of the survey was positive compared to the previous year in three of the five administrative divisions of the target organisation. In the analysis, our interest was in the open answers that the followers gave in the survey to supplement their statistical answers.

Our analysis of both the primary and complementary data revealed that leaders at all levels of the organisation seemed distant and focused on leading matters, not people. Leader communication is reported by the followers to have improved but still be somewhat confusing, as are the actual actions of the leader. Followers found the leadership to be unpredictable and disorganised; however, they seemed to view the organisation's situation as exceptional and that it must have been exhausting for the leaders, especially in the lower levels of the organisation. Regarding communication and leader actions, the followers wished for improvement in openness, fair treatment, and an even distribution of work for employees, effective budgeting, and strategic leadership. A summary of the findings is presented in .

Table 1. Summary of the findings.

The features of role-based trust, organisational trust, and institutional trust can be identified in this study based on our primary data and validated by the complementary data. Our interpretation based on the analysis is that the leader of the organisation is perceived as distant and communication as confusing by the followers. In this challenging situation, the leader’s capability to function in his role is doubted; however, the followers reported trusting the organisation to have chosen the right person for the position. Kosonen and Ikonen (Citation2019) found that the leader’s ‘battle-talk’ way of communicating the difficult financial situation to the followers aims to strengthen followers’ trust and engagement in the organisation by illustrating the outside financial pressure as a mutual threat to the organisation that should be fought against together. Considering our data analysis, however, this can result in the opposite feeling among the followers. The leader’s dramatic war rhetoric concerning financial issues can be interpreted as leading by fear, as the mama birds reported. Feelings of fear or threat seem to result in a lack of trust in the communicator, the leader, but not towards the organisation, if the follower considers the organisation capable of surviving the financial difficulties. Role-based trust leaves out actual personal deep knowledge of the leader as a person and could be set at the level of calculus-based trust or knowledge-based trust as per the Lewicki and Bunker (Citation1996) model of trust development. Based on the data, it seems that role-based trust is a form of organisational trust. The organisation is trusted to have made the right choices when assigning people to positions. Further, the followers reported that despite their feelings towards the leader as being distant or even incompetent, the organisation is seen as caring, strong and a credible higher education operator that will survive the difficult financial situation. Hence, the ability, integrity, and benevolence, of the organisation are recognised in the data. When referring to the future, the followers do not mention the current leaders, but the organisation: the focus of the followers seems to move from personal level towards organisational or even institutional (future of higher education) level. The future of the target organisation lies in the national development in the policy of higher education.

Discussion and conclusions

Our paper makes contributions to the theoretical discussion of the nature of trust development during disruptions: followers’ trust seems to develop to an organisational or even institutional level, as trust towards the leader (role-based) seems to depersonalise during a high-vulnerability and high-stakes situation. Further, followers’ voluntary deference to the authority of the leader seems to follow firm role-based trust. The focus of this study is the perceptions, feelings and understanding followers have of leader communication during a funding reform and how followers’ trust develops during this process.

The contribution of our study indicates that when a public HEO is facing a serious financial situation, the leader performing his or her expected role through internal communication has a notable meaning for the followers’ trust towards the leader and the organisation. The analysis showed that during an urgent, unexpected funding reform of an HEO, followers experienced a lack of trust in the leader. For example, the followers interpreted the leader’s frequent ‘battle-talk’ during financial communication as leading with fear (Kosonen & Ikonen, Citation2019). What was intended as a victorious story of a war was perceived as a horror story. However, this did not seem to negatively impact trust towards the organisation as an employer, which the followers seemed to firmly trust despite the organisation facing severe changes in its operating condition. From the perspective of organisational justice, the enactment of fairness or justice in the form of delivering negative news seems to produce a lack of followers’ trust towards the leader. The messenger seems to ‘get shot’ in the process.

The key findings of this study suggest that followers differentiate between trust towards the organisation and towards the leader. Put metaphorically, the birds are willing to follow the eagle because they trust the nest and the branch beneath it to protect them. As a conclusion of the study, it seems that weak trust in the leader does not align with trust in the organisation. Interestingly, followers reported trusting the organisation’s capability to function currently and in the future despite the challenging or even threatening financial situation. In the light of our findings, during an unexpected funding reform, the nature of followers’ trust develops from interpersonal level trust to organisational and/or institutional level trust. This revealed that role-based trust seems to be a form of organisational trust. The followers’ trust in the organisation included the organisation’s ability to choose the most competent individuals for all roles. The findings of our study support prior literature on trust in high-vulnerability situations where trust can be seen to matter most (Li, Citation2012, Citation2017): follower trust takes depersonalised forms, and followers seem to choose to trust the organisation and the institution of HE. The followers seem to view the leader as acting in proper keeping with their role. The leader’s behaviour is perceived as fair and legitimate, which results in voluntary deference even though there may be a lack of trust towards the leader as a person. Hence, the followers tend to follow the leader and voluntarily defer to his or her leadership. Eventually, institutionalised, impersonal trust strengthens employees’ prospects in the organisation in the case where co-workers or supervisors cannot provide sufficient support for strong interpersonal trust to evolve (Vanhala et al., Citation2011). Being perceived as fair can have significant positive outcomes for leaders, such as promoting positive and mitigating negative behaviours in organisations, motivating followers, and enhancing relationships within the organisation (Barclay et al., Citation2017, p. 877).

These findings are congruent with the research by Malkamäki (Citation2017), who suggested that during an organisational paradigm-changing process the trust-building process develops towards an institutionalised form of trust at the organisation level. As discussed in the conceptual foundation of this study, institutionalised trust can become independent of the individuals engaged in the relationship (Bachmann, Citation2011; Kroeger, Citation2013); the way trust and trustworthiness are signalled can become transmittable across groups and generations of organisation members and, thus, the need to revaluate trust diminishes or vanishes. Our findings provide empirical support to the prior research. As a limitation, it seems that our findings on institutional trust are congruent throughout the data, yet without evidence of institutional trust being explicitly discussed within the target organisation.

In conclusion of our study, it seems that in a crisis, the performance of an organisation as assessed by the followers is more relevant to the development of the nature of trust than that of a leader as a person. The study illustrates the characteristics of the nature of trust development from the followers’ perspective and thereby increases the knowledge of the complex nature of organisational trust. It seems that followers’ trust in the leader and the organisation appears diffusive in nature due to the dynamics of the phenomenon, which leads us to investigate the dynamics and inter-relation of institutional and interpersonal levels of trust. The dynamics between impersonal and interpersonal trust seem to be multiple and diverse (cf. Atkinson & Butcher, Citation2003). Fundamentally, trust seems to develop simultaneously but differently depending on the levels, interaction, and time needed (Bormann & Thies, Citation2019; Savolainen & Ikonen, Citation2016; Shrivastava et al., Citation2018).

The context of our study, a higher education organisation, has gained little attention in prior trust research (Karhapää, Citation2016; Karhapää & Savolainen, Citation2018). Importantly, most research on trust building makes little reference to heightened vulnerability or disruption in the relationship (Gustafsson et al., Citation2021). The unique setting of this study, the target organisation facing funding reform, contributes to the conflicting theoretical discussions of research in higher education leadership and funding for higher education in Western countries. The practical implications or contextual contribution of this study are deepened understanding of intra-organisational nature of trust development during the funding reforms of HE and how this reflects the followers’ commitment to the HEO. Our aim is to mitigate and foster more trust-aware communication of financial difficulties by HEO leaders. In the light of our findings, it seems that leader communication that emphasises the stability of the nation-wide or even global institution of HE during turbulent financial and political times may strengthen employees’ commitment to their organisation.

By reporting our findings in the form of a metaphor we have precisely described the context of the study. In this context, actors are identified as forming the groups we have named birds. The findings contribute to a theoretical understanding of the development of the nature of trust at the individual level. The theoretical contribution to the development of the nature of trust is in line with Seligman (Citation2021). In the empirical context of our research, trust in a leader can be interpreted as a suspended judgement situation where trust emerges and develops based on experiences and embodied knowledge (Seligman, Citation2021). Due to leader communication in a high vulnerability situation, the followers’ shared experience and concrete, embodied knowledge seems to destabilise and discredit trust in the leader. However, at the organisational and institutional level trust in the leader is more system trust and confidence in nature. In the current context, also system trust is challenged due to uncertainty of future direction.

In our findings, with the mama birds, experiences and embodied knowledge are emphasised, whereas with the papa birds the nature of trust is more confidence directional, abstract and generalised. Most interestingly, the embodied knowledge of the baby birds seems to reinforce trust in the leader, while mama birds’ embodied knowledge destabilises trust in the leader.

A promising option for further research is to discuss and analyse the development and dynamics of multilevel trust in depth. As differing multi-level developments emerge, they seem to interrelate, enabling us to understand how organisational factors and relationships between actors are intertwined. The unanswered question of how interpersonal and institutional trust interrelates in the development and dynamics of trust at diverse levels is worthy of further investigation. Despite an increasing amount of empirical research on trust in diverse contexts, the dynamics and processes of multi-level trust remain largely unknown (Dirks & de Jong, Citation2022; Mishra & Mishra, Citation2013; Savolainen & Ikonen, Citation2016; Shrivastava et al., Citation2018). Regarding the contextual nature of trust, further research could be done in multiple contexts, in public, private business and education organisations, for example. This currently under-researched area of trust development needs to be considered more carefully and understood more thoroughly. More empirical qualitative studies are required to investigate processes of trusting, including both interpersonal and multilevel designs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Päivi Kosonen

Päivi Kosonen is a University Teacher and PhD candidate at UEF Business School. Her current research combines what she is most enthusiastic of: trust and elements of social interaction in organisational environments, financial accounting and higher education.

Mirjami Ikonen

Mirjami Ikonen, Ph.D., is a Senior Lecturer at the UEF Business School, University of Eastern Finland. Her primary research focus lies in organisational relationships and trust in leadership from process ontology perspective. Her current research interests include trust restoration, resilience, and learning perspectives.

Taina Savolainen

Taina Savolainen is Professor of Management & Leadership at the UEF, Business School where she leads the Research Group of ‘Trust within Organisations’. She is trust educator and trainer enhancing workplace trust-building skills. Prof Savolainen publishes actively on trust in academia (publications available http://uef.academia.edu/TainaSavolainen) and marketplace. The studies focus on trust-building and restoring trust in workplace relationships. Her focus is currently in a novel process approach in the trust research field. In the global Trust Alliance ‘Trust Across America-Trust Around the World’, she was named 100 Top Thought Leaders in Trust 2015 contributing also to three books of TRUST Inc.

References

- Alvesson, M. (2018). Metaphorizing the research process. In C. Cassell (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: Methods and Challenges (pp. 486–505). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526430236

- Anderson, J. E. (2015). The Economic Crisis and its Impact on Trust in Institutions in Transition Countries. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2652265

- Atkinson, S. & Butcher, D. (2003). Trust in Managerial Relationships. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(4), pp. 282-304.

- Bachmann, R. (2011). At the crossroads: Future directions in trust research. Journal of Trust Research, 1(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2011.603513

- Barclay, L. J., Bashshur, M. R., & Fortin, M. (2017). Motivated cognition and fairness: Insights, integration, and creating a path forward. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(6), 867–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000204

- Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. London: John Wiley.

- Bormann, I., & Thies, B. (2019). Trust and trusting practices during transition to higher education: Introducing a framework of habitual trust. Educational Research, 61(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1596036

- Boxenbaum, E., & Rouleau, L. (2011). New knowledge products as bricolage: Metaphors and scripts in organizational theory. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 272–296. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0213

- Boyd, R. (1993). Metaphor and theory change: What is ‘metaphor’ a metaphor for? In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (pp. 481–533). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1993.tb00475.x

- Burke, C., Sims, D., Lazzara, E., & Salas, E. (2007). Trust in leadership: A multi-level review and integration. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(6), 606–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.09.006

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909–927. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

- Cornelissen, J. P. (2005). Beyond compare: Metaphor in organization theory. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 751–764. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.18378876

- Dietz, G. (2011). Going back to the source: Why do people trust each other? Journal of Trust Research, 1(2), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2011.603514

- Dietz, G., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2006). Measuring trust inside organisations. Personnel Review, 35(5), 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610682299

- Dirks, K. T. (2006). Three fundamental questions regarding trust in leaders. In R. Bachmann, & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 15–28). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Dirks, K. T., & de Jong, B. (2022). Trust within the workplace: A review of two waves of research and a glimpse of the third. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9(1), 247–276. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-083025

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

- Eriksson, P., & Kovalainen, A. (2016). Qualitative methods in Business research (2nd ed). Sage Publications Inc.

- Fleming, P. (2005). Metaphors of resistance. Management Communication Quarterly, 19(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318905276559

- Fulmer, C. A., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). At what level (and in whom) we trust. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1167–1230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312439327

- Gagné, M., Morin, A. J. S., & Schabram, K. (2020). Uncovering relations between leadership perceptions and motivation under different organizational contexts: A multilevel cross-lagged analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(6), 713–732. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uef.fi:2443/10. 1007/s10869-019-09649-4 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09649-4

- Graso, M., Jiang, L., Probst, T. M., & Benson, W. L. (2014). Cross-level effects of procedural justice perceptions on faculty trust. Journal of Trust Research, 4(2), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2014.966830

- Gustafsson, S., Gillespie, N., Searle, R., Hope Hailey, V., & Dietz, G. (2021). Preserving organizational trust during disruption. Organization Studies, 42(9), 1409–1433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620912705

- Hartley, J. (2004). Case Study research. In C. Cassell, & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 323–333). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312439327

- Janesick, V. J. (2000). The choreography of Qualitative Research design. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative research (pp. 379–399). Sage.

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287

- Karhapää, S.-J., & Savolainen, T. I. (2018). Trust development processes in intra-organisational relationships: A multi-level permeation of trust in a merging university. Journal of Trust Research, 8(2), 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2018.1509009

- Karhapää, S. (2016). Management change and trust development process in transformation of a university organization: A critical discourse analysis. Publications of the University of Eastern Finland. Dissertations in Social Sciences and Business Studies.

- Knudsen, S. (2005). Communicating novel and conventional scientific metaphors: A study of the development of the metaphor of genetic code. Public Understanding of Science, 14(4), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662505056613

- Korsgaard, M. A., Brower, H. H., & Lester, S. W. (2015). It isn’t always mutual. Journal of Management, 41(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314547521

- Kosonen, J., Miettinen, T., Sutela, M., & Turtiainen, M. (2015). Ammattikorkeakoululaki. Helsingin Kamari Oy.

- Kosonen, P., & Ikonen, M. (2019). Trust building through discursive leadership: A communicative engagement perspective in higher education management. International Journal of Leadership in Education. published online: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2019.1673903

- Kramer, R. M. (1996). Divergent realities and convergent disappointments in the hierarchic relation: Trust and the intuitive auditor at work. In R. Kramer, & T. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations (pp. 216–245). Sage.

- Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 569–598. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.569

- Kroeger, F. (2013). How is trust institutionalized? Understanding collective and long-term trust orientations. In R. Bachmann, & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of Advances in trust research (pp. 261–284). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Krot, K., & Lewicka, D. (2012). The importance of trust in manager-employee relationships. International Journal of Electronic Business Management, 10(3), 224–233.

- Kuismanen, M., & Spolander, M. (2012). Finanssikriisi ja finanssipolitiikka suomessa. Kansantaloudellinen Aikakauskirja, 108, 69–80.

- Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1996). Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In R. Bachmann, & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Landmark papers on trust, Vol II (pp. 388–413). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Li, P. P. (2012). When trust matters the most: The imperatives for contextualising trust research. Journal of Trust Research, 2(2), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2012.708494

- Li, P. P. (2017). The time for transition: Future trust research. Journal of Trust Research, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2017.1293772

- Malkamäki, K. (2017). Luottamuksen Kehittyminen Ja Johtamisjärjestelmää Koskeva Uudistus: Tapaustutkimus Kaupan Alan Organisaatiosta. Joensuu: University of Eastern Finland. Publications of the University of Eastern Finland. Dissertations in Social Sciences and Business Studies. In Finnish.

- Mayer, R. C., Bobko, P., Davis, J. H., & Gavin, M. B. (2011). The effects of changing power and influence tactics on trust in the supervisor: A longitudinal field study. Journal of Trust Research, 1(2), 177–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2011.603512

- Mayer, R., Davis, J., & Schoorman, D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59.

- Mishra, A. K., & Mishra, K. E. (1994). The role of mutual trust in effective downsizing strategies. Human Resource Management, 33(2), 261–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930330207

- Mishra, A. K., & Mishra, K. E. (2013). The research on trust in leadership: The need for context. Journal of Trust Research, 3(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2013.771507

- Morgan, G. (1983). Images of organization. Sage.

- Möllering, G. (2006). Trust: Reason, routine, reflexivity. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Möllering, G. (2013). Process views of trusting and crisis. In R. Bachmann, & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of Advances in trust research (pp. 285–305). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Möllering, G. (2014). Trust, calculativeness, and relationships: A special issue 20 years after Williamson’s warning. Journal of Trust Research, 4(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2014.891316

- Newman, S. A., Ford, R. C., & Marshall, G. W. (2020). Virtual team leader communication: Employee perception and organizational reality. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(4), 452–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488419829895

- O’Reilly, J., Aquino, K., & Skarlicki, D. (2015). The lives of others: Third parties’ responses to others’ injustice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000040

- Patient, D. L., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2010). Increasing interpersonal and informational justice when communicating negative news: The role of the manager’s empathic concern and moral development. Journal of Management, 36(2), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308328509

- Reiche, B. S., Bird, A., Mendenhall, M. E., & Osland, J. S. (2017). Contextualizing leadership: A typology of global leadership roles. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(2017), 552–572. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-016-0030-3

- Salminen, H., & Ylä-Anttila, P. (2010). Ammattikorkeakoulujen taloudellisen ja hallinnollisen aseman uudistaminen. Selvityshenkilöiden raportti. Opetus- ja Kulttuuriministeriön Julkaisuja, 2010, 23. Valtioneuvosto. In Finnish.

- Savolainen, T., & Ikonen, M. (2016). Process dynamics of trust development: Exploring and illustrating emergence in the team context. In S. Jagd, & L. Fuglsang (Eds.), Trust, organizations and Social interaction: Studying trust as process within and between organizations (pp. 231–256). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2016). Empowerment in veterinary clinics: The role of trust in delegation. Journal of Trust Research, 6(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2016.1153479

- Seligman, A. (2021). Trust, experience and embodied knowledge or lessons from john dewey on the dangers of abstraction. Journal of Trust Research, 11(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2021.1946821

- Seligman, A. B. (1997). The problem of trust. Princeton University Press.

- Shapiro, S. P. (1987). The social control of impersonal trust. American Journal of Sociology.

- Shrivastava, P., Ikonen, M., & Savolainen, T. (2018). Trust, leadership Style and Generational differences at work – A qualitative study of a three-Generation workforce from Two countries. Nordic Journal of Business, 66(4), 257–276.

- Tomlinson, E. C., Schnackenberg, A. K., Dawley, D., & Ash, S. R. (2020). Revisiting the trustworthiness–trust relationship: Exploring the differential predictors of cognition- and affect-based trust. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(6), 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2448

- Tourish, D., & Hargie, O. (2012). Metaphors of failure and the failures of metaphor: A critical study of root metaphors used by bankers in explaining the banking crisis. Organization Studies, 33(8), 1045–1069. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612453528

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, W. K. (2000). A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Review of Educational Research, 70(4), 547–593. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070004547

- Tyler, T., Degoey, P., & Smith, H. (1996). Understanding why the justice of group procedures matters: A test of the psychological dynamics of the group-value model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(5), 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.913

- Tyler, T. R. (1997). The psychology of legitimacy: A relational perspective on voluntary deference to authorities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1(4), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0104_4

- Tyler, T. R. (2003). Trust within organisations. Personnel Review, 32(5), 556–568. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480310488333

- Van der Toorn, J., Tyler, T.R., & Jost, J.T. (2011). More than fair: Outcome dependence, system justification, and the perceived legitimacy of authority figures. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 47, 127-138.

- van Houwelingen, G., van Dijke, M., & De Cremer, D. (2017). Fairness enactment as response to higher level unfairness. Journal of Management, 43(2), 319–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314530166

- Vanhala, M., Puumalainen, K., & Blomqvist, K. (2011). Impersonal trust. Personnel Review, 40(4), 485–513. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481111133354

- Whitener, E. M., Brodt, S. E., Korsgaard, M. A., & Werner, J. M. (1998). Managers As initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 513. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926624

- Yang, Y., Kuria, G. N., & Gu, D.-X. (2020). Mediating role of trust between leader communication style and subordinate’s work outcomes in project teams. Engineering Management Journal, 32(3), 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10429247.2020.1733380

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case Study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications.

- Zaheer, A., & Kamal, D. (2011). Creating trust in piranha-infested waters: The confluence of buyer, supplier and host country contexts. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.49