ABSTRACT

This paper offers an integrative review of the concept of dysfunctional trust from a trust and bias research perspective. Trust and cognitive/social biases are isomorphically related concepts in their functions as reducers of cognitive effort and facilitators/inhibitors of action. In the case of dysfunctional trust and distrust, bias perspectives contribute theoretically to a framework for the study of the ‘errors’ in decision-making that lead to dysfunctional outcomes of trusting. By reviewing biases and their role in generating trust and the converse, the biasing role of trust within a trust antecedent framework, the review integrates the conceptual linkages between research on bias and heuristics and research on trust, providing a basis for further research and practical applications in educational, business, political, and media domains. The paper makes recommendations for research and practical applications to mitigate the impacts of misinformation, bias in decision-making and dysfunctional trust. Attending to cognitive and other biases in situations involving trust promises to support greater informational resilience by raising metacognitive awareness of bias and trust in human decision-making.

Introduction

The extent to which one can and should trust others, institutions and information is an increasingly significant influence on the stability of organisations and social and economic systems in democratic capitalist societies (Zollo et al., Citation2015). In recent years social trust has declined steadily, culminating in 2021 being declared year of informational bankruptcy by the Edelman Trust Barometer (Edelman, Citation2021). The terms dysfunctional trust and distrust characterise trust in situations in which trust or distrust leads to dysfunctional outcomes within individual and organisational relationships (Anuar & Dewayanti, Citation2021; Lehtonen, Kinder, et al., Citation2021; Kramer, Citation1999; Lehtonen, Kojo, et al., Citation2022; Medina, Citation2020; Oomsels et al., Citation2019; Wiig & Tharaldsen, Citation2012). In the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine and the role played by misinformation and propaganda, the concept of ‘dysfunctional trust’ remains timely and relevant.

Trust serves the psychological function of deepening social exchange (Blau, Citation1964), reducing uncertainty, complexity and the need for more information (Luhmann, Citation1979; Morrison & Firmstone, Citation2000) while suspending doubt (Möllering, Citation2005) in situations of vulnerability and risk (Mayer et al., Citation1995). The notion of bias is linked with decision-making errors and is inherent in theoretical conceptualisations of trust. Without questioning their veracity, basing trust or distrust on erroneous inferences can lead to trust being misplaced or failing to be extended. Because of this, bias is thematically relevant to discussions of dysfunctional trust. While there has been some theorising on dysfunctional trust in the trust literature (Tomlinson & Lewicki, Citation2006), there is little theoretical integration of bias within the broader literature on dysfunctional trust. Work is needed to advance understanding of the topic further.

Aims of the paper

This paper focuses on dysfunctional trust, emphasising the process that leads to it, namely dysfunctional trusting. It aims to integrate the concept of dysfunctional trust within the theoretical literature on trust and bias. For this purpose, the paper briefly reviews definitions of trust linked to the integrative process model of trust (Mayer et al., Citation1995) and available conceptions of dysfunctional trust. Similarly, a definition of bias and its relevance to trust are outlined. The review then organises selected work on trust and bias conceptually around the trust antecedent framework. Theoretical and practical implications of dysfunctional trust are then discussed. Recommendations for further research and practical strategies for engaging with trust in contemporary contexts are then provided.

This paper makes three main contributions. There has been a growth in interest in studying the constituents of trust and bias, including trust in decision-making and heuristics (Lewicki & Brinsfield, Citation2019) and focus on the trustor (Möllering, Citation2019). This paper contributes to the emerging debates in the field by addressing psychological aspects of trust situated in the trustor and the contextual aspects that provide the ‘what’ and ‘in whom’ one trusts. As a first contribution, this paper provides a synthesis of theoretically linked perspectives on bias and trust, focusing on the relatively new and emerging concept of dysfunctional trust.

Secondly, the interest in trust constituents stems from the need to develop more nuanced insights into trust as a process for making sense of crises (Möllering, Citation2013; Möllering & Sydow, Citation2019). With the predicted trends toward greater disruption in post-COVID society and organisations in future (Grinin et al., Citation2021) and a crisis in trust (Edelman, Citation2021), there has been a growing interest in trust in the disrupted contexts of economic crises, technological change and strategic organisational change (Gustafsson et al., Citation2021), and in global crises such as pandemics, climate change, poverty, political upheavals and international conflicts (for example, Lopez-Claros et al., Citation2020; Stern, Citation2009). It is in these contexts that dysfunctional trust becomes especially salient. As the experience of COVID-19 highlights, the effects of misinformation and mistrust on organisational and individual relationships create severe challenges for institutions in overcoming the effects of propaganda (Morkūnas, Citation2022), suspicion of organisations (Van Prooijen et al., Citation2022) and implementing measures that facilitate an organisationally resilient response during crises (Barua et al., Citation2020). This review contributes to the theorising of trust and distrust in disrupted contexts.

Thirdly, questions regarding functional and dysfunctional trust and bias have practical implications for management and decision-making in disrupted contexts because trust and bias connect fundamentally to ontological and epistemic questions, namely beliefs about what is real and what can be relied on as a basis for trust. A synthesis of trust and bias perspectives is highly relevant to building and repairing epistemic trust in social and organisational systems damaged by misinformation and fake news (Reglitz, Citation2021; Sinatra & Hofer, Citation2016; Tanzer et al., Citation2021). Researchers and practitioners from various fields will be interested in applying the integrated conceptual and methodological insights for studying dysfunctional trust offered in this paper.

Method for integrative review

Suggestions for writing integrative reviews (Torraco, Citation2016) informed the preparation of this paper. The topic emerged from earlier work presented at a conference in 2016 and is further indebted to the feedback from reviewers that led to an extensive review of the earlier versions of this paper and the adoption of dysfunctional trust and distrust as the focus for the integration.

Google Scholar and PsycInfo were used to identify relevant definitions and terms relating to the focus of this study. below shows a list of examples of the search terms used.

Table 1. Example search terms for integrative review.

The literature on bias alone is vast; additional filters were employed to reduce the amount of material surveyed by searching in the title (e.g. allintitle: ‘cognitive bias’) and using domain databases such as PsycInfo. Articles of interest were chosen iteratively throughout the process of writing this review. Search terms were combined to explore the intersection between different concepts. As the paper centred on dysfunctions of trust, terms such as ‘mistrust’, ‘distrust’, and ‘human error’ emerged from early readings of work and were added to refine searches. Additional terms were added to identify named biases and how these had been used in theorising trust, for example, ‘illusory control’, ‘negativity bias’, ‘optimism bias’, and ‘confirmatory bias’.

Dysfunctional trust and dysfunctional trusting reflect an emergent rather than an established field. This insight led to the thematic organisation of the review based on the trust antecedent framework to provide the necessary integrative framework for the conceptual and theoretical development of dysfunctional trust in future research.

Definitions of trust

A widely accepted definition in trust research is the definition given by Mayer et al. (Citation1995), defining trust as ‘the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party’. This definition forms the basis of the trust antecedent model in which trust as a willingness to be vulnerable is the outcome of antecedent processes (evaluations of trustees’ trustworthiness and trustor disposition in Mayer et al., Citation1995). While this model has received broad support due to its contribution toward theoretical integration in a fragmented field, additional domain-specific antecedents have been proposed in extensions of this framework (e.g. Dietz & Den Hartog, Citation2006). PytlikZillig and Kimbrough (Citation2016) make the point that ‘a full understanding of trust requires inclusive attention to many different aspects, including the dispositions, perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, expectations, and intentions of the trustor; characteristics of the trustee; and features of the context or situation in which the trustor and trustee are embedded’ (PytlikZillig & Kimbrough, Citation2016, p. 37).

The definition of trust adopted in this paper follows Mayer et al. (Citation1995) in framing trust defined as the willingness to be vulnerable based on expectations (relating to the trustee’s likely behaviour), risk (vulnerability) and agency (the ability to control outcomes). Distrust is regarded as a separate construct to trust, which is functionally equivalent to trust (McKnight & Chervany, Citation2001). While trust might be based on an expectation that performance and obligations will be met, distrust is an expectation that they will not (Barber, Citation1983; McKnight & Chervany, Citation2001), leading to an unwillingness to be vulnerable (Bijlsma-Frankema et al., Citation2015).

Definition of dysfunctional trust

Dysfunctional trust has received scant attention in the literature, owing to a ‘positivity bias’ in trust research (Oomsels et al., Citation2019). Interest in dysfunctional trust seems to be related to specific contexts (e.g. public services, nuclear safety, management, military, business, commerce, and personal relationships), thus making it an applied concept with broad appeal. The term ‘dysfunctional trust’ has been used in relatively few papers and is often used with little definition or connection to the trust literature or theories on trust. Some researchers associate dysfunctionality in trust with ‘blind trust’ (Engen & Lindøe, Citation2019; Lehtonen, Kojo, et al., Citation2022; Medina, Citation2020). Interest in the ‘dark side of trust’ (Skinner et al., Citation2013) also links with dysfunctional trust, and distrust not always being negative. Where definitions are available, the term ‘dysfunctional trust’ has been defined as a state that exists on a continuum ranging from functional to dysfunctional (Tharaldsen et al., Citation2010). As several authors note, trust and distrust can be functional or dysfunctional (Anuar & Dewayanti, Citation2021; Wiig & Tharaldsen, Citation2012). What leads to the switch between functional and dysfunctional states has been referred to as dysfunctional trusting (Hart et al., Citation2021). From a Luhmannian perspective, dysfunctionality arises because trust (or distrust) fails to remove uncertainty or complexity (Wiig & Tharaldsen, Citation2012). Dysfunctional trust and distrust depend on whether trusting or distrusting has been functional and dysfunctional in its outcomes. It may not be possible to determine when dysfunctional trust occurs without judging the outcome, creating a conceptual challenge. Potentially, functional processes of uncertainty reduction may lead to dysfunctional outcomes because they fail to reduce uncertainty or because the outcome for the trustor incurs penalties that impact their (or their organisation’s) functioning. Further attention will be given to this issue in the discussion later in the paper.

Dysfunctional state vs dysfunctional process definitions

Definitions of dysfunctional trust appear to be underdeveloped. Much of the literature uses dysfunctional trust and distrust to refer to outcome states in contexts defined by relations between individuals and organisations based on trust, distrust or both.

In dysfunctional trust, dysfunctionalities arise from the consequences of betrayal and unmet expectations. Such concerns approximate the idea of trust creating informational blind spots that are dysfunctional in the context in which they occur (Lehtonen, Kojo, et al., Citation2022; Tharaldsen et al., Citation2010). In contrast, dysfunctional distrust exists as a state because distrust destroys trust, thus impacting adversely on relations. Such conditions lead to a lack of disclosure and reporting (e.g. safety reporting: Conchie & Donald, Citation2008), inability to solve problems and resolve conflicts (Tomlinson & Lewicki, Citation2006) and failure to collaborate when it would be beneficial to do so (Boin & Bynander, Citation2015). Harms arising from dysfunctional distrust can be detrimental beyond individual impacts, harming social systems and preventing them from preventing or engaging effectively with crises.

Based on the above, a definition of dysfunctional trust and dysfunctional distrust is proposed:

Dysfunctional trust: ‘A state of positive expectations regarding another party’s fulfilment of obligations which turn out to be unmet, exposing the trustor and others to increased risk of harm due to reliance on the trustee to meet their obligation’.

Dysfunctional distrust: ‘A state of negative expectations regarding another party’s failure to fulfil obligations, which turn out to be unwarranted, leading to failures in relations, processes, and harmful consequences for individuals and systems’.

The term dysfunctional trusting (Hart et al., Citation2021) will be used when referring to trust as a process rather than a state. However, in Hart’s definition of dysfunctional trusting as ‘a tendency to distrust benign authorities and/or trust strangers’ (Hart et al., Citation2021, p. 2), the focus on distrust in this definition appears more like a definition of dysfunctional distrusting. Their definition does not include situations in which people misplace trust rather than distrust and is limited to situations involving distrust of authorities or strangers. Because dysfunctional trusting can occur with well-known individuals (e.g. celebrities or politicians), reference to strangers as in Hart’s definition has been replaced below with the more general term ‘others’. As both distrust and trust can be dysfunctional, separate definitions for dysfunctional trusting and distrusting are proposed:

Dysfunctional trusting: ‘the process of trusting others or organisations who are likely to act in untrustworthy ways to the detriment of the trustor’.

Dysfunctional distrusting: ‘the process of distrusting others or organisations who are likely to act in benign, trustworthy ways favourable to the trustor’.

Definition of cognitive bias

Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1974) introduced the concept of cognitive bias, which has been defined in various ways (Trimmer, Citation2016). There is evidence of at least sixty cognitive biases affecting thinking and decision-making (Baron, Citation2008). Cognitive biases are commonly framed as a lack of accuracy and impartiality and a form of systematic error in thinking resulting from constraints and characteristics of information processing. Such conceptions are not without challenges since it is difficult to state what bias is a deviation from (Hahn & Harris, Citation2014). Typically, such perspectives imply that bias exists relative to an optimised ideal based on the actions a rational actor would take to achieve optimal outcomes. However, this risks conflating processes of bias with their outcomes. Marshall et al. (Citation2013) highlight the distinction between cognitive and outcome biases. Outcome biases result in suboptimal outcomes from the perspective of what a rational actor would do. In contrast, cognitive biases may be optimal (for example, in optimising cognitive effort and reducing complexity), enabling an individual organism to act but risk non-optimal outcomes.

A potential area for confusion is that error is often assumed as a binary issue: either there is an error, or there is not. However, the point at which error becomes noticeably detrimental may be difficult to define because harm or risk may occur incrementally, leading to cascades of precipitating factors that result in functional failures. To avoid the term ‘error’ in the definition, cognitive ‘bias’ is defined here more broadly as ‘a systematic (that is, non-random and, thus, predictable) deviation from rationality in judgment or decision-making’ (Blanco, Citation2017, p. 1).

Biases are typically classified according to their source processes. The dominant model, dual process theory, distinguishes system 1 (automatic, fast, effortless) and system 2 (deliberative, effortful, slow and conscious) processes (Stanovich & West, Citation2000). However, theoretical traditions with diverging epistemological and conceptual assumptions (Hahn & Harris, Citation2014) do not universally agree with such classifications. However, they broadly agree with the dual process conception of bias. For example, hot biases differ from cold biases in that the former are motivated and directed by emotion in contrast to the latter, which are automatic, largely unintentional, and the result of information processing errors (MacCoun, Citation1998). To address limitations of the dual processing model, Stanovich (Citation2011) proposed a tri-process conception of cognition, which posits that metacognitive processes for reflection are needed to switch between automatic fast and slow dual-process systems (systems 1 and 2). In this conception, thinking errors may be attributable to failures in metacognitive monitoring of individuals’ internal dialogues rather than solely to automatic or motivated processes. Previous work suggests this approach may be suitable for preventing decision-making errors by activating meta-cognitive resources during decision-making (McIntyre et al., Citation2018).

Despite their potential contribution to decision-making failure, one should not assume that biases are intrinsically bad (Hahn & Harris, Citation2014). Although biases can lead to poor decision-making, their psychological function reduces effort, complexity and uncertainty in otherwise cognitively overwhelming situations. Biases may have few consequences on daily functioning because, in most situations, social cognition approximates optimised decision-making models (Fiske & Taylor, Citation2013). Similarly, trust has few negative consequences in most situations: the default position is for people to trust others initially (McKnight et al., Citation1998), a stance that performs well in most social settings, most of the time reducing complexity and uncertainty and smoothing social exchange. Only in exceptions does trusting lead to adverse social and personal outcomes. Therefore, when viewed as an aspect of social cognition, trust and bias appear isomorphically and functionally related, both providing efficient and often effective cognitive effort reduction in situations of social complexity, ambiguity, risk, and uncertainty. This implies functional overlaps, which require further integration theoretically and will now be addressed in the remainder of the paper.

Conceptual integration of bias and trust perspectives

This section focuses on the link between trust and bias as constituents of dysfunctional trusting and distrusting. This section begins with a short discussion of trust as a form of bias. The subsections then develop a synthesis of bias and trust perspectives based on the trust antecedent framework as the organising principle.

Insights from research into confidence tricksters highlight how biases (both hot and cold) can increase individuals’ vulnerabilities to manipulation to trust dysfunctionally (Boles et al., Citation1983; Konnikova, Citation2016; Lyons & Mehta, Citation1997; McCaghy & Nogier, Citation1984). The distinction between cognitive and affective components found in the bias literature is also found in trust research (Lewicki & Bunker, Citation1996; McAllister, Citation1995). Although conceptually distinct, such isomorphism supports the paper's aim of developing an integrated view of dysfunctional trust from both trust and bias perspectives.

Trust has previously been described as a persistent positivity bias (Fiske & Taylor, Citation2013). Yamagishi and Yamagishi (Citation1994) referred to trust as a cognitive bias. A careful reading of their interpretation suggests that by ‘trust’, they mean a general tendency to trust, which positively influences evaluations of others. This definition implies that rather than trust (e.g. the willingness to be vulnerable) being the source of bias, bias already exists at the antecedent stages of trust (Mayer et al., Citation1995) in the form of generalised trust, propensity to trust or dispositional trust, terms that are often used interchangeably to refer to this antecedent (for a further discussion of this concept see the section later in this paper). A potential problem with the Yamagishi and Yamagishi (Citation1994) description of trust as bias is that it risks conflating trust with its antecedents (See also Mayer et al., Citation1995).

More recently, Lewicki and Brinsfield (Citation2019) have considered the integration of trust within a heuristics approach in which trust and distrust are conceptualised as frames that lead to biased decision-making. Lewicki and Brinsfield make a case for viewing the trust frame not just as an interactional construction (e.g. based on the relationship between parties in trust exchange) but as a cognitive representation. They identify three main approaches for understanding what is framed. These are: (1) Frames about issues pertinent to the decision, (2) cognitive representations of the self, others and relationships and (3) cognitive representations of the anticipated interactional processes. briefly summarises Lewicki and Brinsfield’s organisation of approaches.

Table 2. Three approaches to studying the content of trust frames.

There is little to disagree with in Lewicki and Brinsfield’s discussion. However, the integration between trust and heuristics seems reductive, potentially limiting the exploration and study of trust. Trust and distrust may be outputs of heuristics and framing rather than acting merely as frame inputs or content. For example, in job selection, under the availability heuristic, a candidate may easily be imagined as someone likely to perform well in a job, and it may then become easier to imagine them to be honest. The difficulty here lies in deciding when judgements of characteristics relevant to the trustee become activated (e.g. before the heuristic judgement is made or because of a subsequent process involving conjunction fallacy, namely the erroneous belief that because the candidate already seems a good fit with a job, they must also then be trustworthy). Focusing on specific biases in trust judgements may be more helpful in studying dysfunctional trusting in specific contexts. The subsequent discussion is therefore aligned more broadly with cognitive biases and trust (which include some framing biases), showing how trust and bias may create dysfunctional trust. However, this does not imply that heuristics and frames are unimportant or irrelevant.

The following four sections are organised according to components of the trust antecedent framework (Mayer et al., Citation1995). The aim is to show the relevance of work on biases and trust to theorise and extend the concept of dysfunctional trust. Mayer and colleagues imply via their definition of trust that the confident expectations generated by trust are independent of trustors’ ability to control risks. However, their 2007 paper argues that trust and control may not be mutually exclusive, with control filling a gap between trust and risk (Schoorman et al., Citation2007). Therefore, we have included a further section on trust and control. The order of the section is as follows: (1) Evaluation of trustees, (2) Trust, vulnerability, and risk, (3) Trust and control, and (4) Personality, trust, and bias.

Perceptions and evaluations of trustees

A core idea in the trust antecedent framework is that trustors evaluate trustees’ trustworthiness (framed as competence, benevolence, integrity) based on available information and general beliefs about trusting others (Mayer et al., Citation1995). There is abundant evidence that biases influence evaluations of others’ trustworthiness; for example, via ingratiation effects produced by the trustee (Ziemke & Brodsky, Citation2015), social desirability and attractiveness of the social target in jury and non-jury contexts (Ahola et al., Citation2009; Korva et al., Citation2013; Reilly et al., Citation2015), articulatory fluency (Zürn & Topolinski, Citation2017), perceived warmth and competence (Fiske et al., Citation2007), facial characteristics of the trustee (Petrican et al., Citation2014), characteristics of an online name (Silva & Topolinski, Citation2018) and egocentric bias (Posten & Mussweiler, Citation2019). Such biases may confirm existing beliefs about a trustor or by framing the trustee to make them seem unlikely to expose or exploit the trustor’s vulnerabilities.

Bias and trust in performance evaluations. Schafheitle et al. (Citation2016) provide an example of trust and bias in performance evaluations and their impact on managerial behaviour and trust. Using qualitative, content-analytic methodology, they found that managers’ trustworthiness judgements of employees were based on judgements of competence, integrity, and benevolence. Furthermore, trust was also influenced by propensity to trust, structural, situational factors, and motivational reasons specific to the context (e.g. the need for reducing managerial workload). Pertinent to the discussion on bias, they provided evidence that managers’ decision-making errors regarding employee performance evaluations preceded managers’ trust in each employee. They point towards specific biases (recency effects and false cost–benefit calculus) affecting perceptions of employee trustworthiness. Such biases in performance evaluations can be dysfunctional in organisations by impacting performance appraisal (Bellé et al., Citation2017), non-detection of false job performance (Dunnion, Citation2014), and potentially masking risky or counterproductive behaviours when the mechanisms for checking or monitoring are relaxed. Concerning internal organisational threats resulting from job performance, uncritical acceptance of trustworthiness judgements can contribute to the non-detection of insider threats by increasing the tendency of others to remain silent (Rice & Searle, Citation2022).

Trust, distrust, and stereotypes. Looking at the impact of trust on stereotype bias during evaluations, one might expect increased trustworthiness to reduce negative stereotype bias. However, Posten and Mussweiler (Citation2013) conducted a series of experiments exploring the effects of trust on stereotypes. Using a variety of experimental approaches, they manipulated the trustworthiness of the target and found judgements to be less stereotyped across different targets (women, ethnic minorities, overweight people, and pairs of objects) when participants were primed via a distrust mindset vs a trust or neutral mindset. The possible explanation for this counter-intuitive finding is that distrust activates non-routine information processing (dissimilarity mindset), thus disrupting activated stereotypes.

Conversely, evaluating people as trustworthy removes doubt and thus maintains people’s existing erroneous beliefs about a person because it removes the need for additional processing. Posten and Mussweiler's (Citation2013) work suggests that trustworthiness evaluations can be disrupted to avoid trapping trustors in a particular stereotype frame. However, in practice, such disruption raises ethical problems when making stereotyped populations appear less trustworthy, as the use of distrust cues to de-bias stereotypes may amplify negative stereotypes where the stereotype involves distrust (Posten & Mussweiler, Citation2013). Therefore, careful consideration must be given to the context and approach in which this is applied.

In the previous example, trust impacted stereotype formation. People appear to be aware of others’ potential biases towards them and trust based on this awareness. Research from applied studies of recruitment and selection highlights that people place greater trust in selection processes when selection panels make decisions when potentially biasing information is removed from the awareness of shortlisting panels (Klotz et al., Citation2013) thereby increasing applicants’ perception of fairness and motivation to apply.

Foddy et al. (Citation2009) present a study of allocation processes highlighting how trustors’ perceptions of stereotyping by others can impact trust. Using economic trust games, they found that trust in the ‘allocator’ is higher during allocation processes when trustors believe that the trustee belongs to the same ingroup. Shared ingroup membership increases trust because people expect favourable behaviours from someone who shares their group membership, even when the shared ingroup is negatively stereotyped. In selection processes, risks of stereotyping may be more salient and have more significant costs (e.g. not getting a job); these amplify distrust of selection processes when information relating to stereotypes becomes known to the selection panel. Foddy et al. (Citation2009) may apply to selection situations where some applicants may be more likely to apply for positions if they believe that shared group membership provides some advantages in the selection process. Examples of this exist during recruitment and selection where candidates’ awareness of recruiters shared educational background (e.g. elite universities or schools) may result in attracting more applicants who belong to the same group as the recruiters leading to reduced applicant pool diversity and increased social exclusiveness (Ashley & Empson, Citation2013). In the case of recruiting from under-represented groups, knowing that recruiters are from the same group as an applicant may act as a positive signal to apply. Such dynamics play out depending on the nature of the stereotypes, characteristics of parties involved, aspects of the allocation processes and the meaning of the outcomes to individuals.

Attributional biases and trust. Attributional biases are a distinct class of social biases referring to ‘errors’ in explaining and inferring one’s own and other people’s motivation for behaviours (Heider, Citation1958; Kelley, Citation1967; Malle, Citation2011). Attributions can be counterintuitively irrational such that trustors infer trustworthiness from the vulnerabilities arising from dependence on the trustee (Weber et al., Citation2004) or judgements of facial characteristics (criminality: Klatt et al., Citation2016; integrity: Weber et al., Citation2004). There are several well-studied attributional biases (fundamental attribution error; self-serving bias; actor-observer asymmetry) that are relevant to understanding how people judge other people’s intentionality, sincerity and cooperativeness in dysfunctional trust situations (Chan, Citation2009; Malle & Knobe, Citation1997; Reeder et al., Citation2004; Tomlinson & Mayer, Citation2009).

Social cognition employs multiple pathways that operate in a sequentially hierarchical fashion (Reeder et al., Citation2004). This process ensures that facets relevant to a situation (the actor’s goals, motives, and traits) are prioritised (intention over personality inferences, desire over belief inferences) to assess others’ mental states (Malle & Holbrook, Citation2012). This interplay between automatic and consciously controlled components gives rise to biased judgements about people’s trustworthiness. For example, in Reeder’s study, participants were asked to judge a target’s helping behaviour. Participants were primed with additional information that cued the motivation of the target’s behaviour as either being obedient or as being self-serving. In a judgement task involving the same target’s behaviour, obedient targets were viewed as dispositionally more helpful (and therefore more benevolent) than self-serving targets. This supports the claim that inferring ulterior motives leads to discounting other evidence of disposition that would otherwise increase favourable social inferences regarding a trustee’s trustworthiness. Here, one might find one possible explanation why conspiracy theories’ use of ulterior motives as an ‘argument’ is so effective in reducing trust in the target of the conspiracy and any sources for counterarguments, thereby inoculating the conspiracy believer against proof to the contrary.

Trust, vulnerability, and risk

Risk is a necessary condition for conceptualising trust across disciplines (Rousseau et al., Citation1998). However, risk means different things to different people (Slovic et al., Citation1982) and depends on how aware people are of their vulnerabilities in a risky situation. Vulnerabilities arise from (a) the perceived probability (e.g. certainty/uncertainty) of an event on the one hand and (b) the extent and characteristics (real or perceived) of the threat of loss involved in the risk on the other. How people frame risk is an important factor in risk perception (Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1981). Framing distorts risk perception depending on the type of risk, frame characteristics, the nature of the decision task (Kühberger, Citation1998), perception of chance in determining the outcome (Bohnet & Zeckhauser, Citation2004) and other variables (e.g. age: Best & Charness, Citation2015; personality: Lauriola et al., Citation2014).

Siegrist et al. (Citation2021) carried out a study looking at the role of trust in perceptions of COVID-related health risks. They used two measures of trust: general trust and social trust (a measure that operationalised beliefs in the trustworthiness of government) and found that while general trust decreased risk perceptions, high trust in government tended to increase perceived health risk regarding COVID. Siegrist et al. (Citation2021) argue that methodological issues are important considerations in selecting scales for research as measures of general trust and trust in government tap different aspects of trust. Considering the COVID context of their study, high trust in government increases the likelihood that public health messages are taken seriously, thus creating more salient perceptions of health risk. General trust relates to how much, in general, people can trust others, and this might reflect general feelings of safety and security regarding risks stemming from other people (for example, trusting that others would self-isolate if testing positive), resulting in decreases in perceived health risk. As the case of Siegrist et al. highlights, different types of trust can generate high certainty in parallel but lead to different implications for risk, some of which may be dysfunctional (for example, taking risks based on trust in other people’s health-related behaviour).

Das and Teng (Citation2004) portray trust and risk as mirror images of each other. Here, risk and trust have inverse relationships. For example, if subjective goodwill trust is high, relational risk is perceived to be low. If subjective competence-based trust is high, perceived performance risk is low. In this framework, trust and risk perceptions are updated when relevant information becomes known. The reciprocal paths between trust and risk facilitate biased social perceptions; perception of risk may reciprocally affect goodwill- and competence-based trust. Bias in such trade-offs in Das & Teng’s model is exemplified in studies where cost–benefit evaluations can be shown to lead to errors. For example, as Schafheitle et al. (Citation2016) have shown, when risk control measures are rejected due to a biased cost–benefit calculus, risks resulting from a lack of control are underestimated, and benefits overemphasised, leading to an increase in the tendency to base decisions on perceived employee trustworthiness, but without adequate risk control in place.

From a risk-based perspective, trust choices follow a mostly non-monotonic logic pathway. In non-monotonic decisions, the default ‘conclusion’ is adjusted as new information, which challenges the original conclusion, is added (Nebel, Citation2001). This matches the process by which trust is reduced from a default position (e.g. initial trust: McKnight et al., Citation1998) as negative information (e.g. regarding vulnerabilities and risk) becomes available. While default trust acts as a form of positivity bias in a situation of risk, negativity bias and its over-attention to negative information override the more favourable expectations at the start of a relationship. Together, these processes might explain why trust declines over time since a consistent bias for attending to negative events would incrementally impact the initially more favourable view existing at the beginning of a relationship and thus gradually expose greater levels of risk that were not visible earlier in the process leading to loss of goodwill over time.

Eiser and White (Citation2005), studying negativity bias, note that positive information requires greater levels of confirmation than negative information, thus making it easier to confirm negatives. This might help explain the complex ways in which confirmatory bias often impacts trust appraisals of negatively construed information, for example, by amplifying the valence of perceived risks focalised in contemporary public discourses regarding risks, including conspiracy theories (e.g. vaccines and telecommunications during COVID19) and misinformation campaigns.

Trust and control

It has been stated that trust is only necessary for situations in which there is no control over the outcomes (Leifer & Mills, Citation1996). Other theorists have viewed trust and control as parallel concepts (Das & Teng, Citation1998) because trust and control can increase confidence in expected outcomes. Furthermore, low trust and high mistrust may increase the need for control by the trustor (Golin et al., Citation1977), while a lack of control amplifies the need for trust.

Control is subject to bias through the tendency of individuals to perceive illusory control (Langer, Citation1975; Thompson, Citation1999). Findings suggest that people are more likely to overestimate personal control in familiar situations, specifically those focused on achieving desired or needed outcomes in which they have some agency. Perceived control is subject to optimism bias for various outcomes, with greater optimism leading to a greater sense of control (Klein & Helweg-Larsen, Citation2002). Based on these insights, one can argue that while trust is only necessary for situations where the trustor has no primary control, the trustor’s reliance on a trustee may well be dependent on the illusory perception that by trusting, the trustor gains secondary control over the outcomes produced by the trustee (Klein & Helweg-Larsen, Citation2002).

Trustees’ lack of control may be relevant as to whether they can maintain their obligations to the trustor and whether they should engage in trust exchange in the first place (Banerjee et al., Citation2006). However, a trustee’s perceptions of their control may also be prone to illusion effects (for example, in financial trading: Bansal, Citation2020; Fenton-O’Creevy et al., Citation2003). In such cases, control vital to the exchange may not exist or fail to materialise. Here a trustee can attempt to increase control over a situation to honour the terms of the exchange or seek to control the visibility of their failure to retain it. Alternatively, and more ethically, rather than seeking to create an impression of control, perceiving uncertainty over control may lead the trustee to consider disengaging from a trust exchange to avoid the reputational risks that could result from failure.

There is not much data on trustors’ perception of trustees’ lack of control of risks, although study of regulators’ perceptions of regulatees’ intention to control risk highlights the importance of such perceptions (Wiig & Tharaldsen, Citation2012). In regulatory environments, regulator distrust may be met with attempts to achieve greater control through rigid control strategies (Engen & Lindøe, Citation2019). However, these may backfire as they signal excessive distrust resulting in feelings of resentment and betrayal (Medina, Citation2020) and reducing trust between regulators and regulatees (Wiig & Tharaldsen, Citation2012).

Bias, trust and personality

Explaining trust as a function of people’s personality characteristics is a popular conception of why some individuals are more trusting. Propensity to trust (P2T), sometimes referred to as dispositional trust, general trust, or trusting tendency, has been the dominant model of personality in trust research. It is regarded as a trait-like antecedent to trust that can be defined as a basic stance toward trusting (McKnight et al., Citation2002). A variety of personality traits have been linked with propensity to trust (Evans & Revelle, Citation2008). Consistent evidence shows a link between P2T and the agreeableness trait in the Five Factor model of personality (McCrae & John, Citation1992) as a positive orientation towards trusting (Mooradian et al., Citation2006). Agreeableness reflects how well people get on with others in interpersonal contexts (Chmielewski & Morgan, Citation2013) and is related to conformity with group norms that might lead to bias.

P2T appears to act analogously to an information filter (Govier, Citation1994; Searle et al., Citation2011) which influences the selection of information in favour of trusting others. Evidence for this idea stems from studies showing that P2T moderates relationships between organisational variables that are relevant to trust, such as justice perceptions (Colquitt et al., Citation2006), support and satisfaction (Poon et al., Citation2007), and risk (Chen et al., Citation2015). However, while the idea might imply P2T biases judgement and decision-making, no clear evidence demonstrates a single mechanism implied by the information filter analogy, suggesting that underlying processes generate the filtering effects.

By drawing attention to bias and the processes that produce it, research on P2T may become better focused on the cognitive and affective mechanisms that create the moderating effects observed empirically. A more in-depth understanding and reappraisal of P2T may be possible in terms of its nomological relationships with other constructs (Cronbach & Meehl, Citation1955 ) rather than a more reductionist view of P2T as a singular dispositional cause of bias. Instead, P2T may be better described as a hybrid form construct (McEvily & Tortoriello, Citation2011), a construct in which several interacting and dynamic processes, for example, optimism bias (Frazier et al., Citation2013) or personality factors such as agreeableness produce biasing effects. Thus, rather than P2T being a singular process or trait, a better way to conceptualise it may be as a proxy for a combination of cognitive and social biases that contribute to a more favourable assessment of people’s trustworthiness.

Recently Hart et al. (Citation2021) suggested a link between dysfunctional trust and dark triad personality types (machiavellianism, psychopathy and narcissism), leading those high in dark triad traits to be more gullible to trusting dysfunctionally. In contrast, unlike dark triad traits, P2T is not connected to gullibility (Rotter, Citation1980) and its connection with dysfunctional trusting is not well established. While there are a range of measures to assess the influence of personality antecedents, establishing their relationship with dysfunctional trust is dependent operationally on (a) showing there is an antecedent (e.g. P2T, dark triad) and (b) demonstrating an outcome that is dysfunctional in the context in which it occurs. The current lack of evidence regarding a relationship between P2T and dysfunctional trust suggests potential avenues for research into trust and personality, extending theory with a closer examination of how personality-based processes might lead to dysfunctional trust outcomes. Attention to how personality impacts dysfunctional trust and distrust may provide valuable insights for team and leadership training and recruitment to ensure that teams are balanced and have sufficiently diverse perspectives for evaluating decisions.

Methodological considerations

The main aim of this paper was to provide an integrative perspective of dysfunctional trust within the theoretical literature on trust and bias. Attention to research methodologies will be provided briefly next.

Economic game methodologies have dominated research in the systematic study of trust and bias, contributing to the methodological convergence in experimental trust and bias research (Alós-Ferrer & Farolfi, Citation2019). Critiques of experimental game methodologies suggest these approaches lack ecological validity, although results of studies linking results from experimental and non-experimental studies of trust appear to produce consistently robust results (Banerjee et al., Citation2021). While critiques of these approaches challenge the use of trust games in real-world settings, trust games have practical utility in revealing otherwise hidden aspects of individuals’ private worlds that cannot be observed via self-report measures or interviews (Pisor et al., Citation2020). An emergent view across bias, trust and behavioural economic research is that a detailed understanding of trust requires multi-method approaches spanning quantitative and qualitative approaches (Hodgson & Cofta, Citation2009; Kramer, Citation2015). Similarly, non-quantitative approaches can contribute to understanding bias in trust contexts (Diary method: Gibbons et al. Citation2022; Critical incident technique: Keers et al., Citation2015).

While surveys are popular in trust research and utilised extensively in research on public attitudes and various organisational settings, survey-based work is harder to operationalise in studies of bias. To demonstrate bias, one must be able to show the deviation from an unbiased performance which may be problematic with cross-sectional design. Survey participants may not be aware of their bias or may be influenced to present themselves in a more favourable light. Survey results can be significantly affected by socially biased responding, resulting in variable distributions of some measures that are significantly non-normal. Such threats to validity apply to both experimental work and surveys on trust (Thielmann et al., Citation2016 ). It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the technical solutions for such issues. However, considering diverse multi-method approaches to the study of trust and bias is an essential step for operationalising trust and bias in the same studies, overcoming methodological limitations and method biases that systematically distort our understanding of the link between trust, bias and other variables of interest.

Interactions between context and methodologies must be considered carefully in studying dysfunctional trust and distrust. Dysfunctional distrust may be associated with significant reactance (Lumineau, Citation2017; Soveri et al., Citation2020), which may impact data collection. In organisational settings, this can lead to tendencies to misattribute responsibility for dysfunctionality, denial, or faking, making it difficult to separate the phenomenon from its subjective experience. There is a lack of published survey tools that assess dysfunctional trust in individuals, let alone audit organisations and their cultures for elements of dysfunctional trust. Survey measures have been used in studies of dysfunctional trust, although these are typically tailored to the context and are often not validated against the broader methodological developments in trust research (Dietz & Den Hartog, Citation2006; McEvily & Tortoriello, Citation2011). This conceptual and measurement gap highlights avenues for methodological integration and innovation that could improve the quality of measures and conceptualisations of dysfunctional trust in line with those used in established trust research.

Concluding discussion

This integrative review provided insights regarding the relationship between trust and bias in dysfunctional trust, framed by a focus on the constituents of the trust antecedent model. Together this contributes an answer to the question of why and how people might trust or distrust dysfunctionally. As outlined, bias in information processing leads to selective filtering and discounting of cues that can attenuate perceptions of the trustee’s trustworthiness, mitigate or amplify perceptions of risk and vulnerability, and impact perceived trustor and trustee control. Fundamentally these processes create the subjective reasons for trusting or distrusting, regardless of whether trust or distrust in each situation is rightful or misplaced. Considering trust as the output of subconscious cognitive and affective processes is not new. However, a spotlight on bias provides a more refined perspective of antecedent processes that lead to trust, including risk framing, vulnerability, and control, which can produce dysfunctional trust (or distrust).

The review also highlighted one of the fundamental challenges with integrating trust and bias perspectives, namely the levels-of-analysis problem, whereby depending on which concepts are tapped, different elements come to the fore. Concepts belonging to trust theories are often analysed as relational qualities, whereas bias formulations are typically more internally focused on information processing, motivation, and goals. Whether trust is a bias, or an output of biased processing is at the heart of this problem. However, as some of the reviewed work highlights, bias occurs in the context of the messiness of social exchange, making it difficult to identify, even more so, since bias and dysfunctional outcomes may be effects intended by hostile actors.

While past theorists have referred to trust as a slippery (Nooteboom, Citation2000) or elusive (Gambetta, Citation1988) concept, the perspectives offered in this paper suggest that trust is elastic as a theoretical concept. This differs from Bohnet et al.'s (Citation2010) use of the term trust elasticity, referring to responsiveness to changes in expected economic returns. Instead, elasticity emerges because trust (and bias) can appear at different stages of the process as antecedents or outputs, depending on context and situational dynamics. When considering trust and bias as variables within the process of dysfunctional trusting, this exposes the often-complex ways in which trust and bias occur in workplaces and other contexts leading to poor decision-making and dysfunctional consequences.

As a further example, consider regulatory enforcement practices in medical practice or the petroleum industry as described by Wiig and Tharaldsen (Citation2012). Regulators may have separate explanations of compliance violations that may focus differentially on motives, attitudes, and capabilities of regulatees – combinations of these present different pathways towards dysfunctional outcomes (e.g. accidents, medical errors). Regulatory non-compliance in these contexts may result from how trust, distrust, and bias are expressed by all parties within the context. As a result, regulators need to employ ‘diverse combinations of trust and distrust depending on the context and type of regulatee [they] are approaching’ (Wiig & Tharaldsen, Citation2012, p. 3045). Distrust of an overconfident medical diagnosis is functional, but too much distrust can harm the relations between regulators and regulatees. Awareness of bias and trust can provide a more nuanced understanding of such contexts.

While the review was primarily concerned with interpersonal patterns of trusting, in dynamic contexts, trust often involves the extension of trust or distrust via intermediaries, for example, word of mouth and third parties, or symbolically by the presence of symbolic markers of trust. Understanding bias and trust may be particularly relevant to network and system researchers interested in dysfunctional trust since processes that filter and systematically select information may produce noticeably dysfunctional effects at scale rather than at the interpersonal or small group level. Such dynamicity adds considerable complexity to the study of dysfunctional trust and distrust. Studies of the QANON phenomenon in the US provide an insight into the complexity and dysfunctionalities of network trust. QANON, an ideologically right-wing political movement, recruits individuals into epistemologically baseless conspiracy theories. Its pervasiveness is sustained through social media and the radicalisation of individuals (Moskalenko, Citation2021) via the creation of epistemic bubbles that produce a shared alternate reality driven by distrust of the establishment. Within such bubbles, distrust of benign authorities will appear to be a coherent norm (Nguyen, Citation2020), leading to erosion of trust in elected governments because the effects of individual distrust are amplified across the network.

Conceptual limitations

This paper has focussed extensively on cognitive aspects of the trust process that point towards interpersonal trusting as an explanatory level. Much of the literature on dysfunctional trust and distrust sits thematically in administrative, governance, regulatory and safety systems rather than in dyadic relationships. This raises the question of how well this paper's explanatory level applies in these contexts. However, based on a similar issue regarding their integrative model of trust, Schoorman et al. (Citation2007) have argued that the trust antecedent model (which was used for framing this review) translates well from interpersonal to higher levels of analysis. However, they recognise methodological and conceptual tensions that may require further scholarship. More recently, multi-level trust models (Fulmer & Gelfand, Citation2012) have highlighted complexities arising from multi-level and multi-referent trust. Creating conceptual clarity of dysfunctional trust and distrust at an individual level of its antecedent process provides an insight into how trust might travel between organisational levels and across referents. In organisations, patterns of structural relations and power amplify dyadic processes. For example, an individual regulatory officials’ distrust resulting from their evaluation of risk and trustworthiness of a team they inspect may directly impact relations between the individual regulator and the team. However, the officials’ evaluation also feeds into the broader regulatory system by contributing to the organisation-level evaluation by the regulatory body – the control measures implemented in response to regulator distrust shape subsequent relations within and between organisations within such a system. Excessive controls amplify distrust signals in regulatory environments (Wiig & Tharaldsen, Citation2012), which can lead to dysfunctional employee responses (e.g. sabotage, revenge; Kramer, Citation1999). It is beyond the scope of this review to address the role of feedback in how distrust and trust travel dynamically across organisational levels and boundaries more fully. However, the conceptual clarification offered in this present review may be helpful to researchers interested in considering dysfunctionality within multi-level theories of trust and distrust.

When defined as a state or as a process, dysfunctional trust might refer to a specific class of dysfunctional outcomes or processes in which trust or distrust act as precursors for dysfunctional choices made by trustors. However, describing outcomes of trusting as dysfunctional depends on whether there is a clear, precisely accurate function in the first place (Khan, Citation2002). Conceptually dysfunctional trust can be problematic because trust, by its nature, does not offer guarantees, and there is always a probability that trusting will produce a harmful outcome. Thus, whether a trust outcome is dysfunctional at the level of unmet positive or negative expectations can only be known after a trustor has trusted or distrusted. Thus, the dysfunction appears to be primarily located in the outcome rather than in the process of trust or distrust.

A related issue raised by one of the reviewers for this paper is that from an uncertainty perspective, trust may be dysfunctional if it fails in its function to reduce complexity enough to act, regardless of whether those actions prove wrong. This issue touches fundamentally on the Luhmannian view regarding what functions trust serves and what it is as a process. There may not be many situations where trust fails outright to generate certainty since initial trust is usually high (McKnight et al., Citation1998). This suggests that failure to reduce uncertainty may be an incremental condition, for example, with trust eroding over time. Sudden failure of trust to reduce uncertainty may occur under rupture in relationships, betrayal or other breaches in trust, whereby trust as a taken-for-granted basis for a relationship suddenly fails in maintaining certainty and is replaced by distrust. However, as the cognitive system is optimised to make sense of the world, certainties may only be temporarily disrupted.

As discussed in this paper, certainty is generated from constituent affective and cognitive processes activated during trusting, which lead to positive or negative expectations and their respective subjective probabilities. If these processes fail to generate the certainty required for positive expectations, the response may be to switch to processes that generate certainties for negative expectations. The coactivation of simultaneous processes during trusting ensures that individuals are likely to establish some form of uncertainty reduction and basis for action even when trust and distrust themselves fail to resolve uncertainty. Behavioural responses such as denial, dismissal and minimising of information may achieve uncertainty reduction; they are epistemically dysfunctional because they deviate more significantly from the reality of a situation (e.g. just because one denies a complex fact, or an uncertain risk does not mean the basis for the fact or risk ceases to exist).

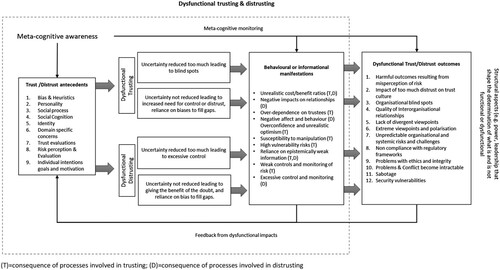

By discerning the antecedent process of dysfunctional trusting (rather than dysfunctional trust) from its outcomes, the present paper sought to overcome the difficulty of specifying the locus of dysfunctionality: It may be in the process, the outcome, or both. The separation of dysfunctional trust from dysfunctional trusting and its antecedents ( below) is practically and theoretically useful, clarifying potential conceptual problems in research and theory.

Recommendations

This review has provided some theoretical groundwork for developing a more integrated view of dysfunctional trust, drawing on empirical and theoretical work on trust and bias. There are several clear recommendations for future research and practice:

Methodological diversity. More diverse methodologies are needed to avoid measurement traps created by method effects. Dysfunctional trust is a property of systems with many moving parts. As the examples show, dysfunctional trust evolves due to interactions in networks, systems, and cultures that can amplify individual-level trust, distrust, and bias. While studies of bias and trust using traditional methodological paradigms are helpful for detailed studies of bias or other trust constituents, dysfunctionality is difficult to operationalise or measure in a dysfunctional context. Therefore, work on dysfunctional trust may benefit from applied, qualitative work, including discourse and thematic analyses, ethnographic and action research approaches, that can account for individuals’ subjective experience of bias and trust during dysfunctional trusting as well as understanding the context-dependent meanings attached to acts of trusting and dysfunction.

Bias as an antecedent to trust. Trust as a bias. Studies are needed to operationalise bias as an antecedent to trust/distrust and, conversely, trust or its constituents as a source of bias. The concept of P2T offers a potentially rich area for work on bias and trust in the context of dysfunctional trust. The advantage of such work lies in providing further empirical evidence of the relationship between types of bias and constructs used in trust research. One avenue for work would be to look at developing nomological nets of constructs in trust research that could make the link between trust and cognitive and other biases more explicit. A promising and innovative approach to nomological network analysis may be found in recent approaches to psychological network analysis (Fried et al., Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2018) that can be used in studying networks of constructs in complex settings, but which has so far not been applied to research on trust.

Conceptual development of dysfunctional trust and distrust. For the reasons outlined above, the concept of dysfunctional trust needs further refinement. While this review has focussed on mostly individual psychological elements of trust and distrust leading to dysfunctional outcomes, more work is needed on group and system-level processes. This review has provided a basis for theorising that could enhance understanding of dysfunctional trust and trust more generally across levels. An exciting question building on Schoorman et al. (Citation2007) and Fulmer and Gelfand (Citation2012) is how systemic and organisational level processes might reflect or amplify trust processes at lower levels leading to emergent and often unintended dysfunction at higher levels.

Focus on remedies. Epistemic dysfunctionalities, including vaccine hesitancy, climate change scepticism, and populism, are significant problems for the world in the twenty-first century and efforts to remedy them are still in short supply. More attention to remedies for dysfunctional trusting is therefore required. Evidence from debiasing research highlights the difficulty of preventing errors in judgement and decision-making (Kahneman, Citation2011) as many processes are automatic, operating outside of awareness. Work on meta-cognitive processes (Stanovich, Citation2011) may be of particular interest in this context for developing practical educational interventions. Examples of applied work can be found in Van der Linden and colleagues’ work on public inoculation against climate misinformation (Van der Linden et al., Citation2017). Their work draws on an understanding of social cognition and trust, which appears to activate meta-cognitive understanding of the intentions of misinformation practices used by climate change deniers. A focus on bias and trust could help develop similar educational approaches in other domains and help improve awareness of bias, critical thinking, monitoring, and other meta-cognitive strategies to enhance epistemic awareness and protect individuals and organisations from being trapped by their cognitions and trust during decision-making.

What is functional or dysfunctional? The functionalist perspective implied in dysfunctional trust also requires careful attention. Who decides what is functional or dysfunctional and when dysfunctions require repair? At what point does trust or distrust cross a threshold to become dysfunctional? Critical and radical perspectives are needed to move beyond normative functionalist epistemological and ontological paradigms evident in research on trust repair (Gillespie & Siebert, Citation2018). In a complete conceptualisation, issues of power, authority and influence are likely to be important areas of work, especially when trust and distrust have become sources of polarisation stemming from the intersection between epistemic issues and identity that may impede attempts to reduce impacts of the social divisions this has created.

Focus on integrity and ethics. Politics, governance, and social media continue to create and maintain dysfunctional trust and distrust dysfunctionalities. It would be naïve to assume that there is a single approach or even that such approaches will work to disrupt dysfunctionalities. However, a concentrated focus and public debate regarding integrity, fairness, justice, and ethics in all areas of public life may be needed to reduce harms stemming from systemic trust and distrust. Such efforts require political will and honest self-appraisal, which may be in short supply.

This work will resonate with researchers in trust and decision-making interested in tackling the complex challenges arising from dysfunctional trust and distrust. The hope is that it will stimulate research that engages the methodological and conceptual issues this paper has presented. Can we address the global challenges of our age? Maybe. By understanding better, the constituents of trusting and distrusting that lead to dysfunctional outcomes, trust researchers may be able to reduce the deleterious effects that erosion of trust produces in solving the problems facing people, organisations and societies.

Acknowledgements

Dr Madeleine Knightley and Dr Jem Warren for reading earlier drafts of this paper, Dr Paul Piwek for the discussion of non-monotonic logics and for the unknown reviewers whose feedback helped to shape the final structure and narrative.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Volker Patent

Volker Patent is a Chartered Psychologist and working in the fields of Business Psychology, Sustainability, Community Engagement and Coaching. He currently holds a position as lecturer in the School of Psychology at the Open University, where he is Employability lead for the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. He obtained his PhD in 2015 from the Open University and previously has held teaching roles at Bedfordshire University, Putteridgebury management centre, worked freelance as a trainer, consultant and assessment specialist in industry, medical recruitment and public engagement. His research specifically focuses on trust and personality in organisations, mentoring and coaching, and trust in individual and organisational decision-making. He is currently working on psychological aspects of climate change. His research appears in the British Journal of Social Work, in Searle & Skinner (2011) Trust in Human Resource Management, the Journal of Trust Research and he has had conference papers accepted at FINT, EAWOP, ENESER, and the International Congress on Assessment Center Methods.

References

- Ahola, A. S., Christianson, S. Å., & Hellström, Å. (2009). Justice needs a blindfold: Effects of gender and attractiveness on prison sentences and attributions of personal characteristics in a judicial process. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 16(sup1), S90–S100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710802242011

- Alós-Ferrer, C., & Farolfi, F. (2019). Trust games and beyond. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 887–901. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00887

- Anuar, A., & Dewayanti, A. (2021). Trust in the process: Renewable energy governance in Malaysia and Indonesia. Politics & Policy, 49(3), 740–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12409

- Ashley, L., & Empson, L. (2013). Differentiation and discrimination: Understanding social class and social exclusion in leading law firms. Human Relations, 66(2), 219–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712455833

- Banerjee, S., Bowie, N. E., & Pavone, C. (2006). An ethical analysis of the trust relationship. In R. Bachmann, & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 303–317). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Banerjee, S., Galizzi, M. M., & Hortala-Vallve, R. (2021). Trusting the trust game: An external validity analysis with a UK representative sample. Games, 12(3), 66–82. https://doi.org/10.3390/g12030066

- Bansal, T. (2020). Behavioral finance and COVID-19: Cognitive errors that determine the financial future. SSRN, 3595749.

- Barber, B. (1983). The logic and limits of trust. Rutgers University Press.

- Baron, J. (2008). Thinking and deciding (4th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Barua, Z., Barua, S., Aktar, S., Kabir, N., & Li, M. (2020). Effects of misinformation on COVID-19 individual responses and recommendations for resilience of disastrous consequences of misinformation. Progress in Disaster Science, 8, 100119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100119

- Bellé, N., Cantarelli, P., & Belardinelli, P. (2017). Cognitive biases in performance appraisal: Experimental evidence on anchoring and halo effects with public sector managers and employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 37(3), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X17704891

- Best, R., & Charness, N. (2015). Age differences in the effect of framing on risky choice: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 30(3), 688–698. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4556535/pdf/nihms693210.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039447.

- Bijlsma-Frankema, K., Sitkin, S. B., & Weibel, A. (2015). Distrust in the balance: The emergence and development of intergroup distrust in a court of law. Organization Science, 26(4), 1018–1039. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2015.0977

- Blanco, F. (2017). Cognitive Bias. In J. Vonk, & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_1244-1

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Transaction Publishers.

- Bohnet, I., Herrmann, B., & Zeckhauser, R. (2010). Trust and the reference points for trustworthiness in Gulf and Western countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 811–828. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2010.125.2.811

- Bohnet, I., & Zeckhauser, R. (2004). Trust, risk and betrayal. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55(4), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2003.11.004

- Boin, A., & Bynander, F. (2015). Explaining success and failure in crisis coordination. Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 97(1), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoa.12072

- Boles, J., Davis, P., & Tatro, C. (1983). False pretense and deviant exploitation: Fortunetelling as a con. Deviant Behavior, 4(3-4), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.1983.9967623

- Chan, M. E. (2009). “Why did you hurt me?” Victim’s interpersonal betrayal attribution and trust implications. Review of General Psychology, 13(3), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017138

- Chen, Y., Yan, X., Fan, W., & Gordon, M. (2015). The joint moderating role of trust propensity and gender on consumers’ online shopping behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.020

- Chmielewski, M. S., & Morgan, T. (2013). Five-factor model of personality. In M. D. Gellman, & J. R. Turner, (Eds.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 803–804). Springer.

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Judge, T. A., & Shaw, J. C. (2006). Justice and personality: Using integrative theories to derive moderators of justice effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100(1), 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.09.001

- Conchie, S. M., & Donald, I. J. (2008). The functions and development of safety-specific trust and distrust. Safety Science, 46(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2007.03.004

- Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040957

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B.-S. (1998). Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.2307/259291

- Das, T., & Teng, B. (2004). The risk-based view of trust: A conceptual framework. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(1), 85–116. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBU.0000040274.23551.1b

- Dietz, G., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2006). Measuring trust inside organisations. Personnel Review, 35(5), 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610682299

- Dunnion, M. (2014). The masked employee and false performance: detecting unethical behaviour and investigating its effects on work relationships [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Worcester. https://eprints.worc.ac.uk/5104/.

- Edelman. (2021). 21st annual Edelman trust barometer. Retrieved September 2, 2021, from https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2021-03/2021%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer.pdf

- Eiser, J. R., & White, M. P. (2005). A psychological approach to understanding how trust is built and lost in the context of risk. CARR conference ‘Taking Stock of Trust’. London School of Economics.

- Engen, O. A., & Lindøe, P. H. (2019). Coping with globalisation: Robust regulation and safety in high-risk industries. In J.-C. L. Coze (Ed.), Safety science research (pp. 55–73). CRC Press.

- Evans, A. M., & Revelle, W. (2008). Survey and behavioral measurements of interpersonal trust. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1585–1593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.07.011

- Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Nicholson, N., Soane, E., & Willman, P. (2003). Trading on illusions: Unrealistic perceptions of control and trading performance. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903321208880

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

- Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2013). Social cognition: From brains to culture. Sage.

- Foddy, M., Platow, M. J., & Yamagishi, T. (2009). Group-based trust in strangers: The role of stereotypes and expectations. Psychological Science, 20(4), 419–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02312.x

- Frazier, M. L., Johnson, P. D., & Fainshmidt, S. (2013). Development and validation of a propensity to trust scale. Journal of Trust Research, 3(2), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2013.820026

- Fried, E. I., van Borkulo, C. D., Cramer, A. O., Boschloo, L., Schoevers, R. A., & Borsboom, D. (2017). Mental disorders as networks of problems: A review of recent insights. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z

- Fulmer, C. A., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). At what level (and in whom) we trust: Trust across multiple organisational levels. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1167–1230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312439327

- Gambetta, D. (1988). Trust: making and breaking cooperative relations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Gibbons, J. A., Dunlap, S., Friedmann, E., Dayton, C., & Rocha, G. (2022). The fading affect bias is disrupted by false memories in two diary studies of social media events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 36(2), 346–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3922

- Gillespie, N., & Siebert, S. (2018). Organizational trust repair. In R. Searle, A. Nienenbar, & S. Sitkin (Eds.), The Routledge companion to trust (pp. 284–301). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315745572-20

- Golin, S., Terrell, F., & Johnson, B. (1977). Depression and the illusion of control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86(4), 440–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.86.4.440

- Govier, T. (1994). Is it a jungle out there? Trust, distrust and the construction of social reality. Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review/Revue canadienne de philosophie, 33(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0012217300010519

- Grinin, L., Grinin, A., & Korotayev, A. (2021). Global trends and forecasts of the 21st century. World Futures, 77(5), 335–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2021.1949939

- Gustafsson, S., Gillespie, N., Searle, R., & Dietz, G. (2020). Preserving organizational trust during disruption. Organization Studies, 42(9), 1409–1433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620912705

- Hahn, U., & Harris, A. J. (2014). What does it mean to be biased: Motivated reasoning and rationality. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 61, 41–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800283-4.00002-2

- Hart, W., Breeden, C. J., & Lambert, J. (2021). Exploring a vulnerable side to dark personality: People with some dark triad features are gullible and show dysfunctional trusting. Personality and Individual Differences, 181, 111030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111030

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Hodgson, P., & Cofta, P. (2009). Towards a methodology for research on trust. In Anon (Ed.), Proceedings of the WebSci’09: Society On-line. Greece: Athens.

- Jones, P. J., Mair, P., & McNally, R. J. (2018). Visualising psychological networks: A tutorial in R. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1742. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01742

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

- Keers, R. N., Williams, S. D., Cooke, J., & Ashcroft, D. M. (2015). Understanding the causes of intravenous medication administration errors in hospitals: A qualitative critical incident study. BMJ Open, 5(3), e005948. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005948

- Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 15, 192–238. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Khan, M. A. (2002). On trust as a commodity and on the grammar of trust. Journal of banking & finance, 26(9), 1719–1766. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(02)00189-9