Abstract

The aim of this article was to describe the implementation of a team-based MAC intervention, and discuss important aspects to consider when implementing the MAC protocol in elite team sports. The MAC program contains seven modules in which core concepts such as mindfulness, acceptance, and values-driven behavior are being taught and practiced. We experienced conceptual as well as practical challenges in the application of the MAC protocol. A general recommendation in implementing MAC concepts and exercises for teams is to make the content of the program sport-specific.

Background

During the past decade, there has been an increasing interest in applying mindfulness- and acceptance-based approaches in sport settings, resulting in the development of several tailor-made interventions that specifically target sport performance enhancement (Sappington & Longshore, Citation2015). The first and the most cited mindfulness- and acceptance based intervention, specifically designed for athletes, is the Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment protocol (MAC; Gardner & Moore, Citation2007), based primarily on the principles of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl & Wilson, Citation1999). A major objective within the ACT is to increase psychological flexibility by modifying the individual’s relationship to cognitive and emotional processes rather than trying to control or reduce unwanted cognitive and emotional content. Key concepts in ACT such as acceptance, experiential avoidance (the tendency to try to escape, avoid, or modify experiences such as unwanted thoughts and emotions), and cognitive defusion (the ability to view thoughts simply as thoughts that do not have to be true reflections of neither the self nor reality) have been adopted in MAC (see Hayes et al., Citation1999, for more information about ACT).

In contrast to traditional cognitive control-based techniques (e.g., thought stopping, arousal control), the MAC approach does not focus on controlling and reducing potential performance-inhibiting internal experiences. From a MAC perspective, athletic peak performance rather requires: (1) a present-centered external attentional focus on current sport tasks; (2) nonjudgmental awareness and acceptance of cognitions, emotions, and sensory experiences; and (3) behaviors, actions, and decisions need to be in line with personal values and athletic goals (Gardner & Moore, Citation2007). The MAC program was initially designed for individual athletes but Gardner and Moore (Citation2007) later provided a description of how to apply the program in a group-based setting.

In general, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that various heterogeneous mindfulness/meditation interventions in multiple-sport populations are more effective than control conditions on sport performance-related outcomes (Bühlmayer, Birrer, Röthlin, Faude, & Donath, Citation2017; Noetel, Ciarrochi, Van Zanden, & Lonsdale, Citation2017; Sappington & Longshore, Citation2015). Few studies have, however, studied a group-based MAC protocol and to our knowledge, no published studies so far have examined the effectiveness and applicability of the MAC-protocol for teams (see, Noetel et al., Citation2017, for an overview). However, group-based ACT-interventions have shown good results in non-sport populations (e.g., Brinkborg, Michanek, Hesser, & Berglund, Citation2011), suggesting that group-based interventions also may have potential in sport settings with team sport athletes. Currently, there are no manuals or thorough descriptions, to our knowledge, on how group-based interventions (i.e., MAC) can be carried out in team sport settings. A team is usually defined as a group of people who interacts towards a shared objective (e.g., Carron, Hausenblas, & Eys, Citation2005). When we use the term “team sport”, we refer mainly to sports where the particular objective “involves facilitating the movement of a ball or similar item in accordance with a set of rules, in order to score points” (Fabou, Citation2014, p. 202) (e.g., ice hockey, soccer, basketball). Moreover, the importance of examining what type of teamwork training that actually improves team performance has been highlighted by several researchers (i.e., McEwan, Ruissen, Eys, Zumbo, & Beachamp, Citation2017). By doing so, it is possible to develop intervention modules that are essential for team effectiveness and team performance enhancement. Based on a recently conducted study (Josefsson et al., Citation2018) the aim of this article is, therefore, to describe the implementation of a MAC intervention within a male and a female elite floorball team, and discuss important aspects to consider when implementing the MAC protocol in a team sport setting.

Description of the MAC-intervention

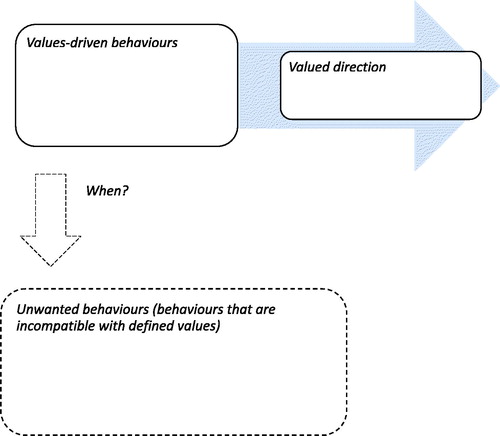

Thirty-eight floorball players (19 men and 19 women, mean age = 23.6, SD = 3.76) from a Swedish National League floorball club in the first division participated in the intervention. Both the male team and the female team had seven 50-min sessions, and met once a week for 7 weeks. The MAC-program is a 7-module protocol (Gardner & Moore, Citation2007). (1) Preparing the client with psychoeducation: information about theoretical and practical aspects of the intervention and an introduction to the structure and the content of the full MAC program. (2) Introducing mindfulness and cognitive defusion: the meaning of these concepts was defined and explained, and how they could be applied in a sport context. (3) Introducing values-driven behavior: In the third module, different values (e.g., values in life, values in floorball) were discussed. Values-driven behavior versus emotion-driven behavior was introduced to the players. In order to make the theme floorball-specific, we used the so called “arrow-model” as a framework (see ). The arrow model is a pedagogical tool that can be used for self-reflection as well as development of action plans and goalsetting on both team- and individual levels. In this model, the participant identifies his or her individual floorball-specific values as well as target behaviors that are compatible with these values. For example, a defense player who wants to be more offensive (valued direction), may target the behavior to challenge the opponent more often (values-driven behavior). In this particular context, valued direction is similar to process goal. The athletes worked individually with their arrow-models, and after the models were completed, the players were instructed to present their models to a team mate. Finally, the players were given the assignment to practice identified values-driven behaviors during training and matches. (4) Introducing acceptance: The primary purpose of this module is to develop an understanding about the consequences associated with experiential avoidance, and the potential benefits with applying experiential acceptance when striving for improved performance. The players were instructed to identify and add unwanted behaviors to their personal arrow-models, and also to specify in which situations these behaviors usually occur (see ). For example, the defender who wanted to be more offensive identified the unwanted behavior to often play “safe” by passing the ball to a teammate rather than to move forward and challenge the opponent (values-driven behavior). The players then presented their updated arrow-models to a team mate. (5) Enhancing commitment: presentation of the concepts motivation and commitment, how they differ from one another, and their relation to performance-related values and behaviors. Again using the arrow-model (see ) as a tool, the players were given the task to review (and possibly update) their values-driven behaviors in order to make sure that the targeted behaviors were specific enough to implement during training and matches. (6) Skill consolidation and poise—combining mindfulness, acceptance, and commitment: the main purpose of this module is to attain and maintain behavioral flexibility. (7) Maintaining and enhancing mindfulness, acceptance, and commitment: summary and evaluation of previous modules. In the last session, the players first completed a written evaluation form (anonymously) and then we discussed the usefulness and applicability of the MAC content. For more detailed information about the content in each MAC module, see Gardner and Moore (Citation2007).

In the implementation phase of the intervention the practitioner experienced several challenges that might have influenced the success of implementing the MAC protocol.

Individual differences

A sports team usually consists of members that most likely will differ in a large number of ways; in personality traits, education, motivation, and coping style, to name just a few. Even if the competence of the consultant and the quality of the content in each session are adequate, individual differences may still influence to what extent the single member will benefit from an intervention such as the MAC protocol. Some team members may rather quickly and easily internalize and apply principals and tools taught in the program, whereas others may struggle to both understand and apply theoretical intervention features (e.g., defusion techniques, acceptance, mindfulness). Previous researchers have highlighted the need to not see athletes as a homogenous population, and that personality traits as well as pre-therapy diagnoses should be considered (Sappington & Longshore, Citation2015). In the present study, we identified four areas of individual differences among the athletes that most likely influenced the extent team members find the MAC approach useful and rewarding: motivational, social, personality, and cognitive differences.

Motivational differences

In our experience, a key person in motivating athletes and increasing their interest to engage themselves in a psychological intervention is the coach. If the coach clearly expresses the significance and usefulness of participating in the MAC intervention, even team members who are skeptical to “mindfulness” and psychological counseling in general may be persuaded to make a serious effort to commit themselves to the program. In the present intervention, we found the coaches to be supportive and very helpful in the arrangements and scheduling of the MAC sessions. Moreover, the majority of the players appeared to be fairly motivated to take part in a MAC intervention and many of them were also curious and active during the sessions. We can only speculate but we believe that the coaches’ positive attitudes to the MAC intervention most likely contributed to increasing the players’ motivation and activity during the sessions. We also noticed that highly motivated players who were very active during sessions also functioned as motivators for less motivated team members.

Personality, social, and cognitive differences

Aside from motivational issues, group-based interventions in which group discussions are an important and integral part may be a barrier for athletes who find it hard to express themselves verbally in a group. We clearly noticed that some players avoided speaking in group discussions, not necessarily because of lack of interest but rather because they did not feel comfortable to do so, perhaps because they lacked confidence to speak in public and/or that they were more introvert and reserved as individuals. Several players, on the other hand, were very verbally active and seemed to appreciate the group format for discussing MAC themes such as mindfulness and values. Moreover, some players immediately seemed to understand core MAC concepts and how they could be linked to floorball-specific situations whereas others struggled to grasp the meaning of concepts as well as exercises. Some players seemed to not quite understand the idea of certain concepts and exercises, particularly how and why they could be useful for athletes, and more specifically, how they could be applied to a floorball context. In particular, several players found theoretical concepts such as mindfulness, acceptance, and cognitive defusion to be rather abstract and ambiguous.

In an attempt to clarify these multifaceted MAC-related concepts and principals, we tried to exemplify them in a floorball setting by using the arrow-model, which we found to be a very useful tool for discussing participant-generated experiences and examples. Several players expressed that it became a lot easier to understand the application of concepts and exercises when we used floorball examples. Hence, it should be acknowledged that athletes will differ in their cognitive ability to understand theoretical concepts and how they might be implemented in a sport setting. Furthermore, a technique we found to be useful to enhance both theoretical understanding as well as verbal activity was to let the athletes work with various assignments in small groups of two to three persons. By doing so, it appeared to be easier for quiet and shy athletes to contribute to the discussion. Also, athletes who appeared to be too afraid to ask questions to the MAC instructor in the whole group seemed to find it easier to do that in a small group setting. In addition, it is also an advantage if the MAC instructor could be available for questions during group discussions as well as after each session.

Values, commitment, behavior, and goals

Whereas the two first sessions mostly included psychoeducation and introductions of MAC concepts, resulting in a relatively low group activity, the involvement among the players were significantly increased when the participants started working with the “arrow-model.” As previously mentioned, several athletes found it initially difficult to understand theoretical concepts (i.e., mindfulness, cognitive defusion, acceptance), and particularly, how to practically implement them in floorball. By letting the athletes use the arrow-model to identify personal values, behaviors, and goals, the MAC concepts appeared to make a lot more sense to the players when these terms were set individually in a floorball context. In a way, it seemed like this was the actual start of the intervention, probably because the floorball-specific discussions about values and behaviors were seen as particularly interesting and relevant for the players. Once the individual work with the arrow-model had been initiated, this was the primary tool we used during the intervention when we worked with the themes in the following modules. After the arrow-model was introduced in module three, we could more easily discuss the importance and applicability of values, mindfulness, acceptance, commitment, present-centered attention, and psychological flexibility. For example, in module four, when acceptance was discussed, a key question for the players to reflect on was: “are you willing and prepared to do your best to follow your identified values-driven behaviors, even if this path potentially may lead to difficult challenges?”

Individual vs. team-values and goals

A critical issue when working with teams is to what extent personal values match team-values, and if it is possible to work with individual team member’s values, behaviors and goals. Gardner and Moore (Citation2007) recommend that group-based MAC interventions should try to develop overarching team-values rather than to focus on individual performers’ values and goals. However, conflicting values between team and individual performer could just as well be a potential problem when working individually with a team-athlete. We decided to work with individual values, behaviors and goals but we tried to make sure that it was done in compatibility with the team’s playing system. Still, some athletes started to discuss that some athletic goals (e.g., to be a more offensive defender) may not necessarily be compatible with the team’s playing system. A possible way to prevent this potential conflict could be to first work with team values, behaviors, and goals by creating a team arrow-model.

After team-values has been clarified and settled, the players can then start working with their individual arrow-models. However, it is not only important to synchronize individual values and goals with those of the team, it is just as crucial to make sure that the player’s individual values also are compatible with other team members’ values. For instance, it may be a problem if all defenders concurrently start working with enhancing behaviors in order to be more offensive. Thus, team members need to be aware of which individual values, behaviors, and goals teammates are currently working with, so that they can more easily appreciate and support each other’s actions during matches and training. Several forwards, playing together in the same line, discussed their personal targeted behaviors in between sessions and started to encourage each other to continue striving for defined values-driven actions during matches, something that potentially could advance the cooperation between teammates. Thus, an interaction between teammates during the work with the individual arrow-model may inspire the development of a culture in which team-members continuously support and encourage each other to progress both as individual players as well as a team.

Conceptual challenges with the MAC protocol

The MAC protocol is a very comprehensive theory-based program, including many home assignments in between sessions, requiring that an athlete needs to invest a lot of time in the program apart from the seven sessions. This may not be particularly problematic when working with a strongly motivated athlete who is prepared to devote the time needed to complete the assignments but we found it to be a challenge to motivate a whole team to practice mindfulness exercises at home. In the evaluation of the program, some players expressed that they found the program to be quite time-consuming and demanding with one session a week, home assignments, and several unfamiliar concepts to digest. As previously mentioned, the players found it particularly difficult in the beginning to understand how these theories and exercises could improve floorball skills. We believe that it is especially important that team members see an intervention as accessible and relatively easy to apply in sport-specific situations. Even if earlier research indicate that effects of mindfulness based interventions on various health outcomes are maintained at follow-ups (Khoury et al., Citation2013), very few studies have investigated long-term effects of these programs on mindfulness skills and performance-related outcomes in athlete populations (Sappington & Longshore, Citation2015). However, preliminary results suggest that mindfulness practice over a longer period of time may be more effective for sport performance enhancement than short interventions (Thompson, Kaufman, De Petrillo, Glass, & Arnkoff, Citation2011), suggesting that athletes may need further time to assimilate and apply principals and exercises taught in mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions.

Recommendations

First, we suggest that the sequence of modules is altered. The first three sessions could contain sport-specific values, behaviors, goals, and commitment in three steps, using the arrow-model as the primary tool throughout the intervention: (1) team values, (2) individual values, and finally (3) where the players present their individual arrow-models for each other in small groups. Preferably, those players who play together in the same line could work together. We would argue that this altered sequence could motivate reluctant athletes to actively engage in the program right from the start. Additionally, it might also be easier for the athlete, in the final segment of the first module, to set specific personal goals for participating in the MAC program. We believe that MAC concepts that could be considered as somewhat abstract (i.e., acceptance, mindfulness, and cognitive defusion) may be easier to assimilate with this altered sequence. Acceptance could be the theme for the fourth session, and mindfulness and cognitive defusion could be topics for module five. The consultant should also be careful to clearly explain and exemplify how these concepts can be implemented in the specific sport. In our experience, the ability to explain theoretical concepts and exercises by giving examples close to the specific sport is very beneficial in building trust and engagement.

Second, the coach should be involved in the entire program, something that is particularly important when working with team values. The coach and the MAC practitioner could together develop a strategy for how to best implement MAC exercises and theoretical concepts (e.g., acceptance, values-driven behavior, present-centered attention, brief centering exercise) in the team’s regular practice. Thus, to link MAC exercises and theoretical concepts to sport-specific practice should arguably increase the players’ understanding, both of the concepts and how to actually apply MAC features to improve performance in training and matches. This view is supported by earlier research on teamwork interventions that show that interventions, designed to enhance team effectiveness and team performance, are more effective if they include experiential activities that team members are able to develop and practice (McEwan et al., Citation2017).

Third, group dynamics in general should be considered when working with a team. The group processes in traditional group-based therapy, are emphasized as very important for the effectiveness of the intervention. Several different factors are proposed to be involved in group-therapeutic processes, such as the relationship between group members, the therapeutic alliance, the group’s learning climate, and level of optimism for improvements in psychological health (Bieling, McCabe, & Antony, Citation2006). We suggest that: (i) arrow-models are created that are well matched between the team-arrow and individual arrows; and also (ii) that the players’ individual arrow-models are synchronized with each other.

Fourth, make the program less intense by increasing the intervention length, for example to 12–15 weeks. By doing so, the players will get more time to thoroughly comprehend the meaning of MAC concepts as well as to practice MAC exercises. It is especially important to make sure that the players recognize how MAC principals and techniques can be implemented, first in regular training, then in matches.

Fifth, the players should frequently rate how well they think they have succeeded in performing defined values-driven behaviors and actions during training and matches. Additionally, the players should rate their perceived efforts to actually perform values-driven behaviors. Self-rated evaluations of individual values-driven behaviors could also provide a useful way to monitor athletic progression.

Finally, we recommend the use of technical devices to distribute exercises and course material, for instance by using cell phone applications with daily assignments and exercises (e.g., brief centering exercises, mindful of the breath exercise, task-focused attention exercises) and reminders when to practice.

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council for Sport Science (D2016-0037/P2016-0146).

References

- Bieling, P. J., McCabe, R. E., & Antony, M. M. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in groups. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Brinkborg, H., Michanek, J., Hesser, H., & Berglund, G. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of stress among social workers: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1, 10. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.009.

- Bühlmayer, L., Birrer, D., Röthlin, P., Faude, O., & Donath, L. (2017). Effects of mindfulness practice on performance-relevant parameters and performance outcomes in sports: A meta-analytical review. Sports Medicine, 47(11), 2309–2321. doi:10.10007/s40279-0170752-9.

- Carron, A. V., Hausenblas, H. A., & Eys, M. A. (2005). Group dynamics in sport (3rd ed.). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology

- Fabou, P. (2014). The future of post-human sports: Towards a new theory of training and winning. New York, NY: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2007). The psychology of enhancing human performance: The mindfulness-acceptance-commitment approach. New York: Springer.

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behaviour change. New York: Guildford.

- Josefsson, T., Ivarsson, A., Gustafsson, H., Stenling, A., Lindwall, M., Tornberg, R., & Böröy, J. (2018). Effects of mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) on sport-specific dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation, and self-rated athletic performance in a multiple-sport population: An RCT study. Manuscript under Review, 10(5), 6749–6755.

- Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., … Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771.

- McEwan, D., Ruissen, G. R., Eys, M. A., Zumbo, B. D., & Beachamp, M. R. (2017). The effectiveness of teamwork training on teamwork behaviors and team performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventions. PLoS One, 12, 1. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169604.

- Noetel, M., Ciarrochi, J., Van Zanden, B., & Lonsdale, C. (2017). Mindfulness and acceptance approaches to sporting performance enhancement: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1, 1. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2017.1387803.

- Sappington, R., & Longshore, K. (2015). Systematically reviewing the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions for enhanced athletic performance. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 9(3), 232–262. doi:10.1123/jcsp.2014-0017.

- Thompson, R. W., Kaufman, K. A., De Petrillo, L. A., Glass, C. R., & Arnkoff, D. B. (2011). One year follow-up of mindful sport performance enhancement (MSPE) with archers, golfers, and runners. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 5(2), 99–116.