Abstract

In this manuscript we offer an organizational or systems-led lens on psychological support for team performance. Specifically, we draw on approaches adopted within the United Kingdom (UK) high performance system to develop psychologically informed environments. In an attempt to contextualize this approach, we offer an insight into the professional landscape in the UK and the emergence of systems-led approaches. Finally, to support those responsible for advancing team performance in elite sport, we draw on the most recent practice innovations to propose the Head of Performance Environment (HOPE) role. By sharing the scope for HOPE’s roles and responsibilities, we hope to capitalize on the confluence of organizational sport psychology research developments and contemporary practice innovations and catalyze the future evolution of applied psychology in high performance sport.

In this manuscript, we offer insight into the emergence of systems-led approaches for the development of psychologically informed environments. Such approaches have been increasingly adopted by sport organizations in the United Kingdom (UK), and we offer an example from the English Institute of Sport (EIS, i.e., the Government-funded provider of science, medicine, technology, and engineering “performance support”) to illustrate. Finally, we attempt to support practitioners and those leading sport organizations by outlining the roles and responsibilities of an individual who might coordinate this systems-led delivery. Throughout, we attempt to locate this work in context and in light of the confluence of the UK performance sport landscape, scholarly origins, practice innovation, and the evolution of applied psychology. Our fundamental aim is to share these practice advances and stimulate dialogue; we do not aim to offer a “how to” guide.

As practitioners working within high performance environments, we have noticed an important distinction; working with teams is different from working within organizations because teams typically do not exist, develop, or perform in a vacuum. Rather, teams are the “front of house” representatives of sport organizations with multiple internal (e.g., board, performance support team, administrators) and external (e.g., funders, sponsors, fans, (inter)national sport federations, WADA) stakeholder groups and partners. In turn, teams are comprised of individuals, often with complimentary but varied roles and responsibilities (e.g., athletes, captains, coaches). As such, teams represent a meso-level collective within sport organizations comprised of autonomous, micro-level individuals and are influenced by macro-level organizational dynamics. It follows that psychological support to advance team performance is limited if the team is considered a separate and decontextualized entity devoid of macro-level social, cultural, or historical context and influences.

The observation that teams do not exist in a vacuum draws on a well-used metaphor (cf. Wagstaff, Citation2017) and such sentiments have become prominent and applied to a variety of areas of contemporary sport psychology research and practice. Prominent advocates of this “vacuum” metaphor tend to approach practice from a so-called systems-led approach and characterized interchangeably as working systemically and organizationally (see Fletcher & Wagstaff, Citation2009; Maher, Citation2022). By adopting a systems-led approach, practitioners aim to support the development of psychologically informed environments, where psychological concepts are widely understood, discussed, and owned by a range of stakeholders and not solely by psychology practitioners. Such approaches have gained prominence over the last decade and advising on elite sport culture, climate, and change within organizations has come to be regarded as a key function of practice (see Eubank et al., Citation2014; Green et al., Citation2020; Henriksen, Citation2015; McDougall et al., Citation2017; Sly et al., Citation2020; Wagstaff & Burton-Wylie, Citation2018; Wagstaff & Quartiroli, Citation2020). To elaborate, this evolving scope of practice requires professionals to procure the socio, cultural, and political skills and knowledge of organizational psychology practices, and to adopt a more flexible and freer ranging role at micro, meso, and macro levels of sport systems (see for an example, McKenzie et al., Citation2023). We describe this in our own practice as psychologists “working with new ways, with new people”; that is, when working with new stakeholders, at new levels of organizational hierarchy, we use new approaches and new competencies to those usually taught in training programs.

Fundamental to this approach is the practitioner conceiving the sport organization as containing multiple interconnected stakeholder groups or teams with diverse responsibilities, drivers, and dynamics, and treating this complex system, not necessarily the single individuals within, as one’s client. It follows that there may not be one single approach to supporting such systems and that each system, regardless of governance uniformity, will differ from others due to social, cultural, and historical influences. Readers first exposed to these sentiments, might ask themselves how they might locate the theoretical knowledge that could act as the foundation to developing the skills and abilities required to offer such services (i.e., What are the scholarly origins of systems-led approaches in sport?). They might also query how might practitioners help develop a psychologically informed environment within their sport organization (e.g., What are the practice origins and are there any examples of such work?), and in what role or responsibilities might systems-led practitioners hold (e.g., What does this look like as a role within a sport system?). We attempt to shed light on some of these questions in the remainder of this manuscript.

Organizational sport psychology

Organizational sport psychology (OSP) is a subfield of sport psychology that is dedicated to better understanding individual behavior and social processes in sport organizations to promote organizational functioning (Wagstaff, Citation2019, p. 1). The foundation of this subfield is the vision that effective practice is characterized by the development of sport systems that are psychologically informed, wherein people are enabled to thrive as communities of people by attending to individual, team, organizational, and systemic phenomena (cf. Wagstaff, Citation2019). The scholarly attention to OSP has resulted in programs of research spanning organizational functioning, leadership and management, stress, change, culture, resilience, sensemaking during adversity, developing thriving environments, and, to some extent, talent development environments in sport, managing abuse and duty of care practices in sport systems. The work has also begun to influence to the identity of (e.g., Wagstaff & Quartiroli, Citation2020) and professional development within the field of sport psychology (see Quartiroli et al., Citation2022). Moreover, this work has changed the policy and practice of sport organizations across professional, Olympic, and Paralympic systems (see, e.g., Fasey et al., Citation2021, Meckbach et al., Citation2023; Passaportis et al., Citation2022).

Despite the growth of empirical literature dedicated to OSP, practitioner accounts in the scholarly literature of engagement in macro-level practice have been, at best, underreported and equivocal. Yet, in recent years practitioner reflections that illuminate various cultural and climatic issues have offered rich, nascent insights (e.g., Maher, Citation2022; Ong et al., Citation2018, see also Sly et al., Citation2020). From this literature, we find interesting the descriptions of the “hats” that practitioners must wear when providing support to systems, which include: Negotiator of complex socio-political dynamics (Mellalieu, Citation2017); Navigator of complex social hierarchies, macro-/micro-politics & cultural dynamics (McDougall et al., Citation2017; Wagstaff & Hays, Citation2019), Architect of cultural excellence (Eubank et al., Citation2014) or that of a Chameleon, undertaking nested action (Collins & Cruickshank, Citation2015). Most recently, scholars have started to draw on these foundations to articulate their systems-led practice (e.g., Maher, Citation2022; Ong et al., Citation2018).

Systems-led approaches

In addition to the scholarship insights from OSP, scholars have started to describe practice innovations and articulate how they engage in systems-led practice. In the context of academy football service provision, Daley et al. (Citation2020) recently argued that adopting a systems-led approach may have a stronger chance of success over talent-development approaches they described as “owned” by psychologists (e.g., the 5Cs, Harwood et al., Citation2015; PCDEs, MacNamara & Collins, Citation2017; and the DMSP, Côté & Vierimaa, Citation2014). To elaborate, Daley and colleagues reflected that “the best programmes require craft in integration…we avoided the impression of psychology being “owned” by the psychologist, because such an approach often leads to a lack of integration and consequently short-lived impact” (p. 175). Nevertheless, current practitioners’ characterizations of systems-led approaches vary across professionals and contexts.

According to Daley et al. (Citation2020), a systems-led approach is characterized by practitioners appreciating the “big picture” and making sense of seemingly more implicit but important questions, such as “what is means to players and staff to be a part of a soccer academy?” or “what is the definition of success to players and staff in the academy?” Recently, Maher (Citation2022) outlined the nature and scope of his systems-led approach to mental health in sport as a multidimensional task across individual, team, and organizational fronts. For the purpose of this manuscript, we define a systems-led approach as a practice philosophy and process informed by systems thinking, wherein the sport organization is viewed as a complex adaptive system and is the ultimate client and focus for primary service delivery. It follows that by adopting a systems-led approach, practitioners proactively acknowledge and purposefully attend to the complexity of the sport systems. This requires practitioners to attend to the interrelationships of system parts and subgroups, seeking multiple perspectives, acknowledging temporality, performativity, and competing values, and how shifting patterns of behavior and attempts to influence system dynamics can have unintended consequences. Philosophical extensions include the recognition that individual and team behavior, dynamics, and outcomes cannot be fully understood in isolation from the whole and the acknowledgment that there are often no single solutions or best practices to perceived challenges in applied practice.

For Maher (Citation2022), adopting a systems-led approach has value for practitioners in the following ways: (a) it allows for an understanding of the interconnectedness of individual, team, and organizational levels; (b) it enables the identification of risk and protective factors that have relevance for mental health; (c) it highlights the importance of involving a range of stakeholders who can contribute to the process of fostering mental health, and; (d) it emphasizes the value of building a mentally healthy sport organization. For Daley et al. (Citation2020), the value of implementing a systems-led approach includes the development of a shared model of practice based on principles of participation and mutual learning among staff and the democratization of psychology in an organic manner. We would add that this approach can offer an integration of consultative and supportive, as well as proactive and reactive service provision. That is, where the practitioner is a part of, but apart from, the system, with the ultimate legacy being the establishment of shared ownership and collective responsibility among system stakeholders regarding psychological aspects of wellbeing and performance. Nevertheless, to realize these valued goals through a systems-led approach, there is a need for the practitioners to help the organization foster self-organizing and self-helping behavior, a degree of shared appreciation of language, needs, culture, history, and an awareness of the possible constraints and challenges that may develop as individuals try to co-create initiatives to develop a psychologically informed environment. Indeed, Daley et al. (Citation2020) noted that systems-led approaches can often bring about both value and chaos, and therefore practitioners might seek to balance the provision of careful guidance and autonomy to the system. From our own practice experience, we would agree; this work can be challenging and can often fail, leaving practitioners feeling rejected and frustrated. In our experience, the fostering a sense of collective responsibility and shared ownership of psychological language and concepts can be intimidating for those we work with, and practitioners may also face “pushback” with people arguing that “psychology is not my job.”

Conversely, the desire for a system to become psychologically aware or informed and to adopt a shared or “sticky” language around psychological constructs also requires psychologist practitioners to be vulnerable and cede “control” of psychological knowledge thereby meaningfully sharing responsibility with those in the client sport system. Practitioners must accept that individuals will begin to discuss social and psychological challenges and act as cultural architects within their own system without the involvement of the practitioner. This exclusion might be a source of anxiety, particularly for neophyte practitioners, but is, perhaps ironically, a sign of success.

Fundamentals: adopting a systems-led approach

The pillars of systems-led work will vary across practitioners and contexts, but we believe some fundamentals exist. Such work is unlikely to be framed around traditional athlete-centric “delivery” or formal psychoeducational programmes (e.g., via workshops). Instead, systems-led approaches are more likely to be characterized by processes for collective awareness raising and shared understanding through formal and informal sensemaking processes, the development of proactive initiatives that promote socially just and empathic appreciation of others, psychological flexibility, and co-creation and creative problem-solving. Such approaches will also benefit from cultural sport psychology and the situating of knowing and doing informed by local environments within a contextually-driven practice. As Schinke and Stambulova (Citation2017) noted, “the most important and influential elements from each context need to be understood in relation to the client, or organization, in advance of acting, given that people are influential and influenced products in their environment” (p. 73).

One of the main mechanisms for the implementation of systems-led approaches are mental health contributor meetings. Maher (Citation2022) outlined a 4 R model for mental health contributors to support the identification of who might contribute to a system-led initiatives. While we believe all individuals should have voice, we accept that key stakeholders will have more active involvement in the daily functioning of each sport organization. Maher’s four Rs relate to: role (what role the contributor assumes in the organization, and what part they may play, ranging from non-judgmental listening and sharing relevant information with others to the assessment of mental health challenges and illness); requirements (what the individual can contribute based on education, training and expertise); responsibilities (the activities the contributor can engage in to support the system), and; relationships (how they communicate with others and share information, including matters of confidentiality and boundaries of professional competence).

In reflecting on our own practice experience, we believe there are some key considerations when conducting mental health contributor meetings. In the UK, various systems have created versions of these meetings and each have developed different terminology. For instance, at the EIS, a range of contributor meeting formats benefit shared understanding without necessarily being formed for the purpose of developing psychologically-informed environments. These meetings are variously called “performance planning”, “individual development planning” meetings, or “MDTs” (short for “multidisciplinary team”) meetings. At Changing Minds, a major provider of psychological services within the UK, these meetings are embedded within psychological service strategy, have a deliberate psychological focus, and are typically led by a psychologist. These meetings and their associated processes are labeled “wellbeing forums,” “team formulation,” or “reflective practice groups” depending on the nuance of their purpose and scope (see Bickley et al., Citation2016). The aim of these meetings is to ascertain how those present have contributed to mental health within the system since the last meeting. Indeed, Maher (Citation2022) offered a list of questions that he recommends may serve as an agenda to scaffold the meeting: “What has been your involvement with mental health initiatives during the time since our last meeting? What would you like to report about your contributions since the last meeting? What problems or challenges are you encountering, and how are you dealing with them? What are areas we can work together on going forward? What advice and guidance can we provide to one another about our mental health involvement?” (p. 56). It is important to note that these meetings do not need to be long in duration. Instead, they will serve their purpose when they allow contributors opportunities to communicate and collaborate with each other, regardless of length.

Developing team performance in the olympic and paralympic context: a case example

For Team GB, the successful Rio Olympic cycle was bookended by high profile cultural challenges characterized by independent reviews into allegations of inappropriate behavior and systemic abuse. These crises offered leaders within the system an opportunity to reflect on the psychosocial strategy in the high performance system. During the period 2016–2022, UK Sport (UKS; the funding body for Olympic and Paralympic sport in the UK) transitioned from its successful but divisive “No Compromise” strategy to one of “Medals and More” and “Winning Well.” During this same period, a Culture, Leadership, and Talent Development team was established to advise funded sports. As part of this strategic shift, a Culture Review process was also developed to attend to culture in world-class programs (WCPs; i.e., the high performance subsystem of each national sport organization). Moreover, for the current Paris cycle, “care” has been adopted as a core value by the EIS, supplementing preexisting organizational values of Collaboration, Innovation, and Excellence. The research on OSP and the establishment of a systems-led approach has been central to the policy development and implementation of initiatives shaping this strategy shift.

Early in the Tokyo Olympic cycle, a UK Government duty of care in sport report (Grey-Thompson, Citation2017) was published which made multiple references to mental health challenges within WCPs and later in the year the first UKS culture review identified 25% of athletes as being dissatisfied with measures taken to optimize their mental health. These observations were consistent with scholarly research published throughout the Tokyo Olympic cycle, during which time a substantial body of work has emerged from around the world on mental health in sport (see for a review, Vella et al., Citation2021) and which also reflected an international shift to more holistic models of sport psychology service delivery (see Diment et al., Citation2020; Schinke et al., Citation2018). In parallel, a Mental Health Steering Group and later a Mental Health Team were assembled to deliver key components of a mental health strategy across the UK system (see Cumming et al., Citation2021). This team developed and delivered an educational program across all funded sports, training over 300 people within the system to be Mental Health Champions. Concurrently, the Culture, Leadership, and Talent Development team sought advice from sport psychologists with expertise in resilience, organizational sport psychology, and leadership and coaching to form an advisory panel. Moreover, funded programs of research have also been undertaken dedicated to culture in elite sport and inappropriate behaviors in such contexts (see Wagstaff & Burton-Wylie, Citation2018) and a desk-based review of the first four years of the culture review work was recently completed, with further iteration of UKS culture policy and practice made for the Paris cycle.

Within the UK high performance system, the EIS performance psychology team’s flagship Project Thrive strategy for the Tokyo cycle reflected an integrated whole systems approach with the aim of helping WCPs support the best version of their “performers” at the Games. This approach was also developed in response to knowledge development accrued over several Olympic cycles and in response to the shifting landscape within the high performance context alluded to above. A key strategic task was to optimize positive mental health alongside performance by increasing knowledge sharing, alignment, and access across the high-performance system. For the first time, all stakeholders - not just athletes - could access psychological and mental health support, and an organizational or system focus approach became the priority in place of the hitherto individual focus. To elaborate, using the scientific knowledge developed from lines of inquiry within OSP (see Brown et al., Citation2017; Wagstaff, Citation2017; Wagstaff & Larner, Citation2015), the vision for the EIS performance psychology team for the Tokyo cycle was, “to facilitate the creation of psychologically underpinned and sustainable high-performance environments that develop the person as well as the performer to thrive” (EIS, Citation2018).

The Project Thrive vision was approached with two key departures from traditional sport psychology practice. First, an integrated and aligned multiservice provision was conceived targeting “the system” rather than athletes as the primary client. Second, through the development of interdisciplinary teams (including performance lifestyle, mental health, performance psychology, and culture and leadership services), a holistic support strategy was developed. Here, the intention was to enable micro (i.e., individual) and meso (i.e., team) level impact through a macro (system) lens. In practice, this meant that “problematic” (Smith et al., in press) or “talented but challenging” (Bickley et al., Citation2016) individuals were not labeled within their team and discarded, as they might have in previous cycles, but efforts were made to promote a shared understanding of each individual’s story, scripts, presentation, and relational influences. The vision of the performance psychology team’s systems-led strategy was to seek to understand the person in context. Using this vision, the team developed 10 “thrive” principles that were used to frame the psychosocial service into the high performance system, while enabling practitioners to bring their own individuation to their delivery.

Gauging the impact of this work within a complex system over what remains the relative short-term is challenging, but there are some promising signs of beneficial outcomes. For instance, UK Sport’s culture review results for 2020 noted that only 11% of athletes, staff and stakeholders reported witnessing or experiencing unacceptable behaviors, compared to 24% in 2017. Moreover, 91% of over 1300 individuals surveyed in 2017 were proud to be part of their WCP, with 78% of individuals agreeing that measures had been taken to improve their mental health and wellbeing, compared with just 65% in 2018. Further, over 300 mental health champions have now been trained across the high performance system in the UK. Despite these promising outcomes, it is possible that more work needs to be done given only 48% of respondents in 2020 believed there are consequences when people behave inappropriately, which was lower than the 61% recorded in 2017. Given this regression, it is possible that work is still required to understand and address inappropriate and unacceptable behavior in the high performance system. One logical next step would be to clarify is what is meant by and perceived to be “unacceptable behavior” and “inappropriate behavior” in this context. Another possible advancement would be to clarify the processes for handling allegations of such behaviors, and unpacking the probable tensions of how any associated consequences might be managed (i.e., public or private resolution and restitution processes).

A head of performance environment? An example role and remit for systems-led working

The preceding sections offer a background to the origins of systems-led approaches and an example of this in practice in the UK high-performance system. This confluence points not only to an evolving identity for the profession (see Wagstaff & Quartiroli, Citation2020) but shifting roles and responsibilities for psychologists (see Quartiroli et al., Citation2022). In light of this observation, we now reflect on some key considerations for professionals and employers seeking to advance team performance using a systems-led approach.

The current landscape in the UK points to the existence of four workstreams that are interconnected and overlapping but not strategically aligned or coordinated, namely: performance psychology (e.g. traditionally athlete-facing work as part of the performance support team to enable them to thrive), mental health (e.g. athlete health, mental health, education, referral), performance lifestyles (e.g., athlete transitions, education, person-centered holistic needs) and environment/culture (e.g. system-facing work that focuses on the complex performance environment and uses psychological expertise to influence a range of stakeholders across the sport). We are aware of evidence of good practice where these workstreams are aligned and coordinated by one person, yet such working has not been systematically promoted or strategically harnessed. Presently, individuals with the responsibility to coordinate these four workstreams are employed in senior roles and attend or contribute to senior leadership operations (i.e., the senior leadership group within a WCP) and are typically experienced professionals (5+ years of experience).

Where a systems-led approach has been successfully adopted in the UK, we notice that a person within the WCP leads on these related workstreams and liaises with key internal (e.g., the performance support team, senior leadership team) and external (e.g., qualified mental health providers) stakeholders outside of the WCP. In other systems, organizations are at a more formative phase of this journey but have expressed a clear desire for a systems-led model. Nevertheless, there are numerous examples where an aligned systems-led approach is desired but not present, and where the work of one stream is siloed, misaligned, or duplicates the work of another. For instance, in one WCP we observed a psychologist, human resource administrator, and performance director all leading their own culture development projects largely in isolation. One cause of this duplication is the lack of clear responsibility and cross-disciplinary line management, which we believe could be given to an individual operating in a systems role (notionally, a “Head of Performance Environment” or “HOPE”). The opportunity here is the development of one strategically coordinated, aligned, and efficient approach to creating a performance-focused and person-centered psychologically informed environment. Practitioners seek to use consistent language that is easily understood, is clear on what is available and how to access it, with clearly signposted and navigable routes for advice, referral, and support. In line with this vision, systems would see services that are delivered proactively and systemically but with the capacity to react to needs as they arise. To realize this endpoint, the delivery of these services must be flexible and should be based on who is best placed and appropriately qualified to meet the needs of the individual, team, and organization.

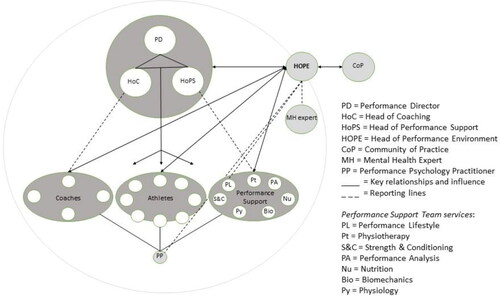

In light of the above arguments, we recommend sport organizations seek to appoint a HOPEs to coordinate the alignment of performance psychology, organizational cultural, mental health, and performance lifestyle strategies. We offer as a graphical representation of the role and argue that the remit of the HOPE should include:

Work collaboratively with senior leaders on strategic and behavior change initiative implementation and monitoring, culture development and mental health provision.

Be responsible for the overarching implementation of the performance psychology, culture, mental health, and performance lifestyle strategies.

Lead on attending to and influencing the culture within the system, focusing primarily on the performance and support teams, collaborating with key individuals across the organization as appropriate, and being accountable for implementing a culture strategy.

Help the system to understand low-level clinical psychology challenges and be responsible for liaising with mental health experts (i.e., mental health providers) to coordinate plans for athletes who have high-level clinical needs.

Work collaboratively with the people or coach development advisors and offer mentoring opportunities to leaders within the system (e.g., Performance Directors, Head Coaches, Head of Performance Support team).

Be an active member of a community of practice of other HOPEs and Heads of Performance Support to share practice and engage in a collaborative development program which places people at the center of all work.

Oversee the delivery of front-line psychology and the technical supervision of performance psychologists within the sport.

The appointment of an individual fulfilling the role and remit of a HOPE within sport systems has the potential to advance individual, team, organizational, and system functioning by creating a holistic, aligned, and systems-led approach. Yet, it follows that we, as a profession, must be able to deliver the role requirements of this position. We believe professionals need to develop an appreciation and working knowledge of advising on: the development of values-driven and psychological safe environments; social norms, subgroups and cliques; organizational issues; conflict management; organizational culture, change, and climate; leadership development and succession planning; engagement and identity; equity, diversity and inclusion; cultural sport psychology; team dynamics; multidisciplinary and team formulation; and working in and supporting complex and adaptive systems. Additionally, other areas of valuable competence development, aligned with contemporary service provision, include pressure training, supporting peers and other support staff regarding personal-professional life balance, job insecurity, extensive travel professional development, referral, self-care, psychological load monitoring, decision-making, and coach-mentoring skills (see Wagstaff & Hays, Citation2019). A cursory glance at the list above will give prospective and current trainees (and perhaps some supervisors) an indication of their preparedness to adopt a systems-led approach to working sport organizations. To supplement the development of systemic and organizational competence, for those who are not clinically trained, we would encourage all professionals to take a counseling short courses, undertake training in psychological therapy provision, and seek co-supervision from qualified mental health providers and a sport psychologist.

Conclusion

Based on our research and practice experience, we strongly believe that the development of an aligned, impactful, and coordinated systems-led approach is necessary for organizational thriving and the establishment of a psychologically informed environment. In the UK, the responsibility for this typically falls to a Performance Director or Head Coach, who’s main responsibility is the strategic leadership of the performance program and strategic leadership of the performance team. As such Performance Directors must closely monitor training and competition activity, delivery of athlete support and monitoring, training and competition schedules, selection, and preparation, and ensure that key objectives are being met and having the desired impact. Managing such responsibility and offering “world class” oversight of the performance environment is a tough ask. In our experience, while passionate about the environment of their WCP, Performance Directors and Head Coaches do not have the required capacity to optimally attend to and coordinate the development and sustenance of a psychologically informed environment.

There are several alternatives to the appointment of HOPEs. For example, the status quo would be undesirable given current psycho-social working in many high performance systems is inefficient, uncoordinated, confusing and sub-optimally impactful. An alternative senior appointment might already be within the system (e.g., the Head of the Performance Support Team) who could take on additional responsibility for developing a psychologically-informed environment. Indeed, we are aware of examples in the UK system where this has occurred, but this is an exception and largely undesirable because these individuals already have substantial line management and performance support integration and strategic demands. It is possible that more responsibility would make these individuals and, perhaps, the performance support team less impactful. Should Performance Directors continue to be viewed as the sole owner of the environment or psychology practitioners as the sole owners of psychological expertise, this would not give the various related workstreams the gravitas or coordination needed.

We acknowledge that our reflections here are heavily shaped by the sport landscape in the high performance system of the UK, which is among the best resourced and funded in the world, and as such, note that the appointment of a HOPE may be beyond the scope of some sport organizations in other Olympic, Paralympic and professional sport systems. For smaller or poorly-funded sports the appointment of a senior practitioner might be financially unviable, as in such cases we would encourage systems to consider cross-organization, national governing body, or Olympic and Paralympic Committee pooled resource and community of practice solutions. In addition to resource considerations, it is important to acknowledge other potential challenges and limitations associated with the strategic approach we have outlined here. For instance, there are well-established roles in performance sport in which individuals have responsibility for the culture and health of individuals and the WCP (e.g., Performance Directors, Heads of Performance Support or Science and Medicine). Therefore, the introduction of a HOPE into a such systems could lead to role overlap, confusion, and conflict with other senior leaders. Conversely, for reasons alluded to earlier, maintaining the status quo of individuals in established leadership roles have sole responsibility for culture and health may also lead to role overload and a lack of coordination, oversight, and prioritization of the HOPE pillars of culture, lifestyle, psychology, and mental health. To elaborate, in our experience, Performance Directors in large, complex, attritional, or decentralized programmes, have limited time and support to purposefully reflect on and influence in the cultural space of their WCP without critical friends. Another potential limitation of adopting a systems-led approach relates to the assumption that individuals will establish a degree of influence at many levels of a programme or that seeking to do so can “control” the system. The reality is that high performance sport environments are complex and often chaotic, that the work associated with the HOPE role is personally and professionally demanding, and failure in this pursuit is common. Nevertheless, while we wholeheartedly believe in the principles and pillars of the HOPE role, we also acknowledge that influence is determined by a dynamic interplay of individual and systemic attributes over time. As such, HOPEs must acknowledge and attend to the contextual, historical, relational, and cultural complexity in a system if they are to be effective in their role. Finally, we encourage individuals to be the advocates for HOPE roles or an adapted version within their own contexts; while such roles have emerged somewhat organically in the UK, this has been expedited by individuals noticing opportunities and sharing insights with other professionals, leaders, and systems. More deliberate advocacy will no doubt further accelerate this early innovation.

We hope that the present work will be of use to practitioners, current and prospective employers, and policy leaders given integration here of research and practice innovations. Given the establishment of several roles in the UK high performance system akin to the HOPE remit, with several more UK WCPs exploring the feasibility of such appointments, we anticipate a growth in the appointment of individuals with the remit of coordinating aligned systems-led approaches toward the development of psychologically informed environments in sport. We hope we have provided a valuable insight to the landscape in the UK high performance system and that our scoping of the HOPE role will stimulate discussion toward further research and practice innovation and policy change.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the following individuals and organization to aspects of the role ideas which were then developed and presented by the authors: Dr. Calum Arthur, Dr. James Bell, Sarah Cecil, Dr. Simon Crampton, Dr. Kate Hays, Paul Hughes, Dr. Katie Ludlam, Dr. Danielle Adams Norenberg, Dr. Matt Parker, Stuart Pickering, Dr. Mike Rotheram, Dr. Danielle Adams Norenberg, and The UK Sports Institute (formerly The English Institute of Sport).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Bickley, J., Rogers, A., Bell, J., & Thombs, M. (2016). “Elephant spotting”: The importance of developing a shared understanding to work more effectively with talented but challenging athletes. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 12(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2016.12.1.43

- Brown, D., Arnold, R., Fletcher, D., & Standage, M. (2017). Human thriving: A conceptual debate and literature review. European Psychologist, 22(3), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000294

- Côté, J., & Vierimaa, M. (2014). The developmental model of sport participation: 15 years after its first conceptualization. Science & Sports, 29, S63–S69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2014.08.133

- Cumming, S., Cecil, S., & Gatherer, A. (2021). Collaborative case management: Supporting mental health in the UK’s high performance sport system. In C. V. Larsen, K. Moesch, N. Durrand-Bush, & K. Henriksen (Eds.), Mental Health in Elite Sport (pp. 116–125). Routledge.

- Collins, D., & Cruickshank, A. (2015). Take a walk on the wild side: Exploring, identifying, and developing consultancy expertise with elite performance team leaders. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.002

- Daley, C., Ong, C. W., & McGregor, P. (2020). Applied psychology in academy soccer settings: A systems-led approach. In J. G. Dixon, J. B. Barker, R. C. Thelwell, and I. Mitchell (Eds.), The psychology of soccer (pp. 153–172). Routledge.

- Diment, G., Henriksen, K., & Larsen, C. H. (2020). Team Denmark’s sport psychology professional philosophy 2.0. Scandinavian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.7146/sjsep.v2i0.115660

- English Institute of Sport. (2018, July 5). Project thrive. English Institute of Sport home page. https://eis2win.co.uk/service/psychology/

- Eubank, M., Nesti, M., & Cruickshank, A. (2014). Understanding high performance sport environments: Impact for the professional training and supervision of ASPs. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 10(2), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2014.10.2.30

- Fasey, K. J., Sarkar, M., Wagstaff, C. R. D., & Johnston, J. (2021). Defining and characterizing organizational resilience in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 52, 101834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101834

- Fletcher, D., & Wagstaff, C. R. D. (2009). Organizational psychology in elite sport: Its emergence, application and future. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(4), 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.03.009

- Green, K., Devaney, D., Carré, G., Hepton, A., Wood, R., Thurston, C., & Law, D. (2020). Everything matters: The importance of shared understanding to holistically support the psycho-social needs of academy footballers. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 16(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2020.16.1.61

- Grey-Thompson, T. (2017). Duty of care in sport: Independent report to government. HMSO.

- Harwood, C. G., Barker, J. B., & Anderson, R. (2015). Psychosocial development in youth soccer players: Assessing the effectiveness of the 5Cs intervention program. The Sport Psychologist, 29(4), 319–334. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2014-0161

- Henriksen, K. (2015). Sport psychology at the Olympics: The case of a Danish sailing crew in a head wind. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2014.944554

- MacNamara, Á., & Collins, D. (2017). Psychological characteristics of developing excellence: An educationally sound approach to talent development. In: C. J. Knight, C. G. Harwood, & D. Gould (Eds.), Sport psychology for young athletes (pp. 116–128). Routledge.

- Maher, C. (2022). Fostering the mental health of athletes, coaches, and staff. Routledge.

- McKenzie, G., Wagstaff, C. R. D., & McDougall, M. (2023). Walking the middle line: Organizational culture work in sport. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2022.2155740

- McDougall, M., Nesti, M., Richardson, D., & Littlewood, M. (2017). Emphasising the culture in culture change: Examining current perspectives of culture and offering some alternative ones. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 13(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2017.13.1.47

- Mellalieu, S. D. (2017). Sport psychology consulting in professional rugby union in the United Kingdom. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 8(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1299061

- Meckbach, S., Wagstaff, C. R. D., Kenttä, G., & Thelwell, R. (2023). Building the “team behind the team”: A 21-month instrumental case study of the Swedish 2018 FIFA World Cup team. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 35(3), 521–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2046658

- Ong, C. W., McGregor, P., & Daley, C. (2018). The boy behind the bravado: Player advanced safety and support in a professional football academy setting. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 14(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2018.14.1.65

- Passaportis, M. J., Brown, D. J., Wagstaff, C. R. D., Arnold, R., & Hays, K. (2022). Creating an environment for thriving: An ethnographic exploration of a British decentralised Olympic and Paralympic sport organisation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 62, 102247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102247

- Quartiroli, A., Schinke, R. J., Giffin, C., Vosloo, J., & Fisher, L. A. (2022). Professional training and development: The bedrock of ethical, competent, and sustainable sport psychology. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 35(3), 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2043485

- Schinke, R. J., & Stambulova, N. (2017). Context-driven sport and exercise psychology practice: Widening our lens beyond the athlete. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 8(2), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1299470

- Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N., Si, G., & Moore, Z. (2018). International Society of Sport Psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(6), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557

- Sly, D., Mellalieu, S. D., & Wagstaff, C. R. D. (2020). “It’s psychology Jim, but not as we know it!”: The changing face of applied sport psychology. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 9(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000163

- Smith, M., Wagstaff, C. R. D., & Szedlak, C. (in press). Conflict between a captain and star player: An ethnodrama of interpersonal conflict experiences. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2091681

- Vella, S. A., Schweickle, M. J., Sutcliffe, J. T., & Swann, C. (2021). A systematic review and meta-synthesis of mental health position statements in sport: Scope, quality and future directions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 55, 101946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101946

- Wagstaff, C. R. D. (2017). The organizational psychology of sport: Key issues and practical applications. Routledge.

- Wagstaff, C. R. D. (2019). A commentary and reflections on the field of organizational sport psychology: Epilogue to the special issue. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1539885

- Wagstaff, C. R. D., & Burton-Wylie, S. (2018). Organizational culture in sport: A conceptual, definitional, and methodological review. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 14(2), 32–52. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2018.14.2.32

- Wagstaff, C. R. D., & Hays, K. (2019). What have the Romans ever done for us?”: Stakeholder reflections on 10 years of the Qualification in Sport and Exercise Psychology. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 15(2), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2019.15.2.32

- Wagstaff, C. R. D., & Larner, R. J. (2015). Organisational psychology in sport: Recent developments and a research agenda. In S.D. Mellalieu and S. Hanton (Eds.), Contemporary advances in sport psychology (pp. 91–119). Routledge.

- Wagstaff, C. R. D., & Quartiroli, A. (2020). Psychology and psychologists in search of an identity: What and who are we, and why does it matter? Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 11(4), 254–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2020.1833124