Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to explore the athletic and career transitions that student-athletes navigate and to present examples of providing ongoing psychological support for student-athletes through these transitions. Guided by frameworks for understanding athlete change-events, a series of evidence-based propositions are presented to conceptualize how to understand and support collegiate student-athletes through transitions. A specific educational program is explained to provide an example of supporting student-athletes’ goal setting, identity, and life skills transfer during the transition out of college sports and college life. Future opportunities for supporting student-athlete transitions are then identified, along with reflections and lessons learned on how to provide ongoing psychological support to collegiate student-athletes.

In the United States, over 520,000 participate in college athletics across three NCAA divisions (National Collegiate Athletic Association, Citation2022). College athletics is considered to be an elite level of sport participation in many sports and the pinnacle in the career for many young people. Athletes in the collegiate system are known as student-athletes due to their dual commitment to their academics and sport. There is controversy over the term student-athlete and the amateur status of some athletes, particularly in revenue-generating sports. Regardless, there is no contention about the high expectations and challenges that all student-athletes must navigate between the ages of 18 to 23. The purpose of this paper is to explore the major athletic and career transitions that most student-athletes navigate and to present examples of providing ongoing psychological support for student-athletes through these transitions.

Athletic and career transitions for college student-athletes

There are many dimensions (i.e., athletic, psychological, psychosocial, academic & vocational, financial, and legal) influencing the holistic development process of sport participants (Wylleman, Citation2019). Within each dimension, individuals progress through stages of change and experience transitions as a process as opposed to a single, abrupt event (Samuel et al., Citation2020). In the United States, two major transitions stand out as common across high-performing college-aged athletes.

At the age of 18-19 years old, individuals encounter their first transitional process as they enter college sport and college life. During this transition, student-athletes experience significant individual and environmental changes (Henriksen et al., Citation2023). Specifically, individuals move psychologically from early adolescence to late adolescence, socially from living at home to new independent college living, academically from secondary to higher education (i.e., junior college or college), and athletically from the development stage to the mastery level of their sport (Wylleman, Citation2019). The transition from high school to college requires student-athletes to integrate into a new social and cultural environment, often moving from being ‘a big fish in a small pond’ to being ‘a small fish in a big pond’ (Pierce et al., Citation2021). Woltring et al. (Citation2021) interviewed 23 male and female student-athletes making the transition into Division I college athletics. The study found that student-athletes’ pre-transition expectations did not match the reality of their new athletic and academic life as they entered college. Student-athletes experienced new coach-athlete relationships and perceived higher expectations from coaches with new, high-stress practice environments. Student-athletes perceived a lack of support through new challenges encountered during their transition. Ultimately, student-athletes entering college need to balance new demands on their time, energy, and resources to successfully transition to their new academic, athletic, and social domains (Gayles & Baker, Citation2015).

Second, as only approximately three percent of college athletes proceed to the professional level, college graduation represents the second major transition for student-athletes to life after formal, competitive sport (National Collegiate Athletic Association, Citation2024). This age (22–23) similarly represents critical individual and environmental transitions with psychological progression from adolescence to adulthood, academically transitioning from higher education to professional careers, and most likely the end of their athletic career (Wylleman, Citation2019). To investigate this transition, Manthey and Smith (Citation2023) interviewed 11 female student-athletes graduating from a Division I university about their experiences and perceptions of this transition. Student-athletes identified several challenges including the stress of the transition, physical changes, losing their athlete identity, and a sense of loss. For these individuals, it was concluded that the transition to life after college sport should be considered a grieving process for student-athletes.

To understand and support student-athletes through these transitions, the Integrated Career Change and Transition Framework (ICCT) (Samuel et al., Citation2020) provides insightful scientific and practical guidance. The ICCT suggests that the transition process begins with a career change-event (e.g., transitioning into or out of college sport) that initiates a pre-transition situation. Prior to, or during the transition, athletes are faced with a variety of transition demands (e.g., athletic, psychological, social, academic/vocational, financial, and cultural). During this time, athletes should initially appraise these demands, assess their available resources and potential barriers, and make a strategic decision to respond to this career change-event. The ICCT highlights specific opportunities for athletes to consult with others, such as a sport psychology consultant, during the transition to help athletes process the demands, resources, and barriers inherent in their own unique situation.

During this second appraisal, this support can encourage athletes to make decisions to change, actively invest and implement coping strategies, and experience a positive transition. Alternatively, leaving athletes to ignore or avoid transition decisions or to cope alone, can leave them without support and lead to negative transition outcomes (Samuel et al., Citation2020). As transitions represent an opportunity for “active coping with a specific set of demands” (Stambulova & Samuel, Citation2020, p. 119), it is critical that collegiate student-athletes are provided with ongoing psychological support to navigate their introduction into and eventual exit out of the athletic environment.

Programs to support college student-athletes through transitions

Based on this growing understanding of how athletes experience and navigate athletic and career transitions and the psychological development of athletes, our work has been guided by six key evidence-based propositions for supporting college student-athlete transitions. This set is not intended as an exhaustive list of guidelines that must be followed, rather they have been used by our team as guiding principles about when and how to develop programming to provide psychological support through the ongoing transitions for college student-athletes. First, two notable change-events are experienced by all student-athletes (i.e., the transition into college athletics and the transition out of college athletics) creating demands that can disrupt student-athletes’ psychological, athletic, and academic experiences (Samuel & Tenenbaum, Citation2011). Second, crisis-prevention educational programs can be beneficial to help athletes identify transition demands, provide supportive people to consult with, and equip them with the tools necessary for effectively navigating the demands of the transition (Samuel et al., Citation2020; Stambulova, Citation2003). Third, it is optimal to increase a multidimensional identity and decrease exclusivity elements of their athletic identity to support student-athletes through their sport and life change- events (Samuel et al., Citation2023). Fourth, teaching athletes to appraise transition challenges as opportunities for growth and teaching coping skills to navigate athletic and career transitions will facilitate success in sport and other life domains (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016; Samuel & Tenenbaum, Citation2011). Fifth, athletes should be guided to enhance their awareness, confidence, and motivation in transferring life skills learned during sport, and actively identify opportunities and support for transferring these life skills beyond sport (Pierce et al., Citation2017). Finally, continuity of psychological support through the ongoing transitions will help student-athletes apply challenge appraisal, resilience, and life skills when needed (Stambulova & Samuel, Citation2020).

Guided by these general propositions, our team has created and delivered two educational programs to support collegiate athletes’ transitions into and out of college. First, the “Resilience for the Rocky Road” program focuses on the career change-event of the transition from high school into their first year of college (see Pierce et al., Citation2021). This program helps student-athletes identify and appraise transitional demands and focuses on the development of personal qualities (i.e., identity, coping skills, social support, leadership) for resilience (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016) and life skills transfer (Pierce et al., Citation2017). The program has been delivered to approximately 400 first-year student-athletes at two NCAA Division I institutions throughout their first semester in college. Athletes who went through the program maintained their psychological resilience during this challenging transition and reported that they used their coping skills, social support networks, and leadership skills that they learned during the program (see Pierce et al., Citation2021). Second, the “Life After Sports” program provides psychological support to student-athletes during the transition out of college. The next section of the paper will provide an overview of the Life After Sports program design, learning objectives and tasks, program modalities, and initial evaluation to provide another example of providing ongoing psychological support for student-athletes through key transitions.

The Life After Sports program: supporting the transition out of college athletics

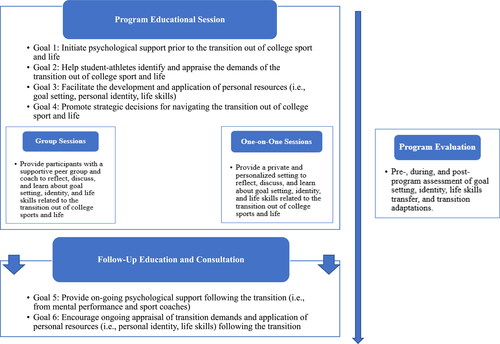

The Life After Sports program design aligns with key elements of the ICCT (Samuel et al., Citation2020; see ). The program focuses on the transition out of college sport and life as the career change-event, with goals to (1) initiate psychological support prior to the transition out of college sport and life; (2) help student-athletes identify and appraise the demands of transition out of college sport and life; (3) facilitate the development and application of personal resources (i.e., goal setting, personal identity, life skills); (4) promote active strategic decisions and decisions to change for navigating the transition out of college sport and life; (5) provide on-going psychological support following the transition (i.e., from mental performance and sport coaches); and (6) encourage ongoing appraisal of transition demands and application of personal resources (i.e., personal identity, life skills) following the transition.

From a pedagogical perspective, the implementation of the program is guided by two counseling frameworks. First, a humanistic approach is used to develop person-centered content, encourage individuals to live in the ‘here and now’, cultivate a relational base, and guide participants to confidently make their own growth-enhancing choices (Tod & Wadsworth, Citation2023). Second, a life skill coaching approach encourages individuals to gain awareness and confidence to apply psychological and social skills gained from sport to other life contexts (Conley et al., Citation2010; Pierce et al., Citation2017).

Program participants

To date, this Life After Sports program has been delivered to graduating student-athletes at one Division I university (Illinois State University) and one Division III university (Illinois Wesleyan University) in the United States. At each university, graduating student-athletes were emailed information about the program and voluntarily elected to participate approximately two months prior to graduation. For student-athletes, this was after or within two months of the conclusion of their final season as a college athlete.

Program content and delivery

The content of the Life After Sports program includes one primary educational session, follow-up education, and ongoing consultation. This section will describe the content of the program and explain the delivery of the program using both group and one-on-one approaches.

Program educational session

The Life After Sports program was designed around specific learning objectives and learning tasks to achieve the first four program goals (see ). The first objective was for participants to effectively set goals to facilitate growth and behavior change beyond sport (Whitmore, Citation2009). At the beginning of the session, participants completed the 16-item GROW model series of questions (Whitmore, Citation2009). The purpose of the questioning was to coach participants in exploring their goal for the transition (e.g., What do you want to achieve?), the reality of their transition demands (e.g., What have you done so far to reach this goal?), their options for navigating the transition demands (e.g., What could you do as the next step in reaching this goal?), and ask what will they do (e.g., What will you do tomorrow toward achieving your goal?) in life beyond college sport and college life. The questions were narrated one at a time to ensure that participants “ink it and not just think it”, writing down responses to encourage deeper processing.

The second objective was for participants to create a balanced and multidimensional self-identity as early as pre-retirement (Park et al., Citation2013). Participants were presented with 10 cue cards and instructed to write down a single identity dimension on each card, ensuring that the “athlete” role was included as one card. Participants ranked the identities in terms of importance and were then instructed to rip up the “athlete” role card. The action of ripping the card symbolized retirement as a way to elicit the feelings, reflections, and thoughts associated with that experience. Participants were then asked to choose their top three identities that were most meaningful to them (e.g., future nurse, brother, hardworking) and explain how those identities shape their actions, behaviors, and experiences in relation to their transition demands. Participants were reminded to continue valuing being an athlete while also being encouraged to appraise and discuss the “athlete” role as one of many aspects of their overall identity.

The third objective was to identify life skills they developed from college sport and enhance awareness, confidence, and opportunities for transferring life skills learned from college sport (Pierce et al., Citation2017). As part of the orientation to the Life After Skills program, student-athletes completed the Life Skills Scale for Sport—Transfer Scale (LSSS-TS; Mossman et al., Citation2021). Based on the survey results, a “life skills profile” was created for each participant, representing their scores from the LSSS-TS and skills they believed they developed through sport. Participants were presented with their ‘life skills profile’ in the session and asked to write down and verbally: (1) describe how and why they believed that they developed these skills; (2) identify opportunities and situations for applying these life skills as they navigate their transition demands; (3) and explain “who they want to be” in a year beyond the session (i.e., I am/I will…).

Follow-Up education and consultation

Following the program educational session, two additional objectives and activities were prioritized to provide ongoing support for student-athletes through the transitions (see ). First, at the time of their college graduation (approximately one month following the program’s main session), a video message was sent from coaches and administrators in their athletic department. This was designed to provide ongoing psychological support following the transition from their sport coaches during the transition beyond college sport. Coaches provided congratulatory and good luck messages, validated ongoing transition demands, promoted a balanced identity, reflected on key life lessons and life skills that could be transferred from sports, and reminded participants of the ongoing social support from their home university.

Second, approximately two months post-graduation, participants engaged in a follow-up one-on-one session with a mental performance coach. This session was designed to provide ongoing psychological support for participants following their graduation and encourage ongoing appraisal of transition demands and application of personal resources following the transition. Utilizing the humanistic and life skills counseling approaches, this session was designed to help participants continue to appraise, discuss, and make strategic decisions about their transition demands and goal setting, identity, and life skills transfer beyond college sport and life (Samuel et al., Citation2020).

Program delivery

To assess the variations in the impact of this educational programming on student-athletes and their transition, the primary educational session has been delivered using two different pedagogical modalities. The first modality was a one-hour group program educational session and a 30-minute follow-up one-on-one session for each participant. The group approach was designed to provide participants with a supportive peer group and trained mental performance coach to reflect, discuss, and learn about goal setting, identity, and life skills related to the transition out of college sports and life. The second modality was a 45-60 min one-on-one educational session and a 30-minute follow-up one-on-one session for each participant. These one-on-one sessions were facilitated by a trained mental performance coach, and provided a private and personalized setting to allow reflection, discussion, and learning about goal setting, identity, and life skills related to the transition out of college sports and life. In the educational session for both modalities, participants completed written activities on their own and then participated in discussions (group or one-on-one) to encourage appraisal, learning, and application of resources to life beyond college sport.

Participation in the program has been optional for graduating student-athletes. At the Division III university, the first program modality (group) was offered to all graduating student-athletes during the 2022-23 academic year. Out of approximately 95 invited participants, a total of 15 individuals volunteered to complete the program, with one group session delivered. Participants represented a variety of different sports such as basketball, football, lacrosse, soccer, softball, swimming, track & field, and volleyball. Then, during the 2023–24 academic year, the second modality (one-on-one) was offered to all graduating student-athletes. Out of approximately 100 invited participants, a total of 14 individuals volunteered to complete the one-on-one programming. Participants represented a variety of different sports such as basketball, bowling, golf, lacrosse, softball, tennis, track & field, and volleyball. At the Division I university, the first program modality (group) was offered to graduating student-athletes on six teams during the 2023–24 academic year. Out of approximately 60 invited participants, a total of seven individuals volunteered to complete the program, with two group sessions delivered. Participants represented different sports such as golf, softball, and track & field.

Program assessment and participant feedback

Prior to, during, and at the completion of the Life After Sports program, participants have completed a series of validated surveys and interviews to assess the objectives of the program and their adaptation throughout their transition. This data will not be presented in this paper. However, valuable insights can be gained from participant perceptions of their transition and educational experience. Specifically, initial program feedback has highlighted four program strengths and two areas for improvement.

Program strengths

First, student-athletes believed that the program offered applicable and relevant content for the immediate transition demands. One participant stated: “I remember we did the goal setting…and I feel that helped me to think about what I was doing after graduation and plan for it and kind of prepare for the obstacles that I would have.” Second, student-athletes believed the program prompted self-reflection and appraisal of demands. One said “when you guys had us rank where athlete is on our identity…that made me think about what I want my identity to be like. I obviously want athlete to be a part of it, but I wouldn’t want it to be one of my top things.” Third, the value of ongoing support was recognized. During the follow-up session, an athlete stated “I'm glad that I went because now I like meeting up with you so that we could talk about the workshop and have you give feedback.” The athlete continued, “I think about that day and how I was struggling then. Now, I'm not even really worried about my athletic identity.” Finally, for the group participants, the program provided a valuable shared learning experience: “in the moment, it made me more comfortable, it made me more… comfortable to transition out, knowing that people were feeling kind of similar to how I was.”

Areas for improvement

Student-athletes suggested that the program could improve its potential impact. First, having more targeted recruitment or mandatory participation for graduating student-athletes was recommended. As less than 15% of invited participants have selected to participate in the programming, this appears to be a pertinent recommendation. One reflection and suggestion emphasized, “I wish more people would have come [to the session] because the people who didn’t go needed it…there are people that I know who are struggling with who they were as athletes and who they are now.” Second, expanding the focus on holistic personal development was suggested by a participant following their transition: “the importance of nutrition hit home a lot harder [following graduation]. So maybe just giving a heads up like, ‘your body may change, don’t be surprised.”

Future programmatic directions and recommendations

Through our experiences of delivering educational programming for student-athletes in transition, specific ideas for future programming have emerged alongside recommendations for effectively supporting student-athletes.

Supporting transfer and international student-athletes

With the dynamic landscape of college athletics, two additional transitional change-events present opportunities for programming to provide psychological support for student-athletes. First, NCAA student-athletes are transferring between institutions at a drastically increasing rate. In 2022, over 30,000 Division I and II student-athletes attempted to transfer to another university and athletic program with seven percent of all Division I student-athletes successfully transferring (National Collegiate Athletic Association, Citation2023a). This trend highlights a third change-event (Samuel & Tenenbaum, Citation2011) in the ongoing transitions for collegiate student-athletes and creates new ecological challenges for individuals as they acclimate to a new athletic and academic setting (Henriksen et al., Citation2023). As such, practitioners are, and should be, developing new crisis-prevention programming to support student-athletes with their multidimensional identity, challenge appraisal, resilience and coping skills, and the transfer of life skills through the transfer transition.

Second, international participants represent approximately 13% of Division I and seven percent of the Division II student-athletes (National Collegiate Athletic Association, Citation2023b). International student-athletes experience unique and additional stressors and challenges as they transition into college athletics (i.e., the process of acculturation with new values and language; Pierce et al., Citation2011) and out of college athletics (i.e., immigration requirements, employment limitations). Support staff in college athletics have an obligation to adopt a cultural praxis to have cultural awareness and humility in relation to international student-athletes’ transitions, work with university international offices to support student-athletes through their cultural adjustment, and gain a holistic and ecological understanding of the unique differences and changes in athletics and academics that international student-athletes may experience (Samuel et al., Citation2020).

Providing engaging and interactive programming

From a pedagogical perspective, we have used a wide variety of modalities and approaches in an attempt to help student-athletes appraise, learn skills, and apply knowledge through their ongoing transitions. Consistent in each of these modalities is the challenge to motivate student-athletes, who lead busy lives, to actively engage in reflection and learning about their transitions. Recent evaluative feedback has highlighted three key pedagogical recommendations. First, participants in group sessions consistently reflect on the value of the shared learning experience (e.g., group discussions and collaborative learning) and are provided with a safe and comfortable environment to listen, learn, and connect with their peers who are experiencing similar transitions. Second, individualizing program content (e.g., personalized life skills profiles; personal identity cards) is key to helping enhance the depth of athletes’ reflection and appraisal of their transitions and resources. Third, gamifying learning (i.e., adding game design) into student-athlete workshops has been embraced by participants. For example, using a “Family Feud” style game approach to help student-athletes’ appraise stressors and learn emotional regulation strategies has been found to satisfy the desire for competition and increase their enjoyment and emotional connection to the content. We encourage other practitioners to consider both individual and group-based approaches when considering how to best deliver content to collegiate athletes who might be overscheduled, and short on time, yet still interested and in need of the content.

Maintaining contact and support over time

As a career transition is an ongoing process as opposed to a singular, abrupt event (Samuel et al., Citation2020), it is critical that psychological support is viewed as an ongoing process and not a singular, abrupt event. One-time workshops or a series of workshops are seen as the bare minimum in supporting student-athlete transitions. The Life After Sports program was designed to provide ongoing psychological support for student-athletes with mental performance coaches. While these objectives were possible for a small sample of athletes, this is a logistical challenge for athletic departments that are understaffed from a mental health and mental performance staff standpoint and often have little contact with athletes’ post-graduation. If student-athlete long-term psychosocial outcomes are a focus for college athletic departments, they must continue to find innovative ways to stay connected with their retiring student-athletes and maintain interest and support for life beyond sport.

Additionally, a deliberate and unique feature within our programming was the involvement of coaches to help share messages of encouragement for appraisal of transition demands and skill application. With our programs and in similar programs, we advocate that coaches should be educated on how to help their athletes develop balanced identities, appraise transition demands, develop coping skills, and plan for life skills transfer to position athletes for successful transitions out of college. Student-athlete transition programming should seek to integrate elements of nutrition and physical activity (e.g., Reifsteck & Brooks, Citation2018) to further support a holistic focus on personal development.

Conclusion

In an ever-changing collegiate athletic environment in the United States, one thing is constant. Student-athletes are experiencing and navigating an ongoing series of psychological, athletic, and career transitions. This paper explored the athletic and career transitions that student-athletes navigate and presented examples of providing ongoing psychological support for student-athletes through these transitions. The Resilience for the Rocky Road program is an example of opening the door to support collegiate athletes and the Life After Sports program demonstrates how to keep that door open for support even in their post-athletic careers. To optimize their psychological support for athletes, practitioners need to open the door and keep it open!

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Conley, K. A., Danish, S. J., & Pasquariello, C. D. (2010). Sport as a context for teaching life skills. In D. Tod & K. Hodge (Eds.), Routledge handbook of applied sport psychology (pp. 168–176) Routledge.

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: An evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7(3), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2016.1255496

- Gayles, J. G., & Baker, A. R. (2015). Opportunities and challenges for first-year student-athletes transitioning from high school to college. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2015(147), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20142

- Henriksen, K., Stambulova, N., Storm, L. K., & Schinke, R. (2023). Towards an ecology of athletes’ career transitions: Conceptualization and working models. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–14. Advanced Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2023.2213105

- Manthey, C., & Smith, J. (2023). “You need to allow yourself to grieve that loss and that identity.” College athletes’ transition to life after college sport. Journal of Athlete Development and Experience, 5(1), 16–38. https://doi.org/10.25035/jade.05.01.02

- Mossman, G. J., Robertson, C., Williamson, B., & Cronin, L. (2021). Development and initial validation of the Life Skills Scale for Sport – Transfer Scale (LSSS-TS). Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 54, 101906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101906

- National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2022). NCAA student-athletes surpass 520,000, set new record. https://www.ncaa.org/news/2022/12/5/media-center-ncaa-student-athletes-surpass-520-000-set-new-record.aspx

- National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2023a). 2022 transfer trends released for divisions I and II. https://www.ncaa.org/news/2023/2/21/media-center-2022-transfer-trends-released-for-divisions-i-and-ii.aspx

- National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2023b). International student-athlete participation. https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2018/3/21/international-student-athlete-participation.aspx

- National Collegiate Athletic Association (2024). Estimated probability of competing in professional athletics. https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2015/3/6/estimated-probability-of-competing-in-professional-athletics.aspx

- Park, S., Lavallee, D., & Tod, D. (2013). Athletes’ career transition out of sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 22–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2012.687053

- Pierce, S., Gould, D., & Camiré, M. (2017). Definition and model of life skills transfer. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 186–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1199727

- Pierce, S., Martin, E., Rossetto, K., & O’Neil, L. (2021). Resilience for the rocky road: Lessons learned from an educational program for first year collegiate student-athletes. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 12(3), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2020.1822968

- Pierce, D., Popp, N., & Meadows, B. (2011). Qualitative analysis of international student-athlete perspectives on recruitment and transitioning into American college sport. The Sport Journal, 14(1), 36–47. https://thesportjournal.org/article/category/sports-management/page/26/

- Reifsteck, E. J., & Brooks, D. D. (2018). A transition program to help student-athletes move on to lifetime physical activity. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 9(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1303011

- Samuel, R. D., Stambulova, N., & Ashkenazi, Y. (2020). Cultural transition of the Israeli men’s u18 national handball team migrated to Germany: A case study. Sport in Society, 23(4), 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1565706

- Samuel, R. D., Stambulova, N., Galily, Y., & Tenenbaum, G. (2023). Adaptation to change: A meta-model of adaptation in sport. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–25. Advanced Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2023.2168726

- Samuel, R. D., & Tenenbaum, G. (2011). The role of change in athletes’ careers: A scheme of change for sport psychology practice. The Sport Psychologist, 25(2), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.25.2.233

- Stambulova, N. (2003). Symptoms of a crisis-transition: A grounded theory study. In N. Hassmén (Ed.), SIPF yearbook 2003 (pp. 97–109). Örebro University Press.

- Stambulova, N. B., & Samuel, R. D. (2020). Career transitions. In D. Hackfort & R. Schinke (Eds.), The Routledge international encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology (pp. 119–134). Routledge.

- Tod, D., & Wadsworth, N. (2023). Person-centered therapy. In D. Tod, K. Hodge, & V. Krane (Eds.), Routledge handbook of applied sport psychology: A comprehensive guide for students and practitioners (2nd ed., pp. 154–162). Routledge.

- Whitmore, J. (2009). Coaching for performance: Growing human potential and purpose: The principles and practice of coaching and leadership (4th ed.) Nicholas Brealey.

- Woltring, M. T., Hauff, C., Forester, B., & Holden, S. L. (2021). "I didn’t know how all this works": A case study examining the transition experiences of student-athletes from high school to a mid-major DI program. Journal of Athlete Development and Experience, 3(2), 128–149. https://doi.org/10.25035/jade.03.02.04

- Wylleman, P. (2019). A developmental and holistic perspective on transiting out of elite sport. In M. H. Anshel, T. A. Petrie, & J. A. Steinfeldt (Eds.), APA handbook of sport and exercise psychology: Sport Psychology (pp. 201–216). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000123-011