ABSTRACT

Why do Islamist parties succeed electorally? Some scholars posit that Islamists’ success stems from their ability to institutionalize constituent relations and serve marginalized citizens. I test this hypothesis using an original survey of 782 Algerian citizens focusing on constituency service interactions with legislators. I argue and show empirically that Islamist parties’ more institutionalized constituency service practices allow them to reach citizens outside of their existing networks and those from groups that are marginalized from patronage networks with the state (e.g. women) to a greater extent than non-Islamist parties. By offering evidence of Islamists’ responsiveness to citizens from diverse backgrounds, this study suggests that authoritarian states’ reliance on clientelism leaves them vulnerable to challenges by opposition movements that can mobilize around religion and serve as intermediaries for citizens.

Introduction

A growing body of literature interrogates why Islamist parties – and other opposition parties – succeed electorally.Footnote1 Most research finds that religious appeals and citizen piety are important, but that economic factors, in the form of economic policy platforms and paid service provision, are also crucial. Mesoud argues that Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood mobilized support by articulating a new political economic vision for the poor after President Hosni Mubarak was ousted in 2011.Footnote2 Brooke argues that the Muslim Brotherhood was successful, not through clientelism, but by providing high-quality paid medical services to the middle classes through its clinics.Footnote3 Others argue that, due to its greater party organizational capacity, Ennahda provided more constituency service than other parties and was more successful in attracting new supporters in Tunisia’s transitional elections.Footnote4

But, the role of clientelistic appeals and constituency service provision in electoral mobilization by Islamist parties has been explored in only a few cases. No existing studies test the impact of Islamist party identification on constituency service provision in Algeria, the Arab country which held the first free and fair election in the Arab world (1989–1991). Algeria’s military canceled the results of the first-round legislative elections in 1991, outlawing the Islamic Salvation Front.Footnote5 By 1997, new Islamist parties, including the Movement for Society and Peace (MSP, formerly HAMAS) and Islah (Islamic Resistance Movement), competed in elections, winning some 23.5% of seats in the lower Chamber of Representatives.

Leveraging original data from a survey of 782 Algerian citizens conducted in 2007, this study is the first to systematically compare constituency service practices across Islamist and non-Islamist parties in Algeria, and to do so across municipal, provincial, and national legislatures. I argue and empirically show that Islamists’ greater party capacity and more institutionalized constituency service practices allow them to reach more citizens outside of their existing networks and those from groups that are relatively marginalized from patronage networks with the state (e.g., women).

These findings offer several implications for existing literature. First, they extend the literature on Islam and politics by suggesting that Islamist parties’ institutional capacity allows them to reach a broader cross-section of society beyond those who are already in their networks. More than members of Islamist parties, legislators from non-Islamist parties provide constituency service within closed networks of citizens they already know through their family, party, or business activities. While Islamist parties do not always win elections, the evidence suggests that constituency service plays a role in their ability to mobilize voters in clientelistic contexts.

Second, the findings complement and extend the literature on Islam, gender, and politics by offering evidence that Islamist parties reach groups that are marginalized from existing networks with political elites – in this case, women. This suggests that clientelism,Footnote6 not religion most hinders women’s representation, at least in so far as clientelistic responsiveness of elected officials is concerned.Footnote7

Finally, the results have implications for literature on authoritarian politics by suggesting that authoritarian states’ reliance on patron-client relationships leaves them vulnerable to challenges by opposition movements when they can mobilize support among marginalized groups. Yet they also illustrate possible impacts of regime strategies to co-opt opposition by offering them a share in the spoils.Footnote8 In Algeria, because the Islamist Movement for Society and Peace (MSP, formally HAMAS) joined the governing coalition and maintained more cooperative relationships within the regime, it had more success reaching citizens with services than the Islamist party, Islah, which remained outside the coalition.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, I conceptualize constituency service within the context of a clientelistic political setting. Second, I lay out the Algerian political electoral context. Third, I set up the theory and hypotheses and provide descriptive statistics. Finally, I outline the results and discuss the conclusions and implications of the research.

Conceptualizing clientelistic responsiveness

Legislatures in authoritarian regimes lack independent lawmaking power. But their members receive a large volume of requests from citizens for help with personal and community problems.Footnote9 In the context of authoritarianism and weak rule of law, government services and access to employment in the public and private sector are often distributed through informal networks. This makes clientelism essential for ordinary citizens to interact with the bureaucracy and gain access to the services that they need. Members of Parliament, as well as state and local legislators, are some of the public and private individuals who may serve as an intermediary to help citizens access services, jobs, or money to meet their needs.

Clientelism (i.e., patron-client relations) refers to a relationship between two parties of unequal status, in which the patron controls the resources that the client needs, but where both parties benefit.Footnote10 A patron can be a public official or a private citizen – anyone with the interest and ability to help with a specific problem, such as obtaining government documents, securing a hospital bed, or finding a job in exchange for status, a favor, or electoral support. In the Arab world, this practice is referred to as wasta (using connections, an intermediary) in Modern Standard Arabic. It is also known through such terms as piston (Fr. booster) or ktef (Ar. shoulder, referring to military stars, or clout) in the Algerian context. Wasta is a social practice through which loyalty to family, tribe, religion, and sect is used to achieve mutually beneficial exchanges of interests.Footnote11

Legislators who help citizens with personal or community problems are offering constituency service. Yet there are important differences between constituency service in democratic and authoritarian regimes. In democracies, service responsiveness (i.e., constituency service) is a form of democratic representation, governed by the rule of law.Footnote12 Citizens in democracies approach members or the representatives’ staffs for help, but this assistance is provided within the context of the law (e.g., when the citizens are legally entitled to a public benefit they are not receiving). In a democracy, citizens’ requests may reveal a bureaucratic mistake or other problem that can be improved through legislation. In an authoritarian regime, a citizen may receive a service to which they are entitled but are being denied due to bureaucratic inefficiency or being asked for a bribe. But they may also be asking for preferential treatment, which is necessary due to a corrupt and clientelistic bureaucracy and a job market in which informal relationships are needed to receive services. Parliamentary clientelism (i.e., clientelistic responsiveness)Footnote13 differs from constituency service in that citizens access it based on an informal relationship with a wasta or intermediary. Often, it is the lack of rule of law that creates the need to ask for help.

Yet, without the ability to use clientelism, whether from a legislator or another type of patron, the poor and marginalized often have few avenues for protection from corruption or access to vital services. Blaydes and El TaroutyFootnote14 argue that clientelism empowers women by providing opportunities to sell votes for a future payoff, or gain protection from state repression by voting for the opposition. The author’s qualitative interviews in Morocco and Algeria (2004–2014) reveal cases of abuse; but most parliamentary clientelism is motivated by electoral incentives and social obligation. As put by one Moroccan Member of Parliament who left during an interview about constituency service, “I must be present with citizens” to be reelected.Footnote15

Yet, clientelistic responsiveness is not the same as constituency service within a model of good governance.Footnote16 Citizens are empowered by attention from officials who can help them, but clientelistic responsiveness also strengthens the norm that personal networks are needed to gain services that citizens are otherwise entitled to while excluding those who qualify for services but do not have the connections to obtain them. Access to services in exchange for loyalty without the right to demand accountability makes the practice problematic. Parliamentary clientelism is the antithesis of accountability because elites lack any incentive to reform the bureaucratic inefficiency, as inefficiency itself makes them indispensable.Footnote17 Regime incumbents wield some control over who wins elections; thus, parliamentarians must maintain good relationships within the state to solve their constituents’ problems. According to a Moroccan Islamist parliamentarian, “I do not provide services because I spoke out. Now I can’t help citizens.”Footnote18 This response indicates that the parliamentarian feels that he cannot challenge regime incumbents or risk having poor relationships in the bureaucracy, hindering his ability to help his constituents resolve their problems.

Legislative elections under authoritarianism in Algeria

Constituency service has been the subject of significant inquiry in democratic settings, where researchers primarily focus on its role in building the personal vote and mobilizing voters.Footnote19 In nondemocracies, few studies explain why some parties or members provide more constituency service, and to whom.

Political context

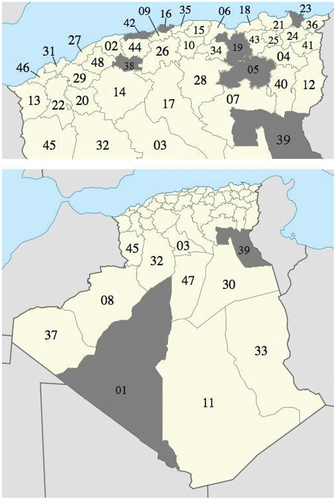

An authoritarian, single party dominant regime, Algeria holds semi-competitive elections for legislative assemblies and the presidency. Legislative elections take place by universal suffrage for five-year terms for its National Popular Assembly (L’Assemblée Populaire Nationale, APN), which had 389 seats as of the 2002–2007 mandate; 48 regional assemblies (Popular Assembly of the Wilaya or L’Assemblée Populaire du Wilaya, APW); and 1,541 municipal assemblies (Popular Assembly of the Commune or L’Assemblée Populaire Communale, APCs). The electoral system is closed-list proportional representation in multi-member districts, and the electoral districts for the APN were also the country’s 48 provinces (wilayat; ), in addition to eight overseas seats. The upper house of parliament (i.e., Senate) is partially elected, with 48 seats appointed by the president and 144 seats indirectly elected by the APWs.

Figure 1. Algeria has forty-eight administrative districts called wilayat (plural of wilaya). The survey was conducted in eight districts, identified by their official numbers: Adrar (1), Batna (5), Algiers (16), Sétif (19), Annaba (23), Tissemsilt (38), El-Oued (39), and Tipaza (42). Wikipedia, “List of Algerian provinces by population,” last modified May 17, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Algerian_provinces_by_population.

The institutions of the presidency, the legislative branch, and the judiciary are referred to as a democratic façade, behind which unelected elites wield considerable power. Military, intelligence, and business elites influence decision making in crucial policy areas.Footnote20 President Bouteflika (replaced in 2019 by President Tebboune) enjoyed unprecedented success increasing the power of the presidency; yet, powerful, unelected military elites and intelligence services known as “les décideurs” or “le pouvoir” (“decision-makers” or “powers that be”) influence critical policy arenas while the state’s civilian political institutions, including the parliament, have more limited prerogatives.

Le pouvoir sits atop Algeria’s patronage system; a clientelistic hierarchy through which the country’s vast oil rents are distributed to elites and the public.Footnote21 Yet Algeria has relatively robust freedom of speech. Citizens are free to criticize civilian institutions (e.g., President, Parliament), but discussion of specific members of le pouvoir or their business are red lines.

Like other authoritarian regimes in the Arab world, Algeria’s government is centralized with a strong executive branch that maintains dominance over legislative assemblies, including the parliament, APWs, and APCs. This system is held in place through electoral structuring – including proportional representation electoral laws that transfer extra votes to the dominant party, the National Liberation Front (FLN)Footnote22 – and an informal system of patronage that serves to co-opt opposition from society. Since 1997, two pro-government parties – the FLN and the National Rally for Democracy (RND) – have won a majority of seats in the legislative assemblies, ensuring executive dominance. The hegemony of unelected elites over the civilian institutions (which include the legislative branch) – and of the executive (i.e., presidency) over the legislative branch – extends to the regional and local levels through appointed governors (wali).

Political parties

Between its independence in 1962 and 1989, Algeria was a socialist, one-party state which held competitive elections, but only one party competed; the FLN, the single party that was indistinguishable from the state. By the 1980s, economic problems and civil unrest prompted officials to amend the constitution to allow multi-party elections, which took place in 1989–1991.Footnote23 The Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) did well in local and regional elections and was poised to win a majority of seats in the parliament in 1990. This led to the banning of the FIS, halting the elections, and throwing the country into a decade of civil war referred to as “the Black Decade” pitting the state against armed Islamist groups.Footnote24

Multi-party elections resumed in 1997, but not without careful electoral structuring by regime incumbents. Islamist and non-Islamist parties compete, but incumbents structure elections to ensure that the dominant parties, the FLN and the RND, win a majority of seats at the local, provincial, and national levels.

Several parties held seats at the national parliament and regional and local councils when the survey was conducted in 2007.Footnote25 These included pro-regime parties, the FLN, and the RND, which won 199 and 47 seats respectively. Two Islamist parties, Islah and the Movement of Society for Peace (MSP), received 43 and 38 seats respectively. The socialist Workers’ Party (PT) won 21 seats, and independents and minor parties received 41 seats. Two Amazigh parties, the Rally for Culture and Democracy (RCD) and Democratic and Social Movement (MDS), boycotted legislative elections ().

Table 1. Algerian political parties.

The electoral fortunes of opposition parties in Algeria, including Islamist parties, depend on their cooperativeness with the regime and the regime’s perception of the threat posed to its power by the opposition parties in question. Parties that play by the rules and enhance the veneer of democracy without posing a credible challenge to the regime, will be rewarded when the Ministry of Interior decides the broad outlines of what the electoral results will be. This system of elections is an open secret in Algeria; even newspapers discuss it. Some say that the socialist PT increased its seats in parliament after 2002, despite having limited appeal in society, because it offered a veneer of democracy without posing a real threat to the regime. In contrast, the Islah party was divided through regime manipulation in the 2000s after its leader was seen as too charismatic, capable of mounting a credible challenge in the legislature and in presidential elections.

As of 2007 when the survey was conducted, the Islamist MSP was in coalition with the FLN and RND parties in the parliament and was part of President Bouteflika’s cabinet – while a second Islamist party, Islah, did not join the coalition and was subject to interference by the regime. This forced the party to split and to occupy two separate offices on different floors of the parliament. One of its members claimed that Islah (and other parties) were watched by other members of parliament, who served as informants to the incumbent regime.Footnote26 Finally, the Worker’s Party was in opposition to the regime at this time and there were several small pro-regime parties (the FNA and the MEN) and independents.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Opposition parties, including Islamist parties, participate within a clientelistic context in which regime incumbents hold the power to shape the rules of the game. Islamist parties must develop electoral strategies that adhere to their ideology and values, while recognizing the role that clientelism plays in attracting support.

In an effort to explain Islamist parties’ electoral success, some scholars argue the clientelistic context – not religious appeals alone – to be key to Islamist party strategies and electoral success.Footnote27 I argue that religion provides a core set of values that encourage party members to reject corruption and serve citizens, regardless of their background. This prompts them to institutionalize constituency service in an effort to reach out broadly beyond their existing networks. This includes citizens from groups that are traditionally marginalized from clientelistic networks with political elites, including women.Footnote28 To a greater degree than those of other parties, members of Islamist parties work together for the benefit of the party over their personal ambitions.Footnote29 What sets Islamists apart from other parties is not simply their focus on religious piety, but also their party institutionalization and cohesiveness that emerges as a result of this electoral strategy.

According to extant literature, Islamist parties institutionalize service provision through party structures and offices, and interact directly with citizens in local communities and institutions.Footnote30 Cammett and Jones LuongFootnote31 argue that Islamist parties govern with relative effectiveness and mobilize voters through their organizational capacity, social service provision, commitment to serve all citizens regardless of socioeconomic background, and reputation as responsive, clean politicians. Islamist parties, more than others, institutionalize service provision by establishing direct contact with citizens through a network of party and local offices, mosques, social service institutions, and schools.Footnote32 Islamist parties focus on social service provision to gain support from the needy in their communities,Footnote33 working together to serve all members of society.Footnote34

Islamist parties utilize face-to-face connections with constituents, but they do so to bolster party rather than personal reputation.Footnote35 At least in theory, Islamists reject corruption and clientelism and seek to serve all constituents in a fair and transparent way. They stress fairness and social responsibility as part of their religious ideology.Footnote36 Islamists aim to maintain moral superiority over other parties, and this gives them a sense of identity that motivates their members and promotes their political success. Islamist parties work from the grassroots level and are often more effective in doing so than other parties.Footnote37

Between 2006 and 2007, I surveyed 97 members of the Algerian House of Representatives from different parties. This survey allows me to assess the extent to which Islamist and non-Islamist deputies perceive electoral incentives, with data pointing to differences in party institutionalization and cohesiveness across the parties, revealing Islamist deputies to be significantly more likely to state that their electoral success depends on working for their party, not their personal reputation.Footnote38

For instance, I asked MPs to identify their strategy for reelection, whether to promote their party or personal reputation. A measure of the incentive to cultivate the personal vote,Footnote39 the question asked: “In your opinion, what is the best strategy for seeking reelection to the National Popular Assembly? 1 = Build a strong party image, 2 = Build a strong party and personal image, but focus on the party image, 3 = Build a strong party and personal image equally, 4 = Build a strong party and personal image, but focus on the personal image, 5 = Build a strong personal image.” As shown in , members of the three Islamist parties and factions had an average response of between 1.6 and 2.8, the most party-centric among the parliamentary groups surveyed. Members of the dominant parties, the FLN and RND, answered 2.8 and 3.1 on average, respectively. The most focused on the personal vote, independents answered 5.0 on average, followed by 5 for MEN, which had one seat in parliament at that time, and 4.5 for FNA, a pro-regime party that had eight seats in parliament. Differences in perceived incentives to cultivate a personal vote were statistically significant (p < .001).

Table 2. MPs’ perceived incentives to promote their party’s image.

Additionally, numerous Islamist deputies stated in the qualitative interviews that they cannot “decide to run;” it depends on whether the party selects them for the party or not.

To a greater degree than those of other parties, members of Islamist parties work together for the benefit of the party over their personal ambitions.Footnote40 I argue that what sets Islamists apart from other parties, however, is the party institutionalization and cohesiveness that emerges as a result of this electoral strategy. This includes community members that they may not know and those from groups that are traditionally marginalized from clientelistic networks with political elites – including women.Footnote41

Accordingly, I hypothesize that, all else being equal, Algerian citizens who contact a representative with whom they have no relationship are more likely to contact an Islamist member than a non-Islamist member (H1). Further, female citizens are more likely to contact Islamist members than non-Islamist officials (H2).

H1:

Algerian citizens who contact a representative with whom they have no relationship are more likely to contact an Islamist member than a non-Islamist member.

H2:

Female citizens are more likely to contact Islamist members than non-Islamist officials.

Data and methods

To examine constituent service activities, I draw on an original, nationally-representative household survey of 782 Algerian citizens, conducted face-to-face by a local team of researchers in 2006. The response rate was 73 percent.Footnote42 The survey was conducted by Dr. Abdallah Bedaida, who led a team of trained Algerian interviewers in the field. The team also conducted the Arab Barometer using the same team of interviewers shortly before this survey was fielded, although the two surveys were administered separately.

To draw a sample, researchers used a multi-stage probabilistic sampling design, selecting eight wilayat (districts) and thirty-six communes. The eight provincial seats were self-representing. Quotas were used to select one member of each selected household, with respondent gender, age, and education as the strata.

Measurement

To measure constituent service contacts between members and citizens, the survey asked citizens whether they had contacted a member of parliament during the current mandate (2002–2007) to ask for help with a community or personal problem or to express an opinion. If the respondent had asked a parliamentarian for help, they were asked a series of questions about the most recent request: (1) whether the request was successful, (2) what party the member represented, and (3) why he or she contacted the particular member.

To measure the absence of a prior relationship between the respondent and the legislator, requests were coded as: (1) no personal connection (i.e., “just because the member was elected”) or (2) a personal connection (including “member of your tribe,” “friend,” “another connection such as business,” and “a member of the party you belong to.”).Footnote43 The survey then asked the same battery of questions for contacts with members of the respondent’s APW and APC. (See Appendix for questions wording).

When the survey was conducted, members of the APN, APWs, and APCs had been in office for four years since the 2002 legislative elections and were expecting new elections to be held in 2007.Footnote44

Constituency service contacts

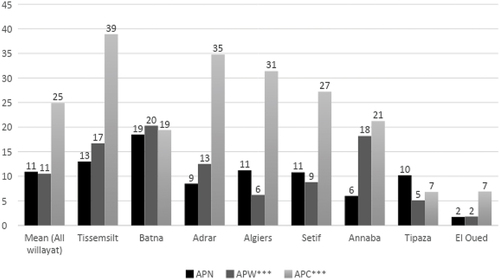

Because only 782 citizens took part in the survey and contacting an MP is a relatively uncommon occurrence, I also include data on contacts between citizens and members of the regional and local councils. In the country as a whole, 11 percent of citizens reported that they had contacted an MP in the five years preceding the survey, 11 percent had contacted a member of a regional council (i.e., an APW), and 25 percent had contacted a member of a local council (i.e., and APC) ().

Analysis and discussion

I use two-tailed Chi-squared tests of independence to test whether Islamist parties reach a wider cross-section of citizens than other parties.Footnote45 First, I assess whether Islamist parties, more than other parties, reach out to citizens with whom their members have no previous relationship more than do members of non-Islamist parties. Second, I examine whether members of Islamist parties reach out to women – a group that is marginalized from clientelistic networks in the political sphere – more than members of other parties.

Do Islamists form more new networks?

The data suggest that Islamist parties, more than non-Islamist parties, serve more citizens with whom they have no connection, in support of H1 (). No respondents reported contacting an Islamist MP. Yet all of the citizens who reported contacting an Islamist member of an APW and 80 percent for Islamist members of an APC said they did not know the person before they contacted the MP.

Figure 3. Proportion of Algerian citizens (among those who contacted an elected official) who did not have a personal relationship with the official.

In contrast, only 14 percent of citizen who contact an FLN MP did not know the MP beforehand, compared with 39 percent for APWs and 54 percent for APCs. All of those who contacted an MP from the RND knew the individual beforehand. Relatively few (17 percent regionally and 28 percent locally) did not know the RND member that they contacted. This suggests that non-Islamist parties, more than Islamist parties, interact with constituents who are already in their personal, party, business, or other networks. Conversely, Islamist parties, more than other parties, receive constituency service contacts from citizens whom they do not know already. This, I argue, is due to Islamist parties’ efforts to institutionalize constituency relations and reach out to people in their communities, regardless of whether they are in their networks or not.

The data also show some differences in networks across MSP and Islah, Algeria’s two Islamists parties. Citizens reported more contacts with the MSP than Islah. One possible reason for this difference is that the MSP, due to its coalition with the government, enjoyed more cooperative relationships with regime incumbents and greater access to state resources which allowed it to be effective at serving citizens. Islah in contrast may have lacked cooperative relationships within the state and thus fewer resources to reach citizens. This is consistent with field interviews and observations. At the time of the survey, the Islah party was considered a threat to the regime because its leader was charismatic and a potential presidential contender, and the party had not accepted to join the government coalition. As a result, its members reported that they had few relationships in the government that would allow them to solve their constituents’ problems.Footnote46

Do Islamist parties serve more women?

The data also show that women are more likely to contact members of Islamist parties – both MSP as well as Islah – than members of non-Islamist parties (), in support of H2. Differences are not statistically significant, due to the small number of respondents, but they are substantively large. Nationally, 67 percent of citizens who contacted Islah parliamentarians were women, compared to 25 percent who contacted the FLN’s MPs and 33 percent for the RND’s deputies.

Figure 4. Proportion of Algerian citizens (among those who contacted an elected official) who were women.

When considering APWs and APCs, the data are more mixed. Women were more likely to contact Islamist members than non-Islamist members for the APWs but not the APCs, in partial support for H2. All of the citizens who reported contacting MSP members at the APW were women, compared to 45 percent for the FLN and 43 percent for the RND. At the local level, about half of those who contacted the FLN, RND, or the Islamist MSP were female citizens. Locally, half of those who contacted the non-Islamist RND and the Islamist MSP were women, compared to 27 percent for the FLN.

Conclusions and implications

The survey supports the expectations that Islamist parties, more than other parties, reach out broadly, connecting with citizens from groups that are marginalized from existing clientelistic networks, including women. That Islamist parties serve more women than other parties – those often referred to as “secular” parties – may seem counter-intuitive. Yet it supports the conclusion that what inhibits equal access to government officials is not Islam but the clientelistic context.Footnote47 It also suggests a paradox. Islamist parties support conservative gender relations. Yet their greater party institutionalization allows them to reach a broader cross-section of the population. In contrast, members of non-Islamist parties connect more often with those whom they already know, and who are often men.

The findings thus extend studies on Islam, gender, and governance by offering evidence from a new case – Algeria – suggesting that Islamist parties bypass existing patronage networks that exclude women.Footnote48 While this study does not measure actual receipt of services, evidence that women are more able to contact members of Islamist parties goes against the conventional wisdom that Islam and women’s rights are incompatible.Footnote49 This also suggests that clientelism,Footnote50 not religion, most hinders women’s representation, at least in so far as clientelistic responsiveness of elected officials is concerned.Footnote51

It is also worth noting that Islamists’ greater tendency to reach new networks and female constituents is especially pronounced at the local level relative to the national level. Farole argues in South Africa that support for opposition parties grows in dominant party systems in which opposition parties provide effective service delivery through local government.Footnote52 The evidence from Algeria suggests that Islamists, as opposition party members, are more effective in establishing new networks at the local than the national level.

It is important to consider that every context is unique. Existing work suggests that Islamists in MoroccoFootnote53 and TunisiaFootnote54 are more likely than other parties to connect with female citizens. More research is needed to build a comparative framework in order to understand how party institutionalization and contextual factors shape who benefits from access to elected officials. New surveys should increase the number of respondents, given that contacting an MP is a relatively rare event. Through these extensions, scholars will develop a better understanding of why Islamist movements succeed and fail in authoritarian and clientelistic contexts.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the Association for the Study of Middle East and North Africa (ASMEA) for supporting the presentation of this paper at the annual meeting, November 18–20, 2020, Washington, DC. Special thanks to Marc Lynch and Ellen Lust for funding the presentation of an earlier version of this paper at the “Workshop on Islamists and Local Politics,” June 13–15, 2017, Brastad, Sweden, and to Lauren Baker, Stephanie Dahl, Kristen Kao, and other participants for their helpful feedback. Thanks to Mark Tessler, Susan Waltz, Daoud Abismail, Foudil Boumala, Lazhar Chine, Malika Harrar, and Djamel Moktefi for fieldwork support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lindsay J. Benstead

Lindsay J. Benstead is Professor of Politics and Global Affairs and Director of the Middle East Studies Center (MESC) at Portland State University. She holds a Ph.D. in Public Policy and Political Science from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Notes

1 See for example, Michael D. Robbins, “What Accounts for the Success of Islamist Parties in the Arab World?’ Dubai School of Government Working Paper no. 10–01 (Jan. 2010), http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.472.198&rep=rep1&type=pdf; Daniel Brumberg, “Islamists and the Politics of Consensus,” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 3 (2002): 109–15; Mark Tessler, “The Origins of Popular Support for Islamist Movements,” in Islam, Democracy, and the State in North Africa, ed. John Entelis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997), 93–126; Carlos Garcia-Rivero and Hennie Kotze, “Electoral Support for Islamic Parties in the Middle East and North Africa,” Party Politics 13, no. 5 (2007): 611–36; Eva Wegner, “The Islamist Voter Base During the Arab Spring: More Ideology than Protest?” POMEPS Studies 26 (Jan. 2017) https://pomeps.org/the-islamist-voter-base-during-the-arab-spring-more-ideology-than-protest; Elizabeth Gidengil and Ekren Karakoç, “Which Matters More in the Electoral Success of Islamist (Successor) Parties – Religion or Performance? The Turkish Case,” Party Politics 22, no. 3 (2016): 325–38; Janine A. Clark, “Social Movement Theory and Patron-Clientelism: Islamic Social Institution and the Middle Class in Egypt, Jordan and Yemen,” Comparative Political Studies 37, no. 8 (2004): 941–68; Janine A. Clark, Islam, Charity, and Activism: Middle-Class Networks and Social Welfare in Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004); Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, Mobilizing Islam: Religion, Activism, and Political Change in Egypt (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002); and Maleke Fourati, Gabriele Gratton, and Pauline Grosjean, “Voting Islamist: It’s the Economy, Stupid,” Vox, July 14, 2016, http://voxeu.org/article/voting-islamist-it-s-economy-stupid.

2 Tarek Masoud, Counting Islam: Religion, Class, and Election is in Egypt (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

3 Steven Brooke, Winning Hearts and Votes: Social Services and the Islamist Political Advantage (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019).

4 Lindsay J. Benstead, “What Explains Voter Preferences in Transitional Tunisia? The Role of Particularistic Benefits,” Journal of Middle East and Africa, Forthcoming.

5 Hugh Roberts, The Battlefield: Algeria, 1988–2002: Studies in a Broken Polity (London: Verso, 2003).

6 Hung-En Sung, “Fairer Sex or Fairer System? Gender and Corruption Revisited,” Social Forces 82, no. 2 (2003): 703–23.

7 Mounah Abdel-Samad and Lindsay J. Benstead, “Do Islamist Parties Help or Hinder Women? Party Institutionalization, Piety and Responsiveness to Female Citizens,” Digest of Middle East Studies 31, no. 4 (2022): 293–318.

8 Jennifer Gandhi and Adam Przeworski, “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats,” Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 1 (2007): 1279–307.

9 Lisa Blaydes, Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010); Daniel Corstange, The Price of a Vote in the Middle East: Clientelism and Communal Politics in Lebanon and Yemen (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016); and Ellen Lust-Okar, “Competitive Clientelism in the Middle East,” Journal of Democracy 20, no. 3 (2009): 122–35.

10 Luigi Manzetti and Carole J. Wilson, “Why Do Corrupt Governments Maintain Public Support?” Comparative Political Studies 40 (Aug. 2007), 953.

11 Basem Sakijha and Sa’eda Kilani, Wasta: The Declared Secret (Amman, Jordan: Arab Archives Institute, 2002).

12 Heinz Eulau and Paul D. Karps, “The Puzzle of Representation: Specifying Components of Responsiveness,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 2, no. 3 (1977): 233–54.

13 See Lindsay J. Benstead, “Why Quotas Are Needed to Improve Women’s Access to Services in Clientelistic Regime.” Governance 29, no. 2: 185–205.

14 Lisa Blaydes and Safinaz El Tarouty, “Women’s Electoral Participation in Egypt: The Implications of Gender for Voter Recruitment and Mobilization,” The Middle East Journal 63, no. 3 (2009): 364–80.

15 Interview 1, Male parliamentarian, Al-Haouz, Morocco, 2007.

16 Benstead, “Why Quotas Are Needed to Improve Women’s Access to Services.”

17 Susan C. Stokes, Is Vote Buying Undemocratic? Elections for Sale: The Causes and Consequences of Vote Buying (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007).

18 Interview 2, Male parliamentarian, Rabat, Morocco, 2007.

19 JR Johannes, “The Distribution of Casework in the U.S. Congress: An Uneven Burden,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 4, no. 1 (1980): 517–44; and Bruce Cain, John Ferejohn, and Morris Fiorina, The Personal Vote: Constituency Service and Electoral Independence (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013).

20 John P. Entelis, “Algeria, Revolutionary In Name Only,” Foreign Policy, Sept. 7, 2011, http://foreignpolicy.com/2011/09/07/algeria-revolutionary-in-name-only/; and Roberts, The Battlefield: Algeria.

21 Frédéric Volpi, “Algeria Versus the Arab Spring,” Journal of Democracy 24, no. 3 (2013): 104–15.

22 Amaney A. Jamal and Ellen Lust-Okar, “Reassessing the Influence of Regime Type on Electoral Law Formation,” Comparative Political Studies 35, no. 3 (2002): 337–66.

23 Elections were suspended between 1991 and 1997 during the country’s civil war.

24 Roberts, The Battlefield Algeria. The FIS was formed in 1989 when the single-party, socialist state for the first time separated the party from the state and called for multiparty elections. A branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, the FIS did well in local elections, capturing several mayoral races. When the FIS was posed after the first round of parliamentary elections in 1990 to win a majority in the parliament, the military canceled the elections, plunging the country into a decade of civil war. In the early 2000s, an amnesty agreement allowed many FIS members to be released from jail in exchange for no longer engaging in politics. Yet other Islamist parties have experienced manipulation by the regime as well. The Ministry of Interior interfered with the Islamist party, Islah, by reordering of its electoral lists in 2002, eliminating candidates from its party lists that the regime found threatening. In the past, Islamist candidates have been vetted and sometimes removed from otherwise lawful electoral lists by the Ministry of the Interior. Interview, Islah parliamentarian, Algiers, 2008 (Benstead).

25 The parliamentary election was held on May 30, 2002.

26 Lindsay J. Benstead, “Does Casework Build Support for a Strong Parliament? Legislative Representation and Public Opinion in Morocco and Algeria” (PhD Thesis, University of Michigan, 2008).

27 Masoud, Counting Islam; Wegner, “The Islamist Voter Base During the Arab Spring”; and Benstead, “What Explains Voter Preferences in Transitional Tunisia?”

28 Benstead, “Why Quotas Are Needed to Improve Women’s Access to Services.”

29 Lindsay J. Benstead, “Islamist Parties and Women’s Representation in Morocco: Taking One for the Team,” in The Oxford Handbook of Politics in Muslim Societies, ed. Melani Cammett and Pauline Jones (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190931056.013.39.

30 Cammett and Luong, “Is There an Islamist Political Advantage?”; and Abdel-Samad and Benstead, “Why Does Electing Women and Islamist Parties.”

31 Cammett and Luong, “Is There an Islamist Political Advantage?”

32 Dalibor Rohåc, “Religion as a Commitment Device: The Economics of Political Islam,” Kyklos 66, no. 2 (2013): 256; Philip Keefer and Razvan Vlaicu, “Democracy, Credibility and Clientelism,” Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 24, no. 2 (2008): 371–406; and Abdel-Samad and Benstead, “Why Does Electing Women and Islamist Parties.”

33 Myriam Catusse and Lamia Zaki, “Gestion Communale et Clientelisme Moral au Maroc: Les Politiques du Parti de la Justice et du Développement,” Critique International 42(2009): 73–91; John Walsh, “Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood,” Harvard International Review 24, no. 4 (2006): 32–6; and Qunitan Wiktorowicz, “Islamist Activism in Jordan,” in In Everyday Life in the Muslim Middle East, ed. Donna Lee Bowen and Evelyn A. Early Second ed.(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), 227–45.

34 Yeşim Arat, Rethinking Islam and Liberal Democracy: Islamist Women in TurkishPolitics (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2005); Jaline A. Clark and Jillian Schwedler, “Who Opened the Window? Women’s Activism in Islamist Parties,” Comparative Politics 35, no. 3 (2003): 293–312; Sencer Ayata, “Patronage, Party, and State: The Politicization of Islam in Turkey,” Middle East Journal 50, no. 1 (Winter 1996): 40–56; and Blaydes and El Tarouty, “Women’s Electoral Participation in Egypt.”

35 Wickham, Mobilizing Islam; Clark, Islam, Charity, and Activism; Stacey Philbrick Yadav, “Segmented Publics and Islamist Women in Yemen: Rethinking Space and Activism,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 6, no. 2 (2010): 1–30; and Arat, Rethinking Islam and Liberal Democracy.

36 Cammett and Luong, “Is There an Islamist Political Advantage?”; and Wickham, Mobilizing Islam.

37 Jenny B. White, Islamist Mobilization in Turkey A Study in Vernacular Politics (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

38 Benstead, “Does Casework Build Support for a Strong Parliament?”

39 Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina, The Personal Vote: Constituency Service and Electoral Independence (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987).

40 Benstead, “Islamist Parties and Women’s Representation in Morocco.”

41 Elin Bjarnegård, Gender, Informal Institutions and Political Recruitment: Explaining Male Dominance in Parliamentary Representation (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

42 This research was conducted with Institutional Review Board approval and followed all applicable conventions for human subjects’ protections.

43 Respondents could answer more than one type.

44 Algeria is a single party-dominant regime which held legislative elections for the national/regional/local elections in 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017, and 2021.

45 Multivariate models are not possible due to the small number of respondents who contacted a Member of Parliament from each political party.

46 Benstead, “Does Casework Build Support for a Strong Parliament?”

47 Sung, “Fairer Sex or Fairer System?”

48 Tripp, “The New Political Activism,” 141–55; and Bjarnegård, Gender, Informal Institutions.

49 M. Steven Fish, “Islam and Authoritarianism,” World Politics 55, no. 1 (2002): 4–37; and Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris, “The True Clash of Civilizations,” Foreign Policy 135, no. 1 (2003): 62–70.

50 Sung, “Fairer Sex or Fairer System?”

51 Abdel-Samad and Benstead, “Why Does Electing Women and Islamist Parties.”

52 Safia Abukar Farole, “Eroding Support from below: Performance in Local Government and Opposition Party Growth in South Africa,” Government and Opposition 56, no. 3 (2021): 525–44.

53 Benstead, “Islamist Parties and Women’s Representation in Morocco.”

54 Benstead, “What Explains Voter Preferences in Transitional Tunisia?”

Appendix A

Table A1. Constituent survey question wording.