Abstract

This ethnographic study examines how gender roles associated with male and female Qatari students in intercultural communication courses in a university in Qatar are negotiated between them and their two female instructors from the US and Greece. Our aim is to contribute towards the development of good practice related to the teaching of information exchange among group members who are not culturally alike,1 by arguing that an efficient way of overcoming misunderstandings between instructors and students is to engage in a pedagogical approach, which we call “dialogical infotainment”. This serves the ultimate goal of sharing various types of power in order to sharpen our cultural sensitivity and subsequent tolerance and respect for each other’s gender role-related peculiarities.

1 Introduction

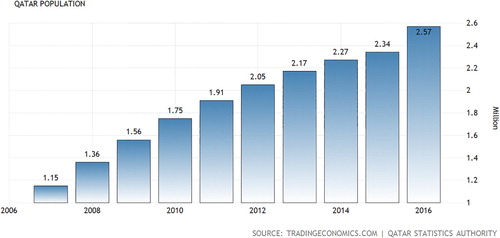

Qatar is a small state bordering Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates that came under the global spotlight following its successful bid to host the World Cup in 2022.Footnote2 After the discovery of oil in the 1970s, and more recently the development of vast reserves of natural gas, the country has by some counts become the richest, per capita, in the world. This has been accompanied by rapid modernization and the diversification of its population, which continues to expand. Among the approximately 2.6 million people that constitute the contemporary population of Qatar (see ), Qatari citizens number around 340,000.Footnote3 This segment, which is the focus of our paper, is characterized by intense gender segregation which is found in governmental institutions such as ministries and state educational institutions.

Figure 1: Population of Qatar, 2008–16. Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/qatar/population

Against this backdrop, and as Western female instructors in tertiary education interacting with students from both genders both inside and outside the classroom, we feel more often than not that there are misunderstandings between our male and female students with regard to how they perceive each other. Therefore we have become increasingly interested in fleshing out what “gender roles” mean to us and to our students, as well as how these are, or can be, negotiated in the university classroom.

To this end, we focus in this paper on intercultural communication, meant here as the communicative practices of cultural differences between distinct cultural groups interacting with each other.Footnote4 More specifically, because we are dealing with intercultural communicative practices in the context of a university, the structure of which is inevitably characterized by power relations, we tend to take a more critical intercultural communicative stance vis-à-vis our data. This means that we take into consideration issues of power, context, socio-economic relations and historical/structural forces, as constituting and shaping culture and intercultural communication encounters, relationships and contexts.Footnote5 These power relationships are correlated with how each group perceives the other, their respective sociocultural experiences, and their flexibility and adaptability to each other’s cultural norms and expectations. In this way, we are interested in delving into how gender roles are negotiated in the context of intercultural communication courses, through focusing on the nexus of culture, actors and the context of communication.Footnote6

More specifically, we discuss the content of the label “gender roles” from the perspective of our Qatari students –– both male and female –– and compare it to our own American and Greek female ones respectively. Subsequently, we discuss a successful practice that we have developed over the years in our respective Intercultural Communication classes, which we call “educational infotainment”; this, we suggest, is an efficient pedagogical approach to bridging the gap between opposing views on gender roles and to contributing towards a better understanding of the different cultures forming the “gender roles” in question. We argue that sociocultural and structural power relations in and behind gendered discourses,Footnote7 both inside and outside the classroom, need to be taken into consideration and to be made explicit in the context of educational infotainment, in order for both our students and ourselves to be sensitized towards the reasons why we perceive gender roles the way we do, and in this way, to understand each other’s different views on them and on intercultural communication in general. By doing this, we can understand not only how the actors involved in the negotiation of gender roles draw on their respective cultures but also the reasons why they do so. However, before these two discussions, we review the existing literature on intercultural communication between non-Arabs and Arabs and show where our research fits in the existing body of research.

2 Gender, sociocultural linguistics and intercultural communication between non-Arabs and Arabs

The literature on intercultural communication non-Arabs and Arabs focuses primarily on the parts of traditional Arab culture that render communication with Arabs less than straightforward in a number of domains and contexts, including family, educational settings and professional workplaces.Footnote8 However, literature on the differing views on gender roles and the ways these are constructed and negotiated in the Arab world remains scarce.Footnote9 We understand “gender” as the cultural traits and behaviors deemed appropriate for men or women by a particular society.Footnote10 These are the outcome of a stylized repetition of acts which are internally discontinuous so that the appearance of substance is precisely that, a constructed identity, a performative accomplishment that the ordinary social audience, including the actors themselves, come to believe, and to perform in the mode of belief.Footnote11 But for us, and in alignment with Deborah Tannen’s work on Greeks and Americans,Footnote12 male and female genders, along with their respective performed masculinities and femininities, can be seen as a continuum that has been created through the different ways in which boys and girls are socialized from the beginning of their lives,Footnote13 a fact that leads to the emergence of different cultures and different gender roles associated with these cultures. By “culture” we mean a larger social formation constituted through communicative meaning-making practices (or dialectical exchanges among meanings, practices, and structures).Footnote14 The communicative meaning-making process of interest here is the negotiation of gender roles that takes place between our students and us as their instructors in the classroom.

With regard to Arab culture, the masculine culture values of the Arab world distinguish between gender roles. On the one hand, females in Arab societies are encouraged to be communal, to prioritize their domestic responsibilities and to fulfil their socially-ascribed role as wives and mothers,Footnote15 while males are socialized to pursue their careers and to be financially independent.Footnote16 These patterns are particularly evident in intercultural communication studies focused on gender that have been conducted in the Arab world; it has been found, for instance, that a number of Lebanese families “resist education for their daughters on the grounds of the cultural values that promote masculinity”.Footnote17 In cases where female members of the family are allowed to study, they are usually steered towards traditionally female subject areas, including education, medicine, and businessFootnote18 and economics, but definitely not engineering or any type of major that will result in their landing in a workplace where they will be required to work in a mixed-gender environment. In addition, women in general, even when they are allowed, or decide to have a career, will inevitably have to adjust their aspirations to meet family expectations,Footnote19 since marriage and motherhood are well-known cultural values in the Arab world.Footnote20

On the other hand, men are usually left to decide for themselves what to study, and are also encouraged to exhibit competitiveness and to strive for excellence in their professional lives; the discourses pertaining to the latter are not enmeshed with the discourse of family.Footnote21 In other words, it is assumed that men can advance in their professional lives without having to worry about their family lives. In the case of masculine discourses in the Arab world, the clear distinction between professional and family-related discourses is due to the patriarchal values that are also to be found in Qatar.

The social structure of Qatari society is one of patriarchy, namely a hierarchy of authority that is controlled and dominated by males,Footnote22 originating in the family. This has repercussions in terms of how power is distributed among the members of larger (e.g. tribe) or smaller (e.g. family) social groups, which together form the social fabric.Footnote23 Even though men would be expected to be the most powerful group because they form the basis of such a structure, in certain domains, such as in decisions having to do with running the household or in terms of who gets to decide, who will be married to whom, for both male and female children, it is the women who have the upper hand.

This imbalance in terms of power distribution, accordingly, has an influence on how groups perceive the cultural other and how they treat them. This imbalance is also maintained by the fact that almost 70 percent of the student population in Qatari universities consists of women.

Against this backdrop, the research questions that we address here include the following: (1) how do Qatari students understand “masculinities” and “femininities”? and (2) how do we as instructors and our students negotiate gender roles in the classroom?

The combination of these two questions indexes our analytical framework, which is an ontologically constructivist and epistemologically interpretivist oneFootnote24 with a focus on gendered discourses, namely the set of beliefs, norms and practices associated with gender in Qatar. The constructivist ontological dimension translates into our acknowledgement of the multiple subjective realities that our participants face, while the interpretivist epistemological one is identified with our attempt, as analysts, to understand the perspective of our participants and to give it voice in academic discourse. In this sense, issues of power figure prominently in our analytical discussion below.

However, before we consider the content of masculinities and femininities and the ways these are negotiated in intercultural communication, a brief discussion of our methodology and data is in order.

3 Gender-oriented ethnography

Given the emphasis we place on the context and the deep knowledge of the sociocultural structure of Qatar, the methodology we used to collect our data was primarily linguistic ethnography,Footnote25 both inside and outside the classroom, with a special focus on discoursesFootnote26 pertaining to gender roles. Having now lived and worked in the country for over seven years, both of us have engaged in extensive participant observation and field note taking with respect to our students –– in the classroom, in the hallway, and in the Men’s and Women’s Activities Buildings on Qatar University’s gender-segregated campus, where our students usually spend their break time. Our ethnographic observations started in September 2010 and lasted till June 2016. We closely observed twelve Qatari females and seven Qatari male students between eighteen and twenty years of age, who had agreed to be observed and interviewed. Similarly, both of us attended weddings or participated in desert camps or by invitation visited our former female students’ houses, thereby receiving a privileged glimpse into their academic as well as their more personal lives. As female instructors, and given the gender segregation found in Qatar University, our experience outside the classroom stems primarily from our female students, while our experience with our male students comes largely from inside the classroom and from interactions with them in our university offices. This background knowledge is vital for our understanding of their gender-related behavior, given that it stems from a gender-segregated environment with which neither of us was familiar before we arrived in Qatar.

Our understanding of gender-related roles has been significantly informed by conducting ethnographic interviewsFootnote27 with both our male and female students, especially those who helpfully agreed to be interviewed. In these semi-structured interviews, we asked what they considered typical features and personality traits of “a good man” and “a good woman” in Qatar, as well as how they saw themselves in terms of their gender. In addition, we kept a record of interesting stories from around ninety students (sixty females and thirty males), in which the gender-related expected roles had been blurred, twisted or undermined. Both students and ourselves shared these accounts. Finally, to complement our mainly oral data with written information, we also relied on classroom material (from both male and female students) that we collected from the Intercultural Communication class that Iglal Ahmed offered in Fall semesters 2013, 2014 and 2015 as well as from the Language and Gender class that Irene Theodoropoulou offered during Spring semesters 2013, 2014 and 2015. This classroom material consisted of midterm exam papers, quizzes, home assignments and notes that dealt with gender-related topics addressed in the classroom.

All of these resources were used collectively to answer the research questions referred to above. We began our discussion with how our students perceived masculinities and femininities, before giving our own understanding of these, and concluded our analysis by demonstrating what had turned out to be good practices when negotiating gender role diversity in the university classroom.

4 Qatari perspectives on masculinities and femininities

Gender roles involve outward expressions of what society considers masculine or feminine. What gender means, and how we express it, is structurally imposed on the members of a given society, since it depends on a society’s values, beliefs, and preferred ways of organizing collective life.Footnote28 We demonstrate gender roles by how we speak, dress, or style our hair, to mention just a handful of typical gender-related behaviors.Footnote29 Precisely because we can talk about typical (and atypical, i.e. aberrant from the norms) behaviors, what is implied in the learning and handling of gender-related patterns is power –– sociopolitical and cultural –– which needs to be taken into consideration whenever we try to understand and interpret the meanings of gender.

Gender roles are ascribed to us early in life and are constructed through social norms, values, and beliefs that are culture-specific.Footnote30 As we move through our lifespans these norms and values can, of course, be modified depending on how the society deals with the forces of globalization. However, over the years and in most societies that have been investigated in terms of their gender traits, it has been observed that to be feminine is to present physical attractiveness, to act deferentially, to be emotionally expressive and nurturing, and to construct an image of seeming concerned with people and relationships,Footnote31 while to be masculine means to project a strong, ambitious, successful, rational, and emotionally controlled persona. Although these requirements are perhaps less rigid than in earlier eras, they remain largely intact. Those who are regarded as “real men” still do not cry in public, and “real men” construct a successful and powerful image for themselves in their professional and public lives.Footnote32 Within the Qatari society, femininity and masculinity are constructed primarily on the basis of their Islamic beliefs, traditions, and cultural norms. In other words, religion and culture are the two main axes around which the concept of gender is constructed and, hence, understood by the members of Qatari society. Discussing them is useful, therefore, as it serves as the context in which the meaning of gender roles needs to be interpreted.

In terms of gendered communication, there were various distinctions in communication style between female and male students. Women’s communication style is often described as supportive, egalitarian, personal, and disclosive, whereas men’s is characterized as competitive and assertive.Footnote33 However, our Qatari women were found to be resistant to these stereotypes, in the sense that they claimed to be more competitive than their male counterparts. They seemed also to be competitive with each other, in terms both of physical appearance as well as personality attributes and in order to demonstrate and establish their femininity. In this way, given that for some of them going to the university was the only way to socialize, they ended up being far from egalitarian regarding each other. However, many of them tended to be equally open with their Western female instructors and sometimes shared their personal stories, especially outside the classroom, which was their way of creating rapport. On the other hand, our male students tended to be personal and autonomous, nor did they show any interest in establishing intimacy and rapport with us. In this way, our findings partly echo Tannen’s findings that females engage in “rapport-talk” –– a communication style meant to promote social affiliation and emotional connection; while men engage in “report-talk” –– a style focused on exchanging information with little emotional import.Footnote34

With regard to femininity, the feminine norm for a woman in Qatar is to become a good wife and a role model for their children, even though we found such tendencies were resisted by some of our students who, having engaged with Western popular culture (such as Sex and the City), aspired to become more liberated and emancipated like their role models.Footnote35 In the case of people of Bedouin origin, femininity is attributed to personality traits such as reliability and interdependence, while hadhari (urban) men perceive physical appearance as more pronounced in relation to femininity than personality traits. Since public segregation of gender is a common practice within Qatari culture, and also part of the relatively rigid structure of Qatari society, Qatari men would have to defer to their female relatives to ascertain from them whether their prospective bride was fashionable. Qatari men rely heavily on the opinions of their female relatives regarding the femininity of their prospective wives. Usually when female relatives visit the home of a prospective wife, they will report back to the groom about her fashion style and whether she is dressed in designer clothes and jewelry.

Qatari female students tend to be respectful and obedient within the classroom setting; we found very few exceptions to this pattern. This is due to cultural restraints. Typically women are expected to comport themselves in order for their behavior not to reflect negatively on their family or society. This is an aspect of Arab cultural norms, and more specifically that of honor,Footnote36 since it is a collectivist society.Footnote37 Qatari society is internally stratified according to factors such as tribal affiliation, religious sect, and traditional values.Footnote38 In this sense the men are expected to behave correctly in public, in order for this to reflect positively on their family and tribe.

Femininity in Islam, Qatar’s official religion, encourages modesty. One of the characteristics of our female students is to dress modestly by dressing in hijab,Footnote39 which in Qatar translates into wearing the abaya (loose over-garment) and shaila (head scarf), which are the country’s national and traditional clothes for women. Among those of Bedouin origin, women tend to be more traditional. A few of them cover their face by wearing a niqab (face mask), especially when they are in public or in their classroom with a male instructor. In order to avoid offending traditional, religious and culture sensibilities, Western instructors often have to learn to differentiate between female students who are wearing the niqab by recognizing distinctive features pertaining to each student, i.e., eyes, or voice.

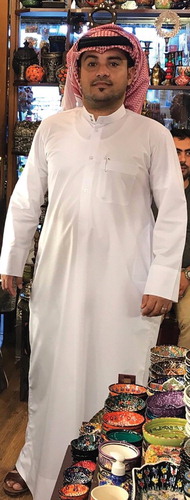

More specifically, it is impressive for us, as Western women, to see Qatari women’s knowledge of and engagement with the latest fashion trends, both Arab and international, even though in public women are expected to be covered by being dressed in their black abayas, and black shailas. Very often they also wear the niqab (in the case of Bedouin women), in order to perform modesty and not to provoke (see ). However, there is significant variation, which indicates different degrees of femininity and different degrees of managing agentive power. For example, a number of young women wear extensive makeup and strong perfumes, or wear abayas with elaborately-colored cross stitching. Along the same lines of variation, there are women who wear their shailas in such a way that they cover their hair fully, whereas others adopt the so-called “Shaikha Moza style”, which translates into wearing the shaila with some hair visible at the front of the head. This hair is usually dyed in stylish colors in order to create a contrast to the black of the shaila. One can argue that such practices indicate a tension between religious and cultural power, in the sense that they foreground the aesthetics of femininity over the religious code of modesty; they therefore meet with mixed reactions from both women and men in Qatari society, depending not only on their age, tribe and degree of religiousness but also on their education and wider sociocultural ideology.Footnote40

Femininity is also closely related to stylishness, indexed by accessories such as expensive bags and shoes by trendy high end fashion designers. In addition, body language is also applied to the use of accessories, which means that young Qatari women adopt a certain way of holding the bag and a certain feminine manner of walking, in order to highlight their femininity. Apart from their appearance, slow walking with ostentatious showing of both the bag and the prettily-decorated cellphone is also considered the way to exhibit femininity on a daily basis in public spaces, such as the university or the mall. In fact, some hadhari women go as far as to walk with their abayas opened at the front, in order to show their expensive designer clothes and shoes. Part of femininity is also having long hair (so as not to resemble men), and doing one’s hair as frequently as possible and showing it off to one’s female friends when exchanging visits at home. Consequently, young Qatari women become very competitive in terms of their looks and accessories. Interestingly, these practices were not considered very feminine by our male participants, who preferred women to wear less makeup so that their physical features would be more evident.

In line with a lack of consensus as to what constitutes femininity among female Qataris, femininity for Bedouin women is a concept that is talked about but not pursued excessively, especially in public, differently from hadhari women. Because the dominant ideal is the concept of modesty, Bedouin women usually refrain from highlighting their femininity, in order to avoid provoking other women and especially men. However, when in private settings, Bedouin women like to accentuate their femininity, primarily by dressing up and wearing expensive and elaborate heavy gold jewelry, called marria, which also signifies wealth and social status. Along the same lines, and like hadhari women, Bedouin women wear characteristic perfumes that denote femininity, with aromas that include jasmine, amber, musk and oud. In terms of Arab perfumes, they have a preference for such brands as Rakaan, Nashwa, Roohi Fedak, Attar Al-Kaaba, Haneen and Alf Laila O Laila. However, they also enjoy wearing the latest Western perfumes by brands such as DKNY, Burberry, D&G, Gucci, Tom Ford, and others. Some will also obtain customized perfumes, i.e., perfumes whose bottles are engraved with their names.

So far, our discussion has verified Butler’s viewFootnote41 of gender as a series of repeated, stylized acts that become associated with specific values attached to gendered categories, such as femininity, even though as we note, there is often a discrepancy between hadhari and Bedouin women. The discourse of Qatari femininity also includes ways of being and acting. For example, when in public, women, especially Bedouin women, are not supposed to speak loudly, the norm being that men are not supposed to hear women’s voices. More specifically, our female students reflected on this expected paralinguistic behavior by sharing with us the following saying in Arabic: “sawt al-marʾaʿawra” which translates roughly into the idea that men are not allowed to hear your (female) voice. Similarly, a soft voice is usually associated with femininity.Footnote42 Men also perceive as feminine practices such as being reserved, or not appearing in public late at night without a mahram (unmarriageable male kin/chaperone). In addition, contradictory practices, such as participating in sports and smoking, are considered less feminine even though women in Qatar have started engaging in these practices, even in public spaces. However, for us as researchers it was really surprising to hear that for some women engaging in sports was considered to be more masculine (and thus to be avoided) than smoking.

In terms of their expected careers, women’s scope is more limited than men’s, inasmuch as the former are encouraged to pursue studies in more “feminine domains” such as education, medicine, and social sciences, but not “hard core sciences” such as engineering. These norms have led to a significant number of women being employed and developing in companies and ministries in these fields, while at the same time they have resulted in a scarcity of women in scientific domains, such as computer engineering, marine engineering, and aerospace divisions. Against this backdrop, both Bedouin and hadhari female students are obsessed with their grades since these are perceived to be the stepping stone to competing with their male counterparts and to gaining positions within the limited professional arena noted above.

Finally, femininity in Qatar, according to many of our students, does not go hand in hand with professional development, in the sense that the very few women who have managed to be promoted and become managers and/or leaders are usually accused of turning into “women who behave like men”. Of course, there are exceptions to this discourse, such as H.H. Shaikha Moza who, despite being a leading figure in a number of institutions and projects both within and outside Qatar, is a woman who is very often praised for her stylistic choices as well as her femininity (see ).

On the other hand, the Qatari masculinity discourse is demonstrated in various ways, and more specifically through men’s hobbies, appearance, and the values they believe in. Regarding hobbies, males in Qatar enjoy participating in outdoor, indoor and group-based activities. Bedouins in particular tend to express their masculinity through engaging in more traditional practices associated with the heritage of Qatar, such as breeding camels and falcons, hunting, and camping. Ownership of falcons is a masculine trait which also indexes wealth and status within the Qatari culture. It is not unusual to see men walk around the souqFootnote43 with their falcons on their shoulders (see ).

Another predominant masculine hobby in Qatar is the possession of expensive brands of car, such as Lamborghini, Ferrari, Maserati, Rolls Royce, and Bentley. In fact, sports cars such as Mustangs are perceived to be more masculine than, for example, the Land Cruiser, omnipresent in the streets of Qatar. Sometimes the cars are custom-made or painted with gaudy colors, such as fuchsia, and accessorized with high-end designer interiors, such as Burberry. We find this surprising and somehow contradictory to the masculine discourse, given that in our respective cultures fuchsia is a color that usually indexes femininity and/or gayness.

The purchase of unique and elaborate licence-plate numbers is another indication of masculinity among Qatari men that becomes intermingled with a discourse of status and distinction.Footnote44 The uniqueness of numbers is marked through the presence of fewer than six digits, the purchase of which could range from thousands to hundreds of thousands of Qatari riyals. However, for desert and camping trips, men usually drive Toyota Land Cruisers. These activities are prevalent in demonstrating masculinity among both Bedouin and hadhari men, since through these practices, masculinity is coupled with status and power. Another car-related trait to show masculinity is the way men drive in Qatar. Apart from being a necessary daily practice, driving for Qatari men is also a hobby. More specifically, they tend to engage in reckless and fast driving which is considered to be more masculine. However, not all of our participants agreed on this point, because they had also witnessed veiled and niqab-wearing women who engaged in this sort of driving. Certainly such driving practices are ubiquitous in Qatar, to the extent that some driving schools (such as Karwa Driving School), offer “defensive driving lessons” to their customers. We have interpreted this type of driving as a practice indexing powerfulness instead of masculinity, but given that the type of power evident in the public sphere is usually associated with men, it makes sense to assume that eventually this sort of driving will index masculinity (even on the part of women).

Qatari men further indicate their masculinity through their appearance. In particular, they demonstrate modesty by wearing a traditional garment known as thawb (an ankle-length long-sleeved shirt, similar to a robe). The thawb is usually tailored and made of white cotton. They distinguish themselves from other males by wearing expensive accessories, such as designer watches and cufflinks, expensive pens placed in the pocket of the thawb, and sun glasses. They also wear the ghutra (a white headscarf) and there are various ways of wearing it in order to express individuality and national identity. Both thawb and ghutra are white, though some men wear a yellow or blue thawb and a shamagh (a red-and-white checkered headscarf) during the winter months. In a class setting in Qatar, Qatari men express their masculinity by wearing their traditional garments. Western clothes, such as jeans or shorts, are not viewed as prototypical masculine clothes, even though a number of Qataris wear them in Qatar, especially when they drive their convertibles or motorcycles. Again, as in the case of women there is an interesting tension occurring here: on the one hand, the clothing repertoire is rather limited, given that all Qatari men are expected to wear their traditional national dress in everyday life, but at the same time they try to construct for themselves an individual –– or distinctive –– style or appearance through unique ways of mixing and matching accessories or tying up their ghutras (see ).Footnote45

In terms of physical appearance, masculinity in Qatar is demonstrated through facial hair, namely beard and mustache, and the way their hair and facial hair is groomed. Men go to barbershops on a regular basis for hair grooming. However, a number of religious (mainly Bedouin) men tend to have long beards, sometimes red or orange-colored with henna, in keeping with the Sunnah.Footnote46

Within the classroom setting, masculinity is perceived through respect for their instructors, which translates into students being diligent, attentive, and punctual. Qatari male students perceive themselves as gentlemen, and due to cultural expectations do not want to seem emasculated, especially when their instructor is of the opposite sex. Additionally, male students have freedom of choice regarding their studies as opposed to the cultural restraints on their female counterparts. This is evident through the way they carry themselves within the classroom and appear to take great interest in their school work. However, while they do not experience exam anxiety or obsession over grades, since they seem content with their scores, they always seek help and feedback for improvement. This is perhaps related to the notion of autonomy and lack of expression of emotions; the latter is usually associated with women. Societal expectations of men encourage the lack of expression of love, with the exception of spouses.Footnote47 They are the ones who are expected to act as breadwinners for the whole family.

Aside from their appearance, possession of cars, and education, Qatari men are more privileged in choosing a spouse, but due to their traditional and conservative society and in order to protect a woman’s virtue, female relatives have to initiate the process with the family of the prospective bride. This is in contrast with their female counterparts who are not able to choose their spouse although they have the freedom to refuse a potential spouse. Bedouin men tend to practise polygamy in order to demonstrate their masculinity within their tribal affiliation;Footnote48 in addition, having more offspring is perceived as more masculine, since offspring, and especially male offspring, are seen as the pledge for the continuation of the tribe. Qatari men can also pass on nationality to their children and their non-national wives, whereas women cannot do this. Consequently, women are encouraged to marry nationals in order to reinforce social norms within the state of Qatar.

Social, cultural, and religious norms prohibit premarital relations, although in some contexts, males demonstrate their masculinity by engaging in premarital relations; these, however, are considered to be underground practices. Since Qatar is a very conservative society, the social context is usually limited to the majlis (a space like a living room, where men meet every afternoon for discussion and/or to play videogames), and the khaima (tent) during camping. In some rare cases and in order to be perceived as “macho” among their rabaahum (close friends), their non-Qatari girlfriends accompany them to the khaima.

Overall, male supremacy is the norm within the Qatari culture, and males are perceived as the figures of authority (regardless of age) within the household and in professional environments. Despite the fact that the percentage of divorce in Qatar has increased significantly over the last decade, and that women have started becoming more independent financially, the ideal woman is still considered the one who prioritizes her family over her career and is obedient to her husband.

5 Western perspectives on gender roles

Growing up in New York and Athens respectively, both the authors were conscious of their feminine role and the societal expectation of their gender. These common traits were to be sensitive, caring, and to present themselves in a fashionable manner, favoring dresses over trousers, and playing with dolls instead of military-related toys.

Iglal Ahmed, in particular, was expected to be a “superwoman”, at least within her household. Coming from a highly-educated background where every family member was either a college professor, a geologist, or an engineer, she was therefore expected to follow in the footsteps of her parents and elder sibling, and as a young woman, was urged to work hard and become successful. Rather than embracing the traditional values of feminine traits as prescribed by American culture back in the 1950s, Iglal was encouraged to be ambitious and study as hard as, if not harder, than her male counterparts. During adulthood and throughout her undergraduate studies, she came to appreciate the roles ascribed to her by her parents, realizing how the fact that they encouraged her to pursue higher education and be successful and hardworking were no different from society’s expectations of masculine men. Masculinity themes in the United States include being successful, aggressive, self-reliant, and sexual.Footnote49 This was evident throughout Iglal’s university studies when she realized that her male counterparts were more promiscuous than females. Perhaps, females were just as promiscuous; however, due to societal expectations, females were less likely to discuss stories on “hooking up” after a night of partying, as opposed to the men.

Along the same lines but perhaps with less social “pressure”, Irene — due to her involvement from an early age with sports (which is still considered as a predominantly male-related activity) — learned to be ambitious and hardworking and to strive to be an achiever in all domains, including her academic and professional life. In the context of Greece, where gender-related traits and behaviors are distinctiveFootnote50 but are not necessarily articulated explicitly in public as happens in the US, aggressiveness, competitiveness and self-reliance are features that are part of Irene’s personality, but they are not necessarily considered to be gender-related; they are seen more as necessary for survival in the work environment. On the other hand, issues concerned with appearance are clearly gender-related, with women being expected to wear stylish and elegant clothing and shoes that highlight their sexuality but (according to Irene) reduce their comfort and mobility. Subsequently, and because she prioritizes work-related performance as opposed to highlighting femininity and subsequent sexuality in professional contexts, Irene considers it natural for women to dress modestly so that they do not stand out in terms of their femininity in the context of the work environment. In other contexts, such as when going out for entertainment purposes, her expectation is that women will want to highlight their femininity through their appearance and behavior, even though this femininity will again be filtered through the personality of the woman, resulting in various types and various degrees of femininity with which a woman feels comfortable.

Overall, despite the fact that both Iglal and Irene are considered (and consider themselves) Westerners they agree for the most part with the fact that masculinities and femininities entail different traits and practices; however the difference between them is that, for Iglal, these differences are more pronounced than for Irene, especially in the context of professional life.

6 Negotiating gender roles in the classroom

Having discussed how our students and we, as their instructors, view gender roles and the norms associated with them, it becomes evident that there is a major discrepancy in our respective perspectives, translating primarily into the fact that for us, women should have a more active role in the society. They are entitled to excel in both their family and their professional lives on a par with men, something that in general is not valid for our students given that women must give priority to their family-related duties. As a result, for us as Western instructors, engaging in gender role-related discussions is usually an exciting venture. On the other hand, it is at the same time challenging, given the different approach we take vis-à-vis the concept of gender and the subsequent roles we assign to each gender.

More specifically, we consider gender as a continuum between masculinities and femininities, which makes the identifying of gender identities less rigid than the way through which our students perceive them. For us, femininity can be more hybrid in the sense of accommodating a set of what our students would regard as “masculine” traits, such as self-decisiveness. In addition, what is considered as masculine for our students is not necessarily masculine for us: for example, when a woman wears jeans or when a woman is ambitious and successful in her career, this does not mean that she looks like a man or has adopted masculine traits.

In addition, what has become evident in our interaction, especially with our male students, is that there is a discrepancy in terms of the roles expected of women. More specifically, one of our male students told us that he had once had a nightmare about having to stay at home and cook for his family while waiting for his wife to come back from work. This reversal of the stereotypical roles associated with the two genders instilled in him a sense of breaking the social order found in the Islamic world, which he found hard to cope with. For both of us, such fixation with stereotypes is simply inconceivable and is exactly what we are trying to negotiate and, eventually, to render less rigid in our classrooms. Obviously we do not wish to impose on our students our values and our understanding of what gender means and how it can be used in society. Instead we try, through our classroom discussions, to encourage people to think critically about how their perspective on gender can affect their family, peers and, by extension, their society.

The way we usually go about negotiating gender roles is through discussion of gender-related behaviors from our respective cultures –– the students’ and our own –– that we consider as characteristic or, more interestingly, non-characteristic of the respective gender category. Some examples of these uncharacteristic examples include the stay-at-home father, who needs to take care of his newborn baby, while his wife goes to work after giving birth, or the female CEO, who sets the tone in the managing of the company by giving orders to and evaluating the performance of her (fe)male employees.

Such dialogues about gender-related issues are exciting ventures. Because a lot can be learned about each other’s cultures, norms, values, and belief systems we can, as a result, try to understand and interpret everyday life both inside and outside the university. For example, it was revealing for us to discover that in the past, Bedouin women had participated equally with men in physically demanding tasks such as milking camels or carrying wood. Such information has contributed towards breaking the stereotyped views we had held about the position of women and their respective roles in the Bedouin culture. Eventually, such exchanges of information and experience can contribute towards developing tolerant attitudes towards each other’s cultural peculiarities, thus enabling us to coexist in a harmonious environment.

In terms of the negotiating style per se, we usually apply what we call the dialogical infotainment approach. This translates as a pedagogical method aimed at educating each other, while at the same time entertaining each other through dialogue, performance, and visual aids. In this way, the power of knowledge and experience that each and every one of us enjoys is shared, instead of being used competitively; it is also used synthetically in order to construct a knowledge platform, from which the individuals involved can learn about each other’s (gender) cultures and thus stand a better chance of becoming sensitized and open-minded towards others. In this way, our approach shares the critical mode of Carbaugh’s cultural discourse analysis model, which includes the analyst’s deep engagement in descriptive and interpretive analyses as a way of gaining perspective on the importance, salience, or relevance of critical cultural inquiry.Footnote51 In terms of dialogue, we try to engage as many students as possible in our classroom discussions; we address them by their first names and encourage them to share stories with us from their personal lives that are relevant to the topics we discuss.

summarizes the concept of educational infotainment.

Figure 6: Dr Theodoropoulou with the Saudi Minister of Tourism at Medina, 2013 (© Irene Theodoropoulou)

In 2013 Irene presented a paper on the sociocultural meanings of traditional Qatari architecture at a conference in Medina in Saudi Arabia, organized by the Ministry of Tourism. As a Western female she had to live for a week wearing hijab, abiding by rules forbidding driving and visits to religious areas open only to Muslims, and frequenting places where there were only women. After the conference the Minister of Tourism invited the delegates to attend the opening of a cultural exhibition. While standing in a female-only zone, Irene enquired whether personally thanking the Minister for the hospitality provided to the conference delegates would be appropriate. Amused, the women she was with asked if she realized that she was a woman in Saudi Arabia. Later, however, having exchanged a few words about architecture with the Minister, she felt that her knowledge and respect for sociocultural and Islamic values, combined with her Greek values, had reinforced notions of overcoming stereotypes and aiming for intercultural communication, on the basis of what connects people rather than what separates them. This is how the encounter was framed in the context of the Intercultural Communication class in which it was later discussed.

After presenting our female students with this image and sharing the narrative, we asked them to discuss their reactions and the ways in which they could see the relevance of gender. Some students acknowledged Irene’s respect for local values and traditions of Saudi Arabia, indexed through her adoption of traditional female attire, while others commented on the exolinguistic features of the picture, and more specifically on the fact that the distance between her and the Minister was about right –– it was formal, but not too formal. Others noted the difference in terms of facial expressions; both the Minister and Irene were smiling, while the security guard in the background looked somewhat forbidding. All of these interesting dimensions were discussed by the students, who tried to paint a psychological portrait of the figures in the picture, as well as between the students and us, as instructors. It turned out that many students considered this incident an entertaining break in the sharp boundary of gender segregation, due to the fact that it was initiated by a Western female, an outsider: it was thus not a representative sample of female Islamic values in the Gulf countries, especially Saudi Arabia and Qatar, according to which women are not supposed to strike up conversations with male strangers, regardless of their rank.

Linguistically speaking, our students expressed this general idea through the use of hedging (e.g. discourse markers, like “maybe”, “like”, “it seems that … ”, “I think that … ”, among others), when addressing us.Footnote52 However, when they spoke with each other and negotiated the meaning of the picture, they tended to sound much more upfront and direct, indexed through the lack of mitigation and the attempt to overlap with each other and to raise their voices in order to make themselves heard and, hence, more dominant, than their interlocutors. This is in alignment with the competitiveness discussed earlier. These performances, which were primarily in English, were often enriched with codeswitching in Arabic through utterances in the students’ native dialects, which aimed at easing the tensions that were created in cases of disagreements, and also at establishing an entertaining tone. Analysis of these is, however, beyond the scope of this paper.

Overall, through this dialogue and in the context of educational infotainment, both the students and the instructors tried to negotiate the content of the femininity and masculinity discourses by drawing on “common sense”, namely their everyday thinking –– intuitive, without forethought or reflection.Footnote53 Knowing that there was always the danger of commonsense assumptions contributing in varying degrees to sustaining unequal power relations,Footnote54 we tried to minimize this by offering our students the floor to reflect on it, and thereby to employ their power in order to make their ideas audible in the classroom context.Footnote55 In this way, the concept of power per se began to be negotiated and to have an impact on the very description and subsequent negotiation of gender discourses. Furthermore, such discourses gained a more fluid, open-ended and hence dynamic content, a reflection of the shifting socioeconomic and ideological background of Qatar as a result of the forces of globalization.

7 Conclusion

In this concluding discussion, we reflect on how power interacts with the discourses of Qatari femininities and masculinities in educational infotainment. Instead of employing what are often opposing views, in order to highlight differences in terms of how we and our students perceive gender-related roles and thus create unbridgeable gaps in our communication, we use these differences as our point of departure and stimulus in our educational infotainment approach. The latter, we hope, will trigger interesting and enthusiastic responses on the part of our students in the context of a healthy discussion in class, from which we, as instructors, can also benefit by familiarizing ourselves with their gender-related customs and values.

Accordingly, it can be argued that as instructors, we share the institutional power that we have with our students in order to empower them by encouraging them to express their opinions and to embrace (instead of rejecting) any intercultural communicative differences they might have. At the same time, our students empower us by sharing with us their knowledge of the cultural particularities associated with their perception of gender in Qatar. Hence, such a critical intercultural communicative viewpoint on gendered cultures can eventually help all of us to learn from each other in a balanced way. This is the core of our argument. It can be seen as our contribution to the debate on how to improve intercultural dialogue by moving beyond merely tolerating the Other, and instead, essentially situating deeply-shared understandings, as well as new forms of creative and expressive communication, as dialogic outcomes in the university classroom.Footnote56

At the macro-level of the organization of the social structure, we consider such an approach a useful pathway towards leading people from different genders to understand each other and, hence, to create the circumstances for co-existing harmoniously in their societies. At the meso-level of the institutional organization of our workplace, such a pedagogical approach, which has so far worked reasonably successfully for us both, can be seen as an engaging way to maintain both our own and our students’ motivation at a high level in the classroom. In this way, critical thinking skills of both students and instructors can develop without any hierarchical organization and preference. Hence one can argue that the university can achieve its target, which is to contribute towards the enhancement of transferable skills to students (and instructors); this will enable them to become responsible, active and helpful citizens for their communities. Finally, at the micro-level of everyday interaction, educational infotainment helps all of us to expand our sociocultural horizons. In this way, both groups can gain more knowledge, flexibility and linguistic skills, which will help them to become more efficient and cosmopolitan intercultural communicators.

Future research on this topic might well consider examining how to translate this theoretical knowledge into tangible steps towards bridging the gap between genders in Qatar.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Irene Theodoropoulou

Irene Theodoropoulou is Associate Professor of Sociolinguistics in the Department of English Literature and Linguistics, Qatar University, PO Box 2713, Doha, Qatar

Iglal Ahmed

Iglal Ahmed is Lecturer in Advanced Reading and Translation at the same department, [email protected].

Notes

1 Berry et al., Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications (2011), p. 471.

2 Scharfenort, “Urban Development and Social Change in Qatar: The Qatar National Vision 2030 and the 2022 FIFA World Cup”, Journal of Arabian Studies 2.2 (2012), pp. 209–30; Theodoropoulou and Alos, “Expect Amazing! Branding Qatar as a Sports Tourism Destination”, Visual Communication (2018).

3 There are no official statistics on the number of citizens, but this estimate is more credible than the lower ones often mentioned but now outdated, in light of historical data and estimated natural growth rates (see e.g. Onn Winckler, “How many Qatari nationals are there?”, Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2015, www.meforum.org/articles/2015/how-many-qatari-nationals-are-there).

4 Piller, Intercultural Communication: A Critical Introduction (2011), p. 8.

5 Halualani and Nakayama, “Critical Intercultural Communication Studies: At a Crossroads”, The Handbook of Critical Intercultural Communication, ed. Nakayama and Halualani (2013), pp. 1–3.

6 Bjerregaard et al., “A Critical Analysis of Intercultural Communication Research in Cross-Cultural Management: Introducing Newer Developments in Anthropology”, Critical Perspectives on International Business 5.3 (2009), p. 214.

7 Fairclough, Language and Power (2015), p. 73.

8 See Raddawi, Intercultural Communication with Arabs: Studies in Education, Professional, and Societal Contexts (2015).

9 Albirini, Modern Arabic Sociolinguistics: Diglossia, Variation, Codeswitching, Attitudes and Identity (2016), p. 189. However, see: Sadiqi, Women, Gender and Language in Morocco (2003); Sadiqi, “Language and Gender”, Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, ed. Versteegh et al. (2006), pp. 64–50; Vicente, “Gender and Language Boundaries in the Arab World: Current Issues and Perspectives”, Estudios de Dialectologia Norteafricana y Andalousi 13 (2009); Pollard, “The Role of Women”, Understanding the Contemporary Middle East, ed. Schwedler (2013), pp. 345–76.

10 Cameron, “Gender and the English Language”, The Handbook of English Linguistics, ed. Aarts and McMahon (2006), p. 724.

11 Butler, Gender and Trouble: Feminism and The Subversion of Identity (1990), pp. 8–12, 25.

12 Tannen, Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk Among Friends (2005); Tannen, You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (2007).

13 See: Coates, Women, Men and Language (Citation2004), chap. 9.

14 Halualani and Nakayama, “Critical Intercultural Communication Studies: At a Crossroads”, The Handbook of Critical Intercultural Communication, ed. Nakayama and Halualani (2010), p. 7.

15 Al-Ajmi, “The Effect of Personal Characteristics on Job Satisfaction: A Study Among Male Managers in the Kuwait Oil Industry”, International Journal of Commerce and Management 11.3/4 (2001), pp. 91–110.

16 Omar and Davidson, “Women in Management: A Comparative Cross-Cultural Overview”, Cross-Cultural Management: An International Journal 8.3/4 (2001), pp. 35–67.

17 Tlaiss, “Impact of Parental Communication Patterns on Arab Women’s Choice of Careers. Case Study: Lebanon”, Intercultural Communication with Arabs: Studies in Education, Professional, and Societal Contexts, ed. Raddawi (2015), p. 272.

18 E.g. Goby and Erogul, “Female Entrepreneurship in the United Arab Emirates: Legislative Encouragements and Cultural Constraints”, Women’s Studies International Forum 34.4 (2011), pp. 329–34.

19 Pringle and Mallon, “Challenges for the Boundaryless Career Odyssey”, International Journal of Human Resource Management 14.5 (2011), pp. 839–53; Gardner, “Gulf Migration and the Family,” Journal of Arabian Studies 1.1 (2011), pp. 3–25.

20 See: Jandt, An Introduction to Intercultural Communication Identities in a Global Community (2012), chap. 8.

21 Sharabi, Neopatriarchy: A Theory of Distorted Change in Arab Society (1988).

22 Krauss, The Persistence of Patriarchy: Class, Gender, and Ideology in Twentieth Century Algeria (1987), p. xii; Joseph, “Patriarchy and Development in the Arab World”, Gender and Development 4.2 (1996), pp. 14–19.

23 For an historic overview, see: Potter, “Society in the Persian Gulf: Before and After Oil”, CIRS Occasional Paper 18 (2017), pp. 22–4.

24 Tlaiss, “Impact of Parental Communication Patterns on Arab Women’s Choice of Careers”, p. 265.

25 Rampton et al., “UK Linguistic Ethnography: A Discussion Paper” (2004); Tusting and Maybin, “Linguistic Ethnography and Interdisciplinarity: Opening the Discussion”, Journal of Sociolinguistics 11.5 (2007), pp. 575–83.

26 Spradley, Participant Observation (1980); Gee, An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method (2014).

27 Whitehead, “Basic Classical Ethnographic Research Methods. Secondary Data Analysis, Fieldwork, Observation/Participant Observation, and Informal and Semi‐structured Interviewing”, Ethnographically Informed Community and Cultural Assessment Research Systems (2005), pp 15–19.

28 Holmes, Gendered Talk at Work: Constructing Gender Identity Through Workplace Discourse (2008)

29 See: Wood, Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender, and Culture (2012).

30 See: Beal, Boys and Girls: The Development of Gender Roles (1994).

31 Spence and Buckner, “Instrumental and Expressive Traits, Trait Stereotypes, and Sexist Attitudes: What Do They Signify?”, Psychology of Women Quarterly 24.1 (2000), pp. 44–53.

32 Kimmel, Manhood in America: A Cultural History (2011); Milani, “Theorizing Language and Masculinities”, Language and Masculinities: Performances, Intersections, Dislocations, ed. Milani, pp. 8–33.

33 Wood, “Feminist Standpoint Theory and Muted Group Theory: Commonalities and Divergences”, Women and Language 28.2 (2005), p. 61; Tannen, You Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (2007); Theodoropoulou, “Intercultural Communicative Styles in Qatar: Greek and Qataris”, Intercultural Communication with Arabs: Studies in Educational, Professional and Societal Contexts, ed. Raddawi (2015a), pp. 11–26.

34 Tannen, You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (2007), chapter 3.

35 See: Lazare and Kramarae, “Gender and Power in Discourse”, Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, ed. van Dijk (2001), pp. 226–34.

36 Abu-Lughod, Veiled Sentiments: Honor and Poetry in Bedouin Society (1986), pp. 85–117.

37 Said and Kaplowitz, “Attributional Biases in Individualistic and Collectivistic Cultures: A Comparison of Americans with Saudis”, Social Psychology Quarterly 56.3 (1993), pp. 223–33; Kafaji, The Psychology of the Arab: The Influences That Shape an Arab Life (2011), p. 31.

38 Al-Amadidhi, Lexical and Sociolinguistic Variation in Qatari Arabic (1985); Theodoropoulou, “Sociolinguistic Anatomy of Mobility: Evidence from Qatar”, Language & Communication 40 (2015), pp. 52–66.

39 See: Rahman et al., “Exploring the Meanings of Hijab Through Online Comments in Canada”, Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 45.3 (2016), pp. 1–19.

40 See: Lewis, “Marketing Muslim Lifestyle: A New Media Genre”, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 6.3 (2010), pp. 68–74.

41 Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990), p. 25

42 See: Matsumoto, “Alternative Femininity: Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People”, Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People, ed. Okamoto and Smith (2004), pp. 240–55.

43 A traditional outdoor mall which consists of shops, restaurants, and shisha (water pipe) cafés.

44 See: Bourdieu, Distinctions: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (1984), pp. 466–84.

45 See: Irvine, “‘Style’ as Distinctiveness: The Culture and Ideology of Linguistic Differentiation”, Style and Sociolinguistic Variation, ed. Eckert and Rickford (2001), pp. 21–43.

46 Verbally transmitted record of the teachings, deeds, and sayings of the Muslim prophet Muhammed.

47 See: Oghia, “Different Cultures, One Love: Exploring Romantic Love in the Arab World”, Intercultural Communication with Arabs. Studies in Educational, Professional and Societal Contexts, ed. Raddawi (2015), pp. 279–94.

48 See: Abu-Lughod, Veiled Sentiments: Honor and Poetry in Bedouin Society (1986).

49 Wood, “Feminist Standpoint Theory and Muted Group Theory: Commonalities and Divergences”, Women and Language 28.2 (2005), p. 61.

50 E.g. Mihail, “Gender-Based Stereotypes in the Workplace: The Case of Greece”, Equal Opportunities International 25.5 (2006), pp. 373–88.

51 Carbaugh, “Cultural Discourse Analysis: Communication Practices and Intercultural Encounters”, Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 36.3 (2007), p. 173.

52 See: Lakoff, “Linguistic Theory and the Real World”, Language Learning 25.2 (1975), pp. 309–38.

53 Fairclough, Language and Power (2015), p. 13.

54 Ibid., p. 107.

55 See Theodoropoulou, “Impact of Undergraduate Language and Gender Research: Challenges and Reflections in the Context of Qatar”, Gender Studies 16.1 (2018), pp. 71–86.

56 See Ganesh and Holmes, “Positioning Intercultural Dialogue: Theories, Pragmatics, and an Agenda”, Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 4.2 (2011), p. 81.

Bibliography

- Abu-Lughod, Leila, Veiled Sentiments: Honor and Poetry in Bedouin Society (Berkeley CA: University of California Press 1986).

- Al-Ajmi, Rashed, “The Effect of Personal Characteristics on Job Satisfaction: A Study Among Male Managers in the Kuwait Oil Industry”, International Journal of Commerce and Management 11.3–4 (2001), pp. 91–110. doi: 10.1108/eb047429

- Al-Amadidhi, Darwish G.H.Y., Lexical and Sociolinguistic Variation in Qatari Arabic, PhD dissertation (University of Edinburgh, 1985).

- Albirini, Abdulkafi, Modern Arabic Sociolinguistics: Diglossia, Variation, Codeswitching, Attitudes and Identity (New York: Routledge, 2016).

- Beal, Carole R., Boys and Girls: the Development of Gender Roles (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994).

- Berry, John W., Ype H. Poortinga, Seger M. Breugelmans, Athanasios Chasiotis, and David L. Sam, Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Bjerregaard, Toke; Jakob Lauring; and Anders Klitmøller, “A Critical Analysis of Intercultural Communication Research in Cross-Cultural Management: Introducing Newer Developments in Anthropology”, Critical Perspectives on International Business 5.3 (2009), pp. 207–28. doi: 10.1108/17422040910974695

- Bourdieu, Pierre, Distinctions: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, translated by Richard Nice (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984).

- Butler, Judith, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990).

- Cameron, Deborah, “Gender and the English Language”, The Handbook of English Linguistics, edited by Bas Aarts and April McMahon (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2006), pp. 724–41.

- Carbaugh, Donal, “Cultural Discourse Analysis: Communication Practices and Intercultural Encounters”, Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 36.3 (2007), pp. 167–82. doi: 10.1080/17475750701737090

- Coates, Jennifer, Women, Men and Language (London: Pearson Longman, 2004).

- Fairclough, Norman, Language and Power, 3rd edn (London: Routledge, 2015).

- Ganesh, Shiv and Prue Holmes, “Positioning Intercultural Dialogue: Theories, Pragmatics, and an Agenda”, Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 4.2 (2011), pp. 81–86. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2011.557482

- Gardner, Andrew M., “Gulf Migration and the Family”, Journal of Arabian Studies 1.1 (2011), pp. 3–25. doi: 10.1080/21534764.2011.576043

- Gee, James P., An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method (New York: Routledge, 2014).

- Goby, Valerie P. and Murat Erogul, “Female Entrepreneurship in the United Arab Emirates: Legislative Encouragements and Cultural Constraints”, Women’s Studies International Forum 34.4 (2011), pp. 329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2011.04.006

- Halualani, Rona T. and Thomas Nakayama, “Critical Intercultural Communication Studies: at a Crossroads”, The Handbook of Critical Intercultural Communication, edited by Thomas K. Nakayama and Rona T. Halualani (Oxford: Wiley/Blackwell 2013), pp. 1-16.

- Holmes, Janet, Gendered Talk at Work: Constructing Gender Identity Through Workplace Discourse 3 (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell 2008).

- Irvine, Judith T., “‘Style’ as Distinctiveness: the Culture and Ideology of Linguistic Differentiation”, Style and Sociolinguistic Variation, edited by Penelope Eckert and John R. Rickford (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2001), pp. 21–43.

- Jandt, Fred, An Introduction to Intercultural Communication Identities in a Global Community (London: Sage 2012).

- Joseph, Suad, “Patriarchy and Development in the Arab World”, Gender and Development 4.2 (1996), pp. 14–19. doi: 10.1080/741922010

- Kafaji, Talib, The Psychology of the Arab: The Influences That Shape an Arab Life (Bloomington IN: Author House 2011).

- Kimmel, Michael, Manhood in America: A Cultural History (New York: Free Press 1995).

- Krauss, Jennifer, The Persistence of Patriarchy: Class, Gender, and Ideology in Twentieth Century Algeria (New York: Praeger 1987).

- Lakoff, Robin T., “Linguistic Theory and the Real World”, Language Learning 25.2 (1975), pp. 309–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1975.tb00249.x

- Lazare, Michele and Cheris Kramarae, “Gender and Power in Discourse”, Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, edited by Teun van Dijk (London: Sage 2011), pp. 217–40.

- Lewis, Reina, “Marketing “Muslim Lifestyle: A New Media Genre”, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 6.3 (2010), pp. 58–90. doi: 10.2979/MEW.2010.6.3.58

- Matsumoto, Yoshiko, “Alternative Femininity. Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People”, Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People, edited by Shigeko Okamoto and Janet Smith (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2004), pp. 240–55.

- Mihail, Dimitrios, “Gender-Based Stereotypes in the Workplace: The Case of Greece”, Equal Opportunities International 25.5 (2006), pp. 373–88. doi: 10.1108/02610150610706708

- Milani, Tommaso M., “Theorizing Language and Masculinities”, Language and Masculinities: Performances, Intersections, Dislocations, edited by Tommaso Milani (London: Routledge 2015), pp. 8–33.

- Oghia, Michael J., “Different Cultures, One Love: Exploring Romantic Love in the Arab World”, Intercultural Communication with Arabs. Studies in Educational, Professional and Societal Contexts, edited by Jillian Schwedler (New York: Springer 2015), pp. 279–94.

- Omar, Azuma and Marilyn J. Davidson, “Women in Management: A Comparative Cross-Cultural Overview”, Cross-Cultural Management: An International Journal 8.3–4 (2001), pp. 35–67. doi: 10.1108/13527600110797272

- Piller, Ingrid, Intercultural Communication: A Critical Introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 2011).

- Pollard, Lisa, “The Role of Women”, Understanding the Contemporary Middle East, edited by Jillian Schwedler (Boulder CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers 2013), pp. 345–76.

- Potter, Lawrence G., “Society in the Persian Gulf: Before and After Oil”, CIRS Occasional Paper 18 (2017), pp. 1–45.

- Pringle, Judith K. and Mary Mallon, “Challenges for the Boundaryless Career Odyssey”, International Journal of Human Resource Management 14.5 (2003), pp. 839–53. doi: 10.1080/0958519032000080839

- Raddawi, Rana (ed.), Intercultural Communication with Arabs: Studies in Education, Professional, and Societal Contexts (New York: Springer 2015).

- Rahman, Osmud, Benjamin Fung and Alexia Yeo, “Exploring the Meanings of Hijab Through Online Comments in Canada”, Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 45.3 (2016), pp. 1–19. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2016.1171795

- Rampton, Ben; Karin Tusting; Janet Maybin; Richard Barwell; Angela Creese; and Vally Lytra, “UK Linguistic Ethnography: A Discussion Paper” (2004), available online at www.lancaster.ac.uk/fss/organisations/lingethn/documents/discussion_paper_jan_05.pdf.

- Sadiqi, Fatima, Women, Gender and Language in Morocco (Leiden: Brill 2003).

- Sadiqi, Fatima, “Language and Gender”, Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, edited by Kees Versteegh, Mushira Eid, Alaa Elgibali, Manfred Woidich and Andrzej Zaborski (Leiden: Brill 2006), pp. 642–50.

- Said, Saad S. and Stan A. Kaplowitz, “Attributional Biases in Individualistic and Collectivistic Cultures: A Comparison of Americans with Saudis”, Social Psychology Quarterly 56.3 (1993), pp. 223–33. doi: 10.2307/2786780

- Scharfenort, Nadine, “Urban Development and Social Change in Qatar: The Qatar National Vision 2030 and the 2022 FIFA World Cup”, Journal of Arabian Studies 2.2 (2012), pp. 209–30. doi: 10.1080/21534764.2012.736204

- Sharabi, Hisham, Neopatriarchy: A Theory of Distorted Change in Arab Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1988).

- Spence, Janet T. Camille E. Buckner, “Instrumental and Expressive Traits, Trait Stereotypes, and Sexist Attitudes: What Do They Signify?”, Psychology of Women Quarterly 24.1 (2000), pp. 44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01021.x

- Spradley, James P., Participant Observation (New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston 1980).

- Tannen, Deborah, You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (London: Virago 2007).

- Tannen, Deborah, Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk Among Friends (New York: Oxford University Press 2005).

- Theodoropoulou, Irene, “Intercultural Communicative Styles in Qatar: Greek and Qataris”, Intercultural Communication with Arabs; Studies in Educational, Professional and Societal Contexts, edited by Rana Raddawi (New York: Springer 2015), pp. 11–26.

- Theodoropoulou, Irene, “Sociolinguistic Anatomy of Mobility: Evidence from Qatar”, Language and Communication 40 (2015), pp. 52–66. doi: 10.1016/j.langcom.2014.12.010

- Theodoropoulou, Irene, “Impact of Undergraduate Language and Gender Research: Challenges and Reflections in the Context of Qatar”, Gender Studies 16.1 (2018), pp. 71–86. doi: 10.2478/genst-2018-0007

- Theodoropoulou, Irene and Julieta Alos, “Expect Amazing! Branding Qatar as a Sports Tourism Destination”, Visual Communication (2018).

- Tlaiss, Hayfaa A. “Impact of Parental Communication Patterns on Arab Women’s Choice of Careers. Case Study: Lebanon”, Intercultural Communication with Arabs: Studies in Education, Professional, and Societal Contexts, edited by Rana Raddawi (New York: Springer 2015), pp. 261–78.

- Tusting, Karin and Janet Maybin, “Linguistic Ethnography and Interdisciplinarity: Opening the Discussion”, Journal of Sociolinguistics 11.5 (2007), pp. 575–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00340.x

- Vicente, Angeles, “Gender and Language Boundaries in the Arab World: Current Issues and Perspectives”, Estudios de Dialectologia Norteafricana y Andalousi 13 (2009), pp. 7–30.

- Whitehead, Tony L., “Basic Classical Ethnographic Research Methods: Secondary Data Analysis, Fieldwork, Observation/Participant Observation, and Informal and Semi-Structured Interviewing”, EICCARS Working Paper Series (2005), pp. 1–28, available online at: www.cusag.umd.edu/documents/workingpapers/classicalethnomethods.pdf.

- Wood, Julia T., “Feminist Standpoint Theory and Muted Group Theory: Commonalities and Divergences”, Women and Language 28.2 (2005), pp. 61–4.

- Wood, Julia T., Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender and Culture, 10th edn (Boston MA: Cengage Learning 2012).