Abstract

In 1959, a Danish anthropological expedition to Qatar created hundreds of photographs and a 16-minute film depicting the diversity of Qatari lifestyles, which included strong evidence of a Bedouin past, separate from the merchant and pearl-diving culture of the coast. However, Qatar’s new national museum, still under development, has been working on a different narrative: a more unified national identity that emphasizes the similarities of Qatari heritage rather than the differences. Artifacts such as these photos and film can become inconvenient when they do not fit new and improved civic myths, yet as some of the most important (and well known) surviving images of Qatar’s heritage, this evidence cannot be left out. How might the museum make use of the evidence so that it aligns with its narrative? Here we focus on the aesthetic style of Jette Bang’s photographs and film, which emphasizes the warmth, hospitality, and universal humanity of Qatari heritage. Our argument connects the historical and ideological contexts for both the new national museum’s push for a unity narrative and Bang’s 1959 photographs and film. We suggest that the artistic elements of these ostensibly scientific and historical artifacts may offer Qatar’s new museum a way to repurpose them without jeopardizing a narrative of national unity.

1 Introduction

Every nation must craft a story about its nationhood to make its legitimacy and imagined sense of community legible and clear for its citizens.Footnote1 This story, as Peggy Levitt argues, is often best portrayed through cultural institutions such as national museums.Footnote2 The resource-rich states of the Arabian Peninsula are no exceptions to this rule; in fact, recent work has emphasized the connection between museums, heritage, and nationalism in the region.Footnote3

Yet to connect the dots in a national history, one must first have dots. Intangible cultural heritage is important,Footnote4 but throughout the world, including in the Arabian Peninsula, museums privilege the object.Footnote5 However, once an object becomes part of the historical record, it can take on a life of its own. Here we explore the possibility that objects and images –– artifacts –– can become inconvenient when they do not fit new and improved civic myths, using the example of the new national museum of Qatar to suggest ways in which old media can be repurposed for new narratives.

Qatar, a small and resource-rich monarchy on the shores of the Persian Gulf, is a useful case study for this investigation, given the country’s relative youth and the concurrent desire to showcase its history to local and global audiences. The political leadership of Qatar privileged material objects as integral aspects of the national narrative even before formal independence in 1971. This drive to discover and display Qatari history can be seen as a direct rebuttal to typical Western historical scholarship on the country, typified by Zahlan’s brief assessment that Qatar “had played a minor and obscure role throughout the turmoil of the centuries”.Footnote6 It also serves as a response to dismissive and even condescending attitudes by some of its fellow Gulf neighbors about Qatar’s place in history (e.g., Bahrain’s 1997 counter-memorial to the International Court of Justice).Footnote7 While we must be careful, as Exell and Rico caution, to avoid the orientalist viewpoint that Qatar has no history,Footnote8 it is true that compared to other Gulf states, Qatar has left relatively few archaeological or historical marks on the world stage.Footnote9 We should interpret Qatar’s impulse to unearth and display artifacts as a strong political response to perceived gaps in the historical record of the country.

Qatar has welcomed various international archaeological teams to carry out excavations: the Danish from 1956 to 1964;Footnote10 the British in 1973–4;Footnote11 the French in 1976;Footnote12 and, most recently, the Danish again, with the University of Copenhagen–Qatar Museums partnership in the excavations of al-Zubarah, 2009–14.Footnote13 All of these expeditions prioritized the recovery of tangible objects for public display, sometimes above research and preservation purposes. For example, the recent al-Zubarah excavation created tension between the Danish archaeological team and Qatar Museums, which took hundreds of artifacts for possible insertion in the new national museum despite ongoing analysis of the project and its findings.Footnote14 In summary, Qatar has worked hard to amass a trove of tangible artifacts to prove to a skeptical external world (and a receptive local audience) that the country has an established and important history.

In this work, we focus on the anthropological expedition from Denmark in 1959, which created hundreds of photographs and a sixteen-minute film.Footnote15 These historical artifacts depict the diversity of Qatari lifestyles of the past, in contrast to the unified identity narrative of the new national museum (still under development), which seeks to attenuate the historical differences between Qataris and emphasize the similarities. Yet due to the importance of these images for the tangible historical record of Qatar, and Qatar Museums’ high regard for the photographs and film from the Danish expedition, we assume that these artifacts will be used somehow. So, we ask: What will the new museum do with key pieces of evidence that do not necessarily fit the new narrative? Or, more precisely, how will the museum make use of the evidence in relation to its theory?

We suggest that there is a way for the new national museum to repurpose these historical documents that preserves the tangible heritage while also promoting new narratives. Our analysis focuses on the work of Jette Bang, specifically Beduiner, a documentary of Bedouin culture, as well as her photographs, collected during the 1959 Danish expedition led by ethnographer Klaus Ferdinand. Beduiner is the most important surviving visual evidence of Qatar’s Bedouin culture as separate from the merchant and pearl-diving culture of the coast. Yet Bang’s visual style, which emphasized the warmth and hospitality of the various cultures she documented (including the Inuit of Greenland) –– an aesthetic strategy encouraged by Peter Glob, the Danish archaeologist in charge of the Gulf expeditionsFootnote16 –– provides a clue as to how these images may be successfully repurposed for the new narrative. We suggest that if her aesthetic style in these anthropological documents can be mobilized to show that Bedouin culture is not “other” but instead “us”, then the images might fit into the museum’s mission. Our argument will therefore connect the historical and ideological contexts for both the new national museum’s push for a unity narrative and for Bang’s 1959 photographs and film. We propose that the artistic elements of these ostensibly scientific and historical artifacts may offer Qatar’s new museum a way to repurpose them without jeopardizing a narrative of national unity.

2 Problem: Qatari heterogeneity

After undergoing bouts of refurbishing throughout the 2000s, the national museum of Qatar has been closed and under complete renovation and reconstruction since 2007. The new museum’s opening date has been delayed for years: it was originally set to open in 2012,Footnote17 a date which was then changed to 2014,Footnote18 then 2016,Footnote19 and then 2018.Footnote20 Currently, the promise is to open in March 2019,Footnote21 although it should not be surprising if this date is once again delayed.Footnote22 Although the official price tag of the project is a closely guarded secret, a recent estimate put the cost at $434 million –– and that may be just for the physical structure itself.Footnote23 In other words, the state of Qatar, through Qatar Museums, has invested a huge amount of time and money into getting this project just right.

But why? Yes, national museums are used by all countries to craft their civic stories and inculcate their versions of national identity and history. Nevertheless, the level of investment displayed by Qatar might be confusing to an outside observer. Much of the academic literature focuses on the relative homogeneity of the Qatari population,Footnote24 the citizens’ political apathy,Footnote25 and the large influx of resource-wealth distribution to these citizens that fuels this domestic peace.Footnote26 Is nation-building really necessary under these conditions? To compound the mystery, in 2016 Qatar faced its first budget shortfall in fifteen years, necessitating belt-tightening across a wide range of government benefits, services, and jobs.Footnote27 Yet amid major layoffs in the oil and gas industry, construction delays in infrastructure, and several Qatar Museums projects put on hold, the new national museum has received state-backed priority to maintain its trajectory. That the first public appearance of the Emir of Qatar, H.H. Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, after the beginning of the regional diplomatic crisis in June 2017, was at the construction site of the new national museum is politically striking.Footnote28 It is clear that the Qatari political leadership sees the new national museum as a top priority.

The reason for this massive investment of time and money becomes clearer when we recognize that –– far from the internal homogeneity perceived by outsiders –– the Qatari citizenry is differentiated by sectarianism, ethnic origin, and cultural lifestyle, and that these divisions cause social and political tension. Qatari society –– like all of the Arab states in the Persian Gulf –– is divided by religious sectarianism: although its citizens are all Muslims, some are Sunnī and some are Shīʿa.Footnote29 Qataris are also divided based on geographic origin –– from Arabia, Persia, or Africa –– resulting in up to eight categories of ethnic social structures.Footnote30

Yet most importantly for our purposes, Qataris are divided by three cultural pasts. Despite a modern population that is overwhelmingly urbanized, with more than 90% of the population residing in metropolitan Doha alone,Footnote31 Qataris define themselves in relation to the lifestyles of their ancestors: a settled lifestyle on the coasts (ḥaḍar), a Bedouin lifestyle in the desert (badū), or a mixture of the two lifestyles (badū-mutaḥaḍar, or a dualistic lifestyle).Footnote32

It was common for outside observers to recognize only two of these three lifestyles: the settled ḥaḍar communities of the coast, which engaged in merchant trade and pearl diving, and the nomadic badū communities of the desert, which herded their camels and moved their tents from place to place. There is much historical evidence about the lifestyle divisions –– and social tensions –– between the coastal settlements and the nomadic Bedouin. For example, while on a brief visit to Qatar in the mid-1950s, the archaeologist Geoffrey Bibby described the coastal towns’ need for security to protect against the mainland Bedouin tribes. Unprotected, the coastal settlements could be –– and sometimes were –– the victims of theft by Bedouin who did not feel like bartering for whatever they needed.

[T]he armoured vehicles only served to emphasize the fact that Qatar was part of mainland Arabia and had very different police aims from Bahrain. Here was no problem of checking petty theft or keeping an eye on political hotheads. Here was the age-old question of the relative strength of the townsfolk and of the desert nomads. The desert of Qatar, within sight of the coastal villages, formed part, and merely part, of the grazing grounds of powerful Bedouin tribes, the Na’im, the Manasir, and above all the Murra, whose range went deep into Saudi Arabia, as far as the oasis of Jabrin, 200 miles from the coast. These nomad tribes had never given more than nominal allegiance to the sheikhs of the coastal towns.Footnote33

To summarize, the cultural history of family lifestyles, whether Bedouin, coastal, or a mix of the two, remains preserved in modern-day Qatari conceptions of their heritage, even if virtually everyone now lives in a three-story villa instead of a portable tent and drives cars instead of camels.Footnote37 These cultural traditions form a family’s identity, influence their daily practices, and matter for the social opportunities available to them. Furthermore, these cultural distinctions spur internal political and social issues, including a class system that can create social barriers to intermarriage between different groups of citizens,Footnote38 and a political stalemate over which citizens would have the right to vote in future legislative elections.Footnote39 In other words, the cultural divide remains a potential obstacle to a unified Qatari identity today.

3 Solution (and more problems): Qatar national museum’s unity narrative

Given the divisions in Qatari society along sectarian, ethnic, and cultural lines, the reason for the Qatari government’s immense investment of time and money into the new national museum becomes clearer: the government has prioritized the development of a new national narrative as a crucial part of the country’s development toward a more unified citizenry. An interview with a member of the National Museum’s oral history project, conducted in 2013, emphasized the importance of getting the narrative right for Qatar’s nation-building goals.

It’s about … national unity, about bringing people together, rather than giving them points of conflict. And that’s why this museum is so important, because it represents the focal point, the pinnacle, of Qatari civilization, and the message that they want to present to the world.Footnote40

Additional interviews conducted in 2014 shed light on the specific content of the new national narrative under development: one that focuses on the dualistic lifestyle of Qataris in an effort to attenuate rather than emphasize the differences between the coastal and desert communities of Qatar. In interviews with the head curator and the head of collections of the national museum, the development of a national narrative of “duality” to represent Qatar’s past was described:

We are Qatari people: We have our camels, but we also have our dhows [pearling boats] … . We need the people to know this. We were not always Bedouin only, or only part of the fishing villages. We were all together … . Part of the time we live here, part of the time we live there. We live the duality life.Footnote42

Rather than this notion that we were separated into two communities at the same time, instead we are emphasizing that we are one people.Footnote43

This narrative deemphasizes two of the three distinctive cultural heritages of Qatar (ḥaḍar and badū) in favor of focusing on the dualistic lifestyle, in which Qataris moved back and forth between the desert and the coast depending on the seasons and the lifestyle needs of the community. While this narrative describes an actual lifestyle of Qatari heritage, it makes the political choice to promote national unity by emphasizing only this lifestyle, creating a new version of the Qatari national identity narrative that follows miriam cooke’s analysis of the “tribal modern”: a “national brand that combines the spectacle of tribal and modern identities and cultures”.Footnote44

The narrative of duality is supported by the physical layout of the new national museum, which is divided into two temporary galleries and eleven permanent galleries, the latter of which flow from one gallery to the next in a guided path through Qatar’s history.Footnote45 With the construction nearing an end, the permanent galleries are divided into three “acts” or “chapters”: the archaeology, flora and fauna, and environment of Qatar (Galleries 1–3), life in Qatar (Galleries 4–7), and the historical narrative of Qatar from 1500 to the present day (8–11), ending with the Old Emiri Palace (and site of the original national museum).

For the purposes of our argument, we will focus in particular on Galleries 4, 5, and 6. Our tour guides referred to this set of galleries as “life in summer and winter”, emphasizing that the desert lifestyle would be tied to the winter and the coastal lifestyle to the summer months. The gallery walls were illuminated with dim but warm lighting, cave-like and sinuous in their curving pathways through the museum. The galleries themselves were bare, but the tour group was asked to imagine displays of objects coupled with interactive digital screens, soundscapes, and films projected on the walls. Gallery 4 will introduce the theme of movement: trade routes and migration across deserts and seas, including the navigation skills and tools needed for this movement. Indeed, the physical layout of this set of galleries emphasizes movement, by structuring the walls and pathways so that Gallery 4 flows seamlessly to Gallery 5, where portrayals of life in the desert will be displayed. In the large atrium of Gallery 5, the tour guides indicated that a film depicting the desert would be projected against the bare walls of the gallery (perhaps the Beduiner film!). Between Galleries 5 and 6 is a set of stairs that takes visitors down to Gallery 6, where a re-creation of life on the coast will be displayed. Here, the tour guides indicated that this gallery would highlight al-Zubarah, a coastal settlement in the north of Qatar, and its pearling and trading artifacts from its archaeological excavations, along with a film reconstructing life in this site.Footnote46 The visitor would then progress through a low-ceilinged Gallery 7 and onward through the historical progression and transformation of Qatar before ending in the old palace with the opportunity to explore exterior gardens and fountains. Through the physical experience of moving seamlessly through the “life in Qatar” galleries, the museum emphasizes its preferred historical narrative of transitions from desert to coast depending on the seasons and the needs of the community.

Although this new national narrative is meant to promote unity, it also has the potential for controversy. Dr Balcioğlu, the 2013 project director, noted the “conflicting ideas within Qatari society about what Qatar is”, adding that “the extent to which [the museum] will satisfy every visitor remains to be seen”.Footnote47 There is mounting evidence that the museum’s focus on the duality lifestyle is raising concerns among the Qatari citizens themselves. Several Qatari academics have been vocal in their concerns regarding the re-imagination of a Qatari national identity that marginalizes those who identify as solely coastal or desert.Footnote48 Despite a national museum project member’s charitable description of the validity of this focus –– “They are not changing the narrative; they’re just not including some things”Footnote49 –– for many Qataris, the omission of the ḥaḍar and badū as separate lifestyles may be, in fact, a very significant change.

Assessing the reaction of Qatari citizens to the museum’s national narrative must wait until the official opening. Our focus is on the trove of Danish imagery, which, as we will demonstrate below, provides evidence of all three Qatari lifestyles: coastal, Bedouin, and dual. How might the new museum make use of the existing evidence so that it aligns with its narrative?

4 The Danish material and the national narrative

Our analysis highlights the problems and possibilities of connecting the material from the 1959 expedition to the unity narrative. On one hand, as we describe below, the material depicts all three lifestyles of Qatari culture, while focusing on Bedouin culture as a distinct entity, separate from coastal or city culture. Indeed, this material is an important time capsule of Bedouin heritage just before the influx of oil revenues began to change all Qatari lifestyles; as early as 1960, the Qatari government began a settlement program for the inland Bedouin tribes, encouraging them to give up their nomadic ways for a more settled existence of work in the refineries and life in concrete housing compounds.Footnote50 The Danish voiceover narration of the film also emphasizes the distinction between badū and ḥaḍar, sometimes unflatteringly; its mention, for example, that the Bedouin survived by trade with but also thievery from the coastal merchants fits uncomfortably with the unity message, to say the least.

On the other hand, our analysis acknowledges that the images alone do not contradict the unity narrative. As Stylianou-Lambert and Bounia have shown through their analysis of the same photograph used in two radically different ways in the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot war museums, photographs imply a neutrality and objectivity that obscure the flexible interpretation that accompanies the selection and display of these artifacts.Footnote51 In much the same way, any given set of photographic or film images does not challenge the claim that Qataris were always the same people, moving from desert to coast depending on the season. That is, photographic depiction per se does not prove the existence of a Bedouin culture distinct from coastal culture; it only depicts the existence of a Bedouin culture. The rest of the official story comes from historical and anthropological reports, which can accompany the images or not. The unity narrative, then, can find purchase in the inherent ambiguity of images.

In addition, the stylistic features of these photographs and film seem to cooperate with the unity narrative. Jette Bang’s style of photography strayed from an earlier approach in ethnographic photography or visual anthropology to the extent that she actively sought to humanize her subjects through photographic composition and framing. So certain aesthetic elements of the images, especially setting, camera distance, and composition, emphasize the common humanity of and universal identification with their subjects; this emphasis could be mobilized to promote a message of unity. In what follows, we outline this idea by looking closely at her images and film, describing how her particular style can work with rather than against the unity narrative.

5 Bang’s photographs and visual anthropology

To claim that Bang’s work veers from the earlier photographic approach in her field requires some familiarity with the usual style in visual anthropology. We can support this claim with some images from Hermann Burchardt’s expedition to Qatar in 1904.Footnote52 Burchardt was a wealthy explorer and photographer who fit neatly into the amateur anthropologist stereotype. As such, his work exemplifies a style of photography common to this emerging discipline in the nineteenth century.

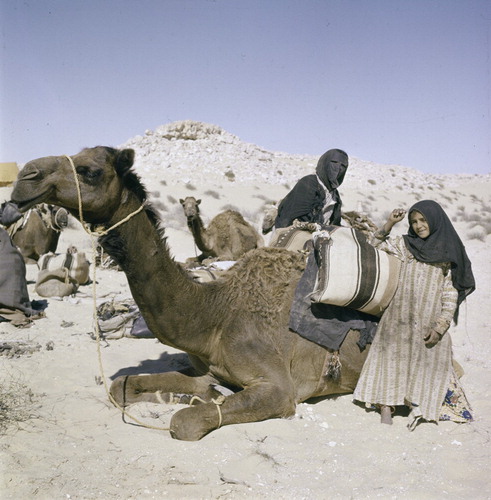

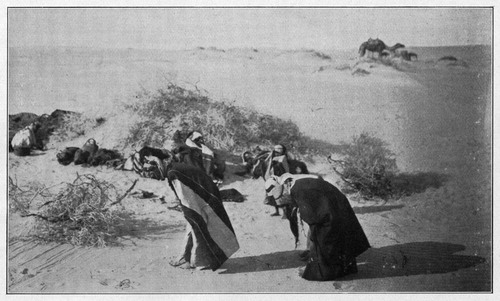

In , the humans in the middle ground primarily provide a sense of scale for the buildings in the background. This example also illustrates a common feature of this style of documentation: to locate and place native peoples in their geographical context. It was an unspoken, even ideological assumption that indigenous peoples were almost an extension of the landscape, as natural as the flora and fauna. In , for example, the Qataris bow for prayer against the desert wind, but there is no effort to understand their personal struggle, only their struggle as it exemplifies a fact of geography and religion. The subjects are elements of that landscape much like the brush, the dunes, or the camels in the background.

Figure 1: The Ottoman garrison outside Doha, Qatar, 1904.Footnote53

Figure 2: Bedouin praying, Qatar, 1904.Footnote54

The tent in or the seashore in function similarly. In this particular style of ethnographic photography, landscape is paramount, and the humans who dwell in it are not necessarily of secondary importance, but to document them means placing them in the context of this geographical location; what counts as understanding, in this tradition, is the relationship between people and place. People are part of the landscape, but in this photographic approach they are mere illustrations of its power and majesty.

Figure 3: A Bedouin tent, Qatar, 1904.Footnote55

Figure 4: Pearling boats on the Doha Corniche, Qatar, 1904.Footnote56

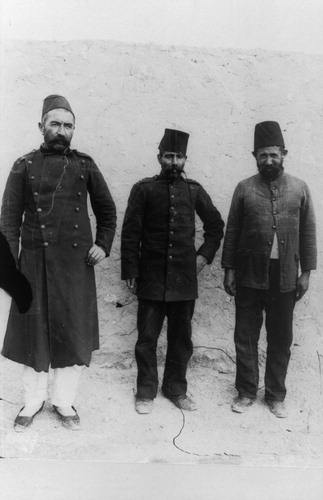

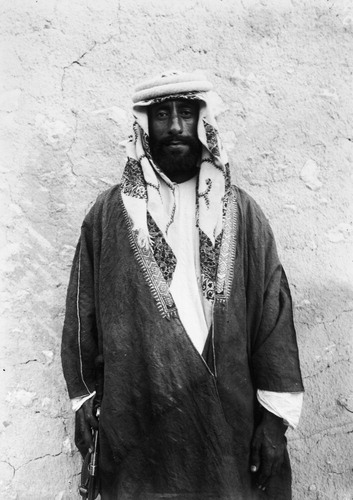

Even when we get closer to the people, the attitude toward them is quite distant and objective ( and ). These images are quite different, even opposite of what we have seen so far: the subjects are taken out of the landscape and placed against a rock wall that nevertheless speaks to the harsh conditions. What are we to understand of these men? Mostly, we are asked to recognize their typicality. “These are typical Ottoman soldiers”, the image in seems to say; the only note Burchardt took for the image in was, “genteel Arab”. None has a life or personality outside his function as a type.

Figure 5: Ottoman soldiers, Qatar, 1904.Footnote57

Figure 6: “Genteel Arab”, Qatar, 1904.Footnote58

This approach to subject and image recalls late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century anthropometric photography of races, in which the scientific potential of the encounter was contained in and expressed through the surface of the body. There was a nostalgic and not necessarily innocent impulse to classify and to capture the people and practices anthropology feared would disappear. The anthropological impulse at this time was to see people as specimens, typical of their race or geography; choices about composition (how subjects are placed or captured in the scene) and framing (especially the distance between subject and camera) expressed this impulse photographically. Generally speaking, subjects were framed at a distance and placed in a much larger landscape or against a relatively neutral setting, typical of the contemporary emphasis on scientific objectivity but also as a way of managing the potentially distracting detail and connotations of the image. That is, the goal of this kind of composition –– common for this era and discipline –– was a scientifically legible image free of emotion or narrative. Anthropology wanted what Elizabeth Edwards calls a “purified” image to focus the expert eye on the relevant evidence in the photograph.Footnote59

Yet at this very moment, from the 1880s to 1910s, anthropology was undergoing a disciplinary shift that questioned this approach and instead found scientific potential in process, kinship, and networks of culture and social bonds. The question for anthropologists after the turn of the century therefore became, how does photography fit into this new approach? If the primary bearers of anthropological knowledge are not the surface of the body or the surface of the landscape, but instead the invisible connections that shape these manifestations, how could the anthropologist capture them visually? The answer resided not in a “purified” image, but in one that depicted the messiness of everyday life; in this case, photography’s advantage was its ability to capture this “abundance”. The task for the photographer was now to manage the image so that this abundance did not become illegible detail.Footnote60 This task was much easier with photography than with motion picture cameras, especially in the field, where it was difficult to manage the cumbersome technology, much less the composition of the image.Footnote61

By the time of the Danish expedition to Qatar in the 1950s, an approach to anthropological photography that accepted and managed the scientific potential of the everyday, with images that expressed its abundance, seems to have been internalized. This approach is demonstrated by Peter Glob, the Danish archaeologist who in 1953 led Denmark’s first expedition to Bahrain to study its burial mounds. Compared to the “genteel Arab” in , the imagery under Glob’s direction () was much more informal, with emphasis on context and relationships. The photographers on this expedition were comfortable with poses, but also with idiosyncrasy and humor () and knew how to compose a shot and pick the right moment to emphasize a subject’s appeal ().Footnote62 Indeed, emotion played a much larger role. Glob was interested not just in scientific knowledge or the archaeological sites, but also the region’s culture, so for his Bahrain expedition he sought artists, anthropologists, and poets, along with experts in ancient civilizations, to help interpret the culture and his findings. For the Danish expedition team, photography was a tool not (merely) for classification, preservation, or scientific understanding, but an instrument to capture the lived experience and humanity of its subjects.

Figure 7: Pollinating the flowers of the date palm, Bahrain 1964 (Torkil Funder photo / Moesgaard Museum).

Figure 9: A tobacconist gets a turn at the pipe, Bahrain 1959 (Adam Wiehe photo / Moesgaard Museum).

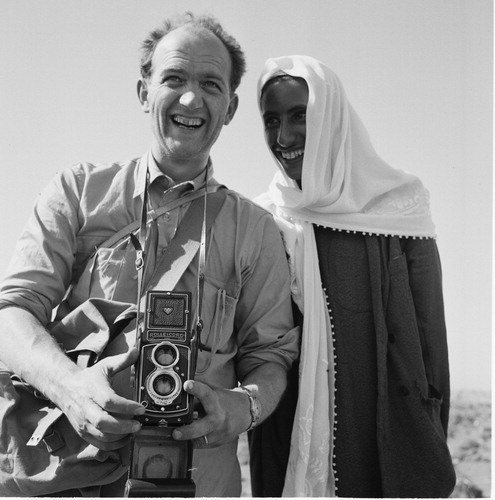

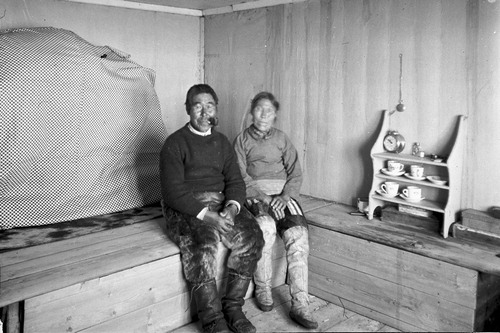

The Bahrain expedition was a success, so Glob received invitations from other Gulf nations, including Qatar. Glob led many of them, but he asked ethnographer Klaus Ferdinand () to lead the 1959 Qatar anthropological expedition. Ferdinand and Glob picked Jette Bang, a Danish photographer and filmmaker (), to document the mission. Bang had already made a name for herself with her ground-breaking photographs of Inuits in Greenland. She documented life on the island with the assiduity of an ethnographer –– over 12,000 photographs on several trips between 1936 and 1956 –– but with an artist’s eye ( and ). These images differ from what we have seen so far, even from Glob’s expedition: she preferred medium close-ups (from the chest up) with a shallow focus; neither technique was common in ethnographic trips to the Gulf in the 1900s or 1950s. Even when these techniques are not evident (), her compositions help to portray her subjects’ uniqueness rather than to frame them as specimens. is especially evocative: on one hand, the three kitchen workers are nearly identical in their uniforms and poses, emphasizing their typical setting, work, and afternoon; on the other hand, our view of the woman’s pensive expression gives perhaps just a glimpse of her inner life as the even light, the delicate range of gray and white, and the houses waiting patiently outside all depict a poignant yet slightly melancholy scene of workers separated by distance and silence, but sharing common tasks and perhaps thoughts. Bang’s aesthetic, then, seems to fit –– and even goes beyond –– Glob’s approach to documenting the region.

6 Bang’s photographs of Qatar

In Greenland, Bang adopted a participant-observer approach to ethnographic documentation. At once an outsider, yet also warmly welcomed by the Inuit community, Bang was apparently “highly skilled at relating to the people” she filmed and photographed.Footnote63 The invitation to venture to the Middle East might have come as a surprise, given her expertise on Arctic regions and peoples, but perhaps the possibility of documenting these two extremes –– hot and cold –– appealed to her as well. In any case, the trip to Qatar was an anomaly in her career geographically, but consistent in terms of her ethnographic and aesthetic approach. Indeed, despite documenting three different lifestyles in Qatar, Bang’s consistent photographic style, which uses composition, camera distance, and other techniques to humanize ethnographic subjects, we argue, may be key to integrating the images into a unified narrative of Qatari heritage.

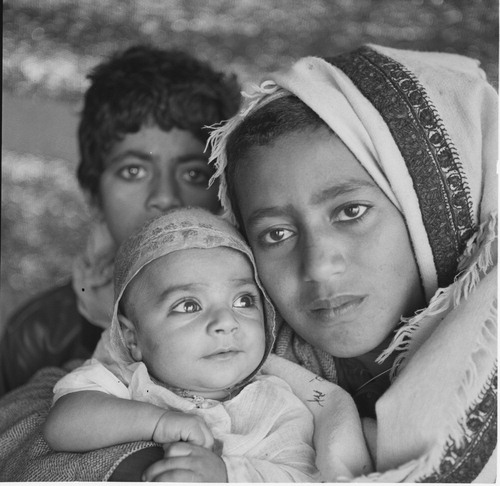

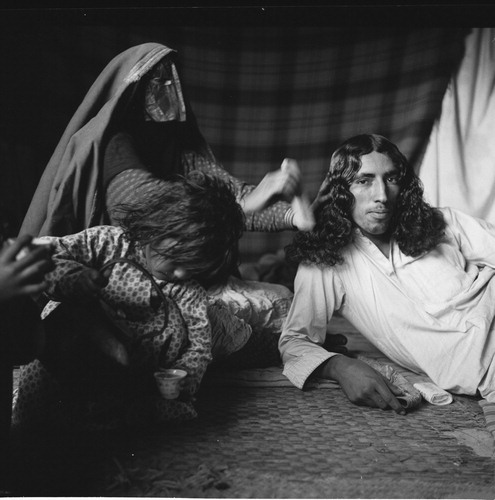

Bang’s style is evident in her portraits, as in an image of an al-Naʿīmī man listening to a recording for the first time (), a shot of an al-Naʿīmī girl (), or portraits of an Āl Murra woman () or of al-Naʿīmī children ().Footnote64 All use similar camera distances (medium shots or medium close-ups) to give a sense of intimacy, shallow focus to separate the subjects from the background (completely different than the earlier approaches that used greater depth of field to embed subjects in the landscape), and a careful selection of the moment to convey a facial expression that emphasizes the uniqueness and emotion of the subject. Even when we cannot see the face, we still get a sense of personality through pose and gesture. The specific emotions depicted, however, are all quite warm and inviting, whether they be curiosity, strength, shyness, or care. By emphasizing these positive personality traits, or by distilling the emotional register of the subject to a single, recognizable tone, Bang succeeds not only in conveying the common humanity of her subjects, but in depicting moments, experiences, and emotions with which most can easily identify or empathize. In other words, Bang’s style actively enlists techniques of identification and emotion in her documentation of the Qatari groups.

Figure 16: An al-Naʿīmī man listening to a recording for the first time, Qatar, 1959 (Jette Bang photo / Moesgaard Museum).

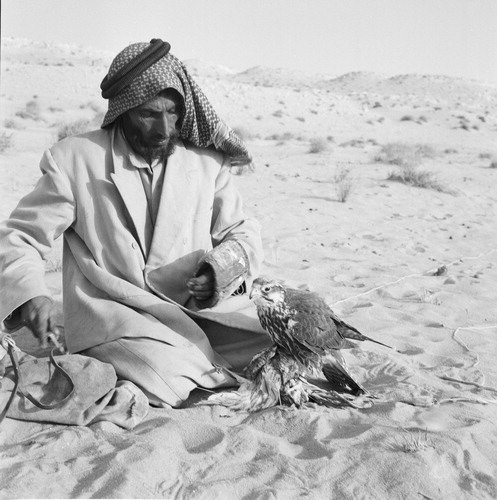

Bang’s humanizing style was consistent even when the images were not obvious portraits. Bang took many photos documenting daily life among the different tribes, such as this image of tea time with the Āl Murra in the desert (); Ferdinand is pictured on the right, serving tea, but the composition and lens choice (she uses a telephoto lens to flatten the relationship between foreground and middle ground) emphasizes the sense of community, while the poses –– such as that of the boy on the left –– lend an informality to the scene. Other images also depict moments universally recognized, as in an image of a ḥaḍar woman holding vigil over a relative in the hospital (), an image of a ḥaḍar girl receiving a blood transfusion (), or an image of an al-Naʿīmī woman grooming her husband’s hair with oil ().Footnote65 In all three cases, the moment of intimacy is heightened by the subjects’ gaze at the camera, not confrontational, but direct and unafraid. Outdoor shots depicting badū routines or traditions, such as falconry () or spinning () follow the same pattern: closer, studied composition, shallow focus, and emphasis on the people as people. A desert portrait of an Āl Murra girl () captures the fun of daily routine; the camels themselves seem to be smiling.

Figure 21: A woman visiting a relative in the Rumaylah hospital, Qatar, 1959 (Jette Bang photo / Moesgaard Museum).

Figure 22: A young girl receiving a blood transfusion, Qatar, 1959 (Jette Bang photo / Moesgaard Museum).

Figure 23: An al-Naʿīmī woman grooming her husband’s hair, Qatar, 1959 (Jette Bang photo / Moesgaard Museum).

Bang’s photographs of the diverse tribes of Qatar continue the later tradition in anthropological photography that emphasizes connection and abundance but insists on legibility and order in the image. That is, her pictures stress human connection and context –– more than, say, Burchardt’s work or anthropometric photography. Indeed, her images display an obvious lack of concern with scientific objectivity and emotional distance. Through their focus on faces, gestures, and context, Bang’s photos of the Qataris emphasize emotion, humanity, and clarity of feeling, and this emphasis has the effect of unifying and universalizing the diverse tribes, which may be useful for the new National Museum of Qatar’s agenda. However, her unifying style at least partially occluded the differences between badū, ḥaḍar, and dual lifestyles of the Qataris. Or, more precisely, while Bang and Ferdinand carefully documented the subjects of their images as either badū or ḥaḍar, the significance of the third lifestyle, especially as understood by the Qatari themselves, appears to have eluded them, as their ethnography referred to the Āl Murra (badū) and the al-Naʿīm (dual) as simply “Bedouin”. This occlusion will perhaps present a challenge for the National Museum’s agenda. The biggest challenge in this regard, however, will come from the film made during the trip.

7 The case of Beduiner

If Bang’s photographic style tends to unify and universalize the different Qatari tribes, despite markers of difference in costume and context, then the images might fit neatly –– or, at least, without too much difficulty –– into a national vision of unity and empathy. But her film, Beduiner, presents more challenges. Although its subject and even some of the individuals are familiar to anyone who has examined the photographs, the film is quite different in many respects –– necessarily so, not simply because of the different medium, but because a sixteen-minute documentary cannot hope to have the same coverage as hundreds of photographs. Indeed, Bang’s decision to focus the film on a particular topic and tribe presents the biggest obstacle to a narrative of national unity.

After setting the scene, Beduiner adopts a “day in the life” structure to tell its story. It depicts the daily routines of a Bedouin group as it arrives via camel at its location, sets up camp, enjoys the day, and settles in for the night, before breaking camp and, at the end of the film, leaving on camelback the next morning. Concentrating on this one group –– part of the Āl Murra tribe –– gives the film focus and narrative structure, but the choice has significant implications for the film’s role in a national narrative. The Āl Murra, for example, were one of the most traditional Bedouin tribes, with no hint of a dual lifestyle. Given that Ferdinand and Bang spent more time with the al-Naʿīm, the decision to edit the footage toward the Āl Murra was weighty indeed.Footnote66 Bang’s interest in or inclination toward depicting peoples free of the encroachments of modern life was already evident in Inuit (Bang, 1940), which went out of its way to show a tribe in Greenland untouched by the present, to the point of restaging shots and excluding modern elements so that a traditional lifestyle came into relief.Footnote67 The choice to focus on the Āl Murra fit with Bang’s life-long romance with “traditional” cultures. But that choice leaves the film in an awkward curatorial position: this distinctly exotic, one-sided depiction of Qatari heritage is more difficult to adapt to a narrative of dualism than the photographs, which at least offer opportunities for representation of all tribes and lifestyles.

Similarly, the choice of subject matter within the depiction of the tribe might present some difficulties with the national narrative, although these could be more easily negotiated. Ferdinand had a specialized interest in Bedouin tent-making materials and skills, so the film naturally focuses on his research program. The film depicts the ritual of building a tent –– typically women’s work, according to the narrator –– and the type of cloth, including the weave, used in making tents. It shows women spinning and weaving wool into cloth, which eventually becomes tent walls and roofs. The film is also at pains to record the material culture of Bedouin life with many shots of tools used in butter churning, coffee-making, weaving, grooming, and the like. This inventory of material culture is so detailed that a modern Qatari audience would recognize much of the film as specifically documenting the Āl Murra lifestyle rather than a more generic way of life for all Qataris. This ethnographic emphasis may be mitigated somewhat by Bang’s attempts to convey some of the emotional warmth of its subjects. A grandfather interacts with his young grandchild. A child runs smiling in the sand toward the camera. A man lovingly and proudly cares for his falcon. Moments such as these stand out among the film’s more objectively scientific concerns. There is a slight but noticeable tension between Ferdinand’s anthropological considerations and Bang’s interest in the individual humanity of her subjects.

Other images may also contradict a national narrative of unity. The film cannot help but depict the Āl Murra as foreign and exotic when compared to the modern Qatari lifestyle: their colorful clothes; their idiosyncratic Bedouin weavings; hands and feet dirty, worn, and calloused by difficult work under inhospitable conditions, including handicrafts that require all fingers and toes to join in the task; full face coverings for women, no shoes for anyone; and, needless to say, preventing lice by soaking the hair in camel urine (an odd practice that might cause many modern noses to turn). The film’s narrative is further complicated by the insertion of footage from the al-Naʿīm tribe: halfway through the “day in the life” structure, a woman churns butter in a goat skin, but her clothing and face mask mark her as al-Naʿīm, the only moment in the film that deviates from the focus on the Āl Murra. The difference is not flagged by the film in any way; the editing implies that these two shots are from the same space and time, as if the audience would not notice the difference (and the audience might not, if it were not attuned to Qatari culture). But the insertion speaks to the film’s inability or unwillingness to acknowledge differences between the tribes –– differences that the film prefers to elide for the sake of a unified theme. Its determination to depict a traditional Bedouin lifestyle for the sake of a (foreign) audience’s interest in the exotic forces it to ignore evidence that would appeal to a modern Qatari audience and allow it to fit into a grander national narrative –– exemplified, perhaps, by the omission of small details, such as the fact that the al-Naʿīm used oil, rather than camel urine, to comb out and clean their hair.Footnote68 Yet at the same time, many aspects of the Āl Murra’s Bedouin culture are recognizable and relatable: the desert setting; the ritual of coffee; majlis gatherings; bread making; prayer; falconry and camels. Many of these elements are common to the culture of the region as a whole, but some have been passed down and incorporated or accepted into Qatari culture specifically. Add Bang’s humanizing touch, and we have a group of images that could seem both familiar and strange to modern museumgoers.

The film’s depiction of the difference between the badū and ḥaḍar communities troubles a unity narrative as well. “The flat bread is baked in a pan”, says the film’s voiceover narration. “It is made of wheat flour, but the Bedouin do not raise grain; they must buy it from farmers at oases, or from the towns. Much of what they use they must buy, or trade for. Kettles, jugs, pots, and cups. Although the Bedouin live in the desert, they cannot exist without the town’s craftsmen and merchants. In the old days, the Bedouin obtained what they needed by trading and theft”. This observation is clearly inconsistent with the unity message; it describes the communities as historically separate, distinct, and even at odds with each other. While we hear these words, the film shifts from images of Bedouin tools in the desert to images of the town, to indicate at once the town’s historical separation from the desert and Bedouin culture, but also now their symbiosis. If theft was the legacy of the old days, today “the standard of living is much higher”, even for nomads, now that foreign companies pay local tribes –– via Qatar’s sheikh –– for the oil they extract. The implicit message: oil brings the two lifestyles together and eliminates the need for competition or difference.

Finally, the most remarkable difference between the film and the photographs is simply one of style: compared to the photographs, the film almost seems as if it were made by a different team entirely. The motion picture camera was secondary to Bang’s still camera, resulting in a certain technical awkwardness to the film: many shots are out of focus; the exposure is uneven; the editing is sometimes clumsy; the framing often suggests a cinematographer caught by surprise at the way the scene develops. These faults, however, are common to expedition or anthropological films, which are usually made under the most extreme conditions. The “we were here” imperative of an expedition forces an improvisational approach to filming.Footnote69 Indeed, the extra care required of normal live-action documentary filming is usually incommensurate with an expeditionary team’s context and other duties, so footage often bears the marks of a more, say, casual approach. Additionally, unlike Bang’s photographs, which are carefully composed and created to depict a single moment and emotion, the film tries to depict temporal processes and events and routines, which is at least partly why film was considered a valuable addition to the expedition. Edwards argues that anthropological photographs minimize information, while film multiplies it, and that this dichotomy corresponds to changing representational strategies and philosophies in ethnographic anthropology.Footnote70 It applies as well to the difference between Bang’s still and moving images; that is, we can explain the striking stylistic difference between the film and the photographs by understanding the differences between the two in terms of their disciplinary missions. Photography is designed to exclude and clarify; film is designed to include and complicate –– at least at the level of the depiction of events. By focusing only on one tribe, however, the filmmakers decided not to include and complicate the representation of Qatari lifestyles, at least in that regard.

Because of the difference between the film and the photographs, Beduiner as it stands might be more difficult to fit in the museum’s narrative of national unity. It presents some unique curatorial challenges. How might it be used? The sensitive and perhaps confusing discussion about distinct badū and ḥaḍar cultures –– not to mention the obvious Danishness of the film –– could be attenuated by simply stripping the film of its soundtrack and screening it silently. Such attenuation could be selective by leaving untouched the audio accompaniments to the coffee ritual and the recitation of the Koran. Stripping the film of the Danish narration would also allow the film to be screened without subtitles, thereby avoiding overt reference to uncomfortable topics such as theft and the creative uses of camel urine. Another possibility: using the film as stock footage for a selection of clips, each looped so that the focus is entirely on a particular tool, skill set, or ritual. This strategy would leave the structure of the film –– as a day in the life of the Āl Murra –– behind, but would have the advantage of modularity: several interchangeable parts circulating as needed on the museum walls. It would also solve the problem of the al-Naʿīm insert by allowing this clip to be shown separately. A final possibility involves a selective re-editing of the film in its entirety, leaving out scenes that complicate the unity narrative. Using this technique, the museum could remove the images of the city and its inhabitants, thereby eliminating the visual distinction between the ḥaḍar and the badū and focusing exclusively on life in the desert. Scenes that promote a sense of “otherness” may also find a home on the national museum’s cutting-room floor, such as weaving with one’s toes.

In summary, while there is no doubt that the Beduiner film is a historically significant artifact, it remains to be seen whether the new national museum will incorporate it in its entirety or selectively use it to bolster its unity narrative. We would bet our riyals and dirhams on the latter.

8 Conclusion

As our analysis demonstrates, the 1959 Danish expedition unearthed evidence of the heterogeneity (and even borderlessness) of the peoples of Qatar. And in fact, this heterogeneity was showcased and even celebrated in the original national museum of Qatar, as Al-Mulla notes.Footnote71 While there exists historical and anecdotal evidence that some Qatari families, including the ruling Āl Thanī family itself, migrated between the desert in the winter and the coast in the summer, living the “duality life”,Footnote72 the bulk of visual evidence collected by the Danish expedition supports the existence of three cultural lifestyles in Qatar: the ḥaḍar, the badū, and the dual. We have investigated here how the new national museum of Qatar might repurpose these artifacts to serve a new national narrative of unity.

We suggested here that these very same artifacts –– at least those by Jette Bang –– are at pains to emphasize, perhaps uniquely, the common humanity of the Qataris she encountered, rather than their otherness. The photographs, especially, highlight positive personality traits and recognizable emotions. They strive to depict the individuality of their subjects, not their typicality. This approach helps to break down barriers: the subjects are not (or not only) members of a tribe or class of people, but persons who feel, act, work, and play much like everyone else. Chauvinism is based on group identification, while empathy comes from individual understanding. So the national museum can take advantage of this opening, glimpsed through Bang’s aesthetic strategy, to mobilize the images in favor of a unity narrative. If the “nation” is an imagined community, Bang’s images demonstrate how recognition of our common humanity can be another, perhaps stronger foundation.

Our analysis is speculative –– the museum has not yet unveiled its specific plans for these images –– but our argument also concerns the sometimes uneasy relationship between aesthetic approach and scientific objectives. The Beduiner film highlights a contradiction between these two representational strategies: an aesthetic strategy that attempts to individualize, and a scientific strategy that attempts to group, classify, and generalize. Ferdinand and Bang were not at odds; the available material and reports indicate that they worked well together and shared interests and goals. Nevertheless, the film bears traces of different emphases or goals. Moreover, the film functions differently than the photographs by showing daily routines in time, which often emphasize the action, rather than the emotion. There are moments of emotion and identification, as we have indicated, but the film does not use the usual techniques (e.g., shot-reverse shot or reaction shots) to emphasize these emotions. Instead, objects and actions are the subject of the film, whereas people and emotions are the subject of the photographs. At the very least, then, Bang’s materials point to the contrasting functions and perhaps unavoidable differences between photography and film in ethnographic practice.

Our argument also concerns the importance of nation-building narratives for all countries, even those that are assumed to run on oil wealth without much need for other state-society lubricants. In Qatar, the richest and smallest rentier state in the world, why does the narrative of the national museum matter? Our work catalogues, albeit briefly, the social and political tensions in Qatari society that are entrenched through adherence to identity narratives of division, not similarity. The propagation of a national narrative of unity, under these circumstances, is an understandable political strategy. The significant investment of time, money, and efforts in the renovation of the new national museum, despite falling revenues and budget shortfalls, indicates that the political leadership of Qatar feels its social and political goals will be better realized through a shift in national narrative. And our analysis illustrates that narrative taking shape in the construction of the new national museum, both in terms of physical structure and content messages.

Yet recent events have made a unifying narrative all the more politically relevant –– and may have provided an opening for a state-led re-interpretation of this narrative that is more historically accurate. In June 2017, several of Qatar’s immediate neighbors (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates), coupled with Egypt, implemented a land, air, and sea blockade of the country, precipitating a diplomatic crisis with deep roots of animosity and competition between the states.Footnote73 In the months since, Qatar surprised much of the world –– and perhaps even itself –– with its resilience. Most importantly for our purposes, public nationalism –– in both displays and discourse –– is on the rise.Footnote74 The political leadership of Qatar has a groundswell of support from both citizens and expatriate residents, and the government has begun to use the crisis to its advantage, pushing through several domestic policy initiatives that had been previously stalled by conservative forces, both internal and external.Footnote75 We return to the first public appearance of the Emir after the beginning of the diplomatic crisis: the construction site of the new national museum of Qatar. Qataris themselves have begun to identify as one: post-blockade interviews with citizens have expressed increased patriotism and feelings of Qatari identity, including previously marginalized groups such as the minority Shīʿa sect.Footnote76 As one Qatari citizen declared, “It has been amazing seeing diverse communities from all over the country coming together. I dare say this has made a patriot out of me”.Footnote77

We can see signs that the leadership of Qatar is taking full advantage of the moment of nationalism to re-imagine the narrative of national unity. Most strikingly, the Emir of Qatar explicitly praised “my Qatari people, along with the multinational and multicultural residents in Qatar” in his speech to the UN General Assembly in September 2017.Footnote78 The Emir’s quotation has been replicated on billboards, public art exhibits, and local newspapers and websites. Likewise, the Emir’s sister and the Chairperson of Qatar Museums, H.E. Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, has used her arts and culture podium to state, “Dialogue and diversity have always been a key component of Qatar’s identity”.Footnote79 Further, she has directly connected the mission of the new National Museum to the modern diversity of Qatar, stating, “The museum is the physical manifestation of Qatar’s proud identity, connecting the country’s history with its diverse and cosmopolitan present”.Footnote80

Echoing the rhetoric from the upper echelons of government leadership, the state of Qatar’s Government Communication Office unrolled a new public messaging campaign, entitled, “Unity in Diversity”, in November and December 2017.Footnote81 The aim of this community campaign was to “convey a message of unity and togetherness” –– not only between Qataris but also “between Qataris and non-Qataris and to make everyone living in Qatar feel like this is home”. The title of the campaign, unity in diversity, is striking, because it acknowledges, in ways that the national museum’s previous emphasis on the duality lifestyle did not, that differences exist within the Qatari population. However, these differences can be superseded by the similarities. This rhetoric may signal a shift in the political narrative from an emphasis on a certain Qatari lifestyle of the past to one of national unity that encompasses all groups and communities in Qatar despite subgroup differences. If this shift in narrative does continue, the national museum may benefit, as the existing historical artifacts become less inconvenient to the nation-building narrative.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jocelyn Sage Mitchell

Jocelyn Sage Mitchell is Assistant Professor in Residence in the Program in Liberal Arts, Northwestern University in Qatar, Education City, Doha, Qatar.

Scott Curtis

Scott Curtis is Associate Professor in Residence in the Program in Communication, Northwestern University in Qatar, and Associate Professor in the Department of Radio/Television/Film at Northwestern University, 1920 Campus Drive, Evanston, Illinois, 60208, USA, [email protected].

Notes

1 Anderson, Imagined Communities (2006); Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (2006); Hobsbawm and Ranger, The Invention of Tradition (1983).

2 Levitt, Artifacts and Allegiances: How Museums Put the Nation and the World on Display (2015).

3 Erskine-Loftus (ed.), Reimagining Museums: Practice in the Arabian Peninsula (2013); Erskine-Loftus (ed.), Museums and the Material World: Collecting the Arabian Peninsula (2014); Erskine-Loftus, Hightower, and Al-Mulla (eds), Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives and Identity in the Arab Gulf States (2016); Exell, Modernity and the Museum in the Arabian Peninsula (2016); Exell and Wakefield (eds), Museums in Arabia: Transnational Practices and Regional Processes (2016).

4 See, for example, Prager, “Displaying Origins: Heritage Museums, Cultural Festivals, and National Imageries in the UAE”, HHSS 1.1 (2015), pp. 22–46; and Wakefield, “Falconry as Heritage in the United Arab Emirates”, World Archaeology 44.2 (2012), pp. 280–90.

5 Erskine-Loftus, Museums and the Material World (2014), pp. 12–73; Exell, “Lost in Translation? Private Collections in Qatar”, Museums and the Material World: Collecting the Arabian Peninsula, ed. Erskine-Loftus (2014), pp. 258–94.

6 Zahlan, The Creation of Qatar (1979), p. 28.

7 ICJ, “Case Concerning Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions Between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar v. Bahrain): Counter-Memorial Submitted by the State of Bahrain (Merits)”, 31 Dec. 1997, p. 13.

8 Exell and Rico, “‘There Is No Heritage in Qatar’: Orientalism, Colonialism and Other Problematic Histories”, World Archaeology 45.4 (2013), pp. 670–85. Also see: Derderian, “Authenticating an Emirati Art World: Claims of Tabula Rasa and Cultural Appropriation in the UAE”, JAS 7.S1 (2017), pp. 12–27.

9 Commins, The Gulf States: A Modern History (2012).

10 Kapel, Atlas of the Stone-Age Cultures of Qatar (1967); Bibby, “Qatar”, Looking for Dilmun (1970), pp. 117–44.

11 De Cardi, “The British Archaeological Expedition to Qatar, 1973–1974”, Antiquity 48 (1974), pp. 196–200; De Cardi (ed.), Qatar Archaeological Report: Excavations 1973 (1978); Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar (1995); Al-Mulla, “Collecting the Collection: Changing Qataris’ Attitudes and Practices”, Museums and the Material World (2014), pp. 92–115; Al-Mulla, “The Development of the First Qatar National Museum”, Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula (2014), pp. 117–25.

12 Tixier, French Archaeological Mission to Qatar: 1st Campaign (1977).

13 See: University of Copenhagen, “Qatar Islamic Archaeology and Heritage Project”. Originally planned to be a ten-year collaboration, the project was cancelled in 2015 due to issues over payment. See: Zieler, “UCPH Agrees to a Settlement: The Final Bill for the Qatar Scandal is DKK 9 Million”, University Post, 22 Nov. 2016.

14 Interview with Alan Walmsley (Director, al-Zubarah), Qatar, 12 Mar. 2013. For a regional overview of the tense relationship between archaeology and development, see: Al-Belushi, “Archaeology and Development in the GCC States”, JAS 5.1 (2015), pp. 37–66.

15 Bang, Beduiner (1962); Ferdinand, Bedouins of Qatar (1993); Nielsen (ed.), The Danish Expedition to Qatar, 1959: Photos by Jette Bang and Klaus Ferdinand (2009).

16 Højlund, Glob and the Garden of Eden: The Danish Expeditions to the Arabian Gulf (1999).

17 Toumi, “Qatar National Museum to Reopen in 2012”, Gulf News, 12 Nov. 2009.

18 Abdalsalam, “Wārda al-injāzāt tatafattuḥ fī matḥaf Qaṭar al-waṭanīy” [The Rose of Achievements Is Blooming at the Qatar National Museum], Al-sharq, 8 Jan. 2014.

19 Khatri, “Qatar’s National Museum Eyeing 2016 Opening”, Doha News, 6 July 2014.

20 Khatri, “Qatar’s Emir Makes First Public Appearance Since Start of Gulf Dispute”, Doha News, 20 June 2017.

21 Anon., “National Museum Symbolises Qatar’s Rich Heritage, Culture”, Gulf Times, 5 Nov. 2018.

22 A member of the construction team at the new national museum site inferred that the ambitious desert rose design and architectural vision of Jean Nouvel, the architect of the museum, may have had something to do with missing the original construction deadline of the end of 2011 (and each subsequent deadline thereafter): “Jean Nouvel is the inventor of the headache” [Anonymous interview with the authors, 14 Aug. 2017, Doha, Qatar].

23 Pogrebin, “A Progress Report on the National Museum of Qatar”, New York Times, 17 Mar. 2016.

24 Rosman-Stollman, “Qatar: Liberalization as Foreign Policy”, Political Liberalization in the Persian Gulf (2009), p. 188.

25 Roberts, Qatar: Securing the Global Ambitions of a City-State (2017), pp. 52–3, 136.

26 Davidson, After the Sheikhs: The Coming Collapse of the Gulf Monarchies (2012); Kamrava, Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (2013); Kamrava, “State-Business Relations and Clientelism in Qatar”, JAS 7.1 (2017), pp. 1–27.

27 Kovessy, “Spending Slashed as Qatar Prepares to Run QR46.5 Billion Deficit”, Doha News, 17 Dec. 2015.

28 Khatri, “Qatar’s Emir Makes First Public Appearance Since Start of Gulf Dispute”, Doha News, 20 June 2017.

29 Robles Gil, Religious Pluralism in the Gulf: Paradoxes of Coexistence in a Modernizing State, MA thesis (2018).

30 Alshawi and Gardner, “Tribalism, Identity and Citizenship in Contemporary Qatar”, AOTME 8.2 (2013), pp. 46–59, here 55–6. Also see: Nagy, “Making Room for Migrants, Making Sense of Difference: Spatial and Ideological Expressions of Social Diversity in Urban Qatar”, Urban Studies 43.1 (2006), pp. 119–37.

31 Rizzo, “Rapid Urban Development and National Master Planning in Arab Gulf Countries: Qatar as a Case Study”, Cities 39 (2014), pp. 50–7, here 52.

32 Althani, Jassim the Leader: Founder of Qatar (2012), pp. 46–50; cooke, Tribal Modern: Branding New Nations in the Arab Gulf (2014), pp. 30–1; Wright, The Old Amiri Palace: Doha, Qatar (1975), 19–20; Bin Marzouq, “Al-ḥāla al-thaqāfīya fī Qaṭar” [The Cultural Situation in Qatar], Al-shaʿb yurīd al-iṣlāḥ fī Qaṭar … ayḍa [The People Want Reform in Qatar … Too] (2012), pp. 261–63. For the Kuwaiti parallel, also see: Longva, “Nationalism in Pre-Modern Guise: The Discourse on Hadhar and Badu in Kuwait”, IJOMES 38.2 (2006), pp. 171–87.

33 Bibby, “Qatar”, Looking for Dilmun (1970), pp. 125–6.

34 Bibby’s misunderstanding, which lumped together the Bedouin lifestyle of the Āl Murra with the dualistic lifestyle of the al-Naʿīm, was not an anomaly. The careful ethnographic notes and images of Ferdinand and Bang in their Qatari expeditions depict clear lifestyle differences between the Āl Murra and the al-Naʿīm, including in dress, activities, and wealth. Yet, as we will describe later on, the Danish ethnographers did not translate these observations into a deeper understanding of the cultural distinction between the two tribes, instead referring to them both under the overall moniker of “Bedouin” [See: Ferdinand, Bedouins of Qatar (1993); and Nielsen (ed.), The Danish Expedition to Qatar, 1959 (2009)].

35 Wright, The Old Amiri Palace (1975), pp. 19–20. Also see: Mitchell, “We’re All Qataris Here: The Nation-Building Narrative of the National Museum of Qatar”, Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives, and Identity in the Arab Gulf States, ed. Erskine-Loftus, Hightower, and Al-Mulla (2016), p. 63.

36 See, for example, Al-Ghanim, “Al-taḥaḍḍur wa al-taḥawwulāt fī al-tarkīb al-ṭabaqī: dirāsa ḥāla al-mujtamaʿ al-Qaṭarī” [Urbanization and Changes in Class Structure: A Case Study of Qatari Society], MSc thesis (1986); Al-Jaber, Al-taṭawwur al-iqtiṣādīy wa al-ijtimāʿīy fī Qaṭar: 1930–1973 [Economic and Social Development in Qatar: 1930–1973], PhD diss. (2002); Bin Marzouq, “Al-ḥāla al-thaqāfīya fī Qaṭar” [The Cultural Situation in Qatar] (2012), pp. 261–263; Al-Mulla, Museums in Qatar: Creating Narratives of History, Economics and Cultural Cooperation, PhD diss. (2013), p. 88.

37 See: Assami, Al-Darwish, and Al-Saadi, Bader (2012); Al-Maria, The Girl Who Fell to Earth (2012); Nagy, “Making Room for Migrants, Making Sense of Difference” (2006).

38 Shockley and Gengler, “Marriage Market Preferences: A Conjoint Survey Experiment in the Arab Gulf” (2017); Nagy, “Making Room for Migrants, Making Sense of Difference” (2006).

39 Al-Kuwari, “Muqaddima” [Introduction], Al-Shaʿb yurīd al-iṣlāḥ fī Qaṭar … ayḍa [The People Want Reform in Qatar … Too] (2012), p. 15; Partrick, “Nationalism in the Gulf States”, Kuwait Programme on Development (2009), p. 21. Despite Article 34 of the Constitution of Qatar (2004), which states that “citizens shall be equal in terms of public rights and duties”, the reality is that Qataris are differentiated into two legal categories of citizenship –– original (“nationals”) and naturalized. These legal categories of citizenship have ramifications for the level of political and civil rights given to each group, including the right to participate in elections or be appointed to the legislative body (Article 16). See Law No. 38 of 2005 on the Acquisition of Qatari Nationality, 30 Oct. 2005.

40 Mitchell, Beyond Allocation: The Politics of Legitimacy in Qatar, PhD diss. (2013), p. 197.

41 Interview with Balcioğlu (Project Director, Qatar National Museum), Qatar, 23 Apr. 2013.

42 Mitchell, “We’re All Qataris Here” (2016), p. 66.

43 Ibid.

44 cooke, Tribal Modern (2014), p. 11.

45 The two authors accessed the new national museum through a Qatar Museums’ tour on 14 Aug. 2017.

46 There was some disagreement among our interlocutors as to whether the museum will include Bedouin tents as part of the al-Zubarah display. Certainly, the al-Naʿīm of Qatar is the dual lifestyle tribe most affiliated with this site, as their residence in and use of the land in this area from the 1870s onward is documented both by Lorimer, Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman, and Central Arabia 2: Geographical and Descriptive Materials (1904) and by the posted descriptions of al-Zubarah’s history in the al-Zubarah Fort Visitor’s Center in Qatar (as recorded during the authors’ visit on 9 December 2017). The symbolic duality of desert and sea is prominently displayed at al-Zubarah, as a traditional Bedouin tent has been erected adjacent to the 1938 fort, and camels graze nearby for tourist pictures, but it remains to be seen how the duality lifestyle will be displayed in the new museum’s Gallery 6.

47 Interview with Balcioğlu, 23 Apr. 2013.

48 See, for example, Al-Janahi, National Identity Formation in Modern Qatar: New Perspective, MA thesis (2014); Al-Hammadi, “Presentation of Qatari Identity at National Museum of Qatar: Between Imagination and Reality”, JOCAMS 16.1 (2018), pp. 1–10.

49 Mitchell, Beyond Allocation, PhD diss. (2013), p. 198.

50 Ferdinand, Bedouins of Qatar (1993), pp. 13, 47; Al-Maria, The Girl Who Fell to Earth (2012), pp. 127–28.

51 Stylianou-Lambert and Bounia, “War Museums and Photography”, MAS 10.3 (2012), pp. 183–96, here 190.

52 Nippa and Herbstreuth (eds), Along the Gulf: From Basra to Muscat; Photographs by Hermann Burchardt (2006).

53 Photo by Hermann Burchardt. © bpk-Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Hermann Burchardt.

54 Photo by Hermann Burchardt. © bpk-Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Hermann Burchardt.

55 Photo by Hermann Burchardt. © bpk-Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Hermann Burchardt.

56 Photo by Hermann Burchardt. © bpk-Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Hermann Burchardt.

57 Photo by Hermann Burchardt. © bpk-Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Hermann Burchardt.

58 Photo by Hermann Burchardt. © bpk-Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Hermann Burchardt.

59 Edwards, “Uncertain Knowledge: Photography and the Turn-of-the-Century Anthropological Document”, Documenting the World: Film, Photography, and the Scientific Record (2016), pp. 89–123.

60 Ibid.

61 Griffiths, Wondrous Difference: Cinema, Anthropology, and Turn-of-the-Century Visual Culture (2002).

62 Højlund (ed.), Glob and the Garden of Eden: The Danish Expeditions to the Arabian Gulf (1999).

63 Jørgensen, “A Gentle Gaze on the Colony: Jette Bang’s Documentary Filming in Greenland, 1938–39”, Films on Ice: Cinemas of the Arctic, ed. MacKenzie and Stenport (2015), p. 239.

64 All photographs in this section are from Nielsen (ed.), The Danish Expedition to Qatar, 1959 (2009).

65 It is beyond the scope of our argument (and our expertise) to go into detail regarding the differences in face masks and clothing that allow identification of ḥaḍar, badū, and dual lifestyles in these images. We suggest consulting Al-Mulla, Costume and Textile in Qatar: Identity and Presentation (2016) for further information.

66 Ferdinand and Bang spent January and March 1959 traveling with the al-Naʿīm and February 1959 traveling with the Āl Murra [Nielsen (ed.), The Danish Expedition to Qatar, 1959 (2009), p. 136].

67 Jørgensen, “A Gentle Gaze on the Colony” (2015), p. 237.

68 Nielsen (ed.), The Danish Expedition to Qatar, 1959 (2009), p. 67.

69 Griffiths, “Camping Among the Indians: Visual Education and the Sponsored Expedition Film at the American Museum of Natural History”, Recreating First Contact: Expeditions, Anthropology, and Popular Culture, ed. Bell, Brown, and Gordon (2013).

70 Edwards, “Uncertain Knowledge” (2016).

71 Al-Mulla, Museums in Qatar (2013), pp. 77–8.

72 Mitchell, “We’re All Qataris Here” (2016), pp. 62–3.

73 Roberts, Qatar: Securing the Global Ambitions of a City-State (2017); Ulrichsen, Qatar and the Arab Spring (2014); Ulrichsen, “What’s Going on with Qatar?”, Washington Post, 1 June 2017; Sly, “Princely Feuds in the Persian Gulf Thwart Trump’s Efforts to Resolve the Qatar Dispute”, Washington Post, 13 May 2018.

74 Khatri, “Outpouring of Support for Sheikh Tamim Now on Display at MIA Park”, Doha News, 21 Aug. 2017; Walsh, “Wealthy Qatar Weathers Siege, but Personal and Political Costs Grow”, New York Times, 2 July 2017.

75 Mitchell, “The Domestic Policy Opportunities of an International Blockade”, The Gulf Crisis: The View from Qatar, ed. Miller (2018).

76 Robles Gil, Religious Pluralism in the Gulf (2018).

77 Anon. email to Mitchell, 11 July 2017.

78 Al Thani, “Speech to the United Nations General Assembly”, The Peninsula, 19 Sept. 2017.

79 Al Thani, “Islamic Art: Past, Present, and Future”, Opening address, Seventh Biennial Hamad bin Khalifa Symposium on Islamic Art, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, 2 Nov. 2017.

80 Khatri, “Qatar’s Emir Makes First Public Appearance Since Start of Gulf Dispute”, Doha News, 20 June 2017.

81 Al-Thani email to Mitchell, 23 Aug. 2017.

Bibliography

- 1 Primary sources

- 1.1 Photographic collections and films:

- Assami, Maaria; Latifa Al-Darwish; and Sara Al-Saadi, directors, Bader, 2012, available online at www.baderfilm.com.

- Bang, Jette, director, Inuit, 1940, available online at https://filmcentralen.dk/grundskolen/film/inuit.

- Bang, Jette, director, Beduiner, 1962, available online at https://filmcentralen.dk/grundskolen/film/beduiner.

- Bang, Jette, Photographic Collection, Danish Arctic Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Bang, Jette and Klaus Ferdinand, Photographic Collection, Moesgård Museum, Århus, Denmark.

- Burchardt, Hermann, Photographic Collection, bpk-Bildagentur, Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany.

- Glob, Peter, Photographic Collection, Moesgaard Museum, Århus, Denmark.

- 1.2 Correspondence and interviews:

- Al-Thani, Sara Nasser, email to Jocelyn Sage Mitchell, 23 August 2017.

- Anon., email to Jocelyn Sage Mitchell, 11 July 2017.

- Anon (construction worker at Qatar National Museum), interview, Doha, Qatar, 14 August 2017.

- Balcioğlu, Emin Mahir (Project Director, Qatar National Museum), interview, Doha, Qatar, 23 April 2013.

- Walmsley, Alan (Director, al-Zubarah), interview, al-Zubarah, Qatar, 12 March 2013.

- 1.3 Speeches:

- Al Thani, H.E. Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa, “Islamic Art: Past, Present, and Future”, Opening address, Seventh Biennial Hamad bin Khalifa Symposium on Islamic Art, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, 2 November 2017, available online at www.youtube.com/watch?v=N70945pPJvk.

- Al Thani, H.H. the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad, “Speech to the United Nations General Assembly”, The Peninsula, 19 September 2017, available online at www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/19/09/2017/In-Full-Text-The-speech-of-Qatar-Emir-at-the-opening-session-of-UN-General-Assembly.

- 1.4 Laws:

- International Court of Justice (ICJ), “Case Concerning Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions Between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar v. Bahrain): Counter-Memorial Submitted by the State of Bahrain (Merits)”, 31 December 1997, available online at www.icj-cij.org/files/case-related/87/11051.pdf.

- Qatari Government, Law No. 38 of 2005 on the Acquisition of Qatari Nationality, 30 October 2005, Al-Meezan (Qatari Legal Portal) www.almeezan.qa/LawPage.aspx?id=2591&language=en.

- 2 Secondary sources

- Abdalsalam, Ahmed, “Wārda al-injāzāt tatafattuḥ fī matḥaf Qaṭar al-waṭanīy” [The Rose of Achievements Is Blooming at the Qatar National Museum], Al-sharq, 8 January 2014, available online at www.al-sharq.com/news/details/195058.

- Al-Belushi, Mohammed Ali K., “Archaeology and Development in the GCC States”, Journal of Arabian Studies 5.1 (2015), pp. 37–66. doi: 10.1080/21534764.2015.1057398

- Al Ghanim, Kaltham Ali, “Al-taḥaḍḍur wa al-taḥawwulāt fī al-tarkīb al-ṭabaqī: dirāsa ḥāla al-mujtamaʿ al-Qaṭarī” [Urbanization and Changes in Class Structure: A Case Study of Qatari Society], MSc thesis (Ain Shams University, Cairo, 1986).

- Al-Hammadi, Mariam Ibrahim, “Presentation of Qatari Identity at National Museum of Qatar: Between Imagination and Reality”, Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 16.1 (2018), pp. 1–10. doi: 10.5334/jcms.171

- Al-Jaber, Moza Sultan, Al-taṭawwur al-iqtiṣādīy wa al-ijtimāʿīy fī Qaṭar: 1930–1973 [Economic and Social Development in Qatar: 1930–1973], PhD dissertation (Qatar University, 2002).

- Al-Janahi, Buthaina Mohammed, National Identity Formation in Modern Qatar: New Perspective, MA thesis (Qatar University, 2014).

- Al-Kuwari, Ali Khalifa, “Muqaddima” [Introduction], Al-shaʿb yurīd al-iṣlāḥ fī Qaṭar … ayḍa [The People Want Reform in Qatar … Too], edited by Ali Khalifa Al-Kuwari (Beirut: Al-Maaref Forum, 2012), pp. 13–33.

- Al-Maria, Sophia, The Girl Who Fell to Earth (New York: Harper, 2012).

- Al-Mulla, Mariam Ibrahim, Museums in Qatar: Creating Narratives of History, Economics and Cultural Cooperation , PhD dissertation (University of Leeds, 2013).

- Al-Mulla, Mariam Ibrahim, “Collecting the Collection: Changing Qataris’ Attitudes and Practices”, Museums and the Material World: Collecting the Arabian Peninsula, edited by Pamela Erskine-Loftus (Boston: MuseumsEtc., 2014), pp. 92–115.

- Al-Mulla, Mariam Ibrahim, “The Development of the First Qatar National Museum”, Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula: Debates, Discourses and Practices, edited by Karen Exell and Trinidad Rico (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 117–125.

- Al-Mulla, Mariam Ibrahim, Costume and Textile in Qatar: Identity and Presentation (Saarbrücken, Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2016).

- Alshawi, A. Hadi and Andrew Gardner, “Tribalism, Identity and Citizenship in Contemporary Qatar”, Anthropology of the Middle East 8.2 (2013), pp. 46–59. doi: 10.3167/ame.2013.080204

- Althani, Mohamed A., Jassim the Leader: Founder of Qatar (London: Profile Books, 2012).

- Anderson, Benedict, Imagined Communities, rev. ed. (New York: Verso, 2006).

- Anon., “National Museum Symbolises Qatar’s Rich Heritage, Culture”, Gulf Times, 5 November 2018, available online at www.gulf-times.com/story/611911/National-Museum-of-Qatar-to-open-on-March-28-2019.

- Bibby, Geoffrey, “Qatar”, Looking for Dilmun (New York: Knopf, 1970), pp. 117–44.

- Bin Marzouq, Marzouq Bashir, “Al-ḥāla al-thaqāfīya fī Qaṭar” [The Cultural Situation in Qatar], Al-shaʿb yurīd al-iṣlāḥ fī Qaṭar … ayḍa [The People Want Reform in Qatar … Too], edited by Ali Khalifa Al-Kuwari (Beirut: Al-Maaref Forum, 2012), pp. 258–67.

- cooke, miriam, Tribal Modern: Branding New Nations in the Arab Gulf (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

- De Cardi, Beatrice, “The British Archaeological Expedition to Qatar, 1973–1974”, Antiquity 48 (1974), pp. 196–200. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00057896

- De Cardi, Beatrice (ed.), Qatar Archaeological Report: Excavations 1973 (Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Qatar National Museum, 1978).

- Commins, David, The Gulf States: A Modern History (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2012).

- Crystal, Jill, Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar, revised edn (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- Davidson, Christopher M., After the Sheikhs: The Coming Collapse of the Gulf Monarchies (London: Hurst, 2012).

- Derderian, Elizabeth, “Authenticating an Emirati Art World: Claims of Tabula Rasa and Cultural Appropriation in the UAE”, Journal of Arabian Studies 7.S1 (2017), pp. 12–27. doi: 10.1080/21534764.2017.1352161

- Edwards, Elizabeth, “Uncertain Knowledge: Photography and the Turn-of-the-Century Anthropological Document”, Documenting the World: Film, Photography, and the Scientific Record, edited by Gregg Mitman and Kelley Wilder (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), pp. 89–123.

- Erskine-Loftus, Pamela (ed.), Reimagining Museums: Practice in the Arabian Peninsula (Boston: MuseumsEtc., 2013).

- Erskine-Loftus, Pamela, (ed.), Museums and the Material World: Collecting the Arabian Peninsula (Boston: MuseumsEtc., 2014).

- Erskine-Loftus, Pamela, “Introduction: Ultra-Modern Traditional Collecting”, Museums and the Material World: Collecting the Arabian Peninsula, edited by Pamela Erskine-Loftus (Boston: MuseumsEtc., 2014), pp. 12–73.

- Erskine-Loftus, Pamela; Victoria Penziner Hightower; and Mariam Ibrahim Al-Mulla (eds), Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives and Identity in the Arab Gulf States (London: Routledge, 2016).

- Exell, Karen, “Lost in Translation? Private Collections in Qatar”, Museums and the Material World: Collecting the Arabian Peninsula, edited by Pamela Erskine-Loftus (Boston: MuseumsEtc., 2014), pp. 258–94.

- Exell, Karen, Modernity and the Museum in the Arabian Peninsula (New York: Routledge, 2016).

- Exell, Karen and Trinidad Rico, “‘There Is No Heritage in Qatar’: Orientalism, Colonialism and Other Problematic Histories”, World Archaeology 45.4 (2013), pp. 670–85. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2013.852069

- Exell, Karen and Sarina Wakefield (eds), Museums in Arabia: Transnational Practices and Regional Processes (London: Routledge, 2016).

- Ferdinand, Klaus, Bedouins of Qatar (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993).

- Gellner, Ernest, Nations and Nationalism, 2nd edn (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006).