Abstract

This article examines key questions of citizen-state, citizen-citizen, and citizen-expatriate relations in the Arab Gulf states through the lens of the 2017 Qatar blockade. It utilizes original public opinion survey data that allow examination of the embargo’s short-term impacts on social and political relations in Qatar as well as broader trends observed over the period from 2010 to 2019. Results lend support to some existing qualitative accounts suggesting changes in important social and political dynamics in Qatar after the blockade. However, survey data also show that such post-blockade differences are mostly reflections of larger attitudinal shifts witnessed over the course of the past decade, rather than isolated effects of the GCC crisis. This suggests the possibility that other Gulf Arab states are experiencing similar transformations in popular sociopolitical orientations and behavior brought on by the same long-term drivers.

1 Introduction

The June 2017 blockade of Qatar represents a major turning point in the international relations of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and of the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The years-long feud between Qatar and neighboring Arab countries prompted lasting shifts in trade and migration patterns, caused the effective demise of the GCC as a vehicle for regional economic, political, and security cooperation, and continues to serve as a significant geostrategic backdrop to other regional contests for power within and among MENA states and their great power patrons. Amid such far-reaching consequences, the impact of the embargo on social and political relations inside Qatar has received understandably less attention from scholars and policymakers.

Yet a key element of the 2017 crisis was the failed attempt by blockading countries to sow social and political discord within Qatar itself, as a means of exerting pressure on the country’s leadership. It is thus instructive to consider the reasons for Qatar’s notable resilience to such efforts at destabilization, separate from its ability to bear the economic costs of the embargo. More generally, the profound shock of the Qatar blockade and its aftermath offers a unique window into longer-term challenges that apply in degrees to all the Gulf Arab states. These include integration of massive expatriate populations, state-driven reform of the rentier economy away from dependence upon natural resources, accommodation of popular interest in greater political participation, and the fashioning of coherent and inclusive nations from citizenries still marked by significant descent-based distinctions along tribal, confessional, and other lines.

The present study examines these key questions of citizen-state, citizen-citizen, and citizen-expatriate relations in the Gulf through the lens of post-blockade Qatar. The momentous and unforeseen nature of the embargo renders the case a rare laboratory in which to study social and political changes spurred by the events of June 2017. Has the Qatar crisis forged a stronger bond between citizens and between citizens and non-citizens, or instead sharpened the boundaries distinguishing Qataris from foreigners and from one another? Has it hastened Qatar’s push toward a more diversified and entrepreneurial economy, or else reinforced the existing patronage-based rentier model? Has it inspired greater interest in political participation among citizens called upon to support their country against outside aggression, or has it led them to prioritize security and stability over democracy? Finally, to what extent do such effects and processes observed since the blockade help explain the country’s largely unforeseen resilience in the face of the embargo? The answers to these questions afford instructive lessons about the durabilities and also vulnerabilities of GCC states as they endeavor to overcome common systemic challenges in the coming years and decades.

The analysis to follow is informed by the results of original public opinion surveys of citizens and residents of Qatar carried out before and after June 2017 by the Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI) at Qatar University. The data allow examination into the blockade’s short-term impacts on social and political relations as well as longer-term trends observed during the period from 2010 to 2019. The survey results lend support to some existing qualitative accounts suggesting changes in important social and political dynamics in Qatar after the blockade, such as increased inter-group trust between Qataris and non-Qataris and greater citizen interest in political participation and state responsiveness. However, the data also show that such post-blockade differences are mostly reflections of larger attitudinal shifts witnessed over the course of the previous decade, rather than isolated effects of the GCC crisis. This suggests the possibility that other Arab Gulf states are experiencing comparable transformations in popular sociopolitical orientations and behavior brought about by similar underlying processes.

2 Studying the domestic side of the Qatar blockade

The June 2017 embargo of Qatar is still recent and continues to unwind, and so the relative lack of academic studies on its domestic social and political impacts, which may take time to manifest, is perhaps to be expected.Footnote1 It is also foremost a matter of international affairs, with wide-ranging implications for global trade and security that can overshadow its internal consequences for any one party to the dispute. However, assessing the effects of the blockade on societal dynamics in Qatar is instructive for at least two reasons, one specific and another more general.

First, a central but largely forgotten aspect of the GCC crisis itself was the initial, unsuccessful effort by blockading countries –– the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia in particular –– to undermine popular support for the ruling Al Thani family in order to force the country’s capitulation to their demands. The antagonists sought to create social and political conflict inside Qatar by portraying the ruler, Amir Shaikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, as friendly to Arab Gulf archrival Iran, by sponsoring a token Qatari opposition in exile, by agitating the state’s tribal support base, and by championing several contenders to the Qatari throne from marginalized branches of the ruling family. Of course, these efforts failed. Rather than turning against their own government, ordinary Qataris rallied around the leadership and took to social media and other forums to denounce and ridicule the overt attempts at external manipulation. Understanding how and why public opinion remained supportive carries important lessons about state legitimacy, political participation, and nation-building in Qatar and the other autocratic Arab Gulf states.Footnote2

More broadly, studying how Qatari society responded to the traumatic economic, social, and political shocks brought on by the blockade offers valuable insight into larger processes of development, contestation, and transformation taking place across the Arab Gulf region and to some extent the wider Middle East. The June 2017 crisis saw in Qatar an unprecedented coming together of citizens and foreign residents in support of their common home, despite longstanding Qatari misgivings over the size and sociocultural impacts of the non-national population. It likewise helped to flatten enduring descent-based distinctions among Qatari citizens themselves, creating shared symbols and spaces of civic activism, loyalty, and resistance that cut across traditional family and tribal lines.Footnote3 The blockade also opened a window of opportunity for sanctioned political participation, with citizens encouraged or at least not discouraged by the state from voicing opinions and engaging in behavior that might previously have been considered out of place.Footnote4 Finally, the contingency of the embargo put on effective hold intended reforms to the rentier political economic system that would have seen citizens assume greater responsibility for their financial welfare, including via once-unthinkable taxes and cuts to subsidies that have supported Qataris and other Gulf nationals for generations.

Yet to what extent are these manifestations actual products of the blockade versus reflections of longer-term attitudinal and behavioral change that the 2017 crisis merely brought to the fore? Did the blockade make Qataris more accepting and appreciative of the role of non-Qataris in society, for example, or simply present an occasion to highlight the more positive attitudes toward expatriates that, over some period, had emerged among citizens? If the answer is the former, then the case of post-blockade Qatar may contain relatively few lessons for other GCC states and speak instead to a more universal question about societal resilience in the face of an existential challenge. If the answer is closer to the latter –– if the blockade did not cause but instead spotlighted attitudinal and behavioral change among Qataris –– then it is possible or even likely that at least some other Gulf countries are witnessing similar transformations in state-society relations that have remained latent. To untangle these immediate and longer-term impacts of the Qatar embargo is a primary aim of this paper.

As will be demonstrated in subsequent sections, the past ten years have seen substantial changes in the way that Qataris and non-Qataris view one another, and in the way that citizens perceive their relationship with the state and their role in the polity. Some of these trends, particularly in the political sphere, have been interrupted by dramatic exogenous events, including both the blockade and the Arab uprisings begun in 2011. But the general directions of change are clear.

In the social domain, citizens have gradually become more accepting of Qatar’s majority non-citizen population, particularly white-collar expats from Arab and Western nations. However, qualitative gaps persist in Qatari tolerance and social trust of fellow nationals as compared to Arab and especially Western and South Asian expats. In the political arena, citizen interest in political participation has increased since 2010 overall, yet public enthusiasm for democratic governance has fluctuated in key moments –– first dampened by the Arab Spring and then buoyed by the blockade. Meanwhile, Qataris’ deference to state decision-making has declined consistently since 2011, signaling an ever-greater willingness to oppose unpopular policies. Finally, the decade from 2010 to 2019 has seen the Qatari citizenry grow considerably wealthier, with the largest increases coinciding once again with the Arab Spring and the 2017 GCC crisis. This evidences a continued state reliance upon economic distribution as a means of relieving or preempting political pressure, at the expense of planned structural economic reform.

3 Social relations and group trust after the blockade

The dichotomy between citizens and non-citizens has been an enduring aspect of life in the Arab Gulf states since before independence.Footnote5 Lacking the workforce and technical expertise to administer the post-pearling oil economy, and later the post-oil knowledge economy, Qatar and other Gulf societies have relied upon plentiful foreign labor to fill positions in the education, health, petroleum, services, transportation, and other industries. Many non-citizens transition imperceptibly into and out of the local population, remaining just long enough to fulfill a contract or meet a financial goal. But others have made the Gulf a long-term home, living there decades or even their entire lives.Footnote6 Today, foreigners comprise just over half (an estimated 52%) of all GCC residents, with individual country ratios ranging from a low of 38% in Saudi Arabia to 87% in Qatar and the UAE.Footnote7

The presence of such large and diverse non-indigenous populations has naturally rendered citizenship a primary social category distinguishing “locals” from “foreigners,” as well as a fundamental legal category demarcating the rights and responsibilities of subjects contra those of non-subjects. Typically, social relations between Gulf citizens and non-citizens are conceptualized separately from the legal regime governing the status of foreigners –– that is, the notorious kafala system of labor sponsorship, which restricts the entry, stay, and exit of foreigners while denying them a path to citizenship.Footnote8 Yet these dynamics are but two sides of one theoretical coin: the same considerations and worries that motivate Gulf states’ use of the kafala also underlie the structural social tensions between ordinary citizens and non-citizens. Gulf governments and Gulf nationals share concern that foreign workers may dissipate the financial resources available for state patronage of citizens as part of the so-called “rentier bargain” of economic distribution in return for political loyalty.Footnote9 Both also fear that foreigners may introduce outside norms and beliefs that change the character of traditional culture and values. Finally, Gulf rulers and citizens think about the security implications of expatriate populations that physically outnumber locals and also may transmit political ideas and conflicts from their home countries.

The case of Qatar illustrates well these drivers of apprehension. Upon becoming a British protectorate in 1916, Qatar possessed the Gulf region’s smallest and arguably most isolated population. Indeed, a sticking point in treaty negotiations between the British and Qatar’s ruler Shaikh Abdulla bin Jassim Al Thani was the former’s demand that its subjects be permitted residence in the country, with Shaikh Abdulla arguing strenuously that “the Qatari people were not prepared to accept foreigners”.Footnote10 By the time of its first census in 1970, however, Qatar’s approximately 45,000 citizens were already a minority alongside more than 65,000 foreign residents.Footnote11 This demographic imbalance would thereafter increase exponentially until reaching its present state of around 350,000 Qataris compared to 2.4 million non-Qataris.Footnote12 Nearly two-thirds of the current expatriate population consists of South Asian nationals, who are employed mainly as unskilled labor in the construction sector, while white-collar professionals from Arab and to a lesser extent Western countries comprise most of the remainder.Footnote13

The academic literature on anti-immigrant attitudes disagrees about the root causes of the rejection of outsiders. Theory holds that bias stems from fears over the economic threat posed by migrants, whereas empirical evidence, including from experimental work, suggests instead that identity factors are more influential than material factors in shaping citizens’ views.Footnote14 Without seeking to arbitrate between the two explanations, it is enough to say that both mechanisms appear operable in Qatar. The influence of English language and foreign norms of behavior –– particularly Western dress and the sale of alcohol –– have been flashpoints for social activism, with citizen criticism sometimes sparking dramatic changes in policy.Footnote15 Yet foreigners represent for Qataris not only a sociocultural “other”, but also direct economic competition. Nine out of ten employed citizens work in the public sector,Footnote16 and skilled migrants aspire to the same high-wage positions in ministries and semi-governmental entities that most citizens occupy. Despite programs intended to give priority to citizen applicants, the generally higher productivity and lower reservation wages of expats makes them comparatively attractive employees, and perceptions of discrimination and unfairness in hiring have been commonplace among citizens.Footnote17

A less prevalent concern in Qatar has been the effect of foreigners on security and stability. The potential for Arab expats in particular to spread political ideologies and quarrels to Gulf citizenries has been a worry of governments since the rise of Arab nationalism and later pan-Islamic movements, and helped motivate the transition to cheaper and less politically contentious Asian labor during the 1970s oil boom.Footnote18 Following the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, both Saudi Arabia and Kuwait resorted to mass expulsion of Arab residents –– Yemenis and Palestinians, respectively –– for their (or their countries’) perceived support of Iraq. The Arab Spring protests of 2011 renewed the specter of political contagion spreading to the Gulf from elsewhere in the Arab world via migrant populations, but those fears were not borne out. Finally, supposedly less politicized non-Arab residents of Gulf states also have not been immune from security concerns, including about their capacity for economic sabotage via strike action and their transporting of inter-state rivalries such as that between India and Pakistan.Footnote19

The events of June 2017 have been credited in media narratives,Footnote20 and some scholarly analyses,Footnote21 for improving relations between citizens and non-citizens in Qatar. While these accounts are largely descriptive rather than explanatory, one can identify at least two separate avenues by which the embargo might have had such an effect. First, the sudden and serious threat posed by the blockading countries –– militarily and later economically –– was felt equally by all residents of Qatar and overshadowed less immediate concerns. In the initial days of the crisis, Qataris and non-Qataris alike worried for their and their families’ physical safety, for the security of their homes and economic assets, and for the immediate and long-term future if they were unable to remain in the country due to war or instability. Under such circumstances, the intangible challenges posed by cultural difference, social inequality, and communal segregation doubtless lost much of their salience. Similarly, in June 2017 the personal threat posed by economic competition between citizens and foreigners paled in comparison to the prospect of wholesale financial collapse or external expropriation of wealth resulting from the blockade.

A second manner in which the crisis may have contributed to improved citizen-expat relations in Qatar is by offering a platform for shared civic activity in support of the embattled country. Such activism took place online through social media as well as in the real world. Non-Qataris joined citizens in outward signals of support for the state and for the person of the Amir, decorating their vehicles and residences with patriotic symbols, adding their signatures and well wishes to neighborhood billboards, and participating in campaigns to purchase local products.Footnote22 That they stayed and fought alongside Qataris against the blockade contradicted the notion of expatriates as fair-weather opportunists, committed to Qatar only so long as they could easily extract economic gain.Footnote23 Their efforts would be famously and unexpectedly acknowledged by Amir Shaikh Tamim in his first post-blockade address to the United Nations General Assembly, where he expressed pride “in my people and [in Qatar’s] residents”.Footnote24 Masses of citizens and expatriates assembled at the airport to greet the Qatari leader upon his return to Doha.Footnote25 More recent occasions, such as Qatar’s surprise winning of the 2019 AFC Asian Cup football championship over Saudi Arabia and the hosting United Arab Emirates, saw a repeat of public celebrations that conspicuously involved both citizens and non-citizens.Footnote26

These and other factors give good reason to believe qualitative impressions that Qataris and non-Qataris have emerged from the blockade enjoying a closer social bond and greater mutual appreciation. However, the results of public opinion surveys offer, if not a contrary picture, then a more complicated one. Qataris do indeed appear to be more accepting of foreigners after the blockade, but this change extends back many more years to at least 2011, when the available data begin. Depicted in is self-reported social trust among Qatari citizens for three different categories of residents –– those from Arab, South Asian, and Western countries, respectively –– in addition to fellow citizens.Footnote27

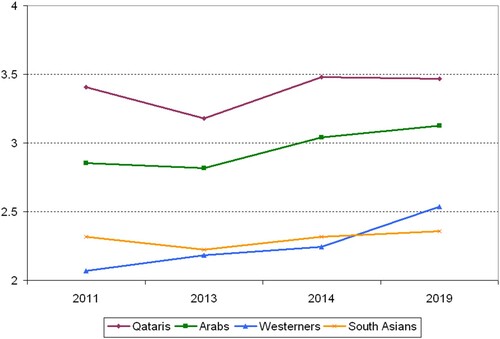

The survey data indicate, in the first place, a wide and persistent gap in attitudes toward fellow citizens on the one hand, and all types of expatriates, including other Arab nationals, on the other. On a scale from 1 to 4, where 1 signifies no trust and 4 means a lot of trust, the average level of Qatari social trust for other citizens between 2011 and 2019 is approximately 3.4. Mean trust in Arab expatriates, by contrast, is 3.0, while that for residents from South Asian and Western countries is lower still at about 2.3 –– or below the midpoint of the scale. Even in 2019, then, Qatari trust in Western and especially South Asian expatriates is around a third lower than trust in other citizens, and in substantive terms falls nearer to distrustful than trustful.

Figure 1: Qatari trust in different social groups, 2011‒19.Footnote28

Nevertheless, the data do evidence a positive change in attitudes toward two expatriate groups in particular, namely Arab and Western residents. From 2011 to 2019, reported Qatari trust in Western expats increased by 23% and trust in Arab residents by 10%. The corresponding gaps in trust for fellow citizens versus these groups also narrowed by 38% and 30%, respectively. Meanwhile, trust in other Qataris and in residents from South Asian countries did not change statistically over the past decade. The post-blockade period thus saw a continuation of a trend of greater citizen trust in white-collar expatriates from Arab and Western backgrounds, but this positive change did not extend to predominantly Asian blue-collar workers, and it is not an isolated effect of the 2017 crisis. These patterns suggest that Qatari acceptance of foreigners is a long-term process based on extended inter-group contact,Footnote29 and one that other Gulf countries with similar demographies and social dynamics may also be witnessing.Footnote30

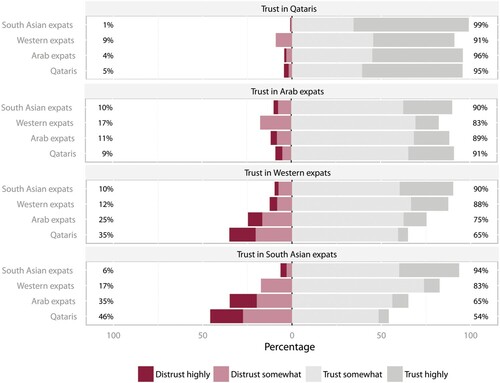

Another way of examining post-blockade inter-group relations is to study the full matrix of trust between Qatar’s citizen and non-citizen groupings. The preceding analysis considered changes in Qatari trust for expat groups, but what of residents’ trust in Qataris and in each other? summarizes trust for all permutations of social categories as reported in 2019. The most obvious and notable result is that whereas all groups report relatively high levels of trust in Qatari and Arab expatriates, this trust is not reciprocated for Western and South Asian expatriates. For instance, 91% of Western expatriates say that they trust Qatari citizens somewhat or highly, compared to just 65% of Qataris who say the same of Westerners. Even more dramatically, a full 99% of surveyed South Asian residents report trusting Qataris, but only 54% of Qataris trust residents from South Asian countries. This discrepancy also is true, albeit to a lesser extent, among Arab expats in Qatar, who report lower levels of trust in Western and especially South Asian residents as compared to these groups’ stated trust in Arab expats. Although overall trust levels remain high, then, substantial group-based differences remain even two years after the blockade.

4 Political orientations after the blockade

As with other domains, the 2017 GCC crisis has been cited as a turning point in citizen orientations toward politics. Once the option of full-scale military takeover of Qatar was negated, the embargoing countries turned their attention to a project of stoking political dissent among Qataris. The campaign proceeded both directly, by questioning the legitimacy of the Amir and organizing an opposition-in-exile, and indirectly, by seeking to undercut the state’s ability to patronize citizens financially. Rather than turning against the leadership, however, ordinary citizens rallied in defense of the political status quo, non-democratic though it may be, engaging in online and real-world activism to an extent probably unseen in post-independence Qatar.Footnote31 The question remains whether the blockade itself precipitated a change in political orientations among citizens, or instead supplied a previously unavailable outlet for preexisting interest in political participation.

One can hypothesize two different mechanisms by which the blockade might have served to bolster popular political interest. First, the experience of making a tangible positive contribution to the country’s security and development is a relatively rare one in the context of an ultra-rentier welfare state such as Qatar, where it is generally the state that is expected to protect and take care of citizens rather than vice versa. Qataris’ novel and encouraging experience with popular political engagement after June 2017 may have instilled a newfound sense of role and purpose in the polity that manifested in a greater interest in politics generally and/or interest in personal involvement in political life.

Moreover, in the wake of the Arab Spring, Qatari and other Gulf citizens most often associate political activism with the real prospect of instability and violent conflict, having witnessed the disastrous outcomes of would-be revolutions across the region since 2011. In Gulf states, popular concerns over security and stability have been linked empirically to greater political deference to government decision-making, with more citizens content to remain on the political sidelines when perceptions of internal and external threats are high.Footnote32 Qataris’ role in bolstering rather than undermining national security through their post-blockade political action may have taught a different, more positive lesson that altered these threat calculations, lowering the perceived risk of engaging politically and thus encouraging individuals toward greater participation.Footnote33

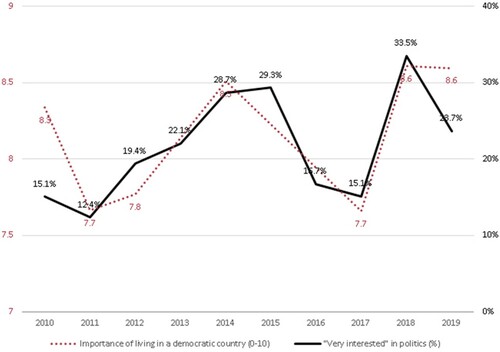

Data from public opinion surveys conducted in Qatar between 2010 and 2019 give substance to claims of increased citizen interest in politics and political involvement after 2017. Yet they also show a more general upward trend that would appear to be as closely connected to regional as to domestic political developments. illustrates change over the previous decade in two key attitudes: overall interest in politics and the importance attached to “living in a country that is governed democratically”. As is plain from the figure, these two orientations have moved in remarkable parallel since their initial measurement in 2010. Also clear from is that key external events, including but not limited to the blockade, have strongly shaped Qatari orientations toward politics and toward democracy, producing an uneven increase dampened by momentous events.

Democratic orientations were first impacted by the Arab uprisings in 2011, causing citizens to deprioritize political participation and democracy in the name of stability and boosting confidence in Qatari state institutions.Footnote34 Over the next four years, political and democratic interest gradually recovered before plummeting again between 2015 and 2016. The year marked Saudi Arabia’s escalatory entry into the Yemeni civil war in March 2015, behind newly-empowered Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saʿud. June 2015 saw a deadly bombing of a Shiʿa mosque in Kuwait by the Islamic State terrorist organization, which was near the height of its power and threatened to extend operations throughout the Gulf countries. In September, Russia began its own intervention in Syria’s civil war that would decisively turn the tide in favor of the government. As one Qatari contact said of the drop in citizen political interest, “The Arab Spring had blown up”.Footnote35

Then, in December 2015, GCC finance ministers announced an historical agreement in principle to implement a once-unthinkable 5% value-added tax to shore up Gulf state finances following a 2014 collapse in oil prices. In a closely followed address to the Shura Council, Qatar’s Amir surprised citizens when he warned starkly that the state could no longer afford “to provide for everything”.Footnote36 In the ensuing weeks, the country followed other Gulf states in removing expensive fuel and utilities subsidies and also abruptly terminated a citizen health insurance scheme introduced just months before.Footnote37 Both geopolitically and economically, uncertainty prevailed.

It is thus notable that the shock of the blockade had the opposite impact on Qatari orientations toward politics. Between 2017 and 2018, the percentage of citizens who reported being very interested in politics more than doubled, from only 15% in May 2017 to 34% at the same time next year. Interest in democracy mirrored this jump.Footnote38 That the GCC crisis lifted rather than depressed popular interest in political participation, contrary to other exogenous events, points to external threat perceptions as a key driver of fluctuations in Qatari political orientations. Whereas neighboring violence and regional economic downturn increased the perceived risk of political action, the embargo presented the reverse risk: that Qataris would remain inactive in the face of external aggression and open the door to instability by appearing opposed or indifferent to the political status quo.

Besides helping to clarify the conditions that allowed Qatari political activism to flourish after June 2017, the survey findings arguably carry an important lesson also for other GCC states. It is likely that there, as in Qatar, many citizens possess a latent interest in politics and in more democratic governance that is intermittently tempered or tamped down by striking outside events that raise the predicted risk or lower the expected payoff of citizen mobilization at the individual level. Dissatisfaction with the existing state of affairs can be a powerful motivator, but the decade from 2010‒19 in the MENA region has supplied few examples of popular action leading to improved circumstances –– and no shortage of worst-case scenarios. Under such conditions, the provision of security and stability becomes itself a primary source of political legitimacy for the state, a fact that Gulf governments certainly are aware of and continue to use to their advantage.Footnote39

5 Reviving the rentier state: economic distribution after the blockade

Qatar is the world’s foremost rentier state. Its small citizenry and enormous natural gas resources give it unrivaled capacity for financial distribution, even when compared to its wealthy Gulf Arab neighbors. In 2018, revenues from oil and gas exports equaled more than $175,000 per citizen.Footnote40 The state allocates a generous portion of this income to Qataris via an extensive system of welfare benefits, including a near-guaranteed position in the public sector, a land allotment, low-interest home construction loan, free education and health services, and other subsidies and allowances.Footnote41 In line with the expectations of rentier state theory, Qatar features extremely low levels of political contestation. The country’s only elected deliberative body is the advisory Central Municipal Council, whose members give suggestions on local affairs to the Ministry of Municipality and Environment. An appointed Shura Council also serves a mainly advisory function, although it enjoys some influence over domestic policy via its nominal control of the general budget.Footnote42

Despite Qatar’s affluence, and corresponding political stability, it is still vulnerable to outside economic forces. Its ability to generate government revenue depends on natural resources that are depletable and must be sold on volatile international markets. When global energy prices fall below the fiscal break-even point for Qatar and other GCC states, they can no longer pay for the expensive welfare systems that support citizens as well as the larger rentier political-economic model. Downturns in oil markets thus create both financial and political difficulties for Gulf governments.

Enter the oil crash that began in summer 2014. Oil prices would hit their lowest point in a decade at around $27 per barrel, down from an average of $100 over the prior three years. The International Monetary Fund projected a $1 trillion shortfall in GCC budgets under a scenario of low oil prices and no structural reform of the rentier economy, whose balance sheets had ballooned with massive social spending meant to counteract the Arab Spring uprisings.Footnote43 By 2016, Qatar faced its first deficit in fifteen years, and had joined the rest of the GCC in announcing and swiftly implementing radical policy changes to reduce the budget shortfall.Footnote44 Measures included an overnight end to fuel subsidies, an increase to water and electricity prices, and a new GCC-wide 5% value-added tax (VAT) on goods and services that challenged a fundamental tenet of the authoritarian rentier bargain: the reverse principle of no taxation, so no representation.Footnote45 Finally, Gulf rulers advised citizens that, unlike during previous downturns, such rentier retrenchment did not signify a temporary austerity but rather the new normal.Footnote46

Until now, analysis of the role of economics in insulating Qatar from the effects of the 2017 blockade has focused on the state’s proactive commercial and monetary policies.Footnote47 Qatar promptly found new trading partners to replace the blockading countries, incubated the rise of indigenous industries to supplement imports in some sectors, and drew from an estimated $335 billion sovereign wealth fund to provide liquidity to banks and forestall a run on the Qatari currency instigated by the embargoing countries.Footnote48 However, beyond what Qatar did do economically in the wake of the crisis, also critical is what it did not do: namely, it deferred implementation of the key fiscal reform measures decided after the 2014 oil crash, including most importantly the 5% VAT. One expects that Qatar’s decision aimed in part to distance itself politically from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, who were the main architects of the GCC reform agenda and duly went forward with austerity plans notwithstanding the Qatar dispute. The decision also likely reflected a different sort of political calculation, that saving Qataris from unwelcome economic changes would provide a boost to public opinion at a time when the state needed popular support.

The upshot is that rather than suffering financially from the embargo, in fact the average Qatari household saw its economic situation improve after June 2017. Apart from the pre-blockade increase in fuel prices, no new major austerity measures were imposed. Meanwhile, the uncertainty of the crisis likely motivated many citizens to join the labor market, including previously non-working Qatari females, as protection against inflation or lost business or investment income. Finally, it is possible that the state’s repatriation of at least $20 billion in sovereign wealth fund assets –– equivalent to 12% of Qatar’s total 2017 GDP –– had the effect of a monetary stimulus,Footnote49 injecting cash into the economy that eventually found its way to citizens through existing channels of rentier patronage.

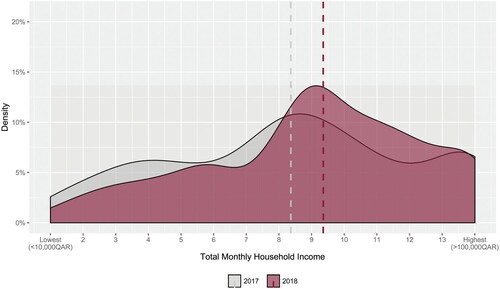

This result is illustrated in , which depicts the distribution of total household income among Qataris as measured in May 2017 and May 2018, respectively. The survey data show a marked shift from lower income categories to higher income categories over this twelve-month span. In 2017, 62% of citizens reported total household income of more than 40,000 Qatari riyals (∼$11,000) per month. By 2019, this proportion had risen to 76%, representing a 23% relative increase. Other SESRI survey data collected over the same period show a similar jump in household income. Notably, there was no other change in reported Qatari income either between May 2014 and May 2017 or again between May 2018 and May 2019. This suggests that it is the blockade, rather than a more general upward trend, that accounts for the increase.

That average citizen income did not increase in the three years prior to the blockade means that the last significant growth in Qatari wealth most probably took place after September 2011, when the government surprised citizens with a 60% pay increase for public sector employees, doubled to 120% for those working in the police and military.Footnote50 The move was widely interpreted as an attempt to preempt citizen discontent at the height of the Arab Spring. It would be better described as a reward for Qataris’ conspicuous lack of enthusiasm from the outset of the revolts. Whatever the characterization, the fact remains that the regional political earthquakes of 2011 and 2017 have undoubtedly coincided with a deepening of the rentier state in Qatar. In each case, citizens have emerged more affluent but also more dependent upon government largesse, while the latter has refrained from implementing planned structural reforms designed to ensure the long-term sustainability of the resource-based economy and polity. For now, citizens and leaders appear content to preserve Qatar’s winning formula.

6 Conclusion: societal change in Qatar and the wider GCC

How has the blockade of Qatar altered relations within society and between society and the state? This question has been less frequently investigated compared to the numerous international dimensions of the GCC conflict, but it is no less significant –– both for what it teaches about Qatar specifically and its potential lessons for the other Arab Gulf states. This study has leveraged rare nationally representative survey data collected in Qatar before and after the June 2017 crisis to offer some empirically-backed answers. The analysis supported some common anecdotal impressions about changes in domestic social and political relations due to the embargo, but it has qualified or contradicted others.

The findings demonstrated, first, that the embargo did not give rise to a new era of mutual social trust and acceptance between the distinct social groupings in Qatar, as supposed in some qualitative accounts. Rather, the post-blockade period saw continued incremental improvement in social relations that began at the beginning of the decade or earlier. Moreover, such improvement has not extended to all groups of people. Qatari trust in fellow citizens, for instance, has not increased overall during the period from 2010–19, although it remains much higher than trust in any expatriate group. Neither have there been improvements during this time in the perceptions of Qataris and non-Qatari Arabs toward blue-collar workers from the Indian subcontinent. The most significant increase in trust witnessed over the ten years considered here is that of Qataris and other Arabs toward expatriates from Western countries, which in 2011 was substantially lower than trust in any other group measured in the survey. This situation remained until the last pre-blockade data point in 2014, with Qatari trust in Westerners surpassing trust in South Asian residents only by 2019. Nonetheless, in relative terms Qatari and Arab views of non-Arab expats –– Asian and Western –– continue to lag considerably behind.

A largely analogous result obtained when survey data were used to investigate the idea that the blockade caused an unprecedented spike in Qatari interest in politics and in popular involvement in politics. Analysis of changes in political interest over 2010–19 suggests an underlying upward trend, yet one that is highly sensitive to, and has repeatedly been suppressed by, worry over potential instability and threat following momentous external shocks. Here the 2017 crisis is unique in having had the reverse effect on Qatari orientations, bolstering rather than depressing citizen interest in politics and in democratic governance. This paper argued that the reason Qatari citizens embraced post-blockade political activism is precisely because they viewed it as a stabilizing force in the face of outside aggression. In other words, the blockade taught Qataris the opposite lesson from the Arab Spring and other recent examples, that popular political mobilization need not necessarily beget chaos and can in fact play a very positive role in preserving the polity.

Finally, the data revealed a previously underappreciated economic impact of the Qatar embargo: the reinvigoration of the rentier state. Whereas Qatar had joined other GCC countries in promising fundamental changes to the traditional welfare model in light of the 2014 collapse in oil prices, the contingency of the blockade led to a deferral of the majority of the unpopular austerity measures, including most notably the introduction of general taxation. This had the effect not simply of insulating citizens from economic damage due to the crisis, but actually improving the financial situation of the average Qatari household. The state’s practical suspension of the rentier reform agenda, combined with its repatriation of tens of billions of riyals in foreign-invested assets, acted as a net wealth transfer to the citizen population. This is reflected in the survey data, which indicates a spike in reported household income around the time of the blockade not seen since the government’s 60% Qatari pay raise enacted in 2011 after the onset of the Arab Spring.

That many of the social and political effects commonly attributed to the Qatar blockade are in reality reflections of longer-term developments in the country on display since at least the start of the 2010s, is in one sense perhaps an anticlimactic conclusion. Yet in another respect, the result is a more exciting one, as it means that the changes observed in Qatar are not one-off products of an exogenous crisis but may be generalizable to other Arab Gulf states. Relations between Qataris and non-Qataris did not improve after June 2017 because the country was under imminent external threat, but because, over some lengthy period of time, trust between (certain) social groupings had already begun to turn more positive. Likewise, Qataris did not become more interested in politics and democracy after the blockade; rather, the dynamics of the crisis –– in which citizen activism played an important role in securing the country –– alleviated citizens’ overriding concern that organized expressions of popular political interest might devolve into the sort of violent disorder seen across the Middle East and North Africa since 2011.

The results discussed in this study thus take on a wider significance for the Gulf region as a whole, where comparable efforts to manage social integration, political participation and accommodation, rentier retrenchment, and nation-building are ongoing. Substantively, the findings from Qatar highlight some regional success stories, including the gradual if slow progression toward citizen acceptance of white-collar expatriates who represent at once an economic and cultural challenge, and the capacity of Gulf citizens to overcome fears of destabilizing their comparatively peaceful and comfortable countries through concerted political mobilization and activism. Other takeaways are less positive. The state’s tendency to fall back on economic benefaction as an antidote to perceived political strain is a testament to the resilience of the rentier system. Rentier retrenchment has not been limited to Qatar, with Kuwait and Oman also delaying implementation of the 5% VAT until at least 2021,Footnote51 and Bahrain and Saudi Arabia rolling back some subsidy reforms in response to public pressure.Footnote52 One expects that the other long-term changes in social and state-society relations examined here will also proceed in fits and starts.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Justin Gengler

Justin Gengler is Research Assistant Professor at the Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI), Qatar University, PO Box 2713, Doha, Qatar.

Notes

1 Gengler and Al-Khelaifi, “Crisis, State Legitimacy, and Political Participation in a Non-Democracy: How Qatar Withstood the 2017 Blockade”, Middle East Journal 73.3 (2019), pp. 397–416; Mitchell and Allagui, “Car Decals, Civic Rituals, and Changing Conceptions of Nationalism”, International Journal of Communication 13 (2019), pp. 1368–88; and some contributions in Miller (ed.), The Gulf Crisis: The View from Qatar (2018). Restrictions on social research in the blockading countries means that, to the author’s knowledge, no study has examined the domestic sociopolitical impacts of, or attitudes toward, the GCC crisis in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, or Egypt.

2 For more, see Gengler and Al-Khelaifi, “Crisis, State Legitimacy, and Political Participation in a Non-Democracy”.

3 Mitchell and Allagui, “Car Decals, Civic Rituals, and Changing Conceptions of Nationalism”.

4 Gengler and Al-Khelaifi, “Crisis, State Legitimacy, and Political Participation in a Non-Democracy”.

5 See, e.g., Longva, Walls Built on Sand: Migration, Exclusion, and Society in Kuwait (1997); Khalaf, AlShehabi, Hanieh, Transit States: Labour, Migration and Citizenship in the Gulf (2015); and AlShehabi, “Policing Labour in Empire: The Modern Origins of the Kafala Sponsorship System in the Gulf Arab States”, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (2019), pp. 1–20.

6 Vora, Impossible Citizens: Dubai’s Indian Diaspora (2013); Vora and Koch, “Everyday Inclusions: Rethinking Ethnocracy, Kafala, and Belonging in the Arabian Peninsula”, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 15.3 (2015), pp. 540–52.

7 Global Labour Markets and Migration (GLMM), “GCC: Total Population and Percentage of Nationals and Non-Nationals in GCC Countries (National Statistics, 2017‒2018)” (2020).

8 Longva, “Keeping Migrant Workers in Check: The Kafala System in the Gulf”, Middle East Report 211 (1999), pp. 20–2; Okruhlik, “Dependence, Disdain, and Distance: State, Labor, and Citizenship in the Arab Gulf States”, Industrialization in the Gulf: A Socioeconomic Revolution, ed. Seznec and Kirk (2011); and Kamrava and Babar (eds), Migrant Labor in the Persian Gulf (2012).

9 Mahdavy, “Patterns and Problems of Economic Development in Rentier States: The Case of Iran”, Studies in the Economic History of the Middle East: From the Rise of Islam to the Present Day, ed. Cook (1970), pp. 438‒77; Beblawi and Luciani, “Introduction”, The Rentier State, ed. Beblawi and Luciani (1987), pp. 1–21; and Ross, “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?”, World Politics 53.3 (2011), pp. 325–61.

10 Quoted in Reardon-Anderson, “Emergence of the State of Qatar”, (2019), unpublished manuscript.

11 Global Labour Markets and Migration (GLMM), “Qatar: Population by Nationality (Qatari/non-Qatari) at Dates/Years of Census (1970‒2015)” (2020).

12 Global Labour Markets and Migration, “GCC: Total Population and Percentage of Nationals and Non-Nationals in GCC Countries”.

13 Snoj, “Population of Qatar by Nationality - 2019 Report”, Priya Dsouza Communications website, 15 August 2019.

14 E.g., Brader, Valentino, and Suhay, “What Triggers Public Opposition to Immigration? Anxiety, Group Cues, and Immigration Threat”, American Journal of Political Science 52.4 (2008), pp. 959–78; Hainmueller and Hangartner, “Who Gets a Swiss Passport? A Natural Experiment in Immigrant Discrimination”, American Political Science Review 107.1 (2013), pp. 159–87; Hainmueller and Hiscox, “Attitudes Toward Highly Skilled and Low-Skilled Immigration: Evidence from a Survey Experiment”, American Political Science Review 104.1 (2010), pp. 61–84.

15 Gengler, “The Political Costs of Qatar’s Western Orientation”, Middle East Policy 19.4 (2012), pp. 68–76.

16 Global Labour Markets and Migration (GLMM), “Qatar: Economically Active Population Aged 15 and Above by Nationality (Qatari/Non-Qatari), Sex and Activity Sector (2017)” (2020).

17 Mitchell and Gengler, “What Money Can’t Buy: Wealth, Inequality, and Economic Satisfaction in the Rentier State”, Political Research Quarterly 72.1 (2019), pp. 75–89.

18 Thiollet, “Managing Migrant Labour in the Gulf: Transnational Dynamics of Migration Politics since the 1930s”, International Migration Institute Working Paper 131 (2016), pp. 1‒25.

19 Johnston, “Authoritarian Abdication: Bargaining Power and the Role of Firms in Migrant Welfare”, Studies in Comparative International Development 52.3 (2017), pp. 301–26.

20 Two apt illustrations are Aziz, “Qatar ‘Stronger, United’ One Year after Blockade”, Al-Jazeera, 4 June 2018; and The Peninsula, “Expat Community Stands with Qatar”, 24 September 2017.

21 E.g., Mitchell and Allagui, “Car Decals, Civic Rituals, and Changing Conceptions of Nationalism”.

22 Ibid.

23 It is worth noting that the same might be said of expatriate populations on the other side of the blockade.

24 Dharar, “Tamim al-Majd: Aʿtaz bi-shaʿbi w-al-muqimin.. wa Twitter yarud: Nahnu man naʿtaz bik” [Tamim al-Majd: I Cherish My People and Residents.. and Twitter Replies: We Are the Ones Who Cherish You], Al-Sharq, 19 September 2017; The Peninsula, “Emir’s Speech has Made Entire Country Proud, Say Residents”, 20 September 2017.

25 Qatar Tribune, “Grand Welcome for HH Emir at Corniche Today”, 24 September 2017.

26 Al-Jazeera, “Qatar Welcomes Asian Cup Football Champions Home”, 3 February 2019.

27 Here and elsewhere, the categories “expatriates” and “residents” refer to non-Qatari white-collar professional workers, as distinguished from unskilled blue-collar migrant laborers.

28 The source for all figures in this paper is SESRI, Qatar University.

29 Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (1954).

30 E.g., Koch, “Is Nationalism Just for Nationals? Civic Nationalism for Noncitizens and Celebrating National Day in Qatar and the UAE”, Political Geography 54 (2016), pp. 43–53.

31 See Gengler and Al-Khelaifi, “Crisis”.

32 Gengler, “The Political Economy of Sectarianism in the Gulf”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Luce Foundation Paper, 29 August 2016; Gengler, “The Political Economy of Sectarianism in the Gulf Region”, Beyond Sunni and Shia: The Roots of Sectarianism in a Changing Middle East, ed. Wehrey (2017), pp. 181‒203.

33 An alternative if less persuasive explanation linking the blockade to greater citizen political interest is the idea that Qataris attributed the GCC crisis in some large part to the government’s own unchecked (foreign) policy decisions, and so became more active in expressing political opinions and engaging in local politics in an attempt to shift the substantive direction of policy.

34 Gengler, “Qatar’s Ambivalent Democratization”, Foreign Policy, 1 November 2011.

35 Anon. interview (Qatari), Doha, October 2019.

36 Quoted in Gengler and Lambert, “Renegotiating the Ruling Bargain: Selling Fiscal Reform in the GCC”, Middle East Journal 70.2 (2016), p. 322.

37 Hertog, “The GCC Economic Model in the Age of Austerity”, The Gulf Monarchies Beyond the Arab Spring: Changes and Challenges, ed. Narbone and Lestra (2015), pp. 5–11; Krane, “The Political Economy of Subsidy Reform in the Persian Gulf Monarchies”, The Economics and Political Economy of Energy Subsidies, ed. Strand (2016), pp. 191–223; and Krane, “Political Enablers of Energy Subsidy Reform in Middle Eastern Oil Exporters”, Nature Energy 3.7 (2018), pp. 547‒52. Cancellation of the insurance program is cited in Gengler and Lambert, “Renegotiating the Ruling Bargain”.

38 As is visible in , the close correspondence between increased political interest and increased democratic interest appears to break down between 2018 and 2019: the former retreats while the latter persists at the same high level. This may indicate a disconnect between heightened democratic aspirations and actual opportunity for formal political participation after the blockade. Additional data from subsequent periods will be necessary to confirm the existence and significance of this potential divergence.

39 E.g., Al-Rasheed, “Sectarianism as Counter-Revolution: Saudi Responses to the Arab Spring”, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 11.3 (2011), pp. 513–26; Brumberg, “Transforming the Arab World’s Protection-Racket Politics”, Journal of Democracy 24.3 (2013), pp. 88–103.

40 Revenue estimates taken from International Trade Centre (ITC) Trade Map, “List of Exporters for the Selected Product - Product: 2709 Petroleum Oils and Oils Obtained from Bituminous Minerals, Crude” (2019), see: “ITC: Exports of Petroleum Oils and Oils Obtained from Bituminous Minerals, Crude (Code 2709)”; and “ITC: Exports of Petroleum Gas and Other Gaseous Hydrocarbons (Code 2711)”.

41 Mitchell, Beyond Allocation: The Politics of Legitimacy in Qatar, PhD diss. (2013).

42 Government Communications Office, Qatar, “Shura Council” (2020).

43 Parasie, “As Oil Profits Plunge Gulf Regimes Weigh the Unmentionable: Taxes”, The Wall Street Journal, 10 February 2016.

44 Gengler; Shockley; and Ewers, “Refinancing the Rentier State: Welfare, Inequality, and Citizen Preferences toward Fiscal Reform in the Gulf Oil Monarchies”, Comparative Politics (2020).

45 Vandewalle, “Political Aspects of State Building in Rentier Economies: Algeria and Libya Compared”, The Rentier State: Nation, State and Integration in the Arab World, vol. 2, ed. Beblawi and Luciani (1987), pp. 173‒85.

46 Gengler and Lambert, “Renegotiating the Ruling Bargain”.

47 E.g., Collins, “Anti-Qatar Embargo Grinds Toward Strategic Failure”, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy Issue Brief (2018), pp. 1‒8.

48 England and Kerr, “Qatar’s Wealth Fund Brings $20bn Home to Ease Impact of Embargo”, Financial Times, 18 October 2017. For more on Qatar’s economic response to the blockade, see Wright, “The Political Economy of the Gulf Divide”, Divided Gulf: The Anatomy of a Crisis, ed. Krieg (2019), pp. 145‒59.

49 England and Kerr, “Qatar’s Wealth Fund”.

50 Gengler, “The Political Costs”.

51 Reuters, “Kuwait to Postpone VAT Implementation to 2021, Says Parliament Committee”, 15 May 2018; Barbuscia, “Oman to Delay VAT to 2021 Amid Sluggish Growth”, Reuters, 30 July 2019.

52 Alkhalisi, “Saudi Arabia Eases Austerity After ‘Very Negative’ Response”, CNN Business, 9 January 2018.

Bibliography

1 Primary sources

- Global Labour Markets and Migration (GLMM), “GCC: Total Population and Percentage of Nationals and Non-Nationals in GCC Countries (National Statistics, 2017‒2018)”, (2020), available online at https://gulfmigration.org/gcc-total-population-and-percentage-of-nationals-and-non-nationals-in-gcc-countries-national-statistics-2017-2018-with-numbers.

- Global Labour Markets and Migration (GLMM), “Qatar: Economically Active Population Aged 15 and Above by Nationality (Qatari/Non-Qatari), Sex and Activity Sector (2017)” (2020), available online at https://gulfmigration.org/qatar-economically-active-population-aged-15-and-above-by-nationality-qatari-non-qatari-sex-and-activity-sector-2017.

- Global Labour Markets and Migration (GLMM), “Qatar: Population by Nationality (Qatari/non-Qatari) at Dates/Years of Census (1970‒2015)” (2020), available online at https://gulfmigration.org/qatar-population-by-nationality-qatari-non-qatari-at-dates-years-of-census-1970-2015.

- Government Communications Office, Qatar, “Shura Council” (2020), available online at www.gco.gov.qa/en/about-qatar/shura-council.

2 Secondary sources

- Al-Jazeera, “Qatar Welcomes Asian Cup Football Champions Home”, 3 February 2019, available online at www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/02/live-updates-japan-qatar-asian-cup-final-190201110503552.html.

- Alkhalisi, Zahraa, “Saudi Arabia Eases Austerity After ‘Very Negative’ Response”, CNN Business, 9 January 2018, available online at https://money.cnn.com/2018/01/09/news/economy/saudi-arabia-austerity-backlash/index.html.

- Khalaf, Abdulhadi; Omar AlShehabi; Adam Hanieh, Transit States: Labour, Migration and Citizenship in the Gulf (London: Pluto Press, 2015).

- AlShehabi, Omar Hesham, “Policing Labour in Empire: The Modern Origins of the Kafala Sponsorship System in the Gulf Arab States”, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (2019), pp. 1–20, available online at www.academia.edu/39648614/Policing_Labour_in_Empire_The_Modern_Origins_of_the_Kafala_Sponsorship_System_in_the_Gulf_Arab_States doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2019.1580183

- Allport, Gordon, The Nature of Prejudice (Cambridge: Perseus Books, 1954).

- Al-Rasheed, Madawi, “Sectarianism as Counter-Revolution: Saudi Responses to the Arab Spring”, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 11.3 (2011), pp. 513–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9469.2011.01129.x

- Aziz, Saba, “Qatar ‘Stronger, United’ One Year after Blockade”, Al-Jazeera, 4 June 2018, available online at www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/06/qatar-stronger-united-year-blockade-180603132928052.html.

- Barbuscia, Davide, “Oman to Delay VAT to 2021 Amid Sluggish Growth”, 30 July 2019, Reuters, available online at www.reuters.com/article/us-oman-economy-vat/oman-to-delay-vat-to-2021-amid-sluggish-growth-idUSKCN1UP1TM.

- Beblawi, Hazem and Giacomo Luciani, “Introduction”, The Rentier State, edited by Hazem Beblawi and Giacomo Luciani (London: Croom Helm, 1987), pp. 1–21

- Brader, Ted; Nick Valentino; and Elizabeth Suhay, “What Triggers Public Opposition to Immigration? Anxiety, Group Cues, and Immigration Threat”, American Journal of Political Science 52.4 (2008), pp. 959–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00353.x

- Brumberg, Daniel, “Transforming the Arab World’s Protection-Racket Politics”, Journal of Democracy 24.3 (2013), pp. 88–103. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2013.0042

- Collins, Gabriel, “Anti-Qatar Embargo Grinds Toward Strategic Failure”, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy Issue Brief, 22 January 2018, pp. 1‒8, available online at www.bakerinstitute.org/media/files/files/7299ac91/bi-brief-012218-ces-qatarembargo.pdf.

- Dharar, Abdulrahman al-Raheem, “Tamim al-Majd: Aʿtaz bi-shaʿbi w-al-muqimin.. Wa Twitter yarud: Nahnu man naʿtaz bik” [Tamim al-Majd: I Cherish My People and Residents.. and Twitter Replies: We Are the Ones Who Cherish You], Al-Sharq, 19 September 2017, available online at www.al-sharq.com/article/19/09/2017/تميم-المجد-أعتز-بشعبي-والمقيمين-وتويتر-يرد-نحن-من-نعتز-بك.

- England, Andrew and Simeon Kerr, “Qatar’s Wealth Fund Brings $20bn Home to Ease Impact of Embargo”, Financial Times, 18 October 18 2017, available online at www.ft.com/content/47f307a2-b365-11e7-a398-73d59db9e399.

- Gengler, Justin and Buthaina Al-Khelaifi, “Crisis, State Legitimacy, and Political Participation in a Non-Democracy: How Qatar Withstood the 2017 Blockade”, Middle East Journal 73.3 (2019), pp. 397–416. doi: https://doi.org/10.3751/73.3.13

- Gengler, Justin and Laurent A. Lambert, “Renegotiating the Ruling Bargain: Selling Fiscal Reform in the GCC”, Middle East Journal 70.2 (2016), pp. 321–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.3751/70.2.21

- Gengler, Justin, “Qatar’s Ambivalent Democratization”, Foreign Policy, 1 November 2011, available online at https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/11/01/qatars-ambivalent-democratization.

- Gengler, Justin, “The Political Costs of Qatar’s Western Orientation”, Middle East Policy 19.4 (2012), pp. 68–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4967.2012.00560.x

- Gengler, Justin, “The Political Economy of Sectarianism in the Gulf”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Luce Foundation Paper, 29 August 2016, available online at https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/08/29/political-economy-of-sectarianism-in-gulf-pub-64410.

- Gengler, Justin, “The Political Economy of Sectarianism in the Gulf Region”, Beyond Sunni and Shia: The Roots of Sectarianism in a Changing Middle East, edited by Frederic Wehrey (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 181–203.

- Hainmueller Jens and Dominik Hangartner, “Who Gets a Swiss Passport? A Natural Experiment in Immigrant Discrimination”, American Political Science Review 107.1 (2013), pp. 159–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000494

- Hainmueller, Jens and Michael J. Hiscox, “Attitudes Toward Highly Skilled and Low-Skilled Immigration: Evidence from a Survey Experiment”, American Political Science Review 104.1 (2010), pp. 61–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990372

- Hertog, Steffen, “The GCC Economic Model in the Age of Austerity”, The Gulf Monarchies Beyond the Arab Spring: Changes and Challenges, edited by Luigi Narbone and Martin Lestra (Florence: European University Institute, 2015), pp. 5–11.

- International Trade Centre (ITC) Trade Map, “List of Exporters for the Selected Product - Product: 2709 Petroleum Oils and Oils Obtained from Bituminous Minerals, Crude” (2019), available online at www.trademap.org/Country_SelProduct_TS.aspx?nvpm=1%7c%7c%7c%7c%7c2709%7c%7c%7c4%7c1%7c1%7c2%7c2%7c1%7c2%7c1%7c1.

- International Trade Centre (ITC) Trade Map, “List of Exporters for the Selected Product - Product: 2711 Petroleum Gas and Other Gaseous Hydrocarbons” (2019), available online at www.trademap.org/Country_SelProduct_TS.aspx?nvpm=1%7c%7c%7c%7c%7c2711%7c%7c%7c4%7c1%7c1%7c2%7c2%7c1%7c2%7c1%7c1.

- Johnston, Trevor, “Authoritarian Abdication: Bargaining Power and the Role of Firms in Migrant Welfare”, Studies in Comparative International Development 52.3 (2017), pp. 301–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-016-9225-7

- Kamrava, Mehran and Zahra Babar (eds), Migrant Labor in the Persian Gulf (New York: Columbia University Press/Hurst, 2012).

- Koch, Natalie, “Is Nationalism Just for Nationals? Civic Nationalism for Noncitizens and Celebrating National Day in Qatar and the UAE”, Political Geography 54 (2016), pp. 43–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.09.006

- Krane, Jim, “Political Enablers of Energy Subsidy Reform in Middle Eastern Oil Exporters”, Nature Energy 3.7 (2018), pp. 547–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-018-0113-4

- Krane, Jim, “The Political Economy of Subsidy Reform in the Persian Gulf Monarchies”, The Economics and Political Economy of Energy Subsidies, edited by Jon Strand (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), pp. 191–223.

- Longva, Anh Nga, “Keeping Migrant Workers in Check: The Kafala System in the Gulf”, Middle East Report 211 (1999), pp. 20–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3013330

- Mahdavy, Hussein, “Patterns and Problems of Economic Development in Rentier States: The Case of Iran”, Studies in the Economic History of the Middle East: From the Rise of Islam to the Present Day, edited by M. A. Cook (London: Oxford University Press, 1970), pp. 438–77.

- Miller, Rory (ed.), The Gulf Crisis: The View from Qatar (Doha: Hamad bin Khalifa University Press, 2018).

- Mitchell, Jocelyn S., Beyond Allocation: The Politics of Legitimacy in Qatar, PhD Dissertation (Washington, DC: Georgetown University, 2013).

- Mitchell, Jocelyn S. and Ilhem Allagui, “Car Decals, Civic Rituals, and Changing Conceptions of Nationalism”, International Journal of Communication 13 (2019), pp. 1368–88.

- Mitchell, Jocelyn S. and Justin Gengler, “What Money Can’t Buy: Wealth, Inequality, and Economic Satisfaction in the Rentier State”, Political Research Quarterly 72.1 (2019), pp. 75–89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918776128

- Okruhlik, Gwenn, “Dependence, Disdain, and Distance: State, Labor, and Citizenship in the Arab Gulf States”, Industrialization in the Gulf: A Socioeconomic Revolution, edited by Jean-François Seznec and Mimi Kirk (New York: Routledge, 2011), pp. 145–62.

- Parasie, Nicolas, “As Oil Profits Plunge Gulf Regimes Weigh the Unmentionable: Taxes”, The Wall Street Journal, 10 February 2016, available online at www.wsj.com/articles/as-oil-profits-plunge-gulf-regimes-weigh-the-unmentionable-taxes-1455155457.

- Qatar Tribune, “Grand Welcome for HH Emir at Corniche Today”, 24 September 2017, available online at www.qatar-tribune.com/news-details/id/86980.

- Reardon-Anderson, James, “Emergence of the State of Qatar” (2019), unpublished manuscript.

- Reuters, “Kuwait to Postpone VAT Implementation to 2021, Says Parliament Committee”, 15 May 2018, available online at www.reuters.com/article/us-kuwait-economy-tax/kuwait-to-postpone-vat-implementation-to-2021-says-parliament-committee-idUSKCN1IG0OW.

- Ross, Michael L., “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?”, World Politics 53.3 (2011), pp. 325–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2001.0011

- Snoj, Jure, “Population of Qatar by Nationality - 2019 Report”, Priya Dsouza Communications website, 15 August 2019, available online at http://priyadsouza.com/population-of-qatar-by-nationality-in-2017.

- The Peninsula, “Emir’s Speech has Made Entire Country Proud, Say Residents”, 20 September 2017, available online at www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/20/09/2017/Emir%E2%80%99s-speech-has-made-entire-country-proud,-say-residents.

- Thiollet, Hélène, “Managing Migrant Labour in the Gulf: Transnational Dynamics of Migration Politics since the 1930s”, International Migration Institute Working Paper 131 (2016), pp 1–25, available online at https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01346366.

- Vandewalle, Dirk, “Political Aspects of State Building in Rentier Economies: Algeria and Libya Compared”, The Rentier State: Nation, State and Integration in the Arab World, vol. 2, edited by Hazem Beblawi and Giacomo Luciani (London: Croom Helm, 1987), pp. 173–85.

- Vora, Neha and Natalie Koch, “Everyday Inclusions: Rethinking Ethnocracy, Kafala, and Belonging in the Arabian Peninsula”, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 15.3 (2015), pp. 540–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/sena.12158

- Vora, Neha, Impossible Citizens: Dubai’s Indian Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

- Wright, Steven, “The Political Economy of the Gulf Divide”, Divided Gulf: The Anatomy of a Crisis, edited by Andreas Krieg (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), pp. 145–59.