Abstract

On the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the Journal of Arabian Studies (JAS), this article offers the first history of the field of Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies (GAPS), including the origins and evolution of JAS. It begins with an overview of the origins and evolution of GAPS as a field of scholarship, then provides a detailed survey of the field’s institutional development, which can be traced back to the region’s post-war oil wealth and the large oil-funded archaeological expeditions of the 1950s–60s. This is reflected in GAPS’s first societies, centres, and journals, which catered exclusively to archaeologists, historians, and Arabists. The transformation of GAPS into a global interdisciplinary field (encompassing both humanities and social sciences) began in 1969, although it remained a fringe field within Middle East Studies. The expansion of GAPS into a mainstream field in its own right began in the 2000s, reaching critical mass in the 2010s, resulting in the establishment of the Association for Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies (AGAPS) and the launch of JAS. In the past decade, GAPS also expanded beyond Middle East Studies to embrace Indian Ocean Studies. The article concludes with an overview of JAS’s first decade: 2011–20.

1 Introduction

This issue marks the 10th anniversary of the Journal of Arabian Studies –– the third incarnation of a journal that began as Arabian Studies (University of Cambridge, 1974–90) and then New Arabian Studies (University of Exeter, 1994–2004). While the scope of these predecessors was limited to the humanities and mostly pre-20th century in order to avoid “controversial topics” like contemporary politics and “purely scientific topics” such as economics,Footnote1 JAS broke new ground by incorporating social science subjects and extending its scope to the present day. JAS is the leading international refereed scholarly journal focusing on the Arabian Peninsula, its surrounding waters, and their connections with the western Indian Ocean (from West India to East Africa), from antiquity to the present day, in all disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences. For the past year, it has been included in Scopus, the world’s largest citation index of peer-reviewed journals –– a step that only happens after the most rigorous external scrutiny of a journal.

In this survey, we discuss the origins of Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies as an academic field and the scholarship boom that has coincided with the lifespan of this journal and its predecessors. We then explain the institutional development of the field from the 1950s through to today before concluding with our reflections on the journal’s first decade.

2 The academic study of the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula

2.1 Origins and early days

While scholars and others have been writing about the Arabian Peninsula since the days of Herodotus,Footnote2 if not earlier, the first modern scientific studies of the Arabian Peninsula were unpublished Dutch East India Company reports on Mocha and Oman from 1614–74, followed by two published Dutch accounts by François Valentijn on Mocha (1726) and Cornelis Eyks on Oman (1766).Footnote3 The first institutional academic study by subject matter experts was the royal Danish scientific expedition to Arabia in 1761–7,Footnote4 which resulted in Carsten Niebuhr’s two books on the Arabian Peninsula published during 1772–78 –– the first attempt at a comprehensive scientific survey of the entire peninsula.Footnote5 Over the next two centuries, an increasing number of scholarly publications appeared internationally, the majority written by lay experts –– most being Western officials stationed in, or travellers to, the region who had a personal interest in its archaeology, history, society, or geography. Examples include the archaeological investigations of Bahrain by Edward Durand and Francis Prideaux; the ethnographic and historical studies of South Yemen by Frederick M. Hunter, of Kuwait by Harold Dickson, and of eastern Arabia by Samuel Zwemer and Paul Harrison; the historical works on Oman by Vincenzo Maurizi, George Percy Badger, and Samuel B. Miles, on Saudi Arabia by St John Philby, on the Trucial States (UAE) by Sir Donald Hawley, on Yemen by Daniel van der Meulen, Harold Ingrams, and Eric Macro, and on the Gulf in general by Sir Lewis Pelly, Sir Arnold Wilson, and Sir Rupert Hay; the geographical and historical studies by Albrecht Zehme and Aloys Sprenger; the geographical explorations of and writings on Arabia by James Raymond Wellsted, Henry Whitelock, Charles Huber, Charles Forster, Bertram Thomas, and Sir Wilfred Thesiger; the photographs and travel accounts of Yemen and the Gulf by Herman Burchardt; as well as the famous travel accounts by Ludovico di Varthema, Joseph Pitts, Jean de la Roque, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, William Heude, G. Forster Sadleir, Adolph von Wrede, Heinrich von Maltzan, Gifford Palgrave, Carlo Guarmani, Lady Anne Blunt, Charles Doughty, Sir Richard Burton, John F. Keane, Robert E. Cheesman, T.E. Lawrence, Hugh Scott, and Alan Villiers.Footnote6 The (British) government of India also produced a number of important scholarly publications in the 19th and 20th centuries, not least John Lorimer’s Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, ‘Oman, and Central Arabia (1908, 1915) and Jerome Saldanha’s 17-volume Précis series on the Gulf (1903–08), but they were secret at the time and did not become available to the public until 1950s–70s.Footnote7

Within the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula, a smaller number of Arab and Persian writers (mainly historians) were active –– such as Husain Ibn Ghannam in the early 19th century; Uthman Ibn Bishr and Humayd Ibn Ruzayq in the mid-19th century; Othman Al-Basri in the late 19th century; Mahmoud Al-Alusi, Khalid Al-Bassam, Abdul-Rahman Al-Khayri, Nasser Al-Khairi, Khalifa Al-Nabhani, Nur al-Din Al-Salimi, Muhammad Ali Sadid Al-Saltana (Kababi), Muhammad Al-Tajir, Abdulaziz Al-Rashid, Yousef Al-Qinaʿi, and Husain Nasif in the early 20th century; and Salah Al-Bakri, Muhammad bin Nur al-Din Al-Salimi, Saif Al-Shamlan, Salim bin Hamud Al-Siyabi, Abdullah Al-Jarafi, Abd al-Wasi Al-Wasiʿi, Khayr Al-Din Al-Zirkali, and ʿAbd al-Haqq Naqshabandi in the mid-20th century. While they were naturally familiar with each others’ work within their own circles, and they and their works circulated around the India Ocean through the Arab diaspora,Footnote8 they were somewhat disconnected from their European and American counterparts before the mid-20th century due to the relatively poor access each had to the others’ work. Even though a fair number of writers from the Arabian Peninsula published their books in Cairo, Bombay (Mumbai), Singapore, and Batavia (Jakarta), their works were acquired by just a handful of libraries outside the Middle East, India, and the Malay Peninsula and Archipelago. Another problem was that some books were available only in manuscript form and were not published until long after the author’s death. Finally, only a handful of the Arabic books on Arabia were translated and published in the West, such as Ibn Raziq’s History of the Imams and Sayyids of Oman (covering 661–1856 AD), which George Percy Badger translated into English and the Hakluyt Society in London published in 1871.Footnote9

The study of the Arabian Peninsula as a modern field of professional scholars based at academic institutions (universities, academies, museums, libraries) emerged during the mid-19th to mid-20th century. In the West, this took place within the context of Oriental Studies, where the field was dominated by humanities scholars –– Arabists (specialising in the language and classical texts of the Arabian Peninsula), epigraphers, archaeologists, historians, and ethnographers –– as well as geographers. Pioneering scholars included the Arabist-explorer Georg August Wallin; Arabists Michael Jan de Goeje, Julius Euting, C. Snouck Hurgronje, Robert B. Serjeant, George Rentz, A.F.L. Beeston, Jacques Ryckmans, and R. Bayly Winder; Arabian epigraphists David Heinrich Müller and Gonzague Ryckmans; geographers Carl Ritter and Alexander Melamid; Arabist-archaeologists Eduard Glaser and Joseph Halévy; archaeologists Theodore and Mabel Bent, D.G. Hogarth, Ernest Mackay, Peter Bruce Cornwall, Gertrude Caton-Thompson, Frank P. Albright, Richard Le Baron Bowen Jr., Ray L. Cleveland, Wendell Phillips, P.V. Glob, Geoffrey Bibby, Holger Kapel, Tareq Rajab, Abdulrahman Al-Ansary, and Gerald Lankester Harding; anthropologists Alois Musil, Peter Lienhardt, Klaus Ferdinand, Jette Bang, and Henny Harald Hansen; ethnomusicologist Poul Rovsing Olsen; and the historians J.B. Kelly, Stephen Hemsley Longrigg, and Ameen Rihani.Footnote10

2.1.1 The 1960s—1970s

The 1960s–70s witnessed an expansion of scholarship on the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula beyond the humanities to include the first social scientists and legal scholars to analyse the region’s contemporary affairs –– an expansion that was part of the post-war development of Middle Eastern Studies (and Area Studies more broadly). Pioneers included the legal scholars Husain Al-Baharna and Herbert Liebesny; sociologists Muhammad Al-Rumaihi and Jean-Jacques Berreby; architect and urban geographer Saba George Shiber; political scientists M.S. Agwani, John Duke Anthony, Fred Halliday, Jacqueline Ismael, Majid Khadduri, Enver Koury, Helen Lackner, David E. Long, Emile Nakhleh, Tim Niblock, James Piscatori, Muhammad Sadik, and Jean-Louis Soulié; security specialists Anthony Cordesman and Alvin J. Cottrell; economists J.S. Birks, Ragei El-Mallakh, Kevin G. Fenelon, William Snavely, Kamal S. Sayegh, and Clive A. Sinclair; and the diplomat Lucien Champenois.Footnote11

These social scientists were joined by another generation of pioneering humanities scholars during this period, including some of the first Arab PhD graduates of Western universities to specialise on the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula: the historians Ahmad Abu-Hakima, Morsy Abdullah, Ali Khalifa Al-Kuwari, Yaqub Abdulaziz Al-Rashid, Calvin Allen, Abdul Amir Amin, Raymond D. Bathurst, Robin Bidwell, R. Michael Burrell, Briton Cooper Busch, Frank A. Clements, R.J. Gavin, Frauke Heard-Bey, Friedrich Kochwasser, Zaka Hanna Kour, Robert Landen, Joseph J. Malone, John Marlowe, Elizabeth Monroe, J.E. Peterson, Christian Julien Robin, Penelope Tuson, J.C. Wilkinson, H.V.F. Winstone, Hikoichi Yajima, and Rosemarie Said Zahlan; bibliographer/historians Derek Hopwood and Heather Bleaney; architectural historian Geoffrey King; archaeologist-cum-historian Richard I. Lawless; archaeologists Beatrice de Cardi, E.C.L. During Caspers, Paolo Costa, John E. Dayton, Brian Doe, Monique Kervran, Peter J. Parr, and Donald Witcomb; Arabists Bruce Ingham, Theodore Prochazka Jr, and G. Rex Smith; epigraphist A.G. Lundin; anthropologists Paul Bonnenfant, Abdalla Bujra, Donald Cole, Fuad Khuri, Colette Le Cour-Grandmaison, Gerald Obermeyer, and Louise E. Sweet; ethnomusicologist Simon Jargy; and the geographer Keith McLachlan.Footnote12

The emergence of this nascent community of pioneering Gulf and Arabian Studies specialists eventually resulted in the first international conferences on the region, which began in 1969. In January of that year, the newly-formed Arabian Society at the Institute of Archaeology, University of London, convened a one-day seminar at which papers were given on the archaeology of the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula by John Dayton, Peter Parr, Edmond Sollberger, Margaret Drower, and Brian Doe. This was followed by another one-day Arabian Society seminar in June on the archaeology, history, and society of the region at the Middle East Centre at Cambridge, at which six papers were presented by Robert Serjeant, Walter Dostal, David Whitehouse, Raymond D. Bathurst, Beatrice de Cardi, and Brian Doe. Finally, in March 1969, the Middle East centres at Oxford and the School of Oriental and African Studies in London convened the world’s first interdisciplinary conference on the Arabian Peninsula encompassing both the humanities and the social sciences. Presenters included the Arabist George Rentz; bibliographer/historian Derek Hopwood; historians Ahmad Abu-Hakima, Raymond D. Bathurst, R. Michael Burrell, J.B. Kelly, and J.C. Wilkinson; anthropologist Peter Lienhardt; political scientists Abbas Kelidar and Frank Stoakes; and the economists Edith Penrose, Yusif Sayigh, and Thomas Shea.

The next year, 1970, the Arabian Society convened its third seminar, now called the Seminar for Arabian Studies, at Cambridge’s Middle East Centre on the archaeology, history, Arabic, and epigraphy of the region. Key presenters included the Arabists Robert Serjeant, A.F.L. Beeston, and Jacques Ryckmans; Arabian epigraphist A.G. Lundin; historians Morsy Abdullah, Elizabeth Monroe, and J.C. Wilkinson; archaeologists Geoffrey Bibby, John Dayton, Peter Parr, Beatrice de Cardi, Brian Doe, Paolo Costa, Wilfred G. Lambert, and E.C.L. During Caspers; and the museum consultant and amateur archaeological historian Michael Rice. The Seminar for Arabian Studies has been held annually ever since and is the longest-running conference series on the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula.

The next major development was in June 1972, when the Center for Mediterranean Studies in Rome convened a four-day conference on the changing balance of power in the Gulf in the aftermath of Britain’s military withdrawal from the region the previous year, as well as recent social and economic changes. Presenters included academics, senior officials, bankers and oilmen from Britain and America.

The number of conferences gathered pace through the 1970s, culminating in 1979 with three important conferences. The first was the annual Seminar for Arabian Studies, held in July at the Middle East Centre at Cambridge –– the longest-running annual conference series on the region.Footnote13 The second was another July conference on the theme of “Strategies of Social and Economic Development in the Arab Gulf” convened by the newly-established Centre for Arab Gulf Studies at the University of ExeterFootnote14 –– the first of what would become the second-longest-running annual conference series on the region. The third was the Gulf Development Forum convened in Abu Dhabi in December: a privately-run symposium for intellectuals in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states to discuss development issues facing the region. This would become the third-longest-running annual conference series on the region, hosted by a different GCC state each year.

2.1.2 Major collaborative interdisciplinary book projects of the 1970s and early 1980s

As a result of these activities, the 1970s saw the appearance of the first collaborative interdisciplinary books on the Arabian Peninsula, beginning with the Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 1 (1971), containing the papers of the 1970 seminar: the first in what would become a key annual publication series in the field. This was followed by The Arabian Peninsula: Society and Politics (1972) edited by Derek Hopwood of Oxford’s Middle East Centre, containing the papers of the 1969 Oxford/SOAS conference.Footnote15 The same year, the findings of the 1972 Rome conference were published as The Changing Balance of Power in the Persian Gulf (1972) edited by Elizabeth Monroe, also from Oxford’s Middle East Centre.Footnote16 Finally, 1972 saw the publication of Muhammad Sadik and William Snavely’s jointly-authored Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates: Colonial Past, Present Problems, and Future Prospects, an interdisciplinary study encompassing politics, economics, and history.Footnote17

The growing number of collaborative interdisciplinary book projects in the 1970s culminated in the publication of a series of major edited volumes during 1980–82: three years marking a watershed moment for scholarship on the Gulf and the Arabian Peninsula.

One was the 729-page volume The Persian Gulf States: A General Survey (1980) edited by Alvin J. Cottrell, C. Edmund Bosworth, R. Michael Burrell, Keith McLachlan, and Roger Savory. At the time, this was the most significant interdisciplinary collaborative humanities and social sciences production on the Gulf since Lorimer’s 3,577-page Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, ‘Oman, and Central Arabia (1908, 1915), although it would soon be rivalled by Paul Bonnenfant’s 1,135-page La Péninsule Arabique d’aujourd’hui (1982), discussed below. The Persian Gulf States contains 30 chapters and appendices on eastern Arabia, southern Iraq, and southern Iran by the Arabists Bruce Ingham and George Michael Wickens; bibliographer/historian Heather Bleaney; historians C. Edmund Bosworth, R. Michael Burrell, Roger Savory, and Malcom Yapp; art historian Robert Hillenbrand; anthropologist Michael Fischer; geographers Michael Bonine, Gerald Blake, Brian Clark, Keith McLachlan, Richard Lawless, and David Imrie; political scientists James E. Dougherty and Ralph H. Magnus; and the security specialists Alvin J. Cottrell, Robert J. Hanks, and Frank T. Bray.Footnote18

The other major collaborative volume to come out in 1980 was Social and Economic Development in the Arab Gulf edited by Tim Niblock, based on papers presented at the 1979 Exeter conference.Footnote19 Authors include the political scientists Muhammad Al-Rumaihi, Fred Halliday, Emile Nakhleh, and Tim Niblock; historians J.C. Wilkinson, Rosemarie Said Zahlan, and Joseph J. Malone; anthropologist Donald Cole; media scholar Naomi Sakr; economists J.S. Birks, Clive A. Sinclair, and John Townsend; and the geographer Keith McLachlan. This was the first of the centre’s conference-based series to be published, initially with Croom Helm (nine volumes) and later with the University of Exeter Press (three volumes) and Ithaca Press (three volumes). This volume was followed in 1981–82 by two more interdisciplinary, conference-based books edited by Tim Niblock. The first, State, Society and Economy in Saudi Arabia (1981), was based on the 1980 Exeter conference on the same subject, and brought together several scholars already mentioned (John Duke Anthony, J.S. Birks, Fred Halliday, Derek Hopwood, and Clive A. Sinclair) with others, including the Middle East economist Rodney Wilson, oil economist Paul Stevens, historians Peter Sluglett and Marion Farouk-Sluglett, and the anthropologists Ugo Fabietti and Shirley Kay.Footnote20 The second book, Iraq: The Contemporary State (1982), based on the 1981 conference, was co-sponsored by the Centre for Arab Gulf Studies at the University of Basra and contained a noteworthy balance of Iraqi and Western scholars, including several of those already mentioned as well as political scientists Saad Jawad, Barry Rubin and Joe Stork, and Women Studies scholar Amal Al-Sharqi.Footnote21 The Exeter volumes, together with the other books discussed in this section, played a critical role in establishing Gulf Studies in the West, while drawing in a significant number of Arab scholars from the Arabian Peninsula and Iraq.

A further major collaborative book project to appear in 1981–82 was the four-volume “Security in the Persian Gulf” project commissioned by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), prompted by regional security concerns after the Islamic revolution in Iran, followed by the outbreak of the Iraq-Iran war:

Security in the Persian Gulf I: Domestic Political Factors (1981) edited by Shahram Chubin

Security in the Persian Gulf II: Sources of Inter-State Conflict (1981) by Robert Litwak

Security in the Persian Gulf III: Modernization, Political Development and Stability (1982) by Avi Plascov

Security in the Persian Gulf IV: The Role of Outside Powers (1982) by Shahram Chubin

The final major collaborative book project to come out in the early 1980s was the 1,135-page La Péninsule Arabique d’aujourd’hui [The Arabian Peninsula Today] (1982) edited by Paul Bonnenfant of the Institut de Recherches et d’Études sur les Mondes Arabes et Musulmans (IREMAM) in Aix-en-Provence. It contains 43 chapters spread across two volumes. Volume 1 offers a series of thematic chapters on geopolitics, Islam, oil, economic development, demographics, migration, ideology, modernisation, and foreign aid, while Volume 2 contains multidisciplinary country studies on North Yemen, South Yemen, Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Dubai, and Saudi Arabia. The work’s 30 contributors include the anthropologists Paul Bonnenfant, Colette Le Cour Grandmaison, Anie Montigny-Kozlowska (later Anie Montigny), and Jon Swanson; sociologist Gilbert Grandguillaume; art historian Lucien Golvin; historians Frauke Heard-Bey, Jean-Louis Miège, Gerald Obermeyer, Christian Julien Robin, and J.C. Wilkinson; geographers Hermann A. Escher and André Bourgey; demographers Philippe Fargues, Serge de Klebnikoff, and Hans Steffen; political scientists Olivier Carré, Pierre Rondot, and Yves Schemeil; political economist Michel Chatelus; economists Olivier Blanc, Geneviève Cayre, Bruno Le Cour Grandmaison, and Traute Wohlers-Scharf; the international relations scholars, Henri Labrousse, Pierre Marthelot, and Jean-Louis Soulié; Bahrain specialist Antoine Aubry; Yemen specialists Étienne Renaud and Michel Tuscherer; the diplomat Lucien Champenois; and the engineering scholar Jacques Longchampt.Footnote23

The above overview is intended to chart the broadening group of scholars writing on the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf, who would eventually coalesce into an international scholarly community, the story of which will be told in Section 3 below. The intellectual developments within the field, including the development of national narratives by the state-funded research centres surveyed in Section 3 below, are beyond the scope of this overview, but are discussed in a number of works listed in the Bibliography.Footnote24

Despite the slowly growing number of scholars writing on the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula, including the path-breaking collaborative volumes discussed above, the region still remained the least written about part of the Middle East. As a result, it was long regarded as a fringe field within Middle Eastern Studies. Fahad Bishara has best articulated the implications of this for Gulf historiography, although his comments can be applied more broadly to Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies as a whole:

It is no secret that the historiography of the Gulf has long been the poor cousin to its counterparts in Turkey, the Levant, and North Africa. In its representation in both academic publications and academic conferences, the Gulf has trailed far behind other regions of the Middle East, as a subfield of Middle Eastern Studies in general and in the field of Middle Eastern history in particular. For those working on Gulf history, the jeremiad has by now become well-rehearsed: the Gulf is absent from Middle Eastern history surveys until the discovery of oil. The pre-oil past has been declared largely irrelevant to the established Middle Eastern history narrative. … . As such, it was marginal and hardly worth serious consideration; from early on, surveys on the history of the Middle East preferred to leave it out altogether, and when they did include it there was (again) little beyond the arrival of oil companies and migrant workers in the 20th century. The 19th-century history of the Gulf, to say nothing of the preceding centuries, has been hardly worth a footnote in a narrative that has been dominated by the Ottoman and post-Ottoman Arab world. Scholars had long located the principal anchors of modern Middle Eastern history –– empire, scholarly circles, nationalist movements, and even colonialism –– elsewhere.Footnote25

2.2 The scholarship boom in Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies

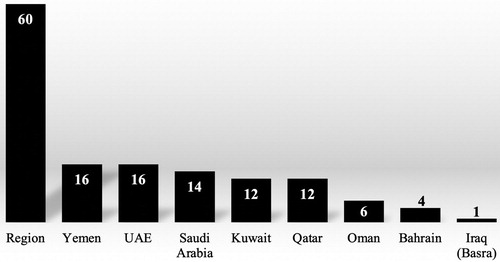

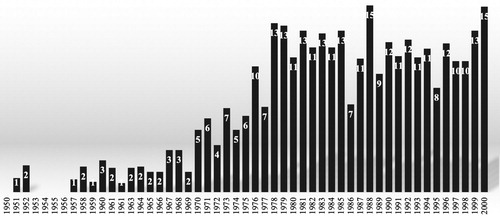

Historically, the Arabian Peninsula had long been the least-studied part of the Middle East. This state of affairs slowly began to change in the late 20th century, starting with Yemen in the 1970s. When the first issue of Arabian Studies appeared in 1974, Yemeni Studies was at the start of a boom that would catapult it into the mainstream, leaving the rest of the Arabian Peninsula in its wake. Consider, for instance, the rise in English-language books in .

Figure 1: Publication of scholarly English-language books on Yemen in the humanities and social sciences, 1950–2000Footnote26

The boom began in the humanities, then expanded to the social sciences in subsequent years. The rise in publications was due in large part to the fact that Yemen, from the 1970s onwards, was a relatively easy and affordable country for researchers to gain access to and conduct research in. This happy state of affairs continued for 40 years, until the start of the civil war in late 2014. Yemen has, once again, become a difficult country to gain access to and conduct research in, and scholarship on contemporary Yemen has declined as a result.

In sharp contrast to pre-2014 Yemen, access to the GCC states by international scholars was difficult and expensive. Research visas were hard or impossible to obtain because the GCC governments regarded most research topics in the social sciences and humanities as politically sensitive. The perceived sensitivity of seemingly innocuous topics stemmed from the poor understanding GCC government officials had about the role of scholars and scholarly research. They typically viewed research requests on almost any contemporary topic with suspicion, asking “why does this foreigner want to know these things?” Those who could obtain research visas found the high cost of living (hotels, transportation) prohibitive without research funding, which was scarce. As a result, relatively few international scholars, especially foreign PhD students, managed to conduct fieldwork in the GCC states in the 20th century. Within the GCC states themselves, governments sent a few of their own citizens each year to universities overseas to pursue PhDs in Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies on “approved topics”, but, after their graduation and return home, their scholarly output was low relative to their international counterparts. This was partly because the primary duty of professors at national universities in the GCC states was to teach, so they were burdened with heavy teaching loads (typically four courses a term, 12 classes a week). They were also concerned about government censorship or job loss, should they publish anything that deviated from the national narrative or touched on a politically-sensitive topic. This helps explains why the majority of GCC PhD graduates (especially from British and American universities) in the 20th century chose not to publish their dissertations/theses on the Gulf. The result of all this was a relatively low level of scholarly output on the GCC states by scholars both in and outside the Gulf. Although scholarship on the GCC states did slowly rise, eastern Arabia remained the least researched and written about part of the Middle East –– both in terms of publications and of papers presented at the annual conference of the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) –– until the late 1990s.

From the late 1990s onwards, US and US-affiliated universities began to open in the GCC states –– starting with the American University of Sharjah (1997), then the American University of Kuwait (2003), Georgetown University in Qatar (2005), and New York University Abu Dhabi (2010) –– which protected the academic freedom of its professors and provided a base for visiting scholars.Footnote27 Professors at these universities had time for research and were protected from government censorship, while a growing number of scholars were able to visit the GCC states for research. This eventually influenced national universities in the GCC states to accord their professors time for research and the GCC governments to permit greater academic freedom as well (at least for publications outside the country). Today, research and international peer-reviewed publication is a requirement at most universities in the GCC states. The gradual opening up to research and researchers corresponded with these states’ growing global importance and the public’s growing interest in them, which, in turn, attracted more scholars to the field. The increased number of scholars working on the GCC states is perhaps most noticeable at the annual MESA conference, where the number of panels on the GCC states has increased from one or two in the 20th century to ten by 2020.

However, the Arab Spring of 2011–12 interrupted this process for some social scientists (mainly political scientists), prompting a return to the old restrictions on those who write critically about politically-sensitive topics, as Kristian Coates Ulrichsen explains:

The increasing scholarly interest in Gulf Studies has, however, clashed with a decreasing threshold of tolerance for academic — or any other — criticism, however well-grounded or rooted in facts and evidence. Moreover, changes to the nature of scholarly engagement and academic analysis in free-to-access online platforms have intersected with the rise of the Gulf States as regional powers invested heavily in shaping the direction and pace of change in the post-Arab Spring Middle East. While this has created opportunities for scholars and students to engage in and contribute to public debate of timely and relevant issues, it also has landed many academics on security lists in individual countries and, since 2015, on the new regionwide list. When the GCC-wide list was announced, it was portrayed as a “unified terrorist blacklist,” but observers wondered if the definition would stretch to encompass critical voices. Sure enough, within weeks, reports began to appear of scholars and even students being denied entrance to countries they previously had no problems accessing.Footnote28

As more scholars were drawn to Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, some began to incorporate the field within Indian Ocean Studies –– a process JAS embraced by including the Indian Ocean within its scope from the beginning. Others began publishing in mainstream Middle East Studies journals and disciplinary journals, helping to integrate Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies into wider bodies of literature. The result was an eventual boom in publications on the GCC states, which was just beginning when the first issue of JAS appeared in 2011. Take, for instance, what had long been the least-studied country in the GCC: Qatar.

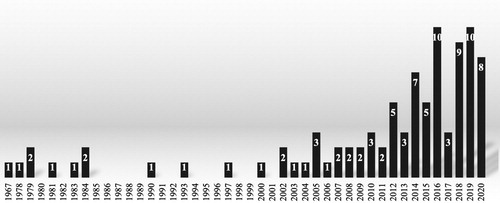

The first English-language scholarly book on Qatar to appear in the humanities and social sciences was published in 1967.Footnote30 By end of the 1970s, there were four books.Footnote31 By the end of the 1980s, there were eight. By the end of the 1990s, there were 11 –– the smallest number of any country in the Middle East. By contrast, around 350 English-language books had been published on Yemen in the humanities and social sciences by that time. The 2000s marked the start of serious global interest in the GCC states. In that decade, the number of books on Qatar more than doubled from 11 to 26. The 2010s were the decade in which the GCC states became global players, and global scholarly interest increased accordingly. This is when the boom in scholarship took off: the number of books on Qatar more than tripled that decade, from 26 to 83. In the first nine months of 2020 alone, eight books were published, four times the annual average of a decade earlier –– see .

Figure 2: Publication of scholarly English-language books on Qatar in the humanities and social sciences, 1967–2020Footnote32

But this was just the tip of the iceberg: for every book on Qatar, several more article-length studies appeared, twelve of them in this journal. Qatar and the other GCC states now enjoy the same scholarly attention as Yemen and the rest of the Middle East and Indian Ocean. Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, as a whole, is now mainstream. This is reflected in the large number of active publication series in the field today: 83, most launched since 2000 (see Appendix A).

The rise of Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies within Middle Eastern Studies and its incorporation into Indian Ocean Studies is nicely symbolized by the front cover of the latest issue of the International Journal of Middle East Studies, which features a historical photograph of a Gulf dhow off the coast of Kenya in the early to mid-20th century— see .Footnote33 The image is from the lead article in that issue by Fahad Bishara, who seeks “to re-situate the Gulf historically as part of the Indian Ocean world rather than the terrestrial Middle East.”Footnote34

While the boom in contemporary studies on the GCC states is a natural reflection of the states’ growing global importance over the same time, the rise in historical studies since 2015 was facilitated by the launch of the Qatar Digital Library (www.QDL.qa) in late 2014, which has placed two million pages of the British Library’s historical Gulf collection online to date. For the past three years, one of JAS’s editors, James Onley, has led the Qatar National Library’s search for more historical material for the QDL in the BL and other archives in Britain, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, Turkey, India, and the Gulf region itself. The QDL is now the largest digital archive on the Middle East. Its focus on the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula makes this region the easiest part of the Middle East and Indian Ocean to conduct archival research on, from anywhere in the world.

3 The institutional development of Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies

While Gulf and Arabian Peninsula as a modern academic field of study began in the mid-19th century, the field’s institutional development as an organised community of scholars (with societies, centres, publication series, activities, and large team-based projects) did not begin until the mid-20th century. What follows below is a narrative of this development, focusing on the major projects, societies, centres, and journals. A more detailed, chronological list of these developments can be found in Appendix B.

3.1 Origins and early days

The origins of the field’s institutional development can be traced back to the dawn of the oil era in Arabian Peninsula and the sudden availability of funding for research, starting with a series of large archaeological expeditions, which, in turn, generated the momentum that led directly to the foundation of the first societies, centres, activities, and publication series. The first large archaeological expeditions were organised by Wendell Phillips, a wealthy oil-concession holder with a passion for archaeology who founded the American Foundation for the Study of Man in 1949, the non-profit organisation through which he funded archaeological expeditions on the Arabian Peninsula and published their findings. In 1950, Phillips assembled a team of professional archaeologists led by Frank P. Albright for four highly-publicized expeditions to the Aden Protectorate (1950–1), North Yemen (1951–2), and Oman (1952–3, 1958–60). The discoveries, press coverage, and rapid publications by Phillips, Albright, and their team in the world’s first book series on the Arabian Peninsula greatly popularised the academic study of the Arabia Peninsula in the post-war West.Footnote35 Archaeologists working on other parts of the Middle East took notice and turned their attention to the Arabian Peninsula, where archaeology had made few inroads.

Soon after, the Danish archaeological expeditions to the Gulf began, which were to have an even greater impact. They were initiated by Peter V. Glob, Professor of Archaeology at Åarhus University and Director of the Prehistoric Museum (now the Moesgård Museum) in Åarhus, Denmark. He was assisted by Geoffrey Bibby, a Briton who had worked for the Iraq Petroleum Company in Bahrain during 1947–9 and had been impressed by the Dilmun burial mounds on the island. While these had been investigated by archaeologists in small-scale digs,Footnote36 they had never been the subject of a large, team-based archaeological expedition and no one had been able to find the settlements of the people who built them. The expedition became possible because the Ruler of Bahrain agreed to contribute funds towards it, which was unheard of for archaeological expeditions at the time. Later, the Bahrain Petroleum Company, Danish Scientific Foundation, and Carlsberg Foundation also contributed funding. This funding model laid the foundations for modern, post-war archaeology in the GCC states.Footnote37 Glob and Bibby’s expeditions to Bahrain (1953–65, 1970, 1978) generated considerable interest across eastern Arabia, leading to additional government-funded expeditions to Qatar (1956–64, 1973–4), Kuwait (1958–63), Abu Dhabi (1958–72), Saudi Arabia (1962–65, 1968–9), and Oman (1972–3).Footnote38 In the Danish expedition’s first year, it helped found the world’s first Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies society in 1953: the Bahrain Historical and Archeological Society, with its research library, event series, and scholarly journal, Dilmun: Journal of the Bahrain Historical and Archaeological Society, launched in 1971. The society’s first public event was an exhibition of the expedition’s findings in Bahrain. In the late 1950s, the expedition was joined by a Danish ethnomusicologist in Bahrain (Poul Rovsing Olsen) and two Danish anthropologists in Qatar (Klaus Ferdinand and Jette Bang), followed in 1960 by another Danish anthropologist in Bahrain (Henny Harald Hansen).Footnote39

The findings of the Danish expeditions in the Gulf were showcased to the world at the Third International Conference on Asian Archaeology in Manama in March 1970 on the occasion of the opening of the first Bahrain Museum. The conference was well attended by government representatives from the other Gulf states and archaeologists from the region and the West –– about 120 people in total. In his report on the conference, Richard Barnett, the Keeper of Western Asiatic Antiquities at the British Museum, explained:

The conference [was] opened by H.H. Sheikh Issa [the Ruler of Bahrain]. … . Particular stress … . was laid on the archaeology of the Persian Gulf. This is a subject that has now, largely as a result of this congress, emerged as an increasingly important field of study in its own right.

This accent on the archaeology of the Gulf and of the immediately adjacent regions was of course assisted, if not created in a favourable climate, by the presence of the Danish archaeological expedition led by Professor P.V. Glob and Dr G. Bibby, whose successful excavations at Barbar, at Qalaat el Bahrein, and at various of the Bahrein burial mounds, were visited by the congressists in the sessions. … . A most welcome aspect of the conference was the active and lively participation of Arab scholars and authorities at all levels. … . After the conclusion of the congress, a select party of 14 was most generously invited by H.H. the Ruler of Abu Dhabi to visit Abu Dhabi and the Danish excavations there.Footnote40

Another factor making these missions possible was oil, as Geoffrey Bibby explains:

There is hardly a government or an oil company in the Arabian Gulf which has not repeatedly come to our aid with grants of money, with loan of houses and tents, of transport and heavy equipment, of maps and instruments and air photographs, with analysis of samples or with radio-carbon dating.Footnote42

The new-found oil wealth and interest in Arabian history and heritage also led to the establishment of the world’s first Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies research centres and de facto national archives: in Abu Dhabi, Doha, Riyadh, Basra, Ṣanʿāʾ, and Aden. The first of these was the Documents and Research Bureau, founded by the Abu Dhabi government in 1968, later renamed the Center for Documentation and Research (CDR) in 1972, and housed for many years in Qasr al-Hosn, the old fort of Abu Dhabi. Its first Director was the Emirati historian, Morsy Abdullah. The CDR was a de facto national archive, library, and research centre dedicated initially to Trucial States history, and later to Gulf and Arabian Peninsula history, with its own book series and programme of lectures and conferences. One of the JAS’s Editorial Board members, Frauke Heard-Bey, was a founding member of this centre. Today, it is the National Archives of the UAE.

Next came the King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives (known as Al-Dara) in Riyadh, founded by the Saudi government in 1972. Al-Dara houses a de facto national archive, research library, and research department dedicated to Saudi history and heritage, convenes lectures and occasional conferences, funds research, and publishes its own journal, Al-Dara, launched in 1975, along with a history magazine and occasional books. It also maintains a number of subordinate research centres established over the years, including the King Salman bin Abdulaziz Center for the Restoration and Preservation of Historical Materials (2005), the History of Mecca Center (2008), the Medina Research and Studies Centre (2011), the Red Sea and Western Saudi Arabia History Center (2013), and the Saudi Digital History Center (2018).

1972 also saw the establishment of Yemen’s first national studies centre: the Yemen Center for Studies and Research (YCSR) in Ṣanʿāʾ, founded by the Yemeni poet and writer, Abdulaziz al-Maqaleh. The YCSR is a semi-autonomous research centre affiliated with Ṣanʿāʾ University, which maintains a research library and archive. It documents, researches, publishes, and convenes public lectures on Yemeni history and heritage.

Three more research centres followed in 1974. The first was the Centre for Arab Gulf Studies at the University of Basra, the world’s first interdisciplinary Gulf Studies institution, encompassing both the humanities and social sciences. It was home to a renowned archive and research library that, sadly, was destroyed in the 2003 Iraq war. It maintains a large research staff, a programme of lectures and occasional conferences, and publishes the oldest interdisciplinary journal on the Gulf, the Majallat al-Khalīj al-ʿArabī [Arab Gulf Journal], launched in 1973 and now in its 47th year.Footnote45 The timing of the centre’s establishment suggests that it was in recognition of the rising importance of the Arab states of the Gulf due to their new-found oil wealth.

The second centre to be established in 1974 was the Documents and Research Department at the Amiri Diwan in Qatar, founded by the Amir, Shaikh Khalifa Al Thani, as a de facto national archive to collect and preserve historical documents on Qatar, and to publish books on Qatari history –– beginning with an Arabic translation of John Lorimer’s Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, ‘Oman, and Central Arabia (1908, 1915) in 1975. The department was also given responsibility to review and approve histories of Qatar submitted for publication in the country but, in practice, it has rarely approved such books, preventing Qatari scholars from publishing in their own country.

Finally, in Aden in 1974, the South Yemeni government established the Yemeni Center for Cultural Research, Archaeology, and Museums to document and preserve the history and heritage of the country.

Another major development was the establishment of ongoing French archaeological missions in the Arabian Peninsula –– in Yemen (1972), Qatar (1976), the UAE (1977), Bahrain (1977), and Kuwait (1983) –– funded, not by oil, but by France’s Ministère des Affaires Étrangères as part of its strategy of cultural diplomacy. Annual funding applications for these missions are vetted by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in Paris, which submits its recommendations to the Ministère des Affaires Étrangères. The missions form part of a global network of 70 such missions around the world supported by the French government. They, along with the Danish archaeological expeditions and a growing number of British expeditions (most led by Beatrice de Cardi) and Iraqi expeditions,Footnote46 contributed indirectly to the launch of a number of government-run archaeology journals in the Arabian Peninsula:

Atlal: Journal of Saudi Arabian Archaeology (Saudi Ministry of Antiquities and Museums, 1976–present)

Archéologie aux Emirats Arabes Unis / Archaeology in the United Arab Emirates (Department of Archaeology and Tourism in Al-Ain, 1976–89)

Raydān: revue des antiquités et de l’épigraphie du Yémen antique / Journal of Ancient Yemeni Antiquities and Epigraphy (Yemeni Center for Cultural Research, Archaeology, and Museums, 1977–94; Yemeni Ministry of Culture with Centre Français d’Études Yéménites, 2013)

Arrayan (Qatar National Museum, 1977–85)

Outside of the region itself, the first Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies societies were also archaeological and historical in focus. The first was the Bahrain Society in London, formed in 1965 to promote friendship and understanding between Britons and Bahrainis, but with a strong interest in the archaeological discoveries of Geoffrey Bibby. The society runs an annual lecture series on Bahrain and organises social and cultural events. One of its founding members was Michael Rice, a museum consultant and amateur archaeological historian who helped establish the first national museums in Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Oman.Footnote47 Next was the Arabian Society, formed in London in October 1968 by John Dayton, Peter Parr, and Gerald Lankester Harding at the Institute of Archaeology, University of London. Established as a study group to convene a seminar series on archaeological and historical research on the Arabian Peninsula, it soon evolved into an annual conference series. Two founding members were Robert Serjeant, Director of the Middle East Centre and Chair of Arabic at the University of Cambridge, and Robin Bidwell, a Gulf historian and the Centre’s Secretary, who, together, would later found Arabian Studies in 1974.Footnote48 The first Arabian Society conference was convened in June 1969 by Serjeant and Bidwell at the Middle East Centre in Cambridge. In 1970, the Arabian Society renamed itself the Seminar for Arabian Studies, which has convened its annual conference by that name ever since, focused primarily on archaeology, but including other humanities subjects like history. Since 1971, the conference proceedings have been published by Archaeopress as the Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies.Footnote49

In March 1969, in the wake of the British government’s announcement the previous year that it would be withdrawing Britain’s military forces and protection from eastern Arabia, the Middle East centres at Oxford and the School of Oriental and African Studies in London organised the world’s first international interdisciplinary conference on the Arabian Peninsula covering both the humanities and social sciences. This resulted in the afore-mentioned The Arabian Peninsula: Society and Politics (1972) edited by Derek Hopwood, which was the world’s first interdisciplinary humanities/social science book on the Arabian Peninsula.Footnote50

In 1973, a member of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Richard Barnett of the British Museum (quoted above), founded the Committee for Arabian and Gulf Studies in London to promote and secure funding for British archaeology in eastern Arabia, which had, so far, been dominated by the Danes. Peter Parr explains how the origins of the committee

can ultimately be traced back to March 1970 and the meeting in Bahrain of the Third International Conference on Asian Archaeology. At the conclusion of this, a small group of us were invited to visit the Emiri Documentation Centre in Abu Dhabi, and it was during this visit that disappointment was expressed by some of the UK participants that there was no British involvement in the exciting archaeological activity in the Gulf states about which we had been hearing at the conference. My recollection is that it was Richard Barnett who was most vocal in his insistence that something should be done to rectify this, and it was certainly he who sometime afterwards set up a small ad hoc committee to discuss appropriate action.Footnote51

By 1974, there was sufficient interest in, and scholars working on, the Arabian Peninsula to support an interdisciplinary area studies journal. Thus, Robert Serjeant and Robin Bidwell at the Middle East Centre in Cambridge founded Arabian Studies (1974–90) and later New Arabian Studies (1994–2004), which the Journal of Arabian Studies follows in the footsteps of.Footnote53 In their introduction to the first issue, they explain how the modern evolution of Arabian Peninsula Studies was a natural outcome of the post-war development of Middle Eastern Studies and Area Studies more broadly, and argue it is better to study a region as a whole than from a single discipline:

In practice, it proves impossible for an individual research worker to confine himself within the restricted range of a single discipline –– this becomes ever more patently obvious in dealing with the Arabian Peninsula. … .

The Arabian Peninsula with its immediate confines constitutes a coherent whole appropriate to area study, within which there is a unity, yet much diversity. The extent to which interest in it has expanded is manifest in the great growth of writing on it during the last two decades [1950s–60s]. For these reasons, the moment is opportune to establish Arabian Studies as a multi-disciplinary journal.Footnote54

However, Serjeant and Bidwell restricted the journal to the humanities on the grounds that it was necessary to exclude “immediately contemporary politics on live contested issues”.Footnote55 They never stated the real reason for this, but it may have been due to possible anonymous financial support from the Amir of Bahrain.Footnote56 They published Arabian Studies on an annual, later semiannual, basis for eight issues from 1974 to 1990, before moving it to the Centre for Arab Gulf Studies at the University of Exeter, where they published it under the title of New Arabian Studies with the University of Exeter Press. NAS continued on an annual, later semiannual, basis for six issues during 1994–2004. The reason for the move was the need to find a new publisher and to pass the baton to the next generation. G. Rex Smith, Professor of Arabic at the University of Manchester, who began his career at Cambridge’s Middle East Centre under Serjeant and Bidwell, joined as the third editor of New Arabian Studies 1 (1994) together with two Exeter University-based “production editors”: Brian Pridham (then Director of the Centre for Arab Gulf Studies) and Jack Smart (Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies) who, like Smith, had previously taught Arabic at Cambridge. Serjeant passed away during the production of the first issue, while Bidwell passed away during the production of the second (1995). Thereafter, the journal’s generational change and transfer to Exeter was complete.Footnote57 In 1997, the Ruler of Sharjah, Shaikh Sultan Al-Qasimi, began funding the journal’s production.Footnote58 The last issue of New Arabian Studies appeared in 2004, after which the editors, who had all retired, chose to retire the journal as well.Footnote59 After a hiatus of seven years, the (now renamed) Centre for Gulf Studies relaunched the journal as the Journal of Arabian Studies in 2011, the story of which is told in Section 4 below.

In 1975, Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies as an interdisciplinary field, encompassing both the humanities and social sciences, took another step forward with Kuwait University’s launch of its bilingual Journal of the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, now in its 45th year. In Oman, the Ministry of Heritage and Culture established its (eventually) bilingual Journal of Oman Studies, which publishes articles on Oman’s cultural and natural heritage. In Saudi Arabia, the History Department at King Saud University in Riyadh convened the first International Symposium for Studies of the History of the Arabian Peninsula. It has convened periodic symposia ever since, most recently the ninth in 2018.

Finally, in 1976, the Anglo-Omani Society was founded in London to promote friendship between the two countries and to advance (mainly historical and cultural) knowledge about Oman in Britain through an annual lecture series. It was a logical extension of the Sultan’s Armed Forces Association, founded in London in 1968, whose role was more limited with membership restricted to veterans.

3.2 The development into a global, interdisciplinary field

The development of Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies into a global interdisciplinary field arguably began in 1978. In March that year, M.S. Agwani at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in New Delhi established the Gulf Studies Programme at the Centre for West Asian Studies. The programme consists of a research team, lectures, conferences, publications, and graduate courses (for the MPhil and PhD in West Asian Studies) –– especially during the tenure of its longest-serving Director, A.K. Pasha, who is a member of JAS’s Editorial Board. In Yemen the same year, the American Institute for Yemeni Studies (AIYS) was founded in Ṣanʿāʾ. The AIYS is a consortium of institutions of higher education promoting scholarly research on Yemen (primarily in the humanities and social sciences), as well as scholarly exchange between Yemen and the USA. Its office in Ṣanʿāʾ was opened in 1978 under the aegis of the Yemen Center for Studies and Research, mentioned above. The establishment of the AIYS was a turning point for American researchers working on the country. Over the past 42 years, the AIYS has published 19 books in its monograph series (1981–2009) and a newsletter (1979–2009), developed an excellent research library on Yemen, and hosted hundreds of American and Yemeni researchers through its visiting fellowship program. Its current President, Daniel Varisco, is a member of JAS’s Editorial Board. In Bahrain the same year, the then Crown Prince, Shaikh Hamad Al Khalifa, established the Historical Documents Centre at his Court in Riffa to document the history of the country.

In February 1979, Mohamed Shaban at the University of Exeter established the Centre for Arab Gulf Studies: the first and, for long, the most important Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies centre in the Western world.Footnote60 The centre’s Deputy Director and intellectual lead, Tim Niblock, who later became the first member of JAS’s Editorial Board, explained that the centre was

intended to foster research into the society, politics, economics, and history of the Arab Gulf region. The area covered by the “Arab Gulf” is taken to be the Arabian Peninsula and Iraq; there is a peripheral interest in Iran. The rationale for taking the Arab Gulf as an area for separate study is that this area is evidently of crucial international importance; that the social, economic and political problems facing the peoples of the area are complex –– and distinct from the problems facing peoples in most other Middle Eastern states; and that a disturbingly small amount of research effort is currently being directed towards the area. Even in centres devoted to Middle Eastern Studies, the Arab Gulf area seems to have attracted only limited attention.Footnote61

Also in 1979, the Qatari scholar Ali Khalifa Al-Kuwari founded the Gulf Development Forum, an annual symposium for GCC intellectuals to discuss development issues facing the GCC states. Membership is granted by invitation only. The first symposium was held in Abu Dhabi in December 1979. From 1994, it began publishing the proceedings of its annual meeting (in Arabic), which are available on its website. In 2009, the Forum began publishing articles on development issues facing the GCC states on its website.

In 1981, the then Crown Prince of Bahrain, Shaikh Hamad Al Khalifa, established the Bahrain Centre for Studies and Research to conduct research and surveys and convene conferences on policy-related matters of concern to Bahrain. The centre operated for 29 years, until it was closed by royal decree in 2010. In Riyadh, the Archaeology Department at King Saud University established the Saudi Society for Archaeological Studies to promote archaeology in the kingdom.

In the UK, Bill Charlton and May Ziwar-Daftari launched the short-lived Arab Gulf Journal, published in London by MD Research and Services Ltd (1981–86). The journal focused on contemporary economic issues in the GCC states and was aimed at a readership beyond academia. Its advisory board consisted of three British academics, the Managing Director of Qatar Petroleum, and the President of the Arab Monetary Fund.Footnote63

In 1982, a major French research centre was established in Ṣanʿāʾ: the Centre Français d’Études Yéménites (CFEY), the French equivalent to the AIYS, which hosted French archaeological missions and social scientists working on North Yemen and, after Yemeni unification in 1990, South Yemen as well. During 1993–2013, CFEY convened a programme of lectures and conferences, and published an annual journal called Chroniques yéménites [Yemeni Chronicles].

In 1983, two years after the birth of the GCC, it established the Arab Gulf States Folklore Centre in Qatar. The centre was housed in a large complex of five buildings in Doha, with a research department, research library, archive, and lecture theatre. The centre collected and documented all aspects of Arab folklore in the Gulf region, on which topic it convened seminars, workshops, and conferences, and published books and a quarterly journal, Al-Maʾ thūrāt al-sha ʿbīya [Journal of Popular Heritage], launched in 1986.Footnote64 The centre closed around 2004, but the Qatari Ministry of Culture continued publishing the journal until 2016.

Also in 1983, the Historical Documents Centre in Bahrain launched Al-Watheeka / The Document, a bilingual half-yearly journal dedicated to the history and heritage of Bahrain and the Gulf. In Riyadh, the King Faisal Foundation opened the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies to document Saudi and Islamic history, with a focus on the life and legacy of Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (1906–75). The Center began as an archive, but, in 1999, it established a research library and a visiting fellowship programme, and expanded its focus on Saudi and Islamic history to encompass Gulf Studies and Islamic Studies more broadly, convening regular talks, workshops, conferences, and exhibitions on these subjects.

In 1984, the Amir of Kuwait, Shaikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah, established the Historical Documents Center at the Amiri Diwan as a de facto national archive to collect and preserve historical records relating to the history of Kuwait, and to publish books on the subject. The centre was later expanded to include the Amiri Diwan Library. During the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait, Saddam Hussein seized the centre’s entire collection and transported it to Baghdad. The documents have yet to be returned.Footnote65 The centre was originally housed in the Seif Palace complex but, as of 2016, it is housed at the Shaikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Cultural Center complex.

In 1985, Omar Said Al-Hassan established the Gulf Centre for Strategic Studies in London, a semi-independent think tank funded by donations from the GCC governments that convened seminars and occasional conferences, and ran an active publication series of books and papers. It operated local branches in Bahrain, the UAE, and Egypt. The centre ceased operations in 2013, although a number of books by Al-Hassan on Bahrain continued to be published under its name.

In 1986, the Ruler of Ras al-Khaimah established the Studies and Documentation Center to collect historical documents and books on Ras al-Khaimah, publish books on Emirati history, and convene a periodic conference. The centre is housed in the Ras al-Khaimah National Museum (opened in 1987). The same year, the Saudi-British Society was established in London, which runs an annual lecture series on Saudi Arabia and organises social and cultural events.

In 1987, the Committee for Arabian and Gulf Studies in London renamed itself the Society for Arabian Studies and expanded its focus to encompass history and culture, although archaeology retained pride of place. The society began convening an annual lecture series on the Arabian Peninsula, which one of JAS’s editors, James Onley, managed during 2009–11. The society, the Seminar for Arabian Studies, and the Centre for Arab Gulf Studies in Exeter together would be the main focal points for Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies in the UK until the turn of the century.

In 1988, members of the History Department at King Saud University in Riyadh founded the Saudi Historical Society to replace the Archaeological Historical Society (founded in 1970), which had been absorbed by the Department of Antiquities and Museums, Ministry of Education in the early 1980s. The society convenes an annual conference and would later launch its own journal and book series. The following year, King Fahd of Saudi Arabia established the National Center for Archives and Records at his court in Riyadh to collect and preserve historical documents relating to the kingdom’s history and heritage.

In Dubai in 1989, Juma Al-Majid founded the Juma Al-Majid Center for Culture and Heritage. The centre has a research library and archive dedicated to UAE and Gulf history and culture, a book series launched in 1990, and a journal, Āfāq al-thaqāfiyya wa-al-turāth [Horizons of Culture and Heritage] launched in 1993, dedicated to the heritage of the UAE and the wider Arab and Islamic worlds. The same year, UAE University in Al-Ain established the History and Folklore Research Center to document, preserve, and research the history and folklore of the UAE.Footnote66 The centre ceased activities in the mid-1990s.

Also in 1989, the independent Scientific Research and Middle East Strategic Studies Center was established in Tehran, with a Persian Gulf Studies department and Saudi Arabia Studies department –– the first research institution in Iran to focus on the Arabian Peninsula. These departments hold public talks and conferences, and publish frequent articles on the GCC states and Yemen in the centre’s four Middle East Studies journals.

In 1990, a group of American scholars working on the Gulf established the Society for Gulf Arab Studies (SGAS). This was the first attempt to create a global Gulf Studies network and only the third American academic organisation on the Arabian Peninsula to be established after the American Foundation for the Study of Man in 1949 and the American Institute for Yemeni Studies in 1978. SGAS became an affiliate of MESA and held its AGM at the annual MESA conference. It published a newsletter and awarded a PhD dissertation prize. But with Gulf Studies still lacking critical mass in the 1990s, attendance at the society’s AGM remained small, and its activities were limited. The society eventually ran out of steam by the late 1990s and was disbanded in 2000.

Another development in 1990 was the foundation by Daniel Potts (another JAS Editorial Board member) of Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, the leading international journal in its field, now in its 30th year.

Finally, 1990 saw the establishment of the Bahrain-British Foundation (BBF) by Michael Rice and Yousif Al-Shirawi under the auspices of the Bahraini and British governments to fund a full academic year of postgraduate research or pre-vocational training for one Bahraini and one British university student in each other’s country.Footnote67 British BBF awardees were typically PhD students working on Bahrain, including two members of JAS’s editorial team: Robert Carter (JAS Editorial Board) in 1997–8 and James Onley (JAS Editor) in 1998–9. The BBF closed in 2005 after Al-Shirawi passed away and Rice retired.

In 1991, following the liberation of Kuwait, the American diplomat Nathanial Howell established the Arabian Peninsula and Gulf Studies Program (APAG) at the University of Virginia, which organises a lecture series, occasional conferences, and hosts visiting scholars. APAG was the first academic programme on the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula in the USA, building on the Gulf courses taught by Rouhollah Ramazani at the university in the 1950s–90s. Today the programme is led today by Fahad Bishara, the Rouhollah Ramazani Assistant Professor of Arabian Peninsula and Gulf Studies and a former JAS Book Review Editor.

In Yemen the same year, following the unification of the country, the government in Ṣanʿāʾ founded the National Center for Archives (later renamed the National Center for Documentation) to document the history and heritage of Yemen.

In 1992, a year after the liberation of Kuwait, the Center for Research and Studies on Kuwait was established to document Kuwait’s history. It started as an archive and research library, but quickly developed a programme of talks, conferences, and exhibitions, as well as a book series on Kuwaiti history, including both primary source material (sea captains’ diaries, memoirs, oral histories) and scholarly studies. In the UAE the same year, the Abu Dhabi Islands Archaeological Survey (ADIAS) was established by Shaikh Zayed Al Nahyan, the Ruler of Abu Dhabi and President of the UAE, to survey, record, and excavate archaeological sites on the coast and islands of Abu Dhabi, which was later extended to the interior. ADIAS convened public talks and conferences, and published books, articles, and a newsletter. In 2005, it was absorbed into the Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage (ADACH).

The next major step towards the development of a global Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies community occurred in 1993 when Gary Sick (also a member of JAS’s Editorial Board) and Lawrence Potter at the Middle East Institute, Columbia University, launched the Gulf/2000 project. Gulf/2000 provides an invaluable email forum and archive for its members to exchange information and expertise on Gulf issues and events on a daily basis. It also convenes periodic conferences, publishes a highly regarded edited volume series based on these conferences, and maintains the Gulf/2000 website and e-library.

The same year, the British-Yemen Society was founded in London to advance friendship between the two countries and promote knowledge about Yemen’s history, geography, economy, and culture in Britain. It publishes the Journal of the British-Yemen Society, now in its 27th year, convenes an annual lecture series, and organised group tours to Yemen before the start of the Yemen civil war in late 2014.

In the UAE in 1993, Shaikh Zayed established the Emirates Heritage Club to promote awareness and appreciation of Emirati heritage through seminars, conferences, exhibitions, and a book series, as well as an extensive programme of social activities and festivals for Emiratis. It maintains a network of heritage activity centres around Abu Dhabi. In 1997, the club became an independent authority of the Abu Dhabi government.

In 1994, a team of archaeologists at the School of Oriental and African Studies, led by Geoffrey King, established the British Archaeological Mission to Yemen (BAMY) to screen and obtain Yemeni government approval for all British research carried out in Yemen in the fields of archaeology, history, epigraphy, numismatics, pre-Islamic and Islamic architecture and all manuscript and museum-based studies. Before the Yemen civil war, the applications it approved and obtained permits for became official BAMY projects. BAMY operates under the auspices of the Society for Arabian Studies (now the International Association for the Study of Arabia).

The same year, Kuwait University established its Centre for Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, building on the momentum generated by its Journal of the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, launched in 1975. In Bahrain, the Ministry of Culture launched a quarterly journal, Al-Baḥrain al-thaqāfiyya [Bahrain Culture], a scholarly magazine dedicated to Bahraini culture, heritage, and history. In the UAE, the Abu Dhabi government established the Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research (ECSSR), with a research library, research department, lecture series, and conference series. In 1995, the ECSSR launched its Occasional Papers Series, Emirates Lecture Series, Strategic Studies Series, and a book series.

Also in 1995, Aden University established the Al-Dhofari Center for Yemeni Research and Studies, with a research department and research library, lecture and conference series, and a journal, Majallat al-Yaman [Yemen Journal].

In 1996, Prince Sultan bin Salman Al Saud founded the Al-Turath Foundation to preserve the national heritage of Saudi Arabia, focusing initially on architectural heritage, but later expanding to national heritage more broadly. The foundation collects historical photographs and was instrumental in the establishment of the National Archive for Historical Photographs at King Fahad National Library in 1997. It publishes books on Saudi history and heritage, organises lectures and conferences, and restores historical buildings, especially mosques. It was the first organisation devoted chiefly to the preservation of the Arabian Peninsula’s architectural heritage, and would be followed by others in Bahrain (2002), the UAE (2003), Saudi Arabia (2010), the UK (2010), and Qatar (2019).

1996 also saw the Society for Arabian Studies launch its Bulletin of the Society for Arabian Studies (1996–2011), later renamed the Bulletin of the British Foundation for the Study of Arabia (2012–18) and, later again, the Bulletin of the International Association for the Study of Arabia (2019–present).

In 1997, the GCC established the Association of History and Archaeology in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries, headquartered in Riyadh, to promote the history and archaeology of the GCC states, holding conferences and seminars. The same year, the Qatari historian, Shaikh Hassan bin Muhammad Al Thani, established his own research centre and library in Doha: the Hassan Bin Mohammed Center for Historical Studies, which conducts and funds research on Qatari and Gulf history, and convenes lectures and symposia on these topics. The centre housed a large rare book and manuscript collection on the Gulf and wider Middle East, which now forms part of the Qatar National Library’s “Heritage Library”. Today the centre houses a research library on Gulf history and a lecture theatre.

Finally, in December 1998, the Emirates Heritage Club established the Zayed Center for Heritage and History in Al-Ain (inaugurated in March 1999) to document, record, research, and promote Emirati history and heritage, especially archaeology, folklore, and oral history. It has a research department, archive (with a major collection of Ottoman and British records, oral histories, films/videos, manuscripts, journals, and newspapers), and research library. It convenes lectures, seminars, and conferences, and published a book series and a monthly magazine, Turāth [Heritage].Footnote68 Its first Director was Hasan Al-Naboodah (1999–2006), an Associate Professor of History at UAE University and a member of JAS’s Editorial Board. In 2009, the centre relocated to Abu Dhabi city, where it was renamed the Zayed Center for Studies and Research.

3.3 Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies in the 21st century

By the end of the 20th century, then, Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies had developed into a respectable, although still relatively small, field within wider Middle Eastern Studies, while it was still largely disconnected from Indian Ocean Studies. The first two decades of the 21st century were to change that, as a dramatic growth in the number of societies, centres, publication series, activities, and graduate programmes plunged Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies into the mainstream, as shown in .

Table I: The development of Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies since 1949

As can be seen, more societies, centres, projects, programs, publication series, conference series, lecture series, and graduate programmes were established in the first two decades of the 21st century than the last five decades of the 20th century. It was this growth that would eventually give birth to JAS in 2011.

This new phase began in 2000 with the establishment of the Gulf Research Center (GRC) in Dubai by Abdulaziz Sager. The GRC quickly became a globally recognised centre for Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, publishing an impressive number of books and articles on social science topics, and convening the annual Gulf Research Meeting (GRM) at Cambridge, where several workshops each year resulted in several edited volumes published in the GRC’s Gulf Studies book series, which, since 2012, has been published by Gerlach Press in Berlin, one of the most prolific publishers on the region. These annual GRMs have also provided an important opportunity for Gulf Studies researchers from the West, the Gulf, India, East Asia, Australia, and elsewhere to meet and collaborate, and have become a major pathway into Gulf Studies for new researchers in the social sciences.

In Ṣanʿāʾ the same year, Zaid bin Ali Al-Wazir founded the Yemen Heritage and Research Center, which published a bilingual quarterly journal called Al-Masār [The Path] during 2000–16. In Riyadh, the Saudi Historical Society launched its own journal, Majallat al-jamʿīyah al-tārīkhīyah al-Saʿūdiyah [Journal of the Saudi Historical Society], and book series.

In 2001–02, the Ruler of Sharjah, Shaikh Sultan Al-Qasimi (himself a noted scholar of Gulf history), funded two new purpose-built homes for Middle East Studies at the universities of Exeter and Durham, which would also house their Gulf Studies staff, students, programmes, and events: the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies (IAIS) at Exeter, founded in 1999 by joining together the Center for Gulf Studies and Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies, with Tim Niblock as Director; and the Institute for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (IMEIS) at Durham, which had been founded in 1962. Shaikh Sultan also endowed a Chair of Gulf Studies at Exeter, first held by Tim Niblock, during 1999–2007, and then by one of JAS’s editors, Gerd Nonneman, during 2007–11. A decade later, Durham would establish the Sheikh Nasser Al-Sabah Programme, named after its benefactor, which funds a Gulf Studies chair and a PhD studentship, and runs a series of workshops and occasional conferences on the Gulf, a series of occasional papers and the Al-Sabah monograph series (Routledge, 2013–15). A crucial aspect of these initiatives at Exeter and Durham has been the firewall between their funders and their academic activities –– essential for the academic integrity of scholarly research and teaching on the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula.

Elsewhere in 2001, the University of Calicut in India established the Kunjali Marakkar Centre for West Asian Studies, with a lecture series and occasional conferences on West Asia (focusing mainly on the Indian Ocean). The same year, the Centre Français d’Études Yéménites (CFEY) in Ṣanʿāʾ changed its name to the Centre Français d’Archéologie et de Sciences Sociales (CEFAS) and expanded its scope to the entire Arabian Peninsula. Since 2002, it has been sponsored by France’s Ministère des Affaires Étrangères and the CNRS, and, since 2013, it has formed part of a global network of regional studies centres and country-based archaeological missions supported by the French government. During 2006–14, it also published the book series Chroniques du manuscrit au Yémen [Manuscript Chronicles in Yemen]. In 2013, CEFAS broadened the scope of Chroniques yéménites (published in French since 1993) to encompass the whole Arabian Peninsula and renamed it Arabian Humanities, which publishes articles in French, English, and Arabic. In 2016, CEFAS opened a second office in Kuwait after the start of the Yemen war and, in 2019, a third office in Abu Dhabi. Like its London-based cousins, CEFAS organises a series of lectures, conferences, and publications on the Arabian Peninsula.

In 2002, the Bahraini historian Shaikha Mai Al Khalifa founded the Shaikh Ebrahim bin Mohammed Al Khalifa Center for Culture and Research in Muharraq to promote and preserve Bahraini heritage, especially the architectural heritage of Muharraq. The centre is housed in a restored historical building in Muharraq (opened 2003) equipped with a lecture theatre, small library, and museum displays. It convenes a popular lecture series on Bahraini heritage and culture, curates exhibitions, publishes books (since 2008), and restores historical buildings in Bahrain.

Also in 2002, the Society for Arabian Studies in London convened the first of its Biennial Conference series under the theme of the Red Sea. The next two conferences continued this theme, and became known as Red Sea II (2004) and Red Sea III (2006). Subsequently, responsibility for these conferences has been taken over by other academic institutions: Red Sea IV (2008) was convened by the Centre for Maritime Archaeology at University of Southampton; Red Sea V (2010) by the MARES Project at the University of Exeter; Red Sea VI (2013) by the Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities at Tabuk University in Saudi Arabia; Red Sea VII (2015) by the Asia, Africa and Mediterranean Department at the University of Naples “L’Orientale”; Red Sea VIII (2017) by the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw; and Red Sea IX (2019) by the ERC-funded Desert Networks Project at the CNRS research centre for Histoire et Sources des Mondes Antiques (HiSoMA) at the Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée in Lyon in collaboration with Artois University.

In 2003, Gilles Kepel at the Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris (Sciences Po), with support from France’s Ministère des Affaires Étrangères, launched the EuroGolfe Network of scholars to facilitate new research and PhDs on the GCC states at Sciences Po on topics of interest to the public and private sectors, and to foster collaboration and dialogue between Europe (mainly France) and the GCC states on the challenges facing the Gulf and the wider “EuroGolfe region” (Europe and West Asia). The network met at the EuroGolfe Forum for Human Development, a series of conferences convened in Abu Dhabi (2004), Menton (2005), Riyadh (2007), and Venice (2008). EuroGolfe came to an end in late 2010 when funding for it dried up in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. A legacy of the EuroGolfe Network is the four GCC-related books published during 2011–17 in the “Proche Orient” (Near East) book series of Presses Universitaires de France edited by Gilles Kepel, who is also a member of JAS’s Editorial Board.

Also in 2003, the UAE government established the Architectural Heritage Society to document, preserve, and promote the architectural and urban heritage of the country. It organises public lectures, seminars, conferences, and exhibitions, and is headquartered in a historical building in the Al-Bastakiya (later renamed the Al-Fahidi) district of Dubai close to the Dubai Municipality’s Architectural Heritage Department, which seems to have initiated the Society.