Abstract

How are nationalism and national identity shifting in Qatar as a result of the regional crisis? This study explores whether this moment of geopolitical fluidity allows for changes in sociocultural behavior and norms among Qatari citizens. Specifically, this research uses the case study of the newly opened National Museum of Qatar to examine a state-crafted narrative of national identity and society’s response to this narrative. Our original fieldwork highlights the museum’s combination of desert and sea lifestyles to create a “unity” narrative of Qatari national identity, and explores the mixed reactions of citizens who feel varying levels of representation and inclusion in this narrative. This study concludes with a critical analysis of the malleability of national identity during times of political upheaval.

1 Introduction

Despite disagreements and conflicts over the years,Footnote1 the Gulf Arab monarchies –– Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) –– have successfully collaborated on issues related to mutual security and economic interests through the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).Footnote2 Yet the regional crisis (5 June 2017 to 5 January 2021), during which regional neighbors Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE severed relations with Qatar, was a severe disruption to the political, economic, and social relationships between these states.Footnote3

How are nationalism and national identity shifting in Qatar as a result of the regional crisis? The scale and scope of the conflict have reduced the salience of khalījī identity –– the social recognition among Gulf citizens that they share heritage, culture, religion, and kinship ties across national boundaries –– and opened the door for increased expression of state-specific nationalism.Footnote4 How are Qataris –– both at the state and societal levels –– reacting to this moment of sociopolitical flux and reimagining their national identity?

This study explores, in a broad sense, the ways in which a moment of geopolitical fluidity allows for changes in sociocultural behavior and norms among Qatari citizens. Specifically, this research uses the case study of the newly opened National Museum of Qatar (NMoQ) to examine a state-crafted narrative of national identity as well as society’s response to this narrative. The NMoQ is overseen by Qatar Museums, an entity headed by the sister of the current Amir, and supervised directly by the Amiri Diwan (the seat of Qatari government); as such, it can be studied as a state-approved narrative of Qatari history and culture.Footnote5 Opened in March 2019, after years of delays, the national museum presents a “unified” national identity of the Qatari people through a set of galleries titled “the people of Qatar.” How is the museum portraying this unified national identity, and how are Qatari citizens perceiving and responding to this narrative? Using original fieldwork conducted in Qatar –– multiple museum visits by the authors and twenty-four interviews after the opening of the museum (March–May, and September 2019) –– this study provides insight into the malleability of national identity during times of political upheaval.

2 Qatar and its demographic challenges

For decades, the Gulf Arab monarchies have been investing their hydrocarbon wealth in ways meant to diversify and strengthen their sources of domestic political legitimacy.Footnote6 Qatar is no exception to this rule; the creation of a sense of nationalism and national identity, separate from wealth distribution, has been a central legitimacy strategy of the Qatari state for decades.Footnote7 In particular, Qatar (in line with its neighboring monarchies) has utilized museums to propagate official state-crafted narratives of national identity and heritage.Footnote8

To an outside observer, Qatar’s decision to invest in nation-building narratives may appear confusing. The common analytical framework for understanding politics in the hydrocarbon-rich Arab monarchies of the Gulf has been rentier theory, which focuses on the state’s control of natural resource wealth and subsequent distribution of this wealth to its citizens.Footnote9 Wealth distribution along with other mechanisms of economic control are theorized to result in both economic satisfaction and subsequent political stability, if not outright loyalty. According to rentier theory, the economic relationship between state and citizen alleviates the state from the need to cultivate a sense of nationalism; as Luciani writes, “An allocation state does not need to refer to a national myth and, as a matter of fact, will usually avoid doing so”.Footnote10

This conception of a solely pocketbook relationship between rentier state and society has been challenged by research, both qualitative and quantitative.Footnote11 These scholars demonstrate that inequality in the allocative process –– whether real or perceived –– creates dissatisfaction with these state-distributed benefits. The upshot of these revisions to the rentier framework is simple: the Gulf Arab monarchies cannot rely on economic allocation alone to ensure their political legitimacy.

In Qatar, nation-building narratives do more than address the inherent inequalities and destabilizing effects of the distributive system. These narratives are also aimed at smoothing the demographic divisions within Qatari society. Qatari citizens are generally estimated to comprise only about 10% of the country’s total population.Footnote12 Even as the presence of foreigners is recognized as an important part of economic and national development by the Qatar National Vision 2030,Footnote13 this demographic imbalance between Qatari citizens and expatriate residents is of grave concern to the Qatari community.Footnote14 The feeling of being a minority in one’s own country results in a shared commitment, by both state and society, to preserve and celebrate Qatari culture, heritage, history, and identity. Yet the definition of “Qatari culture, heritage, history, and identity” remains an open question for Qataris themselves, who are much more multifaceted and diverse than commonly perceived.Footnote15

Despite rentier wealth, Qatari society contains salient distinctions based on cultural heritage and geographic origin. First, Qataris define themselves by three cultural pasts that are related to the lifestyles of their ancestors: nomadic life in the desert (Bedouin, or badū), settled life on the coast (ḥaḍar), and a mix of the two marked by seasonal movement (semi-Bedouin/ḥaḍar).Footnote16 There is both historical and modern-day evidence of tensions between the distinct desert and sea communities.Footnote17 Second, as Alshawi and Gardner note, the peoples of the Arabian peninsula are characterized by their “extraordinary mobilities”, resulting in important geographic divisions –– whether one’s ancestors can be traced from the Arabian peninsula (specifically the Najd, or central Arabia), or from elsewhere, such as Bahrain, Yemen, other Arab countries of the Middle East, Persia, Africa, or South Asia.Footnote18 Geographic origin intersects with the desert and sea lifestyles –– to be considered fully Bedouin, Qataris must “trace their descent from the nomadic tribes in the Arabian Peninsula”, while those who settled on the coast (the ḥaḍar) could be of Arab or Persian heritage.Footnote19 Nagy explains that the term ʿajam refers to the “descendants of merchants and craftsmen who migrated to Qatar from Persia”.Footnote20 Yet another group, the hawila, claim Arab ancestry but had moved to live in Persia for a period of time before returning to Qatar.Footnote21 Many of these coastal merchants engaged in pearling, but not all of them; crafts, trading, and other businesses were also part of the coastal lifestyle. Likewise, descendants of enslaved Africans can still be found in Qatari society today, a particularly sensitive subject to discuss in public, according to research by Al-Mulla.Footnote22

These social stratifications are codified into the citizenship laws of Qatar, creating legal consequences for different tiers of society. Citizenship is often conflated with national identity, but the two are distinct concepts. While national identity may be ethnic or civic, and inclusive or exclusive,Footnote23 citizenship laws in the Gulf often officially sanction inequalities between citizens.Footnote24 Qatar’s 2005 Nationality Law divides citizens into two tiers, national (Article 1) and naturalized (Article 2), based on whether the family resided in Qatar before 1930.Footnote25 Al-Kuwari argues that the nationality law “paves the way for this transformation of citizens into inhabitants who enjoy none of their rights of citizenship. It does this by permanently depriving citizens who have acquired Qatari citizenship (about one third of all citizens) and their descendants of all political rights”.Footnote26 The two tiers of citizenship do indeed come with different political rights; naturalized citizens may have their citizenship revoked more easily (Articles 11–12) and are ineligible to be candidates or even vote for the legislative body, which in Qatar would mean the national Advisory (Shura) Council (Article 16). Further, the children of naturalized citizens retain this second-tier legal status –– as they can never become “national” citizens (Articles 1–2), these legal inequalities are passed down from generation to generation.

Why the date of 1930? In the early 1900s, Qatar’s economy was almost entirely based on the pearling industry.Footnote27 The collapse of the pearling trade in the 1920s occurred because of Japan’s introduction of cultured pearls, and it devastated the Qatari economy.Footnote28 Between one-third and one-half of the population of Qatar is estimated to have emigrated in the 1920s and 1930s due to the difficulty of finding enough food and work to survive.Footnote29 Among these emigrants are the hawila, who built businesses in Persia or elsewhere for several decades before returning to Qatar in the 1940s and 1950s when the economy began to improve, in large part due to oil exports. When they did return –– along with the ʿajam, who immigrated to Qatar from Persian origins at around the same time –– they were classified with second-tier citizenship, a legal division that has solidified social divisions among Qataris.Footnote30 Family-enforced restrictions on marriage choices are one of the most tangible modern consequences of this citizenship law.Footnote31 As well, the continually delayed Advisory Council elections –– promised since 2004 –– may be due to the politically sensitive fact that a significant percentage of the citizenry is currently ineligible to participate.Footnote32 In sum, the citizenship laws of Qatar reinforce societal divisions, with real consequences for social cohesion and political development in Qatar today.

3 Narratives of national identity in Qatar

These cultural and geographic divisions within Qatari society give increased importance to the propagation (and reception) of state-crafted narratives of Qatari identity and heritage. Museums have been a central part of Qatar’s nation-building efforts since the country’s formal independence in 1971. As Al-Mulla notes, within three months of his ascension to power, Amir Shaikh Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani (r. 1972–95) began archaeological excavations and project planning of the country’s first national museum.Footnote33 Establishing a state museum and collection was a deliberate effort to archive, protect, and represent Qatari cultural heritage and history at a time when there was no historical and cultural repository for the nation. The process, nonetheless, necessitated a political use of Qatar’s history and cultural materials in order to construct a narrative of nationalism.Footnote34

The original national museum, the Qatar National Museum (QNM), depicted the Qatari people as following one of two distinct cultural lifestyles –– either life on the coast (ḥaḍar) or life in the desert (badū).Footnote35 The QNM emphasized the distinct material culture of these two lifestyles by displaying each in a separate building in the original museum: coastal culture was displayed in the Old Amiri Palace and desert culture was displayed in the Museum of the State.Footnote36 We can understand this presentation as a direct message from the state of the preferred way, at the time, of presenting cultural identity in Qatar. Furthermore, this state-led presentation aligned with the popular understanding of heritage in Qatar. As Al-Malki notes, “The two dominant historical narratives of Qatar have always been the desert and the sea, recounting the histories of two people: the transient and the permanent, the nomads and the coastal”.Footnote37

However, since 2007, the Qatari state has been focused on a complete renovation and reconstruction of its national museum to align with an updated national narrative, one of a unified citizenry where coastal and desert lifestyles are combined to form a “dualistic lifestyle, in which Qataris moved back and forth between the desert and the coast depending on the seasons”.Footnote38 This focus on movement connects the lifestyle between the winter months, with herding and camping in the desert, and the summer months, when people settled on the coast and engaged in pearling, to create a “tribal modern” brand that unifies Qatari identity.Footnote39 As the head curator of this section of the museum explained in 2014, “We are Qatari people: We have our camels, but we also have our dhows [pearling boats] … . We need the people to know this. We were not always Bedouin only, or only part of the fishing villages. We were all together … . Part of the time we live here, part of the time we live there. We live the duality life”.Footnote40

Why is Qatar Museums now focusing on this single-identity, “unity” narrative, and what are the historical factors behind it? The answer to this question lies in the history of the formation of Qatar as a political community, which began in the 1860s–70s, during the era of Shaikh Jassim bin Muhammad Al Thani, considered the founder of Qatar. Mid-nineteenth century Qatar was a tribal society, with each tribe ruled independently by its own shaikh and with incidents of inter-tribal hostility. Yet, when Qatar was attacked by neighboring tribes, the Qatari tribes united under the leadership of Shaikh Muhammad Al Thani and his son Shaikh Jassim to defend their land.Footnote41 This unification, despite differences, was critical for the protection of Qatar from external threat. Over the decades since Shaikh Jassim’s unification of the tribes, Qatar was subjected to multiple attacks by regional tribes as well as imperial control by the Ottomans (1871–1915) and later the British (1916–71).Footnote42 Each time, tribal unification –– under the local leadership of the Al Thani –– was the primary defense of Qatar’s independence and sovereignty, thus forming a natural foundation of Qatari identity.

This theme of Qatari unity in the face of external threat took on additional salience following the outbreak of regional conflict in the Gulf in June 2017. The sudden severing of political, economic, and social ties between Qatar and Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE created disruption in the GCC as a functioning institution.Footnote43 It also disrupted Qatari citizens’ opinions of the GCC and reduced the salience of the transnational identity narrative of the Khalīj in favor of Qatari-specific forms of nationalism.Footnote44 In this rapidly fluctuating geopolitical moment, state-crafted narratives of unified nationalism in Qatar may find a particularly receptive local audience.

This history helps to explain why the modern presentation of Qatari identity has emphasized unification, an element that, without doubt, has played a tremendous role in the foundation of the state and particularly in its present moment of crisis. The final opening date of the new museum –– 27 March 2019, delayed from 17 December 2017 –– allowed Qatar Museums to take into consideration the Gulf crisis. As such, this study views the unity narrative unveiled in the spring 2019 museum opening as a top-down statement of Qatari national identity in a post-blockade world.

Al-Hammadi, however, notes that this narrative of unity exists “between imagination and reality”, and her work offers a number of important historical and cultural critiques.Footnote45 Most immediately, this narrative, which is based upon a presentation of the dualistic lifestyle, avoids acknowledgement of the existence of the ḥaḍar-only and badū-only communities within Qatari society. In a larger sense, such a focus could also lead to unintended social consequences for Qatari society. While the state’s earlier (1970s–90s) identity narratives highlighted the diversity of Qatari identity through museums and cultural organizations, Qatar is now shaping a new single-identity cultural policy that reflects only a partial recognition of the past. During the geopolitical crisis, there was a particular disconnect between the state propagating a limited and restricted identity and, at the same time, announcing its respect and appreciation of the diversity that comprises the nation’s population.Footnote46 Al-Hammadi concludes by wondering “how far such a presentation would be accepted and perceived by the Qatari public” and whether this dualistic identity narrative “might serve to increase discrimination in society”.Footnote47 These concerns infer that the state-crafted unity narrative may face an uphill battle for acceptance among the Qatari citizenry.

Al-Hammadi’s analysis reminds us that the people of Qatar are part of the creation and presentation of the national narrative. While cultural institutions and museums in Qatar are directly founded and supervised under the patronage of the state (through Qatar Museums), it is nevertheless important to recognize that the formation of the national culture and identity narrative comes from both state and societal input.Footnote48 The Qatari population is aware of the pressures to globalize and modernize as well as to protect and promote their national cultural identity.Footnote49 In this, Qatari state-society relations go beyond petro-dollars to tribal patriotism, where group and individual associations are important to the creation and presentation of the national identity narrative.Footnote50 In such a complex social environment, the narrative of Qatari identity should be seen as an inclusive process with multiple stakeholders; it is a challenging narrative to create and present, even for a rentier state.

4 “The people of Qatar” and the presentation of identity in the National Museum of Qatar

In this study, we focus on the second of three sections in the National Museum of Qatar (NMoQ): the set of galleries that comprise “the people of Qatar.” While the original national museum separately introduced each Qatari lifestyle, badū and ḥaḍar, along with their cultural materials,Footnote51 the new museum presents these identities as seamlessly combined, as if all Qatari people traveled seasonally between the sea and desert. Throughout the “people of Qatar” galleries, the museum presents the desert and sea lifestyles as parts of a common whole in several ways: through gallery wall texts, a technologized map of Qatar, selected oral histories, and a wall display along the staircase that connects the upper and lower galleries.

The wall texts that introduce each gallery of the “people of Qatar” exhibit convey a message of unity across the cultural lifestyles. The first gallery introduces the Qatari people with the following:

The people of Qatar moved freely between the land and the sea: herding and hunting, trading and pearling. The peninsula is also located at a crossroads of ancient trade routes stretching far to the east and west. … Qatari identity is rooted in this unique geography and history of the peninsula, true to its Arab heritage and the values of Islam while welcoming new influences and ideas.

The narrative moves on to the “life in al-barr (desert)” section. Here, the introductory text reads: “In Qatar’s autumn and winter months, people moved around al-barr, herding, hunting and trading. Al-barr, the desert, is a challenging land, yet people thrived here”. This text emphasizes that the desert was the home of the Qatari people in the fall and winter. This gallery leads naturally to the “life on the coast” gallery, whose introductory text notes that the sea was the home of Qataris for the summer months:

The sea has long been at the heart of life in Qatar: a way for people, goods and ideas to travel, and a rich source of food and natural resources. In early summer, with the start of the pearling season, the people moved to Qatar’s coastal cities. Merchants, craftsmen and scholars came here from across the region to live, trade and work. Overseas trade connected Qatar to networks that stretched as far as China, India and Europe. These relationships brought diverse cultural influences that enriched the vibrant, cosmopolitan communities of Qatar.

It is especially important to note that nowhere in the NMoQ, whether in the introductory texts or in any text panels and captions, are the terms ḥaḍar and badū (or Bedouin) used. The absence of these terms stands in sharp contrast to the QNM’s explicit recognition of these two separate lifestyles in Qatar, as previously discussed. That the NMoQ chose to erase these words from the national narrative demonstrates its emphasis on the seamless intersection of desert and sea lifestyles.

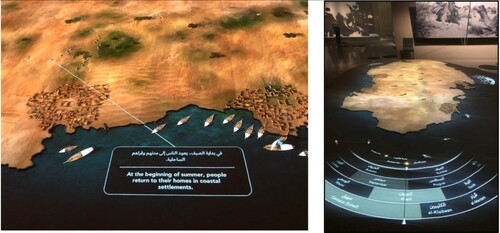

One of the first items displayed in the “people of Qatar” exhibit is a digitized map of Qatar, which demonstrates visually the yearly calendar and the Qatari process of seasonal movement between the sea and desert. As per , the map displays captions to explain the movement of desert caravans and pearling boats as the year progresses. For example, the map narrates, “At the beginning of summer, people return to their homes in coastal settlements”. Later, the map depicts pearling boats setting sail and then returning to the coast, followed by lines of people and animals heading out to the desert to camp and herd in the winter months. Again, this technologized map is part of the museum’s amalgamation of the unique characteristics of ḥaḍar and badū into one single identity.

Figure 1: The technologized map of Qatar, depicting the seasonal movement between desert and sea in the new National Museum of Qatar. Mitchell photographs, 4 April 2019 (left) and 23 April 2019 (right).

Selected oral histories are displayed to provide oral and visual explanations of this unified Qatari heritage. Eleven Qataris are depicted in the oral history section of the upper gallery (others give specific oral histories about pearling in the lower gallery). Two oral histories focus on the unity, blood ties, and social closeness of the Qatari people. The other nine discuss the movement of Qataris between the desert and the sea. Most of these oral histories adhere closely to the unity narrative, such as one explaining that “in the winter, people moved to the desert, in the summer they went to pearl-diving areas”.Footnote52 Another states, “Qataris are descendants of tribes who dived for pearls in the summer and spent the winter in the desert”.Footnote53 A third interview notes, “Qatar’s heritage … revolves around two points –– the sea and the desert”.Footnote54

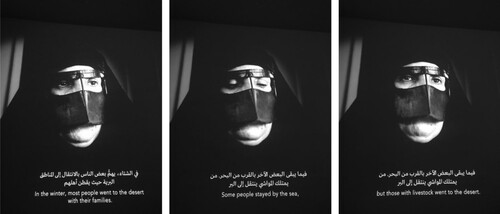

Analyzing the text of these oral histories, however, shows some contradiction to the narrative that all people of Qatar lived in this way. For example, one narrator explains that “most of the people of Qatar, perhaps 80%” traveled seasonally.Footnote55 This explanation means the other 20% did not adhere to the dualistic lifestyle. We find additional nuance to the national narrative in another oral history, which states, “In the winter, most people went to the desert with their families. Some people stayed by the sea, but those with livestock went to the desert”.Footnote56 See .

Figure 2: Oral history video stills in the “people of Qatar” exhibit, National Museum of Qatar. Mitchell photographs, 29 April 2019. Left image: A picture of a woman in a traditional scarf and face covering. The caption reads, “In the winter, most people went to the desert with their families.” Center image: A picture of a woman in a traditional scarf and face covering. The caption reads, “Some people stayed by the sea.” Right image: A picture of a woman in a traditional scarf and face covering. The caption reads, “But those with livestock went to the desert.”

The “life in the desert” and “life on the coast” galleries are connected by a staircase, which allows museum visitors to experience the physical sensation of movement as they walk down the stairs to the coastal gallery. The stairway’s wall is decorated with rectangular photographs that are meant to represent the two different lifestyles. The badū are depicted through various sadu weaving patterns, which were tent fabrics used in the desert. The ḥaḍar are represented through the large pieces of gold jewelry –– the badū traditionally used silver and the jewelry was smaller due to their nomadic movements –– and stone patterns of gypsum that decorated coastal houses. As shows, these cultural heritage photographs are intermixed, once again emphasizing to the audience the connection between desert and coastal lifestyles.

Figure 3: Wall decorations along the staircase connecting the “life in the desert” gallery to the “life on the coast” gallery, National Museum of Qatar. Mitchell photograph, 29 May 2019.

It is important to note that the beginning of the “people of Qatar” exhibit has artifacts related to trading networks, and the introductory text in this section’s galleries specifically refers to the importance of trade and its concurrent “diverse cultural influences that enriched the vibrant, cosmopolitan communities of Qatar”. However, the majority of the unity narrative is focused on life in the desert and life on the coast, specifically as it relates to pearling. In this sense, the new national narrative is about unifying the badū and ḥaḍar cultural heritages into a single identity.

5 Responses to the museum’s identity presentation

What do Qataris think of the new national identity narrative? Twenty-four in-person interviews with Qatari women were conducted between 31 March and 30 September 2019, in Arabic and English, through a mixture of random and snowball sampling. To avoid interviewer-respondent gender effects, our team of female researchers sought out only female interviewees.Footnote57 While we did not intentionally restrict the age range, our sample of Qatari women is youthful (ranging from ages 19 to 36), and as such provides context rather than generalizability to the entire population.

Expatriate residents, who make up about 88% of the population of Qatar,Footnote58 are an important part of political legitimacy strategies in the country, and residents’ expectations and responses are essential for understanding the impact of the narratives of the National Museum of Qatar.Footnote59 However, assessing expatriate responses to the unity narrative is beyond the scope of this study. This research focuses specifically on the responses of Qatari citizens to the reimagined national narrative of unity.

While we protect our interlocutors’ confidentiality and privacy through the use of pseudonyms and the deletion of any personally identifying information from their self-identifications and/or from identity markers gleaned from their interviews,Footnote60 we can ascertain that nine of them come from desert heritage (Dana, Maryam, Jawaher, Johara, Menna, Luna, Meem, Noor, and Layla), seven come from coastal heritage (Shaikha, Israa, Maha, Sara, Sabicha, Layal, and Fatima), and four assert that they are “mixed” in some way (Lulu, Khulood, Noora, and Moza). Lulu and Khulood explicitly identified themselves as mixed (badū and ḥaḍar), although Lulu noted “these labels are false” and she identifies “as a Qatari”.Footnote61 Khulood said that she would “rather identify [herself] as an individual”.Footnote62 Noora, a ḥaḍar, and Moza, a badū, both noted that they also identified with or were related to the other cultural lifestyle. Four interviewees (Natifa, Sahar, Ghalya, and Nawal) did not identify their cultural heritages. Although most did not self-identify their socioeconomic class, Dana noted that her family is from “a big and respected tribe in Qatar” with origins in the Najd (central Arabia).Footnote63 Several interviewees noted family ties to the ruling family or other established original tribes (Sabicha, Khulood, and Noora), and Shaikha’s repeated references to the depiction of “the shaikhs and the royal family” in the museum indicate that her family is a well-established and connected ḥaḍari family in Qatar as well.Footnote64 Several others indicated some level of middle-class status, including Noor, who explained that she is “not rich, not poor. Just normal”.Footnote65

How did our Qatari interviewees interpret the museum’s narrative of the “people of Qatar” galleries? Only four indicated explicit recognition of the “dualistic” identity narrative that all Qataris moved seasonally back and forth between the desert and sea, and they differed in their acceptance of this narrative. Three of them, despite identifying as one type of cultural heritage, noticed and appreciated the combination of the two lifestyles. Maryam, a badū, said:

I really liked that [the people of Qatar gallery] because it is expressing our culture. Here in Qatar, we do not have Bedouin as Bedouin and the ḥaḍar as ḥaḍar, because we are part of the same [people]. So, this is a peninsula –– we live in the desert, we go to the beach, we go back to the desert –– so there are not strict divides between badū and ḥaḍar, because we live the same lives. Our grandparents shared the same jobs, even though they were badū, ḥaḍar, ʿajam, or whatever, so I found that interesting.Footnote66

For those who did not recognize the unifying nature of the museum’s narrative, most understood the museum as separately displaying the desert and the sea lifestyles, and they were drawn to the portrayals that were the most personally relevant to them. For example, Shaikha, whose ancestors were engaged in pearling, noted that her favorite exhibit was the depiction of the coastal lifestyle and in particular the pearl divers. Shaikha felt a personal connection with one of the depicted images, noting that the “old lady in her baṭṭūlah [traditional face mask] cooking or sewing” and “singing old traditional songs” reminded her of her grandmother. She enjoyed learning about how “our grandparents went from being pearl divers to owning businesses, property, and stock” (emphasis added by authors).Footnote70 Likewise, Lulu loved the section on the sea because her grandfather and great-grandfather were both captains of pearling ships. She said, “This part was very nice, because as you walk, you are seeing the videos playing, you can hear the songs of the sea that they used to sing”.Footnote71

Personal connections did not necessarily match with the interlocutor’s self-defined identity. Noora, who self-identified as a ḥaḍar, nevertheless felt most connected when her grandmother told her stories about sewing Bedouin tents as they walked through the museum. She explained, “She [my grandmother] kept on remembering stuff. Like, as soon as she saw the woman sewing the tents, she was like, ‘Oh my God.’ She kept remembering how she used to live, so I felt included in that way. That is how my, not even my great-grandparents, my grandmother, that is how she lived. And I felt like I was part of it through that”.Footnote72

Both badū and ḥaḍar interviewees noted that they learned about the other cultural lifestyle through the museum. Shaikha noted, “I did not know anything about the lives of the people in the desert at all. I learned more about the Bedouin families and how they lived from the museum”.Footnote73 Maryam likewise said that she learned about the pearling business through the exhibits. These reactions show an interest in others and an eagerness to learn, but the lack of explicit recognition among our interlocutors of the connection between the different galleries also provides evidence that questions the success of the museum in communicating the idea of a unified lifestyle among the people of Qatar.

When asked if they felt included in this national narrative, most interviewees with ḥaḍar or badū heritage agreed. However, it is important to note that some did not feel included in the focus on the desert-and-sea lifestyle, particularly the two interlocutors with coastal, trading origins. Layal stated that the museum was “focused on pearling or the desert, [and] certain things were neglected”. She elaborated:

If you are going to talk about the history of development, there are a lot of people in certain areas and positions that worked for this country who played major roles. They helped the state during its time of development. We should ask, what were their origins and from where did they come? There are other groups –– certain families that controlled trade –– and before oil was discovered, trade was among the forces that helped the country develop, and it was a source of income that would later help the country become more modernized and urbanized. Why wasn’t trade focused on in the museum? It wasn't given the attention it deserved. Pearling and the history of the desert were not the only two forces.Footnote74

To some extent, I could have felt marginalized because [pause] it wasn’t my history that was being represented … . I feel like I was purposely avoided. It was a discussion that they didn’t want to have –– the museum curators didn’t want to have. There was an ideal representation of the society that they wanted to adhere to. And then everything else was, you know, kind of pushed aside.Footnote75

Why do certain Qatari citizens feel they are a part of an “ideal representation” of Qatari society, and not others? Khulood explained that ideas of tribal heritage and “purity” matter in Qatari society today:

I think, yeah, we do have tribalism, and I think you pride yourself on whether your tribe is purely Arab or a mixed tribe. Do you have blood from West Asia –– like Iran or Pakistan –– or are you fully Arab from Saudi Arabia? I feel like that does play a role in life here … . The more Arab you are, the more “pure” you are.Footnote76

It is important to point out that a lot of families came later to Qatar that were not included in the country from the start. I can say that they can’t include something that doesn’t exist, like, how can they include the families that came in the last forty years but they weren’t really there in the last hundred years. People only started migrating to Qatar when they saw that they could live there, and the discovery of oil brought in even more people. Qatar consisted of very few tribes and families and that is it. So I can say that what they [the museum] did was right and, in fact, the way they projected the history was good and it wasn’t controversial.Footnote77

Qataris share different ethnic, racial and cultural lifestyles. This is our reality and we shouldn’t be ashamed of it … . It is not fair to them to simply say that Qataris are from the sea or the desert. We are mixed.Footnote78

I would like to see all sides of my country’s history, people, and culture. I do not wish for things to be censored, because either way the truth will come out –– and there is no advantage to censoring facts –– and I would rather people learned it from a trusted place like a museum rather than the media. No one should be celebrated more than the other; everyone should be treated equally to ensure that we are all one and united. We do not want to keep making the same mistakes, where some people feel marginalized and left out because the louder voices and the majority are being celebrated and heard.Footnote80

6 Discussion and conclusion

Our investigation into the National Museum of Qatar’s identity narrative, and the reaction of our female Qatari interlocutors, gives us several important insights about the nature of national identity and nationalism during the region-wide crisis (June 2017–January 2021). First, it tells us that some Qataris still recognize the salience of societal divisions, even though they may personally disagree with these divisions and feel they are lessening over time. Second, some cultural heritages receive more focus in the national unity narrative of the museum, and others receive less. Since, as previously discussed, Qatar Museums oversees and guides the NMoQ, these choices indicate the relative weight placed on these divisions by Qatar Museums, and, by extension, the Qatari leadership. Third, we can speculate on the implications of these divisions, and a national narrative that includes some and excludes others, for the larger legal and political ramifications of national identity in Qatar.

Despite rentier wealth, Qatari society is still divided along cultural, geographic, and sectarian lines. Yet we see evidence of these divisions becoming less salient over time. Many of the interlocutors made the comparison between tensions of the past and a new sense of unity in the present, especially between badū and ḥaḍar. However, others talked about a feeling of marginalization for other groups in society who are outside of the established families of Qatar, especially those historically coastal families that never had ties to the desert. Here, the interviewees raised the example of families that traveled back and forth between Arabia and Persia over the years for trading and business. In the interviews, several people cautioned against continuing to make the mistake of celebrating some groups of people over others in society.

Our analysis of the NMoQ “people of Qatar” galleries revealed that some of these societal divisions are elided in the museum’s narrative. We have demonstrated how the museum combined the desert and sea lifestyles into a unified narrative. This narrative reduces the salience of the tensions between badū and ḥaḍar, which is an important step toward increasing the social unity of Qataris in the current moment of geopolitical crisis. Yet our interviewees had mixed perceptions of this unity narrative. Some agreed with the narrative that “we are all one”, while others focused more closely on the sections they felt represented their lifestyle and heritage.

Though the museum conveys a historically inaccurate narrative, eliding the differences between badū and ḥaḍar can be understood as an important part of building national unity. Yet while a unifying mode of identity presentation may reflect the spirit of interdependence within the Qatari community, it is also fundamentally a reimagination of Qatari heritage. In the presentation of dualistic identity only, the museum’s narrative both ignores historical reality and creates concerns among some of the Qatari interviewees who do not see themselves in such a narrative. In particular, those whose families are part of business and trade networks –– without a connection to the desert lifestyle –– said they felt excluded and marginalized.

The difference in how the museum’s unity narrative includes or excludes societal groups suggests that some of these divisions are more permanent or entrenched in society than others. The Qatari leadership, through Qatar Museums and other institutions and methods, has promoted unity between the badū and the ḥaḍar for decades.Footnote81 But the lesser focus on other groups in society, specifically those who do not identify with both of these cultural lifestyles, indicates that these groups are not a priority for integration into the national narrative.

In fact, this portrayal may lead to unintended consequences, such as reemphasizing citizens’ second-class status as per the Nationality Law, as the national narrative infers that one must have the Arab badū past to be a full citizen and a “real” or “pure” Arab. This conclusion is clear in Shaikha’s words, as she demonstrates that she is comfortable with an exclusionary national narrative that privileges only the “very few tribes and families” that were in Qatar for “the last hundred years”. Her description of the families who “came in the last forty years” and “only started migrating to Qatar when they saw that they could live there and the discovery of oil brought in even more people” is the common societal trope that allowed for the creation and continuation of the Nationality Law as it currently stands. This codification of two tiers of citizenship is thus being solidified in the national museum’s “unity” narrative.

It appears that, even in this moment of crisis, the geopolitical situation did not motivate Qatar Museums to present an even more inclusive national narrative. Did the museum miss an excellent opportunity, created by the international crisis, to reshape the national narrative in a more inclusive manner? Several interlocutors made clear that they understood the political sensitivity of the crisis in Qatar, and they connected the museum’s exhibits –– what was included or excluded –– to the blockade. In fact, some felt that by not mentioning specific tribes and their contributions, the narrative became a more inclusive one. Lulu explained how the emphasis on unity over tribalism is a positive message for Qatar at this time:

After the blockade, I see what they [the museum] did is a very good thing. Because the conflict over tribalism is basically not good … . This is a national museum for all nationals, not just for a particular group. This is a very good thing, because after the blockade even our Ardhas [sword dances] became one. All of us in one Ardha. All of the tribes in one Ardha. The monument they have in the museum, of us all holding hands with the flag, shows that we are all with Qatar. This is the main message, basically the main goal. We want, as a country, as citizens, to be treated the same, feel the same, and all of us are one. So this a good thing in my opinion.Footnote82

The blockade doesn't justify not accurately representing people. I understand that tribalism is a huge part of our society, but I think that there is nothing wrong with showing that we were once a tribal society or we still are, but there are also different groups involved. That is just depicting reality.Footnote83

This investigation into the unity narrative of the National Museum of Qatar, and the reaction of a segment of Qatari citizens to this narrative, brings up larger questions about the direction of nationalism in Qatar as a result of the crisis. Al-Malki argues that the aim of “a unified national identity” should be “to promote inclusiveness and pluralism, to eradicate discrimination within the existing citizenship model, and to embrace previously marginalized identities”.Footnote85 However, the NMoQ’s identity presentation of Qatari heritage still highlights an ethnic, rather than a civic, nationalism.Footnote86 This presentation does not seem to correspond with the Qatar National Vision 2030, which aims for increased civic inclusion in society. Such an ethnic presentation of nationalism leads to questions over who is considered part of the Qatari national narrative and who is not, and whether Qatari society can reach the stage of civic identity as called for in its 2030 Vision.

This study also demonstrates the difficulty involved in creating legal changes to the status of some of these societal groups. The ramifications of the Nationality Law relate to the citizenship status of the children of Qatari women and non-Qatari men –– a concern that Qatar recognized in the Qatar National Development Strategy.Footnote87 The move to create permanent residency status in Qatar is seen as a first-step solution for these families, but more is needed to provide full citizenship and all the associated rights and benefits for these children.Footnote88 This law also relates to the continued postponement of the Advisory Council elections, which are currently scheduled for October 2021.Footnote89 As the tiers of citizenship have different political rights of voting and candidacy, these issues need to be resolved before a national legislative election can take place. It is, however, a promising sign that the Amir established a committee to prepare for these elections.Footnote90 What all of this means is that even during a time of crisis, creating unity through social and legal means still takes time.

A final caveat: The national museum is massive. With eleven permanent galleries and one temporary exhibition space, spread out over 1.5 kilometers, many of the interviewees said they did not spend enough time there to see everything. Even with multiple trips, the authors still find something new during every visit. This is to say that the museum may indeed present more inclusive artifacts and stories of Qatari trading families, for example, as well as other ways for those outside of the badū/ḥaḍar dichotomy to feel represented in the heritage narrative. Yet the focus of our research is not only what the museum displays, in an objective sense, but also how visitors are perceiving these exhibits. These perceptions suggest that, despite the feelings of solidarity that appeared after the blockade, a unified national identity for Qatari society is still in flux.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jocelyn Sage Mitchell

Jocelyn Sage Mitchell is Assistant Professor in Residence, Northwestern University in Qatar, PO Box 34102, Doha, Qatar

Mariam Ibrahim Al-Hammadi

Mariam Ibrahim Al-Hammadi is Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Humanities, College of Arts and Sciences, Qatar University, PO Box 2713, Doha, Qatar, [email protected].

Notes

1 Roberts, Qatar: Securing the Global Ambitions of a City-State (2017); Coates Ulrichsen, Qatar and the Arab Spring (2014).

2 Legrenzi, The GCC and the International Relations of the Gulf: Diplomacy, Security and Economic Coordination in a Changing Middle East (2011); Kamrava, Troubled Waters: Insecurity in the Persian Gulf (2018).

3 Amnesty International, “Gulf Dispute: Six Months on, Individuals Still Bear Brunt of Political Crisis”, 14 December 2017; Bianco and Stansfield, “The Intra-GCC Crisis: Mapping GCC Fragmentation after 2011”, International Affairs 94.3 (2018), pp. 613–35; Coates Ulrichsen, Qatar and the Gulf Crisis (2020).

4 Mitchell and Allagui, “Car Decals, Civic Rituals, and Changing Conceptions of Nationalism”, International Journal of Communication 13 (2019), pp. 1368–88; for a specific example of nationalism through local dairy production, see: Koch, “Food as a Weapon? The Geopolitics of Food and the Qatar–Gulf Rift”, Security Dialogue.

5 Al-Hammadi, “Presentation of Qatari Identity at National Museum of Qatar: Between Imagination and Reality”, Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 16.1 (2018), pp. 1–10.

6 Davis and Gavrielides (eds), Statecraft in the Middle East: Oil, Historical Memory, and Popular Culture (1991); Erskine-Loftus, Hightower, and Al-Mulla (eds), Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives and Identity in the Arab Gulf States (2016); Exell and Rico, Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula: Debates, Discourses and Practices (2014); Peutz, “Heritage in (the) Ruins”, International Journal of Middle East Studies 49.4 (2017), pp. 721–28.

7 Mitchell, Beyond Allocation: The Politics of Legitimacy in Qatar, PhD diss. (2013).

8 Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar (1995); Erskine-Loftus (ed.), Reimagining Museums: Practice in the Arabian Peninsula (2013); Erskine-Loftus (ed.), Museums and the Material World: Collecting the Arabian Peninsula (2014); Exell, Modernity and the Museum in the Arabian Peninsula (2016); Exell and Wakefield (eds), Museums in Arabia: Transnational Practices and Regional Processes.

9 Beblawi and Luciani (eds), The Rentier State (1987); Al-Mulla, Museums in Qatar: Creating Narratives of History, Economics, and Cultural Co-operation, PhD diss. (2013).

10 Luciani, “Allocation vs. Production States: A Theoretical Framework”, The Rentier State, ed. Beblawi and Luciani (1987), p. 75.

11 Davidson, The United Arab Emirates: A Study in Survival (2005); Foley, The Arab Gulf States: Beyond Oil and Islam (2010); Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom (2019); Herb, All in the Family: Absolutism, Revolution, and Democracy in the Middle Eastern Monarchies (1999); Moritz, “Reformers and the Rentier State: Re-Evaluating the Co-Optation Mechanism in Rentier State Theory”, Journal of Arabian Studies 8.1 (2018), pp. 46–64; Okruhlik, “Rentier Wealth, Unruly Law, and the Rise of Opposition: The Political Economy of Oil States”, Comparative Politics 31 (1999), pp. 295–315; Okruhlik, “Rethinking the Politics of Distributive States: Lessons from the Arab Uprisings”, Oil States in the New Middle East: Uprisings and Stability, ed. Selvik and Utvik (2016), pp. 18–38; Valeri, Oman: Politics and Society in the Qaboos State (2009); Gengler and Mitchell, “A Hard Test of Individual Heterogeneity in Response Scale Usage: Evidence from Qatar”, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 30.1 (2018), pp. 102–24; Gengler, Shockley, and Ewers, “Refinancing the Rentier State: Welfare, Inequality, and Citizen Preferences toward Fiscal Reform in the Gulf Oil Monarchies”, Comparative Politics (2020); Mitchell and Gengler, “What Money Can’t Buy: Wealth, Inequality, and Economic Satisfaction in the Rentier State”, Political Research Quarterly 72.1 (2019), pp. 75–89.

12 Babar, “Population, Power, and Distributional Politics in Qatar”, Journal of Arabian Studies 5.2 (2015), pp. 139–40; Mitchell and Gengler, “What Money Can’t Buy”, p. 79.

13 Govt of Qatar, Qatar National Vision 2030 (2008).

14 Al-Ghanim, “Istirātījiyyat al-tanmiyyat al-waṭaniyyat li dawlat Qaṭar, 2011–2016: murājiʿat naqdiyya”, Al-Shaʿb yurīd al-iṣlāḥ fī Qaṭar … ayḍa, ed. Al-Kuwari (2012), pp. 109–16.

15 Al-Malki, “Public Policy and Identity”, Policy-Making in a Transformative State: The Case of Qatar, ed. Tok, Alkhater, and Pal (2016), p. 265.

16 Al-Hammadi, “Presentation of Qatari Identity”, pp. 3–5; Mitchell and Curtis, “Old Media, New Narratives: Repurposing Inconvenient Artifacts for the National Museum of Qatar”, Journal of Arabian Studies 8.2 (2018), pp. 210–13.

17 Bibby, Looking for Dilmun (1970), pp. 125–26; Nagy, “Making Room for Migrants, Making Sense of Difference: Spatial and Ideological Expressions of Social Diversity in Urban Qatar”, Urban Studies 43.1 (2006), pp. 119–37; Shockley and Gengler, “Marriage Market Preferences: A Conjoint Survey Experiment in the Arab Gulf”, paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, CA, 31 August – 3 September 2017.

18 Alshawi and Gardner, “Tribalism, Identity and Citizenship in Contemporary Qatar”, Anthropology of the Middle East 8.2 (2013), p. 55.

19 Nagy, “Making Room for Migrants”, p. 129.

20 Ibid.

21 Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf; Field, The Merchants: The Big Business Families of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States (1985), pp. 247–64; Al-Hammadi, “Presentation of Qatari Identity”, p. 4.

22 Al-Mulla, “History of Slaves in Qatar: Social Reality and Contemporary Political Vision”, Journal of History Culture and Art Research 6.4 (2017), pp. 85–111.

23 Mitchell and Allagui, “Car Decals”.

24 Partrick, “Nationalism in the Gulf States”, The Transformation of the Gulf: Politics, Economics and the Global Order, ed. Held and Ulrichsen (2012), pp. 47–65.

25 Govt of Qatar, “Law No. 38 of 2005 on the Acquisition of Qatari Nationality” (2005).

26 Al-Kuwari, “Muqaddima”, Al-Shaʿb yurīd al-iṣlāḥ fī Qaṭar … ayḍa, ed. Al-Kuwari (2012), p. 15.

27 Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf, p. 113.

28 Ibid., pp. 116–18.

29 Commins, The Gulf States: A Modern History (2012), p. 150; Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf, p. 5.

30 Al-Hammadi, “Presentation of Qatari Identity”, p. 5.

31 Mitchell et al., “In Majaalis Al-Hareem: The Complex Professional and Personal Choices of Qatari Women”, DIFI Family Research and Proceedings 4 (2015); Shockley and Gengler, “The Micro-foundations of Patriarchy: Spouse Selection Preferences in the Arab Gulf”, presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, CA, 31 August – 3 September 2017.

32 Mitchell, “Beyond Allocation”, pp. 147–48, 300–02; Al-Sayed, “Opinion: Will Qatar Finally See Legislative Elections?”, Doha News, 16 May 2013.

33 Al-Mulla, “The Development of the First Qatar National Museum”, Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula: Debates, Discourses and Practices, ed. Exell and Rico (2014), pp. 117–25.

34 Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf, pp. 161–64; Al-Mulla, Museums in Qatar; Spivak, In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics (1988), pp 118–33.

35 Al-Mulla, Museums in Qatar.

36 Al-Hammadi, “Presentation of Qatari Identity”, p. 2.

37 Al-Malki, “Public Policy and Identity”, p. 252.

38 Mitchell and Curtis, “Old Media, New Narratives”, p. 214; Mitchell, “We’re All Qataris Here: The Nation-Building Narrative of the National Museum of Qatar”, Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives and Identity in the Arab Gulf States, ed. Erskine-Loftus, Hightower, and Al-Mulla (2016), pp. 59–72.

39 cooke, Tribal Modern: Branding New Nations in the Arab Gulf (2014); Bounia, “The Desert Rose as a New Symbol for the Nation: Materiality, Heritage and the Architecture of the New National Museum of Qatar”, Heritage and Society 11.3 (2018), pp. 211–28.

40 Mitchell, “We’re All Qataris Here”, p. 66.

41 Althani, Jassim the Leader: Founder of Qatar (2012); Fromherz, Qatar: A Modern History (2012); Zahlan, The Creation of Qatar (1979).

42 Al-Abdulla, A Study in Qatari-British Relations 1914–1945 (1981); Al-Abdulla et al., Qatar’s Modern and Contemporary Development: Chapters of Political, Social and Economic Development, chapter 2: “Creation and Development of Qatar until 1868”; Anscombe, The Ottoman Gulf: The Creation of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar (1997); Ibrahim, Qatar al-ḥadithat: qarāʿat fī wathāʾiq sanawāt nashāt ʾāmārat Āl Thānī 1840–1960 (2013); Al-Mansur, Al-ṭatawwur al-siyāsī li Qatar, 1916–1949 (1979); Onley, “The Politics of Protection in the Gulf: The Arab Rulers and the British Resident in the Nineteenth Century”, New Arabian Studies 6 (2004), pp. 30–92.

43 Coates Ulrichsen, “Missed Opportunities and Failed Integration in the GCC”, The GCC Crisis at One Year: Stalemate Becomes New Reality, ed. Azzam and Harb (2018), pp. 49–58.

44 Gengler and Al-Khelaifi, “Crisis, State Legitimacy, and Political Participation in a Non-Democracy: How Qatar Withstood the 2017 Blockade”, Middle East Journal 73.3 (2019), pp. 397–416; Mitchell and Allagui, “Car Decals”.

45 Al-Hammadi, “Presentation of Qatari Identity”, p. 1. This concern is shared by Al-Malki, “Public Policy and Identity”.

46 For example, in September 2017, the Amir H.H. Shaikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani used his UN General Assembly speech to declare, “Allow me, on this occasion and from this podium, to express my pride in my Qatari people, along with the multinational and multicultural residents in Qatar”. This quote was subsequently displayed throughout the country, in newspapers, billboards, art exhibits, and commercial websites. See: Mitchell and Curtis, “Old Media, New Narratives”, p. 237.

47 Al-Hammadi, “Presentation of Qatari Identity”, p. 6.

48 Maziad, “Qatar: Cultivating ‘the Citizen’ of the Futuristic State”, Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives and Identity in the Arab Gulf States, ed. Erskine-Loftus, Hightower, and Al-Mulla (2016), pp. 123–40.

49 Al-Kuwari, “Muqaddima”; Al-Malki, “Public Policy and Identity”, pp. 254–55.

50 Maziad, “Qatar: Cultivating ‘the Citizen’”.

51 Al-Mulla, Museums in Qatar.

52 Shaikh Faisal bin Jassim Al Thani, oral history, National Museum of Qatar. Mitchell museum visit, 29 April 2019.

53 Jumaan Bashir Al-Hamad, oral history, National Museum of Qatar. Mitchell museum visit, 29 April 2019.

54 Ahmad Abdullah Al-Sulaiti, oral history, National Museum of Qatar. Mitchell museum visit, 29 April 2019.

55 Sultan Rashid Al-Hitmi, oral history, National Museum of Qatar. Mitchell museum visit, 29 April 2019.

56 Sharifa Hassan Al-Muhannadi, oral history, National Museum of Qatar. Mitchell museum visit, 16 April 2019.

57 Benstead, “Effects of Interviewer-Respondent Gender Interaction on Attitudes toward Women and Politics: Findings from Morocco”, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 26.3 (2014), pp. 369–83.

58 As of November 2020, there were approximately 2.7 million people in Qatar. Qataris are estimated to be around 330,000–350,000 of this population, although official numbers are unpublished.

59 Mitchell, “Transnational Identity and the Gulf Crisis: Changing Narratives of Belonging in Qatar”, presented at the Gulf Research Meeting, Cambridge, UK, 15–18 July 2019; Koch, “Is Nationalism Just for Nationals? Civic Nationalism for Noncitizens and Celebrating National Day in Qatar and the UAE”, Political Geography 54 (2016), pp. 43–53; Mitchell and Allagui, “Car Decals”; Vora and Koch, “Everyday Inclusions: Rethinking Ethnocracy, Kafala, and Belonging in the Arabian Peninsula”, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 15.3 (2015), pp. 540–52.

60 After their interviews, all interviewees were presented with a list of identity labels and were asked whether they wanted to choose any that signified part of their identity. These terms included various levels of tribal identity (tribe, section of a tribe, family) as well as badū, ḥaḍar, badū-mutaḥaḍar [badū that became ḥaḍar], and muhajin [dualistic]. Only a few of the interviewees labeled themselves with these terms without caveats, showing the sensitivity of public discussion of these social distinctions.

61 Interview with Lulu, 21 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

62 Interview with Khulood, 9 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

63 Interview with Dana, 24 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

64 Interview with Shaikha, 23 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

65 Interview with Noor, 15 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

66 Interview with Maryam, 25 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

67 Interview with Luna, 30 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

68 Interview with Sabicha, 15 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

69 Interview with Layal, 19 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

70 Interview with Shaikha, 23 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

71 Interview with Lulu, 21 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

72 Interview with Noora, 13 May 2019, Doha, Qatar.

73 Interview with Shaikha, 23 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

74 Interview with Layal, 19 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

75 Interview with Fatima, 24 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

76 Interview with Khulood, 9 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

77 Interview with Shaikha, 23 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

78 Interview with Dana, 24 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

79 Interview with Layal, 19 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

80 Interview with Dana, 24 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

81 Mitchell, “We’re All Qataris Here”, pp. 62–3.

82 Interview with Lulu, 21 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

83 Interview with Fatima, 24 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

84 Al-Malki, “Public Policy and Identity”, p. 267.

85 Ibid, p. 267.

86 Our interviews were conducted before the final gallery, “Qatar Today”, opened in December 2019. A visit to this gallery by Mitchell on 16 January 2020 provided preliminary evidence of a civic nationalism narrative that seeks to include both Qataris and expatriate residents. However, the shutdown of the museum in March 2020 due to COVID-19 concerns has prevented us from further research on the general public’s perceptions of this gallery. As well, our current study’s focus is on the retelling of Qatari history and heritage, rather than the depiction of modern-day Qatari society.

87 Govt of Qatar, Qatar National Development Strategy 2011–2016 (2011), p. 171.

88 Mitchell, “The Domestic Policy Opportunities of an International Blockade”, The Gulf Crisis: The View from Qatar, ed. Miller (2018), pp. 58–68.

89 Govt of Qatar, “HH the Amir Issues a Decree Extending the Term of Shura Council” (2019); Kerr, “Qatar Sets Date for Long-Promised Elections”, Financial Times, 3 November 2020.

90 Foxman and Al-Lawati, “Qatar Prepares for Legislative Elections After 15-Year Delay”, Bloomberg, 31 October 2019.

Bibliography

1 Primary sources

1.1 Publications

- Amnesty International, “Gulf Dispute: Six Months on, Individuals Still Bear Brunt of Political Crisis”, 14 December 2017, available online at www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/MDE2276042017ENGLISH.pdf.

- Government of Qatar, “Law No. 38 of 2005 on the Acquisition of Qatari Nationality” (2005), available online at www.almeezan.qa/LawPage.aspx?id=2591&language=en.

- Government of Qatar, “Qatar National Vision 2030” (2008), available online at www.gco.gov.qa/en/about-qatar/national-vision2030.

- Government of Qatar, Qatar National Development Strategy 2011–2016 (2011), available online at www.psa.gov.qa/en/nds1/Documents/Downloads/NDS_EN_0.pdf.

- Government of Qatar, “HH the Amir Issues a Decree Extending the Term of Shura Council” (2019), available online at www.gov.qa/wps/portal/media-center/news/news-details/hhtheamirissuesadecreeextendingthetermofshuracouncil.

1.2 Interviews with Qataris

- Dana (desert heritage interviewee), 24 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Fatima (coastal heritage interviewee), 24 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Ghalya (interviewee who did not disclose her heritage), 14 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Israa (coastal heritage interviewee), 26 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Jawaher (desert heritage interviewee), 28 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Johara (desert heritage interviewee), 30 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Khulood (mixed heritage interviewee), 9 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Layal (coastal heritage interviewee), 19 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Layla (desert heritage interviewee), 6 May 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Lulu (mixed heritage interviewee), 21 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Luna (desert heritage interviewee), 30 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Maha (coastal heritage interviewee), 19 May 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Maryam (desert heritage interviewee), 25 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Meem (desert heritage interviewee), 29 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Menna (desert heritage interviewee), 25 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Moza (mixed heritage interviewee), 31 March 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Natifa (interviewee who did not disclose her heritage), 28 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Nawal (interviewee who did not disclose her heritage), 3 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Noor (desert heritage interviewee), 15 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Noora (mixed heritage interviewee), 13 May 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Sara (coastal heritage interviewee), 15 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Sabicha (coastal heritage interviewee), 15 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Sahar (interviewee who did not disclose her heritage), 25 April 2019, Doha, Qatar.

- Shaikha (coastal heritage interviewee), 23 September 2019, Doha, Qatar.

2 Secondary sources

- Al-Abdulla, Yousif Ibrahim, A Study in Qatari-British Relations 1914–1945 (Doha: Orient Publishing & Translation, 1981).

- Al-Abdulla, Yousif Ibrahim; Ahmed Al-Sheliq; and Mustafa Al-Aqil, Qatar’s Modern and Contemporary Development: Chapters of Political, Social and Economic Development (Doha: Renoda Modern Press, 2015).

- Al-Ghanim, Issa, “Istirātījiyyat al-tanmiyyat al-waṭaniyyat li dawlat Qaṭar, 2011–2016: murājiʿat naqdiyya” [The National Development Strategy of the State of Qatar, 2011–2016: A Critical Review], Al-Shaʿb yurīd al-iṣlāḥ fī Qaṭar … ayḍa [The People Want Reform in Qatar … Too], edited by Ali Khalifa Al-Kuwari (Beirut: Al-Maaref Forum, 2012), pp. 109–16.

- Al-Hammadi, Mariam I., “Presentation of Qatari Identity at National Museum of Qatar: Between Imagination and Reality”, Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 16.1 (2018), pp. 1–10, available online at www.jcms-journal.com/articles/10,5334/jcms.171/.

- Al-Kuwari, Ali Khalifa, “Muqaddima” [Introduction], Al-sha ʿb yurīd al-iṣlāḥ fī Qaṭar … ayḍa [The People Want Reform in Qatar … Too], edited by Ali Khalifa Al-Kuwari (Beirut: Al-Maaref Forum, 2012), pp. 13–33.

- Al-Malki, Amal Mohammed, “Public Policy and Identity”, Policy-Making in a Transformative State: The Case of Qatar, edited by M. Evren Tok, Lolwah Alkhater, and Leslie A. Pal (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), pp. 241–69.

- Al-Mansur, Abdulaziz, Al-ṭatawwur al-siyāsī li Qatar, 1916–1949 [The Political Development of Qatar 1916–1949] (Kuwait: Dhat al-salasil, 1979).

- Al-Mulla, Mariam, Museums in Qatar: Creating Narratives of History, Economics, and Cultural Co-operation, PhD dissertation (University of Leeds, UK, 2013).

- Al-Mulla, Mariam, “The Development of the First Qatar National Museum”, Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula: Debates, Discourses and Practices, edited by Karen Exell and Trinidad Rico (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 117–25.

- Al-Mulla, Mariam, “History of Slaves in Qatar: Social Reality and Contemporary Political Vision”, Journal of History Culture and Art Research 6.4 (2017), pp. 85–111.

- Al-Sayed, Hassan, “Opinion: Will Qatar Finally see Legislative Elections?”, Doha News, 16 May 2013, available online at www.dohanews.co/opinion-will-qatar-finally-see-legislative-elections.

- Alshawi, A. Hadi and Andrew Gardner, “Tribalism, Identity and Citizenship in Contemporary Qatar”, Anthropology of the Middle East 8.2 (2013), pp. 46–59.

- Althani, Mohamed A.J., Jassim the Leader: Founder of Qatar (London: Profile Books, 2012).

- Anscombe, Frederick F., The Ottoman Gulf: The Creation of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

- Babar, Zahra, “Population, Power, and Distributional Politics in Qatar”, Journal of Arabian Studies 5.2 (2015), pp. 138–55.

- Beblawi, Hazem and Giacomo Luciani (eds), The Rentier State (London: Croom Helm, 1987).

- Benstead, Lindsay J., “Effects of Interviewer-Respondent Gender Interaction on Attitudes toward Women and Politics: Findings from Morocco”, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 26.3 (2014), pp. 369–83.

- Bianco, Cinzia and Gareth Stansfield, “The Intra-GCC Crisis: Mapping GCC Fragmentation after 2011”, International Affairs 94.3 (2018), pp. 613–35.

- Bibby, Geoffrey, Looking for Dilmun (New York: Knopf, 1970).

- Bounia, Alexandra, “The Desert Rose as a New Symbol for the Nation: Materiality, Heritage and the Architecture of the New National Museum of Qatar”, Heritage & Society 11.3 (2018), pp. 211–28.

- Coates Ulrichsen, Kristian, Qatar and the Arab Spring (London: Hurst, 2014).

- Coates Ulrichsen, Kristian, “Missed Opportunities and Failed Integration in the GCC”, The GCC Crisis at One Year: Stalemate Becomes New Reality, edited by Zeina Azzam and Imad K. Harb (Washington DC: Arab Center, 2018), pp. 49–58.

- Coates Ulrichsen, Kristian, Qatar and the Gulf Crisis (London: Hurst, 2020).

- Commins, David, The Gulf States: A Modern History (London: I.B. Tauris, 2012).

- cooke, miriam, Tribal Modern: Branding New Nations in the Arab Gulf (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

- Crystal, Jill, Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- Davidson, Christopher M., The United Arab Emirates: A Study in Survival (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2005).

- Davis, Eric and Nicolas E. Gavrielides (eds), Statecraft in the Middle East: Oil, Historical Memory, and Popular Culture (Miami, FL: Florida International University Press, 1991).

- Erskine-Loftus, Pamela (ed.), Reimagining Museums: Practice in the Arabian Peninsula (Boston: MuseumsEtc, 2013).

- Erskine-Loftus, Pamela, Museums and the Material World: Collecting the Arabian Peninsula (Boston: MuseumsEtc, 2014).

- Erskine-Loftus, Pamela; Victoria Penziner Hightower; and Mariam Ibrahim Al-Mulla (eds), Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives and Identity in the Arab Gulf States (London: Routledge, 2016).

- Exell, Karen, Modernity and the Museum in the Arabian Peninsula (New York: Routledge, 2016).

- Exell, Karen and Trinidad Rico, Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula: Debates, Discourses and Practices (Surrey: Ashgate, 2014).

- Exell, Karen and Sarina Wakefield (eds), Museums in Arabia: Transnational Practices and Regional Processes (London: Routledge, 2016).

- Field, Michael, The Merchants: The Big Business Families of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States (New York: Overlook Press, 1985).

- Foley, Sean, The Arab Gulf States: Beyond Oil and Islam (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2010).

- Foley, Sean, Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2019).

- Foxman, Simone and Abbas Al-Lawati, “Qatar Prepares for Legislative Elections After 15-Year Delay”, Bloomberg, 31 October 2019, available online at www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-31/qatar-prepares-for-legislative-elections-after-15-year-delay.

- Fromherz, Allen J., Qatar: A Modern History (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2012).

- Gengler, Justin and Buthaina Al-Khelaifi, “Crisis, State Legitimacy, and Political Participation in a Non-Democracy: How Qatar Withstood the 2017 Blockade”, Middle East Journal 73.3 (2019), pp. 397–416.

- Gengler, Justin J. and Jocelyn Sage Mitchell, “A Hard Test of Individual Heterogeneity in Response Scale Usage: Evidence from Qatar”, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 30.1 (2018), pp. 102–24.

- Gengler, Justin J.; Bethany Shockley; and Michael C. Ewers, “Refinancing the Rentier State: Welfare, Inequality, and Citizen Preferences toward Fiscal Reform in the Gulf Oil Monarchies”, Comparative Politics (2020), available online at https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5129/001041521X15903211136400.

- Herb, Michael, All in the Family: Absolutism, Revolution, and Democracy in the Middle Eastern Monarchies (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999).

- Ibrahim, Abdulaziz, Qatar al-ḥadithat: qarāʿat fī wathāʾiq sanawāt nashāt ʾāmārat Āl Thānī 1840–1960 [Modern Qatar: Reading in the Documents of the Years of the Foundation of Emirate of Al Thani 1840–1916] (Dar al-Saqi: Beirut, 2013).

- Kamrava, Mehran, Troubled Waters: Insecurity in the Persian Gulf (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018).

- Kerr, Simeon, “Qatar Sets Date for Long-Promised Elections”, Financial Times, 3 November 2020, available online at https://www.ft.com/content/6aa24499-8459-43c2-978d-9e044f9dd66a.

- Koch, Natalie, “Is Nationalism Just for Nationals? Civic Nationalism for Noncitizens and Celebrating National Day in Qatar and the UAE”, Political Geography 54 (2016), pp. 43–53.

- Koch, Natalie, “Food as a Weapon? The Geopolitics of Food and the Qatar–Gulf Rift”, Security Dialogue (2020), available online at https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010620912353.

- Legrenzi, Matteo, The GCC and the International Relations of the Gulf: Diplomacy, Security and Economic Coordination in a Changing Middle East (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011).

- Luciani, Giacomo, “Allocation vs. Production States: A Theoretical Framework”, The Rentier State, edited by Hazem Beblawi and Giacomo Luciani (London: Croom Helm, 1987), pp. 63–82.

- Maziad, Marwa, “Qatar: Cultivating ‘the Citizen’ of the Futuristic State”, Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives and Identity in the Arab Gulf States, edited by Pamela Erskine-Loftus, Victoria Penziner Hightower, and Mariam Ibrahim Al-Mulla (London: Routledge, 2016), pp. 123–40.

- Mitchell, Jocelyn Sage, Beyond Allocation: The Politics of Legitimacy in Qatar, PhD dissertation (Georgetown University, 2013).

- Mitchell, Jocelyn Sage, “We’re All Qataris Here: The Nation-Building Narrative of the National Museum of Qatar”, Representing the Nation: Heritage, Museums, National Narratives and Identity in the Arab Gulf States, edited by Pamela Erskine-Loftus, Victoria Penziner Hightower, and Mariam Ibrahim Al-Mulla (London: Routledge, 2016), pp. 59–72.

- Mitchell, Jocelyn Sage, “The Domestic Policy Opportunities of an International Blockade”, The Gulf Crisis: The View from Qatar, edited by Rory Miller (Doha: Hamad bin Khalifa University Press, 2018), pp. 58–68.

- Mitchell, Jocelyn Sage, “Transnational Identity and the Gulf Crisis: Changing Narratives of Belonging in Qatar”, presented at the Gulf Research Meeting, Cambridge, UK, 15–18 July 2019.

- Mitchell, Jocelyn Sage and Ilhem Allagui, “Car Decals, Civic Rituals, and Changing Conceptions of Nationalism”, International Journal of Communication 13 (2019), pp. 1368–88.

- Mitchell, Jocelyn Sage and Scott Curtis, “Old Media, New Narratives: Repurposing Inconvenient Artifacts for the National Museum of Qatar”, Journal of Arabian Studies 8.2 (2018), pp. 208–41.

- Mitchell, Jocelyn Sage and Justin J. Gengler, “What Money Can’t Buy: Wealth, Inequality, and Economic Satisfaction in the Rentier State”, Political Research Quarterly 72.1 (2019), pp. 75–89.

- Mitchell, Jocelyn Sage; Christina Paschyn; Sadia Mir; Kirsten Pike; and Tanya Kane, “In Majaalis Al-Hareem: The Complex Professional and Personal Choices of Qatari Women”, DIFI Family Research and Proceedings 4 (2015), available online at www.qscience.com/docserver/fulltext/difi/2015/1/difi.2015.4.pdf.

- Moritz, Jessie, “Reformers and the Rentier State: Re-Evaluating the Co-Optation Mechanism in Rentier State Theory”, Journal of Arabian Studies 8.1 (2018), pp. 46–64.

- Nagy, Sharon, “Making Room for Migrants, Making Sense of Difference: Spatial and Ideological Expressions of Social Diversity in Urban Qatar”, Urban Studies 43.1 (2006), pp. 119–37.

- Okruhlik, Gwenn, “Rentier Wealth, Unruly Law, and the Rise of Opposition: The Political Economy of Oil States”, Comparative Politics 31 (1999), pp. 295–315.

- Okruhlik, Gwenn, “Rethinking the Politics of Distributive States: Lessons from the Arab Uprisings”, Oil States in the New Middle East: Uprisings and Stability, edited by Kjetil Selvik and Bjørn Olav Utvik (New York, NY: Routledge, 2016), pp. 18–38.

- Onley, James, “The Politics of Protection in the Gulf: The Arab Rulers and the British Resident in the Nineteenth Century”, New Arabian Studies 6 (2004), pp. 30–92.

- Partrick, Neil, “Nationalism in the Gulf States”, The Transformation of the Gulf: Politics, Economics and the Global Order, edited by David Held and Kristian Ulrichsen (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 47–65.

- Peutz, Nathalie, “Heritage in (the) Ruins”, International Journal of Middle East Studies 49.4 (2017), pp. 721–28.

- Roberts, David B., Qatar: Securing the Global Ambitions of a City-State (London: Hurst, 2017).

- Shockley, Bethany and Justin J. Gengler, “The Micro-Foundations of Patriarchy: Spouse Selection Preferences in the Arab Gulf”, presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, CA, 31 August – 3 September 2017.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty, In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics (New York, NY: Routledge, 1988).

- Valeri, Marc, Oman: Politics and Society in the Qaboos State (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2009).

- Vora, Neha and Natalie Koch, “Everyday Inclusions: Rethinking Ethnocracy, Kafala, and Belonging in the Arabian Peninsula”, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 15.3 (2015), pp. 540–52.

- Zahlan, Rosemarie Said, The Creation of Qatar (London: Croom Helm, 1979).