ABSTRACT

Fruitful comparison of psychedelic, spiritual, and psychotic experiences requires a degree of phenomenological nuance. Some shared features of these phenomena, such as encounters and communications with supernatural entities, are obfuscated by scientific and clinical terminology. Other supposed distinctions are based on an atemporal view of dynamic experiences. In Section 2 of this theory-building paper, we examine how the trajectory of the psilocybin mushroom experience—from aversive feelings during the comeup, to awe-inspiring peak experience, to relief and clarity in the comedown—maps onto the trajectory of spiritual and incipient psychotic experiences. In Section 3 we argue that the shared trajectory of these experiences informs cognitive scientific perspectives on religion. Specifically, we propose a causal pathway in which stress, uncertainty, and arousal increase perception of extra agency (PEA) which may lead either to physio-emotional states and beliefs that downregulate PEA or to physio-emotional states and beliefs that perpetuate PEA. In Section 4 we examine how religions could modulate the causal pathway proposed in Part 2 to promote social cohesion.

1. Introduction

The question of whether psychedelic, spiritual, and psychotic experiences are related is of considerable import. Pragmatically, it is important to understand the potential benefits and risks of psychedelic use and spiritual pursuits, as well as the potential risks and benefits of psychospiritual challenges or crises. Theoretically, it is important to understand the biological bases and prosocial functions of experiences grounded in religious or spiritual traditions.

Classic serotonergic psychedelics have been called both entheogens (or divine-eliciting substances, Ruck et al., Citation1979), and psychotomimetics (or psychosis-mimicking substances, Osmond, Citation1957). Recent research supports the idea that psychedelics elicit peak, mystical (Griffiths et al., Citation2006; MacLean et al., Citation2011), entity-encounter (Davis et al., Citation2020), God-encounter (Griffiths et al., Citation2019), and anomalous experiences (Carbonaro et al., Citation2017) that fall under the umbrella of spiritual experience (see also Yaden & Newberg, Citation2022). On the other hand, it is less clear how psychedelics are linked to pathological experiences.

There is, however, a well-recognized overlap in the phenomenology of spiritual and psychotic experiences. Scholars have examined the impact of psychotic-like experiences on historical religious figures and traditions (Baldacchino, Citation2016; Cangas et al., Citation2008; Jaynes, Citation1976; Murray et al., Citation2012), the relationship between mystical experience and schizophrenia (Buckley, Citation1981; Hunt, Citation2000, Citation2007; Lukoff, Citation1985; Parnas & Henriksen, Citation2016), the relationship between religious conversion and psychosis (Hunt, Citation2000), the relationship between shamanism and psychosis (Brouwer et al., Citation2023d; Luhrmann, Citation2017; Polimeni, Citation2012, Citation2022; Polimeni & Reiss, Citation2002; Powers & Corlett, Citation2018; Ross & McKay, Citation2018), the relationship between trait schizotypy and spirituality (Crespi et al., Citation2019; Jackson, Citation1997; Willard & Norenzayan, Citation2017), the relevance of spiritual experience to clinical diagnosis and treatment of psychosis, and how to differentiate spiritual experience from psychosis (Boisen, Citation1936; DeHoff, Citation2015; Grof, Citation1989; Lukoff, Citation2007, Citation2019; Perry, Citation1977; Spittles, Citation2023). This overlap suggests that psychopharmacological models of spiritual experience should also apply to some aspects of psychosis (Brouwer & Carhart-Harris, Citation2021; Wießner et al., Citation2023).

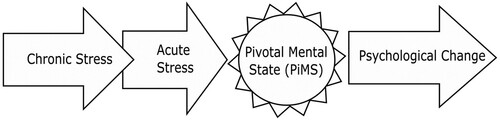

A recently developed theory of “pivotal mental states” (PiMSs) provides a mechanistic explanation of how stress increases psychedelic-like signaling in the brain, thereby contributing to spiritual or incipient psychotic experiences (Brouwer & Carhart-Harris, Citation2021). According to this model, chronic stress primes and acute stress triggers a pivotal mental state (PiMS) via activation of serotonin 2A receptors (). A PiMS is defined as a hyperplastic brain/mind state aiding rapid and deep learning, and is characterized by elevated cortical plasticity, an enhanced rate of associative learning, and an elevated capacity to mediate psychological transformation, conducive either to wellness or illness depending on contextual factors (Brouwer & Carhart-Harris, Citation2021).

Figure 1. A process-based model of psychological transformation. Chronic stress primes and acute stress triggers a pivotal mental state (PiMS) which facilitates psychological change. Adapted and redrawn from Brouwer and Carhart-Harris (Citation2021).

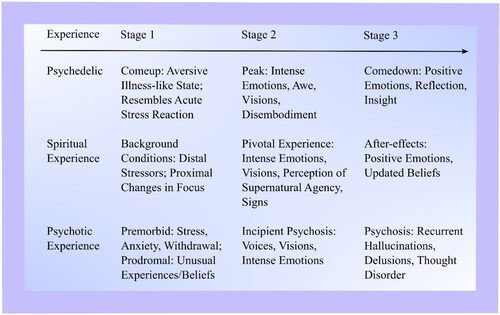

Brouwer and Carhart-Harris (Citation2021) refer to background literature on the spirituality-psychosis overlap (see references above), but do not provide a thorough phenomenological justification of their process-based PiMS model. Here we rectify that omission. The question of whether psychedelic, spiritual, and psychotic experiences are similar is fundamentally a question of phenomenology. In Section 2 of this piece, therefore, we use the psychedelic experience induced by psilocybin-containing mushrooms to examine how this experience maps onto the trajectory of spiritual and psychotic experiences, as depicted below in .

Figure 2. The first stage of the psychedelic experience (the comeup) resembles an acute stress reaction and relates to the distal and proximal triggers of spiritual experience and the premorbid and prodromal stages of psychosis. Peak psychedelic experiences are characterized by visions and intense emotions and resemble spiritual and incipient psychotic experiences. The psychedelic comedown maps onto the effects of naturally occurring spiritual experiences and is characterized by insights and an updating of beliefs. Delusional ideation in psychosis also evidences belief updating, but the perseverance or recurrence of hallucinations differentiates the psychotic experience from the typical psychedelic or spiritual experience. Some instances of recurrent spiritual experience are harder to differentiate from psychosis.

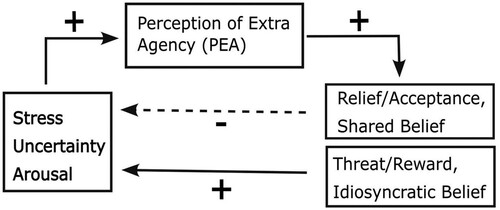

In Section 3 of this theory-building paper, we address how the shared experiential trajectory outlined in Section 2 is relevant to cognitive scientific perspectives on religion. Specifically, we present a psychological model of how stress increases perception of extra agency (PEA) and impacts emotional states and beliefs in ways that can either downregulate or upregulate subsequent stress reactions and PEA (see below). Perception of extra agency refers both to the perceptual or visionary experience of supernatural agents (e.g., God, angels, demons, ghosts) as well as the feeling that other people, objects, and events may possess extra human-like capacities and intentions. Suspecting others of conspiring or colluding, feeling that others can read or influence one’s thoughts, perceiving objects or events as potential “signs,” or feeling that spiritual forces are intervening in or guiding events, therefore, also fall under the umbrella of PEA. Further elaboration and justification of the construct of PEA can be found in Section 3.2.

In Section 4, we address how religious traditions could regulate aspects of the model presented in Section 3 () in order to promote well-being and prosocial beliefs and behaviors. Specifically, we suggest that religious rituals increase control over stress responses and that religious beliefs help guide perception of extra agency in ways that increase relief/acceptance, mutual trust, and shared values and allegiances amongst group members. By doing so, religious traditions help prevent antisocial, psychotic-like, and narcissistic orientations and social schisms that are likely to arise when individuals are stressed and predisposed to perception of extra agency (see bottom of pg. 10). Our model also helps explain mutual interactions between new religious movements and established traditions.

2. Comparing the trajectories of psychedelic, spiritual, and psychotic experiences

While the language of psychedelic journeys or trips implies a story-like sequence of experiences, recognition of different phases of the psychedelic experience has, until recently, been mostly anecdotal. However, a recent analysis by Brouwer et al. (Citation2023a) shows that the onset or “comeup” phase and falling or “comedown phase” of self-reported mushroom experiences are qualitatively different from peak psychedelic experiences.Footnote1

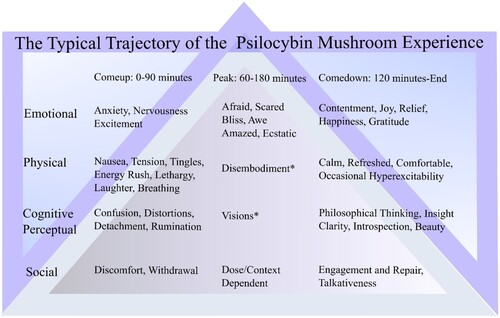

Specifically, individuals using magic mushrooms in recreational contexts often first feel nausea, anxiety, excitement, tingling, lethargy or increased energy, tension, as well as cognitive distortions, confusion, immobility, and social withdrawal behaviors. Peak psychedelic experiences follow and are characterized by high arousal and mixed valanced emotions of awe, ecstasy, and fear as well as intense visions. The comedown phase is characterized by positive emotions, relief, insight, cognitive clarity, and social engagement and enjoyment (Brouwer et al., Citation2023a). represents the trajectory of psilocybin mushroom experiences with an emphasis on those features that distinguish the comeup and comedown phases.

Figure 3. The temporal trajectory of the typical psilocybin mushroom experience as derived from analysis of self-reported mushroom experience reports archived in Erowid Experience Vaults (see Brouwer et al., Citation2023a). Asterisks indicate features of peak psilocybin experiences captured by Altered States of Consciousness (ASC) scales (see Preller & Vollenweider, Citation2016). Note that the overlapping timeframes for the comeup, peak, and comedown phases reflect variability in onset latencies and duration of peak psychedelic effects due to variability in drug dosage and other factors.

2.1. The comeup maps onto the stressful triggers of spiritual and psychotic experiences

The emotional, physical, cognitive-perceptual, and social features of the psilocybin mushroom comeup experience (see ) resemble an acute stress reaction and map well onto acute distress disorder symptoms of negative mood, hyperarousal, dissociation, and withdrawal (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2022; Cardeña et al., Citation2000; Shalev, Citation2002; World Health Organization, Citation2019).

Acute stress disorder is associated with the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as other psychiatric disorders (Bryant et al., Citation2012). Individuals with a history of trauma are also at higher risk of acute stress reactions (Cardeña & Carlson, Citation2011), supporting the idea that chronic stress primes acute stress reactions that may then precipitate psychedelic-like spiritual or psychotic experiences (see Brouwer & Carhart-Harris, Citation2021 and ).

Stressful events are known to trigger spiritual and psychotic experiences. Hardy (Citation1979) found that grief, depression, trauma, despair, and illness are some of the most common triggers of spiritual experience. Brouwer et al. (Citation2023c) also found that despair, illness, injury, or death (of others) are the most common distal background (occurring days to years before) triggers of religious and spiritual experience (RSE).

In contrast, common proximal (occurring the day of) triggers of spiritual experiences include walking or driving (often in nature), going to bed, personal prayer, or engaging in structured religious or spiritual practices. It is suggested that these proximal triggers of RSE may elicit temporary changes in focus or mild dissociative states (e.g., highway hypnosis) that in turn facilitate the unexpected emergence of visionary experiences (see Brouwer et al., Citation2023c).

A similar psychotogenic trajectory—from anxiety to dissociative-like experience to hallucinations—is evident in the development of psychotic disorders. The premorbid stage is characterized by anxiety, social disconnection, detachment, and impaired functioning, while the prodromal period that directly precedes first episode psychosis is characterized by increasing unusual experiences, persecutory and self-referential ideation, and a sense that the world is transforming (Fusar-Poli et al., Citation2022; Yung & McGorry, Citation1996).

These pre-psychotic experiences map onto the psychedelic comeup, as well as the distal stressors and anxieties that precede dissociative and visionary features of spiritual experiences. It is remarkable that a period of months or years of suffering and detachment preceding psychosis or spiritual experience can map onto a roughly hour-long comeup stage of the mushroom experience. However, we have already mentioned how chronic stress can prime acute stress reactions that elicit “pivotal mental states” conducive to spiritual and psychotic experiences (see Brouwer & Carhart-Harris, Citation2021 for review).

Moreover, it is worth highlighting that acute high-intensity stressors can directly trigger psychotic-like or spiritual experiences in the absence of a background of suffering. Acute sleep deprivation (Waters et al., Citation2018), ultra-long distance running (Carbone et al., Citation2020; Huang et al., Citation2021), cardiac arrest (Van Lommel et al., Citation2001), drowning (Tipton & Montgomery, Citation2022), and other life-threatening stressors (e.g., car accidents; see Taylor, Citation2022) can elicit brief dissociative and psychotic-like changes in emotion, perception, and belief.

During these experiences, the subject often first feels pain, exhaustion, lethargy, loss of focus, or panic before experiencing increased energy (e.g., second wind), physical lightness, decreased pain, hallucinations, senses of presence, or communications with supernatural entities (Huang et al., Citation2021; Tipton & Montgomery, Citation2022; Waters et al., Citation2018; Whitehead, Citation2016).

2.2. Peak psychedelic experience maps onto spiritual visions and psychotic hallucinations

Peak psychedelic experience of visions and communications with entities, bodily sensations of surging energy, senses of connectedness, revelations, and powerful emotions of love, awe, and fear map onto spiritual experiences.Footnote2 Some features of the peak psychedelic experience, such as surging energy, resemble an intense but general stress reaction, while certain emotional, social, and perceptual elements—intense emotions, senses of presence, visions, and communications with entities—are more specifically relevant to spiritual experience and psychosis.

Visions of entities are common in spiritual experience (Brouwer et al., Citation2023c; Hardy, Citation1979; Yaden & Newberg, Citation2022), and visual misperceptions of “shadow figures,” and complex visual hallucinations of people and faces are common in psychosis (Van Ommen et al., Citation2019; Waters et al., Citation2014). Feelings that entities are watching, evaluating, manipulating, or communicating with an individual are also common in both spiritual and psychotic experiences.

Auditory verbal hallucinations in psychosis often criticize, belittle, or threaten the subject (Larøi et al., Citation2019). In contrast, verbal communications in spiritual visions are typically reassuring, comforting, or inspiring (Brouwer et al., Citation2023c; Cook et al., Citation2022). Although communications with entities via words is common in spiritual experience, some of these communications present less like voices and more like thoughts that are attributed to other agents (Brouwer et al., Citation2023c; Cook et al., Citation2022). A similar description of “thought-voices” in psychosis is presented by Parnas et al. (Citation2023).

In summary, the perceptual visual and auditory-verbal features of spiritual visions and psychotic hallucinations overlap to a noticeable degree, and the social nature of these visions and hallucinations are also remarkably similar—if generally of an opposite valance. We do, however, also advise caution about overemphasizing the affective distinctions between peak psychedelic, and visionary spiritual and psychotic experiences. Psychedelic visions can be challenging and distressing, as depicted in Albert Hofmann’s classic description of being possessed by a demon (Hofmann, Citation1979/Citation2013, p. 20). Seeing, hearing, or sensing the presence of a malevolent force (e.g., a ghost or demon) is also not uncommon in RSE reports (Brouwer et al., Citation2023b). In these cases, feelings of relief and other positive emotions often occur after the resolution of the distressing visionary experience (see Section 2.3 below). Nevertheless, the social visions and messages that occur during peak psychedelic, spiritual, and psychotic experiences are all examples of perception of extra agency (PEA), which mediate between the states of arousal, uncertainty, and stress that precede these peak experiences, and the beliefs and emotional states that follow.

2.3. The psychedelic comedown maps onto the effects of spiritual and psychotic experiences

The psychedelic comedown is generally characterized by positive emotions, a sense of calm and relief, as well cognitive clarity, insightfulness, and increased sociality. In contrast to the self-focused ruminative thinking of the comeup, thinking during the comedown is both introspective as well as philosophical and expansive.

Individuals reporting on their experiences during the comedown write about the world, nature, God, and the human species—reflecting a cognitive as well as emotional sense of connection to other things (Brouwer et al., Citation2023a). It is noteworthy that certain types of spiritual and psychotic belief also evidence an expansive mood and extra sense of connection to other people, objects, or events. For example, delusions of imminent catastrophe and grandiosity overlap considerably with religious apocalyptic beliefs and millenarian beliefs in the imminent transformation of the world (Cohn, Citation1970).

Acknowledging that there is considerable overlap between certain types of psychotic and spiritual beliefs, it is also important to note general differences. Spiritual and religious experiences generally bring a sense of relief and stabilize beliefs that increase comfort, certainty, or acceptance (Brouwer et al., Citation2023b; DeHoff, Citation2015), perhaps lending an increased sense of control over further altered experiences should one choose to pursue them.

The belief systems adopted by the acutely psychotic individual—while perhaps motivating or helpful in explaining anomalous experiences in the very short-term—appear in the longer-term to perpetuate interpersonal conflict or avoidance, and the uncontrolled experience of altered experiences. Nevertheless, one can still posit that religious and spiritual beliefs and psychotic delusions both function to make sense of salient unusual experiences.

Fusar-Poli et al. (Citation2022) write

Delusions can be understood as new beliefs providing a satisfactory explanation of a strangely altered and uncanny reality and a basis for doing something about it—rather than incomprehensible and meaningless phenomena. Delusional beliefs can alleviate distress by replacing confusion with clarity, or promoting a shift from purposelessness to a sense of identity and personal responsibility. (p. 174)

In most reports of single RSEs, subjects are aware of a strong divide between normal waking perception and ASC-related experiences and visions. When religious and spiritual experiences are enduring, recurring, uncontrollable, and pervasive, however, the distinction from psychosis becomes noticeably less clear (Brouwer et al., Citation2023c).

2.4. Spiritual or psychotic: The importance of duration, recurrence, and pervasiveness

Recurrent or enduring experiences of spiritual awakening or spiritual emergency can be harder to distinguish from psychosis (see Brouwer et al., Citation2023c)—and are often distinguished based on functional outcomes (DeHoff, Citation2015). That is, if a person does not experience functional deterioration but rather positive improvements in their social and emotional functioning, this is a basis for calling an experience spiritual rather than psychotic (DeHoff, Citation2015). Nevertheless, some spiritual awakenings characterized by elevated mood, increased energy, and fixation on spiritual ideas and pursuits resemble manic-like episodes. A minority of individuals also report enduring manic-like responses to single doses of psilocybin mushrooms characterized by feelings of energy, racing and fixated thoughts, and inability to sleep (Brouwer et al., Citation2023a).

In a recent analysis of spiritual experiences from the Alister Hardy Database, Brouwer et al. (Citation2023c) divided reports of RSEs into descriptions of single and discrete experiences and descriptions of enduring or recurring experiences, respectively. While the basic phenomenological features of RSEs overlapped between these groups, several differences also became apparent. Firstly, enduring changes in identity were more common in reports of enduring and recurring RSEs. A tendency to pursue, study, and develop philosophical explanations of recurrent experiences was also much more common than with discrete experiences. Finally, a few reports of recurrent RSEs described psychiatric hospitalization and psychotic disorders, ascribed spiritual (divine or hellish) qualities onto others (e.g., doctors), or referenced extensive telepathic communication (Brouwer et al., Citation2023c).

While these features of recurrent and enduring RSEs bear resemblance to psychotic-like experiences, it is worth noting that in some cultures similar experiences may be interpreted as indications of spiritual illness or attack (Luhrmann & Marrow, Citation2016). Thus, when we make distinctions between psychosis and spiritual experience, it is admittedly from a western intellectual perspective.

3. Implications for the cognitive science of religion

The cognitive science of religion (CSR) aims to explore the cognitive and cultural mechanisms underlying the evolution and transmission of religion in human societies (Xygalatas, Citation2014). This field has only occasionally addressed specifically pathological experiences (McCauley & Graham, Citation2020) and only recently begun to engage research in the science of psychedelic experiences (Shults, Citation2022). Our analysis of the trajectories of psychedelic, spiritual, and psychotic experience is directly relevant to two questions that CSR commonly addresses: (1) Why do humans ascribe extra agency onto the environment? (2) Does religion increase prosociality and, if so, how?

3.1. A causal model of perception of extra agency (PEA)

The shared trajectory of spiritual and psychotic experiences indicates that stress and stress reactions precede a PEA and the development of beliefs that either increase well-being or risk promoting pathology. As mentioned previously, psychedelics are thought to elicit a similar trajectory by hijacking an adaptive stress-response within the brain (Brouwer & Carhart-Harris, Citation2021; Carhart-Harris & Nutt, Citation2017; Murnane, Citation2019). presents a simple causal pathway by which stress, uncertainty, and/or arousal increase PEA, which updates emotional states and beliefs in ways that can either downregulate or upregulate stress responses and PEA.

Figure 4. A model of how stress, uncertainty, or arousal can lead to increased perception of extra agency (PEA) that in turn impacts emotional states and beliefs that either downregulate (dotted line) or upregulate (solid line) subsequent stress responses and PEA. Note that this process could also start with PEA or belief updating due to other factors (e.g., participation in spiritual or religious activities).

3.2. Stress increases perception of extra agency (PEA)

Stewart Guthrie, a pioneer of the cognitive science of religion, claims that religion is an anthropomorphization of the world (Guthrie, Citation1993). Guthrie proposes that humans instinctively perceive the world in a maximally significant and “humanlike” way (Guthrie, Citation1993, p. 4), reasoning that it is more adaptive to momentarily perceive a boulder as a bear, than to mistake a bear for a boulder (Guthrie, Citation1993, p. 6). Guthrie applies similar reasoning to explain the benefits humans generally reap from over-perceiving human-like agency in the environment.

Justin Barrett (Citation2000, Citation2007) modifies Guthrie’s theory of religion as an anthropomorphization of the world into a hyper-active agency detection device (HADD) theory. Barrett proposes that people conceptually invoke intentional agents to explain sensory phenomena, especially when sensory data seems unreliable (Barrett, Citation2000). Marc Andersen (Citation2019) provides a compatible predictive coding account of HADD.

Existing theories explain why HADD is an advantageous response to immediate threats or uncertainty in the environment. This HADD response, while clearly relevant to the cognitive science of religion, also seems relevant to observations that hallucinations co-occur with or immediately follow context-dependent social anxiety and cues of danger in psychotic and trauma disorders (Delespaul et al., Citation2002; Lyndon & Corlett, Citation2020; McCarthy-Jones & Longden, Citation2015; although see Luhrmann et al., Citation2019). Incorporating these psychopathological insights into HADD frameworks could potentially help address the critique that HADD theories are fairly speculative and suffer from a lack of experimental support (see Andersen, Citation2019).

Existing HADD theories, however, do not attempt to explain why the perception of extra agency is often disconnected from immediate perceptual experience and proximal threats; for example, why people have visions of entities while lying safely in bed. Nor do they explain why the death of a loved one, interpersonal conflict, difficult life decisions, personal injury, or illness are some of the most common distal background factors preceding (years to days before) the perception of extra agency (PEA) within the context of discrete spiritual experiences (Brouwer et al., Citation2023c). An example of a stressful distal background preceding a spiritual experience is presented below (also see Brouwer et al., Citation2023c).

During the year previous to my experience, my life was totally out of control. I had reached my limit of spiritual and emotional loss. I was medicating myself with cocaine and alcohol. Married with my wife who was pregnant of [with] our 3rd child, life still felt meaningless.

From a functional perspective, it is our opinion that the distal triggers of spiritual and psychotic experiences often represent ongoing threats to one’s social self, which could include a loss of capacity to perform various functions due to illness or injury, or loss of allies or family due to death or interpersonal conflicts. The social nature of these threats helps explain the human-like nature of hidden agencies, and why these agencies and derivative beliefs generally address social concerns.

We use the language of “Perception of Extra Agency” (PEA) to create a degree of separation from existing HADD theories, not because these theories are wrong, but rather to broaden the scope of our explanatory framework to include distal background stressors, to include pathological and psychedelic as well as spiritual experiences of extra agency, and to include psychological phenomena that are not captured by HADD theories. For example, our notion of “extra agency” includes ascription of hidden intentions to real social actors.

3.3. Perception of extra agency updates social beliefs

Within psychedelic, psychotic, and spiritual experiences, PEA often precedes an updating of socioemotional beliefs and values, but exactly how PEA exerts an influence on social belief updating may vary on a case-by-case basis. Explicit messages from supernatural agents might directly impact the motivations and behaviors of an individual. For example, messages perceived to be conveyed by God to Moses, Jesus to St Paul, and the angel Gabriel to Mohammed are believed to have directly inspired the prophetic vocations of these religious exemplars. Individuals in the general population are also influenced by the messages of supernatural agents.

For example, one woman describing an RSE analyzed by Brouwer et al. (Citation2023c) writes “The voice [of Jesus] said ‘Follow your own star. Your name is starchild’ … [and] Within two days my name was legally changed.” Another woman writes,

I sat down on the little wall outside the building, and he [Christ] said something like “Don’t worry. I’m here. If I’m here, why would you worry?” … [and] I pray more since … and I am trying, and not succeeding, at being a better person and serving him.

A generalization of social beliefs and values is relevant to coalitional cognition, which can be distinguished from social cognition in general, in that the former is more specifically oriented around garnering social support, understanding allegiances, and coordinating social behavior (e.g., plans, conspiracies; see Bell et al., Citation2021). A generalization of what is good or bad across contexts, for example, may facilitate the development of strong moral beliefs that guide cooperation or opposition to different social coalitions. A recent review by Bell et al. (Citation2021) suggests psychosis represents a dysfunction of coalitional cognition, an idea that is supported by the predominance of delusional themes of persecution (e.g., being targeted by the CIA) and grandiose ideas about having a special social role supported by a group of allies (Hagen, Citation2008). A phenomenological examination of the anomalous existential orientation of psychosis-prone subjects generally supports these ideas. This anomalous existential orientation is characterized in part by an adherence to intellectual, spiritual, moralistic, or utopian ideologies detached from the concrete, bodily, individual, or contextual realities of social or practical life (Sass et al., Citation2017, see Section 6.9). The formation of abstract ideologies involves an attempt, on the part of the subject, to frame their experiences and judgements of the world in alignment or opposition to other groups, reflecting a generalization of beliefs across contexts that plausibly facilitates coalitional cognition.

Coalitional preoccupations, of course, are not necessarily pathological. They are also evident in apocalyptic and millenarian religious thought (e.g., the idea of an elect group; see Cohn, Citation1970), and more generally in religious and political rhetoric that demonizes the other and validates the in-group. Psychotic delusions may be distinguished by the fact that people most affiliated with the subject (family, friends, community) do not openly endorse the persecutory, grandiose, and self-referential thoughts of the subject. However, it is also recognized that self-proclaimed messiahs throughout history are often strangers to the flock that eventually recognize their authority (see Cohn, Citation1970).

From a functional evolutionary perspective, the social risks associated with espousing grandiose and persecutory beliefs are substantial and include losing the trust and respect of fellow group members. However, the potential benefits of rallying supporters against a common enemy may, in certain contexts, outweigh the social risks, especially when an individual has little social status to lose and potentially much to gain (see Hagen, Citation2008). We suggest above that the distal triggers of psychotic and spiritual experiences may represent ongoing threats to one’s social self. An increase in PEA under such circumstances, including increased coalitional cognition (e.g., consideration of the motives and plans of other groups), may be adaptive, allowing individuals to reevaluate their group affiliations in contexts of social threat.

3.4. Social beliefs modulate stress and uncertainty

In the previous two sections, we have outlined how stress increases PEA which facilitates an updating of social beliefs and emotions. In , however, we also depict how beliefs associated with social perceptions of threat (persecutory beliefs) or reward (grandiose beliefs) could increase arousal and stress responses, presumably to activate cognitive–behavioral sequalae to avoid or engage with social threats or opportunities. Therefore, it is possible that the causal process outlined in could start with increased stress, arousal, or uncertainty, or via an updating of social beliefs that subsequently increases stress, uncertainty, and arousal. The possibility of either starting point is supported by psychosis literature. For example, it has been suggested that delusions function to stabilize an unreliable perception of the world (see above; Fusar-Poli et al., Citation2022). While we agree that this is a common function of beliefs in general, this view implies that perceptual aberrations occur first in psychosis, which is not always the case (Compton et al., Citation2012). Delusions often occur in the absence of hallucinations, or precede hallucinations (Compton et al., Citation2012), suggesting that delusional ideation may in some cases be the initial driver of increased arousal and perception of extra agency (PEA).

Regardless of whether incipient psychosis is initially driven by unusual perceptual experiences or delusional ideation, which may vary on case-by-case basis, a cyclical perpetuation of the causal process outlined in could contribute to the recurrence and development of psychotic symptomology. For example, recurrently detecting extra agency in one’s immediate environment could lead one from mere feelings of suspicion to the belief that one is being intentionally deceived by hostile forces, or secretly supported by benevolent allies—introducing extra elements of deception that further impede the falsification of delusional ideation.Footnote3 See Sperber et al. (Citation2010) for a review of the construct of epistemic vigilance (also McKay & Ross, Citation2021).

Therefore, while PEA and social coalitional beliefs may be helpful for identifying and responding to social threats and opportunities, as outlined in Section 3.3, a dysfunctional amplification and perpetuation of this process could contribute to psychosis-spectrum conditions (Bell et al., Citation2021). At the extreme clinical end of this spectrum lie psychotic disorders or mood disorders with psychotic features. At the less extreme subclinical end of this spectrum lie personality disorders (e.g., paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, antisocial, and narcissistic personality disorders), that, while not necessarily indicative of severe pathology, are nevertheless associated with suspicious, antisocial, and self-righteous orientations that may seriously endanger social relationships and social cohesion.Footnote4

4. Religions modulate the “stress-PEA-belief” pathway

The possible negative or destabilizing effects of PEA and social coalitional belief updating, both for individuals and societies, should be considered when theorizing about the prosocial functions of religion and other social institutions. Various cognitive scientific theories of religion focus on potential prosocial functions of religion. Some theories highlight the role of moralizing high-gods in punishing uncooperative social behaviors (Henrich, Citation2011; Lang et al., Citation2019; Roes & Raymond, Citation2003; White et al., Citation2019), a function that has now been extended to minor deities and spirits as well (Singh et al., Citation2021).

Other scholars highlight the prosocial functions of rituals in promoting individual healing and synchronization of beliefs (Gelfand et al., Citation2020; Xygalatas, Citation2022). It is beyond the purview of this piece to review all the relevant literature on the prosocial functions of religion, so we focus specifically on the ways in which religion might modulate the stress- PEA- belief pathway (in ) and thereby reduce the likelihood and impact of pathological, dysfunctional, and antisocial beliefs and behaviors.

It is entirely possible that a controlled engagement of PEA, for example via religious ritual and indoctrination, subsequently downregulates uncontrollable stress responses and an uncontrollable perpetuation of PEA in contexts of unavoidable social interaction that may increase social uncertainty and anxiety. We proceed to identify plausible mechanisms by which religious rituals and beliefs may control the stress- PEA- belief pathway outlined in .

Religious rituals are performed at regular intervals but also when an individual group member is faced with challenging life events (e.g., death of loved one, transition to adulthood, marriage, birth of a child). By influencing arousal or eliciting a stress response in controlled, predictable and often communal settings, religious rituals may reduce feelings of anxiety (Lang et al., Citation2020; although see Karl & Fischer, Citation2018), pain (Xygalatas et al., Citation2019), uncertainty (Legare & Souza, Citation2014), and social disconnection (Rossano, Citation2012; Wood, Citation2017), and either increase the detection of benevolent agency or increase perceived control over malevolent agency. For example, Brouwer et al. (Citation2023d) describe how ritual control of stress responses and altered states of consciousness plays a role in healing shamanic sickness (see also Luhrmann et al., Citation2023). To provide a more general example, ritual offerings or sacrifices may solidify the support of benevolent supernatural agents (e.g., God), or appease potentially malevolent spirits, leading to a temporary reprieve from worry, and a decrease of PEA, and idiosyncratic belief updating outside of ritual contexts. Ritual, therapeutic use of psychedelic agents share with religious rituals this emphasis on “set and setting” (Carhart-Harris et al., Citation2018; Hartogsohn, Citation2016).

Shared religious beliefs specify the intentions and authority of supernatural entities (e.g., God) and their human intermediaries (e.g., priests), thus reducing the need to question the intentions and authority of supernatural and human agencies associated with one’s religious group. Christians in the USA, for example, are more likely to trust other Christians (Thunström et al., Citation2021), and states that support a dominant religion, are more likely to be trusted by citizens adhering to the dominant religion (Fox et al., Citation2024). Shared religious beliefs not only decrease epistemic content vigilance within an in-group (see Sperber et al., Citation2010), but also provide a basis for punishing competing (e.g., heretical) beliefs and authorities that might foster uncertainty and social schisms. Many mainstream religious beliefs also create a degree of separation between human affairs and the divine. A metaphysicalization of divine power as operating primarily in spiritual realms (e.g., after death in heaven and hell, or during transitions between death and rebirth) may dampen expectations for divinely mediated rewards and punishments in this world, and diminish beliefs in hidden agencies directly interfering in human affairs. Dampening feelings of imminent threat and reward could subsequently decrease the perpetuation of the causal process outlined in . As mentioned above in Section 2.4, recurrent RSEs (reflecting recurrent PEA) involve more ascriptions of angelic, demonic, omniscient (e.g., mind-reading), and omnipotent powers onto familiar others and supernatural forces in one’s immediate environment (see Brouwer et al., Citation2023c). Recurrent RSE reports, in contrast to single RSE reports, also include reference to psychotic disorder and psychiatric hospitalization (Brouwer et al., Citation2023c). Of course, we recognize the overlap here between certain types of idiosyncratic psychotic belief (e.g., religious delusions, delusions of imminent catastrophe) and certain types of apocalyptic and millenarian beliefs that, while not necessarily idiosyncratic, do reflect an increased sense of imminent threat or reward (see ). We also recognize that some spiritual traditions may attempt to break the causal process outlined above rather than guide it, for example, by viewing aversions and attachments, as well visionary experiences and fluctuations in arousal, as impediments or distractions to overcome in order to achieve a state of clarity and equanimity.

Having provided some preliminary suggestions for how spiritual or religious traditions might influence the causal process outlined , we fully recognize that these suggestions need to be developed and supported by more thorough analyses in the future.

Nevertheless, with or without religion, individuals will still perceive extra agency in this world. There is little evidence that decreased religious affiliation in the western world is associated with increasing socio-political “rationality” as hypothesized by some formulations of the secularization thesis. Spirituality, conspiracy thinking, science skepticism, and identity politics are arguably increasing, not decreasing, in the western world (Fuller, Citation2001; Noury & Roland, Citation2020; Rutjens et al., Citation2022). In modern and contemporary socio-political discourses, extra agency (e.g., hidden intentions, conspiracies) is regularly ascribed to other social classes based on racial, ethnic, economic, religious, and political orientations and may be associated with nonnormative political engagement (Imhoff et al., Citation2021).

It follows that the ways in which religious rituals and beliefs modulate and potentially downregulate the stress- PEA- belief pathway are not just relevant to religions. All social institutions have rituals that help instantiate the authority of specific individuals and values, and beliefs that reinforce the authority of these individuals and values, and the social institutions that they represent. The fact that shared social beliefs are not only indispensable for competing against other social groups, but also for preventing the emergence of potentially disruptive patterns of thought and behavior within an in-group, including thought and behavior we deem pathological, has important implications not just for functional theories of religion, but also for understanding the ethical challenges presented by divergent or countercultural social movements and idiosyncratic thoughts and behaviors.

5. Conclusion and future considerations

In this theory building paper, we have compared the trajectory of psychedelic, spiritual, and psychotic experiences, highlighting how the beginnings of these experiences resemble stress reactions, followed by peak visionary experiences that subsequently lead to an updating of social beliefs and emotional states. Informed by this comparative phenomenological analysis, we present a causal model by which stress, uncertainty, and arousal increases perception of extra agency (PEA) that can facilitate shared beliefs and emotional states (e.g., relief and acceptance) that subsequently downregulate the causal process, or to idiosyncratic beliefs and emotional states (e.g., anticipations of threat or reward) that can perpetuate the causal process (see ). Finally, we provide some preliminary thoughts on how spiritual and religious traditions might regulate this causal process via rituals and the promotion of shared beliefs.

Having reviewed how stress-elicited psychedelic signaling in the brain provides a mechanistic explanation for the common trajectory of psychedelic, spiritual, and psychotic experiences (Brouwer & Carhart-Harris, Citation2021), questions remain as to whether other psychotomimetic drugs also have something to teach us about the neurobiology and phenomenology of these trajectories, and the processes that lead to functional vs dysfunctional outcomes (see Brouwer et al., Citation2023b). Future projects should also develop the preliminary ideas presented in Section 4 by examining the ways in which spiritual and religious traditions may guide or potentially disrupt the causal process outlined in Section 3 (see ). We expect and hope that future investigations will help clarify, build upon, and revise the ideas presented here.

Author contributions

All authors (AB, CLR, and SFLR) were involved in developing the conceptual framework for the article and in writing and editing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The terms comeup, peak, and comedown are adopted from colloquial parlance to describe the different phases of a psychedelic experience.

2 Note that spiritual experiences on average last minutes (Yaden & Newberg, Citation2022) and thus may be better modeled by psychedelic experiences elicited via intravenous, insufflation, or inhalation routes of administration.

3 Note that accusations of deception and hidden motives are often levied to dispel the validity of alternative explanations or competing beliefs, for example in the political arena, and are therefore by no means exclusive to psychosis.

4 Note that various religious and political visionaries throughout history displayed traits associated with various personality disorders.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.) APA Publishing.

- Andersen, M. (2019). Predictive coding in agency detection. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 9(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2017.1387170

- Baldacchino, J. P. (2016). Visions or hallucinations? Lacan on mysticism and psychosis reconsidered: The case of St George of Malta. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 32(3), 392–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12230

- Barrett, J. L. (2000). Exploring the natural foundations of religion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01419-9

- Barrett, J. L. (2007). Cognitive science of religion: What is it and why is it? Religion Compass, 1(6), 768–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2007.00042.x

- Bell, V., Raihani, N., & Wilkinson, S. (2021). Derationalizing delusions. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(1), 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620951553

- Belser, A. B., Agin-Liebes, G., Swift, T. C., Terrana, S., Devenot, N., Friedman, H. L., … Ross, S. (2017). Patient experiences of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(4), 354–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167817706884

- Boisen, A. T. (1936). The exploration of the inner world: A study of mental disorder and religious experience. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Brouwer, A., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2021). Pivotal mental states. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 35(4), 319–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120959637

- Brouwer, A., Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Raison, C. L. (2023a). The temporal trajectory of the psychedelic mushroom experience mimics the narrative arc of the hero’s journey [manuscript under review].

- Brouwer, A., Carhart-Harris, R., & Raison, C. L. (2023b). Psychotomimetic compensation and sensitization [preprint]. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/y8dn2

- Brouwer, A., Raison, C. L., & Shults, F. L. R. (2023c). From suffering to salvation: Making sense of religious experiences [manuscript under review].

- Brouwer, A., Winkelman, M. J., & Raison, C. L. (2023d). Shamanism: Psychopathology and psychotherapy. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2023.2258212

- Bryant, R. A., Creamer, M., O’Donnell, M., Silove, D., & McFarlane, A. C. (2012). The capacity of acute stress disorder to predict posttraumatic psychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(2), 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.007

- Buckley, P. (1981). Mystical experience and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 7(3), 516–521. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/7.3.516

- Cangas, A. J., Sass, L. A., & Pérez-Álvarez, M. (2008). From the visions of Saint Teresa of Jesus to the voices of schizophrenia. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 15(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1353/ppp.0.0187

- Carbonaro, T. M., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Comparison of anomalous experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms in research and non-research settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 171, e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.107

- Carbone, M. G., Pagni, G., Maiello, M., Tagliarini, C., Pratali, L., Pacciardi, B., & Maremmani, I. (2020). Misperceptions and hallucinatory experiences in ultra-trailer, high-altitude runners. Rivista di Psichiatria, 55, 183–190.

- Cardeña, E., & Carlson, E. (2011). Acute stress disorder revisited. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104502

- Cardeña, E., Koopman, C., Classen, C., Waelde, L. C., & Spiegel, D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire (SASRQ): A valid and reliable measure of acute stress. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(4), 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007822603186

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Nutt, D. J. (2017). Serotonin and brain function: A tale of two receptors. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 31(9), 1091–1120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117725915

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Roseman, L., Haijen, E., et al. (2018). Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 32(7), 725–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881118754710

- Cohn, M. (1970). The pursuit of the millenium. Oxford University Press.

- Compton, M. T., Potts, A. A., Wan, C. R., & Ionescu, D. F. (2012). Which came first, delusions or hallucinations? An exploration of clinical differences among patients with first-episode psychosis based on patterns of emergence of positive symptoms. Psychiatry Research, 200(2–3), 702–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.041

- Cook, C. C., Powell, A., Alderson-Day, B., & Woods, A. (2022). Hearing spiritually significant voices: A phenomenological survey and taxonomy. Medical Humanities, 48(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2020-012021

- Crespi, B., Dinsdale, N., Read, S., & Hurd, P. (2019). Spirituality, dimensional autism, and schizotypal traits: The search for meaning. PLoS One, 14(3), e0213456. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213456

- Davis, A. K., Clifton, J. M., Weaver, E. G., Hurwitz, E. S., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2020). Survey of entity encounter experiences occasioned by inhaled N,N-dimethyltryptamine: Phenomenology, interpretation, and enduring effects. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 34(9), 1008–1020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120916143

- DeHoff, S. L. (2015). Distinguishing mystical religious experience and psychotic experience: A qualitative study interviewing Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) professionals. Pastoral Psychology, 64(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-013-0584-y

- Delespaul, P., devries, M., & van Os, J. (2002). Determinants of occurrence and recovery from hallucinations in daily life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37(3), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270200000

- Duerler, P., Schilbach, L., Stämpfli, P., Vollenweider, F. X., & Preller, K. H. (2020). LSD-induced increases in social adaptation to opinions similar to one’s own are associated with stimulation of serotonin receptors. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 12181. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68899-y

- Fox, J., Eisenstein, M., & Breslawski, J. (2024). State support for religion and social trust. Political Studies, 72(1), 322–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217221102826

- Fuller, R. C. (2001). Spiritual, but not religious: Understanding unchurched America. Oxford University Press.

- Fusar-Poli, P., Estradé, A., Stanghellini, G., Venables, J., Onwumere, J., Messas, G., … Maj, M. (2022). The lived experience of psychosis: A bottom-up review co-written by experts by experience and academics. World Psychiatry, 21(2), 168–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20959

- Gelfand, M. J., Caluori, N., Jackson, J. C., & Taylor, M. K. (2020). The cultural evolutionary trade-off of ritualistic synchrony. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1805), 20190432. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0432

- Griffiths, R. R., Hurwitz, E. S., Davis, A. K., Johnson, M. W., & Jesse, R. (2019). Survey of subjective “God encounter experiences”: Comparisons among naturally occurring experiences and those occasioned by the classic psychedelics psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca, or DMT. PLoS One, 14, e0214377.

- Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187(3), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5

- Grof, S. (1989). Spiritual emergency: When personal transformation becomes a crisis. Penguin.

- Guthrie, S. E. (1993). Faces in the clouds: A new theory of religion. Oxford University Press.

- Hagen, E. (2008). Non-bizarre delusions as strategic deception. In Elton, S., & O'Higgins, P. (eds) Medicine and evolution: Current applications, future prospect, (pp. 181–217). CRC Press.

- Hardy, A. (1979). The spiritual nature of man: A study of contemporary religious experience. Oxford University Press.

- Hartogsohn, I. (2016). Set and setting, psychedelics and the placebo response: An extra-pharmacological perspective on psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1259–1267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116677852

- Henrich, J. (2011). The birth of high gods how the cultural evolution of supernatural policing influenced the emergence of complex, cooperative human societies. Evolution, Culture, and the Human Mind, 119.

- Hoel, E. (2021). The overfitted brain: Dreams evolved to assist generalization. Patterns, 2(5), 1–15. 100244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2021.100244

- Hofmann, A. (2013). LSD: My problem child. Oxford University Press.

- Huang, M. K., Chang, K. S., Kao, W. F., Li, L. H., How, C. K., Wang, S. H., … Chiu, Y. H. (2021). Visual hallucinations in 246-km mountain ultra-marathoners: An observational study. Chinese Journal of Physiology, 64(5), 225–231. https://doi.org/10.4103/cjp.cjp_57_21

- Hunt, H. T. (2000). Experiences of radical personal transformation in mysticism, religious conversion, and psychosis: A review of the varieties, processes, and consequences of the numinous. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 21(4), 353–397.

- Hunt, H. T. (2007). “Dark nights of the soul”: Phenomenology and neurocognition of spiritual suffering in mysticism and psychosis. Review of General Psychology, 11(3), 209–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.11.3.209

- Imhoff, R., Dieterle, L., & Lamberty, P. (2021). Resolving the puzzle of conspiracy worldview and political activism: Belief in secret plots decreases normative but increases nonnormative political engagement. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619896491

- Jackson, M. (1997). Benign schizotypy? The case of spiritual experience. In G. Claridge (Ed.), Schizotypy: Implications for illness and health (pp. 227–250). Oxford University Press.

- Jaynes, J. (1976). The origin of consciousness in the breakdown of the bicameral mind. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Karl, J. A., & Fischer, R. (2018). Rituals, repetitiveness and cognitive load: A competitive test of ritual benefits for stress. Human Nature, 29(4), 418–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-018-9325-3

- Lang, M., Krátký, J., & Xygalatas, D. (2020). The role of ritual behaviour in anxiety reduction: An investigation of Marathi religious practices in Mauritius. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1805), 20190431. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0431

- Lang, M., Purzycki, B. G., Apicella, C. L., Atkinson, Q. D., Bolyanatz, A., Cohen, E., … Henrich, J. (2019). Moralizing gods, impartiality and religious parochialism across 15 societies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 286(1898), 20190202. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.0202

- Larøi, F., Thomas, N., Aleman, A., Fernyhough, C., Wilkinson, S., Deamer, F., & McCarthy-Jones, S. (2019). The ice in voices: Understanding negative content in auditory-verbal hallucinations. Clinical Psychology Review, 67, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.11.001

- Legare, C. H., & Souza, A. L. (2014). Searching for control: Priming randomness increases the evaluation of ritual efficacy. Cognitive Science, 38(1), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12077

- Luhrmann, T. M. (2017). Diversity within the psychotic continuum. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(1), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw137

- Luhrmann, T. M., Alderson-Day, B., Bell, V., Bless, J. J., Corlett, P., Hugdahl, K., … Waters, F. (2019). Beyond trauma: A multiple pathways approach to auditory hallucinations in clinical and nonclinical populations. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 45(Supplement_1), S24–S31. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby110

- Luhrmann, T. M., & Marrow, J. (Eds.). (2016). Our most troubling madness: Case studies in schizophrenia across cultures (Vol. 11). University of California Press.

- Luhrmann, T. M., Dulin, J., & Dzokoto, V. (2023). The shaman and schizophrenia, revisited. Culture, medicine, and psychiatry, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-023-09840-6

- Lukoff, D. (1985). The diagnosis of mystical experiences with psychotic features. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 17, 155–181.

- Lukoff, D. (2007). Visionary spiritual experiences. Southern Medical Journal, 100(6), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318060072f

- Lukoff, D. (2019). Spirituality and extreme states. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 59(5), 754–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167818767511

- Lyndon, S., & Corlett, P. R. (2020). Hallucinations in posttraumatic stress disorder: Insights from predictive coding. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(6), 534–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000531

- MacLean, K. A., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2011). Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(11), 1453–1461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881111420188

- McCarthy-Jones, S., & Longden, E. (2015). Auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder: Common phenomenology, common cause, common interventions? Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1071. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01071

- McCauley, R. N., & Graham, G. (2020). Hearing voices and other matters of the mind: What mental abnormalities can teach us about religions. Oxford University Press.

- McKay, R. T., & Ross, R. M. (2021). Religion and delusion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 40, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.10.002

- Murnane, K. S. (2019). Serotonin 2A receptors are a stress response system: Implications for post-traumatic stress disorder. Behavioural Pharmacology, 30(2–3), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0000000000000459

- Murray, E. D., Cunningham, M. G., & Price, B. H. (2012). The role of psychotic disorders in religious history considered. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 24(4), 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11090214

- Noury, A., & Roland, G. (2020). Identity politics and populism in Europe. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(1), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-033542

- Ortiz-Orendain, J., Gardea-Resendez, M., Castiello-de Obeso, S., Golebiowski, R., Coombes, B., Gruhlke, P. M., … McKean, A. J. (2023). Antecedents to first episode psychosis and mania: Comparing the initial prodromes of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in a retrospective population cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 340, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.106

- Osmond, H. (1957). A review of the clinical effects of psychotomimetic agents. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 66(3), 418–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1957.tb40738.x

- Parnas, J., & Henriksen, M. G. (2016). Mysticism and schizophrenia: A phenomenological exploration of the structure of consciousness in the schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Consciousness and Cognition, 43, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.05.010

- Parnas, J., Yttri, J. E., & Urfer-Parnas, A. (2023). Phenomenology of auditory verbal hallucination in schizophrenia: An erroneous perception or something else? Schizophrenia Research, 265, 83–88.

- Perry, J. W. (1977). Psychosis and the visionary mind. Journal of Altered States of Consciousness, 3, 5–14.

- Polimeni, J. (2012). Shamans among us: Schizophrenia, shamanism and the evolutionary origins of religion.

- Polimeni, J. (2022). The shamanistic theory of schizophrenia: The evidence for schizophrenia as a vestigial phenotypic behavior originating in Paleolithic shamanism.

- Polimeni, J., & Reiss, J. P. (2002). How shamanism and group selection may reveal the origins of schizophrenia. Medical Hypotheses, 58(3), 244–248. https://doi.org/10.1054/mehy.2001.1504

- Powers, A. R., & Corlett, P. R. (2018). Shamanism and psychosis: Shared mechanisms? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 41. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1700214X

- Preller, K.H., & Vollenweider, F.X. (2016). Phenomenology, Structure, and Dynamic of Psychedelic States. In: Halberstadt, A.L., Vollenweider, F.X., Nichols, D.E. (eds) Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, vol 36. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2016_459

- Roes, F. L., & Raymond, M. (2003). Belief in moralizing gods. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00134-4

- Ross, R. M., & McKay, R. (2018). Shamanism and the psychosis continuum. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

- Rossano, M. J. (2012). The essential role of ritual in the transmission and reinforcement of social norms. Psychological Bulletin, 138(3), 529–549. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027038

- Ruck, C. A. P., Bigwood, J., Staples, D., Ott, J., & Wasson, R. G. (1979). Entheogens. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 11(1–2), 145–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1979.10472098

- Rutjens, B. T., Sengupta, N., Der Lee, R. V., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., Martens, J. P., Rabelo, A., & Sutton, R. M. (2022). Science skepticism across 24 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(1), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211001329

- Sass, L., Pienkos, E., Skodlar, B., Stanghellini, G., Fuchs, T., Parnas, J., & Jones, N. (2017). EAWE: examination of anomalous world experience. Psychopathology, 50(1), 10–54. https://doi.org/10.1159/000454928

- Samson, D. R., Clerget, A., Abbas, N., Senese, J., Sarma, M. S., Lew-Levy, S., … Perogamvros, L. (2023). Evidence for an emotional adaptive function of dreams: A cross-cultural study. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 16530. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43319-z

- Shalev, A. Y. (2002). Acute stress reactions in adults. Biological Psychiatry, 51(7), 532–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01335-5

- Shults, F. L. (2022). Studying close entity encounters of the psychedelic kind: Insights from the cognitive evolutionary science of religion. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 33(4), 1–15.

- Singh, M., Kaptchuk, T. J., & Henrich, J. (2021). Small gods, rituals, and cooperation: The Mentawai water spirit Sikameinan. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.07.008

- Sperber, D., Clément, F., Heintz, C., Mascaro, O., Mercier, H., Origgi, G., & Wilson, D. (2010). Epistemic vigilance. Mind & Language, 25(4), 359–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2010.01394.x

- Spittles, B. (2023). Better understanding psychosis: Psychospiritual considerations in clinical settings. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 63(2), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820904622

- Taylor, S. (2022). When seconds turn into minutes: Time expansion experiences in altered states of consciousness. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 62(2), 208–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820917484

- Thunström, L., Jones Ritten, C., Bastian, C., Minton, E., & Zhappassova, D. (2021). Trust and trustworthiness of Christians, Muslims, and atheists/agnostics in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 60(1), 147–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12692

- Tipton, M., & Montgomery, H. (2022). The experience of drowning. Medico-Legal Journal, 90(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/00258172211053127

- Van Lommel, P., Van Wees, R., Meyers, V., & Elfferich, I. (2001). Near-death experience in survivors of cardiac arrest: A prospective study in the Netherlands. The Lancet, 358(9298), 2039–2045. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07100-8

- Van Ommen, M. M., van Laar, T., Cornelissen, F. W., & Bruggeman, R. (2019). Visual hallucinations in psychosis. Psychiatry Research, 280, 112517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112517

- Waters, F., Chiu, V., Atkinson, A., & Blom, J. D. (2018). Severe sleep deprivation causes hallucinations and a gradual progression toward psychosis with increasing time awake. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 303. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00303

- Waters, F., Collerton, D., Ffytche, D. H., Jardri, R., Pins, D., Dudley, R., … Larøi, F. (2014). Visual hallucinations in the psychosis spectrum and comparative information from neurodegenerative disorders and eye disease. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 40(Suppl_4), S233–S245. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu036

- White, C. J., Kelly, J. M., Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2019). Supernatural norm enforcement: Thinking about karma and God reduces selfishness among believers. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 84, 103797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.03.008

- Whitehead, P. M. (2016). The runner’s high revisited: A phenomenological analysis. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 47(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691624-12341313

- Wießner, I., Falchi, M., Palhano-Fontes, F., Feilding, A., Ribeiro, S., & Tófoli, L. F. (2023). LSD, madness and healing: Mystical experiences as possible link between psychosis model and therapy model. Psychological Medicine, 53(4), 1151–1165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721002531

- Willard, A. K., & Norenzayan, A. (2017). “Spiritual but not religious”: Cognition, schizotypy, and conversion in alternative beliefs. Cognition, 165, 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.05.018

- Wood, C. (2017). Ritual well-being: Toward a social signaling model of religion and mental health. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 7(3), 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2016.1156556

- World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). WHO Press.

- Xygalatas, D. (2014). Cognitive science of religion. Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion, 2, 343–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6086-2_9261

- Xygalatas, D. (2022). Extreme rituals. In Barrett, L. (ed). The Oxford handbook of the cognitive science of religion (pp. 237). Oxford University Press.

- Xygalatas, D., Khan, S., Lang, M., Kundt, R., Kundtová-Klocová, E., Krátký, J., & Shaver, J. (2019). Effects of extreme ritual practices on psychophysiological well-being. Current Anthropology, 60(5), 699–707. https://doi.org/10.1086/705665

- Yaden, D. B., & Newberg, A. (2022). The varieties of spiritual experience: 21st century research and perspectives. Oxford University Press.

- Yung, A. R., & McGorry, P. D. (1996). The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: Past and current conceptualizations. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 22(2), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/22.2.353