ABSTRACT

Why do people pray? In this paper, we suggest another important dimension of prayer, namely that prayer is a form of collaborative problem solving. In this paper, we use both qualitative evidence drawn from interviews and quantitative evidence from a survey and an experiment to show that people use prayer to solve practical problems in their lives. We also argue that the informal and personal ways in which people address God in prayer put God into the role of collaborator in their problem solving. This paper argues that not only do people solve practical problems in prayer, but also that there is a training effect of prayer—namely that with experience, prayer is perceived to be more efficacious as a problem-solving process.

1. Introduction

Most Americans pray. In 2008, about 55 percent reported praying daily and 78 percent reported praying at least sometimes (“Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics”, Citation2022). Those who pray often experience God to some extent as a person, and prayer as an interaction with that person. That is, of course, true for many contemporary Christians, but it is true for many people in other faiths as well (Haeri, Citation2013; Lienhardt, Citation1961; Luhrmann, Citation2012, Citation2020). Prayer for them often involves being quiet, clasping hands, shutting eyes, and talking to this person in one’s mind with the idea that a response will come from this person—in the form of a thought, a sign, or something more dramatic.

Why do people pray? The first Gallup poll to ask about prayer in 1988 found that of the nearly 9 in 10 people who prayed, there were a variety of responses. But nearly half made requests for material things. Almost all of them said that they talked directly and informally to God (Poloma & Gallup, Citation1992, p. 26). These data suggest that people pray to ask for things and to communicate with God.

Secular observers have assumed that people pray because they want material goods and that the request is possible because of reciprocity between the worshiped and the worshiper. We give prayers to the gods, and they give goods to us. That was Robertson-Smith’s argument: that sacrifice is a communal meal in which humans and gods created bonds of obligation to each other (Smith, Citation1927, p. 27). To early anthropologists, prayer enabled people to manage their luck and control an unpredictable world (Frazer & Frazer, Citation1922; Malinowski, Citation2014).

Modern anthropologists point out that prayer is a “genre.” To call prayer a genre means that someone within that “genre community” who hears or sees another person pray would instantly recognize the behavior as prayer. One might describe the prayer genre within an American family as including a distinct set of body postures (being seated, head bowed, eyes closed); an expectation of quiet voice and quiet behavior while in the posture (“throwing hands aren’t praying hands”) (Luhrmann, Citation2012); a verbal act of request, praise, and thanks to a being called God; and at the end, a verbal marker: “Amen” (Capps & Ochs, Citation2002). Often, these genres are marked by specific linguistics structures that indicate that this action, this use of words, is intended to speak beyond the human (Csordas, Citation1987; Keane, Citation1997; Shoaps, Citation2002). Anthropologists have described the practice as narrative sense-making (Baquedano-Lopez, Citation1999). Some have argued that prayer involves a costly signal to other humans (Ruffle & Sosis, Citation2007; Watson-Jones & Legare, Citation2016). Some have argued that prayer offers a way to manage inner anxiety as an action that allows people to decrease stress under uncertainty (Sosis & Handwerker, Citation2011) and a metacognitive process to diminish anxiety (Luhrmann, Citation2020). Modern scientific investigations also show that prayer can have social and physiological benefits, such as making people healthier, happier, more resilient, and more social (Lueke et al., Citation2021; Reis & Menezes, Citation2017; Van Cappellen & Edwards, Citation2021; Xygalatas et al., Citation2013).

In this paper, we suggest another important dimension of prayer, namely that prayer can be a form of collaborative problem solving. A problem includes a problem state and a goal state, which are—importantly—different. A problem that needs solving also requires a set of operators and an unclear path from the problem state to the goal state (Newell et al., Citation1959). Contemporary Christians pray about their problems, and the culture of Christian prayer provides rules for praying about problems. Prayer, like problem solving, has been shown to be a skill that can be developed over time through practice (Luhrmann, Citation2012, Citation2020; Luhrmann et al., Citation2013). We add to this argument the observation that the skill is often applied to solving problems—often, quite explicitly. People use prayer to move from a problem state to a goal state, and thus to effect a change in their inner understanding of a practical issue that they face.

In this paper, we use both qualitative evidence drawn from interviews and quantitative evidence from a survey and an experiment to show that people use prayer to move from a problem state to a goal state and that the “operators” of prayer are well suited to do this. We also argue that the informal and personal ways in which people address God in prayer put God into the role of collaborator in their problem solving. We argue that not only do people solve practical problems in prayer, but that part of the skill being developed in prayer is collaborative problem-solving. The studies in this paper test the validity of the three following hypotheses: (1) People use prayer to solve practical problems in their lives, (2) God is perceived to be a collaborator in their problem-solving process, and (3) With age and experience, prayer is perceived to be more efficacious as a problem-solving process.

1.1. Overview

To understand how people collaboratively solve problems in prayer, we needed to closely observe people praying. But to understand the causal impact of prayer as a specific vehicle for problem-solving, we could not stop at observation. Therefore, this paper describes three interventions with people who pray frequently: A protocol analysis, a survey, and an experiment.

The purpose of the protocol analysis was to naturalistically identify cognitive strategies that people employ during prayer. Participants’ verbal reports illustrate that they engage in complex, multi-step strategies that can be mapped onto classic problem solving frameworks. The survey shows that the problem-solving behaviors identified in the protocol analysis are present in a wider sample of prayer practitioners. The experiment compared prayer to a similar problem-solving method (thinking-aloud) along several measures. It shows ways in which prayer practitioners use the affordances of prayer as a problem-solving behavior and suggests that prayer experience is a skill that can be developed.

2. Protocol analysis

Observations of problem solving in prayer began by interviewing prayer practitioners and carefully querying their thought processes during prayer. We did this following in the tradition of the protocol analysis, a rigorous methodology for eliciting verbal reports of thought sequences (Austin & Delaney, Citation1998; Ericsson & Simon, Citation1984). The purpose of this protocol analysis was to naturalistically identify cognitive strategies and mechanisms that people employ during prayer—to see in action how prayer works in the mind and how prayer affects the mind.

2.1. Methods

ESH conducted interviews with 16 prayer practitioners. All participants were self-identified Christians with regular prayer practices. The ages of participants ranged from 21 to 79 with a mean age of 38.7 and a median age of 33.5. There were nine women, six men, and one non-binary person. All interviews took place over Zoom in the winter of 2021–2022.

All interviews followed the same script. The script began with introductory questions (age, gender, etc., see Appendix for full list of questions). Next, participants were asked to engage in a “warm-up” prayer. The purpose of the warm-up prayer was to make the participant more comfortable praying aloud in front of someone on Zoom. After this first prayer, participants were given a series of two flexible prayer prompts. The first of these was:

Can you think of an issue or situation that you’ve been going through lately? Can you please pray aloud as you normally would about it?

The second prayer prompt was similar but asked about a situation facing the participant’s community. Both case studies presented in this paper are drawn from the prayers in response to the first prompt.

As the participant prayed, ESH took down a transcript of their prayer using the Microsoft dictate function. After each prayer prompt, the participant and ESH engaged in a protocol analysis (Ericsson & Simon, Citation1984). Using Zoom, ESH shared her screen so that they were able to view the text of their prayer. Participants then went through their own prayer, line by line, and reported what they had been thinking during each moment of their prayer.

At the end of each interview, there were final questions about the participant’s prayer practice and process (see Appendix for full list of questions). All interviews took approximately 1 hour.

2.2. Case studies

Despite being of different lengths, having different emotional affects, and being about a variety of topics, participants’ prayers followed similar structures that map onto a classic four-step problem-solving structure (Polya, Citation2004). Polya suggests that to solve a (mathematical) problem you must (1) Understand the problem, (2) After understanding, make a plan, (3) Carry out the plan, and (4) Reflect on the work. How could it have gone better? To analyze prayer in more detail, consider two prayer case studies. Each case study shows a prayer from a participant (lightly edited for clarity) and then breaks down that prayer into its problem-solving components.

Here is participant AnnieFootnote1:

I’d like to lift up [my cat] Callie to your attention. I pray that you will be with her and help her communicate any pain she’s having because I know that cats can hide that. I pray that you give me the insight to be able to know if you’re giving me signs through her (or if she’s trying to give me signs), and the wisdom to understand what to do and when to take her to a vet if I need to. I ask that you help her with her pain levels … her arthritis maybe … and that if she is asking to play a bit more that you make that more obvious. Help me find out what she wants to do, whether or not she’s fine sleeping all day, or if she is actively wanting to play and I just haven’t found the right thing to get her to exercise yet. I pray that you help me find where I can accommodate her better, if there’s something that’s causing her pain in the apartment, that I can find it and help her deal with that, whether that’s allergies, or her bowl is too low, or something. So, if you would just help her communicate and help me understand that would be ideal. And help her know that I love her. Amen.

And participant Paul:

God, I want to thank you for the gift of each morning, of the sun rising, my eyes opening, and myself waking up from sleep every day. It’s great to wake up and great to have the prospect of a new day ahead of me. But God, as much as I thank you for these things, I need your help as well for me. As you know, these mornings are tricky times. They are times swirling with angst and concern and anxiety and some confusion. It’s a finding of a new routine, especially after a crazy couple weeks to now be settling into things. To feel like I’m finding the ways to meet you in the morning can be really important for me to start my day. You know this, and over these next few days, I ask for your help to find those routines in the mornings and those things that can get me up and get me out of bed. We’ve had those things before, and it’s just a matter of finding whatever the new way we’re meeting each other is in the mornings now. It would be most helpful for me, and I know we can do it, but it’s something I need your help with right now. All this we ask through your son, Jesus Christ, Amen.

2.2.1. Prayer as problem solving

Like nearly all participants, Annie begins her prayer by describing the problem she is facing. Coding the prayer transcripts for this, we found that 14 out of 16 participants began their prayers by describing the problem they were facing. Annie clearly communicates that her cat is having health problems and that she does not know exactly what is wrong nor how to help Callie the cat. Many participants, in fact, spoke explicitly about the need to articulate the problem they were facing in their prayers, even though they believe that their God is all-knowing (and so is already familiar with their problems). This may seem unnecessary if viewing prayer as only a statement of belief or a request for goods, but becomes more intelligible when thinking about it as the first step in solving a problem: understanding the problem (Polya, Citation2004).

The same is true for Paul:

Naming problems is half of the battle and finding the right words to do that is often helpful. [But] if you address something too directly, you haven’t really adequately named it. It’s too efficient of a process. I think it’s gotta be kind of winding.

In general, participants first described the problem they were facing, and then would take a variety of tactics that can be understood to be the second step of problem solving: making a plan (Polya, Citation2004). In Polya’s original context of solving open-ended math problems, strategies for planning include making an orderly list, looking for a pattern, and working backwards. Participants’ prayers showed evidence of similar problem-solving strategies, including search and means-ends analysis: tracing a path from the goal state back to the current problem state (Simon & Newell, Citation1971).

Annie has clearly, if implicitly, communicated the goal state of her problem in her prayer, namely that Callie the cat gets what she needs. Annie comes up with a means-ends plan to get from the current problem state—Callie’s mysterious health problems—to the goal state. Annie prays for insight so that Callie might communicate with Annie what is wrong, and that Annie might understand what is wrong so she can help her cat. Annie engages in a search to find the correct source of her cat’s possible ailment. Concretely, she comes up with a list of hypotheses of what may be ailing her cat (arthritis; not playing/exercising enough; sleeping too much; unidentified source of pain; allergies; bowl too low).

Similarly, Paul begins his prayer by identifying the problem-state that “mornings are tricky times” for him. He also identifies the goal state—that he wants to feel happy and not anxious in the mornings. He creates a means-ends plan, saying that he wants to “find ways to meet [God] in the mornings” and works backward to determine that he needs to find a new morning routine. This was true for most participants.

Participants reflected on the efficacy of their plans and problem-solving, both within the bounds of their prayers and in the following protocol analysis. In this way, they followed the fourth and final step of problem-solving: looking back on their work and asking how it could be better (Polya, Citation2004). Participants showed different strategies for reflection. Some, like Paul, identified past successes or positive experiences, saying “We’ve had those [morning routines] before, and it’s just a matter of finding whatever the new way we’re meeting each other is in the mornings now.” Other participants, like Annie, would remark after praying during the protocol analysis that the prayer itself was useful to them saying, “I feel a little bit better. I feel like I did something. At least it helps me order my thoughts. Sometimes I’ll notice something that I wasn’t worried about, or that I didn’t know I was worrying about.” Some, like participant Glenn, reflected on anxieties or past problems, saying,

I feel the passage of time and I struggle to not worry about the future so Michael and I never had children and I wonder what will happen to one or both of us if we become really old and infirm.

Prayer pulls apart from Polya’s (Polya, Citation2004) four-step method in the third step: carrying out the plan. Prayer often follows the format of problem representation construction and making a plan. People report that plans do get carried out, but often outside the bounds of prayer. For example, in a story from participant Rachel, she reported that praying about a difficult person who would show up to her Bible study often changed the way she thought about the person, which led to a better interaction.

2.2.2. Prayer as collaborative problem solving

Annie and Paul’s prayers illustrate that prayer practitioners are not only solving problems in prayer but that they are engaging in a kind of collaborative problem solving with God. Collaborative problem solving, according to Graesser et al., Citation2018 requires four things: (1) that a group has a goal of solving a novel problem, (2) the quality of the solution can be evaluated during problem solving and is visible to team members, (3) there is a differentiation of roles among the team members who take on different tasks, and (4) that there is interdependency among team members. Participants experience God as a social other in prayer, imagine themselves in collaboration with God, and approach problems together. We found that 13 out of 16 participants showed signs of engaging in collaborative problem solving with God. When we coded participants’ prayer transcripts for collaboration, we did not count direct requests that God act, like when interviewee Ben asked that “in Jesus’ name you heal my grandma.” But rather, we looked for signs of task division and interdependence like Ben showed later in that same prayer when he asked God “to make clear to me any way that I can support my family.” While God, according to Christian theology, certainly has the power to do anything, Ben is required in this case to carry out the action of Ben comforting his family. This is a common version of the “interdependency among team members” present in collaborative problem solving with God. The prayer practitioner believes that they cannot solve the problem without God’s help and guidance and that God needs them (or requires them or uses them) to carry out the physical tasks required on earth to solve the problem.

Collaborative problem solving requires a group to have a goal of solving a novel problem by formulating a plan to move from a starting state to a goal state when no routine plan or script is available (Mayer & Wittrock, Citation2006; Simon & Newell, Citation1971). In the case of a single person’s prayer, the group is that person and God. This is an unusual instantiation of the category “group.” Depending on one’s ontology, this “group” could be viewed as a solo person’s imagination (depending on whether some God is deemed real). But for the prayer practitioner, God is real, and so God is experienced as a member of a group. Adopting the phenomenological approach of bracketing ontology (Husserl, Citation2002) and taking the prayer practitioner’s experience seriously, that practitioner experiences herself to be in a group with God and so we can view her as part of an (admittedly unorthodox) group. The category of “group” here does not require that the prayer practitioners are on equal footing or of equal status. Even those who perhaps view God as “superior protector” rather than “familiar other” are conversationally addressing God, making appeals of God, and entering into shared work with God.

3. Survey

We then developed a survey based on these sixteen in-depth interviews. Each participant responded to a 36-item survey tool, which probed their prayer background, prayer practices, and experiences of problem-solving during prayer. The survey asked questions about different aspects of problem-solving, following Polya’s (Polya, Citation2004) general structure with questions about how people understand the problem they are praying about, how they plan to tackle the problem, how they execute that plan, and how they reflect back on the problem-solving process. (See Appendix for full list of survey instruments.)

3.1. Methods

ESH collected survey responses from 200 participants. It was important that participants be Christian and regular prayer practitioners, so they were recruited by e-mail from churches and prayer groups around the United States. Out of these, 45 did not finish the survey, and 4 reported praying “never,” and were thus removed from all analyses, leaving 151 participants. These remaining participants reported praying spontaneously on their own at least once per month. The mode of participants (N = 70) prayed multiple times per day.

The full set of survey items took participants a median of 7.4 minutes to complete. Subjects participated on a voluntary basis.

3.1.1. Participants

Out of the 151 participants, 105 were women, 1 was non-binary, and the remaining 45 were men. The average age of participants was 47.4. The age range was large, spanning from 20 to 93 in a bimodal distribution with peaks at around 25 and 55. Participants were primarily regular churchgoers with 77.4% of participants going to church at least weekly and 89.4% going to church at least once a month. The majority of participants prayed spontaneously at least once a week and 68.9% strongly agreed that prayer was an important part of their lives, with only five participants disagreeing or strongly disagreeing.

Participants showed some diversity in their specific prayer practices. Twenty-nine participants prayed aloud half the time or more, while 115 prayed aloud sometimes or never. Participants also varied in the proportion of the time that they recited or read their prayers (as opposed to spontaneously generating them). Participants had received different amounts of prayer instruction (most saying some, with 17 receiving a great deal and 9 none). Participants also described different prayer practices with some praying before meals, praying before bed, sporadically throughout the day, finding a quiet moment here and there, while others described their prayer involving singing along to Christian songs on the radio, meditation with a lit candle, doing a rosary, etc.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Prayer as problem solving

In general, responses indicated that participants believe that they use prayer to solve problems in their lives. Here are some beliefs:

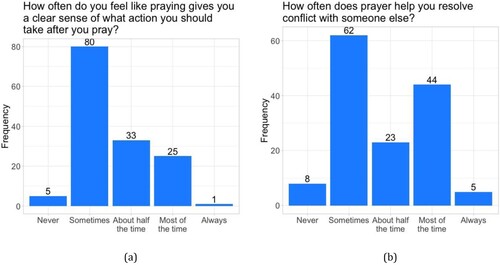

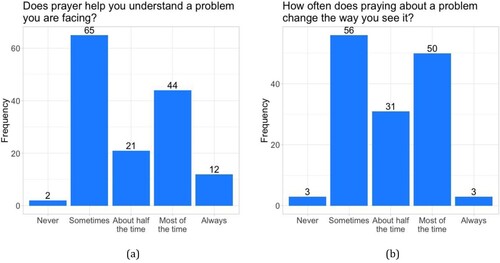

Prayer helps them understand problems: In response to the question “Does prayer help you understand a problem you are facing?” only two participants responded “Never,” and 44 participants said that prayer helps them understand a problem they are facing most of the time ((a)).

Figure 1. (a) Distribution of responses to question “Does prayer help you understand a problem you are facing?”; (b) Distribution of responses to question “How often does praying about a problem change the way you see it?”

Prayer can change their perspective on a problem: All but three participants reported that prayer at least sometimes changes the way they see a problem with 50 reporting that it does most of the time ((b)).

Prayer also helps them make a plan: 80 participants felt like prayer gave them a clear sense of action to take sometimes, while only five said never ((a)). A majority (n = 102) of participants also reported that prayer makes them feel more motivated to tackle a problem in their lives at least half the time. Participants reported that prayer directly leads to the solutions to problems: 146 participants reported that prayer helps them resolve conflict with someone else at least sometimes ((b)).

3.2.2. Prayer as collaborative problem solving

Responses to additional survey measures were consistent with observations in earlier interviews. They indicated that participants were approaching prayer as a collaborative problem-solving process with God.

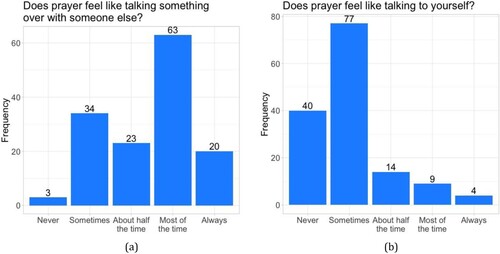

Participants indicated that prayer felt social to them. For example, when asked “Does prayer feel like talking something over with someone else?” 63 participants responded “most of the time” and only 3 responded “never” ((a)). However, it is worth noting that people can have a variety of experiences on this front: many (n = 40) participants reported that prayer never feels like talking to themselves and many (n = 77) reported prayer feels like talking to themselves sometimes ((b)).

Figure 3. (a) Distribution of responses to question “Does prayer feel like talking something over with someone else?”; (b) Distribution of responses to question “Does prayer ever feel like talking to yourself?”

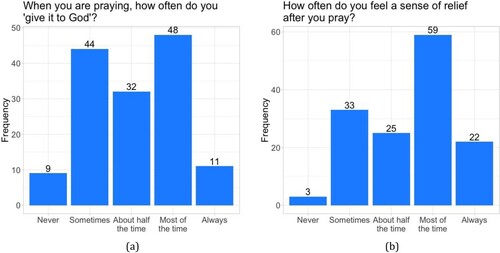

Participants reported a kind of delegation process with God. In response to the question “When you are praying, how often do you ‘give it to God'—i.e., relinquish responsibility over the problem (or parts of the problem) you are praying about?” only nine participants responded “never,” while over a third of participants (n = 59) responded “most of the time” or “always” ((a)).

Figure 4. (a) Distribution of responses to question “When you are praying, how often do you “give it to God”—i.e., relinquish responsibility over the problem (or parts of the problem) you are praying about?”; (b) Distribution of responses to question “How often do you feel a sense of relief after you pray?”

Participants also responded to survey measures in ways that indicated that they felt helped by God through prayer. Over half (n = 81) of participants feel a sense of relief after praying most of the time or always ((b)). And 49 participants reported that most of the time prayer made them feel optimistic that there was some kind of constructive solution to the problem they were praying about.

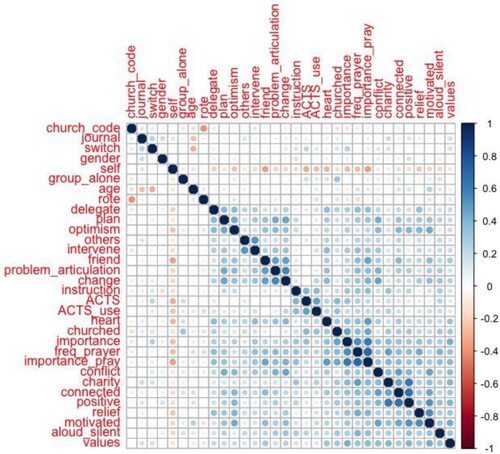

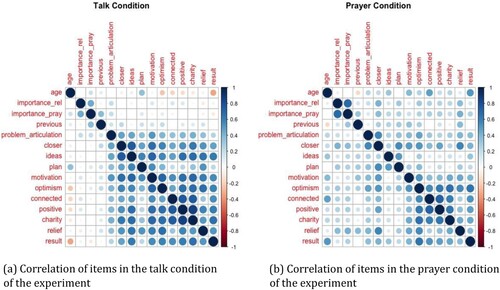

3.2.3. Relationships between items

We looked for further insight into participants’ behaviors by analyzing the relationship between survey items. Broadly, we found that the items are related and form an interesting coherent picture. The correlation structure of all the survey items showed that problem-solving measures are correlated with one another. For example, better understanding a problem as a result of prayer (problem articulation) is highly correlated with prayer giving a clear sense of what action to take after praying (plan) as well as prayer changing the way participants see the problem (change). Not only are problem-solving measures correlated with one another, but they are also correlated with other measures of religiosity. For example, better understanding a problem as a result of prayer is highly correlated with how frequently participants prayed and how important they reported prayer to be to them. (For a plot of the correlation as well as full aggregated survey response results, see Appendix B.)

We also examined the correlation between problem-solving measures and participant demographics. We do find a strong negative correlation between participants’ responses to the measure “Does prayer ever feel like talking to yourself?” and nearly all other measures. However, we find no significant or noteworthy correlations between any of the problem solving-measures (i.e., problem articulation, making a plan, delegating, changing perspective on the problem, clear sense of what action to take) and any demographics (e.g., denomination, age, and gender). We take this lack of correlation to suggest that problem solving in prayer is not reserved for one particular group but used across ages, genders, and denominations of Christians.

The correlation structure suggests that the more one prays, the more one problem solves in prayer. This pattern is supported by factor analysis. Both a principal component analysis (PCAFootnote2, full results shown in Appendix B) and an exploratory factor analysis (EFAFootnote3). In both cases, we retained two factors, however, the first factor accounts for much more of the variance (about 25%), while the second factor accounts for less (only about 7%). The factor loadings in the PCA and EFA show that both measures of religiosity (e.g., prayer is an important part of faith life, frequency of prayer) and problem-solving measures (e.g., prayer helps resolve conflict, praying about a problem changes one’s perspective, and prayer helps understand a problem) strongly load onto the first factor. The second factor most strongly (negatively) loads onto whether they have heard of the ACTS model of prayerFootnote4. This second factor seems to capture something like the role of formal or cultural instruction on prayer.

A further confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) found that a model where the two latent variables accounting for participants’ responses are religiosity and problem solving had a poor fit (The Chi-square was significant p < 0.001, and the CFI was low (0.694) and the RMSEA was high (0.094).) This result, along with the PCA and EFA results that show both religiosity and problem solving load onto the primary factor suggests that it is difficult to tease apart problem-solving from wider prayer behaviors. Our takeaways from the relationships between items in the survey are that religiosity and problem-solving in prayer are related (highly correlated and load onto the same factor) and it is not simply demographics (age or denomination affiliation) driving this relationship.

4. Experiment

If prayer is indeed not only a problem-solving strategy, but a collaborative problem solving strategy, then we should be able to find markers of the collaborative nature of that process when contrasting to a non-collaborative problem-solving strategy like think-aloud. We have hypothesized that collaborative problem-solving with God entails a kind of task division and delegation, determining which parts of the conflict are within the practitioner’s control and which are not. The parts that are determined to be out of the practitioner’s control are then delegated to God. The protocol analysis indicated prayer often includes important metacognitive monitoring and regulation tasks, including the task of finding creative solutions and maintaining a constructive, solution-oriented mindset. The survey suggests that people feel that prayer successfully plays these roles. We hypothesize that people are more or less functionally correct about these contingencies, and therefore that prayer will tend to increase these metacognitive processes.

We therefore conducted an experiment to explore this question: how does prayer as a problem-solving process compare to a similar problem-solving process?

4.1. Methods

The experiment had two conditions: a prayer condition and a think-aloud condition. Participants were randomly assigned to either pray about a person who was difficult for them or to think aloud about a person who was difficult for them. The prayer prompt text was the following:

I would like you to think about a person who is difficult for you or that you have some conflict with. Maybe it’s a person who disagrees with you on an important issue, or maybe is just a person who gets on your nerves.

I would like you to get into the mode where you’re praying about a person who is like this for you in your life. There’s no need to tell me their name. Maybe like how you pray when you are alone or in the shower. I want you to do that. In this case, so I can observe your process, I’d ask you to pray aloud. Feel free to pray however you normally would, whatever that looks like for you. I’m interested in your process. Don’t worry about time, if I need to I’ll cut you off.

The think-aloud condition was kept identical except for replacing the “praying” words with “thinking” words.

Participants’ prayers or thoughts, depending on the condition, were recorded in a written transcript using the Microsoft Word dictate function. Participants were then asked to complete a survey, hosted on Qualtrics. Participants responded to each question by dragging a continuous slider marked from “Strongly disagree” on the left to “strongly agree” on the right. For analysis, we treated their response as a value ranging linearly from 0 to 100. For a full list of questions in the survey, see the Appendix.

4.1.1. Participants

ESH recruited and interviewed participants (N = 100) using a snowball sampling method beginning with seed churches in Bloomington, IN and Bellingham, WA. Participants were recruited by sending out requests for participation to churches and Christian-affiliated groups, including prayer groups and Christian-focused Facebook groups. Participants were all adult, self-identified Christians who prayed of their own volition at least occasionally. Participants signed up for a 15-minute Zoom call.

There was a wide age range in the subject population. The youngest participant was 18 and the oldest was 95. Age was positively skewed, with a peak around age 25 and a median age of 43 (mean age of 45.12).

Out of 100 participants, 67 were women, 32 were men, and 1 was non-binary. When broken into conditions, the approximate ratio of 2:1 women:men heldFootnote5 ().

Table 1. The breakdown of Christian denomenation types in the experiment sample with how many participants were in each group.

These participants were people whose lives are deeply shaped by their religious practice and their belonging to a Christian community. Three quarters of all participants attended church at least once a week, with 51% attending “once per week” and 24% attending “more than once a week.” Only 10% of participants attended church once per month or less. Several participants were employed by or volunteered for their church in some capacity.

One should note that the range of Christian denominations participants described as their own does not reflect the diversity present in the United States. Nevertheless, the participants represented common forms of Christianity in the US. Besides five Catholics and one participant who said “the world is my church,” every participant was Protestant. Out of these, 50 were either Episcopalian or Anglican. Another 18 went to some kind of mainline Protestant church (6 Lutheran, 6 Presbyterian, 6 unspecified). Twenty attended a non-denominational Evangelical church and six a Baptist one.

Because we participants were recruited using snowball sampling and because we have participants’ denomination affiliation, we calculated an intraclass correlation coefficient between groups for participants in the prayer condition. The ICC value here describes the total amount of variance in the participant responses that is due to between-group rather than within-group differences. That is, an ICC addresses the potential issue of the nested data structure present here. The ICC on an averaged measure of participants’ responses where the groups in question were Catholic, Episcopal, Evangelical, and Mainline Protestant (the groups present in the prayer condition participants) was 0. We also calculated the ICC of each individual measure, the largest of which was 0.091 for the measure “I have new ideas or a new plan for how to solve this conflict with this person going forward.” This means that roughly 9% of the variance present in responses to that measure can be attributed to between-group differences. These low ICC values give us confidence that the nested structure of the data does not present empirical issues for the analysis and interpretation of results.

Participants’ responses indicated that their faith/religion/spirituality is very important to them—the mean response to this measure was 90.77. Participants also prayed frequently, with two-thirds of participants praying at least daily. Participants also responded that prayer is an important part of their faith lives. Over a third (37%) of participants responded with a maximum score of 100.

Participants were asked to what extent they “have prayed about this particular situation before.” This was asked of participants in both conditions to control for the effect of previous prayer about a conflict. The distributions of responses to this question in each condition were very similar.

4.2. Results

We describe the results of the experiment grouped into 3 categories: problem-solving measures, collaborative problem-solving measures, and values measures. These three categories capture the pattern of results found throughout the protocol analysis and the survey. Using Cronbach’s alpha, we also find that these categories are reliable (problem-solving α = 0.78, collaborative problem-solving α = 0.81, values α = 0.89). A confirmatory factor analysis also supports these distinctions as reasonable (Chi-square = 75.67 (p = 0.001), CFI = 0.946, RMSEA = 0.092, SRMR = 0.069).

4.2.1. Problem-solving measures

We found no difference in responses between conditions on problem-solving measures related to understanding the problem and making a plan. Specifically, for the measures “I understand the situation I am facing better as a result of praying about it,” “I have new ideas or a new plan for how to solve this conflict with this person going forward,” and “I have a clear sense of what action I should take in this conflict with this person going forward,” A Bayesian t-test, BEST (Kruschke, Citation2013), shows little to no difference between the prayer and thinking aloud conditions for all of these measures. For all three of these measures, the 95% high-density interval (HDI) in the posterior distribution of differences between conditions contained 0. The 95% HDIs were [−2.73–19.8] for understanding the problem, [−1.68–21.1] for new ideas, and [−11.1–12.6] for what sense of action to take. The maximum possible difference is 100 and the minimum possible difference is −100.

However, in response to the measure “I am closer to solving the conflict with this person,” BEST found a mean difference of the means from the two conditions in the posterior distributions of 14.7 (95% HDI 3.58–25.9). Participants who prayed felt closer to solving the conflict with the person they prayed about than participants who talked aloud.

We found consistent results when analyzing problem-solving measures as a multiitem measure. When we analyze the difference of the mean of all problem-solving measures, BEST also shows little to no difference between the prayer and thinking aloud conditions, with a mean difference of means of 8.23 and an effect size of 0.38 (95% HDI −0.703–17).

4.2.2. Collaborative problem-solving measures

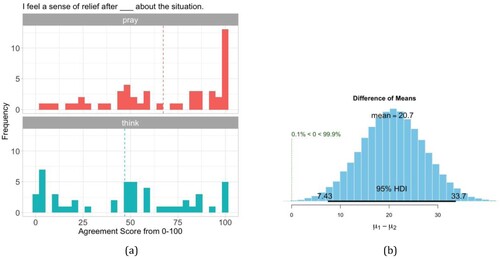

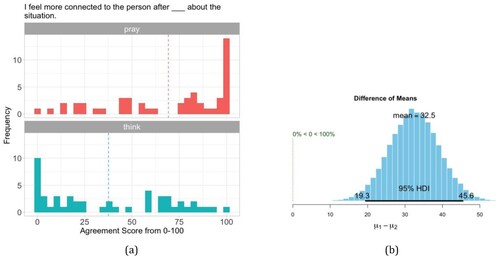

When it came to measures that were related to collaboration or Christian values, there were striking differences between conditions. Participants in the prayer condition were much more likely to highly agree that “I feel a sense of relief after praying/thinking about the situation.” ((a)). A Bayesian t-test posterior distribution shows a mean difference of 20.7 (95% HDI 7.43–33.7), with an estimated effect size of 0.64 ((b)).

Figure 5. (a) Distribution of participant responses to statement “I feel a sense of relief after praying/thinking about the situation.” Dashed lines show the median response for each condition. (b) Posterior distribution of differences of means between conditions from BEST on relief measure.

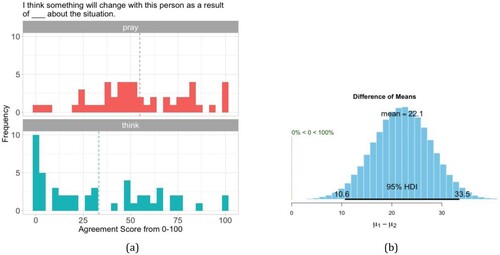

A similar pattern of results emerged from the measure “I think something will change with this person as a result of praying/thinking about the situation.” Participants in the prayer condition responded with a distribution of results that suggest they are unsure, but hopeful—i.e., spread out somewhat uniformly in the top half of the scale. Participants in the thinking condition are much more concentrated on the low end of the scale. ((a)) A Bayesian t-test posterior distribution shows a large effect, with a mean difference of 22.1 (95% HDI 10.6–33.5), an effect size of 0.79 ((b)).

Figure 6. (a) Distribution of participant responses to statement “I think something will change with this person as a result of praying/thinking about the situation.” Dashed lines show the median response for each condition. (b) Posterior distribution of differences of means between conditions from BEST on result measure.

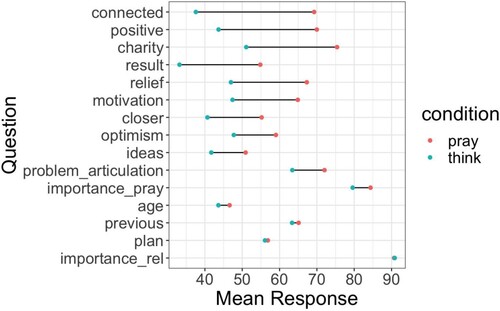

We found consistent results when analyzing collaborative problem-solving measures as a multi-item measure. When we analyze the difference of the mean of all collaborative problem-solving measures, BEST also shows a difference between the prayer and thinking aloud conditions, with a mean difference of means of 17.9 (95% HDI 7.36 28.4) and an effect size of 0.69.

We (authors ESH and TML) went through each of the 50 prayer transcripts in the prayer condition of the experiment and identified sections that showed collaborative problem solving. We looked for clear indications of an expectation that both the person praying and God had agency in solving some problem and that the person praying expected this was a joint project in which God would help but the person would play a part. Some explicitly said things like “I know I can’t do it alone,” or, “I know it’s because of you that I can do these things because you do them with me.” Others more specifically cited interdependent actions toward a shared goal, such as “Help me become more patient with [this difficult person] and I pray also that you help them in trying to understand me better,” or, “If you can’t tell me what to do or say, I would at least ask you to help me to guard the words that come out of my mouth.” God is helping the person to think differently, to remind the person of something, giving them wisdom or compassion. We found that 33 of the 50 each used phrases in which the person praying did one or more of: (1) Asked that God help the prayer to think differently in order to achieve a joint end (2) Asked God to remind them of something in order to achieve this shared goal (3) Asked that God make known his purpose in their thinking in order to achieve a joint end, or (4) Directly stated that they could not solve the problem without God’s help.

4.2.3. Other differences between prayer and thinking aloud

4.2.3.1. Values. Another large difference between conditions was on the measure “I feel more connected to the person after praying/thinking about the situation.” ((a)) A Bayesian t-test, produces a posterior distribution of differences of means ((b)) where the 95% HDI was [19.3–45.6] and the mean difference of means was 32.5—nearly a third of the scale—with an effect size of 1.01. Participants in the thinking-aloud condition are much more likely to strongly disagree that they feel more connected to the person they were thinking about and people in the prayer condition are much more likely to strongly agree that they feel more connected. There were similarly large effects in response to measures of motivation to solve the problem and feelings of positivity and charity toward the difficult person.

Figure 7. (a) Distribution of participant responses to statement “I feel more connected to the person after praying/thinking about the situation.” Dashed lines show the median response for each condition. (b) Posterior distribution of differences of means between conditions from BEST on connectedness measure.

We found consistent results when analyzing values measures as a multi-item measure. When we analyze the difference of the mean of all values measures, BEST also shows a difference between the prayer and thinking aloud conditions, with a mean difference of means of 25.2 (95% HDI 14.7–35.4) and an effect size of 0.98. These differences suggest that prayer reframes the problem at hand by surfacing relevant values for Christians, like “loving your neighbor as yourself,” in ways that thinking aloud does not. The mean responses by item and condition are shown in .

Figure 8. Mean responses for each question asked in the experiment in Study 3, by condition. This Cleveland plot shows the average difference between conditions, item by item, ordered by the magnitude of the difference. The measure of connection (“I feel more connected to the person after praying/thinking about the situation.”) had the largest difference between conditions, and the measure of the importance of religion to the participant had the least difference.

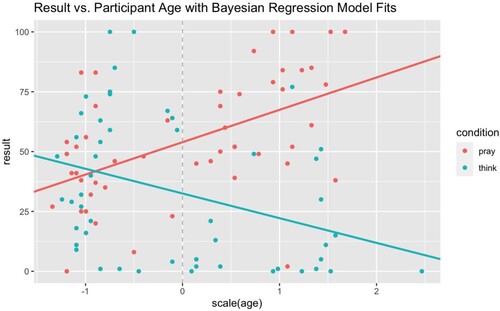

4.2.3.2. Age interaction effects. One concern going into the experiment was that, as practitioners grow more experienced in prayer, their thinking aloud might grow to be more like prayer. If you pray constantly, do all modes of thinking bend toward prayer? In fact, we found the opposite.

A Bayesian regression of connectedness predicted by age crossed with condition (connected scale(age)∗condition) showed not only a main effect of prayer (95% HDI 9.33–21.80) but also an interaction effect of prayer and age (95% HDI 4.95–16.73). This suggests that prayer in general carries a prosocial element than the problem solving in thinking aloud does not. Not only does prayer include this prosocial element, but it appears to strengthen over time with age and practice such that as people age they are more likely to feel connected post-prayer and less likely to feel connected post thinking aloud.

This was true also for the measure “I think something will change with this person as a result of praying about the situation.” A linear regression of participants’ responses to the statement predicted by age crossed with condition (result scale(age)∗condition) also showed a main effect of prayer (95% HDI 5.61–15.74) and an interaction effect of prayer and age (95% HDI 6.95–17.11). This means that, in general, people are more likely to think that something will change after praying versus thinking aloud about a problem. This effect gets magnified with age such that as people age, they are more likely to expect a result post-prayer and less likely to expect a result post-thinking aloud. Another set of possible explanations of this interaction effect is that efficacy in prayer and thinking aloud increases with age, but the slope is steeper for prayer or that efficacy holds constant in thinking aloud but increases in prayer. This latter explanation captures what seems to be happening in problem articulation, feeling motivated to solve the problem, and generating ideas. However, in the cases of feeling a connection, expecting a change as a result of praying/thinking aloud (shown in ), optimism about the outcome, feeling positive about the other person, and feeling charitable toward the other person, the slope on thinking aloud is negative (efficacy decreases with age).

Figure 9. Model fits by condition for the measure “I think something will change with this person as a result of praying about the situation.” The x-axis shows the age of participants, scaled for the purposes of modeling. The true age range of the x-axis is from 18-95. The y-axis shows participants’ responses to the measure “I think something will change with this person as a result of praying/thinking about the situation.” The lines show Bayesian regression model fits.

In fact, the same interaction of age and condition was present in almost all other measures, except for relief. Relief showed a main effect of prayer (95% HDI 3.40 16.48) but no interaction with age (95% HDI −5.72–7.09).

5. Discussion

5.1. Prayer as problem solving

The intention going into the first interviews was more generally to understand abstract reasoning and to identify the underlying cognitive mechanisms used in prayer. However, after interviewing prayer practitioners at length, problem solving emerged as a dominant framework and purpose of their prayers. These prayers often follow the structure of a four-step problem-solving process (Polya, Citation2004), as well as generating solutions through search and means-ends analysis (Simon & Newell, Citation1971). These ideas were quantified and confirmed in the findings of the prayer survey. Participants reported that prayer helps them better understand a problem they are facing, makes them more motivated to solve a problem they are facing, and helps them to feel more connected to a person they are experiencing a conflict with.

In the experiment, measures of problem-solving were found to be similar in both conditions. This suggests that prayer is similar to thinking aloud for understanding a problem, coming up with a plan for how to solve a conflict, and getting a clear sense of what actions to take going forward. However, there were large differences in certain measures, especially how connected the participant reported feeling to the person they were praying about, how much relief they felt as a result of prayer, and how much they felt that something would change as a result of their prayer.

We also found an interaction between condition and age for many measures. Participants in the prayer condition increased along several metrics, like how connected they felt to the person they prayed about, as they got older, while participants in the think-aloud condition decreased with age. The decrease in the think-aloud condition is a puzzle, but the increase in the prayer condition is consistent with a growing body of work that there are training effects of prayer (Luhrmann, Citation2012, Citation2020; Luhrmann et al., Citation2013).

5.2. Prayer as collaborative problem solving

When people engage in problem-solving in prayer, they treat God as a collaborator in that process. This process seems to involve a kind of task division and delegation—determining which parts of the conflict are within the practitioner’s control and which are not.

This theme of collaboration came up over and over in interviews with participants. In the interviews, only 3 out of the 16 showed no indication in their prayers of collaborative problem solving, that is according to Graesser et al., Citation2018: no differentiation of roles and no interdependency between group members. In the survey data, only 9 out of 151 participants reported “never” delegating any part of the problem they were praying about to God. Almost all participants reported that prayer feels like talking with someone else and does not feel like talking to themselves. In the prayer condition of the experiment, 33 out of 50 participants showed indications of collaboration, either by explicitly saying that they could not solve the problem alone, by articulating joint or interrelated actions toward their shared goal with God, or by asking for help (rather than making unilateral requests of God).

According to theories of collaborative problem solving (Graesser et al., Citation2018), if people are treating God as a problem-solving collaborator, we would expect to see the effects of delegating parts of the problem to God, namely taking parts of the problem off their own plate. We would predict that people feel more relieved after praying than just after thinking aloud about a problem because of this delegation. This is exactly what the results of the experiment showed: a main effect of the condition, where participants who prayed reported being more relieved than participants who thought aloud about their problem. Relief after prayer is not a unique effect of problem-solving. But given that these practitioners were praying about a problem and asking for help rather than forgiveness, and taken in conjunction with the qualitative evidence of their collaborative approach to solving the problem before them in their prayer transcripts, we see this result as consistent with a collaborative problem-solving account of prayer.

As one of the participants said after the experiment, “God is like a wild card. If it’s just me thinking, I don’t have much hope anything will change. But, when I hand it to God, anything could happen!”

5.3. Conclusion

We have found that prayer is a meaningful and effortful skill that practitioners train and develop over time and that Christians experience prayer as a site of collaborative problem-solving with God.

Through interviews and a protocol analysis, we found that prayers follow a classic problem-solving structure. A survey and experiment confirmed that prayer employs problem-solving tactics and found that the problem-solving really does help people solve practical problems in their lives. The experiment showed that a sample of Christian prayer practitioners had different problem-solving outcomes after praying about a problem than after thinking aloud about one. In particular, some of the outcomes point back to the collaborative nature of their problem-solving, such as feeling more relief and feeling more optimistic about a positive solution to the problem. We find this work to be primarily a compelling existence proof—that at least the people accounted for in these studies use prayer as problem solving and show signs of collaborating with God. We find it likely that this behavior is spread beyond this immediate sample. Given the many denominations represented and the lack of difference found between them, we speculate that problem solving is a widespread tool amongst American Christians who pray, and (especially) amongst those who pray about their problems. This sense of prayer as collaboration is likely possible for all humans who pray to a god they imagine to some extent as human-like—a god who thinks and responds. But that skill is also likely developed in some faiths more deeply than others.

Why do people pray? We provide an answer that is new—or at least, underdeveloped—in the social science literature: that prayer helps people to solve practical problems and gives them the sense that they do so in collaboration with their God. We hope also to demonstrate that prayer is an exciting site of research for cognitive scientists moving forward. Prayer is a place where people employ all kinds of behaviors that are of interest to cognitive scientists: attending to internal and external cues, working through problems, engaging in meta-cognitive behaviors, making important values salient, encountering dissonance, and managing emotions. In prayer, people are doing these things frequently, naturalistically, and with motivation, in a way that matters to them profoundly.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rob Goldstone, Peter Todd, Fritz Breithaupt, Rick Hullinger, and Tyler Marghetis for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this research and manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 All names have been changed to protect participant anonymity.

2 Using the r package ‘prcomp’ performed on scaled survey responses.

3 Using the r package ‘fa’ performed on scaled survey responses.

4 ACTS–adoration, confession, thanksgiving, and supplication, whether they use the ACTS model of prayer, and how often they attend church. The ACTS model of prayer is a very common model of prayer used to teach people how to pray, or at least to illustrate what important components of prayer are (Luhrmann, Citation2012).

5 Women do outnumber men along several religiosity scales, including how often they attend church and how frequently they pray, but not at a rate of 2:1 (“Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics”, Citation2022).

References

- Austin, J., & Delaney, P. F. (1998). Protocol analysis as a tool for behavior analysis. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392922

- Baquedano-Lopez, P. (1999). Prayer. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 9(1/2), 197–200. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.1999.9.1-2.197

- Capps, L., & Ochs, E. (2002). Cultivating prayer. The Language of Turn and Sequence, 39–55.

- Csordas, T. J. (1987). Genre, motive, and metaphor: Conditions for creativity in ritual language. Cultural Anthropology, 2(4), 445–469. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.1987.2.4.02a00020

- Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1984). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data. The MIT Press.

- Frazer, J. G., & Frazer, J. G. (1922). The golden bough. Springer.

- Graesser, A. C., Fiore, S. M., Greiff, S., Andrews-Todd, J., Foltz, P. W., & Hesse, F. W. (2018). Advancing the science of collaborative problem-solving. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(2), 59–92.

- Haeri, N. (2013). The private performance of salat prayers: Repetition, time, and meaning. Anthropological Quarterly, 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2013.0005

- Husserl, E. (2002). Pure phenomenology, its method, and its field of investigation. In D. Moran, & T. Mooney (Eds.), The phenomenology reader (pp. 124–133). Psychology Press.

- Keane, W. (1997). Religious language. Annual Review of Anthropology, 26(1), 47–71.

- Kruschke, J. K. (2013). Bayesian estimation supersedes the t test. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(2), 573. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029146

- Lienhardt, G. (1961). Divinity and experience: The religion of the dinka: The religion of the dinka. Oxford University Press.

- Lueke, N. A., Lueke, A. K., Aghababaei, N., Ferguson, M. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2021). Fundamentalism and intrinsic religiosity as factors in well-being and social connectedness: An Iranian study. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality.

- Luhrmann, T. M. (2012). When god talks back: Understanding the American evangelical relationship with god. Vintage.

- Luhrmann, T. M. (2020). How god becomes real: Kindling the presence of invisible others. Princeton University Press.

- Luhrmann, T. M., Nusbaum, H., & Thisted, R. (2013). “Lord, teach us to pray”: prayer practice affects cognitive processing. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 13(1-2), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685373-12342090

- Malinowski, B. (2014). Magic, science and religion and other essays. Read Books Ltd.

- Mayer, R. E., & Wittrock, M. C. (2006). Problem solving. In Handbook of Educational Psychology (pp. 287–303).

- Newell, A., Shaw, J. C., & Simon, H. A. (1959). Report on a general problem-solving program. IFIP Congress, 256(1), 64.

- Poloma, M. M., & Gallup, G. H. (1992). Varieties of prayer: A survey report. Trinity Press Internat.

- Polya, G. (2004). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method (vol. 85). University Press.

- Reis, L. A. D., & Menezes, T. M. D. O. (2017). Religiosity and spirituality as resilience strategies among long-living older adults in their daily lives. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 70(4), 761–766. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0630

- Religion in America: U.S. religious data, demographics and statistics. (2022). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscapestudy/gender-composition/.

- Ruffle, B. J., & Sosis, R. (2007). Does it pay to pray? Costly ritual and cooperation. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 7(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.1629

- Shoaps, R. A. (2002). Pray earnestly”: The textual construction of personal involvement in pentecostal prayer and song. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 12(1), 34–71.

- Simon, H. A., & Newell, A. (1971). Human problem solving: The state of the theory in 1970. American Psychologist, 26(2), 145.

- Smith, W. R. (1927). Lectures on the religion of the semites: The fundamental institutions (Vol. 1). A & C Black.

- Sosis, R., & Handwerker, W. P. (2011). Psalms and coping with uncertainty: Religious Israeli women’s responses to the 2006 Lebanon war. American Anthropologist, 113(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2010.01305.x

- Van Cappellen, P., & Edwards, M. (2021). Emotion expression in context: Full body postures of Christian prayer orientations compared to specific emotions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 45(4), 545–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-021-00370-6

- Watson-Jones, R. E., & Legare, C. H. (2016). The social functions of group rituals. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(1), 42–46.

- Xygalatas, D., Mitkidis, P., Fischer, R., Reddish, P., Skewes, J., Geertz, A. W., Roepstorff, A., & Bulbulia, J. (2013). Extreme rituals promote prosociality. Psychological Science, 24(8), 1602–1605. doi:10.1177/0956797612472910

Appendix

Appendix A. Interview questions

A.1. Demographics

Age

Gender (pronouns)

How would you describe your faith life?

How would you describe your church/faith community?

How often do you pray?

Why do you pray?

What do you get out of prayer?

How does prayer relate to your overall faith?

° More important, less important?

° Present at most events?

A.2. Warm up prayer exercise

I would like to get to know your prayer style as an individual. Think about your day or week, or even just what has been on your mind or heart lately. Can you pray aloud for a bit?

A.3. Prayer scenarios to pray through

After each prayer exercise, I will ask them to go through the same prayer topic again, but talk aloud about their process. How did they decide what to say? Why in that order? The goal of this is to richly and naturalistically get at people’s prayer processes. After prayer, ask people to reflect (and talk out loud as they reflect).

Can you think of an issue or situation that you’ve been going through lately? Can you please pray aloud as you normally would about it?

Can you think about a situation facing your community right now, maybe how your church is facing the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. How would you pray about this? Can you please pray aloud as you normally would about it?

A.4. Post-Protocol questions

Questions to help contextualize responses

How do you think prayer affects the external world?

How do you think prayer affects what’s going on in your heart and mind?

What instruction have you received about prayer? Are you using any specific strategies that you could articulate?

What do you think the differences are for you when you pray out loud vs silently? In a group vs alone?

Questions about social aspect

Does it feel like a social experience when you pray? And what about during reflection?

Do you feel is God there like a person?

Like a person on the phone?

Like a person in the room?

Like a person when you write a letter?

Do you ever feel more connected to people because of prayer? (like the person/people you’re praying for or your Christian community)

Questions about conceptual connections

Do you feel that prayer changes what you pay attention to in your life outside of prayer?

Does prayer make your Christian values feel more present or relevant in your life outside of prayer?

Does prayer ever highlight new connections in your life outside of prayer?

Questions about other cognitive strategies

Sometimes people use certain strategies when they make hard decisions (people will make a list of pros & cons, or talk it over with a friend), does prayer feel like one of those strategies to you? (compare/contrast)

What is your visual or other sensory imagery like when you pray? Do you focus on your visualization? Does this feel helpful to you?

What about when you are reflecting? Is your experience of imagery similar? Different?

Appendix B. Survey

B.1. Survey questions

What is your age?

What is your gender identity?

How often do you go to church?

What kind of church do you go to?

My faith/religion/spirituality is important to me.

How often do you spontaneously pray by yourself?

Prayer is an important part of my faith life.

How often do you pray aloud (as opposed to silently)?

How often are your prayers read or recited from memory?

What does it look like for you when you pray? Do you have a specific routine? Specific times of day when you pray? Please briefly describe below:

Have you received instruction about how to pray?

Have you heard of the A.C.T.S. model of prayer? (Adoration, Confession, Thanksgiving, Supplication)

Do you use the A.C.T.S. model when you pray?

How often do you pray alone vs. in a group?

Does prayer help you understand a problem you are facing?

Does prayer feel like journaling or writing something in your diary?

Does prayer feel like talking to yourself?

Does prayer feel like talking something over with someone else?

How often does praying about a problem change the way you see it?

How often have you started to pray about one thing, but find yourself praying about something else?

How often do you feel like praying gives you a clear sense of what action you should take after you pray?

How often does prayer make you feel optimistic that there is a constructive solution to the problem you are praying about?

When you are praying, how often do you “give it to God”—i.e., relinquish responsibility over the problem (or parts of the problem) you are praying about?

How often does prayer help you resolve conflict with someone else?

How often does prayer make you feel more connected to the people you are praying about?

When you pray about someone, does it make you feel more positively towards them?

Do you feel more charitable towards a person who is difficult for you because of praying for them?

How often does prayer remind you of important values?

How often do you feel a sense of relief after you pray?

How often does prayer make you feel more motivated to tackle a problem in your life?

How often do you finish a prayer wishing you had prayed something different?

How often do you think God makes internal changes within you as a result of your prayer?

How often do you think God makes internal changes within someone else as a result of your prayer?

How often do you think God physically intervenes in a situation as a result of your prayer?

B.2. Aggregated survey responses

B.4. Survey factor analysis

Table B2. This table shows the loadings on the first and second components of a principal component analysis, ordered from largest to smallest on the first loading. The three largest positive loadings are highlighted in each component.

Appendix C. Experiment

C.1. Experiment questions

What is your age?

What is your gender identity?

How often do you go to church?

What kind of church do you go to?

My faith/religion/spirituality is important to me.

How often do you spontaneously pray by yourself?

Prayer is an important part of my faith life.

I have prayed about this particular situation before.

Questions from here down differed depending on condition, represented by praying/thinking. People in the prayer condition saw “praying” words, people in the thinking aloud condition saw “thinking” words.

I understand the situation I am facing better as a result of praying/thinking about it.

I am closer to solving the conflict with this person.

I have new ideas or a new plan for how to solve this conflict with this person going forward.

I have a clear sense of what action I should take in this conflict with this person going forward.

I am motivated to resolve conflict with this person after praying/thinking about the situation.

I am optimistic that there is a resolution to this conflict after praying/thinking about the situation.

I feel more connected to the person after praying/thinking about the situation.

I feel more positively towards the person after praying/thinking about the situation.

I feel more charitable towards the person after praying/thinking about the situation.

I feel a sense of relief after praying/thinking about the situation.

I think something will change with this person as a result of praying/thinking about the situation.