Abstract

Medication Reconciliation (MedRec) is the comprehensive process of medication verification, clarification and documentation in an effort to avoid medication errors. There are many reasons that contribute to the inadequacies of current day inpatient MedRec. Among these include the limited medical literacy of patients, communication between providers and teams of providers, and the intrinsic difficulties of medical charting. Although the best approach to inpatient MedRec is not known, the following outlines the 10 most important aspects, or “Commandments”, for effective inpatient MedRec. The tenets are not listed in any particular order of importance.

Introduction

Medication Reconciliation (MedRec) is the comprehensive process of medication verification, clarification and documentation in an effort to avoid medication errors. In 2005, the Joint Commission, the organization that accredits more than 20,000 healthcare programs in the United States, formally recognized MedRec as an important healthcare process. More than 8 years after the recognition, inpatient MedRec remains inadequate. Sub-standard MedRec may lead to significant iatrogenic adverse outcomes [Citation1].

There are multiple reasons for the inadequacies of current day inpatient MedRec. These include relying on patients with limited medical literacy for detailed knowledge of their medications, multiple layers of healthcare personnel responsible for MedRec resulting in potential miscommunication between healthcare providers, and the intrinsic difficulties of medical charting [Citation2-8]. The best approach to inpatient MedRec is not known and remains to be investigated. However, the 10 most important aspects or “commandments” essential to effective inpatient MedRec are outlined below.

Commandment one: make MedRec a unique component of the problem oriented medical record

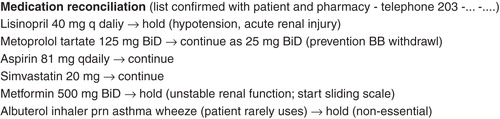

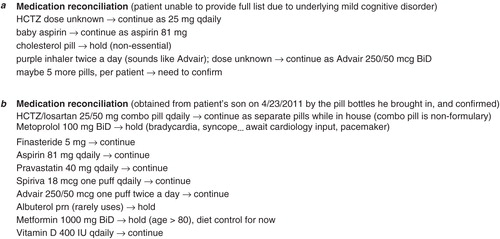

In typical inpatient charting, it is customary to identify the patient’s medical issue(s) in a Problem Oriented Medical Record format. This entails listing the issue(s), then commenting on the status and the plan of action [Citation9]. illustrates the assessment documentation using the Problem Oriented Medical Record, of a sample patient, who was admitted to the hospital with chest pain.

Figure 1. A sample problem oriented medical record illustrating an inpatient progress note of a patient with chest pain. Medication reconciliation of outpatient medications should be a recognized in a similar manner.

Similarly, in documenting inpatient MedRec, the patient’s outpatient medications should be listed, and recognized, as a separate medical “problem” or “issue”. The outpatient medication(s) should be listed after all other acute or chronic inpatient medical issues are analyzed (i.e. towards the end of document) and with the plan for each medication’s continuation (or discontinuation) plan. Electronic medical records can facilitate this process.

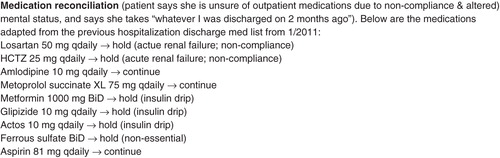

To illustrate, is an excerpt from a patient’s hospital admission note. The patient is a 68-year-old female with hypertension, type II diabetes, dyslipidemia and asthma, who was admitted for vomiting, diarrhea, borderline low blood pressures, hypovolemia resulting in acute renal insufficiency. The admission note identified each of her inpatient “problems”, and provided the status and plan (not shown). The last “problem” listed on the admission note document is the MedRec. Recognizing MedRec as its own separate “problem” engages the provider to note the patient’s medication baseline and to transition the patient’s outpatient medication with clarity.

Commandment two: indicate how the outpatient medication list was derived

Note that the medication list in was derived from the patient interview and confirmed with the patient’s pharmacy. Denoting this enables all those involved in the patient’s care, a degree of confidence in the medication documentation at the time of hospitalization. In turn, this can decrease confusion among all involved as part of the healthcare team, improve patient care hand-offs between provider to provider, and enhance the validity of the medication documentation.

Commandment three: detail the rationale behind outpatient medication changes

Record in the MedRec changes to the outpatient medication regimen and, when appropriate, the clinical implications of these changes. This would include dose alterations, medication discontinuation, etc. Note in that the patient’s metoprolol tartate was given at a reduced dose and the lisinopril was held for specific medical concerns. If stated clearly, the MedRec can provide insight into the provider’s thought process and management strategy. Utilizing this practice is paramount in an era where there is a high frequency of physician to physician handoffs in inpatient care.

Commandment four: utilize MedRec in the assessment of a patient’s hospital discharge

The patient in Example 2 suffered a sustained decline in her baseline renal function and in the hospitalization, noted poorly controlled diabetes, and was discharged home with several medication changes. These changes could pose serious concern regarding an “unsafe hospital discharge”, should the patient demonstrate difficulty in following the new medication plan upon hospital discharge [Citation3,10]. Using MedRec to realize the magnitude of changes to the original outpatient medication list, can be a trigger to investigate the patient’s capabilities and medication understanding. Post-hospitalization assistance, either through home visiting nurses or follow-up telephone calls may then be offered. In essence, MedRec can be integrated as a “safety net” for optimal post-discharge patient care [Citation11,12].

Commandment five: perform MedRec every day (at a minimum)

The initial admission medication list is may be incomplete and/or inaccurate. Often, as the patient’s medical condition stabilizes or after some investigation, does a patient’s true outpatient medication list becomes apparent; this may be on an order of hours to days. Revisiting and updating the outpatient medication list obtained at the time of admission may be necessary despite the best provider effort who made the initial patient contact.

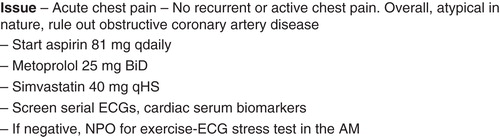

The following is an example from the Admission Note for a cognitively impaired patient who was admitted for the management of syncope (see ). In , the outpatient medication list was incompletely obtained, but and was appropriately documented (i.e. “patient unable to provide full list due to underlying cognitive disorder”). Only by hospital day 4 did the patient’s true outpatient medication list surfaced, see .

Figure 3. (a) Initial inpatient medication reconciliation documentation of outpatient medications in a patient who is unable to provide an accurate outpatient medication list. (b) Updated inpatient medication reconciliation documentation of outpatient medication list after confirmation with the patient’s family.

Electronic medical records may facilitate the ability to track medication changes. Furthermore, it is important to avoid “hard-wiring” or irrevocably marking the initial outpatient medication list as permanent. As noted in this sample case, obtaining the true outpatient medication list during a patient’s hospitalization can be a work-in-progress and be subjected to change as collateral information is being collected.

Remembering to review the outpatient medication list at least once per day is important. For this patient, the provider was able to realize that a different anti-hypertensive agent drug (lisinopril) had been chose for inpatient anti-hypertensive control, and resumed losartan. Furthermore, detail was also noted for the combination pill that was not available in the hospital formulary and that two separate pills would be needed to take the place of the combination pill. Also, note that MedRec is important in the day-to-day care of patients - not only during hospital transition points, such as patient transfer from the emergency room to the medical floors, in/out of the Intensive Care Unit, or from hospital to home [Citation13,14].

Commandment six: assess the patient’s likelihood of medication compliance

Patients with medication non-compliance or a difficult to follow medication scheme are difficult to manage in an inpatient setting. The practice of MedRec should acknowledge and address this important aspect of patient’s medical behavior. The following is an example of a patient with poorly controlled hypertension, brittle diabetes, and major depression who was admitted to the Intensive Care United for altered mental status, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic nonketotic ketoacidosis, urinary tract infection, systolic blood pressures in the 180–190 mmHg range, and poor recollection of her medications (see ).

Figure 4. Inpatient medication reconciliation documentation of a patient with medication non-compliance.

Noting the patient’s medication non-adherence, and as a consequence, chronically elevated blood pressures, makes it compelling to gradually re-institute anti-hypertensive agents to prevent rapid blood pressure correction. Additionally, reporting medication non-adherence on the daily MedRec may facilitate early investigation into the patient’s psycho-social confounders, as well as, offer appropriate post-hospital discharge assistance and follow-up counseling. In the evolving inpatient medicine workplace with multiple layers of providers and shift work, relaying specific details of medication adherence amongst the healthcare team is crucial.

Commandment seven: engage medical consultants to contribute to MedRec

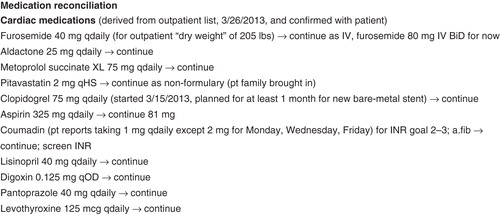

Patients with complex medical issues are a commonplace in hospital settings, and often require for consultant input. Consultants can play an important role towards contributing to an accurate inpatient MedRec, whether by accessing key outpatient records or by detailing insight into medication regimens most familiar to the respective specialty. Next is an example from the initial cardiology consultation note’s MedRec of a patient who was admitted for pneumonia and congestive heart failure (see ).

From the case illustration in , the Cardiology consultant provided patient’s outpatient diuretic regimen, and detailed the patient’s “dry weight”; this may clinical relevant during the patient’s hospital stay. Also, the MedRec hinted to consensus-based recommendations regarding triple anti-thrombotic therapy of aspirin, clopidogrel and coumadin in the management of the patient’s concomitant paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease. Aspirin was reconciled to a lower dose. The duration and indication of clopidogrel was clarified. Coumadin indication and dose were provided - important in light of the antibiotic prescription to treat the patient’s active pneumonia. A proton pump inhibitor is recommended for patients on triple anti-thrombotic therapy, a subject area a Cardiologist might be most familiar with [Citation15]. Lastly, levothyroxine was added to the MedRec in the Cardiology Consultation MedRec, because abnormal thyroid function affects cardiovascular function. Other medications deemed not immediately relevant to the consultant’s specialty can be omitted; in this example, the patient’s medication for his prostate, osteoporosis and depression (unless the list of these medications were not available as well) were not included in the consultant’s MedRec.

Commandment eight: when appropriate and/or necessary, provide specific time-sensitive detail to outpatient medications

Certain medication regimens are duration-specific and time-relevant. For example, dual antiplatelet therapy, has the greatest benefit during the first year post coronary artery stent placement (particularly in settings of an acute coronary syndrome), afterwards which the relative risk to benefit ratio may begin to decrease. Other commonly encountered medications that are time-sensitive include active antimicrobial course for infections that pre-dated the hospitalization or an anti-coagulation course for veno-thrombotic event that occurred prior to the patient’s current hospitalization - both should have the start and planned discontinue date noted as part of the MedRec. At times, the discontinuation date can occur during the hospitalization and this plan should be carried out accordingly.

Commandment nine: for the patients transferred from another hospital, MedRec must include the original outpatient medication as well as the medication regimen administered at the other hospital

Patients transferred from a hospital to another hospital system are often complex and are subjected to the flaws of medical information transfer. In an attempt to address these errors, a comprehensive method for MedRec is necessary. MedRec for patients transferred from another hospital is to first identify both the original outpatient medications and the medications from the other hospital. Then, a thorough review and documentation of each medication for reconciliation can ensue.

Commandment ten: identify the physician who is responsible for MedRec

Most hospital systems employ multi-disciplinary collaboration, involving physicians, consulting physicians, mid-levels and pharmacists. The roles can be well-defined or flexible according to resources available and institution structure. Complicating this model is the element of hospital shift-work and the range of medical knowledge of each member of the medical team. All in all, this makes it imperative for the lead physician of the primary team to assume responsibility in the organization of the all medication data gathered for the formulation the MedRec.

Pursuing an accurate outpatient medication list may require the work of more than one individual, but the responsibility of the lead physician on consolidating the data into one concise “live document” of the daily progress note, with the appropriate subsequent therapeutic action, is essential. Often times, the barriers to optimal inpatient MedRec is blamed as a “system’s issue” such as the disjointed nature of the American health care system, but not one that cannot be overcome with the persistent and committed effort from the individual lead provider [Citation3].

Conclusion

Inpatient MedRec must be meticulously implemented and with a degree of uniformity in inpatient practice. Every patient’s clinical scenario is unique and every provider will adopt his/her own medical record keeping style, but the tenets listed will help in formulate precise communication of MedRec within a familiar Problem Oriented format.

It should be emphasized that the Ten Commandments were not listed in any particular order - they all are equally important. Embracing the importance and instituting a framework for quality inpatient MedRec should start as early as medical school and training. Although the above principles are derived from common sense medical practice and anecdotal experience, this article provides a method to achieving the goal of improved MedRec and not merely not re-iteration of a known problem in current day inpatient medicine [Citation1].

Integrating other members of an inpatient medical team can facilitate inpatient MedRec, but The Commandments returns the responsibility of MedRec onto the most responsible physician on the inpatient service. This requires leadership and tenacity to medication detail. Effective MedRec is a reasonable expectation for every physician practicing in today’s in-hospital environment.

Acknowledgement

I want to thank Dr. Howard H. Weitz, MD, Chairman of the Jefferson Heart Institute, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, for his assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- The Joint Commission. 2011 national patient safety goals. 2011. Available from http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Policy/PatientSafety/Optimizing-Med-Reconciliation.aspx. Accessed on June 7, 2014

- Barnsteiner JH. Medication reconciliation. In Hughes RG, ed. Patient safety and quality. An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. p 2–459. 2-472. Print

- Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Greene J, LaCivita C, Stucky E, Benjamin B, Reid W, et al. Making inpatient medication reconciliation patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med 2010;5:477–85

- Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, Baker DW, Lindquist L, Liss D. Results of the medications at transitions and clinical handoffs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:441–7

- Durán-García E, Fernandez-Llamazares CM, Calleja-Hernández MA. Medication reconciliation: passing phase or real need? Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34:797–802

- Kramer JS, Hopkins PJ, Rosendale JC, Garrelts JC, Hale LS, Nester TM, Cochran P, et al. Implementation of an electronic system for medication reconciliation. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007;64:404–22

- Peterson JF, Shi Y, Denny JC, Matheny ME, Schildcrout JS, Waitman LR, Miller RA. Prevalence and clinical significance of discrepancies within three computerized pre-admission medication lists. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2010;2010:642–6

- Moore P, Armitage G, Wright J, Dobrzanski S, Ansari N, Hammond I, Scally A. Medicines reconciliation using a shared electronic health care record. J Patient Saf 2011;7:148–54

- Weed LL. Medical records, patient care, and medical education. Ir J Med Sci 1964;462:271–82

- Ziaeian B, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH, Horwitz LI. Medication reconciliation accuracy and patient understanding of intended medication changes on hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1513–20

- Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, Forsythe SR, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87

- Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L, Cohen BA, Prengler ID, Cheng D, Masica AL. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med 2009;4:211–18

- Kwan JL, Lo L, Sampson M, Shojania KG. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:397–403

- Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD008986

- Faxon DP, Eikelboom JW, Berger PB, Holmes DR, Bhatt DL, Moliterno DJ, Becker RC, et al. Consensus document: antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary stenting. A North-American perspective. Thromb Haemost 2011;106:572–84