ABSTRACT

Objectives

Relatively little is known about the hospital experience among patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI). The objectives of this study were to examine hospital encounter characteristics, including the associated economic burden and risk of subsequent hospital encounters of patients with MDSI in the US.

Methods

In this retrospective analysis, patients ≥18 years of age with a hospital encounter (emergency department [ED] visit or inpatient admission) were selected from the de-identified Premier Hospital database between 1 January 2017 and 30 September 2018. Patients were required to have MDD as the primary and acute suicidal ideation or behavior as a secondary discharge diagnosis or vice versa. Patient demographics and characteristics of hospital encounters were examined. Rates and costs of subsequent all-cause and MDD-related hospital encounters 6 months following initial discharge were also evaluated.

Results

The study population consisted of 123,179 patients with a hospital encounter for MDSI (mean age: 38 years, 50.9% female, 74.6% White); 50.2% were treated in the ED only (mean ± standard deviation cost: $693±$630), while 49.8% were admitted as inpatients ($6,478±$7,001). Among those with ED visits, very few (7.0%) received an antidepressant (AD). Among those with an inpatient admission, 87.2% received ≥1 AD and 39.0% received AD augmentation. Overall rates and costs of subsequent all-cause and MDD-related hospital encounters were 22.3% ($5,136±$11,791) and 12.0% ($3,722±$9,621), respectively; nearly half of subsequent encounters (41.3% and 44.3%, respectively) occurred in the first month following initial discharge.

Conclusions

This analysis of patients with MDSI presenting to US hospitals shows heterogeneity in treatment and a concentration of costly subsequent hospital encounters within 1-month post discharge, suggesting that healthcare systems may benefit from examination of current care pathways for this vulnerable patient population.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a heterogenous, chronic mental health condition in which patients may experience symptoms including depressed mood, loss of pleasure, impaired daily functioning, insomnia or excessive sleeping, fatigue, weight loss or gain, indecisiveness, worthlessness, and recurring serious thoughts of suicide [Citation1,Citation2]. The number, frequency, and intensity of symptoms can vary between individuals with MDD, but also vary over time in the same individual [Citation1,Citation2]. Based on the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, it is estimated that over 17 million adults, or 7.2% of the adult population in the United States, experienced a major depressive episode within the prior year, 65% of whom experienced severe impairment of major life activities [Citation3]. Severe MDD symptoms are a common reason for hospitalization; a study of adult hospital stays in the US reported that 1.3% had a primary discharge diagnosis code of MDD, of which 54% also had a diagnosis code of suicidal ideation and 6% a suicide attempt code [Citation4]. Moreover, an analysis of Nationwide Emergency Department Sample data found that the number of Emergency Department (ED) visits for depression increased by 26% between years 2006 and 2014 and greater than one-half of the ED visits in 2014 resulted in an inpatient admission [Citation5].

The high demand on hospitals to deliver care to patients with behavioral health conditions has been recognized by the American Hospital Association (AHA) [Citation6,Citation7]. A stated priority of the AHA is to change the current model of providing short-term behavioral healthcare in the ED and inpatient settings and improve access to behavioral healthcare in the community and in primary care; under the new model, a key role for EDs is to connect patients to timely outpatient behavioral healthcare upon discharge from the ED [Citation6,Citation7]. A more in depth understanding of existing hospital encounters may provide healthcare systems with valuable information to better design and construct evidence-based protocols to optimize treatment and improve health outcomes for patients with behavioral health conditions. In this study we describe the hospital encounters of a particularly vulnerable patient population, those with MDD and acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI). Research to further describe the treatment pathways of this population is critical to explore since MDD is one of the most prevalent diagnoses among people who die by suicide [Citation8,Citation9], rates of which have been increasing over the last 20 years [Citation10]. Specifically, we examined the hospital encounter characteristics, including the psychopharmacological treatment received, the rates of subsequent hospital encounters, and the associated hospital economic burden among a large patient sample with a hospital encounter (ED visit or inpatient admission) indicative of MDSI recorded on discharge records selected from a nationally representative US hospital database. Factors predictive of the risk of a subsequent MDD-related hospital encounter were also explored.

Methods

Study design and patient population

This was a retrospective analysis of patients ≥18 years of age with a hospital encounter (ED visit or inpatient admission) for MDSI selected from the de-identified Premier Hospital database between 1 January 2017 and 30 September 2018. Patients were required to have MDD as the primary and acute suicidal ideation or behavior (case identification was based on Hedegaard et al, defined by suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or intentional self-harm likely due to suicide attempt) [Citation11] as a secondary discharge diagnosis or vice versa; the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnoses codes and code descriptions are provided in Appendix ables 1 and 2. The Premier Hospital database is a nationally representative database capturing >45 million hospital discharges and >300 million hospital outpatient visits from >700 acute care hospitals, representing approximately 20% of all US hospital admissions. Data elements are collected for administrative purposes and include patient demographics, hospital characteristics, and visit/admission-level information on diagnoses, procedures, and medications. In compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, the Premier Hospital database is fully de-identified.

The earliest hospital encounter for MDSI was labeled as the index encounter and the discharge date of this event was defined as the index date. Patients were excluded if they had ≥1 diagnosis of bipolar disorder, dementia, intellectual disability, schizophrenia or other non-mood psychotic disorders, cluster b personality disorders, or substance induced mood disorders at any time during the study period. A hospital encounter in which the patient was seen in the ED only and not admitted to the inpatient setting was classified as an ED visit and one which resulted in an inpatient stay was classified as an inpatient admission. Also, to ensure the availability of the acute care information after hospital encounters, patients were excluded if they were discharged from their index hospital encounter to other acute care facilities. Patients who met the study criteria were grouped into a final overall study population and additionally stratified by the index encounter setting type (ie, ED visit or inpatient admission) for study measurements.

Demographics and index hospital encounter characteristics

Demographics and index hospital encounter characteristics, including admission source, hospital characteristics, MDD diagnosis (primary or secondary), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score [Citation12], mental health-related conditions, and Diagnosis Related Group (DRG; inpatient admissions only), were evaluated. The total inpatient length of stay (LOS) and hospital charges and costs were determined for index hospital encounters. In the Premier database, hospital charges reflect the amounts charged to the payer for the encounter, while hospital costs reflect the costs to the hospital for the encounter. All charge and cost data reported are from the hospital perspective and were inflation adjusted to 2019 USD.

Treatments received during index hospital encounters

Psychopharmacological treatments received were evaluated, including any antidepressant (AD); AD augmentation therapy (select second-generation antipsychotics, select anticonvulsants, or lithium); thyroid hormone; any psychostimulant; any sleep aid or benzodiazepine; and multiple types of the aforementioned psychopharmacological medications [Citation13].

Subsequent all-cause and MDD-related hospital encounters

During the 6 months following initial discharge, subsequent hospital encounters were evaluated and classified as all-cause or MDD-related if the encounter had a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis code indicating MDD. LOS, hospital charges, and costs for the subsequent hospital encounters were also determined. The Premier Hospital database attaches a unique ID to each patient at one specific hospital system. This enabled us to link initial hospital encounters and subsequent hospital encounters in the follow-up by the same patient, but only if the subsequent encounter occurred at the same hospital.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to examine patient demographics, index hospital encounter characteristics, treatments received during index hospital encounters, as well as rates of subsequent hospital encounters, associated LOS, charges, and costs. Differences between patient cohorts with an ED visit only and those with inpatient admissions were evaluated for statistical significance with chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Multivariable Cox regression analysis was conducted to identify potential factors predictive of the risk and time of a subsequent MDD-related hospital encounter with p-values determined by Maximum Likelihood Estimates. The following factors were included in the regression analysis: index encounter setting (inpatient admission vs. ED visit), primary vs. secondary MDD diagnosis, age, sex, race, marital status, health plan payer type, index year, hospital characteristics (urban/rural location, teaching status, size, and US geographic region), and individual CCI conditions. A critical value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4.

Results

Demographics and index hospital encounter characteristics

The overall study population consisted of 123,179 adult patients with a hospital encounter for MDSI (mean age: 37.9 years, 50.9% female, 74.6% White); 50.2% (n = 61,814) were treated in the ED only, while 49.8% (n = 61,365) were admitted to the inpatient setting. Demographics and index hospital encounter characteristics are shown in . The mean age was lower among patients with ED visits, compared to those with inpatient admissions (36.2 vs. 39.5 years, p < 0.001). Correspondingly, among those with ED visits, a younger age distribution was observed, with 53.7% being 18–34 years of age compared to 44.6% of those with inpatient admissions (p < 0.001). Although statistically significant differences were observed for sex and race distributions across patients with the different index encounter settings, they were relatively small. However, the distribution of health plan payer types differed more noticeably, with a significantly higher proportion of patients with ED visits being uninsured compared to those with inpatient admissions (self-pay: 19.9% vs. 9.9%, p < 0.001). Among patients with ED visits, 88.3% were admitted from nonhealthcare settings. Among those with inpatient admissions, over one-third (35.1%) were transferred from healthcare facilities (different hospital, clinic, detox unit in same hospital, other health facility), while 61.8% were admitted from nonhealthcare settings.

Table 1. Demographics and index hospital encounter characteristics

Nearly all patients (95.0%) with an inpatient admission had a primary diagnosis of MDD, whereas approximately two-thirds (64.6%) of those with ED visits had a primary diagnosis of MDD. Mean CCI score was higher among those with inpatient admissions compared to among those with ED visits (0.47 vs. 0.20, p < 0.001). Significantly greater proportions of patients with inpatient admissions compared to those with ED visits had other mental health-related conditions recorded during their index hospital encounters; the most prevalent were anxiety disorders (49.2% vs 21.9%, respectively) and trauma/stressor-related disorders (16.3% vs. 5.3%, respectively). Among those with inpatient admissions, 73.1% were categorized as DRG 885: Psychoses and 21.7% as DRG 881: Depressive neuroses. The mean ± standard deviation LOS for the cohort with an inpatient admission was 5.1 ± 4.5 days; the distribution of LOS by 1–3 days, 4–5 days, and ≥6 day was 40.2%, 28.7%, and 31.0%, respectively. For index hospital encounters, mean hospital costs for inpatient services ($6,478 ± 7,001 USD per patient stay) were nearly 10 times higher than ED costs ($693 ± 630 USD per patient stay).

Treatments received during index hospital encounters

Among patients with an ED visit, very few (7.0%) received an AD; the most common treatment received was a sleep aid or benzodiazepine (21.3%; ). For those with an inpatient admission, 89.0% received care in psychiatric units and the vast majority (87.2%) received an AD; 39.0% received AD augmentation therapy (mostly with an antipsychotic), 48.4% received a sleep aid or benzodiazepine, and 11.0% received psychostimulants; 64.7% received multiple types of psychopharmacological medications ().

Table 2. Treatments received during index hospital encounters

Subsequent all-cause and MDD-related hospital encounters

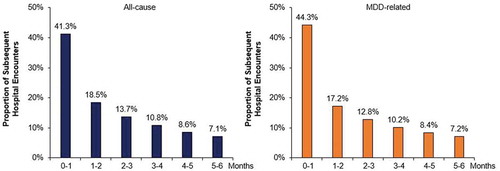

During the 6-months following initial discharge, 22.3% of the overall MDSI population had a subsequent all-cause hospital encounter, 41.3% of which occurred in the first month (). The rate of a subsequent all-cause encounter was higher among those with an initial ED visit, compared to those with inpatient admissions (25.0% vs. 19.6%, p < 0.001). Similarly, 12.0% had a subsequent MDD-related hospital encounter, 44.3% of which occurred in the first month (). There was a small difference in the rates of subsequent MDD-related hospital encounters between those with initial ED visits and those with inpatient admissions (11.6% vs. 12.4%, p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Time to subsequent hospital encountersa during the 6 months following initial discharge

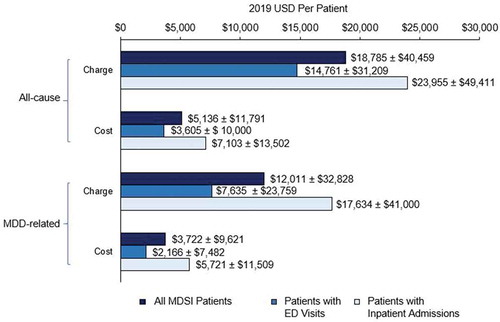

Among the overall patient population, the mean hospital charges for all-cause and MDD-related subsequent hospital encounters were $18,785 USD and $12,011, USD respectively (). Hospital costs had similar trends as observed for the hospital charge data, but the charge amounts were substantially greater.

Figure 2. Hospital charges and costs of subsequent hospital encountersa during the 6 months following initial discharge

Potential factors predictive of the risk of a subsequent MDD-related hospital encounter

Cox regression results examining potential predictors of risk and time to a subsequent MDD-related hospital encounter are reported in the Appendix (Table 3). After adjusting for potential confounders, index encounter care setting (inpatient admission vs. ED visit) was not significantly associated with subsequent MDD-related hospital encounters. However, many other variables included in the regression analysis were significant; for example, patients with Medicare, Medicaid, self-pay, and other payer types vs. those who were privately insured and those who were single vs. married were estimated to have an increased risk, and those patients who were Black and other races vs. White and female were estimated to have a decreased risk.

Discussion

In this real-world analysis of over 120,000 patients presenting with MDSI to hospitals in the US, approximately one-half were seen in the ED and discharged from that hospital, while the other half received inpatient services at the hospital where they presented. Characteristics of patients with inpatient admissions differed from those with ED visits, including that they were older and had more diagnosed physical and mental health-related comorbidities. The higher prevalence of comorbidities among patients with inpatient admissions could partially be attributed to comorbidity diagnoses being more comprehensive than for patients with ED visits. Of those admitted to the inpatient setting, most received an oral AD, which is a recommended standard of care for the treatment of MDD either alone or in combination with cognitive-behavioral therapy or interpersonal psychotherapy [Citation13]. However, there exists an opportunity to further optimize care for this population, especially in light of studies estimating that only between 11% and 30% of patients with MDD who receive AD pharmacologic treatment achieve clinical remission [Citation14–17], underscoring the need for continuity of care and follow-up after hospitalization. Among the patients included in this study, irrespective of initial care site, the concentration of subsequent hospital encounters that occurred in the first 30 days of initial discharge was particularly striking. We also observed that many non-clinical factors were associated with an increased risk of an MDD-related hospital encounter within 6 months of initial discharge.

Our study findings highlight an opportunity to improve screening for mental health conditions and access to mental health services in the community and primary care settings. We observed that nearly 50% of the MDSI patient population was between the ages of 18 and 34, representing a demographic group who often do not routinely receive care from primary care providers, and may present to EDs during periods of psychiatric crisis [Citation18,Citation19]. This problem is further underscored by national studies, which have found that the prevalence of depression and suicide-related outcomes has increased among younger aged adults over the last 20 years [Citation20,Citation21]. Note that less than 10% of patients in the ED visit cohort received an AD during their visit. This was not surprising since the ED is typically a site of triage and not a place where initiation of a chronic medication would commonly occur. It should also be noted that the medications prescribed following discharge are not captured in the Premier Hospital database. This topic warrants future research when evaluating transitions of care from the ED to the community, as timely follow-up to receive appropriate treatment and mental healthcare is a priority of the AHA [Citation6,Citation7]. Such actionable steps may have significant clinical utility for improving outcomes of patients with MDSI, including the risk of a subsequent hospital encounter.

Among patients with an initial inpatient admission for MDSI in this study, the average cost to hospitals was $6,478 USD per patient, which was nearly 10-fold higher than observed for those with initial ED visits (average cost: $693 USD per patient). Another study that used the Premier Hospital database (2014–2015) found that among all patients with MDD, average hospital costs were $6,713 USD per stay, which is similar in magnitude to the estimates presented herein for the MDSI population [Citation4]. We also found in our study that the costs to hospitals for subsequent hospital encounters were substantial, on average $5,136 USD per patient for an all-cause encounter and $3,722 USD per patient for an MDD-related encounter.

Our findings of the possible influence of race, health insurance coverage type, and hospital characteristics on the risk of a subsequent MDD-related hospital encounter may be suggestive of non-clinical barriers to adequate and effective mental healthcare. A study of 636 patients admitted to EDs in the US in 2015, reported that among those with mild or greater severity depression (42%), top barriers to care included work responsibilities, concerns over doctor responsiveness, and transportation difficulties; other barriers included lack of insurance, healthcare bills, and feelings of embarrassment related to their potential illness [Citation22]. Further studies of patients with MDSI are warranted to provide a greater understanding of their specific barriers to receiving timely mental healthcare.

The findings of this study require consideration of certain limitations. First, the rates of subsequent hospital encounters reported in this study may be underestimated, since this information is only captured when patients present to the same hospital within the Premier Hospital database. It is possible that some patients may have been counted more than once if they visited multiple different hospitals that ultimately feed into the Premier Hospital database. Additionally, as this hospital-level administrative data set does not include comprehensive patient historical data, such as history of MDD diagnoses or treatment, future research is needed on datasets with such components to determine if they are predictive factors in the decisions to admit or discharge patients. At least 700 hospitals across the US contribute data to the Premier Hospital database and a majority of these hospitals are additionally contributors to the AHA Annual Survey Database, which has relatively similar regional distribution representation (AHA─Midwest: 30%; Northeast: 12%; South: 37%; West: 20%; Premier─Midwest: 27%; Northeast: 15%; South: 44%; West: 15%) [Citation23]. However, our study results may not be generalizable to all patients with a hospital encounter for MDSI in the US or within specific regions. As such, although the findings of this study appear to indicate that in the West, patients with MDSI are more often treated in the ED setting only compared to patients in other US regions, further research is warranted. Since information on patient income is not available in the data source, we also could not assess whether treatment patterns or risk of a subsequent hospital encounter differed by income. The descriptive data in this study suggest that patients with MDSI who self-pay are more often treated in the ED setting only vs. an inpatient admission. However, further study of the impact of insurance status and the availability of financial resources on the choice of treatment setting for patients with MDSI is needed.

To ensure that the analyses in this study included the most complete patient treatment records in the ED and inpatient settings, we excluded those individuals discharged to other acute care facilities. Another limitation is that administrative hospital records are not collected for research purposes and may be subject to potential coding errors; this may be especially apparent with the challenge to accurately code suicidal ideation and behavior. Regarding the potential predictive factors of a subsequent MDD-related hospital encounter, other factors such as clinical assessment of depression severity and follow-up with outpatient mental health services were not available in the database and thus the estimates reported may be biased.

Conclusion

Our study reveals potential opportunities for hospital systems to explore optimizing utilization of antidepressant treatments, improve efforts to coordinate with outpatient mental health services and increase their accessibility, and identify the potential factors contributing to the high rates of 30-day subsequent hospital encounters among patients with MDSI, particularly among those with barriers to routine medical care. In this study we observed across a nationally representative sample of patients who presented to US hospitals with MDSI, that approximately one-half were seen in the ED and discharged, while the other half received inpatient services. Regardless of the initial care setting, many patients had costly subsequent hospital encounters, with over 40% occurring in the first month after discharge.

Declaration of interest

C Neslusan and J Voelker are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. M Lingohr-Smith and J Lin are employees of Novosys Health, which has received research funds from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC in connection with conducting this study and preparation of the manuscript.

Reviewer disclosure

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.5 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association: diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Hasin DS, Sarv AL, Meyers JL, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):336–346.

- SAMHSA.gov [Internet]. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54. Rockville (MD): Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2019 [ cited 2020 Aug 30]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf

- Citrome L, Jain R, Tung A, et al. Prevalence, treatment patterns, and stay characteristics associated with hospitalizations for major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2019;249:378–384.

- Ballou S, Mitsuhashi S, Sankin LS, et al. Emergency department visits for depression in the United States from 2006 to 2014. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;59:14–19.

- AHA.org [Internet]. TrendWatch: increasing access to behavioral health care advances value for patients, providers and communities. Washington DC: American Hospital Association; 2019 May [ cited 2020 Aug 30]. Available from: https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2019/05/aha-trendwatch-behavioral-health-2019.pdf

- AHA.org [Internet]. Behavioral health integration: treating the whole person. Washington DC: American Hospital Association; 2019 [ cited 2020 Aug 30]. Available from: https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2019/06/Market_Insights-Behavioral_Health_Report.pdf

- Yeh -H-H, Westphal J, Hu Y, et al. Diagnosed mental health conditions and risk of suicide mortality. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):750–757.

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, et al. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990-1992 to 2001-2003. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2487–2495.

- Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;362:1–8.

- Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Suicide rates in the United States continue to increase. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;309:1–8.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- APA.org [Internet]. Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2019 Feb 16 [ cited 2020 Aug 30]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/guideline.pdf

- Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Warden D, et al. Selecting among second-step antidepressant medication monotherapies: predictive value of clinical, demographic, or first-step treatment features. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(8):870–880.

- Rost K, Nutting P, Smith JL, et al. Managing depression as a chronic disease: a randomised trial of ongoing treatment in primary care. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):934.

- Cipriani A, Brambilla P, Furukawa TA, et al. Fluoxetine versus other types of pharmacotherapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Re. 2005;19(4):CD004185.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746–758.

- Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Halterman JS. Ambulatory care among young adults in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(6):379–385.

- Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Mani N, et al. Dependence on emergency care among young adults in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):663–669.

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20161878.

- Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, et al. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128:185–199.

- Abar B, Hong S, Aaserude E, et al. Access to care and depression among emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(1):30–37.

- Premier.com [Internet]. Premier Healthcare Database: data that informs and performs. Charlotte (NC): Premier Applied Sciences, the Research Division of Premier Inc.; 2020 Mar 2 [ cited 2021 Jan 28]. Available from: https://products.premierinc.com/downloads/PremierHealthcareDatabaseWhitepaper.pdf