ABSTRACT

Purpose

To evaluate real-world prescription digital therapeutic (PDT) use and associated clinical outcomes among patients with opioid use disorder (OUD).

Patients and methods

A real-world observational evaluation of patients who filled either a 12- or 24-week (refill) prescription for the reSET-O® PDT. The PDT content consists of 67 interactive lessons unlocked in sequence during use as well as the chance to earn rewards for progress and/or negative urine screens. Engagement/retention data (ongoing engagement in weeks 9–12, or 21–24) were collected via the PDT and analyzed with descriptive statistics. Substance use was evaluated as a composite of patient self-reports and urine drug screens (UDS). Missing UDS data were assumed to be positive. A regression analyses of hospital encounters for 12- vs. 24-week prescriptions controlling for covariates was conducted.

Results

In a cohort of 3,817 individuals with OUD who completed a 12-week PDT prescription, a cohort of 643 was prescribed a second 12-week ‘refill’ prescription, for a total treatment time of 24 weeks. Mean age of the 24-week cohort was 39 years, 56.7% female. At 24 weeks of total treatment: abstinence in the last 4 weeks of treatment was 86% in an analysis in which patients with no data are assumed to be positive for illicit opioids. Over 91% of patients were retained in treatment. An analysis of matched insurance claims showed that those treated for 24 weeks had a 27% decrease in unique hospital encounters compared to those who got the first 12-week prescription only.

Conclusions

These data present real-world evidence that a second prescription (24 weeks) of a PDT for OUD is associated with improved outcomes, high levels of retention, and fewer hospital encounters compared to a single prescription for a PDT.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Prescription digital therapeutics (PDTs) are software-based treatments that are FDA-authorized to improve clinical outcomes for serious diseases and conditions. The reSET-O PDT consists of 67 interactive lessons unlocked in sequence during use as well as the chance to earn rewards for progress and/or negative urine screens. Multiple studies show that a single 12-week PDT prescription for opioid use disorder (OUD) helps patients engage in treatment, reduces substance use, and helps patients remain in treatment, but to date there has been no evaluation of how patients who receive a ‘refill’ second prescription engage with the therapeutic and whether the positive effects on substance use and retention are durable across a second 12 weeks (total of 24 weeks) of treatment.

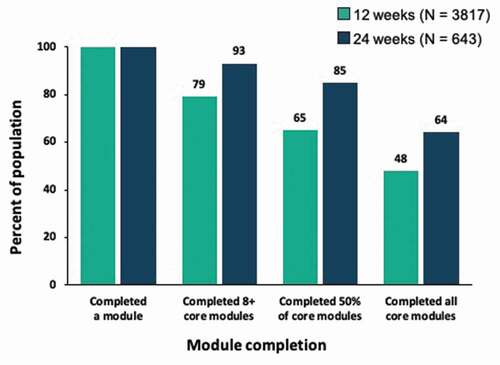

This real-world analysis evaluated 643 patients from 12 U.S. states who were prescribed a second PDT prescription. 93% of this cohort completed 8 or more core lesson modules in the second prescription period, 85% completed at least half of core modules, and 64% completed all 32 core modules. Patients used the PDT outside of clinic hours about 40% of the time. 94.4% of patients had 80% or greater negative reports of opioid use across the second 12 weeks of treatment. A 27% decrease in unique hospital encounters was observed in patients who completed a second prescription vs. patients who completed only one prescription.

These data show that a second prescription of a PDT for OUD is associated with postive patient outcomes. Patients showed durable and high levels of engagement with the PDT, reduced substance use, and improved treatment retention through 24 weeks of treatment.

Introduction

The epidemic of opioid use disorder (OUD) has burdened treatment centers and associated healthcare systems that are attempting to address the myriad needs of patients struggling with this disorder [Citation1]. Although medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) in combination with behavioral therapy, are standard treatments for OUD [Citation2], between 80% and 90% of those needing these therapies do not get them [Citation3]. The causes of this disparity between need and access are multi-factorial and include stigma about drug use and treatment, inability to pay for care, and geographical or logistical barriers to treatment [Citation1]. People living in rural areas are particularly disadvantaged because addiction specialists and substance use treatment centers are seldom readily available.

Behavioral therapy and psychosocial supports are key elements in any treatment plan for patients with OUD, and can increase engagement with, and retention in, treatment [Citation4]. Attrition from OUD treatment is a significant problem, with an estimated 30% dropout rate in the first month of therapy and attrition rates of 50% or higher within the first 3 months [Citation5-9]. Active engagement by patients in their treatment has been demonstrated to improve retention and chances for successful recovery [Citation10,Citation11].

Prescription digital therapeutics (PDTs) are software-based treatments evaluated for safety and effectiveness by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Prescribed and initiated by licensed clinicians such as physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, and delivered on mobile devices, PDTs may help overcome barriers to care and improve treatment outcomes.

reSET-O® received FDA market authorization in late 2018 as an adjuctive outpatient treatment for OUD combined with buprenorphine MOUD [Citation12]. The PDT’s therapeutic content is based on the community reinforcement approach (CRA), which is a validated addiction-specific form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [Citation13,Citation14].

The pivotal trial that served as the basis for FDA authorization showed that 82% of 170 adult OUD patients randomized to the PDT stayed in treatment vs. 68% of those who received treatment as usual. The likelihood of abstinence during weeks 9–12 of treatment was 77.3% vs. 62.1% (P < 0.05 for both comparisons) [Citation15,Citation16].

Although data supporting the efficacy of the PDT are robust, no real-world evaluation has been published analyzing how patients who refilled a prescription engage with the PDT and whether the positive effects on abstinence and retention are durable across a second 12-weeks (total of 24 weeks) of treatment. This real-world analysis evaluates patient engagement with the PDT as well as rates of opioid use and retention among a geographically diverse population of patients prescribed a second prescription and treated for 24 weeks.

Methods

This is a real-world retrospective observational evaluation of a cohort of patients under routine care by their clinician who filled an initial prescription for the reSET-O PDT between 1/1/19 and 12/31/20 (12-week cohort) and the subpopulation of these patients who were given a second ‘refill’ prescription with identical content (24-week cohort). All patients were diagnosed with OUD and were being treated with buprenorphine MOUD at clinician-determined doses, routes of administration, and regimens. Patients were treated in clinics located in 12 U.S. states in settings that included specialty clinics, primary care practices, academic medical centers, and telemedicine visits. Patient engagement with the PDT as well as other therapeutic use data (de-identified and patient-consented via terms of the service agreement) were collected and analyzed using descriptive statistics. The analysis of claims data received a waiver of authorization for the use and disclosure of protected health information and a determination of exempt status under 45 CFR § 46.104(d)(4) from Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB) on 2 April 2020. (WIRB is a fully-accredited independent institutional review board not affiliated with any specific authors or institutions.)

The PDT content consists of 67 interactive CRA modules (i.e., lessons) presented with text, audio, and video, which are unlocked in sequence during use. The first 32 modules are called ‘core’ modules and convey OUD-specific instruction and guidance. Each module delivers about 30 minutes of treatment, with 4 modules per week being the recommended dose. Already-completed modules can be repeated, but patients must complete the sequence of modules in the order prescribed.

Comprehension of, and proficiency with, therapeutic content is supported by ‘fluency training,’ which involves an interactive question-and-answer approach that immediately reinforces understanding after each lesson. The PDT also includes contingency management (CM) delivered via a virtual ‘rewards wheel.’ Patients receive CM rewards that are either virtual (‘thumbs up’ icon) or tangible (gift cards with values randomly chosen ranging from $5 to $100) for completion of therapy lessons (up to 4 per week) and negative drug urine screens. Patients complete assessments and can report and record substance use, cravings, and triggers at any time. Clinicians can access real-time patient-inputted data and monitor progress via a ‘dashboard’ on their own mobile device or computer. The PDT prescription length is 12 weeks (84 days), and subsequent prescriptions may be written by the prescriber for longer durations of treatment.

An ‘active day’ was defined as patient use of any PDT feature on a given day. The unit of treatment (‘dose’) was a 30-minute module. Patients were instructed to complete four modules per week.

Substance use was evaluated as a composite of patient self-reports, which were recorded via the PDT, and in-clinic urine drug screens (UDS) that were recorded by clinicians.

Two opioid use endpoints were analyzed. The primary endpoint was abstinence (i.e., no positive UDS or self-reports) during the last 4 weeks of the second PDT prescription period (weeks 21–24). Missing abstinence data for any given week was imputed either with a ‘missing data positive’ approach (i.e., patients with no data in the last 4 weeks were assumed to be positive) or with a ‘missing data excluded’ approach (i.e., patients with no data were excluded from analysis).

Substance use was also assessed with a responder analysis of patients who had ≥ 80% negative UDS or self-reports for the duration of their second 12-week prescription, a standard consistent with recommendations from the FDA [Citation17-19].

A retrospective analysis of health insurance claims (HealthVerity PrivateSource 20 claims database) was performed to assess the impact of PDT use among patients who completed a single prescription vs. those who completed a second prescription. The analysis evaluated the incidence of unique hospital encounters, which included emergency department, observation, inpatient, intensive care unit, and partial hospitalizations over a period of 9 months following the initiation of the first prescription (index date). Incidence and incidence rate ratios were evaluated from a negative binomial model of encounters, with an offset for the number of days in the post-index period (minimum of 12 weeks’ continuous eligibility was required) and adjusted for age, gender, and pre-index unique hospital encounters.

Results

Of the 3,817 individuals with OUD from 12 states in the U.S. who filled an initial 12-week PDT prescription (12-week cohort), 643 were prescribed a second 12-week ‘refill’ for a total treatment duration of 24 weeks (24-week cohort) ().

Available demographic data were limited to age and gender, which are the only characteristics collected via the PDT as part of user initiation. Mean age of the 24-week ‘refill’ cohort was 39 years, with 56.7% female, 30.1% male, and 13.1% with no data on self-reported gender.

Therapeutic Use/Patient Engagement

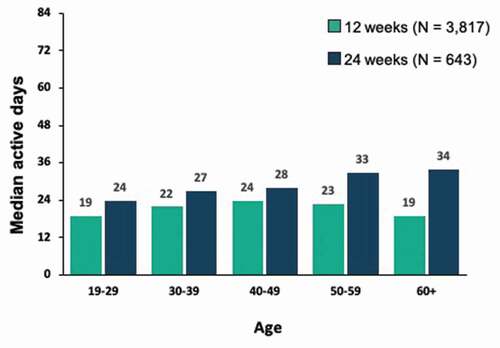

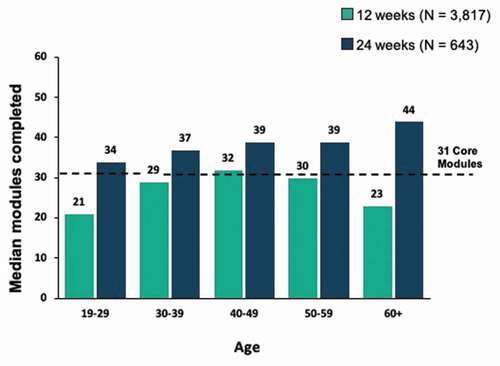

Engagement with the PDT, as defined by both number of active days and number of lessons completed among patients in the 24-week cohort, was relatively uniform across age brackets, with a trend toward increasing engagement with older age and higher levels at each age bracket, whereas the distribution of active days and lessons completed by age was more uniform in the 12-week cohort ().

In the 24-week cohort, 93% completed eight or more core modules, 85% completed at least half of core modules, and 64% completed all 32 core modules, all of which were higher than corresponding rates in the 12-week cohort ().

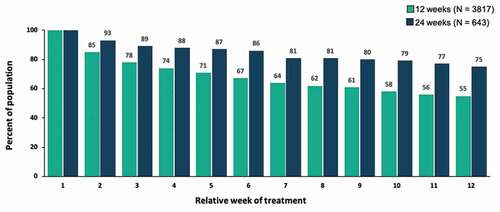

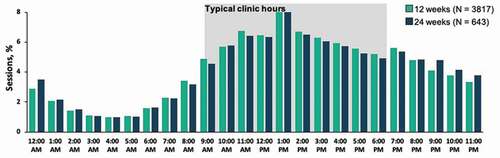

Engagement as measured by percentage of patients in the 24-week cohort with an active day remained high over the course of the second prescription, from 93% after week 2 to 75% after week 12, with engagement higher at each week than the mean rates for patients with only a single prescription (). Patients used the PDT outside of normal clinic hours (i.e., 9 a.m. – 6 p.m.) about 40% of the time, with little differences noted between the 12-week and 24-week cohorts ().

Substance use and retention

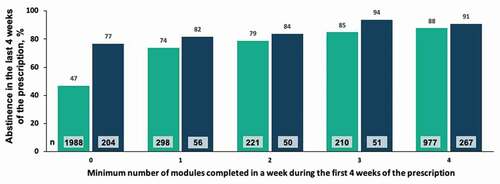

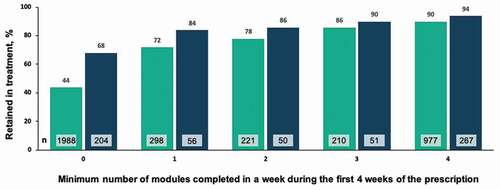

In the 24-week cohort, 94.4% met the responder rate of being abstinent for at least 80% of the weeks of treatment. In an analysis of abstinence in the last 4 weeks of treatment (i.e., weeks 21–24 of 24), 86% of patients were abstinent in an analysis where patients with no data are assumed to be positive, and 94% were abstinent in an analysis where 59 patients with no data were excluded (n = 584). The majority of patients (91.4%) were retained in treatment at the end of the second prescription period (i.e., were active in weeks 21–24 of 24). A positive correlation was observed between minimum number of modules completed each week during of the first 4 weeks of the second prescription (i.e., weeks 13–16 of 24) and abstinence at the end of treatment (). A similar correlation was observed between minimum number of modules completed each week during the first 4 weeks of the second prescription (weeks 13–16) and retention in treatment (), with modestly higher levels again observed in the 24-week cohort compared to the 12-week cohort.

Healthcare Utilization

A retrospective analysis of healthcare utilization identified claims for 324 patients who completed one reSET-O prescription, and for 103 patients who completed a second prescription. The incidence of unique hospital encounters after PDT initiation was 0.46 for those with 2 prescriptions vs. 0.63 for those with a single prescription (p > 0.05), which represents an additional 27% decrease after 24 weeks of treatment ().

Table 1. Comparison of unique hospital encounters among patients with available insurance claims data

Discussion

These real-world observational data support and complement evidence from prior RCTs demonstrating the efficacy of the reSET-O PDT for improving abstinence and treatment retention [Citation16,Citation20]. Health economic analyses show net cost reductions among PDT users compared to patients not using the PDT [Citation21,Citation22]. These real-world data represent the first evaluation suggesting that individuals with OUD across age categories engage with a refill prescription for a PDT (24 weeks of treatment), and that this engagement is associated with robust levels of clinical and health outcome improvements, including abstinence, retention in treatment, and reduction in unique hospital encounters (ER, in-patient, and ICU stays) relative to patients treated for 12 weeks.

Even though the patients evaluated in this population had already completed lessons in the PDT, their engagement with a second prescription (13–24 weeks) (i.e., number of core lessons completed) was high.

The data also reveal positive associations between engagement with the PDT early in treatment and abstinence in the last 4 weeks of treatment. A preliminary hypothesis to explain this pattern is that patients who receive a second prescription have additional opportunities for reviewing and putting into practice the content from the PDT that best suits their individual recovery journey. This may reinforce and strengthen their abilities to cope with triggers and cravings and to better manage relationships, stress, or social pressures to use, all of which may decrease their exposure to, and use of, illicit opioids.

In addition, an analysis of matched insurance claims showed that those treated for 24 weeks had a 27% decrease in unique hospital encounters compared to those who got the first 12-week prescription only. This reduction is consistent with a recently-published retrospective 6-month pre/post analysis of real-world claims data from 351 patients using the same PDT [Citation21].

These findings are timely and relevant because, despite substantial expansion of medication-assisted-treatment providers, the current rates of OUD and overdoses are worsening, which suggests that existing strategies and approaches are not working, most likely due to patients continuing to face significant barriers to treatment, such as limited time, resources, and stigma [Citation23,Citation24].

Limitations

The data in this study were recorded directly by patients using their PDTs, by clinicians using the PDT dashboard, or that were automatically captured by the software and the mobile device log. As such, these data were derived from a mixed population of patients who were at various stages of treatment and whose use of the PDT may have been inconsistent or sub-optimal. Due to limitations in the kinds of data provided by claims data, we at present lack demographic data beyond age, sex, and location.

The accuracy of abstinence data is limited by variations in the timing and frequency of urine drug screens by different clinics and by uncertainty in the accuracy of patient self-reports. Self-reported drug use has been shown, in some studies, to be relatively highly correlated to results from objective assessments, although the accuracy varies by the drug of abuse [Citation25].

These results should be interpreted within the context of real-world data that reflect variable practice patterns among clinicians, the potential for selection bias in the 24-week cohort, and the potential bi-directionality of causation. Although the decision to obtain a second PDT prescription was patient-driven and no external criteria were used that would limit who could obtain a refill, it is possible that the patients who requested a refill differed in some important ways from those who did not, for example, by being at a more advanced stage of recovery. However, it is important to underscore that patients who stay in recovery longer have greater long-term abstinence rates, and that it is likely that patients with a second prescription are exhibiting greater engagement with this OUD therapeutic because it is relevant to specific aspects of their recovery, including how to effectively manage cravings, negative thoughts, receiving feedback, and being more assertive, among others. Further research controlling for potential confounding, such as with randomization or creation of cohorts matched for gender, age, and location, is warranted to explore the associations observed here.

Conclusions

These analyses suggest that in a real-world population, patients with OUD had higher engagement with a refill prescription of a PDT vs. patients with one prescription filled, and showed durable and high levels of self-reported abstinence and treatment retention. Patients treated with the PDT for 24 weeks had a 27% lower rate of unique hospital encounters compared to those treated for 12 weeks.

Declaration of interest

Dr. Maricich, Dr. Gerwien, and Dr. Valez are employees of Pear Therapeutics, Inc. Ms. Kuo is a former employee of Pear Therapeutics, Inc. Dr. Malone has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Mancher M, AI L, editors. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; eng., 2019.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. 2015.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed Tables. In: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2017; 2018.cited from: https://www.samhasa.gov

- Mansson KN, Salami A, Frick A, et al. Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2016 2;Feb(6):e727.

- Stark MJ. Dropping out of substance abuse treatment: a clinically oriented review. Clin Psychol Rev. 1992;12:93–116.

- Simpson DD. Treatment for drug abuse. Follow-up outcomes and length of time spent. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981 Aug;38(8):875–880.

- Kang SY, Kleinman PH, Woody GE, et al. Outcomes for cocaine abusers after once-a-week psychosocial therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1991 May;148(5):630–635.

- Harris PM. Attrition Revisited. American Journal of Evaluation. 19(3)293–305 1998.

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychol Addict Behav. 1997;11(4):294–307.

- Hser YI, Evans E, Huang D, et al. Relationship between drug treatment services, retention, and outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2004 Jul;55(7):767–774.

- Marchand KI, Oviedo-Joekes E, Guh D, et al. Client satisfaction among participants in a randomized trial comparing oral methadone and injectable diacetylmorphine for long-term opioid-dependency. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Jul;26(11):174.

- De Novo Classification Request for reSET (DEN160018). editors. In: Health CfD, Radiological. Washington, DC: U.S. Food & Drug Administration; 2017.

- Marsch LA, Guarino H, Acosta M, et al. Web-based behavioral treatment for substance use disorders as a partial replacement of standard methadone maintenance treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014 Jan;46(1):43–51.

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST. Therapy manuals for drug addiction, a community reinforcement plus vouchers approach: treating cocaine addiction. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1998.

- Pear Therapeutics I reSET-O [clinician directions for use]. 2019.

- Christensen DR, Landes RD, Jackson L, et al. Adding an internet-delivered treatment to an efficacious treatment package for opioid dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014 Dec;82(6):964–972.

- Haight BR, Learned SM, Laffont CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for opioid use disorder: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019 Feb 23;393(10173):778–790.

- Lofwall MR, Walsh SL, Nunes EV, et al. Weekly and Monthly Subcutaneous Buprenorphine Depot Formulations vs Daily Sublingual Buprenorphine With Naloxone for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jun 1;178(6):764–773.

- Food & Drug Administration. Opioid use disorder: endpoints for demonstrating effectiveness of drugs for medication‐assisted treatment guidance for industry [September 29, 2020]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/opioid-use-disorder-endpoints-demonstrating-effectiveness-drugs-medication-assisted-treatment

- Campbell AN, Nunes EV, Matthews AG, et al. Internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2014 Jun;171(6):683–690.

- Velez FF, Colman S, Kauffman L, et al. Real-world reduction in healthcare resource utilization following treatment of opioid use disorder with reSET-O, a novel prescription digital therapeutic. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2021 Feb;21(1):69–76.

- Wang W, Gellings Lowe N, Jalali A, et al. Economic modeling of reSET-O, a prescription digital therapeutic for patients with opioid use disorder. J Med Econ. 2021 Jan-Dec;24(1):61–68.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 month-ending provisional number of drug overdose deaths by drug or drug class [September 28, 2020]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- Spencer MR, Warner M, Bastian BA, et al. Drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl, 2011-2016. National Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(3):108.

- van den Berg JJ, Adeyemo S, Roberts MB, et al. Comparing the Validity of Self-Report and Urinalysis for Substance Use among Former Inmates in the Northeastern United States. Subst Use Misuse. 2018 Aug 24;53(10):1756–1761.