Abstract

To describe the nutritional and functional changes that occurred in older patients with a femur fracture following a dietary intervention and oral nutritional support implemented at an orthogeriatric unit in Aragon, Spain. Open-label, prospective study. Patients were consecutively recruited and arranged into three groups based on their CONtrolling NUTritional (CONUT®) score and nutritional needs. Nutritional status was assessed while in hospital, and at 45-, 100- and 180-days post-hospital discharge. One hundred and sixty-nine patients [mean age: 86 years (SD ± 5.48)] were recruited (July 2017 to January 2020). At admission, 53.3% were at risk of malnutrition; 26.6% were malnourished; 20.1% were well-nourished. Variable proportions of malnourished patients at admission were well-nourished 45-, 100-, and 180-days post-discharge. CONUT® and Barthel index correlations showed that as nutritional status enhanced, patients gained functionality. Dietary interventions and nutritional support may help restoring the nutritional and functional status of older patients with a femur fracture.

Introduction

The incidence of femur fractures increases exponentially with age as a result of a decrease in bone mass and an increase in falls.Citation1 In Spain, about 36,000 femur fractures occur in the aged population each year, with an incidence of 500–600 cases per 100,000 older patients-year.Citation2 Malnutrition can be present in up to 63% of older people with a bone fracture.Citation3 Diaz de Bustamante et al.Citation4 found protein malnutrition and vitamin D deficiency were common while low energy, mixed malnutrition, and sarcopenia were present in about one-fifth of the 509 femur fracture patients studied.

The magnitude of the problem is significant as poor nutritional status is one of the major contributors to postoperative complications of the restorative surgery.Citation5 Malnutrition is associated with impaired muscle function, delayed wound healing, physical disability, low mental function, prolonged rehabilitation time, loss of independency, decreased quality of life, and increased mortality, both during and after hospital admission.Citation6 In this sense, dietary protein intake plays a crucial role in both preventing and recovering bone fracturesCitation7 and a higher consumption of total proteins has been associated with a reduced risk of hip fracture in older men and women.Citation8 The adequate intake of proteins may benefit bone mineral density and may help to reduce the amount of muscle mass lose in older adults.Citation9 Proteins requirements are higher in the older population compared to their younger counterparts, and therefore a larger consumption of proteins is recommended.Citation10 Postoperative oral nutritional supplementation aligned to requirements improves hip fracture outcomes, recovers nutritional status to near-optimum levels, and decreases complications.Citation11

Malnutrition in the aged adult may not always be evident in the clinical evaluation that is routinely done by healthcare professionals who are not trained to identify this condition.Citation12 Thus, a specialized dietitian assessment and intervention becomes effective to tailor recommendations to needs and to improve the quality of the nutritional support.Citation12–14 The utilization of screening tools, such as the CONtrolling NUTritional status (CONUT®) or the short form of the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA®-SF) allows an easy, first-line appraisal of the nutritional status of aging inpatients.Citation15,Citation16 CONUT® scores use routine laboratory testing, and can be applied for pre–and post-operative nutritional management; to predict complications and 1-year survival in patients with serious illnesses undergoing surgery.Citation17 Likewise, the MNA®-SF comprises anthropometric measurements (body mass index, weight loss); global assessment (mobility); and dietary questionnaire and subjective assessment (food intake, neuropsychological problems, acute disease).Citation18 Preoperative malnutrition measured by the MNA®-SF has been associated with mortality in aged adults with hip fracture.Citation19

The aim of this study was to describe the nutritional changes that occurred in older patients with a femur fracture after refining dietary practices and providing oral nutritional support during hospital admission and outpatient follow up. The research sought to depict any potential relationship between the nutritional support provided and changes in patients’ nutritional status, capacity to perform activities of daily life, cognition, and quality of life. Additionally, the study explored what was the patients’ adherence to dietary recommendations and oral supplementation offered by a multidisciplinary team at an orthogeriatric unit in everyday practice.

Materials and methods

Design

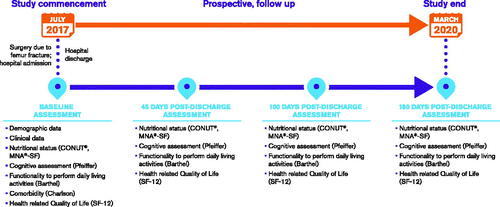

The study was a descriptive, prospective, open-label, real-world research on the health and nutritional outcomes of optimizing dietary habits and providing nutritional support to older patients after surgery due to femur fracture. Patients were admitted to the orthogeriatric unit at the Geriatric ward of Nuestra Señora de Gracia hospital in Zaragoza, Spain and were consecutively enrolled up to 72 h before or within 24 h after surgery to femur fracture (). Participants were assessed at 4 study timepoints: at baseline (in-hospital assessment), and at 45 days, 100 days, and 180 days after hospital discharge, respectively. After discharge from the hospital, patients were followed in the outpatient clinic. Telephone calls were made 15 days after discharge and after the 45- and 100-day visits to solve doubts and to assess the general, functional, and cognitive status of patients as well as their appetite and adherence to dietary and nutritional recommendations. Recruitment for the study took place from 11th July 2017 to 23rd January 2020. Due to the SARS-COV 2 pandemic, the study follow up was stopped on 30th April 2020. Two geriatricians (S.S and P.M.), a specialist nurse (G.L.), and a dietitian (A.C.) assessed the patients during admission and follow up and carried out dietary education tasks (G.L. and A.C.) upon discharge from hospital and during follow up (study investigators).

Population

Patients accomplishing the following inclusion criteria were eligible to entry the study: being admitted to the orthogeriatric unit at the Geriatric ward of Nuestra Señora de Gracia hospital in Zaragoza, Spain; with a diagnosis of femur fracture requiring surgery; age ≥70 years; with laboratory tests, including albumin levels, total cholesterol levels and lymphocyte count being performed within 6 months before fracture as required to calculate the CONUT scores; able to give written consent for study participation. Patients were excluded if declining, unwilling, or intolerant to dietary interventions or to oral nutritional supplementation despite indication; being on enteral nutrition; being diagnosed with concomitant serious illnesses significantly compromising the nutritional status of the patient: cancer at any level of the digestive tract (except colon cancer); chronic inflammatory diseases at any level of the digestive tract; any advanced or end-stage disease in view of the medical team.

Assessments

Baseline demographic (age, gender, marital status, maximum level of education, place of residence), clinical (type of fracture; pharmacological treatments; laboratory tests results; morbidity, cognition; independence to perform activities of daily life), and quality of life data was collected.

Assessment of nutritional status

The nutritional status of patients was assessed using CONUT® scoreCitation15 (Supplementary Table 1). The MNA®-SF score was calculated additionally.Citation16,Citation20,Citation21

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

The CONUT® score considers serum albumin, total cholesterol level, and total lymphocyte count to assess protein reserves, caloric depletion, and immune performance, respectively, usually compromised by undernutrition in hospitalized patients. Based on a screening total CONUT® score, patients are grouped into normal nutritional status (0–1 points) or light (2–4 points), moderate (5–8 points), and severe (9–12 points) undernutrition. Although it is a well-validated screening tool, with high sensitivity, specificity, and reliability, the criteria applied for grouping patients vary considerable across studies.Citation17,Citation22,Citation23 In this study, the researchers assigned patients to one of three groups according to their CONUT® score and the corresponding alert for malnutrition: group 1, malnutrition (high CONUT® score; high alert: 5–12 points); group 2, at risk of malnutrition (intermediate CONUT® score; moderate alert: 2–4 points); group 3, normal nutrition (low CONUT® score; low alert: 0–1 points) as commonly done in practice (Supplementary Table 1). Lymphocyte count and total cholesterol decreases were assigned 0, 1, 2, and 3 points while albumin reduction was given 0, 2, 4, and 6 points according to the severity.

The MNA-SF test comprises simple measurements and six questions that can be completed in <5 min: anthropometric measurements (body mass index, weight loss); global assessment (mobility); and dietary questionnaire and subjective assessment (food intake, neuropsychological problems, acute disease). A total score of MNA-SF <8, 8–11, and >11 indicates malnutrition, risk of malnutrition, and no malnutrition, respectively.Citation18

Dietary interventions

The researchers designed a new-in-hospital diet model for the patients taking part in the study, named the Hip Diet. The Hip Diet consisted of fortifying the diet with an extra intake of milk at mid-morning on top of the usual menu, and of tailoring the dietetic recommendations to the needs of the individual at discharge from hospital, and during follow-up.

Based on the CONUT® score and the group being assigned to, patients received different dietary interventions according to the recommendations of the 2016 Spanish Society of Community Nutrition.Citation24 The following dietary interventions were recommended during hospital admission, at discharge, and at each follow up assessment post-discharge to either preserve an adequate nutritional status in well-nourished patients or to improve the nutritional status in those malnourished or at risk of malnutrition:

• Group 1 (malnourished, high CONUT® score): energy, protein, and calcium enriched diet; oral nutritional supplement (2 bottles/day) during admission and at discharge.

• Group 2 (risk of malnutrition, intermediate CONUT® score): energy, protein, and calcium enriched diet; oral nutritional supplement (2 bottles/day) during admission; at discharge, energy, protein, and calcium enriched diet recommendations.

• Group 3 (well-nourished, low CONUT® score): calcium enriched diet during admission and at discharge.

The oral nutritional supplement was hypercaloric (151 kcal/100 ml) and hyperproteic (10.4 g/100 ml) with 100% serum lactoprotein enriched in leucine and vitamin D. Patients were advised to take two bottles (200 ml/bottle) per day. The composition of the oral nutritional supplement is shown in Supplementary Table 2. There is substantiation evidence suggesting that older adults who have acute or chronic diseases need a high intake of proteins to maintain and regain lean body mass and function (PROT-AGE study).Citation10 Similarly, consuming a combination of vitamin D, calcium and leucine-enriched whey protein supplement has shown positive effects on the bone health of older adults (PROVIDE study).Citation25

Table 2. CONUT® mean scores at hospital admission, discharge, and during study follow up.

The goal was to secure a minimum of 30 kcal/kg body weight/day and sufficient intake of proteins as recommended in the older patient (healthy: 1.0–1.2 g/kg body weight/day; with an acute or chronic condition: 1.2–1.5 g/kg body weight/day; with a serious disease or malnutrition: 2 g/kg body weight/day).Citation26

Dysphagia patients were given a texture-modified diet with an equivalent nutritional and caloric composition to that of patients without dysphagia; a thickener was also used for liquids.Citation27 An oral cream-type nutritional supplement was also recommended when needed. Diabetes patients were given specific formulations of a hypercaloric and hyperproteic oral nutritional supplement.

At hospital discharge, only malnourished patients (CONUT group 1) and patients reporting a lower than desirable caloric intake to accomplish the essential protein and energy requirements were prescribed the oral nutritional supplement. Additionally, patients and caregivers were provided with dietary and nutritional information and education, including a leaflet containing recommendations for healthy habits (i.e., physical exercise routines; advice for sun exposure, and a weekly menu based on aliments rich in calcium and vitamin D) (Supplementary Table 3). Leaflets were designed and adapted to provide nutritional information specific to each CONUT® group.

Table 3. Number of patients assigned to different CONUT® groups based on the variation of their nutritional status at 45, 100, and 180 days from hospital discharge.

To take a modified texture diet and/or supplement, specific to the condition and a thickener in liquids was advised for all dysphagia patients. The choice of the supplement suitable to each patient was made by the clinical judgment of the specialist.

During hospital admission and follow up, a dietitian supervised the nutritional and hydration status of patients and adapted recommendations to individual needs and habits to ensure sufficient calcium, protein, and caloric intake. At each assessment during follow up, patients varied their CONUT® score based on changes in their nutritional status. Dietary and nutritional recommendations changed accordingly ().

Assessment of functionality, comorbidity, cognition, and health-related quality of life assessments

The patient’s ability to perform basic activities of daily living was assessed using the Barthel index.Citation28 It measures functional independence in the domains of personal care and mobility in patients with chronic, disabling conditionsCitation28 <20 points indicate total dependency; 20–40 points, severe dependency, 45–55 points, moderate dependency; ≥60–95 points, mild dependency; 100 points means independence (higher score, greater independence, and functionality).Citation29 Comorbidity was measured with the Charlson comoborbidity index, an assessment tool designed specifically to predict long-term mortality.Citation30 It was first developed as a weighted index to predict the risk of death within 1 year of hospitalization for patients with specific comorbid conditions. Nineteen conditions were included in the index. Each condition is assigned a weight from 1 to 6, based on the estimated 1-year mortality hazard ratio from a Cox proportional hazards model. These weights are summed to produce the Charlson comorbidity score.Citation31 Cognition was assessed with the Pfeiffer test, a short mental status questionnaire, in which a score above 3 points suggests mild cognitive impairment (higher score, worse cognition).Citation32 Health-related quality of life was evaluated with the 12-Item Short-Form (SF-12) Health Survey, a self-reported outcome assessment of the impact of health on six domains of an individual’s everyday life.Citation33

Assessment of adherence to dietary recommendations

Adherence to dietary recommendations and oral nutritional supplements was assessed during hospital admission, at discharge, and at each follow up assessment with a short, ad hoc questionnaire, created for the particular purpose of assessing adherence in this study. The healthcare provider judged patients’ adherence as excellent, good, or poor on a Likert-type scale.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied. The study sample was divided into categorical subgroups of patients who were malnourished, at risk of malnutrition, or well-nourished during hospital admission and follow up. The percentage of malnourished, at risk of malnutrition, or well-nourished patients at each study assessments (hospital admission, at 45, 100, and 180 days after hospital discharge, respectively) according to CONUT® scores was estimated. Percentages, mean, standard deviation, median, interquartile range, and minimum and maximum range were calculated. Non-parametric tests were used to assess the correlation between the CONUT® mean scores and length of hospital stay, Barthel index, Charlson index, Pfeiffer test, and SF-12 questionnaire scores. The correlation between the CONUT® mean scores and level of adherence to dietary recommendations was also assessed. Additionally, correlations between the MNA®-SF mean scores and the Barthel index, Charlson index, Pfeiffer test, and SF-12 questionnaire scores were also calculated. Data was analyzed with SPSS® 2019.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the clinical research ethical committee for the Aragon region in Spain given the corresponding location of the Nuestra Señora de Gracia hospital in Zaragoza (CP-CI PI17/0178).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

A total of 169 patients [mean age: 86 years (SD ± 5.485)] accomplished the inclusion criteria and were recruited into the study between July 2017 and January 2020 ( and Supplementary Table 4). This figure corresponds to 39% of all patients admitted to femur fracture in the Orthogeriatric Unit. There were 78% female participants; 63.9% were widows and 77.5% attained the primary level of education as the highest. Before being admitted into the hospital, 45.6% of patients lived in their own homes with a family member.

Table 4. Barthel index score variation during follow up amongst the CONUT® groups defined during hospital admission.

55.17% of patients had a trochanteric fracture; 36.7 and 34.3% had no or high comorbidity, respectively; 61.5% had some cognitive impairment (). Before hospital admission due to the femur fracture, antihypertensives (61.5%), anxiolytics (39.7%), and diuretics (39.1%) were the drugs patients most frequently received; 37.9% were on iron, calcium, or vitamin supplements. 73.37% were independent or need minimal help to perform activities of daily life.

Nutritional status at hospital admission and during follow up based on CONUT® mean score

At hospital admission, 53.3% of patients were at risk of malnutrition based on CONUT® scores (). The overall median length of hospital stay was 12 days, with a dispersion around the median (interquartile range (IQR) p75–25) of 9 days (range: 8–17). There was a positive correlation between the length of hospital stay and the risk of malnutrition based on CONUT® scores at admission. A higher risk of malnutrition (higher CONUT® scores) was significantly correlated to a longer length of hospital stay (r2 = 0.171; p = 0.031).

The first follow up assessment (45 days visit) was made 40–50 days after hospital discharge, the second follow up assessment (100 days visit) took place 95–105 days and the third follow up assessment (180 days visit) happened 175–185 days after hospital discharge, respectively, according to usual clinical practice.

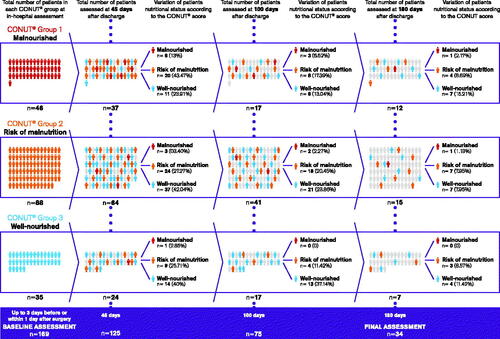

From a total of 169 patients assessed at hospital admission, 125 were visited 45 days, 75 were assessed 100 days and 34 were evaluated 180 days after hospital discharge because they had the required laboratory tests to calculate the CONUT® score ().

One hundred and twenty-two (72.2%) patients were lost to follow up. One hundred and seven patients did not have laboratory tests performed or did not attend the follow-up visits due to deterioration of their health or due to cancelation because of the SARS-COV-2 pandemic. Additionally, 11 deaths happened: six of them within the first 45 days after hospital discharge. No significant baseline differences were observed between patients lost to follow up at 45, 100, and 180 days, respectively, and patients completing the study from the first to last assessment (Supplementary Table 5).

Patients’ nutritional status remained very much the same while in the hospital with a CONUT® mean score of 3.19 (SD: 2.09) at admission and of 3.71 (SD: 2.19) at discharge. During follow up, CONUT® mean scores were 1.85 (SD: 1.78), 1.65 (SD: 1.64), and 1.58 (SD: 1.59) at 45 days, 100 days, and 180 days post-discharge from the hospital, respectively ().

CONUT® nutritional status at hospital admission and during follow up

Considering CONUT® risk groups, 91.4% of patients well-nourished at admission remained very much the same at discharge from the hospital (n = 32/35). The same percentage of patients at risk of malnutrition at admission continued with the same risk at discharge (88 patients, 100%) while the proportion of malnourished patients decreased by 8.7% from admission to discharge (n = 46/42).

45 Days nutritional assessment

At 45 days from hospital discharge, sufficient laboratory test data to assess changes between groups at risk of malnutrition based on CONUT® scores was available for 125 patients. A total of 37 patients who were malnourished at hospital admission (CONUT® Group 1) were assessed 45 days after discharge: six patients (13.04%) remained malnourished; 20 patients (43.47%) were at risk of malnutrition and 11 patients (23.91%) were well-nourished. Likewise, out of a total of 64 patients who were at risk of malnutrition at admission (CONUT® group 2), three patients (3.40%) were malnourished, 24 patients (27.27%) remained at risk of malnutrition and 37 patients (42.04%) were well-nourished. Amongst the 24 patients who were well-nourished while in the hospital (CONUT® group 3), nine patients (25.71%) were at risk of malnutrition and 14 patients (40%) persisted well-nourished 45 days after discharge ().

100 Days nutritional assessment

At 100 days from hospital discharge, sufficient laboratory test data was available for 75 patients. A total of 17 patients who were malnourished at hospital admission (CONUT® Group 1) were assessed 100 days after discharge: three patients (6.52%) remained malnourished, 8 patients (17.39%) were at risk of malnutrition and six patients (13.04%) were well nourished based on CONUT® scores. Likewise, out of a total of 49 patients who were at risk of malnutrition at admission (CONUT® group 2), two patients (2.27%) were malnourished, 18 patients (20.45%) remained at risk of malnutrition and 21 patients (23.86%) were well-nourished. Amongst the 17 patients who were well-nourished while in the hospital (CONUT® group 3), four patients (11.42%) were at risk of malnutrition and 13 patients (37.14%) continued well-nourished 100 days after discharge from the hospital ().

180 Days nutritional assessment

At 180 days from hospital discharge, sufficient laboratory test data was available for 35 patients. From a total of 12 patients who were malnourished at hospital admission (CONUT® Group 1), one patient (2.17%) remained malnourished, four patients (8.69%) were at risk of malnutrition, and seven patients (15.21%) were well-nourished based on CONUT® scores. Out of 15 patients who were at risk of malnutrition at hospital admission (CONUT® Group 2), one patient (1.13%) was malnourished, seven patients (7.95%) remained at risk of malnutrition, and seven patients (7.95%) were well-nourished. Amongst the seven patients who were well-nourished at admission (CONUT® Group 3), three patients (8.57%) were at risk of malnutrition, and four patients (11.42%) remained well-nourished ().

CONUT® nutritional status and capacity to perform basic activities of daily living

The Barthel (functionality to perform activities of daily living) index score before hospital admission due to surgery of femur fracture was taken as reference to patients’ usual capacity to perform activities of daily living.

The proportion of patients with Barthel index scores below 60 at admission was similar amongst the different CONUT® risk groups ().

Before hospital admission, 91.3% (n = 42) of malnourished patients (CONUT® Group 1), 86.4% (n = 76) of patients at risk of malnutrition (CONUT® Group 2) and 82.9% (n = 29) of well-nourished patients (CONUT® Group 3) had a Barthel score below 60 points which is indicative of dependency to perform activities of daily living. No patients in any CONUT® group were fully independent to perform activities of daily living (Barthel index score 100 points) before admission ().

During follow up, amongst the malnourished patients (CONUT® Group 1), 61.5% (n = 24), 57.1% (n = 16), and 30.8% (n = 4) remained registering Barthel scores below 60 points at 45-, 100-, and 180-days post discharge from hospital, respectively. However, 5.1% (n = 2), 7.1% (n = 2), and 7.7% (n = 1) were independent (Barthel score of 100 points) to perform basic activities of daily living at the same points in time.

Amongst patients at risk of malnutrition (CONUT® Group 2) at admission, 65.2% (n = 43), 51.9% (n = 27), and 50.0% (n = 13) had a Barthel score below 60 points while 1.50% (n = 1) and 7.7% (n = 4) scored 100 points at 45- and 100-days from hospital discharge, respectively.

Amongst the well-nourished patients (CONUT® Group 3) at admission, 36.0% (n = 9), 34.8% (n = 8), and 14.3% (n = 1) scored below 60 points in the Barthel index at 45-, 100-, and 180-days from hospital discharge, respectively. Independence to perform activities of daily living was documented for 7.7% (n = 1) and 28.6% (n = 2) of patients 45- and 180-days post-hospital discharge ().

There was no correlation between CONUT® and Barthel index scores at hospital admission (p = 0.099) or hospital discharge (p = 0.234). At 45- (p = 0.643) and at 180- (p = 0.246) days post-discharge there was no correlation between CONUT® and Barthel index scores. At 100 days post-discharge there was a correlation between CONUT® and Barthel index scores (p = 0.003): as nutritional status improved, patients gained greater independence.

CONUT® nutritional status, comorbidity, cognition, and health-related quality of life

There was no correlation between the risk of malnutrition in the CONUT® scores, the Charlson (comorbidity) index (r = 0.016; p = 0.83), and the Pfeiffer (cognition) test scores (r = 0.072; p = 0.35) at hospital admission. Only at the 100 days post-discharge assessment, lower Pfeiffer scores (better memory and orientation) correlated with higher CONUT® risk scores (p = 0.006). There was no correlation between CONUT® risk scores and health-related quality of life scores in the SF-12 questionnaire at any study assessment point (r = 0.075; p = 0.33).

MNA®-SF nutritional status, capacity to perform activities of daily living, comorbidity, cognition, and health-related quality of life

The mean MNA®-SF (nutritional status) score for the sample (n = 169) at hospital admission was 11.56 (SD = 2.33). During follow up, the mean MNA®-SF score was 9.96 (SD: 2.73) at 45 days; 11.26 (SD: 2.44) at 100 days, and 11.47 (SD: 2.12) at 180 days after hospital discharge.

There was a moderate to low positive linear association between the MNA®-SF and the Barthel index scores at admission: higher MNA®-SF scores were associated with higher Barthel index scores (r = 0.456; p < 0.001).

There was no association between the MNA®-SF scores and the Charlson index (p = 0.074). However, a statistically significant inverse correlation (negative direction) was observed between the MNA®-SF and the Pfeiffer test scores at admission, and at 45- and 100 days post-discharge assessments (p < 0.001). As the nutritional status of the patients tended to improve (higher score on the MNA®-SF), their Pfeiffer scores tended to decrease implying an enhanced cognitive performance. This association was moderate to low (r = −0.447 at baseline; −0.585 at 45 days and −0.556 at 100 days post-discharge) and loses significance at the 180 days post-discharge assessment.

There was a statistically significant positive correlation between MNA®-SF scores and the health-related quality of life SF-12 score at admission and at 45 days follow up (p = 0.006 and p = 0.031 respectively). As patient’s nutritional status tended to improve, the perception of their health-related quality of life also got better.

Adherence to dietary recommendations

Overall, adherence to dietary recommendations and nutritional supplements according to health professionals was good. 69.5% (n = 114) of patients adhered adequately to the diet and 83.7% (n = 128) to nutritional supplements during hospital admission. During follow up post-discharge from the hospital, patients at a higher risk of malnutrition according to the CONUT® score adhered better to the dietary recommendations and oral nutritional supplements than those who had a better nutritional status (Kendall’s tau coefficient = 0.141). Likewise, patients with greater functional capacity and independence to carry out their activities of daily living adhered less adequately than those dependent on caregivers. The total score on the Barthel index tended to decrease with the level of adherence to both dietary recommendations (p = 0.036) and oral nutritional supplements (p = 0.003).

Discussion

This prospective, real-world study depicted the nutritional status of older patients admitted into an orthogeriatric hospital unit due to a fracture of the femur, and after restorative surgery. The study described the modifications in the nutritional status that can be expected as a result of adopting a multidisciplinary approach to the nutritional care of the aged patients in hospital practice. According to CONUT® scores, more than half of patients in this research were at risk of malnutrition on admission while a smaller proportion of patients were either malnourished or well-nourished. These findings were in line with other studies. However, the prevalence of malnutrition varies widely depending on the sources consulted and the assessment tools used.Citation34,Citation35 For instance, Malafarina et al.Citation36 reported 47.9% risk of malnutrition and 18.3% of malnourished patients using the MNA®-SF scores in a study designed to establish the effectiveness of oral supplementation to prevent muscle loss and sarcopenia in patients with hip fracture admitted to a Spanish hospital. In a retrospective analysis of data from a single community-based hospital in Japan, Yagi et al.Citation6 found that malnutrition was present in 78.7% of hip fracture older patients based on CONUT® scores. In Italy, Mazzola et al.Citation37 reported that 44.6 and 18.8% of post-operative patients were at risk of malnutrition or malnourished within 24 h of admission based on MNA®-SF scores, respectively.

In this research malnourished, and at-risk patients recovered over time according to CONUT® scores. The smaller group of malnourished patients showed the greatest nutritional upturn compared to the other two CONUT® groups. Myint et al.Citation38 found that patients recovering from hip fracture surgery who received protein-rich oral nutritional supplementation together with oral calcium and vitamin D for 4 weeks showed a significant change in body mass index, shorten hospital stay, and reduced infection episodes. Wyers et al.Citation39 reported that an intensive 3-month nutritional intervention in the aged adult after hip fracture improved nutritional intake and status compared to usual care although failed to influence other parameters, such as length of hospital and rehabilitation clinic stay or subsequent fractures at 1 or 5 years, amongst other clinical outcomes. The authors suggested that effective nutritional care and interventions require a good understanding of the causes underlying undernutrition in the older patient to complement ongoing oral supplementation.

Most well-nourished patients at admission kept their status while in the hospital and during follow up according to CONUT® scores. Patients admitted to the hospital due to a bone fracture lose muscle mass quickly and are at an increased risk of osteoporosis due to a combination of missing meals or feeling anorexia with a lack of physical activity and immobility.Citation7 A multidimensional personalized approach including assessment, counseling, dietary modification, and targeted oral nutritional supplements has been encouraged by other authors.Citation40 In our study, the assessment of the nutritional status of patients was done by a multidisciplinary team during both hospital admission and outpatient follow up according to the usual practice in the orthogeriatric unit. A dietitian provided dietary counseling while nutritional supplementation was revised and adapted to individual needs after each assessment. Although improvements in the patients’ nutritional status, functionality, and other parameters of overall health cannot be attributed solely to the nutritional support given in this study, several authors have claimed that tailoring nutritional recommendations to individual needs have more chances of positively affecting health outcomes in the malnourished or at risk of malnutrition population.Citation16,Citation41,Citation42 Other studies have also shown that adequate nutritional assessment and support during hospitalization renders a significant increase in dietary energy and protein intakes, improved overall nutritional status, and higher patient satisfaction and quality of life.Citation43 Therefore, continuing nutritional support and guidance may have been key to prevent malnutrition and to maintain adequate nutritional status in this aged population as in any other chronic condition that requires close supervision.

According to the MNA®-SF scores, most patients were at risk of malnutrition at admission and remained very much the same during follow up showing certain discrepancies with CONUT® findings. Screening tools help to identify patients at risk of malnutrition who may have not yet started to lose weight and do not show low plasma albumin levels but have lower than recommended protein-calorie intakes. Citation16 In this study, both CONUT® and MNA®-SF identified older patients at risk of malnutrition as it has also been found in previous research.Citation44 However, there was no correlation between CONUT® and MNA®-SF scores. This observation is also in line with studies on hip fracture patients showing that MNA®-SF scores were not significantly correlated to the individual laboratory values, including serum albumin, cholesterol, and total lymphocyte count.Citation45 It was suggested that the MNA®-SF values would reflect a clinical process in postoperative hip fractured patients which is different from the biologic markers considered in the CONUT® score.Citation45 Also, various assessment studies concluded that CONUT®, MNA®-SF, and other screening tools may have differing sensitivity and specificity to unveil undernutrition in the aged population depending on patients’ characteristics and disease processes.Citation46,Citation47

In this study, patients’ functional status determined by the Barthel index improved over time indicating that patients gained independence to perform basic activities of daily living. Patients with better nutritional status on the MNA®-SF scale tended to have a better recovery in the Barthel index than patients with a poorer nutritional status at hospital admission. Similarly, Villafañe et al.Citation48 studied a cohort of older patients hospitalized in a general rehabilitation center and found that subjects with better functional status (Barthel index 45–100) tended to have normal nutritional status (MNA-SF 12–14), while subjects with worse functional status (Barthel Index 0–44) were more likely to be malnourished or at risk for malnutrition (MNA-SF 0–11) (χ2 = 357.956, p < 0.001). The authors also reported that both nutritional and functional status worsens with age. In our study, no correlations between Barthel index functionality and nutritional status based on CONUT® scores were found. Nonetheless, other authors suggested that higher rates of independence to perform activities of daily living co-exist with lower rates of CONUT® assessed malnutrition in the aged population.Citation49 Following the dietary recommendations, the satisfactory resolution of the bone fracture and other clinical and social improvements may have equally contributed to the functional recovery of the patients in our study.

Like functionality, cognition and health-related quality of life tended to recover as nutritional parameters returned to normal. Better nutritional status correlated with a perception of a better quality of life. However, the small number of observations prevents us from reaching conclusive results. Other authors have found that cognitive function deterioration is common among malnourished older patients.Citation50 Furthermore, several dimensions of health-related quality of life are statistically significantly associated with MNA total score in both female and male older patients,Citation51 and better health-related quality of life can be expected with better physical state, nutritional status, and self-perceived general health.Citation52

Although adherence was good overall, patients at a higher risk of malnutrition adhered better to dietary recommendations and nutritional supplements than those with better nutritional parameters according to CONUT® scores and better functionality in the Barthel index. Research on adherence to dietary recommendations and nutritional supplementation amongst hip fracture patients is scarce. It is known from other chronic and asymptomatic conditions, such as hypercholesterolemia or hypertension that adherence to the recommended treatments is poor.Citation53 Patients may tend to adhere less if they have little awareness of the relevance of following the dietary advice to maintain a healthy nutritional status. Other authors found that compliance with consuming the nutritional supplements is variable, although it is an important determinant of the effectiveness of oral nutritional interventions in preventing weight loss after hip fracture.Citation54 A significant negative correlation between the amount of supplement consumed and subsequent weight change has been reported (r = −0.36, p = 0.019).Citation54 Likewise, better adherence to the Mediterranean diet and healthy lifestyle were associated with a lower bone risk fracture in women with and without osteoporosis.Citation55 Poor adherence to nutritional supplementation may be a hurdle to draw definite results on their effectiveness in the aged population.Citation56

There are limitations to this study. First, its descriptive design, showing the clinical practice in only one hospital and without a control group prevents researchers from reaching any definite conclusions. Second, a significant loss to follow up occurred that may bias results. Thus, findings should be taken as preliminary and indicative of potential relationships between variables that ought to be tested and confirmed in studies with a more robust design. Nonetheless, being real-world research, it reveals the reality of everyday medical care. Loss to follow up may have even contributed to underestimate the true magnitude of the recovery of the nutritional status of patients and their independence to perform daily living activities after dietary and nutritional supplementation. Third, several confounding variables may have certainly influenced cause-effect analyses. Changes in nutritional status, nutritional interventions, and functional capacity cannot be fully and conclusively related. From these results, it is risky to conclude that recovery of nutritional status and functionality are derived solely from the dietary and nutritional interventions. Nonetheless, the study points out the beneficial effects of nutritional support on the nutritional and functional recovery as well as on cognition and the health-related quality of life of older patients admitted into the hospital after femur fracture. Most of the contrasting evidence comes from research conducted to assess the prognostic value of either CONUT® or MNA®-SF scores to anticipate post-surgery complications or mortality. Our study seeks to understand the evolution of the nutritional status of patients after receiving multidisciplinary care and dietary support in real clinical practice. It provides preliminary information on potential correlations between nutritional screening, functionality, cognitive, and quality of life tools. It also draws attention toward considering adherence as a driven factor of the success of nutritional interventions.

In summary, malnutrition is common among older patients with femur fracture in Spain. This real clinical practice study provides preliminary evidence on the role of dietary support and oral supplementation for restoring and maintaining a healthier nutritional and functional status in an aged population. A multidisciplinary approach to care while in an orthogeriatric unit and during outpatient follow up may be desirable. The dietitian may play an important role in adapting and ensuring that recommendations fit and respond to the changing needs of the individual patient. Further research is needed to confirm these preliminary results.

Take away points

Nutritional and functional changes may occur in elderly patients with a femur fracture admitted to an orthogeriatric unit.

The proportion of malnourished patients, and of patients at risk of malnutrition decrease from admission to discharge from hospital (12 days median length of hospital stay) with the provision of dietary support, oral nutritional supplementation, and multidisciplinary team care.

Variable proportions of malnourished patients at admission are well-nourished 45-, 100- and 180-days post-discharge.

Better nutritional status positively correlates with better functionality to independently perform activities of daily living at discharge from baseline assessment.

Continued dietary support, oral nutritional supplementation, and a multidisciplinary approach to care are important for restoring or maintaining a healthy nutritional and functional status in elderly patients with femur fracture.

Ethical approval

Ethical review and approval and patient consent were necessary for this study. Patients and carers received an information sheet informing about the name of study, objectives, sponsors, data anonymization and processing, and voluntarily participation. Patients signed a written consent form. The study was approved by the clinical research ethical committee for the Aragon region in Spain given the corresponding location of the Nuestra Señora de Gracia hospital in Zaragoza.

Author contributions

SSF, ACM, LSG, MHB, MMMA, and MLP conceived and designed the study, worked on the acquisition of data, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, reviewed drafts of the manuscript, critically reviewed, validated, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (58.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, carers, and healthcare professionals at the Orthogeriatric Unit, Nuestra Señora de Gracia Hospital, Zaragoza, Spain for their contribution to this study. We also thank Silvia Paz Ruiz, Lena Huck, and Eva Robledo at SmartWorking4U for their support in the design of study, data management, statistical analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

ACM is an employee at Danone Nutricia SL. The authors declare no further conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rapp K, Büchele G, Dreinhöfer K, Bücking B, Becker C, Benzinger P. Epidemiology of hip fractures: systematic literature review of German data and an overview of the international literature. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;52(1):10–16. doi:10.1007/s00391-018-1382-z.

- Serra J, Garrido G, Vidán M, Marañon M, Brañas F. Epidemiología de la fractura de cadera en ancianos en España. An Med Int. 2002;19:389–395.

- Pérez Durillo FT, Ruiz López MD, Bouzas PR, Martín-Lagos YA. Estado nutricional en ancianos con fractura de cadera. Nutr Hosp. 2010;25(4):676–681. doi:10.3305/nh.2010.25.4.4479.

- Díaz De Bustamante M, Alarcón T, Menéndez-Colino R, Ramírez-Martín R, Otero Á, González-Montalvo JI. Prevalence of malnutrition in a cohort of 509 patients with acute hip fracture: the importance of a comprehensive assessment. Eur J Clin Nutrition. 2018;72(1):77–81. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2017.72.

- Aldebeyan S, Nooh A, Aoude A, Weber MH, Harvey EJ. Hypoalbuminaemia—a marker of malnutrition and predictor of postoperative complications and mortality after hip fractures. Injury. 2017;48(2):436–440. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2016.12.016.

- Yagi T, Oshita Y, Okano I, et al. Controlling nutritional status score predicts postoperative complications after hip fracture surgery. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):243. doi:10.1186/s12877-020-01643-3.

- Wall BT, Dirks ML, Van Loon LJC. Skeletal muscle atrophy during short-term disuse: implications for age-related sarcopenia. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):898–906. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2013.07.003.

- Wengreen HJ, Munger RG, West NA, et al. Dietary protein intake and risk of osteoporotic hip fracture in elderly residents of Utah. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(4):537–545. doi:10.1359/JBMR.040208.

- Groenendijk I, den Boeft L, van Loon LJC, de Groot L. High versus low dietary protein intake and bone health in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019;17:1101–1112. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2019.07.005.

- Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the prot-age study group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):542–559. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.021.

- Arkley J, Dixon J, Wilson F, Charlton K, Ollivere BJ, Eardley W. Assessment of nutrition and supplementation in patients with hip fractures. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2019;10:2151459319879804. doi:10.1177/2151459319879804.

- Holmes RA. Role of dietitians in reducing malnutrition in hospital. CMAJ. 2019;191(5):E139. doi:10.1503/cmaj.71130.

- Eckert KF, Cahill LE. Malnutrition in Canadian hospitals. CMAJ. 2018;190(40):E1207. doi:10.1503/cmaj.180108.

- Reber E, Gomes F, Vasiloglou MF, Schuetz P, Stanga Z. Nutritional risk screening and assessment. JCM. 2019;8(7):1065. doi:10.3390/jcm8071065.

- Ignacio De Ulíbarri J, González-Madroño A, De Villar NGP, et al. CONUT: a tool for controlling nutritional status. First validation in a hospital population. Nutr Hosp. 2005;20(1):38–45. doi:10.3305/nutr.

- Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, et al. Overview of the MNA® – its history and challenges. J Nutr Heal Aging. 2006;10(6):456–463.

- Huang Y, Huang Y, Lu M, et al. Controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score is a predictor of post-operative outcomes in elderly gastric cancer patients undergoing curative gastrectomy: a prospective study. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:9793–9800. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S233872.

- Soysal P, Veronese N, Arik F, Kalan U, Smith L, Isik AT. Mini nutritional assessment scale-short form can be useful for frailty screening in older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:693–699. doi:10.2147/CIA.S196770.

- van Wissen J, van Stijn MFM, Doodeman HJ, Houdijk APJ. Mini nutritional assessment and mortality after hip fracture surgery in the elderly. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(9):964–968. doi:10.1007/s12603-015-0630-9.

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutrition Reviews. 1996;54(1 Pt2):S59–S65. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03793.x.

- Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, et al. Validation of the mini nutritional assessment short-form (MNA®-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(9):782–788. doi:10.1007/s12603-009-0214-7.

- Boixader LS, Formiga F, Franco J, Chivite D, Corbella X. Valor pronóstico de mortalidad del índice de control nutricional (CONUT) en pacientes ingresados por insuficiencia cardiaca aguda. Nutr Clin Diet Hosp. 2016;36(4):143–147. doi:10.12873/364soldevila.

- Kato T, Yaku H, Morimoto T, et al. Association with controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score and in-hospital mortality and infection in acute heart failure. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–10. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-60404-9.

- Aranceta Bartrina J, Arija Val V, Maíz Aldalur E, et al. Guías alimentarias para la población española (SENC, diciembre 2016); la nueva pirámide de la alimentación saludable. Nutr Hosp. 2016;33(Suppl 8):1–48. doi:10.20960/nh.827.

- Hill TR, Verlaan S, Biesheuvel E, et al. A vitamin D, calcium and leucine-enriched whey protein nutritional supplement improves measures of bone health in sarcopenic non-malnourished older adults: the PROVIDE study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2019;105(4):383–391. doi:10.1007/s00223-019-00581-6.

- Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):10–47. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024.

- Nutricia. Espesante Nutilis Clear. Vademécum Nutrición enteral oral adultos. Nutricia. https://www.nutricia.es/productos/nutilis_clear/. Published 2015. Accessed October 20, 2021.

- Cabañero-Martínez MJ, CABrero-García J, Richart-Martínez M, Muñoz-Mendoza CL. Structured review of activities of daily living measures in older people. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2008;43(5):271–283. doi:10.1016/S0211-139X(08)73569-8.

- Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(8):703–709. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(89)90065-6.

- Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, Patierno C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: a critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91(1):8–35. doi:10.1159/000521288.

- Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales K, MacKenzie C. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8.

- Martínez de la Iglesiaa J, DueñasHerrerob R, Carmen Onís Vilchesa M, Aguado Tabernéa C, Albert Colomerc C, Luque Luquec R. Adaptación y validación al castellano del cuestionario de Pfeiffer (SPMSQ) para detectar la existencia de deterioro cognitivo en personas mayores e 65 años. Med Clin. 2001;117(4):129–134. doi:10.1016/S0025-7753(01)72040-4.

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi:10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003.

- Malafarina V, Reginster JY, Cabrerizo S, et al. Nutritional status and nutritional treatment are related to outcomes and mortality in older adults with hip fracture. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):555. doi:10.3390/nu10050555.

- Bell JJ, Bauer JD, Capra S, Pulle RC. Concurrent and predictive evaluation of malnutrition diagnostic measures in hip fracture inpatients: a diagnostic accuracy study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(3):358–362. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2013.276.

- Malafarina V, Uriz-Otano F, Malafarina C, Martinez JA, Zulet MA. Effectiveness of nutritional supplementation on sarcopenia and recovery in hip fracture patients. A multi-centre randomized trial. Maturitas. 2017;101:42–50. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.04.010.

- Mazzola P, Ward L, Zazzetta S, et al. Association between preoperative malnutrition and postoperative delirium after hip fracture surgery in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(6):1222–1228. doi:10.1111/jgs.14764.

- Myint MWW, Wu J, Wong E, et al. Clinical benefits of oral nutritional supplementation for elderly hip fracture patients: a single blind randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2013;42(1):39–45. doi:10.1093/ageing/afs078.

- Wyers CE, Reijven PLM, Breedveld-Peters JJL, et al. Efficacy of nutritional intervention in elderly after hip fracture: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(10):1429–1437. doi:10.1093/gerona/gly030.

- Bender DV, Krznarić Ž. Nutritional issues and considerations in the elderly: an update. Croat Med J. 2020;61(2):180–183. doi:10.3325/cmj.2020.61.180.

- Ordovas JM, Ferguson LR, Tai ES, Mathers JC. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018;361:bmj.k2173. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2173.

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Nutritional assessment in older adults: MNA® 25 years of a screening tool & a reference standard for care and research; what next? J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(4):528–583. doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1601-y.

- Yinusa G, Scammell J, Murphy J, Ford G, Baron S. Multidisciplinary provision of food and nutritional care to hospitalized adult in-patients: a scoping review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:459–491. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S255256.

- Revilla P, García P, Francisco J, Samaniego G, Pilar M. Utilidad del CONUT frente al MNA en la valoración del estado nutricional del paciente adulto mayor hospitalizado. Horiz Med. 2013;13(3):40–46.

- Formiga F, Chivite D, Mascaró J, Ramón JM, Pujol R. No correlation between mini-nutritional assessment (short form) scale and clinical outcomes in 73 elderly patients admitted for hip fracture. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17(4):343–346. doi:10.1007/BF03324620.

- Power L, Mullally D, Gibney ER, et al. A review of the validity of malnutrition screening tools used in older adults in community and healthcare settings – a MaNuEL study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;24:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.02.005.

- Baek MH, Heo YR. Evaluation of the efficacy of nutritional screening tools to predict malnutrition in the elderly at a geriatric care hospital. Nutr Res Pract. 2015;9(6):637–643. doi:10.4162/nrp.2015.9.6.637.

- Villafañe JH, Pirali C, Dughi S, et al. Association between malnutrition and Barthel index in a cohort of hospitalized older adults article information. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(2):607–612. doi:10.1589/jpts.28.607.

- Lardiés SB, Sanz PA, Pérez NJ, Serrano OA, Torres Anoro ME, Ballesteros Pomar MD. Discapacidad y su influencia en las herramientas de valoración nutricional en ancianos institucionalizados en residencias geriátricas. Nutr Hosp. 2017;34(5):1080–1088. doi:10.20960/nh.1061.

- El Zoghbi M, Boulos C, Amal AH, et al. Association between cognitive function and nutritional status in elderly: a cross-sectional study in three institutions of Beirut-Lebanon. Geriatr Ment Heal Care. 2013;1(4):73–81. doi:10.1016/j.gmhc.2013.04.007.

- Salminen KS, Suominen MH, Soini H, et al. Associations between nutritional status and health-related quality of life among long-term care residents in Helsinki. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(5):474–478. doi:10.1007/s12603-019-1182-1.

- de Oliveira LFS, Wanderley RL, de Medeiros MMD, et al. Health-related quality of life of institutionalized older adults: influence of physical, nutritional and self-perceived health status. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;92:104278. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2020.104278.

- World Health Organization. Adherence to Long Term Therapies: Evidence for Action, Eduardo Sabaté, ed.; 2003. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf. Updated 2020. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- Bruce D, Laurance I, Mcguiness M, Ridley M, Goldswain P. Nutritional supplements after hip fracture: poor compliance limits effectiveness. Clin Nutr. 2003;22(5):497–500. doi:10.1016/S0261-5614(03)00050-5.

- Palomeras-Vilches A, Viñals-Mayolas E, Bou-Mias C, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and bone fracture risk in middle-aged women: a case control study. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2508. doi:10.3390/nu11102508.

- Cameron ID, Kurrle SE, Uy C, Lockwood KA, Au L, Schaafsma FG. Effectiveness of oral nutritional supplementation for older women after a fracture: rationale. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:32. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-11-32