Abstract

Congregate Nutrition Services have long been a pillar of public health assistance, championing the independence and community engagement of older Americans. The advent of COVID-19, however, restricted access to these services due to the closure of physical locations. In response, Lanakila Meals on Wheels initiated a virtual congregate meal program, Kūpuna U, in collaboration with community partners in Honolulu County. The program combined grab-and-go or home-delivered meals with virtual and in-person classes to improve both nutrition and socialization for older adults. This study aimed to capture participant feedback to assess and enhance the Kūpuna U program, developing it as a flexible and scalable congregate meal solution applicable nationwide. Five focus group discussions were conducted with program participants (n = 34). The majority of participants were female (74%), Asian (73%), and living alone (56%). Participants found the program beneficial, enhancing their nutrition, social engagement, and learning experiences on various topics tailored for older adults. Supportive staff played a crucial role in motivating participants to stay engaged. Participants also identified potential enhancements to the program, including more activities and courses, expanded hours, additional in-person options at various locations, and culturally tailored meals.

Introduction

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines food insecurity as the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways.Citation1 Food insecurity negatively impacts both the physical and mental health of older adults, raising the risk of developing chronic medical diseases, impairing the immune system, and lowering general quality of life.Citation2–4 The prevalence of food insecurity among older individuals has increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation5 During the pandemic, older adults were considered the most vulnerable segment of the population due to their susceptibility and high prevalence of chronic conditions.Citation6 Due to the high health risk, older adults required isolation, and their access to daily meals was profoundly impacted by the closing of congregate meal sites, reduced access to grocery stores, and the lack of volunteers available to deliver meals. The State of Senior Hunger in America research indicates that in 2021, out of 78 million people aged 60 and over, 5.5 Million (7.1%) experienced food insecurity.Citation7 Additionally, given the rapid growth in the older adult population, the number of food-insecure older Americans is projected to increase significantly by 2030.Citation8

To address the challenges associated with food insecurity, the Congregate Nutrition Services (CNS) program, operating within the framework of the Older Americans Act (OAA), has long been a cornerstone of public food assistance services aimed at promoting social engagement, health, and wellness among older Americans.Citation9,Citation10 This program plays a pivotal role in ensuring food security for its targeted population, enjoying a well-deserved reputation and esteem among older adults. On average, it provides participants with a substantial portion of their daily caloric intake (41%), along with 46% of the necessary protein and 43% of essential vitamins and minerals.Citation11 Additionally, there is compelling evidence suggesting that the program serves as a preventive measure, helping to reduce hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and prolonged stays in long-term care facilities.Citation12 During COVID-19, shutdowns and stay-at-home orders were essential to keep the community safe from the spread of the virus. However, these same measures increased food insecurity, social isolation, and loneliness among older adults.Citation3,Citation13 The Administration for Community Living (ACL) recommended the need to be innovative to tackle the unmet needs and challenges the senior community faces. ACL's recommendation was to develop hybrid (mix of in-person and virtual) programs.Citation14

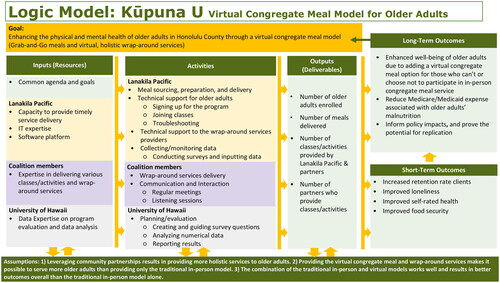

In response, Lanakila Meals on Wheels launched the Kūpuna U program, a virtual congregate meal program aimed at enhancing food security, fostering social connectedness, and promoting overall wellness among older adults in Honolulu County (program logic model shown in ). This innovative program provides essential nutrition and educational activities while prioritizing the safety of participants. The ability to reallocate budgets between the CNS (OAA Section 331, sometimes called C1) and Home-Delivered Nutrition Services (OAA Section 336, sometimes called C2)Citation15 provided the Kūpuna U program with the flexibility to offer tailored support during challenging times. Kūpuna U offers meal options through grab-and-go or home delivery, along with access to activities and classes through an online platform (in addition to in-person digital literacy classes). Notably, this program distinguishes itself by leveraging community partnerships, particularly the Kūpuna Food Security Coalition, which unites over 40 diverse partners to address food insecurity among older adults in Hawai’i. Through this collaborative effort, Kūpuna U offers a wide range of content aimed at promoting socialization, health, and overall well-being among older adults via the online platform ().

The Administration for Community Living (ACL) has funded “Innovations in Nutrition” (INNU) grants to support testing and documenting innovative and promising practices in state nutrition programs.Citation16 Authorized by the OAA, the program aims to enhance the quality, effectiveness, and outcomes of senior nutrition programs and services. The Kūpuna U program was awarded one of these grants given their previously demonstrated value during the COVID-19 pandemic and that the program has the potential for broad implementation throughout the aging services network.Citation17

Numerous studies associated with the COVID-19 pandemic examined the magnitude of older adults’ unmet needs due to insufficient access to food and related services.Citation18–21 They recommended future research on incorporating social support systems and increasing technology access and literacy among older adults to combat the situation arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. The primary aim of this study is to gather participant feedback for use in refining the Kūpuna U program as a flexible and scalable model for the expansion of congregate meal services that can be implemented across the United States, increasing reach and improving both nutrition and socialization.

Methods

In this study, focus group discussions were utilized as a qualitative research method. The choice to use focus group discussions is grounded in their effectiveness, particularly when gathering insights and perspectives from older adults. Focus group discussions enable the collection of a significant amount of relevant data within a limited timeframe.Citation22 Additionally, focus group discussions yield a richer array of responses compared to individual interviews due to the dynamic interaction among participants in the group.Citation23 Engaging with the diverse experiences of others promotes spontaneous and unscripted responses, thereby enriching the depth of insights gained. Although the data was initially collected for program evaluation purposes required by the funder, the Administration for Community Living, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was subsequently obtained for the publication of this manuscript.

Participants

The Kūpuna U program was comprised of three distinct cohorts of older adults: a cohort residing in an affordable senior housing building who collectively participated in online classes within the community room of their building, a cohort attending in-person digital literacy classes at a local senior center, and a cohort that exclusively engaged in online classes from their individual residences. All three cohorts were provided with either grab-and-go meals or home-delivered meals.

Collaborating closely with Lanakila Meals on Wheels staff, the research team from the University of Hawai’i Center on Aging successfully enlisted 34 focus group participants across the three distinct cohorts. These cohorts encompassed a senior housing group (n = 8), an in-person digital literacy class group (n = 17), and an online group (n = 9).

To enhance the depth of discussion, five distinct focus groups took place at three different venues: at the senior housing site for the senior housing group, at the senior center where the digital literacy class was held for the in-person group, and virtually via Zoom for the online group, all situated within Honolulu County where the service was provided. Further partitioning arose from the subdivision of the in-person digital literacy class and the online groups into four smaller subgroups (two per cohort). This tactical approach promoted more intimate and engaged conversations within each subgroup.

Procedure

The participants were recruited by the Lanakila Meals on Wheels staff among older adults who were participating in the Kūpuna U program. The staff announced the sessions with the title of “Talk Story Session” to make the sessions feel more casual and approachable for older adults.

Three researchers fulfilled the role of moderators across the five focus groups. Their specific roles were as follows: one researcher moderated a senior housing group (n = 8, referred to as G1), an in-person digital literacy class group (n = 9, referred to as G2), as well as an online group (n = 5, referred to as G4), the second researcher facilitated an in-person digital literacy class group (n = 8, referred to as G3), and the third researcher led an online group (n = 4, referred to as G5). The first and second researchers are two of the authors of this study.

These five focus group discussions each lasted ∼1 h and were conducted during the second and third weeks of May 2023. Before commencing the focus group sessions, the moderators ensured that participants were briefed on the study’s objectives. In addition, participants were provided with written informed consent forms and were asked to complete a concise demographic questionnaire. To uphold participant confidentiality, the responses were meticulously kept separate from the participants’ identities.

Out of the five groups, four (G1, 2, 4, and 5) were audio recorded and the ensuing audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. To guarantee accuracy, a dedicated member of the research team cross-referenced these transcripts against the original audio recordings. One of the in-person digital literacy class groups (G3) was not recorded due to concerns voiced by two of the participants who felt uncomfortable having their voices recorded, even though they actively participated in the discussions. As a result, the research team relied heavily on their comprehensive notes from this session to facilitate subsequent data analysis.

Data analysis

The analytical methodology chosen for this study was an inductive analysis to identify themes within larger categories.Citation24 The research employed four predefined categoriesCitation25 linked to the four questions for participants posed:

What factors do the participants identify as positives of the meal program?

What factors do the participants identify as opportunities for the meal program?

What factors do the participants identify as positives of the activity courses?

What factors do the participants identify as opportunities for the activity courses?

These established categories served as the framework for coding the data extracted from the focus group discussions. Subsequently, the researchers leveraged inductive analysis to identify themes that emerged organically during the analysis process. This approach served two main objectives: respecting the viewpoints of the participants and aiding in analysis that is informed by theoretical frameworks. The widespread acceptance of this methodology is attributed to its inherent worth and its capacity for broader applicability.Citation26

Two coders systematically examined the transcripts using NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software. Initially, they scrutinized all the transcripts and accompanying notes. Once a shared understanding of the codes was achieved through thorough deliberation of each code, a general consensus was established.Citation27

Results

The analysis of the focus group transcripts highlighted what worked well about participating in the Kūpuna U program and where they saw areas for improvement. These topics corresponded closely with the four categories initially anticipated, encompassing what they appreciated about the meal program and their preferences for enhancing it, as well as identifying areas for refinement in the activity courses. Participants were primarily Asian females, 75 years and older, and living alone ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of focus group participants.

Positives of the activities courses

Positives of attending activity courses as a part of the program were the items most frequently mentioned (). The key themes included learning new skills and knowledge from teachers who cater to my level, having a very supportive staff, and the diversity of course topics with a convenient schedule. Participants also mentioned the benefits of promoting social interaction with others and the fact that there is no cost to attend.

Table 2. Key themes from focus group sessions (listed by frequency of mention).

Key theme: Learning anew with content suitable for older adults

Participants were enthusiastic to learn something new, such as how to improve their health and skills in using smartphones and computers. Participants shared that before this program it was difficult for them to find places that provided the classes that they desired. Even more challenging was finding places that taught age-appropriate content. For example, more than half of the participants in the in-person class groups shared that they had previously experienced feelings of embarrassment and frustration when learning to use smartphones and computers from family members or staff from digital device commercial stores (such as Apple and Verizon) since the participants struggled to understand due to fast explanations and use of technical terms that they didn’t understand. However, Kūpuna U consolidates all the classes into a single platform, and the instructors tailor the content to suit older adults. These instructors are adept at explaining concepts at the participants’ comprehension levels, utilizing straightforward language, speaking slowly, and providing repetitive explanations as needed.

Key theme: Having very supportive staff

Participants’ appreciation of supportive staff emerged as a significant motivator for sustained engagement in activities/classes. Specifically, for participants in the in-person digital literacy class, using electronic devices was very challenging. However, the staff’s patience and professionalism in addressing repeated inquiries and welcoming any questions fostered a conducive learning environment. Moreover, the sign-up procedure was highlighted as remarkably easy due to the staff’s assistance in completing the enrollment form.

G2, P2: “They’re just good, […] we’re at that age that we don’t always hear. […] we hear it, and we forget. Then the next week, somebody else is going to be asked the same question, and the instructor will go over again (without any complaints).”

G2, P4: “I think it’s perfect for our age. I'm very thankful.”

Key theme: A diverse range of course topics with flexible class timing

Participants expressed that having diverse content caused them to participate in the activities/classes since they had more options that they could choose from consistent with their schedule and their interests.

G4, P5: “I do see various topics that are very interesting. You know, sometimes it’s not suited[…], like I might have some other things […] like a (doctor’s) appointment, or some other.”

G4, P3: “I like the variety that we have, like with Ms. Lara and the nutritionist, other tech support, and the virtual visits (tours).”

Additional theme: Promoted socialization with others

Participants agreed that engaging in activities and classes offered them the opportunity to meet and socialize with fellow participants.

G5, P2: “We see these familiar faces, and it’s like the program feels much more lively.”

G2, P3: “We meet new people through this class.”

G2, P6: “We are all friends and like seeing each other each week.”

Opportunities to improve the activities courses

Opportunities to improve the activity courses as a part of the program accounted received about half of the total number of mentions that the positives received. The key themes that emerged as opportunities to improve the activities/courses were the need for more content with expanded class hours and enhanced online class facilitators’ skills ().

Key theme: More content with expanded class hours

Some participants shared that they saw classes that they were interested in on the list, but they said the times were not convenient for them. Additionally, some in-person classes are overcrowded due to the limited space to accommodate a large number of participants, and the class durations are deemed excessively lengthy. Participants have voiced their wish for Kūpuna U to expand its offerings by providing a broader selection and increased quantity of classes that can better address the diverse requirements of various groups.

G2, P5: “I usually don’t have the time, because at that time, I was volunteering at my grandson’s Elementary School at Milani Elementary. And so I was there most of the time.”

Online class facilitators’ skills in using online tools

Participants who were a part of the online group noted that some of the instructors for online classes needed to improve their virtual instructional skills:

G4, P1: “They need to monitor the class to make sure that participants mute while others are speaking or during the class session.”

G4, P3: “Some people accidentally unmute themselves […] we could hear background noises or conversations that interrupt the class.”

Positives of the meal program

Positives regarding the meal program were the least frequently coded mentions (17%, ). The key themes that emerged from the focus group participants were that the meal program helped promote healthier eating habits due to consuming more nutritious food with less worry about money, which resulted in them eating meals regularly, along with the financial benefit of the program.

Key theme: Improved nutrition

Participants received meals through either grab-and-go meals provided at the senior center and senior housing building, or through home-delivered meal programs. Their feedback indicates that these meal options have positively impacted their dietary choices. Furthermore, participants expressed their gratitude for the meal program, highlighting its capacity to facilitate the consumption of nutritionally rich meals, notably featuring vegetables and fruits. Additionally, participants shared that they liked the quality of meals.

G2, P4: “I appreciate you know, especially the fruits you know because sometimes when I go (to the market), it is so expensive!”

G2, P6: “I don’t like to cook, so I appreciate the meals. And if I didn’t have the meals (program), I'd probably be eating (unhealthy food while watching) TV and snacking a lot.”

G2, P5: “It was a surprise when I received the meal, and I didn’t know that. […] We started eating that, and I thought well these are good ingredients I can tell.”

Key theme: Financial relief

Participants were unanimous in their belief that the meals program significantly contributes to saving expenses, thereby alleviating their stress levels. This was primarily attributed to their reduced concern about the financial burden associated with purchasing meals or acquiring ingredients.

G2 P4: “We do it (receive the meals) in a sense struggle because we have other things that cost a lot, maybe medications or other things. And so having something like this (participating in the meal program), that’s impressive.”

Opportunities to improve the meal program

Opportunities to improve the meal program were mentioned more often than the positives. Key themes that emerged from the focus groups were that the meal program did not include their preferred or culturally appropriate items, that the quality of the meals was not good, and that the meals were unneeded ().

Key theme: Not preferred types of food

Participants shared that they wished that they could have more culturally appropriate food. One participant was a Korean American and he would prefer to have kimchi and Korean side dishes. Another participant, who was a Native Hawai’ian, wished to have more local and Hawai’ian food in the meal. Others shared that they would prefer more vegetarian dishes.

G4, P1: “I wish there were more vegetarian dishes. And you know, the fish and stuff is okay. So, yeah. I like I like vegetables. And the brown rice is good too. Oh, and I appreciate the fresh fruits, like the bananas and the oranges.”

Key theme: Quality of meals is not good

Several participants voiced concerns about the quality of the meals provided. Some mentioned that they find certain dishes to be overly seasoned, either too salty or too mild for their taste. Additionally, one participant expressed their dissatisfaction with the meals, citing issues with the texture of certain vegetables that were difficult to chew. Furthermore, several participants commented on the meals containing excessive amounts of fat and starch.

Key theme: Meal support is not needed

This feedback primarily originated from the two in-person digital literacy class groups who enrolled in the program to acquire digital device skills. These participants expressed that they did not need meal support, as the majority of these groups felt confident in their ability to prepare meals independently. Importantly, the consensus among these participants was that meal support should be directed toward those in greater need, with ∼90% of individuals in these two groups indicating that they did not require such assistance.

G2, P3: “(the meal provider) should give (the meal support) to those needy people. […] I can afford to buy things, but (providing meals to those who are less needed) is just like an excessive thing to pay (for the meal provider) to get the funding.”

Discussion

This study explored the positives and opportunities associated with the Kūpuna U program by collecting feedback from participants. This program served as an alternative to the traditional Congregate Nutrition Service program, providing older adults with the necessary nutrition and socialization activities/education while ensuring their safety during COVID-19. In conjunction with grab-and-go or home-delivered meals, the Kūpuna U program effectively provided older adults with a diverse range of both virtual and in-person courses through collaborative partnerships with community service providers hosted on an integrated platform. These offerings were tailored to cater to the preferences of vulnerable individuals, aiming to enhance socialization opportunities and nutritional intake for older adults, even when in-person gatherings were restricted.

The activity courses were well-received by older participants, who identified four key design elements that ensured that the courses met their needs. First, participants expressed a strong desire for learning opportunities related to health and technology, aligning with previous studies.Citation28,Citation29 Feedback from the focus groups highlighted that this program effectively delivered content that was tailored to suit their specific needs and interests as older adults. Second, participants emphasized the importance of supportive and empathetic staff in these classes, echoing findings from studies on teaching digital technologies to older adults.Citation30 Third, the participants, particularly in online groups, valued diverse classes and flexible schedules, enabling them to choose courses based on their skill level and availability. Similarly, Chiu et al. also emphasized the advantages of this flexible approach in enhancing learning opportunities among older adults.Citation31 Lastly, promoting socialization with fellow participants was deemed crucial, as it fostered a sense of community and connection, significantly enhancing their program enjoyment, aligning with findings by Mabli et al.Citation12

Kūpuna U was able to deliver a more diverse set of activities and courses compared to the traditional model, thanks to its collaborative partnerships with community organizations providing a wide range of content. Currently, these offerings are provided at no cost due to the generosity of the program’s partners. To ensure the sustainability of this program, it is essential to explore avenues for reimbursing the community partners who contribute content to the program’s online platform. This not only acknowledges their valuable contributions but also fosters lasting partnerships that can continue to benefit older adults in need.

As a part of the research, further insights into potential enhancements for the Kūpuna U program’s courses were identified, primarily revolving around the incorporation of additional content and extended class hours, particularly within the in-person groups. The demographics of the participants were very diverse, encompassing varying age groups and ethnic backgrounds, consequently leading to a wide spectrum of interests, ranging from leisure activities like bingo to more practical topics, such as financial management. Additionally, participants frequently contended with busy schedules, often compounded by caregiving responsibilities for ailing spouses or grandchildren. This complex juggling act frequently forced them to forgo participation in certain activities or courses due to scheduling conflicts. Furthermore, in the context of in-person digital classes, some participants noted issues related to overcrowding, largely attributable to the program’s popularity. Unfortunately, there were limited alternative options available for these individuals. Considering these issues, participants expressed a strong desire for an increased number of classes, which would help alleviate class overcrowding and provide more scheduling flexibility.

Many participants also appreciated the inclusion of meal services in the program, similar to findings from studies on food bank seniors in the Feeding America network.Citation32 These meals enabled them to incorporate better nutrition into their diets by including more fruits and vegetables, items that can often be costly to purchase independently. Furthermore, having access to these meals meant they were less likely to skip meals, even when unable to cook due to physical health issues. This finding aligns with findings from Mabli et al., assessing the effectiveness of the Nutrition Services Program for both congregate and home-delivered meal participants.Citation12 Another notable benefit of the meal service was the reduction of financial stress, as it relieved participants of concerns about purchasing food. Numerous studies have identified affordability as a significant source of stress among older adults, imposing constraints on their food budget.Citation3,Citation32 Although a subset of participants is able to prepare their own meals and prefers to do so, they report an inability to opt out of the provided meal support due to the program’s requirements.

Participants also offered suggestions for enhancing the meal component of the program. These recommendations include diversifying the menu to encompass culturally tailored options like Hawai’ian and Korean cuisine, as well as incorporating more vegetarian dishes. This preference for culturally tailored cuisine aligns with prior research,Citation33,Citation34 and mirrors the National Council on Aging’s recommendation to include diverse cultural dishes to cater to participants from various ethnic backgrounds.Citation35 Furthermore, some participants pointed out that improvements are needed in terms of food quality, as taste-related issues like excessive saltiness or blandness, as well as texture concerns, such as difficult-to-chew vegetables or undercooked items, were noted. While other studies have also suggested improving meal quality for congregate meal services, including reducing salt intake,Citation36 others have reported improved health outcomes associated with the existing program.Citation12 This concern might be related to an individual’s eating habits and preferences. Lastly, a subset of participants expressed that they do not require meal support, as they are capable of preparing their own food and prefer doing so. However, they have indicated that they lack the option to decline the provided meals, as program participation mandates their acceptance.

In analyzing the demographics of the Kūpuna U program, the increased flexibility of the program structure resulted in reaching additional segments of older adults. The combination of the home-delivered meals option with online courses tended to reach older participants, with 75% of these participants being 75 years or older and 65% of these participants living alone. Researchers also noted that they tended to be frailer based on their observations of the participants’ physical conditions when the discussion was held. These findings align with the intentions of the Home-Delivered Meals (C2) program, which primarily serves frail, homebound, or isolated individuals aged 60 and over, and in some instances, their caregivers, and individuals with disabilities.Citation16 In contrast, the participants in the in-person digital literacy class with the grab-and-go meals option group were relatively younger, with only 54% of participants 75 years or older, with fewer mobility issues.

Post-pandemic, the reinstated separation of C1 and C2 funding limits the program’s ability to provide a more comprehensive range of activity classes and nutrition services to a wider group of older adults in need, thereby limiting the improvement possible in the nutrition and socialization of older individuals. This separation of funding also hinders the successful achievement of OAA Nutrition Services Program goals. For example, more than half of the Kūpuna U participants who chose home-delivered meals combined with online courses wouldn’t have been able to join the nutrition program before COVID since they would not be able to attend the physical congregate meal sites (C1) due to either minor mobility limitations or lack of transportation, but they would not meet the criteria to qualify for the Home-Delivered Meals (C2) program. The flexibility of the Kūpuna U program increased participation in courses and improved social interactions while still benefiting from the food provided through grab-and-go and home-delivered meals—resulting in improved nutrition and reduced social isolation. Given these benefits, it is recommended to introduce a degree of flexibility between C1 and C2 to ensure that more older adults can access ACL Nutrition services effectively.

The limitations of this study are that it relied on focus group interactions with participants to identify the positive aspects of the Kūpuna U program, as well as the opportunities for improvement to the program. The relatively small sample size and qualitative assessment associated with these focus groups limited the ability to quantify the positive impacts on nutrition and social isolation beyond the statements and discussion among the participants. Additionally, since older adults self-selected how they chose to participate in the Kūpuna U program (how meals were provided and what courses and activities they engaged with), the comparison between groups was not possible given potential self-selection bias. Further, there was no control group of individual participants participating in traditional congregate meal programs for comparison purposes. While the program was well received by participants, additional study is required to identify the relative benefit of the Kūpuna U program on improving both nutrition and social isolation for older adults.

Conclusion

Kūpuna U program, a virtual congregate meal program, stands as a model of innovation and adaptability in addressing the evolving needs of older adults. By incorporating participant feedback and addressing identified opportunities for improvement, it has the potential to continue making a meaningful difference in the lives of older individuals, enhancing their overall well-being and quality of life.

Take away points

Kūpuna U is a virtual congregate meal program that successfully provides older adults with meals and activities/courses to improve nutrition and socialization.

Participants found the program beneficial, enhancing their nutrition, social engagement, and learning experiences on various topics tailored for older adults.

Supportive staff played a crucial role in motivating participants to stay engaged.

Participants identified potential enhancements to the program, including more activities and courses, expanded hours, additional in-person options at various locations, and culturally tailored meals.

Authors contributions

Lee and Nishita designed and facilitated the focus group discussions. Lee and Sultana analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the paper. Nishita revised and approved the final version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Lanakila Meals on Wheels staff, including James Li, Naithan Alva, and Gabrielle Solomita, for their invaluable assistance in participant recruitment and additional support. Appreciation is also extended to Sharie Nagatani for her efforts in coordinating and facilitating the discussions. Finally, heartfelt thanks are extended to all the participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- USDA. Food security in the U.S. measurement. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/measurement/. Accessed April 25, 2024.

- Food Research and Action Center (FRAC). Hunger is a health issue for older adults: food security, health, and the federal nutrition programs. https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/hunger-is-a-health-issue-for-older-adults-1.pdf. Published 2019.

- Howe-Burris M, Giroux S, Waldman K, et al. The interactions of food security, health, and loneliness among rural older adults before and after the onset of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2022;14(23):5076. doi:10.3390/nu14235076.

- Lee JY, Shen S, Nishita C. Development of older adult food insecurity index to assess food insecurity of older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2022;26(7):739–746. doi:10.1007/s12603-022-1816-6.

- Niles MT, Bertmann F, Belarmino EH, Wentworth T, Biehl E, Neff R. The early food insecurity impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2096. doi:10.3390/nu12072096.

- Choi SL, Men F. Food insecurity associated with higher COVID-19 infection in households with older adults. Public Health. 2021;200:7–14. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.09.002.

- Ziliak JP, Gundersen C. The State of Senior Hunger in America in 2021: An Annual Report. Feeding America; 2023. https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/State%20of%20Senior%20Hunger%20in%202021.pdf.

- Vespa J, Medina L, Armstrong DM. Population estimates and projections. United States Census Bureau; 2020. https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/documents/census_population_projections_2020_2060.pdf

- Gergerich E, Shobe M, Christy K. Sustaining our nation’s seniors through federal food and nutrition programs. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;34(3):273–291. doi:10.1080/21551197.2015.1054572.

- Administration for Community Living. Older Americans Act nutrition programs. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/news%202017-03/OAA-Nutrition_Programs_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Published 2023.

- Mabli J, Gearan E, Cohen R, et al. Evaluation of the effect of the Older Americans Act Title III-C nutrition services program on participants’ food security, socialization, and diet quality. Published 2017.

- Mabli J, Ghosh A, Schmitz B, et al. Evaluation of the effect of the Older Americans Act Title III-C nutrition services program on participants’ health care utilization. Published 2017.

- Jackson AM, Weaver RH, Iniguez A, Lanigan J. A lifespan perspective of structural and perceived social relationships, food insecurity, and dietary behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appetite. 2022;168:105717. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2021.105717.

- ACL A for CL. COVID-19 response: reopening considerations for senior nutrition programs. Published 2021.

- Administration for Community Living. AoA – unwinding PHE and MDD for COVID-19.pdf. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/2023-03/AoA%20-%20Unwinding%20PHE%20and%20MDD%20for%20COVID-19.pdf. Published 2023. Accessed August 10, 2023.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living. Nutrition Services_ACL. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living. http://acl.gov/programs/health-wellness/nutrition-services. Published 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023.

- ACL. ACL Awards INNU Cooperative Agreements | ACL Administration for Community Living. http://acl.gov/news-and-events/announcements/acl-awards-innu-cooperative-agreements. Accessed September 21, 2023.

- Capicio M, Panesar S, Keller H, et al. Nutrition risk, resilience and effects of a brief education intervention among community-dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta, Canada. Nutrients. 2022;14(5):1110. doi:10.3390/nu14051110.

- Munger AL, Speirs KE, Grutzmacher SK, Edwards M. Social service providers’ perceptions of older adults’ food access during COVID-19. J Aging Soc Policy. 2023:1–18. doi:10.1080/08959420.2023.2205770.

- Nicklett EJ, Johnson KE, Troy LM, Vartak M, Reiter A. Food access, diet quality, and nutritional status of older adults during COVID-19: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:763994. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.763994.

- Perry L, Scheerens C, Greene M, et al. Unmet health-related needs of community-dwelling older adults during COVID-19 lockdown in a diverse urban cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):178–187. doi:10.1111/jgs.18098.

- Rabiee F. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63(4):655–660. doi:10.1079/PNS2004399.

- Acocella I. The focus groups in social research: advantages and disadvantages. Qual Quant. 2012;46(4):1125–1136. doi:10.1007/s11135-011-9600-4.

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. doi:10.1177/160940690600500107.

- Vanover C, Mihas P, Saldana J. Analyzing and Interpreting Qualitative Research: After the Interview. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2021.

- Proudfoot K. Inductive/deductive hybrid thematic analysis in mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res. 2023;17(3):308–326. doi:10.1177/15586898221126816.

- Feng GC. Intercoder reliability indices: disuse, misuse, and abuse. Qual Quant. 2014;48(3):1803–1815. doi:10.1007/s11135-013-9956-8.

- Kakulla B. Lifelong Learning among 45+ Adults. Washington (DC): AARP Research; 2022. doi:10.26419/res.00526.001.

- Mitzner TL, Fausset CB, Boron JB, et al. Older adults’ training preferences for learning to use technology. Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meet. 2008;52(26):2047–2051. doi:10.1177/154193120805202603.

- Ahmad NA, Abd Rauf MF, Mohd Zaid NN, Zainal A, Tengku Shahdan TS, Abdul Razak FH. Effectiveness of instructional strategies designed for older adults in learning digital technologies: a systematic literature review. SN Comput Sci. 2022;3(2):130. doi:10.1007/s42979-022-01016-0.

- Chiu CJ, Tasi WC, Yang WL, Guo JL. How to help older adults learn new technology? Results from a multiple case research interviewing the internet technology instructors at the senior learning center. Comput Educ. 2019;129:61–70. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2018.10.020.

- Warren AM, Frongillo EA, Alford S, McDonald E. Taxonomy of seniors’ needs for food and food assistance in the United States. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(7):988–1003. doi:10.1177/1049732320906143.

- Frongillo EA, Isaacman TD, Horan CM, Wethington E, Pillemer K. Adequacy of and satisfaction with delivery and use of home-delivered meals. J Nutr Elder. 2010;29(2):211–226. doi:10.1080/01639361003772525.

- Song HJ, Simon JR, Patel DU. Food preferences of older adults in senior nutrition programs. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;33(1):55–67. doi:10.1080/21551197.2013.875502.

- Wilson-Gold K. How to strengthen congregate meal programs for seniors. https://www.ncoa.org/article/how-to-power-up-your-congregate-meal-program-for-older-adults. Accessed April 25, 2024.

- Seo S, Kim OY, Ahn J. Healthy eating exploratory program for the elderly: low salt intake in congregate meal service. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(3):316–324. doi:10.1007/s12603-015-0622-9.