ABSTRACT

This study investigates the role that the analysis of accounting books can assume for the functioning of an industry self-regulatory institution. If industry self-regulatory institutions have been extensively studied, scholars have neglected the role that accounting can have in their functioning, as well as an imitation mechanism. This research is focused on the ‘Unione Commercianti in Manifatture di Milano’, created in 1898. The Union contributed towards preserving fair and honest trade in the textiles industry, and to protecting the credit rights of members involved in the bankruptcy proceedings of their customers. Between 1898 and 1902, the Union examined the accounting books of more than 1700 proceedings. According to institutional theory, for each organisation the analysis of accounting books represents a mechanism for arbitrating, a tool to evaluate whether or not to try to recover credit rights. Considering the difficulty for organisations to arbitrate, the need to acquire and analyse the financial information of customers involved in bankruptcy proceedings represented a key factor for the creation of the Union. Its ability to evaluate bankruptcy proceedings through the investigation of accounting books – conducting ‘accounting and legal autopsies’ in many proceedings – generated imitation mechanisms that pushed new members to join the institution.

Introduction

In the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the Italian Kingdom experienced the first important post-unification economic downturn (Corbino Citation1962; Clough Citation1965; Confalonieri Citation1974). As a consequence, during the decades 1881–1900 business bankruptcies increased significantly and, at the same time, a crisis of entrepreneurial morality and honesty spread. In many cases, using any expedient and the abuse of credit, bankrupts continued businesses, leaving little or nothing to creditors (Federici Citation1899). The misinterpretation and inadequate application of bankruptcy law, as well as the mismanagement of insolvency proceedings, by many Italian Courts accentuated the spread of business malpractice (Penserini Citation1904). More generally, unlike other European countries, in the nascent Kingdom of Italy bankruptcy law and related practices were significantly less efficient in protecting creditors’ rights (Hautcœur and Di Martino Citation2013), negatively affecting the development of the economy.

To protect and self-regulate the textiles industry, the ‘Unione Commercianti in Manifatture di Milano’ (Union of Textile Manufacturers and Traders of Milan) was created in 1898. The Union contributed towards preserving fair and honest trade in the textiles industry, and to protecting the credit rights of members involved in the bankruptcy proceedings of their customers. To this end, between 1898 and 1902, the Union examined the accounting books and administrative documents – filed in the Italian Courts – of more than 1700 proceedings, jointly exercising members’ voting rights in bankruptcy arrangements and promoting unitary legal actions.

Given the preceding, this study analyses the role that accounting can assume for the creation and the functioning of an industry self-regulatory institution. Many studies have shown that the interest in solving a common problem can induce organisations to create industry self-regulatory institutions (Ostrom Citation1990; Barnett and King Citation2008; Yue and Ingram Citation2012). These institutions, aimed at countering a threat, tend to promote more efficient social and economic exchanges (Williamson Citation1985; North Citation1990). According to institutional isomorphic change theory (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983), to make members’ behaviour uniform, an industry self-regulatory institution can operate successfully through coercive, normative or mimetic forces (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1991; Scott Citation1995; Nash and Ehrenfeld Citation1997).

Hence, this research adheres to the functional theory that the purpose of self-regulatory institutions is in solving common problems (Barnett and King Citation2008; Balleisen Citation2009). If an industry self-regulatory institution can assure direct, measurable, and tangible advantages for each single member, which are not individually replicable, participants will make their actions and behaviour uniform to obtain them through imitation mechanisms and, in particular, social learning (Kraatz Citation1998). Alternatively, only if organisations conform their action to that stated by the institution, will the latter be able to pursue assigned purposes and generate direct advantages for each member, with a ‘win-win’ mechanism.

If industry self-regulatory institutions have been extensively studied, scholars have neglected the role that accounting can have in their functioning, and as imitation mechanisms, which are typical of this kind of institution. In the literature, accounting practice is also considered a tool to evaluate alternatives, simplify exchanges through reciprocity and adjudicate economic claims and social relations (Tinker Citation1985; Carmona, Ezzamel, and Gutiérrez Citation2006). In the case examined, the analysis of accounting books can be interpreted as a need that organisations had to satisfy. For each organisation belonging to the textiles industry, the need to acquire and to analyse the financial information of customers involved in bankruptcy proceedings represented a key factor for the functioning of the self-regulatory institution, influencing members’ adhesion and behaviour.

The role of accounting in this study is twofold. On the one hand, the ability of the Union to conduct the analysis of accounting books in a very significant number of bankruptcy procedures represented a key factor at the base of the imitation mechanisms, given that a single member could not replicate it alone, when also considering the geographical distance, the means available, and the related costs. On the other hand, the examination of the Union journal, where the analysis of the accounting books was published, represents in this analysis one of the main sources for understanding the activity carried out by the Union and its functioning mechanisms.

This study is organised as follows. The next sections summarise the theoretical framework and the research method. Then, the role of the analysis of accounting books in the functioning of the Union and in preserving the textiles industry at the end of the nineteenth century is illustrated. In the final section, the findings and concluding comments are discussed.

Theoretical framework

In the literature, several scholars have focused on the concept of institutions (Zappa Citation1956; Masini Citation1968). North (Citation1990) distinguishes between institutions with formal constraints from those with informal constraints. Other researchers suggest that institutions should also be distinguished as public or private, and centralised or decentralised (Zappa Citation1956; Masini Citation1968; Ingram and Clay Citation2000). If public institutions are in general created by the State, private institutions are instead based on the voluntary membership of organisations. In centralised institutions, the role played by a central authority is fundamental. Decentralised institutions, in contrast, are mainly based on the behaviour and the grade of cohesion of their members.

In the past, studies on private self-regulatory institutions have outlined scepticism in regard to their functioning, due to the absence of a central authority disciplining members’ behaviour (Olson Citation1965). More recently, several studies have shown that the establishment of industry self-regulatory institutions can instead reduce a common problem (Barnett and King Citation2008). In other words, it is in the interest of organisations to collaborate when alone they are not able to cope with a common threat. In this sense, an industry self-regulatory institution can motivate members to co-operate with compliant actions, affecting the achievement of specific purposes, such as the protection of common goods, the regulation of the industry or its reputation (King, Lenox, and Barnett 2002; Yue and Ingram Citation2012).

Thus, this study adopts institutional theory, according to which it is necessary to also observe those forces that lie beyond organisational boundaries (Scott Citation1995) and, in particular, the ‘functionalist’ view of institutions. From this perspective, industry self-regulatory institutions are constituted to reduce threats and promote more efficient social and economic exchanges (Williamson Citation1985; North Citation1990; Stefanadis Citation2003). With reference to how an industry self-regulatory institution can achieve these goals, operating effectively, the literature suggests two possible ways.

Self-regulatory institutions can introduce explicit sanctions to prevent the opportunistic conduct of members (Scholtz Citation1984; Grief Citation1997). Some scholars claim that, without sanctions, firms could also adopt common guidelines, but would hardly implement them. Left to themselves, firms would take different decisions in responding to external pressure (King and Lenox Citation2000).

As an alternative, according to institutional isomorphic change theory (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983), mechanisms exist that can contribute to make the behaviour of members of an institution uniform without resorting to explicit sanctions. Self-regulatory institutions can operate successfully through coercive, normative or mimetic forces (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1991; Scott Citation1995; Nash and Ehrenfeld Citation1997).

Coercive forces are closely related to the formal and informal pressures that certain organisations may exert on others. The aforementioned pressures can be identified as persuasion or invitations to join in collusion. Industry members can also put pressure on actors through social penalties (Gunningham and Rees Citation1997; King and Baerwald Citation1998).

The behaviour of members can also be guided using normative forces. This form of organisational power stems mainly from professionalisation. Self-regulation can support the introduction of new norms and values that change the member behaviour for collectively valued actions (Jennings and Zandbergen Citation1995; Hoffman Citation1999). Moreover, an institution can promote the dissemination of codes, standards and guiding principles, increasing aggregate learning and collective performance (Terlaak and King Citation2006).

Imitation mechanisms can influence member behaviour with mimetic forces. Imitation mechanisms are mainly based on the following considerations: (i) only certain organisations have information which enables decisions to be made; (ii) organisations inevitably face some information uncertainty regarding the appropriateness of which decisions to adopt; and (iii) when in an organisation’s network the adoption of a specific practice increases, the quantity of influence or social information also increases and, as a consequence, the spread of the practice is more probable inside the network (Haunschild Citation1993). These imitation mechanisms can be classified into three different categories: bandwagon imitation, status-driven imitation and social learning (Kraatz Citation1998).

Firms could join the association simply because other firms have already joined, without a rational justification, as in a bandwagon (Abrahamson and Rosenkopf Citation1993). Status-driven imitation, in contrast, is based on the imitation of the most important or larger organisations, given that they are more visible and can favour the dissemination of more detailed and useful information.

Finally, the social learning perspective considers that imitation is mainly due to the higher quality and volume of information that can be acquired through peers. Furthermore, the social learning view suggests that an organisation can evaluate the outcomes for peers and take advantage of information of their earlier decisions. In other words, an organisation will only imitate when the outcomes for its peers will be advantageous and feasible for itself.

Imitation mechanisms may have been extensively studied, but the role that accounting can have for an industry self-regulatory institution has been neglected. In the literature, accounting practice was also considered a tool for evaluating alternatives, simplifying exchanges through reciprocity and adjudicating economic claims and social relations (Tinker Citation1985; Carmona, Ezzamel, and Gutiérrez Citation2006). Thus, accounting practice was defined as: ‘a means of resolving social conflict, a device for appraising the terms of exchange between social constituencies, and an institutional mechanism for arbitrating, evaluating, and adjudicating’ (Tinker Citation1985, 86).

In addition, studies increasingly emphasise the interaction between accounting and people’s behaviours and actions, considering the former a social and institutional practice, in relation to organisational and social dynamics. From this perspective, accounting can be viewed as a tool of power and control in shaping organisational cultures (Covaleski and Aiken Citation1986; Neimark and Tinker Citation1986; Morgan Citation1988).

In this case, the analysis of accounting books can be interpreted as a need that organisations have to satisfy. The need to acquire and to analyse their counterparts’ financial information, such as customers involved in bankruptcy proceedings, can represent a key element for an institution aimed at self-regulating an industry and preserving fairness in trade relationships, influencing members’ adhesion and behaviour.

Historical studies have already focused on merchant networks (Gervais Citation2008; McWatters and Lemarchand Citation2009, Citation2013) and, to a lesser extent, also on industry self-regulatory institutions (Gorton and Mullineaux Citation1987; Balleisen Citation2009; Yue, Luo, and Ingram Citation2009; Yue and Ingram Citation2012). Bankruptcies have also been widely investigated in the literature. Some studies have highlighted the role of the analysis of insolvency procedures in contributing to the understanding of economic crisis (Di Martino Citation2005). Other researchers have focused on bankruptcy procedures to more deeply comprehend the reasons for economic sector growth (Rodger Citation1985; Di Martino and Vasta Citation2010; Solar and Lyons Citation2011), the development of the modern state (Lester Citation1995) and to compare, among countries, the functioning of bankruptcy law and practices (Hautcœur and Di Martino Citation2013). Bankruptcy proceedings have also been studied to an extent to verify the degree of professionalisation of accountants (Walker Citation2004; Labardin Citation2013), and whether legislation has influenced the diffusion of accounting practices (Labardin Citation2011). At the same time, as shown by several studies, accounting history represents a complementary approach to research in history and, in particular, for that conducted through the use and the interpretation of reports and accounting information (Walker Citation2008; Hernández Esteve Citation2010). Thus, an accounting perspective can enhance knowledge, helping to explain the effects and dynamics of inter-organisational and social relations (Rezaee Citation1998; Walker Citation2005).

Considering that a thorough analysis of a self-regulatory institution cannot ignore its functioning and the means through which it pursues its aims, in the following sections, we focus our attention on the dynamics of the institution.

Research methods

Our research is based on a case study (Yin Citation2009) of the Union of Textile Manufacturers and Traders of Milan, between the end of the 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s. The analysis was carried out in several phases. We initially examined the legal, economic, and social context in which the Union arose and operated. We also analysed the Italian Laws governing bankruptcy proceedings, and examined their status in the Italian Courts.

Secondly, attention was turned to the function and activities carried out by the Union. In this regard, a significant factor was the analysis of accounting books undertaken by the Union on the different insolvency proceedings involving members’ credit rights. Further examination was made of the organisations belonging to the Union which, as we will illustrate, determined the impact and effectiveness of its activities and, thus, its ability to have a significant impact on the textile industry.

The following documentation was examined:

the 1882 Italian Commercial Code;

the Italian Law n.197/1903 (‘Reform of moratorium and introduction of pre-bankruptcy arrangements’);

the Articles of Incorporation of the Union;

all the editions of the fortnightly (later monthly) Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture ( Journal of the Union of Textile Manufacturers and Traders of Milan), distributed to members from 1899 to 1902; the journal contains the results and evidence of the analysis of accounting books undertaken by the Union, of legal actions and, in general, of all the other activities carried out; it also contains reports and meeting minutes of the Executive Committee (Della Peruta and Cantarella Citation2005);

additional journal articles published between 1899 and 1905 in the Rivista di diritto commerciale, industriale e marittimo ( Journal of Commercial, Industrial and Maritime Law), in the daily newspaper Il Sole and in the periodicals Il Commercio and Il Ragioniere, discussing, also from a legal point of view, the role of the Union and its activities (Carretti Citation1899; Sraffa Citation1904, Citation1905; Ascoli Citation1905a, Citation1905b; Bonelli Citation1905);

a study entitled ‘Fallimenti in Italia nel triennio 1900-1902’ (‘Bankruptcies in Italy in the three-year period 1900-1902’), made by the Judge Penserini, presented to the ‘Commission for judicial and notarial statistics’ in January 1904 and published in the above-mentioned commercial law journal (Penserini Citation1904); and

historical data published by ISTAT (Italian National Statistics Institute), for the years 1881-1910, with particular reference to data on ‘Protests and bankruptcies’, ‘Default and insolvencies’, and ‘Crimes of deception and other frauds in trade and industry’.

Hereinafter, certain brief considerations will firstly be made about the development of the textiles industry in the Kingdom of Italy over the final two decades of the nineteenth century. This discussion is followed by an outline of bankruptcy law, the state of insolvency proceedings and the associated business malpractices existing at the time. We then focus our analysis on the role the Union played in this scenario, and on the industry in question.

The textile industry in the Kingdom of Italy at the end of the 1800s

In the second half of the nineteenth century, unlike most of the Central European countries, the nascent Kingdom of Italy was in a state of relative industrial backwardness. Despite the achievement of political unity, a difficult and complex economic and social situation continued to persist, characterised by profound regional inequalities (Nobolo, Guarini, and Magli Citation2013; Catalfo, Barresi, and Marisca Citation2015).

Between 1880 and 1890, Italy suffered a serious economic crisis. Certain events negatively affected economic development in the Kingdom, stoking the sense of social unease and dampening the optimism that was beginning to grow among the representatives of the economic, financial, and political system. We refer specifically to the agricultural crisis which reached its peak in the three-year period 1885–87. This crisis – caused by the increased international level of low-cost intensive farming, which brought about a collapse in wheat, corn and cereal process in general – hit the rural classes, who represented 80 per cent of the population at the time (Clough Citation1965).

This crisis accentuated the delay in Italian economic and social development by increasing the poverty rate that affected a large part of the population. These factors contributed to a slowdown in the process of harmonising the national policies of the Kingdom which were often the cause of social conflict (Luzzatto Citation1963).

Over the following years, between 1888 and 1894, characterised by a serious depression with a general fall in ferrous metal and property prices, numerous banks suffered a liquidity crisisFootnote 1 , leading to the collapse of the credit system (Lardo et al. Citation2018). Finally, in 1897, the poor wheat harvest, the resulting increase in bread prices and the riots which followed only served to accentuate the malcontent of the population (Corbino Citation1962; Cardini Citation1981).

Despite the difficult economic situation which was gripping the country, the influence of the industrial revolution on economic growth in Western Europe, particularly in the textiles industry (Chandler Citation2019), had also brought benefits to the Kingdom of Italy. Unlike other industries, textiles experienced an almost constant rate of growth, being only slightly affected by the crisis. To understand the economic and social importance of this industry within the Kingdom, we underline the boom experienced by the cotton industry, which grew from 627 firms, 52,000 employees and production worth 51 million lire in 1876, to reach 727 firms, 135,000 employees and production worth 304 million lire in 1900 (Cafagna Citation1977).

At that time, the development of the textiles industry in the Kingdom can mainly be linked to the positive effects of customs barriers and the use of parallel and autonomous forms of credit provided by local banks, often in a co-operative form, rather than the national bank system, as well as the audaciousness, enterprise, and ability of certain forward-thinking businessmen.Footnote 2 A new class of entrepreneurs was taking hold in northern Italy which was ‘more dynamic and aggressive, tending to impose non-traditional models and values of behaviour’ (Castronovo Citation1980, 80).

The production process was modernised with the introduction of mechanical looms and the creation of large-scale factories, working methods were reorganised by introducing the modern concept of factories, and businesses merged, signalling the definitive passage from artisanal textile production to full-blown industrial production. The most significant distinguishing feature of the new entrepreneurial class was the development of trade on a national and international level, with the distribution and marketing of textile products throughout the Kingdom of Italy, through the creation of a network of salesmen, agencies, and branches (Castronovo Citation1977).

The development of trade in the textiles industry, however, soon had to face up to the crisis, to the rigidity and wide variations in local markets, with the risk of insolvency for commercial brokers and retailers, as well as widespread business malpractice, particularly when dealing with firms in trouble and insolvency proceedings.

Bankruptcy legislation in the Kingdom of Italy

After the unification of 1861, the first Commercial Code was enacted in the Kingdom of Italy in 1865. This Code cannot be considered a structural reform of commercial law. It was nothing more than an extension of the Code previously in force in the Kingdom of Sardinia to the rest of Italy. A real process of Commercial Law reform, including reform of Bankruptcy Law, was set in motion in 1877, at the height of the ‘Juridical Risorgimento’. It was a proposed substantial reform of the Commercial Code, since it was heavily influenced by outdated Napoleonic law (Alpa Citation2007). The German model was adopted instead, which was better suited to the ongoing process of industrialisation and the development of trade. The proceedings of this Commission led to the enactment of the 1882 Code (the so-called ‘Mancini Code’), which came into force on 1 January 1883.

The new Commercial Code was divided into the following four sections: Section I, ‘On commerce in general’; Section II, ‘On maritime and shipping commerce’; Section III, ‘On bankruptcy’; and Section IV, ‘On trading activities and their duration’.

Respect of other countries, like England, France and Germany, that introduced a pre-bankruptcy legislation during the second half of nineteenth century (Hautcœur and Di Martino Citation2013), the Italian bankruptcy law (Section III) was substantially based only on two procedures: moratorium and bankruptcy. With a moratorium, the debtor could obtain a deferral in the event that bankruptcy was declared (or before, avoiding the opening of the procedure), if the debtor was able to justify that the termination of payments was the consequence of extraordinary and unforeseeable events or with suitable guarantees that assets exceeded liabilities. As an alternative, after the bankruptcy decree, the debtor could propose an arrangement, under the strict surveillance of the Court (Bolaffio Citation1903). The bankruptcy arrangement had to be approved by 75 per cent of creditors (in terms of the worth of credits).

According to Section III, the organs of bankruptcy proceedings were the Commercial Court, the Judge delegated, the Creditors committee and the bankruptcy Trustee. The Judge delegated exercised supervisory and control functions on the regularity of the procedure. The Creditors committee controlled the bankruptcy Trustee and authorised specific acts. The general function and role of the Trustee was to get in, realise and distribute the bankruptcy estate in accordance to the law, reviewing and adjudicating creditors’ claims. The bankruptcy Trustee inventoried and managed the assets, securing them, carrying out all the operations of the procedure under the supervision and the control of the Judge delegated and the Creditors committee.

Over the period examined, therefore, commercial and bankruptcy laws had only been recently adopted and had not had sufficient time to become consolidated in practice and case law. Furthermore, they were not always applied uniformly in the Courts of the Kingdom. In comparison with England, Germany and France, the Kingdom of Italy was the worst performer in the protection of creditors’ rights (Hautcœur and Di Martino Citation2013). In particular, the average length of procedures was significantly longer respect of the other countries considered. The deep regulations and the strict conditions adopted, and the delay in introducing pre-bankruptcy arrangements legislation (eliminating the moratorium), happened only in 1903, also had the effect of slowing procedures down, with an increase of complexity and related costs of bankruptcy procedures (Hautcœur and Di Martino Citation2013). This negatively affected the development of the Italian economy and, in particular, of the textiles industry, where the growth was mainly based on the credit lines granted by suppliers.

Commercial frauds and mismanagement of bankruptcy proceedings

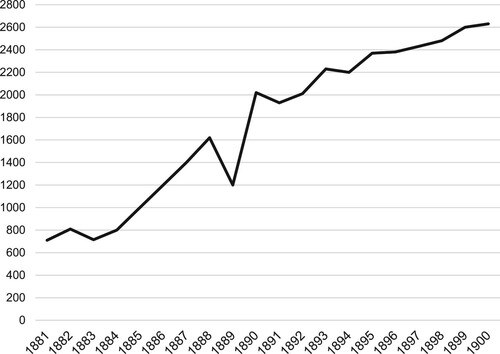

Due to the crisis, in the decades 1881–1900 the number of business bankruptcies in the Kingdom of Italy increased significantly (see ).

Figure 1. Number of new bankruptcies and protests in the Kingdom of Italy (per year).

Source: ISTAT ‘Protests and Bankruptcies’ (1881-1900).

At the same time, during this period the Kingdom of Italy also suffered a crisis of entrepreneurial morality and honesty:

Strict morality of fair trading, regulated, honest in all its undertakings, preoccupied above all with its honour and good name has unfortunately been replaced by very different conditions which are rapidly spreading. … They are things that everybody knows about: businesses set up without capital, indeed with debts; trade conducted carelessly, lightly, behind the backs of the incautious and deceived; falsification and sophistication of goods were commonplace; disputes for the termination of contracts, in which the only reason for termination is the increase or decrease in the price of the goods. Finally, after a long series of simulations and deceptions, bankruptcy, presented in a void and with no assets.Footnote 3

A statistical survey entitled ‘Bankruptcies in Italy in the three-year period 1900-1902’ relating to the insolvencies proceedings in force in the Kingdom – the results of which were published in 1904 in the Rivista di diritto commerciale, industriale e marittimo – highlighted that, in many cases, using any expedient and abuse of credit, bankrupts continued to do businesses, leaving very little or nothing to creditors.Footnote 4

As a consequence, the textiles industry was often faced with the problem of illicit and immoral business practices. In fact, certain shopkeepers traded in a way damaging to textile manufacturers and wholesalers by failing to honour their obligations and often voluntarily placing their business in bankruptcy to gain unfair advantages. This malpractice was prevalent in Southern Italy, with an indiscriminate abuse of the credit lines granted by suppliers.Footnote 5

The spread of these malpractices was also attributable to the widespread mismanagement of insolvencies proceedings, mainly due to the selection of bankruptcy Trustees.Footnote 6 Unlike other jurisdictions, such as England and Wales, where in everyday practice accountants and lawyers maintained relation of mutual dependency in bankruptcy work (Walker Citation2004), or France, where the role of lawyers was preeminent (Labardin Citation2013), in the Kingdom of Italy bankruptcy Trustees were appointed selecting among heterogeneous categories of professionals, frequently unprepared to manage this kind of procedure. As observed:

With the exception of Milan and Genoa [where accountants were preeminent] … there is everything. There is the accountant, the lawyer, the surveyor, the doctor, the young notary, the shopkeeper, even bankrupt. There is, in a word, a strange mixture of people, of studies, of activities, of social conditions, very disparate.Footnote 7

With this regard, the aforementioned statistical survey revealed that in some areas, such as in Naples, there were complaints of gross negligence of bankruptcy trustees, also due to the absence of control. In addition, in most cases, there was a ‘simply frightening’ amount of procedure costs, and the legal expenses were about one third of the assets to be liquidated. Doubts were also raised about the payment of liquidators which ‘does not always happen judicially due to lack of claim, something which unfortunately happens due to agreements, not free from suspicion, between liquidator and debtor in bankruptcy arrangements’.Footnote 8

Finally, particular importance was attached to the misinterpretation and ‘inadequate’ application of bankruptcy law by the Courts. In this sense, as an example, the above-mentioned survey pointed out that the Court of Savona was still hearing bankruptcy cases from 1890, from 1873 and even from 1865. Moreover, the Court of Genoa had dismissed 51 procedures as being resolved even though they were not, six of which had been running for more than 20 years, seven for more than 13 years and nine for more than five years.

Unusual assertions by certain public prosecutors were also reported in the study, including those in Siena, according to whom ‘it is positive that the liquidators in almost all bankruptcy cases take on and get rid of whatever suits them best’.Footnote 9 As examples of infringements of the law committed, out of ignorance, by Judges, the study revealed that the Court of Sassari granted a moratorium, in clear violation of the law, to a firm without accounting records and with debts of over seven million lire, and the Court of Brescia only approved bankruptcy arrangements if payments were due within only two months (Penserini Citation1904).

Il ’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture di Milano (the Union of textile manufacturers and traders of milan)

Considering the previous discussion, the end of the nineteenth century witnessed the rise of a new phenomenon of spontaneous association among businessmen aimed at fighting malpractices, protecting credit rights in insolvencies proceedings, and promoting the growth of trade and spread of good business practices (Balleisen Citation2009).

In the textiles industry, thanks to the efforts of Professor ‘Ragioniere’ Ottorino Ponti, the ‘Unione Commercianti in Manifatture di Milano’ was created in 1898. The Union aims were:

(…) fight against the speculation of insolvency; put an end to interference by opportunists making a living out of suggesting to bankrupts how they could deceive creditors and the law and make a profit out of their insolvency; ensure that assets from insolvencies were not transferred or sold to relatives or friends of the bankrupt or at ridiculously low prices, to the great detriment of morality and honest trade.Footnote 10

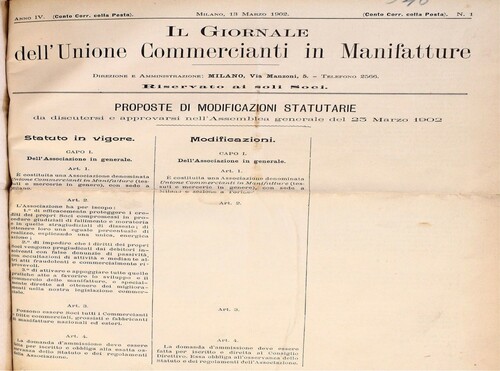

According to paragraph 2 of the Articles of Incorporation (), it set out:

to effectively protect the credit of its members compromised in bankruptcy, insolvency and moratorium proceedings; to obtain for them a fair percentage of recovery, through the exercise of vigorous unified action;

to prevent the rights of its members being prejudiced by insolvent debtors making false declarations of liabilities, hiding assets and through other fraudulent and commercially deplorable acts; and

to expedite and support all practices aimed at promoting the development of textiles industry and particularly aimed at achieving improvements in commercial legislation.Footnote 11

Figure 2. Paragraph 2 of the Articles of Incorporation of the Union.

Source: Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1902, n. 1, p. 1.

Based on the pursuit of these objectives, this institution aimed also to protect morality and fairness in trade relationships, as well as to increase trust among businessmen belonging to the textile industry.

The Union was created in 1898 with an initial trial period of 18 months, ending in 1899, during which no sanctions were applied. During the trial period, the Union verified the feasibility of its aims and activities, its relationships with members, and their cohesion. The Union tested the behaviour of members and their respect for obligations and rules provided by the Articles of Incorporation, as better illustrated in the subsequent paragraphs, consolidating trust among members and between members and the Union.

The main organs of the Union were the ‘Consiglio Direttivo’ (Executive Committee), the ‘Studio’ (Legal and Accounting Office) and the ‘Adunanza Generale’ (General Meeting). Moreover, three Auditors were appointed by the General Meeting.

The Executive Committee, composed of 27 members (reduced to 22 in 1902), was the governing body of the Union. It was the legal representative of the Union, called the general meetings, and decided on the admission of members. It appointed the Director of the Legal and Accounting Office and dealt with all matters pertaining to the pursuit of the association’s aims. The Executive Committee members, chosen by the General Meeting and re-electable, elected a President and a Vice-President by majority vote and performed their duties without remuneration. Their term of office was two years (paragraph 13–19 of the Articles of Incorporation).

The Legal and Accounting Office was given the task of analysing the insolvency proceedings files in which members were involved as creditors. Furthermore, it represented Union members in legal matters to defend their rights under commercial and bankruptcy law. For this reason, each member had to specifically grant power of attorney to the Director (paragraph 25–31 of the Articles of Incorporation).

The General Meeting was the decision-making body of the Union: it was called by the Executive Committee, approved the ‘Relazione sull’andamento morale e finanziario dell’Associazione’ (‘Report on the moral and financial situation of the Association’) drawn up by the Executive Committee and reviewed by the Auditors, and voted on resolutions concerning changes to the Articles of Incorporation. It also met at the request of one tenth of the members (paragraph 20–24 of the Articles of Incorporation).

The membership fee, the same for each organisation, was 100 lire per year. In addition, from 1900, the Union introduced a system of expense reimbursement for the activities carried out. The system was based on percentages calculated on the worth of credit rights involved in insolvency proceedings, with a minimum of 0.50 per cent to a maximum of 2.50 per cent. Percentages were inversely proportional to the amount of credit involved in a single proceeding.

Union membership

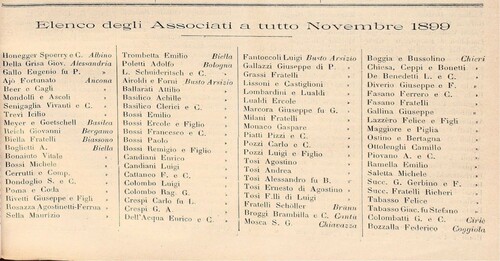

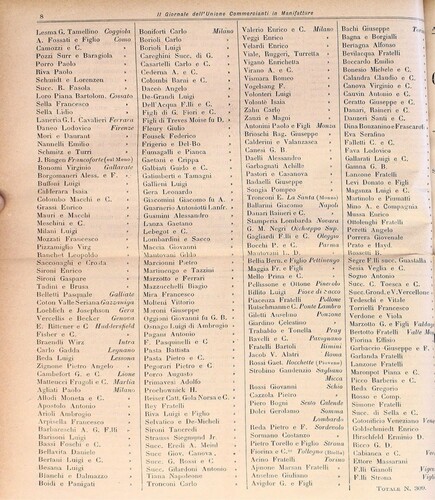

Created in 1898, considering its activities and the evident advantages generated for associates, the Union quickly spread throughout the Kingdom of Italy and internationally. Operating in the production and trading of textiles products, members were also based in several European cities, including Basel (Switzerland), Brunn (Austria), Frankfurt (Germany) Huddersfield (United Kingdom) and Lyon (France). In May 1899, the members had grown to 236 and, at the end of the same year, to 309 ( and ). After just a few years, in 1900, membership reached 342.

Figure 3. Membership list for November 1899 (part I).

Source: Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 11-12, p. 7.

Figure 4. Membership list for November 1899 (part II).

Source: Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 11-12, p. 7.

The members of the Union included the Rossi family from Schio, the Dell’Acqua family from Busto Arsizio, and the Marzotto family from Valdagno, representing the largest and most influential textile manufacturers of the Kingdom of Italy. At the end of the nineteenth century, the Rossi Wool Mill was the largest wool producer in Italy, with numerous factories in the north of Italy. As well as developing its factories, the Rossi family took various social initiatives, which were forward thinking for their time, such as the creation of worker villages, professional schools, clinics, and boarding schools (Castronovo Citation1980). In 1898, the Wool Mill covered an overall area of 16 hectares, employed about 5000 workers, and produced goods worth about 20 million lire, creating a substantial position monopoly on the national market (Avagliano Citation1977).

Another firm that played an important role in the development of the Italian textile sector was the ‘Dell’Acqua family’. The firm achieved substantial growth from 1871 thanks to Enrico dell’Acqua. Inheriting the business established by his maternal grandfather, Pietro Provasoli, Enrico set up a mechanical tessitura in Castrezzato, with the products being refined and tinted in Busto Arsizio. He extended his trading firstly throughout the Kingdom of Italy and, later, in Latin America (Caizzi Citation1965). To achieve this expansion, he collected a great deal of information on markets, customs, and local preferences through parish priests, tax offices and Carabinieri stations, carrying out an elaborate ‘market survey’. In 1898, Dell’Acqua’s businesses included two factories and hundreds of agencies and branches in Latin America, where the products were marketed under the trade name ‘Vedetta’ (Einaudi Citation1900).

In 1836, in Valdagno, the Luigi Marzotto & Sons Wool Mill was founded. In the late-nineteenth century, the business experienced strong and rapid growth. This remarkable success was partly due to the opening of the Wool Mill to international markets. To this end, in 1890 the Marzotto family participated in the founding of a company for the export of Italian textile products to Latin America, together with the Dell’Acqua family. Moreover, they extended their trade to Central and Eastern Europe. Along with the Rossi family, they were one of the founders of the ‘Associazione dell’industria laniera italiana’ (‘Italian wool industry association’).Footnote 12

Other members of the Association included:

the ‘Cantoni Cotton Mill’, owned by Costanzo Cantoni (from Gallarate), the leading producer and distributor of cotton products in Italy (Romano Citation1977);

the ‘Honegger-Spoerry Cotton Mill’ in Albino, which in the early years of the twentieth century was equipped with an electricity generation station and a mechanical workshop and employed 1300 workers;

the ‘Valle Seriana Cotton Mill’ in Gazzaniga, owned by the entrepreneurs Alberto Amman, Paolo Muggiani, Andrea Taroni and the brothers Rodolfo Walty and Federico Widmer Walty; in 1891 the Cotton Mill owned two factories (in Gazzaniga and Casnigo), used about 44,000 spindles and employed 1800 workers;

the ‘Manifattura Tosi’ in Busto Arsizio which, in the early 1900s, employed 2000 workers;

‘Gianoli Bros.’ in Vigevano, operating in the spinning and weaving of cotton. In 1896, the factories in Predalata and Molino del Conte used about 18,000 spindles and employed about 1100 workers; and

‘Lissoni-Catiglioni and Co.’ in Busto Arsizio, which became the ‘Dell’Acqua- Lissoni-Castiglioni Cotton Mill’ in 1907, with about 1000 workers.

Activities carried out by the Union: the accounting and legal autopsies

The Union was characterised by intensive activities, which became wider-reaching and more targeted as the membership grew. The following paragraphs outline the principal activities carried out between 1898 and 1902.

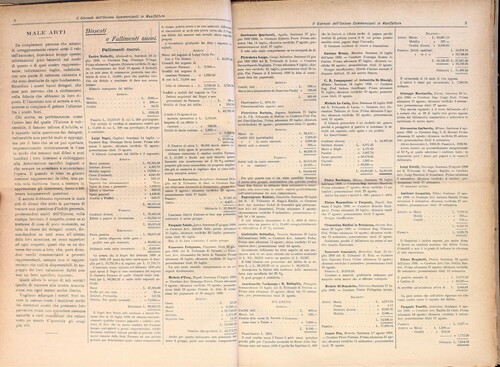

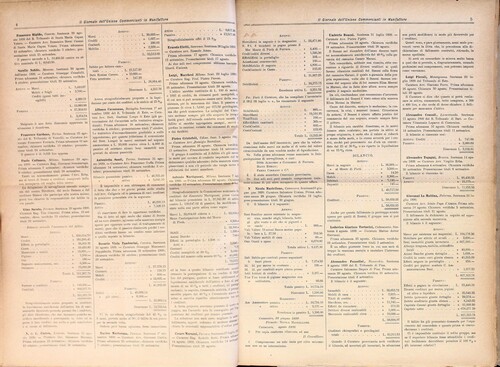

Accounting and legal analysis of the insolvency proceedings. Once members notified the Union about the existence of insolvency proceedings in which they were creditors, the Legal and Accounting Office had the task of examining the proceeding documents and inspecting the debtor’s accounting books and financial statements, to check if they were in order. In addition, it had to investigate the causes of cessation of payments, as well as to check if liabilities were overstated and assets hidden or understated.Footnote 13 The results of the analysis were reported in the journal of the Union to update the members ( and ).

Figure 5. New proceedings (part I) – August 1899.

Source: Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 5-6, p. 2-3.

Figure 6. New proceedings (part II) – August 1899.

Source: Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 5-6, p. 4-5.

In the most significant proceedings, ‘accounting and legal autopsies’ were conducted, ‘thus discovering the disease that led to the death of the business’. From the analyses undertaken, it emerges that some of these were ‘appalling bankruptcies’, in many of which the Union had refused a bankruptcy arrangement, imposing a ‘state of liquidation, both because of the miserable proposals put forward, both because the bankrupts were not morally worthy of any special consideration’.Footnote 14 In other cases, the Legal and Accounting Office put in evidence the incoherence between financial statements presented by the bankrupt and the reasons adducted for the termination of payments. In particular, despite no accounts receivables were indicated in the Balance Sheet, many bankrupts justified their financial situation with the impossibility to collect money from customers.

As evidence of the great work done by the Union in support of its members, between 1898 and 1902, the Legal and Accounting Office dealt with 1745 moratorium, bankruptcies and arrangements, with the members credit rights involved worth 5,475,000 lire; of these, 1143 were settled with an amount recovered equal to 2,437,480 lire (44.52 per cent of the amount of credit rights involved). The considerable commitment of the Union also helped to reduce the average length of bankruptcy arrangements. The average length was three months, a very short time in comparison to those reported in the years before the Union was founded, when the average according to official state statistics was over six months.Footnote 15

Legal action necessary for protecting members’ credit. Legal actions could not be taken by individual creditors, ‘because it was very expensive and subject to outcomes often subordinated to surcharge calculations which only a solid creditors’ union can calculate and demonstrate with certainty’.Footnote 16 From this perspective, unifying the credit rights of each single member in a sole legal action, promoted by the Legal and Accounting Office of the Union, had the advantage of sharing legal costs and exercising significant pressure, avoiding proceedings malpractice and heterogeneity in judgements, and contributing to establishing balanced judicial practice.

Studies and surveys on the interpretation and application of commercial and bankruptcy laws in the main Courts of the Kingdom of Italy. The surveys carried out concerned, in particular, the Courts of Venice and Palermo. The results highlighted the existence of ‘[a]s many lines of decisions as there are Courts, as many procedures as there are court clerk’s offices’.Footnote 17 Numerous defects and irregularities were found at the Court of Venice. For this reason, it proved necessary to devise.

a single precise regulation for insolvencies proceedings, and where, more than other places, Judges need to wake up and follow proceedings, so as to be able to report to the Court on the basis of their knowledge of the case, rather than relying on reports from liquidators, who are often not up to the tasks entrusted to them.Footnote 18

An equally alarming picture of complete inefficiency and inertia emerged from the Court of Palermo. In this Court, the judges ‘seemed to be indifferent to the fact that creditors’ interests were trampled on and reviled, as long as they saved the bankrupt, who was a victim of the creditors’ greed!’Footnote 19

Publication of a periodical. May 1899 saw the first edition of Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture. Specifically, the periodical – initially published fortnightly and later monthly – informed its members about the state of bankruptcies and defaults analysed by the Legal and Accounting Office and in which the Union had intervened to protect credit rights. It also reported initiatives and proposals put forward by the Executive Committee, as well as those promoted by one or more of the members. In addition, it published surveys carried out by the Legal and Accounting Office. Moreover, the periodical permitted an exchange of information between the membership and the Executive Committee, which was vital for the pursuit of the Union’s aims.

Influence in improvements to bankruptcy legislation. The Union also concentrated its attention on the reform of commercial and bankruptcy laws, as was already happened in other countries (Lester Citation1995; Praquin Citation2012). Numerous initiatives were undertaken with the aim of improving legislation in force. In particular, also under the pressure of the Union, with the Italian Law n.197/1903 (Reform of moratorium and introduction of pre-bankruptcy arrangements), the moratorium proceedings were replaced by the pre-bankruptcy arrangements. As previously outlined, with the Commercial Code of 1882 the debtor could obtain only a deferral in the event that bankruptcy was declared (or avoid to opening the procedure) if the debtor justified that the termination of payments was the consequence of extraordinary and unforeseeable events or suitable guarantees that assets exceeded liabilities.

Considering that the moratorium had not provided adequate evidence, in 1903 it was replaced with the pre-bankruptcy arrangements allowing the friendly settlement of commercial distress substituted for the declaration of bankruptcy. Therefore, these new proceedings were configured as a ‘benefit’ for the deserving ‘honest but unfortunate’ debtor, with the effect of determining an exemption from bankruptcy (Bolaffio Citation1903).

The new law foresaw a creditors’ mechanism of a vote equivalent to the one adopted by the Union, but with a percentage of 40 per cent, instead of 50 per cent as indicated in the Union Articles of Incorporation, as shown in the following section.

The deterrent function of the Union against trade malpractices and frauds

Thanks to the large number and economic relevance of its members, the Union was able to acquire a central role in trade that allowed it to exercise a ‘deterrent’ function against the trade malpractices widespread in Italy. The Union’s ability to positively influence commercial activities facilitated the process of building a solid reputation in the textile tradeFootnote 20 , generating ‘healthy apprehension’ among unfair and dishonest traders.Footnote 21

Moreover, the Union acquired a ‘dissuasive value’ for bankrupts and defaulters who hoped to make illicit gains from voluntarily making themselves insolvent. Equally, it was a disincentive for those who intended to start trading solely to abuse the credit granted to them by suppliers. In this sense, in 1899, discussions took place to introduce a ‘special book, the so-called Black Book, for recording in detail the moral and material character of all bankruptcies, so that everyone can judge seriously for themselves’.Footnote 22 The inclusion of an obligation not to supply goods to bankrupts and defaulters in the Articles of Incorporation was also discussed.Footnote 23

The strength of the Union, therefore, depended on the degree of cohesion of its members. For these reasons, membership of the Association meant accepting very stringent rules and obligations, which restricted the initiatives each member could take.Footnote 24 For example, paragraph 35 of the Articles of Incorporation allowed for members who were creditors in the same bankruptcy proceedings to ‘take legal action in a group’, accompanied by the prohibition that they could not ‘take any independent action or decision regarding protection and liquidation of their credit, surrender it to others, accept arrangements in or out of court, sign any form of agreement with bankrupts, defaulters, or third parties, start or pursue court cases’.Footnote 25 To this end, members were obliged to grant specific power of attorney to the Director of the Legal and Accounting Office, who represented the group, and who had exclusive responsibility for taking legal action for the enforcement of credit rights.

Paragraph 38 of the Articles of Incorporation laid down the obligation not to accept arrangements that provided for payment of creditors at a level below 50 per cent. The Executive Committee could make a final decision to approve arrangements providing for a lower level of liquidation, once it had been ascertained, after the accounting and legal analysis, that the causes of the bankruptcy were not linked to malpractice or illicit behaviour. Alternatively, arrangements that provided for a higher percentage of payment to creditors were to be considered binding and compulsory for all members when the majority, represented by more than half of the total credit of the group, voted in favour.

From this perspective, the analysis of accounting books also assumed a social function, permitting the Union to distinguish between honest but unfortunate and dishonest debtors. Only for the unfortunate debtors was it possible to accept arrangements with a lower level of payments.

Failure to fulfil obligations laid down in the Articles of Incorporation led to members being fined an amount that varied from 1000 to 5000 lire, and the ‘moral’ sanction of being expelled from the Union (paragraph 7 and 36 of the Articles of Incorporation). However, as has been authoritatively observed, the ‘loyalty’ of members to the will expressed by the Union was based more on ‘members’ sense of solidarity’ than on the binding nature of the obligations (Ascoli Citation1905). It was also highlighted that ‘it is almost impossible that any members attempt to evade their obligations, mainly because those who participate in such conventions know that the importance of the latter lies in its existence’.Footnote 26

For these reasons, it is evident that the ‘loyalty’ of members depended mostly on the direct advantages that the Union was able to generate to each of them, with particularly reference to analysis of accounting books of businesses in bankruptcy and legal action taken as a group, discouraging the opportunistic behaviour of members.

Discussion and conclusions

The objective of this study has been to analyse the role that accounting can assume for the creation and the functioning of an industry self-regulatory institution, as well as a mimetic force. At the end of the 1800s, manufacturers and traders operating in the textiles industry had to face up to the significant spread of bankruptcy among their customers. In many cases, their clients adopted fraudulent behaviour to gain illicit and unfair advantages. More than in other countries, like England, France and Germany, where pre-bankruptcy arrangements were already adopted and bankruptcy legislation and practice were more effective and efficient, the misinterpretation of bankruptcy law, with the mismanagement of insolvency proceedings, accentuated these practices, limiting the ability to protect credit rights.

In this new scenario, manufacturers and traders needed to manage the credit rights involved in a significant number of bankruptcy proceedings, evaluating whether it was possible and convenient to adhere to bankruptcy arrangements proposed, or to recover them through legal actions. At the same time, organisations belonging to the textiles industry felt the necessity to protect the industry’s reputation, restoring internal equilibrium (Balleisen Citation2009).

A key factor in the decision process of each organisation was represented by the analysis of the journal entries and financial statements of bankrupters. Due to the geographical distance, and considering the means and related costs, each organisation could not analyse the accounting books of every single proceeding that existed in the Italian Courts in which their credit rights were involved. The same was also the case for legal actions and for bankruptcy arrangements, where the ‘weight’ of the votes was based on the amount of credit rights, and a single member did not frequently have the power to exercise a significant vote.

For these reasons, the Unione Commercianti in Manifatture di Milano was created. As also highlighted in previous studies on industry self-regulatory institutions (Yue, Luo, and Ingram Citation2009; Yue and Ingram Citation2012), the function of the Union can be broken down into two categories, credit rights protection and regulation. To fulfil the credit rights protection function, the Union provided centralised services for its members, inspecting accounting books and financial statements, jointly exercising members voting rights in bankruptcy arrangements and promoting unitary legal actions. To fulfil the regulatory function, the Articles of Incorporation foresaw stringent rules and obligations to avoid opportunistic behaviours, which restricted the initiatives each member could take, such as unfair agreements with bankrupters. In this way, the Union was able to acquire a central role in trade that allowed it to exercise a ‘deterrent’ function against the malpractices which were widespread in Italy, facilitating the process of building a solid reputation in the textile industry. This distinction emerged also in the words of some members of the Union:

the arrival of the Unione Commercianti in Manifatture has brought about a real improvement in the settlement of bankruptcy proceedings, both from a percentage point of view and from the no less important viewpoint of speed of settlement. This leads not only to material interest in the membership, as well as a morally improved trading environment, demonstrated by the reduction in the number and size of frauds, in response to one of the principals aims of the Union.Footnote 27

According to institutional theory, for each organisation the analysis of accounting books represented an institutional mechanism for arbitrating, a tool to evaluate whether or not to accept a bankruptcy arrangement, or to try to recover credit rights with legal actions (Tinker Citation1985; Carmona, Ezzamel, and Gutiérrez Citation2006). Considering the difficulty for organisations to arbitrate, the need to acquire and analyse the financial information of customers involved in bankruptcy proceedings represented a key factor for the birth of the Union.

In addition, after the creation of the Union, when it operated, the need to analyse accounting books pushed non-member organisations to adhere to it, influencing their behaviour. According to institutional isomorphic change theory (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983), members’ behaviour can be influenced through mimetic forces, without sanctions. In particular, taking the social learning view, an organisation can evaluate the outcomes of peers and take advantage of information regarding their earlier decisions. To this end, an organisation will only imitate when the outcomes for peers will be more advantageous and more feasible for itself (Kraatz Citation1998). In this sense, as pointed out by the Director of the Union (Prof. Rag. Ottorino Ponti) in 1901:

In the field of large-scale trade in manufactured goods its utility is recognised without discussion. Even the few entrepreneurs who looked at it with suspicion at the start, now openly acknowledge the advantages, adding that ‘If the Union did not exist, we would need to create it’. New and numerous applications for membership therefore arrived, against all our predictions, which made us persuaded the previous year (1899) that we had reached the maximum possible number of members. We were pleased to see a steady increase, a sign of prosperous youth.Footnote 28

But what gives us greater satisfaction is to inform you that some members, who last year had submitted their resignations, believing they can protect their interests on their own, after the experiment of only one year, they ran to re-apply the admission into Union. This fact, awaited by us, is the most convincing proof that, united we win, divided we succumb.Footnote 29

If, observing the largest and more influent textiles manufacturers, certain organisations decided to join the Union according to a status-driven imitation mechanism, new members were mainly attracted by the results achieved by the Union. As reported in the journal, the Legal and Accounting Office conducted ‘accounting and legal autopsies’ in the most significant proceedings. The ability to evaluate bankruptcy proceedings through the examination of accounting books, investigating the causes of cessation of payments, as well as checking if liabilities were overstated and assets hidden or understated, represented the main reason to join the Union.

In this sense, also during the trial period of 18 months, without sanctions, only a very few members violated rules stated by the Union; in most cases, violations resulted from misunderstandings in interpreting the Articles of Incorporation.Footnote 30 Due to the cohesion of its members, mainly ensured by the aforementioned mimetic forces, the Union was thus able to generate direct advantages for each of them and, at the same time, be effective in preserving industry reputation.

As evidence of the relevance of the activity carried out by the Union, it is worth noticing the role that the Legal and Accounting Office played also for other associations operating in different industries. As highlighted by the Director of the Union (Prof. Rag. Ottorino Ponti) in 1901:

A new Union [‘Leather manufacturers and wholesalers’] asked us to form a section of our Legal and Accounting office … , assuming the same obligations as our members, regarding the participation in the expenses related to the administration of the association and to the protection of their respective interests.Footnote 31

This point highlights another key insight that emerged in the study. As outlined, the process of selection of bankruptcy Trustees in the Kingdom of Italy at the end of nineteenth century was characterised by ‘a strange mixture of people, of studies, of activities, of social conditions, very disparate’ (Vianello Citation1894, 4). Considering the relevance of the activity carried out by the Legal and Accounting Office, also in industries different from the textiles ones, it demonstrates clearly the contribution to the improvement of bankruptcy proceedings management, with particular reference to accounting professions, favouring and promoting its professionalisation (Walker Citation2004).

This study presents multiple limitations. First, the development of a single case study makes it difficult to generalise the results obtained. Second, we do not have a counter-case that may provide a broader comprehension of the role of accounting in industry self-regulatory institutions. Third, the analysis is focused on activities carried out by the Union over a period of only five years, between 1898 and 1902, as reported in the institution’s journal.

Finally, the objective of this research has been to explore the role that accounting can play in the creation and the functioning of an industry self-regulatory institution. The development of the case highlights a clear and key role of the analysis of accounting books as an arbitrating mechanism, at the base of the creation of this type of institution. In addition, our analysis illustrates that accounting could constitute a mimetic force able to attract new members and to maintain their cohesion, ensuring the effectiveness of the self-regulatory institution.

Acknowledgements

An early draft of this paper benefitted from discussion at the Accounting History Review Conference 2019 held in Ormskirk, 10–11 September 2019. We acknowledge the comments on the conference paper offered by Professor Tonya Kay Flesher. We are also grateful to Professor Cheryl Susan McWatters for her accurate and patient guidance and to two anonymous reviewers for constructive and helpful comments. We alone remain responsible for the final content.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Almost all the major banks were in trouble. The insolvency of the Banca Romana was accompanied by the collapse of a large part of the Italian banking system. The Banca Tiberina, the Banco Sconto e Sete, the Banca di Milano and the Banca Napoletana were forced out of business. It was the same was for the Banca Generale in 1894. The Società Generale di Credito Mobiliare was also forced to close down (Clough Citation1965).

2 These included: Enrico Dell’acqua (from Busto Arsizio) who, in 1898, could count on hundreds of agencies and/or branch offices in Latin America; the Rossi family (from Schio) operating in the production and trading of wools, who employed 5000 workers in the same year; Costanzo Cantoni (from Gallarate) the leading producer and distributor of cotton products in Italy.

3 ‘Alla severa moralità del commercio probo, regolato, leale in tutti i suoi impegni, curante sopratutto della sua onoratezza e del suo buon nome, sono succedute condizioni purtroppo molto diverse che vanno sempre più allargandosi. (…) Sono cose che tutti conoscono: imprese che si impiantano senza capitali, ovvero con debiti; vita commerciale condotta spensieratamente, largamente, alle spalle degli incauti e degli ingannati; alterazioni, sofisticazioni di merci all'ordine del giorno; liti per risolvere contratti, nelle quali non c'è altro motivo di scioglimento che il rialzo o il ribasso della merce. Finalmente dopo una lunga serie di simulazioni e di frodi il fallimento, presentato nel vuoto e a zero’, Federici Citation1899, 104–105.

4 The article shows the results of the Report drawn up by the judge Penserini and presented to the ‘Commission for judicial and notarial statistics’ in January 1904. In particular, it highlights that ‘Bankruptcies declared in this period reached a total of 7912, an average of 2637 per year. As regards the number and size of the bankruptcies most are in areas with large towns and cities and, particularly those with greatest concentration of industry and trade: Genoa, Turin, Milan in northern Italy, Florence and Rome in central Italy, Naples and Puglia in the south, Palermo and Catania in Sicily.’ [‘I fallimenti dichiarati in questo periodo ascesero alla cifra di 7912, quindi a una media di 2637 per anno (…). Quanto al numero ed alla entità dei fallimenti (…) prevalgono quei distretti nei quali vi hanno grossi centri e, tra questi, quelli dove maggiori sono le industrie e i commerci: Genova, Torino, Milano nell’Italia settentrionale, Firenze e Roma nella centrale, Napoli e le Puglie nella meridionale, Palermo e Catania in Sicilia.’], Penserini Citation1904, 425.

5 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 9-10, 1-2.

6 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1901, n. 1, 3.

7 ‘Fatta eccezione per Milano e per Genova … c’è di tutto. C’è il ragioniere, l’avvocato, il geometra, il medico, il giovane di notaio, il negoziante persino fallito … . C’è, in una parola, una strana miscela di persone di studii, d’attività, di condizione sociale, disparatissime’, Vianello Citation1894, 4.

8 ‘non sempre viene liquidata giudizialmente per mancanza della domanda, ciò che, secondo le relazioni dei capi dei Tribunali accade pur troppo per convenzioni, non scevre di sospetto, tra curatore e fallito nei fallimenti chiusi per concordato’, Penserini Citation1904, 427.

9 ‘è un fatto positivo che i curatori in quasi tutti i fallimenti fanno e disfanno ciò che loro meglio talenta’, Penserini Citation1904, 427.

10 ‘(…) combattere la speculazione del fallimento, le viziate procedure; ricondurre l’istituto della Curatela alla sua vera funzione di rigido amministratore dei beni della massa; troncare l’ingerenza di molti affaristi che fanno professione di suggerire al fallito i mezzi coi quali egli può ingannare i creditori e la legge e speculare sul suo fallimento; (…) provvedere affinché le merci dei fallimenti non fossero cedute o vendute a parenti e compari del fallito od a vilissimo prezzo, con ischerno della morale e grave danno dell’onesto commercio’, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1901, n. 1, 1.

11 ‘1° di efficacemente proteggere i crediti dei proprii soci compromessi in procedure giudiziali di fallimento e moratoria e in quelle stragiudiziali di dissesto; di ottenere loro una eguale percentuale di realizzo, esplicando una unica energica azione; 2° di impedire che i diritti dei proprii soci vengano pregiudicati dai debitori insolventi con false denunzie di passività, con occultazioni di attività e mediante altri atti fraudolenti e commercialmente riprovevoli; 3° di attivare e appoggiare tutte quelle pratiche atte a favorire lo sviluppo e il commercio delle manifatture e specialmente dirette ad ottenere dei miglioramenti nella nostra legislazione commerciale’, Il Giornale dell'Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1902, n. 1, 3.

12 ‘Biographical Dictionary of Italian – Treccani’, entry ‘Marzotto’, available at https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marzotto_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/ accessed on 28 November 2021.

13 ‘Sarà cura del Direttore e de’ suoi sostituti d’ispezionare i libri del debitore per constatarne la regolarità, esaminare il bilancio, prendere nota dell’attivo e del passivo, del nome, cognome e residenza dei singoli Creditori, indagare le cause della cessazione dei pagamenti, verificare se essa sia l’effetto della malafede e se nel bilancio non vi siano compresi debiti finti o simulati, sempre quando ciò sia possibile. In sede specialmente di moratoria sarà loro cura di esaminare se realmente vi concorrono gli estremi voluti dalla legge’, paragraph 29 of the Articles of Incorporation.

14 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 4, 1.

15 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1901, n. 1, 3.

16 ‘perché costosissime e d’esito sovente subordinato a calcoli di maggioranze, che solo una unione solidale di creditori può computare e dimostrare con sicurezza’, Report by the Executive Committee on December 1899, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 13-14, p. 2.

17 ‘Tante giurisprudenze quanti Tribunali, tante procedure quante Cancellerie’, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1900, 4, p. 1.

18 ‘una norma unica, precisa nelle procedure fallimentari, dove è più che altrove utile che i Giudici delegati si sveglino e seguano, ancor loro le fasi del fallimento, in modo di potere con cognizione di causa riferirne al Tribunale, e non s’adagino sui rapporti dei Curatori, spesso non all’altezza delle mansioni loro affidate’, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1900, n. 4, 1.

19 ‘a cui sembra non importi che gli interessi dei creditori vengano calpestati e vilipesi, pur che si salvi il fallito, vittima sacrata delle cupidigie creditorie!’, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1900, n. 4, 1.

20 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1901, n. 1, 1.

21 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 5-6, 1.

22 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 8, 1.

23 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 9-10, 4-5.

24 The legitimacy of the precepts included in the Articles of Incorporation of the Union, moreover, gave rise to a lively debate among the most authoritative Italian jurists of the age. This debate contributed to spreading knowledge about the Union's activities and to increasing its popularity (Carretti Citation1899; Sraffa Citation1904,Citation1905; Ascoli Citation1905a; Bonelli Citation1905).

25 ‘prendere da sé alcun provvedimento o disposizione riguardo alla tutela e realizzo del proprio credito, cederlo ad altri, accettare concordati giudiziali e stragiudiziali, stipulare sotto qualsiasi forma accordi con il fallito, morato, dissestato o terzi, iniziare o continuare azioni giudiziali’, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1902, n. 1, 7.

26 ‘è reso quasi impossibile che alcuno degli aderenti tenti di sottrarsi agli obblighi assunti, principalmente perché chi interviene in simili convenzioni sa che l’importanza di queste sta nell’essere a tratto successivo e tiene a non essere squalificato dai coassociati ed escluso dall’associazione per l’avvenire’, (Sraffa Citation1904, 431).

27 ‘l’avvento dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture ha portato un reale miglioramento nella risoluzione dei dissesti, sia dal punto di vista delle percentuali che dall’altro non meno importante del sollecito disbrigo. Da ciò, oltre che l’interesse materiale per i Soci, deriva quella miglior tinta della moralità commerciale, che si esplica appunto con la diminuzione, e per numero e per entità, delle frodi, e rispondere ad uno dei principali scopi dell’Unione stessa’, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 9-10, 4.

28 ‘nel campo del grande commercio, delle manifatture, l’utilità sua si riconosce senza più discuterla. Quegli stessi (…) che dapprima la riguardavano con occhio sospettoso, oggi ne confessano apertamente in vantaggi, soggiungendo che ‘se l’unione non fosse, bisognerebbe costituirla. Nuove, numerose domande d’iscrizione a socio giunsero pertanto, e contro ogni nostra previsione, che ci faceva persuasi avere l’anno antecedente 1899 raggiunto in fatto di soci il massimo numero possibile, noi fummo lieti di constatare ancora nel decorso del 1900 un continuato progressivo aumento, indice sicuro di giovinezza prosperosa.’, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1901, n. 1, 1.

29 ‘Ma ciò che torna a nostra maggiore soddisfazione si è il comunicarvi, che alcuni soci, i quali nello scorso anno avevano presentato le loro dimissioni, credendo di potere da soli meglio tutelare i loro interessi, dopo l’esperimento di un solo unico anno, sono corsi a ridomandare l’ammissione nella Società. Questo fatto, da noi atteso, è la prova più convincente che, uniti si vince, divisi si soccombe.’, Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1901, n. 1, 2.

30 Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1899, n. 11-12, 1-2.

31 ‘La nuova Unione [manifatturieri e grossisti di pellami] ci ha chiesto di formare una nostra sezione del nostro studio direttivo (…), assumendo gli stessi obblighi dei nostri soci, in riguardo alla partecipazione delle spese inerenti all’amministrazione dell'associazione ed alla tutela dei rispettivi interessi.’ Il Giornale dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture, 1901, n. 1, 2.

References

- The 1882 Italian Commercial Code.

- The Italian Law n.197/1903 (‘Reform of Moratorium and Introduction of Pre-Bankruptcy Arrangements’).

- Unione dei Commercianti in Manifatture. 1899–1902. Il Giornale Dell’Unione Commercianti in Manifatture .Milano:Tipografia P. Agnelli.1–143.

- Abrahamson,E. , and L. Rosenkopf .1993. “Institutional and Competitive Bandwagons: Using Mathematical Modeling as a Tool to Explore Innovation Diffusion.” Academy of Management Review 18:487–517.

- Alpa,G. 2007. “Le « Code de Commerce » et L’Italie : Quelques Réflexions sur L’histoire et les Perspectives du Droit Commercial.” Revue Internationale de Droit Comparé 59 (2):235–257.

- Ascoli,A. 1905a. “Ancora a Proposito di Nuove Forme Contrattuali.” Rivista di Diritto Commerciale, Industriale e Marittimo 3 (1):44–49.

- Ascoli,A. 1905b. “Ancora a Proposito di Nuove Forme Contrattuali.” Rivista di Diritto Commerciale, Industriale e Marittimo 3 (1):144–146.

- Avagliano,L. 1977. “Un Imprenditore e una Fabbrica Fuori dal Comune: Alessandro Rossi e il Lanificio di Schio.” In In L’industrializzazione in Italia (1861-1900) , edited by G. Mori ,333–345.Bologna:il Mulino.

- Balleisen,E. J. 2009. “Private Cops on the Fraud Beat: The Limits of American Business Self-Regulation, 1895-1932.” Business History Review 83 (1):113–160.

- Barnett,M. L. , and A. A. King .2008. “Good Fences Make Good Neighbors: A Longitudinal Analysis of an Industry Self-Regulatory Institution.” Academy of Management Journal 51 (6):1150–1170.

- Bolaffio,L. 1903. La Legge sul Concordato Preventivo e Sulla Procedura dei Piccoli Fallimenti: Testo, Lavori Preparatori, Commento .Verona:Tedeschi.

- Bonelli,G. 1905. “Ancora a Proposito di Nuove Forme Contrattuali.” Rivista di Diritto Commerciale, Industriale e Marittimo 3 (1):142–144.

- Cafagna,L. 1977. “La Rivoluzione Industriale in Italia, 1830-1900.” In L’industrializzazione in Italia (1861-1900) , edited by G. Mori ,91–105.Bologna:il Mulino.

- Caizzi,B. 1965. Storia Dell’industria Italiana. Dal XVIII Secolo ai Giorni Nostri .Torino:Editrice Torinese.

- Cardini,A. 1981. Stato Liberale e Protezionismo in Italia (1890-1900) .Bologna:Il Mulino.

- Carmona,S. , M. Ezzamel , and F. Gutiérrez .2006. “Accounting History Research: Traditional and New Accounting History Perspectives.” De Computis - Revista Española de Historia de la Contabilidad 1 (1):24–53.

- Carretti,G. 1899. “A Proposito Della Unione Commercianti in Manifatture.” Il Ragioniere. L’avvenire Della Ragioneria 5 (2):24.

- Castronovo,V. 1980. L’industria Italiana Dall’ottocento a Oggi .Mondadori Editore:Milano.

- Castronovo,V. 1977. “Formazione e Sviluppo del Ceto Imprenditoriale Piemontese nel Secolo XIX.” In L’industrializzazione in Italia (1861-1900) , edited by G. Mori ,183–199.Bologna:il Mulino.

- Catalfo,P. , G. Barresi , and C. Marisca .2015. “Lo Stato di Avanzamento Della Contabilità Pubblica nel Regno Delle Due Sicilie Nella Prospettiva Culturale di Francesco Dias "Uffiziale di Carico nel Real Ministero di Stato Delle Finanze".” Contabilità E Cultura Aziendale 15 (2):7–26.

- Clough,S. B. 1965. Storia Dell’Economia Italiana dal 1861 ad Oggi .Bologna:Cappelli Editore.

- Chandler,R. 2019. “Auditing and Corporate Governance in Nineteenth Century Britain: The Model of the Kingston Cotton Mill.” Accounting History Review 29 (2):269–286.

- Confalonieri,A. 1974. Banca e industria in Italia 1894-1906. Volume 1, Le premesse: Dall’abolizione del corso forzoso alla caduta del Credito Mobiliare .Milano:Banca Commerciale Italiana.

- Corbino,E. 1962. L’Economia Italiana dal 1860 al 1960 .Bologna:Zanichelli Editore.

- Covaleski,M. , and M. Aiken .1986. “Accounting and Theories of Organizations: Some Preliminary Considerations.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 11 (4-5):297–319.

- Della Peruta,F. , and E. Cantarella .2005. Bibliografia dei Periodici Economici Lombardi 1815-1914 .Milano:Franco Angeli.

- DiMaggio,P. J. , and W. W. Powell .1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (8):147–160.

- DiMaggio,P. , and W. Powell .1991. The new Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis .Chicago:University of Chicago Press.

- Di Martino,P. , and M. Vasta .2010. “Companies' Insolvency and ‘the Nature of the Firm’ in Italy, 1920s-70s1 .” The Economic History Review 63 (1):137–164.

- Di Martino,P. 2005. “Approaching Disaster: Personal Bankruptcy Legislation in Italy and England, c.1880–1939.” Business History 47 (1):23–43.

- Einaudi,L. 1900. Un Principe Mercante: Studio Sulla Espansione Coloniale Italiana .Torino:Bocca.

- Federici,E. 1899. Atti del Congresso Internazionale per L’insegnamento Commerciale Tenuto a Venezia dal 4 all’8 Maggio 1899 .Venezia:Stab. Tipo-litografico di Carlo Ferrari.102–106.

- Gervais,P. 2008. “Neither Imperial, nor Atlantic: A Merchant Perspective on International Trade in the Eighteenth Century.” History of European Ideas 34 (4):465–473.

- Gorton,G. , and D. J. Mullineaux .1987. “The Joint Production of Confidence: Endogenous Regulation and Nineteenth Century Commercial-bank Clearinghouses.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 19 (4):457–468.

- Grief,A. 1997. “Microtheory and Recent Developments in the Study of Economic Institutions Through Economic History.” In Advances in Economic Theory and Econometrics , edited by D. Kreps , and K. Wallis ,79–113.Chicago:Cambridge University Press.

- Gunningham,N. , and J. Rees .1997. “Industry Self-Regulation: An Institutional Perspective.” Law & Policy 19 (4):363–414.

- Haunschild,P. R. 1993. “Interorganizational Imitation: The Impact of Interlocks on Corporate Acquisition Activity.” Administrative Science Quarterly 38 (4):564–592.

- Hautcœur,P. C. , and P. Di Martino .2013. “The Functioning of Bankruptcy Law and Practices in European Perspective (ca.1880–1913).” Enterprise and Society 14 (3):579–605.