ABSTRACT

Background: Low-fat and low-sugar foods, marketed as health promoters, offer an interesting avenue for consumers to pursue a healthier life. Despite the relevance of educating adolescents about the importance of a healthier lifestyle, even today little attention is paid to this issue. The aim of this paper is to analyse adolescent consumers with varying degrees of a healthy lifestyle and different healthy eating perceptions and the relationship with their body mass index (BMI) and their low-fat and low-sugar food consumption. Methods: With a sample of 590 (353 from public schools and 237 from private schools) young consumers (13–17 years old) and SSS statistical tools, some interesting results are obtained. Results: Data obtained confirm the relationships among healthy life style activities and BMI and low food consumption. Also, data show interesting relationships among healthy eating perceptions and BMI and low food intake. Conclusions: The empirical results and findings from this study would be valuable for marketers and administration in the food industry to formulate marketing communication strategies and to promote a healthier lifestyle and eating perceptions among adolescents.

1. Introduction

During the last two decades, there have been significant changes in food choices and consumption. According to Gil et al. (Citation2000), food consumption in most developed countries has reached a saturation point in quantitative terms, and consumer food choices are broader than in the past. In this saturated market situation, marketing activities and food quality are becoming increasingly important. In addition, consumers have become more concerned about the nutrition, healthiness and quality of the food that they eat (Gil et al. Citation2000). Food consumers have moved up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pyramid from satisfying basic physiological needs (Senauer Citation2001). Today, attention increasingly needs to be paid to the demand for quality-differentiated food products. Many consumers look for foods that are not only safe, but also positively promote good health. Thus, as Chen (Citation2011) states, health is one of the often-declared motivations when consumers make their food choices. At the same time, the household or family is no longer the key decision-making unit in terms of food consumption in most cases (Senauer Citation2001).

Among countries at an intermediate level of development (middle-income countries, with a per capita gross national product (GNP) of about $3000 per year), overweight ranks fifth among the top 10 causes of disease burden – immediately below underweight (Caballero Citation2005). Since the 1980s, the prevalence of obesity in children has risen greatly worldwide, with consequent growth of serious problems. In this sense, studies indicate the importance of developing healthy eating habits among people at a young age (Chan et al. Citation2011). As Ebbeling et al. (Citation2002) state, this growth can be attributed primarily to adverse environmental factors.

In this context, and as worldpress.com (Citation2011) reports, according to a study by consultancy firm Deloitte, 6% of consumers are more concerned about their food today than they were 5 years ago, especially regarding the preparation of food. One of the main concerns when purchasing a certain product is its development with healthy ingredients – a priority for 61% of consumers – and the potential use of chemicals in their manufacturing. In addition, the article points out that currently around 300 foods with healthy properties are sold in Spain. Furthermore, 60% of Spanish households have tried a food with claims of health benefits.

The pace of life and changes in food worldwide have caused various ailments, including thinness, overweight and obesity. The latter is a chronic disease with many complications and origins and is characterized by excess body fat (Berthoud, Citation2011). One of the causes of obesity and overweight is the tendency to consume high-calorie foods that are rich in sugars and saturated fats or hydrogenated oils, combined with poor fibre intake (World Health Organization, Citation2012). The World Health Organization (Citation2012) states that that 65% of the world’s population live in countries where overweight and obesity kills more people than underweight. In addition, in 2010, about 40 million children under 5 were overweight. Together with obesity problems, in the last decades, underweight diseases have increased in most developed countries, and Spain is no exception. The studies by Alvarez et al. (Citation2011) and Martínez-Vizcaíno et al. (Citation2012) point out that schoolchildren suffer with weight problems.

Most worrying is that it is no longer a disease that affects only adults; the impact of the parents’ lifestyle also affects the health of their children. Here lies the interest of this article: to analyse the adolescent segment, because, as Chan et al. (Citation2011) state, while some issues related to healthy lifestyles or healthy eating perceptions have been researched in the context of younger children, similar studies on adolescents have not been undertaken. This appears to be a relevant field for research, since adolescents are more often away from home and the watchful eyes of their parents (Chan et al. Citation2011).

Therefore, and because it is well known that adolescents have particular food choices and meal habits compared with younger children and adults (Moreno et al. Citation2008), this study focuses on the adolescent segment, analysing its healthy lifestyle and healthy eating perceptions. At the same time, the study of these two concepts (healthy lifestyle and healthy eating perceptions among adolescents) will be related to other concepts: the BMI and low-fat and low-sugar food consumption.

Due to the concern about obesity and socio-cultural changes, more research on low-fat foods and sugars is being developed. Along with this, a growing concern is caused by the problems of thinness detected at increasingly younger ages. Since the 1950s there has been evidence of the relationship between diet and health, and this causes health to be one of the most commonly cited reasons for dietary changes for most Europeans (Lappalainen et al. Citation1998). In addition, health is seen as a consequence of individual behaviour rather than the result of factors external to the person; thus, for many consumers, health is a determining factor in their eating habits (Thompson & Moughan Citation2008).

In this context, some food manufacturers, concerned about the welfare of consumers, have begun to launch campaigns that encourage proper nutrition, having developed awareness of the beneficial effect of increased physical activity. However, it is necessary for the food industry to engage in more actions and campaigns to introduce innovative, healthy and nutritious alternatives in addition to reformulating the existing products. In this context, food companies should take care to offer consumers healthy alternatives that can help to reduce the adverse effects of overweight and obesity and to raise awareness through marketing campaigns to consumers that eating fat/sugar replacement products does not mean they should increase the level of intake of these products. By contrast, the main objective is to convince consumers of the need to reduce their consumption of fat/sugar to improve their quality of life. However, together with this, it is necessary to underline the importance of a balanced diet, with no problems of obesity or thinness.

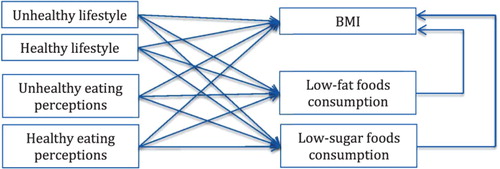

In sum, as weight problems have become a serious concern globally, there has been an increase in research on ways to encourage the adoption of a healthy eating lifestyle (Chan et al. Citation2011). Furthermore, as Moreno et al. (Citation2008) state, there is a need to gain a better understanding of consumer requirements and preferences and to provide a healthy, safe and high-quality food supply – in this case, specifically for adolescents. In this sense, and according to Chen (Citation2011), it is of interest and significance to investigate whether or not local consumers with varying degrees of health consciousness and dissimilar healthy lifestyles will have different attitudes toward functional foods and will vary in their willingness to use them. Thus, the main objective of this study is to investigate whether or not a healthy lifestyle and healthy eating perceptions among teenagers can have an impact on three food intakes: (i) BMI; (ii) low-fat foods; and (iii) low-sugar foods. To achieve this objective, the influences of teenagers’ BMI on their consumption of low-fat and low-sugar foods will be examined first. Second, this study will investigate the impacts of teenagers’ healthy/unhealthy lifestyles on their consumption of low-fat and low-sugar foods. Finally, the paper will examine the impact of low-fat and low-sugar food consumption on teenagers’ BMI. The above-mentioned research framework of this study is depicted in Figure (Hypothesis 1–5). The findings are hoped to provide some suggestions to marketers in the low-fat and low-sugar foods industry to formulate marketing communication strategies and facilitate this industry’s development.

2. Low-fat and low-sugar food consumption in children: healthy lifestyle and healthy eating perceptions

As obesity and thinness, along with unhealthy eating, have become increasingly serious problems globally, in recent times there has been an increase in research studying ways to encourage the adoption of a healthy eating lifestyle. Although this effort, literature finds low levels of nutrition knowledge, not only in adolescents but also in their home environments (i.e. Castillo et al. Citation2015; Tabbakh & Freeland-Graves Citation2016). In this sense, ‘a significant increase in basic nutrition education needs to occur in order to increase the understanding of what is a“healthy” diet’ (Castillo et al. Citation2015, p. 11).

The marketing of unhealthy foods to children and youths has been identified as the major source of impact on consumers’ choice of unhealthy foods (Kline, Citation2011). However, how can healthy and unhealthy foods be defined? As Provencher et al. (Citation2009) state, previous studies show that foods can be (and often are) categorized as healthy or unhealthy according to several factors, such as their perceived fat and/or sugar content.

On this line, researchers agree that the chronic disease morbidity and mortality today are strongly associated with behaviours, or factors influenced by behaviours, which may be characterized as modifiable, lifestyle-related health risk factors (Tabbakh & Freeland-Graves Citation2016). Such individual-level health risk factors include the use of tobacco, sedentary behaviour and low levels of physical activity and less an optimal body weight for health, low multifactorial diet-quality practices and excess consumption of alcohol (Pronk et al. Citation2004). The reason can be found in the fact that, over the past few decades, food and home environments have changed tremendously. As St-Onge et al. (Citation2003) report, the environmental factors that affect eating behaviours comprise the changing nature of the food supply; increased dependence on foods consumed away from home; food promotion and marketing; and food prices. In addition, there are more families in which both parents work, and time limitations have become an important factor in determining the types of foods consumed. The food industry has responded to these new family issues by increasing the numbers of convenience foods and prepared meals available. As a result, the per capita availability of added sugars and fats has increased over the past two decades (St-Onge et al. Citation2003).

According to Urala and Lähteenmäki (Citation2004) and Chen (Citation2011), human food choice is a function of numerous influences. In general terms, it can be stated that the mechanisms of low-fat and low-sugar food choice are similar to the choice of conventional food products, even though there may be differences in the perceptions of the perceived benefit of eating these non-conventional foods (Urala & Lähteenmäki Citation2004).

Thus, and as stated before, the interest of this paper concerns healthy lifestyles and healthy eating perceptions among adolescents and their relationship with possible weight problems and some food choices.

2.1. BMI and low-fat and low-sugar food consumption

According to Prentice and Jebb (Citation1995), underweight and overweight problems can be explained by both genetic and familial associations, suggesting an element of individual susceptibility that interacts with adverse environmental conditions to cause extreme weight gain or loss. As the authors show, recent epidemiological studies on obesity/thinness indicate, however, that the primary causes of the problem must lie in environmental or behavioural changes affecting large sections of the population.

In any case, and as Vermunt et al. (Citation2003) and Oldewage-Theron et al. (Citation2015) state, an accurate energy balance (energy intake equals energy expenditure) is essential to maintain a stable body weight. Under this premise, it has been suggested that foods, and diets, that combine high levels of sugars and fat particularly contribute to overconsumption (Gibson Citation1996), affecting the BMI of individuals. Not in vain, in weight reduction programmes, dietary recommendations have been mainly focused on reducing the intake of fat and sugar (Vermunt et al. Citation2003).

In this scenario, the intake of low-fat and low-sugar food can help to control weight (Tabbakh & Freeland-Graves Citation2016). The study by Gibson (Citation1996), with 1087 males and 1110 females aged 16–64, shows that the intake of the main sugary and fatty foods (as a proportion of the total energy) is inversely related to the BMI (adjusted for age and smoking).

Neovius and Rasmussen (Citation2008) demonstrate a highly significant weight loss of 3–4 kg in normal-weight and overweight subjects in four meta-analyses of weight change undertaken on ad libitum low-fat diets in intervention trials. The analyses also found that a reduction in the percentage of energy as fat is positively associated with weight loss. A 10% reduction in dietary fat is predicted to produce 4–5 kg of weight loss in an individual with a BMI of 30 kg/m2. In sum, their evidence strongly supports the low-fat diet as the optimal choice for the prevention of weight gain and obesity, while the use of a normal-fat high-monounsaturated fatty acid diet is unsubstantiated.

Therefore, and in view of the discussion on previous lines, according to Rudd (Citation2007), a relationship emerges between adolescent consumers’ BMI and their intake of (a) low-fat foods and (b) low-sugar foods.

H1: The intake of (a) low-fat food and (b) low-sugar food affects consumers’ BMI.

2.2. Healthy lifestyle, BMI and low-fat and low-sugar food consumption

Nowadays, lifestyle factors are applied to describe how consumers make good decisions (Senauer, Citation2001). The lifestyle construct has a longstanding history in marketing research, and it has been argued that a person’s lifestyle need not be consistent across different life domains and should be restricted to certain life domains (van Raaij and Verhallen, Citation1994).

Among the diverse definitions of lifestyle, we focus on that proposed based on health-related behaviour, named healthy lifestyle (Gil et al. Citation2000). Following Grimaldo (Citation2010), the term healthy lifestyle is used to denote a general way of life based on the interaction between the living conditions in the broadest sense and the individual patterns of behaviour determined by socio-cultural factors and personal characteristics. Thus, this research will address a healthy lifestyle as a set of behaviours determined socio-culturally and learned in the process of socialization that can contribute to the promotion and protection of the overall health of a person. This healthy lifestyle considers the following areas: sports, food consumption, and sleep and rest. In sum, this definition underlines physical health-related activities, like natural food consumption, health care and life equilibrium (Gil et al. Citation2000). The food consumption area is not considered in the measurement but is given its own attention. The reason is that the goal of this study focuses on low-fat and low-sugar food consumption.

In this sense, related to the healthy lifestyle, and according to Chen (Citation2011), the idea that one’s lifestyle will affect one’s longevity has become firmly ingrained in the Western belief system. If a person lives a life characterized by high fat consumption, high stress levels, a lack of exercise and a poor social support network, he/she will easily suffer from health problems (Chen Citation2011). Among these problems, we can find the overweight and underweight situations. The literature offers diverse studies that support this statement. For example, the work by Glanz et al. (Citation1998) shows how consumers’ healthy lifestyle could affect their weight. On the same line, Prentice and Jebb (Citation1995) find that lifestyle can play an important role in the development of weight problems. Their study in Britain concludes that that the low levels of physical activity now prevalent in Britain are playing a relevant, perhaps dominant, role in the development of obesity by greatly reducing people’s energy needs.

More specifically, Chaput et al. (Citation2006) find a relationship between short sleeping hours and childhood overweight/obesity, in a sample consisting of a total of 422 children (211 boys and 211 girls) aged between 5 and 10 years from primary schools in the city of Trois-Rivières (Québec). The authors observe an inverse association of sleep duration and the risk of developing childhood overweight/obesity. On the same line, Prentice and Jebb (Citation1995) and Hallal et al. (Citation2006) undertake a literature review to probe, among other aspects, whether adolescent physical activity influences an adequate BMI and food choices. The study by Prentice and Jebb (Citation1995), based on different dietary and activity data, shows once again a much closer relation between obesity and measures of inactivity than between obesity and diet.

On other hand, and due to increasing disposable incomes and busy lifestyles, people are changing their dietary habits to maintain or improve their health, and functional foods open a promising avenue for consumers to pursue a healthier life (Chen Citation2011). In this sense, previous studies investigate whether consumers’ lifestyle can affect their consumption of some functional products (for example, Urala & Lähteenmäki Citation2004 or Verbeke Citation2005), and these conclusions can be extended to low-fat and low-sugar foods. As Chen (Citation2011) points out, if a person has a higher degree of health consciousness, then he or she is more willing to engage in those activities that are directly related to health, such as consuming natural foods, maintaining good health and living a balanced life (i.e. attentive to a healthy lifestyle). In contrast, we cannot expect those people who have a low degree of health consciousness to lead a healthy lifestyle. In other words, those consumers who are never concerned about their own health often engage in few activities related to a healthy lifestyle. Consequently, they show little interest in the healthiness of their food choices, health maintenance and a balanced life. These statements are in line with Ridder et al. (Citation2010), in a focus group with 37 adolescents in three schools in The Netherlands. The authors found that adolescents find health and a healthy weight important and like having a choice when it comes to health behaviour, but the selections they make, however, are often unhealthy, especially when related to food.

Based on above lines, and according to previous works (i.e. Grosso et al. Citation2013), the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a: When adolescent consumers have an unhealthier lifestyle, they show more overweight or underweight problems (inadequate BMI).

H2b: When adolescent consumers have a healthier lifestyle, they show a more adequate BMI.

H3a: When adolescent consumers have an unhealthier lifestyle, their consumption of (1) low- fat foods and (2) low-sugar foods will decrease.

H3b: When adolescent consumers have a healthier lifestyle, their consumption of (1) low-fat foods and (2) low-sugar foods will increase.

2.3. Healthy eating perceptions, BMI and low-fat and low-sugar food consumption

As Paquette (Citation2005) states, perceptions of healthy eating can be considered as one of the many factors influencing people’s eating habits. In this sense, and according to Chen (Citation2011), previous studies indicate that, together with lifestyle factors, consumers’ perceptions strongly affect the intention to eat some foods. In this sense, and in agreement with the World Health Organization (Citation2007), healthy eating can be defined as the eating behaviours that can enable the person to accomplish a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

In this sense, Chan et al. (Citation2011) conduct a literature review and conclude that the degree of healthy/unhealthy perceptions can affect the food that adolescents eat. In consequence, these perceptions can affect their body mass index (BMI). As the authors state, the empirical studies of perceptions of healthy eating find that perceptions of healthy eating are generally based on food choice, the characteristics of food and the healthy concepts held by the public. Following this argument, we can state that eating perceptions could be related to weight problems and food choice, as stated in the subsequent hypotheses.

Furthermore, as Chen (Citation2011) asserts, the literature demonstrates that perceptions about the healthiness of foods may bias estimations of the caloric content of foods. More specifically, when compared with the actual caloric content of the foods, healthy food choices are perceived as having a lower caloric content (underestimation), whereas unhealthy food choices are considered to have a higher caloric content (overestimation) (Chen Citation2011). In this sense, Moreno et al. (Citation2008) point out that there are many worries surrounding adolescent food choice behaviour, including the high intake of foods that are high in fat, sugar and salt. The reasons for these preferences and consumption patterns can range from innate food preferences and familiarity to social and environmental influences and perceptions. However, although many adolescents demonstrate awareness and knowledge of nutrition and healthy eating, they appear to find it difficult to put this theory into practice (Moreno et al. Citation2008).

On the same line, and as noted in previous research, Chan et al. (Citation2011) point out some empirical studies of perceptions of healthy eating that discover how perceptions of healthy eating are generally based on food choice. For example, the literature review by Paquette (Citation2005) reveals that adolescents consider the following in their healthy eating perceptions: (1) fruits and vegetables (which are consistently perceived as part of healthy eating), (2) naturalness and freshness, with low fat, sugar as well as salt contents (which are also important in the perceptions of healthy eating) and (3) meat, although its role in healthy eating is ambiguous. The authors conclude that these perceptions about healthy eating among consumers affect the foods that they eat.

Considering the preceding lines, we can establish a relationship between healthy eating perceptions and (1) weight problems and (2) low-fat and low-sugar food consumption among adolescents. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a: When adolescent consumers have unhealthier eating perceptions, they show more overweight or underweight problems (inadequate BMI).

H4b: When adolescent consumers have healthier eating perceptions, they show a more adequate BMI.

H5a: When adolescent consumers have unhealthier eating perceptions, their consumption of (1) low-fat foods and (2) low-sugar foods will be decreased.

H5b: When adolescent consumers have healthier eating perceptions, their consumption of (1) low-fat foods and (2) low-sugar foods will be increased.

3. Methodology

3.1. The population

The present study was carried out in Spain, a developed country in the south of the EU. Tables and show the main indicators for this country, offered by the World Health Organization (Citation2014). If we compare these data with those of other European countries (www.who.int/countries/en/), we can state that the spending on health is quite high.

Table 1. Main indicators in Spain.

Table 2. Spain health profile 2013.

More specifically, this study focuses on the segment of adolescents in a particular Spanish region: Valencia. In this sense, and following several authors, such as and Scully et al. (Citation2012), the teenage market includes young consumers aged between 13 and 18 years (between 8 and 12 they are still considered children). This market represents an interesting opportunity for packaged food manufacturers because their role as buying agents in the family unit is growing more and more (Haytko and Baker, 2004). Consequently, we selected this target for our work. At the same time, Valencia presents a similar profile to Spain (Fundación BBVA, Citation2008).

3.2. Information collection

Prior to the quantitative data gathering, a qualitative phase was undertaken based on seven experts’ opinions. They were young Spanish consumers. With their collaboration, the proposed questionnaire was reviewed and the scales purged. The sample for our work was defined following the study by Scully et al. (Citation2012). Our sampling procedure was a stratified two-stage probability design, with schools randomly selected at the first stage of sampling and classes selected within schools at the second stage. Schools were stratified by the two education sectors (government and private). That is, our sample was defined according to consumer profile quotas for a metropolitan statistical area representing the teenage market in Spain (sample error 4%; confidence level 95%; p = q = 0.5). Active parental consent was required for students to participate in each component of the study. It must be noticed that this research was carried out on in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and that approval to conduct the study was obtained from the public government of the studied metropolitan area and the school principals. Therefore, following this procedure, 589 teenage consumers aged between 14 and 17 years were questioned. The interviews were conducted personally at 30 different schools: 18 public schools and 12 private ones. None of the authors have any competing interests in the manuscript.

3.3. Measurement scales

Diverse tools and scales were used in the present study. Tables and show the items of each variable analysed.

Table 3. Measurement scales.

Table 4. The international classification of adult underweight, overweight and obesity according to BMI.

Low-fat and low-sugar food consumption. Firstly, and based on Grimaldo (Citation2010), a list of different foods was designed. This list aims to measure the dimension ‘food consumption’ using a frequency scale from 5 = always (every day) to 1 = rarely (1–3 times a month or never). According to the literature (Urala and Lähteenmäki, Citation2004), consumers do not consider functional foods as one homogeneous product group. Thus, in this paper, foods were classified into two categories: (1) low-sugar foods (sugar-free breakfast cereals, low-sugar cookies, sugar-free yogurt and juice with no added sugar) and (2) low-fat foods (ham or turkey, skimmed milk, wholemeal bread, low-fat cheese and non-fat yogurt).

BMI. According to the World Health Organization (www.who.int), the BMI is a simple index of weight-for-height that is commonly used to classify underweight, overweight and obesity in adults (see Table ). It is defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres (kg/m2). BMI values are age-independent and the same for both sexes. However, the BMI may not correspond to the same degree of fatness in different populations due, in part, to different body proportions. The health risks associated with an increasing BMI are continuous and the interpretation of BMI grades in relation to risk may differ for different populations.

In our study, this variable is codified as 1 if the young consumer shows a normal range of the BMI and 2 if the young consumer does not show an adequate BMI value.

Healthy/unhealthy lifestyle. According to Grimaldo (Citation2010), the healthy lifestyle comprises three areas of habits and behaviours: sports, repose and sleep habits, and food consumption. The author proposes a scale, based on previous studies, that presents adequate psychometric properties. In our study, consumption of food is an entity in itself and it is not taken into account when measuring the healthy lifestyle. Thus, finally, the scale employed here consists of sports activities and healthy habits.

Sports activities are measured following a frequency scale (1 = never – 1 to 3 times a month or never; 5 = always – every day) proposed by Grimaldo (Citation2010), applied to 4 items (individual sports, team sports, combat, and outdoor and adventure).

Healthy habits are measured following Grimaldo’s (Citation2010) proposal (seven items to measure repose and sleep habits) and another three items from He et al.’s (Citation2004) scale to measure unhealthy habits (tobacco, drugs and alcohol consumption).

Perceptions of healthy/unhealthy eating. Based on Chan et al.’s (Citation2011) study, a five-point Likert scale to measure perceptions of healthy/unhealthy eating is formed by five items for healthy eating perceptions and four items for unhealthy eating perceptions.

4. Results and discussion

The coded data were analysed using the SPSS program. Before contrasting the hypotheses, some descriptive analysis was carried out to facilitate a better understanding of the results. After this, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted first to test for the quality and adequacy of the measurement model by investigating the reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity.

4.1. Descriptive analysis

As Table illustrates, a previous study of some of our variables shows that weight and height involve significant differences among women and men. At the same time, height represents significant differences among public and private centres. In relation to age, no significant differences are found.

Table 5. Descriptive analysis.

All the participants were asked their weight and height, and their BMI was then calculated (kg/m2). As Table indicates, 11.9% of the participants show underweight problems (just 2.2% show severe thinness) and 8.6% overweight problems (no participants suffer from obesity class III and just 5% show obesity class II). As stated before, two groups of young consumers were identified: consumers with adequate BMI values and consumers with inadequate BMI values (underweight and overweight problems). Thus, three groups were confirmed: (1) group 1: underweight problems, (2) group 2: normal weight and (3) group 3: overweight problems.

Table 6. Overall BMI.

4.2. Psychometric analysis

The coded data were analysed using the SPSS program. Following Anderson and Gerbing (1988), CFA was first conducted to test for the quality and adequacy of the measurement model by investigating the reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity.

Therefore, the psychometric properties of the measurement model were evaluated before verifying the proposed hypotheses. First, the univariate and multivariate normality of the observed variables was tested based on the skewness and kurtosis of the observed variables using SPSS software (τ ∼ 0 and κ ∼ 3). Then, a CFA was performed on the measurement scales being studied using the robust maximum likelihood method. Several changes were introduced following various criteria to improve the initial measurement model (Table ).

Table 7. Psychometric properties of the measurement instrument: reliability and convergent validity.

The purification results of the CFA revealed that the goodness of fit of the model and the overall statistics both achieved the best degree of appropriateness and could not be further improved (Table ). The chi-square value for this measurement model was 320.48 with 92 degrees of freedom (p < .000) and the chi-squared/d.f. ratio was 3.5; generally, a chi-squared/d.f. ratio between 2 and 5 is considered an acceptable level of fit (McIver & Carmines, Citation1981). The root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.06 was also within the acceptable range. The comparative-fit index (CFI) was 0.9, and the normed-fit index (NFI) was 0.85. According to Marcoulides and Schumacker’s (Citation2001) standards of model fitting, the results of the CFA indicate a satisfactory fit for the measurement model.

The data collected in Table show the reliability or internal consistency of the scales. Three indicators were used for this purpose: (i) the Cronbach’s alpha for each scale; (ii) the composite reliability index (IFC); and (iii) the variance extracted indices (AVE). Additionally, the factor loadings of each item on each factor were analysed. Although some items and scales were slightly below the recommended values, we retained them in order not to lose useful information (Hodge & Gillespie Citation2003).

To ensure convergent validity, we followed three steps. Firstly, the factorial regression coefficients of the items were analysed to verify their significance in relation to their corresponding latent variables. The t Student value associated with each of the items was used (weak convergence condition) (p > 2.58, 1% significance). In the second stage, the value of the standardized coefficients was found to be greater than the critical value of 0.5 (λ > 0.5) (strong convergence condition). Finally, the third step led to the progressive elimination of indicators that did not display a strong linear relationship (R2 < .5), although in some cases this criterion was reduced slightly following several studies that suggest the possibility of lowering this threshold (R2 < .3). A high explanatory power of the latent variable will result in a higher R2, while a low explanatory power will lead to a lower R2. Following these criteria, 16 items were eliminated (Table ).

To demonstrate discriminant validity, we analysed the variance–covariance matrix between pairs of factors (matrix Φ) and their corresponding confidence intervals (Φ value + two standard errors) (Table ). It is noted that the squared covariance between factors was significantly lower than unity. Additionally, the AVE (main diagonal) for the six factors exceeded the square of the covariance (the top half of the matrix shown in Table ). In cases in which this does not happen, the AVE obtains slightly lower values than the square of the correlation, which suggests discriminant validity as the confidence intervals do not include the value 1.

Table 8. Psychometric properties of the measurement instrument: discriminant validity.

4.3. Hypothesis testing

After analysing the psychometric properties of the diverse scales used in this study, different ANOVA and Pearson correlations were calculated to test the hypotheses stated (Table ). As Table shows, some hypotheses can be accepted (H2a, H3ab, H4ab and H5b), others cannot (H1 and H5a) and another can be partially accepted (H2b). An explanation of the data can be found below.

Table 9. Hypotheses testing.

4.3.1. BMI and low-sugar/fat food intake

The data do not support the assertion that the intake of low-fat and low-sugar foods affects consumers’ BMI (H1). No significant differences were found among the three groups identified. The means of the intake of this kind of product do not present significant differences. Further Pearson correlations are not significant. With the aim of deepening these results, other ANOVA analyses were carried out (see Tables and ). If we analyse each of the low-fat and low-sugar products, the results show that only juice with no added sugar and wholemeal bread present significant differences among the three groups.

Table 10. Low-sugar food intake and BMI groups.

Table 11. Low-fat food intake and BMI groups.

4.3.2. Healthy/unhealthy lifestyle and BMI

Related to H2a (when adolescent consumers have an unhealthier lifestyle, they show more overweight or underweight problems), the mean in group 1 (underweight) and the mean in group 3 (overweight) are higher than that in group 2 (normal BMI), and these differences are significant. Thus, H2a can be accepted.

If we analyse H2b (when adolescent consumers have a healthier lifestyle, they show a more adequate BMI), the results are inconclusive, because they vary according to whether the focus is on sport (p < .05) or sleep (p > .1) practices. Therefore, H2b can be just partially accepted.

Nevertheless, the Pearson correlations for the three facets of lifestyle (unhealthy, sports and sleep) are not significant (p < .1).

4.3.3. Healthy/unhealthy lifestyle and low-sugar/fat food intake

If we analyse the results regarding the means of low-fat and low-sugar food intake and their relationship with the means of unhealthier and healthier lifestyles, H3 can be accepted (all the means are at least p < .1). It must be noticed that the analysis of the Pearson correlations reinforces the relationship between a healthier lifestyle (sleep practices) and low-sugar/fat food intake and between a healthier lifestyle (sport practices) and low-sugar food intake.

4.3.4. Healthy/unhealthy eating perceptions and BMI

The results support the assertion that adolescent consumers with unhealthier eating perceptions show more overweight or underweight problems (inadequate BMI) (p < .1). Consequently, H4a can be accepted. However, although healthier eating perceptions are higher among adolescent consumers with a normal BMI (3.63 as opposed to 3.48 and 3.54), no significant differences can be found. Thus, H4b cannot be supported.

The Pearson correlations are not significant for either the relationship between unhealthier eating perceptions and BMI or the relationship between healthier eating perceptions and BMI.

4.3.5. Healthy/unhealthy eating perceptions and low-sugar/fat food intake

The results cannot support H5a (when adolescent consumers have unhealthier eating perceptions, their consumption of (1) low-fat foods and (2) low-sugar foods will be increased). As Table shows, there are no significant differences between the consumers’ unhealthier eating perceptions and their intake of low-fat food (mean = 2.34, p > .1; Pearson correlation = −0.074, p > .1). In the case of low-sugar food intake, although there is no significant difference among the mean values, there is a significant negative relationship between unhealthier eating perceptions and low-sugar food intake (−0.098, p < .1).

5. Conclusions, implications and further research

The present paper attempts to expand the scientific knowledge related to adolescents’ lifestyles and perceptions and their possible effects on their BMI and their consumption of certain foods. Although this study has some limitations (e.g. adolescent consumers aged between 14 and 17 years are not necessarily representative of the general young population), these findings contribute to a better understanding of how healthy lifestyles and eating perceptions may be related to the intake of some foods. Therefore, in our opinion, this study represents one of the first attempts to examine the effect of health lifestyle and eating perceptions on BMI and the use of low-fat and low-sugar foods.

Must be notice that, according to Grosso et al. (Citation2013, p. 1828), other studies have found an association between nutrition knowledge and food consumption which intensity and significance can vary among the studies and might depend on the study population. As the authors state, several psychological and environmental factors might play a role in food choice, leading to a different attitude towards changing behaviour for health reasons.

In this scenario, and with a sample of 590 young consumers aged between 14 and 17 years, some interesting conclusions and managerial implications can be addressed:

Conclusion: In general, there is no relationship between the intake of low-fat and low-sugar foods and the consumers’ BMI. Only juice with no added sugar and wholemeal bread present significant differences among the three groups. These results emphasize the conclusions of Gatenby et al. (Citation1997), who state that consuming reduced-fat food does not always have a positive effect on weight control.

Managerial implication: Governments and marketers should encourage the use of low-fat and low-sugar foods among adolescents to improve their BMI and, consequently, their health.

Conclusion: Young people with overweight or thinness problems present an unhealthier lifestyle. However, it is not possible to find a significant relationship between an unhealthy lifestyle and BMI. The age of the sample can justify these results because, in that age range, unhealthy activities are less common (tobacco, drugs and alcohol consumption).

Managerial implication: Governments and authorities should pay attention to early drug, alcohol and tobacco consumption. Together with this, manufacturers of tobacco and alcoholic beverages must pay attention to their advertisements and the claims made in their communication campaigns.

Conclusion: Sports activities and good rest and sleep practices are more frequent among young consumers with a normal BMI. This result confirms those found by other authors (i.e. Chaput et al. Citation2006). Despite this result, only for sport activities, the differences are significant.

Managerial implication: Institutional policies should promote a healthy lifestyle among young people. Companies should focus part of their CSR activities and social marketing on aligning this institutional effort in defence of a healthy lifestyle among young people.

Conclusion: When adolescent consumers have an unhealthier lifestyle, their consumption of (1) low-fat foods and (2) low-sugar foods will decrease. When adolescent consumers have a healthier lifestyle, their consumption of (1) low-fat foods and (2) low-sugar foods will increase. Indeed, according to Chen (Citation2011), consumers who are not concerned about their lifestyle habits will also not worry about their diet. Actually, Grimaldo (Citation2010), in line with the literature, proposes to include them in food habits.

Managerial implication: As adolescent consumers’ lifestyle is related to food consumption, public and private institutions must reinforce their communication claims in accordance with this target.

Conclusion: Adolescent consumers with unhealthier eating perceptions show more overweight or underweight problems. Even though there are greater healthier eating perceptions among adolescent consumers with a normal BMI (3.63 as opposed to 3.48 and 3.54), no significant differences can be found. In this sense, these results show that young consumers’ healthy eating perceptions can move to some practices and habits with relevance to the BMI.

Managerial implication: Companies and institutions in the food industry can help adolescents to understand how their eating habits and practices can influence their overweight or underweight problems.

Conclusion: There is a significant negative relationship between unhealthier eating perceptions and low-sugar food intake, but no significant differences can be found among eating perceptions and the intake of low-sugar/fat food. According to Provencher et al. (Citation2009), it can be useful companies and institutions to know the beliefs of young consumers related to the healthiness of foods. As stated before, this consumer segment has very particular characteristics (Paquette Citation2005). Their timing in the life cycle makes an objective view of reality difficult. This may cause young consumers’ perceptions of what is a healthy or an unhealthy diet to be associated with the consumption of certain foods. Importantly, it is advisable to remove certain items from the scales that measure healthy/unhealthy eating perceptions because of their low factorial charge.

Managerial implication: Companies and institutions with some responsibilities in food should focus their campaigns on ‘teaching’ young people both what is meant by a healthy diet and practices that favour a healthy lifestyle.

In sum, the empirical results and findings from this study are helpful for the continued development of the food industry and the public sector and to contribute to further research in this field. According to Chen (Citation2011), beliefs about the healthiness of foods need to be understood in the context of making healthy eating recommendations and claiming health benefits for food products in a society facing increased prevalence of weight problems (thinness, overweight and obesity).

Nevertheless, some limitations of this study should be kept in mind when generalizing the findings. The main limitation of this study is the sample profile and the scales used. Future studies are needed to investigate further other consumer segments and use alternative measures. Another limitation of this study is that the questionnaires relied on subjective self-reporting on healthy lifestyles, eating perceptions and food intake without objectively assessing health-related activities. Further research with this young segment could take into account the opinion of parents or tutors. Future studies should address these issues in other young segments as well.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alvarez Caro F, Díaz Martín JJ, Riaño Galán I, Pérez Solís D, Venta Obaya R, Málaga Guerrero S. 2011. Classic and emergent cardiovascular risk factors in schoolchildren in Asturias. An Pediatr (Barc). 74:388–395. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2011.01.00721411387

- Berthoud HR. 2011. The neurobiology of food intake in an obesogenic environment. The Winter Meeting of the Nutrition Society, Royal College of Physicians; London; December 6–7.

- Caballero B. 2005. A nutrition paradox – underweight and obesity in developing countries. New England J Med. 352:1514–1516.

- Castillo M, Feinstein R, Tsang J, Fisher M. 2015. An assessment of basic nutrition knowledge of adolescents with eating disorders and their parents. Int J Adolescent Med Health. 27:11–17.

- Chan K, Prendergast G, Grønhøj A, Bech-Larsen T. 2011. Danish and Chinese adolescents’ perceptions of healthy eating and attitudes toward regulatory measures. Young Consumers. 12:216–228.

- Chaput JP, Brunet M, Tremblay A. 2006. Relationship between short sleeping hours and childhood overweight/obesity: results from the ‘Quebec en Forme’ project. Int J Obes. 30:1080–1085.

- Chen MF. 2011. The joint moderating effect of health consciousness and healthy lifestyle on consumers’ willingness to use functional foods in Taiwan. Appetite. 57:253–262.

- Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. 2002. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. The Lancet. 360:473–482.

- Fundación BBVA. 2008. La población de Valencia. Población, Cuadernos Fundación BBVA, núm. 29, 1–16.

- Gatenby SJ, Aaron JI, Jack VA, Mela DJ. 1997. Extended use of foods modified in fat and sugar content: nutritional implications in a free-living female population. Amer J Clin Nutrit. 65:1867–1873.

- Gibson SA. 1996. Are high-fat, high-sugar foods and diets conducive to obesity?. Int J Food Sci Nutrit. 47:405–415.

- Gil JM, Gracia A, Sanchez M. 2000. Market segmentation and willingness to pay for organic products in Spain. Int Food Agribusiness Manage Rev. 3:207–226.

- Glanz K, Basil M, Maibach E, Goldberg J, Snyder DAN. 1998. Why Americans eat what they do: taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. J Amer Dietetic Assoc. 98:1118–1126.

- Grimaldo M. 2010. Calidad de vida y estilo de vida saludable en un grupo de estudiantes de posgrado de la ciudad de Lima. Pensamiento Psicológico. 8:17–38.

- Grosso G, Mistretta A, Turconi G, Cena H, Roggi C, Galvano F. 2013. Nutrition knowledge and other determinants of food intake and lifestyle habits in children and young adolescents living in a rural area of Sicily, South Italy. Public Health Nutrit. 16:1827–1836.

- Hallal P, Victora CG, Azevedo MR, Wells JC. 2006. Adolescent physical activity and health. Sports Med. 36:1019–1030.

- He K, Kramer E, Houser RF, Chomitz VR, Hacker KA. 2004. Defining and understanding healthy lifestyles choices for adolescents. J Adolescent Health. 35:26–33.

- Hodge DR, Gillespie D. 2003. Phrase completions: an alternative to Likert scales.Social Work Res. 27:45.

- Kline S. 2011. Globesity, food marketing and family lifestyles. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lappalainen R, Kearney J, Gibney M. 1998. A pan EU survey of consumer attitudes to food, nutrition and health: an overview. Food Qual Pref. 9:467–478.

- Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE. 2001. New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Martínez MS, Pacheco BN, López MS, García-Prieto JC, Niño CT, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. 2012. Trends in excess of weight, underweight and adiposity among Spanish children from 2004 to 2010: The Cuenca study. Public Health Nutrit. 15:2170–2174. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012003473

- McIver J, Carmines EG. 1981. Unidimensional scaling (No. 24). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Moreno LA, Gonzalez-Gross M, Kersting M, Molnar D, De Henauw S, Beghin L, Sjöström M, Hagströmer M, Manios Y, Gilbert CC, et al. 2008. Assessing, understanding and modifying nutritional status, eating habits and physical activity in European adolescents: the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Public Health Nutr. 11:288–299.

- Neovius M, Rasmussen F. 2008. Evaluation of BMI-based classification of adolescent overweight and obesity: choice of percentage body fat cutoffs exerts a large influence. The COMPASS study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 62:1201–1207. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602846

- Oldewage-Theron W, Egal A, Moroka T. 2015. Nutrition knowledge and dietary intake of adolescents in Cofimvaba, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Ecol Food Nutr. 54:138–156.

- Paquette MC. 2005. Perceptions of healthy eating: state of knowledge and research gaps. Can J Public Health/Revue Canadienne de Sante’e Publique. 0:S15–S19.

- Prentice AM, Jebb SA. 1995. Obesity in Britain: gluttony or sloth? BMJ. 311:437–439.

- Pronk NP, Anderson LH, Crain AL, Martinson BC, O’Connor PJ, Sherwood NE, Whitebird RR. 2004. Meeting recommendations for multiple healthy lifestyle factors: prevalence, clustering, and predictors among adolescent, adult, and senior health plan members. Amer J Prev Med. 27:25–33.

- Provencher V, Polivy J, Herman CP. 2009. Perceived healthiness of food. If it’s healthy, you can eat more! Appetite. 52:340–344.

- Ridder MA, Heuvelmans MA, Visscher TL, Seidell JC, Renders CM. 2010. We are healthy so we can behave unhealthily: a qualitative study of the health behaviour of Dutch lower vocational students. Health Educ. 110:30–42.

- Rudd BE. 2007. Achieving healthy body weights in the teenage years: evidence-based practice guidelines for community nutrition interventions [doctoral dissertation]. Mount Saint Vincent University.

- Scully M, Wakefield M, Niven P, Chapman K, Crawford D, Pratt IS, Baur LA, Flood V, Morley B; NaSSDA Study Team. 2012. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents' food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite. 58:1–5.

- Senauer B. 2001. The food consumer in the 21st century: new research perspectives. Retail Food Industry Center, University of Minnesota.

- St-Onge MP, Keller KL, Heymsfield SB. 2003. Changes in childhood food consumption patterns: a cause for concern in light of increasing body weights. Amer J Clin Nutr. 78:1068–1073.

- Tabbakh T, Freeland-Graves JH. 2016. The home environment: a mediator of nutrition knowledge and diet quality in adolescents. Appetite. 105:46–52.

- Thompson AK, Muoghan PJ. 2008. Innovation in the foods industry: functional foods. Innovation. 10:61–73.

- Urala N, Lähteenmäki L. 2004. Attitudes behind consumers’ willingness to use functional foods. Food Qual Preference. 15:793–803.

- van Raaij FW, Verhallen TM. 1994. Domain-specific market segmentation. Eur J Mark. 28:49–66.

- Verbeke W. 2005. Consumer acceptance of functional foods: socio-demographic, cognitive and attitudinal determinants. Food Qual Preference. 16:45–57.

- Vermunt SHF, Pasman WJ, Schaafsma G, Kardinaal AFM. 2003. Effects of sugar intake on body weight: a review. Obesity Rev. 4:91–99.

- World Health Organization. 1995. Physical status: The use of and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee.

- World Health Organization. 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic (No. 894). World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2007. What is the definition of health?; [cited 2014 Dec 1]. Available from: www.who.int/suggestions/faq/en/

- World Health Organization. 2012. Obesidad y sobrepeso. Available from: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/es/

- World Health Organization. 2014. Spanisg Indicators; [visit Nov 11]. Available from: www.who.int/countries/esp/en/

- Worldpress.com. 2011. Los alimentos de la salud. Alimentos funcionales y novel foods. In alimentosdelasalud.wordpress.com/tag.