Abstract

Background: The effects of gender and age on the growth of hepatic hemangioma remain inconclusive. This study aims to further explore the natural growth of hepatic hemangioma and its influencing factors.

Methods: From June 2014 to April 2019, 534 untreated patients who were diagnosed with hepatic hemangioma in our hospital were enrolled. The growth changes of hepatic hemangioma were observed at follow-up by ultrasound.

Results: During the median 18 (14,22) (months of follow-up, 215 (40.3%) patients showed an increase in tumor diameter, 217 (40.6%) tumor diameters decreased, and102 (19.1%) tumor diameters did not change. Before the age of 40, the diameter of hemangiomas in each group of men and women increased with age. After 40 years old, those in men continued to grow slowly, while those in women had a relatively downward trend. Therefore, by investigating annual changes in tumor, it was found that the diameter of female tumors showed a significant downward trend after the age of 40, the difference is most pronounced between 50–60 years old (the annual change is −0.39 (−0.87,0.40) cm).

Conclusion: In the natural growth process of hepatic hemangioma, male and female patients present different trends, which may be related to sex.

Background

Hepatic hemangioma is the most common benign liver tumor, with an incidence of 0.4%–20% (Choi and Nguyen Citation2005). With advances in abdominal imaging modalities and increasing frequency of their use, an increasing number of patients with hepatic hemangioma are being diagnosed (Duxbury and Garden Citation2010). Abdominal ultrasound plays an important role in the diagnosis of most hepatic hemangiomas, which are characterized by a well-defined, hyperechoic, homogeneous lesions with weak enhancement (European Association for the Study of the L Citation2016). Most hepatic hemangiomas are small and asymptomatic, and they are more prevalent in females. A lesion larger than 5 cm in diameter is considered a ‘giant hemangioma,’ which may causes symptoms, such as abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, and spontaneous or traumatic rupture (Kaido and Imamura Citation2003; Hoekstra et al. Citation2013; Chen et al. Citation2019). The exact etiology of this benign disease remains unclear. Related studies have found that estrogen receptors are expressed in hepatic hemangioma and that high estrogen conditions (such as pregnancy and use of oral contraceptives) can promote their growth (Gemer et al. Citation2004; Au and Liu Citation2005; El-Hashemite et al. Citation2005; Yeh et al. Citation2007b; van Malenstein et al, Citation2011). Although there have been reports on the natural growth history of hepatic hemangioma, no consensus has been reached (Glinkova et al. Citation2004; Yeh et al. Citation2007a; Hasan et al. Citation2014; Vernuccio et al, Citation2018). This study investigated the epidemiological characteristics of and the factors affecting the growth of hemangioma, such as age and sex, by analyzing the case data of 534 patients, and hope that our results can provide a theoretical basis for the development of personalized treatment and follow-up programs.

Methods

Patients diagnosed with hepatic hemangioma in the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University from June 2014 to April 2019 were included and their data were collected during follow-up. Because of the lack of specific clinical manifestations, the diagnosis of hepatic hemangioma mainly depends on the results of various imaging examinations. Diagnostic basis: patients with typical ultrasonographic manifestations (clearly defined hyperechoic occupation accompanied by less obvious echo-enhancement effect in the posterior area, which can be compressed, generally without capsule, filled with blood fluid, and mostly with clear boundaries with adjacent tissue) (Mirk et al, Citation1982; Taboury et al. Citation1983; European Association for the Study of the L Citation2016). During the follow-up period, all patients were reviewed by two experienced and designated ultrasound physicians (M.X.L and J.Q.D) of our hospital, and continuous follow-up of the same lesion was ensured, while patients with atypical manifestations (56 cases) underwent Enhanced Computed Tomography or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Imaging examination. Patients with untreated hepatic hemangioma were included in this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 2 or more follow-ups, follow-up time at least 12 months, and patient older than 18 years. Patients with a history of sex hormone medications such as birth control pills and hepatitis will be excluded. Patients who were pregnant or surgically treated during the follow-up were discontinued. Patients were divided into five age groups: <30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60, and >60 years. Data regarding sex, age, initial and final tumor diameter, and follow-up period were recorded. The maximum diameter of the tumor was used to indicate the size. In patients with multiple hepatic hemangiomas, we assessed the sum of up to three tumor diameters. The annual change of tumor growth was expressed by the ratio of size change and follow-up time. Ultrasound examinations of all patients were completed within 1 year after the initial diagnosis. The follow-up period was determined according to changes in tumor diameter, blood test results, and presence or absence of symptoms. Enlargement and shrinkage were defined as changes of at least 0.5 cm during the observation period. Significant enlargement was defined as an increase in size >1 cm during follow up with a final diameter >2 cm (Glinkova et al. Citation2004). Giant hemangioma were defined as haemangiomas with a diameter >5 cm The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University (NO. Y2014057).

Follow-up data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 statistical software. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and One-way ANOVA or LSD t test were used to compare the differences. Continuous variables with anomalous distributions are represented as medians with quartile ranges. The mann–whitney U test is used for nonparametric variables. A revised P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics and hemangioma characteristics

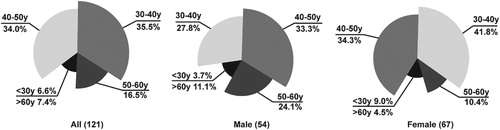

Of the 590 patients with hepatic hemangioma, 32 patients developed symptoms of abdominal discomfort and received treatment, 16 of whom received surgical treatment and 5 received pulse embolization or percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in other hospitals. 24 patients refused to follow-up or were lost to follow-up. The remaining 534 patients were included in the study. Patient demographics and hemangioma characteristics are summarized in Table . Mean age at onset was 47.19 ± 10.64 years. The cohort comprised 214 men and 320 women (male: female ratio, 2:3.8). Overall, 14.2% patients had multiple hepatic hemangiomas and 85.8% had a single hepatic hemangioma. Regarding location, 77.2% of hemangiomas were in the right lobe of the liver. Mean tumor diameter 4.40 ± 1.90 cm in males and 4.05 ± 1.86 cm in females. There were 121 cases (54 (44.6%) males and 67 (55.4%) females) with significantly enlarged hemangioma lesions, mostly in the age group of 30–40 and 40–50 years of age (Figure 3). the changes in 24 lesions showed an increasing trend, and by the end of follow-up, they had become giant hemangiomas (>5cm in diameter), 16 patients who underwent surgical treatment were mostly treated for abdominal discomfort, and 1 of them was diagnosed as spontaneous internal bleeding after surgery. Most of the symptoms were relieved after surgery. See Table for details.

Table 1. Basic information of 534 patients with hepatic hemangioma.

Table 2. Clinical information of 16 patients undergoing surgical treatment of hepatic hemangioma.

Differences in tumor diameter with age

During a median follow-up of 18 (Hasan et al. Citation2014; Kamyab and Rezaei-Kalantari Citation2019) months, 215 patients showed an increase in tumor diameter, 217 showed a decrease in tumor diameter, and 102 showed no notable change in tumor diameter (ratio: ∼2:2:1). Patients were divided into five age groups and two sex groups. Differences and trends of hemangioma growth were assessed and compared among different age groups, between sex groups, (Figure and Table ). Before 40 years of age, mean tumor diameter was larger in females than in males. After 40 years of age, mean tumor diameter was smaller in females than in males. In male patients, the tumor diameter of all age groups increases with age. In females, the diameter was the largest in patients aged 30–40 years and the diameter showed an initial increasing and then decreasing trend. Meanwhile, the difference in tumor diameter among different age groups was statistically significant among females (p = 0.001). At 40–50 and 50–60 years of age, tumor diameter in females was significantly smaller than that in males (p = 0.017 and p = 0.004), and the difference was statistically significant.

Figure 1. The size of liver hemangioma in different age groups. A. Total patients. B. Male patients. C. Female patients.

Table 3. Hemangiomas in different age groups and gender groups.

Growth trend of hemangioma

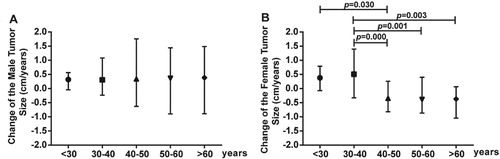

To further explore the reasons for the different trends of tumor growth in males and females, we calculated the annual change of tumor diameter (Figure ). The tumor size of male patients increased with age. Before the age of 40, female patients also showed an increasing trend, and the annual growth rate was higher than that of male patients, especially in the age of 30–40 years. However, after the age of 40, the tumor diameter of female patients showed a decreasing trend, which was most obvious between the ages of 50–60 (−0.39 (−0.87,0.40) cm/year).

Discussion

Hepatic cavernous hemangioma is the most common benign tumor of the liver (Yin et al, Citation2018), with a reported prevalence of 20% in autopsy (Bahirwani and Reddy Citation2008). This tumor is typically observed in females (female: male ratio = 5:1) at an average age of 50 years (Duxbury and Garden Citation2010). Hepatic hemangiomas are often found incidentally on abdominal ultrasonography (Adriana et al, Citation2014), and atypical lesions should be further investigated with contrast-enhanced imaging studies such as CT scan and MRI (Satoshi et al, Citation2009). Abdominal pain and discomfort caused by dilatation of the liver capsule are the most common clinical manifestations of symptomatic hepatic hemangioma, whereas spontaneous hemorrhage and Kasabach–Merritt syndrome are rare, but extremely dangerous (Trotter and Everson Citation2001; Vernuccio et al, Citation2018; Kamyab and Rezaei-Kalantari Citation2019), and the mortality rate of Kasabach–Merritt syndrome has been reported to be up to 40% (O'Rafferty et al. Citation2015). In our study, the majority of patients with hepatic hemangioma are asymptomatic, and most of the lesions were found due to physical examination, other gastrointestinal diseases and abdominal discomfort.

In previous studies, it was found that hepatic hemangioma in mouse expressed estrogen and progesterone receptors, and estrogen therapy significantly increased serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels, while tamoxifen reduced vascular endothelial growth factor levels (El-Hashemite et al. Citation2005). Meanwhile, many studies have reported that hepatic hemangioma is more likely to occur in female patients, and the state of tall estrogen during pregnancy and long-term use contraceptives can promote the growth of hepatic hemangioma (Gemer et al. Citation2004; El-Hashemite et al. Citation2005; van Malenstein et al, Citation2011; Bara et al. Citation2016). However, Some scholars believe that hepatic hemangioma is not related to menstruation, reproduction and oral contraceptive use history (Au and Liu Citation2005), and there was no significant difference in the development of hepatic hemangioma between males and females, with both sexes showing an increasing trend (Li et al. Citation2015; Liu et al, Citation2018). Obviously, the effect of estrogen on hepatic hemangioma is still controversial. In this study, the prevalence of female patients was significantly higher than that of male patients, and the tumor diameter in females increased first and then decreased with age. After the age of 40 years, there was a trend of decrease, especially in the age group of 50–60 years, in which the decline was the most obvious (Table and Figure ). We know that estrogen levels in females peak at around 30 years of age and then gradually decline, especially during menopause. Interestingly, the trend of tumor changes in females was basically consistent with the trend of change in estrogen levels with age. Thus, we believe that changes in hemangioma growth trends may be due to fluctuations in estrogen levels.

Figure 3. Distribution of hepatic hemangioma in 121 cases with ‘significant enlargement’. Significant enlargement was defined as an increase in size >1 cm during follow up with a final diameter >2 cm.

The role of female hormones in hemangioma growth has been demonstrated in a long-term follow-up study (Glinkova et al. Citation2004). Similarly, our large-sample follow-up study revealed that the proportion of patients with decreased, enlarged and unchanged tumor diameter was about 2:2:1, and there were significant differences in hemangioma growth between men and women. Therefore, we also believe that female hormones play an important role in the natural development of hepatic hemangioma. The literature reports that the diameter of hemangioma is the largest at 40–49 years of age, while it is the smallest at 20–29 years of age. Age is an important factor affecting the growth rate of hepatic hemangiomas (Liu et al, Citation2018). In our study, there was no statistically significant difference in tumor diameter across age groups, although there were significant differences in tumor changes between the sexes. Therefore, age may not be an essential factor affecting the natural growth and change of hepatic hemangioma. The results may be explained by difference in sex and estrogen levels.

Asymptomatic patients with hepatic hemangioma of <5-cm diameter need not be treated, and only one follow-up within 6 months is sufficient. Asymptomatic patients with giant hemangiomas may require more rigorous monitoring. Nevertheless, sever symptoms, complications, and inability to rule out malignant tumors require active treatments, including surgical removal, resection, and arterial embolization (Trotter and Everson Citation2001; Biecker et al. Citation2003; Kanetkar et al. Citation2018). However, when discussing surgical indications and follow-up plans for hepatic hemangioma, sex is rarely considered. The authors believe that sex is an important factor affecting the natural progression of hepatic hemangioma. Particularly, pregnant or adolescent females and females with a long history of contraceptive use may be at a high of developing hepatic hemangioma. High estrogen levels may lead to a rapid increase in hemangioma diameter, oppressing the surrounding tissues and thereby causing severe complications. In such case, the growth potential of the hemangioma is a vital factor to be considered in the formulation of treatment plans and follow-up plans.

In summary, in the natural growth process of hepatic hemangioma, male and female patients present different trends, which may be related to sex. Next, we will continue to follow up these patients in the following studies and expand the sample size.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adriana T, Ahmed-Emad M, Annalisa A, Michele M, Giulia M, Francesco L, Bertino G, Carlo ID. 2014. What is changing in indications and treatment of hepatic hemangiomas. A review. Ann Hepatol. 13(4):327–339. doi: 10.1016/S1665-2681(19)30839-7

- Au WY, Liu CL. 2005. Growth of giant hepatic hemangioma after triplet pregnancy. J Hepatol. 42(5):781. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.028

- Bahirwani R, Reddy KR. 2008. Review article: the evaluation of solitary liver masses. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 28(8):953–965.

- Bara Jr. T, Gurzu S, Jung I, Muresan M, Szederjesi J, Bara T. 2016. Giant cavernous hepatic hemangioma diagnosed incidentally in a perimenopausal obese female with endometrial adenocarcinoma: a case report. Anticancer Res. 36(2):769–772.

- Biecker E, Fischer HP, Strunk H, Sauerbruch T. 2003. Benign hepatic tumours. Z Gastroenterol. 41(2):191–200. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37316

- Chen L, Zhang L, Tian M, Hu Q, Zhao L, Xiong J. 2019. Safety and effective of laparoscopic microwave ablation for giant hepatic hemangioma: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg. 39:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2019.02.001

- Choi BY, Nguyen MH. 2005. The diagnosis and management of benign hepatic tumors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 39(5):401–412. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000159226.63037.a2

- Duxbury MS, Garden OJ. 2010. Giant haemangioma of the liver: observation or resection? Dig Surg. 27(1):7–11. doi: 10.1159/000268108

- El-Hashemite N, Walker V, Kwiatkowski DJ. 2005. Estrogen enhances whereas tamoxifen retards development of Tsc mouse liver hemangioma: a tumor related to renal angiomyolipoma and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Cancer Res. 65(6):2474–2481. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3840

- European Association for the Study of the L. 2016. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. J Hepatol. 65(2):386–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.001

- Gemer O, Moscovici O, Ben-Horin CL, Linov L, Peled R, Segal S. 2004. Oral contraceptives and liver hemangioma: a case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 83(12):1199–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00551.x

- Glinkova V, Shevah O, Boaz M, Levine A, Shirin H. 2004. Hepatic haemangiomas: possible association with female sex hormones. Gut. 53(9):1352–1355. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.038646

- Hasan HY, Hinshaw JL, Borman EJ, Gegios A, Leverson G, Winslow ER. 2014. Assessing normal growth of hepatic hemangiomas during long-term follow-up. Jama Surg. 149(12):1266–1271. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.477

- Hoekstra LT, Bieze M, Erdogan D, Roelofs JJ, Beuers UH, van Gulik TM. 2013. Management of giant liver hemangiomas: an update. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 7(3):263–268. doi: 10.1586/egh.13.10

- Kaido T, Imamura M. 2003. Images in clinical medicine. Giant hepatic hemangioma. N Engl J Med. 349(20):e19. doi: 10.1056/ENEJMicm010097

- Kamyab AA, Rezaei-Kalantari K. 2019. Hepatic hemangioma in a cluster of Iranian population. J Med Ultrasound. 27(2):97–100. doi: 10.4103/JMU.JMU_98_18

- Kanetkar A, Garg S, Patkar S, Shinde RS, Goel M. 2018. Extracapsular excision of hepatic hemangioma: a single centre experience. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 22(2):101–104. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.2018.22.2.101

- Li J, Yan Y, Huang L, Liu C, Yan J, Xu F. 2015. New recognization of the natural history and growth pattern of hepatic hemangioma in adults. J Hepatol. 62:S454–S4S5. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(15)30593-6

- Liu X, Yang Z, Tan H, Xu L, Liu L, Huang J, Si S, Sun Y, Zhou W. 2018. Patient age affects the growth of liver haemangioma. HPB. 20(1):64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.08.021

- Mirk P, Rubaltelli L, Bazzocchi M, Busilacchi P, Candiani F, Ferrari F, Giuseppetti G, Maresca G, Rizzatto G, Volterrani L, et al. 1982. Ultrasonographic patterns in hepatic hemangiomas. J Clin Ultrasound. 10(8):373–378. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870100805

- O'Rafferty C, O'Regan GM, Irvine AD, Smith OP. 2015. Recent advances in the pathobiology and management of Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Br J Haematol. 171(1):38–51. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13557

- Satoshi G, Masayuki K, Hiroshi K, Ryujiro Y, Kimihiro K, Yusuke T, Shiratori Y, Onozuka M, Moriyama N. 2009. Hepatic hemangioma: correlation of enhancement types with diffusion-weighted MR findings and apparent diffusion coefficients. Eur J Radiol. 70(2):325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.035

- Taboury J, Porcel A, Tubiana JM, Monnier JP. 1983. Cavernous hemangiomas of the liver studied by ultrasound. Enhancement posterior to a hyperechoic mass as a sign of hypervascularity. Radiol. 149(3):781–785. doi: 10.1148/radiology.149.3.6647856

- Trotter JF, Everson GT. 2001. Benign focal lesions of the liver. Clin Liver Dis. 5(1):17–42. doi: 10.1016/S1089-3261(05)70152-5

- van Malenstein H, Maleux G, Monbaliu D, Verslype C, Komuta M, Laleman W, Cassiman D, Fevery J, Aerts R, Roskams T, et al. 2011. Giant liver hemangioma: the role of female sex hormones and treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 23(5):438–443. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328345c87d

- Vernuccio F, Ronot M, Dioguardi Burgio M, Lebigot J, Allaham W, Aube C, Aubé C, Brancatelli G, Vilgrain V. 2018. Uncommon evolutions and complications of common benign liver lesions. Abdom Radiol. 43(8):2075–2096. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1427-6

- Yeh WC, Yang PM, Huang GT, Sheu JC, Chen DS. 2007a. Long-term follow-up by ultrasonography: growth rate of hepatic hemangiomas with emphasis on the of the tumor. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 54(74):475–479.

- Yeh WC, Yang PM, Huang GT, Sheu JC, Chen DS. 2007b. Long-term follow-up of hepatic hemangiomas by ultrasonography: with emphasis on the growth rate of the tumor. Hepatogastroenterology. 54(74):475–479.

- Yin X, Huang X, Li Q, Li L, Niu P, Cao M, Guo F, Li X, Tan W, Huo Y. 2018. Hepatic hemangiomas alter morphometry and impair hemodynamics of the abdominal aorta and primary branches from computer simulations. Front Physiol. 9:334. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00334