Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disease persisting predominantly in the pediatric population. Its development is most presumably multifactorial and a derivative of interplay between genetic, immunologic, and environmental causes. To the authors’ knowledge, no multinational and systematic database of AD prevalence is established and maintained for Europe. Thus, epidemiologic data originating from the multinational studies was compiled to draw a picture of AD in both pediatric and adult populations in Europe. The outcomes of this exercise support the general observation that AD prevalence follows the latitudinal pattern with higher prevalence values in northern Europe and decreases progressively towards southern Europe. Noteworthy, the data shows significant differences on the country-level, with higher prevalence in municipal areas than rural. Finally, and unsurprisingly, the collected data reinforces the observation of AD prevalence being highest in pediatric populations in contrast to adults. Herein, data presented was additionally supplemented with the information on current standing on AD etiology.

Introduction to atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD), interchangeably called Atopic Eczema, is a chronic pruritic inflammatory disease commonly affecting children, and, to a lesser extent, adults. AD diagnoses are continuously on the rise, oscillating between 10% and 20% of the pediatric population. The condition develops predominantly in early childhood:

In 45% of children, symptoms appear prior to 6 months of age;

In 60% of patients, symptoms appear before reaching 1 year of age;

In 30% of children diagnosed with AD, the disease will present itself before the age of 5; and

In the remaining 10% of the population with AD, symptoms manifest between 6–20 years of age.

In the absence of a specific diagnostic laboratory marker, AD diagnosis is performed clinically based on the patient’s medical history, specific clinical symptoms, and exclusion of other non-inflammatory skin disordersCitation1. The most distinct features of the disease include pruritus, skin dryness, and other skin lesions such as serous exudate, excoriation, papules, and lichenification. Moreover, ∼ 60% of children with AD are predisposed to develop one or more atopic comorbidities, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, or food allergies. This phenomenon is termed “atopic march”, and its causes are being further researched. Although AD is not a life-threatening condition, it significantly lowers patients’ quality-of-life, and can lead to anxiety and depressionCitation2.

The pathogenesis of AD is multifactorial, and presumably originates from the interplay of genetic, immunologic, environmental factors, infections causing dysfunctions of the skin barrier, and inflammationCitation3. Additionally, structural disorders of certain proteins (i.e. filaggrin) and ceramides are relevant to the development of AD. An allergen stimulates dendritic cells of the skin which triggers Th2 lymphocytes to release pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13). High concentrations of cytokines activate serine proteases causing further functional impairments of the skin barrier. Th1 lymphocytes are also involved in this pathogenic process at the chronic stage of AD. It is speculated that the Th17 and Th22 lymphocytes might also participateCitation4.

The pruritus exacerbates AD and can trigger an itch/scratch cycle. The current focus of research is on biological therapy targeting interleukins IL-4/13 and IL-31 associated with pruritus. Treatment options for AD are outlined in greater detail below.

Atopic dermatitis in Europe

Trends and risk factors

Atopic dermatitis is classified as the most common inflammatory skin disease affecting up to 20% of children and adolescents worldwide, which can significantly decrease the patient’s quality-of-life. It is speculated that the prevalence of AD consistently increased over the last four decades in Europe, yet strong scientific evidence to back this claim is not availableCitation5. Most epidemiological data is comprised of patient-reported outcomes reported through questionnaires. These data are difficult to compare and interpret as the research methodology differed in terms of questionnaire design (whether it was self-reported symptoms in adolescents, maternal skin examinations or doctor’s diagnoses) and the scope of data collected (age, sex, geography, etc.). Certain trends and conclusions can be made based on published studies. European trends remain in-line with those reported from global studies, including the following:

AD is more prevalent in overcrowded urban areas;

Symptoms are worsened in cold or temperate climate; and

Significantly more frequent occurrence of AD is reported in children compared to adultsCitation6.

A higher prevalence of AD is associated with the following risk factors:

Urban environment;

Higher socioeconomic status;

Higher level of family education;

Family history of AD;

Females 6 years and older; and

Smaller family sizeCitation7.

Epidemiology

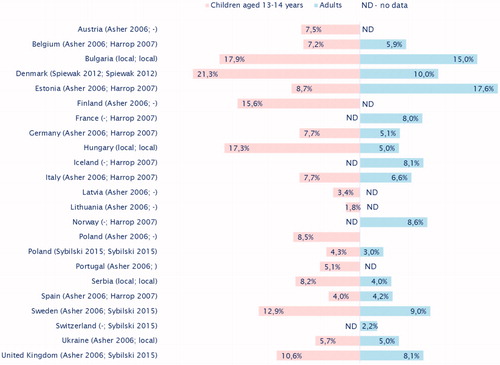

To the authors’ best knowledge, no international, validated databases of epidemiological data about AD occurrence across Europe exist. Hence, the data sources to be considered include country-level data obtained from national registries, country-level, or international studies. In order to retrieve country-level prevalence values acquired with comparable, standardized methodology of data collection in the same demographic groups, it was decided to run the between country comparison on results collected within relevant multinational epidemiological studies with extensive European components such as the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), The European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS), and the Epidemiology of Allergic Disorders in Poland (ECAP)Citation8–10. Their outcomes, combined with input from KCR local resources for Bulgaria, Serbia, and the Ukraine, provide numerical insights into AD prevalence in adolescents aged 13–14 years old across selected European countries included in the studiesCitation11. The figure below shows the average prevalence of current AD diagnoses in European countries considered in this comparative exercise and representing distinct European regions.

As depicted in , the prevalence of AD in European adolescents aged 13–14 years of age oscillates between 1.5% in Lithuania and 15% in Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, and Hungary. AD prevalence in western and northern European countries indicate a higher mean than eastern countries, presumably due to socioeconomic conditions. Some rapidly developing Central and Eastern European countries, such as Poland and Hungary, present AD prevalence that substantially surpasses the global mean value of ∼7.3%Citation12. Of note, differences revealed by previously mentioned epidemiological studies are not only apparent between countries, but between different sites within the same country or city as well. Similar non-homogeneous disease distribution is noticeable globally. Noteworthy, the presented data draw the approximate picture of AD prevalence and highlight the relative difference between countries. However, it should be considered that the sourcing of epidemiologic data impacts the quantitative comparison as the methodology of data collection and surveyed population demographics between studies and registries significantly differ. For example, given that it is feasible, performing similar comparisons based on country-level data would presumably lead to corresponding relative AD prevalence distribution, but absolute numbers might vary. For example, considering a recent publication from France on AD prevalence, its level in population ≥15 years old was estimated at a level of 4.5%, while ECRHS, as depicted on the figure, estimated AD in French adults at 8%Citation13.

Figure 1. Epidemiology of AD for the 13–14 years age group (Denmark: 12–16 years) and adults according to outcomes from multinational epidemiological research programs8–10 complemented with input for Hungary, Serbia, and the Ukraine from KCR local resources (data marked as “local”). Each country has in brackets a reference of data cited for the 13–14 years age group (left) and adults (right).

AD remains a substantial challenge in adult populations, yet prevalence rates in adults vs children are significantly lower worldwide. The data in demonstrates similar trends in AD prevalence for adolescents and adults. Northern and a few western countries exhibit the highest prevalence in AD rates, while central European countries show intermediate values, and countries located in southern Europe with a warm climate, like Spain, feature the lowest rates.

Conclusions

Atopic dermatitis is predominantly a pediatric disease attributed to many causes, including genetics, environment, and the skin microbiome. More focus is being placed on the immunological origin of AD and is being driven by the success of immunotherapy treatments. Several risk factors for AD development were identified. However, the complete elucidation of AD pathogenesis remains underway. Despite the disease’s uneven but widespread presence in Europe, no global registry of AD prevalence exists. Recent multinational observational studies show AD is more prevalent in countries with cold and temperate climates. However, this does not exempt southern countries from the presence of AD, as the disease is also prevalent in highly-populated locations. Research is still necessary to fully address all questions around AD diagnosis and identify optimal treatments.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Elżbieta Kowalska-Olędzka acted as an advisor, speaker and investigator for Galderma, Leo Pharma, Pierre Fabre, L'Oreal, La Roche Posay, Axxon, and Polpharma. Magdalena Czarnecka, Anna Baran and the peer reviewers have relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

None reported.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Eichenfield LF, Ahluwalia J, Waldman A, et al. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of the joint task force practice parameter and American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:S49–S57.

- Linnet J, Jemec GB. An assessment of anxiety and dermatology life quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:268–272.

- Rutkowski K, Sowa P, Rutkowska-Talipska J, et al. Allergic diseases: the price of civilisational progress. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:77–83.

- Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1344–1354.

- Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase One and Three Study Groups, et al. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide?. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:947–954.e15.

- Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66:8–16.

- DaVeiga SP. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis: a review. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33:227–234.

- Sybilski AJ, Raciborski F, Lipiec A, et al. Atopic dermatitis is a serious health problem in Poland. Epidemiology studies based on the ECAP study. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:1–10.

- Harrop J, Chinn S, Verlato G, et al. Eczema, atopy and allergen exposure in adults: a population-based study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:526–535.

- Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–743.

- Dorynska A, Spiewak R. Epidemiology of skin diseases from the spectrum of dermatitis and eczema. Malays J Dermatol. 2012;29:1–11.

- Mallol J, Crane J, von Mutius E, et al. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) phase three: a global synthesis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2013;41:73–85.

- Richard M-A, Corgibet F, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted prevalence estimates of five chronic inflammatory skin diseases in France: results of the « OBJECTIFS PEAU » study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1967–1971.