ABSTRACT

Current comparative analyses of gender attitudes among adolescents largely focus on individual-level characteristics. Understudied is the role of women’s protest on adolescents’ gender attitudes. This paper investigates how women’s protests reported in national news shape young citizens’ gender attitudes across 32 countries. Using the IEA International Civic and Citizenship Study survey data (2009), we test whether women’s protests have a positive impact on egalitarian gender attitudes among adolescents. Our multi-level models demonstrate that girls are more egalitarian in their gender attitudes than boys. The gap between boys and girls changes depending on the level of gender equality in a country. In countries with lower gender equality, the gender gap increases slightly as the number of women’s protests increases, although the difference is not significant. In countries where gender equality is already high, the gender gap is significant at all levels of protest but narrows as protest increases. Our findings expand scholars’ understanding of how protest influences public opinion among young people and have important implications for how gender attitude change occurs and whether women’s protest serves as a tool for developing gender equality.

In March 1992, tens of thousands of Greek Cypriot women formed a human chain in the buffer zone between Turkish and Greek Cyprus to protest the Turkish occupation of Cyprus. Newspaper accounts emphasized the gendered nature of the protest by highlighting that women of all ages participated and by tying the demands to gender equity through protestor quotes such as “the women of Cyprus are still demanding basic rights” (Efty Citation1992). Protests by women have occurred around the world – sometimes campaigning for gender equality and sometimes for other issues. The emphasis on women as the main actors raises the question of how organizing around gender influences wider perceptions of gender attitudes. For example, do public protests by mothers, as occurred against the war in Nicaragua (De Volo Citation2004) and against nuclear energy in Japan (Freiner Citation2013), shape public opinion regarding women’s roles? Not only do these women protestors demand policy changes on governments, but through their organized protest as women, they also present egalitarian visions of women in politics and society. Gender and social movement scholars have investigated whether women’s movements with gender equality as a goal shape public opinion, but little work examines the impact of wider protests organized by women but not necessarily for gender equality, particularly on youth gender attitudes cross-nationally. This paper utilizes cross-national surveys to answer the question: how do women’s protests shape adolescents’ gender attitudes?

Previously, few studies have developed cross-national measures of women’s protest (with perhaps the exception of Htun and Weldon Citation2012). Combined with the paucity of gender role questions in cross-national surveys, analyzing whether protests by women transform gender attitudes has been difficult (Burns and Gallagher Citation2010). Consequently, scholars tend to focus on single cases (e.g. Aronson Citation2008; Branton et al. Citation2015; Sadiqi and Ennaji Citation2006; Valentim Citation2019) or attribute over-time change in public opinion to societal change (e.g. Inglehart and Norris Citation2003, 20; Wilcox 1991). Furthermore, few studies have applied existing measures to attitudinal research on the adolescents, despite the importance of age in political socialization processes and despite social movement literature suggesting that movements alter political attitudes.

Understanding the influence of women’s protestFootnote1 on youth support for gender equality is vital. Adolescence corresponds with the development of independent political attitudes and ideologies that are carried into adulthood. The learning of predispositions toward specific gender roles is also an important part of the political socialization of adolescents (Burns and Gallagher Citation2010; Schnittker, Freese, and Powell Citation2003). Adolescents’ experiences during this crucial period can persist well into middle age or even throughout the life course (Jennings Citation2002; Jennings and Niemi Citation2014). Just as exposure during the 1960s movements had long-term impacts on young people’s partisanship and voting (Jennings and Markus Citation1984), women’s protest may alter their long-term views on gender. Although parental messages about gender predominantly affect young children, teenagers begin to interpret, process, negotiate, and respond to additional information they receive, leading to potential attitude changes (Smetana, Robinson, and Rote Citation2015). Scholars have found extensive socialization of cultural and ethnic attitudes among adolescents (Alexander et al. Citation2004). For example, girls have a higher propensity to participate in politics in the future after being exposed to a stronger legislative presence of women (Wolbrecht and Campbell Citation2007). Yet, we do not know how women’s protests – indicating women’s presence in unconventional politics – shapes youth gender attitudes.

This paper contributes to the understanding of gender attitudes development by exploring how women’s protest in 32 countries alters young citizens’ gender-egalitarian attitudes. We argue that since women’s visibility in these protests normalizes their presence in the public and political sphere and challenges gendered hierarchies within unconventional politics (Sadiqi and Ennaji Citation2006; Moghadam and Sadiqi Citation2006), their impact on gender attitudes needs to be empirically assessed. If we extend findings by authors who show that women’s movements transform gender attitudes (Banaszak and Ondercin Citation2016; Moghadam and Sadiqi Citation2006; Tripp et al. Citation2008, 2), we would expect to see the public visibility of women’s protest also enhancing egalitarian attitudes among adolescents. Using Murdie and Peksen’s (Citation2015) comparative data on women’s protests in the Reuter’s news service and the International Educational Achievement’s International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) survey (2009), we test the connection between women’s protests and youth gender attitudes cross-nationally. Our analysis suggests that the overall effect of women’s protest is significant, although weak, in influencing the hearts and minds of young citizens. We also find that the effect depends on the level of gender equality in the country. In countries where gender equality is low, boys and girls become more egalitarian in their attitudes as women’s protest increases and the gender gap in attitudes narrows. In countries where gender equality is already high, we find that exposure to women’s protests reduces egalitarian gender attitudes slightly and that the gap between boys and girls disappears. The results suggest that gendered protest affects gender attitudes, particularly for young men who are less supportive of gender equality. However, this effect depends upon the existing level of gender equality.

Developing support for gender equality in adolescence

Extant scholarship on youth attitudes shows that their daily interactions and surroundings shape how they develop beliefs and values (Kallio and Häkli Citation2011; Jennings and Niemi Citation2015). Children acquire information regarding gender roles early on from their immediate surroundings (Grusec and Hastings Citation2014; Levinsen and Yndigegn Citation2015). For example, children raised in households with working mothers are more likely to have egalitarian gender attitudes (Gadallah, Roushdy, and Sieverding Citation2017). Schools – including educational curriculum, teachers, and peers – also gender teenagers’ environments, influencing the gender attitudes they internalize (Cribb and Haase Citation2016; Quintelier Citation2015). Although these factors help adolescents formulate their gender ideologies, studies suggest that political context also shapes adolescents’ attitudes (Raviv et al. Citation2000). For example, seeing women run for political office and serving as elected officials also helps girls to envision themselves as political leaders (Wolbrecht and Campbell Citation2007).

Moreover, gender attitudes develop early but are clearly affected by an individual’s experiences in the workforce, family, and higher education. Focusing on gender attitudes among adolescents allows us to examine the role of protest without the potentially endogenous influences of other crucial life experiences. Attitudes towards gender inequality are developed earlier than other political attitudes (Martin and Ruble Citation2010; Neff, Cooper, and Woodruff Citation2007), although some identify the crucial age for political self-consciousness as between 17 and 25 years of age (Jennings and Niemi Citation2014). For example, Bartini’s (Citation2006) longitudinal study shows that adolescents’ flexibility in gender attitudes increases around 12–13 years of age. Adolescents exposed to egalitarian gender ideologies or experiences develop more egalitarian attitudes. An adolescent’s environment also becomes increasingly more important than parental influence as they age (Davis Citation2007). Given the importance of adolescents’ environment in their gender attitude development, we turn to the literature on gender and movements to understand how women’s protest might influence gender attitudes.

The impact of women’s protests on youth attitudes

Scholars have demonstrated that social movements influence the attitudes of those adults that participate (Amenta et al. Citation2010; McAdam Citation1990), as well as those that are indirectly exposed to the movement (Hassim and Gouws Citation1998; Whittier Citation1997; Banaszak and Ondercin Citation2016). For example, not only did the Israel’s Four Mothers Peace Movement successfully lead to an end of Israel’s war in Lebanon in the 1990s, but the movement also shifted public opinion against war (Liberfeld Citation2009). Large-scale protest and other “national political conflicts” provide opportunities for youth attitude changes as well (Youniss et al. Citation2002, 132). Similarly, where public forums about the environment, like the recent climate strikes among children and young adults, occur more regularly, individuals become more environmentally conscious (Wray-Lake, Flanagan, and Osgood Citation2010). We argue that women’s protest, regardless of issue focus, shapes youth gender attitudes for several reasons.

First, because gendered hierarchies often exist within social movements, protests where women are the key players raise issues of gender inequality and ultimately challenge the hierarchies that exist. For example, women’s presence in environmental campaigns, especially in authoritarian regimes (Salime Citation2012) and traditional societies (Morgan Citation2017), opens up the platform for highlighting women’s struggles. In these cases, the fact that women act as protestors, mobilizers, and leaders raises consciousness about the salience of gender equality, unfolding opportunities to examine existing gender inequities. Even anti-feminist women’s protest may have the same effect to the extent that women activists act as women and acknowledge the salience of gender as an issue, thereby reinforcing the legitimacy of the gender identity and motivating individuals to reconceptualize their understanding and expectations of gender (Klatch Citation2001).

Second, activism and leadership in women’s protests may highlight these women as role models, leading young people to become more gender egalitarian. Although adolescents are unlikely to personally come in contact with women protesters, these women’s activities publicized through the media as well as through social networks and social and political institutions provide a political environment and cues – even on a very general level – for adolescents to question traditional gender roles. The normalized presence of women protesting in the streets may stimulate a desire for gender equality and a willingness to adopt egalitarian gender roles. Therefore, we expect:

H1: In countries with more women’s protest events, there will be a corresponding increase in gender-egalitarian attitudes among boys and girls.

By the age of 14 or 15, girls have developed both an in-group preference for other women and an understanding of gender bias and discrimination (Brown et al. Citation2011; Rudman and Goodwin Citation2004). Women’s protest expands opportunities to girls by providing models of women’s political activism and also highlighting – implicitly or explicitly – gender egalitarianism in unconventional politics. Although girls are not yet influenced by marriage, work, caring responsibilities, and other challenges exclusive to adults, they may still consider these expanded future opportunities in a more positive light, given the overall climate of the country in which they reside.Footnote2 This connection to other women also increases the likelihood of girls empathizing with women’s presence in protests and having a sense of injustice when gender inequality is highlighted by women’s protests. Just as the presence of women politicians has been found to be inspiring for women and girls to participate in politics (Liu and Banaszak Citation2017), women activists may also inspire girls to be more supportive of women’s equality. As a result, we expect girls to be more receptive than boys to the strong presence of women activists leading us to hypothesize:

H2a: Women’s protest events will increase egalitarian gender attitudes in girls more than boys.

H2b: Women’s protest events will increase egalitarian gender attitudes in boys more than girls.

In particular, in countries with high levels of gender equality, young people may already be highly egalitarian in their attitudes, meaning there is little room for women’s protests to increase gender egalitarianism. Seeing women “demanding more,” especially in countries where many believe that gender equality has been achieved, could even stimulate backlashes, reducing individual beliefs that gender inequities need to be improved and support for gender equality. On the other hand, in countries where gender equality is low, women’s protests serve as a catalyst for dialogues about and attention to the status of women. Such attention could then stimulate individuals to learn more about and understand the importance of gender equality. Therefore, we expect that increasing levels of women’s protest will have a greater effect on adolescents’ gender egalitarianism in countries with lower levels of gender inequality.

H3: Women’s protest events will increase egalitarian gender attitudes more in societies with low levels of gender equality than in countries with high levels of gender equality.

Data and methods

To examine how women’s protest affects youth gender attitudes, we use the 2009 IEA ICCS, which surveyed students who were 14–15 years of age,Footnote3 about their opinions on various topics including gender equality. The survey allows us to compare students across countries with different histories of women’s protests.

We combine the ICCS survey with information about women’s protests gathered by Murdie and Peksen (Citation2015), as well as other national data from various sources. displays the descriptive statistics for all variables. Our analysis includes 32 countries: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Chile, Colombia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, the Dominican Republic, England, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, South Korea, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Poland, Paraguay, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, and Thailand.

Dependent variable

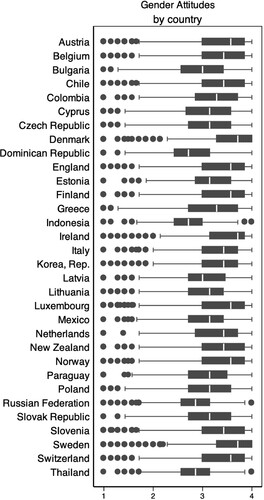

Our dependent variable is an index of attitudes toward gender equality, covering many of the underlying categories suggested by other authors (e.g. Davis and Greenstein Citation2009). The questions we examine measure views of women’s rights and roles in the economy, politics, and the family. Respondents are asked whether they 1 – strongly disagree, 2 – disagree, 3 – agree, or 4 – strongly agree with the following seven statements: (1) Men and women should have equal opportunities to take part in government; (2) Men and women should have the same rights in every way; (3) Women should stay out of politics; (4) When there are not many jobs available, men should have more right to a job than women; (5) Men and women should get equal pay when they are doing the same jobs; (6) Men are better qualified to be political leaders than women; and (7) Women’s first priority should be raising children. These seven items have a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8, indicating good internal consistency.Footnote4 Respondents’ answers are reverse coded when necessary and then averaged, creating a continuous measure ranging from 1 to 4 where higher values indicate more egalitarian gender attitudes. presents the box and whisker plots for each country showing the median (the white line), the interquartile range (the box), upper and lower adjacent valuesFootnote5 (UAV and LAV) (the whiskers), and the number of cases outside the UAV and LAV (the dots outside of the whiskers). Although the overall distribution is skewed toward more gender egalitarianism – as might be expected in a survey fielded after many years of change in women’s condition – variation exists both within and between countries. The Dominican Republic, Indonesia, Russia, and Thailand have the lowest median values on our gender attitude scale, but the median value of all countries is above 2.5, indicating that most of the variation occurs at the upper ranges of the scale. Our analysis focuses on this variation.

Country-level independent variables

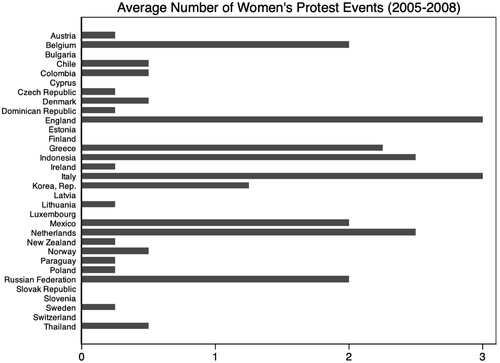

Our main independent variable is the average annual number of women’s protest events, which we operationalize using women’s protest event data collected by Murdie and Peksen (Citation2015).Footnote6 These data, presented in , represent all protests led by or actively involving women reported in Reuters Global News Service every day in a given period in a particular country,Footnote7 which capture protest activities where “woman,” “women,” or “feminist” are explicitly reported as the actors of the events. Because these protests are highly visible actions, covered by major news agencies, our measure is a good proxy for exposure to women’s protests. We use the annual average number of women’s protest events in each country between 2005 and 2008,Footnote8 prior to the fielding of the ICCS survey. England and Italy received the most attention during that period, with an annual average of 10 and 3 women’s protest events, respectively. Because England’s average far exceeded other countries’, we cap England’s number of protest events at 3 in our analyses.Footnote9 Nine countries – Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Switzerland – did not report any women’s protests during this period. Although the use of Reuters News Service means that some – likely smaller – events may be ignored, events reported in Reuters News Service are considered most newsworthy by media within the countries studied, meaning the information is likely to be prevalent in the country. Our measure is not perfect in its operationalization of actual women’s protest activity, but it provides some indication of whether the media provided exposure to the ideas of the women’s protest.

Figure 2. Women’s protests by country. Note: Women’s protest count in England equaled 10 but was capped at 3 (the maximum) for this analysis.

We also control for other national-level variables that might influence gender attitudes. We include a Gender Inequality Index (GII) from the United Nations Human Development Reports (HDR). GII measures gender inequality in three dimensions: maternal health, empowerment, and labor market. We choose this indicator because it focuses on inequality rather than levels of women’s status and because women’s social (as measured by maternal health), political, and economic equality all are likely to influence gender attitudes (Inglehart and Norris Citation2003; Banaszak and Plutzer Citation1993). We expect that the effect of women’s protest changes with levels of women’s equality; therefore, we have an interaction term between the two variables. Lower levels of the GII measure indicate greater gender equality, whereas higher levels indicate greater gender inequality.

We use a dummy variable equaling one for post-communist countries because such countries are unique in their relatively higher gender equality under communism (Pascall and Lewis Citation2004). We also account for regime type based on Polity IV Project, specifically whether the country is a democracy (coded 1), as democracy has been found to influence both gender equality and women’s empowerment (LaFont Citation2001; Lindberg Citation2004). We control for a country’s economic growth by incorporating GDP per capita from the World Bank (2008) in our model because economic modernization has been found to be conducive to gender equality (Adams and Orloff Citation2005).Footnote10 The correlations of all of the national-level variables are available in .

Individual-level independent variables

We expect differences between boys and girls and hence we include a dichotomous measure coded 1 for the girls in the survey.

We also control for indicators that generally predict gender attitudes at the individual level, including socioeconomic status, family type, and religion. We use parents’ education, future educational plans, and exposure to educational resources to measure a student’s socioeconomic status. Mother’s education and father’s education are coded as a seven-category ordinal variable denoting the highest degree of education that the respondents’ mother and father have attained, ranging from 1 – did not finish elementary school to 7 – completed a bachelor’s degree at a college or university, and then averaged over non-missing values.Footnote11 Students’ aspiration for further education is measured by the following question: How many years of further education do you expect to complete after this year? Prospective education is measured by a seven-category variable: coded from 1 – zero years to 7 – more than 10 years. We also include a measure of the educational resources available in the household, namely the number of books a student has at home, which is an ordinal measure coded from 1, indicating that there are no books in the household, to 6, indicating that there are more than 200 books at home. All of these variables are indicative of the socioeconomic status of the student’s family.Footnote12

Additionally, family situations are important for shaping children’s attitudes. We employ measures of household type to control for the environment in which a respondent grows up. Multiple generations are likely to indicate a more traditional family structure, which may influence the students’ gender attitudes. Therefore, we control for respondents living in households with their grandparents. Moreover, households headed by a single mother are likely to generate very different gender role attitudes. Hence, we include a dichotomous measure to indicate this family structure: coded one when it is a single mother household and coded zero when it is not, i.e. when the father is present, both parents are present, or neither parents is present.

Last, we control for respondents’ religious affiliation and activity because religiosity is negatively associated with egalitarian gender attitudes (Morgan Citation1987). Students were asked only one question about religion: how involved they are in a religious group or organization.Footnote13 Their responses are coded as 1 – No, I have never done this, to 3 –Yes, I have done this within the last 12 months.

Because of the nested structure of our data – respondents are sampled within countries – we employ a two-level multi-level model. We model the intercept of the individual-level model as a function of national-level variables with a random component and treat individual-level intercepts as random effects. Additionally, we add a cross-level interaction that examines the effect of women’s protest activity on girls and boys separately.

Results

presents three models: one estimating how women’s protest influences students’ gender attitudes, another one that includes an interaction term between women’s protest and gender of respondents to examine differences in how women’s protests influence boys and girls, and a third one with a three-way interaction between women’s protest, gender, and our measure of gender inequality at the national level.

Table 1. Multi-level model of gender attitudes with women’s protest.

At the individual level, we find strong and significant differences between boys and girls in their support for egalitarian gender roles. Across all levels of women’s protest activity, girls are more supportive of gender equality than their male counterparts, as is indicated by the strength and significance of the dichotomous variable for our female respondents. Model 1 estimates that holding levels of women’s protest constant, girls are on average 0.34 of a point more egalitarian than boys on our gender role index. Thus, we see significant differences between boys and girls even in those nine countries which have no protest events.

We find no support for H1 that women’s protest activity on its own is positively correlated with egalitarian gender roles. As Model 1 in shows, the coefficient for women’s protest events is very small and insignificant, suggesting that gender attitudes of adolescents as a group are not associated with women’s protest activity across all countries. This is true even when all other national-level gender characteristics are dropped from the model. Thus, there is no support for the hypothesis that exposure to women’s protests enhances all adolescents’ egalitarian gender attitudes in the same way across all countries.

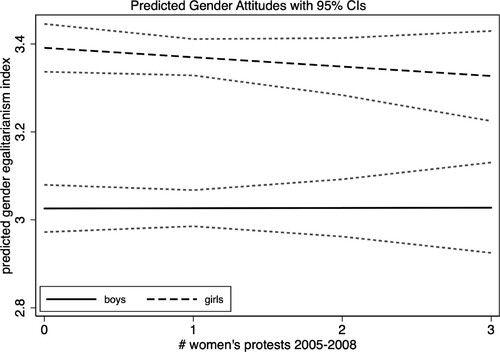

We have competing hypotheses about the interaction between an individual’s gender and women’s protest. Model 2 in allows us to examine these competing hypotheses: H2a and H2b. We find that the interaction is significant but negative. We illustrate the predicted gender egalitarianism for girls and boys from this model over women’s protest in . This figure demonstrates girls’ gender egalitarianism exceeds that of boys at all levels of women’s protest activity. Women’s protest increases boys’ gender egalitarianism very slightly, but there is a reduction in girls’ gender-egalitarian attitudes at the same time, reducing the gap between the sexes. Nevertheless, when we calculate the average marginal effect of protest on gender attitudes for boys and girls, we find that these positive and negative slopes are not statistically significant. The average change in girls’ and boys’ gender attitudes is −0.02 (p = .33) and 0.006 (p = .98), respectively.

These findings suggest that across all countries, women’s protest is associated with a reduced gap between boys’ and girls’ levels of gender egalitarianism, but the effect is not very large, at least over the size of women’s protests in this time period. While our findings contradict our initial hypotheses, we know that girls already have very high support for gender egalitarianism and that the average level of gender inequality is low in most of the countries studied. Potentially, we may be seeing an effect dominated by countries where gender equality has already been achieved. In these countries, girls think that they live in a post-feminist world and react negatively to women’s protest.

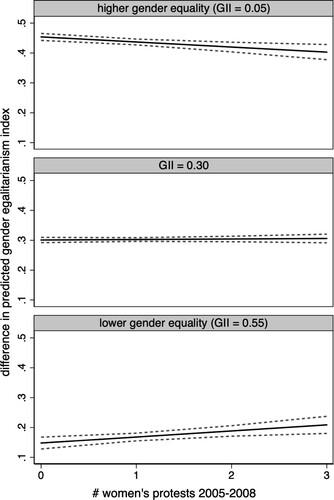

To investigate whether gender equality in a country influences the effect of women’s protest on boys’ and girls’ attitudes toward gender egalitarianism (H3), we turn to Model 3 in . This model shows results from our three-way interaction integrating the potential impact that national level of gender inequality has on how women’s protest relates to girls’ and boys’ gender egalitarianism attitudes.Footnote14 To better understand the three-way interaction model, shows the predicted level of gender egalitarianism for girls and boys over the range of women’s protest events at three levels of gender inequality at the national level. In countries with the lowest levels of gender inequality, we find both boys’ and girls’ level of gender egalitarianism increases as the average number of women’s protest events increases. However, in countries with the highest level of gender inequality, increases in women’s protest are correlated with lower levels of gender-egalitarian attitudes. For instance, in countries, the lowest level of gender inequality (e.g. Denmark, Sweden), boys’ predicted level of gender egalitarianism increases from 3.02 without any women’s protest to 3.13 at the highest level of women’s protest. Similarly, girls’ level of gender egalitarianism increases from 3.49 to 3.55. In countries with the highest level of gender inequality (e.g., Indonesia, Paraguay), boys’ predicted level of gender egalitarianism decreases from 3.07 when there is no women’s protest to 2.81 at the highest level of women’s protest. Similarly, girls’ level of gender egalitarianism decreases from 3.24 to 3.03. Thus, the effect of women’s protest on gender attitudes varies considerably by national gender inequality, and runs counter to our initial hypothesis.

Figure 4. Predicted gender attitudes for girls and boys over protest activity at different levels of national gender inequality (GII=0.05, 0.30, and 0.55).

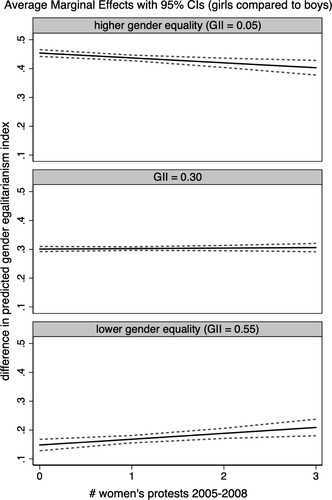

shows how the three-way interaction influences the gap between boys and girls gender egalitarianism by illustrating the marginal effect of girls compared to boys over women’s protest for three levels of national gender inequality. The difference between girls’ and boys’ gender egalitarianism decreases with increasing protest in countries with lower levels of gender inequality, while it increases in countries with higher levels of gender inequality. In countries where there are already high levels of gender equality like Sweden (GII = 0.5), increasing women’s protest reduces the gap in girls’ and boys’ gender egalitarianism from 0.45 to 0.40. In countries with high gender inequality like Indonesia (GII = 0.54), the gap between boys’ and girls’ attitudes actually increases as women’s protest increases from 0.15 to 0.21. Taken together, these results suggest that there are significantly different processes occurring in nations with high inequality and those where there is more gender equality.Footnote15

Conclusion

Although most prior literature on social movement outcomes has focused on policymaking, social movement activists often argue that they care as much about changing the hearts and minds of the public as they do about policy change. Yet, previous studies on how social movement activism affects attitudes focus largely on attitudinal change among adults and is rarely cross-national in scope. We conduct a cross-national analysis of students aged 14–15 to evaluate how exposure to women’s protest in their younger years influences gender attitudes. We show that the average number of women’s protest influences boys’ and girls’ gender egalitarianism, but that the effect is conditional on the status of women in the country. In countries where gender equality is already high, more women’s protest increases adolescents’ gender-egalitarian values and the gap between girls and boys narrows as the number of protests increases. However, the effects are relatively small in both cases. In cases where gender inequality is high, less of a gap exists between boys and girls, but the gap widens as more women’s protest occurs. Moreover, women’s protest reduces slightly the gender egalitarianism of both boys and girls (although less so for girls).

Our tests here are conservative and we argue that the size of these effects, while small, is likely underestimated. Certainly, given all of the influences on adolescent socialization, protest and the underlying movements that are signaled by that protest may be of lesser influence. However, there are several reasons to believe the effects in this analysis are underestimated.

First, because women’s protest activity is episodic, there are likely to be periods when the number of protests far exceed those found in our data; it is possible that stronger positive effects are likely increased more during such episodes. In particular, 2005–2008 was not a period of highly visible women’s protest in many of our countries. It may take intense exposure to women’s protest activity or repeated exposure over more years before this accumulates into changed gender attitudes. Secondly, in countries with higher gender equality, which constitute the bulk of our sample, after decades of women’s protest in many countries, much of the generational change resulting from women’s protest events may already have occurred. As we indicated, the skewness of gender role attitudes toward egalitarianism provides little room for change, especially among girls. A more nuanced measures of gender egalitarianism or a wider range of developing and developed countries might provide for a larger effect. Finally, and most importantly, we have no direct evidence of exposure of the students to the protest, but assume it based on media reports. Additional research that examines direct exposure or focuses on local communities directly exposed to protest might find stronger effects. Given all of these caveats, we believe the effect of women’s protest on gender attitudes warrants further study. In that sense, this study can also serve as an initial step to extended analysis of how protest – and social movements more generally influence attitudes.

We also note the importance of the gender context of each country in determining the effects of women’s protest on gender attitudes. Perhaps our most puzzling result is that gender egalitarianism among boys and girls decreases as the number of women’s protests increases in gender-unequal countries. Several possible explanations exist for the differential effects among countries with varying levels of gender equality. First, the nature of the protest may differ in countries with high and low gender equality. In particular, women who protest in countries with high levels of gender inequality may frame their protests along more traditional values in order to reach a wider array of the population. For example, their protests may emphasize traditional gender roles like motherhood. If women’s protest embraces traditional values, perhaps it channels adolescents’ gender attitudes toward more traditional views, affecting girls less than boys because girls’ personal experiences and interests give them a greater stake in gender egalitarianism. Alternatively, women’s protest may provide similar messages regardless of a country’s level of gender inequality but the media reports on protest may differ or the adolescents’ social networks may filter information about protest in ways that change the message. For example, the media could emphasize women protestors’ traditional family roles or perhaps teachers, parents, or friends denigrate women’s protest to adolescents more in gender-unequal countries. Given that countermovement events go hand in hand with movement events in the US (Banaszak and Ondercin Citation2016a), these adolescents may also be seeing more traditional gender values in gender-unequal countries as women’s protest increases.

In any case, our results demonstrate that the economic development and modernization explanations suggested by Inglehart and Norris (Citation2003) are not the only driving forces behind people’s gender attitudes. Controlling for both economic development and the level of gender inequality, we found an influence of women’s protest on gender attitudes. Since many developed countries also have extensive women’s protests, the cumulative effect of the publicity that comes with the emergence and strengthening of women’s movements may have contributed to changing gender role attitudes, although these have not been given credit for such an effect thus far. In a sense, women’s protests may be an unmeasured confounding variable in most cross-national analyses of gender attitudes.

More importantly, the focus on adolescents helps us deal with some of the problems with endogeneity that influence many studies of adults. In contrast to adults who are also socialized by their experiences in the workplace and family and even may have participated in the women’s protests themselves, our respondents are at the stage where they are formulating their own gender roles and political opinions. These students are not likely to have played any meaningful role in these events. Because the women’s protest events included here occurred one to four years before these 14- and 15-year-old students were asked about their attitudes, it is highly unlikely that we face issues of reverse causality. Although the attitudes developed in childhood do not completely determine adult gender attitudes, our research goes a long way toward suggesting that the experiences of those coming to adulthood during extensive women’s protest may explain increase in the egalitarian gender attitudes we see in many countries. Under this view, those in their impressionable years incorporate new cultural norms into their worldview (see, for example, Hart-Brinson Citation2018).

This article is a first step to examining how exposure to social movements might influence youth attitudes. Our measure of women’s protest – taken from media reports – is also a first attempt to capture citizens’ exposure to women’s protest cross-nationally. The study suggests that being in an environment where women’s protest is normalized may have contributed to the changes in gender attitudes that we have seen over the last 50 years, although sometimes in surprising ways. Moreover, our results demonstrate a need to further contextualize how women’s protests shape youth attitudes. Particularly, in countries like Indonesia, where the population is spread across local contexts and media may be highly differentiated in each area, it will be important to explore within-country variation, in addition to cross-country. All of this suggests that finer measures and additional studies are needed to understand how women’s protest influences gender attitudes.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Spencer Foundation. We thank the reviewers of this journal, as well as participants of the Penn State Social Movement Reading Group and the Newcastle University and Durham University North-East Research Development Workshop for their suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We define women’s protests as protests with women or feminists as key actors. The protest goals can be advancing gender equality, but may also focus on issues unrelated to gender equality.

2 Although boys may also benefit from gender egalitarianism – for example, through expanded future opportunities for spouses or by having a wider array of career options or gender roles – their perceptions of the marginal benefit coming from gender egalitarianism is unlikely to be as strong as for girls.

3 Studies that show children are politically socialized date back to the 1960s (e.g. Greenstein Citation1965; Hess and Easton Citation1960). More recently, Oxley et al.’s (Citation2020) experimental survey of 500 elementary school children in the US finds political orientations begin to form from childhood. Therefore, we see merit in studying the attitudes of adolescents aged 14–15.

4 This reliability varies by country. In 24 countries, the reliability was over 0.7. Two countries had Cronbach’s alpha below 0.6: Mexico (alpha=0.59) and the Dominican Republic (alpha=0.53). The strength of the measure cross-nationally and within most countries as well as the fact that no other subset of measures produces stronger reliability gives us confidence in the measure.

5 The UAV and LAV represent 1.5 times the interquartile range both above and below the first and third quartiles.

6 We use the Murdie and Peksen data over Htun and Weldon’s (Citation2012) coding of women’s movement strength for several reasons. First, the Murdie and Pekson data provide more coverage of the countries within the ICCS data set than the Htun and Weldon data, which is needed to provide statistical power to our multi-level analysis. Second, our paper relies heavily on the transmission of information about women’s protest to the general public; Murdie and Peksen’s data, although no doubt biased toward major events, more accurately represents this process. Htun and Weldon’s strength of the women’s movement measure – collected every decade – focuses more on legitimacy and political influence (Weldon, private communication) – although undoubtedly also includes some aspects of visibility. Because Htun and Weldon’s data were measured in 2005 and represent movement strength over the previous decade, they also lie further back in time, which is problematic given the young age of our respondents. The correlation between the two measures is modest (r=0.36), but our robustness check shows the coefficients remain in the expected direction, although several lose statistical significance with fewer countries in the analysis.

7 We acknowledge that the use of Reuters, like other news sources, introduces bias to our measure of women’s protests (e.g. Andrews and Caren Citation2010) likely based on size and proximity to reporters among other factors. We argue that this bias is less problematic in discussing how movement events influence public opinion, since most adolescents experience women’s protests through reported events or indirectly through the discussion of those reported events in schools, their families, and their social networks. Although concerns about the bias of events are important when examining what explains events, using a measure that does not separate out the reporting from the actual activity reflects the causal mechanism in this case.

8 These are the preadolescent years when our respondents begin to enter adolescence – a stage when preadolescents start to form opinions about politics, religion, sexuality, and gender roles according to psychologists (Egan and Perry Citation2001; Halim and Ruble Citation2010).

9 Alternative specifications including models where England is coded at 10, the number of protests is summed rather than averaged, a log of protest events is used, and a dichotomous measure for women’s protests are reported in . All find similar effects of women’s protest and its interaction with gender.

10 For a robustness check, we control for a country’s religious context using the percentage of Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox adherents in the respondent’s country taken from the World Religion Dataset (2005). Because most countries in our data set are European and Latin American, several countries have a population of more than 40% of either Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox adherents, majority of Islamic adherents. Results using the measure of very traditional Christian religions are shown in Model 1 of .

11 Ideally, we would use mother’s education as a baseline model to analyze how adolescents’ gender role attitudes are affected by their mother’s educational level. However, including mother’s and father’s education separately excludes respondents whose mother’s or father’s education information is missing. Thus, we take an average of parents’ education instead to ensure that respondents who come from family different structures are included in the sample. Our robustness check displayed in indicates separating mother’s education and father’s education yields similar results to averaging parents’ educational backgrounds as in the main model. Moreover, the more educated mothers and fathers are, the more egalitarian are respondents’ gender attitudes, although the effect of mothers’ education is slightly stronger than fathers’.

12 Our level 1 model includes most of the standard measures of the individual-level studies. We do not have mother’s employment status or parental gender attitudes because the ICCS asks the respondents few questions about students’ parents. In multi-level models, an aggregate-level variable may affect another aggregate-level variable and an individual-level variable may affect other individual-level variables. However, the omission of individual-level variables does not bias the coefficient estimates of aggregate-level variables (Krull and MacKinnon Citation2001). Thus, the exclusion of the mother’s employment status should not affect our conclusions about women’s protest.

13 The ICCS does not ask students whether the organization is in or outside of school, but the nature of the question ordering implies that it could be either.

14 For three-way interactions, scholars need to include all the component variables including interactions (Brambor, Clark, and Golder Citation2006). Therefore, in addition to gender, women’s protest, women’s protest interacted with respondent gender, and gender inequality in Model 2, we include in Model 3 gender inequality interacted with women’s protest, respondent gender interacted with national gender inequality, and the three-way interaction of respondent gender, women’s protest and women’s inequality.

15 See the Appendix for further analysis of the correlations between our control variables and gender role attitudes.

References

- Adams, J, and A S Orloff. 2005. “Defending modernity? High politics, feminist anti-modernism, and the place of gender.” Politics and Gender 1 (1): 166.

- Alexander, A. C., and H. Coffé. 2018. “Women’s Political Empowerment Through Public Opinion Research.” In Measuring Women’s Political Empowerment Across the Globe, edited by Amy C. Alexander, Catherine Bolzendahl, and Farida Jalalzai, 27–53. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Alexander, J. C., R. Eyerman, B. Giesen, N. J. Smelser, and P. Sztompka. 2004. Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Amenta, E., N. Caren, E. Chiarello, and Y. Su. 2010. “The Political Consequences of Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 36: 287–307.

- Andrews, K. T., and N. Caren. 2010. “Making the News: Movement Organizations, Media Attention, and the Public Agenda.” American Sociological Review 75 (6): 841–866.

- Aronson, P. 2008. “The Markers and Meanings of Growing up: Contemporary Young Women's Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood.” Gender & Society 22 (1): 56–82.

- Banaszak, L. A., and H. L. Ondercin. 2016a. “Explaining the Dynamics Between the Women's Movement and the Conservative Movement in the United States.” Social Forces 95 (1): 381–410.

- Banaszak, L. A., and H. L. Ondercin. 2016. “Public Opinion as a Movement Outcome: The Case of the US Women's Movement.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 21 (3): 361–378.

- Banaszak, L. A., and E. Plutzer. 1993. “Contextual Determinants of Feminist Attitudes: National and Subnational Influences in Western Europe.” American Political Science Review 87 (1): 147–157.

- Bartini, M. 2006. “Gender Role Flexibility in Early Adolescence: Developmental Change in Attitudes, Self-Perceptions, and Behaviors.” Sex Roles 55 (3–4): 233–245.

- Beaman, L., C. Raghabendra, D. Esther, P. Rohini, and P. Topalova. 2009. “Powerful Women: Does Exposure Reduce Bias?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124 (4): 1497–1540.

- Brambor, T., W. R. Clark, and M. Golder. 2006. “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses.” Political Analysis 14 (1): 63–82.

- Branton, R., V. Martinez-Ebers, T. E. Carey, and T. Matsubayashi. 2015. “Social Protest and Policy Attitudes: The Case of the 2006 Immigrant Rallies.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 390–402.

- Brown, C. S., B. O. Alabi, V. W. Huynh, and C. L. Masten. 2011. “Ethnicity and Gender in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence: Group Identity and Awareness of Bias.” Developmental Psychology 47 (2): 463.

- Bullock, J. G. 2011. “Elite Influence on Public Opinion in an Informed Electorate.” American Political Science Review 105 (3): 496–515.

- Burns, N., and K. Gallagher. 2010. “Public Opinion on Gender Issues: The Politics of Equity and Roles.” Annual Review of Political Science 13 (1): 425–443.

- Clayton, A. 2014. “Electoral gender quotas and attitudes toward traditional leaders: A policy experiment in Lesotho.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 33 (4): 1007–1026.

- Cribb, V., and A. Haase. 2016. “Girls Feeling Good at School: School Gender Environment, Internalization and Awareness of Socio-cultural Attitudes Associations with Self-esteem in Adolescent Girls.” Journal of Adolescence 46: 107–114.

- Davis, S. 2007. “Gender Ideology Construction from Adolescence to Young Adulthood.” Social Science Research 36 (3): 1021–1041.

- Davis, S., and T. Greenstein. 2009. “Gender Ideology: Components, Predictors, and Consequences.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 87–105.

- De Volo, L. B. 2004. “Mobilizing Mothers for War: Cross-national Framing Strategies in Nicaragua’s Contra War.” Gender & Society 18 (6): 715–734.

- Efty, Alex. 1992. “Human Chain of Cypriot Women Protests Turkish Occupation.” AP News. https://apnews.com/ab4345aa0be3c14d24dcdb990696c988. Accessed July 24, 2020.

- Egan, S., and D. Perry. 2001. “Gender Identity: A Multidimensional Analysis with Implications for Psychosocial Adjustment.” Developmental Psychology 37 (4): 451.

- Freiner, N. 2013. “Mobilizing Mothers: The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Catastrophe and Environmental Activism in Japan.” ASIANetwork Exchange 21 (1): 1–15.

- Gadallah, M., R. Roushdy, and M. Sieverding. 2017. “Young People’s Gender Role Attitudes over the Transition to Adulthood in Egypt.” Economic Research Forum Working Papers (No. 1122).

- Greenstein, F. 1965. Children and Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Grusec, J., and P. D. Hastings, eds. 2014. Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Halim, M. L., and D. Ruble. 2010. “Gender Identity and Stereotyping in Early and Middle Childhood.” In Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology, edited by Joan C. Chrisler and Donald R. McCreary, 495–525. New York: Springer.

- Hart-Brinson, P. 2018. The gay marriage generation: How the LGBTQ movement transformed American culture. NYU Press.

- Hassim, Shireen, and Amanda Gouws. 1998. “Redefining the Public Space: Women’s Organisations, Gender Consciousness and Civil Society in South Africa.” Politikon 25 (2): 53–76.

- Hess, R. D., and D. Easton. 1960. “The Child's Changing Image of the President.” Public Opinion Quarterly 24 (4): 632–644.

- Htun, M., and S. L. Weldon. 2012. “The Civic Origins of Progressive Policy Change: Combating Violence Against Women in Global Perspective, 1975–2005.” American Political Science Review 106 (3): 548–569.

- Inglehart, R., and P. Norris. 2003. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jennings, M. K. 2002. “Generation Units and the Student Protest Movement in the United States: An Intra-and Intergenerational Analysis.” Political Psychology 23 (2): 303–324.

- Jennings, M. K., and G. Markus. 1984. “Partisan Orientations Over the Long Haul: Results from the Three-wave Political Socialization Panel Study.” American Political Science Review 78 (4): 1000–1018.

- Jennings, M. K., and R. Niemi. 2014. Generations and Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Jennings, M. K., and R. Niemi. 2015. Political Character of Adolescence: The Influence of Families and Schools. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kallio, K., and J. Häkli. 2011. “Tracing Children’s Politics.” Political Geography 30 (2): 99–109.

- Klatch, R. E. 2001. “The Formation of Feminist Consciousness among Left- and Right-Wing Activists of the 1960s.” Gender & Society 15 (6): 791–815.

- Krull, J. L., and D. P. MacKinnon. 2001. “Multilevel Modeling of Individual and Group Level Mediated Effects.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 36 (2): 249–277.

- LaFont, S. 2001. “One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: Women in the Post-Communist States.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 34 (2): 203–220.

- Levinsen, K., and C. Yndigegn. 2015. “Political Discussions with Family and Friends: Exploring the Impact of Political Distance.” The Sociological Review 63: 72–91.

- Lieberfeld, D. 2009. “Parental protest, public opinion, and war termination: Israel's �Four Mothers� movement.” Social Movement Studies 8 (4): 375–392.

- Lindberg, S. 2004. “Women’s Empowerment and Democratization: The Effects of Electoral Systems, Participation, and Experience in Africa.” Studies in Comparative International Development 39 (1): 28–53.

- Liu, S. J. S. 2018. “Are Female Political Leaders Role Models? Lessons from Asia.” Political Research Quarterly 71 (2): 255–269.

- Liu, S. J. S., and L. A. Banaszak. 2017. “Do Government Positions Held by Women Matter? A Cross-national Examination of Female Ministers’ Impacts on Women's Political Participation.” Politics & Gender 13 (1): 132–162.

- Martin, C., and D. Ruble. 2010. “Patterns of Gender Development.” Annual Review of Psychology 61: 353–381.

- McAdam, D. 1990. Freedom Summer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moghadam, Valentine, and Fatima Sadiqi. 2006. “Women’s Activism and the Public Sphere: An Introduction and Overview.” Journal of Middle East Women's Studies 2 (2): 1–7.

- Morgan, M. 1987. “The Impact of Religion on Gender-Role Attitudes.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 11 (3): 301–310.

- Morgan, Miranda. 2017. “Women, Gender and Protest: Contesting Oil Palm Plantation Expansion in Indonesia.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (6): 1177–1196.

- Morgan, J., and M. Buice. 2013. “Latin American Attitudes Toward Women in Politics: The Influence of Elite Cues, Female Advancement, and Individual Characteristics.” American Political Science Review 107 (4): 644–662.

- Murdie, A., and D. Peksen. 2015. “Women and Contentious Politics: A Global Event-data Approach to Understanding Women’s Protest.” Political Research Quarterly 68 (1): 180–192.

- Neff, K. D., C. E. Cooper, and A. L. Woodruff. 2007. “Children’s and Adolescents’ Developing Perceptions of Gender Inequality.” Social Development 16 (4): 682–699.

- Oxley, Z. M., M. R. Holman, J. S. Greenlee, A. L. Bos, and J. C. Lay. 2020. “Children’s Views of the President.” Public Opinion Quarterly 84 (1): 141–157.

- Pascall, G., and J. Lewis. 2004. “Emerging Gender Regimes and Policies for Gender Equality in a Wider Europe.” Journal of Social Policy 33 (3): 373–394.

- Quintelier, E. 2015. “Engaging Adolescents in Politics: The Longitudinal Effect of Political Socialization Agents.” Youth & Society 47 (1): 51–69.

- Raviv, A., A. Sadeh, A. Raviv, O. Silberstein, and O. Diver. 2000. “Young Israelis’ Reactions to National Trauma: The Rabin Assassination and Terror Attacks.” Political Psychology 21 (2): 299–322.

- Rudman, L., and S. Goodwin. 2004. “Gender Differences in Automatic In-group Bias: Why Do Women Like Women More Than Men Like Men?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87 (4): 494.

- Sadiqi, Fatima, and Moha Ennaji. 2006. “The Feminization of Public Space: Women’s Activism, the Family Law, and Social Change in Morocco.” Journal of Middle East Women's Studies 2 (2): 86–114.

- Salime, Zakia. 2012. “A New Feminism? Gender Dynamics in Morocco’s February 20th Movement.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 13: 101.

- Schnittker, J., J. Freese, and B. Powell. 2003. “Who Are Feminists and What Do They Believe? The Role of Generations.” American Sociological Review 68 (4): 607–622.

- Smetana, J. G., J. Robinson, and W. M. Rote. 2015. “Socialization in Adolescence.” In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research, edited by Grusec J.E. and Hastings, 60–84. New York.

- Tripp, Aili Mari, Isabel Casimiro, Joy Kwesiga, and Alice Mungwa. 2008. African Women’s Movements: Transforming Political Landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Valentim, V. 2019. “Creating Critical Citizens? Anti-Austerity Protests and Public Opinion”. (May 20, 2019). Available at SRN.

- Whittier, N. 1997. “Political Generations, Micro-cohorts, and the Transformation of Social Movements.” American Sociological Review 62 (5): 760–778.

- Wolbrecht, C., and D. Campbell. 2007. “Leading by Example: Female Members of Parliament as Political Role Models.” American Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 921–939.

- Wray-Lake, L., C. Flanagan, and D. W. Osgood. 2010. “Examining Trends in Adolescent Environmental Attitudes, Beliefs, and Behaviors Across Three Decades.” Environment and Behavior 42 (1): 61–85.

- Youniss, J., S. Bales, V. Christmas-Best, M. Diversi, M. McLaughlin, and R. Silbereisen. 2002. “Youth Civic Engagement in the Twenty-first Century.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 12 (1): 121–148.

Appendix

Table A1. Summary descriptive statistics of variables.

Table A2. Correlation coefficients for the national-level variables.

Table A3. Multi-level model of gender attitudes with women’s protests, including national religion, women’s political rights, and democracy and excluding non-democracy.

Table A4. Multi-level model of gender attitudes with women’s protests, with separated mother’s and father’s education

Table A5. Multi-level model of gender attitudes with different women’s protest measures.

Correlations between control variables and gender attitudes

The individual-level and national-level control variables show strong consistency in all three models. The individual-level control variables are all significant and signed in the expected direction. The three measures of socioeconomic status – parents’ education, students’ educational aspirations, and the number of books students have at home—are positively related to the gender egalitarianism index at the 0.05 statistical significance level. Students who grow up in single mother households have more egalitarian gender role attitudes than those who grow up in households with both parents in the household or who are raised by a single father. Students who are immersed in an environment of traditional family – as measured by whether the grandparents are at home – are less gender egalitarian even when exposed to women’s protests as are students who are members in a religious organization. Among the country-level variables, GDP per capita and democracy are signed in the expected direction with democratic countries and those with higher GDP per capita having higher levels of egalitarian gender attitudes. The coefficient for post-communist regimes is significant and negative, indicating, ceteris paribus, adolescents in these countries are less egalitarian in their gender role attitudes than individuals in other countries.