?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Far right parties often attack efforts to promote equality for historically marginalized groups like women, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQIA+ people, suggesting that “identity politics” takes away valuable resources from native working class populations. Do mainstream parties respond to far right challenges by shifting which groups in society they give attention to? Our main argument is that mainstream parties facing a rising far right party accommodate by de-emphasizing historically marginalized identity groups and emphasizing the working class. Using a mixed methods approach, we demonstrate that mainstream parties threatened by the far right shift positive attention away from non-economic identity groups and towards the working class. Their response is conditioned by party ideology (Social Democratic parties driving the decline) and electoral fortunes. Qualitative evidence from Denmark and Sweden sheds light on how far right party growth is shifting the content of manifestos: we find that mainstream parties threatened by the far right increasingly sideline ascriptive identity-related issues. When they do give attention to identity groups like women, it is often to promote nativist, anti-immigrant agendas.

Far right parties, characterized by a nativist mix of anti-immigration and nationalism, have increasingly gained seats in parliaments across Europe and participated in multiple government coalitions. Over time, these parties have been expanding beyond their core issue of immigration and focusing attention on other identity groups, including women, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQIA+ people (Abou-Chadi, Breyer, and Gessler Citation2021; Meguid et al. Citation2022 ). Far right political discourse often attacks efforts to promote equality for historically marginalized groups, such as feminism, gender and queer theory, and post-colonialism, suggesting that these ideologies and associated policies take away valuable resources from native working class populations (Bernardez-Rodal, Requeijo Rey, and Franco Citation2022; Paternotte and Kuhar Citation2018; Sakki and Pettersson Citation2016). Concurrently, mainstream parties have been criticized for their focus on “identity politics,” with political commentators suggesting that by giving attention to these issues they lose valuable working class votes to the far right.Footnote1 Against this context, we evaluate how far right challenges impact mainstream party attention to different identity groups. Do mainstream parties under threat from the far right shift their attention away from historically marginalized groups like women and ethnic minorities, in favor of a renewed focus on the working class?

Multiple studies show that mainstream political parties are responsive to far right growth, generally by moving towards the far right position in an accommodative strategy (Meguid Citation2008). Facing far right threat, mainstream parties shift their positions on immigration and multiculturalism (e.g., Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020; Bale Citation2003), and their emphasis on welfare (Schumacher and Van Kersbergen Citation2016; Krause and Giebler Citation2020), especially center-left parties. Yet, we know little about whether and how mainstream parties respond to far right challengers in terms of which groups in society they give attention to. Redressing this gap, we outline and test three hypotheses: we expect parties to accommodate the grievances of far right parties by de-emphasizing non-economic identity groups and shifting attention to the working class. Additionally, we expect the response of mainstream parties to be conditioned by party ideology (with Social Democratic parties in particular decreasing attention to non-economic identity groups) and electoral fortunes.

We conduct a mixed-methods analysis of party manifestos, using data from both the Comparative Manifesto Project (MP; Volkens et al. Citation2019) and our own hand-coded analysis of party manifestos. The quantitative data includes 89 parties in 23 European countries from 1984 to 2017. We supplement this analysis with a qualitative study of parties in two matched countries similar in most respects except patterns of far right growth (Denmark and Sweden). We find evidence that mainstream parties accommodate: when faced with a far right challenge, they shift positive attention away from non-economic identity groups and towards the working class. Social Democratic parties drive the shift away from progressive identity politics positions, a finding consistent with research on the positioning of these parties on other issues (e.g., Benedetto, Hix, and Mastrorocco Citation2019; Abou-Chadi and Wagner Citation2019). Qualitative analysis sheds light on how the content of party agendas changes. Mainstream parties in Denmark (which saw the rise of a far right party in 1998) but not Sweden (no significant far right party in this period) increasingly sideline identity-related issues, particularly those relating to women and gender. When Danish parties do discuss identity groups like women, it is primarily to support growing nativist agendas. Additionally, following the rise of a far right party in Sweden from 2010, we witness a similar pattern among mainstream parties.

Mainstream response to far right parties

Research finds that mainstream parties on the left and right react when challenged by far right parties, and their responses are conditioned by factors including past electoral performance and internal party unity (Bale et al. Citation2010; Van Spanje Citation2010; Han Citation2015; Abou-Chadi Citation2016). Existing studies focus primarily on how far right parties affect mainstream positions on immigration (Schain Citation2006; Abou-Chadi Citation2016; Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020), but recent studies also examine the effect of the far right on attention to other issues like welfare. Increasingly, far right parties embrace welfare chauvinism (support for high welfare benefits for native groups only) (Enggist and Pinggera Citation2022), and a growing share of workers vote for these parties (De Lange Citation2016). For example, in Denmark the populist right adopted a platform of welfare dualism which ultimately led to a “two-tier welfare state” implemented under right-wing government (Bay, Finseraas, and Pedersen Citation2013, 202). Research demonstrates that mainstream parties follow populist welfare chauvinist positions under certain circumstances (Schumacher and Van Kersbergen Citation2016), and left-of-center parties are especially likely to adopt leftist welfare positions when challenged by the far right (Krause and Giebler Citation2020).

Our contribution is to broaden the scope of the existing literature by exploring whether and how mainstream parties respond to the far right on the issue of identity politics. Although all politics involving group-based concerns could be considered “identity politics”, for the sake of this paper we refer to the common usage: “promoting the interests of a wide variety of marginalized groups, such as ethnic minorities, immigrants and refugees, women, and LGBT people” (Fukuyama Citation2018). This kind of identity politics is seen as distinct from class-based politics, which arise from economic issues rather than ascriptive group identity (Bernstein Citation2005; Noury and Roland Citation2020).

In the last five decades, a consensus emerged within mainstream parties that equality-seeking policies around gender, sexuality, and other non-economic characteristics were worthy of pursuit, especially among leftist parties (Inglehart and Norris Citation2003; Annesley, Engeli, and Gains Citation2015). Far right parties challenge this consensus (Piscopo and Walsh Citation2020). Opposition to gender equality and related issues has been identified as the “symbolic glue” that binds a series of interconnected appeals by far-right political actors—a strategy of “anti-genderism” (Kováts and Põim Citation2015). As Erel notes, far right actors use this discourse, “to center white, heterosexual hegemonic masculinities and specific versions of femininities proclaimed to be ‘traditional’ as protecting the future of the nation ,” in an argument linked to nativism within historically white societies (Erel Citation2018, p.173).

In this view, mainstream parties are seen to have pursued equality-seeking measures for ascriptive groups at the expense of economically-grounded social class groups. The figure of the “left behind” embodies this perspective, signifying the increasingly economically and socially vulnerable working class, the so-called losers of modernization who become politically alienated as a result (Ignazi Citation1992; Gidron and Hall Citation2017; Dancygier Citation2020). Those who previously relied on traditional gender or ethnic hierarchies to bolster their own self-worth now suffer from relative status decline, and feelings of marginalization make them more likely to support parties outside the mainstream (Gidron and Hall, Citation2017, Citation2020).

Although “identity politics” includes many different ascriptive groups, mainstream political actors perceive them to be linked in this context—and often in tension with the interests of the working class. For example, in 2021 the former vice-president of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), Wolfgang Thierse, published an opinion-editorial criticizing the party for letting, “questions of ethnic, gender and sexual identity dominate,” at the expense of issues of distributive justice.Footnote2 In the U.K., Labour Party politician Stephen Kinnock argued that the party had made a mistake by having “played the game of identity politics and identified groups, whether it is by ethnicity or sexuality or whatever you might want to call it, rather than say, ‘we stand up for everyone in this country and that includes you, the white working class’.”Footnote3 A similar framing is seen in the cases of Denmark,Footnote4 Sweden,Footnote5 and France to name a few.Footnote6

Theory: far right strength decreases mainstream party attention to “identity politics”

Following Meguid's modified spatial theory (Meguid Citation2005, Citation2008), there are three main strategies parties could take: accommodative, adversarial, or dismissive. Adversarial strategies involve adopting different positions than the niche parties, while accommodating entails adopting the same position. Parties could also simply ignore the far right (dismissive) and refuse to take a position or give attention to the issue. Unlike the context of position-taking on emerging issues such as immigration, the issues we focus on are not new to mainstream parties. Social democratic parties are fundamentally linked to the working class, and left-wing parties are associated with gender equality. The dismissive strategy is thus less relevant to our story, given the salience of these issues in the party systems we study and the attendant risk of appearing out-of-touch to voters. The question is whether mainstream parties will strategically highlight or downplay attention to different identity groups.Footnote7

Our main argument is that mainstream parties threatened by the rising far right accommodate in the hopes of stopping the loss of voters to a threatening new competitor. The adversarial strategy—increasing positive attention to identity politics—is too risky for parties that are directly threatened by the far right. Far right parties “steal” voters from both the center-left (the “left behind” working class) and right (socially conservative or anti-immigrant) (e.g., Spoon and Klüver Citation2019). While the adversarial strategy might benefit Green or New Left parties which do not compete with the far right for voters, if mainstream parties responded this way it could further encourage vote loss to the far right. This puts mainstream parties under pressure to adapt their views, and reconsider which groups in society they focus on—in the same way that research shows they have responded to far right challenges on immigration and welfare. The benefits of an accommodative strategy are not only halting vote loss to the far right but also potentially attracting some of their voters. We thus expect mainstream parties to recalibrate their attention as follows:

H1: Far right party growth decreases mainstream party attention to non-economic identity groups, while increasing positive attention to the working class.

We also expect ideology to condition the responses of mainstream parties in important ways. Social Democratic parties are uniquely placed to feel the identity-based pressure of a far right challenge, having roots in the historic working class but also positive commitments on issues of equality for non-economic groups. In the context of broader dealignment, traditional patterns of voting whereby those from lower socio-economic backgrounds tended to vote for left parties are changing, and voters are seeking out alternatives from the converging mainstream (Elff Citation2007; Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015). Far right parties are also shifting towards the preferences of their now more left-leaning supporters, as recent research confirms that far right parties in government are less likely to engage in welfare state retrenchment and deregulation, compared to right-wing parties alone (Röth, Afonso, and Spies Citation2018). Center-left parties are therefore faced with the dilemma of accommodation especially acutely in light of a “public narrative [that] strongly focuses on the parties' supposedly dwindling support among its traditional base, the working class” (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Citation2019, 1405). Consequently, our second hypothesis is:

H2: The link between far right growth and mainstream priorities is conditioned by party ideology, with Social Democratic parties likely to decrease positive attention to non-economic identity groups when threatened by the far right.

Finally, we expect recent electoral fortunes to condition party response. Previous research suggests that parties shift their policies more when they are losing votes (Somer-Topcu Citation2009; Han Citation2015). Other research suggests that mainstream party convergence results in a loss of voters to non-mainstream parties (Spoon and Klüver Citation2019), highlighting the incentive to shift away from any perceived mainstream consensus on increasingly high-profile issues. Indeed, this relates to H2 as social democratic parties have been shown to be in decline across the period under study (Benedetto, Hix, and Mastrorocco Citation2019). Consequently, if a party is in decline, we expect it is more likely to accommodate identity-based concerns raised by the far right than parties in a strong electoral position:

H3: The link between far right growth and mainstream priorities is conditioned by party fortunes, with parties losing votes more likely to increase positive attention to the working class while decreasing positive attention to identity than those in strong electoral positions.

Data and methods

We analyze party priorities using both quantitative and qualitative methods. First, we leverage Comparative Manifesto Project (MP) data, which measures attention to issues in the party's manifesto, coding sentences or quasi-sentences by topic.Footnote8 The percentage of manifesto devoted to each topic is taken as a measure of the party's policy priorities (Volkens et al. Citation2019). Manifestos represent a crucial early state of the policy process: agenda-setting. While all voters might not read them, manifestos nonetheless provide a program for parties to follow and a clear record to which parties can be held accountable. Manifestos also set the topics of political discussion in a society—which issues are deemed worthy of inclusion? The attention that different identity groups are afforded in party agendas has important implications for the quality of representation afforded to these groups.

The MP data has been criticized for its validity and reliability, in particular for how it estimates policy positions (not our focus here). Still, it remains the richest time-series data available for measuring parties' relative attention to different issues and groups in society. Noting these problems, in the second part of the paper we undertake a qualitative analysis of party manifestos in two countries (Sweden and Denmark), manually coding manifestos for attention to different “identity politics” issues.

Our argument poses a relationship between the strength of far right parties and mainstream party attention to historically marginalized identity groups versus the working class. The concern for causal inference is that countries which see far right parties emerge may be self-selecting. For example, countries where far right parties do well might be characterized by different culture or attitudes towards equality, and these underlying attitudes might also influence party priorities.

To address this potential endogeneity problem, the quantitative analysis estimates regression models that include party- (which in linear combination are equal to country-) and year fixed effects. Our models control for party or country-specific omitted variables that are constant over time (e.g., party culture, religiosity), and any time-specific variables that are constant across countries (e.g., economic shocks). Two-way fixed effects models are closely related to the difference-in-difference identification strategy, which compares “treated” (here, parties in countries with far right parties) and “control” units (parties in countries without far right parties) within the same time period. The continuous “treatment” variable in this case (vote share of far right party) means that we measure the “bite” or intensity of far right parties, but the regression formula retains the basic features of a difference-in-differences model (Pischke Citation2005).

The baseline model with party and year fixed effects can be written as where

is the outcome of interest and measures party priorities in party i in the year t;

is a continuous variable indicating vote share of the far right, and

is the coefficient for this main independent variable;

represents a vector of covariates, and

the coefficients for these covariates;

and

are party and year fixed effects, respectively; and

is the error term. Right-hand side variables are lagged because party manifestos are written before the election. Party-level variables are lagged by one-election year and national-level variables are lagged by one year. We use robust standard errors clustered by election to address the concern that unobserved election-specific factors may influence all parties' policy priorities in a given election, leading to correlated errors across parties (Williams Citation2000).

The quantitative data includes 89 parties in 23 European democracies with and without far right parties from 1984 to 2017. We focus on Europe because of the general agreement that far right parties have become increasingly prominent here since the 1980s. However, the majority of our data come from Western Europe (411 of 460 observations), due to data availability. The countries included are: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK. Parties are coded as far right based on nativist ideology, as reflected in categorizations by C. Mudde (Citation2007), C. Mudde (Citation2016), or Bustikova (Citation2014) (more on this below). Parties are coded as mainstream if the Comparative Manifesto Project categorizes them as Social Democratic, Liberal, Conservative, or Christian Democratic. Following Abou-Chadi and Krause (Citation2020), we drop the first three elections after democratization for countries in Eastern Europe, given the time necessary to establish party systems.

The main dependent variables are the share of party manifesto devoted to two policy categories: (1) Identity Groups, which measures attention to identity groups not defined by class; and (2) Working Class, which measures support for class-based groups. Identity Groups adds MP codes 705 and 706 and includes positive mentions of non-economic identity groups of all kinds, including women, disabled peoples, LGBTQIA+, immigrants, indigenous, the elderly, and children. For example, “The investment in women's businesses continues” (Swedish Moderates 2010, coded as 706). Working class includes favorable mentions to labor groups and the working class, including more jobs, good working conditions, and fair wages (code 701). For example, “the unskilled should be entitled to a real education on full unemployment benefit” (Danish Social Democrats 2011). While imperfect, the economic and non-economic identity group variables coded by MP give us a good proxy for class versus identity politics. The qualitative analysis serves as both a robustness check and illustrates how parties respond to the rise of far right parties.

The key independent variable is , a continuous variable indicating the strength (vote share) of far right parties. If a country had more than one far right party, the sum of vote shares is used to measure the overall strength of far right parties. Appendix Table A1 lists all far right parties included, and a discussion of criteria for inclusion (we focus on parties characterized by nativist ideology). We control for several potential confounders. First, growing levels of immigration might spur xenophobia and cultural backlash, leading to the growth of both far right parties and changes in mainstream party attention to identity groups. Evidence on the link between immigration and far right party success is mixed, but some studies find a positive link (e.g., Coffé, Heyndels, and Vermeir Citation2007). To control for this we include

, measured as the log of foreign inflows of asylum seekers.

Another common theory for far right growth relates to economic deprivation—that changing labor markets and greater economic insecurity lead to less support for immigrants in line with conflict theory (Kitschelt and McGann Citation1997)—and may also bleed into less support for women and other historically disadvantaged groups. Again, the empirical evidence is mixed (for a review see Golder Citation2016), but we include measures of and

(to account for economic insecurity. Finally, supply-side explanations for far right growth often highlight the role of electoral systems, in particular how majoritarian systems serve as a bulwark against far right party entry (John and Margetts Citation2009). Because electoral rules are mostly static, the party fixed effects we include account for this.

Other controls include (vote share), whether a party was in

during the previous election period, and the average

of the dependent variable. Research shows that opposition parties are more vulnerable to far right “contagion” than parties in government (Van Spanje Citation2010), and that small parties follow different incentives to larger parties (Adams et al. Citation2006). Additionally, parties might respond to the issue emphases of other parties in the party system (Green-Pedersen and Mortensen Citation2010; Meijers Citation2017). We, therefore, include variables capturing the average party system salience of the dependent variables. Table A2 in the Appendix shows summary statistics and data sources for all variables used in analysis.

Results

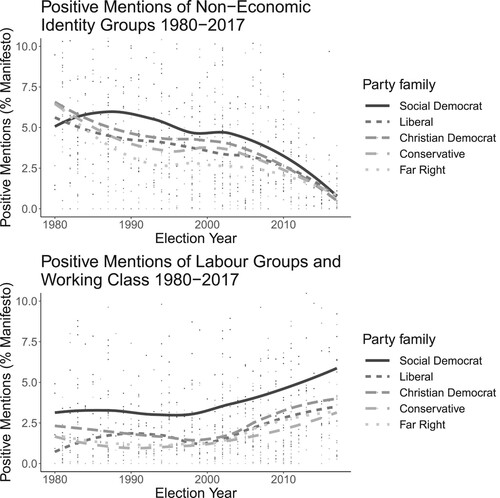

Figure plots party attention to identity groups and the working class from 1980 to 2018 by party family. The figure shows a steady decline in positive attention to non-economic identity groups for all party families. Social Democrats historically paid the most attention to identity groups, but in recent years are indistinguishable from other party families. The far right pays the least positive attention to non-economic identity groups. Attention to the working class is almost a mirror opposite, with all party families increasing attention since the early 2000s. This increase intensifies in the late 2000s, concomitant with the 2008 financial crisis. Social Democratic parties continue to increase their attention to the working class while Christian Democrat, Liberal, and far right parties are trending towards a plateau. Overall, the patterns here suggest that parties have been shifting attention away from non-economic and towards economic identity groups.

Table reports results showing the effects of far right party growth on party priorities towards identity groups and the working class. Consistent with Hypothesis 1 (accommodation), far right party growth leads mainstream parties to shift their priorities away from identity groups and towards the working class. The coefficient of on

in Model 1 indicates that a one-unit increase in vote share of far right parties is associated with an 0.11 percentage point decrease in party attention to identity groups, significant at the 0.1 level. For example, if a party spent 5% of its manifesto on issues related to identity groups, a 5% increase in far right party growth would lead the party to decrease its attention by 0.55 points, to 4.45% of the party manifesto (for context, the standard deviation of far right vote share in our data is 7.8%).

Table 1. Effects of far right party on mainstream party priorities.

The opposite is seen for attention to the working class. Table model 2 shows that far right party growth increases mainstream party attention to this group (p < 0.05). A party that spent 5% of its manifesto on issues related to the working class would be expected to spend 5.5% of its manifesto on these issues if the far right increased from 0% to 5% of vote share. We also test whether mainstream parties react to far right attention to the working class in particular (measured as share of far right manifesto devoted to working class). We find that mainstream attention to the working class increases significantly as far right parties themselves give more attention to the working class. To save space, these results are shown in Table A5 and Figure A1.

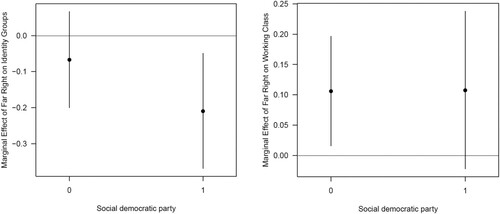

The next hypothesis (H2) is that the effect of far right growth on party priorities is conditional on party ideology, with Social Democrats particularly likely to accommodate the far right. To test this, we estimate models including interactions with party growth and social democratic party family. Note that the constitutive term for this party family cannot be included in the model due to the inclusion of party-level fixed effects; this also means that it is fully accounted for in the models. Because it can be difficult to interpret the coefficients of interactive models, Figure plots the marginal effects, the change in party priorities in response to far right growth and party family (social democratic, or not) (see Appendix Table A3 for regression table) (Brambor, Roberts Clark, and Golder Citation2006). The figure suggests that the negative effect of far right growth on mainstream attention to identity groups is driven by Social Democrats (interaction coefficient of

, SE = 0.06,

). The same interaction of far right and social democratic party is not a significant determinant of attention to the working class. Social Democrats respond to far right growth by reducing the attention they give to non-economic identity groups.

Figure 2. Predicted change in party priorities as a function of far right growth and Social Democratic Party.

Note: Average marginal effects based on regression results shown in Appendix Table A3.

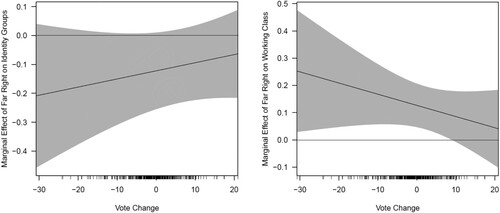

Hypothesis 3 suggests that the link between far right growth and shifts in priorities is conditioned by electoral fortunes, with parties losing votes most likely to shift attention away from identity groups and towards the working class. To test this, we estimate models including an interaction between and Vote Change, measured as vote share at current election minus vote share in previous election. Figure plots the marginal effects, the change in party priorities in response to far right growth and mainstream vote change (see Appendix Table A4 for regression table).Footnote9 The figure shows that party fortunes are not especially consequential for the link between far right growth and identity politics. However, the positive effect of far right party growth on attention to the working class is conditioned by electoral fortunes: faced with a far right challenge, the more votes a party loses, the more it shifts attention to the working class. The effect of far right vote share on attention to the working class is positive and significant except for when the party is doing very well (marginal effects significant when vote change is less than or equal to 9).

Figure 3. Predicted change in party priorities as a function of far right growth and mainstream vote change.

Note: Average marginal effects based on regression results shown in Appendix Table A4.

To ensure that findings are not the result of model misspecification, we also estimate models that include a lagged dependent variable rather than year fixed effects, models with no control variables, and a model which uses working class position (log-ratio scale) as the dependent variable rather than positive attention to the working class. The main findings are robust to these alternative specifications. We also consider whether effects are conditioned by region. We find that the effect of far right success on attention to the working class, in particular, is driven by parties in Western Europe. This is in line with previous work showing that while far right parties in Eastern Europe promote traditional values and reject liberal progressives, unlike their equivalents in the West they do not have a clear social base among the working class (Buštíková Citation2017). Finally, our findings are robust to defining far right growth as the largest far right party, rather than the sum of far right parties (see Appendix for all additional models).

How do mainstream parties respond to far right success? Evidence from Denmark and Sweden

We use qualitative evidence from a matched pair case study to shed light on the question of how mainstream parties shift attention to different identity groups in response to radical right parties. Matched pairs provide a framework for thinking about what would have happened if not for the rise of the far right in one country by considering what happened in a country similar except for a successful far right party (Tarrow Citation2010). We focus on the case of Denmark, where a far right party emerged in the late 1990s, allowing us to clearly distinguish the period before and after far right presence.

We use statistical matching to select a counterfactual case, matching on the potential confounders of immigration, socioeconomic level, and unemployment (Nielsen Citation2016). The matching procedure successfully matches Denmark to Sweden. Both countries are social democratic welfare states with generous social provision, similar party systems, and are often compared (e.g., Green-Pedersen and Odmalm Citation2008). Sweden did not see a significant far right party gain ground in the late 1990s; the Sweden Democrats emerged later. Technical details of the matching procedure are in the Appendix.

We translated and coded party manifestos from mainstream parties in both countries for three elections before and after a far right party gained seats in Denmark (1998). This corresponds to the years 1988–2005 for Denmark and 1988–2006 for Sweden. The case of Sweden offers a second opportunity to examine mainstream responses to the far right following the rise of the Sweden Democrats, which first entered parliament in 2010. Consequently, we also translate and code Swedish manifestos from 2010 to 2018.

We coded individual sentences or semi-sentences from manifestos that relate to five groups: (1) the working class and labor; (2) women; (3) ethnic minority groups; (4) disabled peoples; and (5) LGBTQIA+. The first category captures the economic identity group of the working class, while the latter categories are ascriptive, non-economic groups often referred to jointly in the context of identity politics. We focus on the main center-left (the Social Democratic Party in Denmark and the Swedish Social Democratic Party) and center-right (Venstre in Denmark and the Moderate Party in Sweden) parties. We code manifestos from these 4 parties over 9 election-years, resulting in a dataset of 861 quasi-sentences related to economic and non-economic identity groups. Coding details can be found in the Appendix.

The 1998 Folketinget election saw the electoral breakthrough of Danish People's Party (Dansk Folkeparti, DF). The DF won 7.4% of the vote, finishing fifth behind the mainstream parties Social Democratic Party, Venstre, Conservative People's Party, and Socialist People's Party. After 1998, the DF continued to grow, winning 12% of the vote in 2001 and 13.3% in 2005. Conversely, Sweden did not see far-right entry into the Riksdag until 2010, when the Sweden Democrats won 5.7% of the vote. Previously, between 1988 and 2006, the Swedish party system was characterized by the mainstream Social Democratic Party (SDP), Moderate Party, (Liberal) People's Party, Center Party, Christian Democrats, or Left Party comprising the top four spots in each election. Some scholars describe New Democracy (Ny Demokrati, NyD) as a radical right party (Rydgren Citation2010, but see Gould Citation1996)—and this party did win 6.7% of the vote in Sweden's 1991 election—but they failed to win seats in subsequent elections.

Turning to the Social Democratic parties first, the Swedish Social Democrats offer a range of policies targeting both economic and non-economic identity groups, including a 1988 pledge to abolish class distinctions, solidarity with immigrants and refugees, and promoting good relations between different ethnic groups. They discuss gender inequality and outline related policies including increased flexibility in child care services. These pledges are wrapped in broader expressions of equality: in 1998, “We want to see a society in which all people can develop and influence their life situation, a society where women and men have equal rights regardless of ethnic and cultural background.” This core ideology remains largely unchanged throughout the study period.

After 2010 (when the Sweden Democrats emerged), pledges related to women begin to focus more on “tougher action against sexual offenses” (2018 manifesto) than in earlier years. This mirrors the Sweden Democrats' focus on women as victims, which is often connected to immigration. In 2018, the Sweden Democrats say that, “perceived insecurity among women has increased sharply” and in 2010 they focus on the need to support women, “living under religious and honor-related oppression”. Although the rise of the Sweden Democrats doesn't prompt the SDP to roll back previous commitments on gender equality, it does coincide with a period of stasis where pledges around improving shared family leave and women's employment remain essentially the same between the 1990s and the late 2010s: for example, “our policy is more than anything else about …the situation of families with children” (1998) and “We need to give more families with children more time for fellowship, socializing and recreation” (2018). From 2010, new pledges involving gender equality tend to focus on women as the victims of violence.

In the period between 1988 and 2006, the working class is discussed in the context of offering retraining and support to workers displaced by globalization and of education policy. Following 2010 (when the Sweden Democrats emerged), much of the same messaging remains, though by 2018 increasing economic protectionism is observed, linked explicitly to migration (“Limit labor immigration so that jobs with low educational requirements where there is no labor shortage go to unemployed people in Sweden”). At the same time, later manifestos include increasingly stringent cultural protectionism—including cultural schools (2014) and compulsory language classes for new immigrants (2018)—that track the rise of the Sweden Democrats.

The Danish Social Democratic Party takes a different tack to their Swedish counterparts, with manifestos in 1988 and 1990 making no explicit mention of gender or racial equality. Following a period in government, the 1994 manifesto includes discussion of work-family policies and gender equality in the labour market. The 1998 manifesto (when the Danish People's Party emerge) discusses immigration and assimilation policy at length, underlining that immigrants must accept Danish culture and values and that criminal elements will be returned to their countries of origin. In some cases, these policies are directly compared to those of the Danish People's Party, suggesting that they are a response to them. The manifesto also links immigration to sexual violence and trafficking, for example claiming that “drug crime, robbery, serious violence, and rape must result in expulsion.” There remain mentions of work-family policies, but no explicit pledges on gender equality as seen in the Swedish SDP manifesto at this time. In 2001 and 2005, the party again discusses women's rights in the racialized context of immigration, stating that forced marriages and trafficking must stop. The party thus uses gender as a frame to promote a nationalist “gender equal” identity, in opposition to the non-Western “other” which is presented to pose a threat to Danish culture.

From 2001, the Danish Social Democrats also increase attention to the working class, a group mentioned only once in the manifestos of 1998 and 1994. In 2001, the party discusses activation policy extensively, including continuing education reform, jobs for older unemployed, and flexible jobs for people with reduced working capacity. 2001 is also the year that the Danish Social Democrats began a steady decline in vote share (from 36% in 1998 to 29% in 2001). The increased attention to the working class observed at this time specifically (rather than in 1998 when the far right first entered parliament) supports our quantitative finding that mainstream parties respond to the rise of a far right party by increasing attention to the working class when under electoral threat.

Turning to the center-right parties, in their early manifestos the Swedish Moderate Party focuses squarely on the economy, with only a few mentions of any identity groups. The party promotes quick access to jobs for refugees, as well as briefly notes the need for gender equality in 1994. In 1998 (when the far right emerged in Denmark), the party remains inclusive towards immigrants and refugees, noting that Swedish business can benefit from, “immigrants who build bridges to their home countries.” The 1998 manifesto also continues to promote gender equality, noting Sweden's lack of women in the private sector compared to other countries. In 2002 and 2006, the party strengthens its messages on both inclusivity for immigrants (“Most people who come to Sweden have been forced to flee from their home country or come here because they want to work and build a new future”, 2002) and gender equality.

Overall, while identity makes up far less of the Swedish center-right's agenda than the Social Democrats, there is a clear trend towards greater inclusivity over between 1988 and 2006. After 2010, commitments to equality remain, though often focused on employment opportunities for various identity groups including women, young people, and disabled people. Between 2010 and 2018, the Moderates largely frame equality in terms of access to the labour market, with more generous family leave and healthcare policies discussed in these terms. As with the SDP, while equality-related pledges do not disappear during this time, they are less bold than some of the pledges seen previously, particularly those included in the 2002 and 2006 manifestos.

In addition, we observe a notable increase in messaging around immigration. This includes requirements for arrivals to learn Swedish (similar to the Swedish SDP pledge) and restrictive immigration policies in a broader sense (“An emerging shadow society, where human beings remain without permission, is unacceptable and unsustainable”, 2018). The 2014 and 2018 manifestos explicitly link “culture” or “cultures of honor” to violence against women, including forced marriage and domestic violence, framing these as opposed to Swedish values. For example, in 2018, the manifesto states that “The view of equality within some immigrant groups in Sweden differs from the norms and values that characterize Swedish society ,” this pledge part of a range of pledges that discuss the use of “culture” to hold Sweden together in the face of the “politicization of culture we have seen…abroad”. As with the Swedish SDP, the Moderates appear to respond to the rise of the far-right Sweden Democrats by making protectionist cultural and economic appeals that link to immigration, framing the arrival of immigrants and asylum seekers as potentially inimical to Swedish values of equality for a range of identity groups, not least women.

The Danish Liberal party, Venstre, is similar to the Swedish Moderates in its classically liberal and conservative ideology. In the first two elections—1988 and 1990—Venstre's manifestos are similar to the Swedish Moderates. They are pro-business, anti-public spending, with little mention of any identity groups. In 1994 (the election before the Danish People's Party emerges), Venstre mentions immigration for the first time, linking it to crime: “Criminal asylum seekers who are not entitled to a residence permit under the Refugee Convention must be expelled immediately.” The party repeats ideas about the need to expel foreigners convicted of crimes in 1998. None of these manifestos mention gender or racial equality. In 2001 gender is mentioned, but in the racialized context of immigration. In the section on immigration, the party says that the penalties for trafficking must be increased. This section is immediately followed by one on violence against women (the first year the party raises the issue), which pushes for stronger penalties for rape. In 2005, the manifesto also links immigration to forced marriage and presents it as equivalent to arranged marriage (“It is necessary to protect young girls from unhappy forced marriages and arranged marriages”). This rhetoric around forced marriages was used as a tool to restrict immigration in Denmark with the controversial “24 year” rule on family unification (criticized as a human rights violation by CEDAW).

Table summarizes the key findings of the qualitative analysis. First, we note the main categories of identity groups that parties discuss are related to immigration, the working class, and gender. Appeals for racial equality, mentions of disability, and attention to LGBTQIA+ groups are rare. While mainstream parties in Sweden include various identity groups between 1988 and 2006, the rise of the Danish People's Party looms over the proposals put forward by mainstream parties in Denmark at this time. Appeals to gender equality in Denmark after the rise of the far right DF take on a racialized and nationalist tone, serving to reify claims of minority oppression of women and perceived cultural difference. We see a similar pattern in Sweden after 2010, when the Sweden Democrats emerged: discussion of identity becomes increasingly protectionist in economic and cultural terms, linking the equality of identity groups—especially women's equality and safety—to restrictive immigration policies and the drive to integrate immigrants into the Swedish way of life. The qualitative evidence thus offers additional support for mainstream identity accommodation. Mainstream parties threatened by the far right sideline equality of historically marginalized groups, and appropriate gender as a tool to support nativist, anti-immigration agendas.

Table 2. Summary of change in party attention to identity groups, 1988–2005, Denmark and 1988–2018, Sweden.

Conclusion

Far right parties are “the fastest growing party family in Europe” (Golder Citation2016) and the question of how mainstream parties respond to their challenge is increasingly relevant. In this study, we provide the first cross-national evidence for a backlash over “identity politics”: mainstream parties respond to the rising far right by decreasing attention to non-economic identity groups and increasing attention to the working class. Social Democratic parties are driving the decline in positive attention to non-economic identity groups across the period of our study. The implications are that right party growth does not just have an effect on the political status of immigrants; it has significant consequences for a broader range of identity groups.

While strategic moves to co-opt niche party issues can pay off at the polls, research suggests that the effectiveness of such strategies depends on the electoral context, party identities, and particular issue at stake. For example, governing party accommodation on decentralization decreases ethnoterritorial party vote share at the national level (Meguid Citation2015), but a recent study finds little evidence that mainstream accommodation on immigration weakens far right parties (Krause, Cohen, and Abou-Chadi Citation2022). Others have discussed how, to slow or reverse their declining electoral fortunes, Social Democratic parties should adjust to transformations in their traditional class base and “increase their appeal among the growing groups of socio-cultural professionals and high-skilled labor market outsiders …through investment-oriented economic positions as well as liberal cultural positions” (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Citation2019, 1406). Thus, continuing to reduce attention to non-economic identity groups seems unlikely to ease the troubles of Social Democratic parties.

We note that our study is limited by the countries and time period included in analysis (Europe from 1984 to 2017). This time period also saw mainstream ideological convergence in Europe (e.g., Green and Hobolt Citation2008), which could have made conditions ripe for far right parties to compete on the identity politics critique and for mainstream parties to respond to it. Future research should investigate whether far right parties in other parts of the world may be similarly influencing the priorities of the mainstream—including for example in Brazil, where the rise of far right and misogynist Bolsonaro ushered in an illiberal backlash (Hunter and Power Citation2019).

The question of whether party priorities translate into actual policy outcomes remains. A natural extension of this work is to explore the effects of far right growth on outcomes including legislation and spending on issues related to economic and non-economic identity groups. Another relevant question our results raise is whether mainstream parties also respond to the far left on equality and identity issues, and in particular whether new left or green parties provide a counterpoint that changes the incentives of mainstream parties faced with a growing far right party.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (288.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers of Politics, Groups, and Identities, Matthew Barnfield, Amanda Clayton, Tessa Ditonto, Francesca Gains, Malu Gatto, Mona Morgan-Collins, and seminar participants at the University of Konstanz, Brunel University, Royal Holloway, and the APSA annual meeting 2019 for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For example, Mark Lilla, “The End of Identity Liberalism”, The New York Times; Tomo Lochoki, “Germany's Left Is Committing Suicide by Identity Politics”, Foreign Affairs; Gavin Mortimer, “Macron steps up his war on identity politics”, The Spectator.

2 Wolfgang Thierse,“Wie viel Identität vertrg̈t die Gesellschaft?”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

3 Ned Simons, “Labour Must Stop ‘Obsessing’ About Diversity, Says Stephen Kinnock”, Huffington Post.

4 Elias Thorssen, “Identity Denmark: The debate tearing the Left apart”, Murmur.

5 Bo Rothstein and Sven Steinmo, “‘Us Too!’ – The Rise Of Middle-Class Populism In Sweden And Beyond”, Social Europe.

6 Ava Djamshidi, Veronique Philipponnat, Dorothy Werner, “Exclusif – Feminicides, Egalite, premiere dame, crop top : Macron repond”, Elle.

7 Although we do not account for this added complexity in our analysis, we work from an assumption that party leadership is able to exert considerable control over party platforms. Despite leadership power being conditional on party structure, there is evidence that “leadership domination” is in the ascendancy within parties across multiple contexts (e.g., Schumacher and Giger Citation2017).

8 The data and replication files can be found at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OR11GV.

9 The coefficients, standard errors, and p-values for the dependent variable of identity groups are: Vote Change 0.002, SE = 0.025, p = 0.93, 0.124, SE = 0.075, p = 0.07, Vote Change ×

0.003, SE = 0.003, p = 0.34. For the dependent variable working class: Vote Change 0.012, SE = 0.019, p = 0.55,

0.127, SE = 0.041, p = 0.001, Vote Change ×

0.004, SE = 0.003, p = 0.21.

References

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik. 2016. “Niche Party Success and Mainstream Party Policy Shifts–How Green and Radical Right Parties Differ in Their Impact.” British Journal of Political Science 46 (2): 417–436.

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, Magdalena Breyer, and Theresa Gessler. 2021. “The (re)politicisation of Gender in Western Europe.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 4 (2): 311–314.

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Werner Krause. 2020. “The Causal Effect of Radical Right Success on Mainstream Parties' Policy Positions: A Regression Discontinuity Approach.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 829–847. doi:10.1017/S0007123418000029.

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Markus Wagner. 2019. “The Electoral Appeal of Party Strategies in Postindustrial Societies: When Can the Mainstream Left Succeed?” The Journal of Politics 81 (4): 1405–1419.

- Adams, James, Michael Clark, Lawrence Ezrow, and Garrett Glasgow. 2006. “Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different From Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties' Policy Shifts, 1976–1998.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 513–529.

- Annesley, Claire, Isabelle Engeli, and Francesca Gains. 2015. “The Profile of Gender Equality Issue Attention in Western Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (3): 525–542.

- Bale, Tim. 2003. “Cinderella and Her Ugly Sisters: The Mainstream and Extreme Right in Europe's Bipolarising Party Systems.” West European Politics 26 (3): 67–90.

- Bale, Tim, Christoffer Green-Pedersen, AndréA Krouwel, Kurt Richard Luther, and Nick Sitter. 2010. “If You Can't Beat Them, Join Them? Explaining Social Democratic Responses to the Challenge From the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe.” Political Studies 58 (3): 410–426.

- Bay, Ann-Helén, Henning Finseraas, and Axel West Pedersen. 2013. “Welfare Dualism in Two Scandinavian Welfare States: Public Opinion and Party Politics.” West European Politics 36 (1): 199–220.

- Benedetto, Giacomo, Simon Hix, and Nicola Mastrorocco. 2019. “The Rise and Fall of Social Democracy, 1918–2017.” In Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco. Vol. 31. https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/tcdtcduee/tep1319.htm.

- Bernardez-Rodal, Asuncion, Paula Requeijo Rey, and Yanna G Franco. 2022. “Radical Right Parties and Anti-Feminist Speech on Instagram: Vox and the 2019 Spanish General Election.” Party Politics 28 (2): 272–283. doi:10.1177/1354068820968839.

- Bernstein, Mary. 2005. “Identity Politics.” Annual Review of Sociology 31: 47–74.

- Brambor, Thomas, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder. 2006. “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses.” Political Analysis 14 (1): 63–82.

- Buštíková, Lenka. 2014. “Revenge of the Radical Right.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (12): 1738–1765.

- Buštíková, Lenka. 2017. “The Radical Right in Eastern Europe.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by Jens Rydgren. New York City: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274559.013.28.

- Coffé, Hilde, Bruno Heyndels, and Jan Vermeir. 2007. “Fertile Grounds for Extreme Right-wing Parties: Explaining the Vlaams Blok's Electoral Success.” Electoral Studies 26 (1): 142–155.

- Dancygier, Rafaela. 2020. “Another Progressive's Dilemma: Immigration, the Radical Right and Threats to Gender Equality.” Daedalus 149 (1): 56–71. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01773.

- De Lange, Sarah L. 2016. “A New Winning Formula? The Program Matic Appeal of the Radical Right.” In The Populist Radical Right: A Reader, edited by Cas Mudde, 101–120. London: Routledge..

- Elff, Martin. 2007. “Social Structure and Electoral Behavior in Comparative Perspective: The Decline of Social Cleavages in Western Europe Revisited.” Perspectives on Politics 5 (2): 277–294.

- Enggist, Matthias, and Michael Pinggera. 2022. “Radical Right Parties and Their Welfare State Stances–Not So Blurry After All?” West European Politics 45 (1): 102–128. doi:10.1080/01402382.2021.1902115.

- Erel, Umut. 2018. “Saving and Reproducing the Nation: Struggles Around Right-wing Politics of Social Reproduction, Gender and Race in Austerity Europe.” In Women's Studies International Forum, Vol. 68, 173–182. Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277539517301644.

- Fukuyama, Francis.. 2018. “Against Identity Politics: The New Tribalism and the Crisis of Democracy.” Foreign Affairs (Council on Foreign Relations) 97: 90.

- Gidron, Noam, and Peter A Hall. 2017. “The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right.” The British Journal of Sociology 68: S57–S84.

- Gidron, Noam, and Peter A Hall. 2020. “Populism As a Problem of Social Integration.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (7): 1027–1059. doi:10.1177/0010414019879947.

- Gingrich, Jane, and Silja Häusermann. 2015. “The Decline of the Working-Class Vote, the Reconfiguration of the Welfare Support Coalition and Consequences for the Welfare State.” Journal of European Social Policy 25 (1): 50–75.

- Golder, Matt. 2016. “Far Right Parties in Europe.” Annual Review of Political Science 19: 477–497.

- Gould, Arthur. 1996. “Sweden: The Last Bastion of Social Democracy.” pp. 72–94.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Peter B Mortensen. 2010. “Who Sets the Agenda and Who Responds to it in the Danish Parliament? A New Model of Issue Competition and Agenda-Setting.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (2): 257–281.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Pontus Odmalm. 2008. “Going Different Ways? Right-wing Parties and the Immigrant Issue in Denmark and Sweden.” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (3): 367–381.

- Green, Jane, and Sara B Hobolt. 2008. “Owning the Issue Agenda: Party Strategies and Vote Choices in British Elections.” Electoral Studies 27 (3): 460–476.

- Han, Kyung Joon. 2015. “The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Parties on the Positions of Mainstream Parties Regarding Multiculturalism.” West European Politics 38 (3): 557–576.

- Hunter, Wendy, and Timothy J Power. 2019. “Bolsonaro and Brazil's Illiberal Backlash.” Journal of Democracy 30 (1): 68–82.

- Ignazi, Piero. 1992. “The Silent Counter-Revolution: Hypotheses on the Emergence of Extreme Right-wing Parties in Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 22 (1): 3–34.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2003. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- John, Peter, and Helen Margetts. 2009. “The Latent Support for the Extreme Right in British Politics.” West European Politics 32 (3): 496–513.

- Kitschelt, Herbert, and Anthony J McGann. 1997. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Kováts, Eszter, and Maari Põim. 2015. “Gender as Symbolic Glue.” In Budapest, Foundation for European Progressive Studies. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/budapest/11382.pdf.

- Krause, Werner, Denis Cohen, and Tarik Abou-Chadi. 2022. “Does Accommodation Work? Mainstream Party Strategies and the Success of Radical Right Parties.” Political Science Research and Methods 1–8. doi:10.1017/psrm.2022.8.

- Krause, Werner, and Heiko Giebler. 2020. “Shifting Welfare Policy Positions: The Impact of Radical Right Populist Party Success Beyond Migration Politics.” Representation 56 (3): 331–348. doi:10.1080/00344893.2019.1661871.

- Meguid, Bonnie M. 2005. “Competition Between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success.” American Political Science Review 99 (3): 347–359.

- Meguid, Bonnie M. 2008. “Party Competition Between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe.”

- Meguid, Bonnie M.. 2015. “Multi-Level Elections and Party Fortunes: The Electoral Impact of Decentralization in Western Europe.” Comparative Politics 47 (4): 379–398.

- Meguid, Bonnie M., Hilde Coffe, Ana Catalano Weeks, and Miki Caul Kittilson. 2022. “The New Defenders of Gender Equality: When Do Populist Radical Right Parties Incorporate Women’s Interests?” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest PoliticalScience Assocation, Chicago, IL.

- Meijers, Maurits J. 2017. “Contagious Euroscepticism: The Impact of Eurosceptic Support on Mainstream Party Positions on European Integration.” Party Politics 23 (4): 413–423.

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Vol. 22, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas. 2016. On Extremism and Democracy in Europe. New York: Routledge.

- Nielsen, Richard A. 2016. “Case Selection Via Matching.” Sociological Methods & Research 45 (3): 569–597. doi:10.1177/0049124114547054.

- Noury, Abdul, and Gerard Roland. 2020. “Identity Politics and Populism in Europe.” Annual Review of Political Science 23: 421–439.

- Paternotte, David, and Roman Kuhar. 2018. “Disentangling and Locating the “Global Right”: Anti-gender Campaigns in Europe.” Politics and Governance 6 (3): 6–19.

- Pischke, J. S.. 2005. “Empirical Methods in Applied Economics: Lecture Notes.” Downloaded July 24, 015. http://econ.lse.ac.uk/staff/spischke/ec524/evaluation3.pdf.

- Piscopo, J. M., and D. M. Walsh. 2020. “Backlash and the Future of Feminism.” Signs: Journal of Women and Culture in Society 45 (2): 265–278.

- Röth, Leonce, Alexandre Afonso, and Dennis C Spies. 2018. “The Impact of Populist Radical Right Parties on Socio-economic Policies.” European Political Science Review 10 (3): 325–350.

- Rydgren, Jens. 2010. “Radical Right-wing Populism in Denmark and Sweden: Explaining Party System Change and Stability.” SAIS Review of International Affairs 30 (1): 57–71.

- Sakki, Inari, and Katarina Pettersson. 2016. “Discursive Constructions of Otherness in Populist Radical Right Political Blogs.” European Journal of Social Psychology 46 (2): 156–170.

- Schain, Martin A. 2006. “The Extreme-right and Immigration Policy-making: Measuring Direct and Indirect Effects.” West European Politics 29 (2): 270–289.

- Schumacher, Gijs, and Nathalie Giger. 2017. “Who Leads the Party? On Membership Size, Selectorates and Party Oligarchy.” Political Studies 65 (1_suppl): 162–181.

- Schumacher, Gijs, and Kees Van Kersbergen. 2016. “Do Mainstream Parties Adapt to the Welfare Chauvinism of Populist Parties?” Party Politics 22 (3): 300–312.

- Somer-Topcu, Zeynep. 2009. “Timely Decisions: The Effects of Past National Elections on Party Policy Change.” The Journal of Politics 71 (1): 238–248.

- Spoon, Jae-Jae, and Heike Klüver. 2019. “Party Convergence and Vote Switching: Explaining Mainstream Party Decline Across Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 58 (4): 1021–1042.

- Tarrow, Sidney. 2010. “The Strategy of Paired Comparison: Toward a Theory of Practice.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (2): 230–259.

- Van Spanje, Joost. 2010. “Contagious Parties: Anti-immigration Parties and Their Impact on Other Parties' Immigration Stances in Contemporary Western Europe.” Party Politics 16 (5): 563–586.

- Volkens, Andrea, Werner Krause, Pola Lehmann, Theres Matthieß, Nicolas Merz, Sven Regel, and Annika Werner. 2019. “The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2019b.” https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2019b.

- Williams, R. L. 2000. “A Note on Robust Variance Estimation for Cluster-correlated Data.” Biometrics 56 (2): 645–646.