?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Gender disparities in political attitudes and behavior are widely documented. However, when it comes to immigration policy, there is a lack of consensus in existing research: some studies indicate that women are more opposed to accommodating immigrants than men, while others suggest the contrary or find no significant gender difference. In an effort to shed light on these conflicting findings, this paper focuses on gendered differences in how individuals perceive and cultivate concerns about immigrants. We argue that gender plays a crucial role in how misconceptions about immigrants activate concerns about immigrants. To test our hypotheses, we conducted a pre-registered survey experiment in the Netherlands, in which we randomly varied participants' perceptions of the characteristics of the immigrant population. Our results offer suggestive evidence consistent with previous findings: altering immigrant perceptions did not significantly impact immigration policy preferences of either gender. However, perceiving immigrants as more in need did affect individuals' concerns about immigrants: we found that revised perceptions led men, but not women, to feel less morally obligated to accommodate immigrants.

1. Introduction

Gender disparities in political attitudes and behavior are well-documented. Extensive evidence indicates that women and men systematically hold different attitudes on a range of domestic and foreign policy issues, spanning from redistribution and capital punishment to free trade, the use of force, foreign aid, and climate change.Footnote1 For example, Bush and Clayton (Citation2022) recently documented that women in affluent countries are more inclined than men to address the issue of climate change. These gender-based differences can also manifest in government policies, suggesting that policymakers may also take into account gender-based variations in political attitudes and behavior.Footnote2

An emerging body of research suggests that women's tendency to embrace egalitarian and altruistic values, along with their greater empathetic capacity, plays pivotal roles in understanding these gender variations (Andreoni and Vesterlund Citation2001; Eisenberg and Lennon Citation1983). In the context of immigration policy, where debates often revolve around the plight and human rights of immigrants,Footnote3 we might then anticipate women to be more welcoming toward immigrants, because women are, on average, more altruistic than men.

However, some findings in the immigration literature lead us to expect just the opposite. Women appear more likely than men to view immigrants as a societal burden (Markaki and Longhi Citation2013; Pichler Citation2010). Our secondary analyses of the European Social Survey also confirm these patterns; Figure A.1 in the Appendix shows that even after controlling for basic individual-level covariates, women evaluate immigrants more negatively than men on economic and fiscal grounds. This could be due to women overestimating the size and economic needs of immigrant populations compared to men (Alesina, Miano, and Stantcheva Citation2023). These gender differences in concerns and perceptions lead us to expect women to be more opposed to immigration.Footnote4

Unfortunately, existing evidence remains elusive at best and does not offer conclusive support for either of the diverging arguments. For example, Blinder (Citation2015) and Knoll, Redlawsk, and Sanborn (Citation2011) find that women are more supportive of further immigration.Footnote5 Yet, Sides and Citrin (Citation2007) show no evidence of gender differences, while Mayda (Citation2006) and Facchini and Mayda (Citation2009) report that women are more opposed to further immigration than men. We have also surveyed the literature and collected estimates from 40 regression models of immigration attitudes that include gender as one of the covariates. Table A.1 in the Appendix shows that about 40% of the models report that women are more opposed to immigration, while the rest shows either no gender difference or women being more supportive of immigration.

Whereas it is possible that the variations in previous findings may be attributed to random errors inherent in social science research,Footnote6 it is also plausible that these divergent results stem from differences in how women and men evaluate immigrants.Footnote7 Notably, our analyses, utilizing data from the European Social Survey, reveal significant cross-country variations in gendered assessments of immigration (illustrated in Figure A.2 in the Appendix). This suggests that gender differences in immigration attitudes are context-dependent.

In this paper, we shed light on the mixed findings in the existing literature by introducing a theoretical framework that can account for the influence of various contextual factors, elucidating when men and women hold distinct preferences on immigration. Within this framework, we emphasize the pivotal role of individuals' (mis)perceptions about immigrants. As previously mentioned, ample evidence shows that people often misperceive the size and traits of immigrant populations. Drawing on this literature, we argue that these perceptions significantly impact individuals' concerns about immigrants. Furthermore, we posit that gender acts as a moderator in the link between these perceptions and individuals' attitudes toward immigration policy.Footnote8 Importantly, our emphasis on the variability of perceptions across different contexts allows us to better understand the conditions under which the immigration preferences of men and women diverge.

To illustrate, consider a scenario where perceptions of immigrants deteriorate for some individuals – e.g., negative news about immigrants skews views about immigrants, making them seem more in need. In this case, we anticipate that these revised perceptions sway individuals' stance on immigration policy due to heightened concerns about the impact of immigrants. Importantly, given that women often exhibit higher levels of moral concern, in a situation worsening immigrant perceptions, we expect men, rather than women, to become more opposed to immigration. Conversely, following the same logic, in a scenario where immigrants are portrayed more positively, men may become more supportive of increased immigration than women.

Perceptions of immigrants are endogenous to many observable and unobservable factors; thus, it is intrinsically difficult to study the effect of (mis)perceptions. Unlike previous findings based on observational data, we draw on a growing body of literature about perceptions and misperceptions (e.g., Flynn, Nyhan, and Reifler Citation2017) and evaluate our hypotheses using a pre-registered vignette experiment in the Netherlands. Our experiment randomly assigns new information about immigrants that should shift respondents' perceptions about immigrants and examines whether altered perceptions affect their positions on immigration policy and whether the results differ by respondents' gender.

First, our data provide no consistent support for the argument that the nature of perceptions intrinsically differs by gender, thereby shaping the gendered attitudes toward immigration policy. We also find limited evidence that changes in perceptions about immigrants affect attitudes toward immigration policy, which is consistent with previous studies that people's misperceptions may not be a cause of their attitudes toward immigration policy (e.g., Grigorieff, Roth, and Ubfal Citation2020; Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin Citation2019).

However, in line with our framework, we find evidence indicating that changes in perceptions can influence concerns about immigrants differently between women and men, if not necessarily impacting their attitudes toward policy. When individuals perceive immigrants as being in greater need, both men and women become more concerned about the potential negative economic impacts of immigrants on the national economy. However, these revised perceptions result in gender-specific disparities in moral concerns. Unexpectedly, our analyses reveal that it is men, rather than women, who drive these changes. Men tend to feel less morally obligated to accommodate immigrants when immigrants are perceived to be in greater need, while women do not exhibit the same shift in their moral concerns.

Our study is based on a single case study; thus, the empirical section below offers a discussion about how this scope condition affects our interpretations of the results. Still, despite the limitations, we find important suggestive evidence about the conditions under which men and women vary in terms of their attitudes toward immigration. Notably, our study joins the recent findings of Thöni and Volk (Citation2021) and Bush and Clayton (Citation2022) in showing that men's concerns and attitudes are more responsive to new information.

Based on these findings, we can also speculate about why we observe gendered evaluations of immigrants in certain contexts but not in others. One possibility is that during an economic boom or crisis, when information regarding immigrants is politicized, men may be more susceptible to altering their perceptions of immigration, whereas women might remain relatively less affected by such changes in public discourse. Consequently, (with sustained public discourse), researchers may be more likely to discern women's negative (in relative terms) attitudes toward immigration in economically booming societies.Footnote9 In other words, the gender difference in evaluations and attitudes about immigration (driven by changes in men's evaluations of immigrants) may be highly context-specific and dependent on changes in public discourses about immigrants at the time when surveys are taken. We invite future research to substantiate the important implications. In the conclusion, we summarize several important venues for future research.

2. Theoretical arguments

Prior studies present mixed evidence concerning whether women exhibit a stronger opposition to immigration. The varying results may, in part, be attributed to the inherent random biases that often characterize social science research. However, it is noteworthy that these studies have derived their conclusions from diverse contextual settings, as clearly illustrated in Table A.1. These divergent findings seem to arise from the utilization of distinct surveys, frequently conducted in different countries and time periods.Footnote10

While our evidence (i.e., Figure A.1) suggests that, on average, women tend to perceive immigrants as an economic burden on their society, we also observe significant cross-country variations (i.e., Figure A.2). These variations highlight the potential significance of specific temporal and regional contexts, such as the recent influx of specific immigrant groups, the economic conditions of the country, and, notably, public discourses surrounding these events. Accordingly, this paper advances a theoretical argument that allows for flexibility, recognizing that gendered differences may vary depending on macro-level contexts. In this attempt, we place particular emphasis on the role of perceptions about immigrants, as these perceptions should be shaped by changing contexts.

Two potential mechanisms

The primary emphasis of previous studies has centered on understanding the reasons behind individuals holding negative views toward immigrants, with gendered attitudes being a secondary inquiry. Nevertheless, the literature offers some insights into how gender influences immigration attitudes, which are closely intertwined with individuals' perceptions. Notably, the literature suggests that the influence of people's perceptions about immigrants on their immigration attitudes varies by gender in two distinct ways: (1) gender directly impacts perceptions about immigrants, and (2) gender moderates the connection between perceptions and attitudes toward immigration.

Regarding the first mechanism, the literature suggests that people's perceptions about immigrant populations may shape their attitudes about immigration (Sides and Citrin Citation2007). Despite the fact that these perceptions may not always align with reality (Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin Citation2019), research indicates that women tend to perceive immigrants as poorer and less educated (Alesina, Miano, and Stantcheva Citation2023). These negative perceptions of immigrant populations may contribute to why women often view immigrants as an economic burden rather than as contributors to the economy. Accordingly, it is plausible that gendered attitudes toward immigration are influenced by gendered perceptions of immigrants.

However, the gendered attitudes toward immigration may also stem from gendered concerns of immigrants. In other words, gender may shape immigration attitudes by moderating the link between perceptions and concerns about immigrants. The literature suggests multiple concerns about the impact of immigration, including economic, security, and moral.Footnote11

Among those, this paper focuses on two specific concerns, one utilitarian and one non-utilitarian. As for utilitarian concerns, a wide range of immigration literature finds that natives are concerned about immigrants' potential benefits to society as a whole (Card, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2012; Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2014). Although sociotropic cultural and security concerns may be relevant, as illustrated by Figure A.1 and previous studies, economic concerns seem to differ by gender, and it may well be that perceptions about immigrants affect the economic concerns of men and women differently.

People may also be concerned with non-utilitarian aspects of immigration – following their innate humanitarian motives, they may feel obligated to accommodate immigrants in need.Footnote12 Such moral concerns may be particularly relevant when we consider gender – perceptions about immigrants may affect men's and women's moral concerns differently, as women's empathetic capacity and predisposition toward humanitarianism diverge from men's (Eisenberg and Lennon Citation1983; Rueckert and Naybar Citation2008).Footnote13

Given that the first mechanism has been explored in previous research, this paper hones in on the second mechanism. Below, we delve into how varying concerns and perceptions of immigrants contribute to divergent preferences between men and women regarding immigrants. Additionally, within the realm of the second mechanism, we also highlight the existence of countervailing effects, which can shed light on the inconsistent results observed in previous studies. We then introduce three testable hypotheses centered on the gendered concern mechanism.

Perceptions and economic and moral concerns about immigrants

Multiple concerns related to immigration can influence individual attitudes toward immigration policy. Among them, we focus on two concerns that are particularly relevant: sociotropic economic and moral concerns. First, we assume that people take sociotropic economic impacts of immigrants into account when forming their preferences on immigration policies. Indeed, many studies find that individuals are more concerned about the economic impacts of immigrants on the national economy and budget than on their own labor market competition (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2014).Footnote14

Second, individuals also consider the moral implications of immigration policies. This is evident in public debates over immigration policy, which not only revolve around the benefits and costs of immigrants but also delve into discussions of human rights and the moral consequences of specific policies. For example, the work by Newman et al. (Citation2015) supports the idea that humanitarian concerns for the welfare of other human beings can increase opposition to policies aimed at reducing immigration levels. Kustov (Citation2021) underscores the importance of altruism but argues that their inclination to assist their compatriots – a different form of altruism – moderates their support for immigration.

Crucially, while economic and moral concerns shape people's immigration policy preferences, the relationship between these concerns and policy preferences is intricately tied to their perceptions of immigrants. Drawing on the insights from Alesina, Miano, and Stantcheva (Citation2023) and Grigorieff, Roth, and Ubfal (Citation2020), it becomes evident that people's perceptions of immigrant populations play a pivotal role in shaping their concerns about immigrants.

A recent study by Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin (Citation2019) questions people's misperceptions as a cause of hostility toward immigration policy. Yet, our work is different from their understanding of immigrant perceptions in two key ways: (1) we focus on perceptions about the characteristics of the immigration population, not its size (Grigorieff, Roth, and Ubfal Citation2020); and, (2) we examine the heterogeneous effect of perceptions – in particular, how gender moderates the link between perceptions and relevant concerns, rather than treating perceptions as the single determinant of attitudes toward immigration policy. For example, regarding the first point, if individuals perceive incoming immigrants as low-skilled, they may be more concerned about the economic impact of these immigrants compared to when they perceive them as highly-skilled. Of course, in practice, many people lack the knowledge required to develop well-informed evaluations on these dimensions. Often, inaccurate or misconceived perceptions inform both economic and moral concerns regarding immigrant populations.

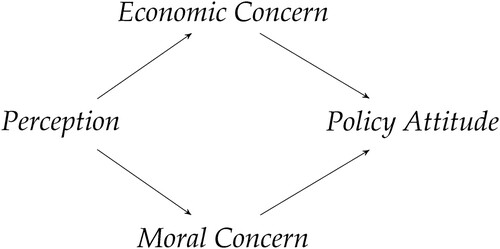

summarizes our basic framework. All else equal, the two concerns operate jointly to produce people's preferences over an immigration policy, and the concerns are influenced by their perceptions about immigrants. We contend that analyzing these multiple concerns jointly and their relationship with perceptions is crucial to understanding the puzzling gender differences in attitudes toward immigrants and their policy preferences. To this end, we now turn to elucidating how gender affects immigration policy preference, from which we derive our testable hypotheses.

Gendered attitudes toward immigration through gendered concerns

While gendered (mis)perceptions about immigrants may explain gendered attitudes toward immigrants (i.e., the first mechanism), this paper introduces an additional avenue through which gender influences immigration policy preferences (i.e., the second mechanism). We highlight the role of gender in shaping concerns and argue that gendered attitudes toward immigration can be explained by gendered concerns about immigrants, even without pre-existing gendered perceptions.Footnote15

How do then men and women care about different aspects of immigration? As for the moral concerns, Newman et al. (Citation2015) show that empathy “activates” concerns for immigrants' well-being and interacts with humanitarian concerns to reduce opposition to restrictive immigration policy. Their results also suggest that individuals who score low on empathy influence other concerns, including personal concerns that immigrants may take natives' jobs. At the same time, previous studies find that women tend to be more empathetic than men (Eisenberg and Lennon Citation1983; Rueckert and Naybar Citation2008).Footnote16 Then, to the extent that women have more empathetic predispositions than men, women are more concerned about the moral aspects of immigration policy than men.

Accordingly, we expect that perceiving immigrants as needier (potentially due to an event such as an influx of immigrants from an economically disadvantaged country) will lead to stronger gendered moral evaluations of immigrants. This is because women, typically more empathetic, might feel a stronger moral duty to help immigrants facing greater need. Conversely, men might feel less of this moral obligation. However, while perceptions of immigrants in greater need should also influence their economic evaluations of immigrants, such perceptions might not significantly affect economic concerns about immigrants differently by gender, suggesting that economic worries remain consistent across genders in response to perceived immigrant needs.

Overall, within our stylized framework (), the gender gap in empathy implies that perceiving immigrants as needier may lead to decreased support for further immigration among men, as their economic concerns are intensified while moral concerns remain relatively unaffected. Conversely, we expect that perceptions of immigrants in greater need are unlikely to substantially alter women's support for further immigration. This is because both their economic and moral concerns are amplified and then counteract each other.

By considering multiple concerns, our argument offers an explanation for the lack of clear gender differences in attitudes toward immigration policy while shedding light on why women may view immigrants as an economic burden in certain situations. For example, if news coverage leads some individuals to view immigrants as needier, we expect that this revised perceptions is likely to reduce men's support for immigration by heightening their economic concerns. For women, the same shift in perception could intensify both economic and moral concerns. Then, assuming both genders experience the same change in perception, men might then exhibit more negative attitudes toward further immigration than women. This implies that, all else equal, when a society faces an immigration-related crisis and worsens the general perceptions about immigrants, it would be men, rather than women, who become more resistant to immigration. By contrast, in periods where immigrants are viewed more positively, men might be more inclined toward further immigration than women, as women's moral obligation to assist might be less pronounced.

This argument provides some coherent explanations for the existing findings. First, Hainmueller and Hiscox (Citation2007) report that women oppose immigrants from rich countries more strongly than do men. According to our argument, while rich immigrants would contribute economically to the host country, there is less moral reason to accept these immigrants. Because of the differences in moral concerns, women are more opposed to accepting immigrants from rich countries, while men tend to view these immigrants more favorably. Second, women tend to be slightly more supportive of accepting immigrants from poor countries than men do (Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2007). Accepting poor immigrants can be economically negative but morally imperative. Because women feel more obligated to help those poor immigrants, our arguments suggest that they are more enthusiastic about accepting poor immigrants than men.

In sum, we have articulated two distinct ways in which gender may influence policy preferences. First, gender may affect perceptions about immigrants, which in turn affects individuals' attitudes toward immigrants. Second, gender influences how perceptions, even if they are not gendered, shape (economic and) moral concerns. These two arguments are not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, they can be at work simultaneously. But given that the first channel has been previously examined, our paper contributes to the literature by focusing on the second, gendered concerns mechanism. The discussion above generates the following three hypotheses that we will evaluate below.Footnote17

| H1: | Perceptions that immigrants are needier lead to more negative sociotropic economic evaluations of immigrants for men and women. | ||||

| H2: | Perceptions that immigrants are needier lead to more positive moral evaluations for women, but less so for men. | ||||

| H3: | Perceptions that immigrants are needier lead to more negative attitudes over immigration policy among men, but less so for women. | ||||

3. Research design and data

We evaluate the hypotheses with a survey conducted in the Netherlands.Footnote18 The survey was fielded in Dutch. Our analysis of the European Social Survey data finds that the Netherlands is one of the cases in which women are more likely to negatively rate the economic impacts of immigrants than men. This suggests that we are more likely to find gendered differences in attitudes toward immigrants in the Netherlands, and we hope future research examines other contexts, especially the least likely cases in which we may not observe the gendered difference in attitudes toward immigrants.

We collect survey data online from a sample of 1000 residents in the Netherlands in February 2021. After excluding non-Dutch and non-White respondents, our sample consists of 868 native Dutch respondents. This is the maximum sample size that our budget allowed for, and the choice of the likely case of the Netherlands partly compensates for the relatively small sample size. The sample is drawn from an online panel of a survey firm, Respondi and is a non-probability sample, but we attempted to approximate the general population using age and gender. Despite our efforts, it turns out that our sample is slightly skewed toward more educated, older, and female citizens compared to the general population. We thus use entropy balancing to address the remaining imbalances in the data (Hainmueller Citation2012).Footnote19

After answering questions about their backgrounds, respondents answer a series of questions about their initial perceptions about the immigrant population in the Netherlands. Following Alesina, Miano, and Stantcheva (Citation2023), we ask, out of every 100 immigrants in the Netherlands, how many they think are (1) currently unemployed, (2) have at least a university degree, and (3) live below the poverty line.Footnote20 We also use this measure to re-examine previous studies' findings that gender differs even in terms of immigration perceptions.

Following the perception questions, we embed an experiment. Testing the hypotheses requires that we experimentally manipulate respondents' perceptions about immigrants. We take advantage of the fact that respondents answered questions about their perceptions of immigrants and tell them whether their perceptions were in line with reality or they underestimated. We randomly assigned respondents to either of the following two conditions: (1) Accurate frame, and (2) Needier frame.Footnote21 Note that respondents were assigned to the experimental conditions regardless of their answers to the perception questions – more accurate or not. All the respondents were debriefed about the goal of the survey and the deception right after the survey.Footnote22

The literature on motivated reasoning suggests that individuals are often resilient to new information that contradicts their priors (Taber and Lodge Citation2006). Thus, the impact of information that contradicts their prior is expected to be weaker or such information may even cultivate backlash attitudes (Nyhan and Reifler Citation2010, but see also Nyhan et al. Citation2019). The recent finding that providing accurate information does not affect attitudes toward immigration is also consistent with this psychological mechanism (Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin Citation2019). Our experiment takes advantage of this human tendency, and with the institutional ethical approval and post-survey debrief to all respondents, the experiment informs respondents that either their prior is more or less accurate (Accurate treatment) or they are wrong but the general direction of their prior is correct (Needier treatment), which should allow us to examine the impact of shifts in misperceptions.

More specifically, respondents in the Accurate group are told:

We previously asked your idea about the characteristics of immigrants in the Netherlands. You answered that out of 100 immigrants, [INSERT THEIR ANSWER] are unemployed, [INSERT THEIR ANSWER] are in poverty, and [INSERT THEIR ANSWER] are not college-educated

According to a report of the non-partisan economic research center, your answers are more or less accurate.

Here, respondents' actual responses to the perception questions are automatically inserted. If respondents are in the Needier frame group, we tell them that:

We previously asked your idea about the characteristics of immigrants in the Netherlands. You answered that out of 100 immigrants, [INSERT THEIR ANSWER] are unemployed, [INSERT THEIR ANSWER] are in poverty, and [INSERT THEIR ANSWER] are not college-educated.

According to a report of the non-partisan economic research center, your answers are lower than the real figures – that is, there are more immigrants who are unemployed, in poverty, and not college-educated than you guessed.

After reading one of the scripts, respondents answer a battery of immigration-related questions. In particular, the following threes serve as our dependent variables:

DV1: “Would you say it is generally bad or good for the Dutch economy that people come to live here from other countries?” on a 5-point scale with (1) “Very bad for economy,” (2) “Bad for economy,” (3) “No impact on economy,” (4) “Good for economy,” (5) “Very good for economy”;

DV2: “Would you agree with the following statement? It is morally the right thing to allow immigrants to come to the Netherlands.” on a 5-point scale with (1) “Strongly disagree,” (2) “Disagree,” (3) “Neither disagree or agree,” (4) “Agree,” (5) “Strongly agree”; and

DV3: “What extent do you think the Dutch government should allow immigrants to come and live here?” on a 4-point scale with (1) “Allow none,” (2) “Allow a few,” (3) “Allow some,” (4) “Allow many”.

The first and third questions are taken from European Social Survey, while the second, moral question is created by the authors following Newman et al. (Citation2015). Note that our dependent variables are about the flow of immigrants, which may lead to the underestimation of moral obligation effects than the stock of immigrants (Margalit and Solodoch Citation2022).

To examine whether our perception interventions influence respondents' moral and economic evaluations, we employ DV1 (for H1) and DV2 (for H2) and compare the responses of men and women across the two treatment groups. According to H1, we expect that believing that immigrants are needier leads respondents to think that immigrants are worse for the Dutch economy, but the effect is similar for both men and women. H2 predicts that believing that immigrants are needier leads respondents to think that accepting immigrants into their country is the more morally right thing to do, but this effect is larger for women than for men.

To examine how our interventions influence policy preferences (H3), we employ DV3 and compare the responses of men and women across the two treatment groups. We expect that among men, respondents in the Needier group give more support for more restrictive immigration policy (compared to those in the Accurate group) because increased severe misperceptions lead them to have more negative views on immigrants' economic contributions to society. But among women, we expect no big difference between responses from the Needier and Accurate groups because women take moral considerations into account.Footnote23

To test H1-H3, we run linear least squares regressions with robust standard errors.Footnote24 All the expectations of H1-H3 can be effectively examined by including interaction terms between the treatment and gender indicator variables. Because our main independent variable, gender, is not an experimental variable, we include pre-registered treatment covariates both to increase the precision of the estimates and remove confounding. Specifically, we include the respondent's self-reported age (years), placement on the left-right ideological spectrum (a seven-point scale), a binary indicator for whether they have a university degree, an index for measuring knowledge deficits (constructed from responses to three questions about Dutch politics, the economy, and the pandemic situation),Footnote25 and four indicators for whether their household income belongs to one of the tertile groups (low, medium, high) or the group that refused to answer the income question.

To increase the quality of our analyses, we take two additional measures. First, some respondents unsurprisingly gave implausible answers to our perception questions. For example, in our data, eight respondents said 100% of the immigrants in the Netherlands are poor. Such responses suggest inattentiveness on the part of respondents. As robustness checks, we replicate our analyses by omitting observations that fall below 10th and above 90th percentiles.Footnote26 Second, following Aronow, Baron, and Pinson (Citation2019), which suggest that excluding respondents who fail the manipulation check can introduce estimation bias, our analyses will not employ a manipulation check question.Footnote27 However, given the growing concerns about non-response from online survey panels such as Lucid (Aronow et al. Citation2020), we include an attention check task in our survey and analyze only those who pass the task. This attention check was included at the outset of the survey to ensure the quality of the responses.

4. Results

We first report an exploration of the perception questions by examining the gender difference in respondents' perceptions of the immigrant population. We pool responses of the treatment and control groups and compare how women's responses to the three pre-treatment perception questions differ from those of men: percentages of unemployed immigrants, those without university degrees, and those living below the poverty line. Using linear regression, we regress those responses on respondents' gender while controlling for a set of pre-registered control variables, including age, left-right ideology, knowledge, income, and education.

shows that after controlling for the covariates, there is no clear pattern indicating that women view immigrants as needier than men. Women report slightly higher percentages of the immigrant population as being unemployed than men, which is consistent with existing findings (e.g., Alesina, Miano, and Stantcheva Citation2023), but the difference is not statistically significant. Other results also show patterns that are not in line with the previous findings. Women guessed substantially lower percentages of immigrants as having no university degrees than men, and the gender difference is statistically significant. Similarly, men and women are not substantially different in their perceptions of immigrants being poor.

Table 1. Gender and perceptions of immigrants.

These results provide little support for the argument that gender influences people's beliefs and attitudes about immigration directly through perceptions about immigrants. If anything, our result on the education question suggests that Dutch men may view immigrants as needier than Dutch women, which runs counter to the findings by Alesina, Miano, and Stantcheva (Citation2023). However, these findings are close to new evidence from a survey in Denmark that Dane men tend to overestimate the immigrants' welfare dependency rate (as well as their crime rate and size) more than women (Jørgensen and Osmundsen Citation2020). Our results suggest that more work is needed to theorize and identify the sources of (mis)perceptions about immigrants. Theoretically – grounded examinations on the origin of (mis)perceptions would be particularly helpful, for example, in identifying the role of gender in shaping attitudes toward immigration.

While our data provide little support for the gender's role in shaping perceptions, some interesting patterns emerge when we examine our hypotheses regarding gendered concerns about immigrants, another channel through which gender may affect immigration policy preferences.

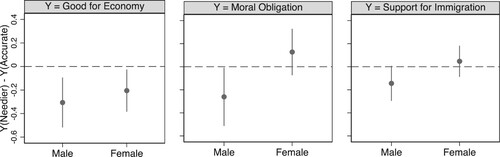

H1 predicts no moderating role of gender in the link between a perception and an economic evaluation of immigration. That is, we expect that perceptions that immigrants are needier lead both women and men to negatively update their evaluations of the economic impacts of immigrants on the national economy. Model (1) of provides evidence consistent with H1. We find that the Needier treatment has a negative impact on the economic evaluations of both women and men respondents. visually illustrates how respondent gender moderates the treatment effect. The left panel shows that the effects are negative, confirming that perceptions that immigrants are needier lead both men and women to think worse of the economic impacts of immigrants on the economy. The results also show that women rate immigrants' economic impacts more negatively than men, which is consistent with our preliminary analyses using the European Social Survey (Figure A.1) and previous studies such as Mayda (Citation2006). Why women rate the immigrants' economic impacts more negatively than men remains unanswered (although our data suggest that it is not due to gendered misperceptions), and we think this is an exciting venue for future research.

Figure 2. Gendered effects of perception, by respondent gender: dots represent mean estimates; lines denote 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2. Gendered effects of the ‘Needier’ treatment on concerns and policy preferences.

H2 predicts that gender moderates the link between perception and the moral evaluation of immigration. Specifically, we expect that perceptions that immigrants are needier increase the feeling of moral obligation, but this effect is larger for women than for men. Model (2) of shows that gender plays a role in linking a perception about immigrants with a sense of moral obligations toward immigrants. However, it appears that men rather than women mainly drive the gender difference in the treatment effect. We find that men and women do not differ in their feeling of moral obligation toward immigrants when told that their initial perceptions of immigrants are more or less accurate. But, the middle panel in illustrates that when told immigrants are poorer, less educated, and more unemployed than their initial guesses, women respondents respond little, while men respondents respond by feeling less morally obligated. Therefore, gender moderates the treatment effect but not in the way predicted by H2, suggesting that perceptions of needier immigrants can weaken – rather than heighten women's – men respondents' feeling of moral obligation. It is possible that because the initial level of moral predispositions is greater for women than for men, they were influenced less by the new morality-inducing information. However, this concern can be mitigated by the finding for the Accurate treatment in which we do not find significant differences between men and women.

Lastly, H3 predicts that perceptions of needier immigrants reduce support for further immigration among men but less among women. Model 3 of shows that the estimated coefficient on our interaction term between perception treatment and gender is positive, though its statistical significance is only marginal. Furthermore, the model shows no significant gender difference in policy preferences. The right panel in visually illustrates these conclusions. The perceptions of needier immigrants reduce men's support for further immigration, while the same perceptions do not affect women's support. Nevertheless, the difference is not statistically significant at the 5% level. Thus, our findings do not provide strong support for H3, and we need to revisit our argument about how perceptions affect natives' attitudes toward immigration differently by gender through moral and economic concerns. In fact, our findings add to the growing body of existing evidence that manipulating perceptions produces little change in attitudes toward immigration policy (Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin Citation2019; Jørgensen and Osmundsen Citation2020; Lawrence and Sides Citation2014) and that those attitudes are rather stable over time (Kage, Rosenbluth, and Tanaka Citation2022; Kustov, Laaker, and Reller Citation2021).

Overall, our empirical analyses do not find consistent support for our unified argument. Still, three important pieces of suggestive evidence emerge. In the concluding section, we discuss the implications of these findings while proposing future research agendas.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we attempted to shed light on conflicting evidence in the literature about gendered attitudes toward immigration. By clarifying and unpacking the mechanisms behind the role of gender in shaping immigration attitudes, our study suggested that, for women, worsened misperceptions about immigrants does not directly translate to a negative attitude toward immigration policy because they generate a countervailing force by activating moral concerns. On the contrary, we expected that men's aggravated misperceptions more directly lead to a more negative policy attitude, suggesting that the overall effect of a perception change on policy attitudes is likely to be larger for men than for women. Consequently, we suggested that the severity of men's misperceptions, as opposed to women's, is likely a critical determinant of gender differences in policy preferences in the context of immigration policy.

As a result of our analyses, we did not find consistent evidence for our integrated argument. However, three pieces of suggestive evidence emerged, which warrant future research. First, although information may not significantly shift people's attitudes toward immigration policy, it can still influence their evaluations of immigrants. Second, in line with our expectation, we found that both men and women equally lower their economic evaluations of immigrants when their perceptions of immigrants become worse while, for some reason, women's initial economic evaluations of immigrants are lower than men's. Third, and importantly, the effect on the (moral) evaluations seems to vary by gender. However, inconsistent with our expectation, we found that women are generally less subject to perception manipulation, while men can be more easily influenced by (mis)information about immigrants. Furthermore, the gendered differences in response to such perception manipulation are most pronounced in their moral evaluations of immigrants.

The findings have several implications. First, although Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin (Citation2019) suggest that the effect of information is limited in terms of shifting people's attitudes toward immigration, this paper highlights that information can, at least, change people's evaluations of immigrants. Second, this paper joins in recent findings emphasizing the role of men's, instead of women's, unique attitudes in explaining gender differences in support for different sets of policies. Thöni and Volk (Citation2021) find that men are more likely to have extreme preferences than women with moderate preferences. Our study also found that men's evaluations of immigrants can fluctuate more than women's, when exposed to (mis)information.

Although scholarship tends to focus on women's distinct preferences and attitudes, such as more altruistic motivations and lower economic literacy, our study suggests that future research would benefit from directing more attention to men's distinct preferences and attitudes when explaining gender differences in policy preferences.

SI.pdf

Download PDF (4.7 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Crabtree, Jan van der Harst, Saliha Metinsoy, Marek Neuman, Yoshikuni Ono, and participants at the workshop in Groningen for their helpful comments and suggestions. Annette Adema, Berrak Gürsaz, and Gina Ikramova provided excellent research assistance. We also thank the University of Groningen for the generous support of this project. The human subject protocol of the research was evaluated and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of University of Groningen, and the research was conducted following the approval. Replication materials will be available at the Harvard Dataverse.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See Alesina and Giuliano (Citation2011), Luttmer and Singhal (Citation2011), Paxton and Knack (Citation2012), Burgoon and Hiscox (Citation2004), Mansfield, Mutz, and Silver (Citation2015), and Brutger and Guisinger (Citation2022).

2 See also Betz, Fortunato, and O'Brien (Citation2023).

3 See Newman et al. (Citation2015) and Fraser and Murakami (Citation2022).

4 We use perceptions and beliefs interchangeably, focusing on individuals' views regarding the immigrant population's characteristics, such as educational attainment. Concerns are defined as positive/negative evaluations of the immigrant population, influenced by these perceptions or beliefs, for example, regarding their economic impact.

5 This is also consistent with the evidence that women are less likely than men to support far-right populist movements and parties that often adopt anti-immigration policies (Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Citation2018; Kimmel Citation2018).

6 It is important to note that in some previous studies, gender has been treated solely as a control variable, which complicates interpretation. Nevertheless, the observed variation across these models is noteworthy and underscores the need for further inquiry.

7 See also Krupnikov, Style, and Yontz (Citation2021) for a possibility that women and men answer survey questions differently.

8 It is important to note that we do not assume that gender differences derive from their biological differences. As the social role theory suggests, gender differences are also due to societal stereotypes about gender (Eagly and Wood Citation2012; Eagly, Wood, and Diekman Citation2000). Still, despite large variations in gender stereotypes, gender inequality remains persistent in all advanced democracies (e.g., none of the advanced democracies have achieved gender parity in the number of politicians). We thus believe that our study has the potential to be generalizable in today's world, although it may become less relevant in a completely gender-equal society.

9 This is consistent with the above-mentioned populism literature highlighting men's support for anti-immigration policies in advanced democracies that have been struggling economically.

10 Table A.1 also shows that various studies employ different dependent variables, which can contribute to the mixed evidence. For example, O'rourke and Sinnott (Citation2006) documents that women tend to be more welcoming of refugees than men, while men are of immigrants than women.

11 These include concerns about cultural dilution (Sides and Citrin Citation2007; Sniderman and Hagendoorn Citation2007), labor market competition concern (Malhotra, Margalit, and Mo Citation2013; Mayda Citation2006; Pardos-Prado and Xena Citation2019), and security concerns (Forrester et al. Citation2019).

12 See also Wright, Levy, and Citrin (Citation2016) for such a categorical judgment. Although contexts differ, they find that strict adherence to rules and laws shapes people's attitudes toward (legal and illegal) immigration policy. Relatedly, the term “morality” may be used differently in different contexts (see also Kustov (Citation2021)), but this paper uses the term strictly as humanitarian concerns in favor of immigrants.

13 See Newman et al. (Citation2015) for individuals' humanitarianism as a countervailing effect on negative attitudes toward immigrants. See also Fraser and Murakami (Citation2022) for similar findings. While we believe that these two concerns – sociotropic economic and moral – are the most relevant for our purpose, future research can incorporate other considerations such as crime and personal economic impacts of immigration. For instance, some may also be concerned with the personal economic impacts of immigrants under specific conditions – e.g., for those that are employed in specific sectors or those with low transferable skills when times are difficult (Dancygier and Donnelly Citation2013; Malhotra, Margalit, and Mo Citation2013; Pardos-Prado and Xena Citation2019), and the concern may differ by gender.

14 See also Avdagic and Savage (Citation2021) and Burgoon and Rooduijn (Citation2021) for more nuanced views.

15 It is important to note that we distinguish between individuals' initial perceptions, which may exhibit gender-related variations according to the first mechanism, and revised perceptions, which are pivotal for our empirical investigation of the second mechanism concerning gendered concerns.

16 However, some argue that women may just be more likely to self-report their empathetic capacity, although there may be no major actual gender differences in the predisposition (Baez et al. Citation2017).

17 While our hypotheses differ in wording and numbering compared to our pre-analysis plan (PAP), they remain substantively the same. We also provide a summary of discrepancies between the PAP and the paper in the Appendix. We recognize that the hypotheses presented here are only a subset of the potential hypotheses that can be derived from our framework. There are other hypotheses ripe for future research, including how perceiving immigrants as less needy influence concerns and attitudes. Additionally, we hope that future research delves more deeply into how mispercpetions lead to gendered attitudes toward immigrants, particularly zeroing in on the psychological processes through which individuals incorporate information based on misperceptions.

18 Our PAP can be found at the Open Science Framework (OSF), URL: osf.io/wnmpa.

19 We also include the results from the unweighted analysis in Section VI.2 in the Appendix, and the results are similar to the weighted analysis.

20 Earlier versions of the paper were available on the National Bureau of Economic Research (https://www.nber.org/papers/w24733).

21 Additionally, we include another group that receives no information (i.e., pure control). While the subsequent analyses are based on the comparison between the Accurate and Needier groups, we use this group to gauge respondents' baseline attitudes. We collect 100 responses for this group. We thus have about 450 respondents for the two main groups, respectively.

22 Table A.2 in the Appendix shows that the key covariates are balanced across the groups.

23 As per the PAP, we checked the assumption that women are more empathetic than men. This was assessed using eight items from the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, specifically focusing on items for empathy and perspective-taking as outlined in Ingoglia, Coco, and Albiero (Citation2016). By analyzing the mean of these eight items as our outcome variable, our finding shows that women indeed demonstrate higher levels of empathy compared to men in our Dutch sample. The average empathy score for women is significantly higher (M = 3.72, SD = 0.02) than for men (M = 3.56, SD = 0.02), , p<0.001.

24 In the PAP, we wrote that ordered logit would be used to test these hypotheses, but for the sake of presentation, we decided to opt for the simpler statistical models. Using ordered logit does not change the core results, and the results with ordered logit are available in Section VI.3 in the Appendix.

25 Specifically, we asked about the number of seats in the Netherlands' House of Representatives, the average monthly income per individual, and the number of COVID-19 cases confirmed in the Netherlands since February 2020 (in thousands). To compute the knowledge deficit index, we first calculated the differences between the correct answers and the responses provided, standardized these differences, converted them into their absolute values, and calculated the mean of these values.

26 Specifically, for our perception analyses, we exclude responses below 10th and 90th percentiles. For the main analyses, we compute a perception index by calculating the mean responses to the three perception questions and then identify the bottom and top 10% based on this index and exclude respondents within these groups. The results are shown in Section VI.1 in the Appendix and remain essentially the same.

27 See also Kane and Barabas (Citation2019).

References

- Alesina, Alberto, and Paola Giuliano. 2011. “Preferences for Redistribution.” In Handbook of Social Economics. Vol. 1, 93–131. Elsevier.

- Alesina, Alberto, Armando Miano, and Stefanie Stantcheva. 2023. “Immigration and Redistribution.” Review of Economic Studies 90 (1): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdac011.

- Andreoni, James, and Lise Vesterlund. 2001. “Which is the Fair Sex? Gender Differences in Altruism.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 116 (1): 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355301556419.

- Aronow, Peter M., Jonathon Baron, and Lauren Pinson. 2019. “A Note on Dropping Experimental Subjects Who Fail a Manipulation Check.” Political Analysis 27 (4): 572–589. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.5.

- Aronow, Peter, Joshua Kalla, Lilla Orr, and John Ternovski. 2020. “Evidence of Rising Rates of Inattentiveness on Lucid in 2020.” https://osf.io/8sbe4.

- Avdagic, Sabina, and Lee Savage. 2021. “Negativity Bias: The Impact of Framing of Immigration on Welfare State Support in Germany, Sweden and the UK.” British Journal of Political Science 51 (2): 624–645. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000395.

- Baez, Sandra, Daniel Flichtentrei, María Prats, Ricardo Mastandueno, Adolfo M. García, Marcelo Cetkovich, and Agustín Ibáíez. 2017. “Men, Women…Who Cares? A Population-Based Study on Sex Differences and Gender Roles in Empathy and Moral Cognition.” PloS One 12 (6): e0179336. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179336.

- Betz, Timm, David Fortunato, and Diana Z. O'Brien. 2023. “Do Women Make More Protectionist Trade Policy?” American Political Science Review 117 (4): 1522–1530. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001307.

- Blinder, Scott. 2015. “Imagined Immigration: The Impact of Different Meanings of ‘immigrants’ in Public Opinion and Policy Debates in Britain.” Political Studies 63 (1): 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12053.

- Brutger, Ryan, and Alexandra Guisinger. 2022. “Labor Market Volatility, Gender, and Trade Preferences.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 9 (2): 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2021.9.

- Burgoon, Brian, and Michael J. Hiscox. 2004. “The Mysterious Case of Female Protectionism: Gender Bias in the Attitudes and Politics of International Trade.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, September 2–5.

- Burgoon, Brian, and Matthijs Rooduijn. 2021. “‘Immigrationization’ of Welfare Politics? Anti-Immigration and Welfare Attitudes in Context.” West European Politics 44 (2): 177–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1702297.

- Bush, Sarah Sunn, and Amanda Clayton. 2022. “Facing Change: Gender and Climate Change Attitudes Worldwide.” American Political Science Review 117 (2): 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000752.

- Card, David, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston. 2012. “Immigration, Wages, and Compositional Amenities.” Journal of the European Economic Association 10 (1): 78–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01051.x.

- Dancygier, Rafaela M., and Michael J. Donnelly. 2013. “Sectoral Economies, Economic Contexts, and Attitudes Toward Immigration.” Journal of Politics 75 (1): 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000849.

- Eagly, Alice H., and Wendy Wood. 2012. “Social Role Theory.” In Handbook of Theories in Social Psychology. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Eagly, Alice H., Wendy Wood, and Amanda B. Diekman. 2000. “Social Role Theory of Sex Differences and Similarities: A Current Appraisal.” In The Developmental Social Psychology of Gender. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Eisenberg, Nancy, and Randy Lennon. 1983. “Sex Differences in Empathy and Related Capacities.” Psychological Bulletin 94 (1): 100–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.94.1.100.

- Facchini, Giovanni, and Anna Maria Mayda. 2009. “Does the Welfare State Affect Individual Attitudes Toward Immigrants? Evidence Across Countries.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 91 (2): 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.91.2.295.

- Flynn, D. J., Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler. 2017. “The Nature and Origins of Misperceptions: Understanding False and Unsupported Beliefs About Politics.” Political Psychology 38 (S1): 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.2017.38.issue-S1.

- Forrester, Andrew C., Benjamin Powell, Alex Nowrasteh, and Michelangelo Landgrave. 2019. “Do Immigrants Import Terrorism?” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 166:529–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2019.07.019.

- Fraser, Nicholas A. R., and Go Murakami. 2022. “The Role of Humanitarianism in Shaping Public Attitudes Toward Refugees.” Political Psychology 43 (2): 255–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.v43.2.

- Grigorieff, Alexis, Christopher Roth, and Diego Ubfal. 2020. “Does Information Change Attitudes Toward Immigrants?” Demography 57 (3): 1117–1143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00882-8.

- Hainmueller, Jens. 2012. “Entropy Balancing for Causal Effects: A Multivariate Reweighting Method to Produce Balanced Samples in Observational Studies.” Political Analysis 20 (1): 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr025.

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Michael J. Hiscox. 2007. “Educated Preferences: Explaining Attitudes Toward Immigration in Europe.” International Organization 61 (2): 399–442. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818307070142.

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Daniel J. Hopkins. 2014. “Public Attitudes Toward Immigration.” Annual Review of Political Science 17 (1): 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/polisci.2014.17.issue-1.

- Harteveld, Eelco, and Elisabeth Ivarsflaten. 2018. “Why Women Avoid the Radical Right: Internalized Norms and Party Reputations.” British Journal of Political Science 48 (2): 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000745.

- Hopkins, Daniel J., John Sides, and Jack Citrin. 2019. “The Muted Consequences of Correct Information About Immigration.” The Journal of Politics 81 (1): 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1086/699914.

- Ingoglia, Sonia, Alida Lo Coco, and Paolo Albiero. 2016. “Development of a Brief Form of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (B–IRI).” Journal of Personality Assessment 98 (5): 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2016.1149858.

- Jørgensen, Frederik Juhl, and Mathias Osmundsen. 2020. “Correcting Citizens' Misperceptions About Non-Western Immigrants: Corrective Information, Interpretations, and Policy Opinions.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 7 (1): 64–73.

- Kage, Rieko, Frances M. Rosenbluth, and Seiki Tanaka. 2022. “Varieties of Public Attitudes Toward Immigration: Evidence From Survey Experiments in Japan.” Political Research Quarterly 75 (1): 216–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912921993552.

- Kane, John V., and Jason Barabas. 2019. “No Harm in Checking: Using Factual Manipulation Checks to Assess Attentiveness in Experiments.” American Journal of Political Science 63 (1): 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.2019.63.issue-1.

- Kimmel, Michael. 2018. Healing From Hate: How Young Men Get Into and Out of Violent Extremism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Knoll, Benjamin R., David P. Redlawsk, and Howard Sanborn. 2011. “Framing Labels and Immigration Policy Attitudes in the Iowa Caucuses: ‘Trying to out-Tancredo Tancredo’.” Political Behavior 33 (3): 433–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9141-x.

- Krupnikov, Yanna, Hillary Style, and Michael Yontz. 2021. “Does Measurement Affect the Gender Gap in Political Partisanship?” Public Opinion Quarterly 85 (2): 678–693. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab031.

- Kustov, Alexander. 2021. “Borders of Compassion: Immigration Preferences and Parochial Altruism.” Comparative Political Studies 54 (3): 445–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020938087.

- Kustov, Alexander, Dillon Laaker, and Cassidy Reller. 2021. “The Stability of Immigration Attitudes: Evidence and Implications.” Journal of Politics 83 (4): 1478–1494. https://doi.org/10.1086/715061.

- Lawrence, Eric D., and John Sides. 2014. “The Consequences of Political Innumeracy.” Research & Politics 1 (2): 2053168014545414. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168014545414.

- Luttmer, Erzo F. P., and Monica Singhal. 2011. “Culture, Context, and the Taste for Redistribution.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3 (1): 157–179.

- Malhotra, Neil, Yotam Margalit, and Cecilia Hyunjung Mo. 2013. “Economic Explanations for Opposition to Immigration: Distinguishing Between Prevalence and Conditional Impact.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (2): 391–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.2013.57.issue-2.

- Mansfield, Edward D., Diana C. Mutz, and Laura R. Silver. 2015. “Men, Women, Trade, and Free Markets.” International Studies Quarterly59 (2): 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.2015.59.issue-2.

- Margalit, Yotam, and Omer Solodoch. 2022. “Against the Flow: Differentiating Between Public Opposition to the Immigration Stock and Flow.” British Journal of Political Science 52 (3): 1055–1075. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000940.

- Markaki, Yvonni, and Simonetta Longhi. 2013. “What Determines Attitudes to Immigration in European Countries? An Analysis at the Regional Level.” Migration Studies 1 (3): 311–337. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnt015.

- Mayda, Anna Maria. 2006. “Who is Against Immigration? A Cross-Country Investigation of Individual Attitudes Toward Immigrants.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 88 (3): 510–530. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.3.510.

- Newman, Benjamin J., Todd K. Hartman, Patrick L. Lown, and Stanley Feldman. 2015. “Easing the Heavy Hand: Humanitarian Concern, Empathy, and Opinion on Immigration.” British Journal of Political Science 45 (3): 583–607. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000410.

- Nyhan, Brendan, Ethan Porter, Jason Reifler, and Thomas J. Wood. 2019. “Taking Fact-Checks Literally But Not Seriously? The Effects of Journalistic Fact-Checking on Factual Beliefs and Candidate Favorability.” Political Behavior 42 (3): 939–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09528-x.

- Nyhan, Brendan, and Jason Reifler. 2010. “When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions.” Political Behavior 32 (2): 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2.

- O'rourke, Kevin H., and Richard Sinnott. 2006. “The Determinants of Individual Attitudes Towards Immigration.” European Journal of Political Economy 22 (4): 838–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2005.10.005.

- Pardos-Prado, Sergi, and Carla Xena. 2019. “Skill Specificity and Attitudes Toward Immigration.” American Journal of Political Science 63 (2): 286–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.2019.63.issue-2.

- Paxton, Pamela, and Stephen Knack. 2012. “Individual and Country-Level Factors Affecting Support for Foreign Aid.” International Political Science Review33 (2): 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512111406095.

- Pichler, Florian. 2010. “Foundations of Anti-Immigrant Sentiment: The Variable Nature of Perceived Group Threat Across Changing European Societies, 2002-2006.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 51 (6): 445–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715210379456.

- Rueckert, Linda, and Nicolette Naybar. 2008. “Gender Differences in Empathy: The Role of the Right Hemisphere.” Brain and Cognition 67 (2): 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2008.01.002.

- Sides, John, and Jack Citrin. 2007. “European Opinion About Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests and Information.” British Journal of Political Science 37 (3): 477–504. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123407000257.

- Sniderman, Paul M., and Louk Hagendoorn. 2007. When Ways of Life Collide: Multiculturalism & Its Discontents in the Netherlands. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Taber, Charles S., and Milton Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.2006.50.issue-3.

- Thöni, Christian, and Stefan Volk. 2021. “Converging Evidence for Greater Male Variability in Time, Risk, and Social Preferences.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (23): e2026112118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2026112118.

- Wright, Matthew, Morris Levy, and Jack Citrin. 2016. “Public Attitudes Toward Immigration Policy Across the Legal/Illegal Divide: The Role of Categorical and Attribute-Based Decision-Making.” Political Behavior 38 (1): 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9311-y.