ABSTRACT

In the wake of the July 2016 putsch and the subsequent purge of followers of the outlawed Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen in every sphere of Turkish life under the ruling AKP government’s state of emergency, the Gülen movement (GM) is in disarray and crisis. A fruitful way to bring some analytical order to this issue is through the frame of diaspora, which we contend provides some useful analytical purchase on understanding the movement historically and in transition. The GM as it stood prior to 2016 is, we contend, best conceived as a transnational parapolitical network—a ‘diaspora by design’—dedicated principally to the service, not of humanity, but of power. Based on interviews with over 70 key members of the movement conducted between 2012 and 2018, we show how, from the late 1990s Gülen and his supporters crafted a complex transnational structure that has combined extensive financial operations with a distinctive organizational morphology. We map out the contours of this structure and show how it emerged over time via instrumentalization of Gülen’s parapolitical ideology and the steady accretion of politically directed, corporate projects outside Turkey. Finally, drawing again on the notion of diaspora, we offer a framework for thinking about how the movement may evolve in future as it transitions to a fragmented community in transnational in political exile.

Introduction

In the wake of the July 2016 putsch and the subsequent purge of followers of the outlawed Turkish cleric, Fethullah Gülen in every sphere of Turkish life under the ruling AKP government’s state of emergency, the Gülen movement (GM) is in disarray and crisis. A fruitful way to bring some analytical order to this issue is through the frame of diaspora, which we contend provides some useful analytical purchase on understanding the movement historically and in transition. The overarching theme of the article is that the GM outside turkey is in transition from a ‘diaspora by design’ to a dispersed and fractured community in transnational political exile.

More concretely, the principal claim we advance in this article is that the GM as it existed prior to 2016 is best conceived as a transnational parapolitical networkFootnote1 dedicated not to the service of humanity—as the GM’s favoured term for itself, Hizmet, implies—but to the service of power; namely, that of Fethullah Gülen. We suggest that, over the course of three decades, Gülen and his most senior acolytes ‘mobilized transnational space’Footnote2 to craft a unique, parapolitical organizational structure that combined a distinctive institutional morphology and dense network of financial operations, the elements of which have worked synergistically to further Gülen’s pursuit of power. We map out the contours of this structure as it existed prior to 2016 and show how it emerged over time via instrumentalization of Gülen’s parapolitical ideology and the steady accretion of politically directed educational, media and publishing, and other corporate projects outside Turkey.

While this structure has been dramatically reshaped—and substantially weakened—after July 2016 much of it remains in place abroad, especially in Western countries such as Australia, Sweden, the UK and the United States. The pre-coup structure of the movement is thus worth laying out in detail, not least because coming to grips with where the movement is headed needs a clear understanding of where it has come from.

Our research is based on extensive fieldwork and close empirical research, especially in the sensitive post-2013 period in which the AKP–GM split burst into public view. It builds on recent media reporting as well as the fieldwork of the authors, conducted over the past 5 years in Western Europe, the Balkans, Turkey and Southeast Asia, in the form of semi-structured interviews with over 70 members of the movement. Because of the parapolitical nature of the organization, its structure can only be accurately sketched from data drawn directly from those within it. Strict confidentiality was offered to the interviewees, most of whom agreed to participate only on condition of anonymity. In lieu of audio recordings, the interviews were transcribed with detailed written notes. For this reason, the validity of the collected data is increased, albeit at some unavoidable cost in transparency.

Additionally, we have sought to enhance validity by adopting multi-sited data triangulation as a validation strategy. ‘Triangulation of data’ as Flick observes, ‘combines data drawn from different sources and at different times, in different places or from different people’.Footnote3 Interviews were conducted with 79 individuals between February 2012 and June 2017 across 11 countries (Turkey, the UK, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Serbia, Cambodia, Thailand, and Sweden). The spread of interviews conducted covers the broadest possible range of actors within the movement and includes 11 students within the dershane [education centre] network.Footnote4 presents the summary breakdown of these interviews. In addition to triangulation across individual sources, we triangulated primary data with a variety of secondary sources, including existing studies of the movement, news reports and other materials.

Table 1. Breakdown of interviewees.

The article proceeds as follows. It begins with a brief review of the existing literature on diasporas, focusing particularly on Martin Sökefeld’s understanding of diaspora as an ‘imagined transnational community’ and his suggestion to draw on the insights of social movement theory in theorizing diasporic formation.Footnote5 In the second part, we show how Gülen and his senior acolytes mobilized in transnational space to construct their parapolitical ‘diaspora by design’. We detail the GM’s deft navigation of the opportunity structures that opened up for Turkish Muslim business after the end of the Cold War and after the September 11 terrorist attacks, by instrumentalizing Gülen’s parapolitical ideology to craft a complex transnational expatriate structure through the steady accretion of politically directed corporate projects around the world. We then present out analysis of the overarching organizational structure of the network as it existed up to July 2016, based on its three key elements: (1) a ‘control centre’ based on Gülen and the Grand Council of Elders (still largely intact); (2), the civic face of the movement (mostly intact outside Turkey, dismantled at home), and its ‘dark networks’ of influence in political circles and in the state structure (now largely extricated in waves of purges since July 2016). Finally, we offer a framework for thinking about how the movement may evolve in future as it transitions to a fragmented transnational community in political exile.

Diaspora formation: lessons from social movement theory

In his 1992 book Tribes: How Race, Religion and Identity Determine Success in the New Global Economy, Joel Kotkin coined the term ‘diaspora by design’ to describe the transnational network of trading companies and businesses constructed by Japanese expatriate professionals in the interwar period.Footnote6 These managers leveraged the tremendous human and financial capital built up in Japan in the wake of its rapid modernization and industrialization to venture overseas in search of new markets and opportunities. By drawing on Kotkin’s moniker here to describe the GM, we seek to highlight the opportunity structure presented by contemporary neoliberal globalization for the movement and its underlying strength as an economically successful diaspora, which was—at its peak—worth, according to some accounts, as much as US$25 billion globally.Footnote7 The parallels are instructive for the three features most commonly associated with the movement—a cohesive collective identity, an advantageous occupational profile, and motivation to acquire education and knowledge—are the same three that, as Kotkin notes, predict whether a mobilized economic diaspora is likely to succeed.Footnote8

The concept of diaspora, while not essentially contested in the strong sense, is certainly highly contested both intellectually and politically.Footnote9 Rather than revisit the debate here, we follow Brubaker’s emphasis on the ‘three core elements that remain widely understood to be constitutive of diaspora’.Footnote10 These are: ‘dispersion in space’, ‘orientation to a homeland’ and ‘boundary maintenance’.Footnote11 Moreover, we take up the suggestion of Brubaker and others that diasporas are best not thought of as not merely as concrete entities but also as communities of practice whose collective identity is not natural or given but constructed via mobilization—in Sökefeld’s terms, imagined transnational communities.Footnote12

In reflecting on the core ideas of mobilization of collective identity in this way Sökefeld points to insights from social movement theory in helping us make sense of diasporic formation. In particular, he draws our attention to the three key theoretical elements that have grounded research in the field: opportunity structures, mobilizing structures, and ideational frames. Opportunity structures refer to the set of opportunities (and constraints) confronting collective action that shape actors’ ‘choice set’ in taking action to achieve objectives. Mobilizing structures are the common institutions or practices that the transnational community deploys to conscript resources, exchange information and coordinate collective action. Finally, frames are ‘specific ideas that fashion a shared understanding […] by rendering events and conditions meaningful [… through] a common framework of interpretation and representation’.Footnote13

Mobilization in transnational space: opportunity, ideology, practices

Opportunity

Over the decades, the GM expanded—seemingly exponentially—the number and influence of its affiliated schools, companies and trade associations, media and publishing holdings, and cultural centres dedicated to interfaith dialogue across the world, seizing the opportunities offered by neoliberal globalization and the yearning in the West for a model of ‘moderate’ Islam compatible with both capitalist market economics and liberal democracy. According to one count at its peak, there were around 300 affiliated schools in Turkey and over 1,000 of them in as many as 160 countries across the globe, including 120 charter schools in the United States. By 2008, The Economist would proclaim that the GM was ‘vying to be recognized as the world’s leading Muslim network’.Footnote14

The movement’s success abroad has rested, in the first instance, on its capacity to deftly navigate—from the 1980s through to the early 2000s—three distinct political opportunity structures. The first of these, as many scholars have noted, was the policy of neoliberal restructuring in Turkey under the leadership of Turgut Özal (prime minister, 1983–1989, president, 1989–1993). This allowed Gülenists to build much-needed human and financial capital. Leveraging this resource, the movement then used the opportunity presented by the end of the cold war and Özal’s foreign policy orientation towards the Turkic-speaking, former Soviet Central Asian republics to mobilize for transnational network expansion. Finally, the movement was able to take advantage of the desire for ‘good’ Islam in the West after the September 11 terrorist attacks. With its public emphasis on ‘liberal’ Islam, interfaith dialogue, and the importance of rational knowledge and modern science, the movement was able to effectively place itself on the ‘right’ side of what Mahmood Mamdani has termed the ‘culture talk’ in the West that bifurcated the Islamic World into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslims.Footnote15

Ideology

The transnational collective mobilization of the GM from the 1990s onwards cannot be understood outside the set of complex ideational frames—grounded in a distinct synthesis of Ottoman-Turkish nationalist and Islamic thought—deployed by Gülen to propel the movement abroad. Gülen’s ideology is central to our understanding of it as a parapolitical organization. To review, according to Scott a parapolitical organization is a ‘system or practice of politics in which accountability is consciously diminished’.Footnote16 According to Scott, parapolitics are a manifestation of deep and complicated politics in which all political activities, arrangements and aims—deliberate or otherwise—are hidden, rather than acknowledged. Moreover, each element of a parapolitical organization serves political aims, either directly or indirectly.Footnote17

The movement’s ideology and worldview is inextricably linked to the life experience of Fethullah Gülen himself. To begin, the apparent extraordinary personal charisma of Fethullah Gülen himself bears noting. As Joshua Hendrick has observed, ‘the Hocaefendi’s ability to wield social power amazes’.Footnote18 He is revered by his followers, whom outsiders frequently (and often disparagingly) refer to as Fettullahcı (disciples of Fethullah), although members themselves do not use this term. Instead, his ‘followers refer to him as hocaefendi (roughly “master teacher”), in contrast both to the ulema, experts in religious studies, and to şeyhs, masters of sufi brotherhoods’.Footnote19 At the same time, it is clear that he is perceived as a teacher and orator of extraordinary gifts, with tremendous passion, gravitas and wisdom. As HendrickFootnote20 notes, from the beginning, his capacity to link intellectually ‘an applied understanding of [religious] teachings with the challenges of late-industrial Turkey’ has been a prime source of recruitment and mobilization.

Gülen’s ideological outlook can usefully be thought of as a product of three distinct influences, the first of which is Islam, and in particular the biography of the Prophet Mohammed and his followers.Footnote21 As Hendrick notes, ‘Gülen equates the significance and necessity of the coming generation with the first generation of Muslims that emerged following Muhammed’s ministry in seventh-century Arabia (al-salaf).’Footnote22 Gülen’s reading of the life of the Prophet and other Islamic teachings in the modernist tradition have been central to his articulation of a ‘theology of action’. Aksyion [action] is a leitmotif in all his teachings, which as Yavuz notes, emphasizes ‘control over material conditions as a way of enhancing spiritual needs and ends’. Yavuz observes, further, that Fethullah Gülen has always cast ‘himself as a contemporary man of praxis, as well as of spiritual contemplation’.Footnote23 His followers, who follow his example closely, draw on this in their own lives.

The second formative influence on Gülen’s ideology is the socio-cultural milieu of his formative years in his native province of Erzurum in eastern Turkey, and the particular brand of chauvinistic Turkish statist—nationalism that characterizes the region. As Yavuz notes:

The dominant culture in the region is state-centric, and the people of the region, known by their regional identity as Dadaş, traditionally have given the state priority over religion […] Gülen’s conception of Islam is conditioned by this nationalism and statism.Footnote24

The third, and arguably most crucial, influence on Gülenist ideology is undoubtedly the legacy of Gülen’s links with Said Nursi (1876–1960), the author of a three-volume exegesis on the Qur’an known as The Epistles of Light (Risale-i Nur Külliyat, RNK), and the founder of the most prominent text-based Islamic movement in Turkey, commonly referred to in Turkey as the Nurcu. Nursi’s legacy is critical in at least two respects, both of which relate to the mobilizing institutions and practices of the movement, to which we now turn.

Practices

We can identify five distinct institutions and practices within the movement that have been central to its transnational mobilization: institutionalized sohbetler [reading groups], the practices of hizmet [service] and hicret [religiously inspired migration], collectively developed eserler [projects], and himmet [voluntary donations]. Let us take each in turn.

Networking, fund-raising and planning: the institution of sohbetler

At the heart of the GM are the regular sohbetler or reading groups, where cemaat gather to discuss Gülen’s teachings. However, beyond this the sohbetler act as central hubs for ‘fund-raising, organizational planning, and social networking […] linking individuals in Istanbul and London, Baku and Bangkok, New York and New Delhi, Buenos Aires and Timbuktu in a shared ritual of reading, socializing, money transfer, and [intra-community] communication exchange’.Footnote27

The sohbetler are outgrowths of the highly ritualized, underground group meeting culture of the followers of Said Nursi, as mentioned a forerunner of Gülen’s movement. Gülen adopted Nursi’s commitment to mobilization via ‘secretive solidarity network’,Footnote28 eschewing ‘active’ politics and avoiding the gaze of an overbearing Turkish state. Gülen and his movement, like Nursi before him, were—at least prior to 2002—sceptical of publicly visible political activism and ‘criticized [other] Nurcu intellectuals […] for their deep engagement in politics’.Footnote29 Such a posture contrasts dramatically with the ‘actively political’ ethos of the public branch of Turkish Islam—the Milli Görüs—from which the ruling AKP was born. While for Nursi this ideological commitment meant being entirely ‘non-political’, for Gülen it has translated into parapolitical activity. Hendrick claims that the GM should be seen as ‘passively political’, but our claim is that the notion of ‘parapolitical’ is far more accurate. For us, the idea of ‘parapolitical’ ideology and strategy closely reflect Hendrick’s notion of ‘strategic ambiguity’ and Angey’s notion of ‘ambiguous identification’, while providing slightly more analytical and empirical coverage.Footnote30

Becoming expatriates: the role of hizmet and hicret

Hizmet or service is a core practice within the core loyal following of Fethullah Gülen [the cemaat] and represents an individual’s responsibility to pious aksyion in the service of God, for the sake of mankind. Cemaat followers have typically pursued hizmet through hicret [religiously inspired migration].Footnote31 In the context of the movement, this means contributing to GM-inspired projects—principally schools—overseas. In this regard, there are parallels with the transnational aspects of Mormonism, namely, the commitment of the members of the LDS Church to perform missionary work abroad in the service of the glory of God.Footnote32

Project-based, transnational corporate expansion through eserler

Third, the practice of bringing to fruition Gülen-inspired initiatives or projects [eserler], predominantly schools, but also other commercial media, publishing and manufacturing enterprises. Indeed, eserler have been central to the expansion of the movement historically in Turkey in the 1980s and transnationally from the mid-1990s. The model of continuous expansion via eserler was laid down in Turkey in 1976, with the establishment of the Akyazılı Foundation for Middle and Higher Education, the ‘original GM institution’.Footnote33 Each project eventually begot a new one, prompting a virtuous circle as the profits from each were driven back into the network via profits leading to even greater contributions and investments in yet new eserler, and on and on. From the mid-1990s, the movement replicated this model abroad, expanding its footprint globally, first (tentatively) into Western Europe (through dialogue centres in the Netherlands and Germany) and then into Central Asia (via the establishment of schools).Footnote34 The GM later moved into Russia, Australia, Southeast Asia and Africa.Footnote35

As will be discussed in further detail below, the organization until the 2016 coup had kept a clear control over this network via management committees or boards of trustees [mütevelli heyeti] who, with guidance and advance from Gülen himself, would decide about how the movement would pursue its next project:

The people that we call trustees are the ones who run the regions that they are in charge. They have a certain commitment to hizmet and do their prayers in full. They try to provide whatever is needed in their areas in material and spiritual.Footnote36

The establishment of Bank Asya (BA), an Islamic (i.e. interest-free) financial institution that began with start-up capital from 16 businessmen loyal to Gülen in 1996, exemplifies this process of project-based expansion. BA—now taken over by the Turkish state—was one of the most significant eser the GM had ever initiated, underpinning its dramatic growth in the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century. Indeed, the story of its founding could be read as a template by which all new eserler are born in the GM: Gülen simply announced ‘it would be good if this could be done’, and the wheels began to turn. As one of Hendrick’s contacts observed:

Hocaefendi said it would be beneficial for them [GM-affiliated businessmen], for their future enterprises, and he asked them to pray. So people came together and it started [Bank Asya] in this way […] But Hocaefendi does not have an account [at the bank].Footnote37

Financing by way of himmet

The ethos of himmet [voluntary contributions] based on the Islamic tenet of charitable giving form the well-spring of the GM’s pre-2016 financial operations. The financing of these projects has come largely from these voluntary contributions, made by the hundreds of thousands of ‘ordinary’ followers, systematically instrumentalized over the decades to construct the sprawling corporate network that underpins the movement. As a result, a highly organized, albeit radically decentralized, fund-raising system was developed at the centre of Gülen’s powerful network.

Indeed, without this financial dimension, the movement would have been nothing. As one of our interlocuters observed: ‘It doesn’t work without donations. It is with donations that the wheels turn.’ Another noted, ‘The bitter truth is that not much can be done without material resources. This is why the movement includes a voluntary-based economic mind-set.’Footnote38 Cemal Uşak, former president of the now-shuttered Gazeteciler ve Yazarlar Vakfı (Journalist and Writer’s Foundation, JWF) and one of the movement’s most prominent public figures, confirmed the role that contributions have made to the GM’s growth and development: ‘The main sources of this movement are Qur’an, our prophet and then Mr. Gülen but that is not to say money is not important. How else could have we opened up so many schools?’Footnote39

Members contribute what they can out of their own pocket, and the degree to which they are close to Gülen is dependent on the level of their contribution. Less prominent contributors (e.g. small traders or professional salary men) do not necessarily expect anything direct or concrete in return, and simply trust that their funds will contribute to the network’s expansion and growth, for example by providing start-up capital for a new venture. Yet, members are aware that their participation in the GM via economic contributions may also yield new business opportunities. As one interviewee noted,

The main gain for me is spiritual. At the same time, of course, I have made friends from business circles through Hizmet’s network. We have seen opportunities opened up across the world outside Turkey. This has broadened our horizons both in terms of network and business. This was all because of Hizmet.Footnote40

If you are a businessman, you shall either sell something, or you offer a service. Out of [those] who will need your service, they will come to you first. Why? Because they know about your character! You are already two steps ahead of your competition with these people.Footnote42

Organizational morphology

How precisely were these mobilizing institutions and practices instrumentalized in Gülen’s ‘diaspora by design’ prior to 2016? We contend that Fethullah Gülen and his close circle crafted, from the late 1990s, a very distinctive organizational morphology to do so. Although this structure has been dramatically reshaped—and substantially weakened—after July 2016 much of it remains and it is thus worth analysing, not least because—as we noted in at the top of the article—where the movement has come from offers some clues as to how it will evolve in the future.

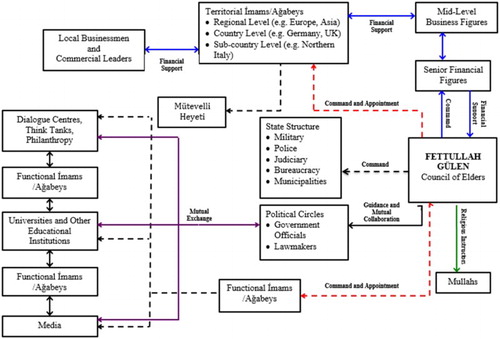

presents an organizational chart detailing the structure of the GM prior to the commencement of the crackdown on the movement in the second half of 2016. It depicts the three core elements of the movement as it existed at that time—its ‘control centre’ in Pennsylvania (still intact), the civic face of the movement (mostly intact outside Turkey, dismantled at home), and its ‘dark networks’ of influence in political circles and in the state structure (now largely extricated in waves of purges since July 2016).

Gülen and the Grand Council of Elders: the ‘control centre’ of the network

The control centre is the ‘heart’ and the ‘brains’ of the movement and is completely hidden from public view. Since Gülen’s self-imposed exile to the United States in 1999, the ‘control centre’ has been physically based in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania. The ‘inner sanctum’, which comprises Gülen and the Grand Council of Elders, senior businessmen, and the ‘Mullahs’ or religious/theological advisors, exemplifies the parapolitical precept that public accountability in political activity must be consciously diminished. The undisputed decision-making body within the network is the Council of Elders, chaired by Gülen himself. It typically has 10–15 members at any one time and consists of loyalists of long-standing hand-picked by Gülen, many of whom have been with him since the beginning. Unwavering loyalty and demonstrated management and political acumen are considered the key attributes for appointment to this body.

The leaders (CEOs, board members) of the most successful business groups within the network (e.g. Koza İpek Grubu in Ankara, Dumankaya Grubu in Istanbul, Boydak Holdings in Kayseri, and Kavuklar Holdings, in Izmir)Footnote43 were—prior to 2016—a second element of the movement’s ‘inner sanctum’. As mentioned earlier, the collective action of these senior business figures was institutionalized in the 2000s in the form of business organizations, particularly TUSKON. This group might have comprised as many as 50 senior business figures, all of whom maintained a ‘direct line’ to Gülen. They would consult him on major business decisions, provide individual and collective financial support, and would be available for advice, consultation, and ‘favours’. The sheer size of the businesses made these men—and the coordinating capacity of institutions like TUSKON—very powerful mobilizers within the GM.

The final component of the inner sanctum has been the ‘mullahs’, the select group of followers who act as the primary spiritual intermediaries between Gülen and the disparate members of the global community of men and women who follow him.Footnote44 As one interviewee noted ‘the mullahs are the spiritual representatives of Gülen in every unit and thus their religion based precepts and advice are very valuable for us’.Footnote45

Recruitment and public relations: the ‘civic face’ of the movement

The associational element of the movement—its schools and study centres, think tanks and dialogue centres, and its media outlets—is the part of the GM that has been most ‘visible’ to the public. Each institution or organization within the ‘civic face’ is itself the product of some prior, politically directed eser, which—as mentioned above—produced the organic expansion in the movement over time.

Every unit within the ‘civic face’ of the movement has served one of two core functions: recruitment or public relations. First, recruitment. The private educational network has been crucial here. It was established as part of a long-term strategy by Gülen to both bring spiritual renewal to Turkish society from the ‘bottom up’ and lay the ground for the development of a new, powerful social and economic elite in Turkey, capable of gradually displacing the entrenched secular Kemalist elites from their bureaucratic, judicial and corporate industrial and media redoubts. As one interviewee mentioned, ‘The students of today will become the governors, judges, administrators as well as business people of the future. That is to say, today’s businessmen and other influential figures used to be simple students too.’Footnote46 As Findley, notes by ‘shaping the students’ personhood (kişilik) an identity (kimlik), the goal is to craft a golden generation (altın nesil) of Turks who can be producers, not consumers, of modernity’.Footnote47 At the same time, the preparatory schools served as the principal means to recruit students enrolled in the traditional bases of secular socialization—the elite lycees and the military schools—by providing them with afterschool and weekend Islamic instruction and socialization into the movement, undetected. In this way, the movement could evade the military’s robust filtering system, to enter and build networks within the armed forces in the 1990s and 2000s, culminating most obviously in the abortive July 2016 putsch.

The second function of the ‘civic face’ of the movement is public relations. As mentioned, Gülen has long been suspected of conspiracy in Turkey. As Hendrick notes: ‘Fears about “Fetullahcılar” (Fethullahists) infiltrating Turkey’s civilian and military bureaucracies in an effort to patiently “Islamicize” the secular republic are common.’Footnote48 For this reason, the movement has ‘become quite adept at anticipating [attacks] and thus developed a sophisticated system of refutation and denial’.Footnote49 The JWF—now closed down after the coup attempt—and the Turkish daily newspaper Zaman—taken over by the state in March 2016—were critical here. Even though these institutions both had a very clear and distinct institutional existence (separate legal status and governance structures) they were as close to and dependent on Gülen as any other part of the network. The primary purpose of these outlets has been to publicize the positive elements of the movement and to engage in protective ‘damage control’ whenever the movement is imperilled. This often involves a proactive ‘counter-defamation’ strategy of which many of the GM’s ‘insider’ scholars have been an integral part. This creates a sort of back and forth between the movement and its critics, as Tittensor observes:

[A] discourse has developed between the movements, its detractors and observers that can be described as a media merry-go-round; continual volleys of accusations are met by counter-accusations, but the questions about the Gülen movement are never really resolved.Footnote50

The ‘dark network’ within the Turkish state structure

Parapolitics is always associated with covert action and subterfuge, typically relying, as Scott reminds us, on ‘political exploitation of […] parastructures, such as intelligence agencies’ or other coercive arms of the state.Footnote52 What we are calling Gülen’s erstwhile ‘dark network’ of influence within the Turkish state structure () reflected this dimension of the parapolitical within the movement. Gülen has long been suspected of seeking to infiltrate the state structure, and this ambition has been one of the key reasons the organization has come under attack in Turkey and abroad.Footnote53 Graham E. Fuller, former vice-chairman of the US National Intelligence Council, for example, claimed almost a decade ago that Gülenists have become deeply entrenched in the police and intelligence services.Footnote54 Indeed, as Yavuz noted in his 2003 book, Islamic Political Identity in Turkey, ‘Gülen has not hidden his cooperation with the State Intelligence Service.’Footnote55

A now infamous sermon delivered via cassette tape in the 1980s has long been seen as the ‘smoking gun’ pointing to Gülen’s ambitions to surreptitiously capture the Turkish state by infiltrating it:

You must move in the arteries of the system, without anyone noticing your existence, until you reach all the power centers […] You must wait until such time as you have gotten all the state power, until you have brought to your side all the power of the constitutional institutions in Turkey […] Until that time, any step taken would be too early—like breaking an egg without waiting the full forty days for it to hatch. It would be like killing the chick inside. The work to be done is [in] confronting the world. Now, I have expressed my feelings and thoughts to you all—in confidence […] trusting your loyalty and sensitivity to secrecy. I know that when you leave here—[just] as you discard your empty juice boxes, you must discard the thoughts and feelings expressed here.Footnote56

[From 2002] then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan appointed followers of Fethullah Gülen to key government positions. This administrative support from the Gülen movement enabled the AKP to govern the country and closely monitor the military with the help of the police force.Footnote57

Our interviews confirm that an extensive network of Gülen-linked officials within the Turkish state structure was well-advanced by the time of the December 2013 corruption probe crisis, especially in critical positions such the head of the Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors and the commissioner of police. As a member very close to Gülen told us:

Of course, we have many friends in the state. We have friends who are tied to us at many levels. Most of them are our old students but only seniors and Hocaefendi know precisely where these people are placed. There are absolutely people within the state who have visited Hocaefendi and follow his guidance and advice.Footnote59

Additionally, Gülen sought indirect influence in Turkey’s wider political circles, mostly comprising government officials and elected law makers. Before the corruption probe brought the AKP–Gülen ‘marriage of convenience’ to a very public end in 2013–2014, AKP government officials would visit Gülen in Pennsylvania almost as a matter of course. This constant traffic between Gülen and leading AKP figures—such as Bülent Arınç, Ahmet Davutoğlu, and Cemil Çiçek—was part and parcel of network governance in Turkey. These invitations and subsequent meetings were frequently very public (often garnering front-page headlines in Turkish newspapers) and encouraged more junior ministers and members of parliament to reach out to Gülen. With these visits, Gülen would take the opportunity to influence political circles, for example, by leaning on a minister to appoint a Gülenist to a senior administrative position. For instance, as one interviewee noted:

We never mention political issues in our inner circle. But, of course there are our people (brothers) who are also involved with these issues. It is also known that Hocaefendi is visited by many Turkish and foreign politicians every year. He naturally gives them advice and guidance and I personally know that they follow his advice.Footnote60

Command and control

As far as the movement’s ‘dark network’ in the state structure is concerned, as mentioned the lines between Gülen and his appointees was covert, direct and closely held. However, as mentioned relations in the broader network were—and still are—diffuse and ambiguous. A question, therefore, arises as to how Gülen has managed to exert control over such a sprawling network. We identify two types of command structures that have been set up organically over time to facilitate such control and that in many parts of the world survive intact. The first is what we label the ‘functional command structure’. At its heart are senior Gülen loyalists who have developed a lifetime’s technical expertise in a particular aspect of the network, be it business, education, media, or philanthropy. We refer to these men and—in a novel development in some cases now womenFootnote61—as ‘functional’ imams or ağabeys [literally ‘older brother’, but in this context ‘chief’]. Originally drawn from the first generation who studied with Gülen in the early 1970s, but more recently from a newer generation raised in the movement in the 1980s and 1990s,Footnote62 Gülen’s ‘charismatic aristocracy’ as Hendrick refers to them,Footnote63 have been the key nodes in the network; each retains a direct link to Gülen.

Perhaps the best example of a functional ağabey of the new generation is Ekrem Dumanlı, a former editor-in-chief of Zaman (2001–2015). Dumanlı would travel regularly to Pennsylvania to seek Gülen’s counsel and return to Turkey and recalibrate the editorial policy of the paper per Gülen’s wishes. As one interviewee noted:

After the visits of Ekrem ağabey to Hocaefendi, he had more clear ideas about the general policy of the newspaper and he started to move according the general advice of Gülen; in my personal view this is very normal since we are a community and our leader is Hocaefendi.Footnote64

Territorial command structure

The ‘control centre’ has also employed a second form—what we refer to as the ‘territorial command structure’—to exert its power. The transnational territorial command structure built on the control model developed in Turkey prior to the movement’s expansion in the mid-1990s, but also refined it in the process. To wit, Gülen’s followers evolved a complex command structure based on the twin pillars of mütevelli heyeti [management committees] and what we refer to as ‘territorial’ imams or ağabeys.

It bears repeating that, while the network overall has lacked hierarchical structure—a point also made by Hendrick in his discussion of ‘strategic ambiguity’ as an organizational strategy—within individual elements of the network, hierarchical command is very much a practical concern. In this sense, hierarchy matters, although in a very subtle and subterranean fashion. This is particularly true of the GM’s territorial command structure. At the apex are regional ağabeys who cover an entire international region (e.g. Continental Europe, North America, Southeast Asia). These regional imams are understood by all within that territory as the direct representative of Gülen and are acknowledged by all as acting on his behalf. As one interviewee noted, ‘So, can there be a unit without some kind of administration? Of course not! This is why every unit needs to have a big brother who is in charge and this is what provides order.’Footnote67

As mentioned, all members of the cemaat have been expected to follow a vocation that takes the journey of the Prophet Mohammed and his followers as inspiration. Gülen’s philosophy is that, much like the Prophet, leaders remain spiritually and managerially vital if they are constantly moving and tested by new experiences and new challenges. Accordingly, regional ağabeys traditionally remained in one place for a maximum of four years and were in constant dialogue with the Council of Elders about the development of human capital in their region before they would move on to a new (and presumably more challenging) assignment.

Regional imams work closely with the local mütevelli heyeti, which has been responsible for the administration of existing eserler and the launching of new ones. It is worth briefly to detail an example of how the territorial structure and mütevelli heyeti would be mobilized to initiate a new eser outside Turkey. Gülen and the Council of Elders would determine that a new school or dialogue should be opened in, say, Myanmar. The regional ağabey (in this case for Southeast Asia, headquartered in Bangkok, Thailand) and local mütevelli heyeti would receive ‘guidance’ from Gülen and would assess their capacity to initiate the project. If insufficient start-up capital could not be found in Bangkok, an appropriately sized local sub-country level mütevelli heyeti inside Turkey (that of, say, Gaziantep) would be mobilized to raise the funds. This then would become a joint-venture between the Bangkok and Gaziantep ağabeys and mütevelli. In this way, local efforts in Myanmar would be fully supported until that country’s ağabey and mütevelli could stand on its own two feet financially and organizationally. This, then, is how the GM has expanded both in Turkey and globally since the 1980s.

Conclusion: the future of the GM in transnational political exile

At the very beginning of 2018, we had an opportunity to talk to a former senior member of the defunct JWF, who sought political asylum in Stockholm after June 2016. In our conversation, we asked him to reflect on the fate of the organizational structure of the GM in the wake of recent events. His answer was quite an indicator of the transformation of the movement in exile:

This is a very good question indeed. If I say to you that, yes, everything has been proceeding as it had been [before the crackdown], that would be a lie. There are now many issues regarding economic resources and connections among our friends. First, we have lost our economic power and therefore some of the areas cannot supply minimum necessities. Our friends have dispersed to different countries and most of them in Turkey are in prison. So, it is impossible to keep the organisational system and discipline the same as it was. But, the organisational system has not collapsed totally; I believe that Hizmet will adapt itself to these new conditions and become more localized in every single country.Footnote68

As this is an exilic diaspora in the making, it makes sense to frame this putative social formation in the terms we laid out at the top of the article: as a transnational imagined community whose evolution will be structured by opportunity structures, ideational frames, and mobilizing institutions and practices. The first, if obvious, point to make is that what we have witnessed since at least 2015 is the transportation of a domestic political conflict into transnational space. The Turkish state has sought to replicate the crackdown at home abroad. However, as Elise Féron and others have observed, the conflict in countries of settlement does not simply reproduce the home conflict but is impacted by variation in transnational space of the nature of the host countries and patterns of migration.Footnote69

This focus on conflict autonomization points to the first element in the framework: the role of political opportunity structures. As scholars of political exile and conflict-generated diasporas have noted, the patterns in which conflicts are transported from the home country into transnational space are highly dependent on conditions in countries of settlement. As Shain observes, ‘The destination of political exile is always a great factor in determining not only the character of the exiles’ struggle from abroad but also their political and cultural outlook.’Footnote70

We contend that in those countries with more open politics and with less dependence on Turkey as far as foreign policy is concerned, the GM will have more opportunity to flourish. We see this playing out today in the core nodes in which the network is stable: the United States, Australia, the UK, and Sweden. In a sense, we expect to see the GM adopting a stance in exile not too dissimilar to that of the Cuban diaspora in the United States, namely ‘a mixing of exile politics (i.e. opposition from abroad) with “transnational” economic and political lobbying of “normalized” diasporas’.Footnote71 That it is doing so primarily from Western countries, and—notably—from Sweden, where Turkish diasporic political activism has long been welcomed, is testament to the variation in political opportunities mentioned above.Footnote72

This points to the second element in the frame, ideational and mobilizing structures. As far as these are concerned, Gulen movement public outreach and media enterprises are ‘playing to their strengths’ in using the network’s long-established PR skills and cultural diplomacy efforts to both lobby host publics and governments and launch a coordinated campaign of opposition to President Erdoğan and the ruling AKP government in Turkey. Interestingly, at the macro level there has been a subtle but noticeable shift in framing. This is arguably best exemplified by the ‘research and publishing’ strategy of the GM’s Stockholm Center for Freedom, based in Sweden. The structure of the Center’s website reflects a discursive ‘turn’ from the GM’s long-standing focus on interfaith dialogue and peace to new frames of ‘hate speech’, ‘press freedom’, and reporting on ‘torture’ and ‘persecution’. Here, again we see the adaptability of the movement as it coopts the language of Western anti-authoritarianism and political and civil rights, arguably to leverage the current tensions in relations between Turkey and the West.

At the same time, at the micro level there is evidence that ‘ordinary’ cemaat members are turning to a renewed emphasis on their religious faith in mobilizing to overcome the crisis, Dumovich observes. As she notes,

The ubiquitous narrative among my interlocutors is that ‘Everything we are going through now happened to our Prophet, it happened to many prophets in the history of mankind. There is no problem, we know we are in the righteous path, and that is all that matters’.Footnote73

Finally, we turn to mobilizing institutions and practices. The old model of transnational corporate growth through eserler has been undermined by the crackdown in Turkey and the sapping of financial resources in Turkey. The Turkish state has shuttered all Gulen schools and taken over its media and business enterprises, all in all absorbing more than US$13 billion worth of GM assets in Turkey, approximately half of the global value of the network.Footnote74 In its wake, Gülenists are having to do more with less. As, as Clifford asserts, for the GM this means ‘decentred, lateral spaces’ are likely to be as important ‘as those ‘formed around a teleology of origin/return’.Footnote75

As schools have been at the heart of the movement, efforts have been made to close them across the globe.Footnote76 This has been resisted in many places, however this does not mean that existing arrangements have remained in place. In Cambodia, for example, while the two educational outfits of the GM—Zaman University and the Zaman International School—were not transferred to the Turkish state they were taken over by local actors close to the Cambodian government, presumably with either a dilution or ending of GM control.Footnote77

Moreover, the movement is establishing new projects, particularly in the online advocacy space. Here, again, the movement is being less than transparent and rather evasive. But—true to form—the establishment of online sites such as turkeypurge.com and the Stockholm Center for Freedom—which deliberately coopt the language of Western human rights discourse and anti-authoritarianism of organizations like Amnesty International—reflect the movement’s long-standing habit of seeking ‘legitimation by association’.Footnote78

Since 2013, when the AKP–Gülen split burst into the open, the political ambitions of Fethullah Gülen have been thrown into sharp relief. This article has attempted to shed much-needed light on the inner workings of Gülen’s sprawling network through an analysis of the GM’s pre-2016 financial operations and organizational structure. In so doing, we have advanced the core claim that the GM was neither a high-minded voluntarist civic movement nor a ‘terrorist network’ or a ‘parallel structure’ within the Turkish state. Rather, we have argued that it is best conceived as a transnational parapolitical organization dedicated to the pursuit of power. In pursuing this claim through a comprehensive, rigorous, theoretically informed but empirically grounded analysis, we hope to have avoided many of the ideological traps that existing research has often fallen into.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors .

Notes on contributors

Simon P. Watmough is currently a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests sit at the intersection of international relations and comparative politics and include varieties of post-authoritarian states, political change in developing societies, the role of the military in regime change, and the foreign policy of post-authoritarian states in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. His work has been published in Urban Studies and Turkish Review. In addition to his academic publications, he is also a regular contributor to The Conversation and several other media outlets.

Ahmet Erdi Öztürk is currently a PhD candidate and a research assistant at the Faculty of Law Social Science and History at the University of Strasbourg and he is EUREL’s (Sociological and Legal Data on Religions in Europe and Beyond) Turkey correspondent. He is also a Swedish Institute fellow at Institute for Research on Migration, Ethnicity and Society (REMESO) for the year of 2018 and a former fellow at Centre for Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz. He is the co-editor of Authoritarian Politics in Turkey: Elections, Resistance and the AKP with Bahar Baser (IB Tauris, 2017) He has also published articles in Journal of Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, Journal of Critical Studies on Terrorism, Oxford Bibliographies, Journal of Research and Politics on Turkey, Muslim Year Book (Brill) and Journal of Balkan and Near East Studies, and Religion and Politics.

ORCID

Simon P. Watmough http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5137-9119

Notes

1 The concept of ‘parapolitics’ we use here serves as a useful way to frame the movement’s well-known aversion to transparency and penchant for evasion. According to Peter Dale Scott, a seminal figure in the field of parapolitical studies, a parapolitical organization is one that engages in a ‘practice of politics’: (1) ‘in which accountability is consciously diminished’; (2) in which political action is ‘covert’ (i.e. based on ‘indirection, collusion, and deceit’ and that; (3) typically involves ‘political exploitation of […] parastructures, such as intelligence agencies’ or other coercive arms of the state’. See Peter Dale Scott, The War Conspiracy: JFK, 9/11, and the Deep Politics of War (Ipswich, MA: Mary Ferrell Foundation Press, 2008), p. 238. Hendrick’s notion of ‘strategic ambiguity’ and Angey’s related concept of ‘ambiguous identification’ have emerged as analogous frames for understanding the discursive and instrumental practices that the GM adopts ‘to persuade outsiders that stated objectives correspond with observable outcomes’, as well as ‘plausible deniability’ and to maintain ‘a certain level of non-transparency’ Joshua Hendrick, Gülen: The Ambiguous Politics of Market Islam in Turkey and the World (New York: New York University Press, 2013), p. 58. See also Gabrielle Angey, ‘The Gülen Movement and the Transfer of a Political conflict from Turkey to Senegal’, Politics, Religion & Ideology, 19:1 (2018), pp. 53–68, doi:10.1080/21567689.2018.1453256.

2 Martin Sökefeld, ‘Mobilizing in Transnational Space: A Social Movement Approach to the Formation of Diaspora’, Global Networks, 6:3 (2006), pp. 265–284.

3 Uwe Flick, ‘Triangulation in Qualitative Research’ in Uwe Flick, Ernst von Kardorff, and Ines Steinke (eds) A Companion to Qualitative Research (London; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2004), p. 178.

4 It is worth emphasizing this point in particular. David Tittensor has rightly noted that the ‘missing link’ in empirical work on the movement has been the incorporation of the perspective of dershane students. David Tittensor, ‘The Gülen Movement and the Case of a Secret Agenda: Putting the Debate in Perspective’, Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations, 23:2 (2012), pp. 170–171.

5 Sökefeld, op. cit.

6 Joel Kotkin, Tribes: How Race, Religion and Identity Determine Success in the New Global Economy (New York: Random House, 1992).

7 Burhan Gurdogan, ‘Religious Movements in Turkey’, OpenDemocracy, 20 December 2010, https://www.opendemocracy.net/burhan-gurdogan/religious-movements-in-turkey.

8 Kotkin, op. cit.

9 See William Safran, ‘Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return’, Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies, 1:1 (1991), pp. 83–99; Rogers Brubaker, ‘The “diaspora” Diaspora’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28:1 (2005), pp. 1–19, doi:10.1080/0141987042000289997. Robin Cohen, Global Diasporas: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008).

10 Brubaker, op. cit.

11 This last concept refers to ‘the processes whereby group solidarity is mobilized and retained, even accepting that there are counter processes of boundary erosion’. It is this that ‘enables one to speak of a diaspora as a distinct “community”, held together by a distinctive, active solidarity, as well as by relatively dense social relationships that cut across state boundaries and link members of the diaspora into a single “transnational community”’. Brubaker, op. cit., p. 6.

12 Sökefeld, op. cit.

13 Ibid., pp. 269–270.

14 ‘How Far They Have Travelled’, The Economist, 6 March 2008, https://www.economist.com/node/10808408.

15 Mahmood Mamdani, ‘Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: A Political Perspective on Culture and Terrorism’, American Anthropologist, 104:3 (2002), pp. 766–775. This point is also made by Caroline Tee, ‘The Gülen Movement in London and the Politics of Public Engagement: Producing “Good Islam” Before and After July 15th’, Politics, Religion & Ideology, 19:1 (2018), pp. 109–122, doi:10.1080/21567689.2018.1453269, and David Tittensor, ‘The Gülen Movement and Surviving in Exile: The Case of Australia’, Politics, Religion & Ideology 19:1 (2018), pp. 123–138, doi:10.1080/21567689.2018.1453272.

16 Scott, op. cit., p. 238.

17 Ibid.

18 Hendrick, op cit., p. 4.

19 Carter Vaughn Findley, Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History, 1789–2007 (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2010), p. 386.

20 Hendrick, op cit., p. 3.

21 Yavuz, Islamic Political Identity in Turkey, pp. 211, 173.

22 Hendrick, op cit., p. 107.

23 Hakan Yavuz, Toward an Islamic Enlightenment: The Gülen Movement (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 33.

24 Yavuz, Islamic Political Identity in Turkey, p. 181.

25 Ibid.

26 Hendrick, op. cit., p. 241.

27 Hendrick, op. cit., p. 116.

28 Ibid., p. 155.

29 Ibid., p. 183.

30 Hendrick, op. cit., p. 32 ff. Angey, op. cit.

31 Hicret is Turkish word for the Arabic term hirja—the migration of the Prophet Mohammed and his followers to Medina in 622AD—an event marking the beginning of the Islamic calendar. The followers of Gulen see themselves as the heirs of the companions of the Prophet who emigrated with Muhammad to Medina, at great sacrifice to themselves.

32 On this, see Melvyn Hammarberg, The Mormon Quest for Glory: The Religious World of the Latter-Day Saints (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 197–224.

33 Hendrick, op. cit., 107.

34 İştar B. Gözaydın, ‘The Fethullah Gülen Movement and Politics in Turkey: A Chance for Democratization or a Trojan Horse?’, Democratization, 16:6 (2009), pp. 1214–1236.

35 Hendrick, op. cit., p. 20.

36 Field interview, January 2014.

37 Cited in ibid., p. 168.

38 Field interview, November 2014.

39 Field interview, May 2012.

40 Field interview, May 2012.

41 Hendrick, op. cit., pp. 158–164.

42 Cited in ibid., p. 160.

43 The coup attempt and its aftershocks have affected the situations of these business groups’ owners. Among them, Akın İpek, the head of Koza İpek Grubu has decamped from Turkey and the heads of Boydak Holdings and Kavuklar Holdings were arrested on charges of supporting the GM’s illegal activities. Furthermore, among these groups Boydak Holdings assets were transferred to the Deposit Insurance Fund (TMSF) on the grounds of alleged ties to the GM.

For details see: https://www.dailysabah.com/economy/2016/09/05/gulen-linked-boydak-holding-transferred-to-turkeys-regulator-body-tmsf.

44 At the risk of stating the obvious, the Gülen network is made up of individuals who pursue a deeply religious way of life. It is not surprising, therefore, that they seek spiritual guidance—‘practical theology’—in a variety of different aspects of their daily lives. This is, after all, the core of the movement. While Gülen is the principal teacher and guide and the primary conduit of all the teachings within the neo-Nurcu tradition, ordinary members of the movement cannot contact him directly for advice or counsel. Access to his teachings and guidance is provided instead through the appointment of religious advisors (‘mullahs’) through key nodes in the network. They act therefore as ‘spiritual intermediaries’ between Gülen and his sprawling network of followers. Gülen retains a direct link to the ‘mullahs’. They are handpicked men who are typically graduates of İmam-Hatip schools in Turkey, and who have pursued prior degrees from theology faculties. They spend between 12 and 48 months with Gülen, training, discussing, and mastering the works of Said Nursi before they are deployed into key nodes of the network.

45 Field interview, December 2013.

46 Field interview, May 2015.

47 Findley, Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity.

48 Hendrick, op. cit., p. 6.

49 Ibid., p. 7.

50 Tittensor, ‘Secret Agenda’, p. 166.

51 Field interview, March 2016.

52 Scott, op. cit., p. 238.

53 Tittensor, ‘Secret Agenda’.

54 Graham E. Fuller, The New Turkish Republic: Turkey as a Pivotal State in the Muslim World (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2008).

55 Yavuz, Islamic Political Identity, p. 213.

56 Cited in Yavuz and Koç, ‘The Turkish Coup Attempt: The Gülen Movement vs. the State’, p. 138.

57 Ibid., p. 136.

58 Ibid.

59 Field interview, April 2014.

60 Field interview, June 2014.

61 Throughout our final interview process after the failed coup attempt, we have learned that in some locations women have started to manage the organizational structures. This is very new for the GM’s management mentality and it is still very rare.

62 Yavuz, Toward an Islamic Enlightenment, p. 86.

63 Hendrick, op. cit., pp. 79, 99–100.

64 Field interview, January 2015.

66 The well-known ‘Abant Meetings’ are a good case in point. Gülen had determined that these meetings would be established from 1998 to facilitate dialogue and establish a strategic link at the global level between the movement and certain sectors. Specifically, the ‘right’ individuals would be chosen to participate, such that the final mix of participants would allow for the appearance of pluralism and at the same time ensuring no particularly ‘critical’ or ‘dangerous’ voices would be present. Gülen’s ‘distance’ from these meetings comports with Hendrick’s extensive discussion of the ‘strategic ambiguity’ of the movement and Gülen’s leadership in particular.

67 Field interview, March 2015.

68 Failed interview, February 2018.

69 See Élise Féron, ‘Transporting and Re-Inventing Conflicts: Conflict-Generated Diasporas and Conflict Autonomisation’, Cooperation and Conflict, 52:3 (2017), pp. 360–376; Sökefeld, op. cit., Bahar Baser, ‘Gezi Spirit in the Diaspora: Diffusion of Turkish Politics to Europe’, in Kumru F. Toktamış and Isabel David (eds) Everywhere Taksim: Sowing the Seeds for a New Turkey at Gezi (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015), pp. 251–266.

70 Yossi Shain, The Frontier of Loyalty Political Exiles in the Age of the Nation-State (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), p. xxiv.

71 Shain, op. cit., p. xvii.

72 In the USA, the GM website ‘Hizmet News’ serves this function, whereas in Sweden the very active ‘Stockholm Center for Freedom’ is at the forefront of efforts to recruit non-members to contribute to the Center’s ‘research and publishing’ efforts, a classic movement practice.

73 Liza Dumovich, ‘Pious Creativity: Negotiating Hizmet in South America after July 2016’, Politics, Religion & Ideology , 19:1 (2018), pp. 81–94, doi:10.1080/21567689.2018.1453267.

74 Anthony Skinner, ‘Turkish Business Suffers under Erdogan’s Post-coup Gulen Purge’, CNBC News (online), 7 November 2016, https://www.cnbc.com/2016/11/07/turkish-business-suffers-under-erdogans-post-coup-gulen-purge.html.

75 James Clifford, ‘Diasporas’, Cultural Anthropology, 9:3 (August 1994), pp. 302–338, https://doi.org/10.1525/can.1994.9.3.02a00040, pp. 305–306.

76 See Angey, op. cit.; Paul Alexander, ‘Turkey on Diplomatic Push to Close Schools Linked to Influential Cleric’, Voice of America, 1 September 2017, https://www.voanews.com/a/turkey-erdogan-gulen-schools/4010073.html.

77 Chanbota Chorn, ‘Turkey’s Anti-Gulen Purge Hits Respected International School in Cambodia’, Voice of America, 3 August 2016, https://www.voanews.com/a/turkey-anti-gulen-purge-hits-respected-international-school-in-cambodia/3447722.html.

78 See Tee, op. cit.