ABSTRACT

The image of ‘the people’ has occupied a central place in the discourse of the contemporary Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) for many years. However, the ROC’s ecclesiastical ‘populism’ has not been systematically analyzed. The study at hand aims to fill this gap by examining the representations of ‘the people’ articulated at the Bishops’ Council of the ROC in the last three decades. Following and modifying Ernesto Laclau and his followers’ approach to studying populism, the analysis of the Council’s documents shows that the official Church plays a dual language game, simultaneously constructing a hegemonic order in Russia and its alleged ‘civilizational space’ and promoting a seemingly counter-hegemonic project in global politics. However, the role of ‘the people’ in this setting is far from Laclau’s conception of radical popular agency. Instead, the Bishops’ Council calls for the preservation of traditional identities and local hierarchies in order to ensure Russia’s continuity and greatness. Thus, the official Church has been contributing to the elitist, statist, and great-power nationalist hegemony in Russia.

Introduction

Today, the most decisive battles are being fought on the spiritual front. [W]e are called to defend the people [narod] on this front, to educate it in faith, in love for the Fatherland, in the ability to resist any imposed standards of life, models of behaviour, and philosophical ideas alien to the Orthodox faith and the historical tradition of our people [nashego naroda].Footnote1

This paper, however, is not about the deep historical roots of the ROC’s political identity, the longue durée of church-state relations in Russia, or the centuries-long ideological sedimentations in the Church’s self-perception as a national institution. Such an array of questions is beyond the scope of a journal article. Moreover, while the historical legacies of the Russian monarchyFootnote6 and the Soviet UnionFootnote7 are certainly important for the ROC’s political positioning, the contemporary Russian Church emerged in a qualitatively different situation vis-à-vis the state and civil society after the collapse of the USSR. The end of the tightly knit entanglement of spiritual and temporal powers and the lifting of the strict state control over religion made of the post-Soviet ROC everything but a historically predetermined political actor. Assessing the Church’s ‘actual’ influence over Russian politics and society, however, is also not among the aims of the study at hand. The existing literature has discussed that at length.Footnote8 This paper’s modest aim is to unpack what is the post-Soviet ROC’s conception of ‘the people’ and what kind of political order such a conception implies.

Indeed, ‘the people’, as Margaret Canovan argues, ‘is undoubtedly one of the least precise and most promiscuous of concepts. For that very reason, however, it has a claim to be regarded as a quintessentially political concept.’Footnote9 In that sense, this study aims to discern the ROC’s politics – its vision of social order, norms, and hierarchy – in light of the image of ‘the people’. Following Foucault’s dictum that ‘there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations’,Footnote10 I will try to determine what knowledge the official ROC produces about ‘the people’ and what power relations this knowledge presupposes and constitutes.

The literature on Orthodoxy and politics in contemporary Russia has focused primarily on the complexities of church-state relations,Footnote11 the ROC’s links to national identity and nationalism,Footnote12 and the Church’s attitude towards human rights, pluralism, and liberalism.Footnote13 Some scholars have examined survey data to shed light on the relationship between Orthodox religiosity and support for democracy,Footnote14 while others have focused on the politicization of Orthodoxy and the ‘Orthodoxization’ of political discourse.Footnote15 Studies of conceptual history have dealt with the broader intricacies of the concepts of natsiya, narod, and narodnost’ in imperial Russia,Footnote16 the Soviet Union,Footnote17 and present-day Russia.Footnote18 However, no one has systematically examined the ROC’s construction of ‘the people’ in the post-Soviet period.

To be sure, the ROC’s political discourse is by no means monolithic – there are many voices within the ChurchFootnote19 and, certainly, many different representations of ‘the people’. In this study, however, I limit the analysis to the official documents adopted by the Bishops’ Council – the highest regularly sitting body of the Russian Church. Although I consider the statements of individual bishops, the sermons of local priests, the opinions of public theologians, the conversations on Orthodox TV channels and radio stations, and the discussions in online forums all important for the overall understanding of politics in the Church, in this study, I can cover here only a tiny fraction of the general discourse. Moreover, the official documents of the ROC represent the most authoritative source of public theology in Russian Orthodoxy and target a much wider audience than the narrower ecclesial discourses. Finally, the collective authorship of these texts presupposes that the Church’s institutional voice encompasses a structural understanding of politics that transcends the particular views of any given hierarch.

Two of the official documents adopted by the Bishops’ Council have sparked considerable scholarly interest: the 2000 Basis of the Social ConceptFootnote20 and the 2008 Basic Teaching on Human Dignity, Freedom, and Rights.Footnote21 However, I take a different approach to analysing these and other official texts. My aim is to unravel what political subjectivities the official Church enables and/or impedes with its discourse on ‘the people’.

In the following sections, I briefly discuss some relevant approaches to studying religion and politics,Footnote22 introduce the theoretical framework for my study, outline the historical background of the ROC’s public engagement, and present the logic behind the data selection. I then examine what ‘the people’ is according to the ROC; about which ‘people’ the Church is talking; whence ‘the people’ with regard to its origin and history; who ‘the people’ is in relation to its Others; and how ‘the people’ is in terms of agency. I conclude by reflecting on ‘the people’s’ purpose in the political universe depicted by the official ecclesiastical discourse.

Existing approaches

Three main analytical trajectories could facilitate research on religious constructions of ‘the people’: the religion and populism scholarship, the analyses of ethnoreligious identities, and the studies of political theology.

The religion-and-populism trajectory tends to focus primarily on the instrumentalization of religious identities by regimes, parties, and politicians,Footnote23 the politicization of religion and sacralization of politics,Footnote24 and on theological responses to ‘populist politics’.Footnote25 Thus, with a few exceptions,Footnote26 relatively little attention has been paid to the constructions of ‘the people’ articulated by religious leaders and organizations. Moreover, the literature on religion and populism has largely overlooked Orthodox Christianity.Footnote27 One prominent exception is Yannis Stavrakakis’ study of religious populism in Greece, in which he employs Ernesto Laclau’s theory of populism to analyse the political discourse of the local Orthodox Church.Footnote28

Orthodoxy’s relation to ‘the people’ has been studied predominantly within the framework of religion and nationalism.Footnote29 Closely related to this framework is the literature on the fusion of ethnic and religious identities.Footnote30 Indeed, plenty has been written on the interconnections between religion, ethnicity and nationalism,Footnote31 but in this study, I would like to take the popular signifier as a theoretical and methodological starting point and, thus, as an object of analysis in its own right.

Studies of political theology have also largely ignored the constructions of the popular in official ecclesiastical discourses, but this approach is better suited for my research questions, for it is concerned with the religious field of knowledge production.Footnote32 According to Kristina Stoeckl, political theology is best understood ‘as the response of a religious tradition, a church or an individual religious thinker, to the changing status of religion in modern society with regard to politics, that is, with regard to the question of how people live together and which laws govern the collectivity’.Footnote33 Further, as Vasilios Makrides explains: ‘it is about a particular [theologically informed] theory of state, society, and law aimed at legitimizing a related social symbolic imaginary’.Footnote34

The concept of political theology can also be defined, following the tradition of Carl Schmitt, as a ‘secularization of monotheistic religious concepts for political theory and practice’.Footnote35 However, such a definition would, again, place the emphasis on the secular applications of religious ideas. Alternatively, I hold that every theology (’secularized’ or not) is always already political, inasmuch as it produces knowledge about human life – knowledge that invariably implies certain social norms and power relations. In that sense, I use the terms secular and religious not as designations of two essentially opposite and unrelated epistemic paradigms, but as markers of historically and institutionally separated fields of knowledge production.Footnote36

What (kind of) populism?

Unlike scholars who treat populism as an ideology,Footnote37 a strategy,Footnote38 a political style,Footnote39 or a repertoire,Footnote40 Ernesto Laclau holds that ‘populism is an ontological and not an ontic category’. Its meaning ‘is not to be found in any political or ideological content entering into the description of the practices of any particular group, but rather in a particular mode of articulation of whatever social, political, or ideological contents may exist’.Footnote41

According to Laclau, any political discourse – that is, any discourse ‘postulating a radical alternative within the communitarian space’ – is by definition populist because it puts ‘into question the institutional order by constructing an underdog as a historical agent – i.e. an agent that is an other in relation to the way things stand’.Footnote42 For Laclau, the crux of the matter lies in populism’s specific logic of articulation. Whereas what he calls the ‘institutionalist discourses’ tend to co-opt and absorb different political demands and identities within an existing hegemonic order, populism draws a ‘political frontier’ between the existing order on the one hand and various unsatisfied demands on the other.Footnote43 To give rise to a unified ‘popular subject,’ Laclau argues, these demands have to be articulated in an equivalential chain brought together by an empty signifier, e.g. ‘the people’.Footnote44 Thus, whereas an institutionalist discourse differentiates and integrates emerging demands/identities within an expanding symbolic totality, a populist discourse revolves around an antagonism whereby various unsatisfied demands and unrecognized identities come together (‘equivalentialized’) under one (‘empty’) name against the system that failed them.Footnote45 In short, institutionalist discourses underpin existing hegemonic formations,Footnote46 whereas populist discourses challenge the latter by advancing counter-hegemonic projects.

These analytical categories are, of course, ideal types (in the Weberian sense). As no hegemonic formation can in practice totalize everything (they all have and need ‘an outside’) and as no counter-hegemonic project can develop ex nihilo and without itself hegemonizing its constituent parts (the various unsatisfied social demands and identities), the institutionalist/differential and the antagonistic/equivalential logics will always operate in some combination. To situate a particular discourse within one category or the other is to establish which logic prevails.Footnote47

Two questions arise. First, can an existing hegemonic narrative portray ‘the people’ as an underdog against an enemy in order to legitimate (rather than subvert) the existing state of affairs? Indeed it can: many hegemonies depend precisely on that. However, is such a discourse institutionalist, or populist? I claim that it can be both if it articulates a radical alternative within a larger social space (e.g. the international arena) while preserving the status quo ‘at home’ (e.g. in domestic politics).

Second, are all radical alternatives of the same nature? Does it matter what kind of image of ‘the people’ a political discourse creates? In On Populist Reason, Laclau discusses in passim the phenomenon of ‘ethno-populism’, claiming that it, too, constructs an antagonistic equivalential chain – albeit ‘drastically limited from the very beginning’, since the ‘signifiers unifying the communitarian space are rigidly attached to precise signifieds’.Footnote48 However, he does not flesh out a populist taxonomy, such as Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser’s distinction between exclusionary and inclusionary populism.Footnote49 Moreover, Laclau insists on the synonymity between populism and politics (understood as politicization),Footnote50 thus overlooking the possibility of phenomena such as politicized ethno-institutionalism, for instance.Footnote51

Whilst ‘drawing heavily on Laclau’s contribution’ to the theory of populism, Benjamin De Cleen and Yannis Stavrakakis propose an analytical distinction within political discourse between ‘populism’ and ‘nationalism’.Footnote52 According to them, ‘populism is structured around a vertical, down/up or high/low axis that refers to power, status and hierarchical socio-cultural and/or socioeconomic positioning’.Footnote53 And they define nationalism as ‘a discourse structured around the nodal point “nation”, envisaged as a limited and sovereign community that exists through time and is tied to a certain space, and that is constructed through an in/out [horizontal] opposition between the nation and its out-groups’.Footnote54 Here again, ‘nationalism’ and ‘populism’ do not represent mutually exclusive categories, although – unlike Laclau’s institutionalist and antagonistic logics – they do not necessarily have to be articulated in some combination. In other words, there can be non-populist nationalism and non-nationalist populism.Footnote55

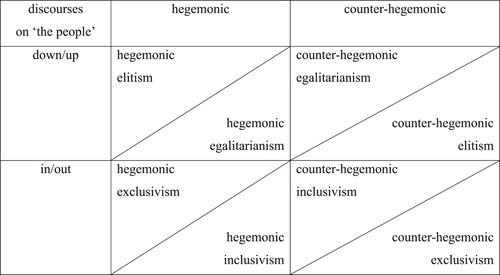

In order to systematize these various conceptualizations and distinctions into a coherent framework and account for the possibility of dual discourses operating differently on different terrains, I introduce the following taxonomy for discourses on ‘the people’:

Two ways of articulating ‘the people’:

- Along the in/out axis – the ‘people’ as a confined community (a nation, tribe, religious community, civilization, etc.)

- Along the down/up axis – the ‘people’ as plebs or an underdog vs. ‘the elites’, ‘the powers that be’, etc.

Two effects of constructing ‘the people’:

- Expanding or preserving the existing order by representing it as desired, normal, and/or natural

- Challenging the existing order by 1) constructing a political frontier, 2) promoting different power relations, and/or 3) advancing alternative political subjectivities

Two primary terrains:

- Internal – the inner social space constructed by a discourse (a state within the international system, a national minority within a country’s population, a local church within the world Orthodoxy, a social class within an economic system, etc.)

- External – the outer or broader social space constructed by a discourse.Footnote56

Thus, we arrive at the following schema (), showing how the down/up and in/out articulations of the ‘the people’ change as a result of their standing vis-à-vis a particular hegemonic order.

Here it should be noted that ‘hegemonic order’ is not an objective given. Hegemony, and any social reality for that matter, is not immediately and transparently accessible: it is perceived and communicated through symbolic representations (not reflections), which are inevitably selective, contingent, and political.Footnote57 While I take ‘order’ as an ontological category – for we all need (relatively) organized and organizing symbolic systems that provide ‘meaning to the otherwise chaotic world’Footnote58 – I maintain that determining whether a certain social arrangement is or is not a specific hegemonic order (or an arrangement at all) presupposes a particular – or ontic – worldview. Likewise, social identities and demands should be treated as ‘contingent discursive constructions and not as the basic units of analysis’ because the realities they represent are always mediated through the intersubjective realm of language.Footnote59

To illustrate this point, take the well-known example of the ‘refugees welcome’ discourse, which, according to the above taxonomy, portrays itself as a counter-hegemonic inclusivist project struggling against the ‘fortress Europe’ hegemony. In turn, the anti-immigration discourse, in the eyes of its proponents, is opposed to the ‘liberal and multiculturalist’ inclusivist hegemony. However, depending on the classifier’s research question and positionality, the ‘refugees welcome’ discourse can be construed as ‘not radical enough’ – for instance, because it is inclusive only towards refugees and not all migrants – and thus, classified as preserving/contributing to the exclusivist global hegemony of ‘border regimes’. Similarly, some anti-immigration discourses can be categorized – at least theoretically – as conducive to the inclusivist hegemony because they discriminate only against ‘illegal immigrants’ and not against ‘documented refugees’.

To complicate things further and include my point about the possibility of dual discourses, I argue that all variants listed in the above classification can be combined in all possible ways when articulated on different terrains, except for those paired in the diagonally split cells. That is because, from the perspective of the same positionality and the same research question, a given discourse cannot be simultaneously hegemonically exclusionary and inclusionary, or counter-hegemonically elitist and egalitarian (and so on) on the same terrain.

Before I classify the ROC’s official discourse on ‘the people,’ let me outline the context of its articulation.

The post-soviet Russian orthodox church

Following decades of systematic oppression in the interwar Soviet Union,Footnote60 the ROC was partially rehabilitated during the Second World War when Stalin sought to utilize its patriotic mobilizing power as part of the resistance to the Nazi invasion.Footnote61 Since then, the Russian Church ‘led a paradoxical, simultaneously privileged and repressed existence in its “golden cage”’.Footnote62 However, in 1988, in the heyday of Gorbachev’s glasnost’ and perestroika, the ROC enjoyed statewide celebrations of the ‘1000th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus’’,Footnote63 which heralded the renewed visibility of the Church in the ‘public square’ following the collapse of the Soviet system.Footnote64

After a brief period of almost unhindered religious pluralism in post-Soviet Russia, the ROC leadership felt threatened by the ‘unleashed religious market’ and lobbied for a special status for Russian Orthodoxy in national legislation.Footnote65 In 1997, the Moscow Patriarchate saw the adoption of the Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations, which recognized Orthodoxy’s ‘special contribution to the history of Russia’Footnote66 and marked the beginning of systematic restriction of ‘spiritual competition’ from ‘non-traditional’ religions.Footnote67 During Putin’s first two terms (2000–2008), the influence of the ROC grew steadily,Footnote68 although he was reluctant to grant the Patriarchate all the concessions it requested.Footnote69 However, many of the latter’s demands (e.g. introduction of religious education in public schools, restitution of church property, reinstating military chaplaincy) were met during the Medvedev presidency.Footnote70 This trend continued and intensified after Putin’s return to the Kremlin in 2012, when Russia experienced a top–down conservative turn,Footnote71 which, among other things, solidified and expanded the public role of the ROC as a bearer of traditional values,Footnote72 civilizational identity,Footnote73 and the people’s memory.Footnote74

The official Church advanced its position through various means. These include a comprehensive media strategy,Footnote75 cooperation with the military,Footnote76 the education sectorFootnote77 and the foreign ministry,Footnote78 as well as the development of close ties with ‘Orthodox-minded’ businesspeople – such as Konstantin MalofeevFootnote79 and Vladimir YakuninFootnote80 – and participation in memory megaprojects like the network of multimedia historical parks ‘Russia – my history’.Footnote81

Although all of the above can be considered part of the Church’s public engagement, the primary articulation of its political theology has developed elsewhere. One key platform has been the World Russian People’s Council (WRPC), a forum headed ex officio by the Russian Patriarch, which gathers representatives of different religions, political institutions, and civil society organizations – all ‘united around the idea of serving the people of Russia and the brotherly peoples of historical Rus’’.Footnote82 Since 1993, the WRPC has published multiple politically oriented addresses (sobornye slova) and documents like the Declaration of Russian Identity.Footnote83 However, notwithstanding Kirill’s often quite visible influence on the WRPC’s documents and the fact that most of them are published on the Patriarchate’s official webpage, these texts are collectively authored (including by people who are not affiliated with the Church) and, thus, can only partially and indirectly count as representative of the ROC’s political theology. At any rate, there is one other platform whose representativeness is undeniable: the Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The bishops’ council

According to the ROC’s Statute,Footnote84 the Bishops’ Council ‘shall be the supreme body of the Russian Orthodox Church’ in ‘defining the character’ of the Church’s relations with ‘states and secular society’.Footnote85 Although this text of the Statute was adopted only in 2013,Footnote86 the Bishops’ Council had been entrusted with the responsibility to ‘express pastoral concern for the problems of modern times’ ever since 1988.Footnote87

The Council consists of diocesan and vicar bishopsFootnote88 from all the ROC’s ‘canonical territory’;Footnote89 and it is to convene no less than once every four years.Footnote90 ‘Theologians, experts, observers, and guests’ may be invited – without, however, having ‘the right of [casting] the deciding vote’.Footnote91 Decisions of the Bishops’ Council ‘shall be taken by a simple majority in an open or secret vote’;Footnote92 the quorum of the Council ‘shall be two-thirds of its member bishops’.Footnote93

In short, the Bishops’ Council is the ROC’s highest authority in formulating ecclesiastical positions on political and social issues. It is a collective body that takes decisions by vote, often unanimously. If the ecclesiastical hierarchy could speak with one voice, that would be the voice of the Bishops’ Council.

From the first Council after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1992 until the latest one in 2017, the ROC’s bishops have issued multiple appeals, resolutions, and public statements and have addressed various politicians and institutions in open letters. In addition to all such texts that articulate ‘the people’ in one way or another, I also examine the Council reports of Patriarchs Alexy II (1990–2008) and Kirill (2009–). Although not expressing the Church’s standing in the same manner as the conciliar documents, these reports demonstrate how the ROC’s most authoritative voice – that of the patriarch – elaborates on collectively articulated positions. The nature of these reports differs from the statements given by Alexy and Kirill in other contexts because of the imperative to comply with the unifying spirit of the Councils.

Now, let me move on to the discussion of how the Bishops’ Councils have constructed the image of ‘the people’.

What is ‘the people’?

‘People’ (narod) is the ‘basic unit of analysis’ of the ROC’s political theology: a self-evident, natural, and fundamental reality of human life. At the same time, the popular signifier has several distinct meanings in the Church’s official discourse. Its first denotation is related to the notions of family and siblinghood, where narod appears to be an organic extension.Footnote94 This comes as no surprise, as narod is rooted in the Russian word for kin (rod). However, the ROC’s Social ConceptFootnote95 also underlines that ‘the community of the children of God’ is a ‘new people’ (novogo naroda), the unity of which is ‘secured not by its ethnic, cultural or linguistic community, but by their common faith in Christ and Baptism’.Footnote96 In spite of that, the hierarchs argue that their ‘Church unites in herself the universal with the national [natsional’nym]’.Footnote97 Here ‘the national’ is linked to the concept of ‘earthly homeland’ (ibid.), which derives its meaning from the dichotomy between the earthly and heavenly homeland, whereby the latter is understood as the Jerusalem ‘which is above’,Footnote98 i.e. the Kingdom of God. As opposed to this eschatological dimension, ‘earthly homeland’ is explained through an example from Christ’s life:

The Lord Jesus Christ […] identified Himself with the people [narodom] to whom He belonged by birth. Talking to the Samaritan woman, He stressed His belonging to the Jewish nation [iudeiskoi natsiiFootnote99]: ‘Ye worship ye know what: we know what we worship: for salvation is of the Jews’ (Jn. 4:22). [At the same time] Jesus was a loyal subject of the Roman Empire and paid taxes in favour of Caesar (Mt. 22: 16-21).Footnote100

When a nation [natsiya], civil or ethnic, represents fully or predominantly a monoconfessional Orthodox community, it can in a certain sense be regarded as the one community of faith—an Orthodox nation [narod].Footnote103

Here we see how the idea of a ‘spiritual community’ transcends the narrowly defined boundaries of ethnic/civic nationhood and comes to encompass a transborder and multi-ethnic Fatherland – later called Orthodox civilization, Russian World, or Holy Rus’.Footnote106 Further, the implied homology between kinship/citizenshipFootnote107 on the one hand and spiritual fellowship on the other allows the Church to treat entire peoples as (parts of) its flock while, at the same time, considering that flock as one ‘indivisible spiritual community’Footnote108 – or as one people.

‘Spiritual unity’ can even cut across religious boundaries. For instance, in his 2008 report, Patriarch Alexy spoke of ‘the mass forced famine of 1932–1933 that struck Ukraine, the Volga region, the North Caucasus, the Southern Urals, Western Siberia and Kazakhstan.’ The ‘memory of the victims,’ Alexy argued, ‘should serve not as a pretext for political speculations, but as an impetus for the spiritual unity of the peoples who share common history and destiny’.Footnote109 Thus, what comes to define the ‘spiritual unity’ of these religiously diverse people is not any particular creed but their allegedly shared ‘sacred’ memory.

These three dimensions of the popular – kinship, citizenship, and spiritual/mnemonic fellowship – enable the official Church to speak about ‘the people’ on multiple levels and scales. In turn, the ROC assumes the role of speaking on behalf of:

its ‘churched’ members (votserkovlennye) – in the strictly ecclesial sense

entire peoples ‘historically confessing Orthodoxy’Footnote110 – in an ethnoreligious sense

a larger supra-ethnic and inter-state ‘age-old community’ or a ‘civilization’ – in the sense of shared political history and memory

citizens of the states considered part of the ROC’s canonical territory.

At the same time, the Council documents tend to transfer the logic of one level/scale to another. Thus, the ROC could, for instance, take responsibility for voicing concerns about the ‘spiritual well-being’ of religiously diverse societies, regard ethnically heterogeneous bodies politic as ‘fraternal nations’,Footnote111 and frame nations with very different histories and memories as belonging to one ‘common civilizational space’.Footnote112

In addition, the Council personifies ‘the people,’ and even attributes ‘a soul’ to it.Footnote113 Perhaps the most vivid example of this personification of narod comes from the 2011 Statement on the Life and Problems of Indigenous Small Peoples:

God gives each human being windividual abilities through the unfolding of which he acquires the meaning of his earthly life. Likewise, every people [narod] is originally given an identity [samobytnost’], which it must reveal in the course of its history and thus fulfil its historical destiny.Footnote114

Which people?

Notwithstanding the often vague and all-encompassing use of ‘the people’ in the Council’s documents, the popular signifier does carry concrete meanings. Thus, up to 2004 – the year of the Orange Revolution in Ukraine – the ROC’s bishops articulated narod predominantly along the down/up axis, stressing socioeconomic issues such as poverty, unemployment, and inequality. This vertical representation gradually faded; and following 2004, gave way almost exclusively to in/out articulations. Let me examine these dynamics in more detail.

In the 1990s, the Russian Orthodox Church identified the PeopleFootnote115 as the ‘underdog’ – the poor and the suffering. In its Appeal to All Who Are Far and Near, the Bishops’ Council declared: ‘Our Church is materially weak, and so is our people. [We have] become the Church of the poor’.Footnote116 Indeed, the ROC’s hierarchs universalized the hardships of particular social groups and named these groups together narod – two discursive operations that Laclau defined explicitly as pertaining to populism:Footnote117

Orphans and disabled people, the elderly and large families, the unemployed and those who have had to leave their homes – all should be cared for. After all, their suffering is the suffering of the entire people [vsego naroda].Footnote118

Freedom of movement […] is restricted to the rich, as most people cannot afford the luxury of travelling to visit family and friends. Education […] is, in many cases, inaccessible to those who cannot afford to pay for their education. The situation in the country is such that only a limited number of people are able to benefit, while the majority are below the poverty line. The gap between the rich and the poor has reached a critical ratio, which, in effect, is likely to erode the equality of civil rights in the country.Footnote121

In the following years, the Council’s discourse increasingly articulated the down/up representations of the People alongside in/out ones. For instance, in his 1997 report, Patriarch Alexy lamented the ‘heavy burden on pensioners, disabled people, orphans, families with many children, refugees and internally displaced persons’ and deplored the fact that ‘in Russia, between a quarter and a third of the population live below the poverty line’.Footnote125 However, this inclusive approach faded literary in the report’s next sentence, where the Patriarch bemoaned the decreasing population size and life expectancy of ‘the primordially [iskonno] Orthodox peoples’.Footnote126

Following the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine, the Council’s discourse shifted decisively towards a civilizational representation of the popular. The new Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko’s (2005–2010) policy of emancipation from Moscow facilitated a renewed push for Kyiv’s ecclesiastical independence.Footnote127 The ROC establishment saw these developments as a major threat, as some 40% of its parishes were located in Ukraine at the time.Footnote128

Thus, by 2008, the hitherto secondary signifiers ‘age-old community’Footnote129 – ‘peoples of the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Baltic States’,Footnote130 ‘three fraternal Slavic peoples’,Footnote131 and ‘the primordial territory of our Church’Footnote132 – merged and transformed into the master signifier ‘Holy Rus’’.Footnote133 This was defined as the ‘spiritual community’ of ‘the peoples nourished by the Russian Orthodox Church’Footnote134 and as ‘a Homeland for all of us, our common civilizational space’.Footnote135 Thus, Holy Rus’ incorporated both the communal, ethnoreligious dimension and the dimension of (the former) territorial power – for without power (or traces of a shared political history), there cannot be a common civilizational space.

Indeed, according to the official Church, Holy Rus’ is not a twenty-first-century phenomenon. It is claimed to be a community of yore that has bound together the destinies of the ‘primordially Orthodox’ Slavic peoples and, apparently, also the destinies of all non-Orthodox (and non-Slavic but Orthodox peoples, like the Moldovans) who happened to live in the Russian ‘civilizational space’ – ‘from the White to the Black Sea and from Kaliningrad to the Pacific Ocean’.Footnote136 Just how did Holy Rus’ emerge, and where is it headed, according to the Church officials?

Whence the people?

The Bishops’ Council documents from the 1990s did not feature any account of the People’s history, except for the assertion that the ‘spiritual community’ was indeed ‘historical.’ To be sure, key ROC speakers, such as the then-Metropolitan Krill,Footnote137 spoke about the origins of the ‘thousand-year-old historical community of peoples’ literally weeks after the formal dissolution of the USSR.Footnote138 However, the genealogical narrative about Holy Rus’ entered the Council’s discourse only in the new millennium. Thus, in 2004 Patriarch Alexy reported:

On June 1, 2001, we sent a message to the participants of the Congress of the Peoples of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. In this message, [we] emphasized that our peoples were baptised in the same baptismal font more than a thousand years ago and still feel their inseparable spiritual community.Footnote139

Furthermore, according to the Bishops’ Council, the ‘Dnieper baptismal font became our peoples’ common source of asceticism and spiritual life, statehood and Christian culture. Here Holy Rus’ was born.’.Footnote140 The link between ‘common baptism’ and statehood (gosudarstvennost’) is particularly noteworthy:Footnote141 not only does it trace the ‘birth’ of a common political community back to a single religious ‘event,’ it also fuses in the figure of Grand Prince Vladimir the roles of a national and a ‘spiritual leader of the Russian people [russkogo naroda Footnote142] on the road to salvation’.Footnote143 The logical conclusion is evident: the ‘common baptism’ carried out by the unitary state led to the ‘natural, centuries-old relations [among the peoples of Rus’] in the fields of economy, politics, culture, science and trade’.Footnote144

Besides anachronism, personification, and transhistoricity, the narrative about the People’s temporality features one more element: teleology. Memories of the ‘age-old community’ would have meant nothing if they were to remain simply a recollection of the past. Far from being objective and transparent accounts of history, memories are always retroactive and contingent on a particular perception of the present in light of an imagined future. As Patriarch Alexy declared in 2008, ‘the peoples under the spiritual guidance’ of the ROC ‘share a common history and a common destiny’.Footnote145 The Baptism of Rus’, the story goes, ‘determined their historical path’Footnote146 towards the telos of unity.

Who is the people?

If the question of ‘which’ involves specifying the People from a definite set – whether it be a horizontal set of peoples, faiths, and/or territories or a vertical one of socioeconomic groups – the question of ‘who’ relates to the discursive operation of subject positioning. As Kevin Dunn and Iver Neumann argue, ‘one can uncover the process of subject positioning by interpreting the ways in which text(s) work to create a knowable reality by linking subjects and objects to one another in particular ways. What defines a particular subject is the relative relationships that are constructed between it and other subjects.’Footnote147

In the following sections, I examine first, how narod is represented as an object of various subjectivities and then, how it is constructed as a subject position in its own right.

Church, state, and others vis-à-vis the People

Although the Council’s discourse tends to equate Church and People, on the one hand, and People and Fatherland, on the other, these three ‘entities’ are narrated as having a particular set of relationships. They all pertain to (or share the essence of) a singular, totalizing Holy Rus’, while also interacting with one another in certain ways. What is the nature of this trilateral relationship?

The popular Church

According to the ROC’s social doctrine,Footnote148 the Orthodox Church ‘consists of many Autocephalous National [pomestnykh: localFootnote149] Churches’. In turn, the bishops see the role of the national church as ‘sharing the joys and hardships of her people [svoego naroda]’,Footnote150 educating ‘the faithful in the spirit of patriotism’,Footnote151 ‘interceding [pechalovanie] with the government for the needs of the people [nuzhdakh naroda]’,Footnote152 and encouraging ‘the tendencies for unification of countries and nations [stran i narodov], especially those with common history and culture’.Footnote153

Furthermore, in 2004, the Council asserted: ‘Orthodoxy has had a decisive influence on the formation of national culture, statehood, and the moral and social ideals of the peoples traditionally nurtured by our Church’.Footnote154 In 2000, Patriarch Alexy even argued that the Church ‘was the spiritual and moral support which helped [the People] to overcome the mighty enemy during the Great Patriotic War and made possible the impressive achievements of the Soviet Union in the economic, political, social, scientific, military and many other fields’.Footnote155

In sum, the ROC’s self-identification as a popular institution presupposes three main socio-political functions: formation, representation, and unification of the People. The bishops describe Orthodoxy as a decisive force that has laid the foundations of Rus’ political community. Moreover, in their view, the Church has given that community the strength to fight enemies and prosper throughout history. On that basis, the ROC assumes the role of a representative ‘interceding for people [za lyudei] before the powers-that-be’.Footnote156 Finally, the ecclesiastical leadership sees the Church as the epitome of the People’s common history and culture and as the bearer of its shared values. Thus, ‘tradition’, embodied by the ROC, comes as that which makes Holy Rus’ both ‘holy’ and Rus’.

However, ‘tradition’ appears to be important only insofar as it supplies Holy Rus’ with meaning and legitimacy. The Church’s rituals, customs, and heritage matter in this context only inasmuch as they underpin Russia’s claim for historical continuity and civilizational distinctiveness. ‘Civilization’ is what makes ‘tradition’ meaningful, not the other way around. And civilization is inextricably linked with power (vlast’), which, in the ROC’s official discourse, is synonymous with the State.

The (Orthodox) state

The State features variously in the Council’s documents. On the one hand, it ‘exists for the purpose of ordering worldly life’,Footnote157 as ‘an opportunity’ granted by God to ‘human being[s] […] to order their social life by their own free will’.Footnote158 On the other hand, the ROC’s official discourse consistently represents the State as an independent phenomenon, ontologically separate from the People.Footnote159 The reification becomes transparent when the Council or the Patriarch use the signifier ‘those in power,’Footnote160 making it clear that it is not the People who is (supposed to be) in power. The latter, as we have seen, is only to be interceded for (by the Church) before the authorities – not represented in decision-making bodies (by elected officials, for instance). Thus, the bishops of the ROC promote a Hobbesian vision of the State whereby people, ‘by their own free will’, grant to an ‘authority’ the prerogative to organize their common life and to protect them from the state of nature – ‘the earthly reality distorted by sin’.Footnote161

The purpose of ‘state power’ is to take care of people’s ‘earthly well-being’.Footnote162 However, the State should also support the Church’s ‘salvific mission’ because ‘earthly well-being is unthinkable without respect for certain moral norms’.Footnote163 Indeed, the ecclesiastical leadership ‘reminds’ the secular authorities to take care of ‘both the material and spiritual welfare of society’.Footnote164 Thus, the Leviathan is called upon to ‘resist sin’ by force, that is, by ‘coercion and restriction’.Footnote165

Moreover, although the ROC’s hierarchs have posited that the State ‘has no part in the Kingdom of God’,Footnote166 they still employ the concept of ‘Orthodox state.’ An Orthodox State, in their view, is ‘a state that recognises the Orthodox Church as the greatest people’s shrine’.Footnote167 In 2008, the circle came full as the Bishops’ Council declared that ‘the unity of Holy Rus’ is the greatest treasure of our Church and our peoples’.Footnote168 In fact, this mutual referentiality between the (Orthodox) State and the (state-civilizational) Church is not merely a logical fallacy. Both parts of this circular articulation refer to the People, thus constructing a background knowledgeFootnote169 about its devotion and loyalties.

Others

However, civilizational unity is not guaranteed. According to the ROC bishops, Holy Rus’ ‘integrity [tselostnost’] has been repeatedly challenged. Over the centuries, many forces have tried to destroy or radically reshape this [civilizational] space’.Footnote170 In 2009, when Viktor Yushchenko was still in power, Patriarch Kirill accused ‘certain political forces’ in Ukraine of attempting to dismantle ‘church unity’ and ‘to rewrite the history of countries and peoples’.Footnote171 A few years later, following the Euromaidan uprising which toppled the pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych (2010–2014), the Patriarch denounced the ‘people who have abandoned Christian principles [and who] bring tragic and sometimes bloody divisions to the people of Ukraine’,Footnote172 referring to the then-ongoing War in Donbas. Indeed, according to the Holy Rus’ narrative, Russia and Ukraine belong to the same inner social space, so any attempt to question Kyiv’s belonging to the ‘Russian world’ is deemed divisive for Ukrainian society itself. Thus, the official ecclesiastical discourse has constructed Holy Rus’ as a besieged fortress threatened by both external forces and traitors from within.

However, ‘civilizational integrity’ was not the only ‘unity’ under assault. In 2011, a cycle of protests erupted across Russia, triggered by electoral fraud and Vladimir Putin’s bid for a third presidential term.Footnote173 In his 2013 Council Report, Patriarch Kirill described the demonstrations as menacing the unity between the People and the State:

We all remember well the unrest and turmoil that arose at the turn of 2011–2012 [when] the confrontation between a part of society and the state authorities could have well developed into a new and dangerous turmoil, similar to those that have repeatedly brought trouble to the Fatherland and the Orthodox people [pravoslavnomu narodu]. The position of the Russian Orthodox Church, which has always called for the peaceful and progressive development of the lives of the people [narodnoi zhizni], and for constructive dialogue between the people and the authorities [naroda i vlasti] based on mutual respect for each other, was extremely irritating to certain forces wishing to shake the foundations of state and public life.Footnote174

However, while the official ROC tirelessly defended the established order in Russia and contributed to the preservation/expansion of Moscow’s hegemony in the ‘Russian world’, the ecclesiastical discourse on world politics followed a different logic. Already with the 2000 Social Concept, the hierarchs challenged the global economic status quo:

[M]any positive fruits of the globalisation are available only to nations comprising a smaller part of humanity, but having a similar economic and political system. Other nations to whom five sixths of the global population belong have found themselves on the margins of the world civilisation.Footnote175

Furthermore, the bishops’ criticism of international inequality was fused with a denunciation of the ‘spiritual and cultural expansion [of the globalist elites] fraught with total unification’.Footnote178 According to the Social Concept, this trend must be ‘opposed through the joint efforts of the Church, state structures, civil society and international organisations’ for the sake of protecting ‘the identity of nations and other human communities’.Footnote179 At the same time, the Concept declared that ‘the Church welcomes the tendencies for unification of countries and nations, especially those with common history and culture’.Footnote180 In sum, the ROC has been promoting hegemonic elitism and inclusivism on Russia’s allegedly inner ‘civilizational’ terrain, while fostering on the external global terrain a pseudo-counter-hegemonic economic egalitarianism and identitarian exclusivism. But what has happened to popular agency?

How is the people?

The Bishops’ Council represents the People as ‘long-suffering’ (mnogostradal’nyi) but also strong enough to overcome enemies and reject false foreign teachings.Footnote181 The People have shown a great ‘capacity for self-restraint in the name of love and service to God’.Footnote182 However, the most important popular quality is the love of the Fatherland. The ROC calls ‘upon her children to love their homeland on earth [zemnoe otechestvo] and not to spare their lives to protect it if it was threatened’.Footnote183 The Social Concept quotes’ St. Philaret of Moscow, who, ‘during the war with the French aggressors […] said to his flock:’

If you avoid dying for the honour and freedom of the Fatherland [Otechestva], you will die a criminal or a slave; die for the faith and the Fatherland and you will be granted life and a crown in heaven.Footnote184

The patriotism of the Orthodox Christian should be active. It is manifested when he defends his fatherland against an enemy, works for the good of the motherland [otchizny], cares for the good order of people’s life [narodnoi zhizni] through, among other things, participation in the affairs of government. The Christian is called to preserve and develop national culture and people’s self-awareness.Footnote185

In addition, when the Church discourse shifts from describing preservative agency (defence of the Fatherland, protection of national culture and traditional values) to more productive agency (civic participation), the agent also changes from the collective People to the individual. True, the Social Concept does not exclude the possibility of ‘corporate’ participation of Orthodox laity ‘in the work of governmental bodies and political processes’.Footnote187 However, in this context, the Orthodox Christians are seen not as ‘the People’, but rather as an interest group. In addition, they are advised ‘to consult the Church authorities and to co-ordinate their actions in implementing the Church’s position on public issues’.Footnote188 A similarly individualizing and fragmentizing logic is evident also in the ROC’s Basic Teaching on Human Dignity, Freedom, and Rights:

In the history of the peoples nurtured by the Russian Orthodox Church, there has been a productive conception of the need for cooperation between government [vlasti] and society. Political rights can fully serve such a principle of state–society relations. This requires real representation of the interests of citizens at the various levels of government and the provision of opportunities for civic action.Footnote189

Individual human rights cannot be opposed to the values and interests of the Fatherland, the community and the family. Exercising human rights must not be a justification for infringing on religious sanctities, cultural values or the identity of a people. Footnote191

If the Church and her holy authorities find it impossible to obey state laws and orders […] they may […] call upon the people to use the democratic mechanisms to change the legislation or review the authority’s decision, apply to international bodies and the world public opinion and appeal to her faithful for peaceful civil disobedience.Footnote193

Why the people?

To summarize the findings so far, the ROC’s political theology of ‘the people’ is structured around five main discursive threads. On the global terrain, the official Church advocates for (1) popular-civilizational particularism and (2) equality between the peoples/civilizations. On the domestic level, it promotes (3) the naturalization of the socio-economic divisions in society and participates in (4) the reification of the State by representing it as a God-given phenomenon and not as a product (and a system) of human power relations. Finally, the official ecclesiastical discourse constructs (5) a hegemonic inner social space – Holy Rus’ – that subsumes and totalizes various other political, social, religious, and ethnic identities.

Despite the apparent tensions between outer counter-hegemonic egalitarianism and exclusivism on the one hand and inner hegemonic elitism and inclusivism on the other, these different trajectories function as communicating vessels. In order to make sense of, preserve, and expand their power in Russia and the ‘civilizational space of Holy Rus’, the ruling Russian elites – including the higher echelons of the ROC – need to articulate a broader counter-hegemonic narrative. However, the Church’s traditionalism and civilizationism hardly present a radical alternative to what the hierarchs see as the liberal, secular, and globalist hegemonic project of the Western cosmopolitan elites. Such an alternative would have to be itself global, universal, and populist in the Laclauian sense of constructing a singular worldwide ‘underdog’ as a historical subject subverting the established order.

Instead, the ROC’s political theology has been defensive, conservative and depoliticizing. It displaces internal social tensions onto the external terrain of world politics without even presenting a counter-hegemonic project for that broader social space. In that context, the purpose of the People is ‘to preserve its identity and culture’ in order to ensure Russia’s ‘existence as a strong, internationally respected state’.Footnote195 The People here is not a demos – the subject of popular sovereignty – but a collective agent of Russia as a great power. The Church’s flock is not the body of Christ but the body of Holy Rus’ as a civilization. Narod is not the name of the plebs that see themselves as the populus – the wronged part that aspires to take the place of the wholeFootnote196 – but the designation of the ‘civilizational organism’ whose purpose is to transmit and perpetuate Russia’s authenticity and greatness. In sum, by speaking about and on behalf of ‘the people’ over the past three decades, the official Church – through its Bishops’ Council – has hindered the emergence of radical collective subjectivity and itself contributed to the elitist, statist, and great-power nationalist hegemony in Russia.

Conclusion

In this study, I have tried to unpack the Russian Orthodox Church’s political vision by analysing its discourse on ‘the people’. My aim was to find out what political subjectivities the ROC’s ecclesiastical ‘populism’ enables and what possibilities for collective action it impedes. I discovered that the knowledge produced by the official Church about ‘the people’ presupposes an elitist order in which ‘the poor’ lack any agency, while ‘the State’ bears the responsibility to alleviate the gravest economic frustrations without disturbing the power relations in society. Furthermore, I established that the ROC’s bishops ascribe to ‘the people’ only preservative agency (defence, loyalty, and service to ‘the Fatherland’) while assigning to ‘the State’ the subject position of ‘resisting sin’ by violence. In this context, the Church exercises the role of the popular representative mediating between vlast’ and narod. What is more, the official ecclesiastical discourse claims that it is the ROC’s ‘decisive influence’ that enabled the very historical formation of the Russian people and statehood, and thus, the Church acts as a natural unifier of ‘historical Rus’. Finally, the documents of the Bishops’ Council have been setting a great-power nationalist agenda through their advocacy for the reunification of ‘Holy Rus’ civilizational space’ around Russia’s hegemony, thus actively working against the subjectivization of political communities such as Ukraine.

All this shows that the ROC’s political theology has contributed to the discursive institutionalization of the current hegemony in Russia and has given Moscow’s hegemonic project in the former Soviet space ‘spiritual’ and mnemonic legitimation. A constitutive part of this legitimation has been the construction of Holy Rus’ as an underdog struggling for its integrity and authenticity against the globalist hegemonic order. However, this discourse does not amount to a populist counter-hegemonic project but rather to a programme for the fragmentation of the world into ‘civilizational’ hegemonic orders where the local ‘traditional’ elites enjoy full sovereignty.

By analysing the ROC’s discourse on ‘the people’, this study has contributed to both the empirical research of religion and politics and the theoretical discussion on populism. Here I have focused on the often-overlooked religious articulations of the popular, especially the Orthodox Christian ones. Furthermore, I have applied Ernesto Laclau’s approach to populism to a new field – Russian Orthodoxy – and have demonstrated how his theory can be expanded and modified to account for more complex political discourses. I have devised a novel formal classification of ‘populist’ discourses and have shown how it can be employed in practice.

What remains unaddressed in this study is why the ROC has constructed this kind of ‘people’ in that particular way. Here, I will offer only a hypothesis, which will remain to be examined in future research. I reckon that between the early 1990s and around 2009, when Metropolitan Kirill became patriarch, the ROC was gradually ‘colonised’ by great-power nationalist clerics who acted on behalf of a great power that did not even (claim to) exist at the time. Thus, Kirill and his like-minded ecclesiastics, far from being a tool in the hands of Putin’s regime, have actively made the latter possible. The ROC’s great-power nationalism is not a product of the regime’s control over the Church but rather a condition of possibility for the emergence of the regime itself (albeit one among many and not a sine qua non). The ROC is subordinated, however, not necessarily to the current political establishment as such but to the broader hegemonic order that the ecclesiastical elites have helped institutionalize in Russia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bojidar Kolov

Bojidar Kolov is a doctoral research fellow in Russian Studies at the University of Oslo (Norway) and a theology student at the Sankt Ignatios College in Stockholm (Sweden). He completed a Master’s program in European Union - Russia Studies at the University of Tartu (Estonia) and a Bachelor’s in Political Science at Sofia University (Bulgaria). Bojidar’s research interests lie primarily in the areas of religious nationalism, church-state relations, and political theology.

Notes

1 ‘V kanun Dnya Pobedy Patriarkh Kirill vozlozhil venok k mogile Neizvestnogo soldata u Kremlevskoi steny’ [‘On the eve of Victory Day, Patriarch Kirill laid a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier near the Kremlin Wall’], Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2022, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/5924186.html.

2 The Tale relates the story of St Sergius of Radonezh blessing Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoy before the 1380 Battle of Kulikovo, see Kati Parppei, The Battle of Kulikovo Refought: ‘The First National Feat’ (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp. 46–49, 72–76.

3 See Liubov Melnikova, ‘Orthodox Russia against “Godless” France: The Russian Church and the “Holy War” of 1812’ in J. M. Hartley, P. Keenan, and D. Lieven (eds) Russia and the Napoleonic (Wars, War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850) (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 179–195 and Steven Merritt Miner, Stalin’s Holy War - Religion, Nationalism, and Alliance Politics, 1941–1945 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

4 See Sophie Kotzer, Russian Orthodoxy, Nationalism and the Soviet State during the Gorbachev Years, 1985–1991 (London and New York: Routledge, 2020).

5 For a classic overview, see Robert L. Nichols and Theofanis George Stavrou (eds) Russian Orthodoxy under the Old Regime (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1978).

6 See Richard Pipes, Russia under the Old Regime (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974) and Gregory L. Freeze, ‘Handmaiden of the State? The Church in Imperial Russia Reconsidered’, The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 36:1 (1985), pp. 82–102.

7 See Nathaniel Davis, A Long Walk to Church: A Contemporary History of Russian Orthodoxy (London and New York: Routledge, 2018) and Georgii Mitrofanov, Ocherki Po Istorii Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi XX Veka [Essays on the History of the Russian Orthodox Church of the 20th Century]. (Moscow: Praktika, 2021).

8 See Irina Papkova, The Russian Orthodox Church and Russian Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Zoe Knox and Anastasia Mitrofanova, ‘The Russian Orthodox Church’ in Lucian Leustean (ed.) Eastern Christianity and Politics in the Twenty-First Century (London and New York: Routledge), pp. 38–66, and Tobias Köllner, Religion and Politics in Contemporary Russia: Beyond the Binary of Power and Authority (London and New York: Routledge, 2021).

9 Margaret Canovan, The People (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2005), p. 140.

10 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), p. 27.

11 See John Anderson, ‘Putin and the Russian Orthodox Church: Asymmetric Symphonia?’ Journal of International Affairs, 64:1 (2007), pp. 185–201 and Kristina Stoeckl, ‘Three Models of Church-State Relations in Contemporary Russia’ in Susanna Mancini (ed.) Constitutions and Religion (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2020), pp. 237–251.

12 See Zoe Knox, Russian Society and the Orthodox Church: Religion in Russia after Communism (London and New York: Routledge, 2005); Aleksandr Verkhovskii, ‘The Russian Orthodox Church as the Church of the Majority’, Russian Politics & Law, 52:5 (2014), pp. 50–72, and Jocelyne Cesari, ‘Orthodoxy: Between Nation and Empire’ in Jocelyne Cesari (au.) We God’s People: Christianity, Islam and Hinduism in the World of Nations (Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp. 240–317.

13 See Kristina Stoeckl, The Russian Orthodox Church and Human Rights (London and New York: Routledge, 2014) and Denis Zhuravlev, ‘Orthodox Identity as Traditionalism: Construction of Political Meaning in the Current Public Discourse of the Russian Orthodox Church’, Russian Politics & Law, 55: 4–5 (2017), pp. 354–375.

14 See Christopher Marsh, ‘Orthodox Christianity, Civil Society, and Russian Democracy’, Demokratizatsiya, 13:3 (2005), pp. 449–462 and Olga Balakireva and Iuliia Sereda, ‘Religion and Civil Society in Ukraine and Russia’ in Joep De Hart, Paul Dekker, and Loek Halman (eds.) Religion and Civil Society in Europe (New York and London: Springer 2013), pp. 219–250.

15 See Anastasia Mitrofanova, The Politicization of Russian Orthodoxy: Actors and Ideas (Stuttgart: ibid-Verlag, 2005).

16 See Alexey Miller, ‘Natsiia, Narod, Narodnost’ in Russia in the 19th Century: Some Introductory Remarks to the History of Concepts’, Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, 56:3 (2008), pp. 379–390.

17 See Anna Whittington, ‘Making a Home for the Soviet People: World War II and the Origins of the Sovetskii Narod’ in Krista Goff and Lewis Siegelbaum (eds) Empire and Belonging in the Eurasian Borderlands (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), pp. 147–161.

18 See Oxana Shevel, ‘Russian Nation-Building from Yel’tsin to Medvedev: Ethnic, Civic or Purposefully Ambiguous?’, Europe-Asia Studies, 63:2 (2011), pp. 179–202 and Helge Blakkisrud, ‘Russkii as the New Rossiiskii? Nation-Building in Russia After 1991’, Nationalities Papers, 51:1 (2023), pp. 64–79.

19 See Kristina Stoeckl, Russian Orthodoxy and Secularism (Leiden: Brill, 2020), pp. 36–47.

20 See Wil van den Bercken, ‘A Social Doctrine for the Russian Orthodox Church’, Exchange, 31:4 (2002), pp. 373–385; Katja Richters, The Post-Soviet Russian Orthodox Church: Politics, Culture and Greater Russia (London and New York: Routledge, 2013), pp. 18–35, and Alexander Agadjanian, Turns of Faith, Search for Meaning Orthodox Christianity and Post-Soviet Experience (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2014), pp. 113–132.

21 See Agadjanian, Turns of Faith, op. cit., pp. 157–174 and Stoeckl, The Russian Orthodox Church and Human Rights, op. cit., pp. 69–90.

22 For a broader overview, see Carsten Bagge Laustsen, ‘Studying Politics and Religion: How to Distinguish Religious Politics, Civil Religion, Political Religion, and Political Theology’, Journal of Religion in Europe, 6:4 (2013), pp. 428–463.

23 See Nadia Marzouki, Duncan McDonnell, and Olivier Roy (eds.) Saving the People: How Populists Hijack Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016); Rogers Brubaker, ‘Between Nationalism and Civilizationism: The European Populist Moment in Comparative Perspective’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40:8 (2017), pp. 1191–1226, and Daniel Nilsson Dehanas and Marat Shterin, Religion and the Rise of Populism (London and New York: Routledge, 2021).

24 See Jose Pedro Zúquete, ‘Populism and Religion’ in Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 445–466; Andrew Arato and Jean L. Cohen, ‘Civil Society, Populism, and Religion’ in Carlos de la Torre (ed.) Routledge Handbook of Global Populism (London: Routledge, 2018), pp. 98–112, and Efe Peker and Emily Laxer, ‘Populism and Religion: Toward a Global Comparative Agenda’, Comparative Sociology, 20:3 (2021), pp. 317–343.

25 See Maria Armida Nicolaci, ‘The “People of God” and Its Idols in the “One and Other” Testaments: How Sacred Scripture Challenges Populist Rhetoric’. Concilium 74:2 (2019), pp. 74–88; Tobias Cremer, ‘Nations under God: How Church–State Relations Shape Christian Responses to Right-Wing Populism in Germany and the United States’, Religions 12:4 (2021), p. 254, and Ulrich Schmiedel and Joshua Ralston, The Spirit of Populism: Political Theologies in Polarized Times (Leiden: Brill, 2021).

26 See William McCormick, ‘The Populist Pope? Politics, Religion, and Pope Francis’, Politics and Religion, 14:1 (2021), pp. 159–181; Jonathan Chaplin, ‘A Political Theology of “the People”: Enlisting Classical Concepts for Contemporary Critique’ in Schmiedel and Ralston (eds) The Spirit of Populism, op. cit., pp. 229–243, and Ivan Tranfić, ‘Framing “Gender Ideology”: Religious Populism in the Croatian Catholic Church’. Identities, 29:4 (2022) pp. 466–482.

27 See Kathy Rousselet, ‘Russian Orthodox Imaginaries and Their Family Resemblance to Populism’, Journal of Religion in Europe, 16:2 (2023), pp. 172-198.

28 Yannis Stavrakakis, ‘Antinomies of Formalism: Laclau’s Theory of Populism and the Lessons from Religious Populism in Greece’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 9:3 (2004), pp. 253–267

29 For a comprehensive overview, see the special issue Paul Meyendorff (ed.) ‘Ecclesiology and Nationalism’, St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly, 57:3–4 (Crestwood, NY, 2013).

30 See Craig R. Prentiss (ed.), Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity: An Introduction (New York: NYU Press, 2003)

31 For a relevant study on Russia, see Vyacheslav Karpov, Elena Lisovskaya, and David Barry, ‘Ethnodoxy: How Popular Ideologies Fuse Religious and Ethnic Identities’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51:4 (2012), pp. 638–655.

32 See Hans-Peter Grosshans and Pantelis Kalaitzidis (eds.) Politics, Society and Culture in Orthodox Theology in a Global Age (Paderborn: Brill, 2023)

33 Kristina Stoeckl, ‘Modernity and Political Theologies’ in Kristina Stoeckl, Ingeborg Gabriel and Aristotle Papanikolaou (eds) Political Theologies in Orthodox Christianity: Common Challenges and Divergent Positions (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2017), p. 17.

34 Vasilios N. Makrides, ‘Political Theology in Orthodox Christian Contexts: Specificities and Particularities in Comparison with Western Latin Christianity’ in Stoeckl et al. Political Theologies, op. cit., p. 26.

35 See Andrew Arato, ‘Political Theology and Populism’, Social Research: An International Quarterly, 80:1 (2013), p. 143.

36 For a classic problematization of the secular-religious binary, see Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003). For a more recent overview of related problems, see Craig J. Calhoun, Mark Juergensmeyer, and Jonathan VanAntwerpen (eds.) Rethinking Secularism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

37 See Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Populism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 6.

38 Kurt Weyland, ‘Populism as a Political Strategy: An Approach’s Enduring – and Increasing – Advantages’. Political Studies, 69:2 (2021), pp. 185–189.

39 Benjamin Moffitt and Simon Tormey, ‘Rethinking Populism: Politics, Mediatisation and Political Style’, Political Studies, 62:2 (2014), pp. 381–397.

40 Rogers Brubaker, ‘Why Populism?’, Theory and Society, 46 (2017), pp. 357–385.

41 Ernesto Laclau, ‘Populism: What’s in a Name?’ in David R. Howarth (ed.) Post-Marxism, Populism, and Critique (Routledge Innovators in Political Theory. London and New York: Routledge, 2015), p. 153.

42 Laclau, Populism, op. cit., p. 163.

43 Ernesto Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005), pp. 72–93.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 For a discourse-ontological account on hegemony and social multiplicity, see Viacheslav Morozov, ‘Uneven Worlds of Hegemony: Towards a Discursive Ontology of Societal Multiplicity’, International Relations, 36:1 (2022), pp. 83–103.

47 Laclau, On Populist Reason, op. cit., pp. 80–82.

48 Laclau, On Populist Reason, op. cit., p. 196.

49 They cite the case of Latin American populism, which ‘predominantly has a socioeconomic dimension (including the poor)’ and the European populism, which ‘has a primarily sociocultural dimension (excluding the “aliens”)’; See Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America’. Government and Opposition, 48:2 (2013), p. 167.

50 Laclau, On Populist Reason, op. cit., p. 163.

51 Think, for instance, of Yugoslavism and Pan-Slavism. See Aleksandar Pavkovic, ‘Yugoslavism: A National Identity That Failed?’ in Leslie Holmes Philomena Murray (eds.) Citizenship and Identity in Europe (London and New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. 147–158 and Vladimir Đorđević, Mikhail Suslov, Marek Čejka, Ondřej Mocek, and Martin Hrabálek, ‘Revisiting Pan-Slavism in the Contemporary Perspective’, Nationalities Papers, 51:1 (2023), pp. 3–13.

52 Benjamin De Cleen and Yannis Stavrakakis, ‘Distinctions and Articulations: A Discourse Theoretical Framework for the Study of Populism and Nationalism’. Javnost: The Public, 24:4 (2017), pp. 301–319.

53 Ibid., p. 311.

54 Ibid., p. 308.

55 Ibid., p. 302.

56 In addition to the internal and external terrains, there could be various intermediary or scalar ones which oscillate between the inner and the outer social spaces or further fragment the latter into narrower levels.

57 See Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, ‘Post-Marxism Without Apologies’. New Left Review, I/166 (1987), pp. 82–84.

58 Morozov, op. cit., p. 84.

59 Thomas Zicman de Barros, ‘Desire and Collective Identities: Decomposing Ernesto Laclau’s Notion of Demand’. Constellations, 28:4 (2021), p. 519.

60 Daniela Kalkandjieva, The Russian Orthodox Church, 1917–1948: From Decline to Resurrection (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), pp. 12–64.

61 Kalkandjieva, op. cit., pp. 94–149.

62 Olga Hoppe-Kondrikova, Josephien van Kessel, and Evert van Der Zweerde, ‘Christian Social Doctrine East and West: The Russian Orthodox Social Concept and the Roman Catholic Compendium Compared’. Religion, State and Society, 41:2 (2013), p. 202.

63 Jane Ellis, ‘The Millennium Celebrations of 1988 in the USSR’ in Jane Ellis (au.) The Russian Orthodox Church: Triumphalism and Defensiveness (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), pp. 27–41.

64 Alexander Ponomariov, The Visible Religion: The Russian Orthodox Church and Her Relations with State and Society in Post-Soviet Canon Law (1992–2015) (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2017), pp. 306–312.

65 Stoeckl, Russian Orthodoxy and Secularism, op. cit., pp. 28–29.

66 ‘Russian Federation Federal Law: ‘On Freedom of Conscience and on Religious Associations’’, Journal of Church and State, 39:4 (1997), pp. 873–889.

67 See Elsner Regina, The Russian Orthodox Church and Modernity: A Historical and Theological Investigation into Eastern Christianity between Unity and Plurality (Stuttgart: ibid Press, 2021), pp. 134–135 and Geraldine Fagan, Believing in Russia – Religious Policy after Communism (London and New York: Routledge, 2013), pp. 69–82.

68 See Dmitry Adamsky, Russian Nuclear Orthodoxy: Religion, Politics, and Strategy (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), pp. 85–98.

69 Irina Papkova, ‘Russian Orthodox Concordat? Church and State under Medvedev’, Nationalities Papers, 39:5 (2011), pp. 667–683.

70 Ibid.

71 See Laruelle, Marlène, ‘Conservatism as the Kremlin’s New Toolkit: An Ideology at the Lowest Cost’, Russian Analytical Digest, 138:8 (2013), pp. 2–4.

72 See Alexander Agadjanian, ‘Tradition, Morality and Community: Elaborating Orthodox Identity in Putin’s Russia’, Religion, State & Society, 45:1 (2017), pp. 39–60.

73 See Mikhail Suslov, ‘‘Holy Rus’: The Geopolitical Imagination in the Contemporary Russian Orthodox Church’, Russian Politics & Law, 52:3 (2014), pp. 67–86 and Alicja Curanović, ‘Russia’s Mission in the World: The Perspective of the Russian Orthodox Church’, Problems of Post-Communism, 66:4 (2019), pp. 253–267.

74 See, ‘Pod predsedatel'stvom Svyateishego Patriarkha Kirilla v Peterburge otkrylos' ocherednoe zasedanie Svyashhennogo Sinoda’ [‘Under the chairmanship of His Holiness Patriarch Kirill, a regular meeting of the Holy Synod opened in St. Petersburg’], Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2013, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/3004213.html (hereafter Kirill 2013).

75 See Hanna Stähle, Russian Church in the Digital Era: Mediatization of Orthodoxy. Religion, Media, and Culture Series (London and New York: Routledge, 2022), pp. 61–82.

76 See Adamsky, op. cit.

77 See Tobias Köllner, ‘Patriotism, Orthodox Religion and Education: Empirical Findings from Contemporary Russia’, Religion, State & Society, 44:4 (2016), pp. 366–386.

78 See Nicolai N. Petro, ‘The Russian Orthodox Church’ in Andrei P. Tsygankov (ed.) Routledge Handbook of Russian Foreign Policy (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), pp. 217–232.

79 Kristina Stoeckl, ‘The Russian Orthodox Church and Neo-Nationalism’ in Florian Höhne and Torsten Meireis (eds.) Religion and Neo-Nationalism in Europe (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2020), pp. 315–317.

80 Kathy Rousselet, ‘The Russian Orthodox Church and the Global World’ in Giuseppe Giordan and Siniša Zrinščak (eds.) Global Eastern Orthodoxy: Politics, Religion, and Human Rights (Cham: Springer, 2020), p. 48.

81 Marlène Laruelle, ‘Commemorating 1917 in Russia: Ambivalent State History Policy and the Church’s Conquest of the History Market’, Europe-Asia Studies, 71:2 (2019), pp. 260–265.

82 ‘Vystuplenie Svyatejshego Patriarkha Kirilla na otkrytii XV Vsemirnogo russkogo narodnogo sobora’ [‘His Holiness Patriarch Kirill speaks at the opening of the XV World Russian People's Council’], Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2011, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/1495312.html (hereafter, Alexy 2011).

83 ‘Deklaratsiya russkoi identichnosti’ [‘Declaration of Russian identity’]’, Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2014, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/508347.html.

84 ‘Statute of the Russian Orthodox Church’, III. 1., The Russian Orthodox Church. Department for External Church Relations, 2017, https://old.mospat.ru/en/documents/ustav/ (hereafter, Statute 2017).

85 In principle, the Local Council (Pomestnyi Sobor), in which, besides the bishops, also priests and laity participate, holds supreme authority in the ROC. However, since the dissolution of the USSR, only one such Council has been convened – in 2009, in order to elect a new Patriarch after Alexy’s demise.

86 ‘Ustav Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi’ [‘Statute of the Russian Orthodox Church’], Drevo. Otkrytaya pravoslavnaya entsiklopediya, 2013, http://drevo-info.ru/articles/23927.html.

87 ‘Ustav ob upravlenii Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi [Charter on the administration of the Russian Orthodox Church]’, III. 3. (z), Drevo. Otkrytaya pravoslavnaya entsiklopediya, 1988, http://drevo-info.ru/articles/17772.html.

88 Statute 2017, op. cit., III. 2. Before 2013, the Statute stipulated a more limited participation of the vicar bishops, providing only some of them with voting rights. See Ustav 1988, op. cit., III. 1. and Ustav 2000, III.1., ‘Ustav Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi [Statute of the Russian Orthodox Church]’, Drevo. Otkrytaya pravoslavnaya entsiklopediya, 2000, http://drevo-info.ru/articles/17774.html.

89 According to the ROC’s Statute, its jurisdictions extends to all the former Soviet republics except Armenia and Georgia, as well as to China, Japan, Mongolia, ‘and also to the Orthodox Christians living in other countries and voluntarily joining this jurisdiction’. See Statute 2017, op. cit., I. 3.

90 Statute 2017, op. cit., III. 3.

91 Ibid., III. 12.

92 Ibid., III. 13.

93 Ibid., III. 16.

94 See ‘Basis of the Social Concept of the Russian Orthodox Church’, II. 3., The Russian Orthodox Church. Department for External Church Relations, 2000, https://old.mospat.ru/en/documents/social-concepts/ (hereafter Basis) and ‘Osnovy ucheniya Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi o dostoinstve, svobode i pravakh cheloveka [Basic Teaching on Human Dignity, Freedom, and Rights]’, III. 4., Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2008, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/428616.html (hereafter, Osnovy 2008).

95 I used the Patriarchate’s original English translation to facilitate wider replicability and the original Russian text to elucidate the exact use of certain terms and expressions. See Basis, op. cit. and ‘Osnovy sotsial'noi kontseptsii Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi [The Basis of the Social Concept of the Russian Orthodox Church]’, Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2000, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/419128.html.

96 See Basis, op. cit., II. 1. and ‘Basic Principles of the Attitude of the Russian Orthodox Church toward the Other Christian Confessions’, 1. 3., Department for External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate, 2000, http://orthodoxeurope.org/page/7/5/1.aspx.

97 Basis, op. cit., II. 2.

98 Ibid., II. 1.

99 The terms narod and natsiya are used interchangeably in Council documents.

100 See Basis, op. cit., II. 2.

101 Ibid., II. 3.

102 Ibid.

103 Ibid.

104 Freedom to as opposed to freedom from, or ‘negative liberty’ in Isaiah Berlin’s terms. See Isaiah Berlin, ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’ in David Miller (ed.) Liberty Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 33–57.

105 ‘Doklad Patriarkha Moskovskogo i vseya Rusi Aleksiya II na Arkhiereiskom Sobore Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi 3 oktyabrya 2004 goda’ [‘Report of Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow and All Russia at the Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church on 3 October 2004’, Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2004, http://sobor.patriarchia.ru/db/text/420130.html (hereafter, Alexy 2004).

106 For the overlaps and differences between these fluid concepts, see Suslov, Holy Rus’, op. cit.

107 A homology in itself, since the construction ‘the peoples of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus’ totalises the ethnic and the civic dimensions.

108 Alexy 2004, op. cit.

109 ‘Doklad Patriarkha Moskovskogo i vseya Rusi Aleksiya II na Arkhiereiskom Sobore Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi’ [‘Report of Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow and All Russia at the Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church’], Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2008, http://sobor.patriarchia.ru/db/text/426666.html (hereafter, Alexy 2008).

110 ‘Postanovleniya osvyashhennogo Arkhiereiskogo Sobora Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi’ [‘Resolutions of the Holy Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church’], 33, Ofitsial’nyi sait Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, 2013, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/2777929.html (hereafter, Postanovleniya 2013).

111 For an analysis of the effects of such articulations in Ukraine, see Catherine Wanner, ‘“Fraternal” Nations and Challenges to Sovereignty in Ukraine: The Politics of Linguistic and Religious Ties’, American Ethnologist, 41:3 (2014), pp. 427–439.