Article title: How peers’ informedness contributes to students’ person-environment fit

Authors: Stefanie, P., Victoria, Z., & Simone, K.

Journal: European Journal of Higher Education

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2022.2049837

Author has substituted the following text under “Informedness”

Students responded to the following question: “From your current perspective, to what extent did you have sufficient information on the following aspects before starting your studies…?” for example, regarding study conditions and study requirements using a six-point Likert scale (1 = “insufficient” to 6 = “completely sufficient”).

To

Students responded to the following question: “From your current perspective, to what extent did you have sufficient information on the following aspects before starting your studies … ?” for example, regarding study conditions and study requirements and an additional item regarding vocational perspectives using a six-point Likert scale (1 = “insufficient” to 6 = “completely sufficient”).

The author has corrected or included new text to the following sections of the article:

Author has included two new sentences at the end of the section “Statistical analysis” as follows “Independent and moderator variables were mean-centered. Templates in Excel (Dawson 2022) were used to visualise both two-way interactions.”

Author has also included the new reference Dawson 2022:

Dawson, J. 2022. “Interpreting Interaction effects.” Accessed March 21. http://www.jeremydawson.co.uk/slopes.htm.

Author has corrected few sentences under “Test of moderation (H1)” as follows:

“Appendices 1 and 2” to “Appendices 1 and 2 (available in the Online Supplementary Materials).”

Author has substituted the following text under “Test of moderation (H1)”

The results also showed that the positive effect of the proportion of informed peers on the relationship between students’ informedness on their N-S fit was stronger for those with a lower (one SD below the mean) informedness (effect = 0.632, se = .132, 95%CI = [0.373, 0.892]) than for students with an average (mean) informedness (effect = 0.406, se = .081, 95%CI = [0.247, 0.565]). For highly informed students (one SD above the mean) (effect = 0.180, se = .101, 95%CI = [−0.017, 0.376]), the effect was not significant (see figure 2). For D-A fit, the positive effect of a higher proportion of informed peers was stronger for students with a lower informedness (effect = 0.548, se = .137, 95%CI = [0.281, 0.816]) than for students with an average informedness (effect = 0.385, se = .087, 95%CI = [0.214, 0.556]) (see figure 3). In contrast, the effect for highly informed students was stronger for those with a lower proportion of informed peers (effect = 0.222, se = .097, 95%CI = [0.032, 0.411]).

To

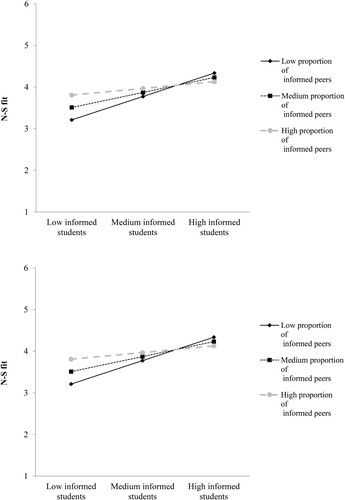

The results also showed that for students with a low proportion of informed peers (one SD below the mean) the positive relationship between their informedness on their N-S fit was stronger (effect = 0.632, se = .132, 95%CI = [0.373, 0.892]) than for students with an average (mean) proportion of informed peers (effect = 0.406, se = .081, 95%CI = [0.247, 0.565]). For a high proportion of informed peers (one SD above the mean), the relationship between students’ informedness and their N-S fit was non-significant (effect = 0.180, se = .101, 95%CI = [−0.017, 0.376]) (see figure 2).

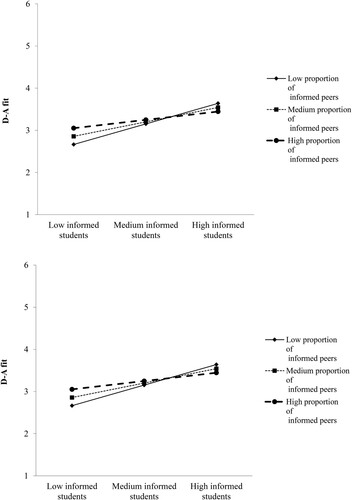

For D-A fit (see figure 3), the positive effect of a higher informedness was stronger for students with a low proportion of informend peers (effect = 0.548, se = .137, 95%CI = [0.281, 0.816]) than for students with an average (effect = 0.385, se = .087, 95%CI = [0.214, 0.556]) or high proportion of informed peers while a high proportion of informed peers reduces the effect of students’ informedness on their D-A fit (effect = 0.222, se = .097, 95%CI = [0.032, 0.411]).

Author has substituted few sentences under “Discussion” section as follows:

Furthermore, for students who perceived themselves to be less informed at the beginning of their studies, we found that higher proportions of informed peers in their network were advantageous for their D-A and N-S fit. This effect was especially strong for students who reported low informedness compared to those who reported average informedness, for whom this effect was rather small. In contrast, for highly informed students, a low proportion of informed peers in their network was advantageous for their D-A fit, and while the effect on their N-S fit was not significant, the results indicated a similar relationship. Thus, for highly informed students with higher proportions of informed peers in their network, our results suggested a link to a lower P-E fit perception compared to highly informed students with lower proportions of informed peers. This suggests that peer networks comprised of students with differing levels of informedness, high and low, might be particularly beneficial for both groups. Less-informed students might profit from access to information that helps them transition more easily into higher education. On the other hand, well-informed students might benefit from sharing their knowledge because it allows them to reflect on what they know and uncover areas of ignorance, enabling them to proactively and efficiently close their knowledge gaps. Meanwhile, the decrease in fit perception in well-informed students who have a higher proportion of informed peers in their networks might be attributed to negative social comparisons (e.g. De Vries and Kühne 2015). A large proportion of equally or better-informed peers might increase social comparisons, possibly leading to a decreased self-evaluation and a lower P-E fit perception. This would not be the case for well-informed students with networks that predominantly comprise less-informed peers. Once established as an expert, these students are more likely to be sought out for information and advice, in turn increasing the likelihood to encounter new information.

To

This positive effect was moderated by the proportion of informed peers embedded in students’ peer networks. Specifically, it was stronger for students who reported a low proportion of informed peers compared to those who reported an average or high proportion of informed peers embedded in their peer network. For D-A fit, a high proportion of informed peers even weakens the positive effect of students’ informedness, meaning that in the presence of a well-informed peer network, students’ fit perception is no longer linked as strongly to their own informedness. In the presence of a high proportion of informed peers, the effect of students’ informedness on their N-S fit is even non-significant. Furthermore, for students who perceived themselves to be less informed at the beginning of their studies, our results suggest that higher proportions of informed peers in their network were advantageous for their fit perceptions. As we did not test for these differences, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

The results suggest that peer networks comprised of peers with higher levels of informedness than ego might serve as a valuable resource to level the effect of ego’s informedness on their fit perception. This means that for less-informed students, peers’ informedness could serve to compensate for students’ lack of informedness. On the other hand, for students with a low proportion of informed peers in their network, the results highlight the importance of the effect of students’ informedness on their P-E fit. Thus, less-informed students might profit from access to information (e.g. well-informed peers) that helps them transition more easily into higher education without having to rely solely on their informedness.

Author has substituted and included the sentences under “Theoretical and practical implications”

Author has substituted the sentence as follows:

Additionally, we found the composition of students’ peer networks to significantly influence students’ D-A and N-S fit, depending on students’ informedness before starting their studies. Specifically, a higher proportion of equally-well or better-informed peers in a network positively affects students’ P-E fit for those who started studying low or averagely informed. For highly-informed students, we did not find this relationship. In contrast, our results showed a reversed relationship, such that a lower proportion of equally-well or better-informed peers in their network is more beneficial for their P-E fit.

To

Additionally, we found the composition of students’ peer networks to significantly moderate the effect of students’ informedness before starting their studies on their D-A and N-S fit. Specifically, the positive relationship between students’ informedness and their P-E fit is stronger for students with a lower proportion of informed peers in their network compared to average proportions of informed peers. For high proportions of informed peers, the relationship between their informedness and their D-A fit was weaker and non-significant for N-S fit.

Author has included a new paragraph at the end of the first paragraph under Theoretical and practical implications’:

In line with social capital perspectives on social networks (Lin, 1999), peer networks could serve as a viable resource compensating for a lack of students’ informedness going into their studies.

Author has substituted the sentence as follows:

Additionally, our study has shown that access to study-relevant information through peer networks is important for students in higher education.

To

Additionally, our study has shown that access to study-relevant information through peer networks is important for students in higher education, even serving as a potential alternative to students’ informedness to the extent that a high proportion of informed peers weakens the relationship between students’ informedness and P-E fit perception within our sample.

Author has substituted the sentence as follows:

In addition to the programmes to increase informedness for all first-year students (e.g. orientation weeks), our results show that peers can be an important source of information, especially in networks that include mixed levels of informedness. Accordingly, staff should also encourage students to form such networks through, for example, group activities in which less- and well-informed students are intentionally mixed and then given tasks that cover the basic information needed to navigate the early semesters.

To

In addition to the programmes to increase informedness for all first-year students (e.g. orientation weeks), our results suggest that, especially with regard to low-informed students, peers can be an important source of information. Accordingly, staff should also encourage low-informed students to connect with informed peers through, for example, group activities in which less- and well-informed students are intentionally mixed and then given tasks that cover the basic information needed to navigate the early semesters.

Author has substituted few sentences under ‘Conclusion’ section as follows:

We found that the P-E-fit of students with low and average informedness benefits from more informed peers in their networks. In contrast, the P-E-fit of well-informed students benefits from fewer informed peers.

To

Furthermore, findings indicate that the P-E fit of low-informed students might benefit from a higher proportion of informed peers in their networks.

Author requested to remove the below reference from the reference list:

De Vries, D. A., and R. Kühne. 2015. ‘Facebook and Self-Perception: Individual Susceptibility to Negative Social Comparison on Facebook.’ Personality and Individual Differences 86: 217–221. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.029.

Author has corrected Figures 2 and 3. Corrected Figures are included below: