ABSTRACT

Intercultural competence is an increasingly desirable life skill in a multicultural and globalized world. To promote this learning outcome, higher education institutions can offer internationalization activities both at home and abroad. Research investigating to what extent ‘Internationalization at home’ (IaH) initiatives, as opposed to study abroad, affect the development of intercultural competence (IC) in students, especially in universities where the home student population is still mainly white, like at the university in focus in this paper, is scarce. This survey study aimed to gain insights into the intercultural competence of 506 Flemish university students, and the factors predominantly positively affecting IC development. Our findings reveal that study abroad, participation in cocurricular IaH initiatives, foreign language mastery and use, and the personality traits agreeableness and openness have a bearing on IC and feature among the main explanatory factors. Overall, the findings suggest that the 60,000 student European research university in focus appears successful at having created a study environment that is truly international and can contribute to IC development over the years of study. Via the integration of international and intercultural dimensions into the formal and informal curriculum for all students within domestic learning environments, it contributes to developing international and intercultural mindsets in students.

Introduction

Over the past decades, universities have invested quite some energy in establishing themselves as ‘truly international’ institutions, establishing international offices, and entering into selected international study and research agreements. Whereas it was hoped that large numbers of students and staff would spend part of their study and research careers abroad, it is now clear that more modest expectations need to be set, and that other home-based initiatives are needed to promote intercultural competence among students and members of staff.

Over the last 15 years, universities have started to deploy also internationalization initiatives at home (IaH). As Jane Knight points out, ‘a significant development in the conceptualisation of internationalization has been the introduction of the term[s] “internationalization at home”’ (Knight Citation2013, 85). Internationalization at Home (IaH) initiatives include the interculturalisation of the curriculum, English-medium degree programs, online exchange projects, or service-learning in cooperation with organizations that cater to the disadvantaged and underprivileged in society, such as people with refugee or migrant backgrounds.

Conclusive evidence regarding the extent to which Internationalization at home initiatives affect the development of intercultural competence (IC) in students, especially at universities where the student population is still mainly white, like at the university in focus in this paper, is very scarce. This should not surprise given the challenges involved in researching on the one hand the effect of IaH initiatives on learning and on the other hand intercultural competence. Whereas IC has been defined in many different ways and a plethora of theoretical models and assessment instruments are available (Sercu Citation2004; Griffith et al. Citation2016), IaH initiatives as a construct has appeared more recently and has not yet been contoured or operationalized well.

The survey study presented here aimed to gain insights into the degree to which students studying at Belgium’s largest mainly Dutch-medium university during the academic year 2018–2019 develop intercultural competence during their course of study at university, which variables impact their IC scores and which of the identified factors matter most. Thus, we investigated whether IaH activities can be considered a valuable alternative to study abroad (SA) as far as the development of IC in students is concerned. We will argue that the Belgian context is such that young people have manifold opportunities for IC learning also at home, and that previous research on the benefits of SA (for example, Soria and Troisi Citation2014) now needs to be complemented with new research investigating IC learning at home in countries that offer citizens ample opportunities for international and intercultural contacts from a very early age onwards, such as Belgium. The results of this study, investigating the home-based students as stakeholders, are expected to provide insights in the factors contributing most to their IC within a highly multilingual and multicultural university environment and repositioning SA as a contributing factor.

Context

The study uses survey data collected from 506 students studying at KU Leuven (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven). Like other European universities, KU Leuven, the largest Dutch-medium Belgian university, has participated in the academic internationalization process. In the academic year 2020–2021, the university received 11,312 foreign students from over 150 different countries from around the globe. This group of students constitutes 18% of KU Leuven’s total number of registered students, which in 2020–2021 amounted to 62,652. Of the 11,312 international students, 3616 studied to obtain a PhD degree and 5665 an English-medium Master’s degree. KU Leuven received 1144 students on short-term Erasmus scholarships (+/− four months). Some 2% or 1487 of Belgian Bachelor’s or Master’s students spent one semester at a foreign European university.

From these numbers, it appears that international students in Leuven by far outnumber the outbound SA students, and that the outbound Erasmus programme has failed to attract large numbers of students as was hoped when it was first launched (Brooks and Waters Citation2009). The numbers also imply that 50,000 Bachelor’s and Master’s students study at a mainly white campus, even if about 15% of freshmen students have an immigrant background and 2912 of 12,706 members of staff, or 23%, are of foreign origin.

Within this mainly white Bachelor’s and Master’s study environment, it is challenging to further enhance all students’ intercultural competence. Whereas previously, IC development at home was taken for granted, in recent years KU Leuven has started to deploy explicitly IaH activities. These activities aim to promote intercultural interactions between students of diverse origins. They include for example a buddy project in which a Belgian student coaches an international student, service-learning projects in which students do an internship in an organization that serves immigrant or other underprivileged societal groups, or intercultural contact activities organized by and in the international student community centre. Furthermore, an international research environment is present, English-medium programmes are offered that attract foreign lecturers and students, and many lecturers provide students with international perspectives on their field of studies, for example through using foreign language-medium course materials or organizing intercultural discussion groups. Additionally, all students have the benefit of easy access to broadband Internet and other (international) social media, have been at secondary schools with mixed populations, have visited diverse countries during their secondary education as part of their curriculum, and have been studying two or three foreign languages for a number of years before entering universities.

Research questions

Investigating students’ learning within the KU Leuven intercultural and international context, the study addressed the following research questions:

Is a development in IC noticeable over the years of university education?

Do students from all faculties develop IC to the same degree?

To what extent do students participate in IaH activities?

Do students who participate less in IaH activities show lower levels of IC?

What other factors apart from IaH participation have a bearing on students’ IC?

Conceptual framework

As universities begin to explore expanding traditional models of learning outcomes, and emphasize also life skills (Griffith et al. Citation2016, 36), there is a need to define each life skill and find adequate ways to assess to what extent students possess them. In the following sections, we relate how the concept of intercultural competence has been defined in educational contexts. We do so through presenting one commonly referred to dynamic process model (Deardorff Citation2006), and explain how this model is useful to our research. Next, we discuss which factors have been shown to potentially affect growth of intercultural competence, including the factors SA and IaH.

Intercultural competence as a dynamic process

Attempts to define and categorize intercultural competence have been varied and longstanding (Byram Citation1997; Council of Europe Citation2018; Deardorff Citation2006; Fantini Citation2020). All models share the idea of the development of intercultural intelligence in a process of socialization into a different culture. Becoming part of a new cultural group leads to the development of the ability to communicate effectively and adequately in intercultural situations on the basis of one’s increasing intercultural knowledge, skills and attitudes.

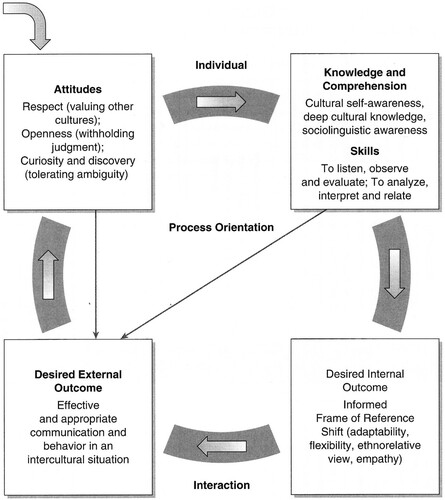

Deardorff’s Citation2006 Process model of IC, shown in , captures this socialization process very well. It emphasizes that individuals develop IC in communication and interaction with others, and that development happens with respect to four dimensions: attitudes, knowledge, internal frame of reference and behaviour. Prerequisites to a person’s willingness and ability to enter intercultural dialogic situations are attitudes, such as openness and curiosity, but also skills that allow one to comfortably relate to people of other cultural backgrounds. When contact with foreignness, for example, through study abroad or internationalization at Home activities, enhances one’s cultural self-awareness, a shift in one’s internal frame of reference can happen, from a monocultural one to a multicultural, ethnorelative or supracultural one. As an intercultural person, one understands that all humans share a number of universal values, but that the manifestation of these values may be culturally defined (Kim Citation2015).

Figure 1. Process Model of Intercultural Competence (Deardorff Citation2006, Citation2009). Used by permission.

As suggested by Deardorff’s model, the development of IC can be understood as a dynamic recurrent process that relies heavily on intensive meaningful contacts that can entice the individual to reconsider his/her worldview. Because of changes in one’s mindset, one may be more willing to interact with otherness, participate in international cooperation, consider local and global issues, and take action for collective well-being and sustainable development.

Factors affecting IC development

(see Appendix 1) provides an overview of the variables we identified in the literature as potentially impacting IC development. This framework served as the basis for designing our research instrument and guided the analysis of our data.

Table 1. Conceptual framework: factors potentially affecting IC.

Table 2. Regression analysis: Model Summary.

Table 3. Regression analysis: ANOVA results.

Table 4. Regression analysis: Variable coefficients.

Table 5. Revised conceptual framework: Factors explaining variance in IC.

Deardorff (Citation2006) as well as other models of IC development emphasize the importance of ‘meaningful contacts’ as triggers for IC development. As far as the factor ‘Internationalization at Home’ is concerned, it appears that the available research is very scarce in comparison to research studying other potential factors affecting IC. When such research is available, it is inconclusive as to whether IaH initiatives are successful and actually do multiply home students’ intercultural learning experiences and/or enhance their IC. For example, Harisson in his review study of literature on IaH at Anglosaxon Higher Education Institutions, writes that ‘recent research (…) constructs home students as being differentially predisposed towards seeking and making the most of intercultural experiences.’ (Citation2015, 418). Furthermore, ‘the evidence to date suggests that this [IaH] is considerably more problematic than might be imagined.’ (Harrison Citation2015, 412). English native students studying at English-medium universities fear that their grades will go down when they have to cooperate with an international student or a student with an immigrant background who is presumed not to be as strong a student as they are.

Other scholars have focused on studying the impact on IC development of IaH as opposed to SA. Interestingly, researchers, such as Soria and Troisi (Citation2014) conclude that IaH efforts ‘can be valuable in promoting students’ development of intercultural competencies’ (276) and further state that their study suggests that internationalization at Home activities can enhance students’ IC ‘just as effectively as – if not more effectively than – formal study abroad.’ (274).

From the review of the literature, it has become clear that, apart from SA and IaH, some other factors that supposedly have a bearing on people’s IC have been studied more frequently than others. They include bi- or multilingualism (Yu, Vyas, and Wright Citation2020), gender (Tompkins et al. Citation2017), or frequency and length of contact with other cultures (e.g. Li, Mobley, and Kelly Citation2016; Fozdar and Volet Citation2016). These studies have shown that multilingualism and length of contact are important moderators of intercultural competence, as is gender, with women overall exhibiting higher degrees of intercultural competence than men.

Others have studied personal characteristics, such as moral sensitivity (Kaya et al. Citation2021) or the Big five personality characteristics (e.g. Ang, Van Dyne, and Koh Citation2006; Harrison Citation2012). Substantial work on the interaction between people’s personality and their IC has shown frequently that a larger degree of openness, agreeableness, and lower degrees of neuroticism or conscientiousness correlate positively with IC (see, for example, Ang, Van Dyne, and Koh Citation2006; Li, Mobley, and Kelly Citation2016).

Finally, fewer studies have researched interactions between different factors, such as, for example, Alfonzo-de-Tovar, Cáceres Lorenzo, and Santana-Alvarado (Citation2017) who researched interactions between age, gender, mother tongue, degree of multilingualism, but also the power of factors such as mobility, academic level, and field of study. The results obtained allowed the authors to specify different IC profiles and the factors that directly affect how students are classified. Among others, it was found that multilingualism has a clear influence on IC, to a greater extent than age, gender, or academic field of study.

The study

Sample

The recruitment of students took place within the confines of a larger mixed-methods study in which students’ intercultural profiles were mapped (Eren and Sercu Citation2019). Students from all study phases were invited via student circles’ facebook pages to participate in the online survey. Data collection was done during three weeks in April 2019. In total, 506 students (344 BA students, 150 MA students and 12 Postgraduate students) completed the questionnaire. 22.7% of them had a migration background, a percentage that surmounts the percentage of students with a migration background studying at KU Leuven (11.9%). Three hundred and five (335) women (66.2%) and 171 (33.8%) men responded to all questions, which means that female students were overrepresented in the sample since on average 52.4% of KU Leuven’s students are male and 47.6% female. All 14 KU Leuven faculties are represented in the sample, including students from the faculties of Movement and Rehabilitation Sciences, Industrial Engineering Sciences, Psychology and Educational Sciences, Bioengineering, Economics and Business Sciences, Pharmaceutical Sciences, Medicine, Engineering, Arts, Law, Social Sciences, Theology and Religious Sciences, Sciences, and Philosophy. In the sample, the faculties of Medicine and Economics and Business Sciences are underrepresented in comparison to the average proportion of KU Leuven students these faculties attract. The difference amounts to 8.2% for Medicine (6.7% of the sample versus 14.9% of KU Leuven students) and 7.5% for the faculty of Economics and Business Sciences (2.8% of the sample versus 11.3% of KU Leuven students). On the contrary, the faculties of Engineering (18.8% of the sample versus 9.9% of KU Leuven students) and Arts (18% of the sample versus 7.4% of KU Leuven students) are overrepresented. Yet, when clustering these data into Faculty groups, it appears that the proportion of students studying Human Sciences at KU Leuven matches the proportion of these students in the sample. Students studying Biomedical Sciences are somewhat underrepresented and students in Engineering Sciences, Sciences and Technology slightly overrepresented.

Survey instrument

To collect the data, a survey instrument was designed to investigate students’ intercultural competence after the conceptual model presented in Table 1. A quantitative study was used to study relationships between variables and investigate whether the variance in the dependent variable ‘intercultural competence’ could be explained by the independent variables included in this study, and in particular SA and IaH (see Table 1 in Appendix 1), obtaining data from a substantial group of respondents. The demographic data include gender, age, place of birth, nationality, the region where you spent your youth, faculty, year of study, degree of father, degree of mother, and immigrant background. Language learning data included the number of languages learned, the frequency of their use, and the level of mastery of each language. Contact data inquired into the number and duration of stays abroad, type of contacts abroad (e.g. friend versus distant stranger), and contacts with immigrants at home. Also, a personality profile was composed using questions from the Big Five Inventory (Rammstedt, Kemper, and Borg Citation2013). IC was mapped by means of 25 statements which the respondents had to score on a five-point Likert scale (completely agree – not agree at all). The statements were chosen to represent the different dimensions of Deardorff’s definition of IC, namely Knowledge and comprehension, Desired Internal Outcome, Desired External Outcome and Attitudes. The statements were inspired by or taken from existing instruments to assess intercultural competence, namely The Global Mindedness Scale (Hett Citation1993), the Cultural Intelligence Scale (Ang et al. Citation2007), the Assessment for Intercultural Competence (Fantini and Tirmizi Citation2006) and the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity Instrument (Hammer, Bennett, and Wiseman Citation2003). The internal consistency of the newly composed scale amounted to Cronbach’s alpha = 0.875. Example statements included I know the rules for expressing nonverbal behaviours in other cultures (knowledge dimension of Deardorff’s model). I think of myself, not only as a citizen of my country but also as a citizen of the world (desired internal outcome dimension). I adapt my behaviour to communicate appropriately in a foreign country (e.g. in non-verbal and other behavioural areas, as needed for different situations) (desired external behaviour dimension). I enjoy living in cultures that are unfamiliar to me (attitudes dimension). Finally, the students’ Internationalization at Home profile was composed on the basis of questions inquiring into their familiarity with IaH initiatives, their active participation in these activities, and their enjoyment of these activities. Example questions included I generally find it stimulating to spend an evening talking with people from other cultures. I am familiar with Pangaea, the international students’ community centre. I take part in intercultural learning activities. I am involved in service-learning with underprivileged groups. Again, these questions had to be scored on a scale registering the students’ self-perceived level of familiarity or degree of participation.

Data analysis involved the composition of a number of aggregated scores: an IC-score, IaH-score, extraversion score, agreeableness score, conscientiousness score, neuroticism score, and openness score (cf. the Big Five Personality Traits), and scores for language mastery. The other variables used in further data processing were non-aggregated variables. Using IBM SPSS 28.0, T-tests, ANOVA tests, and linear regression analyses were used to analyze the data.

Results

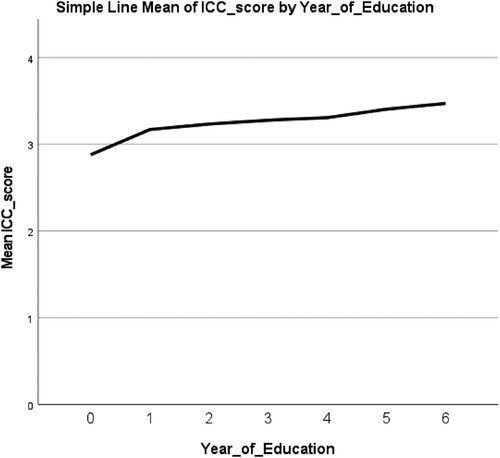

Is development in IC noticeable over the years of university education?

As can be seen from Graph 1, per year of study, students’ IC scores appear to rise, with, notably, a steep increase during the first year of academic studies, with the starting level determined on the basis of a group (n = 30) of final year secondary school students who also volunteered to participate in the study. More moderate yet steady developments are observable during the three consecutive years of undergraduate education. Overall the students’ scores develop from M = 3.52 out of 5 (mean value for year 1 students) to M = 3.71 (mean value for year 4 students), and then again from M = 3.89 (mean value for year 5 students) to M = 4.03 (mean value for year 6 students). All differences between the years are significant (p < 001). Together, these findings show that a development in IC is noticeable over the years of university education. These findings suggest that students become more interculturally competent just by maturing and moving on in their curriculum. As our data shows, over the years of study, their mindset enlarges and comes to include an awareness that they are not only citizens of their country and Europe, but also of the world. Also, they become more agile at adapting their communicative behaviour to the specific situation they find themselves in.

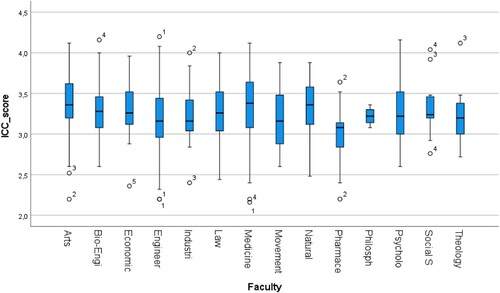

Do students from all faculties develop IC to the same extent?

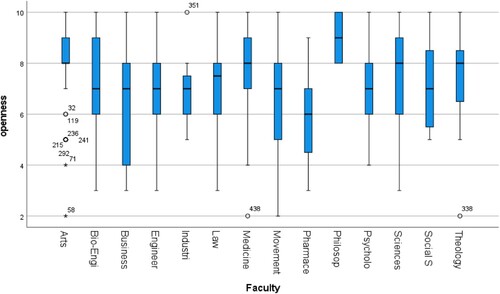

From Graph 2, it can be seen that the levels of IC achieved may differ between faculties. The Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, as the sole faculty, shows a mean value for IC below 3.00, (M = 2.98). The Faculty of Arts shows the highest mean (M = 3.35), followed by the Faculties of Social Sciences (M = 3.34), Natural Sciences (M = 3.33), Bio-Engineering and Medicine (M = 3.31), and Psychology and Pedagogical Sciences (M = 3.30). All other Faculties show mean scores below 3.30: Economical Sciences & Business (M = 3.29), Law (M = 3.25), Industrial Sciences (M = 3.24), Theology and Religious Sciences and Philosophy (M = 3.22), Engineering Sciences and Movement and Rehabilitation Sciences (M = 3.18).

Together, these results show differences between faculties as far as intercultural competence is concerned. Whereas one might have expected that faculties that are part of the Human Sciences study domain would have scored high, this is not the case for the Faculties of Theology and Religious Studies, the Faculty of Law, and the Faculty of Economic Sciences & Business. The high score for the Faculty of Arts is not surprising, given that many students there study foreign languages and cultures. Likewise, in the Faculties of Social Sciences or Psychology and Pedagogical Sciences, in the curriculum attention is given to society’s intercultural composition which may raise these students’ awareness of intercultural issues and affect their attitudes and behaviours. Given that the Faculties of Natural Sciences, Bio-Engineering, and Medicine host quite a number of foreign students, the students from these faculties’ openness towards foreignness is not unexpected.

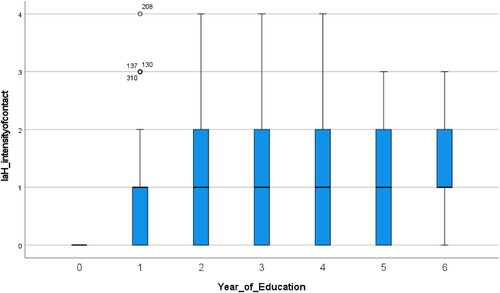

To what extent do students participate in IaH activities?

The intensity of a student’s intercultural contacts is a composite score constructed on the basis of students’ answers to the questions of whether the student often gets into contact with other cultures in Belgium/Flanders; whether that contact occurs during volunteer activities (because that kind of contact may indicate the student’s intrinsic motivation and desire to seek out intercultural contacts), and whether the student has visited the foreign student community centre and/or participated in the university buddy programme of a foreign student. The higher the score, the more intensive the contact of the student.

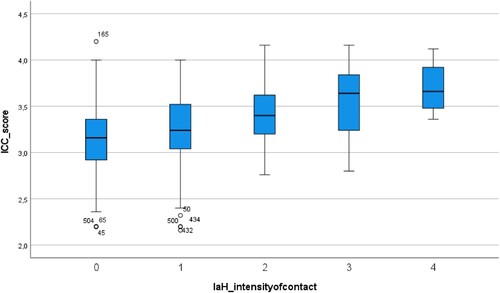

When looking into participation in Internationalization at Home initiatives over the course of students’ academic studies, Graph 3 shows that the mean IaH-index values increase slightly over the years of study. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare IaH-index values between years of study, and revealed that the differences between years of study are significant (F(6.498) = 3.181, p = 005).

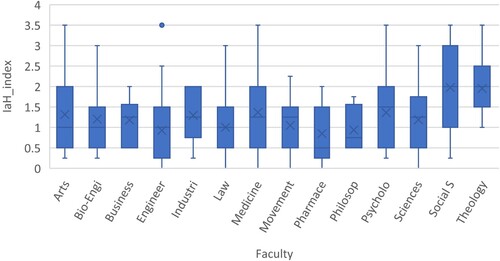

Again, differences between the different faculties are notable (see Graph 4), with the students from the faculties of Medicine (M = 1.37, SD = 0.16), Arts (M = 1.32, SD = 0.09), Psychology and Pedagogical Sciences (M = 1.36, SD = 0.12) and Social Sciences (M = 1.98), SD = 0.31) being those who participate most frequently in IaH initiatives, either because they visit the international students’ centre more frequently or participate more often than other students in the university’s buddy or service learning programs. Students from Pharmaceutical Sciences participate least in any of these programs (M = 0.85, SD = 0.18).

The fact that students’ participation in IaH initiatives increases over the years of study, comes somewhat unexpectedly. The finding may suggest that the more mature students are, the more they are willing to participate in IaH initiatives. They may also suggest that at the Master’s level of education, more international students are present in courses which almost automatically leads to an increase of international contacts in the upper years of education.

The findings regarding the differences between Faculties match those mentioned earlier on regarding students’ development of IC. Students from faculties that prepare students for the local Flemish labour market, such as the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, seem to look for international contacts least often.

Do students who participate less in IaH activities show lower levels of IC?

As can be seen from Graph 5, with more intensive participation in Internationalization at Home activities come increases in IC scores. A one-way ANOVA revealed that there was a statistically significant difference in mean IC scores between at least two different intensity of contact groups (F(4, 501) = 17.2, p < 0.001). A post-hoc Tukey’s test showed that in particular with respect to levels 2 and 3 of intensity of contact, significant differences are noticeable, but not between levels 3 and 4 or 0 or 1. The findings indicate that the IC scores of students who say they quite often have IaH contacts differ significantly from those who indicate they merely sometimes have such contacts. This is a fortunate finding, suggesting that the university’s investments in IaH initiatives pay off. Unfortunately, no more than 115 out of 506 (23%) students indicate they sometimes or quite often engage in intercultural contacts, which suggests that KU Leuven has not been successful enough in enticing all students to participate in IaH initiatives.

What other factors apart from IaH contacts have a bearing on students’ IC

As can be seen from the results of a linear regression analysis, shown in , and (see Appendix 1) into which all investigated factors from the conceptual framework were entered, the following factors together are able to explain 34.2% of the variance in IC score (R2 = 0.342, F(11.493) = 24.8, p ≤ 001): the personality traits openness, agreeableness and extraversion; the intensity of IaH contacts; SA; year of education; and language mastery and frequency of use. Gender (p = 0.168), number of languages (p = 0.687), conscientiousness (p = 0.181) and emotional stability (p = 0.88) appeared not to impact significantly on IC. In other words, not all factors that could theoretically affect IC development (see Table 1) have appeared to actually do so in our study. In particular, it appears that personal factors, such as gender, immigrant background, or socioeconomic status, have to be omitted from the theoretical framework drawn up to predict variance in IC development within the context of IaH. Put differently, students with lower socioeconomic backgrounds have equal chances of developing IC at the tertiary education level.

When looking somewhat deeper into the factors that have the most important bearing on intercultural competence, as regards the mastery and frequency of use of foreign languages, most students indicate they master at least one foreign language and sometimes several foreign languages well and that this pattern is maintained over the years of study. The language mastered well and used frequently from year 1 onwards most often is English, followed by French. The mastery of the English language improves over the years of study as students are expected to study English-medium course materials, especially from the 3rd third year of their Bachelor’s education onwards. The mastery of the second foreign language, French, typically decreases over the years of study, in favour of English. Students who master more than 2 foreign languages maintain this mastery over their years of study. These students may typically be students of Languages and Literature or Languages and Region Studies, but also other student groups from Human Sciences, such as students from the faculties of Economical Sciences & Business, Social Sciences, or Philosophy.

When exploring further the personality characteristics that have been identified in previous studies as affecting IC, our data too reveal that students who are more open than others, more extravert and more agreeable appear to be more interculturally competent. This finding is corroborated by the results of a Pearson correlation analysis that shows that openness (r = .220, p < 001), extraversion (r = .193, p < 001) and agreeableness (r = .279, p < .001) correlate significantly with IC.

Below the results for the main impacting personality trait, namely openness, are elaborated somewhat further. As Graph 6 reveals, students from the Faculties of Philosophy, Arts, and Medicine show the highest scores for openness (M = 9.08, 8.04 and 7.41 out of 10), and students from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Movement and Rehabilitation Sciences the lowest (M = 5.83 and 6.62 out of 10). These findings again match findings regarding these two faculties provided supra and relating to these faculties’ comparatively lower IaH and IC scores.

When investigating an additional factor that has often been suggested to have a bearing on IC, namely gender, an independent T-test did show that males and females in our sample show significant differences in the way in which they self-assess their level of extraversion (females: M = 7.07, SD = 1.66; males: M = 6.67, SD = 1.69), t(504) = 2.960, p = 002); and agreeableness (females: M = 6.82, SD = 1.442; males: M = 6.50, SD = 1.52), (t(504) = 2.365, p = 006). They also differ with respect to scores for intercultural competence (females: M = 3.72, SD = 0.59; males: M = 3.55, SD = 0.58), (t(504) = 2.960, p = 002). These findings corroborate earlier findings (see, for example, Alfonzo-de-Tovar, Cáceres Lorenzo, and Santana-Alvarado Citation2017). Yet, it is interesting to remark that female and male students do not appear to differ significantly from one another as far as their scores for openness are concerned (females: M = 7.33, SD = 1.762; males: M = 7.15, SD = 1.82) (t(504), p = 131). As pointed out by Deardorff (Citation2006), openness is one of the attitudes said to be essential for IC growth. From the fact that males and females do not differ in this respect, it follows that both groups have equal chances of becoming more interculturally competent over the course of their university studies.

Revised explanatory model: theoretical contribution

On the basis of our investigation, Table 5 could be drawn up that summarizes the factors that appear to have an important impact on IC development among the university students included in our sample. It is obvious that Table 5 (see Appendix 1) contains fewer independent variables than Table 1. Indeed, our study has shown that some variables that were theorized to impact IC growth do not actually do so. Also, whereas in previous literature, it remained an assumption that IaH activities could affect IC growth, it has now been empirically demonstrated that IaH positively affects the development of intercultural competence. From our study, it has appeared that participation in such activities, together with particular personality traits and the mastery and use of foreign languages impact IC growth. Furthermore, it has appeared that personal data, such as gender, immigrant background, nationality, or socio-economic status, do not affect IC growth, a finding which suggests that irrespective of background, all students at the tertiary level of education can experience growth in IC development. Additionally, the study confirms that personality characteristics can impact IC development.

Discussion

By analyzing a series of factors that can potentially have a bearing on intercultural competence, this study raised the question to what extent Internationalization at Home activities affect this competence in university students. The findings obtained from a regression analysis and complemented with Pearson correlation, T-test, and ANOVA tests show that the personality characteristics ‘openness,’ ‘extraversion’ and ‘agreeableness,’ the mastery and frequency of use of foreign languages, year of education, study abroad, and Internationalization at Home activities have a bearing on students’ intercultural competence. Furthermore, this competence could be shown to grow over the years of study.

The fact that students do not participate more intensely in IaH initiatives, a finding confirming Hofmeyer (Citation2021), and that the participation rate does not increase substantially over the years of study is unfortunate but not wholly unexpected. For one thing, the university itself has only recently started to embed IaH initiatives in university curricula, for example by means of service-learning. For another, the non-curricular IaH initiatives need to gain further familiarity among the KU Leuven student body. Because these initiatives are not normally integrated in the academic curriculum students themselves need to proactively opt in for such initiatives on top of their ordinary course load. Furthermore, the number of foreign students studying for Bachelor’s degrees is very small, something that is largely due to the fact that KU Leuven is a Dutch-medium, not an English-medium university. Finally, it may be the case that, as suggested by Holmes and O’Neill (Citation2012) and Harrison (Citation2015), students refrain from such intercultural contacts for fear of obtaining lower grades. Under these circumstances, it can be understood that Flemish 18-year-olds arriving at a white Dutch-medium university, and having plenty of leisure or academic activities on offer in Dutch, may not feel enticed to participate in activities involving international students, where language may be a barrier to fun and laughter. This may not necessarily be the case for students with a multilingual and/or immigrant background. These students are used to navigating and translating between cultures and languages. Yet, because these students are well embedded in Dutch-medium society, they may also prefer Flemish durable contacts over perhaps more ephemeral contacts with foreign students. When Erasmus students arrive, which tends to be in the second or third year of Bachelor’s programmes, Flemish student study groups have already been formed. Even if superficial contacts between Flemish and foreign students may take place in lecture rooms, Flemish and international groups of students do not necessarily also meet outside the auditorium and may not develop deeper friendships.

In our study, intercultural competence was assessed as a multicomponent concept (Deardorff Citation2006, Citation2009), with elements relating to knowledge, skills, behaviours and attitudes. As our data have shown, when students do participate in IaH initiatives, this has a bearing on their IC. The intercultural competence of students who do participate in IaH initiatives is likely to grow because of increased interactions and intercultural dialogue with people from other cultural backgrounds. This is suggested in Deardorff’s (Citation2006) Dynamic Model of Intercultural Competence. More extensive contacts and interaction with others may lead to deeper socialization in new worlds (Allport Citation1954 as cited in Soria and Troisi Citation2014), which may provoke internal changes in the individual who may gain a more open mindset (also see Li, Mobley, and Kelly Citation2016; Fozdar and Volet Citation2016). These internal changes may elicit external behavioural changes, such as increased participation in intercultural contact situations and intercultural communication. This in turn may lead to attitudinal changes and growing levels of openness and curiosity towards interculture.

The students’ intercultural competence appears to grow over their years of study, which is a fortunate finding, even if it is based on the results of a cross-sectional study, not a study following the same students longitudinally. It suggests that even students who do not actively or frequently participate in co-curricular IaH initiatives, do not study abroad or travel extensively still develop their intercultural competence during their academic studies. Before entering university, Belgian students have been familiarized with different religious, historical and cultural perspectives on the world. They have learned different foreign languages for longer periods of time and leave secondary education with substantial mastery of at least two foreign languages. During secondary education, as part of their curriculum, they have travelled to countries, such as France, the UK, Germany or Italy, and have thus had the chance to experience themselves as European citizens and/or citizens of the world. These foundational cross-cultural competences are further deepened through university courses that aim to broaden the students’ perspectives on the globalizing world. Also, as part of their curriculum, many student groups take obligatory foreign language courses that are specifically geared towards their field of study, which further supports the development of an intercultural and international mindset. Finally, because of the large numbers of international students studying at KU Leuven, students have ample opportunities to interact in meaningful ways with these students. Even when not always making use of this, the surroundings are international and many different languages are heard in the university buildings and in the city of Leuven’s streets.

Though our data have shown a growth in intercultural competence over the years of study, the data also reveal that students from some faculties develop this competence to a lesser degree than students from other faculties. This may be related to the specific field of study or the way in which these students’ curriculum has been conceived. When the curriculum does only occasionally incite students to engage with societal issues relating to cultural differences for example, as is the case, for example, for the curriculum of students of Pharmaceutical Sciences whose studies are highly chemistry oriented, students obtain fewer chances to develop their critical thinking, ethnorelativism or cultural openness. Because of this, these students may also feel less enticed to participate in cocurricular IaH initiatives. Overall, their mindset may be more nationally and locally oriented than that of students of other fields of study, who may be oriented more towards international careers and global issues, such as students who study Bio-Engineering or Foreign Languages. Also, the curricula of students of Social Sciences and Psychology and Pedagogical Sciences include important components that direct students’ attention to the multicultural nature of our society, which may contribute to these students’ relatively speaking higher levels of IC.

A further finding concerns the bearing that the variable ‘mastery and frequency of use of foreign languages’ has on intercultural competence. The better one masters one or more foreign languages and the more frequently one uses them, the more interculturally competent one appears. This finding corroborates earlier studies (e.g. Yu, Vyas, and Wright Citation2020). As all Dutch-speaking students have studied two foreign languages at school, namely French and English, they are all multilingual and have all acquired some familiarity with the cultures typically associated with these languages in Belgium, namely the cultures of France, the U.K., the U.S.A., and Australia. The level of mastery of the English language, in particular, should suffice for students to participate appropriately and with some degree of ease in intercultural communication situations taking place in that language. Making extensive use of social media in English, current student bodies have gained extensive familiarity with, mainly, Anglo-Saxon, but also other cultures. This interculturalization at home via social media may be more powerful than any IaH initiative universities can take (see, for example, Avgousti Citation2018).

Finally, the data shows that gender does not have a significant bearing on intercultural competence in our study, even if we found a significantly higher Mean value for female students’ intercultural competence as compared to that for male students. This finding runs counter to earlier studies (for example, Tompkins et al. Citation2017) that have tried to study gender in isolation rather than including it in a more comprehensive explanatory model, as was done in the present study or in Alfonzo-de-Tovar, Cáceres Lorenzo, and Santana-Alvarado (Citation2017). They too found that gender does not have an obvious impact on the development of IC in their student group.

Our regression model shows that personality characteristics, which have also been studied in isolation previously, have an important bearing on intercultural competence. Students who are more open, extravert and agreeable appear more interculturally competent (see also Ang, Van Dyne, and Koh Citation2006; Li, Mobley, and Kelly Citation2016). This does not come as a surprise since these characteristics together make for a person that is outgoing and likes to get into contact with other people. Such students create more chances for themselves to grow interculturally. Because of their openness and agreeableness, these students may acquire the skill to discern contextualization cues better than other students, just like the skill for quick cultural shifting on the basis of cultural empathy. Because of their openness, their intercultural literacy may be high, which means that they can read foreign cultures better and faster than people with a lower intercultural competence. Also, because of their agreeableness, they are more sympathetic with people all over the world and more sensitive to, for example, the violation of human rights than their colleagues who are less agreeable (also see, Kaya et al. Citation2021).

Conclusion

This study has advanced our understanding of the contribution of Internationalization at home initiatives to the development of intercultural competence in university students studying at a mainly white western university. Whereas in previous literature, this remained an assumption and IaH activities were offered as an alternative to studying abroad, it has now been empirically demonstrated that IaH positively affects the development of intercultural competence.

It has appeared that participation in such activities, together with particular personality traits and the mastery and use of foreign languages together impact IC growth. Thus, the research has been able to show that the theoretical model that was drawn up on the basis of the literature () has had to be refined and that fewer than the assumed factors studied within this stream of research could be shown to be able to explain a certain amount of variance in IC. In particular, it has appeared that personal data, such as gender, immigrant background, nationality, or socio-economic status, do not appear to affect IC growth, a finding which suggests that irrespective of background, all students at the tertiary level of education can experience growth in IC development. Yet, the study confirms that personality characteristics can impact IC development.

Given society’s demand for interculturally competent graduates, universities have started to include intercultural competence as an attainment target for any of the disciplinary studies they offer. In a non-Anglo-Saxon context, this study investigated growth in intercultural competence as well as the factors that have a bearing on it. Our findings have shed new light on the impact Internationalization at Home initiatives, next to study abroad, can have on students’ intercultural competence. Even if student participation in such activities appears to have a positive bearing on intercultural competence, the low degree of participation in such initiatives is unfortunate. Nevertheless, and despite the fact that only about a quarter of students participate in cocurricular IaH initiatives, students’ intercultural competence grows over their years of study, even if the size of growth differs somewhat between faculties. One of the main reasons for this growth seems to be students’ multilingualism and advanced mastery and frequent use of at least one foreign language.

Continuing to invest in students’ multilingualism via professionally-oriented language courses also at university seems to benefit students’ intercultural competence. Offering such courses may be all the more necessary in faculties where students appear less interculturally competent than in other faculties. Other initiatives can be to invest more in promoting student participation in IaH activities, for example through providing study credit for it and creating more diverse initiatives that can cater for diverse student interests and learning goals. High-quality interactions, such as those obtained in service-learning, buddy projects, or joint international development projects, may have to be planned on purpose and included in the curriculum of all students. The costs of intercultural incompetence (Trimble, Pedersen, and Rodela Citation2009) can be high and it is vital to invest in activities necessary to promote cultural literacy and intercultural competence in young adults. Individuals are not born interculturally competent. They become competent through formal and non-formal education, intercultural contacts, and life experiences.

In the future and to further investigate the role IaH initiatives can play in increasing students’ intercultural competence, larger longitudinal replica studies in Belgium, Europe and other parts of the world are needed. Future studies could also encompass longitudinal and observational data on top of cross-sectional self-report data as they were collected in our study. As universities evolve in the way in which they operationalize internationalization at Home, different operationalizations of IaH initiatives will have to be developed, to allow for deep analysis of student participation in such initiatives. From this, new insights may follow and set the ground for programme re-evaluation and optimization. It is hoped that more research about successful IaH initiatives will trickle down to the level of university administrators who will take them to heart and do what is within their power to further internationalize and interculturalize the home campus and curricula to further all students’ intercultural competence.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (82.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Mirjam Eren for her help in data collection and analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lies Sercu

Lies Sercu is a professor of Applied Linguistics and Language Acquisition at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. Her research interests include the fostering of intercultural competence and foreign language learning in education.

References

- Alfonzo-de-Tovar, I. C., M. Cáceres Lorenzo, and Y. Santana-Alvarado. 2017. “Perfil del Estudiante de Erasmus+ en el Desarrollo de su Competencia Intercultural: Estudio de Caso.” RaeL Revista Electronica de Linguistica Aplicada 16: 103. Accessed 2 October 2021. link.gale.com/apps/doc/A530914178/LitRC?u=leuven&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=e90023ae.

- Allport, G. W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison Wesley.

- Ang, S., L. Van Dyne, and C. Koh. 2006. “Personality Correlates of the Four-Factor Model of Cultural Intelligence.” Group & Organization Management 31 (1): 100–123. doi:10.1177/1059601105275267.

- Ang, S., L. Van Dyne, C. Koh, K. Y. Ng, K. J. Templer, C. Tay, and N. A. Chandrasekar. 2007. “Cultural Intelligence: Its Measurement and Effects on Cultural Judgment and Decision Making, Cultural Adaptation and Task Performance.” Management and Organization Review 3 (3): 335–371.

- Avgousti, M. I. 2018. “Intercultural Communicative Competence and Online Exchanges: A Systematic Review.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 31 (8): 819–853. doi:10.1080/09588221.2018.1455713

- Brooks, R., and J. Waters. 2009. “International Higher Education and the Mobility of UK Students.” Journal of Research on International Education 8 (2): 191–209.

- Byram, M. 1997. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume with New descriptors. https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989.

- Deardorff, D. K. 2006. “Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization.” Journal of Studies in International Education 10 (3): 241–266. doi:10.1177/1028315306287002.

- Deardorff, D. K., ed. 2009. The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Eren, M., and L. Sercu. 2019. InterKU-Lturaliteit. Een Mixed Methodsonderzoek Naar het Intercultureel Profiel van KU Leuvenstudenten. KU Leuven: Faculteit Letteren.

- Fantini. 2020. “Reconceptualizing Intercultural Communicative Competence: A Multinational Perspective.” Research in Comparative and International Education 15 (1): 52–61. doi:10.1177/1745499920901948.

- Fantini, A. E., and A. Tirmizi. 2006. Exploring and Assessing Intercultural Competence. World Learning Publications, Paper 1. Brattleboro, VT: SIT Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.sit.edu/worldlearning_publications/1.

- Fozdar, F., and S. Volet. 2016. “Cultural Self-Identification and Orientations to Cross-Cultural Mixing on an Australian University Campus.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (1): 51–68. doi:10.1080/07256868.2015.1119674.

- Griffith, R. L., L. Wolfeld, B. K. Armon, J. Rios, and O. L. Liu. 2016. “Assessing Intercultural Competence in Higher Education: Existing Research and Future Directions.” ETS Research Report Series 2016 (2): 1–44. doi:10.1002/ets2.12112.

- Hammer, M. R., M. J. Bennett, and R. Wiseman. 2003. “Measuring Intercultural Sensitivity: The Intercultural Development Inventory.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 27 (4): 421–443.

- Harrison, N. 2015. “Practice, Problems and Power in Internationalization at Home: Critical Reflections on Recent Research Evidence.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (4): 412–430. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1022147.

- Harrison, N. 2012. “Investigating the Impact of Personality and Early Life Experiences on Intercultural Interaction in Internationalised Universities.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36 (2): 224–237. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.007.

- Hett, E. J. 1993. “The Development of an Instrument to Measure Global-mindedness.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of San Diego. doi:10.22371/05.1993.005.

- Hofmeyr. 2021. “Intercultural Competence Development Through Co-Curricular and Extracurricular At Home Programs in Japan.” Journal of Studies in International Education. doi:10.1177/10283153211070110.

- Holmes, P., and G. O’Neill. 2012. “Developing and Evaluating Intercultural Competence: Ethnographies of Intercultural Encounters.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36 (5): 707–718. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.04.010.

- Kaya, Y., S. Arslan, A. Erbaş, B. N. Yaşar, and G. E. Küçükkelepçe. 2021. “The Effect of Ethnocentrism and Moral Sensitivity on Intercultural Sensitivity in Nursing Students, Descriptive Cross-Sectional Research Study.” Nurse Education Today 100: 104867–104867. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104867.

- Kim, Y. Y. 2015. “Finding a “Home” Beyond Culture: The Emergence of Intercultural Personhood in the Globalizing World.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 46: 3–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.018.

- Knight, J. 2013. “The Changing Landscape of Higher Education Internationalization – For Better or Worse?” Perspectives, Policy and Practice in Higher Education 17 (2): 84–90. 10.1080/13603108.2012.753957.

- Li, M., W. H. Mobley, and A. Kelly. 2016. “Linking Personality to Cultural Intelligence: An Interactive Effect of Openness and Agreeableness.” Personality and Individual Differences 89: 105–110. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.050.

- Rammstedt, B., C. J. Kemper, and I. Borg. 2013. “Correcting Big Five Personality Measurements for Acquiescence: An 18-Country Cross-Cultural Study.” European Journal of Personality 27 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1002/per.1894.

- Sercu, L. 2004. “Assessing Intercultural Competence: A Framework for Systematic Test Development in Foreign Language Education and Beyond.” Intercultural Education (London, England) 15 (1): 73–89.

- Soria, K. M., and J. Troisi. 2014. “Internationalization at Home Alternatives to Study Abroad.” Journal of Studies in International Education 18 (3): 261–280. doi:10.1177/1028315313496572.

- Tompkins, A., T. Cook, E. Miller, and L. A. LePeau. 2017. “Gender Influences on Students’ Study Abroad Participation and Intercultural Competence.” Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice 54 (2): 204–216. doi:10.1080/19496591.2017.1284671.

- Trimble, J. E., P. B. Pedersen, and E. S. Rodela. 2009. “The Real Cost of Intercultural Incompetence: An Epilogue.” In The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence, edited by D. K. Deardorff, 477–492. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yu, B., L. Vyas, and E. Wright. 2020. “Crosscultural Transitions in a Bilingual Context: The Interplays Between Bilingual, Individual and Interpersonal Factors and Adaptation.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 41 (7): 600–619. doi:10.1080/01434632.2019.1623224.