ABSTRACT

The future of the humanities has been the subject of debate in several countries where it is often stated that too many students are accepted into courses that offer relatively poor employment opportunities. In this article, we examine the development in mismatch among master’s graduates in Norway for the period 1995–2015, to see whether this situation is reflected here, and if it applies to all subfields of the humanities. Two types of market mismatch among new graduates are investigated: unemployment and over-education. The findings indicate that master’s graduates in the humanities are slightly more exposed to unemployment than other graduates and clearly more exposed to over-education. The proportion of over-educated graduates increased during the latter part of the 1990s but has been relatively stable since 2003. Graduates in language studies are less frequently mismatched, while graduates in literature, culture studies and philosophy face more challenges. Combined with the fact that labour market mismatch of graduates in the humanities in Norway is substantially lower than neighbouring countries, this suggests that transition from higher education to the labour market for graduates in the humanities should not be perceived as challenging per se, but depends on subfields and contextual factors.

Introduction

While, in general, there has been educational expansion and massification of higher education, the number of humanities graduates in in Europe is decreasing (CitationDatabase – Eurostat). Several studies have shown that graduates in the humanities face a more challenging transition from higher education to work compared to graduates in other fields (see, for example, Louvel Citation2007; Dolton and Silles Citation2001; Kempster Citation2018). They are more likely to encounter unemployment and other forms of labour market mismatch, and make less use of their skills (see, for example, Klein Citation2010; Støren and Arnesen Citation2011) and have lower wages (Støren and Arnesen Citation2011; Louvel Citation2007).

This has led to a debate about the role of the humanities, whether too many students choose these programmes and if programmes in the humanities are sufficiently oriented towards the labour market. This is seen in the UK (Sanders and Addis Citation2010), Denmark (Purtoft Citation2010), Sweden (Fölster, Kreicbergs, and Sahlén Citation2011) as well as Norway (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2017; Nettavisen Citation2017; Samfunnsviterne Citation2018). This debate has been particularly high on the political agenda in Denmark, where labour market prospects for graduates have become one of the criteria for fund allocation in higher education resulting in a reduced number of students in the humanities (Danmarks Statistik Citation2020).

However, few studies have investigated the extent to which the labour market situation for graduates in the humanities has changed over time. Hence, it is not clear whether graduates are more or less exposed to mismatch than previously. Further, few studies distinguish between different study programmes in the humanities, although labour market opportunities may be quite different for graduates in subfields like languages, history, and philosophy. This article augments the existing research by addressing development over time, relating mismatch to graduate numbers and investigating unemployment and over-education for graduates from different subfields in the humanities. We have looked at the period 1995–2015 and controlled for cyclical variation in the labour market, which may affect the different subfields differently. The aim of the article is twofold, (1) to increase the knowledge on transition from higher education to the labour market for graduates in the humanities, taking development over time and subfield into account, (2) to look at factors influencing the likelihood of mismatch and discuss the possible causes for a higher level of mismatch in the humanities in general.

We have used a unique data set: The Norwegian Graduate Survey. This is possibly the longest-running graduate survey in the world (Støren and Nesje Citation2018) and contains information about master’s graduates’ labour market situation six months after graduation. These survey data provide more accurate information on over-education compared to register data and contain more information on the background of the graduates. Such data are, therefore, highly applicable for our purpose.

Previous research on employability of humanities graduates

There are many theories concerning the relationship between education and employment which may explain lower employability for humanities graduates. These emphasize a wide range of factors such as the balance between supply and demand for skills in the labour market, how demand depends on the economic system, training costs, the role of education as a screening device, generic versus specialized competence, values and attitudes, job search behaviour, and institutional regulations and aspects of the educational system and the labour market and structural relations between the two. Below, we examine some studies including such perspectives.

In general, empirical evidence shows that specialists or graduates with professional education have an easier transfer to the labour market than generalists (see for example Verhaest and van der Velden Citation2013; Næss Citation2020). Humanities are usually considered a generalist education with low occupational specificity (see Biglan Citation1973; Klein Citation2010). However, Næss (Citation2020) suggests that some subfields of humanities may be considered as specialist education. He finds that many master graduates in languages find employment in primary and secondary school and language studies may be considered an alternative to teacher education in a Norwegian setting. In any case, subfields in the humanities are relatively diverse, and the level of mismatch may vary between them.

Based on data from Germany, Klein (Citation2010) finds that, using the training-cost model (Glebbek, Wim, and Schakelaar Citation1989) as a theoretical framework, high levels of over-education and mismatch among humanities graduates compared to other fields can explained in part by the lack of occupational specificity believed to characterize the humanities. However, that the humanities are supposedly less selective (with regard to study qualifications) than other fields of study did not seem to matter. Klein also found that structural and institutionalized relationships between education and the labour market are important.

Klein (Citation2010) and Kim and Kim (Citation2003) argue that the process of educational expansion in modern society has led to the greater importance of the field of study as a screening device. This is because the increasing number of tertiary graduates and a decreasing variance in educational credentials means that higher education provides a less reliable signal for employers. Thus, the educational level loses its potential as a filter, and employers therefore rely mostly on other productivity signals such as the specific field of study. This especially pertains to ‘soft fields’ such as the humanities since, according to Klein (Citation2010), they are considered to be less academically challenging. Along the same lines, Reimer and Noelke (Citation2008) argue that the expansion in the number of students has led to a decrease in students’ abilities so that an increasing proportion of students choose what the authors see as less demanding academic fields such as the humanities.

Both Gibbons et al. (Citation1994) and Välimaa (Citation2006) offers possible explanations for insufficient generic competence in a broad sense. Gibbons et al. (Citation1994) argue that the knowledge society is characterized by a new mode of knowledge production with a deeper and broader humanistic understanding of knowledge than in traditional discipline-based knowledge production, thus increasing the demand for the sort of knowledge offered by the humanities. But they think that it is a problem whereby the humanities have become disassociated with the demand side. Välimaa (Citation2006) believes humanistic values and attitudes may be an obstacle to working in the business sector and that they have ways of thinking that do not match commercial enterprises. This pertains to how one talks, dresses and so forth.

Also, institutional characteristics and regulations of the educational system, the labour market and the society could modify these relationships (Klein Citation2010; Assirelli Citation2015). For example, control over access to specific occupations through formal qualification requirements. Further, graduate numbers are a means by which an educational profession can improve labour market outcomes for its members. This is more relevant in occupations based on professional education (e.g. medicine, law, psychology) than in soft fields such as the humanities.

Assirelli (Citation2015) analysed the effect of labour market regulations on the differences between fields of study in credentials and skills mismatches among tertiary graduates in 18 countries 5 years after graduation. Across all the countries, credential mismatch (mismatch between formal education requirements and job requirements) was most common in the arts and humanities. Skills mismatch was also particularly high for these disciplines. Differences in credential mismatch between generalist fields of study, such as the arts and humanities and more job-oriented fields of study were mediated by the level of public employment. The reason for this was that ‘the welfare state [was] able to employ graduates with less marketable credentials such as those from the humanities … ’ (Assirelli Citation2015, 555).

A range of studies have addressed factors affecting the labour market outcomes of higher education graduates in general. Among such factors are gender and age (Verhaest and van der Velden Citation2013), social origin (Bernardo and Ballarino Citation2016; Jacob, Klein, and Iannelli Citation2015), grades from upper secondary school (Joensen Citation2007; Klein Citation2010; Næss Citation2020), and previous working experience (Støren and Arnesen Citation2011). If graduates in humanities constitute a negatively selected group along such dimensions, this may partly explain why they face more challenges entering the labour market.

Basically, we can distinguish between two explanations for why graduates in the humanities face more challenges than other groups in the labour market: there are more graduates than jobs requiring their specialist-competence, or they are perceived to have less generic competence than the other graduates they have to compete against in jobs in which generic competence is more important, either because they are negatively selected in some way or because of the (perceived) relevance and quality of the education. However, differences in employability between subfields of the humanities have received little scholarly attention.

The Norwegian context

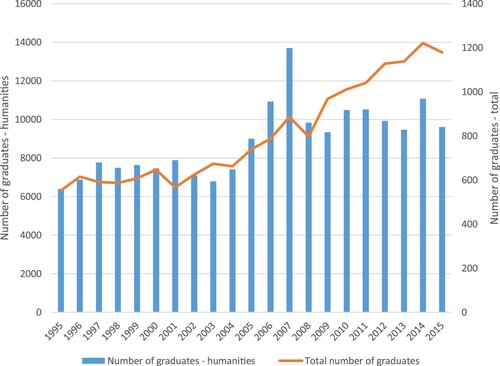

There are several reasons why Norway may be considered to be a relatively favourable country for humanities graduates. First, there has not been a particularly large increase in the number of graduates in humanities compared to other fields of study – see Figure A1. While the number of master’s graduates in Norway more than doubled between 1995 and 2015, the number of master’s graduates in the humanities (not including art and theology) has only increased by 50% (NIFU’s register of academics).Footnote1

Another important aspect of the Norwegian labour market that may be favourable for humanities graduates is a larger public sector compared to the other countries (OECD Citation2015; Nordic Statistics Citation2021). The public sector accounted for 32% of total employment in Norway in 2016 (Statistics Norway Citation2021), and about half of the new HE graduates find jobs in the public sector (Wiers-Jenssen, Støren, and Arnesen Citation2014).

Further, labour market participation in Norway is higher than OECD-average for both men and women, especially for women (OECD Citation2021), and unemployment rates in Norway have generally been low (Nordiska Ministerrådet Citation2018). The worldwide financial crisis starting in 2007/2008 had a less severe impact on Norway than on most other countries, and the economy started recovering already in 2009 (Aamo Citation2018).

In sum, this implies that graduates – also from generic fields of study – are likely to face less challenges entering the labour market, compared to graduates in countries with high general unemployment.

Research questions

This paper addresses the transition from higher education to work among master graduates in the humanities. We examined two indicators of mismatch: unemployment and over-education. These outcomes do not necessarily hit the same groups, hence applying more than one indicator provides a more informative picture of the labour market situation faced by new graduates. According to job-search theory, over-education may be a way to adapt to longer-than-expected job search duration while continuing to search for more relevant employment (Verhaest and van der Velden Citation2013). In this case, both unemployment and overeducation are consequences of a lack of relevant job offers, and the sum of these two situations is highly applicable for measuring the labour market situation short time after graduation.

Central aims are to investigate whether mismatch has changed over time and if the mismatch varies according to subfield in the humanities, e.g. if graduates in languages face the same challenges as graduates in history or philosophy. We pose the following research questions (RQs):

How has the proportion of graduates in the humanities facing challenges in transition from higher education to work (unemployment or over-education) developed between 1995 and 2015, compared to graduates in other fields?

How does mismatch vary between graduates from different subfields in the humanities?

To what extent can mismatch of graduates in the humanities explained by the characteristics of the graduates and the characteristics of the labour market?

Methods

Descriptive analysis

The first part of the analysis is descriptive, analysing how differences in mismatch between fields of study have changed over time (RQ1and RQ2). We also mapped differences in graduate characteristics which may affect mismatch.

Multivariate analysis

In the second part of the analysis, we use multivariate logistic regression to investigate if the level and development in unemployment and over-education differ between humanities and other fields of study (RQ3). Logistic regression is a method frequently used when the dependent variable is dichotomous. As the model includes aggregated explanatory variables, we used robust standard errors. In this analysis, we considered the period commencing 2003 since we have data about grades from upper secondary school from this year. With panel data, we can control for the heterogeneity of the graduates.

We estimate three models stepwise, to analyse causes for possible differences in level and development. In the first model, the estimates show the total differences when controlling for subfield, year and the interaction between year and a dummy-variable for humanities applied to investigate if there has been a significantly different development over time for humanities than for other fields of study.

In the second model, we control for supply/demand-related variables, which is growth in graduate numbers and the general unemployment rate where we also include an interaction variable between the unemployment rate and dummy variables for subfields in humanities. In the third model, we include also graduate characteristics that have been shown to be associated with labour market outcomes in previous studies.

Data

Graduates

Data were drawn from the Norwegian Graduate Survey (Kandidatundersøkelsen) conducted by the Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU). This biennial survey addresses graduates six months after graduation. The target group is graduates from MA programmes (or equivalent) who graduated in the spring semester of the same year that the survey was conducted. Graduates received an invitation to participate in the survey and up to three reminders. The questionnaire contains a range of questions on the transition from HE to work, and graduates were asked to provide information on their situation during a specific week in mid-November.

Data from 1995 until 2015 were included in the analyses. For each of these years, between 2216 and 3917 graduates responded, totalling 34,393 graduates. For some analyses, however, we only look at a subset of these. The number of graduates included in the analyses is shown in the tables. The response rate fell from 78% in 1995 to 51% in 2015. Response rates are slightly higher among graduates in the humanities than the average for other study programmes. The declining response rate is a challenge when collecting survey data in general (see Stedman et al. Citation2019; Boyle Citation2020), and a response rate of more than 50% is high for this kind of survey (Wiers-Jenssen, Arnesen, and Støren Citation2012). Investigations by NIFU did not find that the lower response rate, in general, led to a substantial bias in the results in the Norwegian Graduate Survey (Arnesen Citation2007).

Although there are methodological challenges attached to surveys and self-reported data, such data are generally more suitable for mapping over-education than data from administrative registers. Our survey data contain more detailed information about over-education. Survey data are also better suited for measuring graduate unemployment than register data because graduates are not always registered at the public employment service when they seek employment. Further, our survey data provide information about relevant previous labour market experience, a factor shown to be important to labour market outcomes in previous research (Støren and Arnesen Citation2011).

Applying time series and compiling data for several years enables us to study subgroups of graduates in the humanities, even if the annual number of graduates is small. For some years, when only a sample of graduates was included in the survey, statistics were weighted to give a representative measure for the whole graduate population as in the other years. Where the number of graduates is between 20 and 50, this is shown in parentheses in the tables.

Definitions of variables

Unemployment. The graduate is (a) not in paid work in the reference week, (b) has actively searched for work during the four weeks prior to the reference week, and (c) is able to take employment in the reference week. This definition corresponds to that of the International Labour Organisation.

Over-education refers to having a higher level of education than a job requires. The gap between actual and required education may be defined broadly or narrowly. Over-education may be defined in several ways (see e.g. Dolton and Silles Citation2008). In this paper, we applied a medium-strict definition that is also used in other analyses of the Norwegian graduate survey (Wiers-Jenssen and Try Citation2005; Støren and Wiers-Jenssen Citation2016). Those defined as over-educated are employed in a post where a completed HE qualification is not essential although the graduate regards it as an advantage or where HE is irrelevant to the job.

Labour force. Consists of those who are employed and those who are unemployed according to the definition above.

Subject field. Study programmes in the humanities are categorized into 10 subfields, as shown in (and elsewhere). Graduates in the humanities are compared to master’s graduates in all other fields of study. Note that the composition of the ‘humanities’ is not identical to previous analyses of the Norwegian Graduate Survey, as graduates in the performing arts and theology were not included.

Table 1. Unemployment among graduates in the labour force six months after graduation, by study programme 1995–2015. Per cent.

Academic qualifications. Average grades from upper secondary school (six categories ranging from 1 to 6, where 6 is the highest value).

Sociodemographic characteristics. Age: grouped into three categories: 25 years or younger, 26–29 years and 30 years or older, marital status: married/cohabitant or not, children aged 6 or less: dichotomous variable separating between graduates who have young children and graduates who have not, parents’ educational level: three groups: neither parent has higher education, at least one of the parents have education at the bachelor degree level, at least one of the parents have education at the master degree level.

Human capital. Previous work experience, not relevant and relevant, and previous education (yes or no).

Aggregate labour market data. Relative growth in the number of graduates by subject field (from NIFU’s Akademikerregister), general unemployment rate (Statistics Norway Citation2020).

Results

Development over time compared to other fields of study

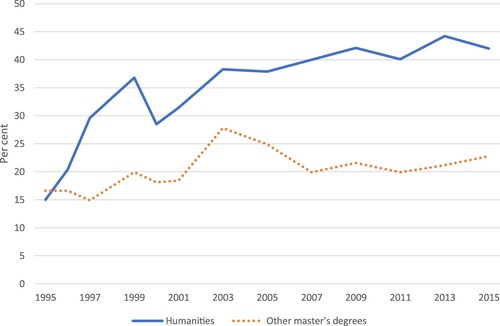

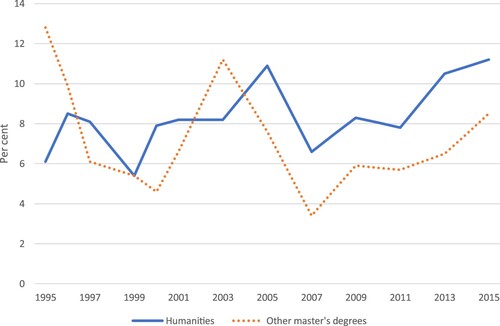

This section addresses the first research question; how have mismatches in the humanities developed over time, compared to graduates in other fields of study. shows unemployment among graduates in the labour force six months after graduation. At the beginning of the observation period, graduates in the humanities had a lower level of unemployment than other master’s graduates. But just after the turn of the millennium, it has generally been higher. Since 2007, unemployment has increased at a similar pace for graduates in the humanities as in other fields, being about 2.5 percentage points higher for graduates in the humanities. Estimated for the entire period, there has been a significant (1% level) annual larger increase in unemployment for graduates in humanities than for other graduates. The test is a logistic regression where year, a dummy variable for humanities and an interaction term between year and the dummy variable for humanities are the control variables. also shows that fluctuations in unemployment rates are less pronounced for graduates in the humanities than in other subject fields. One explanation for this is that a larger proportion of graduates from other fields of study transfer to the private sector, where changes in the economic situation have a larger impact on the demand for labour.

Figure 1. Unemployment among master graduates in the labour force six months after graduation 1995–2015. Per cent.

shows the percentage of graduates in the labour force who are over-educated according to our (medium strict) definition, six months after graduation. We find a very different pattern than for unemployment, showing the relevance of taking more than one indicator into account when measuring mismatch. At the beginning of the period, the proportion was similar for graduates in the humanities and other fields, but a steep growth in over-education among graduates in the humanities has been observed in the latter part of the 1990s and has been about twice as high as for other graduates since 2007. Using the same methodology as for unemployment, we find a significant (1% level) annual increase over time in the probability of overeducation for humanities compared to other graduates, for the whole of the period.

As mentioned, the growth in the number of graduates has been lower in the humanities than in other fields of study. As neither unemployment nor overeducation have declined in the period investigated, this indicates that the mismatch for graduates in the humanities is not primarily caused by an excessive supply of graduates.

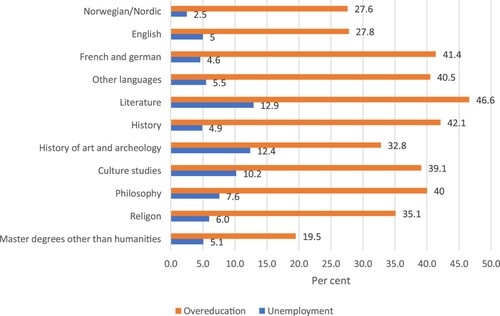

Differences between subfields

We now move on to mapping differences between subfields of the humanities (RQ2), including changes over time. shows unemployment rates six months after graduation for the subfields in the humanities for three time periods. Large and persistent differences between the subfields can be found. Unemployment rates are lower than average for graduates in some languages (Norwegian and Nordic studies and English). For Literature, History of Art and Archaeology, and Culture studies and Philosophy on the other hand, the unemployment rate has been substantially higher. For English and Philosophy, we found a significant increase in the unemployment rate over time, however, for English, the starting point was very low. Other changes over time are not statistically significant.

shows over-education six months after graduation for the same three periods. There are substantial variations between subfields in the humanities. The highest rates throughout the period can be found for Literature, Culture studies and Philosophy, and Other languages (more than 40%). For English, and French and German and History of art and Archaeology moderate rates can be found. The lowest rate is found for graduates in Norwegian and Nordic studies. We observed increasing proportions of over-education over time in Other languages, History, History of Art and Archaeology and Philosophy. These mostly took place between periods 1 (1995–2000) and 2 (2001–2007).

Table 2. Over-education among employed graduates six months after graduation, 1995–2015. Per cent.

Factors influencing mismatch

If graduates in the humanities differ from graduates in other fields of study regarding characteristics that are generally shown to influence labour market outcomes, this may explain why they are more likely to experience mismatch six months after graduation. Graduates in the humanities diverge from graduates in other fields of study in their higher proportion of women and being somewhat older (Appendix ). While being a woman seems to be an advantage in the transition from higher education to work in the Norwegian labour market (Støren and Nesje Citation2018; Statistics Norway Citation2020), being older is not, even if it involves more general labour market experience (see for example Salas-Velasco Citation2007). However, relevant work experience prior to graduation has been shown to be an advantage (Støren and Arnesen Citation2011), and graduates in the humanities have less such experience. Grades from upper secondary education are on average similar for graduates in the humanities and other fields of study. Hence, they do not generally constitute a negatively select group in this respect, as seen in some other studies (Reimer and Noelke Citation2008; Klein Citation2010). Graduates in literature and some language programmes have better grades from upper secondary school, which theoretically could give them a competitive edge in the labour market.

Multivariate analysis

Lastly, we analysed the association between the explanatory variables on unemployment and over-education (RQ3) using logistic regression in three different models. Model 1 includes dummy variables for subfield, year (–2003) and an interaction term for year and a dummy variable for humanities as explanatory variables that show the total difference between humanities subject and other fields of studies. Model 2 also includes aggregate labour market variables pertaining to the balance between supply and demand (number of graduates relative to the number in 2003 and general unemployment rate). Model 3 also includes graduate characteristics as described in the methods section. and show the results for unemployment and overeducation, respectively.

Table 3. Logistic regression of the probability of unemployment for graduates in labour force. 2003–2015.a,b

Table 4. Logistic regression of the probability of overeducation for graduates in labour force. 2003–2015.a,b

Unemployment

Model 1 shows that graduates in Norwegian and Nordic studies and History have a lower probability of unemployment than other graduates, while this is not the case for other subfields of humanities. No significant change over time is observed, neither for humanities nor other graduates. In Model 2, we find a positive year-effect for humanities, but not for other fields of study. The general unemployment rate in society increases unemployment also for graduates, but we find no significant difference between humanities and other fields of study. The effects of subfield of humanities remain mainly the same, with the exception that a degree in history is no longer significant.

Model 3 shows that unemployment is associated with several graduate characteristics. Good grades from upper secondary school, relevant labour market experience and having additional higher education completed before the master’s degree reduced the probability of unemployment. Women have a lower probability of becoming unemployed than men. Being married/cohabitant reduced the risk of unemployment, while having small children had the opposite effect. Higher age increases the likelihood of unemployment.

Over-education

Most subfields of humanities have a higher probability of being over-educated compared to other graduates. The exceptions are Norwegian and Nordic studies, English and Philosophy. For humanities, there has also been a significant increase over time, which is not the case for graduates in other fields. In Model 2, where we control for labour market variables, we find that the number of graduates increases the likelihood of overeducation. Since graduate numbers have increased less for humanities than other fields of study, this has dampened the difference regarding over-education between humanities and other fields of study. The general unemployment rate increases the likelihood of over-education, but we find no significant difference in the effect between humanities and other fields of study. In this model, we also found and a negative general year-effect for overeducation. The effects of the subfield of humanities remained mainly the same.

Model 3 shows that several graduate characteristics are associated with over-education. Good grades from upper secondary school, and labour market experience relevant to the education, and additional education to the masters’ degree reduce the likelihood of over-education. So does being married/cohabitant and having children of the age 6 or less, and having parents with higher education, while high age increased the probability including graduate characteristics did not substantially alter the estimated effect of subjects or the labour market variables. The general trend-effect became negative, but it was still higher and positive for humanities.

Estimated effects

To give a picture of the relative importance of each independent variable, we have in used the estimated coefficients (Model 3) to calculate the probability of unemployment and over-education in 2015, given various combinations of the explanatory variables. The ‘base case’ is master’s graduates in fields other than the humanities, male aged 26–29, married/cohabitant, average grades from upper secondary school, relevant labour market experience, and growth in graduate numbers as for other graduates (not humanities) and the general unemployment rate and trend-variable value for 2015. These assumptions are retained for the other cases, except that we assumed that the graduate has a degree in different subfields in the humanities.

Figure 3. Estimated probabilities for unemployment and over-education 2015, six months after graduation for specific categories of graduates.

The overall picture is that we find the same differences between subfields and between humanities and other fields of study as in and . This implies that the differences cannot be explained by differences in graduate characteristics or differences in growth in graduate numbers. Norwegian/Nordic and English stand out as somewhat more successful than the other subjects, but the probability of over-education is substantially higher than graduates from other fields also for these subjects.

Sum up and discussion

Six months after graduation, master’s graduates in the humanities, in general, are slightly more at risk of facing unemployment compared to the average for all higher education graduates while the risk of over-education is clearly higher. A substantial increase in over-education is observed from 1995 to 2003 but has stabilized since. This diverging pattern illustrates the importance of considering more than one indicator when analysing the transition from HE to work.

The increase in over-education in the latter half of the 1990s may partly be explained by an increase in the number of graduates, but, in general, the association between graduate numbers and mismatch was weak. This is in line with previous findings from Norway (Støren and Wiers-Jenssen Citation2016).

We found that graduates in the humanities diverged somewhat from graduates in other fields, but, in general, they are not ‘negatively selected’ regarding abilities, as observed in the studies of Klein (Citation2010) and Reimer and Noelke (Citation2008). However, they had less relevant working experience prior to graduation (not shown), which does affect the transition to the labour market negatively. Most subfields of humanities are dominated by females, but we find that being a female is not a disadvantage regarding unemployment and over-education.

Our analyses draw a more nuanced picture of the transition from HE to work among graduates in the humanities, as we find substantial differences between subfields. Graduates in languages (Nordic and English) have experienced good labour market prospects throughout most of the period; unemployment rates have been lower than for other graduates in humanities, as well as for higher education graduates in general. This is particularly true for those who hold a degree in Nordic languages, partly explained by the fact that these tend to find work in the education sector where such skills are in high demand (Wiers-Jenssen et al. Citation2016). Hence, the rather gloomy picture often drawn of the labour market prospects for graduates in the humanities does not apply to all subfields; some groups are actually better off than graduates in general. Future research could look more into the reasons why such differences occur and investigate whether similar patterns occur in other countries.

Some subfields of humanities clearly face challenges. Graduates in literature, philosophy and history of ideas, history of art and archaeology and culture studies experience unemployment rates above 10% six months after graduation, and more than 40% are over-educated. Even though the mismatch has been quite stable in recent years, and that other studies have documented that mismatch is substantially reduced over time following graduation (Arnesen, Støren, and Wiers-Jenssen Citation2013), the situation may still be a matter of concern from the perspective of individuals, higher education institutions and society.

A possible cause for mismatch may be lower (perceived) labour market relevance. This is supported by the results from the Norwegian Graduate Survey for 2017, showing that graduates in the humanities were substantially less satisfied with the labour market relevance of the education than other graduates (Støren and Nesje Citation2018). Further, it is shown that the demand for graduates in the humanities is low in the private sector (Rørstad, Børing, and Solberg Citation2022).

Still, we note that the level of mismatch is quite moderate compared to the situation in many other countries. Studies from neighbouring countries Denmark and Finland show unemployment rates are twice as high for graduates in the humanities compared to other fields of study (Statistics Denmark Citation2017; Statistics Finland Citation2017).

Graduate characteristics and experiences displayed significant effects on mismatch, previous relevant work experience in particular. Still, the effects were relatively small and the difference between graduates in the humanities and other graduates remained largely unexplained. Potential explanations may be: (1) unobserved negative selectivity in choice of education, (2) study programmes in humanities develop less relevant generic competence than other fields of study or (3) at least concerning unemployment, wages may be more rigid than for other fields of study. These explanations may also be relevant for understanding differences between subfields of the humanities, and we will discuss these explanations below.

If the explanation is unobserved negative selectivity, this could be because people with certain personal traits or motivations are more likely to choose to enter study programmes in the humanities. For example, a study including data from several European countries shows that graduates in the humanities were more motivated by academic inquiry and less motivated by economic returns than many other groups of graduates (García-Aracil Citation2008).

That the higher level of mismatch could be due to the generic content of the education may be supported by an OECD report (OECD Citation2018) about the labour relevance of Norwegian higher education. The report emphasizes the importance of a list of transversal skills that may be emphasized in the humanities the same as in other fields of study, such as numerical skills.

Humburg, van der Velden and Verhagen (Citation2013) state that employers prefer graduates who are instantly deployable. If they perceive that hiring graduates from the humanities involves more training costs, this may make them more reluctant to hire such graduates, in line with the training cost model (Glebbek, Wim, and Schakelaar Citation1989). Employers may not see the full potential of graduates in the humanities and may overlook generic skills such as analytic thinking or communication skills.

If greater mismatch is due to a mismatch between demand and supply, one explanation is that many choose a study field according to interest, and do not always consider future labour market prospects. In Norway, this may also have to do with study financing. Students are entitled to universal and publicly funded loans and grants, hence educational choices may be less influenced by parents. Further, higher education is mostly free, hence the economic investments are lower than in countries where tuition fees are widespread.

The relatively good situation for graduates in Norway can largely be explained by the fact that the unemployment rate in Norway, in general, is lower than in many other countries (OECD Citation2020). This may be an advantage for groups with a lower demand in the labour market. Further, in line with Assirelli (Citation2015), a large public sector may also contribute to explaining employment opportunities, as most graduates in the humanities find jobs in the public sector.

We also observe that increase in the number of graduates in the humanities has been lower than in most other master programmes. This may be seen as an indication that the higher education system has the ability to adapt the educational capacity according to demands in the labour market; alternatively, it could be that the students respond to the signals in the labour market. Hence, the type of government control of capacity implemented in Denmark may not be a necessary or adequate tool for keeping mismatch at a reasonable level.

Limitations of the study

We have documented substantial and persistent differences between subfields, but a limitation of the study is that we have not been able to explain the causes for mismatch in different subfields in detail. Another limitation is that the graduates in our study were surveyed six months after graduation, and many graduates need more time to find suitable employment. Surveys conducted several years after graduation show that the apparent mismatch is significantly reduced over time, though less so for graduates in the humanities than for graduates in other fields (Arnesen, Støren, and Wiers-Jenssen Citation2013). Further, we have no information about the extent to which the labour market outcomes correspond to the expectations of the graduates. It may be that they were expecting to meet challenges in the transition from higher education to work and that they are not too worried about the situation so close after graduation. Studies investigating the relationship between expectations and outcomes may be topics for further research.

Implications for practice

The results suggest no need for great concern regarding the transition from higher education to work for graduates in the humanities in Norway per se, but that graduates in some subfields must be prepared to meet more challenges than others. The results also indicate a potential for improving the transition process and that the graduates, higher education institutions and employers, may contribute to this. Our analyses show that relevant employment experience prior to graduation reduces the risk of unemployment and over-education significantly. Hence, students may consider a more strategic approach regarding the kinds of job they take when they are studying. Higher education institutions may also take more responsibility regarding linking graduates and the labour market by facilitating internships and other forms of cooperation with employers. A study by Thune and Støren (Citation2014) showed that graduates who have experienced formal cooperation with the world of work through studies have a smoother transition to the labour market. However, such experiences are less common among graduates in the humanities than in other fields (Næss et al. Citation2012).

Further, employers may benefit from closer cooperation with higher education institutions by engaging master students, e.g. through internships. In this way, employers may learn more about their competences and students get the chance to learn about the needs of employers. A study by Støren and Nesje (Citation2018) also finds that graduates in the humanities are substantially less content with the relevance of the education for working life than other master graduates in Norway. A recent white paper (Ministry of Education Citation2021) encourages more cooperation between higher education institutions and the world of work, including internships also for students in generic fields of study. If the suggested measures are implemented, this may strengthen the employability of graduates in the humanities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Terje Næss

Terje Næss is a senior consultant at Nordic Institute for Studies in Research and Higher Education in Norway (NIFU).

Jannecke Wiers-Jenssen

Jannecke Wiers-Jenssen is associate professor at the Centre for the study of Professions, Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet) in Oslo, Norway.

Notes

1 For the humanities there has been no growth between 2006 and 2015, while the total graduate numbers increased by 50% in the same period.

References

- Aamo, B. S. 2018. “The Financial crisis and Norway.” Rethinking Economics, Norway.

- Arnesen, CÅ. 2007. Arbeidsmarkedstilpasning i perioden 2000–2004 for kandidater utdannet våren 2000 [Labour Market Situation in the Period 2000–2004 for Graduates Education Spring 2000]. Rapport 16/2007. Oslo: Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education.

- Arnesen, CÅ, L. A. Støren, and J. Wiers-Jenssen. 2013. Tre år etter mastergraden – arbeidsmarkedssituasjon og tilfredshet med jobb og utdanning [Three Years After Graduation – Labour Market Situation and Satisfaction with Job and Education]. Report 41. Oslo: Nordic Institute for studies in Innovation, Research and Education.

- Assirelli, G. 2015. “Credential and Skill Mismatches Among Tertiary Graduates: The Effect of Labour Market Institutions on the Differences Between Fields of Study in 18 Countries.” Europeans Societies 17 (4). doi:10.1080/14616696.2015.107226.

- Bernardo, F., and G. Ballarino, eds. 2016. Education, Occupation and Social Origin. A Comparative Analysis of the Transmission of Socio-Economic Analysis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Biglan, A. 1973. “The Characteristics of Subject Matter in Different Academic Areas.” Journal of Applied Psychology 57: 195–203.

- Boyle, J. 2020. “Declining Survey Response Rates Are a Problem – Here’s Why.” ICF. https://www.icf.com/insights/health/declining-survey-response-rate-problem.

- Danmarks Statistik. 2020. https://statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1536.

- Database – Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/help/first-visit/database.

- Dolton, P., and M. Silles. 2001. Over-Education in the Graduate Labour Market: Some Evidence from Alumni Data. Centre for the Economics of Education. London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Dolton, P., and M. Silles. 2008. “The Effects of Over-Education on Earnings in the Graduate Labour Market.” Economics of Education Review 27 (2): 125–139.

- Fölster, S., J. Kreicbergs, and M. Sahlén. 2011. Konsten att strula til ett liv Om ungdomars irrvägar mellan skola och arbete [The Art of Making a Mess of a Life. About Teenagers Irregular Paths Between School and Employment]. Stockholm: Svenskt Näringsliv.

- García-Aracil, A. 2008. “College Major and the Gender Earnings Gap: A Multi-Country Examination of Postgraduate Labour Market Outcomes.” Research in Higher Education 49: 733–757.

- Gibbons, M., C. Limoges, H. Nowotny, S. Schwartzman, P. Scott, and M. Trow. 1994. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage.

- Glebbek, A., N. Wim, and R. Schakelaar. 1989. “Field of Study and Flexible Work: A Comparison Between Germany and UK.” Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences 25/2: 57–74.

- Humburg, M., R. van der Velden, and A. Verhagen. 2013. “The employability of Higher Education Graduates: The Employers’ Perspective.” Final Report. European Union.

- Jacob, M., M. Klein, and C. Iannelli. 2015. “The Impact of Social Origin on Graduates’ Early Occupational Destinations – An Anglo-German Comparison.” European Sociological Review 31 (4): 460–476.

- Joensen, J. S. 2007. Academic and Labour Market Success: The Impact of Student Employment, Abilities, and Preferences. Department of Economics, Stockholm School of Economics.

- Kempster, H. 2018. “Humanities Overview.” In What Do Graduates Do? 2018/19 Insights and Analysis from the UK’s Largest Higher Education Survey, 42–48. UK: Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services.

- Kim, A., and K. Kim. 2003. Returns to Tertiary Education in Germany and the UK: Effects of Field of Study and Gender. Working Paper Nr. 62. Mannheim: Universit ät Mannheim.

- Klein, M. 2010. Mechanisms for the Effect of Field of Study on the Transition from Higher Education to Work. Working Papers Nr. 130. Mannheim: MZES (Mannheimer Zentrum für Europäische Sozialforschung.

- Louvel, S. 2007. “A Place for Humanities Graduates on the Labour Market in the So-Called Knowledge Society: The French Case.” Higher Education in Europe 32 (4): 291–304. doi:10.1080/03797720802065957.

- Ministry of Education. 2021. “Utdanning for omstilling- Økt arbeidslivsrelevans i høyere utdanning.” [Education for Transformation – Increased Relevance in Higher Education.] Meld. St. 16.

- Ministry of Education and Research. 2017. Meld. St. 25 (2016–2017), Humaniora i Norge [Humanities in Norway]. Oslo: Ministry of Education and research.

- Nettavisen. 2017. https://www.nettavisen.no/na24/nho-sjefen-vil-fjerne-mange-av-norges-900-masterutdanninger/3423298088.html.

- Nordic Statistics. 2021. https://pxweb.nordicstatistics.org/pxweb/en/Nordic%20Statistics/Nordic%20Statistics__Labour%20market__Employment/LABO01.px/table/tableViewLayout2/?rxid=4bd7ba15-3c4a-4793-8711-6db1fc878223.

- Nordiska ministerrådet. 2018. Nordisk statistik 2018 [Nordic Statistics]. København: Danmarks Statistik. doi:10.6027/ANP2018-818.

- Næss, T. 2020. “Master’s Degree Graduates in Norway: Field of Study and Labour Market Outcomes.” Journal of Education and Work 33 (1): 1–18.

- Næss, T., T. Thune, L. A. Støren, and A. Vabø. 2012. Samarbeid med arbeidslivet i studietiden Omfang, typer og nytte i studietiden [Cooperation with the Working Life While Studying. Amount, Types and Benefit While Studying]. Report 48/2012. Oslo: NIFU.

- OECD. 2015. “Employment in the Public Sector.” In Government at a Glance 2015. Paris: OECD. doi:10.1787/gov_glance-2015-22-en.

- OECD. 2018. Higher Education in Norway: Labour Market Relevance and Outcomes. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2020. OECD Labour Force Statistics 2020. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2021. “OECD Statistics.”

- Purtoft, M. 2010. Too Many Humanities Graduates, Says Industry. Article in University Post 25. June. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen.

- Reimer, D., and C. Noelke. 2008. “Labor Market Effects of Field of Study in Comparative Perspective. An Analysis of 22 European Countries.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49 (4–5): 233–256.

- Rørstad, K., P. Børing, and E. Solberg. 2022. “NHOs kompetansebarometer 2021.” Report 3 Nordisk institutt for studier av Innovasjon, forskning og utdanning.

- Salas-Velasco, M. 2007. “The Transition from Higher Education to Employment in Europe: The Analysis of the Time to Obtain the First Job.” Higher Education 54: 333–360.

- Samfunnsviterne. 2018. “Behovet for humanister vil øke i fremtiden.” https://www.samfunnsviterne.no/Nyhetsarkiv/2018/Behovet-for-humanister-vil-oke-i-framtiden.

- Sanders, C., and M. Addis. 2010. “What Is the Value of a Humanities Degree?” In Graduate Market Trends Autumn. www.prospects.as.uk/gmtregister.

- Statistics Denmark. 2017. http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/selectvarval/saveselections.asp.

- Statistics Finland. 2017. “Statistics Finland’s PX-Web Databases.” http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__kou__sijk/statfin_sijk_pxt_001.px/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=39339fbf-d60f-460d-89e2-83e1d61d7f15.

- Statistics Norway. 2020. “Labour Force Survey. Labour Force Survey – Tables – SSB.”

- Statistics Norway. 2021. “13122: Sysselsatte per 4. kvartal, etter sektor, statistikkvariabel og år. Statistikkbanken (ssb.no).”

- Stedman, R. C., N. A. Connely, T. A. Herbelein, D. J. Decke, and S. B. Allred. 2019. “The End of the (Research) World as We Know It? Understanding and Coping with Declining Response Rates to Mail Surveys.” Society and Natural Resources 32 (10): 1139–1154.

- Støren, L. A., and C.Å Arnesen. 2011. “Winners and Losers.” In The Flexible Professional in the Knowledge Society, edited by J. Allen and R. Van der Velden, 199–240. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Støren, L. A., and K. Nesje. 2018. Kandidatundersøkelsen 2017. Nyutdannede masteres møte med arbeidslivet og vurdering av relevans, studiekvalitet og læringsutbytte [Master Graduates Encounter with Work Life and Assessment of Relevance, Study Quality and Learning Outcomes]. Report 22. Oslo: NIFU.

- Støren, L. A., and J. Wiers-Jenssen. 2016. “Transition from Higher Education to Work: Are Master Graduates Increasingly Over-Educated for Their Jobs?” Tertiary Education and Management 22 (2): 134–148.

- Thune, T., and L. A. Støren. 2014. “Study and Labour Effects of Graduate Student’s Interaction with Work Organisations During Education. A Cohort Study.” Education + Training 57 (7): 702–722.

- Välimaa, J. 2006. “Analysing the Relationship Between Higher Education Institutions and Working Life in a Nordic Context.” In Higher Education and Working Life: Collaborations, Confrontations and Challenges, edited by Paivi Tynjala, Jussi Valimaa, and Gillian Boulton-Lewis, 35–53. Emerald.

- Verhaest, D., and R. van der Velden. 2013. “Cross-Country Differences in Graduate Overeducation.” European Sociological Review 29 (3): 642–653.

- Wiers-Jenssen, J., CÅ Arnesen, and L. A. Støren. 2012. Kandidatundersøkelsen – design, utviklingsmuligheter og internasjonale perspektiver [The Graduate Survey – Design, Development and International Perspectives]. Working Paper 7. Oslo: NIFU.

- Wiers-Jenssen, J., T. Næss, K. I. R. Kittelsen, and S. B. Fekjær. 2016. Humanister i arbeidslivet. Report 17/2016. Oslo: Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences.

- Wiers-Jenssen, J., L. A. Støren, and CÅ Arnesen. 2014. Kandidatundersøkelsen 2013 [The Graduate Survey 2013]. Report 17. Oslo: NIFU.

- Wiers-Jenssen, J., and S. Try. 2005. “Labour Market Outcomes of Higher Education Undertaken Abroad.” Studies in Higher Education 30: 681–705.

Appendix

Table A1. Graduates’ background 1995–2015. Per cent.