ABSTRACT

Attention to shaping the direction of one’s career according to personal needs and preferences is growing. However, there is limited understanding how contextual antecedents affect career authenticity. Moreover, little is known about whether antecedents of career authenticity operate in the same way for men compared to women and if the impact of these antecedents differs per position. In this study, we contribute to these gaps in the literature by analysing the role of five antecedents of career authenticity in the academic context. Our analysis is based on a cross-sectional survey collected among a sample of 398 academics working in The Netherlands. It shows that justice in promotion practices is the most important contextual antecedent in explaining career authenticity in academia. After analysing the data using multi-group Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), we found that some antecedents relate differently to career authenticity for men compared to women. Our data also showed how most antecedents operate differently per academic rank. These insights show that higher education institutes can boost their academics’ career authenticity but should tailor such actions to academics of different genders and in different positions.

Introduction

To stay true to yourself is a frequently shared counsel in organisational settings. A key outlet through which employees can express their authentic self is the direction of their careers, a concept known as career authenticity (Shockley et al. Citation2016). Being ‘authentic’ at work has been positively related to in-role performance, work engagement, and favourable well-being outcomes (Cha et al. Citation2019), and authenticity is one of the main elements that contribute to the experiences of an inclusive workplace (Shore, Cleveland, and Sanchez Citation2018). Surprisingly, although research has demonstrated these positive consequences of authenticity, there is little empirical research into which specific individual and organisational characteristics influence it (Cha et al. Citation2019).

In academia, many institutions have committed themselves to an inclusive work environment that fosters the sense of uniqueness and belonging among their faculty (Stanley et al. Citation2018; Vinkenburg Citation2017). At the same time, many universities have adopted New Public Management (NPM) practices. These practices go hand-in-hand with more standardised processes such as metrifications (Bloch et al. Citation2022), in which research success is key to career success (Siekkinen and Ylijoki Citation2021). Sutherland (Citation2017) has shown, for example, that this narrowly defined view of success leads to consternation and confusion among academics with other aspirations for their career. Taken together, NPM practices seem to be at odds with striving for career authenticity due to the underlying ‘one size fits all’ ideology (van den Brink and Benschop Citation2014). This situation stresses the need for research on how to foster career authenticity in the academic setting to fully tap into its intended outcomes.

In this paper, we aim to answer the following research question: What is the influence of individual and contextual antecedents on career authenticity in academia? The first group of antecedents concerns individual assets and is rooted in agentic career literature. The second cluster of antecedents looks at contextual elements and draws on HRM, promotion practices and career shocks literature. Our study aims to contribute to existing research through our focus on contextual antecedents. There are two specific reasons for this focus. First, career authenticity is inherently contextual and not exclusively a personal asset. Several researchers have demonstrated, for example, the important role of the academic career script in subjective career advancement experiences (van Helden et al. Citation2023). However, most authenticity studies have adopted an agentic perspective (Cha et al. Citation2019). Second, we intend to offer insight to organisations regarding how to increase and maintain their diversified workforce. Until now, universities have had little empirically substantiated guidance on how to support academics realising authentic careers. Despite the commitment of universities to create inclusive work environments (Stanley et al. Citation2018; Vinkenburg Citation2017), the pervasive notion of the ideal agentic academic persists (van Veelen and Derks Citation2021), along with its rigid academic career track (van Helden et al. Citation2023).

Nevertheless, it is likely that antecedents of career authenticity differ between individuals. One example of this is that in academia, the ideal career norm seems to be forged around men (O’Connor et al. Citation2021; Stanley et al. Citation2018). Members of devalued social identity groups, such as women (van Laer, Verbruggen, and Janssens Citation2019), may consequently experience more challenges around manifesting their own identity and preferences in their career track. Furthermore, academics’ needs, resources and expectations for their career differ between career positions (Cohen Citation1991; Sanders et al. Citation2022; Dorenkamp and Süß Citation2017). Therefore, our aim is to study whether the influence of individual and contextual antecedents on career authenticity is different between genders or academic ranks.

In this paper, we study the role of five antecedents and its potential differences among subgroups, based on an online survey conducted among postdocs, assistant professors, and associate professors from a Dutch university and its associated academic medical centre. In our approach, we follow the advice as noted in a recent special issue on the topic of career building (Siekkinen and Ylijoki Citation2021), namely, to unravel potential ‘new’ invisibilities among different groups in academia.

Theoretical framework and development of hypotheses

Research increasingly recognises the importance of subjective career success indicators—such as career authenticity—yet most studies focus on subjective success in terms of career satisfaction (Ng and Feldman Citation2014; Shockley et al. Citation2016). According to Shockley et al. (Citation2016, 139), career authenticity (CA) is defined as ‘shaping the direction of one’s academic career according to personal needs and preferences’. We reviewed several strands of literature for the (1) individual and (2) contextual antecedents most likely to be related to career authenticity and included in our study five antecedents. For the first set of antecedents, we noticed that in career research, most studies approach subjective career success by focusing on the efforts of the individual career agent. One illustration is the protean career and the boundaryless career discourses, stating that one’s own abilities and contributions—such as networking, and other individual career management activities—are key aspects in career development (Briscoe and Hall Citation2006; Baruch and Hall Citation2004). However, an individual is embedded in their organisational context. As such, the second set of antecedents relate to the contextual level, based on insights from HRM, promotion practices, and career shocks literature. One illustration is the utilisation of social exchange theory to explore the role of organisational promotion practices in determining career authenticity (Colquitt and Rodell Citation2011).

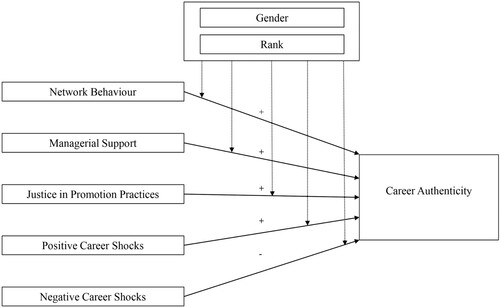

In what follows, we first discuss the five building blocks of our conceptual framework (see for a visual overview). We then address the gender and rank differences we expect to find in the data.

Individual antecedent: network behaviour (1)

In our framework, we focus specifically on individual network behaviour. This antecedent is consistently described as important for academic career advancement because networks provide technical, social, and strategic capital (van Helden et al. Citation2021). Networking behaviour entails attempts to build, maintain, and use relationships with others for the purpose of mutual benefit (Forret and Dougherty Citation2004). Information processing theory highlights the importance of information exchange within networks in shaping individuals’ attitudes, behaviours, and beliefs (Salancik and Pfeffer Citation1978). Networking may help one to explore career possibilities, provide cues to interpret work-related situations, or increase the likelihood of career goal attainment (Noe Citation1996). Academics who engage in network activities might develop a more elaborate idea on what they want to achieve and how they want to achieve it. We therefore view individual network behaviour as a behavioural competency that academics want to build and maintain as it may result in more insight into how to achieve a self-directed and values-driven career.

Contextual antecedents: managerial support (2), justice in promotion practices (3), positive career shocks (4) and negative career shocks (5)

Managerial support within the context of career authenticity refers to whether supervisors behave in ways that help employees to reach their authentic career (Greenhaus, Parasuraman, and Wormley Citation1990). HRM literature stresses the important role of line managers in employee development. The impact of most career development policies relies on supervisors’ action, and, as such, they form an important link between ‘static’ career policies and employees’ career development experiences (Purcell and Hutchinson Citation2007). Put more precisely, these supervisors generally have a degree of influence on what career practices are implemented as well as on how these practices are implemented. As some aspects of career rules are more implicit and not fully stored on paper (Sutherland Citation2017), it can be challenging to identify and interpret the possibilities of academic career-building, and supervisors may offer support by clarifying promotion practices. Furthermore, they can provide career advice and act as role models. As such, they can be critical for subjective career success (Dorenkamp and Süß Citation2017). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that low general supervisor support and low supervisor career-related support was strongly associated with lower subjective career success (Ng and Feldman Citation2014). The crucial role of supervisors in individual career experiences is also asserted in the literature on organisational inclusion. In their recent review study, Shore, Cleveland, and Sanchez (Citation2018) emphasised the role of supervisors in stimulating talent and underlined that they are liable to influence perceptions of work climate. As the academic setting is characterised by uncertainty and ambiguity due to the presence of competition (O’Connor et al. Citation2021) and implicit rules (Sutherland Citation2017), we expect that managerial support is an essential condition for experiencing career authenticity.

Aside from dyadic follower-leader relationships, justice in promotion practices seems a relevant condition for career authenticity in academia. Organisational justice within the context of promotion practices refers to employee’s perceptions of fairness and transparency in promotion practices such as in the decision-making process for a job appointment (Colquitt and Rodell Citation2011). Earlier work on organisational justice draws on Social Exchange Theory (O’Connor and Crowley-Henry Citation2019). This theory especially emphasises a reciprocal relationship between employer and employee and addresses transparency as a crucial mechanism in explaining individual career behaviours. Indeed, the study of Greco et al. (Citation2015) showed that procedural injustice has a negative relationship with subjective career outcomes such as occupational satisfaction. We argue that procedural transparency and fairness of promotion practices are essential to define the boundaries within which one’s career can be shaped. It is specifically pertinent to the Dutch setting, where, contrary to the Anglo-American system, employees are appointed to senior ranks according to which positions are available at the time (van den Brink and Benschop Citation2014).

Lastly, we consider career shocks to be an antecedent of career authenticity. In the literature on unexpected events, career shocks are conceptualised as accidental events that are often caused by factors outside the focal individual’s control (Akkermans, Seibert, and Mol Citation2018). Shocks, such as a change of leadership, trigger a deliberate thought process and require an employee to make quick career-related decisions, possibly with unforeseen consequences. Studies have shown that career shocks can impact several subjective career outcomes, such as career planning (Seibert et al. Citation2013) and academic career success (Kraimer et al. Citation2019). Here, we argue that shocks may shake things up in a way that changes the work environment and career possibilities within it. For example, shocks such as experiencing scientific harassment, incite individuals to evaluate their career path by comparing their own goals against the values of the ideal ‘academic career script’ (van Helden et al. Citation2023). The valence of the implications of shocks can be understood in terms of positive or negative. Positive shocks operate as a confirmation of being ‘on the right track’, while negative shocks seem detrimental to career opportunities (Mansur and Felix Citation2020). However, career shock implications are inherently a combination between context and agency and, as such, the value of a specific shock can vary among individuals (van Helden et al. Citation2023).

Based on the above, it is hypothesised that:

There is a positive relationship between networking behaviour (H1a), managerial support (H1b), justice in promotion practices (H1c), positive career shocks (H1d) and career authenticity.

There is a negative relationship between negative career shocks (H1e) and career authenticity.

The role of gender

So far, we have outlined how five antecedents are likely to relate to career authenticity in academia in general. However, much has been written about the different experiences men and women tend to have regarding organisational practices (e.g. van den Brink and Benschop Citation2014; van Laer, Verbruggen, and Janssens Citation2019). Several theoretical perspectives underscore the need to take gender into account in research: role congruity theory, social identity theory, status characteristics theory, literature on gender stereotypes, and the kaleidoscope career model (Diehl et al. Citation2020; van Veelen and Derks Citation2021; Correll and Benard Citation2006; Meschitti and Marini Citation2023). These theoretical perspectives share (albeit partially) in their emphasis on bias as an underlying mechanism for understanding gender differences in the workplace. Gender bias entails subtle and overt discrimination or discouragement due to gender, and operates at various levels: societal, organisational, and individual (Diehl et al. Citation2020; Meschitti and Marini Citation2023), and in a self-fulfilling manner (Correll and Benard Citation2006). We follow this theoretical line of reasoning and use the notion of bias as the central mechanism for explaining gender differences regarding the role of antecedents of career authenticity. We illustrate the way gender bias operates by zooming in on one specific theory, namely status characteristics theory. We focus on this theory as it stresses the complex role of context in explaining gender differences. Status characteristics theory highlights that inequalities in the workplace arise from a cognitive bias for a certain social group based on, for example, gender (Correll and Benard Citation2006). This theory underlines that, in work and career-related decisions, high-status groups in a social setting are preferred while both supervisors and employees expect lower performance from members of lower status groups (Correll and Benard Citation2006). In the academic environment, several characteristics point to the notion that men generally belong to the high-status group. These are: a forged ideal career script around men, male dominance in academic leadership positions and gatekeeper practices which perpetuates male privilege (O’Connor et al. Citation2021; Vinkenburg Citation2017; van den Brink and Benschop Citation2014). In the male organisational academic culture, women are held to higher performance standards compared to men (Diehl et al. Citation2020) and women have less support in terms of seniors who advocate for their professional development (van Helden et al. Citation2021). Due to the higher status of men, they seem less dependent on resources and demands compared to women. The notions of ‘unequal standards’ and ‘lack of sponsorship’ among women make it plausible that resources such as networking and managerial support will be of greater value for women in enabling them to meet their personal career needs and preferences. Simultaneously, the impact of negative career shocks hits them harder than it does for men since this is a confirmation of the existing bias against women.

Based on the above, we hypothesised that:

The positive relationship between networking behaviour (H2a), managerial support (H2b), justice in promotion practices (H2c), positive career shocks (H2d) and career authenticity will be stronger for women than for men.

The negative relationship between negative career shocks (H2e) and career authenticity will be stronger for women than for men.

The role of academic rank

Aside from gender differences, we argue that the consequences of the five antecedents are also likely to differ between academic ranks. Careers depend on the quality of the resources to which academics have access. Resources are valued conditions as they help individuals achieve goals and encourage personal growth and development (Hobfoll Citation2001). Conservation of resources theory (COR) states how employees are motivated to protect their current resources and want to acquire new resources (Hobfoll Citation2001). Viewed from an accumulative perspective, it is likely that employees build and maintain various resources over time. As such, entry-level academics have fewer resources compared to mid-career academics as they have worked within the academic context a shorter amount of time. To complement conservation of resources theory, we include one of the main assumptions of the literature on career stages. This theory states that academics’ needs and expectations for their career differ between career stages (Cohen Citation1991). For example, in the early career stage, such as the postdoc rank, academics mainly focus on acquiring the skills and knowledge necessary to become an independent scientist (Sanders et al. Citation2022). At the same time, postdocs are generally engaged in a temporary period of project-based work and uncertainty is among the most prominent work-related experiences for these entry-level academics (Dorenkamp and Süß Citation2017). In contrast, in the mid-career stage, such as the associate professor rank, the emphasis on establishment and achievement is blurred by the reappraisal of the demands and goals of one’s earlier career (Sanders et al. Citation2022). Moreover, it is one of the main purposes of their tenured positions to protect these academics so that they could be free to pursue their career as they want to have it (Baruch and Hall Citation2004). Because of the non-permanent contract status of early-career academics, they are in particular need of resources to build an authentic career. Therefore, we argue that owning resources is more important for postdocs and assistant professors than for associate professors. Moreover, based on COR theory it is expected that early academics are more sensitive to the negative effects of demands than academics working in more senior positions as they have built up multiple resources to fall back on over the years compared to early academics.

Based on the above, we hypothesised that:

The positive relationship between networking behaviour (H3a), managerial support (H3b), justice in promotion practices (H3c), positive career shocks (H3d) and career authenticity will be stronger for postdocs and assistant professors than for associate professors.

The negative relationship between negative career shocks (H3e) and career authenticity will be stronger for postdocs and assistant professors than for associate professors.

Method

Sample and procedure

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the university (21-008). All academics in the target group, i.e. postdoc, assistant professors, and associate professors, of the selected university and its associated academic medical centre in the Netherlands were approached to take part in this study (N = 1525). A personalised email invitation with a link to an online survey was sent in May 2021. Academics were encouraged to participate in this study by their faculty deans. In addition, informative messages about the survey were published on several internal websites. In total, 561 individuals (36.8%) responded to the questionnaire invitation. Of these, 67 were eliminated because they did not consent (n = 3) or did not belong to the target group as the HR information was not up to date (n = 64). Of the remaining 494 individuals that qualified, 412 completed the entire questionnaire. Thus, our response rate for completion of the entire survey was 27.0%. Most of the respondents were female (56.3%, N = 232). They were slightly overrepresented in our sample as compared to the overall percentage of women among academic staff in the university of our study. A total of 13 respondents did not want to answer the question about gender, and one person chose the option ‘other’. Consequently, it was not possible to include other gender identities than men or women in the analyses due to lack of power. These cases were excluded from the multi-group analysis, and, after applying this final criterium, N = 398 participants remained in the dataset.

The average age of the respondents was 42.0 years (SD = 8.83). Men in the sample were older than women (men M = 43.58, SD = 9.48, women M = 40.89, SD = 8.16; p < .01), also in terms of academic age (men M = 11.39, SD = 8.33, women M = 9.55, SD = 7.25; p < .05). The number of participants per academic rank was approximately the same—that is, 129 postdocs, 143 assistant professors, and 126 associate professors. More than 60% of the respondents worked in the medical field. Our sample’s composition is presented in .

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N = 398).

Measures

This study’s variables are based on academics’ own perceptions. To increase the validity of our measures, we discussed the questionnaire in advance with male and female academics in different ranks and academic fields. The main goal of this was to make sure that all items were applicable to an academic context. To avoid priming effects, we first measured in our questionnaire the outcome variable career authenticity. Unless stated otherwise, we used multi-item measures, and these were formatted using five-point Likert scales (ranging from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree). All Cronbach’s alphas are above the acceptance level of .70 and are shown in . All wording in items is included in Appendix 1.

Table 2. CA, AVE and correlation matrix.

Career authenticity

Career authenticity refers to shaping the direction of one’s career according to personal needs and preferences (Shockley et al. Citation2016). This dependent variable was measured using the three-item scale of Shockley et al. (Citation2016) which is part of the Subjective Career Success Inventory scale (SCSI). These items focus on perceived self-direction (example: ‘I have felt as though I am in charge of my own career’) or perceived value orientation in a career (example: ‘I have been able to pursue work that meets my personal needs and preferences’).

Networking behaviour

Drawing on Noe (Citation1996), we included four items on networking behaviour in the survey. We specified some items by replacing general phrases with more specific ones that better fit the academic context. A sample item is ‘I have built a network of influential people within academia for obtaining information about conferences, vacancies, funding calls or other career-related activities’. In total, one item was dropped to improve the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) score.

Managerial support

In the context of career authenticity, this variable refers to whether supervisors behave in ways that help employees reach their authentic career. A sample item is ‘My supervisor informs me about opportunities for training and development’. The included supervisor support scale is based on the seminal scale of Greenhaus, Parasuraman, and Wormley (Citation1990). Inspired by Knies and colleagues (Citation2020), we included four of these nine items in our survey.

Justice in promotion practices

This variable reflects the perception of academics concerning justice in the promotion decision processes in their current university. The included scale is based on Colquitt and Rodell (Citation2011). We utilised the reworded items as applied by Kraimer et al. (Citation2019). A sample item is ‘When making decisions about working conditions that affect you, such as pay raises, promotions, research support, or teaching assignments, in your department … standards are applied consistently’. Two items were dropped to improve model fit.

Career shocks

Career shocks were measured using a scale developed by Seibert et al. (Citation2013). Respondents were asked to rate the degree to which a specific event affected their career on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1: have not experienced it to 5: had a large impact. In total, 11 career shock items were included in the survey. We extended the original scale of Seibert et al. (Citation2013) by explicitly asking for the value of each shock—positive or negative—as recent research has shown that the value of a specific shock can vary (van Helden et al. Citation2023). By asking participants to identify the value of a shock, we as researchers did not have to label the value of each shock, reducing bias in our measurement. The shock items are drawn from the select number of studies on this topic (Kraimer et al. Citation2019; Seibert et al. Citation2013). We also developed career shocks ourselves (van Helden et al. Citation2023). For example, we explicitly asked about the impact of the event ‘change of leadership’ with which we refer to a new supervisor and/or department head. In the analysis for this paper, the career shocks were narrowed down to those that were experienced most often in the work setting. We set the threshold for this at career shocks that were experienced by 15% or more of the total number of participants. We included five negative and five positive career shocks in our analysis. We calculated the average impact of these in line with Mansur and Felix (Citation2020). An overview of the descriptive information per shock is shown in Appendix 2.

Controls

In this study, we explore the impact of five antecedents for the total sample (H1), for men compared to women (H2), and across academic ranks (H3). In all three models, we control for academic field. This control is based on the assumption that academic fields vary considerably with regard to career patterns, gender representation at leadership positions and recruitment practices. Academic field was subdivided into four dummy variables: (1 = medical field; 2 = economics and business management; 3 = social sciences; and 4 = all other fields as reference category). In the general model (H1) and in the gender model (H2), we also included the control variable academic rank. It was subdivided into three dummy variables: (0 = postdoc as reference category; 1 = assistant professors; and 2 = associate professor). In the general model (H1) and in the academic rank model (H3), we included gender as a dummy variable (1 = female).

Convergent and discriminant validity

We used a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test for convergent and discriminant validity of our four latent constructs. Convergent validity is achieved under three conditions and all three were met (Hair et al. Citation2017). First, our CFA results revealed that all individual items loaded significantly on their constructs (p < .01). Second, we examined composite reliability (CR) as an indicator of the internal consistency of a construct. This score needs to be greater than .7 and, in our study, CR for the constructs ranged from .76 to .89. Third, we tested for AVE scores which are ideally greater than .50. In the present study, the four latent constructs had acceptable convergent validity ranging from .51 to .66 after one adjustment that is because the score for the variable networking behaviour was initially below .50 in the original measurement with four items. After removing item 2 (see Appendix 1), the AVE score increased to .52 and thus meets the standard. Discriminant validity was acceptable for all latent constructs.

Analyses

We applied structural equation modelling (SEM) to test our hypotheses. We followed a three-step approach using AMOS 27. The first step consisted of testing the measurement reliability and validity by performing CFA of the measurement model. In the second step, the structural model was tested. The assumption that career authenticity antecedents work differently for men compared to women and may differ between academic ranks implies a need to run the model separately for subgroups. Therefore, in step three, we applied multiple-group SEM. Multiple-group SEM analysis has the advantage that all relationships can be tested simultaneously for all subgroups while a simple moderation tests whether a variable affects the influence of the relation between one independent and dependent variable (Hair et al. Citation2017). In addition to these tests, we checked potential variation in the descriptive level of all variables.

Results

Descriptive statistics, T-tests and ANOVA analyses

On average, academics rated their career authenticity as 3.64 on a scale from 1 to 5. shows that the correlations between all five antecedents and career authenticity were statistically significant, and in line with the anticipated direction.

The independent-Samples T test results indicated there was significant variation across men and women for two antecedents: justice in promotion practices (men M = 3.13, women M = 2.89; p < .01), and negative career shocks (men M = 2.07, women M = 2.25; p < .05). While the difference in the dependent variable career authenticity is insignificant (t (396) 1.860, p = 0.06), it is noteworthy that the average score for men (M = 3.74) was higher than for women (M = 3.60).

One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) corroborated that the means of three variables differed significantly between at least two out of three academic ranks: career authenticity (F(2,395) = 4.200, p < .05), managerial support (F(2,395) = 5.428, p < .01), and positive career shocks (F(2,359) = 7.998, p < .01). Tukey HSD post hoc tests showed that associate professors had higher mean scores than postdocs on almost all these variables. These findings are in line with the rationale of the COR theory as outlined in the theoretical framework. The exception was the variable managerial support: here the postdoc group scored higher mean scores than the associate professors. shows the descriptive statistics of all antecedents and per group.

Table 3. Means for model variables per gender and academic rank.

The measurement model

The overall model fit was assessed using several fit indices. The initial structural equation model resulted in a good fit (CMIN/DF = 1.860, GFI = .936, AGFI = .912, CFI = .965 and RMSEA = .047 (90% CI .038–.055)). One of the antecedents, managerial support, did not have a significant effect on career authenticity. However, the revised measurement model in which this variable was dropped provided a slightly worse model fit (CMIN/DF = 2.202, GFI = .942, AGFI = .913, CFI = .958 and RMSEA = .055 (90% CI .044–.066)). In view of the multigroup analysis, it was decided to keep this variable in the model. The next step in the analysis was to examine the control variables. All control variables did not have a significant influence. Therefore, they were dropped from the final model to avoid unnecessary decline in statistical power.

First, we tested the direct relationship between all five antecedents and career authenticity for the total sample (H1). The antecedents accounted for 33.5% of the variance of career authenticity. Networking was positively related to career authenticity (β 0.185, p < .01), supporting Hypothesis 1a. Justice in promotion practices showed direct effects on career authenticity (β 0.369, p < .01). Contrary to our expectations, however, managerial support showed no statistically significant association with authenticity. Therefore, Hypothesis 1b is supported while Hypothesis 1c must be rejected. Hypothesis 1d and 1e examined the relationship between career shocks and career authenticity. Positive career shocks showed a statistically significant association with academic career authenticity in the anticipated direction (β 0.235, p < .01). Furthermore, the results indicated that a greater impact of negative shocks does indeed lower career authenticity (β −.180, p < 0.01). Hypotheses 1d and 1e are therefore supported.

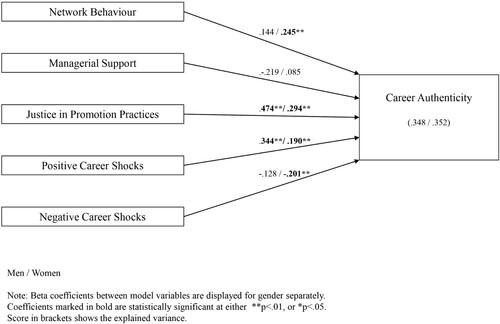

Gender

To test whether the effects of the antecedents differ among men and women (H2), we ran the models for males and females separately via multigroup SEM. In the male sample, all five antecedents accounted for 34.8% of the variance. Among female academics, these antecedents accounted for 35.2% of the variance. As shown in , some of the standardised effect sizes of the regression coefficients differed between men and women.

Networking increased career authenticity for women (β 0.245, p < .01). This association was not found for men, supporting Hypothesis 2a. For managerial support (H2b), no statistically significant association was found with authenticity for either men or women. Justice in promotion practices seemed to be a stronger antecedent of career authenticity for men (β 0.474 p < .01) compared to women (β 0.294, p < .01). This result goes in the opposite direction to what was expected in Hypothesis 2c. Also contrary to expectations, our data reveals that for men, career authenticity is enhanced by positive career shocks (H2d) (β .344, p < .01) to a greater degree than for women (β .190, p < 0.01). As expected, negative career shocks seem particularly important for women (β −.201, p < 0.05) while this association did not reach statistical significance for men, supporting hypothesis 2e.

The model fit values were CMIN/DF = 1.500, GFI = .903, AGFI = .867, CFI = .959 and RMSEA = .036 (90% CI .028–.042) which resonates good model fit. The entire model did not differ significantly between men and women (χ2 = 21.266 (18), p = .266).

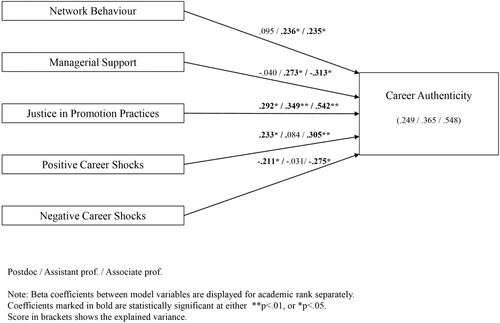

Academic rank

For the third hypothesis, we ran the model separately for all academic ranks included in this study. In the postdoc sample, the antecedents accounted for 24.9% of the variance. Among assistant professors, these antecedents accounted for 36.5% of the variance, while in the associate professor sample, the antecedents accounted for 54.8%. As shown in , most of the standardised effect sizes of the regression coefficients differed between postdocs, assistant professors, and associate professors.

Networking increased career authenticity for assistant professors (β .236, p < .05) and associate professors (β .235, p < .05) while this association did not reach statistical significance for postdocs. Hypothesis 3a must therefore be rejected. Hypothesis 3b looks at the influence of managerial support. This influence was significant for assistant professors in the anticipated direction (β .273, p < .05) while this influence is also significant for associate professors (β −.313, p < .05) but not in the direction hypothesised. This association did not reach statistical significance for postdocs. Our empirical analysis confirmed that more positive experiences with justice in promotion policy practices (H3c) boost career authenticity in all three subsamples. This organisational antecedent seems, however, particularly important for associate professors (β .542, p < .01). Hypothesis 3d examined the positive influence of positive career shocks. Our results show that this is indeed the case for postdocs (β .233, p < .05) and associate professors (β .305, p < .01). This pattern also applies to the impact of negative shocks (H3e): for both postdocs (β −.211p < .05) and associate professors (β −.275 p < .05) we found that a greater perceived impact of negative shocks lowers career authenticity. Career shocks play no role in boosting career authenticity for assistant professors. All in all, it appears that the antecedents are not more important for postdocs and assistant professors compared to associate professors. These findings are not in line with what was expected in hypothesis 3.

The fit of the measurement model was reasonable (CMIN/DF = 1.556, GFI = .859, AGFI = .806, CFI = .934 and RMSEA = .038 (90% CI .032 - .043)). The model did differ significantly between the three academic positions (χ2 = 72.883 (36), p < 0.01).

Discussion

We set out with the research question: ‘What is the influence of individual and contextual antecedents on career authenticity in academia?’ Moreover, we aimed to study whether the influence of these antecedents on career authenticity is different between genders or academic ranks. Given the lack of empirical research on contextual antecedents of career authenticity (Cha et al. Citation2019), our first contribution is that we shed more light on these specific antecedents and, as such, partly close an important theoretical gap. We found that justice in promotion practices is the most important contextual antecedent within our framework. Moreover, both positive and negative career shocks, as well as individual networking behaviour, are influential antecedents of career authenticity. Furthermore, our findings indicate that some antecedents relate differently to career authenticity for men compared to women while most antecedents operate differently per academic rank. Contrary to our expectations, managerial support appears not to play a crucial role in the experience of being self-directed and values-driven in one’s career. As such, while HRM literature indicates that supervisor career-related support is positively related to subjective career success (Shockley et al. Citation2016; Ng and Feldman Citation2014), our data does not support this for career authenticity in academia. This finding underlines the added value of a focused operationalisation of subjective career success.

The role of gender

Alongside these general conclusions, we conclude that networking behaviour indeed determines the degree of career authenticity for women significantly only, whereas it does not matter for men. This may indicate that women are more dependent on individual efforts than men. Turning to the contextual antecedents ‘career shocks’ and ‘promotion practices’, the picture is flipped. Although we stated that shocks might shake up traditional career track patterns and especially provide women with a greater opportunity to stick with their authentic self in their career choices, the findings suggest that career shocks work affirmatively for men in particular. Also, justice in promotion practices seems to have a more positive impact on career authenticity for the ‘high-status’ group of male academics compared to the ‘low-status’ group of female academics. Our contrasting findings may in part be due to a narrowly defined standard of career success in academia (Sutherland Citation2017) that still favours men (van den Brink and Benschop Citation2014), and indicates that academic career patterns are rigid. As such, it seems reasonable that within the rigid academic career system, greater insight into promotion practices may lead to more opportunities for established groups and more legitimacy for their career tracks. One way of interpreting this finding is that since career shocks are accidental and one-off events, they do not have enough power to truly shake up traditional men-based career patterns. Furthermore, it can be the case that formal rules clash with informal practices that keep benefitting certain groups of academics.

The role of academic rank

Zooming in on the findings on academic ranks, the analysis yields one main pattern: all individual and contextual antecedents appear to be particularly important in achieving career authenticity for associate professors, and less so for postdocs and assistant professors. This pattern is contrary to our expectations. The contextual antecedent justice in promotion practices is important for all included academic ranks, however, it has especially significant effects on higher academic ranks. Our data suggest that two antecedents—among them networking behaviour—have a significant effect on career authenticity only from a certain position, namely assistant professorship. The results for networking behaviour and promotion practices are probably related to the academic context feature of competitiveness and the Dutch academic context feature of the ‘formation principle’ specifically. Many professorial procedures in the Dutch context are closed (van den Brink and Benschop Citation2014) which, in turn, may place greater demands on the extent to which one can ‘read’ career policies and opportunities in the associate career stage (Sutherland Citation2017). Additionally, in line with previous research, we state that strategic network contacts are important at higher career stages to gain insider information about, for instance, invisible requirements (van Helden et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, we point towards the findings that the relationship between both career shocks and career authenticity is significant during the postdoc and associate phase, indicating that the moderating effect of academic rank is not always gradual. This result could mean that the postdoc and associate phase both symbolise breaking points in an academic career. An additional interpretation is that academic tenure is not fully serving its purpose to protect academics regarding the effects of career shocks (Baruch and Hall Citation2004). Future research is needed to clarify this result, for example, where attention is paid to the valence, duration and implications of career shocks.

As outlined above, we found no direct relationship between managerial support and career authenticity for the total sample. Yet, for assistant professors the managerial support antecedent is relevant for boosting career authenticity. However, for associate professors, managerial support had an opposite effect, namely less career authenticity. As such, in hierarchical cultures and especially on higher positions, tight managerial support seems to reduce the level of career authenticity due to certain expected behaviours. We argue that the latter insight might be related to the competitiveness and the scarcity of financial resources within the academic context (O’Connor et al. Citation2021; Siekkinen and Ylijoki Citation2021). Our null finding may in part be due to broader contextual NPM influences (Siekkinen and Ylijoki Citation2021), that in turn may overrule or restrict the potential positive impact of managerial support. Another explanation for not finding the hypothesised effect is that the relationship between managerial support and career authenticity is moderated by the quality of the relationship between a supervisor and an employee or by the style of leadership.

Limitations and future research

Several limitations affect the results. One limitation relates to the chosen method. We relied on cross-sectional data, and this could be prone to common source bias. An appealing approach for future research is to apply longitudinal designs to unravel more detailed information about the stability of the variables, and consequences over time. The second limitation relates to the five included antecedents. To the best of our knowledge, we were one of the first studies to test individual and organisational antecedents of career authenticity in one and the same study. As promotion practices was a dominant antecedent, we encourage future research to distinguish between different types of justice in promotion practices such as distributive justice to deepen our understanding. Future research is also encouraged to focus on diversifying the modes of managerial support or the type of network contacts. The bottom line is that future research is stimulated to pay attention to a structure-sensitive understanding of career authenticity. Furthermore, while the antecedents effectively explain career authenticity among associate professors, they explain only part of the variation in career authenticity among postdocs. Investigating the role of job security and perceived job alternatives in future research might be especially fruitful here. Comparative research in multiple countries and scientific disciplines, testing the generalisability of our results, may also shed more light on the contextual role of New Public Management. Finally, we encourage future research to study the intersectional consequences of gender and academic rank. The logical next step seems to be to theorise and examine this potential three-way interaction.

Practical implications

The notion of career authenticity has been moving up in the agenda of higher education institutions, as there is substantial evidence of its positive effects both on individuals as well as organisations (Shore, Cleveland, and Sanchez Citation2018; Cha et al. Citation2019). Our results point towards two empirically substantiated recommendations on how universities can support academics in realising authentic careers. First, if department heads and supervisors aim to boost authenticity in their employees’ academic careers, our findings underline the need to critically analyse justice in promotion practices, as these practices are a key antecedent of career authenticity. We unravelled here a complex tension: the increase in visibility of promotion practices leads to more invisible inequalities in terms of career authenticity among men and women. Based on our findings, we advocate the application of systemic interventions at the organisational level focused on, for example, the operationalisation and application of promotion criteria (Vinkenburg Citation2017). The international movement towards broader recognition of, and rewards for, academic career tracks seems a promising intervention if systematic attention will be paid to the transformation of organisational structures and cultures among all stakeholders involved. Second, it is recommended that supervisors, peers, and individuals pay careful attention in terms of support in handling career shocks as shocks have profound impacts on academics’ career authenticity. Related to this second recommendation, training programmes for staff can be more broadly targeted on topics such as ‘how to cope with unexpected events’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daphne L. van Helden

Daphne L van Helden is a PhD candidate at the Department of Public Administration and Sociology at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Her research activities are directed at diversity and inclusion in higher education, with a particular interest in academic career development.

Laura den Dulk

Laura den Dulk is a professor of Public Administration in Employment, Organization and Work- Life Issues at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, Department of Public Administration and Sociology, the Netherlands. She studies the work-life interface at the individual level, the organisational level, the country level, and how the different levels interact.

Bram Steijn

Bram Steijn is a professor of Public Administration at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands. He holds the chair on human resource management in the public sector and is also vice dean and director of education at the Erasmus School of Social and Behavioral Sciences (ESSB).

Joke G. Boonstra

Joke G Boonstra is vice-chair of the executive board of the Erasmus University Medical Center and as such responsible for human resources, with a special interest in and focus on diversity and inclusion.

Meike W. Vernooij

Meike W Vernooij is a neuroradiologist, epidemiologist and professor of Population Imaging at the Departments of Radiology & Nuclear Medicine and Epidemiology at the Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Her main research line concerns the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the investigation of age-related brain changes.

References

- Akkermans, Jos, Scott E. Seibert, and Stefan T. Mol. 2018. “Tales of the Unexpected: Integrating Career Shocks in the Contemporary Careers Literature.” SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 44: 1–10. doi:10.4102/sajip.v44i0.1503.

- Baruch, Yehuda, and Douglas T. Hall. 2004. “The Academic Career: A Model for Future Careers in Other Sectors?” Journal of Vocational Behavior 64 (2): 241–262. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2002.11.002.

- Bloch, Roland, Jakob Hartl, Catherine O’Connell, and Cathal O’Siochru. 2022. “English and German Academics’ Perspectives on Metrics in Higher Education: Evaluating Dimensions of Fairness and Organisational Justice.” Higher Education 83 (4): 765–785. doi:10.1007/s10734-021-00703-w.

- Brink, Marieke van den, and Yvonne Benschop. 2014. “Gender in Academic Networking: The Role of Gatekeepers in Professorial Recruitment.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (3): 460–492. doi:10.1111/joms.12060.

- Briscoe, Jon P., and Douglas T. Hall. 2006. “The Interplay of Boundaryless and Protean Careers: Combinations and Implications.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 69 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.002.

- Cha, Sandra E., Patricia Faison Hewlin, Laura Morgan Roberts, Brooke R. Buckman, Hannes Leroy, Erica L. Steckler, Kathryn Ostermeier, and Danielle Cooper. 2019. “Being Your True Self at Work: Integrating the Fragmented Research on Authenticity in Organizations.” Academy of Management Annals 13 (2): 633–671. doi:10.5465/annals.2016.0108.

- Cohen, Aaron. 1991. “Career Stage as a Moderator of the Relationships Between Organizational Commitment and Its Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Occupational Psychology 64 (3): 253–268. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1991.tb00558.x.

- Colquitt, Jason A., and Jessica B. Rodell. 2011. “Justice, Trust, and Trustworthiness: A Longitudinal Analysis Integrating Three Theoretical Perspectives.” Academy of Management Journal 54 (6): 1183–1206. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.0572.

- Correll, Shelley J., and Stephen Benard. 2006. “Biased Estimators? Comparing Status and Statistical Theories of Gender Discrimination.” Advances in Group Processes 23 (6): 89–116. doi:10.1016/S0882-6145(06)23004-2.

- Diehl, Amy B., Amber L. Stephenson, Leanne M. Dzubinski, and David C. Wang. 2020. “Measuring the Invisible: Development and Multi-Industry Validation of the Gender Bias Scale for Women Leaders.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 31 (3): 249–280. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21389.

- Dorenkamp, Isabelle, and Stefan Süß. 2017. “Work-Life Conflict among Young Academics: Antecedents and Gender Effects.” European Journal of Higher Education 7 (4): 402–423. doi:10.1080/21568235.2017.1304824.

- Forret, Monica L., and Thomas W. Dougherty. 2004. “Networking Behaviors and Career Outcomes: Differences for Men and Women?” Journal of Organizational Behavior 25 (3): 419–437. doi:10.1002/job.253.

- Greco, Lindsey M, M. Kraimer, S. Seibert, and Leisa D Sargent. 2015. “Career Shocks, Obstacles, and Professional Identification Among Academics.” Academy of Management Proceedings, doi:10.5465/ambpp.2015.12178abstract.

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H, Saroj Parasuraman, and Wayne M Wormley. 1990. “Effects of Race on Organizational Experiences, Job Performance Evaluations, and Career Outcomes.” Academy of Management Journal 33 (1): 64–86.

- Hair, J. F., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 165. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Helden, Daphne L van, Laura den Dulk, Bram Steijn, and Meike W Vernooij. 2021. “Gender, Networks and Academic Leadership: A Systematic Review.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 174114322110341. doi:10.1177/17411432211034172.

- Helden, Daphne Lisanne van, Laura den Dulk, Bram Steijn, and Meike Willemijn Vernooij. 2023. ‘Career Implications of Career Shocks Through the Lens of Gender: The Role of the Academic Career Script’. Career Development International 28 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1108/CDI-09-2022-0266.

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2001. “The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory.” Applied Psychology 50 (3): 337–421. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00062.

- Knies, Eva, Peter Leisink, and Rens van de Schoot. 2020. “People Management: Developing and Testing a Measurement Scale.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 31 (6): 705–737. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1375963.

- Kraimer, Maria L., Lindsey Greco, Scott E. Seibert, and Leisa D. Sargent. 2019. “An Investigation of Academic Career Success: The New Tempo of Academic Life.” Academy of Management Learning and Education 18 (2): 128–152. doi:10.5465/amle.2017.0391.

- Laer, Koen van, Marijke Verbruggen, and Maddy Janssens. 2019. “Understanding and Addressing Unequal Career Opportunities in the “New Career” Era: An Analysis of the Role of Structural Career Boundaries and Organizational Career Management.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, doi:10.1080/09585192.2019.1660700.

- Mansur, Juliana, and Bruno Felix. 2020. “On Lemons and Lemonade: The Effect of Positive and Negative Career Shocks on Thriving.” Career Development International 26 (4): 495–513. doi:10.1108/CDI-12-2018-0300.

- Meschitti, Viviana, and Giulio Marini. 2023. “The Balance Between Status Quo and Change When Minorities Try to Access Top Ranks: A Tale About Women Achieving Professorship.” Gender in Management 38 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1108/GM-04-2022-0141.

- Ng, Thomas W.H., and Daniel C. Feldman. 2014. “Subjective Career Success: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 85 (2): 169–179. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2014.06.001.

- Noe, Raymond A. 1996. “Is Career Management Related to Employee Development and Performance?” Journal of Organizational Behavior 17 (2): 119–133. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199603)17:2<119::AID-JOB736>3.0.CO;2-O.

- O’Connor, Edward P., and Marian Crowley-Henry. 2019. “Exploring the Relationship Between Exclusive Talent Management, Perceived Organizational Justice and Employee Engagement: Bridging the Literature.” Journal of Business Ethics 156 (4): 903–917. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3543-1.

- O’Connor, Pat, Margaret Hodgins, Dorian R Woods, Elisa Wallwaey, Rachel Palmen, Marieke van den Brink, and Evanthia Kalpazidou Schmidt. 2021. “Organisational Characteristics That Facilitate Gender-Based Violence and Harassment in Higher Education?” Administrative Sciences 11 (4): 1–13. doi:10.3390/admsci11040138.

- Purcell, John, and Sue Hutchinson. 2007. “Front-Line Managers as Agents in the HRM-Performance Causal Chain: Theory, Analysis and Evidence.” Human Resource Management Journal 17 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.2007.00022.x.

- Salancik, Gerald R, and J. Pfeffer. 1978. “A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design.” Administrative Science Quarterly 23 (2): 224–253.

- Sanders, Karin, Maria L. Kraimer, Lindsey Greco, Frederick P. Morgeson, Pawan S. Budhwar, Jian Min James Sun, Helen Shipton, and Xiaoli Sang. 2022. “Why Academics Attend Conferences? An Extended Career Self-Management Framework.” Human Resource Management Review 32 (1): 100793. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2020.100793.

- Seibert, Scott E., Maria L. Kraimer, Brooks C. Holtom, and Abigail J. Pierotti. 2013. ‘Even the Best Laid Plans Sometimes Go Askew: Career Self-Management Processes Career Shocks, and the Decision to Pursue Graduate Education’. Journal of Applied Psychology 98 (1): 169–182. doi:10.1037/a0030882.

- Shockley, Kristen M., Heather Ureksoy, Ozgun Burcu Rodopman, Laura F. Poteat, and Timothy Ryan Dullaghan. 2016. “Development of a New Scale to Measure Subjective Career Success: A Mixed-Methods Study.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 37 (1): 128–153. doi:10.1002/job.2046.

- Shore, Lynn M., Jeanette N. Cleveland, and Diana Sanchez. 2018. “Inclusive Workplaces: A Review and Model.” Human Resource Management Review 28 (2): 176–189. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.07.003.

- Siekkinen, Taru, and Oili Helena Ylijoki. 2021. “Visibilities and Invisibilities in Academic Work and Career Building.” European Journal of Higher Education 12 (4): 351–355. doi:10.1080/21568235.2021.2000460.

- Stanley, Christine A., Karan L. Watson, Jennifer M. Reyes, and Kay S. Varela. 2018. “Organizational Change and the Chief Diversity Officer: A Case Study of Institutionalizing a Diversity Plan.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 12 (3): 255–265. doi:10.1037/dhe0000099.

- Sutherland, Kathryn A. 2017. “Constructions of Success in Academia: An Early Career Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (4): 743–759. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1072150.

- Veelen, Ruth van, and Belle Derks. 2021. “Academics as Superheroes: Female Academics’ Lack of Fit with the Agentic Stereotype of Success Limits Their Career Advancement.” British Journal of Social Psychology 61 (3): 748–767. doi:10.1111/bjso.12515.

- Vinkenburg, Claartje J. 2017. “Engaging Gatekeepers, Optimizing Decision Making, and Mitigating Bias: Design Specifications for Systemic Diversity Interventions.” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 53 (2): 212–234. doi:10.1177/0021886317703292.