ABSTRACT

Higher education institutions are struggling to elevate the value and status of academic teaching. In this endeavour, rewards for excellence in teaching are becoming a common measure. This study reports on the experience of the first academic teachers who were given the status as rewarded teachers in new reward systems. We explore rewarded teachers’ potential to influence teaching and learning culture through a socio-cultural perspective, where influence is assumed to materialise through teachers’ networks and cultural change is linked to a widening of significant networks. Interviews with 13 rewarded teachers from three universities were analysed using thematic analysis. We find that rewarded teachers maintain their positions in existing networks and gain visibility and influence in wider networks. This widening of their teaching and learning network is a first step, that over time can become a wider significant network potentially important in influencing culture. We suggest that a productive measure to support rewarded teachers is to provide support for expanding their significant networks further, bridging the boundaries between teaching cultures. This study adds to our knowledge about how reward impacts networks, and the potential role rewarded teachers play in cultural change, a perspective that is underexplored in research on reward systems.

Introduction

Higher education institutions are struggling to elevate the value and status of academic teaching. In this endeavour, rewards and recognition for excellence in teaching are becoming common. Types of reward range from fellowships, prizes and titles, to schemes integrated in institutional or national systems for quality improvement, promotion and appointment. Teaching reward systems typically share some overarching objectives, namely enhancing student learning and educational quality, giving individual academic teachers recognition for a scholarly teaching practice, and strengthening the status of teaching in higher education (Chalmers Citation2011; Olsson and Roxå Citation2013; Turner et al. Citation2013; Fung and Gordon Citation2016; Winka Citation2017).

Reward systems for excellence in teaching, also called pedagogical merit or reward systems, are widespread and well-established in Swedish higher education, existing for more than 20 years (Winka and Ryegård Citation2021). The Swedish model has further inspired schemes for assessing pedagogical competence and rewarding excellence across the Nordic countries (Grepperud et al. Citation2016; Førland et al. Citation2017; Pyörälä, Korsberg, and Peltonen Citation2021; Winka and Ryegård Citation2021). What has now become a Nordic model typically involves institutional systems that target experienced and accomplished academic teachers. The assessment criteria build on the principles of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) (Boyer Citation1990; Felten Citation2013), focusing on student learning and a scholarly teaching practice with systematic, evidence-based and documented development of teaching and learning. In the Nordic systems, academic teachers apply for recognition with reflective teaching portfolios that are assessed against set criteria in a peer review process, and successful applicants are given a status (e.g. Excellent teaching practitioner), often accompanied with financial incentives. One characteristic of the Nordic reward systems is an explicit or implicit aim of changing the institutional teaching and learning culture, towards an evidence-based scholarly teaching practice and collegial culture that will benefit not only the rewarded individuals but the entire organisation (Olsson and Roxå Citation2013; Olsson et al. Citation2018).

In Norway, the very first pedagogical reward systems were established in 2016 at three universities. The following year, the White Paper A culture for quality in Higher Education introduced a governmental policy for systemic quality development in higher education (KD Citation2017), which required all higher education institutions to develop pedagogical reward systems to stimulate quality in teaching and reward educational development (KD Citation2017, 22). Norwegian institutions have since implemented reward systems, resulting in similar but local institutional policies, largely inspired by the Swedish systems. Even though these systems reward individual academic teachers, an additional purpose is to contribute to a cultural shift towards a scholarly and collegial approach to teaching as defined by the criteria for reward (Grepperud et al. Citation2016; Førland et al. Citation2017; Sandvoll, Winka, and Allern Citation2018; Olsson et al. Citation2018). An expectation is that rewarded teachers in some way will contribute to this cultural shift, by e.g. engaging in educational development and by serving as role-models, mentors and inspiring others.

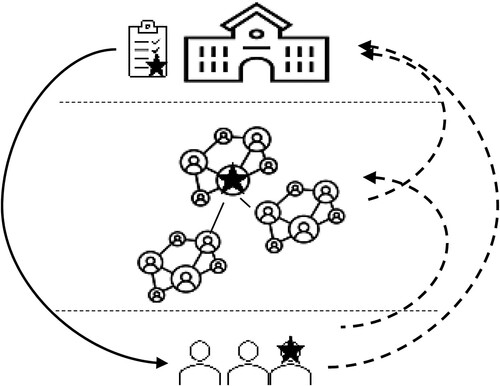

The potential for change therefore depends not only on the system itself, but also on the rewarded individuals – in particular, as will be argued below, the very first academic teachers to apply. Understanding how rewarded teachers experience becoming and being a rewarded teacher and how they potentially influence teaching and learning cultures, has implications for how institutions may use reward systems to support quality enhancement. This study reports on the experience of the first academic teachers who were given the status as rewarded teachers in three new institutional teaching reward systems in Norway. We also explore rewarded teachers’ potential to influence teaching and learning culture. To pursue this, we use a socio-cultural perspective, where influence on culture is assumed to materialise through rewarded teachers’ networks () (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009; Roxå, Mårtensson, and Alveteg Citation2011). Thus, we pursue the following research questions:

How do academic teachers experience being the first to seek recognition and be rewarded in newly established reward system for excellence in teaching?

Can we detect early signs of rewarded teachers’ influence on teaching and learning cultures, specifically by exploring how reward impacted personal networks and roles?

Figure 1. The institution (macro level) introduces a teaching reward system (star) that target individual teachers (micro level) (solid arrows). These teachers are part of social networks (meso level). Reward systems that aim for a cultural change rely on the rewarded teachers to influence their colleagues through their networks (dotted arrows).

Previous research and theoretical framework

In this section, we point to previous research that has studied the impact of reward systems. Less common are studies relying on an explicit mechanism through which the impact is found to propagate. Such knowledge may be important for institutions that have established such systems.

Impact of teaching reward systems

Reports on the UK Professional Standards Framework (UK PSF) show impact on the higher education sector, institutions and individuals (Turner et al. Citation2013). This framework is used widely internationally to identify the standard of pedagogical competence and teaching practice, and it forms a basis for recognition by Fellowships (Advance-he.ac.uk Citation2011). In addition to alignment between institutions, the UK PSF has contributed to attention and acknowledgement of excellence, has provided a common language, and has led to changed practices for institutions as well as for individuals. A lack of alignment between the framework and the local cultures, subject-specific issues and institutional career paths was also identified (Turner et al. Citation2013). For academic teachers engaging in professional development leading to UK PSF Fellowships an important motivational factor was the personal recognition, along with political, strategic and pragmatic reasons (Botham Citation2018; Spowart et al. Citation2016). The recognition was perceived as acknowledgement of individual achievements and as contributing to increased credibility and status (Botham Citation2018). Fellows support colleagues’ professional development by engaging in mentorship and leadership (Botham Citation2018), and tend to emphasise the importance of outcomes for the community as well as personal professional development (Spowart et al. Citation2016).

A well-studied Nordic reward system is the Pedagogical Academy at the Faculty of Engineering (LTH), Lund University. Olsson and Roxå (Citation2008) found that academic teachers in all categories, including senior/research-focused positions, had been rewarded and that rewarded teachers later advance into leadership positions. The reward system has impacted policy (e.g. promotion criteria), which is likely to influence the behaviour of staff (Olsson and Roxå Citation2008). Looking at student course evaluations, Borell and Andersson (Citation2014) found that rewarded teachers at LTH had higher average scores, indicating that the system captures characteristics important for the students’ experience of learning. Overall, Swedish institutions with teaching reward systems report increased interest and focus on teaching and educational development (Winka and Ryegård Citation2021).

Influencing teaching and learning culture

We adhere to a definition of culture offered by Schein (Citation2004), in which culture can be observed as artefacts, for example norms, recurrent teaching practices (Trowler Citation2020), symbols (Geertz Citation1973), or tales about heroes and exemplars (Hofstede, Minkov, and Hofstede Citation2010). We acknowledge that these observable patterns are constructed and maintained during interaction where members of a culture habitually acknowledge the meaning of such cultural artefacts (Alvesson Citation2002). We argue that culture is dependent on some stability in significant interactions (Vollmer Citation2013). Thus, cultural change is linked to, among other things, change in network constellations.

In this study, influence on teaching and learning culture is assumed to materialise through rewarded teachers’ networks () (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009; Roxå, Mårtensson, and Alveteg Citation2011). Applying network theory, Roxå, Mårtensson, and Alveteg (Citation2011), analyse construction and maintenance of teaching and learning cultures. They suggest that the communication pathways through networks are important for cultural change, with a potential influence on teaching cultures:

Since the construction of meaning in a conversation is dependent on who is taking part, a way to influence culture would be to influence the communication pathways. Thereby new people can be engaged in the discussion, and new members of a network can take on the role of being a hub. If this is achieved, both the flow of information and the negotiation of meaning will be affected. (Roxå, Mårtensson, and Alveteg Citation2011)

Studies of social networks support the claim that networks and collaborative practices are important while trying to understand how behaviour spreads (Centola Citation2018).

Informal learning through interactions and conversations in significant networks is key for teachers’ professional development, and is where teachers presumably allow themselves to be influenced (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009; Pyörälä et al. Citation2015; Van Waes et al. Citation2016; Katajavuori et al. Citation2019). In significant networks, teachers share experience and develop their practice with a small number of peers, in an environment of trust and privacy (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009). Especially important for change are those relations that stretch beyond the individual’s local context (Centola Citation2015; Centola Citation2018). Thus, cultural change is linked to a widening of teachers’ significant networks which carry new insights and behaviour beyond the boundaries of the local community (Granovetter Citation1973; Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2013; Benbow and Lee Citation2019).

A study from LTH found that successful applicants (rewarded teachers) to the Pedagogical Academy had more and richer references to a diverse group of significant others in their portfolios, indicating a larger and more diverse network (Warfvinge, Roxå, and Löfgreen Citation2018). However, this study does not address whether the successful applicants’ networks were influenced after being rewarded.

Studying collaboration and interactions within the reward system Teacher’s Academy (University of Helsinki), Katajavuori et al. (Citation2019) found that applicants were highly collaborative and interacted with others for personal development, co-teaching, sharing practice and creating artefacts, as well as systematic educational development. Previous research from the same reward system found that applicants had significant ties to peers within their discipline in their significant networks, and they also put a high value on peers outside their own unit (Pyörälä et al. Citation2015). Five years after establishment of the Teacher’s Academy, rewarded teachers in general report having meaningful conversations with their local disciplinary colleagues. In addition, the Academy itself had become a Community of Practice across disciplines and campuses (Pyörälä, Korsberg, and Peltonen Citation2021). A Community of Practice is a group of people who have a shared enterprise and a shared practice that develop through a process of negotiation and reification (Wenger Citation1999). This emerging Community of Practice shows that significant relationships have developed among the rewarded teachers, adding to their significant networks within and outside of their disciplines (Pyörälä et al. Citation2015).

The above research converges on academic teachers’ significant networks as key to understand influence in higher education. However, the perspective also highlights the need for relations that reach beyond the local contexts such as disciplinary communities or departments, for behaviour to spread within a social system (Centola Citation2018). How the rewarded teachers influence peers, particularly beyond their local contexts, and possibly contribute to a cultural shift in their respective organisations is underexplored, especially in newly introduced reward systems.

As we are attempting to look for signs of a cultural shift only a short time after introduction of teaching reward systems, a perspective on culture that allows for detecting early signs of influence is needed, a perspective that does not have to ‘wait’ for a shift in cultural artefacts (Schein Citation2004). The focus on the first-generation rewarded teachers’ experiences, allows us to investigate whether these pioneers describe emerging significant networks that are wider than their local context. If so, following the mechanism described above where patterns of recurrent interactions shape a shared understanding, it can be argued that even a first generation of rewarded teachers may count as influencers of teaching cultures, even though direct impact on the culture itself cannot yet be detected.

Materials and methods

Context of the research

Three Norwegian universities introduced their institutional reward systems in 2016, before it became a national requirement, and they were thus leaders in the development of reward systems in Norway (Grepperud et al. Citation2016; Førland et al. Citation2017). The first teachers were rewarded in 2017 (a total number of 21 at three institutions). These pioneer systems have similar evaluation criteria, process, reward and status given successful applicants. The criteria are based on the principles of SoTL and include (i) a focus on student learning, (ii) a scholarly approach to teaching and learning, (iii) a clear development over time and (iv) pedagogical leadership/collegial attitude and practice. The application includes a reflective teaching portfolio in which applicants describe their teaching philosophy and practice in relation to the evaluation criteria. Applications are followed by a CV and supporting documentation. With some exceptions, permanent academic staff with teaching duties are invited to apply on a voluntary basis. A criteria-based assessment is done in a peer review process. Successful applicants are awarded a status (e.g. Merited Teacher or Excellent Teaching Practitioner), get a personal salary increase and in one of the systems also become members of a Pedagogical Academy. In two of the systems, the rewarded teacher`s department gets a financial reward.

Informants and data collection

We conducted semi-structured interviews (Kvale et al. Citation2009) with 13 academic teachers in the first generation of rewarded teachers from the three Norwegian universities that implemented the first teaching reward systems. Informants were recruited by purposeful sampling (Moser and Korstjens Citation2018) among successful applicants (21) in the first call for applications at their institutions. All successful applicants were invited to participate, and 13 accepted. They come from a range of academic disciplines, whereof half is from STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) and the rest from disciplines like language, teacher education, art and business. Our study is reported to the Norwegian centre for research data (NSD, reference number 765106) and informed consent was given by all informants.

An interview guide with open-ended questions was developed and tested in three pilot interviews. As preparation for the interviews, the informant’s teaching portfolio (application) was read by the interviewer. At the time of the interviews, the informants had held the status as rewarded teacher for 2–2.5 years. Interviews lasted one hour and were done face-to-face in the informant’s workplace. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Informants were given pseudonyms and data de-identified to ensure anonymity.

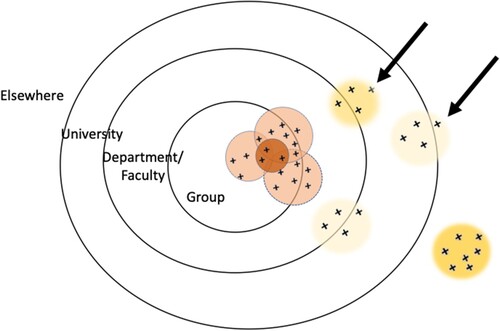

The informants were asked to describe their teaching and learning network (conversational partners and interactions) using a network map, using the last six months as the starting time frame. The network lens guided our informants to focus on interactions and communication pathways (Roxå, Mårtensson, and Alveteg Citation2011; Pataraia et al. Citation2014). The network map had concentric circles representing organisational proximity (group, department, institution and outside) and informants were asked to place conversational partners on the map and say something about the nature and frequency of interactions. They were free to add more connections to their network as the interview proceeded.

Informants were asked about the process of applying, and whether the reward itself or the role ‘rewarded teacher’ had added or removed connections from their network. As the interviews were done after receiving the status, we were especially interested in whether and how the teachers perceive any change after the reward.

Data analysis

Interviews were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), searching for themes within and across informants and identifying meaningful patterns in both common and different perspectives among participants (Nowell et al. Citation2017). The process of analysis began with the first author carefully reading transcripts and to familiarise themselves with the data, and then proceeding to create initial codes. Codes were combined into broader themes and sub-themes found across the data. Summaries of each interview were made, structured around the main themes (network, reasons to apply, support and encouragement, application process, perceived changes) and emergent themes (e.g. views on systems and criteria). The summaries were used to generate codes, carefully cross-referencing with transcripts for consistency and reliability, followed by discussions with co-researchers. Themes and sub-themes were then revised and developed into the final thematic map (). NVivo12 (QSR, released 2018) was used to store and organise data. The network analysis was done by combining the informants’ own drawings on the network map and their narrative (Altissimo Citation2016).

Table 1. Thematic map, experience of application process.

Table 2. Thematic map, perceived changes following reward.

Table 3. Thematic map, views on educational quality and reward systems.

Results

Teaching and learning networks

The local teaching and learning networks informants described () were typically long-lasting and had, in the informants’ experience, not changed much after reward. Collaboration and frequent engagement in interactions and conversations about teaching and learning were common. The informants described their networks mainly as clusters – stable groups of people within their group/department with whom they had regular interactions. Also, informants frequently had more distant and short-term connections outside their group/department within or outside their institutions. In contrast to the clusters mentioned above, these more distant and ephemeral connections increased in frequency and number after reward ().

Figure 2. Visualisation of a typical teaching and learning network. The network at the group- and department level was mainly made up of colleagues with whom the informants teach, share an interest, and/or colleagues that informants lead either formally or informally (e.g. leading course development). Among these colleagues, there was a small group of trusted individuals (significant network, dark circle). At the Faculty/University level, networks had a more formal and task-driven character (e.g. committees and working groups), or were more casual connections motivated by similar interests. Outside the institution, there was a research network where teaching and learning conversations also occur. Changes (black arrows) in networks after the reward happened most frequently outside group/department related to formal tasks or new roles.

Becoming a rewarded teacher – reasons to apply and experience of process

All the informants had a long-standing commitment to teaching and appreciated the chance to be recognised for their efforts. Overall, they identified themselves with the criteria and the values reflected in them, and they described teaching practices and attitudes aligned with these criteria. Although many found the criteria vague, they did attach meaning to them that reflected their individual values and practice.

I knew immediately when I saw the criteria that I could apply. It was like the sum of many things I have spent much time on and reflected on. And finally, someone see it (…) The things I find important are valuable. (Kim)

It was quite nice for me to go: ‘am I doing stuff at that standard?’ (…) if there is a movement within [the institution] to promote teaching and excellence (…), then I want to be part of it. But there hasn’t been … (Sam)

Being a rewarded teacher could give me authority. It will not last very long, but I did think what I would use it for. (Jaime)

This is a good way of finding a network or finding a way into it – or even promoting good teaching practice and communication about it. (Sam)

There was a financial incentive and I think that is really important, so that did make a difference. But the most important thing is the principle. That a reward system exists … (Taylor).

Finally, a formal scheme to recognize excellence in teaching … So, you must apply, right? (Robin)

It is important that our department has a reputation for excellent teaching. (Taylor)

The main reason why this [system] is good, is how happy it makes you when you evaluate and present yourself. (…) I wish everyone had the opportunity to make a teaching portfolio. You get this holistic view. (Kim)

It was a very interesting process for me. First, I just wanted to show them. Defend my program. But then along the process, I realized that I had done all this. This isn’t bad at all. It was amazing really. (Jody)

… does it mean that you become known as an excellent teacher, but not an excellent researcher? We all know what is important. (Jaime)

Did I really want to do it? I feared it would lead to more work. (Sasha)

There is of course a possibility to fail. (…) it would be a bit unfortunate (…) (Robin)

This process is quite personal. I did not share it. In contrast to other applications you write, this is so personal. It is about me. (Charlie)

I do not want to seem self-satisfied. Be better than others. (Reese)

In sum, the experience of applying is multifaceted (). It is risky, but also rewarding and meaningful. The reward is personal, as it entails exploring years of a practice, but also strategic as it defends teaching as a practice where applicants assume some responsibility for this new organisational feature.

Being a rewarded teacher – perceived changes and implications

None of the informants feel that the status had led to any major changes in interactions or status within their group or department. Among the closest colleagues, there were stable relationships and established ways to interact.

They [the group] have been along for the ride and seen this from all sides all along, so it doesn´t matter. Outside it means a lot more I think, than locally. (Charlie)

New connections arose due to increased attention, authority and opportunities for involvement. The rewarded teachers contributed to various processes and initiatives and assumed new formal or informal roles. They used the attention and opportunities in different ways, from drawing attention to certain issues, to initiating development or taking on formal responsibilities. However, they did not flag their status unless the situation required them to.

Typical new roles were mentoring and assessing peers for promotion or teaching rewards at their own or other institutions. Some were recruited to be spokespersons, sharing knowledge about the reward system and their own experience. Another common role was that of ‘expert teacher’ in various institutional processes related to educational quality, professional and teaching development.

I have been given mentoring responsibilities (…). That is a direct consequence of the status. At the department I often get asked for advice (…) like an informal pedagogical advisor for leadership. (Ali)

Quite a few people have asked me about things, but it is not a formal supervisory role. But I do mentor people that are developing their teaching portfolios … (Reese)

I said yes to be in a Steering Group assessing applicants for reward (…) that is a consequence [of the status]. (Robin)

… well, I was an excellent teacher before I got the status Excellent teacher … (Jaime)

I am taken more seriously when we talk about teaching and learning (…) I sort of have more authority when I speak on those issues. (Ali)

The big difference now – compared to before – is that now they actually listen to me. Before, when I talked about things (…), nobody listened. (Kim)

Not that the institution uses me, exactly. But they listen to me. (Jody)

In my more cynical moments, I think it is a box ticking exercise. (…) At the university and faculty level … nothing much came of it. I genuinely don’t think the motivation is there. (Sam)

I think it is unclear what we are supposed to do, and what is expected from us. (Sasha)

I am very critical of the fact that the university flags that there is a strategy to improve educational quality, but do not follow up with strategic measures. (Jaime)

It is meaningless to use the status at the department when it isn’t recognized by the most important leader. I think that is sad … . (Taylor)

I have felt the expectations. I have the status, and now I should change the department. But the department does not want to be changed. (Andy)

Views on the wider importance of the system and educational quality

A recurring emergent theme from the interviews was the informants’ views and reflections on teaching reward systems (). They experience that the reward system and the associated criteria represented a new ways of describing and assessing educational quality and excellence in teaching.

Many thought it was about excellent teacher – like, excellent lecturer. But people understand when they read the criteria (…) It is not enough to say what you have done, you must document and reflect. It is not about only highlighting the excellent things you do but seeing the potential for improvement – why something happened and what you want to work on improving. That being rewarded is not about having arrived, but about being in a process where you develop teaching and quality all the time. (Reese)

It is useful for those that are new teachers (…) it gives them a compass in a way. One that is better than the one we had. (Charlie)

[the institution] have emphasized that this is not a charisma test. It is not a student satisfaction reward, which is easy to game (…) you must have taken some type of leadership and initiative – been a teacher that develops something. Something that is about the whole. (Taylor)

One of the good things with this scheme is that leadership now must learn all these concepts [in the criteria] and try to understand them. They have not had that understanding of quality that lies within this system (…) so it is educating the leadership in many institutions. (Charlie)

Discussion

Our informants provided rich descriptions of their experience as pioneers in seeking recognition and being rewarded in newly established reward systems for excellence in teaching. They felt encouraged and positively challenged by this system and valued the existence of such a system. The process was both personal and strategic, and informants were motivated by both personal (i.e. recognition) and professional (e.g. opportunity and influence) goals to engage with the reward system. After receiving the status as rewarded teacher, informants described how they gained authority and legitimacy in matters of teaching and learning. They gained visibility and became known as someone who had succeeded in this new system for recognition and reward. The informants also expressed a concern about unclear expectations, and some even expressed disappointment. These feelings seemed to originate from a perceived lack of support, strategy or plans from the institution beyond establishing a reward system and appointing rewarded teachers. A possible interpretation of this is that even though the rewarded systems were introduced as a top-down initiatives, they allowed the applicants to invest their varied personal experiences while responding to the criteria. Through this process, the teachers’ lived experiences (Jay Citation2006) formed the flesh and blood of the system. The criteria express the institutions’ view of what constitutes quality and excellence in teaching, namely a scholarly and collegial practice and approach that systematically develops teaching to enhance student learning – and can thus be seen as an indirect definition of pedagogical competence (Winka and Ryegård Citation2021). Being first gives a certain power to define the criteria, and influence how the reward system, and in turn educational quality and pedagogical competence, are understood by colleagues and leaders.

The perceived misalignment of expectations from rewarded teachers to institutions, and from institutions to rewarded teachers, also surfaced in evaluations of reward systems in Sweden and Norway. These evaluations found that rewarded teachers expect to be ‘used’ by their institutions (Geschwind and Edström Citation2020; Raaheim et al. Citation2020; Stensaker et al. Citation2021). Few institutions meet such an expectation in a systematic way, which can be interpreted as lack a strategy on the institutions part on how the reward system and the rewarded teachers could contribute to the institutions educational quality work. On the other hand, many of the rewarded teachers in our study have formal or informal responsibilities and roles after the reward, and through their roles, and increased visibility and authority they influence their institutions on matters of teaching and learning. More formal measures to use rewarded teachers or pre-defined roles might challenge a productive balance between a top-down system and academic teachers’ lived experiences. Recent evaluation reports from two of the institutions included in this study conclude that reward systems seem to be successful in rewarding and acknowledging excellent teaching practitioners, and less successful influencing culture and educational quality. They call for a stronger institutional commitment, and measures to use the competence of rewarded teachers more systematically in the institutions’ work to enhance educational quality (Raaheim et al. Citation2020; Stensaker et al. Citation2021).

Here, we would like to return to one initial aim expressed in these reward systems: to influence teaching cultures within higher education towards a scholarly and collegial approach to teaching and learning. In our second research question, we ask whether it is possible to detect signs of cultural influence after only a few years. We argued that this requires a specific perspective on cultural influence, which we adopted from network research in higher education and wider contexts. Through this perspective academic teachers allow themselves to be influenced through often local networks of significant others (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009). Teachers’ professional development often includes widening patterns of personal networks (Van Waes et al. Citation2016; Pyörälä, Korsberg, and Peltonen Citation2021) and changes of behaviour in social systems are linked to wider networks of significant others (Centola Citation2018).

The informants reported few changes in local networks of significant others but described how new connections are being created in their wider networks (). They reported how the reward increased their visibility and authority, and led to new connections which added to what in most cases was an existing large and diverse teaching and learning network. We argue that in relation to cultural influence, the informants report early signs of what in previous research has been linked to cultural change (Roxå, Mårtensson, and Alveteg Citation2011; Centola Citation2018). We also argue that detection of such early signs is difficult unless one applies a distinct perspective on cultural influence. This in turn can potentially explain why some early evaluative reports have not found a clear influence on culture (e.g. Raaheim et al. Citation2020; Stensaker et al. Citation2021).

We see that our informants have been known for engagement and passion for teaching within their existing local significant networks over time. The new connections and opportunities expanded their network and increased interactions, and these are to a large extent seen as productive and meaningful. This widening of their teaching and learning network is a first step and could over time become a wider significant network that is important in influencing cultural change.

Therefore, we conclude that a productive measure to support rewarded teachers and thereby potentially strengthen the cultural influence, is to provide support for expanding their significant networks further and thereby bridging the boundaries between teaching cultures. This could counter the tendencies that teaching cultures become isolated silos within the organisation and allow the scholarly and passionate teachers that are being rewarded to continue what they have already done locally: influencing colleagues through significant relationships. Finally, we emphasise that influencing teaching and learning cultures in higher education is a complex and difficult endeavour that requires several inter-related initiatives (Roxå, Mårtensson, and Alveteg Citation2011), and rewarding scholarly teachers is but one way of contributing to a cultural shift. Interviewing the pioneers add to the knowledge about the potential of reward systems to influence teaching and learning cultures.

Limitations and future research

This study is limited to a small group of academic teachers among the first to get rewarded through institutional systems for excellence in teaching. As the number of informants were small, they were analysed independent of institutional affiliation, discipline or other characteristics. We acknowledge that their local context has influenced their experience, and this can be seen in the diverse set of experiences they describe. The purpose of this study is not to generalise, but to contribute to the understanding of reward systems through an analysis of the experience of the first rewarded teachers in newly established systems.

In this paper, we have chosen to focus on the experience of a group of academic teachers that chose to engage with new reward systems – and were successful in attaining the status as rewarded teacher. In future research, it would be valuable to widen the scope and investigate how these systems are perceived by non-successful applicants, and those that did not apply. Also, we could pursue how these systems change and challenge the current view and definition of teaching excellence and contribute to professional and quality development.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the rewarded teachers that participated in the interviews. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive feedback. This research was supported by bioCEED – Centre for Excellence in Biology Education. We thank Thomas Olsson for discussions during data analyses, and Lucas Jeno, Kristin Holtermann, Roy Andersson, Sehoya Cotner and Anja Møgelvang for valuable comments on the draft version of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Oddfrid Førland

Oddfrid Førland is a PhD student at Centre for Engineering Education, LTH, Lund University and an academic developer at bioCEED – Centre for Excellence in Biology Education, University of Bergen. Her research focuses on change in higher education and academic teaching culture and reward systems for excellence in teaching. As an academic developer, she has worked with professional development for academic teachers in STEM and curriculum development in biology and STEM.

Torgny Roxå

Torgny Roxå is an associate professor at Lund University and for 35 years, academic developer. His research is focused on strategic change in academic teaching cultures, significant networks and microcultures. He has taught at several professional development activities for Academic Developers in Sweden and internationally.

References

- Advance-he.ac.uk. 2011. “The UK Professional Standards Framework for Supporting Learning in Higher Education.” Advance HE, Guild HE, Universities UK. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/uk-professional-standards-framework-ukpsf.

- Altissimo, A. 2016. “Combining Egocentric Network Maps and Narratives: An Applied Analysis of Qualitative Network Map Interviews.” Sociological Research Online 21 (2): 14. doi:10.5153/sro.3847.

- Alvesson, M. 2002. Understanding Organizational Culture. London: SAGE Publications. doi:10.4135/9781446280072.

- Benbow, R., and C. Lee. 2019. “Teaching-Focused Social Networks Among College Faculty: Exploring Conditions for the Development of Social Capital.” Higher Education 78 (1): 67–89. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0331-5.

- Borell, J., and K. Andersson. 2014. “Effekter av LTHs pedagogikutvecklingsaktiviteter på LTH-lärarnas undervisning.” In Proceedings of LTHs 8:E Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens. Lund: Faculty of Engineering (LTH), Lund University. https://portal.research.lu.se/portal/files/5866384/4857197.

- Botham, K. A. 2018. “The Perceived Impact on Academics’ Teaching Practice of Engaging with a Higher Education Institution’s CPD Scheme.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 55 (2): 164–175. doi:10.1080/14703297.2017.1371056.

- Boyer, E. L. 1990. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate: A Special Report. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Centola, D. 2015. “The Social Origins of Networks and Diffusion.” The American Journal of Sociology 120 (5): 1295–1338. doi:10.1086/681275.

- Centola, D. 2018. How Behavior Spreads. The Science of Complex Contagions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Chalmers, D. 2011. “Progress and Challenges to the Recognition and Reward of the Scholarship of Teaching in Higher Education.” Higher Education Research and Development 30 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1080/07294360.2011.536970.

- Felten, P. 2013. “Principles of Good Practice in SoTL.” Teaching & Learning Inquiry: The ISSOTL Journal 1 (1): 121–125. doi:10.20343/teachlearninqu.1.1.121.

- Førland, O., E. Høie, V. Vandvik, and H. Walderhaug. 2017. “Rewarding Excellence in Education. Establishing a Merit System for Teaching at University.” Paper Presented at EAIR 39th Annual Forum 2017, September 3–6, Porto, Portugal.

- Fung, D., and C. Gordon. 2016. “Rewarding Educators and Education Leaders in Research Intensive Universities.” Higher Education Academy. York. Accessed June 15, 2021. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/74247/.

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (Vol. 5043, p. 470). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Geschwind, L., and K. Edström. 2020. “Utvärdering av införandet av den akademiska titeln Excellent lärare vid SLU samt den nuvarande handläggnings- och bedömningsprocessen.” Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://internt.slu.se/globalassets/mw/stod-serv/komp-karriar/akademisk-karriar/excellenta-larare/slu-excellent-larare-geschwind-edstrom-200420.pdf.

- Granovetter, M. S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469.

- Grepperud, G., H. Adolfsen, A. Bjørsnes, E. A. Blekkan, R. Lyng, I. Njølstad, O. A. Paulsen, O. K. Solbjørg, and F. Rønning. 2016. “Innsats for kvalitet. Forslag til et meritteringssystem for undervisning ved UiT Norges rktiske Universitet og NTNU.” Trondheim/Tromsø. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://result.uit.no/merittering/wp-content/uploads/sites/37/2019/09/Innsatsfor-kvalitet-Forslag-til-et-meritteringssystem-for-undervisning-ved-NTNU-og-UiT-Norgesarktiske-universitet.pdf.

- Hofstede, G., M. Minkov, and G. J. Hofstede. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Jay, M. 2006. “The Lifeworld and Lived Experience.” In A Companion to Phenomenology and Existentialism , edited by H. L. Dreyfus and M. A. Wrathall, 91–104. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Katajavuori, N., V. Virtanen, M. Ruohoniemi, H. Muukkonen, and A. Toom. 2019. “The Value of Academics’ Formal and Informal Interaction in Developing Life Science Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (4): 793–806. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1576595.

- KD (Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research). 2017. “Stortingsmelding 16 (2016-2017). Kultur for kvalitet i Høyere Utdanning.” The Norwegian Government. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-16-20162017/id2536007/.

- Kvale, S., S. Brinkmann, T. M. Anderssen, and J. Rygge. 2009. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju (2 utg., p. 344). Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

- Moser, A., and I. Korstjens. 2018. “Series: Practical Guidance to Qualitative Research. Part 3: Sampling, Data Collection and Analysis.” European Journal of General Practice 24 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091.

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Olsson, T., and T. Roxå. 2008. “Evaluating Rewards for Excellent Teaching – a Cultural Approach.” Engaging Communities, Proceedings of the 31st HERDSA Annual Conference, 261–272. Rotorua. https://www.herdsa.org.au/publications/conference-proceedings/research-and-development-higher-education-place-learning-and-70.

- Olsson, T., and T. Roxå. 2013. “Assessing and Rewarding Excellent Academic Teachers for the Benefit of an Organization.” European Journal of Higher Education 3 (1): 40–61. doi:10.1080/21568235.2013.778041.

- Olsson, T., K. Winka, O. Førland, and T. Roxå. 2018. “Implementation of Reward Systems for Excellence in University Teaching – Critical Aspects from a Nordic Perspective.” In Higher Education Close-Up 9 (HECU) 9: Abstract Book, 131–134. Cape Town. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-176255.

- Pataraia, N., I. Falconer, A. Margaryan, A. Littlejohn, and S. Fincher. 2014. “‘Who Do You Talk to About Your Teaching?’ Networking Activities among University Teachers.” Frontline Learning Research 2 (2): 4–14. doi:10.14786/FLR.V2I2.89.

- Pyörälä, E., L. Hirsto, A. Toom, L. Myyry, and S. Lindblom-Ylänne. 2015. “Significant Networks and Meaningful Conversations Observed in the First-Round Applicants for the Teachers’ Academy at a Research-Intensive University.” International Journal for Academic Development 20 (2): 150–162. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2015.1029484.

- Pyörälä, E., H. Korsberg, and L. M. Peltonen. 2021. “How Teaching Academies Promote Interdisciplinary Communities of Practice: The Helsinki Case.” Cogent Education 8 (1). doi:10.1080/2331186X.2021.1978624.

- Raaheim, A., G. Grepperud, T. Olsson, K. Winka, and A. P. Stø. 2020. “Evaluering Av NTNUs System for utdanningsfaglig merittering.” NTNU, Trondheim. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1501950/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Roxå, T., and K. Mårtensson. 2009. “Significant Conversations and Significant Networks-Exploring the Backstage of the Teaching Arena.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (5): 547–559. doi:10.1080/03075070802597200.

- Roxå, T., and K. Mårtensson. 2013. “How Effects from Teacher Training of Academic Teachers Propagate Into the Meso Level and Beyond.” In Teacher Development in Higher Education. Existing Programs, Program Impact, and Future Trend, edited by G. Pleschová and S. Eszter, 221–241. London: Routledge.

- Roxå, T., K. Mårtensson, and M. Alveteg. 2011. “Understanding and Influencing Teaching and Learning Cultures at University: A Network Approach.” Higher Education 62 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9368-9.

- Sandvoll, R., K. Winka, and M. Allern. 2018. “Merittering som vitenskapelig tilnærming til undervisning.” Uniped 41 (3): 246–258. doi:10.18261/issn.1893-8981-2018-03-06.

- Schein, E. H. 2004. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd ed., pp. XVI, 437. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Spowart, L., R. Turner, D. Shenton, and P. Kneale. 2016. “‘But I’ve Been Teaching for 20 Years … ’: Encouraging Teaching Accreditation for Experienced Staff Working in Higher Education.” International Journal for Academic Development 21 (3): 206–218. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2015.1081595.

- Stensaker, B., K. Winka, E. Petterson, H. Leth Andersen, J. F. Hatlen, O. Bjørnsdatter, A. Matveeva, and E. G. Lind. 2021. “Anerkjennelse av individuell kompetanse og organisatorisk kulturutvikling – på samme tid? Evaluering av UiTs meritteringsordning.” UiT the Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø.

- Trowler, P. 2020. Accomplishing Change in Teaching and Learning Regimes: Higher Education and the Practice Sensibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Turner, N., M. Oliver, C. Mackenna, J. Hughes, H. Smith, F. Deepwell, and L. Shrives. 2013. “Measuring the Impact of the UK Professional Standards Framework for Teaching and Supporting Learning (UKPSF).” Staff and Educational Development Association, Higher Education Academy. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/resources/UKPSF_Impact_Study_Report.pdf.

- Van Waes, S., N. M. Moolenaar, A. J. Daly, H. H. P. F. Heldens, V. Donche, P. Van Petegem, and P. Van den Bossche. 2016. “The Networked Instructor: The Quality of Networks in Different Stages of Professional Development.” Teaching and Teacher Education 59 (October): 295–308. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.022.

- Vollmer, H. 2013. The Sociology of Disruption, Disaster and Social Change: Punctuated Cooperation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Warfvinge, P., T. Roxå, and J. Löfgreen. 2018. “What Influences Teachers to Develop Their Pedagogical Practice?” In Proceedings of LTHs 10:E Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 5–7. Faculty of Engineering (LTH), Lund University. https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/21244.

- Wenger, E. 1999. Communities of Practice. Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Winka, K. 2017. “Kartläggning av Pedagogiska meriteringsmodeller vid Sveriges högskolor och universitet.” PIL-rapport 2017:2. Göteborgs universitet.

- Winka, K., and Å Ryegård. 2021. “Pedagogiska Meriteringsmodeller Vid Sveriges Universitet Och Högskolor 2021.” Universitetspedagogik och lärandestöd 2021:1, Umeå universitet.