ABSTRACT

Supervisor and research community support are among the key determinants of a positive experience for PhD candidates. Yet, empirical evidence of the individual variation in experienced social support among PhD candidates is still limited. In this study, we adopted a person-centered approach to detect distinct social support profiles and their relationship with the experiences of research engagement. We also examined how certain background variables explained belonging to a profile. The data were collected in spring 2021. Altogether, 768 PhD candidates from a Finnish university participated in the study. We detected three distinct social support profiles (High, Moderate and Low research community and supervisor support) that systematically differed from each other in terms of the levels of PhD candidates’ research engagement. Additionally, we discovered that writing a monograph, working alone (not in a group), being in latter phases of studying, and being a domestic PhD candidate, raised the odds of belonging to a profile with lower levels of support. The results from this study can be used in developing doctoral education and supervision practices.

1. Introduction

PhD candidates’ wellbeing, or lack of it, has become a central concern of doctoral education policy makers, developers, and researchers over the past decade (Beasy, Emery, and Crawford Citation2021; Juniper et al. Citation2012; Mackie and Bates Citation2019; Ryan, Baik, and Larcombe Citation2021). Prior research has shown that anxiety, stress, exhaustion, and depression are some of the negative attributes leading to a deterioration of PhD candidates’ wellbeing (Devine and Hunter Citation2017; Liu et al. Citation2019; Pappa, Elomaa, and Perälä-Littunen Citation2020; Pizuńska et al. Citation2021). For example, Levecque et al. (Citation2017) found that problems related to mental health are more common among PhD candidates than among the highly educated general population or other students in higher education. The COVID-19 pandemic has further increased the challenges (Lokhtina et al. Citation2022; Pyhältö, Tikkanen, and Anttila Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Atkinson et al. Citation2022). The focus of prior investigation has been primarily on PhD candidates’ negative mental states, while their positive mental states and factors contributing to them have so far been less studied (Pyhältö, Vekkaila, and Keskinen Citation2015; Virtanen, Taina, and Pyhältö Citation2017). Moreover, the few prior studies applying a person-centered approach have focused mainly on PhD candidates’ negative mental states, such as burnout (Peltonen et al. Citation2017; Tikkanen et al. Citation2021).

To our knowledge, the current study is among the first exploring the interrelation between supervisor and research community support and research engagement among PhD candidates by using a person-centered approach. In this paper, we approach the wellbeing challenge by exploring the interrelation between a positive mental state – the research engagement and supervisor and research community support that the PhD candidates experienced. In contrast to a variable oriented approach, the person-centered approach adopted focuses on similarities or differences between individuals or sub-groups, which makes it possible to identify qualitative differences and heterogeneity in the experiences (Meyer, Stanley, and Vandenberg Citation2013; Mäkikangas and Kinnunen Citation2016; Woo, Jebb, Tay, & Parrigon, Citation2018).

2. Supervisor and research community support and research engagement

Providing a functional supervisor relationship and integration into the research community have been shown to be among the main determinants for both PhD degree completion and the quality of the doctoral experience, including wellbeing (Cornér, Löfström, and Pyhältö Citation2017; Mantai Citation2019; Roos, Löfström, and Remmik Citation2021; van Rooij, Fokkens-Bruinsma, and Jansen Citation2021). Social support (Cobb Citation1976; House Citation1981; House and Kahn Citation1985) from the doctoral supervisor and members of the research community refers to various social resources that PhD candidates have and perceived to be available in the academia (Pyhältö Citation2018).

Supervisor and research community support may be divided into at least three different forms of social support: informational, instrumental, and emotional (Pyhältö Citation2018). Supervisor(s) and other senior members of the research community are a primary source of informational support, including feedback, affirmation, guidance, and suggestions that allow PhD candidates and early career researchers to solve problems they face (Cornér et al. Citation2018; Pyhältö, Vekkaila, and Keskinen Citation2015; Vekkaila et al. Citation2018). Prior research indicates that informational support from supervisors is often well aligned with students’ needs (Pyhältö et al. Citation2017). Emotional support refers to caring, listening, and showing interest that may foster the PhD candidates’ sense of belongingness. There is evidence that emotional support from supervisors is not received to the same extent as other forms of support (Cornér et al. Citation2018), and that the peers may act as a primary source of emotional support instead (Vekkaila et al. Citation2018). Instrumental support is related to resources (e.g. funding, materials, equipment, working spaces or time). It is not as often highlighted by the PhD candidates as emotional or informational support (Pyhältö, Vekkaila, and Keskinen Citation2015; Vekkaila et al. Citation2018). However, there is evidence that instrumental support from supervisors (e.g. providing access to certain resources) may have a positive impact on an early career researcher’s experience (Chen, McAlpine, and Amundsen Citation2015).

Supervisor(s) and other research community members, including peers, postdoctoral researchers and senior scholars provide the primary sources of social support for a PhD candidate (Pyhältö, Vekkaila, and Keskinen Citation2015; Vekkaila et al. Citation2018). They guide the research process, provide feedback, and help with practicalities related to the PhD journey. Receiving emotional and informational support has been shown to be related to satisfaction with supervision (Cornér, Löfström, and Pyhältö Citation2017). Institutional and supervisor support are also associated with higher levels of motivation, that further predicting greater study engagement (Dupont, Galand, and Nils Citation2015). Moreover, adequate amounts of supervisor and research community support are related to lower risk of discontinuing the programme (Peltonen et al. Citation2017). It has been suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to erosion of supervisor and research community support (Pyhältö, Tikkanen, and Anttila Citation2022a).

Research engagement refers to an active cognitive, emotional, and behavioural involvement in doctoral research which is characterised by experiences of vigour, dedication, and absorption in doctoral studies (Schaufeli and Bakker Citation2002; Vekkaila Citation2014). Vigour entails mental resilience and persistence when facing difficulties, and high levels of energy (Schaufeli and Bakker Citation2002) while conducting PhD research, e.g. when collecting data, writing or conducting analyses. It also involves willingness and ability to invest effort in one’s research (Vekkaila, Pyhältö, and Lonka Citation2013; Virtanen and Pyhältö Citation2012). Dedication refers to a sense of meaningfulness, significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, and pride when conducting research. Absorption is characterised by being immersed and fully focused (Schaufeli et al. Citation2002a; Schaufeli et al. Citation2002b) on one’s PhD research.

There is evidence of PhD research being an engaging experience for the candidates (Tikkanen et al. Citation2021). Prior research indicates that there is a positive relationship between PhD candidates’ wellbeing and research engagement (Pyhältö et al. Citation2012; Stubb, Pyhältö, and Lonka Citation2011). PhD candidates’ engagement is shown to vary in the doctoral work (Vekkaila, Pyhältö, and Lonka Citation2013) and across the disciplines. Previous findings comparing domestic and international PhD candidates are to some extent contradictory: there is tentative evidence that research engagement may be higher among international PhD candidates, who, compared to native ones, are often more satisfied and motivated when doing their research (Sakurai, Vekkaila, and Pyhältö Citation2017). Also, contradictory field-specific (medicine) findings exist, with no difference between international and domestic PhD candidate research engagement detected (Tikkanen et al. Citation2021).

The engagement experienced by early career researchers has been shown to be highly socially embedded (Mason Citation2012; Scaffidi and Berman Citation2011; Vekkaila et al. Citation2018). This means that it is regulated by the quality and the quantity of interactions with the research community, including the supervisor(s). There is evidence that support received from the academic community may increase engagement (Posselt Citation2018; Pyhältö et al. Citation2022). Further, it has been shown that receiving socio-emotional, informational, and instrumental support mediates also post-doctoral researchers’ engagement (Vekkaila et al. Citation2018).

3. Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to gain a better understanding of the individual variations in PhD candidates’ experiences of social support and how such experiences are related to their research engagement. We will first examine the supervisor and research community support profiles. Then, we will examine the interrelation between the profiles and their relationship with research engagement and relevant background variables (nationality, research group status, thesis form and self-reported study phase).

The following research questions were addressed:

RQ1. What supervisor and research community support profiles can be identified in PhD candidates?

RQ2. How are the support profiles related to the experiences of research engagement?

RQ3. Does nationality, research group status, thesis form or phase of PhD candidacy explain belonging to a certain supervisor and research community support profile?

4. Method

4.1 Doctoral education in the case university

Finnish universities follow a university-wide graduate school model, based on a systematic reform of doctoral education systems on the European level (Aittola Citation2017). A foreign degree that makes a student eligible for doctoral education or a Finnish second-cycle (master's or relevant) degree is a prerequisite for the application for the Finnish doctoral studies admission. A research plan, supervisory commitment, and language proficiency in either Finish, Swedish or English are required. Selections are based on previous academic success and the quality, novelty, and relevance of the research plan. In addition, different doctoral schools and programmes may have their own criteria. PhD candidates are involved in conducting research from the beginning of their studies. The doctoral studies consist of the doctoral dissertation (200 ECTs) and coursework (40 ECTs) that is based on a personal study plan. The doctoral dissertation can be completed in the form of a monograph or a series of (typically) three to five co-authored articles and a summary. The article-based dissertation is the dominant dissertation format (Stubb, Pyhältö, and Lonka Citation2011). The target time for completing a doctoral degree is four years, if studying full time. There are no tuition fees as doctoral education is publicly funded. PhD candidates fund their studying by either applying for grants from the doctoral schools within the universities or from a range of foundations, through project funding, working in university posts for PhD candidates, or working outside academia. International PhD candidates have especially reported challenges with finances and lack of research funding (Pyhältö et al. Citation2012).

The case university is a Finnish research-intensive university that has 32 doctoral programmes working under four doctoral schools. In 2020, there were more than 4500 PhD candidates at the university, and about 600 doctoral degrees were awarded.

4.2 Participants

A total of 768 PhD candidates from the case university participated in the study in spring 2021 (response rate 17%). The survey was sent to all PhD candidates (people currently pursuing a PhD) at the case university. At the time of the data collection, studying for a doctorate was conducted mainly remotely due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in students being deprived of face-to-face interactions with the supervisor(s) and the research community. The participants represented the fields of environmental, food, biological, health, humanities, social and natural sciences. 67% of those who replied were female (60% in the whole population). The most typical age of respondents was between 30 and 34 years, similarly as in the whole population (31% of the participants and 28% of the population) (see for more detailed demographic information).

Table 1. Participants.

Participation in the anonymous survey was voluntary, and no incentives were offered. A cover letter summarised the purpose of the study, participant rights, and the use and storage of the data. Also, contact details for the research group were provided. Following the guidelines of Finnish National Board on Research Integrity, the study did not require an ethics review: it did not involve participants under the age of 15 being studied without parental consent, include intervention in the physical integrity of participants, deviate from the principle of informed consent, expose participants to exceptionally strong stimuli or security risk nor risk causing long-term mental harm beyond that encountered in normal life (cf. TENK (Citation2019)).

4.3 Measures

Research data were collected with an online survey by using the modified version of Doctoral Experience Survey (Pyhältö et al. Citation2018; Pyhältö, Peltonen, and Rautio Citation2016). In this study, we used the following three scales, validated in previous studies (Pyhältö et al. Citation2017; Pyhältö, Peltonen, and Rautio Citation2016): Supervisor support scale that consisted of 10 items (α = .945), research community support scale that consisted of 7 items (α = .907), and research engagement scale that consisted of 9 items (α = .95) (Pyhältö et al. Citation2018). See Appendix 1 for the detailed list of items and descriptive statistics of the subscales. A seven-point Likert-scale was used (1 = fully disagree, 7 = fully agree) for all the scales. Nationality, research group status, thesis form and the study phase were used as background variables.

4.4 Statistical analysis

We used a person-centered approach to explore the unobserved heterogeneity within a population and identify individual variation among PhD candidates. The social support profiles were explored using Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), which is a variant of Latent Class Analysis (LCA). LPA is based on continuous instead of categorical indicator variables (Spurk et al. Citation2020; Woo et al. Citation2018). Thus, the LPA treats profile membership as an unperceived categorical variable, where its value indicates which profile an individual belongs to with a certain degree of likelihood, unlike in more traditional, non-latent clustering methods (Spurk et al. Citation2020). All the analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 8.8 (Muthén and Muthén Citation1998–2017). An MLR estimator that produces maximum likelihood estimates with standard errors and χ2test statistics that are robust to non-normality were used (Muthén and Muthén Citation1998–2017). Within-class variances were allowed to vary across classes. Supervisor support and research community support scales were used as observed mean variables in the LPA analyses.

Statistical fit indices and content criterion were applied to determine the most appropriate number of latent profiles (Ferguson et al. Citation2020) and to test the goodness-of-fit of the model. We employed the Akaike (AIC), Bayesian (BIC), and adjusted Bayesian (aBIC) information criteria, in which lower values indicate a better fit (Ferguson et al. Citation2020). The statistical accuracy of assigning people to profiles was evaluated with entropy value (overall accuracy) and latent class probabilities (accuracy of the classification for each class, separately), both varying between 0 and 1 (closer to 1 indicating higher accuracy). Additionally, we utilised the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin (VLMR) likelihood ratio test, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (aLRT), and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) to compare the models.

When testing the equality tests of differences in research engagement, and background variables across the profiles, we used auxiliary Mplus command (Muthén and Muthén Citation1998–2017). The equality of means of research engagement was analysed with a BCH procedure. To explore whether the background variables (nationality (domestic vs. international)), research group status (alone versus at least partially in a group); thesis form (monograph vs. article based) and study phase (at the beginning of, at the end of) were related to profile memberships, we used the R3STEP procedure of Mplus that performs a multinomial logistic regression and provides the odds ratios describing the effect of background variables on the likelihood of membership in each of the latent profiles compared to other profiles (McLarnon and O'Neill Citation2018).

5. Results

On average, the PhD candidates reported that they received sufficient social support from their supervisors (M = 5.4/7, SD = 1.3). This means that they felt that their supervisors were interested in their opinions, encouraged them, and treated them with respect. They also reported receiving enough support from the research community (M = 4.8/7, SD = 1.3). That is, their experience was that they were appreciated and accepted by their research community and that they were treated equally. However, there was considerable variation in the perceptions of availability of social support from various sources between the PhD candidates. On average, the PhD candidates reported moderate levels of research engagement (M = 4.8/7, SD = 1.3) meaning that they felt their doctoral research was meaningful, and they were quite inspired and enthusiastic about their research. Research engagement correlated positively with both, supervisor support, r = .39, p < .01 and research community support, r = .32, p < .01. Supervisor support and research community support were also positively correlated, r = .64, p < .01. This indicates that the PhD candidates who perceived receiving sufficient support from the supervisor also tended to receive more support from the research community as well. Moreover, the PhD candidates who received social support from supervisor and/or research community, were more likely to experience higher levels of research engagement than those who were not supported by supervisor or wider research community. See for the descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

5.1 Number and characteristics of the latent supervisor and research community support profiles found

As LPA is a model testing process, we started by identifying the model that would have theoretically and statistically the best fit. We compared five models (see Ferguson et al. (Citation2020)), and ran multiple LPAs with 1–5 classes (see for LPA models with 1–5 classes). The information criteria (AIC, BIC, aBIC) showed that adding a new latent class enhanced the model fit all the way to three classes, and LogL(df) supported this finding. We plotted the likelihood values to be able to find a bend or an ‘elbow’. The bend found in the diagram finally determined that with the three-profile solution, the model improvement gain started to decrease (Masyn Citation2013). The entropy values were close to 0.80 for all the classes tested. The VLMR, aLRT and BLRT test results indicate the fit of a model compared to a previous model, showed that most of the LPA models we tested would have been acceptable. The model with three latent profiles of the PhD candidates’ research community and supervisor support was selected as it achieved the best fit with the data: it had the best balance between subtleness of dividing the data into more classes and parsimony (fewer classes). Three consistent support profiles were found, displaying systematically either low, moderate, or high levels of research community and supervisor support. Hence, the model comprised three latent profiles of PhD candidates’ research community and supervisor support.

Table 3. LPA models with 1–5 classes.

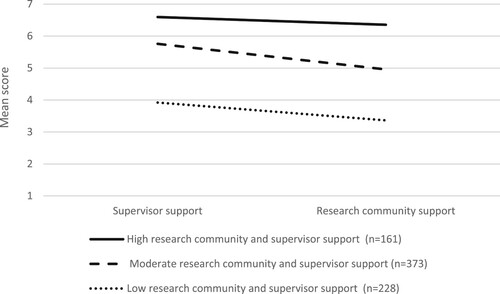

We described the biggest latent profile we detected as Moderate research community and supervisor support. It comprised 49% of the sample, n = 373. In this profile, the PhD candidates experienced moderate levels of support from both their supervisor and their research community. For example, they reported that both, the research community, and the supervisor encouraged them and appreciated their work and provided constructive feedback (see Appendix 1 for items). The second profile detected, comprising 30% of the PhD candidates (n = 228), we called Low research community and supervisor support. The PhD candidates belonging to this profile showed low levels of support from both their research community and their supervisor(s). The smallest profile detected we named High research community and supervisor support profile. In this profile, the PhD candidates displayed high levels of support from both sources, research community and the supervisor. This profile comprised 21% of the students, n = 161. The three profiles differed from each other in a statistically significant manner. It appeared that the levels of both supervisor support and research community support were on nearly the same level in the High research community and supervisor support profile, whereas in the Low and Moderate research community and supervisor support profiles, the level of research community support was lower than supervisor support. The profiles are presented in .

5.2 Supervisor and research community support profiles and research engagement

Further investigation showed that the three profiles differ from each other statistically significantly regarding research engagement. The PhD candidates reporting the High research community support and supervisor support profile, reported significantly higher levels of research engagement (M = 5.6/7) than those with Moderate research community and supervisor support profile (M = 4.9/7) or Low research community and supervisor support profile (M = 4.1/7). The results showed that the level of research engagement was higher when the level of research community and supervisor support was higher. Consistently, the level of researcher engagement was lower when the level of research community and supervisor support was lower. See for the support profiles detected and research engagement.

Table 4. Supervisor and research community support profiles and research engagement.

The findings indicated that the students in the highest support profile experience the highest levels of meaningfulness, energy, enthusiasm, inspiration, and involvement in their research. However, the PhD candidates with the lowest support profile also reported moderate levels of research engagement.

5.3 Background variables explaining belonging to a certain supervisor and research community support profile

Our analysis showed that nationality, research group status, thesis form and the phase of studies explained belonging to a certain supervisor and research community support profile.

Finnish students had higher odds of belonging to the Low research community and supervisor support profile (OR = 2.28, 95% CI, 1.20-4.36, p = 0.012), and Moderate research community and supervisor support profile (OR = 2.46, 95% CI, 1.36-4.45, p = 0.003) than High research community and supervisor support profile compared to international PhD candidates.

The students who were not engaged in research team had higher odds of receiving moderate research community and supervisor support (OR = 2,30, 95% CI, 1.36-3.87, p = 0.002) or low research community and supervisor support (OR = 4.22, 95% CI, 2.27-7.89, p = 0.000) than high research community and supervisor support compared to the PhD candidates who were working in a research group.

The students who were working on a monograph had higher odds (OR = 2,36, 95% CI, 1.01-5.51, p = 0.048) of receiving moderate research community and supervisor support than high research community and supervisor support compared to those working on a summary of articles thesis format.

Finally, the more advanced PhD candidates, i.e. those in the final stages had higher odds (OR = 2,37, 95% CI, 1.32-4.27, p = 0.004) of belonging to the Low research community and supervisor support profile than Moderate research community and supervisor support profile, compared to those in earlier phases of their doctorate. On the other hand, PhD candidates, being at the beginning (the first one-third) of their doctorate had higher odds (OR = 3.55, 95% CI, 1.17-10.78, p = 0.025) of belonging to the High research community and supervisor support than the Low research community and supervisor support profile than those in the second or final thirds of their doctoral journey.

6. Discussion

The aim of this study was to gain a better understanding of the varied individual experiences of supervisor and research community support and their interrelation with research engagement among PhD candidates. We adopted a person-centered approach to detect distinct social support profiles. We also examined how PhD candidates’ nationality, research group status, thesis form and self-reported study phase explained belonging to a certain support profile. Even if there is previous evidence that supervisor and research community support are among the key determinants for a successful doctoral journey (Cornér, Löfström, and Pyhältö Citation2017; Mantai Citation2019; Roos, Löfström, and Remmik Citation2021; van Rooij, Fokkens-Bruinsma, and Jansen Citation2021), this study provided new insight into the individual variation in PhD candidates’ social support profiles and their association with research engagement.

In the study, we detected three distinct social support profiles including High, Low and Moderate research community and supervisor support. Peltonen et al. (Citation2017) have previously identified two support profiles among PhD candidates. Our results confirm the previous findings, and complement them by detecting the third profile, i.e. Moderate research community and supervisor support profile.

Our results further showed that the research engagement was related to the research community and supervisor support profile employed. The candidates employing high levels of research community and supervisor support experienced high levels of research engagement while their less fortunate peers with lower support profiles reported lower levels of engagement. Our outcomes further confirmed the findings of prior studies, providing evidence that engagement experienced by early career researchers seems to be socially embedded (Mason Citation2012; Scaffidi and Berman Citation2011; Vekkaila et al. Citation2018). It extended prior research on PhD candidates by showing that functional research community and supervisor support does not only provide a buffer against PhD candidates’ negative mental states but is also a key for enhancing the positive ones. Yet, interrelation between the support and research engagement is likely to be reciprocal. Candidates displaying high levels of engagement are likely to make better progress and hence get more support from supervisor(s) and the scholarly community due to their commitment to the research, which further enhances their engagement. The results suggest that individual variations in the support and related research engagement occurred.

The variation in the support they experienced was related to PhD candidates’ backgrounds, study conditions and across the study phase. Firstly, Finnish PhD candidates were more likely to belong to the profiles characterised by low or moderate support from the research community and supervisor compared to their international peers. This suggests that international candidates were better supported than native Finnish ones. The findings partly contradict previous findings showing that international PhD candidates tend to get less support from the research community than the native candidates do (Pappa, Elomaa, and Perälä-Littunen Citation2020). A reason for the results might be that during the pandemic, supervisors were sensitive in recognising international candidates’ support needs (Pyhältö, Tikkanen, and Anttila Citation2022b). On the other hand, international PhD candidates often rely heavily on formal networks and events as primary sources of the support, while Finnish candidates’ support networks are more informally based. During the pandemic, formal support networks and activities were less influenced compared to informal ones since most of them were translated into online activities. Secondly, the candidates who were not engaged in a research team had a higher probability of belonging to the Low research community and supervisor support profile than High research community and supervisor support profile, compared to those who were involved in the team. This indicates that at its best, institutional structures such as a research team may enable receiving social support. Article based dissertations are more typically written in fields in which research is conducted in research teams (Pyhältö, Tikkanen, and Anttila Citation2022c). Consistently, the students who were working on a monograph (i.e. not co-writing an article-based dissertation), had higher odds to belong to Moderate research community and supervisor support than High research community and supervisor support profile. The findings are consistent with the results of prior studies implying working in a research team and writing article-based dissertation is related to higher levels of research community and supervisor support (Peltonen et al. Citation2017). Finally, PhD candidates in the last third of their programme had higher odds of belonging to the Low research community and supervisor support profile, than those in the Moderate research community and supervisor support profile, compared those at the earlier stages of their studies (the first one-third). This finding may be explained by more frequent involvement in supervision at the beginning of the doctoral journey and the candidate gradually developing their independence as a researcher towards the end of their studies.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been shown to decrease PhD candidates’ wellbeing globally (Atkinson et al. Citation2022; Lokhtina et al. Citation2022). There is evidence that especially the PhD candidates conducting their research in a group, candidates studying full-time and international candidates reported more often that the COVID-19 pandemic had reduced their study-related wellbeing (Pyhältö, Tikkanen, and Anttila Citation2022a). Yet, our results imply that the supervisory and the researcher community support both on and offline provides a mean to compensate and overcome challenges caused by the COVID-19.

7. Implications for developing doctoral education

The findings of this study are aligned with previous research showing the nexus between institutional and supervisor support and study engagement (Dupont, Galand, and Nils Citation2015) and the role of supervisor and research community support in fostering PhD candidates’ wellbeing (Cornér, Löfström, and Pyhältö Citation2017; van Rooij, Fokkens-Bruinsma, and Jansen Citation2021). The person-centered approach provided an understanding about individual variations in PhD candidates’ experiences of supervisor and research community support and how such experiences are related to research engagement. The findings indicate that in addition to cultivating PhD candidates’ degree completion and progress, supervisor and research community support cultivates the candidates study wellbeing in terms of research engagement. Hence, investing in promoting supervisor and research community support has potentially double benefits. However, our results imply that there might be variation in PhD candidates’ support needs, which must be considered when designing the support measures. In other words, to provide well-fitted support, understanding the support variation and how it is related to research engagement is important. It should be considered when designing the systemic, institutional, and structural ways to support PhD candidates during their doctoral journey.

To foster research engagement, it would be important to assess what could be done to create more optional, approachable, and supportive studying and research environments that consider the heterogeneity of the PhD candidate body. How could the higher education institutions better detect the PhD candidates at risks in terms of reduced support and thus lower research engagement? Identifying those with bigger support needs would help directing the actions accordingly. Designing structures that would enable research community support at an institutional and systemic level, focusing on systematic monitoring of the levels of social support, and investing on PhD supervisor education might cultivate optimal support experiences, and hence wellbeing of PhD candidates. To conclude, increasing the awareness of the phenomena of social support and research engagement would be important for PhD candidates, supervisors, and other stakeholders in higher education institutions. We need to be aware of the phenomena to be able to recognise and verbalise potential points of development and to strive towards processes and practices that enhance PhD researcher wellbeing.

8. Limitations of the study and future research

The following limitations should be considered. First, even if the total number of respondents in this study was satisfactory (n = 768), the overall response rate was 17%. Whilst the participants were a reasonable representation of the PhD candidate population of the case institution, it must be emphasised that the results cannot be generalised as such to the entire population from which the sample was drawn. Second, this study was cross-sectional. To understand the phenomenon examined better, and to be able to detect causalities, there is a need for a longitudinal study design in the context of higher education and doctoral education. Third, this study was carried out in one country and in a single institution. Further research is needed in a range of contexts and in different countries, to be able to generalise the results now reported. Fourth, the data were collected during a historically exceptional time of a global pandemic that forced the PhD candidates to study remotely. The results found from the data that were collected through a self-reported questionnaire could have been different if measurement had occurred at a different time. Finally, the chosen method, latent profile analysis (LPA) is explorative. Identifying the final number of profiles, even if based on statistical indicators and previous research findings, always contains a certain level of subjectivity and interpretation. Additionally, it is also worth being reminded that self-reporting is subject to several potential biases and thus, collecting information through self-reporting has its limitations. Combining self-reported data with biometric data would be interesting for future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

S. Rönkkönen

S. Rönkkönen (MA, ME) is a PhD researcher at the Doctoral Programme in Cognition, Learning, Instruction and Communication, the University of Helsinki, Finland. Her research addresses well-being in the context of higher education. Currently, she works at the Häme University of Applied Sciences, Hämeenlinna, Finland, as a ecturer at the HAMK Edu Research unit.

L. Tikkanen

L. Tikkanen (PhD) is a university lecturer at the Centre for University Teaching and Learning, University of Helsinki, Finland. Her research interests include doctoral candidates' and supervisors' well-being.

V. Virtanen

V. Virtanen (PhD) is a principal research scientist at Häme University of Applied Sciences, HAMK Edu Research Unit, Hämeenlinna, Finland. Additionally, she is an adjunct professor at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Her research interests include broadly teaching and learning Pyhältö in higher education with specific interests in well-being, and researcher education and careers. Kirsi (PhD) is a professor of higher education at the Centre for University Teaching and Learning, University of Helsinki, Finland. She is the leader of PhD Education and Careers research group.

K. Pyhältö

Dr K. Pyhältö is also an extraordinary professor at the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. Her research interests include doctoral education, doctoral supervision, research community interaction and well-being among PhD candidates, supervisors and researcher careers within and beyond academia.

References

- Aittola, Helena. 2017. “Doctoral Education Reform in Finland – Institutionalized and Individualized Doctoral Studies Within European Framework.” European Journal of Higher Education 7 (3): 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2017.1290883.

- Atkinson, Michael, Adrienne Brodie, Phillip Kafcaloudes, Sidrah McCarthy, Ebony A. Monson, Clement Sefa-Nyarko, Shauni Omond, et al. 2022. “Illuminating the Liminality of the Doctoral Journey: Precarity, Agency and COVID-19.” Higher Education Research & Development 41 (6): 1790–1804. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1968354.

- Beasy, K., S. Emery, and J. Crawford. 2021. “Drowning in the Shallows: An Australian Study of the PhD Experience of Wellbeing.” Teaching in Higher Education 26 (4): 602–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1669014.

- Chen, Shuhua, Lynn McAlpine, and Cheryl Amundsen. 2015. “Postdoctoral Positions as Preparation for Desired Careers: A Narrative Approach to Understanding Postdoctoral Experience.” Higher Education Research & Development 34 (6): 1083–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1024633.

- Cobb, S. 1976. “Social Support as a Moderator of Lide Stress.” Psychosomatic Medicine 38 (5): 300–314. doi:10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003.

- Cornér, Solveig, Erika Löfström, and Kirsi Pyhältö. 2017. “The Relationships Between Doctoral Students’ Perceptions of Supervision and Burnout.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 12: 91–106. https://doi.org/10.28945/3754.

- Cornér, S., K. Pyhältö, J. Peltonen, and S. S. E. Bengtsen. 2018. “Similar or Different?: Researcher Community and Supervisory Support Experiences among Danish and Finnish Social Sciences and Humanities PhD Students.” Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education 9 (2): 274–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-D-18-00003.

- Devine, Kay, and Karen H. Hunter. 2017. “PhD Student Emotional Exhaustion: The Role of Supportive Supervision and Self-Presentation Behaviours.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 54 (4): 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1174143.

- Dupont, S., B. Galand, and F. Nils. 2015. “The Impact of Different Sources of Social Support on Academic Performance: Intervening Factors and Mediated Pathways in the Case of Master's Thesis.” European Review of Applied Psychology 65 (5): 227–237. doi:10.1016/j.erap.2015.08.003.

- Ferguson, Sarah L., E. Whitney, G. Moore, and Darrell M. Hull. 2020. “Finding Latent Groups in Observed Data: A Primer on Latent Profile Analysis in Mplus for Applied Researchers.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 44 (5): 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419881721.

- House, James. 1981. Work Stress and Social Support. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- House, James, and Robert Kahn. 1985. “Measures and Concepts of Social Support.” In Social Support and Health, edited by Sheldon Cohen and S. Leonard Syme, 83–108. New York: Academic Press.

- Juniper, Bridget, Elaine Walsh, Alan Richardson, and Bernard Morley. 2012. “A new Approach to Evaluating the Well-Being of PhD Research Students.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37 (5): 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.555816.

- Levecque, Katia, Frederik Anseel, Alain De Beuckelaer, Johan Van der Heyden, and Lydia Gisle. 2017. “Work Organization and Mental Health Problems in PhD Students.” Research Policy 46 (4): 868–879. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.02.008.

- Liu, C., L. Wang, R. Qi, W. Wang, S. Jia, D. Shang, Y. Shao, et al. 2019. “Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression and Anxiety among Doctoral Students: The Mediating Effect of Mentoring Relationships on the Association Between Research Self-Efficacy and Depression/Anxiety.”Psychology Research and Behavior Management 12: 195–208. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S195131.

- Lokhtina, Irina A., Montserrat Castelló, Agata Agnieszka Lambrechts, Erika Löfström, Michelle K. McGinn, Isabelle Skakni, and Inge van der Weijden. 2022. “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Early Career Researcher Activity, Development, Career, and Well-Being: The State of the art.” Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education 13 (3): 245–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-10-2021-0076.

- Mackie, S. A., and G. W. Bates. 2019. “Contribution of the Doctoral Education Environment to PhD Candidates’ Mental Health Problems: A Scoping Review.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (3): 565–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1556620.

- Mäkikangas, A., and U. Kinnunen. 2016. “The Person-Oriented Approach to Burnout: A Systematic Review.” Burnout Research 3 (1): 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2015.12.002.

- Mantai, L. 2019. “'A Source of Sanity': The Role of Social Support for Doctoral Candidates’ Belonging and Becoming.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 14: 367–382. https://doi.org/10.28945/4275.

- Mason, Michelle M. 2012. “Motivation, Satisfaction, and Innate Psychological Needs.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 7 (1): 259–277. https://doi.org/10.28945/1596

- Masyn, Katherine E. 2013. “25 Latent Class Analysis and Finite Mixture Modeling.” The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods 2: 551. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199934898.013.0025.

- McLarnon, Matthew J. W., and Thomas A. O'Neill. 2018. “Extensions of Auxiliary Variable Approaches for the Investigation of Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Effects in Mixture Models.” Organizational Research Methods 21 (4): 955–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118770731.

- Meyer, J. P., L. J. Stanley, and R. J. Vandenberg. 2013. “A Person-Centered Approach to the Study of Commitment.” Human Resource Management Review 23 (2): 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2012.07.007.

- Muthén, L. K., and B. O. Muthén. 1998–2017. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Pappa, Sotiria, Mailis Elomaa, and Satu Perälä-Littunen. 2020. “Sources of Stress and Scholarly Identity: The Case of International Doctoral Students of Education in Finland.” Higher Education 80 (1): 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00473-6.

- Peltonen, Jouni, Jenna Vekkaila, Pauliina Rautio, Kaisa Haverinen, and Kirsi Pyhältö. 2017. “Doctoral Students’ Social Support Profiles and Their Relationship to Burnout, Drop-Out Intentions, and Time to Candidacy.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 12: 157–173. https://doi.org/10.28945/3792.

- Pizuńska, Daria, Paulina Beata Golińska, Agnieszka Małek, and Wioletta Radziwiłłowicz. 2021. “Well-being among PhD Candidates.” Psychiatria Polska 55 (4): 901–914. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/114121.

- Posselt, Julie. 2018. “Normalizing Struggle: Dimensions of Faculty Support for Doctoral Students and Implications for Persistence and Well-Being.” The Journal of Higher Education 89 (6): 988–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1449080.

- Pyhältö, K., M. Castello, L. McAlpine, and J. Peltonen. 2018. “The Cross-Country Doctoral Experience Survey (C-DES).” User’s Manual. Manual Version.

- Pyhältö, K., L. McAlpine, J. Peltonen, and M. Castello. 2017. “How Does Social Support Contribute to Engaging Post-PhD Experience?” European Journal of Higher Education 7 (4): 373–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2017.1348239.

- Pyhältö, Kirsi, Jouni Peltonen, Henrika Anttila, Liezel Liezel Frick, and Phillip de Jager. 2022. “Engaged and/or Burnt out? Finnish and South African Doctoral Students’ Experiences.” Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-02-2021-0013.

- Pyhältö, Kirsi, Jouni Peltonen, and Pauliina Rautio. 2016. “Summary report on doctoral experience in the UniOGS graduate school at the University of Oulu.” In. Tampere Juvenes Print Oulu: University of Oulu.

- Pyhältö, Kirsi, Lotta Tikkanen, and Henrika Anttila. 2022a. “The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on PhD Candidates’ Study Progress and Study Wellbeing.” Higher Education Research & Development, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2063816.

- Pyhältö, Kirsi, Lotta Tikkanen, and Henrika Anttila. 2022b. “Is There a fit Between PhD Candidates’ and Their Supervisors’ Perceptions on the Impact of COVID-19 on Doctoral Education?” Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-05-2022-0035.

- Pyhältö, Kirsi, Lotta Tikkanen, and Henrika Anttila. 2022c. “Summary Report on Doctoral and Supervisory Experience at the University of Helsinki.”.

- Pyhältö, Kirsi, Auli Toom, Jenni Stubb, and Kirsti Lonka. 2012. “Challenges of Becoming a Scholar: A Study of Doctoral Students’ Problems and Well-Being.” ISRN Education 2012: 1. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/934941.

- Pyhältö, Kirsi, Jenna Vekkaila, and Jenni Keskinen. 2015. “Fit Matters in the Supervisory Relationship: Doctoral Students and Supervisors Perceptions About the Supervisory Activities.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 52 (1): 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.981836.

- Pyhältö. 2018. “Function of Supervisory and Researcher Community Support in PhD and Post- PhD Trajectories.” In Studies Into Higher Education. Spaces, Journeys and new Horizons for Postgraduate Supervision, edited by Eli Bizer, Liezel Frick, Magda Fourie-Malherbe, and Kirsi Pyhältö, 205–222. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Sun Press.

- Roos, L., E. Löfström, and M. Remmik. 2021. “Individual and Structural Challenges in Doctoral Education: An Ethical Perspective.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 16: 211–236. https://doi.org/10.28945/4738.

- Ryan, T., C. Baik, and W. Larcombe. 2021. “How Can Universities Better Support the Mental Wellbeing of Higher Degree Research Students? A Study of Students’ Suggestions.” Higher Education Research & Development, https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1874886.

- Sakurai, Yusuke, Jenna Vekkaila, and Kirsi Pyhältö. 2017. “More or Less Engaged in Doctoral Studies? Domestic and International Students’ Satisfaction and Motivation for Doctoral Studies in Finland.” Research in Comparative and International Education 12 (2): 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499917711543.

- Scaffidi, A. K., and J. E. Berman. 2011. “A Positive Postdoctoral Experience is Related to Quality Supervision and Career Mentoring, Collaborations, Networking and a Nurturing Research Environment.” Higher Education 62 (6): 685–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9407-1.

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2002. “Job Demands, job Resources, and Their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 23 (5): 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248.

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Isabel M. Martínez, Alexandra Marques Pinto, Marisa Salanova, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2002a. “Burnout and Engagement in University Students.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 33 (5): 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003.

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Marisa Salanova, Vicente González-romá, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2002b. “The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach.” Journal of Happiness Studies 3 (1): 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326.

- Spurk, Daniel, Andreas Hirschi, Mo Wang, Domingo Valero, and Simone Kauffeld. 2020. “Latent Profile Analysis: A Review and “How To” Guide of Its Application Within Vocational Behavior Research.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 120), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103445.

- Stubb, J., K. Pyhältö, and K. Lonka. 2011. “Balancing Between Inspiration and Exhaustion: Phd Students’ Experienced Socio-Psychological Well-Being.” Studies in Continuing Education 33 (1): 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2010.515572.

- TENK, Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. 2019. The ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland. Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK.

- Tikkanen, Lotta, Kirsi Pyhältö, Aleksandra Bujacz, and Juha Nieminen. 2021. “Study Engagement and Burnout of the PhD Candidates in Medicine: A Person-Centered Approach.” Frontiers in Psychology 12), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.727746.

- van Rooij, E., M. Fokkens-Bruinsma, and E. Jansen. 2021. “Factors That Influence PhD Candidates’ Success: The Importance of PhD Project Characteristics.” Studies in Continuing Education 43 (1): 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2019.1652158.

- Vekkaila, Jenna. 2014. “Doctoral student engagement: The dynamic interplay between students and scholarly communities.”.

- Vekkaila, J., K. Pyhältö, and K. Lonka. 2013. “Focusing on Doctoral Students’ Experiences of Engagement in Thesis Work.” Frontline Learning Research 1 (2): 12–34. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v1i2.43.

- Vekkaila, Jenna, Viivi Virtanen, Juha Taina, and Kirsi Pyhältö. 2018. “The Function of Social Support in Engaging and Disengaging Experiences among Post PhD Researchers in STEM Disciplines.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (8): 1439–1453. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1259307.

- Virtanen, Viivi, and Kirsi Pyhältö. 2012. “What Engages Doctoral Students in Biosciences in Doctoral Studies?” Psychology (savannah, Ga ) 3 (12): 1231–1237. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312A182.

- Virtanen, V., J. Taina, and K. Pyhältö. 2017. “What Disengages Doctoral Students in the Biological and Environmental Sciences from Their Doctoral Studies?” Studies in Continuing Education 39 (1): 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2016.1250737.

- Woo, Sang Eun, Andrew T. Jebb, Louis Tay, and Scott Parrigon. 2018. “Putting the “Person” in the Center: Review and Synthesis of Person-Centered Approaches and Methods in Organizational Science.” Organizational Research Methods 21 (4): 814–845. doi:10.1177/1094428117752467.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Items included in the supervisor support scale, research community support scale and research engagement scale