?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Being exposed to workplace bullying is a stressful experience commonly associated with detrimental mental health consequences. Social support however has shown to be protective against such negative effects of bullying. This study used cross-sectional survey data to ascertain the prevalence of workplace bullying and examine its interplay with stress, burnout, and perceived social support among employees of higher education institutions in Sweden. Data was collected online in 2021 from 15,080 employees (47.5% response rate) of 38 higher education institutions in Sweden. Frequency statistics showed that the prevalence of workplace bullying was relatively low among participants. Using hierarchical regressions, workplace bullying was found to be significantly positively associated with stress and burnout, respectively. Suggesting that as bullying increases, so does the experience of these outcomes. Moderation analyses showed that perceived social support moderated those relationships – reducing stress and burnout when bullying exposure was low to moderate. However, the protective benefits appear to fade when bullying intensity increases. This study provides the first glimpse into these specific occurrences within Swedish education settings. Future research that follows up on these findings is required, yet this study lays the base knowledge of understanding to be built upon.

Introduction

Workplace bullying and its consequences have been an area of great interest among researchers for a long time (Nielsen and Einarsen Citation2018). Investigations of workplace bullying in educational settings were initially neglected even though such milieus make up a large component of the workforce (King and Piotrowski Citation2015). Eventually, researchers began to examine bullying in their own backyards with the emergence of studies from across the globe (Keashly Citation2019) which has since been ongoing for several decades (Heffernan and Bosetti Citation2021). Despite considerable progress within the field, more research remains necessary (Henning et al. Citation2017; Meriläinen et al. Citation2019; Rai and Agarwal Citation2018).

Workplace bullying in higher education

Bullying is considered a behaviour that harasses, excludes, or offends another and often leads to negative outcomes. It can intensify throughout time which places the target in a position of inferiority and victim to methodical harmful behaviours (Einarsen et al. Citation2011). Workplace bullying in higher education is pervasive (Lemon and Barnes Citation2021; Miller et al. Citation2019) and thought to be greater than in other occupational settings (Barratt-Pugh and Krestelica Citation2019; Zabrodska and Kveton Citation2013). Prevalence rates, however, do vary across countries (Branch, Ramsay, and Barker Citation2013) with studies reporting that 7.9% to 62% of higher education employees have experienced or witnessed bullying behaviours at their workplaces (Conco et al. Citation2021; Erdemir et al. Citation2020; Hollis Citation2015; Meriläinen et al. Citation2019; Sigursteinsdottir and Karlsdottir Citation2022; Zabrodska and Kveton Citation2013).

Workplace bullying, stress, and burnout

Workplace bullying has been previously connected with decreased mental health (Branch, Ramsay, and Barker Citation2013; Conway et al. Citation2018; Keashly Citation2019; Pheko Citation2018; Verkuil, Atasayi, and Molendijk Citation2015). Various studies demonstrate that workplace bullying has both short- and long-term associations with negative outcomes. Among Spanish workers, daily bullying predicted increased distress later that evening (Rodríguez-Muñoz, Antino, and Sanz-Vergel Citation2017). In Denmark, public sector employees experienced higher stress levels two years after being subjected to workplace bullying (Grynderup et al. Citation2016; Nabe-Nielsen et al. Citation2017). Canadian faculty staff reported stress as the most reported consequence of workplace bullying (McKay et al. Citation2008). Additionally, Australian retail workers exposed to bullying at baseline showed increased burnout after six months (Tuckey and Neall Citation2014) and Danish employees suffered from emotional exhaustion two years later (Nabe-Nielsen et al. Citation2017).

Social support

Within the workplace setting, social support functions as a contextual resource that refers to the idea that colleagues and supervisors/managers are dependable sources for guidance, knowledge, advice and understanding (Cobb Citation1976; Tuxford and Bradley Citation2015). Social support is thought to be an important protective factor against the negative consequences of workplace bullying (Conway et al. Citation2018; Rossiter and Sochos Citation2018; Sigursteinsdottir and Karlsdottir Citation2022). A multisector study among employees in New Zealand found that support from colleagues and supervisors moderated the relationship between workplace bullying and psychological strain (Gardner et al. Citation2013). Strong leadership, akin to supervisor support, significantly buffered the association between workplace bullying and psychological distress in office workers from Poland (Warszewska-Makuch, Bedyńska, and Żołnierczyk-Zreda Citation2015). It has also been shown that colleague and supervisor support moderated the relationship between workplace bullying and burnout among employees from different sectors within the United Kingdom (Rossiter and Sochos Citation2018). In a large-scale study of employees from 96 Norwegian organisations, supervisor support moderated the relationship between workplace bullying and mental ill-health. Support from colleagues was also found to moderate this association, but only among women (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). Finally, a cross-sectional study carried out among employees of Swedish governmental institutions found that colleague support reduced the negative health impact associated with workplace bullying (Blomberg and Rosander Citation2020).

The stress buffering hypothesis

The stress buffering hypothesis provides an explanation for how social support may moderate the relationship between workplace bullying and poor mental health outcomes. The stress buffering hypothesis stipulates that support can ‘buffer’ – or in other words protect against – the potential negative impact that a stressful event can have on one’s wellbeing. According to this hypothesis, an event could induce stress if an individual feels threatened or under duress and they do not have the appropriate coping skills to manage the situation. Most people have the capability to manage a single stressful event, but the accumulation of events can strain one’s ability to problem-solve which introduces the possibility of negative health outcomes. It is therefore suggested that support can moderate the relationship between stressful events and negative health outcomes in two ways. Firstly, the provision of support inhibits an event being appraised as stressful by reducing the perception of harm or reinforcing one’s own coping capabilities. Secondly, support can prevent the stressful event resulting in negative outcomes by encouraging healthy coping behaviours or providing solutions to better manage the situation (Cohen and Wills Citation1985) ().

Figure 1. Support and the buffering hypothesis adapted from Cohen and Wills (Cohen and Wills Citation1985).

Relevance of the study

As indicated, workplace bullying tends to be pervasive in higher education institutions, and in general, bullying that occurs in the workplace is often associated with mental health issues. It has also been shown that social support has the potential to be protective against the negative mental health impacts of bullying in some workplaces. However, nothing is currently known about the prevalence of workplace bullying nor its relation to certain mental health issues, or the role of social support in moderating those relationships, amongst employees of higher education settings in Sweden. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide a snapshot of workplace bullying exposure and the possible associated adverse effects among employees of higher education settings in Sweden. It is also the only study to examine the moderating role of perceived social support in the relationship between workplace bullying, stress, and burnout within this specific population group. In addition, this is the largest prevalence study of gender-based violence including workplace bullying worldwide (Else Citation2022). Consequently, this research not only fills a gap in the existing literature but also has the potential to lay the groundwork for future efforts – both in terms of research but also for informing targeted policies and interventions. Overall, the findings should be helpful for improving the workplace climate and employee wellbeing within higher education settings.

Purpose of the study

The overall aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of workplace bullying and understand its relationship with stress, burnout, and perceived social support from colleagues and supervisors among employees of higher education institutions in Sweden.

Methods

Study design

This study is part of a larger project; a national cross-sectional study within Sweden on gender-based violence (including workplace bullying) in academia, conducted by Karolinska Institutet in collaboration with Statistics Sweden (SCB). The project is part of the Research and Collaboration Programme run by Karolinska Institutet, KTH, Malmö University, and the University of Gothenburg (https://ki.se/en/collaboration/national-study-on-gender-based-violence-in-academia-questions-and-answers).

Material

Study setting

The study took place within 38 higher education institutions that are members of the Swedish University and College Association located all throughout Sweden. Of these 38 institutions, there were 16 universities, 18 university colleges and 4 university art colleges.

Study participants

The study included individuals employed at higher education institutions in Sweden – both technical and administrative (TA), as well as teaching and research (TR) – at the time of data collection.

Recruitment of the participants

Participants were randomly selected from the SCB higher education register. The inclusion criteria were all those employed, either in temporary or permanent positions, and had been working for at least 6 months. There were no exclusion criteria. A total of 64,642 employees were eligible to be included in the process, of which 32,056 employees were randomly selected to participate. A physical invitation letter was sent to 31,721 employees (slightly less than the original sample selected due to people either dying or resigning etc.) which provided information about the study and login details to the online survey. Three physical reminder letters were sent to non-responders during the data collection period.

Sample size

The response rate was 47.5% which provided a sample of 15,080 participants.

Study time frame

This study used data collected between April and June 2021.

Type of data

Quantitative data was collected from the questionnaire and SCB register. Some variables are binary including sex and employment type. One variable is continuous, age. All other study variables are typically considered ordinal variables measured with a 5-point Likert scale yet will be treated as interval variables.

Data sources and management

Data was collected from a web-based questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed by researchers Björklund and Rudolfsson in collaboration with SCB using mostly validated measurement scales. Once the basic quality requirements were met, SCB disseminated the final version and collected the responses. Thereafter, SCB processed and depersonalised the data before delivering it to Karolinska Institutet for analysis.

The questions used to measure the variables were from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ ΙΙΙ) (Llorens et al. Citation2019). COPSOQ ΙΙΙ has been evaluated in the Swedish context and the questionnaire items were found to be appropriate for measuring bullying, stress, burnout, social support from supervisors, and social support from colleagues (Berthelsen et al. Citation2020). The internal reliability coefficients were all above 0.80 for these scales (Berthelsen et al. Citation2020). Multiple validation studies have also been carried out worldwide to measure the questionnaire’s capacity and usability which permits cross-cultural comparisons (Berthelsen et al. Citation2020; Llorens et al. Citation2019).

Variables

Outcome variables

The outcome variables are stress and burnout as measures of mental ill-health. Stress was measured with three questions from the COPSOQ (Berthelsen et al. Citation2020): ‘During the last 4 weeks, how often have you’: (1) had problems relaxing, (2) been irritable, (3) been tense. Response alternatives were: (1) All the time, (2) A large part of the time, (3) Part of the time, (4) A small part of the time, (5) Not at all. A new variable for stress is then created which includes the mean of those three constituting items and will be used for the analyses (Llorens et al. Citation2019). Burnout was measured with three questions from COPSOQ (Berthelsen et al. Citation2020): ‘During the last 4 weeks, how often have you’: (1) been emotionally exhausted, (2) been physically exhausted, (3) felt worn out. Response alternatives were: (1) All the time, (2) A large part of the time, (3) Part of the time, (4) A small part of the time, (5) Not at all. A new variable for burnout is then created which includes the mean of those three constituting items and will be used for the analyses (Llorens et al. Citation2019).

Exposure variable

The exposure variable is workplace bullying and was measured with one question from COPSOQ (Berthelsen et al. Citation2020): ‘Have you been exposed to bullying at your workplace during the last 12 months?’ accompanied with the following text ‘Bullying is when a person is repeatedly exposed to unpleasant or degrading treatment and finds it difficult to defend themselves’. Response alternatives were: (1) Yes, daily, (2) Yes, every week, (3) Yes, every month, (4) Yes, a few times, (5) No.

Moderating variables

The moderating variable is perceived social support from colleagues and managers/superiors and was measured with several questions from COPSOQ (Berthelsen et al. Citation2020). This study follows the definition of social support mentioned in the introduction. Support from colleagues is measured through two questions: ‘How often do you get help and support from your colleagues, if needed?’ and ‘How often are your colleagues willing to listen to your problems at work, if needed?’. Support from managers/superiors was also measured through two questions: ‘How often do you get help and support from your immediate superior, if needed?’ and ‘How often is your immediate superior willing to listen to your problems at work, if needed’. Response alternatives were: (1) Always, (2) Often, (3) Sometimes, (4) Seldom, (5) Never/Hardly. A new variable for perceived social support is then created by taking the mean of those four constituting items and will be used for the analyses (Llorens et al. Citation2019).

Covariates

Information on background variables was obtained from the SCB register. Sex was characterised as either male (1) or female (2). Whereas employment type was either technical and administrative (TA) (1) or teaching and research (TR) (2). Sex and age were both considered covariates because they have been previously associated with workplace bullying exposure (Niedhammer et al. Citation2013; Notelaers et al. Citation2011; Prevost and Hunt Citation2018). Employment type was also included since role problems are deemed to be a predictor of workplace bullying exposure (Hauge, Skogstad, and Einarsen Citation2007).

Analysis

A series of statistical analyses were performed using the version 27.0 IBM SPSS programme.

Prior to any investigations, the response alternatives for the questions measuring support, bullying, stress, and burnout were recoded so that the lower numerical value reflected the absence of event [i.e. (1) Not at all, (2) A small part of the time, (3) Part of the time, (4) A large part of the time, (5) All the time].

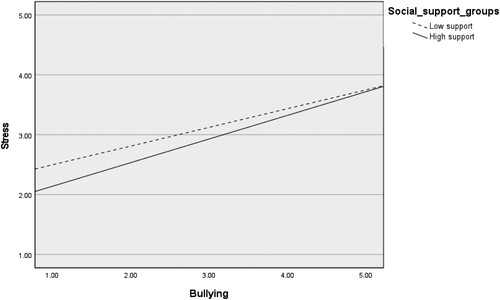

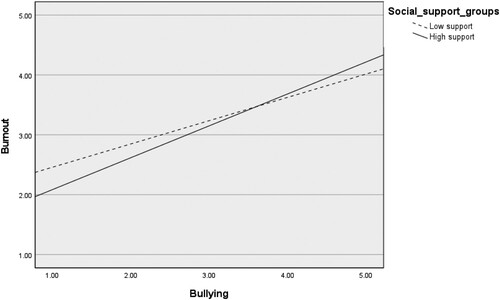

First, frequency and descriptive statistical analyses were performed. Zero-order correlations were then established to develop an understanding of the associations between variables. This meant that the strength and direction of linear relationships amongst variables could be shown, which then further corroborated which variables to control for in the regression analyses (Field Citation2009). Hierarchical regressions were performed to primarily ascertain how workplace bullying relates to both stress and burnout. The regression coefficients, statistical significance, and R2 values were used as estimates to identify the strength of associations and variance. The predictors were entered into the model hierarchically based on their known importance in predicting the outcomes (Field Citation2009). Moderation regression analyses were performed to determine the role of perceived social support between the exposure and outcomes, and whether the outcomes were different for employees with higher levels of perceived social support as opposed to lower levels (Memon et al. Citation2019). The regression coefficients, statistical significance, and R2 values were used as estimates to identify any moderation effect and variance. Lastly, to facilitate the visual representation of the moderation analyses, social support groups were created: below the mean is considered low social support and above the mean is considered high social support. A scatterplot graph with a line of best fit was created to display these findings. All results were deemed statistically significant if the p-value was below .05 (α = 0.05).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (reference number: 2021-006509-02). There are no conflicts of interest to disclose for this project.

Results

Background characteristics

Of the 15,080 participants, there was a greater proportion of females (n = 8670; 57.5%) than males (n = 6410; 42.5%). The age of study participants ranged from 19 to 87 years old, with the average age being 53 years. More participants were employed as TR staff (n = 8494; 56.3%) than TA staff (n = 6586; 43.7%).

Frequency statistics for workplace bullying

Most participants (n = 13465, 89.3%) had reportedly not experienced workplace bullying during the previous 12 months. Some participants (n = 1567, 10.3%) had experienced workplace bullying during the previous 12 months, although many of those participants (n = 1344, 8.9%) only experienced it a few times.

Descriptive statistics

The experience of workplace bullying (M = 1.13; SD = 0.43) was low among participants, with the average response being no exposure or seldom/few times during the previous 12 months. On average, low to moderate levels of stress (M = 2.32; SD = 0.86) were experienced among participants during the previous four weeks. Likewise, low to moderate levels of burnout (M = 2.28; SD = 0.95) were on average experienced during the previous four weeks. Lastly, high levels of perceived social support (M = 3.94; SD = 0.88) were on average experienced among participants. Concerning standard deviations, bullying has the smallest variance in responses in comparison to the mean, while burnout has the highest variance in responses.

Correlations

The results from the zero-order Pearson correlations test are described below. First, bullying is positively associated with sex (r = .069, p < .01) and employment type (r = .035, p < .01). Suggesting that females are more exposed to workplace bullying than males, and TR employees are more exposed than TA employees. Bullying is positively correlated with age (r = .012) albeit not at a statistically significant level (p > .05). There are positive associations between bullying and stress (r = .210, p < .01) along with bullying and burnout (r = .233, p < .01). This suggests that as bullying exposure increases, so does the experience of stress and burnout, respectively. Stress and burnout are positively correlated with sex (r = .072, p < .01 and r = .083, p < .01, respectively) and employment type (r = .091, p < .01 and r = .039, p < .01, respectively) but negatively associated with age (r = −.247, p < .01 and r = −.244, p < .01, respectively). This implies that females experience more stress and burnout than males, and TR employees experience more stress and burnout than TA employees. While as age increases, stress and burnout likely decrease. Furthermore, stress and burnout are positively related (r = .785; p < .01) indicating that as one increases, so does the other. Meanwhile, social support is negatively related to bullying exposure (r = −.321, p < .01) which might indicate that as support increases, bullying decreases. Social support is negatively related to stress (r = -.275, p < .01) and burnout (r = −.268, p < .01) suggesting that as support increases these outcomes decrease. Lastly, social support is positively related to sex (r = .030, p < .01) suggesting that females perceive higher levels of social support than males, but negatively related to age (r = −.067, p < .01) implying that perceived social support decreases with age. A negative association of social support and employment type (r −.124, p < .01) suggests that TR employees perceived lower levels of social support than TA employees.

Hierarchical regression analyses

and present the results of the hierarchical regression models for each dependent variable. Model 1 signifies the first step in the hierarchies where bullying is used as the only predictor. There was a significant positive association between bullying and the outcomes indicating that as bullying increases so does the experience of stress and burnout. When bullying increases by one standard deviation, stress increases by 0.21 standard deviations, constituting a change of 0.18 in stress (0.21 × 0.86) and burnout increases by 0.23 standard deviations, constituting a change of 0.22 in burnout (0.23 × 0.95). Bullying accounted for 4.4% and 5.4% of the variation in stress and burnout, respectively. Model 2 includes social support as an additional predictor of stress and burnout. The significant positive relationship between bullying and the outcomes remained, although the standardised beta coefficient has decreased almost by half. A significant negative association was identified between social support and the outcomes indicating that as social support increases, the experience of stress and burnout decreases. When social support increases by one standard deviation, stress decreases by 0.23 standard deviations which constitutes a change of 0.20 in stress (0.23 × 0.86) and burnout decreases by 0.22 standard deviations, constituting a change of 0.21 in burnout (0.22 × 0.95). Now, the R2 value increased from .044 to .092 and from .054 .096 with social support also being included as a predictor of stress and bullying, respectively. Therefore, bullying still accounts for 4.4% of the variation in stress, while social support accounts for an additional 4.8% of the variation. Similarly, bullying still accounts for 5.4% of the variation in burnout while social support accounts for the additional 4.2% variation. Model 3 represents the third step in the hierarchies where sex, age, and employment type were added as covariates. Significant associations still exist between the previous predictors and the outcomes with only marginal changes in the beta coefficients. Significant positive relationships exist between sex and employment type with the outcomes. Whereas a significant negative association was identified between age and the outcomes. The R2 value increased from .093 to .176 and from .096 to .172 with the inclusion of sex, age, and employment type as predictors of stress and burnout, respectively. Therefore, the covariates account for an additional 8.3% variation in stress and 7.5% of the variation in burnout. There may not be large differences in absolute terms for the R2 value and R2 values, but in relative terms, there is roughly a two-fold increase in explained variance between models suggesting that the addition of predictors at each step significantly contributes to stress and burnout.

Table 1. Hierarchical regression models predicting stress from the exposure variable (bullying), moderator variable (social support) and covariates (sex, age, employment type) (N = 15,080).

Table 2. Hierarchical regression models predicting burnout from the exposure variable (bullying), moderator variable (social support) and covariates (sex, age, employment type) (N = 15,080).

Moderation analyses

and present the results of the moderation regression models for each dependent variable. The standardised beta coefficients for the predictor variables indicate that the effect of absolute effect of having social support is to some extent stronger than exposure to workplace bullying in affecting stress and burnout. Holding the level of bullying constant, for every unit increase in social support, stress and burnout become a positive linear function with bullying. Even though social support reduces overall stress and burnout (which is 3.08 and 3.05 without any social support or bullying, respectively), the interaction effect of bullying is counteracting against it and resulting in a 0.15 (.07 + .08) unit increase in stress and a 0.18 (.07 + .11) unit increase in burnout with every unit increase in bullying. Therefore, if bullying is sufficiently large, it will still result in higher levels of stress and burnout. Bullying, social support, and the interaction variable account for 9.3% of the explained variance in stress (R2 = .093, p < .001) and 9.7% of the explained variance in burnout (R2 = .097, p < .001) ( and ).

Table 3. Moderation regression model with bullying as the independent variable, stress as the dependent variable and social support as a moderator (N = 15,080).

Table 4. Moderation regression model with bullying as the independent variable, burnout as the dependent and social support as a moderator (N = 15,080).

Figure 2. Scatter plot with line of best fit to visualise how the relationship between workplace bullying and stress varies with low social support compared to high social support.

Figure 3. Scatter plot with line of best fit to visualise how the relationship between workplace bullying and burnout varies with low social support compared to high social support.

Both social support groups (low and high) have a steady increase in stress and burnout by bullying exposure. Stress and burnout levels are higher for those with low social support compared to high social support when bullying exposure is low to moderate. As bullying exposure increases the difference in stress and burnout levels between social support groups decreases until there is no longer a difference when bullying exposure is high, or in the case of burnout levels, the relationship between groups begins to inverse.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This study investigated the prevalence of workplace bullying among employees in Swedish higher education institutions, examining its association with stress and burnout, and the potential moderating effects of perceived social support from colleagues and supervisors. Instances of workplace bullying were low among participants. Females were found to experience higher levels of workplace bullying, stress, and burnout compared to males, while TR employees also faced more of these challenges than TA employees. Social support was perceived more strongly by females and TA employees, while it diminished with age. Despite the low incidence of workplace bullying and the low to moderate stress and burnout levels among participants, positive associations were observed, indicating that higher exposure to workplace bullying corresponded to increased stress and burnout experiences. Notably, perceived social support buffered these relationships. Higher perceived social support is linked to lower stress and burnout when bullying is low to moderate. Yet, as bullying intensified, the protective effect of support diminishes until group differences were no longer so pronounced. The findings emphasise the complex interplay between workplace dynamics, social support, and the wellbeing of employees.

Findings in relation to previous research

The study revealed that 8.9% of participants had experienced workplace bullying on a few occasions during the previous 12 months. While consistent with the prevalence rate (7.9%) among higher education employees in the Czech Republic (Zabrodska and Kveton Citation2013), these rates are much lower than those identified in other studies, ranging from 18% to 58% (Conco et al. Citation2021; Erdemir et al. Citation2020; Meriläinen et al. Citation2019). The low incidence of workplace bullying does challenge conventional views given the prevailing belief that bullying is unavoidable and unmanageable in this setting (Keashly Citation2019). Unfortunately, making sense of these surprisingly low prevalence rates proves challenging with limited information available. Albeit there is evidence from a longitudinal study among employees of higher education settings in Sweden suggesting that inadequate leadership, organisational climate, inconsistent role demands, and high sickness absenteeism can be predictors of bullying (Björklund, Vaez, and Jensen Citation2021). The variability in rates between settings could be attributable to conceptual difficulties giving rise to methodological differences (Hodgins and McNamara Citation2019), or alternatively might be influenced by cultural differences (Zabrodska and Kveton Citation2013).

Workplace bullying being associated with stress and burnout echoes the findings of previous research (Grynderup et al. Citation2016; McKay et al. Citation2008; Nabe-Nielsen et al. Citation2017; Rodríguez-Muñoz, Antino, and Sanz-Vergel Citation2017; Tuckey and Neall Citation2014). Of course, this study cannot claim that workplace bullying directly led to increased levels of stress or burnout as the data was collected simultaneously for all variables. However, evidence from longitudinal studies has shown that workplace bullying is associated with stress two years later (Grynderup et al. Citation2016; Nabe-Nielsen et al. Citation2017). Likewise, a longitudinal analysis previously found stronger evidence in favour of a direct relationship between workplace bullying and burnout compared to a bidirectional relationship (Nabe-Nielsen et al. Citation2017).

The results were in line with the stress-buffering hypothesis (Cohen and Wills Citation1985) as perceived social support moderated the relationships between workplace bullying with stress and burnout, respectively. Several studies have examined similar questions but looked at mental health in a broad sense (Blomberg and Rosander Citation2020; Gardner et al. Citation2013; Nielsen et al. Citation2020; Warszewska-Makuch, Bedyńska, and Żołnierczyk-Zreda Citation2015) and some studies have examined different sources of support (Blomberg and Rosander Citation2020; Gardner et al. Citation2013; Nielsen et al. Citation2020; Rossiter and Sochos Citation2018; Warszewska-Makuch, Bedyńska, and Żołnierczyk-Zreda Citation2015). Nevertheless, the findings of these investigations were similar and comparable to this study. Nielsen and colleagues identified that high levels of social support moderated the direct relationship between workplace bullying exposure and mental distress (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). The authors drew the same conclusion in that support plays an important buffering role (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). They also examined support sources from outside the workplace and discovered that non-work-related support moderated the relationship between workplace bullying and mental distress (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). This is relevant because our results suggest the influence of other factors. Therefore, it is plausible that non-work-related support could be an additional factor influencing the relationships among this study population. Another study revealed that colleague support moderated the relationship between workplace bullying and health/wellbeing but that it only offered protective benefits up until a certain point of bullying exposure (Blomberg and Rosander Citation2020) which was also found in this study. This discovery is not uncommon with other studies finding similar effects (Rossiter and Sochos Citation2018; Warszewska-Makuch, Bedyńska, and Żołnierczyk-Zreda Citation2015). Understandably, if someone is being exposed to workplace bullying on a frequent basis, the presence of support is unlikely to eliminate the associated negative outcomes.

Lastly, the data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic which could have impacted the results. Unfortunately, no information was available to ascertain the influence COVID-19 may have had on the study variables. During this time, the spread of COVID-19 infection was high in Sweden and measurements were being put in place (Ministry of Health and Social Affairs Citation2021) such as higher education institutions remaining open but operations being conducted from home where possible (Ahmadi et al. Citation2022; Sjödin et al. Citation2020). A recent study among a representative sample of working Norwegian’s during COVID-19 found that remote working appeared to offer protective benefits against workplace bullying (Bollestad, Amland, and Olsen Citation2022). This is thought to occur because of the reduction of in-person interactions (Bacher-Hicks et al. Citation2022; Bollestad, Amland, and Olsen Citation2022). On the other hand, it has been suggested that the pandemic may exacerbate bullying behaviours within academia (Mahmoudi and Keashly Citation2020). It should also come as no surprise that remote working has been found to negatively impact stress and burnout among employees, as well as feelings of social connectedness and perceived support from others within an organisation (Costin, Roman, and Balica Citation2023). There is the necessity for continued exploration and nuanced understanding in this evolving landscape.

Strengths and limitations

There are several important strengths of this study. Firstly, the cross-sectional study design allowed for an abundance of data to be collected from a large sample of participants. This meant that the variables could be studied simultaneously, providing a broad analysis and findings that were previously lacking amongst this population group for this topic. Additionally, the random selection of participants from numerous institutions throughout Sweden increases the external validity, so the findings are likely generalisable beyond the study population. The use of validated measurement instruments for data collection also increases the internal validity and enables more precise conclusions to be drawn. Lastly, applying the stress-buffering hypothesis helped to guide the research and illustrate the relationship between variables.

The most obvious limitation of this study is that the cross-sectional design does not allow for causal associations. It is possible that participants could have been stressed or burnt-out which then led to workplace bullying exposure due to the stigmatisation of mental health issues for example. Evidence from a longitudinal study does support this notion of a reversed association albeit only in some situations and there were stronger indications of bullying being a predictor of mental health issues (Einarsen and Nielsen Citation2015).

Some limitations exist with the perceived social support variable. There is no information regarding the psychometric properties of this variable and should be investigated further. Taking the mean of the four constituting questionnaire items from the two scales to create this new variable presumes that they have equal weighting. It is possible that one of the scales may play a more important role in perceived social support. However, since the individual means of these four constituting items were all within a relatively small interval it was presumed unlikely to considerably influence the measurement of perceived social support.

There is the possibility of non-response bias as of those contacted to participate in the survey, 53% (n = 16,641) did not respond. While difficult to know, non-responders could have systematically differed from responders concerning their exposure or outcome status. It is plausible that non-responders could have been less exposed to workplace bullying than responders and therefore not as inclined to participate in the survey due to the lack of personal relevance. Likewise, non-responders could have had fewer mental health concerns than responders also resulting in a reluctance to participate. This means that the prevalence of both workplace bullying and mental ill-health outcomes found in this study could be overestimated. On the other hand, it is also conceivable that non-responders could have been more exposed to workplace bullying than responders yet chose not to participate due to the distressing nature of disclosing those experiences. The same could be true for mental health-related concerns. This means that the prevalence of both workplace bullying and mental ill-health outcomes found in this study could be underestimated. Given the lack of information available on non-responders, the direction of any non-response bias cannot be confidently determined (Silman and Macfarlane Citation2002).

The study relied solely on self-reported data and is therefore vulnerable to the likelihood of recall bias. The survey required participants to assess their exposure to workplace bullying during the 12 months beforehand while only asking participants to report on the state of their mental health during the previous four weeks. Naturally, it can be difficult for participants to recall their exposure status over an extended period regardless of their outcome status. It is however presumed that participants who reported being more stressed or burnt out are more likely to recall their exposure to workplace bullying differently than participants with better self-reported mental health. Participants who have greater levels of stress or burnout could more actively search their memory, better recall those bullying experiences, or even exaggerate their exposure, due to the perceived importance of negative events in relation to their mental health status. Therefore, should such assumptions be true, it would have increased the positive association between workplace bullying and mental-ill health outcomes.

Study implications and future directions

Most notably, this study provided insight into an important issue in which information was previously lacking – the prevalence of workplace bullying, its association with stress and burnout, as well as the protective role of perceived social support specifically among employees of higher education settings in Sweden. With the rise of certain public-awareness campaigns, increased scrutiny has been placed on the occurrence of bullying and harassment in science, resulting in a push from research funders to ensure that anti-bullying cultures are being cultivated (Else Citation2022). The identification of low workplace bullying rates in this study thus provides a unique opportunity for the cultivation of anti-bullying cultures in science. Future research could unearth valuable insights by exploring factors contributing to these low prevalence rates. Depending upon the findings, these learnings could guide future endeavours aimed at improving the work environment in higher education settings globally. Qualitative research would also enhance the results of this study by providing deeper insights into the relationships between variables and other contributing factors. It would expand our understanding of the stress-buffering hypothesis and the exact mechanisms at play. There are different forms of support that can be given, and it would be useful to distinguish which types of support are either more commonly experienced among employees at higher education settings or which types are considered most supportive. It would also be advantageous to analyse whether forms of support given by different sources have varying impacts. For instance, research has suggested that instrumental support provided by supervisors has a greater positive impact for employees than when provided by colleagues (Jolly, Kong, and Kim Citation2021). It should not be forgotten that support can be provided from sources outside the workplace too, which were not reported on in this study yet require exploration to fully comprehend their role within this context. This study did not perform an in-depth investigation of the differences that existed between certain groups. Previous research has indicated that predictive factors of bullying can vary between academic and non-academic employees (Björklund, Vaez, and Jensen Citation2021). Studies have also indicated that women are more likely than men to be the providers of social support within the workplace (Beehr et al. Citation2003; Fuhrer et al. Citation1999). Therefore, future research should consider more comprehensive explorations. Furthermore, this study did not obtain information regarding the characteristics of bullying perpetrators. It would however be interesting to know whether bullying was being perpetrated more often by managers/superiors or colleagues and how that might be associated with the outcomes. For example, one study has found that bullying was more often perpetrated by superiors within public and private higher education institutions in Turkey (Minibas-Poussard Citation2018). It would also be valuable to investigate whether there is any variation in either the exposure, outcome, or moderating variables between the different educational settings or specific disciplines i.e. those that are female-dominated, or highly competitive programmes. Additionally, to determine if and how COVID-19 impacted these results further follow-up studies are needed to compare findings. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, research that can more confidently determine causal associations is recommended to build upon and strengthen these findings.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on the prevalence of workplace bullying and its connection with stress, burnout, and perceived social support among employees in Swedish higher education. Despite the relatively low prevalence of reported workplace bullying, the findings underscore its significant impact on mental health, revealing positive links to stress and burnout. Perceived social support emerged as a buffer, reducing stress and burnout when bullying occurs less frequently. However, as bullying intensifies, this protective effect diminishes. The lower prevalence rates in Swedish higher education settings may suggest a context that deviates from global norms, potentially offering crucial insights if future research identifies the specific factors contributing to the reduced incidence of bullying. These insights carry significant implications for shaping policies and interventions that aim to cultivate supportive workplaces and mitigate the adverse effects of workplace bullying. Further, and more robust, research is necessary to expand on these findings. Nevertheless, this study provides a foundational understanding, paving the way for healthier and more considerate higher education environments.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants of the National Study of Gender-Based Violence in Academia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Danielle Berglund

Danielle Berglund completed her Bachelor of Arts Degree at the University of Auckland with a major in Sociology and minor in Psychology. She recently obtained a Master of Medical Science in Public Health from Karolinska Institutet. Danielle has spent most of her short career focused broadly on mental health and suicide prevention research, with a recent interest in wellbeing within the workplace.

Anna Toropova

Anna Toropova is a postdoctoral researcher at Karolinska Institute. Her doctoral thesis focused on teacher effectiveness in relation to student cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes, including bullying victimisation. Her current research interests are in the field of prevention of mental ill-health at the workplace.

Christina Björklund

Christina Björklund is an associate professor in business administration/psychology at Karolinska Institute, Sweden. Her primary research areas include work environment, work motivation, leadership and its relationship to mental ill-health and productivity. One special area that Christina has focused on is bullying and harassment in academia and has led several projects in this research field.

References

- Ahmadi, F., S. Zandi, ÖA Cetrez, and S. Akhavan. 2022. “Job Satisfaction and Challenges of Working from Home During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study in a Swedish Academic Setting.” Work 71 (2): 357–370. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-210442.

- Bacher-Hicks, A., J. Goodman, J. G. Green, and M. K. Holt. 2022. “The COVID-19 Pandemic Disrupted Both School Bullying and Cyberbullying.” American Economic Review: Insights 4 (3): 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20210456.

- Barratt-Pugh, L. G. B., and D. Krestelica. 2019. “Bullying in Higher Education: Culture Change Requires More Than Policy.” Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 23 (2–3): 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2018.1502211.

- Beehr, T. A., S. J. Farmer, S. Glazer, D. M. Gudanowski, and V. N. Nair. 2003. “The Enigma of Social Support and Occupational Stress: Source Congruence and Gender Role Effects.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 8 (3): 220–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.8.3.220.

- Berthelsen, H., H. Westerlund, G. Bergström, and H. Burr. 2020. “Validation of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire Version III and Establishment of Benchmarks for Psychosocial Risk Management in Sweden.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (9): 3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093179.

- Björklund, C., M. Vaez, and I. Jensen. 2021. “Early Work-Environmental Indicators of Bullying in an Academic Setting: A Longitudinal Study of Staff in a Medical University.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (12): 2556–2567. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1729114.

- Blomberg, S., and M. Rosander. 2020. “Exposure to Bullying Behaviours and Support from Co-Workers and Supervisors: A Three-Way Interaction and the Effect on Health and Well-Being.” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 93 (4): 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01503-7.

- Bollestad, V., J. S. Amland, and E. Olsen. 2022. “The Pros and Cons of Remote Work in Relation to Bullying, Loneliness and Work Engagement: A Representative Study among Norwegian Workers During COVID-19.” Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1016368.

- Branch, S., S. Ramsay, and M. Barker. 2013. “Workplace Bullying, Mobbing and General Harassment: A Review.” International Journal of Management Reviews 15 (3): 280–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00339.x.

- Cobb, S. 1976. “Social Support as a Moderator of Life Stress.” Psychosomatic Medicine 38 (5): 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003.

- Cohen, S., and T. A. Wills. 1985. “Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis.” In Psychologkal Bulletin 98 (2): 310–357.

- Conco, D. N., L. Baldwin-Ragaven, N. J. Christofides, E. Libhaber, L. C. Rispel, J. A. White, and B. Kramer. 2021. “Experiences of Workplace Bullying among Academics in a Health Sciences Faculty at a South African University.” South African Medical Journal 111 (4): 315–320. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i4.15319.

- Conway, P. M., A. Hogh, C. Balducci, and D. K. Ebbesen. 2018. Workplace Bullying and Mental Health, 1–27. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6173-8_5-1.

- Costin, A., A. F. Roman, and R. S. Balica. 2023. “Remote Work Burnout, Professional Job Stress, and Employee Emotional Exhaustion During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1193854. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1193854.

- Einarsen, S., H. Hoel, D. Zapf, and C. L. Cooper. 2011. “The Concept of Bullying and Harassment at Work: The European Tradition.” In Bullying and Harassment at Work and Their Relationships to Work Environment Quality, edited by S. Einarsen, 3–40. New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Einarsen, S., and M. B. Nielsen. 2015. “Workplace Bullying as an Antecedent of Mental Health Problems: A Five-Year Prospective and Representative Study.” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 88 (2): 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0944-7.

- Else, H. 2022. “Bullying in Science: Largest-Ever Survey Shows Bleak Reality.” Nature 607: 431. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01837-2.

- Erdemir, B., C. E. Demir, J. Yıldırım Öcal, and Y. Kondakçı. 2020. “Academic Mobbing in Relation to Leadership Practices: A New Perspective on an Old Issue.” The Educational Forum 84 (2): 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2020.1698684.

- Field, A. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (and sex and Drugs and Rock “n” Roll). Third Edition. London: SAGE Publications.

- Fuhrer, R., S. A. Stansfeld, J. Chemali, and M. J. Shipley. 1999. “Gender, Social Relations and Mental Health: Prospective Findings from an Occupational Cohort (Whitehall II Study).” Social Science and Medicine 48 (1): 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00290-1.

- Gardner, D., T. Bentley, B. Catley, H. Cooper-Thomas, M. O’driscoll, and L. Trenberth. 2013. “Ethnicity, Workplace Bullying, Social Support and Pscyhological Strain in Aotearoa/New Zealand.” New Zealand Journal of Psychology 42 (2): 84–91.

- Grynderup, M. B., K. Nabe-Nielsen, T. Lange, P. M. Conway, J. P. Bonde, L. Francioli, A. H. Garde, et al. 2016. “Does Perceived Stress Mediate the Association Between Workplace Bullying and Long-Term Sickness Absence?” Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 58 (6): e226–e230. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000750.

- Hauge, L. J., A. Skogstad, and S. Einarsen. 2007. “Relationships Between Stressful Work Environments and Bullying: Results of a Large Representative Study.” Work & Stress 21 (3): 220–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370701705810.

- Heffernan, T., and L. Bosetti. 2021. “Incivility: The New Type of Bullying in Higher Education.” Cambridge Journal of Education 51 (5): 641–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2021.1897524.

- Henning, M. A., C. Zhou, P. Adams, F. Moir, J. Hobson, C. Hallett, and C. S. Webster. 2017. “Workplace Harassment among Staff in Higher Education: A Systematic Review.” Asia Pacific Education Review 18 (4): 521–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-017-9499-0.

- Hodgins, M., and P. M. McNamara. 2019. “An Enlightened Environment? Workplace Bullying and Incivility in Irish Higher Education.” SAGE Open 9 (4): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019894278.

- Hollis, L. P. 2015. “Bully University? The Cost of Workplace Bullying and Employee Disengagement in American Higher Education.” SAGE Open 5 (2): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015589997.

- Jolly, P. M., D. T. Kong, and K. Y. Kim. 2021. “Social Support at Work: An Integrative Review.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 42 (2): 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2485.

- Keashly, L. 2019. “Workplace Bullying, Mobbing and Harassment in Academe: Faculty Experience.” In Special Topics and Particular Occupations, Professions and Sectors. Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment. Vol. 4, edited by P. D'Cruz, E. Noronha, L. Keashly, and S. Tye-Williams, 1–77. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5154-8_13-1.

- King, C., and C. Piotrowski. 2015. “Bullying of Educators by Educators: Incivility in Higher Education.” Contemporary Issues In Education Research-4th Quarter 8 (4): 257–262.

- Lemon, K., and K. Barnes. 2021. “Workplace Bullying Among Higher Education Faculty: A Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature.” Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 21 (9): 203–216.

- Llorens, C., J. Pérez-Franco, H. Oudyk, E. Berthelsen, M. Dupret, H. Nübling, H. Burr, and S. Moncada. 2019. COPSOQ III. Guidelines and questionnaire. COPSOQ III. Guidelines and Questionnaire. Contents. https://www.copsoq-network.org/guidelines.

- Mahmoudi, M., and L. Keashly. 2020. “COVID-19 Pandemic May Fuel Academic Bullying.” BioImpacts 10 (3): 139–140. https://doi.org/10.34172/bi.2020.17.

- McKay, R., D. H. Arnold, J. Fratzl, and R. Thomas. 2008. “Workplace Bullying in Academia: A Canadian Study.” Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 20 (2): 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-008-9073-3.

- Memon, M. A., J. H. Cheah, T. Ramayah, H. Ting, F. Chuah, and T. H. Cham. 2019. “Moderation Analysis: Issues and Guidelines.” Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 3 (1): i–xi. https://doi.org/10.47263/jasem.3(1)01.

- Meriläinen, M., K. Käyhkö, K. Kõiv, and H. M. Sinkkonen. 2019. “Academic Bullying among Faculty Personnel in Estonia and Finland.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 41 (3): 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1591678.

- Miller, G., V. Miller, C. Marchel, R. Moro, B. Kaplan, C. Clark, and S. Musilli. 2019. “Academic Violence/Bullying: Application of Bandura’s Eight Moral Disengagement Strategies to Higher Education.” Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 31 (1): 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-018-9327-7.

- Minibas-Poussard, J. 2018. “Mobbing in Higher Education: Descriptive and Inductive Case Narrative Analyses of Mobber Behavior, Mobbee Responses, and Witness Support.” Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 18 (2): 471–494. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2018.2.0018ï.

- Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. 2021, May 3. About the Government’s COVID-19 Measures, 22 April. https://www.government.se/articles/2021/05/about-the-governments-covid-19-measures-22-april/.

- Nabe-Nielsen, K., M. B. Grynderup, P. M. Conway, T. Clausen, J. P. Bonde, A. H. Garde, A. Hogh, L. Kaerlev, E. Török, and ÅM Hansen. 2017. “The Role of Psychological Stress Reactions in the Longitudinal Relation Between Workplace Bullying and Turnover.” Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 59 (7): 665–672. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001050.

- Niedhammer, I., J. F. Chastang, H. Sultan-Taïeb, G. Vermeylen, and A. Parent-Thirion. 2013. “Psychosocial Work Factors and Sickness Absence in 31 Countries in Europe.” The European Journal of Public Health 23 (4): 622–629. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cks124.

- Nielsen, M. B., J. O. Christensen, L. B. Finne, and S. Knardahl. 2020. “Workplace Bullying, Mental Distress, and Sickness Absence: The Protective Role of Social Support.” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 93 (1): 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01463-y.

- Nielsen, M. B., and S. V. Einarsen. 2018. “What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Should and Could Have Known about Workplace Bullying: An Overview of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 42: 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.06.007.

- Notelaers, G., J. K. Vermunt, E. Baillien, S. Einarsen, and H. De Witte. 2011. “Exploring Risk Groups Workplace Bullying with Categorical Data.” Industrial Health 49 (1): 73–88. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.MS1155.

- Pheko, M. M. 2018. “Autoethnography and Cognitive Adaptation: Two Powerful Buffers Against the Negative Consequences of Workplace Bullying and Academic Mobbing.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 13 (1): 1459134. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1459134.

- Prevost, C., and E. Hunt. 2018. “Bullying and Mobbing in Academe: A Literature Review.” European Scientific Journal, ESJ 14 (8): 1. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n8p1.

- Rai, A., and U. A. Agarwal. 2018. “A Review of Literature on Mediators and Moderators of Workplace Bullying: Agenda for Future Research.” Management Research Review 41 (7): 822–859. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-05-2016-0111.

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., M. Antino, and A. I. Sanz-Vergel. 2017. “Cross-Domain Consequences of Workplace Bullying: A Multi-Source Daily Diary Study.” Work and Stress 31 (3): 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1330782.

- Rossiter, L., and A. Sochos. 2018. “Workplace Bullying and Burnout: The Moderating Effects of Social Support.” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 27 (4): 386–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1422840.

- Sigursteinsdottir, H., and F. B. Karlsdottir. 2022. “Does Social Support Matter in the Workplace? Social Support, Job Satisfaction, Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace During COVID-19.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (8): 4724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084724.

- Silman, A. J., and G. J. Macfarlane. 2002. Epidemiological Studies: A Practical Guide. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sjödin, H., A. F. Johansson, Å Brännström, Z. Farooq, H. K. Kriit, A. Wilder-Smith, C. Åström, J. Thunberg, M. Söderquist, and J. Rocklöv. 2020. “COVID-19 Healthcare Demand and Mortality in Sweden in Response to Non-Pharmaceutical Mitigation and Suppression Scenarios.” International Journal of Epidemiology 49 (5): 1443–1453. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa121.

- Tuckey, M. R., and A. M. Neall. 2014. “Workplace Bullying Erodes Job and Personal Resources: Between- and Within-Person Perspectives.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 19 (4): 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037728.

- Tuxford, L. M., and G. L. Bradley. 2015. “Emotional Job Demands and Emotional Exhaustion in Teachers.” Educational Psychology 35 (8): 1006–1024. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.912260.

- Verkuil, B., S. Atasayi, and M. L. Molendijk. 2015. “Workplace Bullying and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis on Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data.” PLoS One 10 (8): e0135225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135225.

- Warszewska-Makuch, M., S. Bedyńska, and D. Żołnierczyk-Zreda. 2015. “Authentic Leadership, Social Support and Their Role in Workplace Bullying and Its Mental Health Consequences.” International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics 21 (2): 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2015.1028230.

- Zabrodska, K., and P. Kveton. 2013. “Prevalence and Forms of Workplace Bullying Among University Employees.” Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 25 (2): 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-012-9210-x.

Appendix

Appendix A

Table A. Frequency statistics for each questionnaire response for the exposure of workplace bullying (N = 15,032).

Appendix B

Table B. Mean and standard deviations for questionnaire items that made up outcome and moderator variables (N = 15,080).

Appendix C

Table C. Pearson correlation coefficients between exposure variable (bullying), moderator variable (social support) and covariates (sex, age, employment type) (N = 15080).