ABSTRACT

First-year students often lack basic self-regulated learning skills when transitioning to higher education. The emergency remote teaching period during the COVID-19 pandemic enhanced the importance of skills in self-regulated learning, due to the reduction of face-to-face contact with the teacher. This study focuses on first-year students’ experiences of their challenges related to self-regulated learning as well as how they engage in self-regulated learning during emergency remote teaching in autumn 2020. The data consisted of 67 reflective journals written by first-year students. The journals were analysed using a thematic analysis. The findings show that there were considerable differences between the students in terms of their ability to engage in self-regulated learning, particularly in how they approached the challenges mentally and in terms of study behaviour. However, most of the first-year students adjusted relatively well to emergency remote teaching in terms of their self-regulated learning and were able to utilise self-regulated learning strategies at least to some extent. This study stresses particularly the importance of some components of self-regulated learning: good time management skills and an ability to regulate attention, as well as positive academic emotions and a high level of self-efficacy. Conclusions of the study are also discussed.

Introduction

During the first weeks and months in higher education (HE), students adjust their expectations to the new environment – trying to identify what is needed in the new situation, as well as try to acquire a sense of one’s ability to cope and create relationships with others (De Clercq et al. Citation2018). This first encounter with HE can be a challenging period for students (McCardle et al. Citation2017; van der Meer, Jansen, and Torenbeek Citation2010). They may experience loneliness, lack of social support, feelings of maladjustment, and psychological discomfort (e.g. Díaz-Mujica et al. Citation2019). They might also find the need for independent studying in HE surprising, even shocking (Perander et al. Citation2020).

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020 and led to a total disruption of on-site teaching, students had a difficult time adjusting to what has been called emergency remote teaching (ERT) (Barbour et al. Citation2020). First-year students during the fall in 2020 were particularly vulnerable since they lacked previous experience of studying in HE, remotely, and independently. Hence, engaging in self-regulated learning (SRL) became very evident and important for these students.

There has been an explosion of research interest in university students’ experiences related to SRL, during the pandemic (e.g. Apridayani, Han, and Waluyo Citation2023; Biwer et al. Citation2021; Hadwin et al. Citation2022; Hamdan et al. Citation2021; Hensley, Iaconelli, and Wolters Citation2022; Klimova et al. Citation2022; Liebendörfer, Kempen, and Schukajlow Citation2022; Lin and Dai Citation2022; Mahmud and German Citation2021; Meshram, Paladino, and Cotronei-Baird Citation2022; Naujoks et al. Citation2021; Pelikan et al. Citation2021; Sutarni et al. Citation2021; Tabuenca, Greller, and Verpoorten Citation2022).

Despite this, both Hensley, Iaconelli, and Wolters (Citation2022) and Xu et al. (Citation2023) call for more research on self-regulated learning in online and ERT learning contexts. Moreover, an exceptional feature of the pandemic was that challenges with self-regulated learning became easier to detect and identify since the loss of teacher support made students’ shortcomings related to SRL more visible. That is why circumstances like the pandemic are valuable outsets for researching aspects related to teaching and learning, particularly students’ SRL skills. However, we already have some research knowledge on students’ SRL challenges in general during the pandemic (Biwer et al. Citation2021; Naujoks et al. Citation2021; Pelikan et al. Citation2021), as well as how students in general adapted to ERT in terms of SRL (Biwer et al. Citation2021). Since previous research (e.g. Biwer et al. Citation2021) suggests that students differed in their approach and abilities to adapt to ERT, we focus in this study on investigating these (qualitative) varieties between first-year students in terms of SRL.

Addressing such gaps in research, our research question is: What were the students’ various experiences of their self-regulated learning during ERT? The focus lies on students’ SRL-related challenges with ERT and how they coped with these challenges with the support of resource-management and metacognitive strategies. We also investigated students’ level of academic self-efficacy.

This paper proceeds with a presentation of the theoretical framework and a literature review. Next, we describe the context of the study, the data, the method and the participants. We then present the findings. Next, we discuss the findings in the light of previous research. Lastly, we present some conclusions based on our results.

Theoretical framework

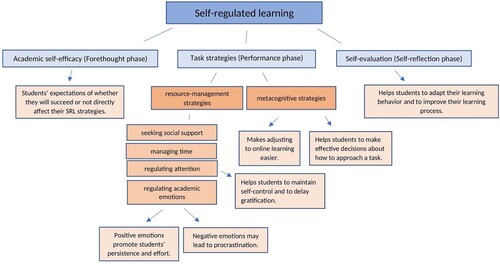

According to Panadero (Citation2017), self-regulated learning includes aspects related to learning, such as cognitive, metacognitive, behavioural, motivational, and emotional/affective aspects. Consequently, theories, models and concepts related to SRL, and how these are interrelated, have been widely discussed in research (e.g. Hardy, Day, and Steele Citation2019; Puustinen and Pulkkinen Citation2001; Zimmerman and Schunk Citation2001). Therefore, a visualisasion of concepts and their interrelationship relevant for this study can be found in .

Self-regulated learning is generally described as a self-directed process in which students reconstruct mental abilities into academic skills they can use for planning, engaging in and completing tasks (Zimmerman Citation2002). Students ideally measure their learning against a standard such as the feedback they receive, which provides information about their performance. When reflecting on the feedback, students with good SRL skills can readjust the learning process if needed (Pintrich Citation2004). Researchers have illustrated this process in various ways (Boekaerts Citation1991; Winne and Hadwin Citation1998), but Zimmerman’s Cyclical phases model (2002) is the most referred to in educational research (Panadero Citation2017).

Zimmerman’s model is organised into three phases: forethought, performance, and self-reflection (Zimmerman Citation2002). First, students analyse the task, set goals and plan how to achieve these goals, as well as reflect on their capability to learn. Second, students monitor their performance, employ suitable learning strategies, and self-observe their behaviour. In the third phase, students focus on self-reflection and self-evaluation – they might find explanations of reasons for success or failure (causal attribution), but also adapt their learning behaviour to improve their learning process (Zimmerman Citation2002).

Students may use a variety of resource-management and metacognitive strategies as part of their SRL behaviour (Dresel et al. Citation2015). Resource-management strategies (Biwer et al. Citation2021; Dresel et al. Citation2015; Panadero Citation2017) refer to students’ ability to create optimal learning settings, that is to seek social support, to manage time as well as to regulate attention and emotions. Regulating attention, maintaining self-control and delaying gratification, (Duckworth et al. Citation2019) may contribute to students’ academic progress, especially in remote teaching settings (Zhu, Au, and Yates Citation2016) and is therefore essential for particularly first-year students’ academic progress (Stork et al. Citation2016). Metacognitive strategies on the other hand, can help students become aware of their own cognitive abilities, understand how they learn, and make more effective decisions about how to approach a task or solve a problem (Zimmermann Citation2000). Recent studies also highlight the importance of metacognitive strategies in adjusting to ERT, to support students in planning and managing their learning (Biwer et al. Citation2021; Pelikan et al. Citation2021).

The extent to which students can utilise their SRL strategies is associated with important subcomponents of SRL, such as the students’ level of academic self-efficacy (Bradley, Browne, and Kelley Citation2017) as well as their academic emotions (Asikainen, Hailikari, and Mattsson Citation2018). Academic self-efficacy (ASE) refers to students’ confidence in achieving academic success (Bandura Citation1997) and is believed to be one of the most important predictors of achievement (e.g. Schneider and Preckel Citation2017). Students with high levels of ASE also tend to use more SRL strategies than those with lower levels of self-efficacy (Zimmerman Citation2000).

Moreover, ASE is strongly related to academic emotions in the sense that students are believed to use their own emotions as cues in judging their efficacy (Usher and Pajares Citation2006). For instance, strong negative emotions concerning academic tasks can impair students’ beliefs about capability. Further, students experiencing negative academic emotions tend to concentrate on threats, which in turn restricts the cognitive resources essential for engaging in learning activities (Derakshan, Smyth, and Eysenck Citation2009). Therefore, the ability to endure and regulate uncomfortable emotions when working on difficult tasks is important for SRL skills (Perander et al. Citation2020).

Literature review

Many studies have demonstrated that SRL is an important contributor to students’ learning success in general (e.g. Alegre Citation2014; Barnard-Brak, Lan, and Paton Citation2010; Broadbent and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz Citation2018; Broadbent and Poon Citation2015; Khan, Shah, and Sahibzada Citation2020; Perander, Londen, and Holm Citation2021; Puzziferro Citation2008; Wolters and Brady Citation2020; Yot-Domínguez and Marcelo Citation2017; Zhu, Au, and Yates Citation2016). Particularly, SRL plays an important role in first-year students’ adjustment to HE (Cazan Citation2013) but also in their adjustment to online learning (Broadbent and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz Citation2018).

However, students’ ability to make use of SRL can become more difficult in online environments than in face-to-face settings due to higher requirements for students to work autonomously and have more self-discipline (Barnard-Brak, Lan, and Paton Citation2010). Consequently, having the ability to regulate their own learning is crucial for university students to succeed in independent learning environments like online courses, and to compensate for the lack of face-to-face interaction that is typical in online education (Li Citation2019). Research stresses particularly students’ ability to manage and allocate time for studying (Wilson, Joiner, and Abbasi Citation2021), but also to restructure their learning environment and to seek help and support for their learning (Plant et al. Citation2005). The ability to employ social strategies is crucial for first-year students’ sense of belonging, and ultimately, for their academic success (van der Zanden et al. Citation2018).

Research on students’ experiences during ERT confirms that university students in general experienced heavy SRL-related challenges. The study of Naujoks et al. (Citation2021) found that students experienced challenges with utlising resource-management strategies during ERT, even if they in general perceived their digital readiness as high. The researchers assumed that students didn´t see the relevance of using such strategies or simply lacked the ability to use them. Other SRL-related challenges during ERT were problems with increased autonomy (Biwer et al. Citation2021), with procrastination as well as attention and effort regulation (Biwer et al. Citation2021; Naujoks et al. Citation2021), with isolation and lack of suitable learning facilities (Biwer et al. Citation2021; Cranfield et al. Citation2021; Thurab-Nkhosi, Maharaj, and Ramadhar Citation2021) and with unstable network connection (Apridayani, Han, and Waluyo Citation2023). Studies also point out the isolation from peers and teachers as one of the most severe challenges for university students (Biwer et al. Citation2021). Interaction made possible through breakout rooms was not enough to compensate for the lack of physical interaction and support (Hyland and O’Shea Citation2021).

Since studies have shown decreasing mental well-being among university students during the pandemic (Sarasjärvi et al. Citation2022) there was a likelihood of ASE to be negatively affected by ERT. However, studies on ASE during ERT show that self-efficacy beliefs might be resistant to extreme changes in the learning environment, such as the pandemic (Talsma et al. Citation2021). However, research suggests that ASE is associated with the level of students’ adjustment to ERT. Pelikan et al. (Citation2021) found in their study that even if all respondents perceived challenges with respect to keeping track of tasks as well as with time management during the pandemic, students that perceived themselves as having a high competence indicated that they were more successful in dealing with these challenges compared to students that perceived themselves as having low competence.

Despite the challenges students faced during the pandemic, research shows that students dealt with ERT fairly well (Liebendörfer, Kempen, and Schukajlow Citation2022), and some students even preferred online learning to attending offline classes (Hyland and O’Shea Citation2021). Most of the students were able to adapt to the new circumstances, especially in terms of regulating their efforts and time (Biwer et al. Citation2021) and in performing well with self-regulated online studying (Klimova et al. Citation2022).

Context of the study – self-regulated learning in Finnish education

Students entering higher education in Finland are expected to be well equipped with knowledge of self-regulated learning, for two reasons. First, both the national curriculum for basic education (FNAE Citation2014) and the core curriculum for general upper secondary education (FNBE Citation2016) point out the importance of SRL and advocate students becoming independent and self-regulated learners. Second, teachers in Finland are expected to use self-assessment practice – a key component of SRL – in basic education (grades 1–9) (FNAE Citation2014). Consequently, students are expected to have developed their skills in learning to learn and SRL when they transit to university (FNAE Citation2014). However, research shows that training in self-assessment is inadequate. A study of Finnish foreign language teachers in Finnish upper secondary schools (Mäkipää Citation2021) showed that most teachers do not teach their students to self-assess their learning. In addition, several other studies conclude that many Finnish students enter university with poor skills in SRL (Virtanen and Nevgi Citation2010).

Data, participants and method

The data consist of 67 reflective journals written by social science students who completed a mandatory self-study online course in study skills in autumn 2020, at a university in Finland. In all, 90 students participated in the course, and of these, 73 students consigned their reflective journals for our research. However, six of these students were not first-year students and were therefore excluded from the study.

Students entered the course in mid-October 2020. Their first assignment was to go through the course material related to SRL; the importance of self-directed learning, effective time management, efficient planning and study strategies. The material consisted of short video clips and written articles. The focus of the second assignment was to reflect on these issues in a reflective journal, as this would make the students become more aware of their own weaknesses and strengths in terms of their learning process. The deadline for the reflective journal (two to four pages) was in December 2020.

The students were provided with support questions to deepen their reflections. The questions were: (1) Briefly describe challenges or difficulties you may have encountered during your studies. Also, explain what works well in your studies. (2) Think about your time management and planning strategies: how do you get started on a task and what works well for you? (3) Describe your learning strategies and your way of studying.

Our method is inductive and data-driven since we wished to focus on the aspects that the students highlighted in their journals. We conducted a thematic analysis to investigate students’ reports of SRL-related challenges as well as how they managed to utilise SRL-related strategies. The advantage of qualitative thematic analysis is that it is flexible and provides rich and complex findings. The method encompasses six steps, which are: (a) the researchers become acquainted with the data, (b) generate initial codes, (c) search for themes, (d) review themes, (e) define and name themes and finally (f) produce a report. Our aim was to provide a more detailed and nuanced analysis of the employment of first-year students SRL strategies than previous research has been able to generate (Braun and Clarke Citation2006).

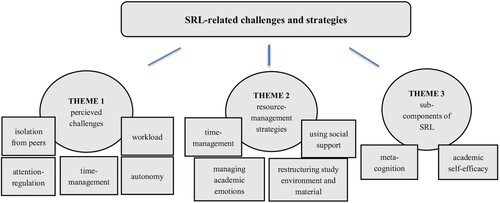

Initially, the journals were anonymised, and fed into the Atlas.ti program. Thereafter, they were read by all the authors multiple times to gain familiarity and to search for basic categories. Then, all the authors coded the same five journals and then compared the independently coded data and resolved discrepancies. The matrix SRL-related challenges and strategies was created during this process, with 3 main themes and 12 sub-themes. The first main theme was perceived challenges, including sub-themes isolation, attention regulation, time management, autonomy and workload. The second main theme was resource-management strategies, which included time management, academic emotions, restructuring study environment and material and social support. The third main theme was subcomponents of SRL that included academic self-efficacy and meta-cognition. The 12 sub-themes were used as codes (see ) during the final coding procedure, which was done by the main author. However, the coding was peer-reviewed repeatedly through the process by the other authors.

Since we aimed to investigate the variety among the students in terms of SRL use, we clustered the data in three categories depending on students’ perception of how they managed their studies and adjusted to ERT. Using clustering analysis to classify respondents in profiles is common in quantitative studies. However, in qualitative studies, clustering can also be applied, as this might reveal behavioural motives or reasons behind illogical results (Henry, Tolan, and Gorman-Smith Citation2005). According to Henry, Tolan, and Gorman-Smith (Citation2005, 121) clustering ‘involves sorting cases or variables according to their similarity on one or more dimensions and producing groups that maximise within-group similarity and minimise between-group similarity’. Hence, we attempted to form non-hierarchical clusters, where the categories were mutually exclusive.

We aimed to assign names to the categorised profiles that reflected how the students perceived themselves in terms of adjusting to the new learning environment, including ERT. Students that experienced low adjustment to and extreme challenges were labelled as ‘the stragglers’. These students voiced their experience as follows: ‘not much has worked well in my studies so far’. Further, students that experienced (difficult) challenges in beginning of their studies, but were able to adapt at least to some extent, were labelled as ‘the adjusters’: ‘I’m starting to get a handle on how I should plan my days, and I’ve noticed that academic life require the majority of my time’. Finally, students who experienced no or less burdensome challenges with their studies were labelled as ‘the capables’: ‘Haven’t had any particularly difficult challenges with studying’.

The study followed the ethical guidelines for research provided by the Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity (2023). The quotes from the reflective journals were translated from Swedish to English by the first author. Special care was taken in collaboration with all authors to ensure that the original meaning of the quotes was preserved in English.

However, using reflective journals as data has some limitations. First, reflective journals give the opportunity to reflect freely on a subject, especially since the support questions were quite broad. A higher number of support questions could have generated more multifaceted answers related to factors closely connected to SRL, such as students’ level of self-efficacy and academic emotions. On the other hand, this might have steered the students’ reflections too much. Research also argues that students might be dishonest when writing reflective journals as they often write what their teacher wants to hear rather than their honest opinions (Genua Citation2019). However, we stressed the importance of students’ own reflections, as this would support their development of SRL.

Findings

First, we shortly report the findings from the categorisation of students in profiles. Second, we report the qualitative findings according to the three main themes mentioned in . SRL-related challenges and strategies; (1) perceived challenges, (2) resource-management strategies and (3) academic self-efficacy and metacognitive strategies.

Student profiles

The categorisation of the students was conducted based on how they perceived themselves in terms of adjusting to the new learning environment, including ERT. This resulted in three groups of student profiles; (1) the stragglers, consisting of 6 students (9%), (2) the adjusters, consisting of 42 students (63%) and (3) the capables, consisting of 19 students (28%). As shown in , most students belonged to the adjusters-profile and only a small minority to the stragglers-profile.

Table 1. Student profiles: management of studies and level of adjustment to ERT.

Perceived challenges

The stragglers generally felt like they were unable to keep up with the other students. They reported feeling lost, being unconnected to university and experiencing the gap between upper secondary school and university as insuperable, as they were unable to use previously learned study strategies:

University studies have been more difficult than I expected, and a big reason is distance learning. I constantly feel in some way lost. It’s so different compared to how it was in upper secondary school and it’s hard to adjust to something completely new. The studies have been difficult, and I think it will take longer for me than for many others to develop good study techniques. (Student 26, the stragglers)

The adjusters typically experienced the same amount of confusion and stress in the transit to HE as the stragglers. They reported experiencing unsuccessful attention regulation when their phone was easy to reach, or they had been struggling with procrastination. However, these students made strong efforts to adjust to the new situation:

One of the biggest challenges has been studying remotely. Not getting up every morning and going to school has required a lot of self-discipline. Sometimes I’ve lacked the motivation to even leave bed – ‘nobody sees me anyway; I might as well just stay here’. I soon realized that this concept didn’t work at all. Studying from home has always diminished my ability to concentrate. I need a clear distinction between study and leisure time, so I started studying at the library instead. This turned out to be great for both my study techniques, efficiency, and mental health. (Student 20, the adapters)

I enjoy being able to choose what I want to study, and I don’t feel anxious about if I’m able to choose the right study path. I see myself as independent and I have good discipline. The challenges I have encountered have not been difficult to overcome. (Student 12, the capables)

Resource-management strategies

Most of the stragglers encountered severe difficulties with making use of resource-management strategies such as organising, structuring and planning as well as attention regulation as they struggled with ignoring distracting stimuli. In addition, undertaking and comprehending difficult and extensive course material were perceived as nearly impossible. Even so, some of these students reported being able to or tried to, use resource-management strategies, such as the calendar and making to-do lists, as these were perceived as simple methods of managing time. However, the strategies were used either in an unsystematic or in a non-functional way by the students. Failing in terms of strategy use caused stress and dissatisfaction for the students:

A disadvantage of writing lists is that I often think that I can achieve more than I do in a day, which in turn makes me feel unsuccessful and dissatisfied with my own performance. (Student 26, the stragglers)

The biggest difficulty has been getting used to Zoom-lectures. It feels less personal, harder to follow and there is a higher threshold for asking for help. After a while, I noticed that the best way to focus on the lectures is to actively take notes throughout the lecture. In this way, I follow the entire lecture. There were also complicated topics discussed during the lectures, but I have kept up with this aspect by studying the things that seemed difficult to me, in my leisure time. (Student 55, the adapters)

Remote learning has affected group work, conversations with other students and contact with teachers. Nevertheless, the group work I have participated in has worked well and I have built contacts with other students. Of course, meeting online has made the community much weaker. But my group members have been a huge support, as we were able to help each other understand the material. (Student 44, the adapters)

I have also tried to vary my study environment and I have tried different study techniques. Unfortunately, I haven’t found a study technique that feels 100%, but working in intervals has worked well some days. (Student 32, the adapters)

I manage well and I have the discipline needed. When I set my mind to something, I also get it done. I decide in the morning what to do and then make sure to get it done. Towards the evening, I go through what I have studied during the day. Then I relax in front of a movie or read a book. Therefore, the next day I am again motivated to study effectively because I know I can do something nice in the evening. (Student 45, the capables)

Metacognitive strategies and academic self-efficacy

The stragglers reported mainly negative emotional experiences when they approached their challenges, and their level of academic self-efficacy was generally low. They described their study process in general in negative words and were not satisfied with their academic achievement. This is noticeable in students’ descriptions of how they were to manage future assignments, as they feared that they lacked appropriate SRL strategies:

I dread when I must start reading thick course books. I’m afraid I’ll not be able to plan the reading effectively enough because it’s more demanding than the assignments I’m used to. The textbooks are boring and difficult to read. (Student 27, the stragglers)

A challenge for me has been the online literature. I like to take notes with paper and pen and read non-digital literature. But I’ve noticed that reading digital literature has become easier, and I think it will get even easier if I keep practising. I have also started taking notes on my computer, because it is easier to follow lectures and take notes if both are on the same screen. (Student 70, the adapters)

I constantly need to confront a thought pattern that developed during my childhood, where being wise was synonymous with being able to do things without asking for help. Therefore, asking for help feels difficult for me, both in my working life and in my studies, because I unconsciously think that I would be considered stupid if I asked for help. (Student 20, the adapters)

Through my hobbies (dance and music), I have developed a physical-kinesthetic talent. Another strength I possess is intuition. I largely have my mother to thank for that. She has taught me to understand myself and find my own path in life. She also has taught me to appreciate what I have and understand the responsibility that each of us carries for our own lives. My family has always supported me and convinced me that I can do whatever I set my mind to in life. (Student 58, the capables)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate first-year students’ perceived SRL-related challenges as well as how they engaged in SRL during ERT in the autumn of 2020 at a university in Finland. The research question was: What were the students’ various experiences of their self-regulated learning during ERT? We focused on students’ SRL-related challenges and how they coped with these challenges with the support of resource-management and metacognitive strategies. We also analysed students’ level of academic self-efficacy.

First, this study confirms the importance of self-regulated learning for study success among first-year students (e.g. Perander, Londen, and Holm Citation2021). Second, the respondents in general experienced all previously reported challenges with SRL during ERT, such as problems with organising their learning in general due to reduced social interaction as well as high demands on studying autonomously and (e.g. Biwer et al. Citation2021; Naujoks et al. Citation2021; Pelikan et al. Citation2021).

However, the most valuable contribution of this study are the results that emerged from the categorisation of the data in student profiles. The analysis produced three profiles that demonstrate how the students confronted the SRL-related challenges in considerably different ways in terms of their ability engage in SRL and particularly in how they approached the SRL-related challenges mentally.

The stragglers experienced a nearly total inability to engage in studying. The weight of too many various types of challenges such as managing the increased workload, the isolation from peers and teachers and the inability to manage their resources effectively became a burden. Particularly the inability to manage time and regulate attention, which led to procrastination, created a vicious circle where these students ended up with ‘getting nothing done’. They were not prepared for the degree of self-directedness that university studies and online studying required. It seems that the students were unable to perform the forethought phase (Zimmerman Citation2002) or were not aware of its importance for successful studying, as they were unable to plan and schedule their studies. In addition, these students reported low academic self-efficacy as they feared failure as well as often felt that they could not apply appropriate resource-management strategies for their learning (see also Naujoks et al. Citation2021; Schunk Citation1990).

The adapters, on the other hand, were able to adapt relatively well to ERT, presumably due to their high degree of persistence and academic self-efficacy as well as their positive academic emotions, as they focused more on their achievements than on their failures. In addition, they were in general able to make use of the feedback-loop, illustrated in Zimmerman’s SRL model (Citation2002). Through metacognitive reflection, they reflected on their previous mistakes and readjusted (parts of) their learning process, which in turn made them aware of advantages with planning, setting goals and reflecting on their capability to learn. Hence, they soon after the transit to HE, started to do strategic planning of their studies, managing them with time schedules or to-do lists, and allocating study time separately from leisure time.

Finally, the capables were satisfied with their study performance as of yet and expressed less burdensome or no challenges with ERT. Many of them even preferred ERT to onsite studying (see also Hyland and O’Shea Citation2021). Compared to the other students, they reported strong self-discipline and an ability to employ previously learned SRL strategies. They were especially talented in time management and attention regulation as they consciously avoided procrastination. They were interested in learning on a general level, highly motivated and focused on their strengths as learners. Many of these students did not ‘struggle’ with their studies at all – they just ‘got it done’.

Conclusion

First, it is obvious that most of the first-year students adjusted relatively well to ERT and HE and learned to, or were able to, regulate their learning at least to some extent during their first autumn at university. This is in line with previous research on both more experienced (Biwer et al. Citation2021; Hyland and O’Shea Citation2021; Klimova et al. Citation2022) and on first-year students (Liebendörfer, Kempen, and Schukajlow Citation2022). Second, the result of this study stresses particularly the significance of time management skills (see also Wilson, Joiner, and Abbasi Citation2021) and the ability to regulate attention, as well as the importance of positive academic emotions, a high level of self-efficacy and persistence, among first-year students during transit to university (see also Perander et al. Citation2020) and during ERT.

Third, becoming a self-regulated learner is not attained merely by personal processes, as students are also affected by contextual factors (Zimmerman Citation2000). Thus, teachers have a crucial role in supporting first-year students’ SRL skills, to avoid drop-outs among students such as the stragglers. A pandemic situation confirms the diversity between and among the students and widens the gap between those who have strong academic capital (e.g. parents with university education and/or a strong cultural capital) and those who enter HE without previous experience of an academic discourse. These aspects require teachers to be flexible in terms of the amount of support and supervision given to each student, especially during ERT. As we have seen in this study, remote learning is not suitable for all students. Even if students possess SRL skills and know how to apply them, isolation in combination with insufficient social support can still hinder efficient learning. Therefore, teachers should be attentive of how students manage in their studies, particularly during the encounter period when they transit to HE. In addition, training the students’ self-regulated skills, and especially stressing the importance of the forethought phase is equally important. Teachers should also encourage the students and strengthen their self-efficacy beliefs, through for instance positive and constructive feedback on their assignments (Caffarella and Barnett Citation2000). These issues need to be raised in university pedagogy training and in faculties’ discussion on the development of teaching.

rehe_a_2359107_sm9877.pdf

Download PDF (174.6 KB)rehe_a_2359107_sm9876.pdf

Download PDF (174.8 KB)Disclosure statement

This article has been published under the Journal’s transparent peer-review policy. Anonymised peer review reports of the submitted manuscript can be accessed under supplemental material online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2024.2359107.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Åsa Mickwitz

Åsa Mickwitz is a university lecturer in higher education at the Centre for University Teaching and Learning at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Her background is in linguistics, and her research interests include pedagogical leadership, self-regulated learning, multilingual pedagogy, and linguistic diversity.

Monica Londen

Monica Londen is a university lecturer in education at the faculty of educational sciences at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Her background is in education and psychology and her research interests include learning and teaching in higher education, self-regulated learning, and diversity in education. Her current research projects focus on educational leadership in higher education, positive education and inclusion and exclusion in early childhood education.

Katarina Perander

Katarina Perander is a PhD in educational sciences at the University of Helsinki and a special advisor in educational issues at The Swedish Parent Association in Finland. Her research interest includes transition to higher education, first-year experience, self-efficacy, self-regulation, academic emotions, parental involvement, and gender issues.

Susanne Tiihonen

Susanne Tiihonen is a psychologist and an integrative psychotherapist. Her main research interests include students’ well-being, self-regulated learning and academic emotions.

References

- Alegre, Alberto A. 2014. “Academic Self-Efficacy, Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Performance in First-Year University Students.” Propósitos y representaciones 2 (1): 101–120. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2014.v2n1.54.

- Apridayani, Aisah, Wei Han, and Budi Waluyo. 2023. “Understanding Students’ Self-Regulated Learning and Anxiety in Online English Courses in Higher Education.” Heliyon 9 (6): e17469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17469.

- Asikainen, Henna, Telle Hailikari, and Markus Mattsson. 2018. “The Interplay Between Academic Emotions, Psychological Flexibility and Self-Regulation as Predictors of Academic Achievement.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 42 (4): 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1281889.

- Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt.

- Barbour, Michael K., Randy LaBonte, Charles B. Hodges, Stephanie Moore, Barbara B. Lockee, Torrey Trust, Mark A. Bond, Phil Hill, and Kevin Kelly. 2020. “Understanding Pandemic Pedagogy: Differences Between Emergency Remote, Remote, and Online Teaching.” State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/items/39dde5cc-92d6-4f51-a1df-05f6dd7865fb.

- Barnard-Brak, Lucy, William Y. Lan, and Valerie O. Paton. 2010. “Profiles in Self-Regulated Learning in the Online Learning Environment.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 11 (1): 61–80. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i1.769.

- Biwer, Felicitas, Wisnu Wiradhany, Mirjam O. Egbrink, Harm Hospers, Stella Wasenitz, Walter Jansen, and Anique de Bruin. 2021. “Changes and Adaptations: How University Students Self-Regulate Their Online Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 642593–642593. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.642593.

- Boekaerts, Monique. 1991. “Subjective Competence, Appraisals and Self-Assessment.” Learning and Instruction 1 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-4752(91)90016-2.

- Bradley, Rachel L., Blaine L. Browne, and Heather M. Kelley. 2017. “Examining the Influence of Self-Efficacy and Self-Regulation in Online Learning.” College Student Journal 51 (4): 518–530. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rachel-Bradley-4/publication/325743793_Measuring_self-efficacy_and_self-regulation_in_online_courses/links/5d65857b299bf1f70b1234df/Measuring-self-efficacy-and-self-regulation-in-online-courses.pdf#page=74.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Broadbent, Jaclyn, and Matthew Fuller-Tyszkiewicz. 2018. “Profiles in Self-Regulated Learning and Their Correlates for Online and Blended Learning Students.” Educational Technology Research and Development 66 (6): 1435–1455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-018-9595-9.

- Broadbent, Jaclyn, and Walter L. Poon. 2015. “Self-Regulated Learning Strategies & Academic Achievement in Online Higher Education Learning Environments: A Systematic Review.” The Internet and Higher Education 27: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007.

- Caffarella, Rosemary, and Bruce G. Barnett. 2000. “Teaching Doctoral Students to Become Scholarly Writers: The Importance of Giving and Receiving Critiques.” Studies in Higher Education 25 (1): 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/030750700116000.

- Cazan, Ana-Maria. 2013. “Teaching Self Regulated Learning Strategies for Psychology Students.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 78: 743–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.04.387.

- Cranfield, Desirée J., Andrea Tick, Isabella M. Venter, Renette J. Blignaut, and Karen Renaud. 2021. “Higher Education Students’ Perceptions of Online Learning During COVID-19—A Comparative Study.” Education Sciences 11 (8): 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080403.

- De Clercq, Mikaël, Nathalie Roland, Magali Brunelle, Benoit Galand, and Mariane Frenay. 2018. “The Delicate Balance to Adjustment: A Qualitative Approach of Student’s Transition to the First Year at University.” Psychologica Belgica 58 (1): 67–90. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.409.

- Derakshan, Nazanin, Sinéad Smyth, and Michael W. Eysenck. 2009. “Effects of State Anxiety on Performance Using a Task-Switching Paradigm: An Investigation of Attentional Control Theory.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 16 (6): 1112–1117. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.16.6.1112.

- Díaz-Mujica, Alejandro D, María Victoria Pérez Villalobos, Ana B. Bernardo, Antonio Cervero, and Julio A. González-Pienda. 2019. “Affective and Cognitive Variables Involved in Structural Prediction of University Dropout.” Psicothema 31: 429–436. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2019.124.

- Dirgantoro, Kurnia, and Robert Soesanto. 2021. “The Impact of Pandemic Dynamics in Differential Calculus Course: An Overview of Students’ Self-Regulated Learning Based on Motivation.” In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Mathematics and Mathematics Education (ICMMEd 2020), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210508.043

- Dresel, Markus, Bernhard Schmitz, Barbara Schober, Christine Spiel, Albert Ziegler, Tobias Engelschalk, Gregor Jöstl, et al. 2015. “Competencies for Successful Self-Regulated Learning in Higher Education: Structural Model and Indications Drawn from Expert Interviews.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (3): 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1004236.

- Duckworth, Angela L., Jamie J. Taxer, Lauren Eskreis-Winkler, Brian M. Galla, and James J. Gross. 2019. “Self-Control and Academic Achievement.” Annual Review of Psychology 70 (1): 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103230.

- FNAE (Finnish National Agency for Education). 2014. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014. Helsinki: Finnish National Agency for Education.

- FNBE (Finnish National Board of Education). 2016. National Core Curriculum for General Upper Secondary Schools 2015: 8.

- Genua, J. Anne. 2019. “The Relationship Between the Grading of Reflective Journals and Student Honesty in Reflective Journal Writing.” PhD diss., Nova Southeastern University. https://www.proquest.com/openview/1140f0a8a1b5730f1e41c2c981eaba81/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- Hadwin, Allyson F., Paweena Sukhawathanakul, Ramin Rostampour, and Leslie Michelle Bahena-Olivares. 2022. “Do Self-Regulated Learning Practices and Intervention Mitigate the Impact of Academic Challenges and COVID-19 Distress on Academic Performance During Online Learning?” Frontiers in Psychology 13: 813529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.813529.

- Hamdan, Khaldoun M., Ahmad M. Al-Bashaireh, Zainab Zahran, Amal Al-Daghestani, Samira Al-Habashneh, and Abeer M Shaheen. 2021. “University Students’ Interaction, Internet Self-Efficacy, Self-Regulation and Satisfaction with Online Education During Pandemic Crises of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2).” International Journal of Educational Management 35 (3): 713–725. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2020-0513.

- Hardy, Jay, III, Eric A. Day, and Logan M. Steele. 2019. “Interrelationships Among Self-Regulated Learning Processes: Toward a Dynamic Process-Based Model of Self-Regulated Learning.” Journal of Management 45 (8): 3146–3177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318780440.

- Henry, David B., Patrick H. Tolan, and Deborah Gorman-Smith. 2005. “Cluster Analysis in Family Psychology Research.” Journal of Family Psychology 19 (1): 121–132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.121.

- Hensley, Lauren C., Ryan Iaconelli, and Christopher A. Wolters. 2022. “‘This Weird Time We’re in’: How a Sudden Change to Remote Education Impacted College Students’ Self-Regulated Learning.” Journal of Research on Technology in Education 54 (sup1): S203–S218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1916414.

- Hyland, Diarmaid, and Ann O’Shea. 2021. “The Student Perspective on Teaching and Assessment During Initial COVID-19 Related Closures at Irish Universities: Implications for the Future.” Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA 40 (4): 455–477. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrab017.

- Khan, Yar M., Mansoor H. Shah, and Habib E. Sahibzada. 2020. “Impact of Self-Regulated Learning Behavior on the Academic Achievement of University Students.” FWU Journal of Social Sciences 14 (2): 117–130. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/impact-self-regulated-learning-behavior-on/docview/2434402117/se-2.

- Klimova, Blanka, Katarina Zamborova, Anna Cierniak-Emerych, and Szymon Dziuba. 2022. “University Students and Their Ability to Perform Self-Regulated Online Learning Under the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Frontiers in Psychology 13: 781715. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.781715.

- Li, Kun. 2019. “MOOC Learners’ Demographics, Self-Regulated Learning Strategy, Perceived Learning and Satisfaction: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach.” Computers & Education 132: 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.003.

- Liebendörfer, Michael, Leander Kempen, and Stanislaw Schukajlow. 2022. “First-Year University Students’ Self-Regulated Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study.” ZDM – Mathematics Education 55 (1): 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-022-01444-5.

- Lin, Xi, and Yan Dai. 2022. “An Exploratory Study of the Effect of Online Learning Readiness on Self-Regulated Learning.” International Journal of Chinese Education 11 (2): 2212585X2211119. https://doi.org/10.1177/2212585X221111938.

- Mahmud, Yogi Saputra, and Emilius German. 2021. “Online Self-Regulated Learning Strategies amid a Global Pandemic: Insights from Indonesian University Students.” Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction 18 (2): 45–68. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2021.18.2.2.

- Mäkipää, Toni. 2021. “Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of Self-Assessment and Teacher Feedback in Foreign Language Teaching in General Upper Secondary Education – A Case Study in Finland.” Cogent Education 8 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1978622.

- McCardle, Lindsay, Elisabeth A. Webster, Adrianna Haffey, and Allyson Hadwin. 2017. “Examining Students’ Self-Set Goals for Self-Regulated Learning: Goal Properties and Patterns.” Studies in higher education 42 (11): 2153–2169. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1135117.

- Meshram, Kanika, Angela Paladino, and Valeria S. Cotronei-Baird. 2022. “Don’t Waste a Crisis: COVID-19 and Marketing Students’ Self-Regulated Learning in the Online Environment.” Journal of Marketing Education 44 (2): 285–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/02734753211070561.

- Naujoks, Nick, Svenja Bedenlier, Michaela Gläser-Zikuda, Rudolf Kammerl, Bärbel Kopp, Albert Ziegler, and Marion Händel. 2021. “Self-Regulated Resource Management in Emergency Remote Higher Education: Status Quo and Predictors.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 672741. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.672741.

- Panadero, Erenesto. 2017. “A Review of Self-Regulated Learning: Six Models and Four Directions for Research.” Frontiers in Psychology 8: 422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422.

- Pelikan, Elisabeth R., Marko Lüftenegger, Julia Holzer, Selma Korlat, Christiane Spiel, and Barbara Schober. 2021. “Learning During COVID-19: The Role of Self-Regulated Learning, Motivation, and Procrastination for Perceived Competence.” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 24 (2): 393–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-021-01002-x.

- Perander, Katarina, Monica Londen, and Gunilla Holm. 2021. “Supporting Students’ Transition to Higher Education.” Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 13 (2): 622–632. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-01-2020-0005.

- Perander, Katarina, Monica Londen, Gunilla Holm, and Susanne Tiihonen. 2020. “Becoming a University Student: An Emotional Rollercoaster.” Högre utbildning 10 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.23865/hu.v10.1462.

- Pintrich, Paul R. 2004. “A Conceptual Framework for Assessing Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning in College Students.” Educational Psychology Review 16 (4): 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x.

- Plant, E., K. Ashby, Anders Ericsson, Len Hill, and Kia Asberg. 2005. “Why Study Time Does Not Predict Grade Point Average Across College Students: Implications of Deliberate Practice for Academic Performance.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 30 (1): 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2004.06.001.

- Puustinen, Minna, and Lea Pulkkinen. 2001. “Models of Self-Regulated Learning: A Review.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 45 (3): 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830120074206.

- Puzziferro, Maria. 2008. “Online Technologies Self-Efficacy and Self-Regulated Learning as Predictors of Final Grade and Satisfaction in College-Level Online Courses.” American Journal of Distance Education 22 (2): 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640802039024.

- Sarasjärvi, Kiira K., Pia H. Vuolanto, Pia C. M. Solin, Kaija L. Appelqvist-Schmidlechner, Nina M. Tamminen, Marko Elovainio, and Sebastian Therman. 2022. “Subjective Mental Well-Being among Higher Education Students in Finland During the First Wave of COVID-19.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 50 (6): 765–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948221075433.

- Schneider, Michael, and Franzis Preckel. 2017. “Variables Associated with Achievement in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses.” Psychological Bulletin 143 (6): 565–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000098.

- Schunk, Dale H. 1990. “Goal Setting and Self-Efficacy During Self-Regulated Learning.” Educational Psychologist 25 (1): 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_6.

- Stork, Matthew, Jeffrey D. Graham, Steven R. Bray, and Kathleen A. Martin Ginis. 2016. “Using Self-Reported and Objective Measures of Self-Control to Predict Exercise and Academic Behaviors Among First-Year University Students.” Journal of Health Psychology 22 (8): 1056–1066. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315623627.

- Sutarni, Nani, M. Arief Ramdhany, Achmad Hufad, and Eri Kurniawan. 2021. “Self-Regulated Learning and Digital Learning Environment: Its Effect on Academic Achievement During the Pandemic.” Jurnal Cakrawala Pendidikan 40 (2): 374–388. https://doi.org/10.21831/cp.v40i2.40718.

- Tabuenca, Bernardo, Wolfgang Greller, and Domonique Verpoorten. 2022. “Mind the Gap: Smoothing the Transition to Higher Education Fostering Time Management Skills.” Universal Access in the Information Society 21 (2): 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-021-00833-z.

- Talsma, Kate, Kayleigh Robertson, Cleo Thomas, and Kimberley Norris. 2021. “COVID-19 Beliefs, Self-Efficacy and Academic Performance in First-Year University Students: Cohort Comparison and Mediation Analysis.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 643408–643408. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643408.

- Thurab-Nkhosi, Dianne, Chris Maharaj, and Varun Ramadhar. 2021. “The Impact of Emergency Remote Teaching on a Blended Engineering Course: Perspectives and Implications for the Future.” SN Social Sciences 1 (7): 159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00172-z.

- Usher, Ellen L., and Frank Pajares. 2006. “Sources of Academic and Self-regulatory Efficacy Beliefs of Entering Middle School Students.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 31 (2): 125–141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2005.03.002.

- van der Meer, Jacques, Ellen Jansen, and Marjolein Torenbeek. 2010. “‘It’s Almost a Mindset That Teachers Need to Change’: First-Year Students’ Need to be Inducted into Time Management.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (7): 777–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903383211.

- van der Zanden, Petrie J. A. C., Eddie Denessen, Antonius H. N. Cillessen, and Paulien C. Meijer. 2018. “Domains and Predictors of First-Year Student Success: A Systematic Review.” Educational Research Review 23: 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.01.001.

- Virtanen, Päivi, and Anne Nevgi. 2010. “Disciplinary and Gender Differences Among Higher Education Students in Self-Regulated Learning Strategies.” Educational Psychology 30 (3): 323–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443411003606391.

- Wilson, Robert, Keith Joiner, and Alireza Abbasi. 2021. “Improving Students’ Performance with Time Management Skills.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 18 (4): 230–250. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.4.16.

- Winne, Philip H., and Allyson Hadwin. 1998. “Studying as Self-Regulated Learning.” In Metacognition in Educational Theory and Practice, edited by Douglas J. Hacker, John Dunlosky, and Arthur C. Graesser, 277–304. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wolters, Christopher A., and Anna C. Brady. 2020. “College Students’ Time Management: A Self-Regulated Learning Perspective.” Educational Psychology Review 33 (4): 1319–1351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09519-z.

- Xu, Zhihong, Yingying Zhao, Jeffrey Liew, Xuan Zhou, and Ashlynn Kogut. 2023. “Synthesizing Research Evidence on Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement in Online and Blended Learning Environments: A Scoping Review.” Educational Research Review 39: 100510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100510.

- Yot-Domínguez, Carmen, and Carlos Marcelo. 2017. “University Students’ Self-Regulated Learning Using Digital Technologies.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 14 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0076-8.

- Zhu, Yue, Wing Au, and Greg Yates. 2016. “University Students’ Self-Control and Self-Regulated Learning in a Blended Course.” The Internet and Higher Education 30: 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.04.001.

- Zimmerman, Barry J. 2000. “Attaining Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Perspective.” In Handbook of Self-Regulation, edited by Monique Boekaerts, Paul R. Pintrich, and Moshe Zeidner, 13–40. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Zimmerman, Barry J. 2002. “Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview.” Theory Into Practice 41 (2): 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2.

- Zimmerman, Barry J., and Daniel H. Schunk. 2001. “Reflections on Theories of Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement.” Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: Theoretical Perspectives 2: 289–307.