ABSTRACT

Continued discussions concerning the adverse effects of high levels of inequality require a better understanding of tourism’s contribution to inclusive growth. If tourism is to be supportive of inclusive growth, it must create productive employment opportunities, while also ensuring equal access to these opportunities. This paper aims to analyse the constraints that prohibit the tourism sector from being a catalyst for inclusive growth, by developing a Tourism-Driven Inclusive Growth Diagnostic (T-DIGD) framework. This conceptual framework is adapted from the Hausmann, Rodrik, and Velasco growth diagnostic to the specific needs of the tourism sector and can support practitioners through a structured knowledge building process, in the design of policies and interventions that can promote inclusive growth. The T-DIGD departs from conventional and mainly quantitative approaches of the drivers of tourism growth and focuses on the “deep determinants” of tourism-driven inclusive growth.

Introduction

Inequality and the persistence of poverty within societies has become a significant subject of study. Disparity within countries can be detrimental to long-term growth (Bourguignon & Chakravarty, Citation2003); can threaten the political stability of a country (Balakrishnan, Steinberg, & Syed, Citation2013); and can have an adverse effect on crime, stability, and investments (Blau & Blau, Citation1982). The realization that growth itself is not sufficient to reduce poverty and that persistent inequality can negatively impact poverty reduction efforts has led policymakers to look for different strategies. The inclusive growth concept is the latest approach advocated by policymakers to improve living standards in the developing world. Rauniyar and Kanbur (Citation2010, p. 457) defined inclusive growth as “growth coupled with equal opportunities”. The United Nations' new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), have set development targets for 2030, and include two goals that specifically refer to inclusive growth: Goal 8—Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, and full and productive employment and Goal 10—Reduce inequality within and among countries (United Nations, Citation2015). The inclusive growth approach considers creating productive employment opportunities for marginalized groups as the primary means to reduce inequality within countries (Ianchovichina & Lundstrom-Gable, Citation2012). Tourism is considered a labour-intensive sector and includes requiring the utilizations of low skills and small investments and can, therefore, offer employment for low-skilled workers, ethnic minority groups and immigrants, unemployed youth, long-term unemployed as well as women with family responsibilities (UNWTO & ILO, Citation2014). Moreover, the tourism sector has a relatively high economic multiplier feeding into a vast and diverse supply chain including agriculture, handicrafts, transport and other subsectors (Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2010). The potential benefits of tourism's direct employment opportunities and economic multiplier are a reduction of poverty in emerging market and developing economies; although an overview of empirical studies shows mixed results (Croes & Rivera, Citation2016). Alam and Paramati (Citation2016) and Li, Chen, Li, and Goh (Citation2016) observed that tourism growth reduced income inequality within countries while Mahadevan and Suardi (Citation2017) found that tourism had reduced poverty levels but failed to reduce income inequality.

While the concept of inclusive growth receives much attention from development organizations and governments, the relationship between tourism and inclusive growth is under-examined in the academic literature. This paper builds upon the work of Hampton and Jeyacheya (Citation2012), Bakker and Messerli (Citation2017) and Hampton, Jeyacheya, and Long (Citation2017). For tourism to support inclusive growth, it must create productive employment as well as economic opportunities for entrepreneurs while also ensuring equal access to these generated jobs and opportunities (Bakker & Messerli, Citation2017). One of the first steps to achieve this is the identification, understanding, and prioritized removal of constraints that inhibit the growth and equal access of tourism opportunities, as well as the equal outcome (wage and non-wage) of these opportunities.

The aim of this paper is to analyse the tourism sector and its contribution to inclusive growth by presenting a Tourism-Driven Inclusive Growth Diagnostic (T-DIGD) framework for analysing and prioritizing the constraints to inclusive growth in a tourism sector context which may be useful for policymakers and governments. The methodology used for this conceptual paper includes a critical review of the literature on tourism and inclusive growth, the constraints to tourism-driven inclusive growth and existing growth diagnostic models. Findings identify the key constraints for the tourism sector to contribute to an inclusive growth strategy and the study proposes a framework to assess and prioritizes these constraints.

Tourism and inclusive growth

While there appears not to be a universally accepted definition, the concept of inclusive growth generally focuses on the link between economic growth, inequality and poverty reduction. The poverty–growth–inequality triangle supports the idea that a country's change in poverty is determined by a function of income, income growth, distribution and change of the distribution (Bourguignon & Chakravarty, Citation2003). This had led policymakers to realize that to reduce poverty, inclusive growth policies must “allow people from different groups—gender, ethnicity, religion—and across sectors—agriculture, manufacturing industry, services, to contribute to, and benefit from economic growth” (de Haan & Thorat, Citation2013, p. 8). This is similar to McKinley’s (Citation2010) approach to inclusive growth which involves two dimensions: sustainable growth that (i) will create and expand economic opportunities, and (ii) ensure broad access to these opportunities so that members of society can participate in and benefit from growth. Klasen (Citation2010) sees inclusive growth as a subset of economic growth and recognizes two aspects: (i) the process or opportunity approach examines the number of people who participated in the growth process and (ii) the outcome approach which looks at whether inclusive growth benefits people equally. Both approaches consider the creation of productive employment opportunities as the primary way to reduce inequality within countries and thereby achieve inclusive growth, which matches the belief that the primary concern of most people around the world, in developed as well as in developing countries, is to have a job (Melamed, Hartwig, & Grant, Citation2011). Klasen (Citation2010), McKinley (Citation2010) and de Haan and Thorat (Citation2013) all consider inclusive growth a long-term approach to development because the focus is to create productive employment rather than to redistribute income. The concept of inclusive growth can be considered a policy response to Sen's capability approach (Citation1993). The capability approach is about “improving and enhancing the quality of life and capabilities of all individuals by striving for a level of equitable parity within a community” (Hasmath, Citation2015, p. 3). With the attention on inclusive growth in the development debate, focus has then also shifted from inequality of outcome to inequality of assets and opportunities. The discussion on redistribution and inequality has moved hereby beyond outcome to include social opportunities especially participation in the economic process (Ngepah, Citation2017). For tourism to be considered inclusive it should then also contribute to the process of improving the terms for individuals and groups to take part in society. Critics of the inclusive growth approach consider it a neoliberal push for growth and argue that improving equality requires more substantial structural changes (Saad-Filho, Citation2010). Similarly, Scheyvens and Biddulph (Citation2017) argue that the inclusive growth approach is similar to the inclusive business approach and considers both as too limited to economic dimensions and ignoring fundamental root causes of poverty and inequality. The concept of inclusive growth is more widely embraced in countries with high levels of inequality, unemployment, and poverty where growth is used to create employment opportunities (Ali & Son, Citation2007).

Growth diagnostics

There has been increased recognition that development economics needs to take a wider approach to analyse growth, inequality and poverty reduction. As a result, tools have shifted from cross-country growth regressions to country-specific growth diagnostics (Sen & Kirkpatrick, Citation2011). The growth diagnostics methodology was first introduced by Hausmann, Rodrik, and Velasco (HRV) in 2005 (Hausmann, Rodrik, & Velasco, Citation2005). Their HRV diagnostic framework is grounded in the theory of endogenous economic growth and provides a systematic process to identify binding constraints and prioritizing policy reforms. It is based on the idea that there are many reasons why an economy does not grow, but that each reason has a distinctive set of symptoms (Hausmann et al., Citation2005). The model shows that development policy is country-specific and that a series of minor reforms in the correct sequence could relax binding constraints which could lead to positive welfare impacts (Ianchovichina & Lundstrom-Gable, Citation2012). Although the growth diagnostics approach was initially developed to identify the binding constraints to growth, the approach has also been applied to identifying critical constraints to the inclusiveness of growth. The Asian Development Bank (ADB), the World Bank, USAID, and the International Labour Organization (ILO) have developed several models to diagnose inclusive growth by expanding the HRV framework (Asian Development Bank, Citation2010; USAID, Citation2014; World Bank, Citation2011). HRV diagnostics generally follow the analytical country narrative as suggested by Rodrik (Citation2003) who recommends a combination of qualitative research methods to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying issues and the use of quantitative indicators to produce generalizable evidence that can be used to track progress and benchmark performance.

Constraints to tourism-driven inclusive growth

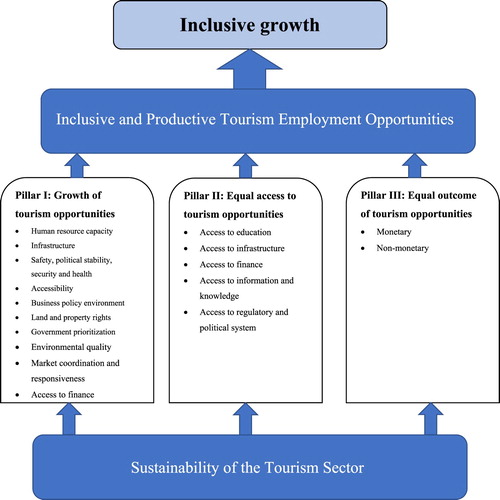

Based on the concepts of inclusive growth, the ability of the tourism sector to drive inclusive growth depends on the combined impacts and interaction of three different elements:

Growth of productive employment opportunities

Equal access to these opportunities

Equal outcome of tourism opportunities (income and non-income)

Following the HRV methodology, the three elements act as the pillars of the proposed framework. These pillars are associated with the general constraints and each of them addresses more specific issues. Following is an overview of the identified constraints for each of the three pillars as discussed in the literature.

Pillar I. Constraints to growth of tourism opportunities

Inclusive growth requires long-term increase of additional productive jobs and other economic opportunities (Ali & Son, Citation2007). It is important to note that the first pillar is defined as “Growth of tourism opportunities” and not “Tourism growth”. The critical goal is therefore not to increase the number of arrivals but the ability of the tourism sector to increase the volume and value of direct and indirect employment and self-employment opportunities. While this can be a result of increased number of arrivals, it can also result from increased per trip expenditures, reduction of leakage, increased number of linkages within the economy or a combination of these factors (Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2010). Dieke (Citation1989) identified external and internal factors affecting tourism development. External or exogenous factors affect the demand of the tourism generating countries. These external factors include GDP growth in the tourism generating countries, international competition, and global security issues in addition to others (Crouch, Citation1994). Issues such as the country's distance from the main generating countries and climate are also outside the control of countries. Conversely, internal factors are principally within the control of the destination and relate mostly to the supply of tourism products (Inskeep, Citation1991). Based on an extensive review of the literature, the following ten internal factors are identified as the most important potential constraints to the growth of tourism opportunities.

Insufficient human resource capacity

Tourism workers are widely portrayed as the critical dimension in the successful operation of tourism businesses and shortage of skilled labour is considered one of the main explanations of the poor performance of the tourism industry as exemplified by studies in Sub-Saharan Africa (Ankomah, Citation1991), Solomon Islands (Lipscomb, Citation1998), Turkey, China, Thailand and the Philippines (Liu & Wall, Citation2006), Central Asia (Baum & Thompson, Citation2007) and the Gambia (Thompson, O’Hare, & Evans, Citation1995).

Inadequate infrastructure

A country's infrastructure, including domestic transportation network (roads, airports, trains) as well as energy and communication technology (ICT), are critical determinants to the attractiveness of a destination (Inskeep, Citation1991). According to Henderson (Citation2009, p. 200) “countries with poor safety records and without an appropriate transport infrastructure and set of operators and services will be disadvantaged as tourist destinations”. The lack of infrastructure has also been noted by Graci and Dodds (Citation2010) as they discuss the problems which small islands may have concerning fresh water supply, sewage disposal, and electrical supply. A survey among Southern African community-based tourism enterprises showed that the most important (for 91% of all respondents) limitation was accessibility to road networks (Spenceley, Citation2008). Limited ICT infrastructure can also inhibit enterprises from being successful (Karanasios & Burgess, Citation2008).

Safety, insecurity, and health

Over the past ten years, the influence of safety and insecurity on tourism has received increased attention (Ghaderi, Saboori, & Khoshkam, Citation2017). The prevalence of outbreaks of infectious diseases has also had an impact on the tourism sector's ability to create employment (McKercher & Chon, Citation2004) as well as the acts of terrorism such as the attack on 9/11 and the bombings in Bali (Thompson, Citation2011). Political instability can have both short as well as long-term effects on tourism growth as supported by Richter and Waugh (Citation1986).

Limited accessibility

The level of transport connectivity with other countries determines the frequency and the cost of traveling to the destination. Connectivity is especially important for islands as they are often entirely dependent on adequate airlift (Bieger & Wittmer, Citation2006). The strong interdependence between air transport and tourism means that high prices for tickets or the absence of direct flights directly affects the competitiveness of a destination (Papatheodorou & Zenelis, Citation2013).

Restrictive business policy environment

Restrictive business policies can affect all economic sectors but some explicitly hinder the tourism sector. Examples are tourism-related taxation policies, strict regulations preventing seasonal labour as well as restrictive health and safety policies (Jenkins & Henry, Citation1982). Loureiro and Sarmento Ferreira (Citation2015) noticed a lack of continuity of policies and planned activities combined with deficient legislation regulating hotel classification as factors hindering tourism growth in Sao Tome and Principe. According to Thompson et al. (Citation1995), tourism in The Gambia in the 1980s suffered from high tourism-related taxes. Subbarao (Citation2008) concludes from his study that the multitude of taxes in India is one of the main reasons international hotel chains are hesitant to open a property in the country.

Limited access to land

Tourism development requires access to suitable land to build accommodation or other types of tourism businesses. Rao (Citation2002) studied tourism development in Fiji and concluded that issues around land tenure and property rights have been the major constraints facing tourism development in the country. The fact that it is impossible to freely buy and sell land in the marketplace due to the land tenure system had caused increased risk and uncertainty for hotel investors. Loureiro and Sarmento Ferreira (Citation2015) noted that in Sao Tome and Principe poor land management was a hindrance to tourism development. The government had allowed the cluttered use of space and has ignored areas reserved for tourism development and coastal areas as well as violated laws and standards.

Lack of tourism prioritization

While in most countries tourism is primarily a private sector initiative, the sector is also dependent on the support of the public sector (Kubickova, Citation2017). Government's role in prioritization of the tourism sector goes further than creating the supporting organizations as these bodies require political mandate and adequate resources (Dieke, Citation2003). For example, in The Gambia, tourism has suffered from chronic underfunding by the government (Thompson et al., Citation1995). Lack of sector focus by the government manifested through lack of strategic vision, lack of research and lack of control was considered one of the issues facing B&B owners in South Africa (Nuntsu, Tassiopoulos, & Haydam, Citation2004). Traditional bureaucracy might not be able to handle the tourism sectors’ need to be cross-governmental. As a result, “lack of co-ordination and co-operation between governmental departments can be very damaging to not only the quality of the tourism product but also to the efficacy of a participatory tourism development approach” (Tosun, Citation2000, p. 620).

Poor environmental quality

Issues around environmental management such as air and water pollution, beach erosion, illegally dumped waste and litter can have a negative impact on the tourism experience and thereby limit the sector's opportunity to grow employment opportunities (Hu & Wall, Citation2005). Mustika, Stoeckl, and Farr (Citation2016) showed a negative correlation between environmental deterioration and expenditure by leisure tourists in the Australia's Great Barrier Reef. Air pollution in Beijing has negatively impacted the city's attractiveness from a leisure traveller’s perspective (Zhang, Zhong, Zxu, Wang, & Dang, Citation2015).

Lack of market coordination and responsiveness

Failure to coordinate private sector stakeholders reduces the ability to innovate and meet the overall needs of the market. Carlisle, Kunc, Jones, and Tiffin (Citation2013) consider the fragmented nature of the industry as the main cause for the lack of collaboration. A study amongst B&B owners in South Africa showed that 80% of the respondents felt that a lack of communication and cooperation caused “fragmented institutions, the individualistic behaviour of operators and unwillingness to cooperate” (Nuntsu et al., Citation2004, p. 521). Lack of responsiveness such as limited entrepreneurship (Wilson, Fesenmaier, Fesenmaier, & Van Es, Citation2001), and mismatch of supply and demand (Benur & Bramwell, Citation2015) can result in weakened market competitiveness and missed opportunities.

Limited access to finance

Financial institutions are reluctant to provide loans to local tourism business, especially SMEs, often due to a lack of collateral and the fluctuating income of the businesses (Carrillo-Hidalgo & Pulido-Fernández, Citation2016). Surveys among tourism SMEs in Trinidad (Roberts & Tribe, Citation2005) and a study among small hotels in Tanzania by Sharma and Upneja (Citation2005) confirmed this. Ndabeni and Rogerson (Citation2005) indicated the lack of access to finance due to high-interest or high collateral requirements as one of the leading constraints for further tourism development in South Africa.

Pillar II. Constraints to equal access to tourism opportunities

The relationship between tourism and inequality has been a widely discussed topic and studied from different perspectives. Scholars such as Holden and Burns (Citation1995), who stated that tourism development could lead to “islands of affluence” in a “sea of poverty”, studied the role of tourism as a cause of inequality. Britton (Citation1982) indicated that the nature of the tourism sector reinforces existing political systems and economies causing inequality in developing countries. These and other studies indicate that complex economic, historical, political and cultural conditions are root constraints on the ability of tourism to provide equal opportunities for all groups within a society (Hall, Citation1994). Also, the concept of inequality is based on western norms of equality rights and might not fit all societies and groups (Deveaux, Citation2000). That notwithstanding, tourism policymakers can develop policy and programme responses to specifically mitigate the causes and effects of undesired inequalities. Tourism studies have identified differences in race, gender, ethnicity, geographic location and socio-economic status as the leading explanations for inequality of access to tourism opportunities (Scheyvens, Citation2002). Based on an extensive literature review, the author identified the following six factors as the primary constraints to equal access to tourism opportunities for marginalized groups:

Unequal access to education

To increase the chance of securing decent employment opportunities, people need skills and knowledge. The tourism literature focuses mostly on the lack of skills of the local population versus people from outside the community (Liu & Wall, Citation2006). For example, Schellhorn (Citation2010) found that in Lombok poor foreign language skills hindered access to tourism jobs for locals and in Elmina, Ghana the lack of general education was holding the locals back from opportunities (Holden, Sonne, & Novelli, Citation2011). Geographic location is identified as another constraint causing unequal access to (tourism) education. Due to the specialized nature of hospitality and tourism education, institutions that offer these tend to be in urban areas, which limits easy access by students in rural communities (Thapa, Citation2012). Low socio-economic status and associated low income was identified as the main constraint to tourism education by Meyer (Citation2007).

Unequal access to infrastructure

Tourism development tends to concentrate around the (international) transportation gateways and nodes with a concentration of attractions and can thereby lead to regional concentrations. The farther away a destination is from these gateways or nodes, the less likely it becomes for tourists to visit an area as Kundur (Citation2012) showed in his study on the Maldives. The availability of road infrastructure affects people's access to economic opportunities as well as to key public services (Koo, Wu, & Dwyer, Citation2012). Unequal access to drinking water, electricity, telecommunication services and sanitation also limits the opportunities for tourism development (Holden et al., Citation2011). The distance from the hubs makes it difficult for the tourism entrepreneur in rural areas to establish relationships with distributors such as travel agencies and tour operators needed to promote their products (Forstner, Citation2004).

Unequal access to finance

Access to finance for tourism enterprises is already problematic in developing countries, but for some groups, it is even more challenging. The literature discusses unequal access to finance for ethnic minorities, women, entrepreneurs based in rural areas, indigenous groups and locals. A survey of locally owned bed and breakfast establishments in South Africa showed that the majority of businesses were started using the entrepreneur's own or family savings due to lack of access to external funding (Rogerson, Citation2004). It is clear that it is more difficult for women than men to obtain financing in tourism (Meera, Citation2014) and also for tourism entrepreneurs in rural areas (Badulescu, Giurgiu, Istudor, & Badulescu, Citation2015). Land tenure systems are often an obstacle for access to finance for indigenous groups as banks are hesitant to provide finance to businesses that use communal land as collateral (Buultjens et al., Citation2010). In some cases, locals have less access to finance than foreigners as a survey among tourism SMEs in Trinidad found (Roberts & Tribe, Citation2005).

Unequal access to land

Hall (Citation2004) and Long and Kindon (Citation1997) found that women have consistently less access to land than men. While indigenous communities such as in the Solomon Islands (Sofield, Citation1993) might have access to communal land, banks do not allow loans on this type of land. Tourism initiatives that require significant investments are there for difficult to realize on communal land. Sirima and Backman (Citation2013) found that there are limited opportunities for local indigenous communities to benefit from tourism opportunities around the national parks in Africa as land use regulations are complex.

Unequal access to information and knowledge

Tourism-related information and knowledge of the sector is unequally spread over groups and groups with better access will have more opportunities to be included (Scheyvens, Citation2002). Lack of information concerning tourism development leaves groups vulnerable to exploitation, limits their access to participation (Ashley, Roe, & Goodwin, Citation2001) and can exclude them from business opportunities (Rogerson, Citation2004). Cole (Citation2006) found that lack of knowledge of the tourism development process was a hindrance to villagers’ self-esteem needed to develop tourism in Indonesia.

Unequal access due to institutional barriers

Institutional barriers including overregulation, bureaucracy and a centralized government can affect some groups more than others. Strict regulation can exclude specific regions from actively participating in tourism, as was the case in Upper Mustang in Nepal. The regulations in Nepal to protect local cultural and natural heritage meant that travellers were not allowed to travel to the area independently but had to organize their trip through a tour operator. Regulations also required porters to be recruited before reaching Upper Mustang leaving no opportunity for employment of the local population (Shackley, Citation1994). Constraints such as excessive bureaucracy can prohibit the poorest access to the market and to be involved in the tourism industry (Holden & Burns, Citation1995). Central governments often provide low priority to developing tourism in sparsely populated areas (Tosun, Timothy, & Öztürk, Citation2003).

Pillar III. Constraints to the equal outcome of tourism opportunities

Much of the relevant research on equal outcome of tourism opportunities focuses on gendered labour in the form of wage discrimination and occupational segregation (Figueroa-Domecq, Pritchard, Segovia-Pérez, Morgan, & Villacé-Molinero, Citation2015). Besides the gender pay gap for tourism jobs in countries such as Brazil (Ferreira Freire Guimarães & Silva, Citation2016) and Turkey (Pinar, McCuddy, Birkan, & Kozak, Citation2011), tourism also sees a disproportional distribution of women working in less desirable and lower paid positions (Campos-Soria, Garcia-Pozo, & Sánchez-Ollero, Citation2015). Gentry (Citation2007) reports that women managers only represent 3% of the total staff in large hotels in Belize and that this percentage is lower than that found in other types of companies. Van der Duim, Peters, and Akama (Citation2006) in their study on cultural manyattas in Tanzania found that while women are the main providers of services, the Maasai men receive a relative larger share of the tourism revenue. Tourism research on wage inequalities based on age (León, Citation2007), region (García-Pozo, Campos-Soria, Sánchez-Ollero, & Marchante-Lara, Citation2012) and socio-economic situation (Blake, Citation2008) is marginal. The non-monetary outcomes of tourism opportunities which include fringe benefits such as free or subsidized childcare, access to job-related housing, employee-sponsored health services and access to training have received very limited attention from tourism researchers (Sandbrook & Adams, Citation2012). Cross-sectoral empirical studies in the US showed that women benefit in general more from employer-provided benefits than men (Kolesnikova & Liu, Citation2011) but that ethnic minority groups receive relatively less non-monetary benefits (Kristal, Cohen, & Navot, Citation2018).

The Tourism-Driven Inclusive Growth Diagnostic Framework

Based on the three components required to achieve inclusive growth through tourism, the Tourism-Driven Inclusive Growth Diagnostic (T-DIGD) framework is proposed (). For the tourism sector to drive inclusive growth as a societal outcome, the sector should create productive employment opportunities that are accessible for everyone in the country and that have equal outcome. For tourism to achieve this, all three pillars need to be supportive of this goal. The three pillars are closely linked to each other. Both pillars I and II analyse factors concerning infrastructure, education, access to land and finance. For example, under pillar I the overall tourism-related infrastructure in the country is analysed, while under pillar II the access by specific groups within society is analysed. This means that the effects of these constraints to growth of tourism opportunities, and access to these opportunities needs to be analysed jointly as increased access to infrastructure can create virtuous circles of increased opportunity.

Obviously, inclusive growth requires a comprehensive and long-term approach because improvements in areas such as access to education and infrastructure require time to advance (Ali & Son, Citation2007). In addition, it is imperative that effect of growth on inclusiveness should be maintained over the long term (Ranieri & Ramos, Citation2013). Sustainability is especially relevant for the tourism sector as it is one of the few sectors where there is inseparability between production and consumption of the product as both take place in the same location (Inskeep, Citation1991). McKercher (Citation1993, p. 9) argues that “the greatest challenge facing sustainable tourism development is to ensure that tourism's assets are not permitted to become degraded”. The success of the three pillars needs to be then also supported by the ability of the sector to be sustainable from an economic, social and environmental perspective. While the framework's main objective is to assesses the ability of the tourism sector to contribute to SDG8 and SDG10, to achieve this long-term inclusive growth the pillars of the TIGDF also address other SDGs including SDG5 (gender equality) and SDG6 (environmental sustainability).

This framework could be implemented by using it as a diagnostic to assess and prioritize the different constraints in a systematic way using a mixed-methods approach. Quantitative methods in the form of a set of indicators for each of the constraints will allow benchmarking with comparative countries as well as trend analysis. Qualitative methods including interviews and document analysis will be used to gain deeper understanding of the underlying issues and allow validation of the quantitative data.

Conclusion

This paper has proposed a diagnostic framework to identify and prioritize the constraints to tourism-driven inclusive growth by linking the discussion on inclusive growth to the specific characteristics of the tourism sector. The research identified three elements that contribute to the tourism sector's ability to contribute to an inclusive growth strategy: (i) growth of tourism opportunities; (ii) equal access to tourism opportunities; and (iii) equal outcome of tourism opportunities. Assessing, prioritizing and addressing the constraints to each of these elements can contribute to a more inclusive tourism sector.

The design of the T-DIGD draws heavily from the HRV diagnostic framework; it has however been adapted to fit the tourism sector. This has some consequences. First, in almost all applications, the HRV diagnostic is used to systematically prioritize the constraints towards inclusive growth at an economy-wide level while the T-DIGD analyses a single sector. Sector-specific adaptation of the HRV diagnostic is still in an early stage, and just a few studies on inclusive growth by the World Bank and USAID involved a partly sector-specific diagnosis of the garment and tourism sectors (USAID, Citation2014; World Bank, Citation2016). Second, through the sector-specific adaptations, the T-DIGD methodology shifted from a mainly quantitative focus (as per the HRV) to a combined quantitative/qualitative approach. The specific tourism constraints require more in-depth examination and often lack the precise indicators to allow a purely quantitative approach. Third, the concept of binding constraints was also relaxed as factors inhibiting inclusive tourism growth are more diverse and context-specific than those inhibiting aggregated growth. The T-DIGD hereby has become a tool for structuring analysis, but without overly stringent rules and it can still be used for a process of elimination of less important factors. This was also recommended by the initial designers of the HRV diagnostic after the first implementations (Rodrik, Citation2007). Fourth, determining causal relationships between growth and inclusiveness is expected to be challenging. It will most likely raise questions such as “Do changes in inclusiveness result from growth or does more inclusiveness encourage growth?” Finally, when applying the framework, it should be acknowledged that each country has its specific circumstances and the framework can therefore be applied in both the developed world as well as in emerging economies.

The characteristics of the tourism sector make that it may contribute to greater inclusion in developed as well as developing countries. Though most of the barriers to increased inclusion are grounded in long-standing causes including economic, cultural, and political conditions, the proposed framework can nevertheless be applied by tourism policymakers and researchers to focus on mitigating the effects of these root causes and identifying the constraints that hinder the path to a more inclusive tourism sector. It contributes to the understanding of tourism planning in the context of an inclusive growth strategy by providing a tool to guide evidence-based decision making regarding tourism development issues by the government, tourism policymakers and development agencies and provide guidance in formulating effective tourism policies. The systematic approach acknowledges the value of both qualitative as well as quantitative input for the understanding of constraints concerning equal access and outcome of tourism opportunities. The diagnostic developed in this study can provide an opportunity for future empirical research and conduct case studies to test the framework in different contexts including in countries that are grappling with limited access to reliable quantitative data.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions. The author would also like to thank Rene van der Duim, Karin Peters, Jeroen Klomp, Hannah Messerli and Joseph Cheer for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Martine Bakker http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6145-2893

References

- Alam, M. S., & Paramati, S. R. (2016). The impact of tourism on income inequality in developing economies: Does Kuznets curve hypothesis exist? Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 111–126.

- Ali, I., & Son, H. H. (2007). Measuring inclusive growth. Asian Development Review, 24(1), 11–31.

- Ankomah, P. K. (1991). Tourism skilled labor: The case of sub-Saharan Africa. Annals of Tourism Research, 18(3), 433–442.

- Ashley, C., Roe, D., & Goodwin, H. (2001). Pro-poor tourism strategies: Making tourism work for the poor: A review of experience. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Asian Development Bank. (2010). Indonesia critical development constraints. Manila: Joint ADB-ILO and IDB report.

- Badulescu, D., Giurgiu, A., Istudor, N., & Badulescu, A. (2015). Rural tourism development and financing in Romania: A supply-side analysis. Agricultural Economics-Zemědělská ekonomika, 61(2), 72–80.

- Bakker, M., & Messerli, H. R. (2017). Inclusive growth versus pro-poor growth: Implications for tourism development. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(4), 384–391.

- Balakrishnan, R., Steinberg, C., & Syed, M. M. H. (2013). The elusive quest for inclusive growth: Growth, poverty, and inequality in Asia. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Baum, T., & Thompson, K. (2007). Skills and labour markets in transition: A tourism skills inventory of Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and Uzbekistan. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 45(2), 235–255.

- Benur, A. M., & Bramwell, B. (2015). Tourism product development and product diversification in destinations. Tourism Management, 50, 213–224.

- Bieger, T., & Wittmer, A. (2006). Air transport and tourism—perspectives and challenges for destinations, airlines and governments. Journal of Air Transport Management, 12(1), 40–46.

- Blake, A. (2008). Tourism and income distribution in East Africa. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(6), 511–524.

- Blau, J. R., & Blau, P. M. (1982). The cost of inequality: Metropolitan structure and violent crime. American Sociological Review, 47(1),114–129.

- Bourguignon, F., & Chakravarty, S. R. (2003). The measurement of multidimensional poverty. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 1(1), 25–49.

- Britton, S. G. (1982). The political economy of tourism in the third world. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(3), 331–358.

- Buultjens, J., Brereton, D., Memmott, P., Reser, J., Thomson, L., & O’rourke, T. (2010). The mining sector and indigenous tourism development in Weipa, Queensland. Tourism Management, 31(5), 597–606.

- Campos-Soria, J. A., Garcia-Pozo, A., & Sánchez-Ollero, J. L. (2015). Gender wage inequality and labour mobility in the hospitality sector. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 49, 73–82.

- Carlisle, S., Kunc, M., Jones, E., & Tiffin, S. (2013). Supporting innovation for tourism development through multi-stakeholder approaches: Experiences from Africa. Tourism Management, 35, 59–69.

- Carrillo-Hidalgo, I., & Pulido-Fernández, J. I. (2016). Is the financing of tourism by international financial institutions inclusive? A proposal for measurement. Current Issues in Tourism. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1260529

- Cole, S. (2006). Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 14(6), 629–644.

- Croes, R., & Rivera, M. (2016). Poverty alleviation through tourism development: A comprehensive and integrated approach. Oakville: Apple Academia Press.

- Crouch, G. I. (1994). The study of international tourism demand: A review of findings. Journal of Travel Research, 33(1), 12–23.

- de Haan, A., & Thorat, S. (2013). Inclusive growth: More than safety nets. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

- Deveaux, M. (2000). Conflicting equalities? Cultural group rights and sex equality. Political Studies, 48(3), 522–539.

- Dieke, P. (1989). Fundamentals of tourism development: A third world perspective. Hospitality Education and Research Journal, 13(2), 7–22.

- Dieke, P. (2003). Tourism in Africa’s economic development: Policy implications. Management Decision, 41(3), 287–295. doi: 10.1108/00251740310469468

- Ferreira Freire Guimarães, C. R., & Silva, J. R. (2016). Pay gap by gender in the tourism industry of Brazil. Tourism Management, 52, 440–450.

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Pritchard, A., Segovia-Pérez, M., Morgan, N., & Villacé-Molinero, T. (2015). Tourism gender research: A critical accounting. Annals of Tourism Research, 52, 87–103.

- Forstner, K. (2004). Community ventures and access to markets: The role of intermediaries in marketing rural tourism products. Development Policy Review, 22(5), 497–514.

- García-Pozo, A., Campos-Soria, J. A., Sánchez-Ollero, J. L., & Marchante-Lara, M. (2012). The regional wage gap in the Spanish hospitality sector based on a gender perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(1), 266–275.

- Gentry, K. M. (2007). Belizean women and tourism work: Opportunity or impediment? Annals of Tourism Research, 34(2), 477–496.

- Ghaderi, Z., Saboori, B., & Khoshkam, M. (2017). Does security matter in tourism demand? Current Issues in Tourism, 20(6), 552–565.

- Graci, S., & Dodds, R. (2010). Sustainable tourism in island destinations. London: Earthscan.

- Hall, C. M. (1994). Tourism and politics: Policy, power and place. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hall, D. (2004). Rural tourism development in Southeastern Europe: Transition and the search for sustainability. International Journal of Tourism Research, 6(3), 165–176.

- Hampton, M. P., & Jeyacheya, J. (2012). Tourism and inclusive growth in small island developing states—a study for the World Bank. Canterbury: Centre for Tourism in Islands and Coastal Areas.

- Hampton, M. P., Jeyacheya, J., & Long, P. H. (2017). Can tourism promote inclusive growth? Supply chains, ownership and employment in Ha Long Bay, Vietnam. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(2), 359–376.

- Hasmath, R. (2015). Inclusive growth, development and welfare policy: A critical assessment. London: Routledge.

- Hausmann, R., Rodrik, D., & Velasco, A. (2005). Growth diagnostics. Boston: Center for International Development, Harvard University.

- Henderson, J. (2009). Transport and tourism destination development: An Indonesian perspective. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9(3), 199–208.

- Holden, A., & Burns, P. (1995). Tourism: A New perspective. New York: Simon & Shuster International Group.

- Holden, A., Sonne, J., & Novelli, M. (2011). Tourism and poverty reduction: An interpretation by the poor of Elmina, Ghana. Tourism Planning & Development, 8(3), 317–334.

- Hu, W., & Wall, G. (2005). Environmental management, environmental image and the competitive tourist attraction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13(6), 617–635.

- Ianchovichina, E., & Lundstrom-Gable, S. (2012). What is inclusive growth? Commodity prices and inclusive growth in low-income countries. In R. Arezki, C. Patillo, M. Quintyn, & M. Zhu (Eds.), Commodity prices and inclusive growth in low-income countries (pp. 147–160). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Inskeep, E. (1991). Tourism planning: An integrated and sustainable development approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Jenkins, C. L., & Henry, B. (1982). Government involvement in tourism in developing countries. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(4), 499–521.

- Karanasios, S., & Burgess, S. (2008). Tourism and internet adoption: A developing world perspective. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(2), 169–182.

- Klasen, S. (2010). Measuring and monitoring inclusive growth: Multiple definitions, open questions and some constructive proposals. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Kolesnikova, N., & Liu, Y. (2011). Gender wage gap may be much smaller than most think. The Regional Economist, 19, 14–15.

- Koo, T. T., Wu, C.-L., & Dwyer, L. (2012). Dispersal of visitors within destinations: Descriptive measures and underlying drivers. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1209–1219.

- Kristal, T., Cohen, Y., & Navot, E. (2018). Benefit inequality among American workers by gender, race, and ethnicity, 1982–2015. Sociological Science, 5, 461–488.

- Kubickova, M. (2017). The impact of government policies on destination competitiveness in developing economies. Current Issues in Tourism. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2017.1296416

- Kundur, S. (2012). Development of tourism in Maldives. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 2(4), 1–5.

- León, Y. M. (2007). The impact of tourism on rural livelihoods in the Dominican Republic’s coastal areas. The Journal of Development Studies, 43(2), 340–359.

- Li, H., Chen, J. L., Li, G., & Goh, C. (2016). Tourism and regional income inequality: Evidence from China. Annals of Tourism Research, 58, 81–99.

- Lipscomb, A. J. (1998). Village-based tourism in the Solomon Islands: Impediments and impacts. In E. Laws, B. Faulkner, & G. Moscardo (Eds.), Embracing and managing change in tourism: International case studies (pp. 91–119). London: Routledge.

- Liu, A., & Wall, G. (2006). Planning tourism employment: A developing country perspective. Tourism Management, 27(1), 159–170.

- Long, V. H., & Kindon, S. L. (1997). Gender and tourism development in Balinese villages. In T. Sinclair (Ed.), Gender, Work and Tourism (pp. 99–128). London: Routledge.

- Loureiro, S. M. C., & Sarmento Ferreira, E. (2015). Tourism destination competitiveness in São Tomé and Príncipe. Anatolia, 26(2), 217–229.

- Mahadevan, R., & Suardi, S. (2017). Panel evidence on the impact of tourism growth on poverty, poverty gap and income inequality. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–12. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2017.1375901

- McKercher, B. (1993). Some fundamental truths about tourism: Understanding tourism’s social and environmental impacts. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(1), 6–16.

- McKercher, B., & Chon, K. (2004). The over-reaction to SARS and the collapse of Asian tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 716–719.

- McKinley, T. (2010). Inclusive growth criteria and indicators: An inclusive growth index for diagnosis of country progress (Working Paper 14). Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Meera, S. (2014). Challenges of women entrepreneurs: With specific reference to tourism industry. International Journal (Toronto, Ont.), 1(1).

- Melamed, C., Hartwig, R., & Grant, U. (2011). Jobs, growth and poverty: What do we know, what don’t we know, what should be know?. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Meyer, D. (2007). Pro-poor tourism: From leakages to linkages. A conceptual framework for creating linkages between the accommodation sector and ‘poor’ neighbouring communities. Current Issues in Tourism, 10(6), 558–583.

- Mitchell, J., & Ashley, C. (2010). Tourism and poverty reduction: Pathways to prosperity. London: Earthscan.

- Mustika, P. L. K., Stoeckl, N., & Farr, M. (2016). The potential implications of environmental deterioration on business and non-business visitor expenditures in a natural setting: A case study of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Tourism Economics, 22(3), 484–504.

- Ndabeni, L., & Rogerson, C. M. (2005). Entrepreneurship in rural tourism: The challenges of South Africa’s Wild Coast. Africa Insight, 35(4), 130–141.

- Ngepah, N. (2017). A review of theories and evidence of inclusive growth: An economic perspective for Africa. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 24, 52–57.

- Nuntsu, N., Tassiopoulos, D., & Haydam, N. (2004). The bed and breakfast market of Buffalo City (BC), South Africa: Present status, constraints and success factors. Tourism Management, 25(4), 515–522.

- Papatheodorou, A., & Zenelis, P. (2013). The importance of the air transport sector for tourism. In C. Tisdell (Ed.), Handbook of tourism economics: Analysis, new applications, and case studies (pp. 207–224). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company.

- Pinar, M., McCuddy, M. K., Birkan, I., & Kozak, M. (2011). Gender diversity in the hospitality industry: An empirical study in Turkey. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(1), 73–81.

- Ranieri, R., & Ramos, R. A. (2013). Inclusive growth: Building up a concept. Working Paper 104. Brasília: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth.

- Rao, M. (2002). Challenges and issues for tourism in the South Pacific island states: The case of the Fiji islands. Tourism Economics, 8(4), 401–429.

- Rauniyar, G., & Kanbur, R. (2010). Inclusive growth and inclusive development: A review and synthesis of Asian Development Bank literature. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 15(4), 455–469.

- Richter, L. K., & Waugh, W. L. (1986). Terrorism and tourism as logical companions. Tourism Management, 7(4), 230–238.

- Roberts, S., & Tribe, J. (2005). Exploring the economic sustainability of the small tourism enterprise: A case study of Tobago. Tourism Recreation Research, 30(1), 55–72.

- Rodrik, D. (2003). Introduction: What do we learn from country narratives. In D. Rodrik (Ed.), In search of prosperity: Analytic narratives on economic growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rodrik, D. (2007). Doing growth diagnostics well. Dani Rodrik’s weblog. Retrieved from http://rodrik.typepad.com/dani_rodriks_weblog/2007/11/doing-growth-di.html

- Rogerson, C. M. (2004). Transforming the South African tourism industry: The emerging black-owned bed and breakfast economy. GeoJournal, 60(3), 273–281.

- Saad-Filho, A. (2010). Growth, poverty and inequality: From Washington consensus to inclusive growth. New York: United Nations.

- Sandbrook, C., & Adams, W. M. (2012). Accessing the impenetrable: The nature and distribution of tourism benefits at a Ugandan national park. Society & Natural Resources, 25(9), 915–932.

- Schellhorn, M. (2010). Development for whom? Social justice and the business of ecotourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(1), 115–135.

- Scheyvens, R. (2002). Tourism for development: Empowering communities. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Scheyvens, R., & Biddulph, R. (2017). Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies, 1–21. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/14616688.2017.1381985

- Sen, A. (1993). Capability and well-being. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 30–53). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Sen, A., & Kirkpatrick, C. (2011). A diagnostics approach to economic growth and employment policy in low income economies: The case of Kosovo. Journal of International Development, 23(1), 132–154.

- Shackley, M. (1994). The land of Lō, Nepal/Tibet: The first eight months of tourism. Tourism Management, 15(1), 17–26.

- Sharma, A., & Upneja, A. (2005). Factors influencing financial performance of small hotels in Tanzania. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 17(6), 504–515.

- Sirima, A., & Backman, K. F. (2013). Communities’ displacement from national park and tourism development in the Usangu plains. Tanzania. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(7–8), 719–735. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.785484

- Sofield, T. H. (1993). Indigenous tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 20(4), 729–750.

- Spenceley, A. (2008). Local impacts of community-based tourism in Southern Africa. In A. Spenceley (Ed.), Responsible tourism: Critical issues for conservation and development (pp. 159–187). London: Earthscan.

- Subbarao, P. S. (2008, May 15–17). A study on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Indian tourism. Paper presented at the Conference on Tourism in India—Challenges Ahead, Kerala.

- Thapa, B. (2012). Soft-infrastructure in tourism development in developing countries. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1705–1710.

- Thompson, A. (2011). Terrorism and tourism in developed versus developing countries. Tourism Economics, 17(3), 693–700. doi: 10.5367/te.2011.0064

- Thompson, C., O’Hare, G., & Evans, K. (1995). Tourism in the Gambia: Problems and proposals. Tourism Management, 16(8), 571–581.

- Tosun, C. (2000). Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management, 21(6), 613–633.

- Tosun, C., Timothy, D. J., & Öztürk, Y. (2003). Tourism growth, national development and regional inequality in Turkey. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 11(2–3), 133–161.

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable development goals. Washington, DC: Author.

- UNWTO, & ILO. (2014). Measuring employment in the tourism industries—guide with best practices (UNWTO Ed.). Madrid: Author.

- USAID. (2014). Bangladesh inclusive growth diagnostic. Washington, DC: Author.

- Van der Duim, R., Peters, K., & Akama, J. (2006). Cultural tourism in African communities: A comparison between cultural manyattas in Kenya and the cultural tourism project in Tanzania. In M. K. Smith & M. Robertson (Eds.), Cultural tourism in a changing world. Politics participation and (re)presentation (pp. 104–123). Toronto: Channel View Publications.

- Wilson, S., Fesenmaier, D. R., Fesenmaier, J., & Van Es, J. C. (2001). Factors for success in rural tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 40(2), 132–138.

- World Bank. (2011). East Java growth diagnostic: Identifying the constraints to inclusive growth in Indonesia’s second-largest province. Washington, DC: Author.

- World Bank. (2016). Systematic country diagnostic for eight small pacific island countries: Priorities for ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity. Washington, DC: Author.

- Zhang, A., Zhong, L., Zxu, Y., Wang, H., & Dang, L. (2015). Tourists’ perception of haze pollution and the potential impacts on travel: Reshaping the features of tourism seasonality in Beijing, China. Sustainability, 7(3), 2397–2414.