ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the potential of immigrant tourism entrepreneurs to contribute to tourism development and to the goals of regional tourism policy through the creation of new paths of development. Based on qualitative interviews in the county of Gävleborg in Sweden, the paper contributes to understanding the role of immigrant entrepreneurs in the context of public tourism development efforts in a rural region characterized by primary resource based and manufacturing industries. The findings suggest that the strategies and agencies of several immigrant entrepreneurs are in line with the public regional development efforts to achieve new touristic products, growth of foreign visitor numbers and increased co-operation among tourism stakeholders. The paper also highlights the barriers faced by the immigrant entrepreneurs and regional tourism development actors in their efforts to increase professionalization and co-operation among local stakeholders. Finally, we argue that if the potential for immigrant tourism entrepreneurs to contribute with external networks and new knowledge for tourism development should be realised, public efforts to stimulate networking between tourism firms and with other business sectors need to be stable and long term.

Introduction

Tourism is often suggested to be vital for rural development, contributing to the transition from a primary sector into a service-based economy (Carson, Carson, & Lundmark, Citation2014; Müller, Citation2013; Williams & Hall, Citation2000). If tourism is to really benefit economic growth in lagging rural areas, increased innovation and development of new touristic products is needed, though (Aqueveque & Bianchi, Citation2017).

The ambitious goals of the First National Tourism Strategy in Sweden of doubling the number of tourists and turnaround of the industry by 2020 and its emphasis on increasing foreign visitor numbers (Svensk Turism, Citation2010) have impacted upon regional and local tourism policies (Larsson & Lindström, Citation2015). As a means to realize these policies, government and EU funded regional tourism development projects have been carried out in many areas previously lacking touristic traditions (Müller & Brouder, Citation2014).

In rural regions in northern and central Sweden, a growing number of small-scale rural tourism firms are run by entrepreneurs that have moved there from abroad to fulfil aspirations of a new lifestyle (Carson, Carson, & Eimermann, Citation2017). So far, little research has addressed these in-migrated rural tourism entrepreneurs. The studies by Carson and Carson (Citation2017) and Eimermann (Citation2016) highlight their contribution in terms of introducing new ideas, skills and networks, while at the same time pointing to obstacles for a broader impact on rural development due to, e.g. limited communication with local stakeholders. The in-migration of foreign people with aspirations to develop tourism in local areas with no or few previous experiences of tourism development is a challenge in many ways. This is particularly evident in regions historically characterized by primary industries and large-scale manufacturing plants, and hence weak traditions of small-scale entrepreneurship and self-employment. These challenges that new entrepreneurs encounter and the ways in which public policy meets these entrepreneurs may be conceptualized through an evolutionary economic geography (EEG) approach to tourism development (Anton Clavé & Wilson, Citation2017; Strambach & Halkier, Citation2013). By way of applying the EEG concepts of path dependency and path creation, this paper contributes to understanding the role of foreign immigrant tourism entrepreneursFootnote1 in the context of public efforts to spur tourism development in a rural region.

The overall aim of this paper is to investigate the potential of immigrant tourism entrepreneurs in the contribution to tourism development in rural areas and to the goals of regional tourism policy through the creation of new paths of development. By way of applying the EEG concepts of path dependency and path creation, the study seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the role of immigrant tourism entrepreneurs in the context of public efforts to spur tourism development in a region characterized by declining manufacturing industry.

Research questions guiding this research are:

What are the expectations from public actors towards immigrant entrepreneurs?

What are the business strategies of immigrant entrepreneurs in relation to business development and internationalization?

What are the experiences of immigrant entrepreneurs in terms of collaboration and networking?

The conceptual framework of this study embraces issues of path dependency and path creation, tourism destination development and immigrant tourism entrepreneurship.

Path dependence and path creation

The concept of path dependence, in its broadest sense meaning “history matters”, originated in research on technology evolution and historical and institutional economics (Arthur, Citation1989; David, Citation1985). It explains how a set of decisions in any given circumstance is limited by decisions made in the past, and how institutions thus are self-reinforcing (Gill & Williams, Citation2011). Adding a spatial dimension, approaches within EEG have applied the concept of path dependency to understand aspects of regional development (Boschma & Martin, Citation2010). Here, it illustrates the influence of established industrial structures, its institutions and social networks of powerful actors and how negative lock-in effects can occur when these are strong enough to reinforce traditional industrial structures at the cost of new, innovative ideas (Strambach & Halkier, Citation2013). Grabher (Citation1993) identified three components of lock-in: functional (long-standing exchange relations and networks hindering the identification and mobilization of external resources), cognitive (through shared world view, common norms, social cohesion and “groupthink” preventing bridging relationships), and political (through rigid politico-administrative systems and cooperative formal and informal relations between industries and public stakeholders).

So far, only few studies have applied the concept of path dependence in tourism contexts (Anton Clavé & Wilson, Citation2017). Brouder (Citation2014) illustrates how recent research linking EEG and tourism issues has addressed either path dependence in established tourism destination regions or co-evolution within complex regional systems including also non-tourism development paths. The study by Larsson and Lindström (Citation2015) is one of few examples of the latter. Focusing on the interrelations between the leisure boat manufacturing and emerging tourism sector on Sweden’s west coast, they apply the concept of path dependence to understand possibilities and obstacles for tourism development in a region dominated by manufacturing industry.

While path dependency approaches focus on post hoc explanations of e.g. regional economic development, path creation concerns the real-time effects of human agency (Gill & Williams, Citation2014). Innovation and entrepreneurship are key concepts related to path creation, highlighting the potential of entrepreneurs to lead and operationalize visions of new pathways (Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013; Gill & Williams, Citation2014). Entrepreneurial efforts to mobilize a collective in the creation of new paths through “mindful deviation” from existing structures and development trajectories will probably meet resistance and inertia, though (Gill & Williams, Citation2014).

Further, the impact of efforts to stimulate entrepreneurship and small business development in rural areas with traditions of heavy manufacturing industries are dependent not only on ambitions and capacity of individual entrepreneurs and business networks (Copus, Dubois, & Hedström, Citation2011; Huggins & Johnston, Citation2009) but also on local cultures and image (Heldt Cassel, Citation2008).

Tourism destination development

Entrepreneurship and innovation capacity are also central issues in research on tourism destination development; the general notion being that the attractiveness of tourism destinations is determined by their ability to stimulate tourists with something new (Hjalager, Citation2010). Innovations are thus a key to success and survival in a highly competitive global tourism market (Aqueveque & Bianchi, Citation2017; Hjalager et al., Citation2008; Volo, Citation2006). Rønningen (Citation2010) noted that innovation capacity depends on collaborative structures and that co-operation strengthens innovation abilities. The existence of informal entrepreneurial networks characterized by openness, trust, and willingness to share knowledge and resources are seen as key components of successful tourism destinations (Gibson, Citation2006; Huijbens, Hjalager, Björk, Nordin, & Flagestad, Citation2009; Scott, Baggio, & Cooper, Citation2008). Another crucial feature put forward by Huijbens et al. (Citation2009) is a growing global outreach. The actors involved are seen to increasingly invite knowledge, capital, and ideas into the system and link to larger communities for marketing and resource purposes. Kaján and Saarinen (Citation2014) discuss how forces constructing and transforming destinations are increasingly non-local, and how adaptive responses to negative path dependency can result in grasping new opportunities and creating new development paths. One example of such a process could be the influx of new ideas and entrepreneurs with extra-local networks and connections.

Besides collaboration and networking within the tourism sector itself, the relations to other business sectors are crucial. If tourism should be able to contribute to broader regional development, it needs strong linkages to the surrounding economy (Larsson & Lindström, Citation2015). In regions dominated by traditional, declining branches, increased co-operation and networking between tourism entrepreneurs and business leaders from other sectors thus appears crucial for breaking path dependency (Abbasian, Citation2016). In rural areas, the preconditions for small firm development are also highly dependent on contextual and place-based factors related to rurality. In small rural communities, the ways of networking and the mobilizing of social capital for developing and sustaining business interactions are found to be different from urban regions (Dubois, Citation2016). Furthermore, in rural regions with strong traditions and local cultures of large employers and a recent history of economic decline in manufacturing, the rurality and the economic path of industry relations together form the contextual framework in which future development is imagined by regional stakeholders (Heldt Cassel, Citation2008; Heldt Cassel & Pashkevich, Citation2011).

Strategic efforts by local and regional public tourism actors are of significant importance to stimulate tourism development (Hall, Citation2008; Huijbens et al., Citation2009). In many areas lacking touristic traditions, government and EU funded regional tourism development projects have been carried out (Müller & Brouder, Citation2014). By way of offering support for tourism firms in product development and stimulating international marketing and the establishment of destination management organisations (DMOs), these have aimed at contributing to regional economic growth (Müller & Brouder, Citation2014). The role of the public sector in enhancing new forms of collaboration and alliances, by way of offering arenas for tourism entrepreneurs and other local and regional tourism stakeholders to meet, has especially been emphasized (Hall, Citation2008; Hjalager, Citation2010; Huijbens et al., Citation2009).

Tourism destination development implies a commoditization of places with different actors with different interests, though, which may complicate the possibility of increased co-operation due to various local and regional stakeholders holding disparate view-points (Aqueveque & Bianchi, Citation2017; Førde, Citation2014). As Viken and Granås (Citation2014, p. 9) claim, different directions in tourism destination development are moulded together in environments marked by “tensions and conflicts as well as by fruitful concurrences and strong alliances”. For example, public regional initiatives to stimulate professionalization and growth may collide with alternative aims regarding tourism development (Førde, Citation2014). Small-scale, hobby-based local firms might be concerned with avoiding the place being “too touristy” (Forde, Citation2014, p. 164) and guided by values of local cohesion and commonality, rather than being focused on increased tourism volumes.

Research linking tourism policy to path dependence and path creation has mainly focused on established tourism destinations (Gill & Williams, Citation2014; Pastras & Bramwell, Citation2013). Policy agencies have here been shown to be path dependent, while on the other hand path creation can occur when these agencies develop in new and less expected directions. Collaborating entrepreneurs, both privately and publically based, are crucial in these processes (Gill & Williams, Citation2014).

Immigrant tourism entrepreneurs in rural areas

Research on international entrepreneurial tourism migration has often focused on life style migrants moving to warmer, amenity-rich destinations (Lardiés, Citation1999; Stone & Stubbs, Citation2007; Williams & Hall, Citation2000). However, notable exceptions are Eimermann's study of Dutch rural tourism entrepreneurs in Swedish Värmland (Eimermann, Citation2016), and the study of Western European winter tourism entrepreneurs in Northern Sweden by Carson et al. (Citation2017), both of which focused on northern “cold-weather”, “low-amenity” locations where tourism remains quite undeveloped. Lifestyle tourism entrepreneurs are often described as lacking business-oriented strategies and goals and as reluctant to employ any workforce other than their family and friends (Müller & Jansson, Citation2007). “Consumptive” rather than economic goals are seen to dominate their agenda (Müller, Citation2013). However, the distinction between pure consumptive versus productive goals has been criticized as too rigid. In their study of international tourism entrepreneurs in Northern Sweden, Carson et al. (Citation2017) found the aspirations to be diverse, ranging from consumption-driven “non-entrepreneurs” to growth-driven business entrepreneurs.

A number of key characteristic qualities make lifestyle migrants an especially promising population in terms of their ability to contribute to tourism development and new path creation in rural areas characterized by declining traditional industries. The lifestyle entrepreneurs bring with them “fresh” eyes. Their appreciation of local amenities, which has often been the motivation for migrating (Iversen & Jacobsen, Citation2017), suggests they have the potential to imagine local natural, cultural, and built capital as tourism products and recognize opportunities that local people might be “blind” to (Bosworth & Farrell, Citation2011; Carson, Cleary, de la Barre, Eimermann, & Marjavaara, Citation2016). Lifestyle migrant tourism entrepreneurs contribute with new knowledge, resources, and contacts, and have the potential to act as brokers between disconnected networks in their former home countries and new settings (Burt, Citation2002; Carson et al., Citation2017; Stam, Citation2010). A significant marketing and distribution potential is embodied in linking such networks (Carson et al., Citation2016). However, Carson and Carson (Citation2017) noted that the impact of immigrated tourism entrepreneurs on local tourism development is limited by the lifestyle migrants’ weak local social ties.

This study addresses two gaps in the literature: first, it focuses on tourism development in a region characterized by traditional primary resource based and manufacturing industry. Second, it links the concepts of immigrant tourism entrepreneurship with regional tourism policy issues. In this context, issues of path dependency and path creation are suggested crucial, and the study contributes to nuancing the role of immigrant tourism entrepreneurs in this process.

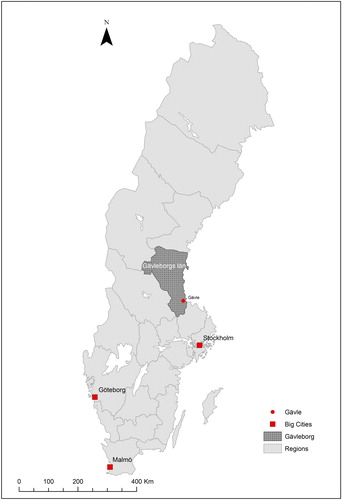

The regional context

The county of Gävleborg is a rural region in the central eastern part of Sweden (). It has 285,000 inhabitants and an area of 18,000 km2 (Region Gävleborg, Citation2017). Gävleborg is Sweden's most forested region, with an afforestation of almost 90% of its land area, but there are also areas of lively countryside with small-scale farming and small businesses (Statistics Sweden, Citation2017). Gävleborg has the lowest level of formal education among all counties in Sweden and the highest unemployment rate (Näringslivets ekonomifakta, Citation2017). Despite restructuring processes and a down-turn in recent decades, manufacturing and extraction industries still dominate the business sector, and the share of the workforce employed in manufacturing is the highest in Sweden, where a handful of firms in materials technology and paper pulp industry are the largest single private employers (Region Gävleborg, Citation2017).

Historically, single-industry communities have been a dominant feature of the rural areas in Gävleborg (Vallström, Citation2014). Such communities are often characterized by a strong collective identity and tradition of informal co-operation, especially regarding social issues. These collective values are often contrasted to entrepreneurial values of individual success and growth. Facing decline of traditional industries, cognitive aspects can thus also influence the preconditions for a changed business structure (Vallström, Citation2014).

In the light of recent restructuring processes and lingering structural problems, it is interesting to use this region as a case study of tourism destination development.

The region of Gävleborg is not as developed in terms of tourism destinations and attracts considerably lower numbers of domestic and foreign visitors than most other Swedish regions. In 2017, the number of foreign commercial guest nights reached 57,000 during the summer season, compared to 3,27,000 in the neighbouring country of Dalarna which has a similar population size and similar geographical features (). However, there has been a considerable increase in recent years. Recent growth in international tourism went hand in hand with an increase in European tourism entrepreneurs who moved to the area and started up accommodation and guided tour businesses, which makes it interesting to further explore the potentials and challenges connected to this development (Interviews with officials in Region Gävleborg, Citation2017).

Table 1. Development of commercial guest nights 2010–2017.

Gävleborg is often depicted as a transit route region (Leiper, Citation1979), where tourists on their way to more developed destination regions like Dalarna or Lapland stop over for one or two nights (Graffman, Citation2012). According to a survey, the main general tourist attractions of the county are nature activities and wildlife watching (bears, elks, and wolves) and the largest single destinations are, besides the main towns of Gävle and Hudiksvall, two zoos/leisure parks (CMA Research, Citation2012).

In 2009, a regional tourism development strategy was formulated for Gävleborg, which focused on the potential of increased foreign incoming tourism and identified a number of continental European countries as prioritized markets (Region Gävleborg, Citation2009).

In recent decades, there has been an increase in in-migration of people from other Western European countries, such as the Netherlands and Germany, as has been the case in other Swedish rural regions. Many of them are moving to Sweden for lifestyle reasons and as part of a counter urbanization process and a large share of them are starting up new businesses within tourism and related sectors (Eimermann, Citation2016). According to the information from representatives for the municipalities and regional authority of Gävleborg, there has been an increase of European immigrants taking over or setting up accommodation firms in the region since the beginning of the 2000s. From the year 2008 to 2012, some of the municipalities actively recruited in-migrants via the annual Emigration Expo in the Netherlands, and several of these became rural tourism entrepreneurs (Interview with municipal official, 2017).

Methodology and data

This paper presents the results from an explorative qualitative study with immigrant tourism entrepreneurs and with municipal and regional officials in the region of Gävleborg, Sweden. 11 in-depth interviews with 15 immigrant tourism entrepreneurs were conducted. These interviews lasted between 75 and 120 min and took place in the informants’ homes or business premises. Interviews with couples lasted longer than those with one informant. All of the interviews were conducted by the same researcher between March and May of 2016.

The study is based on a qualitative research design with semi-structured interviews (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2012; Valentine, Citation2005). The interview guide consisted of four parts. Introducing questions dealt with the informants’ background, previous work experience, and motives for moving to the area and setting up or taking over the business. This was followed by questions about the firm's development of products and services, marketing strategies, and customers. The interview guide concluded with themes of co-operation and networking with local, regional and external actors, and finally the entrepreneurs’ plans for the future. One interview was conducted in German and all the others in Swedish. All interviews were audio recorded using a digital voice recorder and then transcribed verbatim.

In addition, the tourism development officer at the regional authority and a municipal official involved in the recruitment of European in-migrants were interviewed. Questions centred around public strategical and operational efforts to enhance regional destination development and the expectations towards and experiences of immigrant entrepreneurs in this context. Further, informal conversations were held with key municipal officers in charge of tourism/business matters in all of the ten municipalities of Gävleborg. Lastly, public documents like tourism development strategies, project plans, and international market analyses were reviewed.

Sampling

The migrant informants were interviewed as part of a broader study of immigrant tourism entrepreneurship within the accommodation sector in the county of Gävleborg. The sample used for this paper is limited to immigrants from Europe. This is motivated by the expectations from the regional tourism development actor towards these immigrants to contribute to increased foreign visitor numbers from European countries and to co-operation among local tourism firms (Region Gävleborg, Citation2014).

Potential participants were identified with the help of key officer representatives in charge of tourism/business matters within the municipalities in the county. In total, 14 accommodation firms whose owners had immigrated from Europe were named. When selecting firms to contact via phone, we aimed for variation in terms of accommodation types, countries of origin of the owner, and geographical location within the county. All entrepreneurs who were contacted were willing to take part in the study. Cases were gathered until saturation was reached at the point of 11 firms ().

Table 2. Characteristics of immigrant tourism entrepreneur informants.

Sample

The studied firms were located in different rural parts of the county of Gävleborg. In 4 out of 11 firms, both firm owners (couples) were interviewed; the total number of interviewees thus reached 15 (7 women and 8 men). Nine informants had moved to Sweden from the Netherlands, three from Switzerland, and one each from Belgium, Germany, and Italy. Most entrepreneurs combined their accommodation (hotel, bed and breakfast, youth hostel, and/or camping) with additional activities like fishing or bear- and elk-watching tours, handicrafts/arts, restaurant/food experiences, or wellness.

All of the informants had moved directly to their current location when they moved to Sweden. They had migrated between 3 and 11 years prior to the interview (median: eight years), and most of the tourism firms had been taken over or set up in the same year as they arrived. The informants had typically moved to Sweden as couples with young and school-aged children and most of them were aged 40–55 at the time of the interview.

In 4 out of the 11 migrant firms, one or both owners had education and/or previous work experience from the tourism sector. In another six cases, the entrepreneurs had other relevant education/experience, for example in marketing, business administration, as self-employed, or from a field that they now offered as a service at their accommodation (such as wellness).

Typically, two persons (a couple) were employed in the tourism enterprise and four of the firms employed additional seasonal local work force. Thus, even though the firms were not large, most were businesses from which the immigrants made their living rather than run on a hobby basis.

Data analysis

A hermeneutical perspective constitutes the point of departure for the qualitative analysis of the interviews; that is, the interpretation and understanding of the informants’ experiences, strategies, and practices is central (Graham, Citation2005; Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, Citation2011). The analysis largely followed the qualitative analysis cycle suggested by Hennink et al. (Citation2011), which is characterized by an interplay between deductive and inductive strategies. The interview material was coded, and while some of the codes were derived from the research questions and from concepts and themes from the research literature, other codes were developed from the data itself. Thus these latter codes reflect themes that turned out to be important for the informants, but were not foreseen by the researchers as central aspects. Codes with similar characteristics were then grouped into meaningful categories, which enabled comparisons and the identification of patterns of similarities and differences. For the presentation of the results, all interviewees were given pseudonyms.

Findings and discussion

Expectations from public actors towards immigrant entrepreneurs

Two publically financed regional destination development projects were carried out in the county of Gävleborg in the period of 2011–2016, with the overall goal to strengthen the tourism industry and hence its contribution to regional growth and work places (Region Gävleborg, Citation2013). The projects aimed to increase the professionalization of the tourism industry and the quality of its products and services, and to enhance the possibilities for export ripe firms to reach out onto the international market (Region Gävleborg, Citation2013). Tourism firms in Gävleborg were described as small, offering low standard and lacking sufficient co-operation to realize growth and internationalization potential (Region Gävleborg, Citation2013). The projects offered support in product development, networking and international marketing, and a process of creating a new internationally orientated regional tourism brand was initiated.

Notably, one project goal was to stimulate knowledge transfer from immigrant tourism entrepreneurs to local tourism firm owners to enhance destination development. Immigrant tourism entrepreneurs from e.g. the Netherlands and Belgium who had settled in Gävleborg were depicted as carriers of important experiences and seen to practice a n entrepreneurship more focused on external relations than locals, thereby enhancing networking, co-operation, and common marketing (Region Gävleborg, Citation2014).“The project will co-operate with these entrepreneurs to canalize the positive aspects they can contribute with to the rest of the tourism industry” (Region Gävleborg, Citation2014, p. 3).

While the interviewed regional tourism developer claimed most local tourism firms are operated on a hobby basis and combined with other paid jobs, she described the immigrant entrepreneurs as more business oriented:

They [the immigrant tourism entrepreneurs] think more in terms of business, I think. At the same time as … it is not their primary … I mean they dońt move here to earn money. They have other driving forces to move here. But once they are here, I experience they are more entrepreneurial.

Further, from the side of the public actors, the immigrant tourism entrepreneurs were expected to contribute to the realization of the regional tourism development strategy and thus to new path creation. Compared to local firms, the in-migrants were perceived to pursue an entrepreneurship more in line with the policy goals related to internationalization of the customer base. While local firms were described as lacking high quality products rife for export, the profiles and offers of tourism firms operated by European immigrants were expected to comply with the demand from potential tourists from those same countries. Thus the immigrant entrepreneurs were expected to contribute to destination development both in terms of their own entrepreneurship, and in terms of co-operation and knowledge spill-over to local firms. This raises questions about the strategies and agencies of the immigrant entrepreneurs. In what ways do these correspond with the expectations from public tourism development actors? And which hindering factors can be identified, regarding the possible contribution of immigrant entrepreneurs to rural tourism development and new path creation?

Business strategies in relation to product development and internationalization

The commodification of natural resources—that is, making use of the forests and lakes for outdoor activities, animal watching, and fishing, but also using the silence and nature for relaxation and recovery—constitutes the main framework for observed business strategies among the interviewed tourism entrepreneurs. Thus the products based on nature cannot typically be characterized as new in terms of “never seen before”; rather, as we will illustrate, in terms of being offered in this region, adding new and different values and attracting new groups of customers.

New eyes on old resources

Viktor combines a B&B and camping accommodation with guided fishing and wildlife watching. Back in his former home country, he was the manager of a large camping firm. Since he set up the business in his new locality around 10 years ago, he has seen the number of guest nights increase substantially. In the remote rural area where he has settled, the population has been decreasing. Viktor represents an example of an in-migrant bringing a new, consumption-oriented perspective rather than a production-oriented perspective on natural resources. This enables him to recognize opportunities for local natural capital to turn into tourism products, of which local people might not be aware (Bosworth & Farrell, Citation2011).

In [the village] with a lot of older people, they said, ‘no, no, you are definitely not welcome with your tourists. We have managed and cared for these fishing waters for ages and do not want you and your business operation to take all the fish.’ They did not even realize that when talking sport fishing, it is normally a practice of catch-and-release you are talking about//Nowadays I have heard quite a few of the locals saying that they are happy that I settled here since I brought the village back on the map again. They had never thought it would be possible to do what I do …

This quote clearly puts forward the initial problems related to the introduction of new ideas in a context with different traditions and culture when it comes to how nature and the natural resources are perceived, interpreted, and used. By introducing new ways of looking at nature and natural resources, new ways of making business are developed, which was not previously considered possible.

Initially, Viktor's networks were closely related to his main leisure interest, namely fishing. The contacts he had in his former home country played an important role in the marketing and selling of his products in that market. He also advertised his packages in international fishing journals and visited tourism fairs in continental Europe. Co-operating with the public regional destination development project, his tourism firm was included in show tours for international tour operators and European TV-programs advertising nature experiences in Sweden. These tours were arranged by officers at the regional authority, as part of the international marketing efforts.

Most of the guests to his business come from his former home country. Only a few domestic Swedish tourists buy his products, which may be explained by the new way that Viktor packages fishing and nature experiences, which includes more staged and pre-organized fishing compared to what domestic fishing tourists are used to or are willing to pay for. While local tourism firms like camping sites might well be located close to fishing waters, it is not common to arrange guided fishing tours. Thus Viktor’s strategy for tourism product development seems more in line with the ambitions of increased refinement and export ripeness from the side of public tourism development actors.

New markets and the challenges of international marketing

The personal interest in, knowledge about, and networks within leisure fishing were also important assets for Lotta and Hugo when they bought their camping company around 10 years ago. Before moving to Sweden, they worked with marketing and in retail trade respectively. Today, they offer guided boat and mountain bike tours besides camping lots and cottages to rent. International marketing channels related to fishing are crucial for their product development. They regularly invite journalists from fishing journals in their former home country and other continental European countries, to be guided to the surrounding fishing waters before writing articles.

The case of Lotta and Hugo illustrates the importance of innovative strategies to reach new market segments (Hjalager, Citation2010). Before they took over the camping, it was operated on a hobby basis. The standard of cottages and sanitary facilities was simple and the guest nights rather few and concentrated to the main summer season. Upon increasing the accommodation standard and introducing new international marketing forms, the number of guests increased considerably, as did the share of foreign visitors and length of season.

The issue of quality of accommodation and food is important for Lotta and Hugo. They underline that several local accommodation sites offer very simple sanitary and sleeping facilities, which “doesn’t fit the foreign market”. Hence, their view is in line with the regional tourism policy, emphasizing the need for increased standard of local tourism products and services to meet international expectations. While local accommodation facilities are defined as too simple according to this discourse of tourism development, their standard might well be in line with other, community-based discourses of development, though. In these, small-scale nature-based tourism rather than increased volumes and internationalization might be aimed at (Førde, Citation2014). Given that the region of Gävleborg is not an established tourism destination, these latter discourses may even dominate. To reach legitimacy for a more economically oriented tourism development discourse would require breaking away from the dominant development trajectory of the tourism sector.

While several of the informant entrepreneurs mostly received international guests, others were mainly directed towards the domestic market. These did not collaborate with the regional tourism development actor to the same extent. Some of them were even critical towards the efforts of the regional authority officers to involve them in international marketing. Helena, who worked as an administrator in her former home country before she and her husband took over a Swedish camping eight years ago, is one example. The camping mainly attracts Swedish guests and Helena says:

Once we went to Gävle because they [the regional authority officers] said it was very interesting for us … A large tour operator from Europe had been invited, who wanted to rent accommodation. And they wanted a big camping … a large park … everything big! But tell us what you want first. Now we drove for 2½ hours there and 2½ hours back and sat there for three hours and it was nothing for us.

Thus not all migrant informants’ ambitions and strategies are in line with the policy goals of increased internationalization and tourism export. As Carson et al. (Citation2016) underline, lifestyle migrants in their entrepreneurship are driven by various combinations of lifestyle and business goals, ranging from pure lifestyle seekers opposing economic growth to more growth-driven entrepreneurs. This variety of motivations may contribute to explaining the different strategies in relation to international marketing.

Collaboration and networking: successes and failures

As mentioned earlier, the regional tourism development actors expected the immigrant entrepreneurs to contribute to increased collaboration and networking among local tourism firms, to enhance destination development. Most migrant informants actually pursued various strategies to achieve increased co-operation with and between local firms, but the outcomes were differing.

Path creation efforts

The case of Anders seems to constitute the most successful example. A few years ago, he and his partner established a B&B along with activities like nature tours and yoga courses in a village that had hitherto attracted few foreign tourists. Before migrating, Anders worked as a sales manager at a large international tourism firm. Several of the formal contacts he then had with tour operators from all over the world developed into relationships between friends, whom he now invites regularly to visit the B&B.

Anders sees a large potential in his new locality to attract both visitors seeking recovery and silence and those preferring a more active vacation, such as outdoor sports and wildlife watching. With the help of networks related to his pre-migration employment, Anders is now able to channel his newly gained knowledge about local conditions and attractions to relevant foreign markets. While the strategy to act as bridging nodes or brokers (Burt, Citation2002; Carson et al., Citation2016) linking the own business with foreign markets characterizes several of the informants, it is the way knowledge and resources gained from these networks have begun to intermingle with local actors that seems unique.

We invited everyone in [village] and around who was interested, to get some training in ‘What is tourism industry? What is product development, what is pricing, what is marketing?’ All that. And we have done that for two years, and from there some people came up to say `Well, I join. `I set up a firm, or you can hire me iń or so..//..One plays the fiddle, the other guides in the forest, goes fishing with our guests …

The village where Anders and his partner settled has experienced population decline in recent decades, following the loss of work places in the forestry and manufacturing sectors. These traditional branches have dominated industrial life in the village for centuries, and thus in the light of structural changes, there is an obvious risk of negative functional and cognitive lock-in effects attached to path dependency (Strambach & Halkier, Citation2013). Taking on the role of local innovators, Anders and his partner have proved alternative sources of income to be possible, and even inspired locals to set up tourism firms themselves. Hence, their agency seemingly has the potential to contribute to new path creation. This was confirmed by the regional tourism developer, who described how Anders and his partner “gather everyone around themselves, to build their own little village destination”.

Anders has been co-operating tightly with the regional tourism development projects, and especially profited from the meeting platforms arranged for networking with other tourism firms all over the county. The regional tourism developer emphasized that the tourism packages he arranged included firms across the landscape border, which was “unusual” and an “eye-opening for locals”. Thus, Anders’ strategies and agency clearly comply with the expectations from regional public actors towards immigrant entrepreneurs to act as inspirers and icebreakers in the regional tourism context, both in terms of business practices and networking.

Lack of collaborating traditions

However, most other migrant informants faced constraints in their efforts to co-operate with local tourism actors. Several of those mainly directed towards the domestic market had not taken part in the regionally arranged networking platforms focused on tourism export, but instead pursued various strategies to initiate local collaborations on their own. They perceived a lack of tradition and knowledge among local tourism firms about the benefits of co-operation. Some drew on their pre-migration work experiences from continental, more developed tourism destinations where, they claimed, the understanding of the need to co-operate is higher.

Eva and Mattias took over a camping company a few years ago. Back in their home country, they worked with business administration and as self-employed in the manufacturing sector respectively. They see large potential for tourism development in the region, but emphasize that the co-operation and trust between local tourism actors has to increase in order for the potential to be realized. Like several other informants, they point at the limited opening periods of touristic facilities—often centred on the month of July, the traditional peak for domestic tourism—as one central obstacle for further development:

Everybody is a little by themselves here; each one works in their area, but doesn't really look at what others are doing. We know a lot of people in the area, from the museum and other places. We try to explain what you could do together, but the interest is not that big// … We need to reach a point where we collaborate and if there is an attraction, the people that run it need to open it up when guests are coming to the camping, even outside of regular opening hours. People say, ‘there are no tourists coming here’, but of course if you don't try and work together you will not succeed.

The perceived lack of collaboration among tourism actors might be related to the relatively small size, dispersed structure and low degree of professionalization of the tourism sector in Gävleborg. As mentioned, dense networks and a spirit of “co-opetition” have been seen to characterize more developed tourist destinations in Scandinavia and elsewhere (Huijbens et al., Citation2009). A perceived resistance towards co-operation for the goal of professionalization could also be related to conflicting aims regarding tourism development (Førde, Citation2014). Historically, the rural areas of Gävleborg have been characterized by single-industry communities with a strong collective identity and social cohesion (Vallström, Citation2014). Tourism issues have mainly been related to recreation for locals and domestic visitors, and values like public access rather than commercialization and growth have been prevalent. From the perspective of economic growth achievement, these traditional values can result in negative cognitive lock-in effects, hindering the potential to grasp new development opportunities. From another perspective, though, such values might be seen as assets assuring a more sustainable social and ecological development (Vallström, Citation2014).

As Abbasian (Citation2016) claims, attitudes towards tourism among policy makers and business leaders in other branches constitute another crucial issue for the success or failure of tourism development. To resist prejudices and gain legitimacy, knowledge must be gained about tourism. There is a common notion among the migrant informants, noted in the interviews, that tourism is not regarded as a “real” business among representatives from traditional industries like the manufacturing sector. Similarly, the interviewed regional tourism developer stated that in people’s mind and talking, there is still a distinction made between “the business sector” on the one hand, and “tourism” on the other. According to path dependence theory, strong, long-standing social networks of powerful actors are centred around a region’s main industries (Larsson & Lindström, Citation2015). In Gävleborg, such networks can be expected to be related to the manufacturing industry sector, which has dominated the region for long. When these networks, though facing decline of the businesses they were built around, keep being self-reinforcing and inward-looking rather than boundary-spanning and welcoming new actors and ideas, there is an apparent risk of negative functional lock-in (Grabher, Citation1993).

Not only the migrant informants faced constraints in their collaboration efforts. Throughout the two regional destination development projects operated between 2011 and 2016, there was overt resistance from several local and regional public actors, especially against the efforts to unite the two landscapes in common DMOs, marketing and a new internationally orientated brand (Lindquist & Kempinsky, Citation2017). When the external project funding ended, the staff in charge of tourism issues at the regional authority was cut from five officers to one. The implementation process of the new brand was not completed. Local and regional public actors did not step in to continue financing and operating the project efforts to professionalize the tourism sector. Instead, other development priorities were again placed higher on the agenda. Path dependency related to the traditional industrial structure of the region was thus reflected also in local and regional development policies, i.e. in terms of political lock-in.

Conclusion

This paper has investigated the potential of immigrant tourism entrepreneurs to contribute to tourism development in rural areas and to the goals of regional tourism policy through the creation of new paths of development. By way of applying the EEG concepts of path dependency and path creation, the study has sought to contribute to a better understanding of the role of immigrant tourism entrepreneurs in the context of public efforts to spur tourism development in a region characterized by declining manufacturing industry.

From the side of public development actors, European immigrant tourism entrepreneurs in Gävleborg were expected to act as inspirers and icebreakers in the processes of stimulating new touristic products, growth of foreign visitor numbers and increased co-operation among local tourism stakeholders. The case study confirmed that the strategies and agencies of several immigrant entrepreneurs were in line with the public ambitions of increased professionalization and internationalization. Building on pre-migration experiences and networks, immigrant informants were seen to capitalize on natural resources in new ways and to attract increasing numbers of foreign tourists. Some of them also became important partners and allied to the regional actors in public initiatives to focus on international marketing. Moreover, several took on the role of local innovators, struggling to initiate new networks and a spirit of co-operation. However, in most cases these efforts lacked concrete results in terms of stable collaborating networks on a destination level. In parallel, the efforts of public development actors to stimulate professionalization of the tourism sector only to a limited degree seemed to contribute to regional destination development in a broader sense.

Both immigrant entrepreneurs and regional tourism development actors were seen to face twofold path dependence in their efforts to professionalize and internationalize the tourism sector. First, in a broader regional context, cognitive, functional, and political lock-in effects (Grabher, Citation1993) related to a strong historical tradition of primary resource based and manufacturing industry structure were identified as crucial. These concepts proved fruitful for understanding the perceived resistance against regarding tourism as a proper industry, achieving cross-sectoral networking and placing tourism on the public development agenda along with traditional industries. Second, path dependence within the tourism sector itself was seen to be characterized mainly by cognitive lock-in effects related to traditions of hobby-based firms and collective values of public recreational access and social cohesion (Vallström, Citation2014). The general notion was that these lock-in effects hindered path creation efforts entailing the promotion of values of individual entrepreneurship, professionalization, and growth. However, single examples were given of individual immigrant entrepreneurs who had managed to mobilize local engagement in tourism destination development and inspire locals to set up their own small tourism firms. Deeper research would be needed to explore the possibilities and obstacles for transferring traditional values of social cohesion, mutual trust, and support in a single-industry community into a small-scale, socially, and ecologically sustainable tourism entrepreneurship.

Regarding the public efforts to stimulate regional destination development, the short-term nature of political decision-making (Gill & Williams, Citation2014) and project-based funding added to the path dependence challenges. For migrant informants who were active partners to the regional tourism development projects, there was an apparent risk of increased isolation following the cut of public support for stimulating network building and internationalization when project funding ended. If the potential for in-migrated tourism entrepreneurs to contribute with external networks and new knowledge for path creating tourism development should be realized, public efforts to stimulate networking between tourism firms and with other business sectors need to be stable and long term.

While our study highlights the strategies and agencies of immigrant entrepreneurs, it does not include the perspectives of local firms and only to a limited degree those of public stakeholders. There is thus a risk of bias towards the experiences of the immigrant informants. However, the interviews and informal conversations with key regional and municipal representatives and the review of public documents like development project descriptions and evaluations, confirmed the results presented.

Further research is suggested to focus on the opportunities of emerging economic sectors and branches of businesses for challenging traditional regional cultures and regional policy frameworks. If tourism is to become an alternative for lagging and peripheral regions in the rural Nordic countries and beyond, more knowledge is needed of how the institutional and cultural structures of the previous and dominant industries may be challenged and possibly altered. The role of immigrant tourism entrepreneurs in these processes could be further elaborated through studies on different types of immigrant entrepreneurs of different sub-sectors of tourism and the service industries, to enhance the development of a more nuanced and informed regional policy framework in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term “immigrant tourism entrepreneurs” will be used throughout the paper, in this case defined as entrepreneurs who have moved from abroad.

References

- Abbasian, S. (2016). Attitudes and factual considerations of regional actors towards experience industries and the tourism industry: A Swedish case study. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(3), 225–242. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2015.1067642

- Anton Clavé, S., & & Wilson, J. (2017). The evolution of coastal tourism destinations: A path plasticity perspective on tourism urbanization. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 96–112. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1177063

- Aqueveque, C., & Bianchi, C. (2017). Tourism destination competitiveness of Chile: A stakeholder perspective. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(4), 447–466. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2016.1272482

- Arthur, W. B. (1989). Competing technologies, increasing returns, and ‘lock-in’ by historical events. Economic Journal, 99, 116–131. doi: 10.2307/2234208

- Boschma, R., & Martin, R. (2010). The handbook of evolutionary economic geography. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bosworth, G., & Farrell, H. (2011). Tourism entrepreneurs in Northumberland. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1474–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.015

- Brouder, P. (2014). Evolutionary economic geography and tourism studies: Extant studies and future research directions. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 540–545. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2014.947314

- Brouder, P., & Eriksson, R. H. (2013). Tourism evolution: On the synergies of tourism studies and evolutionary economic geography. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 370–389. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.07.001

- Burt, R. S. (2002). The social capital of structural holes. In M. F. Guillen, R. Collins, P. England, & M. Meyer (Eds.), The new economic sociology: Developments in an emerging field (pp. 148–190). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Carson, D. A., & Carson, D. B. (2017). International lifestyle immigrants and their contributions to rural tourism innovation: Experiences from Sweden's far north. Journal of Rural Studies., doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.08.004

- Carson, D. A., Carson, D. B., & Eimermann, M. (2017). International winter tourism entrepreneurs in Northern Sweden: Understanding migration, lifestyle and business motivations. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality & Tourism, 18(2), doi: 10.1080/15022250.2017.1339503

- Carson, D. A., Carson, D. B., & Lundmark, L. (2014). Tourism and mobility in sparsely populated areas: Towards a framework and research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(4), 353–366. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2014.967999

- Carson, D., Cleary, J., de la Barre, S., Eimermann, M., & Marjavaara, R. (2016). New mobilities – New economies? Temporary populations and local innovation capacity in sparsely populated areas. In A. Taylor, D. B. Carson, P. C. Ensign, L. Huskey, R. O. Rasmussen, & G. Saxinger (Eds.), Settlements at the Edge: Remote human settlements in developed nations (pp. 178–206). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- CMA Research (2012). BILDEN AV GÄVLEBORG SOM RESMÅL [The image of Gävleborg as a destination]. Gävle: CMA Research.

- Copus, A., Dubois, A., & Hedström, M. (2011). Expanding horizons: Local embeddedness and local engagement among small firms in the European countryside. European Countryside, 3(3), 164–182. doi: 10.2478/v10091-012-0002-y

- David, P. A. (1985). Clio and the economics of QWERTY: The necessity of history. American Economic Review, 75, 332–337.

- Dubois, A. (2016). Transnationalising entrepreneurship in a peripheral region – the translocal embeddedness paradigm. Journal of Rural Studies, 46, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.05.003

- Eimermann, M. (2016). Two sides of the same coin: Dutch rural tourism entrepreneurs and countryside capital in Sweden. Rural Society, 25(1), 55–73. doi: 10.1080/10371656.2016.1152033

- Førde, A. (2014). Integrated tourism development? When places of the ordinary are transformed to destinations. In A. Viken, & B. Granås (Eds.), Tourism destination development. Turns and tactics (pp. 153–170). Farnham: Ashgate.

- Gibson, L. (2006). Learning destinations – The complexity of tourism development. Faculty of Social and Life Sciences. Dissertation. Karlstad University Studies 2006:41.

- Gill, A. M., & Williams, P. W. (2011). Rethinking resort growth: Understanding evolving governance strategies in Whistler, British Columbia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 629–648. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.558626

- Gill, A. M., & Williams, P. W. (2014). Mindful deviation in creating a governance path towards sustainability in resort destinations. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 546–562. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2014.925964

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties. The “lock-in” of regional development in the Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm – on the socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). London: Routledge.

- Graffman, A. B. (2012). Region Gävleborg. Intervjuundersökning utlandsmarknaden [The region of Gävleborg. Interview survey foreign market]. Uppsala: Graffman AB.

- Graham, E. (2005). Philosophies underlying human geography research. In R. Flowerdew, & D. Martin (Eds.), Methods in human geography. A guide for students doing a research project (pp. 8–33). Harlow: Pearson.

- Hall, C. M. (2008). Tourism planning. Policies, processes and relationships. Second edition. Harlow: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Heldt Cassel, S. (2008). Trying to be attractive. Image building and identity formation in small industrial municipalities in Sweden. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4(2), 102–114. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000086

- Heldt Cassel, S., & & Pashkevich, A. (2011). Heritage tourism and inherited institutional structures. The development of a tourist destination at the World Heritage of the Great Copper Mountain in Falun. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(1), 54–75. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2011.540795

- Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2011). Qualitative research methods. London: Sage.

- Hjalager, A.-M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.012

- Hjalager, A.-M., Huijbens, E. H., Björk, P., Nordin, S., Flagestad, A., & Knútsson, Ö. (2008). Innovation systems in Nordic tourism. Oslo: Nordic Innovation Centre.

- Huggins, R., & Johnston, A. (2009). Knowledge networks in an uncompetitive region: SME innovation and growth. Growth and Change, 40(2), 227–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2257.2009.00474.x

- Huijbens, H. E., Hjalager, A.-M., Björk, P., Nordin, S., & Flagestad, A. (2009). Sustaining creative entrepreneurship: The role of innovations systems. In J. Ateljevic, & J. S. Page (Eds.), Tourism and entrepreneurship – International perspectives (pp. 55–74). Oxford: Elsevier.

- Iversen, I., & Jacobsen, J. K. S. (2017). Migrant tourism entrepreneurship in rural Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(4), 484–499. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2015.1113887

- Kaján, E., & Saarinen, J. (2014). Transforming visions and pathways in destination development: Local perceptions and adaptation strategies to changing environment in Finnish Lapland. In I. A. Viken, & B. Granås (Eds.), Tourism destination development. Turns and tactics (pp. 189–207). Farnham: Ashgate.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2012). Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Lardiés, R. (1999). Migration and tourism entrepreneurship: North-European immigrants in Cataluna and Languedoc. International Journal of Population Geography, 5(6), 477–491. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199911/12)5:6<477::AID-IJPG167>3.0.CO;2-U

- Larsson, A., & Lindström, K. N. (2015). Bridging the knowledge-gap between the old and the new: Regional Marine experience production in Orust, Västra Götaland, Sweden. In H. Halkier, M. Kozak, & B. Svensson (Eds.), Innovation and tourism destination development (pp. 5–22). London and New York: Routledge.

- Leiper, N. (1979). The framework of tourism: Towards definitions of tourism, tourists and the tourism industry. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 390–407. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(79)90003-3

- Lindquist, P., & Kempinsky, P. (2017). Slututvärdering – Etableringsprojektet [Final evaluation – Establishing project]. Stockholm: Kontigo AB.

- Müller, D. K. (2013). Sweden. In C. Fredricsson, & L. Smas (Eds.), Small-scale tourism in rural areas: Trends and research in Nordic countries (pp. 41–46). Stockholm: Nordregio. Nordic Working Group 1B: Future Rural Areas. Nordregio Working paper 2013:3.

- Müller, D. K., & Brouder, P. (2014). Dynamic development or destined to decline? The case of Arctic tourism businesses and local Labour markets in Jokkmokk, Sweden. In A. Viken, & B. Granås (Eds.), Tourism destination development. Turns and tactics (pp. 227–244). Farnham: Ashgate.

- Müller, D. K., & Jansson, B. (2007). The difficult business of making pleasure peripheries prosperous: Perspectives on space, place and environment. In D. Müller, & B. Jansson (Eds.), Tourism in peripheries: Perspectives from the Far North and South (pp. 3–18). Wallingford: CABI.

- Näringslivets ekonomifakta (2017). Regional statistik. Retrieved from http://www.ekonomifakta.se

- Pastras, P., & Bramwell, B. (2013). A strategic-relational approach to tourism policy. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 390–414. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.009

- Region Gävleborg. (2009). Besöksnäringsstrategi för Gävleborg 2009–2020 [Tourism industry strategy for gävleborg 2009-2020]. Gävle: Region Gävleborg.

- Region Gävleborg. (2013). Reviderad projektbeskrivning för Nu kör vi [Revised project description for ‘Let's go’]. Gävle: Region Gävleborg.

- Region Gävleborg. (2014). Etableringsprojekt för besöksnäringen i Gävleborg [Establishing project for the tourism in Gävleborg]. Gävle: Region Gävleborg. Dnr: REGX-2014-000048.

- Region Gävleborg (2017). Lite fakta om Gävleborg [Some facts about Gävleborg]. Samhällsmedicin. Gävle.

- Rønningen, M. (2010). Innovation in the Norwegian rural tourism industry: Results from a Norwegian survey. The Open Social Science Journal, 3(1), 15–29. doi: 10.2174/1874945301003010015

- Scott, N., Baggio, R., & Cooper, C. (2008). Network analysis and tourism. From theory to practice. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

- Stam, E. (2010). Entrepreneurship, evolution and geography. In R. Boschma, & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary geography (pp. 139–161). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Statistics Sweden (2017). Jordbruksmark och skogsmark i hektar efter region, markanvändningsklass och år. År 2010. Retrieved from http://www.scb.se

- Stone, I., & Stubbs, C. (2007). Enterprising expatriates: Lifestyle migration and entrepreneurship in rural Southern Europe. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 19(5), 433–450. doi: 10.1080/08985620701552389

- Strambach, S., & Halkier, H. (2013). Reconceptualising Change. Path dependency, path plasticity and knowledge combination. Zeitschrift Fuer Wirtschaftsgeographie, 57(1–2), 1–14. doi: 10.1515/zfw.2013.0001

- Svensk Turism. (2010). National strategy for the Swedish tourism industry. Stockholm: Svensk Turism AB [in Swedish]. Retrieved from http://www.strategi2020.se/

- Tillväxtverket (2017). Summer tourism 2017. Retrieved from http://tillvaxtverket.se

- Valentine, G. (2005). Tell me about … : using interviews as a research methodology. In R. Flowerdew, & D. Martin (Eds.), Methods in human geography. A guide for students doing a research project (pp. 110–127). Harlow: Pearson.

- Vallström, M. (2014). BERÄTTELSER OM PLATS, PLATSEN SOM BERÄTTELSE [Stories about place, the place as a story]. In M. Vallström (Ed.), NÄR VERKLIGHETEN INTE STÄMMER MED KARTAN. LOKALA FÖRUTSÄTTNINGAR FÖR HÅLLBAR UTVECKLING [When reality doesńt correspond with the map. Local preconditions for sustainable development] (pp. 57–97). Falun: Nordic Academic Press.

- Viken, A., & Granås, B. (2014). Dimensions of tourism destinations. In A. Viken, & B. Granås (Eds.), Tourism destination development. Turns and tactics (pp. 1–17). Farnham: Ashgate.

- Volo, S. (2006). A consumer-based measurement of tourism innovation. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 6(3-4), 73–87. doi: 10.1300/J162v06n03_05

- Williams, A. M., & Hall, C. M. (2000). Tourism and migration: New relationships between production and consumption. Tourism Geographies, 2(1), 5–27. doi: 10.1080/146166800363420