?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper explores whether shopping tourism in the context of cross-border regions may trigger more viable, and long-term, tourism despite persistent border asymmetries (e.g. price and tax differences) which are typically key to luring tourists to short-term shopping visits. While tourism development is often an explicit goal of cross-border policy initiatives, this paper is devoted to the market-driven processes that might drive tourism beyond short-term shopping in borderlands. Based upon a case study from the Norwegian-Swedish border region of Østfold-Fyrbodal, it finds that asymmetric cross-border shopping tourism supports the development of a diversified tourism sector with a variety of tourist attractions and services organised around shopping, longer overnight stays and second-home tourism. Despite persistent border asymmetries, market processes may balance off the short-term shopping visits towards supporting long-term tourism, which provides economic value to the cross-border region.

1. Introduction

Shopping represents an important economic driver of tourism development in many cross-border regions (Choi et al., Citation2016; Leal et al., Citation2010; Timothy, Citation1995), and, in academia, it catches the attention of scholars across disciplines (Bygvrå, Citation2019; Dmitrovic & Vida, Citation2007; Lavik & Nordlund, Citation2009; Lorentzon, Citation2011; Makkonen, Citation2016; Smętkowski et al., Citation2017; Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2008; Szytniewski et al., Citation2017; Zinser & Brunswick, Citation2014). Cross-border shopping seems to be contingent upon the contextual settings in specific regions, involving both market participants and political actors. For example, the development of cross-border tourism in the European Union (EU) results from policy-driven planning approaches (Perkmann, Citation2007, Citation2003) but also market-driven processes (Sohn, Citation2014).

The present paper focuses on market-driven processes spurring shopping tourism in cross-border regions. These processes are strongly dependent upon the persistence of asymmetries between countries (Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation1999), notably price and tax differences (Smętkowski et al., Citation2017), and socio-cultural differences concerning consumer behaviour, which account for new customer experiences (Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2013) and the availability of distinct goods (Smętkowski et al., Citation2017). Although the literature discusses cross-border shopping as a factor driving economic growth in cross-border regions (for example, Makkonen, Citation2016), it is not clear whether market-driven processes in such regions can support more viable and long-term tourism development.

To address this gap, this paper explores cross-border shopping tourism as a market-driven road to long-term tourism development by presenting a literature review and a regional case study. Based upon a mixed-methodology approach with descriptive statistics and a subsequent ARDL regression analysis, including Granger causality tests, it, first, provides a comprehensive overview of “shopping tourism” versus “tourist shopping” as two different tourism variants, and, subsequently, estimates the short- and long-run relationship between them for the case region. The paper argues that cross-border tourism – including shopping tourism – develops through market forces in overlapping stages that comprise these various types of tourist activities, with “tourist shopping” evolving and contributing to a higher extent to viable tourism development than short-termed “shopping tourism”. The case region is the cross-border region of Østfold (Norway)-Fyrbodal (Sweden) where (shopping) tourism with Norway has grown into a huge, but one-sided economic factor, notably for the Swedish parts of the borderlands and contributes to regional structural change and competitiveness (OECD, Citation2018). Persistent price and tax differences between Sweden and Norway account for much of this development (Lorentzon, Citation2011).

Hence, backed by the literature, this paper wishes to establish a theoretically-grounded perspective on shopping tourism in cross-border regions that can inform policy-makers about the support of market-driven tourism processes in such regions. With a quantatitive analysis of the relationships between short-term shopping and longer-term tourism, it adds to the existing literature that consists mainly of qualitative case studies (for instance, Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2008; Szytniewski et al., Citation2017). Moreover, although ARDL models have been utilised to explore the hypothesis of tourism-led economic growth and the relationship between tourism and other variables such as foreign direct investments and substitute prices (Katircioglu, Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2009; Narayan, Citation2004), to our knowledge, no studies using this approach have hitherto looked into the relationship between cross-border shopping and tourism.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: After this introduction, Section 2 reviews the related literature and establishes a conceptual framework as well as research propositions. Section 3 describes the methodology used and research design behind the paper. Section 4 illustrates the context of the regional case, while Section 5 presents the empirical findings on this case. Section 6 discusses them, and Section 7 provides concluding comments and the limitations to this study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Borders and tourism

Borders are commonly associated with two opposite effects: they may either represent a barrier for regional economic development or a resource to foster such development (Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation1999; Prokkola, Citation2010, Citation2007; Sohn, Citation2014). This argument is backed by neo-classical economic theories, which hypothesise that a reduction of border obstacles between countries will imply more cross-border mobility (trade of goods/services and factor mobility) and adjustments in price differences in the long-term (Brenton & Manzocchi, Citation2002; Niebuhr & Stiller, Citation2004). However, manifold border asymmetries such as price and factor-cost differences continue to exist, despite the economic integration of adjacent countries (Krätke, Citation1998, Citation1999).

Such border asymmetries strongly influence tourism in cross-border regions (Timothy et al., Citation2016). Timothy (Citation1995) argues that the existence of borders might represent opportunities to develop a tourism industry that spans across the borderlands. As Perkmann (Citation2003, Citation2007) shows, the development of tourist destinations with national borders is considered as a political effort to engage in region-building. In this paper, we will not focus on such political processes, but solely explore market-driven tourism in border regions.

2.2. Cross-border shopping and tourism: definitions and measurement challenges

There are several related concepts used in the literature for shopping and tourism in border contexts, with blurry boundaries between them (Dmitrovic & Vida, Citation2007; Makkonen, Citation2016; Studzińska et al., Citation2018). First, the concept of “cross-border tourism” denotes a border-crossing leisure activity, which is genuinely connected with the existence of a national border between adjacent countries, as Timothy (Citation1995, p. 531) states:

In the context of tourism, boundaries are usually viewed as barriers to interaction, both perceptually and in reality. However, in many cases, they may be regarded as lines of contact and cooperation between similar or dissimilar cultural, economic and social systems. Boundaries in either one of these positions can heavily influence the development and flows of tourism, especially in areas adjacent to or bisected by them.

Second, “cross-border shopping” is associated with shopping as the main activity and prime motive within the larger spectrum of cross-border tourism (Timothy, Citation2001; Timothy et al., Citation2016). It represents a variant of general shopping tourism and, thus, a sub-category of tourism. Leal et al. (Citation2010, p. 136) define it as follows:

The differences in the taxation of the same good or service between countries, neighboring regions, or municipalities in the same country encourage consumers to travel to the jurisdiction where taxation is lower to acquire that good or service, as long as the tax saving compensates for the costs of traveling from one jurisdiction to another.

Finally, “shopping tourism” includes all travels where the main goal is shopping of products and services domestically or abroad (Choi et al., Citation2016; Leal et al., Citation2010). This overlaps with the fourth term of “tourist shopping”, which incorporates shopping by tourists as one activity among other tourist activities (Svensk handel, Citation2018c).

In this paper, we define all tourism-related activities that are directly or indirectly associated with the acquisition of goods and services across borders respectively within a given border region with the concept of “cross-border shopping”. However, the variety of terms used for cross-border shopping and tourism challenges the measurement of the activities found in border regions since cross-border trips typically have multiple purposes (Studzińska et al., Citation2018; Timothy, Citation1995).

2.3. A taxonomy of cross-border shopping and tourism

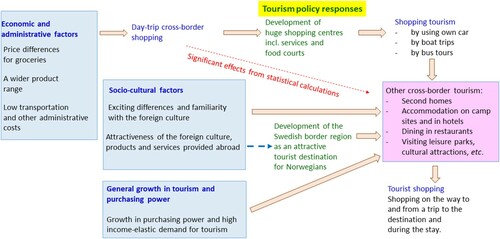

In the light of the overlapping definitions, and based upon the literature (cf. Dmitrovic & Vida, Citation2007; Leal et al., Citation2010; Makkonen, Citation2016; Smętkowski et al., Citation2017; Zinser & Brunswick, Citation2014), we establish a taxonomy of cross-border tourism (). It distinguishes between different types of border-crossings regarding shopping and tourism with the various motives of consumers and their driving factors – beyond border asymmetries.

Table 1. Taxonomy of cross-border shopping and cross-border tourism notions.

Following this, we distinguish between two inter-related types of cross-border tourism (Svensk handel, Citation2018b):

“Cross-border shopping tourism” is day tourism in the borderlands with shopping as the main goal to take advantage of price differences by acquiring cheaper goods or services, better quality, or choosing from among a wider product range in an accessible neighbouring country. It is part of the total imports of goods and services from abroad.

By contrast, “cross-border tourist shopping” refers to general tourism in a border region, with overnight stays, including weekend and longer holiday trips across borders; these trips contain cross-border shopping and the use of accommodation (hotels, B&B pensions, camping sites) and restaurant services. For these activities, shopping is not the main goal – although it is prominently represented in the range of tourist activities.

This leads to the following research propositions:

Research proposition 1: Shopping tourism and tourist shopping represent two different, yet inter-related types of cross-border tourism.

Research proposition 2: Shopping tourism across borders drives the development of a more comprehensive tourism industry in the cross-border region over time.

2.4. The drivers of cross-border shopping and tourism

The most influential publications on the drivers of cross-border tourism are Timothy (Citation2005, Citation1995), highlighting the dependence of cross-border tourism upon the specific regional conditions. Therefore, these drivers are highly contextualised, but some common patterns can be observed.

Timothy (Citation2005) stresses a set of factors influencing tourism in border contexts: First, the contrast in terms of the economic, social and cultural amenities in the part of the borderlands that hosts tourist attraction points need to be sufficiently high. Second, the tourists that cross the border will have to be equipped with enough knowledge about the amenities available in the attractive part of the borderlands. Third, potential cross-border tourists need to find enough attractions to be persuaded to undertake a cross-border shopping trip. And, finally, the border needs to be permeable enough for shoppers to cross it easily.

Smętkowski et al. (Citation2017) distinguish between economic, socio-cultural and administrative factors that drive cross-border shopping. Economic factors refer to the actual and perceived price differences, as well as the quality and supply of the goods available through cross-border shopping; socio-cultural factors are associated with the (un-) attractiveness of the foreign culture across borders and the nature of the goods and services provided there. Finally, administrative factors relate to border-crossing requirements, practices and costs. In a similar vein, Westlund and Bygvrå (Citation2002) classify various sets of factors generating interaction costs during cross-border trade and tourism, which include the costs of cross-border logistics and customs procedures, as well as political-administrative factors.

These factors matter for many border regions, as empirical studies confirm. Studzińska et al. (Citation2018) show that Russian shoppers in Finland and Poland are motivated by economic factors such as price advantages, VAT refund possibilities, the width of the product range, and the assumption of the higher qualities of EU goods. Spa and medical tourism and cultural events were other activities frequented by Russian shoppers across borders, which attests to a combination of genuine shopping with other tourist activities. Dmitrovic and Vida (Citation2007), moreover, support the argument that quality considerations influence cross-border shopping behaviour when the quality provided in one part of a borderland is considered as being higher than in the other part. As Smętkowski et al. (Citation2017) show, there are, indeed, distinct motivations for consumers to do their shopping in different parts in two-sided shopping facilities within a border region.

Besides economic and administrative factors, a sociological perspective provides further explanation. Szytniewski et al. (Citation2017) and Spierings and van der Velde (Citation2013) denote the familiarity/unfamiliarity or similarities/differences with the foreign culture in the borderlands as driving or impeding force of cross-border tourism, including shopping. For example, Spierings and van der Velde (Citation2013) describe a lack of high-quality goods in places at home as a push factor and the expected extra pleasures from the shopping trip across borders as a pull factor that determine one-sided cross-border shopping trips in a border region. Szytniewski et al. (Citation2017, p. 74) also consider “feelings of comfortable familiarity and attractive unfamiliarity” as incentives for cross-border shopping.

This leads to the following research proposition:

Research proposition 3: Because the drivers of shopping tourism across borders are multi-faceted, with economic factors as the basis, they jointly support viable tourism development across borders.

2.5. The regional impact of cross-border shopping and tourism

On the global scale, tourism is expected to grow at higher rate than GDP in the future (UNWTO, Citation2018; World Travel & Tourism Council, Citation2019). This global trend is also reflected in regional predictions for cross-border tourism. According to Svensk handel (Citation2018a, Citation2018c), this tourism in Sweden, including shopping tourism, is expected to grow at least as much or even more than the country’s total tourist consumption, which will affect tourism development in Sweden’s border regions to Norway.

For regional planning, cross-border tourism development might be used not only for economic development but also to “strengthen regional images, shape identity narratives and facilitate cross-border interactions” (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2017, p. 1015). Makkonen (Citation2016) shows that cross-border shopping in the Danish-German borderlands has a huge impact on regional attractiveness. However, tourism development at a border is also associated with challenges and barriers of different kinds and sources (administrative, institutional, language- and mentality-related ones, etc.), which makes it necessary for planners and policy-makers to engage in “region-building” for tourism development (Perkmann, Citation2003; Prokkola, Citation2007). This approach is followed by EU policies with the creation of administrative units in borderlands (Badulescu & Badulescu, Citation2017; Perkmann, Citation2003).

Besides policy approaches, Smętkowski et al. (Citation2017) point to the strategy of developing border regions through market forces. Indeed, in a scenario of liberalised markets within a cross-border region where two different national economic models meet, as was the case with the early post-transformation years in Eastern Europe in the 1990s, the market forces will be likely to support the tourist activities demanded by consumers. Stryjakiewicz (Citation1998) models an upgrading process with an intensification of economic activities over time; it starts with private transactions, informal petty trade, and shadow markets that will be gradually superseded in the course of economic integration by regular and less informal shopping points, given the demand for these regular shopping activities. Over time, activities with higher value-added will generate economic effects in the region, for instance, through capital investments (cf. Smętkowski et al., Citation2017).

According to this argument, tourism development in cross-border regions will initially be driven by low-level, or informal, activities, through the exploitation of price and tax differences, but over time turn into a more comprehensive tourist industry with a broader range of services besides shopping. It is likely to assume that this more viable tourism sector may contribute to the economic development of the border region, while its existence will still be based upon border asymmetries (cf. Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation1999), which leads to a final research proposition:

Research proposition 4: Cross-border shopping (“shopping tourism”) can develop into a diversified tourist sector in a border-region context over time, which makes use of border asymmetries, but is embedded in a wider trend of tourism growth and development, notably, in the form of short and longer overnight stays that involve shopping activities (“tourist shopping”).

3. Research design, materials and methodology

For this paper, a mixed-methodology approach was adopted that, first, builds upon a descriptive analysis of variables related to cross-border shopping and tourism and, subsequently, applies an ARDL model to test for causality between these variables.

The paper integrates various sources of information and data: The official statistics in Norway and Sweden cover cross-border shopping in the border region under survey. For instance, the Statistical Office of Sweden publishes figures for exports and imports of tourism services such as lodging in camping sites, hotels, holiday villages, hostels, cottages and apartments, including special analyses (Statistiska centralbyrån, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Statistics Norway publishes quarterly statistics of the Norwegian border shopping (called ‘grensehandel’), based upon surveys, as well as selected special reports (Statistisk sentralbyrå, Citation2020, Citation2019a, Citation2011). Since cross-border shopping is part of the ‘non-observed economy’ (OECD, Citation2002) in statistical terms, its volume, composition, and geographical distribution cannot be counted directly. However, the non-observed economy affects the production, employment, and trade in the countries trading in this sector, which makes it necessary to estimate the activities listed therein. Therefore, annual surveys and reports from Sweden and Norway that estimate the volume of cross-border shopping between the two countries were included: The Swedish Trade Federation publishes annual key figures about shopping tourism in Sweden (Svensk handel, Citation2018a) and special reports on cross-border shopping (Svensk handel, Citation2018b, Citation2018c). In addition, the lobby organisation for the Norwegian trade industry VIRKE also publishes relevant figures that mostly concern the one-sided border trade (Menon Economics, Citation2017).

As research design, the paper, first, compiles the information on cross-border shopping and general tourism into a comprehensive descriptive analysis. These statistics aim to provide an overview of the overall cross-border tourism activities in the case region since there are no statistics available for the case region, which could estimate the tourism of Norwegians in Sweden outside genuine “shopping tourism”. For example, the statistically-reported data on shopping by Norwegians do not include three important activities that might be classified as cross-border shopping: (i) tax-free shopping trips on boats, in airports, and during organised excursions; (ii) the consumption of goods and services during private and business-related trips abroad; and (iii) private imports for own consumption that is declared and subject to customs at the border.

Subsequently, we use an ARDL model (Pesaran et al., Citation2001; Pesaran & Shin, Citation1999) to investigate whether cross-border shopping can affect tourism development in the short and long run. The model takes account of the present non-stationarity (whilst also allowing for the inclusion of stationary variables) of time series, and it is particularly suitable when the sample size is small due to the super consistency of the estimators. By applying the bounds test for cointegration and assessing the estimated coefficients in the model, it is investigated whether Granger causality exists between the variables both in the long run and in the short run.

4. The context of the Østfold-Fyrbodal cross-border region

Although cross-border shopping activities by Norwegians take place all along the entire border with Sweden, they are concentrated in a few places with large shopping centres in the southern part of the borderlands, such as Strömstad and Tanum in the Swedish municipal federation of Fyrbodal (Västra Götaland) and Charlottenberg and Töcksfors (Värmland). Østfold-Fyrbodal () is a key location with cross-border tourism including shopping by Norwegians. Østfold in Norway and Fyrbodal in Sweden are quite similar with regard to their geography, settlement, and population structure (). The beautiful coast with numerous bays and skerry archipelagos is the main tourist attraction in both parts. Østfold stretches north close to the Norwegian capital city of Oslo and has a population of about 1.6 million people. Fyrbodal belongs to the Swedish county of Västra Götaland. With its hinterland, it covers about 1.7 million people, including the metropolis of Gothenburg. Hence, Østfold-Fyrbodal is centrally located in Scandinavia (OECD, Citation2018). Therefore, more than one in three Norwegians can reach the Swedish part of this region in less than two hours by car. A corresponding number of Swedes can also reach the Norwegian side of the border in the same time.

Map 1. Østfold – Fyrbodal. Source: www.grenseguiderna.se.

Table 2. Main characteristics of the border region Østfold (Norway) and Fyrbodal (Sweden).

Cross-border trade has existed in the case region for a long time, but its scale, composition and direction has changed over time, due to changing price differences, customs regimes, and political barriers. During recent decades, cross-border shopping has become increasingly one-sided in that the lower prices of goods and services in Sweden, among other factors, have spurred the development of a huge cross-border tourism industry. Nowadays, price differences for goods and services between Norway – with generally higher prices – and SwedenFootnote3 are a key driver, along with the variety and availability of goods, and generally, economic differences are important to account for the existence of large shopping facilities located in the border region.

Norwegians buying in Sweden are liable to comply with the various import regulations imposed by the Norwegian state, most notably import quotas on goods, such as alcohol and cigarettes, meat and dairy products, and a maximal duty-free amount for private shopping abroad. These regulations cover all international trade transactions between Norway and the EU, and not just adjacent countries such as Sweden. Other than differences in prices due to taxation, fluctuations in the exchange rates of the Norwegian and Swedish crowns are rather moderate and do not significantly affect the shopping behaviour of Norwegians in Sweden. To accommodate these fluctuations, the large shopping locations in Sweden accept payment in Norwegian Crowns in addition to the Swedish currency.

The border is very permeableFootnote4, but subject to regular border controls by the Norwegian customs, given that it represents an external EU border. These controls focus on peak hours, days or seasons. However, the border formalities are generally low and constitute only low administrative barriers for cross-border tourists, notably shopping tourists. In addition, the languages spoken in Norway and Sweden are similar, which facilitates transactions associated with shopping and tourism across borders. The infrastructure also enables direct connections within the border region through the E6 motorway and ships crossing between Norway and Sweden, which accounts for short travel distances.

Finally, the asymmetric shopping tourism is also reflected in the political debates in the two countries. In Norway, its focus is on the trade leak effects because of the cross-border shopping business in Sweden but also in other countries (cf. Menon Economics, Citation2017; Milford et al., Citation2012).Footnote5 Contrary to the critical Norwegian perspective, the political discussion in Sweden expresses satisfaction about the positive effects of border trade on employment in Swedish retail and related industries in the border region (Svensk handel, Citation2018c).

5. Empirical analysis

5.1. The dimension of cross-border shopping between Norway and Sweden

At first sight, the amount of cross-border shopping by Norwegians increased considerably between 2010 and 2018 (). In 2010, their total expenditure for shopping made by one-day trips amounted to 10.5 billion NOK, for buying food and mineral water (51.3%), alcoholic beverages (15.4%), tobacco (13.1%) and other goods including services (18.7%). Nearly all this expenditure (93%) was conducted in Swedish border regions (Statistisk sentralbyrå, Citation2011), and these proportions changed only incrementally in the past years (Statistisk sentralbyrå, Citation2020). In 2018, cross-border shopping had increased to even 15.7 billion NOK, spent on 8.4 million day trips, with almost 80% going to the Swedish shopping centres in Strömstad, Töcksfors and Charlottenberg, and only 15% to other destinations along the border. Day trips to other countries for shopping purposes are insignificant. In fact, cross-border shopping conducted by Norwegians is concentrated in the two Swedish counties of Västra Götaland and Värmland and has important revenue and employment effects for the retail trade industry in the region (): while, in 2017, it amounted to 3% of all Swedish retail, it accounted for 10% in Västra Götaland and even 27% in Värmland. In a similar vein, while the Swedish retail trade is responsible for an average of 5% of total employment, this share is much higher in the border municipalities of Strömstad (24%), Eda (21%) and Årjäng (15%) [Svensk handel, Citation2018b, p. 13].

Table 3. Norweigan cross-border shopping by destination, 2018.

Hence, cross-border shopping in Sweden seems to be an important element of the consumption of Norwegians abroad, which is confirmed by the Swedish Trade Federation, estimating the volume of the total Norwegian cross-border shopping in Sweden with 13.6 million trips, both as day- and multi-day trips, and about 25.6 million SEK in 2017.Footnote6 About 70% of this expenditure (excluding expenditure for accommodation, dining, and other services consumed in Sweden) was related to the shopping of groceries and 30% to the shopping of other goods.

Concerning their region of residence, Norwegian cross-border shoppers come from all over the country, although geographical proximity to the border plays a significant role (). The two regions located closest to the Swedish border, Oslo-Akershus and South-Eastern Norway, comprise 43% of the total population, but shoppers from these areas accounted for almost 70% of the total cross-border shopping expenditure in 2018. On average, every household from South-Eastern Norway spent 14,080 NOK for cross-border shopping, compared to 6,552 NOK for the total country. Moreover, every household from South-Eastern Norway made 7.8 day trips to Sweden during the year, compared to 3.5 day trips by Norwegians in general. But even in two other border counties to Sweden, Hedmark and Oppland, the total shopping expenditure and the number of day trips per household were higher than in the rest of the country.

Table 4. Cross-border shopping – area and population, 2018.

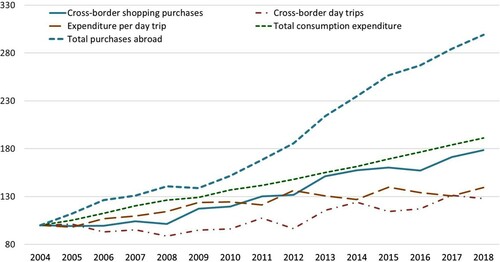

However, when compared to the total tourism expenditure of Norwegians abroad, the volume of this cross-border shopping to Sweden does not have an abnormally large scale (), and even its annual growth rates have only been moderate to date. Direct purchases abroad by resident households in Norway amounted to 123.4 billion NOK in 2018, accounting for about 8.5% of their total consumption expenditure. By contrast, the expenditure of Norwegian shoppers for cross-border shopping in Sweden is rather modest with only 1.1% of their total consumption and 13.0% of all their direct purchases abroad.

Figure 1. Norwegian cross-border shopping: Expenditure, number of day trips, total consumption and total expenditure abroad. 2004–2018, 2004=100. Source: Statistics Norway. Own calculations.

Moreover, the cross-border shopping expenditure of Norwegians () increased by 78.4% from 2004 to 2018 (the solid bold line), while their total consumption expenditure (+99.3%) and notably their consumption abroad (+199.1%) rose to a much higher extent, which can be explained with the high growth in disposable income and purchasing power of Norwegians that generates over proportional growth in their tourism expenditure and purchases abroad. Therefore, economic growth in Norway combined with the rising purchasing power of Norwegian households are the main driving forces behind the observed rapid growth of the tourism expenditure abroad. While tourism expenditure abroad as a share of total consumption increased strongly, the share of cross-border shopping expenditure in the total consumption of Norwegians remained constant with around 1.1% during this period. Even more so, cross-border shopping expenditure as a share of total purchases abroad fell from 21.3% in 2004 to 12.7% in 2018. Evidently, in this period, Norwegians increased their tourism expenditure abroad much faster compared to what they spent on cross-border shopping with day trips. also shows that the number of day trips and the expenditure per day trip increased only slightly and at a lower rate than total cross-border shopping expenditure.

As these data illustrate, cross-border shopping of Norwegians in Sweden represents only a minor part of their total tourist consumption abroad – with additional factors determining their tourism activities in Sweden. Hence, the picture of Norwegian cross-border shopping in Sweden in the narrow understanding of “shopping tourism” is well in line with the available statistics, but provides incomplete information on other cross-border tourism, including “tourist shopping” of Norwegians.

5.2. The relationship between cross-border shopping tourism and tourist shopping between Norway and Sweden

The Norwegian-Swedish cross-border tourism in total is much more extensive than what the cross-border shopping day trips alone suggest. For example, the shopping expenditure of Norwegians in connection with numerous other, multi-day, trips as well as their expenditure during overnight stays in Swedish hotels, rented cabins, self-owned second homes, on campsites, their own leisure boats in Swedish guest harbours, and for services in restaurants, leisure parks, swimming pools, etc., is not included in the data presented in 5.1. This assumption is reflected in the statistics, which show that, closely followed by Spain, Sweden is the most popular destination for outbound holiday trips by Norwegians (Statistisk sentralbyrå, Citation2019b). The border municipalities of Strömstad and Tanum and other places in Western Sweden are some of their very popular destinations for weekend and longer holiday trips. This cross-border tourism generates additional cross-border shopping beyond short-termed “shopping tourism”, which is more motivated by the consumption of leisure services than by genuine shopping. Here, Norwegian travellers spend money both during the stay in Sweden and on their way home.

This tourism is facilitated by short geographical and travel distances and a well-developed infrastructure for tourists between Sweden and Norway. Most travellers from Norway use the E6 or E18 motorways to enter the Swedish border regions by car (). Norwegians living on the western part of the Oslofjord region can also reach the Swedish border town of Strömstad by ferry, with three large ships operating the route six times per day and a capacity of near 4,500 passengers and 400 cars. These ships are designed for “shopping tourism” and “tourist shopping” by offering exclusive, large tax-free shopping centres and restaurants on board, combined with very low fares and even free tickets. These well-developed and fast traffic connections by car and ship both from the Norwegian border regions and further afield in Norway to the Swedish borderlands together with geographical proximity provide good conditions for a large number of Norwegian households to use cross-border traffic for shopping tourism and tourist shopping. In addition, many Norwegians cross the border in their own leisure boats, both during the summer season and for shorter weekend voyages. Moreover, consistently lower prices in the Swedish border border regions, the low cultural differences between Norwegians and Swedes and their similar languages spoken increase the region’s attractiveness to the Norwegians. Together, all these cross-border tourism activities have an important effect on the local industries and their employment in the Swedish border region.

However, there are no comprehensive statistical figures available on these tourist activities beyond those of “cross-border shopping tourism”. According to the Swedish accommodation statistics, Norwegian tourists with overnight stays are of great importance for the Swedish tourism industry, especially in the border region (Statistiska centralbyrån, Citation2020): Norwegian guests account for about 20.2% of the total 17.3 million nights spent by foreign residents in Sweden in 2018. Most popular with Norwegians in Sweden is lodging at camping sites (59.3%) and hotels (32.7%). More than half of all foreign residents at Swedish camping sites are Norwegians (52%), and they also account for the highest growth rate in their bookings (+46.6% from 2008 to 2018). For the two Swedish border counties, Västra Götaland (exclusive greater Gothenburg) and Värmland, Norwegian tourists are even more important than for the rest of Sweden (). Norwegian visitors account for the largest market of foreign tourists with overnight stays in both Västra Götaland (58.4% = 940,000 nights) and Värmland (48.5% = 431,000 nights). As these figures illustrate, Norway is the main target market for the Swedish tourism industry, especially in the Swedish borderlands with Norway.

Table 5. Accommodation statistics Sweden – Number of nights by region, country of residence and year.

However, this cross-border tourism between Norway and Sweden is one-sided. By comparing the Swedish figures () with Norwegian accommodation data (), it can be stated that Norway, including the border region of Østfold, is not the main market for Swedish tourists. While about 3.5 million nights were spent by Norwegian visitors in Sweden in 2018, the corresponding number for Swedes in Norway is just 1.1 million nights (11.1% of all foreign visitors). For Østfold-Fyrbodal, Swedish tourists spent only 28,000 nights in the Norwegian part, whereas Norwegians spent about 940,000 nights in the Swedish border region of Västra Götaland (exclusive Gothenburg) alone.

Table 6. Accommodation statistics Norway – Number of nights 2018 by type of accommodation and country of residence. Norway and Østfold County.

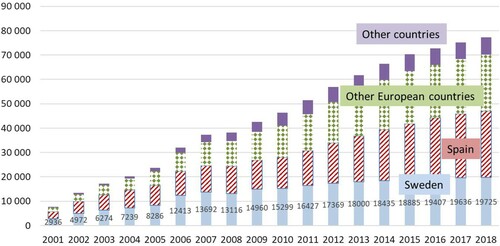

Besides overnight stays in rented accommodation, second-home tourism (Hall & Müller, Citation2018) is very popular both in Norway and Sweden (Larsson & Müller, Citation2019). Almost one in five Norwegian households owns a cottage as a second home, and Spain and Sweden are the most attractive destinations for Norwegian second-home tourism abroad (). According to Statistics Sweden, more than 12,000 Norwegians own a second home in Sweden, three in four of them in the Western Sweden border regions (Statistiska centralbyrån, Citation2018c, Citation2019a). Norwegians even settle permanently in this region. In the four border municipalities of Strömstad, Tanum, Eda and Årjäng, about 10% of all residents in 2018 were Norwegian citizens, and emigration from Norway to the Swedish border region is increasing above average (Statistiska centralbyrån, Citation2019b). Both their shopping tourism and other tourism services consumed by them account for the growth and expansion of small towns in the Fyrbodal region into larger ones such as Strömstad. With regard to second-home tourism, however, the same asymmetry applies: there are almost no Swedish second-home owners in Norway although Østfold in Norway is a popular region for domestic second-home tourists.

Figure 2. Norwegian owners of real estate abroad – selected countries 2001–2018. Source: Statistics Norway. Own calculations.

In addition, many Norwegians cross the border in their own leisure boats, both during the summer season and for shorter weekend voyages. The short distances to the coastlines of Western Sweden combined with access to many picturesque guest harbours with excellent infrastructure attract many Norwegian boat tourists every year. In the border region of Fyrbodal, Sweden, there are more than 25 guest harbours with a capacity of more than 2,650 visiting boats. Even many Norwegians, vacationing in second homes in Østfold and on boats, undertake day trips to Sweden for shopping purposes and to consume other tourist services. No statistical source exists for these activities, but the number of Norwegian leisure-boat tourists can easily be estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands per season. Their contribution to income, employment and value creation in the Swedish border region cannot be quantified either, but it is likely to assume that it is quite essential.

5.3. Estimating relationships using the ARDL model

5.3.1. ARDL model I for the relationship between cross-border shopping and tourism

For the regression analysis, we use tourism data for Sweden with a focus on the Swedish border regions of Västra Götaland and Värmland to investigate how cross-border shopping by Norwegians in these Swedish regions affects tourism. The variables included are: i) the quarterly number of overnight stays by Norwegians in these counties, which measures tourism (source: monthly data from Statistics SwedenFootnote7, as summarised for each quarter); and ii) quarterly data on cross-border shopping in Sweden (from 2004 until present, source: Statistics NorwayFootnote8), which are based upon surveys and measured for all cross-border shopping outside of Norway, made by daytrips, and corrected by distinguishing between the areas bordering South-Eastern Norway (the municipalities Strömstad, Charlottenberg and TöcksforsFootnote9) and the rest of Sweden. We use the annual measure of the proportion of total cross-border shopping of these areas for all four quarters every year to estimate quarterly cross-border shopping in Strömstad, Charlottenberg and Töcksfors from the total quarterly cross border shopping.

To investigate the relationship between cross-border shopping and tourism in terms of overnight stays, the following ARDL model is used, which considers overnight stays as dependent variable:

(1)

(1) where

and

are the log of the number of overnight stays respectively cross-border shopping in quarter t. Furthermore,

is a linear trend, p is the number of lags for the dependent variable and q for the independent variable. The number of lags is chosen by using the Schwartz information criteria as suggested by Pesaran and Shin (Citation1999). In addition, we include seasonal dummies (not shown in (1)) as exogenous variables, a restricted trend, and a constant. Finally,

is an error term.

Hence, (1) may be re-formulated as an error correction model

(2)

(2) where

contains the cointegration vector, which describes the long-run relationship between the variables,

is a constant term,

is the first difference operator (

) and

for

are the three quarterly seasonal dummies.

The bounds test is a test of the long-run relationship between the (endogenous) variables in the model, containing an F-test with a non-standard distribution that tests the null hypothesis that all of the coefficients in the cointegration vector in (2) are zero. If the bounds test indicates cointegration between the variables and the use of logarithmic variables, we can interpret the

coefficients in (2) as short-run elasticities and the long-run coefficients in

as long-run elasticities.

Therefore, estimating the ARDL model for as the dependent and

as the independent variable with seasonal dummies and a restricted trend yields an ARDL model where

and

, which provides the following error correction model:

where

. The results are shown in together with the test statistic and critical value for the Bounds test as well as tests for serial correlation and heteroscedasticity in the error terms.

Table 7. Error correction model and bounds test (ARDL model I)

The bounds test (Table 7) suggests cointegration between cross-border shopping and tourism since the test statistic exceeds the critical value both for I(1) and I(0). The long-run coefficients show that increased cross-border shopping leads to increased overnight stays and there are seasonal effects. Additionally, the trend is positive and significant, such that there is also an unobserved component leading to growth in overnight stays in the long run. The short-run effect is in the same magnitude, suggesting a positive short-term effect of cross-border shopping on tourism. However, estimating the ARDL model with overnight stays as the dependent variable suggests no long-run relationship between cross-border shopping and tourism, which indicates that the direction of the Granger causality goes from cross-border shopping to overnight stays, but not vice-versa.

5.3.2. ARDL model II for the relationship between cross-border shopping, tourism and second-home ownership

Furthermore, another ARDL model is calculated with annual data on the number of leisure houses owned by Norwegians in Västra Götaland and Värmland, Sweden (source: Statistics SwedenFootnote10). The data on houses are combined with annual data on cross-border shopping in these regions and annualised data on overnight stays (summing up the quarterly data from Statistics Sweden, as in 5.3.1.). By applying an ARDL model that uses both overnight stays (tourism) and cross-border shopping as independent variables, we estimate how the ownership of leisure homes by Norwegians may have been spurred by their cross-border shopping and tourism activities as follows:

(3)

(3) where

is the log of the number of leisure homes in the Swedish border regions that are owned by Norwegians in year

, and the variables for the log of cross border shopping and the number of overnight stays is summarised into annual data. The sample, then, spans from 2008 to 2019, giving a total of 11 observations for each variable. Accordingly, equation (2) may be reformulated and estimated as an error correction model shown in (without seasonal dummy variables because annual data are used).

Table 8. Error correction model and bounds test (ARDL model II)

The bounds test in the estimated ARDL model II for annual data when investigating the effect of overnight stays and cross-border shopping indicates a long-run relationship between the variables. There are no significant terms in the cointegration term, but there is a short-run effect from cross-border shopping on leisure homes. Hence, there seems to be a causal effect at least in the short-run. The results for short- and long-run effects are also different when using annual instead of quarterly data, since a short-run effect will then be utilised over the course of at least one year. However, altogether, using cross-border shopping as the dependent variable does not suggest that there is a long-run effect on second-home ownership according to the bounds test, such that the Granger causality for the relationships investigated goes from cross-border shopping and overnight stays to ownership of leisure homes.

To sum up, the estimated ARDL models I and II suggest Granger causality of cross-border shopping both on overnight stays and ownership on leisure homes in Sweden. This causality can be shown to exist for the relationships investigated in the short- and long-run when using quarterly data, whilst being confirmed only in the short-run for annual data.

6. Discussion

Regarding research propositions 1 and 2, cross-border shopping tourism between Norway and Sweden is mainly driven by price differences, but it has also evolved into a diversified tourism industry, which includes various variants of tourism beyond “shopping tourism”. However, the tourism activities described essentially represent a variant of short-time tourism, and are, as such, attractive for a growing number of “‘money-rich but time-poor’ tourists” (Nagle, Citation1999, p. 18). When the available leisure time of households grows at lower rate than their real income, short-time tourism will grow even faster, thereby fostering cross-border shopping and general cross-border tourism, e.g. leisure services consumed in the tourist region, and both short-term overnight stays and longer-term stays in second-homes (“tourist shopping”). Hence, these results suggest that, in the case region, the “shopping tourism”, driven by border asymmetries, was an initial and strong impetus for tourism development, but it subsequently involved an increasing share of “tourist shopping” (). This finding, which was confirmed by the Granger causality from the empirical ARDL-analysis, speaks for the fact that cross-border shopping in the case region has itself developed into an attraction (cf. Makkonen, Citation2016) that supports general tourism development.

Figure 3. A model of driving forces of cross-border shopping and cross-border tourism in the Norwegian-Swedish border region.

Apart from price advantages for Norwegian consumers in Sweden (), the drivers for both cross-border tourism, in general, and shopping tourism, as a specific category, are the short travel distances, low transport costs and well-established infrastructure between Norway and Sweden, which provide time-saving advantages for consumers within the border region and further afield. In addition, the expansion of the existing shopping, dining, and accommodation facilities in specific locations provides a comprehensive range of goods and services to tourists, encouraging both short-term “shopping tourism” and “tourist shopping” that is embedded in longer-term trips. Continuous growth in real income and prosperity on the part of Norwegian households is another key factor driving a rising demand for tourism in general, including shopping tourism and border trade with the easily accessible, close neighbouring country of Sweden. In addition, Norwegians visiting Sweden feel a comfortable mix of attractive unfamiliarity (exciting characteristics of otherness) and comfortable familiarity (low cultural differences and similar languages), which supports the other driving forces (cf. Szytniewski et al., Citation2017; Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2013). Hence, this also confirms research proposition 3 about the multiple drivers of both cross-border shopping tourism and general tourism. These findings are in line with other studies on cross-border shopping (Studzińska et al., Citation2018; Smętkowski et al., Citation2017; Makkonen, Citation2016).

Grounded in shopping tourism, and embedded in persistent border asymmetries, an attractive tourism sector was established in the Swedish part of the case region that attracts Norwegian tourists with their various activities, including second-home tourism, overnight stays on camping sites, boat tourism in guest harbours, ferry-based shopping trips to Sweden, etc. As the empirical analysis illustrates, cross-border shopping may be a factor that drives other tourism activities, as indicated by the overnight stays through purchases of leisure homes in Sweden. Hence, tourism growth in Swedish border regions has been positively affected by cross-border shopping over time. Concerning research proposition 4, we, thus, conclude that short-termed and genuine cross-border shopping developed as a market-driven process in the case region, which grew into a more diversified tourism sector (including embedded “tourist shopping”) with longer trips on the part of travellers and a higher impact on value-added and local markets over time (cf. Stryjakiewicz, Citation1998). For example, the tourism industry with its retail, accommodation, leisure and dining facilities in the Swedish part of the border region offers jobs for Norwegian commuters across borders, accounting for tourism-related job provision. In addition, many owners of hotels, shopping malls, and ferry and bus companies are Norwegians who invest across the border.

However, our analysis also confirms that this cross-border tourism is asymmetric and favours mostly the Swedish borderlands because its economic impact on value creation and employment occurs mainly there. Nevertheless, the prosperity of the Swedish border region as a tourist region has become more independent of the large price differences, which attract Norwegian tourists primarily to the shopping malls. As an OECD (Citation2018, p. 183) study finds, the border region will actually have greater tourism growth potential than other inland regions in Sweden, and its tourism industry, including its shopping section, will have a positive effect on regional economic development. While Western Sweden represents a rather sparsely populated rural region, the tourism industry with the high number of Norwegians from urban areas provides a transfer of income and purchasing power from richer, urban regions to poorer, rural regions across borders. This kind of regional transfer is not essential to the existence of a national border, but, in this case, the border-specific factors such as price differences between Norway and Sweden, the good infrastructure and extended shopping facilities act as accelerators for tourism development beyond short-time “shopping tourism”.

In a similar vein, the ownership of leisure properties by many Norwegians in Sweden has a significant effect on value creation and employment in the Swedish part of the border region, through investments in real estates, operating and maintenance services, the payment of public taxes to municipalities, etc. Second-home tourism can balance the challenges linked with short summer seasons because Norwegian tourists with short distances to their Swedish second homes undertake additional trips on weekends, generating income and employment to the local tourist industry throughout the year (Larsson & Müller, Citation2019, p. 1969).

7. Concluding comment, limitations and outlook on future research

Although the literature describes many facets of cross-border shopping, this paper departed from a gap in the literature on the market-driven processes underlying viable tourism development across borders with short-termed shopping tourism as the initial trigger. Using the regional case of Østfold (Norway)-Fyrbodal (Sweden), the paper finds that the cross-border shopping of Norwegians in Sweden is a huge and one-sided business that benefits the Swedish part of the border region, but has also developed into a comprehensive and viable tourism industry that generates employment and value-creation effects for the entire border region through supporting longer overnight stays and ownership of properties (cf. Timothy, Citation1995). Despite the persistence of border asymmetries encouraging short-time “shopping tourism”, the growth of “shopping tourism” is accompanied by the rising importance of more sustainable “tourist shopping”, which involves higher value-added from tourist inflows into the border region.

As a lesson from the case study, the market-driven shopping business across borders can develop into a viable and diversified tourist industry with shopping as initial activity that supports sustainable economic development in border regions. From a planning perspective, the paper shows that short-termed, less sustainable “shopping tourism” can foster a more viable type of longer-term tourism with overnight stays, higher value-added on economic development and ownership of properties involved. Although this process can be actively supported and even steered by policy-makers, the paper illustrates that it can also be spurred based upon the underlying market-driven processes – in spite of persistent border asymmetries such as price and tax differences.

The present case study is, however, limited, in that it is based upon data from different sources, given the lack of a complete statistical compilation of, notably, tourism data outside shopping tourism in the case region. Therefore, future research should try to conduct surveys and organise interviews with more key actors involved in the tourism development to complete the picture being drawn and to complement the statistical data issued. Another limitation is that policy actors are not considered with this case study although they are important in influencing the development of industries in both regions and countries. Hence, the role of policy-making in tourism development should be investigated in follow-up research and compared with the market-driven processes explored in this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 This definition overlaps with the definitions by the OECD (Citation2002, p. 147) and the Norwegian Ministry of Finance (Finansdepartementet, Citation2003, p. 74), which both refer to short-term trips of private households across a national border to a neighbouring country with the goal of buying a selection of goods at lower prices than in the domestic country. In the OECD definition, it is stated that “private individuals buy goods abroad because of lower taxes and import them for their own consumption”.

2 However, these regulations cover all international trade transactions between Norway and the EU, for instance, not just adjacent countries, such as Sweden.

3 Few individual goods such as diapers and high-end luxury wines, for example, may have lower prices in Norway relative to Sweden, which is partly due to differences in taxation.

4 However, due to the recent and unexpected border closing in the lockdown period of Norway from March to June 2020, the Swedish shopping and tourism locations found themselves in an unprecedented crisis, which will affect both the border permeability, at least in a medium-term perspective, and the outlook for tourism development in the region.

5 In fact, for individual municipalities, this diversion of purchasing power can be substantial.

6 This estimation, however, is significantly higher than the estimate presented by Statistics Norway (; cf. Svensk handel, Citation2018b), which illustrates the lack of data integration.

9 Again, these survey-based data illustrate that the three mentioned border municipalities to Norway comprise on average 75% of the total cross-border shopping, varying between 64 and 80 percent, over the sample.

10 Data retrieved from Statistics Sweden upon special request from the authors.

References

- Anderson, J., & O’Dowd, L. (1999). Borders, border regions and territoriality: Contradictory meanings, changing significance. Regional Studies, 33(7), 593–604. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950078648

- Badulescu, D., & Badulescu, A. (2017). Rural tourism development through cross-border cooperation: The case of Romanian–Hungarian cross-border area. Eastern European Countryside, 23(1), 191–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/eec-2017-0009

- Brenton, P., & Manzocchi, S. (2002). Enlargement, trade and investment: A review of economic impacts. In P. Brenton & S. Manzocchi (Eds.), Enlargement, trade and Investment: The impact of barriers on trade in Europe (pp. 10–37). Edward Elgar.

- Bygvrå, S. (2019). Cross-border shopping: Just like domestic shopping? A comparative study. GeoJournal, 84(2), 497–518. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-018-9781-6

- Choi, M. J., Heo, C. Y., & Law, R. (2016). Progress in shopping tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(supp1), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.969393

- Dmitrovic, T., & Vida, I. (2007). An examination of cross-border shopping behaviour in South-East Europe. European Journal of Marketing, 41(3-4), 382–395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560710728390

- Finansdepartementet. (2003). “Særavgifter og grensehandel. Rapport fra Grensehandelsutvalget.” NOU 2003, 17. Oslo. Retrieved November 22, 2019, from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2003-17/id118880

- Hall, C. M., & Müller, D. K. (Eds.). (2018). The Routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities. Routledge.

- Katircioglu, S. T. (2009). Revisiting the tourism-led-growth hypothesis for Turkey using the bounds test and Johansen approach for cointegration. Tourism Management, 30(1), 17–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.004

- Katircioglu, S. T. (2011a). The bounds test to the level relationship and causality between foreign direct investment and international tourism: The case of Turkey. Economics and Management, 1, 6–13. https://otik.uk.zcu.cz/handle/11025/17376

- Katircioǧlu, S. T. (2011b). Tourism and growth in Singapore: New extension from bounds test to level relationships and conditional granger causality tests. The Singapore Economic Review, 56(3), 441–453. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590811004365

- Krätke, S. (1998). Problems of cross-border integration: The case of the German–polish border region. European Urban and Regional Studies, 5(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649800500304

- Krätke, S. (1999). Regional integration or fragmentation? The German–polish border region in a New Europe. Regional Studies, 33(7), 631–641. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950078675

- Larsson, L., & Müller, D. K. (2019). Coping with second home tourism: Responses and strategies of private and public service providers in Western Sweden. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(16), 1958–1974. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1411339

- Lavik, R., & Nordlund, S. (2009). Norway at the border of EU – cross-border shopping and its implications. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 26(2), 205–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250902600207

- Leal, A., López-Laborda, J., & Rodrigo, F. (2010). Cross-border shopping: A survey. International Advances in Economic Research, 16(2), 135–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-010-9258-z

- Lorentzon, S. (2011). “Shopping along the border between Norway and Sweden as engine of regional development.” Working Paper, Department of Human and Economic Geography, School of Business, Economic and Law, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg. Retrieved November 22, 2019, from https://www.ipd.gu.se/digitalAssets/1349/1349301_occ-p-20114.pdf

- Makkonen, T. (2016). Cross-border shopping and tourism destination marketing: The case of southern Jutland, Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(supp1.), 36–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1244506

- Menon Economics. (2017). Effektene av økende norsk grensehandel – tapte arbeidsplasser, verdiskaping og inntekter til stat og kommune. Retrieved November 22, 2019, from https://www.menon.no/wp-content/uploads/2017-87-Grensehandel-tapte-arbeidsplasser-og-offentlige-inntekter-for-Norge.pdf

- Milford, A. B., Spissøy, A., & Pettersen, I. (2012). Grensehandel – utvikling, årsaker og virkning. NILF NOTAT 2012-17. Retrieved February 7, 2020, from https://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2449066/NILF-Notat-2012-17.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Nagle, G. (1999). Tourism, leisure and recreation. Thomas Nelson Publishers.

- Narayan, P. K. (2004). Fiji's tourism demand: The ARDL approach to cointegration. Tourism Economics, 10(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5367/000000004323142425

- Niebuhr, A., & Stiller, S. (2004). Integration effects in border regions - A survey of economic theory and empirical studies. Review of Regional Research, 24, 3–21.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2002). Measuring the non-observed economy: A handbook. OECD. Retrieved October 23, 2019, from https://www.oecd.org/sdd/na/1963116.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2018). OECD territorial reviews: The megaregion of Western Scandinavia. OECD. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264290679-en.

- Perkmann, M. (2003). Cross-border regions in Europe: Significance and drivers of regional cross-border co-operation. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776403010002004

- Perkmann, M. (2007). Construction of new territorial scales: A framework and case study of the EUREGIO cross-border region. Regional Studies, 41(2), 253–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400600990517

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1999). An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. In S. Strøm (Ed.), Econometrics and economic theory in the 20th century: The ragnar frisch centennial symposium (pp. 371–413). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL521633230.011.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Prokkola, E. K. (2007). Cross-border regionalization and tourism development at the Swedish-Finnish border: ‘Destination Arctic Circle’. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701226022

- Prokkola, E. K. (2010). Borders in tourism: The transformation of the Swedish-Finnish border landscape. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(3), 223–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500902990528

- Smętkowski, M., Németh, S., & Eskelinen, H. (2017). Cross-border shopping at the EU’s Eastern Edge – The cases of Finnish-Russian and Polish-Ukrainian border regions. Europa Regional, 24, 50–64. Retrieved from https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-54419-5

- Sohn, F. (2014). Modelling cross-border integration: The role of borders as a resource. Geopolitics, 19(3), 587–608. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.913029

- Spierings, B., & van der Velde, M. (2008). Shopping, borders and unfamiliarity: Consumer mobility in Europe. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 99(4), 497–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2008.00484.x

- Spierings, B., & van der Velde, M. (2013). Cross-border differences and unfamiliarity: Shopping mobility in the Dutch-German Rhine-Waal Euroregion. European Planning Studies, 21(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.716236

- Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2011). Grensehandel. Mest mat i handlekurven. Retrieved February 5, 2020, from https://www.ssb.no/varehandel-og-tjenesteyting/artikler-og-publikasjoner/mest-mat-i-handlekurven

- Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2019a). Cross border trade. Last update 29 November 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2020, from https://www.ssb.no/en/varehandel-og-tjenesteyting/statistikker/grensehandel

- Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2019b). Travel Survey. Retrieved February 5, 2020, from https://www.ssb.no/en/transport-og-reiseliv/statistikker/reise/kvartal

- Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2020). Nordmenns grensehandel. Fysisk grensehandel. Notater 2020/1. Retrieved February 2, 2020, from https://www.ssb.no/varehandel-og-tjenesteyting/artikler-og-publikasjoner/nordmenns-grensehandel

- Statistiska centralbyrån. (2018a). Norsk gränshandel i Sverige större än någonsin. Retrieved November 22, 2020, from https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/artiklar/2018/norsk-granshandel-i-sverige-storre-an-nagonsin/

- Statistiska centralbyrån. (2018b). Danmark är svenskarnas favoritgranne för konsumtion. Retrieved November 22, 2020, https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/artiklar/danmark-ar-svenskarnas-favoritgranne-for-konsumtion/

- Statistiska centralbyrån. (2018c). Norwegian ownership by far the largest. Retrieved November 22, 2020, https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/housing-construction-and-building/real-estate-tax-assessments/real-estate-tax-assessments/pong/statistical-news/foreign-ownership-and-expatriate-swedes-ownership-of-holiday-homes-in-sweden-2017/

- Statistiska centralbyrån. (2019a). Norwegian ownership continues to increase. Retrieved November 22, 2020, https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/housing-construction-and-building/real-estate-tax-assessments/real-estate-tax-assessments/pong/statistical-news/foreign-ownership-and-expatriate-swedes-ownership-of-holiday-homes-in-sweden-2018/

- Statistiska centralbyrån. (2019b). Population statistics. Retrieved November 22, 2020, https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/

- Statistiska centralbyrån. (2020). Accommodation statistics. Retrieved February 5, 2020, http://www.scb.se/nv1701-en

- Stoffelen, A., & Vanneste, D. (2017). Tourism and cross-border regional development: Insights in European contexts. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 1013–1033. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1291585

- Stryjakiewicz, T. (1998). The changing role of border zones in the transforming economies of East-Central Europe: The case of Poland. GeoJournal, 44(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006866122198

- Studzińska, D., Sivkov, A., & Domanieswki, S. (2018). Russian cross-border shopping tourists in the finnish and polish Borderlands. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 72(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2018.1451365

- Svensk handel. (2018a). Shoppingturism i Sverige 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2019, from http://www.svenskhandel.se/globalassets/dokument/aktuellt-och-opinion/rapporter-och-foldrar/shoppingturism/shoppingturism-i-sverige-2018.pdf

- Svensk handel. (2018b). Norsk detaljhandelskonsumtion i Sverige 2017. Fokus gränshandel. Retrieved November 22, 2019, from http://www.svenskhandel.se/globalassets/dokument/aktuellt-och-opinion/rapporter-och-foldrar/granshandel/norsk-detaljhandelskonsumtion-i-sverige-2017—fokus-granshandel.pdf

- Svensk handel. (2018c). Framtidens gränshandel. Business as usual? Retrieved November 22, 2019, from http://www.svenskhandel.se/globalassets/dokument/aktuellt-och-opinion/rapporter-och-foldrar/granshandel/framtidens-granshandel.pdf

- Szytniewski, B. B., Spierings, B., & van der Velde, M. (2017). Sociocultural proximity, daily life and shopping tourism in the Dutch–German border region. Tourism Geographies, 19(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1233289

- Timothy, D. J. (1995). Political boundaries and tourism: Borders as tourist attractions. Tourism Management, 16(7), 525–532. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00070-5

- Timothy, D. J. (2001). Tourism and political boundaries. Routledge.

- Timothy, D. J. (2005). Shopping tourism, retailing, and leisure. Channel View.

- Timothy, D. J., Saarinen, J., & Viken, A. (2016). Editorial: Tourism issues and international borders in the Nordic Region. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(sup1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1244504

- United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO]. (2018). Tourism highlights. 2018 Edition. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284419876.

- Westlund, H., & Bygvrå, S. (2002). Short-term effects of the Öresund Bridge on crossborder interaction and spatial behavior. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 17(1), 57–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2002.9695582

- World Travel & Tourism Council. (2019). Travel and tourism. Economic impact 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2019, from https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/regions-2019/world2019.pdf

- Zinser, B. A., & Brunswick, G. (2014). Cross-border shopping: A research proposal for a comparison of service encounters of Canadian cross-border shoppers versus Canadian domestic in-shoppers. Journal Articles. Paper 102. Retrieved November 22, 2019, from http://commons.nmu.edu/facwork_journalarticles/102