ABSTRACT

This study investigates the determinants of value co-creation in desert camps in Oman from both the customers' and the camp managers' perspectives. The concept of value co-creation in hospitality and tourism has been investigated in a range of ways in the extant literature. However, limited attention has been paid in the process of value co-creation in remote and unique destinations such as desert camps. This research focuses on 5 aspects of value co-creation which are then explored both quantitatively and qualitatively. The findings of the study indicate that within the context of desert camps, value co-creation is influenced by authenticity, engagement, place attachment, and marketing though the value-in-use concept. However, the level of this influence varies between the customers and the camp managers. Finally, findings are discussed in the light of this variance to identify and provide recommendations that enhance value co-creation in the desert camps of Oman.

Introduction

Recognised in recent years as the key to success in a competitive market environment (Gouillart & Ramaswamy, Citation2014; Pappas & Michopoulou, Citation2019), the value co-creation concept has been applied in many areas of the tourism and hospitality industry (Buhalis & Foerste, Citation2015). The importance of embracing the value co-creation concept in the hospitality and service industry arises from the fact that customers view service as means to facilitate the creation of their own experiences (Agrawal & Rahman, Citation2013). In this context, Bimonte and Punzo (Citation2016) argue that the development of tourism services and products requires adopting a strategy where the different parties are involved in the process of co-creating value (Prebensen et al., Citation2016). In fact, value co-creation is based on the notion that business organisations are no longer the only arbiters of value and that customers should not be passive actors (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004; Prebensen & Xie, Citation2017), but operant resources in the value co-creation process (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2014). As such, value co-creation helps service providers to better understand their customers’ increasing sophistication through allowing them to shape aspects of the products and services (Ketonen-Oksi et al., Citation2016). While there is considerable knowledge of the value co-creation concept in general, little is known about how this concept can be practised within the context of unique destination configurations such as desert camps (Mesoudi et al., Citation2018).

Context of the study

The tourism sector in Oman has recently witnessed significant growth (MTO, Citation2018). According to the report of the World Economic Forum, Oman is among the top ten fastest growing destinations in the world for leisure-travel spending between 2016 and 2026 (WEF, Citation2018). The growth of tourism sector in Oman is estimated to reach 11 million tourists by 2040 (FSG, Citation2018). The direct added value of the tourism sector in Oman rose to 2.3 billion USD in 2019 (TOF, Citation2020). Oman's history, culture and heritage constitute some of the major tourist attractions in Oman (Henderson, Citation2015), but its environment and, more specifically its desert, constitute the main tourism resources (MTO, Citation2018). Desert tourism and desert's camps provide a solid base to many economical activities. In addition, desert's camps contribute to generate many jobs like local guides, local professional sand-dune drivers and local handcrafts artists. According to the Ministry of Tourism of Oman, 117,000 guests have spent at least one overnight in Eastern AL-Shargiyah Region which hosts most of the desert camps in Oman during the touristic season of 2018 (MTO, Citation2018).

The desert camp is a type of accommodation facility that offers a wide range of services and activities for desert guests (Cooke, Citation2010). There are 20 desert camps in Oman which have different capacities of rooms that range from 20 up to 67 room per camp (MTO, 2020). These camps vary from basic camps offering meals and shelter to luxury five-star camps that offer high-end services and facilities (Mesoudi et al., Citation2018). These camps target mainly international tourists with cultural and natural interests. The camps are located in natural area where several activities can be performed which include Dune Bashing by 4WD vehicles, dinner under the stars, sandboarding, quad biking, camels riding, Bedouin folkloric music, serving typical dishes from the Omani Cuisine, sunrise and sunset watching in the desert, guided desert tours and discovering the local community by visiting Bedouin houses (MTO, Citation2018).

Literature on desert tourism is scant, and studies adhere mostly to sustainable tourism and eco-tourism discourses (Baker & Mearns, Citation2017; Jangra & Kaushik, Citation2018; Pérez-Liu & Tejada-Tejada, Citation2020; Tremblay, Citation2006; Woyo & Amadhila, Citation2018). However, there has been some research focusing on the tourism aspect of the desert experience, and although limited, it addresses different features of the experience. Some notable examples include the works by Narayanan and Macbeth (Citation2009, p. 371) who focused on four-wheel drive experiences in the Australian deserts, noting “the euphoria and meaningfulness in travelling through the seemingly unending open spaces”. Moufakkir and Selmi (Citation2018) also looked at the spirituality of the Sahara desert tourism experience, and Allan (Citation2016) focused of the concept of place attachment at the Wadi Rum desert in Jordan. Chatty (Citation2016), in particular, discussed the role of perceived authenticity of desert tourism in Oman, examining how the concept is contested by different social actors.

However, desert tourism (Cooke, Citation2010) and its development strategies in Oman (Mesoudi et al. Citation2018) have received relatively little attention in the literature compared to other forms of tourism. Based on this, the study contributes to the growing need to investigate various aspects of the tourism sector in Oman through analysing the concept of value co-creation in the desert camps. To do so, this study explored and reviewed several models of value co-creation (Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014; Grönroos, Citation2011; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004), and identified the most appropriate to subsequently provide solutions for the critical issues which limit value co-creation in the Omani desert camps. The study uncovers the role of customers and the desert camp managers in the process of value co-creation and provides camp managers with guidelines to enhance their services through identifying the dominant factors in value co-creation from the customer's perspective.

Theoretical background

Value and value co-Creation in tourism

The literature shows that the concepts of creating products and services with values for customers have recently witnessed radical changes (Prebensen & Xie, Citation2017). In this context, Gilmore and Pine (Citation2015) argue that the process of production has been shifted towards the customisation process, where customers become more engaged in the process of creating and enhancing their experiences. According to Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004)'s view, companies can gain advantages in a competitive market environment, if they move towards a value-centric approach that allows for the co-creation of values with customers.

Within the service industry specifically, value for customers is a positive feeling that can be obtained when using a certain product or service (Grönroos, Citation2011; Agrawal & Rahman, Citation2013). Grönroos (Citation2011) also forwards the perception of service as a concept based on creating value, rather than a type of market offering. Value creation is therefore come to be considered as the core of the service industry in the current marketplace (Boksberger & Melsen, Citation2011).

Value co-creation is derived from the service-dominant logic concept which is based on an exchange of resources and services between parties to create a shared value (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2014), based on the social, cultural, economic, an environmental mechanisms of all actors (Cannas, Citation2018). Revolving around the idea that it contributes to bring multiple stakeholders together onto a single platform (Lugosi, Citation2014), value co-creation is also defined as an organisation's ability to embrace active contributions from consumers during the process of creating value-added products and services (Hsiao et al., Citation2015).

The emergence of value co-creation was influenced by changing aspects of the marketplace, in particular by technology and by the customers’ changing expectations (Chathoth et al., Citation2016). Arguably, the incorporation of customers’ needs and expectations across the value chain and the subsequent emergence of the value co-creation concept (Im & Qu, Citation2017) was facilitated through IT-innovation (Franke & Schreier, Citation2010). Also, the increasing desire of a guest to capture a value from using services in the hospitality industry has encouraged them to take an active role in designing their experience (Munar & Jacobsen, Citation2014).

Also, the concept of loyalty has changed from customers being loyal to certain organisations to customers becoming loyal to values (Gilmore & Pine, Citation2015). In fact, studies prove that the guests’ loyalty and satisfaction in the tourism and hospitality industry are linked to their ability to influence the value creation process so that it meets their needs, wants and expectations (Luo et al., Citation2015; Mathis et al., Citation2016). Businesses operating in the tourism industry should therefore view value co-creation as a mechanism which can help gaining advantage in the competition process (Chesbrough, Citation2010), as it identifies and specifies the target market's segments and constructs a reliable structure for the value chain (Hsiao et al., Citation2015). As value co-creation attempts to create experiences for customers that truthfully fulfil their needs and wants (Gilmore & Pine, Citation2015), it is argued that organisations should design their attractions in ways that enable customers to co-create their experiences (Grayson & Martinec, Citation2004).

Aspects of value co-creation

The growing body of literature on the concept of value co-creation has generated considerable knowledge (Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014), and it has been approached through various perspectives and models (Skaržauskaitė, Citation2013). These models share common trends and can be divided into three categories: Value co-creation as a service science; Value co-creation as technology and innovation development and Value co-creation as a form of collaborating between the customer and the business (Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014).

For instance, one of the most prevalent models that views value co-creation as a form of collaborating between customers and businesses is the DART model (Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014). Developed by Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004), it entails as its main components Dialogue, Access, Risk-benefit and Transparency and proposes that these constitute the main elements of value co-creation between a firm and its customer (Leavy, Citation2012). While the DART model provides a solid basement for the value co-creation process, it needs additional layers to embrace other concepts within the service industry (Mazur and Zaborek, Citation2014). Alternatively, New Product Development (NPD) model often embraces value co-creation as a technology and innovation development (Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014), by identifying four styles of value co-creation: Tinkering, Submitting, Co-designing and Collaborating (Agrawal & Rahman, Citation2015). Each of these styles suits a certain business situation in order to co-create valuable products and services for consumers (Vaisnore & Petraite, Citation2011). However, this model is challenged by the contradictions caused by the increasing complexity of customer interactions (Altun, Dereli and Baykasoğlu, Citation2013). With regards to of value co-creation as a service science, the Joint Sphere Model is based on the value-in-use concept, which refers to a value created while consuming and using products and services (Chathoth et al., Citation2016; Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014). Value-in-use does not refer to the benefits obtained during the time of consuming the service only, but it extends further to include other dimensions of consumption (Agrawal & Rahman, Citation2013). These dimensions can be summarised into four types of value-in-use: physical usage (Grönroos, Citation2011), the mental usage (Payne et al., Citation2018), the virtual usage (Grönroos, Citation2011; Grönroos, Fisk and Sheth, Citation2013) and the possessive usage (Prebensen & Xie, Citation2017).

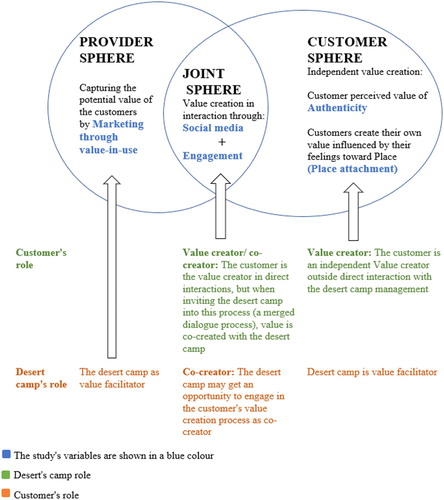

The above models, which attempt to explain the value co-creation process, are applied in different fields as well as in the tourism and service sectors (Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014). This study adopts Grönroos's joint sphere model (Citation2011) to develop a better understanding of how value can be co-created within the desert camps of Oman. Arguably, based on the fact that the value-in-use concept is designed to gain insights into customer experience and how it can be co-created (Prebensen & Xie, Citation2017), the joint sphere model enables service providers to capture different moments of the customers’ consumption and shed light on the space in which value co-creation takes place (Grönroos et al., Citation2013). As a result, the joint sphere model of value co-creation can provide firms with a better understanding of the service sector (Grönroos, Citation2011). In this study specifically, the model was adapted to incorporate the five key constructs of interest: marketing through the value in use concept (Grönroos, Fisk and Sheth, Citation2013); engagement (Eloranta & Matveinen, Citation2014), social media (Eloranta & Matveinen, Citation2014); authenticity (Counts, Citation2009) and place attachment (Suntikul & Jachna, Citation2016). The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework of the study which was guided by the joint-sphere model of value co-creation ().

Value-in-use

While viewed in an individual manner due to the customers’ different perceptions of value (Vargo and Lusch, Citation2014), the concept of value-in-use is not isolated in customers’ ecosystems, but is part of a dynamic system that links service providers and customers (Chandler & Vargo, Citation2011). Therefore, there is a need to establish a network that links customers’ internal systems of creating value with the system of supplying the services (Chandler & Vargo, Citation2011; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2012). This network can be implemented through various methods including utilising social media platforms (Eloranta & Matveinen, Citation2014).

Since the role of hospitality organisations is to facilitate the creation of value through the process of obtaining feedback from their clients throughout the different phases of service consumption (Prebensen & Xie, Citation2017), opportunities of collaborating with customers should be identified and seized upon through marketing processes (Buhalis & Foerste, Citation2015). Businesses should adopt a marketing strategy which allows customers to re-design and customise the final output (Rozenes & Cohen, Citation2010). On this regard, value- in-use ensures a maximum level of confirming the customer's expectations after using certain products or services (Payne et al., Citation2018), and it extends further to create a memorable experience afterwards (Heinonen & Strandvik, Citation2009).

Value co-creation through social media use

Social media are platforms which enable users to generate content based on their experiences and perspectives (Albarran, Citation2013). In the tourism sectors especially, technology and social media platforms have changed aspects of the marketplace through marking a new role for the customer in the process of creating value (Albarran, Citation2013; Fotis et al., Citation2011; Gouillart & Ramaswamy, Citation2014; Yang et al., Citation2016). In today's marketplace, social media are viewed as tools to obtain feedback and enhance the quality of the company's services and products based on the user's role in feeding the evaluation process (Kaplan & Haenlein, Citation2010), and in articulating perceived values that can be captured to have a better understanding of their needs (Chesbrough, Citation2011). Customers’ posts in social media platforms form a base for the ties and relationships between customers and organisations (Sorensen et al., Citation2017), and provide both parties with direct and accessible communication (Munar & Jacobsen, Citation2014). Therefore, technological interconnectivity has played a major role in improving and enhancing the tourist experience (Neuhofer et al., Citation2013).

When assessing the role of social media, it is also worth noting that tourists conduct many searches before travelling, therefore the communication circle starts with customers revising other visitors’ experiences before conducting their own experience. It then continues during the time of service and ends with the customers expressing their own views (Neuhofer et al., Citation2013). Hence, firms adopting social media as a tool for value co-creation should assess to what extent they understand their customers’ requirements through increasing their level of engagement with them (Michopoulou & Moisa, Citation2018; Neuhofer et al., Citation2013).

Value co-creation through engagement

Engagement refers to the online and offline interactions between customers and organisations (Brodie et al., Citation2011). The recognition of the importance of the engagement process is based on the effective results obtained from the active participation of the customers through the value co-creation process (Brodie et al., Citation2011; Chathoth et al., Citation2016; Singh & Sonnenburg, Citation2012).

Gouillart and Ramaswamy (Citation2014) state that value co-creation depends on the opportunities of interactions and engagement between customers and firms. Arguably, the development of technology and its accessibility through mobile devices has empowered customers to have an essential means of communication with the business (Luo et al., Citation2015). More precisely, the accessibility of information in the value co-creation process has become easier through the use of social media platforms (Gouillart & Ramaswamy, Citation2014). Therefore, businesses are investing on technology to increase customer engagement and to co-create value, as technology comes to be viewed as a tool to expand the range of the potential market in the short and in the long term (Eccleston et al., Citation2020; Gouillart & Ramaswamy, Citation2014).

Customer engagement does not only rely on their interactions with businesses, but it extends further to exclude the firm from the equation in some situations. This is known as customer to customer value co-creation (Rihova et al., Citation2018), where co-creation takes place between the customers in their own ecosystem. The visibility of these interactions becomes more obvious to service providers when customers share their experiences and opinions on social media platforms (Munar & Jacobsen, Citation2014), where the value outcomes formed through customer to customer co-creation contribute to shape a collective social value (Cheng, Citation2016).

Value co-creation through authenticity

Authenticity describes a perspective which is characterised by genuine and true aspects (Dieke et al., Citation2015). MacCannell (Citation1973) argued that the continuous desire of customers to have a genuine experience has created a strong quest for authenticity in tourism and hospitality industries. In tourism studies, the literature shows different perceptions of the concept of authenticity (Dieke et al., Citation2015; Elomba & Yun, Citation2018) also evident and contested within Omani desert tourism (Chatty, Citation2016).

Object-based authenticity emerged from a museum background, where there is a need for experts to determine the originality of items and objects (Castéran & Roederer, Citation2013). This means that judgements of what is authentic are produced by experts based on a standard and static concept without involving tourists’ opinions and experiences (Checa-Gismero, Citation2018; Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006; Tiberghien, Citation2019). Such concept has been challenged by scholars like Kolar and Zabkar (Citation2010) who argued that authenticity should be understood within its context and the perceptions of its receivers and their experiences. However, unlike certain objects’ or touristic artefacts which authenticity can be contested (Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006) the genuineness of the desert as a “pristine ecosystem and an authentic—unmodified, undisturbed and unstaged—natural space is unquestionable” (Moufakkir & Selmi, Citation2018, p. 114). Whilst object-based authenticity is applicable in desert tourism with regards to the physical environment (i.e sand dunes, clear skies, colours, stars) and objects and artefacts (i.e traditional linens and textiles), it is not adequate to describe the experiences within that space.

Consequently, the concept of constructive authenticity was introduced, where authenticity is formed by the development of the social perspectives of the customers (Olsen, Citation2002). This also disproves the static concept of authenticity mentioned above, as it suggests that authenticity is socially constructed over time (Olsen, Citation2002; Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006). Wang (Citation2010) has extended the idea of authenticity further by including the sphere of customer experience and arguing that in the hospitality industry authenticity is linked to the experiences of people, as confirmed by other studies (Castéran & Roederer, Citation2013; Checa-Gismero, Citation2018; Tiberghien, Citation2019). This is in alignment with the view of Counts (Citation2009), who states that the authenticity of experiences provides opportunities for co-production as it allows the customers to be active co-creators of their own experiences. Wang also developed a concept to differentiate between the authenticity of objects and the authenticity of experience, which has led to the concept of existential authenticity (Wang, Citation2010). This concept suggests that as the perception of authenticity is based on experience, it is linked to intrapersonal sources depending on the tourists’ feelings. The desert is a unique space (with its silence, unpredictable outlines, and raw nature) that is inextricably linked to existential authenticity as it enables contemplation and meditation because it highlights the finiteness of the human condition (Moufakkir & Selmi, Citation2018; Narayanan & Macbeth, Citation2009). The interactive multisensory experience also offers a “short-term break from the perceived inauthenticity of the everyday life” (Moufakkir & Selmi, Citation2018, p. 115). Hence, the perceived authenticity of desert camp experiences remains in the minds of the tourist, yet to be fully uncovered.

As managers encounter difficulty in harmonising the different and often contradictory types of authenticity (Kolar & Zabkar, Citation2010), businesses should adopt a strategy that originates from the customers’ point of view of authenticity (Gilmore & Pine, Citation2015). However, in order to do so, managers should be aware of the main factors that affect the concept of authenticity in the modern market (Andriotis, Citation2011; Kolar & Zabkar, Citation2010).

Value co-creation and place attachment

The process of value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industry is also related to the customers’ relationship with the physical place they are visiting (Suntikul & Jachna, Citation2016). Mossberg (Citation2007) argues that customers’ experiences are linked to their emotional perspective of a place, as the value creation emerges through co-creating positive meanings and feelings between the customers and the visited place (Suntikul & Jachna, Citation2016). Based on this, Larsen (Citation2007) argues that site engagement is of paramount importance in building up a memorable experience.

Place attachment can be divided in place dependence and place identity (Binkhorst & Den Dekker, Citation2009). Place dependence refers to the ability of the place to provide different services and to meet the needs and expectations of the customers (Larsen, Citation2007; Suntikul & Jachna, Citation2016). Place identity refers to devoting great attention to the customers’ emotional ties and connection to the place (Binkhorst & Den Dekker, Citation2009). The place attachment element contributes in shaping all four areas of tourists’ feelings and experiences: aesthetics, entertainment, education and escapism (Gilmore & Pine, Citation2015). Therefore, place attachment should be considered in value co-creation (Gilmore & Pine, Citation2015), as understanding customers’ perceptions and feelings towards a place can help tourism organisations provide them with memorable experiences (Suntikul & Jachna, Citation2016). Another consideration on place attachment is the element of place social bonding (Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010; Vada et al., Citation2019) whereby tourists look at a destination favourably, due to the social interactions that take place at the destination (i.e. exchanging stories around the camp fire). Suntikul and Jachna (Citation2016) argue that customer experience is co-created through place attachment when the service suppliers deal with this element as fundamental to value co-creation rather than as a service setting.

Building upon these considerations and responding to calls for further research on value co-creation within the tourism and hospitality sectors this study set out to understand key elements of value co-creation in the desert camps of Oman from both camp managers’ and customers’ perspectives.

Methodology

This research used a mixed methodology approach to provide the researchers the flexibility to investigate the topic with both quantitatively and qualitatively (Creswell, Citation2013; Tashakkori & Teddlie, Citation2016). The study deploys a convergent parallel design which entails collecting the qualitative and quantitative data simultaneously, analysing them separately, and then examining whether the findings complement each other by comparing the obtained results (Creswell and Plano Clark, Citation2006).

The role of the camp managers is inductively examined since there is limited knowledge about their role in the process of value co-creation (Mesoudi et al., Citation2018). Semi-structured interviews were conducted as they provide the interviewer and the interviewee with the flexibility to bring new ideas through a probing process (Bryman & Bell, Citation2015). The role of customers in the value co-creation process however has been reasonably examined in the literature (Im & Qu, Citation2017) and therefore here it is examined deductively and quantitatively, through the use of a survey. Questionnaire items were used from validated scales based on constructs adapted from the literature. Items for place attachment were adopted from Suntikul and Jachna (Citation2016), authenticity from Kolar and Zabkar (Citation2010), engagement from Braun et al. (Citation2017), social media from Carlson, Rahman, Voola, and De Vries (Citation2018) and value-in-use from Ranjan and Read (Citation2014).

To collect data from the customers, at least one characteristic for the population was set (Saunders et al., Citation2016): having had an experience in desert camps of Oman. The camp managers were selected through purposive sampling, and the snowball method (Saunders et al., Citation2016) was then deployed to grow the sample size number by allowing the interviewees to nominate other eligible participants that could be involved in the study.

The surveys were processed and analysed through SPSS computer software (Field, Citation2014). The semi-structured interviews were analysed through thematic analysis so to identify, analyse, and report patterns through positioning the information into categories within data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Bryman & Bell, Citation2015). Finally, findings from quantitative and qualitative data were converged and used to answer the study main objectives.

Findings and discussion

Analysis of qualitative data

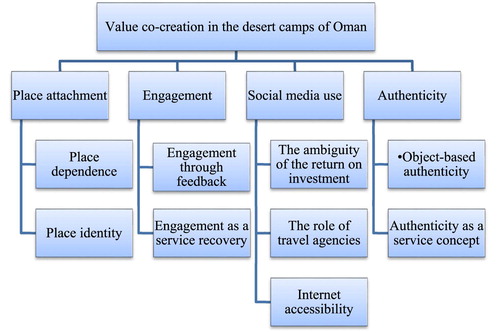

There are 20 camps in Oman in total (Alshaibi, Citation2018), and 8 camp managers were interviewed. The researcher was successful in reaching 40% of the whole population of the desert camp managers. The data saturation was reached in the fifth interview, however, the researcher carried out additional interviews to ensure robustness of data. The interviews were semi-structured which allowed exploring and grouping the data gathered into specific themes. Based on the literature review on value co-creation, the following themes that consist of other sub themes emerged through the process of the data analysis: authenticity, engagement, place attachment, and social media use ().

With regards to the central concept of value in use, findings revealed how camp managers use the joint sphere model with their customers to co-create value. In particular, the lack of adopting a comprehensive strategy to implement the different aspects of the value-in-use model was identified. In fact, interviewees highlighted that only 2 out of the 4 dimensions (Grönroos, Fisk and Sheth, Citation2013) relating to the value in use concept are being considered: the physical usage and the possessive usage. The other two dimensions (mental usage and virtual usage), which require adopting mechanisms to engage directly with the customers, received less attention from the interviewees. They believed that the joint sphere of value co-creation with their customers takes place during the guests’ stay only: “Our service design is a result of discussions with the tourists who have visited us. We take their discussions seriously. That’s why we have one of the best services in the desert camps of Oman” (Participant 1). The lack of establishing direct engagement links with customers prior to and after their arrival therefore limits the ability of the desert camp managers to create value through using mental usage and virtual usage in the value-in-use concept.

The sub themes of authenticity, engagement, place attachment, and social media use are discussed later on in this paper in conjunction with the quantitative data.

Analysis of quantitative data

The researcher was successful in collecting 336 questionnaires on the topic of value co-creation in the desert camps of Oman. Of these 336 questionnaires, 324 were suitable for data analysis. The data collected from the desert camp customers accommodate three demographic details: age, gender and origin. In terms of gender, 57.7% of the sample were male and 42.3%, female. Most of the participants were from the age group of 40–65 years, which presented a percentage of 46%. Other age groups of 18–25, 25–40 and 65+ were 12%, 15% and 27%, respectively. The participants’ background varied between 19 nationalities. The vast majority came from Germany, France, UK and Italy.

Results showed that for each indicator standardised loadings were acceptable (from 0.578 to 0.895). The Cronbach's alpha value is an indicator to examine the internal consistency of each construct and should be at least 0.70 to indicate high internal construct consistency. shows the Cronbach's alpha values for all constructs ranged from 0.713 to 0.815. Results for composite reliability (CR) were over 0.70 and ranged from 0.78 to 0.86, indicating internal consistency of the constructs. For convergent validity to be considered good, the average variance extract (AVE) values should be greater than 0.50 (Andersson, Forsgren, & Holm, Citation2001); which was true for all the constructs in this study.

Table 1. Constructs, item loadings, CA, Mean and SD.

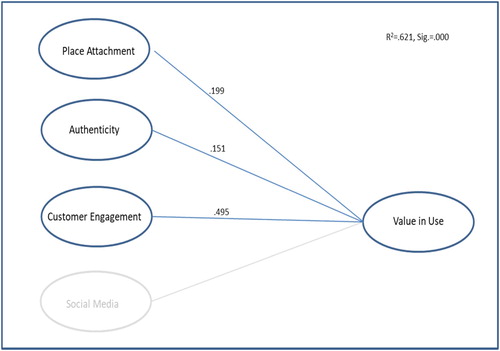

Regression results indicate that Place Attachment (β = 0.22; p < 0.05), Authenticity (β = 0.16; p < 0.05), Customer Engagement and (β = 0.57; p < 0.001) were all good predictors of Value in Use, however, social media was not significant. The overall explanatory power of the model was 62% (Adj R2= .625) ().

Customer Engagement proved to be the strongest predictor of the proposed constructs accounting for over 50% (β = 0.57; p < 0.001) of the variance of Value in Use. This finding suggests that customers want to be actively involved and participate in value creation for both themselves and the company. This reinforces the notion that customers’ ability to influence the value creation process so that it meets their needs, wants and expectations is linked to loyalty and satisfaction (Mathis et al., Citation2016). Place Attachment and Authenticity clearly linked to Value in Use, however the relationships observed were weak (β = 0.22 and β = 0.16 respectively). Surprisingly, there was no relationship between social media and value in use. This could be explained by the fact that there is no internet connectivity at the desert camps and the social media presence from the camp perspective is minimal.

The next section discusses the key constructs examined in this study from both customer and supplier perspectives by merging qualitative and quantitative data.

Customer engagement

The empirical data obtained from the customer survey show that engagement is by far the strongest predictor of value than any other construct. This is in alignment with the literature which shows that engagement is important in the active participation of customers in the value co-creation process and can take different forms including online and offline activities (Brodie et al., Citation2011; Hill & Steemers, Citation2017)

However, data from the camp managers show that there is a tendency to engage with customers through offline practices during the guests’ stay to obtain their feedback and identify improvement opportunities “Customer engagement is to get feedback from them during their stay and act positively on these feedbacks to gain their satisfaction” (Participant 6); whereas online engagement is not practiced due to the limited implementation of social media.

Interviewees also highlighted the role of travel agencies in the desert camps of Oman to engage, attract and communicate with the guests before and after their visits. In this regard, studies discuss that while on-the-spot engagement with customers contributes to obtaining quicker feedback, it has many limitations in providing the guests with their desired experience, if solely used (Fotis et al., Citation2011; Hill & Steemers, Citation2017). Engagement with customers should be practised during the different phases of the guest journey, which consists of trip planning, actual consumption of the service and communication with the guests after their departure (Fotis et al., Citation2011). It could therefore be presumed that engagement is important for customers in value creation but for most of their “journey” phases it occurs via intermediaries rather than the camps directly. Hence, intermediaries fill the engagement gap allowed by the camps.

Authenticity

The results from customer survey demonstrated that the authenticity factor is important in predicting value in use. This finding supports the premise put forward by Prebensen et al. (Citation2016) that both object-based authenticity and existential authenticity play a role in value co-creation. The low score however may be due to the fact that the measured construct entailed items for both object-based and existential authenticity. Dieke et al. (Citation2015) argue that existential authenticity in tourism activities is linked to its nature of being activity-centric, whereas object-based authenticity focuses on objects only. Hence, if customers are more focused on activity, then the scores of existential authenticity would be high, whilst scores for object-based authenticity low.

The qualitative data obtained from the desert camp managers also confirmed that authenticity is considered to be the core element in creating values for the guests: “We provide our guests with the values that they are looking for, through providing them with authentic Omani desert experience” (Participant 7) and “Providing the guests with authentic experience is key for success. Therefore, our main theme in the camp is an atmosphere of authenticity” (Participant 5). This is in alignment with the Ministry of Tourism's target to provide customers with an “Authentic Arabic experience”. Interviewees viewed that desert tourism consists of two main components: cultural and natural. The cultural component is associated with the customers’ quest for authenticity and their curiosity to discover and explore the local culture, whereas the natural component is associated with the customers’ appreciation of the landscape and their desires to perform certain activities.

The implementation of authenticity as a focal point of managers’ service concept design is practised through creating a servicescape which comprises local elements, local furniture, local décor touches and local handicrafts. Arguably, this tacit creation of value through authenticity is based on object-based authenticity (Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006; Tiberghien, Citation2019), and it doesn't factor other emerging notions of authenticity in tourism. Existential authenticity (Wang, Citation2010) for example, in which the customers should be highly involved in processes of creating values through merging their understanding of authenticity, is not widely understood nor implemented.

Place attachment

The role of place attachment in the process of value co-creation in the desert camps of Oman has here been split in two components, place identity (Binkhorst & Den Dekker, Citation2009) and place dependence (Suntikul & Jachna, Citation2016), as these represent the two main practices deployed by the desert camp managers in Oman to ensure value co-creation through place attachment. However, customers’ view of place attachment does not seem to be strong in predicting value in use.

Co-creating value with the customers through using the relationship between place identity and authenticity is a strategy widely used by the camp managers

The location of our camp was chosen in respect to our traditions and the Omani architectural style. We inform our customers that our place was chosen with these considerations. Customers therefore develop curiosity to ask different questions about our life and appreciate our authentic concept at the camp to which they get emotionally attached to this place. (Participant 1)

Regarding place dependence (Suntikul & Jachna, Citation2016), the managers of the camps which are located deep in the desert claimed that their locations provided the customers with a real, authentic desert experience as it responds to their quest for escaping from the stress of the cities

Being deep into the desert where you are just surrounded with the beautiful sand dunes, gives you unique feelings and thoughts. We are located far away from the city where our guests can free their minds and have great level of tranquillity, (Participant 4)

On the other hand, the camps which are located near the cities claimed that their locations have advantages over the other camps

Our location is very accessible, and our guests can reach us at ease unlike the other camps. Our proximity to the main roads facilitates obtaining fresh and daily supplies. The guests appreciate this top quality restaurant service and they get attached to the place of our camp. (Participant 2)

Overall, the camp managers stated that the desert camps rely heavily on the surrounding landscape to create an experience for their customers. However, a review of Gilmore and Pine's study (Citation2015) on the multi-dimensional aspects that develop the customers’ attachment to the place (aesthetic, educational, escapism and entertainment) indicates that camp managers focus mainly on two elements: escapism and entertainment; meaning that service providers are failing to use place attachment as a fundamental element in value co-creation (Gilmore & Pine, Citation2015; Suntikul & Jachna, Citation2016). It can be concluded that through considering these four factors, the camp managers could gain deeper insights into using place attachment to co-create values with their customers. This may also explain why from the customers’ perspective the importance of place attachment in predicting value was limited.

Social media use

Results from the customer survey yielded a rather surprising finding; that there is no significant relationship between social media and value in use. Hence, customers do not consider the use of social media as an important factor as a means for interaction with service providers to facilitate value co-creation. This is comes in stark contrast to Neuhofer et al. (Citation2013) who argue that social media use has changed aspects of the marketplace through marking a new role for the customers as co-creators. However, this finding seems to be context specific as explained by the qualitative data, which explored the role of the camp managers in using social media. Interviewees were hesitant to use social media platforms to co-create value with the guests: while some do not have any presence in social media at all, others use the platforms only as means of promotion. Three main barriers to the use of social media where identified: the role of travel agencies as mediators, the ambiguity of the return on investment and internet accessibility.

It can be argued that, since desert camp experiences are designed, marketed and organised by travel agencies, the value co-creation through social media takes place between the customers and the travel agencies. Sharda and Chatterjee (Citation2011) claim that the presence of intermediaries disconnects the customers from interacting directly with the service providers and Cannas (Citation2018) expands on this argument highlighting the risk for unequal power imbalances between the actors involved in the value co-creation process. Therefore, it is recommended that the camps use their own social media platforms to facilitate the process of value co-creation through building direct bridges with their customers.

Apprehension for the return on the investment also prevents the camp mangers from developing their social media platforms to increase the level of the engagement with their customers. The participants showed difficulties in assessing the real influences of social media, and showed reluctance towards investing on a social media strategy, as stated by participant 2: “We focus on our service level and we have good reviews which market our camp. Investing on social media requires financial resources. We should instead focus on our service”.

Most participants highlighted the issue of technology limitations in accessing social media platforms, as most of the camps are located in remote places. In addition, most desert camps do not provide WIFI services, and this seems to add value to the guests’ experience “In the desert, our customers enjoy our concept of getting themselves involved in different and adventurous lifestyles where they disconnect themselves from the phone addiction” (Participant 5). The researchers enquired about using the city offices to communicate with the customers on social media platforms, but the participants showed disinclination due to the limited resources, roles and numbers of employees “We have one employee working at the office, he can’t do everything” (Participant 4).

Hence, it seems that customers do not place any importance on social media in creating value at the desert camps because either there is no option for interaction altogether (camps with no social media presence) or the accounts that exist do not interact but are only used for push messages and advertising. It is therefore important to consider the camps’ barriers in using social media and develop solutions that will enable value creation.

Conclusion

This research aimed to explore the various elements and factors that can contribute to the process of value co-creation in the desert camps of Oman. The concept of value co-creation was investigated through the perspectives of the customers as well as those of the camp managers. This investigation revealed how these two parties co-create value and highlighted the discrepancies between them. Therefore, this study adds to the debate on identifying the common sphere between customers and service providers and defines this sphere within the context of service to co-create value in desert camps. Hence, this study contributes to knowledge by deepening our understanding of the process of value co-creation within unique destinations, in this case desert camps. It also establishes factors that are entailed and can enhance value in use. The study showed that authenticity, place attachment and engagement were strong predictors of value in use whilst social media was not.

In particular, customers’ quest for authenticity entailed both existential and object-based authenticity, whilst camp managers responded to their customers’ need through object-based authenticity only. The desert camp managers engaged with their customers mostly offline and during the guest's stay, but customers want to engage with the desert camps both online and offline. Customers consider place identity as an element which has a greater influence in value co-creation than place dependence. Desert camp managers are therefore co-creating value with customers through using the relationship between place identity and authenticity and by using the place identity element to design the camp's activities. With regards to social media it was evident that lack of skill and knowledge for the camp managers’ part, absence of internet access at location and a dominant and even interfering role of intermediaries, made the option of co-creating value with customers through social media unattainable.

This study has implications for practitioners. Specifically, it is important that camp managers and managers of other unique and remote locations focus on engaging with the guests before, during and after their arrival. This assists in enhancing their experience and in co-creating shared value between the destinations and their guests. This can be achieved through merging the offline and the online engagement into a single component which represents the guests’ requirements during the different phases of their journey. Managers should also concentrate on the value-in-use concept and all of its four dimensions (including mental usage and virtual value usage) in order to address customers’ needs and preferences more effectively and co-create value for all parties involved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agrawal, A., & Rahman, Z. (2015). Roles and resource contributions of customers in value co-creation. International Strategic Management Review, 3(1-2), 144–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ism.2015.03.001

- Albarran, A. (2013). The social media industries. Routledge.

- Allan, M. (2016). Place attachment and tourist experience in the context of desert tourism – the case of Wadi Rum. Czech Journal of Tourism, 5(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/cjot-2016-0003

- Alshaibi, T. (2018). Oman camps. [online] Oman Daily. http://www.omandaily.om/ HYPERLINK “http://www.omandaily.om/631970/"631970 HYPERLINK “http://www.omandaily.om/631970/"/

- Altun, K., Dereli, T., & Baykasoğlu, A. (2013). Development of a framework for customer co-creation in NPD through multi-issue negotiation with issue trade-offs. Expert Systems with Applications, 40(3), 873–880.

- Andersson, U., Forsgren, M., & Holm, U. (2001). Subsidiary embeddedness and competence development in MNCs a multi-level analysis. Organization Studies, Vol. 22(6), 1013–1034.

- Andriotis, K. (2011). Genres of heritage authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1613–1633. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.001

- Baker, M., & Mearns, K. (2017). Applying sustainable tourism indicators to measure the sustainability performance of two tourism lodges in the Namib desert. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(2), 1–22.

- Bimonte, S., & Punzo, L. (2016). Tourist development and host–guest interaction: An economic exchange theory. Annals of Tourism Research, 58, 128–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.03.004

- Binkhorst, E., & Den Dekker, T. (2009). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(2-3), 311–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19368620802594193

- Boksberger, P., & Melsen, L. (2011). Perceived value: A critical examination of definitions, concepts and measures for the service industry. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041111129209

- Braun, C., Hadwich, K., & Bruhn, M. (2017). How do different types of customer engagement affect important relationship marketing outcomes? An empirical analysis. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 16(2), 111–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1362/147539217X14909732699525

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brodie, R., Hollebeek, L., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511411703

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Buhalis, D., & Foerste, M. (2015). Socomo marketing for travel and tourism: Empowering co-creation of value. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(3), 151–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.04.001

- Cannas, R. (2018). Diverse economies of collective value co-creation: The open monuments event. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(5), 535–550. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1505651

- Carlson, J., Rahman, M., Voola, R., & De Vries, N. (2018). Customer engagement behaviours in social media: Capturing innovation opportunities. Journal of Services Marketing, 32(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-02-2017-0059

- Castéran, H., & Roederer, C. (2013). Does authenticity really affect behavior? The case of the Strasbourg Christmas market. Tourism Management, 36, 153–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.11.012

- Chandler, J., & Vargo, S. (2011). Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Marketing Theory, 11(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593110393713

- Chathoth, P., Ungson, G., Harrington, R., & Chan, E. (2016). Co-creation and higher order customer engagement in hospitality and tourism services. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(2), 222–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2014-0526

- Chatty, D. (2016). Heritage policies, tourism and pastoral groups in the sultanate of Oman. Nomadic Peoples, 20(2), 200–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3197/np.2016.200203

- Checa-Gismero, P. (2018). Global contemporary art tourism: Engaging with Cuban authenticity through the Bienal de La Habana. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(3), 313–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2017.1399435

- Cheng, M. (2016). Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57, 60–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.06.003

- Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Planning, 43(2-3), 354–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010

- Chesbrough, H. (2011). The case for open services innovation: The Commodity Trap. California Management Review, 53(3), 5–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010

- Cooke, B. (2010). Tourism in deserts. Geography Review. (09507035)

- Counts, C. (2009). Spectacular design in museum Exhibitions. Curator: The Museum Journal, 52(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2009.tb00351.x

- Creswell, J. (2013). Research design. SAGE.

- Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2006). Designing and conducting mixed methods research.

- Dieke, P., Heitmann, S., & Robinson, P. (2015). Research themes for tourism. CABI.

- Eccleston, R., Hardy, A., & Hyslop, S. (2020). Unlocking the potential of tracking technology for co-created tourism planning and development insights from the tourism Tracer Tasmania Project. Tourism Planning & Development, 17(1), 82–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1683884

- Elomba, M., & Yun, H. (2018). Souvenir authenticity: The perspectives of local and Foreign tourists. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2017.1303537

- Eloranta, V., & Matveinen, J. (2014). Accessing value-in-use information by integrating social platforms into service offerings. Technology Innovation Management Review, 4(4), 26–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/782

- Field, A. (2014). Discovering statistics using ibm spss statistics + spss version 22.0. Sage Publications.

- Fotis, J., Buhalis, D., & Rossides, N. (2011). Social media impact on Holiday travel planning. International Journal of Online Marketing, 1(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/ijom.2011100101

- Franke, N., & Schreier, M. (2010). Why customers value self-designed products: The importance of process Effort and Enjoyment*. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(7), 1020–1031. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00768.x

- FSG. (2018). Oman Tourism Report. [online] English. https://store.fitchsolutions.com/oman-tourism-report.html

- Galvagno, M., & Dalli, D. (2014). Theory of value co-creation: A systematic literature review. Managing Service Quality, 24(6), 643–683. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MSQ-09-2013-0187

- Gilmore, J., & Pine, B. (2015). Authenticity. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Gouillart, F., & Ramaswamy, V. (2014). The power of co-creation. Free Press.

- Grayson, K., & Martinec, R. (2004). Consumer perceptions of iconicity and indexicality and their influence on assessments of authentic market offerings. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(2), 296–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/422109

- Grönroos, C. (2011). A service perspective on business relationships: The value creation, interaction and marketing interface. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 240–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.06.036

- Grönroos, C., Fisk, R., & Sheth, J. (2013). Service marketing. SAGE Publications.

- Heinonen, K., & Strandvik, T. (2009). Monitoring value-in-use of e-service. Journal of Service Management, 20(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230910936841

- Henderson, G. C. (2015). The development of tourist destinations in the Gulf: Oman and Qatar compared. Tourism Planning & Development, 12(3), 350–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2014.947439

- Hill, A., & Steemers, J. (2017). Media industries and engagement. Media Industries Journal, 4(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0004.105

- Hsiao, C., Lee, Y., & Chen, W. (2015). The effect of servant leadership on customer value co-creation: A cross-level analysis of key mediating roles. Tourism Management, 49, 45–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.012

- Im, J., & Qu, H. (2017). Drivers and resources of customer co-creation: A scenario-based case in the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 64, 31–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.03.007

- Jangra, R., & Kaushik, S. P. (2018). Analysis of trends and seasonality in the tourism industry: The case of a cold desert destination- Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 7(1), 1–16.

- Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

- Ketonen-Oksi, S., Jussila, J., & Kärkkäinen, H. (2016). Social media based value creation and business models. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(8), 1820–1838. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-05-2015-0199

- Kolar, T., & Zabkar, V. (2010). A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tourism Management, 31(5), 652–664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.010

- Larsen, S. (2007). Aspects of a psychology of the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701226014

- Leavy, B. (2012). Collaborative innovation as the new imperative – design thinking, value co-creation and the power of “pull”. Strategy & Leadership, 40(2), 25–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/10878571211209323

- Lugosi, P. (2014). Mobilising identity and culture in experience co-creation and venue operation. Tourism Management, 40, 165–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.005

- Luo, N., Zhang, M., & Liu, W. (2015). The effects of value co-creation practices on building harmonious brand community and achieving brand loyalty on social media in China. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 492–499. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.020

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity arrangements of social space in tourist Settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/225585

- Mathis, E., Kim, H., Uysal, M., Sirgy, J., & Prebensen, N. (2016). The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 62–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.023

- Mazur, J., & Zaborek, P. (2014). Validating dart model. International Journal of Management and Economics, 44(1), 106–125.

- Mesoudi, A., Brookes, T., & Fitch, C. (2018). Oman: The Sea of Sand and Mists – Geographical. [online] Geographical.co.uk. http://geographical.co.uk/expeditions/item/ HYPERLINK “http://geographical.co.uk/expeditions/item/2479-the-sea-of-sand-and-mists"2479 HYPERLINK “http://geographical.co.uk/expeditions/item/2479-the-sea-of-sand-and-mists"-the-sea-of-sand-and-mists

- Michopoulou, E., & Moisa, D. (2018). Hotel social media metrics: The ROI dilemma. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76(Part A), 308–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.05.019

- Mossberg, L. (2007). A marketing approach to the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701231915

- Moufakkir, O., & Selmi, N. (2018). Examining the spirituality of spiritual tourists: A Sahara desert experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 108–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.09.003

- MTO. (2018). Oman. [online] Omantourism.gov.om. https://omantourism.gov.om/wps/portal/mot/tourism/oman/home/sultanate/regions/asharqiyah

- Munar, A., & Jacobsen, J. (2014). Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tourism Management, 43, 46–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.01.012

- Narayanan, Y., & Macbeth, J. (2009). Deep in the desert: Merging the desert and the spiritual through 4WD tourism. Tourism Geographies, 11(3), 369–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903032783

- Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2013). A typology of technology-enhanced tourism experiences. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(4), 340–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1958

- Olsen, K. (2002). Authenticity as a concept in tourism research. Tourist Studies, 2(2), 159–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/146879702761936644

- Pappas, N., & Michopoulou, E. (2019). Hospitality in a changing world. Hospitality & Society, 9(3), 259–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1386/hosp_00001_2

- Payne, A., Ulaga, W., Frow, P., & Eggert, A. (2018). Conceptualizing and communicating value in business markets: From value in exchange to value in use. Industrial Marketing Management, 69, 80–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.01.018

- Pérez-Liu, R., & Tejada-Tejada, M. (2020). Citizens' view of their relationship with tourism in a desert coastal area. Journal of Coastal Research, 95(sp1), 925-929. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2112/SI95-180.1

- Prahalad, C., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The future of competition. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Prebensen, N., Chen, J., & Uysal, M. (2016). Creating experience value in tourism.

- Prebensen, N., & Xie, J. (2017). Efficacy of co-creation and mastering on perceived value and satisfaction in tourists’ consumption. Tourism Management, 60, 166–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.001

- Ranjan, K., & Read, S. (2014). Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(3), 290–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0397-2

- Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Gouthro, M., & Moital, M. (2018). Customer-to-customer co-creation practices in tourism: Lessons from customer-dominant logic. Tourism Management, 67, 362–375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.02.010

- Rozenes, S., & Cohen, Y. (2010). Handbook of research on strategic alliances and value co-creation in the service industry.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2016). Research methods for business students.

- Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2010). Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006

- Sharda, K., & Chatterjee, L. (2011). Configurations of outsourcing firms and organizational performance. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 4(2), 152–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17538291111147991

- Singh, S., & Sonnenburg, S. (2012). Brand Performances in social media. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(4), 189–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2012.04.001

- Skaržauskaitė, M. (2013). Measuring and managing value co-creation process: Overview of existing Theoretical models. Social Technologies, 3(1), 115–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13165/ST-13-3-1-08

- Sorensen, A., Andrews, L., & Drennan, J. (2017). Using social media posts as resources for engaging in value co-creation. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(4), 898–922. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-04-2016-0080

- Steiner, C., & Reisinger, Y. (2006). Understanding existential authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 299–318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.08.002

- Suntikul, W., & Jachna, T. (2016). The co-creation/place attachment nexus. Tourism Management, 52, 276–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.026

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2016). SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research.

- Tiberghien, G. (2019). Managing the planning and development of authentic Eco-cultural tourism in Kazakhstan. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(5), 494–513. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1501733

- TOF. (2020). Oman. [online] Timesofoman.com. https://timesofoman.com/article/901134/oman/

- Tremblay, P. (2006). Desert tourism Scoping study. Report 12. Alice Springs: Desert knowledge cooperative research Centre. http://www.nintione.com.au/resource/DKCRCReport-12-Desert-Tourism-Scoping-Study.pdf

- Vada, S., Prentice, C., & Hsiao, A. (2019). The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 322–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.12.007

- Vaisnore, A., & Petraite, M. (2011). Customer Involvement into open innovation processes: A conceptual model. Social Sciences, 73(3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ss.73.3.793

- Vargo, S., & Lusch, R. (2012). Toward a better understanding of the role of value in markets and marketing. Emerald Group Pub.

- Vargo, S., & Lusch, R. (2014). Inversions of service-dominant logic. Marketing Theory, 14(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593114534339

- Wang, S. (2010). In search of authenticity in historic cities in transformation: The case of Pingyao. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- WEF. (2018). [online] Ev.am. http://ev.am/sites/default/files/WEF_TTCR_ HYPERLINK “http://ev.am/sites/default/files/WEF_TTCR_2017.pdf"2017 HYPERLINK “http://ev.am/sites/default/files/WEF_TTCR_2017.pdf.”pdf

- Woyo, E., & Amadhila, E. (2018). Desert tourists experiences in Namibia: A netnographic approach. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 7(3), 1–13.

- Yang, S., Lin, S., Carlson, J., & Ross, W. (2016). Brand engagement on social media: Will firms’ social media efforts influence search engine advertising effectiveness? Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5-6), 526–557. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2016.1143863