ABSTRACT

There is sufficient evidence in academic scholarship that points to the important role diaspora tourism plays for the economies of homeland communities and countries. Given previous research shows a decreased level of attachment to the homeland in the second generation of immigrants, this research seeks to explore the effects of childhood experiences on adult behaviours and outcomes in relation to diaspora tourism. The research reveals the important role played by families in transmitting knowledge, memories, traditions and other cultural practices to diaspora children. Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs), however, are neglecting to engage this lucrative market partly because communication strategies are aimed at adults of the diaspora and not at children. Based on these findings, we propose DMOs take a child-centred approach by actively engaging diaspora children to devise tourism marketing strategies that are child-friendly.

Introduction

Despite being seen as silent stakeholders in the tourism industry, children play a significant role in influencing decision-making within the family (Lugosi et al., Citation2016; Lugosi et al., Citation2020). There is, in fact, a growing body of knowledge that points to the active role played by children in influencing their parents’ spending patterns and purchase behaviour, particularly when it comes to holidays and vacations (Mohammadi & Pearce, Citation2020). The growing awareness that children have a role to play in society now and not just in the future is a significant development led by advancements in the interdisciplinary field of childhood studies (Canosa et al., Citation2020). The emerging focus in the social sciences on children's agency and participation in research, policy, and practice (Spyrou, Citation2019) is a promising direction for business, hospitality, and tourism disciplines that have traditionally lagged behind (Lugosi et al., Citation2020). Understanding how agency is enacted during childhood and in future tourism choices is essential for diaspora tourism due to the strong connection children establish with their homeland or Country of Origin (CoO) of their parents.

This research note is guided by the argument that Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs) need to work with diaspora families. Given previous research has shown a decreased level of place attachment to the homeland from the first to the second generation (Huang et al., Citation2018), this study proposes new ways to develop and maintain a stronger relationship with children from the diaspora. In this respect, some strategies will be presented to achieve this objective.

Conceptual framework

Destination Marketing Organisation (DMO)

The role of a DMO is quite broad as it goes from stimulating growth to supporting stakeholders, ensuring online visibility of the destination; coping with emergency crises; sustaining tourism resources; and maintaining appeal inter alia (Duffy & Kline, Citation2018). Interestingly, Page (Citation2019) highlights an important point regarding the strategies used by DMOs to improve the performance of destinations. According to the author, DMOs use traditional business tools such as branding strategies, internet, technology, segmentation strategies, etc. Less interest is placed on individuals as a strategy to boost the performance of the destination. As for assessing a destination's performance, DMOs usually evaluate against customer satisfaction, quality of relationship with the tourism industry stakeholders, benefits of the industry for the local economy, and so forth (Gowreesunkar et al., Citation2017). Less interest is shown for the diaspora market (Corsale & Vuytsyk, Citation2015) and children, in particular, as a potential target market (Séraphin, Citation2020).

Children and their participation in the tourism industry

Children are neither passive nor powerless (Hutton, Citation2016); however, historically, they have been marginalised in social research due to traditional views of childhood as a “subordinate group in need of protection in order to be prepared for adulthood” (Kehily, Citation2008, p. 5). Developments in the interdisciplinary field of childhood studies and international efforts to afford children full human rights – sanctioned by the most ratified international human rights treaty, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, Citation1989) – have contributed to a significant conceptual shift that recognises children's right to participate in matters that affect them, including tourism policy and planning (Canosa et al., Citation2019).

There is growing evidence in tourism scholarship that children play an essential role in the choice of family holidays (Lugosi et al., Citation2016; Schänzel & Yeoman, Citation2015). They are being referred to as co-creators of travel experiences with their parents (Khoo-Lattimore et al., Citation2015). Children can play a significant role in the sustainability of the tourism industry if they are actively included and engaged in tourism research, policy and planning (Canosa et al., Citation2020).

Meaningful consultation with children around tourism policy and planning concerns, however, is glaringly missing. Although research on and with children is gaining momentum in tourism research (Kerr & Price, Citation2018; Yang et al., Citation2020), there is an evident lack of attention to their participation in tourism planning, including communication and marketing strategies to improve the performance of destinations.

Diaspora and tourism

The diaspora is the geographic dispersion of people belonging to the same community (Bordes-Benayoun, Citation2002). According to Cohen (Citation1997), there are different types of diaspora, based on the reason for leaving the homeland, including victim/refugee diaspora; trade diaspora; imperial diaspora; labour diaspora; and cultural/hybrid/postmodern diaspora (Huang et al., Citation2018; Minto-Coy et al., 2016; UN DESA, Citation2020). Given diasporic communities are not homogeneous, there is little consistency in how identities and attachment to the homeland change over time (Huang et al., Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2019).

The children of first-generation migrants are generally referred to as second-generation immigrants, and their parents’ homeland experiences may be considerably different. While there is a vast amount of literature about first-generation immigrants (Atputharajah, Citation2016; Huang et al., Citation2018), second-generation diasporas members are slowly becoming a topic of interest amongst scholars and policymakers alike. While first-generation immigrants migrated to their host country, the second generation consists of those born in the host-country but have one or more parents born outside of the host country. Some scholars argue that having one parent born in the host country makes one part of the 2.5 generation (Jantzen, Citation2008), while others say that having moved to the host country during childhood makes one part of the 1.5 generation. However, the bulk of immigration literature does not strive to distinguish these populations, and there has yet to be a clear consensus on whether or not there are unique aspects in the settlement experiences of each group. Based on this understanding, and in an attempt to guide this research note, the second-generation diaspora is therefore described as those children with at least one parent from another country. Huang et al. (Citation2018) argue that children of the second generation may perceive their parents’ homeland as “a new place” on diaspora tourism holidays.

Despite their dispersion, migrant communities remain connected with their country of origin (CoO), as they recreate in their country of residence (CoR) in the form of brotherhoods and/or societies (Murdoch, Citation2017). Given the mobility of modern society, travelling back to the ancestral home is relatively easy compared to previous generations of migrants. As such, the term transnationalism is often used to refer to “the processes by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement” (Huang et al., Citation2013, p. 61).

Diasporas are generally very proud of their roots, involved in the life of their country of origin and country of residence, highly qualified, and contribute significantly to the territorial and economic intelligence of the country of origin (Paul & Michel, Citation2013; Wah, Citation2013). The diaspora also contributes to the tourism industry as consumers, tourists, and investors (Séraphin, Citation2020). When going back home (as tourists), the diaspora is keen to: eat and drink locally sourced products; visit their local town; reconnect with friends, families; buy cultural artifacts; stay in hotels, and dine in restaurants owned and managed by locals, as a way of supporting the local economy (Jadotte, Citation2012; Newland & Taylor, Citation2010; Wah, Citation2013). The Madeleine de Proust Theory (MPT) has been employed to interpret this behaviour connected to childhood and nostalgia (Bray, Citation2013). As the theory refers to the French novelist Marcel Proust who recalled his childhood after tasting a madeleine, a shell-shaped French sponge cake (Bray, Citation2013; Séraphin, Citation2021), the theory is often used in research related to the subconscious. MPT is also associated with other concepts, namely the concept of “habitus,” which is about re-enacting some behaviour triggered by a specific context (Lukajic, Citation2020; Meguro, Citation2015; Troscianko, Citation2013; Vries & Elferen, Citation2010); and “lieu de mémoire”, the materialisation of a community and/or individual heritage and/or memory (Benhaim, Citation2005). Nevertheless, Melyon-Reinette (Citation2009, Citation2010) argues that from the second generation onward, a phenomenon referred to as “dediasporisation” occurs among the younger generation, in other words, a lessening of attachment to the country of origin. This impacts negatively on diaspora tourism, particularly for destinations depending heavily on their diaspora for the survival of the tourism industry (Séraphin, Citation2020).

Methodology

Methodological foundation

This study's methodological foundation is two-fold: First, it is based on the effects of childhood experiences in adulthood. Literature supports the fact that there is a relationship between childhood experiences or circumstances and adult behaviour, attitude, and achievements (Simoes et al., Citation2016). Second, the Motivation Opportunity Ability (MOA) model is a framework used to highlight factors that either support or inhibit engagement and participation of individuals within their community (Jepson et al., Citation2013), is utilised.

Aims and objectives

This study explores the effects of childhood experiences on adult behaviours and outcomes in relation to diaspora tourism. Given previous research has shown a dediasporisation of the second generation, or decreased level of place attachment to the homeland (Huang et al., Citation2018; Melyon-Reinette, Citation2009, Citation2010), the objectives of this study are two-fold: a) To explore the role played by families in the transmission of knowledge, memories, traditions and other cultural practices about the homeland to diaspora children; b) To explore the role of DMOs in connecting with diaspora children. The study suggests that DMOs in general, but particularly DMOs of destinations relying on diaspora tourism, should rebuild connections with their target market from a very early stage of their lives through shared emotions to establish emotional attachment (Hang et al., Citation2020).

Method

This study is based on an online questionnaire sent to members (adults) of the diaspora. The survey questions were designed using a conceptual study by Séraphin (Citation2020) on childhood experience and dediasporisation. The focus of the questions is on transmission between generations. Literature suggests that holidays are legacy time during which transmissions (skills, values, practical knowledge) between generations occur (Boutte et al., Citation2017; Huang et al., Citation2016; Schänzel & Jenkins, Citation2016). The questionnaire was administered online using Google forms. An information sheet was provided at the beginning of the survey so that potential respondents had a full understanding of the objectives of the study; how data were stored, protected, and used; as well as the different options offered to them, such as withdrawing from the survey if they wished to do so. Members (adults) of the diaspora were individually contacted by the research team and asked to complete the survey. The survey was also shared via social networks such as LinkedIn and Facebook to reach a larger audience. Both platforms are widely used to improve the recruitment of research participants (Bonson & Bednarova, Citation2013; Möllera et al., Citation2018).

Apart from the demographic questions, the survey questions were measured with a Likert-type response format from 1 (never; not at all important; not at all; poor; disagree) to 5 (always; of critical importance; totally; excellent; strongly agree). The project received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of the lead author. Participation in the research was voluntary, and anonymity was ensured by complying with the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR).

Data analysis

The data collected were analysed using SPSS, a useful software to analyse quantitative data (Quinlan, Citation2011). The SPSS analysis was specifically focused on correlation, defined by Hammond and Wellington (Citation2013, p. 164) as: “the investigation of association or dependence between two variables so that X can be said to be associated with Y.” More specifically, the study used Pearson Product Moment Correlation, which is used to “measure the degree to which two variables are correlated or associated with each other when both of those variables are metric” (Silver et al., Citation2013, p. 216). The correlation coefficient and strength of association related to the Pearson Product Moment Correlation is presented in the table below ():

That said, this study is a pilot study, also called a small-scale version of a full study (Persaud, Citation2012; Van Teijlingen & Hundley, Citation2001). The results are therefore only indicative and not conclusive, let alone generalisable.

Findings and discussion

Over 56 individuals responded to the survey, with almost a perfect balance between respondents born in the country of origin of their parents and those born in their country of residence (see ). This fortunate outcome is rather positive for the validity and reliability of the pilot study.

Table 1. Demographic information.

Family influence: moderate to strong correlations

Family influence plays an important role in transmitting the knowledge, memories, traditions, and other cultural practices about the homeland to diaspora children, thus maintaining the connection between the younger generation of the diaspora and the country of origin ().

Table 2. Correlation table.

Existing research on diaspora has identified language as contributing to the connection between the country of origin and the younger generation from the diaspora. In some Vietnamese communities, heritage camp programmes around language are put in place for children as young as three years old (Williams, Citation2001). Children's fluency level is also a criterion in terms of attachment with the country of origin (Huang et al., Citation2016; Mandel, Citation1995). Indeed, food, drink, and music have been identified by many researchers as having a strong potential to foster a sense of belongingness within a community (Moscardo et al., Citation2017).

DMOs’ influence: non-existent to strong correlations

The communication strategy of DMOs toward the diaspora () is lacking (.208) and inefficient in terms of keeping the diaspora up to date (.446). The DMOs lack of communication toward the diaspora could be explained by the fact that they do not perceive the diaspora as a good enough market (Corsale & Vuytsyk, Citation2015), which is a mistake highlighted by the correlation () between the level of engagement of the diaspora and the level of communication between the diaspora and the DMOs (.653).

Table 3. Correlation table.

DMOs are neglecting to engage this lucrative market partly because communication strategies are aimed at adults of the diaspora and not children. Indeed, most of the respondents had barely attended any events related to the country of origin of their parents as children (). DMOs are failing to market the homeland destination to second-generation diaspora children because their marketing and communication strategies are not child-centred. Since the family is the main conduit for transmitting knowledge, DMOs need to work with diaspora families by actively engaging diaspora children in consultation to devise child-friendly destination marketing campaigns.

Table 4. Correlation table.

DMOs: toward child-friendly marketing campaigns

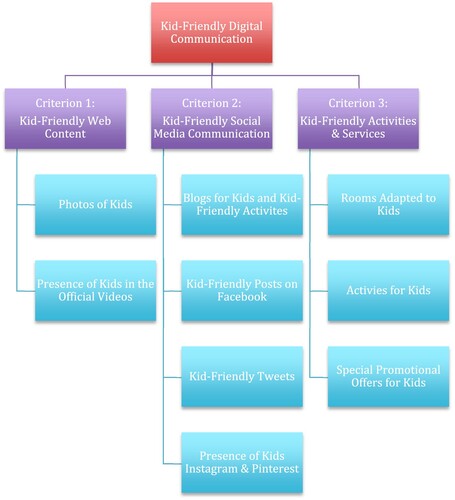

Although the findings from this small-scale pilot study are by no means conclusive, there is evidence to suggest that DMOs need to develop and maintain a stronger relationship with children from the diaspora. We propose the marketing strategies aimed at children should be developed in consultation with them. The kid-friendly digital communication framework (), created by Zaman et al. (Citation2020), may be of interest when developing such child-friendly marketing campaigns.

Figure 1. Framework for Kid-Friendly Digital Communication Evaluation. Source: Zaman et al. (Citation2020).

That said, it is also suggested that the above model should consider the following:

The emergence of the phenomenon of adultisation which involves children engaging in adults’ behaviour (Mardon, Citation2011). As a result, some of the communication codes used for adults’ marketing campaigns should also be used in marketing campaigns aimed at children (Dosquet et al., Citation2020).

The three layers that trigger children's interests in tourism products and services (or a destination): 1) The top layer includes novelty, nature, social relationships, and excitement; 2) the second layer is about comfort and escape, independence, recognition, loneliness, and self-esteem; 3) the final layer includes experience, romance, and nostalgia (Mohammadi & Pearce, Citation2020).

Critical features of holiday destinations for children: Seaside and sunny destinations are very popular with children. Some destinations are also very popular such as France, the USA, Spain, and the United Kingdom (Ghidouche & Ghidouche, Citation2020).

Conclusion

This research note's main purpose was to discuss the influential role of diaspora children in choosing family holiday destinations and the importance of working with them to develop child-friendly marketing strategies. In this respect, the pilot study sought to explore the role of families in the transmission of social capital about the homeland to diaspora children and the role of DMOs in connecting with diaspora children.

Findings suggest that while families play an important role in maintaining the connection between the younger generation of the diaspora and the country of origin, DMOs are neglecting to target this lucrative market. Given the small-scale nature of this pilot study, more in-depth qualitative research is needed to ascertain whether DMOs are indeed failing to market the homeland destination to second-generation diaspora children.

Our pilot study suggests that most respondents had barely attended any events related to the country of origin of their parents as children. Given previous research has established that children are important influencers in family holiday decisions (Lugosi et al., Citation2016) and a potentially overlook diaspora tourism market (Séraphin, Citation2020), this study suggests there is a pressing need for DMOs to work with diaspora families.

We suggest DMOs of destinations relying on diaspora tourism should adopt a child-centred approach and rebuild connections with their target market from a very early stage of their life. DMOs could develop suitably child-friendly marketing strategies in consultation with children of the diaspora, as well as organise cultural and family-oriented fun events (e.g. cooking, handicraft workshops) in the country of residence in order to strengthen the emotional ties with the homeland and directly in line with the Madelaine de Proust Theory (MPT) of childhood nostalgia (Séraphin, Citation2021). Ultimately, children are important tourism stakeholders who need to be meaningfully engaged in tourism planning, including communication and marketing strategies to improve the performance of destinations (Canosa et al., Citation2019).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Atputharajah, A. (2016). Hybridity and integration: a look at the second-generation of the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora in Toronto, Research Paper submitted to Ryerson University.

- Benhaim, A. (2005). From Baalbek to Baghdad and beyond Marcel Proust's foreign memories of France. Journal of European Studies, 35(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047244105051154

- Bonson, E., & Bednarova, M. (2013). Corporate LinkedIn practices of Eurozone companies. Online Information Review, 37(6), 969–984. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-09-2012-0159

- Bordes-Benayoun, C. (2002). Les diasporas, dispersion spatiale, expérience sociale. Autrepart, 22(2), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.3917/autr.022.0023

- Boutte, G., Johnson, G. L., Wynter-Hoyte, K., & Uyota, U. E. (2017). Using African diaspora literacy to heal and restore the souls of young black children. International Critical Childhood Policy Studies Journal, 7(1), 66–79.

- Bray, P. (2013). Forgetting the madeleine: Proust and the neurosciences. Progress in Brain Research, 205, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63273-9.00003-4

- Canosa, A., Graham, A., & Wilson, E. (2019). Progressing a child-centred research agenda in tourism studies. Tourism Analysis, 24(1), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354219X15458295632007

- Canosa, A., Graham, A., & Wilson, E. (2020). Growing up in a tourist destination: Developing an environmental sensitivity. Environmental Education Research, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1768224

- Cohen, R. (1997). Global diasporas: An introduction. University of Washington Press.

- Corsale, A., & Vuytsyk, O. (2015). Long-distance attachment and implications for tourism development: The case of Western Ukrainian diaspora. Tourism Planning & Development, 13(1), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2015.1074099

- Dosquet, F., Lorey, T., & Ambaye, M. (2020). The role of children in marketing. A state of the art: Application in tourims marketing. In H. Séraphin, & V. Gowreesunkar (Eds.), Children in hospitality and tourism. Marketing and managing experiences (pp. 155–166). De Gruyter.

- Duffy, L., & Kline, C. (2018). Complexities of tourism planning and development in Cuba. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(3), 211–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1440830

- Ghidouche, K., & Ghidouche, F. (2020). Good holidays in children’s voices and drawings. In H. Séraphin, & V. Gowreesunkar (Eds.), Children in hospitality and tourism. Marketing and managing experiences (pp. 89–104). De Gruyter.

- Gowreesunkar, G. B., Seraphin, H., & Morisson, A. (2017). Destination marketing organisations. Roles and challenges. In D. Gursoy, & C. G. Chi (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of destination marketing (pp. 16–34). Routledge.

- Hammond, M., & Wellington, J. (2013). Research methods. The key concepts. Routledge.

- Hang, H., Aroean, L., & Chen, Z. (2020). Building emotional attachment during COVID-19. Annals of Tourism Research, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103006

- Huang, W. J., Haller, W., & Ramshaw, G. P. (2013). Diaspora tourism and homeland attachment: An exploratory analysis. Tourism Analysis, 18(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354213X13673398610691

- Huang, W. J., Hung, K., & Chen, C. C. (2018). Attachment to the home country or hometown? Examining diaspora tourism across migrant generations. Tourism Management, 68, 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.02.019

- Huang, W. J., Ramshaw, G., & Norman, W. C. (2016). Homecoming or tourism? Diaspora tourism experience of second-generation immigrants. Tourism Geographies, 18(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2015.1116597

- Hutton, M. (2016). Neither passive nor powerless: Reframing economic vulnerability via resilient pathways. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(3–4), 252–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1118144

- Jadotte, E. (2012). Brain drain, brain circulation and diaspora networks in Haiti, UNCTAD.

- Jantzen, L. (2008). Genetic distance, immigrants’ identity, and labor market outcomes. Canadian Diversity, 6(2), 7–12.

- Jepson, A., Clarke, A., & Ragsdell, G. (2013). Applying the motivation-opportunity-ability (MOA) model to reveal factors that influence inclusive engagement within local community festivals: The case of UtcaZene 2012. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 4(3), 186–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-06-2013-0011

- Kehily, M. J. (2008). Understanding childhood. In M. J. Kehily (Ed.), An introduction to childhood studies (2nd ed) (pp. 1–16). McGrath-Hill Education.

- Kerr, M. M., & Price, M. (2018). “I know the plane crashed”: Children's perspectives in dark tourism. In P. R. Stone, T. Seaton, R. Sharpley, & L. White (Eds.), The Palgrave Macmillian handbook of dark tourism studies (pp. 553–583). Palgrave Macmillian.

- Khoo-Lattimore, C., Prayag, G., & Cheah, B. L. (2015). Kids on board: Exploring the choice process and vacation needs of Asian parents with young children in resort hotels. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 24(5), 511–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2014.914862

- Li, T. E., McKercher, B., & Chan, E. T. H. (2019). Towards a conceptual framework for diaspora tourism. Current Issues, https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1634013

- Lugosi, P., Golubovskaya, M., Robinson, R. N. S., Quinton, S., & Konz, J. (2020). Creating family-friendly pub experiences: A composite data study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.20202.102690

- Lugosi, P., Robinson, R. N. S., Golubovskaya, M., & Foley, L. (2016). The hospitality consumption experiences of parents and carers with children: A qualitative study of foodservice settings. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 54, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.01.012

- Lukajic, R. D. (2020). A la recherche du temps perdu: Des fantasmes à l’ esthétique idéaliste dans l’ œuvre de Proust. https://doi.org/10.46630/phm.12.2020.33

- Mandel, R. (1995). Second-generation noncitizens: Children of the Turkish migrant diaspora in Germany. In S. Stephens (Ed.), Children and the politics of culture (pp. 265–281). Princeton University Press.

- Mardon, A. (2011). La generation Lolita. Réseaux, 4(168/169), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.3917/res.168.0111

- Meguro, J. (2015). La nourriture chez Marcel Proust. Littératures. Université Sorbonne Paris Cité.

- Melyon-Reinette, S. (2009). Haïtiens à New York City: Entre Amérique noire et Amérique multiculturelle. L’Harmattan.

- Meylon-Reinette, S. (2010). De la dédiasporisation des jeunes Haïtiens à New-York, Etudes caribéennes [Online], http://etudescaribeennes.revues.org

- Mohammadi, Z., & Pearce, P. (2020). Making memories: An empirical study of children's enduring loyalty to holiday places, children and tourism, DeGruyter publication. In H. Séraphin, & V. Gowreesunkar (Eds.), Children in hospitality and tourism. Marketing and managing experiences (pp. 135–154). De Gruyter.

- Möllera, C., Wang, J., & Nguyen, H. T. (2018). #Strongerthanwinston: Tourism and crisis communication through Facebook following tropical cyclones in Fiji. Tourism Management, 69, 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.05.014

- Moscardo, G., Konovalov, E., Murphy, L., & McGehee, N. G. (2017). Linking tourism to social capital in destination communities. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dmm.2017.10.001

- Murdoch, S. (2017). Children of the diaspora. The homecoming of the second-generation Scot in the seventeenth century. In M. Harper (Ed.), The return movement of emigrants, 1600–2000 (pp. 55–76). Manchester University Press.

- Newland, K., & Taylor, C. (2010). Heritage tourism and nostalgia trade: A diaspora niche in the development landscape. Migration Policy Institute.

- Page, S. J. (2019). Tourism management. Routledge.

- Paul, B., & Michel, T. (2013). Comment juguler les limitations financières des universités haïtiennes? Haïti Perspectives, 2(1), 57–63.

- Persaud, N. (2012). Pilot study. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of research design (pp. 12–18). Sage.

- Quinlan, C. (2011). Business research methods. Cengage.

- Schänzel, H., & Jenkins, J. (2016). Non-resident fathers’ holidays alone with their children: Experiences, meanings and fatherhood. World Leisure Journal, 59(2), 156–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2016.1216887

- Schänzel, H. A., & Yeoman, I. (2015). Trends in family tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 1(2), 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2014-0006

- Séraphin, H. (2020). Childhood experience and (De)diasporisation: Potential impacts on the tourism industry. Journal of Tourism, Heritage and Service Marketing, 6(3), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4056264

- Séraphin, H. (2021). What is your tourism Madeleine de Proust? Anatolia, https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1861638

- Silver, L., Stevens, R., Wrenn, B., & Loudon, D. (2013). The essentials of marketing research. Routledge.

- Simoes, N., Crespo, N., & Moreira, S. B. (2016). Individual determinants of self-employment entry: What do we really know? Journal of Economic Surveys, 30(4), 783–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12111

- Spyrou, S. (2019). An ontological turn for childhood studies? Children & Society, 33(4), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12292

- Troscianko, E. T. (2013). Cognitive realism and memory in Proust's madeleine episode. Memory Studies, 6(4), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698012468000

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child (UNCRC). Office of the High Commisioner for Human Rights. http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/crc.htm

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2020, July 3). International migrant at mid-year 2019. https://migrationdataportal.com/fr/themes/population-de-migrants-internationaux

- Van Teijlingen, E., & Hundley, V. (2001). The importance of pilot studies. Social Research Update, 35, University of Surrey, 1360–7898.

- Vries, I., & Elferen, I. V. (2010). The musical Madeleine: Communication, performance, and identity in musical ringtones. Popular Music and Society, 33(1), 6174. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007760903142756

- Wah, T. (2013). Engaging the Haitian Diaspora. Cairo Review, 9.

- Williams, I. A. (2001). Diversity and diaspora: Vietnamese adopted as children by non-Asian families. The Review of Vietnamese Studies, 1(1), 1–18.

- Yang, M. J. H., Chiao Ling Yang, E., & Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2020). Host-children of tourism destinations: Systematic quantitative literature review. Tourism Recreation Research, 45(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1662213

- Zaman, M., Dauxert, T., & Michael, N. (2020). Kid-friendly digital communication for hotels and service adaptation: Empirical evidence from family hotels. In H. Séraphin, & V. Gowreesunkar (Eds.), Children in hospitality and tourism. Marketing and managing experiences (pp. 121–134). De Gruyter.