ABSTRACT

Tourism has been a major economic pillar in numerous cities. A sustainable tourism development is vital while residents’ support is the lynchpin of success. The current study examines if and how support for sustainable tourism development is affected by place perception. Specifically, the mediating role of place attachment and moderating role of length of residency were examined. Drawn from a survey with 568 Macao residents, results show that place perception was a significantly positive contributor to residents’ support because of the higher place attachment. While length of residency strengthened the positive place perception—place attachment link, the place attachment—support link was not contingent on length of residency. The findings enrich the literature by examining the determinants of support for sustainable tourism development, the underlying mechanism, and the alternative role of length of residency. Useful implications for destination governors are discussed.

1. Introduction

The concept of place has been widely suggested as the lynchpin to investigate the reason for people to visit a destination (Walker & Ryan, Citation2008). As prior research noted, “the individuals’ living place is not just a physical element, but it includes all the mental and sensational factors of the individuals” (Shouran et al., Citation2019, p. 90). The feeling that residents attach to their places influences their attitude towards the changes taken place in their living place (Gursoy & Rutherford, Citation2004; Mesch & Manor, Citation1998). In other words, place attachment shaped their attitude towards planning and development of the city (Davenport & Anderson, Citation2005). However, for a city that heavily relies on tourism industry to support the economy, tourism development is indispensable. Sustainability of the tourism industry should be the city governor’s concern while maximizing residents’ support to sustainable tourism development is crucial. Although the empirical evidences about influences of place perception and place attachment on residents’ attitude towards tourism development are not scarce (Lalli & Thomas, Citation1989; Ramkissoon & Nunkoo, Citation2011; Stylidis, Citation2018; Stylidis et al., Citation2014; Vorkinn & Riese, Citation2001), their influences on residents’ support for sustainable tourism development remain unknown. It is noteworthy that residents’ positive attitude towards tourism development does not mean they would support sustainable tourism development as they are conceptually different. Moreover, attitude towards tourism development can be driven by the short-term benefits at the expense of long-term benefits, whereas sustainable tourism development concerns the long-term net benefits. To fill the literature gap, this study explores if support for sustainable tourism development is predicted by place perception and attachment.

As noted earlier, sustainable tourism development is particularly important for a destination that largely relies on tourism to support its economy. Macao was selected as the case for this study because over 70% of its economy is borne by the tourism industry (Macao Statistics and Census Service, Citation2020a). In 2019, it has recorded 39.4 millions of tourist arrivals (Macao Statistics and Census Service, Citation2020b), but the small size of Macao (only about 31 km2) mandates a frequent and close interaction between residents and tourists. In addition to the economic impact of tourism, the social and environmental impacts on Macao community are substantial (Fong et al., Citation2016), which provides an ideal research setting for this study to examine the influences of place attachment and place perception on residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. While most prior research about place perception and attachment was conducted with the setting of rural areas (Morales Lopez, Citation2012; Stylidis, Citation2018; Xu et al., Citation2009), the focus on Macao which is an urbanized destination will add knowledge to related literature. The findings will provide significant implications for Macao governor about whether it should devote effort and resources on shaping residents’ place perception and attachment, in order to facilitate its work on sustainable tourism development.

To provide further theoretical implications, this study explores if place perception influences residents’ support for sustainable tourism development because of their place attachment. Although length of residency influences place attachment (Hashemnezhad et al., Citation2012; McCool & Martin, Citation1994), we do not know if length of residency has any other function in its interaction with place attachment. This study enriches the literature by examining its interaction with place perception in affecting place attachment and its interaction with place attachment in influencing support for sustainable tourism development. The findings about the moderating role of length of residency will enable Macao tourism planners to identify the group of residents who are more suitable for serving as ambassadors for promoting sustainable tourism development.

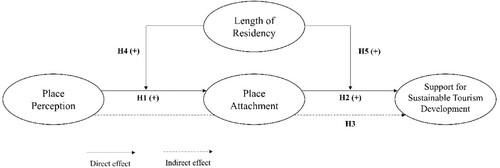

In sum, the objectives of this study are threefold. First, place perception as an antecedent of and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development as a consequence of place attachment are examined. Second, the mediating role of place attachment is investigated. Third, length of residency as a moderator on the paths of place—attachment and attachment—support is examined. The next section presents a critical review of literature that support the formulation of hypotheses. Following that, Sections 3–5 will articulate the methodology and results, discussion of findings, and conclusions respectively.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

2.1. Sustainable tourism development

Sustainability was first used in Europe and United States as the solution of the problems caused by urban development in the nineteenth century (Choi & Sirakaya, Citation2005). Since 1980, sustainable development becomes a critical issue in resolving the problem of degrading natural resources during economic development (Hall, Citation2007). According to the World Tourism Organization (Citation2003, p. 31),

sustainable tourism development meets the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunity for the future. It is envisaged as leading to management of all resources in such a way that economic, social, and aesthetic needs can be fulfilled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity, and life support system.

Following this reasoning, this study defines sustainable tourism as the tourism development that aims at meeting the needs of tourists and residents but at the same time not compromising future opportunities of the destinations.

According to Swarbrooke (Citation2010), sustainable tourism comprises of three aspects: economic, environmental and social. Economic sustainable tourism concerns maximizing economic benefits, minimizing operating cost, and at the same time distributing the country income to different groups equally in the society throughout the process of tourism development. The environmental aspect concerns preservation of the environment through promotion, education, and enforcement of environmental-friendly measures. Social aspect concerns the minimization of tourism negative impact on the local community in the realms of residents’ daily life and culture. Sustainable tourism development is a hot topic over the past decades and has gained a lot of attention among the tourism scholars and researchers (Nicholas et al., Citation2009). Although sustainable tourism development is highly recommended in contemporary tourism, its importance may vary with individual residents who hold different perceptions and interests. However, the determining factors remain unknown. This study proposes place perception as a predicting factor and place attachment as an explanatory factor.

2.2. Place perception

Place perception refers to residents’ evaluation of a place which features some unique characteristics aroused from physical environment and locals (Schroeder, Citation1996; Stylidis et al., Citation2014; Tasci & Gartner, Citation2007). It has been shown as a key factor that influences residents’ supportiveness for tourism development (Stylidis et al., Citation2014). When studying place perception, researchers always focused on its social aspect but neglected the contribution of physical environment to place meanings (Stedman, Citation2003). Indeed, a city development project which changes the physical environment shapes people’s perception of the place (Stylidis, Citation2018). People are not just tied by the friends and relatives around but also affected by the spatial and physical settings like climate and natural sceneries (Lewicka, Citation2011; Stedman, Citation2003). Therefore, a valid measure of place perception should consist of both social and physical settings of the place.

2.3. Place attachment

Place attachment, an environmental psychology concept, refers to the sense of place (Altman & Wohlwill, Citation2012). Sense of place is a comprehensive idea that describes the meaning generated from human towards a place, and it consists of place spirit and identity (Altman & Wohlwill, Citation2012; Hidalgo & Hernández, Citation2001). As Hashemnezhad et al. (Citation2012, p. 5) noted: “Men feels places, percept them and attached meaning to them”. Place attachment is a psychological bond between human and place and it can happen within a house, a classroom, workplace, a city or a country (Shouran et al., Citation2019). The psychological bond can be manifested in a person missing a place when he/she leaves the place (Vong et al., Citation2015). A place without meaning is only a space. In other words, a space is turned to a place when a person attaches meaning to it (Altman & Wohlwill, Citation2012). In this study, place attachment is defined as the psychological bond between residents and the place.

2.4. Formulation of hypotheses

2.4.1. Place perception and place attachment

Place attachment can be affected by various factors such as demographic, family, physical, social and economic components (Lestari & Sumabrata, Citation2018). For example, people with more relatives and close friends nearby are more attached to their living places (Mesch & Manor, Citation1998). Gender difference was inconclusive as a prior study found higher attachment among female than male because of the psychological bond between their children and the place (Tartaglia, Citation2006), whereas another study did not find any gender difference on place attachment (Mesch & Manor, Citation1998). Moreover, age along with the length of residency have effects on place attachment (Knez, Citation2005).

While place attachment is emotion-laden, place perception is a cognitive evaluation of the place. Following the cognitive-emotion framework, Prayag and Ryan (Citation2012) suggested place perception as an antecedent of place attachment. Place perception and place attachment are positively correlated with each other which means that people who appreciate the social and physical environment of their place will be more attached to the place (Matarrita-Cascante et al., Citation2010; Rollero & De Piccoli, Citation2010; Stylidis, Citation2018). This connection has been further proved by geographic studies which emphasized the way physical setting shapes place attachment (Brown & Raymond, Citation2007; Brown et al., Citation2015; Brügger et al., Citation2011). When the change of urban landscape is positively evaluated, residents’ place attachment will rise. Accordingly, residents who form a negative image towards a place have a lower level of place attachment (Bonaiuto et al., Citation1996; Chow & Healey, Citation2008), whereas people who perceived positively towards environment such as infrastructure and ambience of their place will add value to place attachment (Isa et al., Citation2020). Additionally, when a person is satisfied with a place, he or she will have a higher intention to stay in that place (Chen & Dwyer, Citation2018). However, it is also possible that satisfaction on physical environment does not lead to place attachment (Brown, Citation1993), for instance, when place meaning is not formed through experience (Stedman, Citation2003; Tuan, Citation2001). Nonetheless, previous empirical evidences generally suggest a positive relationship between place perception and place attachment. So, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1: Place perception positively predicts place attachment

2.4.2. Place attachment and support for sustainable tourism development

To our best understanding, tourism literature lacks an examination of place and attitude towards sustainable tourism development. However, some previous studies shed light to their plausible relationship. Numerous studies have noted the importance of place attachment in shaping residents’ attitude towards future development (Dwyer et al., Citation2019; Shen et al., Citation2019; Stylidis, Citation2018; Vorkinn & Riese, Citation2001; Woosnam et al., Citation2018). While long-term benefits are their goals, people with high place attachment are more engaged in environmental responsible behavior and more likely to preserve local resources (Cheng & Wu, Citation2015; Ramkissoon et al., Citation2013; Tang et al., Citation2008; Vaske & Kobrin, Citation2001). Their responsible behavior reflects their endorsement to sustainable development of a city. Following this reasoning, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2: Place attachment positively predicts support for sustainable tourism development

2.4.3. Place attachment as a mediator

Politicians largely rely on residents’ support to realize their tourism development plan, so that shaping a positive place perception is crucial (Schroeder, Citation1996). In line with this advocacy, numerous studies have reported that place perception positively affects people’s support for tourism development (Hsu et al., Citation2004; Krishnaswamy et al., Citation2018; Kang, Citation2019; Leisen, Citation2001; Schroeder, Citation1996; Stylidis, Citation2018). Residents who hold a better place perception are more willing to recommend their place to potential tourists (Stylidis, Citation2020). They would also consider more about the positive impacts of tourism and hence support tourism development (Stylidis et al., Citation2014). However, it is noteworthy that residents’ support for tourism development may be due to certain benefit, for example, economic benefits, that they gained. They may not be willing to sacrifice part of the economic gain in exchange for a lower cost to the society such as pollution. In this sense, residents who support tourism development do not necessarily support sustainable tourism development. This argument, however, may not be valid as evaluation of tourism impact is not limited to economic aspect. Residents generally consider all aspects including the social and environmental impacts.

Nonetheless, it should be reasonable to assume a relationship between place perception and support for sustainable tourism development as residents holding favorable perception of their place evaluate tourism impacts positively (Stylidis et al., Citation2014) and the positive impacts would lead to support for sustainable tourism development (Eslami et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, prior research suggested that increasing people’s overall positive understanding of their place is instrumental to their supportiveness for sustainable development (Zhu et al., Citation2017). If a person appraises the place that he/she is living in, he/she will be more likely to engage in environmentally responsible behavior (Stedman, Citation2002). Therefore, a positive relationship between place perception and attitude towards sustainable tourism development is plausible. Given the above hypotheses (Hypotheses 1 and 2), place attachment is likely to be the explanatory factor and hence it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3: Place attachment mediates the positive relationship between place perception and support for sustainable tourism development.

2.4.4. Length of residency

Length of residency has traditionally been suggested as an essential variable in tourism impact studies (Khoshkam et al., Citation2016; Sinclair-Maragh, Citation2017; Tournois & Djeric, Citation2019) and a key indicator of attachment to the community (Sheldon et al., Citation1984; Um & Crompton, Citation1987). Coherent empirical evidences were found in previous studies. It was found that residents who lived longer in a place will have a higher attachment level (Hashemnezhad et al., Citation2012; McCool & Martin, Citation1994). The place attachment is particularly high if it is a living place in one’s childhood (Vidal et al., Citation2010). Prior research revealed that a longer residency fosters a resident’s sense of place because of the social relations with other residents, whereas short-term residents’ sense of place stems from the quality of environment (Jorgensen & Stedman, Citation2006). Soini et al. (Citation2012) found that senior residents appreciate the natural landscape of their city which has lots of meanings to them. In sum, the positive relationship between length of residency and place attachment is evident. On the other hand, prior research has suggested a connection between length of residency and attitude towards tourism development (Allen et al., Citation1988), but empirical evidence was lacked (Pham & Kalsom, Citation2011; Sinclair-Maragh, Citation2017). These arguments set the ground for our propositions of the moderating role of length of residency on the links of place perception—place attachment and place attachment—support for sustainable tourism development.

2.4.5. Moderating effect of length of residency

Given the positive relationship between place perception and place attachment in Hypothesis 1, if the place is positively (negatively) evaluated, place attachment may further be increased (decreased) by the evaluation built on experiences accumulated throughout a long period of time. In other words, a resident who has stayed longer in a place and has a positive (negative) place perception is likely to be constructed a stronger (weaker) psychological bond with the place. Hence, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 4: Length of residency enhances the positive relationship between place perception and place attachment

Sustainable tourism development is understood as a vehicle towards the long-term benefit of the place. Residents who stay long in the place may want to see the benefit in the future. It may be more salient for residents who have a strong psychological bond with the place (i.e. high place attachment). By contrast, if their place attachment is low, residents may not care about the long-term benefit of the place, irrespective of how long they stay there. So, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 5: Length of residency enhances the positive relationship between place attachment and support for sustainable tourism development

To summarize, presents the conceptual model.

3. Method and results

3.1. Respondents and procedure

This study adopted questionnaire survey to collect the data. While the Macao residents were the target respondents, a corresponding screening question was asked at the beginning of the survey. Additionally, a second screening question was asked to filter out residents who were under 18. Recruitment of samples was conducted by dispatching the survey weblink via WeChat. Convenience and snowball sampling methods were adopted. The weblink was sent to the investigator’s WeChat connections while these receivers were also requested to forward the weblink to their connections. Eventually 648 completed responses were received. Among which, 77 were excluded by the screening questions. A total of 571 responses were retained. The criterion of z-values beyond the range of −4 and 4 was adopted to eliminate any outliers. Three outliers were identified and hence 568 responses were retained for analysis.

Respondents’ characteristics are shown in . Almost 70% of the respondents were female. They tended to be young as almost 40% of the respondents were aged within the range of 18 and 24. A majority of them (over 70%) held a Bachelor’s degree or above. Most respondents were single (65.8%). Over half of them earned a monthly income below 20,000 Macao dollars. About two-third of them have resided in Macao for less than 30 years (66.6%).

Table 1. Profile of respondents (n = 568).

3.2. Measures

The selection of measurement items was based on the definitions of constructs in our literature review and our discussions of the relevancy of these items to the Macao tourism and community situations. Place perception was operationalized by nine items drawn from previous research (Stylidis, Citation2018). The three measurement items of place attachment were borrowed from Kasarda and Janowitz (Citation1974). Regarding support for sustainable tourism development, the seven items were borrowed from Choi and Sirakaya (Citation2005) and Nicholas et al. (Citation2009) to enhance the comprehensiveness of the measure. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1: “strongly disagree” to 5: “strongly agree”). As Macao residents were the target respondents, the questionnaire was translated from English to Chinese. Back-translation was conducted to ensure semantic equivalence. A pilot test was conducted among local residents who were above 18 and none of them expressed difficulties in understanding the survey items. The measurement items are listed in .

Table 2. Mean values, standard deviations, outer loadings and cross loadings of items.

3.3. Measurement model

The examination of hypotheses was conducted using Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). To enhance the representativeness of samples, we weighted the data according to gender and age distributions of Macao population as at the end of 2019 (Macao Statistics and Census Service, Citation2020c), because data collection was conducted in the 1st quarter of 2020. Calculations of weights are shown in . The weighting variable was created based on the values in the columns of weightings in . All the analyses were performed with the weighting variable.

Table 3. Weighting gender and age data used in model testing.

In PLS-SEM, an item should be retained if its outer loading is greater than or equal to 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2017). The measurement model testing results show an AVE under 0.5 for place perception. Therefore, the place perception item which has the lowest outer loading was eliminated. This process was repeated until the AVE is above 0.5, at which four items were retained (see for the retained items and its notes for the eliminated items). The AVEs of other constructs are above 0.5 while all composite reliability, Cronbach’s α, and rho_A are above the threshold value of 0.7 (see ). Therefore, internal consistency and convergent validity of measure are supported. Discriminant validity was assessed based on three criteria: (1) outer loadings are greater than cross-loadings for each item (see ); (2) square-root of AVE of a construct is greater than its correlation with other constructs (see ); (3) the largest Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) value is below 0.90 and the bias-corrected confidence intervals do not include 1. Based on these results, discriminant validity is supported.

Table 4. Assessment of reliability and validity of constructs.

3.4. Common method bias

To assess if common method bias exists, this study used two statistical approaches. First, the Harman single-factor test generates more than one factor (three factors) and the first factor explains 46.37% of variance (below the recommended threshold of 50%). Second, the Unmeasured Latent Marker Construct (ULMC) method was adopted to further examine the common method bias (Liang et al., Citation2007). As shown in , most method factor loadings (R2 values) (5/14) are not statistically significant. The substantive factor loadings (R1 values) are much greater than the absolute values of R2 for each item. The ratio of average R12 to average R22 is 58:1, which is greater than the passing value (42:1) in Liang et al. (Citation2007). As such, it can be concluded that common method bias is not an issue for the current study.

Table 5. Common method bias analysis—unmeasured latent marker construct.

3.5. Testing of hypotheses

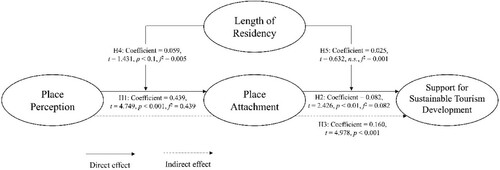

As the moderator, length of residency, is an ordinal variable. The two-stage method was used to test the moderating effect. Before analyzing the model paths, multicollinearity issue needs to be evaluated. The highest VIF value is 1.439 and hence multicollinearity is not a concern for this study. shows the results of hypothesis tests. Consistent with H1, place perception is significantly associated (positive) with place attachment. H2 is also confirmed as place attachment has a significantly positive relationship with support for sustainable tourism development. While place perception positively predicts support for sustainable tourism development, place attachment mediates the positive predictive relationship from place perception to support for sustainable tourism development, so that H3 is supported. Regarding the two moderating effects of length of residency, it marginally moderates the place perception—place attachment relationship (H4), but does not moderate the place attachment—support relationship (H5). For H4, in particular, the positive relationship between place perception and place attachment grows with the length of residency.

The predictive relevance of the structural model is deemed satisfactory because the Q2 values are positive. The R2 values of place attachment (0.305) and support (0.290) are statistically significant (p < .001) ().

Figure 2. The conceptual model and results.

Note: Place perception → Support for sustainable tourism development (coefficient = 0.289, t = 5.393, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.085), Length of residency → Place attachment (coefficient = 0.010, t = 0.224, n.s., f2 = 0.000), and Length of residency → Support for sustainable tourism development (coefficient = −0.162, t = 2.900, p < 0.05, f2 = 0.037).

4. Discussion of findings

This paper explores place perception as a predictor of residents’ support for sustainable tourism and place attachment as the explanatory factor. In line with our conjectures, a positive evaluation of the place (place perception) helps foster place attachment which lends credence to support for sustainable tourism development, while the mediating role of place attachment is significant. The influence of place perception on place attachment is contingent on length of residency, whereas the effect of place attachment on support does not vary with length of residency.

Prior research reported that place attachment helps destination obtain support for tourism development (Cheng & Wu, Citation2015; Ramkissoon et al., Citation2013; Tang et al., Citation2008; Vaske & Kobrin, Citation2001). The findings in this study extend the predicting role of place attachment to support for sustainable tourism development. The psychological bond between residents and their place might motivate them to strive for a continuous prosperity of tourism at the minimum negative impact. Indeed, recent years have frequently seen Macao residents, who expressed their emotional attachment with the city, voiced out their concerns about the negative social impact of tourism, for example, overtourism. They would like to see a balance between tourism development and their daily life.

The insignificant moderating effect of length of residency indicates that the psychological bond effect on motivation to support sustainable tourism development is equally strong or weak regardless of how long the residents lived in the place. This is surprising as residents who stay long in a place that they love should want to see a more sustainable future of the tourism development at their place, because length of residency represents their time investment in the place. However, our findings imply that if residents support sustainable tourism development because of their psychological bond with the place, time investment would not be a concern and hence has a minimal role.

In line with our premise, place attachment is fostered by residents’ evaluation of the place in both physical and social contexts. Residents who appreciated the landscape and people at the place would result in a psychological bond with the place. The findings exhibit a cognitive-emotion pathway as place perception is a cognitive evaluation and place attachment is an emotional bond with the place. This result echoes the conclusion in many previous studies (Matarrita-Cascante et al., Citation2010; Rollero & De Piccoli, Citation2010; Stylidis, Citation2018). Moreover, the mediating effect of place attachment indicates that the cognitive evaluation of a place shapes attitude towards sustainable tourism development because of the emotional bond. Furthermore, our conjecture about the moderating role of length of residency on place perception—place attachment is confirmed. Long residency is helpful in increasing place attachment which is a finding coherent with previous studies (Bonaiuto et al., Citation1999; Hashemnezhad et al., Citation2012; McCool & Martin, Citation1994). The findings indicate that the psychological bond between the residents and their place depends on how long the residents stay at the place. Residents with long residency and have a positive (negative) evaluation of the place will form a stronger (weaker) bond with the place. The strong (weak) psychological bond will then be translated into a stronger (weaker) support for sustainable tourism development.

5. Conclusions and implications

5.1. Theoretical contributions

This study explores how place perception influences support for sustainable tourism development and if the influences are contingent on length of residency. The study adds knowledge to literature and contributes to theory in several aspects. First, while support for tourism development and its determinants have been widely studied in the past, less is known about support for sustainable tourism development albeit sustainable tourism is a globally recommended practice. Our research attempt in this study draws tourism impact researchers’ attention to the determinants of support sustainable tourism development. Second, in addition to revealing that place perception and place attachment are the determinants, this study provided deeper insights by discovering place attachment as the underlying reason for the influence of place perception on support for sustainable tourism development. The findings resemble a cognitive-emotion-behavior pathway. Other emotion-laden mediators can be examined in future studies. Third, while prior tourism impact research noted the importance of length of residency as a determining factor, this study empirically demonstrates its alternative role through exploring its moderating effect. Particularly, length of residency enhances the influence of place perception on place attachment, but not the influence of place attachment on support for sustainable tourism development. Future research about sustainable tourism development is recommended to consider the moderating role of length of residency. Besides, future studies can examine other related socio-demographic moderators such as whether the respondents are immigrants to gain a better understanding about the dynamics of psychological bond of immigrants (versus indigenous residents) with the place.

5.2. Practical implications

The findings in this study provide implications for destination governors to pursue sustainable tourism. Without the support and participation of residents in the project of pursuing sustainable tourism, a destination will lose its competitiveness in the long-run. Our findings show that place perception leads to residents’ support and participation. The destination governor (i.e. the Macao Government) is recommended to beautify the city landscape, to well-maintain the heritage and historical sites, and to create a friendly social atmosphere of the community. Relatively speaking, beautifying the city landscape is easier and takes shorter time than nurturing a friendly social atmosphere. In the pursuit of a friendly social atmosphere, the governor needs to strike a balance between tourism growth and residents’ quality of life, so that a constructive relationship between tourists and residents will be maintained. While Macao locals were well-recognized for their friendliness, this personal strength should be emphasized by the government in its education program targeting local youngsters. By pursuing these initiatives, residents’ psychological bond with the destination (i.e. place attachment) will be fostered and increased alongside with the years they have stayed in the city. Accordingly, a negative place perception will destroy place attachment and hence hinder sustainable tourism development.

On the other hand, the governor can identify the residents with high place perception and place attachment, and then assign them to be the promoters or ambassadors of sustainable tourism development. Through their active and promotion works, a positive momentum of sustainable tourism will be created in the community. Regarding the ideal promoters or ambassadors, according to our findings, they should be residents with positive evaluation of the place and long residency. After identifying the residents with long residency, the government needs to assess if they positively evaluate the place. Otherwise, the consequence will be disastrous.

5.3. Limitations and future research

The above implications should be considered with several limitations of this study. First, as limited by its scope, this study only examined place perception and place attachment as the determinants, the effects of other place-related constructs have not been controlled and have remained unknown. Future research is recommended to incorporate constructs such as place identity and place dependence. Second, the convenience and snowball sampling approaches as well as recruitment of respondents on Wechat limit the representativeness of our findings. Although our analyses have incorporated weighting based on gender and age distributions of Macao population, other socio-demographic variables such as education, marital status and others were not weighted owing to the lack of population statistics. Future research is recommended to adopt random sampling and phone survey. Third, data were collected during pandemic, the influence of pandemic on our findings which consist of emotional construct (i.e. place attachment) can be significant. A replication of this study is recommended at the post-pandemic period. Future research can also consider a longitudinal approach as place perception evolves over time (Woosnam, Citation2012). Fourth, the implications were drawn from Macao which has its unique characteristics. Generalization of the implications to destinations with different characteristics has to be cautious. The model is worthwhile for re-examination in other destinations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, L. R., Long, P. T., Perdue, R. R., & Kieselbach, S. (1988). The impact of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. Journal of Travel Research, 27(1), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758802700104

- Altman, I., & Wohlwill, J. F. (2012). Human behavior and environment: Advances in theory and research. Plenum Press.

- Bonaiuto, M., Aiello, A., Perugini, M., Bonnes, M., & Ercolani, A. P. (1999). Multidimensional perception of residential environment quality and neighbourhood attachment in the urban environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19(4), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1999.0138

- Bonaiuto, M., Breakwell, G. M., & Cano, I. (1996). Identity processes and environmental threat: The effects of nationalism and local identity upon perception of beach pollution. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 6(3), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1298(199608)6:3<157::AID-CASP367>3.0.CO;2-W

- Brown, G., & Raymond, C. (2007). The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Applied Geography, 27(2), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2006.11.002

- Brown, G., Raymond, C. M., & Corcoran, J. (2015). Mapping and measuring place attachment. Applied Geography, 57, 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.12.011

- Brown, R. B. (1993). Rural community satisfaction and attachment in mass consumer society. Rural Sociology, 58(3), 387–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.1993.tb00501.x

- Brügger, A., Kaiser, F. G., & Roczen, N. (2011). One for all? European Psychologist, 16(4), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000032

- Chen, N. C., & Dwyer, L. (2018). Residents’ place satisfaction and place attachment on destination brand-building behaviors: Conceptual and empirical differentiation. Journal of Travel Research, 57(8), 1026–1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517729760

- Cheng, T.-M., & Wu, H. C. (2015). How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(4), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.965177

- Choi, H.-S. C., & Sirakaya, E. (2005). Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism: Development of sustainable tourism attitude scale. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505274651

- Chow, K., & Healey, M. (2008). Place attachment and place identity: First-year undergraduates making the transition from home to university. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(4), 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.02.011

- Davenport, M. A., & Anderson, D. H. (2005). Getting from sense of place to place-based management: An interpretive investigation of place meanings and perceptions of landscape change. Society & Natural Resources, 18(7), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920590959613

- Dwyer, L., Chen, N. C., & Lee, J. J. (2019). The role of place attachment in tourism research. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(5), 645–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1612824

- Eslami, S., Khalifah, Z., Mardani, A., Streimikiene, D., & Han, H. (2019). Community attachment, tourism impacts, quality of life and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(9), 1061–1079. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1689224

- Fong, L. H. N., Fong, D. K. C., & Law, R. (2016). A formative approach to modeling residents’ perceived impacts of casino development. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(8), 1181–1194. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1094437

- Gursoy, D., & Rutherford, D. G. (2004). Host attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.008

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hall, C. M. (2007). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationship (2nd ed.). Pearson Education.

- Hashemnezhad, H., Heidari, A. A., & Hoseini, P. M. (2012). “Sense of place” and “place attachment”. International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development, 3(1), 5–12.

- Hidalgo, M. C., & Hernández, B. (2001). Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0221

- Hsu, C. H. C., Wolfe, K., & Kang, S. K. (2004). Image assessment for a destination with limited comparative advantages. Tourism Management, 25(1), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00062-1

- Isa, S. M., Ariyanto, H. H., & Kiumarsi, S. (2020). The effect of place attachment on visitors’ revisit intentions: Evidence from Batam. Tourism Geographies, 22(1), 51–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1618902

- Jorgensen, B. S., & Stedman, R. C. (2006). A comparative analysis of predictors of sense of place dimensions: Attachment to, dependence on, and identification with lakeshore properties. Journal of Environmental Management, 79(3), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.08.003

- Kang, S. K. (2019). Place attachment, image, and support for marijuana tourism in Colorado. SAGE Open, 9(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019852482

- Kasarda, J. D., & Janowitz, M. (1974). Community attachment in mass society. American Sociological Review, 39(3), 328–339. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094293

- Khoshkam, M., Marzuki, A., & Al-Mulali, U. (2016). Socio-demogrpahic effects on Anzali wetland tourism development. Tourism Management, 54, 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.10.012

- Knez, I. (2005). Attachment and identity as related to a place and its perceived climate. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.03.003

- Krishnaswamy, J., Abdullah, D., & Wen, T. C. (2018). An empirical study on residents’ place image and perceived impacts on support for tourism development in Penang, Malaysia. Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(16), 178–198. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i16/5127

- Lalli, M., & Thomas, C. (1989). Public opinion and decision making in the community: Evaluation of residents’ attitudes towards town planning measures. Urban Studies, 26(4), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420988920080461

- Leisen, B. (2001). Image segmentation: The case of a tourism destination. Journal of Services Marketing, 15(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040110381517

- Lestari, W. M., & Sumabrata, J. (2018). The influencing factors on place attachment in neighborhood of Kampung Melayu. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 126(1), 012190. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/126/1/012190

- Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

- Liang, H., Saraf, N., Hu, Q., & Xue, Y. (2007). Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Quarterly, 31(1), 59–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148781

- Macao Statistics and Census Service. (2020a). Gross domestic product 2019. https://www.dsec.gov.mo/getAttachment/d026d309-503b-4a90-9789-a06137006823/C_PIB_PUB_2019_Y.aspx

- Macao Statistics and Census Service. (2020b). Tourism statistics: 4th quarter 2019. https://www.dsec.gov.mo/getAttachment/00eee72e-8e7a-4a7a-baec-541d2b81a8c8/E_TUR_FR_2019_Q4.aspx

- Macao Statistics and Census Service. (2020c). Demographic statistics 2019. https://www.dsec.gov.mo/en-US/Statistic?id=101

- Matarrita-Cascante, D., Stedman, R., & Luloff, A. E. (2010). Permanent and seasonal residents’ community attachment in natural amenity-rich areas. Environment and Behavior, 42(2), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509332383

- McCool, S. F., & Martin, S. R. (1994). Community attachment and attitudes toward tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 32(3), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759403200305

- Mesch, G. S., & Manor, O. (1998). Social ties, environmental perception, and local attachment. Environment and Behavior, 30(4), 504–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659803000405

- Morales Lopez, R. E. (2012). Local residents’ place attachment, place social values and attitudes toward tourism development in northeastern Puerto Rico [Master’s thesis, State University of New York]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1037994740?accountid=12206

- Nicholas, L. N., Thapa, B., & Ko, Y. J. (2009). Residents’ perspectives of a world heritage site. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(3), 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.03.005

- Pham, H. L., & Kalsom, K. (2011). Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact and their support for tourism development: The case study of Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh province, Vietnam. European Journal of Tourism Research, 4(2), 123–146.

- Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2012). Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511410321

- Ramkissoon, H., Graham, S. L. D., & Weiler, B. (2013). Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tourism Management, 36, 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.003

- Ramkissoon, H., & Nunkoo, R. (2011). City image and perceived tourism impact: Evidence from Port Louis, Mauritius. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 12(2), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2011.564493

- Rollero, C., & De Piccoli, N. (2010). Place attachment, identification and environment perception: An empirical study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(2), 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.12.003

- Schroeder, T. (1996). The relationship of residents’ image of their state as a tourist destination and their support for tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 34(4), 71–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759603400411

- Sheldon, P. J., Var, T., & Var, T. (1984). Resident attitudes to tourism in North Wales. Tourism Management, 5(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(84)90006-2

- Shen, K., Geng, C., & Su, X. (2019). Antecedents of residents’ pro-tourism behavioral intention: Place image, place attachment, and attitude. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02349

- Shouran, F. G. J., Bande, S. A. S., & Gheibi, S. (2019). Investigating the factors affect individual’s attachment to place. International Academic Journal of Science and Engineering, 06(1), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.9756/IAJSE/V6I1/1910009

- Sinclair-Maragh, G. (2017). Demographic analysis of residents’ support for tourism development in Jamaica. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.03.005

- Soini, K., Vaarala, H., & Pouta, E. (2012). Residents’ sense of place and landscape perceptions at the rural–urban interface. Landscape and Urban Planning, 104(1), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.10.002

- Stedman, R. C. (2002). Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environment and Behavior, 34(5), 561–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502034005001

- Stedman, R. C. (2003). Is it really just a social construction? The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Society & Natural Resources, 16(8), 671–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920309189

- Stylidis, D. (2018). Place attachment, perception of place and residents’ support for tourism development. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(2), 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2017.1318775

- Stylidis, D. (2020). Using destination image and place attachment to explore support for tourism development: The case of tourism versus non-tourism employees in EILAT. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(6), 951–973. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020919157

- Stylidis, D., Biran, A., Sit, J., & Szivas, E. M. (2014). Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tourism Management, 45, 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.05.006

- Swarbrooke, J. (2010). Sustainable tourism management. Cabi Publishing.

- Tang, W. Y., Zhang, J., Luo, H., Lu, S., & Yang, X. Z. (2008). Relationship between the place attachment of ancient village residents and their attitude towards resource protection—A case study of Xidi, Hongcun and Nanping Villages. Tourism Tribune, 23(10), 87–92.

- Tartaglia, S. (2006). A preliminary study for a new model of sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20081

- Tasci, A. D. A., & Gartner, W. C. (2007). Destination image and its functional relationships. Journal of Travel Research, 45(4), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507299569

- Tournois, L., & Djeric, G. (2019). Evaluating urban residents’ attitudes towards tourism development in Belgrade (Serbia). Current Issues in Tourism, 22(14), 1670–1678. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1465030

- Tuan, Y. F. (2001). Space and place: The perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Um, S., & Crompton, J. L. (1987). Measuring resident’s attachment levels in a host community. Journal of Travel Research, 26(1), 27–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758702600105

- Vaske, J. J., & Kobrin, K. C. (2001). Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. The Journal of Environmental Education, 32(4), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960109598658

- Vidal, T., Valera, S., & Peró, M. (2010). Place attachment, place identity and residential mobility in undergraduate students. PsyEcology, 1(3), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1174/217119710792774799

- Vong, L. T.-N., Lai, K., & Li, Y. (2015). Influence of casino impact perception on sense of place: A study on casino-liberalized macao, China. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(8), 920–941. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2014.946938

- Vorkinn, M., & Riese, H. (2001). Environmental concern in a local context: The significance of place attachment. Environment and Behavior, 33(2), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121972972

- Walker, A. J., & Ryan, R. L. (2008). Place attachment and landscape preservation in rural New England: A Maine case study. Landscape and Urban Planning, 86(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.02.001

- Woosnam, K. M. (2012). Using emotional solidarity to explain residents’ attitudes about tourism and tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511410351

- Woosnam, K. M., Aleshinloye, K. D., Ribeiro, M. A., Stylidis, D., Jiang, J., & Erul, E. (2018). Social determinants of place attachment at a World heritage site. Tourism Management, 67, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.01.012

- World Tourism Organization. (2003). Agenda 21 for the travel & tourism industry: Towards environmentally sustainable development.

- Xu, Z., Zhang, J., Wall, G., Cao, J., & Zhang, H. (2009). Research on influence of residents’ place attachment on positive attitude to tourism with a mediator of development expectation: A case of core tourism community in Jiuzhaigou. Acta Geographica Sinica, 64(6), http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-DLXB200906012.htm.

- Zhu, H., Liu, J., Wei, Z., Li, W., & Wang, L. (2017). Residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in a historical-cultural village: Influence of perceived impacts, sense of place and tourism development potential. Sustainability, 9(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010061