ABSTRACT

Residents’ support for tourism is essential for the tourism governance. Currently, knowledge of factors influencing tourism support is inconclusive. Studies applying social exchange theory reveal that tourism support is a function of perceived tourism impacts. However, studies suggest that social exchange theory applications insufficiently explain determinants of tourism support. Using the Value-Attitude-Behavior approach, and quality of life concept, we examine factors likely to predict support for tourism. Our results suggest that residents’ perceived tourism impacts are strong determinants of their support for tourism. Additionally, our results suggest that quality of life does not mediate the influence of attitudes concerning tourism impacts on tourism support. Results also suggest that positive and negative tourism impact attitudes fully mediate the influence of commodity value orientations on tourism support. However, such attitudes were not found to mediate the influence of ecocentric value orientations on support for tourism. We discuss the implications of these findings.

Introduction

Understanding residents’ attitudes toward and support for local tourism is critical for effective tourism planning and management (Ribeiro et al., Citation2017; Sharpley, Citation2014). Previous research suggests that residents’ support for tourism is essential for local tourism industries’ success and sustainability in communities that experience tourism (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Sharpley, Citation2014). Evaluating residents’ attitudes toward public forest-based tourism, in particular, is especially important for planners and managers working in localities that are attempting to economically diversify following declines in commercial timber industries. This is the case in the State of Oregon U.S., where a thriving timber industry has historically been a significant part of the State’s economy (Kline & Armstrong, Citation2001). The timber industry and other forestry-related jobs have long provided jobs and income for Oregonians, particularly those in rural communities with limited transferable skills (Kelly & Bliss, Citation2009). Over the past 25 years, however, Oregon’s timber industry has declined, resulting in loss of jobs and other socioeconomic effects (Charnley et al., Citation2008). These declines have mostly impacted rural communities, where the loss of timber-related jobs has led to increased poverty and social fragmentation (Weber & Chen, Citation2012). To address the growing poverty concerns in rural communities, the State of Oregon began investing in forest-based tourism attractions (e.g. nature hiking and mountain biking) to sustain economic growth (Dean Runyon Associates, 2019). Indications are that tourism may offer at least some potential to generate economic benefits for rural communities (Pearce, Citation2007).

Although the potential for tourism to provide positive economic impacts to rural communities in Oregon appears promising (e.g. Dean Runyan Associates, Citation2019), the extent to which Oregon's tourism growth can be maintained depends in part on rallying support for tourism amongresidents in rural communities where forest-based tourism industries and businesses are emerging (Sharpley, Citation2014). Tourism industries often are vulnerable if residents perceive negative tourism impacts (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2011). Once maintained, however, the positive impacts of tourism are likely to generate and sustain residents’ support for tourism (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2011). This transactional relationship between resident attitudes toward and support for tourism can be explained in part by social exchange theory (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016), whereby residents who find that they benefit from local tourism will also tend to support it. However, there are limits to how well social exchange theory accounts for residents’ support for tourism (Li et al., Citation2020; Sharpley, Citation2014). For example, according to Sharpley (Citation2014), positive or negative attitudes toward tourism are likely also shaped by personal values as well as social context. For places such as Oregon, that have historically relied on an active timber industry for economic development, forest values in particular likely influence residents’ attitudes toward tourism.

In this study, we examine the potential influence of residents’ forest value orientations on their attitudes toward forest-based tourism growth in their communities. In particular, we evaluate the potential effect of “forest commodity” versus “ecocentric” forest value orientations using the values-attitudes hierarchy conceptual framework (Han et al., Citation2019), and how such values might enhance the social exchange theory explanations of residents attitudes. We build on existing tourism literature to integrate the quality of life concept into the social exchange theory-based transactional relationship between residents’ attitudes towards and support for tourism. For example, recent studies have introduced and called for understanding the links between quality of life and tourism support (Kim et al., Citation2013; Lai et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2020; Uysal et al., Citation2016; Woo et al., Citation2015). Our study relies on data from a survey of residents in Klamath and Linn counties in Oregon to test the hypothesized relationships.

Conceptual background and hypothesis development

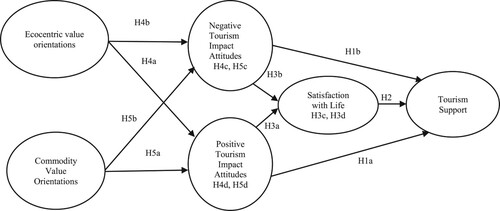

summarizes the key hypothesized relationships we examined. Social exchange theory (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016) hypothesizes that perceived positive and negative attitudes toward tourism are useful in predicting residents’ support for tourism (Hypothesis 1). Additionally, we also consider the role of quality of life in moderating the transactional relationship between residents’ attitudes toward, and support for, tourism (Hypotheses 2-3), as suggested by Nunkoo and So (Citation2016) and others (e.g. Lai et al., Citation2021). Hypotheses 4–5 represent the potential influence of public forest values on tourism attitudes, based on the Values-Attitudes-Behavior Hierarchy (Han et al., Citation2019). Hypotheses 4 and 5 are also explored in consideration of the criticism for the perceived limitations of Social Exchange Theory to fully explain support for tourism (Boley et al., Citation2014; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Woosnam, Citation2012). We elaborate on each of these in turn.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Value-Attitude-Behavior model predicting relationships between public forest values, tourism attitudes, quality of life, and tourism support.

A social exchange perspective of residents’ support for tourism

Social exchange theory (SET) historically has been used to conceptualize residents’ support for tourism in their communities (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Yeager et al., Citation2020). The SET explains transactional resource exchanges between people (Sharpley, Citation2014). According to SET, residents who are perceive or experience positive impacts from tourism are more likely to support tourism development and growth (Li et al., Citation2020; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Yeager et al., Citation2020). Positive tourism impacts, such as creating jobs and income opportunities, are more likely to positively influence the residents’ support for tourism. However, residents who experience or perceive adverse tourism impacts, such as increased crime, pollution, or higher costs of living, are less likely to support tourism development and growth (Li et al., Citation2020). Research suggests that limited support for tourism among residents is more likely to occur when perceived negative tourism impacts outweigh the tourism benefits (Li et al., Citation2020; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Woo et al., Citation2015). In tourism attitudes research literature, SET remains a dominant conceptual lens through which the residents’ support is assessed, despite criticism for its inability to fully explain tourism support (Boley et al., Citation2014; Gannon et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2020; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Yeager et al., Citation2020). We, therefore, hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a): Positive tourism impact attitudes are positively related to support for tourism.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b): Negative tourism impact attitudes are negatively related to support for tourism.

Contextual influence of quality of life

The quality of life concept is a recently emerging concept in the tourism research literature (e.g. Li et al., Citation2020; Uysal et al., Citation2016). Andereck and Nyaupane (Citation2011) define the quality of life as an individual's satisfaction with life and an overall feeling of fulfillment. In the human development literature, quality of life is synonymous with the concept of satisfaction with life (Diener, Citation2012). This is likely due to life satisfaction's potential to represent the global assessment of the quality of life (OECD, Citation2013). According to Diener (Citation2012), satisfaction with life represents the cognitive evaluation of one's quality of life. In this paper, we apply the concept of satisfaction with life as the residents’ global assessment of their own quality of life. Research has shown that individuals who perceive that their quality of life is positively impacted by tourism are more likely to support tourism, while those individuals who perceive adverse impacts are less likely to support tourism (Kim et al., Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2020; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Woo et al., Citation2015). Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Satisfaction with life is positively related to supports for tourism

Hypothesis 3a (H3a): Positive tourism impact attitudes are positively related to satisfaction with life

Hypothesis 3b (H3b): Negative tourism impact attitudes are negatively related to satisfaction with life

Hypothesis 3c (H3c): Satisfaction with life mediates the relationship between positive tourism impact attitudes and support for tourism

Hypothesis 3d (H3d): Satisfaction with life mediates the relationship between negative tourism impact attitudes and support for tourism

Forest value orientations predicting tourism attitudes

Scholars such as Sharpley (Citation2014) and others (Lai et al., Citation2021; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Woosnam, Citation2012) have argued that tourism attitudes are shaped by other context factors underlying the transactional relationship between tourism attitudes and support for tourism. However, these studies also have suggested that the antecedents of tourism attitudes are still not well understood, and there is a need to explore other underlying factors. When observed from a socio-psychological perspective, one such factor arguably is personal values (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2009; Sharpley, Citation2014), which potentially could predict tourism attitudes (e.g. Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2009).

The predicting role of personal values in determing tourism attitudes is supported by the Values-Attitudes-Behavior Hierarchy (Han et al., Citation2019). According to Values-Attitudes-Behavior Hierarchy (VABH), personal values are antecedents of attitudes perceived to influence behavior directly (Han et al., Citation2019). In other words, values are likely to directly affect tourism attitudes, thereby indirectly predicting support for tourism. Han and colleagues (Citation2019) indicate that personal values shape a person's life and that these influences are relatively stable over time. The hypothesized stability of personal values is supported by Vaske and Donnelly (Citation2015) who argue that “values transcend objects, situations, and issues.”

In forestry and natural resources studies, forest value orientations are often used to explain public attitudes toward forests (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation2018; Tarrant et al., Citation2003). Forest value orientations encompass commodity value orientations and ecocentric value orientations (Anderson et al., Citation2018). Together, these forest value orientations can help to explain the “relative importance of forest resources” to human life (Tarrant et al., Citation2003). For example, commodity value orientations are associated with economic values of forest goods and services (Schindler & Steel 1993). Alternatively, ecocentric value orientations often are related to environmental quality and ecological values of forests (Anderson et al., Citation2018). Based on the VABH approach, both the commodity and ecocentric value orientations arguably have the potential to directly influence tourism attitudes (Han et al., Citation2019). These relationships would seem to be particularly relevant in Oregon, where forests are historically tied to socioeconomic growth (Charnley et al., Citation2008). Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a): Ecocentric value orientations are positively related to positive tourism impact attitudes.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b): Ecocentric value orientations are negatively related to negative tourism impact attitudes.

Hypothesis 4c (H4c): Positive tourism impact attitudes mediates the relationship between ecocentric value orientations and support for tourism.

Hypothesis 4d (H4d): Negative tourism impact attitudes mediates the relationship between ecocentric value orientations and support for tourism.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a): Commodity value orientations are positively related to positive tourism impact attitudes.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b): Commodity value orientations are negatively related to negative tourism impact attitudes.

Hypothesis 5c (H5c): Positive tourism impact attitudes mediates the relationship between commodity value orientations and support for tourism.

Hypothesis 5d (H5d): Negative tourism impact attitudes mediates the relationship between commodity value orientations and support for tourism.

Methods

Study area

We examined tourism attitudes in Linn and Klamath Counties in Oregon, U.S. Linn County is located west of the Cascades, in the Willamette Valley, about 70 miles south of the City of Portland, and 60 miles east of the Pacific Ocean. It is surrounded by three rivers: Willamette, Santiam, and North Santiam. Linn County has 2,297 square miles of land, and about 68 percent (1570 square miles) is forest land (Palmer et al., Citation2018). It has a population of nearly 130,000 people (U.S. Census Bureau). Klamath County is located east of the Cascades in southcentral Oregon, bordering Northern California. It is one of Oregon's largest counties, comprising 6,135 square miles, and about 48 percent (2,947 square miles) is forest land (Palmer et al., Citation2018). It has a population of over 68,000 persons, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Social and economic growth of western and central Oregon counties, such as, Linn and Klamath, has historically relied in part on forests and related timber industries (; Kelly & Bliss, Citation2009).

Both Linn and Klamath Counties, like the Pacific Northwest region generally, have been impacted by federal policy changes regarding timber harvesting on federal lands. In particular, the 1994 listing of the Northern Spotted Owl as endangered has been estimated to have halted logging on 10 million hectares of forest land (Phalan et al., Citation2019). Timber harvests in Klamath country declined from over 400 million board-feet per year in the mid-1990s to about 200 million feet or less a year (Andrews & Kutara, Citation2005). In Linn County, timber harvests declined from over 600 million board-feet per year before the mid-1990s to less than 300 million board feet per year (Andrews & Kutara, Citation2005). The resulting timber industry job losses have been blamed for increased poverty and social fragmentation (Charnley et al., Citation2008; Weber & Chen, Citation2012). Widespread unemployment has seemingly exacerbated social problems, such as crime and drug dependence in rural areas, including Klamath and Linn Counties (Charnley et al., Citation2008).

The State of Oregon has begun to consider the potential role that nature-based tourism could play in helping to revitalize rural communities (Dean Runyan Associates, Citation2019). The Oregon Travel Commission has led efforts to reposition the State of Oregon as a competitive tourism destination—one it says can be expected to generate economic growth opportunities to replace those lost with declines in timber industries. Advocates argue that tourism offers rural communities opportunities to rejuvenate their rural economies by providing jobs and revenue for local businesses (Dean Runyan Associates, Citation2019). They point to data showing that Oregon employment in the timber industry has declined by 10 percent since 2007, while employment in tourism has increased by almost 20 percent (Dean Runyan Associates, Citation2019). During that same time, timber industry-derived revenue increased by 10 percent, while tourism revenue increased by over 50 percent (Dean Runyan Associates, Citation2019). Tourism revenue and jobs in Klamath county indeed have been growing annually at an average rate of 4.4 and 3.3 percent since 2007 (Dean Runyan Associates, Citation2019). In Linn county, tourism revenue and jobs have increased at an annual average of about 6.4 and 3.1 percent (Dean Runyan Associates, Citation2019). Such trends and the interest they garner in Oregon about the potential economic activity that could result from tourism motivate the need for bettering understanding the potential constraints on tourism growth, which can include the degree of support that affected residents’ might feel toward tourism.

Sample and data collection

The sample from this study included residents from Linn and Klamath counties of Oregon. Data were obtained in fall 2018 from questionnaires sent to participants by mail, using randomly selected addresses (Klamath County, n = 352, 13% response rate; Linn County, n = 430, 17% response rate). The total sample size was 721 respondents, excluding 61 incomplete cases. A random sample of addresses was obtained from a commercial vendor and included city-style addresses, rural route addresses, highway contracts, and P.O. Box addresses. Extensive coverage of diverse address categories was aimed to minimize potential coverage error in sampling residents of Linn and Klamath counties (Dillman et al., Citation2014). The sampling process excluded seasonal, educational, and vacant residential addresses. The mail survey approach followed guidelines suggested by Dillman et al. (Citation2014). For example, a pre-notice letter was mailed to the sampled addresses first. Two weeks later, a full survey packet was mailed. A postcard reminder and replacement survey were sequentially mailed.

Considering that over 80 percent of participants did not respond in both counties, we conducted a telephone-based nonresponse bias check with a random sample of 62 of these participants, asking 9-randomly selected questions from the survey. The findings from a nonresponse bias check did not show any substantive difference between the people who responded and those who did not, as all effect size statistics were small with an average of 0.09 (Cohen, Citation1988). The profile of respondents is shown in . The sample consisted of 351 males (48%) and 370 females (about 51%). Most of the repondents were white (643, or 88/5%), politically conservative (297, or 41.5%), with less than $75,000 annual income (449, or about 64%). also shows that most respondents were college educated (329, or about 45%).

Table 1. The respondent profile (n = 731).

Measures and data analysis

The measures we used to represent the constructs we hypothesized in our structural model were obtained from published scales that we modified slightly to fit our particular study context. Measures of residents’ support for tourism, perceived negative impacts of tourism and perceived positive impacts of tourism were all obtained from McGehee and Andereck (Citation2004). Measures for satisfaction with the quality of life were obtained from Diener et al. (Citation1985). Measures for commodity and ecocentric value orientations were obtained from Shindler et al. (Citation1993). Participants were asked to indicate the level of agreement with statements measuring constructs, presented in and , on a 5-point scale, where 1 represented strong disagreement, and 5 represented strong agreement. Additionally, the survey instrument included questions about socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, education, income, location of residence, and employment.

The demographic variables of gender, age, and income of residents were compared with U.S. Census data for 2013-2017. Results indicated that there was a less than 5 percent difference in our sample and the general population in terms of the percentage of males and females and the incomes of respondents in both counties. However, differences were found in age categories, which differed with census data by over five percent in more than half of each county's age categories. Therefore, a post-stratification weighting approach was used to align the data obtained from the survey respondents with the Census-reported characteristics of Linn and Klamath County residents. Data from both samples were pooled for reliability and hypothesis testing.

Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in EQS version 6.1 was conducted to validate measures selected (Byrne, Citation2013). The CFA focused on measurement model and assessing it for for reliability and validity of measures for latent constructs. The second step involved conducting structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the statistical significance of the hypothesized relationships. The measurement model, in the initial step, revealed a Mardia’s coeffiencent greater than 5, suggesting existence of non-normally distributed data, and the need for estimating CFA and SEM models based on robust statitics which adjusts for non-normal data (Byrne, 2008). Additionally, the common method bias (CMB), an issue in self-administered surveys, was examined using the chi-square difference tests approach (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016). A common factor CFA model was estimated, and compared with a six-factor measurement model to determine the significance of change in chi-square. A significant change in chi-square, and better fit in the six-factor model signifies absence of CMB in the data used in this study (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016).

Finally, the structure of the hypothesized model was examined by reviewing the model fit indices and path coeffiencents. Furthermore, the mediation effect of two variables (satisfaction with life and perceived tourism impacts) in the hypothesized model was also of interest. Two models (fully and partially mediated) were compared to evaluate change in chi-square, which reveals potential for full or partial mediation (Byrne, 2008). Furthermore, Sobel test (Sobel, Citation1982) was used to calculate the statistical significance of mediation effect attributed to salitsfaction with life and perceived tourism impacts in the model.

Results

Descriptive information

On average, survey respondents moderately support tourism (mean = 3.52, SD = .81) and moderately agree that tourism impacts their community positively (mean = 3.65, SD = .62). Respondents also somewhat disagree that tourism is negatively impactful to their community (mean = 2.77, SD = .67). Collectively, respondents were neutral about the commodity value of forests (mean = 3.04, SD = .07), while they showed relatively strong agreement with the ecosystem value of forests (mean = 4.37, SD = .73).

Measurement model

Confirmatory factor analysis showed that the conceptual model fits the sample data, according to (Byrne Citation2013), (S-Bχ2 = 1230.26, p < .001, CFI = .948, NNFI = 0.943, RAMSEA = .04 with a 90% CI of [.037 - .043], and SRMR = .042). The standardized factor loadings are greater than 0.6 and significant at p < .05, providing proof of measurement reliability according to Hair et al. (Citation2016). As indicated in , the standardized loadings for items measuring the perceived negative tourism impacts construct ranged between .69 and .87. Standardized loadings for items measuring perceived positive tourism impacts construct ranged between .75 and .83, while loadings for items measuring tourism support construct ranged from .75 to .87. Standardized loadings for items measuring ecosystem forest value orientation ranged between .69 and .86, while the standardized loadings for items measuring the commodity forest value orientation ranged from .70 to .86. Finally, the standardized loadings for items measuring satisfaction with life overall ranged between .62 and .88. These results, as shown in , indicate evidence of the reliability of measures utilized in this study, according to Hair et al. (Citation2016).

Table 2. Reliability of measures and constructs in measurement model.

Additionally, shows maximal weighted values above 0.6, and the average extracted variance values of over 0.5, which, according to Hair et al. (Citation2016), indicate evidence of composite reliability and convergent validity of measures respectively. As shown in , none of the correlations between the independent latent constructs exceeded the associated square root of the average variance extracted values, confirming discriminant validity of measures utilized (Hair et al., Citation2016).

Table 3. Evidence of discriminant validity among the independent variables.

Finally, the measurement model was tested for the common method bias and measurement invariance. Examining presence of common method bias (CMB) is advisable for self-administered surveys (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003). The Chi-square difference test results show that the proposed six-factor measurement model fits the data significantly better than the a common factor model (Δ S-Bχ2 = 1950.9, Δ df = 16, p < .001), which suggests that the CMB is not a of concern in this study.

Structural model

Relationship between tourism impact perceptions, quality of life, and support for tourism

The hypothesized model predicting factors that influence residents’ support for tourism account for about 78% of the variance in tourism support construct. , provided below, summarizes the hypothesis testing results. As anticipated in Hypothesis 1a, positive tourism perceptions are significantly and positively related to tourism support (β = .78, p < .001). Similarly, as expected in Hypothesis 1b, negative tourism perceptions are significantly and negatively related to tourism support (β = -.17, p < .001). However, Hypothesis 2 predicting that satisfaction with life is significantly and positively related to support for tourism was not supported as shown (β = -.01, p > .05). Furthermore, Hypothesis 3a predicting that positive tourism impact perceptions are significantly and positively related to satisfaction with life was supported (β = .16, p < .01). Hypothesis 3b, in contrast, predicting a significant negative relationship between negative tourism impact perceptions and satisfaction with life was not supported (β = -.02, p > .05). Finally, at shown in , hypotheses 3c and 3d suggesting a mediating effect of satisfaction with life in the relationship between perceived tourism impact (positive and negative) and support for tourism were not supported.

Table 4. Structural models exploring factors predicting support for tourism.

Table 5. Mediation effect results.

The potential role of public forest value orientation

The public forest value orientation explained about 2% of the variance in negative tourism attitude and about 8% of the variance in positive tourism attitudes. Hypothesis 4a and 4b predicted that ecocentric value orientation is significantly related to positive and negative tourism impact attitudes, respectively. As anticipated, results support Hypothesis 4a indicating ecocentric value orientations are significantly and positively related to positive tourism impact attitudes (β = .34, p < .001). In contrast, however, ecocentric value orientations were not found to be significantly related to negative tourism impact attitudes (i.e. H4b) (β = -.07, p > .05). Hypotheses 4c and 4d in show that ecocentric value orientations potentially do not influence support for tourism through both negative and positive tourism attitudes. Additionally, both Hypothesis 5a and 5b predicted that commodity value orientations are significantly related to positive and negative tourism impact attitudes. Results show that Hypothesis 5a (β = .12, p > .05) and Hypothesis 5b (β = .1, p > .05) were not supported. However, as shown in , Hypotheses H5c and H5d were supported, suggesting that perceived positive and negative impacts of tourism fully mediates the relationship between commodity value orientation and support for tourism. Therefore, for residents who are more inclined to appreciate forests for community values, their support for tourism support is likely associated with how tourism is perceived to cost or benefit them.

Discussion and conclusions

This study builds upon previous studies (e.g. Boley et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2020; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016) by providing evidence to support social exchange theory-informed transactional relationship between residents’ attitudes toward and support for tourism. We found that both positive and negative attitudes toward tourism are strongly correlated with tourism support and account for about 78% of the variance in support. In contrast, to SET criticism (e.g. Nunkoo & So, Citation2016), our findings provide evidence of the potential for SET to explain support for tourism with confidence as previously indicated (Boley et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2020). Similar to previous findings (e.g. Boley et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2020; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016), we also found positive tourism attitudes to be a stronger predictor of tourism support. An implication of this finding, it would seem, is that tourism destinations might be able to strengthen tourism support by educating and raising awareness of residents about the positive impacts of tourism. This would be particularly important in areas where forest values are oriented toward commodity values. Considering the finding of a strong mediating role of tourism impact attitudes in the relationship between commodity value orientations and support for tourism, tourism development and outreach efforts in commodity oriented communities would need to specifically address residents’ attitudes toward tourism impacts. For example, tourism campaigns could be supplemented with investment of human and financial resources to moderate or mitigate potential negative impacts of tourism.

Few studies have integrated quality of life in tourism attitudes studies (Lai et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2020; Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Woo et al., Citation2015). Following the aforementioned studies, we examined the effect of tourism attitudes on quality of life, and how quality of life effects tourism support. Our findings mirror those of the best performing model in Nunkoo and So (Citation2016) and also Li et al. (Citation2020), indicating that residents’ assessments of their own quality of life is strongly and positively predicted by positive tourism impact attitudes. However, our findings also show that quality of life perceptions do not have a strong impact on tourism support. Lastly, this study suggests that ecocentric value orientations are strongly correlated with positive tourism attitudes. This result aligns with previous findings indicating that value orientations predict individuals’ tourism attitudes (Han et al., Citation2019; Vinzenz et al., Citation2019). For example, Vinzenz et al. (Citation2019) found that ecosystem value orientations predicted attitudes regarding the sustainability performance of hotels when it enhanced socio-environmental wellbeing. Results from our study suggest that residents who have ecosystem-oriented views toward public forests often also have positive tourism attitudes, and are thus more likely to be supportive of tourism. Tourism developers aiming to increase community support for tourism by communicating its positive influence might find that their most receptive audience for communication and outreach campaigns may be among residents holding ecosystem value-oreinted views toward public forests.

In contrast, commodity value orientations were not found to be strongly correlated with positive tourism attitudes. Similarly, both ecosystem and commodity forest value orientations were not found to be strongly related to negative tourism impact attitudes. These findings suggest that commodity-oriented residents are not likely to be concerned about positive or negative tourism development implications, and therefore are less likely to support tourism. However, we did find that attitudes toward tourism impacts fully mediate the relationship between commodity value orientations and support for tourism. This could mean that commodity value oriented residents are likely concerned that tourism may reduce existing opportunities for maintaining extractive forest industries. It is likely that commodity value oriented residents may support tourism if it provides tangible benefits, similar to traditional benefits they derived from public forests when the extractive forest economy was successful. Thus, efforts to strengthen tourism support could aim to raise awareness about the ongoing or planned activities to improve the positive aspects of tourism development. Such efforts are best served by indicating ways in which tourism development could potentially complement existing extractive forest industries as part of a diversified approach to maintaining or promoting economic growth in rural communities that have typically depended on estractive forest industries alone.

Limitations and future research direction

Our conclusions from this study need to be interpreted with caution and so we offer several caveats. First, a random sample of respondents in this study is from rural counties, and may not represent the views of urban residents. Future research could address this limitation by clustering random selection of respondents to represent both rural and urban residents. Second, our study did not control for factors that have potential to influence residents’ attitudes and support for tourism. According to the literature (e.g. Sharpley, Citation2014) tourism attitudes are typically influenced by multiple extrinsic factors (e.g. level of tourism growth) and intrinsic factors (e.g. economic dependence on tourim). Future research could address this limitation by controlling for extrinsic and intrinsic factors commonly found to influence tourism attitudes.

Third, forest-based value orientations accounted for only a small portion of the variance in attitudes toward tourism impacts (2% in negative tourism attitudes and 8% in positive tourism impact attitudes). It is likely that forest-based values play only a small role in shaping residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts. Ideally, future research might integrate additional variables in models describing such perceptions. For example, research literature suggests that tourism impacts are likely shaped by personal values, experiences and social context (Sharpley, Citation2014). Future reseach conceptualizing factors predicting tourism impact perceptions could strive to integrate forest-based value orientations, lived experience, and social context as independent variables.

Forth, the utility of the proposed research model in advancing knowledge beyond the research site is unknown. Future research could advance knowledge by testing the utility of the model different geographical regions. Finally, this study showed that negative tourism impact perceptions fully mediates the influence of commodity value orientations on support for tourism but not the influence of ecocentric value orientation. It appears that ecocentric value orientations have potential to directly influence support for tourism, but commodity value orientations only do so through perceived tourism impacts. This finding is new and likely to have theoretical and practical implications. However, the ability of these findings to hold beyond the context of this study is unknown. Future research could continue to test the influence of commodity and ecocentric value orientations on tourism support, as conceptualized in this paper, in other research settings to confirm the aforementioned role of forest-based values on residents’ support for tourism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andereck, K., & Nyaupane, G. (2011). Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50(3), 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

- Anderson, N., Ford, R. M., Bennett, L. T., Nitschke, C., & Williams, K. J. (2018). Core values underpin the attributes of forests that matter to people. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research, 91(5), 629–640. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpy022

- Andrews, A., & Kutara, K. (2005). Oregon’s timber harvests: 1849-2004. Selected counties. Oregon Department of Forestry.

- Boley, B. B., McGehee, N. G., Perdue, R. R., & Long, P. (2014). Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a weberian lens. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.005

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming, Second edition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Charnley, S., Donoghue, E. M., & Moseley, C. (2008). Forest Management policy and community well-being in the Pacific northwest. Journal of Forestry, 106, 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/106.8.440

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Dean Runyan Associates. (2019). Oregon Travel impacts:Statewide estimates:1992-2018. Oregon Travel Oregon.

- Diener, E. (2012). New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. American Psychologist, 67(8), 590. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029541

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Dillman, D., Smyth, J., & Christian, L. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. Wiley.

- Gannon, M., Rasoolimanesh, S. M., & Taheri, B. (2021). Assessing the mediating role of residents’ perceptions toward tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 60(1), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519890926

- Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

- Han, H., Hwang, J., Lee, M. J., & Kim, J. (2019). Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior. Tourism Management, 70, 430–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.006

- Kelly, E. C., & Bliss, J. C. (2009). Healthy forests, healthy communities: An emerging paradigm for natural resource-dependent communities. Society and Natural Resources, 22(6), 519–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920802074363

- Kim, K., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2013). How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tourism Management, 36, 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.005

- Kline, J. D., & Armstrong, C. (2001). Autopsy of a forestry ballot initiative: Characterizing voter support for Oregon’s measure 64. Journal of Forestry, 99(5), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/99.5.20

- Lai, H. K., Pinto, P., & Pintassilgo, P. (2021). Quality of life and emotional solidarity in residents’ attitudes toward tourists: The case of Macau. Journal of Travel Research, 60(5), 1123–1139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520918016

- Li, X., Wan, Y. K. P., & Uysal, M. (2020). Is QOL a better predictor of support for festival development? A social-cultural perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(8), 990–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1577807

- McGehee, N. G., & Andereck, K. L. (2004). Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268234

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2009). Applying the means-end chain theory and the laddering technique to the study of host attitudes to tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802159735

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011). Developing a community support model for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 964–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.01.017

- Nunkoo, R., & So, K. K. F. (2016). Residents’ support for tourism: Testing Alternative structural models. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 847–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515592972

- OECD. (2013). OECD guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. OECD Publishing.

- Palmer, M., Kuegler, O., & Christensen, G. (2018). Oregon’s forest resources, 2006–2015: Ten-year forest inventory and analysis report. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-971 (pp. 54). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

- Pearce, P. L. (2007). Persisting with authenticity: Gleaning contemporary insights for future tourism studies. Tourism Recreation Research, 32(2), 86–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2007.11081281

- Phalan, B. T., Northrup, J. M., Yang, Z., Deal, R. L., Rousseau, J. S., Spies, T. A., & Betts, M. G. (2019). Impacts of the Northwest forest plan on forest composition and bird populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(8), 3322–3327. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813072116

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 879.

- Ribeiro, M. A., Pinto, P., Silva, J. A., & Woosnam, K. M. (2017). Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries. Tourism Management, 61, 523–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.004

- Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

- Shindler, B., List, P., & Steel, B. S. (1993). Managing federal forests: Public attitudes in Oregon and nationwide. Journal of Forestry, 91(7), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/91.7.36

- Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/270723

- Tarrant, M. A., Cordell, H. K., & Green, G. T. (2003). PVF: A scale to measure public values of forests. Journal of Forestry, 101(6), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/101.6.24

- Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., & Kim, H. (. (2016). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

- Vaske, J., & Donnelly, M. (2015). Perceived conflict with off leash dogs at Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks (HDNRU Report No. 76). Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks and Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA.

- Vinzenz, F., Priskin, J., Wirth, W., Ponnapureddy, S., & Ohnmacht, T. (2019). Marketing sustainable tourism: The role of value orientation, well-being and credibility. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(11), 1663–1685. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1650750

- Weber, B. A., & Chen, Y. (2012). Federal forest policy and community prosperity in the Pacific northwest. Choices (new York, N Y ), 27, (316-2016–6526). https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.122803

- Woo, E., Kim, H., & Uysal, M. (2015). Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 50, 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.11.001

- Woosnam, K. M. (2012). Using emotional solidarity to explain residents’ attitudes about tourism and tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511410351

- Woosnam, K. M., & Norman, W. C. (2010). Measuring residents’ emotional solidarity with tourists: Scale development of durkheim’s theoretical constructs. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509346858

- Yeager, E. P., Boley, B. B., Woosnam, K. M., & Green, G. T. (2020). Modeling residents’ attitudes toward short-term vacation rentals. Journal of Travel Research, 59(6), 955–974. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519870255