ABSTRACT

This study explores how tourism entrepreneurs change their business models during a crisis. By adopting dynamic capabilities as integral to business model change, this qualitative study explores how entrepreneurs change business models to meet a crisis, and proposes a taxonomy of important entrepreneurial practices underlying dynamic capabilities. This study empirically examines seven small companies operating in the nature-based tourism industry in Norway. Focusing on dynamic capabilities, whether innovative or adaptive, the findings suggest 12 dynamic capability-based entrepreneurial practices that are categorized as resource-, market, and technology-related practices. This study contributes to the literature by integrating business model innovation and dynamic capabilities in tourism crisis management.

Introduction

Major crises require considerable changes to tourism businesses, and the adoption of the dynamic capabilities (DCs) to business model innovation (BMI) can help investigate how such changes might occur. DCs are those capabilities that enable strategic changes through the reconfiguration of competencies and resources by orchestrating the firm’s resource base to match assessments of newly emergent opportunities or threats (Battisti & Deakins, Citation2017; Leih et al., Citation2015; Schilke et al., Citation2018; Teece et al., Citation1997). Within the tourism crisis management literature (Hall et al., Citation2017; Sigala, Citation2020), recently few studies have highlighted the crucial relevance of DCs for enhancing resilience through adaptations aimed at ensuring short-term survival and sustainable competitive advantage (Jiang et al., Citation2019, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Mansour et al., Citation2019). In the broader literature, DCs have been discussed with the concept of business models (BMs), i.e. the underlying logic of a business. Some scholars have argued that the development of DCs can lead to BMI (Inigo et al., Citation2017; Leih et al., Citation2015; Mezger, Citation2014; Schilke et al., Citation2018) i.e. “designed, nontrivial changes to the key elements of a firm’s BM and/or the architecture linking these elements” (Foss & Saebi, Citation2017, p. 207). However, the DCs approach still lacks a proper understanding of what constitutes a DC (Kump et al., Citation2019; Schilke et al., Citation2018).

This study elaborates on how entrepreneurs change their BMs by proposing a framework that focuses on DCs and their underlying practices relevant to BMI in times of crisis. In the management literature, several scholars have argued that the DCs approach can contribute to a richer understanding of BMIs that are implemented through particular practices, processes, and routines that are established by the firm’s DCs (Inigo et al., Citation2017; Mezger, Citation2014; Saebi, Citation2015; Teece, Citation2018). Taking such a position as its point of departure, this study reflects on the possibility of relating the dynamic element of DCs to the innovative element of BMs in the tourism industry. An exploration of crisis management through a temporal investigation of DCs (Schilke et al., Citation2018) can add an important dynamic dimension to the conceptualization of BMs. Combining the DCs with the BMI has the potential to emphasize the changes at the level of the various BM components without overlooking the BM overall logic.

This study focuses on tourism entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 crisis, and asks: how do entrepreneurs change the BMs via DCs in order to tackle the crisis? To provide a deep understanding of what type of BM changes are considered by the entrepreneurs, and how such changes are implemented, this study conducts a qualitative research of seven nature tourism companies in Arctic Norway. This article begins by discussing previous studies concerning DCs and BMI particularly in times of crisis. Then, two sections are dedicated respectively to the methods and the findings, which rely mainly on data collected via 14 semi-structured interviews with seven entrepreneurs at two points of time during the crisis. The findings are then discussed to elaborate on the taxonomy of DC-based entrepreneurial practices to change tourism BMs. This article concludes by highlighting this study’s theoretical contributions and its limitations and by providing suggestions for future studies.

Theoretical background

The DCs approach and BMI

The DCs approach is relevant to the capacity to undergo changes, address threats and exploit opportunities via BM changes. A DC is “the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environment” (Teece et al., Citation1997, p. 516) and “determine the firm’s agility and flexibility in implementing the new organizational design, including the alignment of new and existing activities and responses to the unforeseen internal and external contingencies that unavoidably accompany deploying a new BM” (Leih et al., Citation2015, p. 30). The changes can occur in any of the key components of a BM: products and services, activities, resources, partners, customer relationships, segments, channels and cost and revenue structure (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Citation2010; Teece, Citation2010).

Across the literature, DCs are discussed concerning their underlying microfoundations including processes and procedures (Teece, Citation2007), managerial and organizational processes and routines (Kump et al., Citation2019; Mezger, Citation2014; Saebi, Citation2015), entrepreneurial and business activities and processes (Inigo et al., Citation2017; Jiang et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Leih et al., Citation2015; Mansour et al., Citation2019). Regarding how such changes occur, Teece (Citation2007) proposed an entrepreneurial management framework that focuses on the capabilities of sensing, seizing, and transforming. Sensing and detecting opportunities and threats, and then seizing emergent opportunities can lead to changes in BMs (Teece, Citation2007). The DCs are related to the entrepreneur’s perception of opportunities to change former routines and resource bases and their willingness and ability to implement changes (McDermott et al., Citation2018; Zahra et al., Citation2006). This corresponds well with an opportunity-based view of entrepreneurship, where entrepreneurship is seen as the process of discovering, evaluating and exploiting opportunities (Brück et al., Citation2011; Leih et al., Citation2015; Ratten, Citation2020; Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). Tourism entrepreneurs are the individuals who discover, evaluate and exploit opportunities within the tourism industry, and give rise to innovations in times of crisis (Dahles & Susilowati, Citation2015).

DCs as core capabilities underlying changes in BMs are classified by Saebi (Citation2015) in three groups that reflect three typologies for BM changes: evolution, adaptation, and innovation. Evolutionary DCs concentrate on incremental adjustments to maintain the existing BMs, whereas adaptive DCs rely on periodic realignments to match the environment. In their most radical form, innovative DCs bring BMIs into existence to address a turbulent environment through innovative value creation, delivery and capturing (Saebi, Citation2015). Other typologies in the literature are akin to the conceptualization of DCs given by Teece (Citation2007) and include sensing abilities to understand the business environment in terms of technology and BMs (Mezger, Citation2014), competitors, market best practices, and its shifts (Kump et al., Citation2019), seizing abilities to integrate new market-, technology-, and BM-related knowledge, and translating abilities to implement such knowledge in product and process innovations (Kump et al., Citation2019; Mezger, Citation2014). Transforming abilities rely on conducting the changes to adapt value chain activities and decide on core resources and competency sourcing (Kump et al., Citation2019; Mezger, Citation2014).

Another classification of DCs refers to their contribution to BMI in terms of sustainability, which is related to the concept of resilience, which relies on the organizational capacity to prepare for a crisis (Ritter & Pedersen, Citation2020), and in BMs, pertains to the task of finding new methods of value creation to ensure and facilitate a sustainable transition towards post-crisis BMs (Schaltegger, Citation2020). Inigo et al. (Citation2017) investigated various DCs aimed at either evolutionary or radical BMI for sustainability, and they highlighted both the sensing abilities to pursue an active dialogue with relevant stakeholders and to proactively search for the trends beyond the industry and the seizing abilities to make improvements in value propositions (evolutionary BMs) and to create new value propositions (radical BMs) (Inigo et al., Citation2017). This classification suggests that the changes in BMIs for sustainability evolve and, thus, the classification stands in accord with a dynamic approach towards resilience as a learning process that refers to relevant DCs in the context of crisis management (Hall et al., Citation2017), which will be discussed following this chapter.

BMs and DCs in crisis management

Recently, Ritter and Pedersen (Citation2020) proposed a typology for BMs in the face of a crisis: resilient BMs, which successfully manage to build DCs and cope with a crisis, and vulnerable BMs, which are not able to adapt by themselves and thus, depend on external interventions. Indeed, resilient BMs emerge through quickly tailoring new products to new market demands (Manolova et al., Citation2020). Similarly, as Brück et al. (Citation2011) suggest, entrepreneurial activities are encouraged by crises. Tourism studies have attempted to address responses to crises (e.g. Dahles & Susilowati, Citation2015; McKercher & Chon, Citation2004) and building resilience (Biggs et al., Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2017); however, how such crises could stimulate innovative transformations has not yet been thoroughly discussed (Sigala, Citation2020). Notably, few studies examined tourism firms’ responses to crises and discussed BMI and DCs; thus, such empirical studies are relatively scant in the tourism crisis literature compared to business research (Breier et al., Citation2021; Jiang et al., Citation2019, Citation2021b).

Drawing on small tourism businesses’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis across eight different countries, Duarte Alonso et al. (Citation2020) suggest several ways in enhancing resilience through coping (reactive) strategies as well as adjusting and changing (proactive) day-to-day activities through which entrepreneurs seek new opportunities to innovatively change their offers. Given hospitality companies in Austria, Breier et al. (Citation2021) claim that BMIs during the pandemic were more focused on incremental changes to generate revenues than on producing a sustainable competitive advantage. They also recognize three drivers for BMI: free capacities, environmental threats and guests (Breier et al., Citation2021). However, the critical role of DCs in shaping BMs has not been discussed by these two studies (Leih et al., Citation2015; Schilke et al., Citation2018), considering that under such tremendous uncertainty, tourism businesses may need to abandon some of their previous practices due to a lack of access to key resources, and hence to reconfigure their resources and practices (Jiang et al., Citation2021a). Within another multi-industry study of the family firms in European countries, Kraus et al. (Citation2020) found that, across different industries, tourism companies particularly strive to develop new BMs not only to generate revenue but also to diversify the BMs. Given the timing of the study at the peak of the pandemic, this research employed BMs in a more general way to explain the temporary adaptations limitedly and suggested that further research is needed to elaborate on BM changes.

The DCs approach was adopted in tourism studies mostly to address a competitive environment (Leonidou et al., Citation2015; Thomas & Wood, Citation2014) rather than a turbulent environment, such as that experienced during the COVID-19 crisis (Jiang et al., Citation2021a). Although DCs are claimed to be critical in the face of crisis to build resilience (Jiang et al., Citation2019), this research stream is scarce in terms of the development of new DCs for crisis management (Jiang et al., Citation2021b). The exceptions are few; through focusing on tourism firms’ survival under the Libyan civil war, Mansour et al. (Citation2019) identified the two crisis management capabilities of crisis assessment (cognition) and crisis response (behavior). Still, considering that the authors recognized merely two general capabilities to elaborate on reactive and defensive strategies for coping, a deep understanding of DCs for innovation is missing. Another example is the study of a natural disaster in Australia by Jiang et al. (Citation2021b), who explored how tourism companies handle the disaster and suggested a resource-based DCs typology to address three aspects: “disaster life cycle”, “sources of resources”, and “deployment of resources”. The authors do not discuss how DCs lead to new BMs, and instead leave that question to be explored by future studies and acknowledge that natural disasters and pandemic crises are different considering the DCs particularly developed during the pandemic (Jiang et al., Citation2021b).

Based on Leih et al. (Citation2015), the current study views DCs as integral to BM change through entrepreneurial practices and skills by which the opportunities and the need to change BMs are recognized and the required resources and competences are orchestrated. This research regards a DC as a general construct without dividing it into its elements i.e. sensing, seizing, and transforming (Jiang et al., Citation2019; Mansour et al., Citation2019). To operationalize the DCs approach in a crisis context, this study’s theoretical framework was inspired by Pedersen and Ritter (Citation2020) who proposed a crisis phase model, the 5Ps model, which stands for position, plan, perspective, project, and preparedness. More specifically, DCs and related entrepreneurial practices can be identified through 3Ps (plan, project, and preparedness) by exploring new projects, products, key resources, routines and preparedness to implement new plans as well as the entrepreneurs’ perception of newly emerging opportunities and threats. This study notes that although DCs and BMIs are viewed as critical for tourism crisis management, such a research stream is still lacking (Breier et al., Citation2021; Jiang et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b), therefore, the overall purpose of this study is to contribute to the tourism crisis management literature concerning DCs and BMIs.

Methods

This study follows a multiple case-based grounded theory (GT) approach to answer the question of how entrepreneurs change their BMs via DCs to tackle the crisis. This research approach has been applied to build theories based on case studies by constantly making comparisons between theory and data (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). The GT approach and case study have several elements in common, such as theoretical sampling, case selection, and the use of various sources of data. Drawing on constructivism GT, this study’s approach relies on iterative processes of abductively going back and forth between data and theory (Charmaz, Citation2014; Matteucci & Gnoth, Citation2017). More importantly, this approach is opportune when little has been known about a subject (Birks & Mills, Citation2011) and leads this research due to several reasons: the complexity of the investigated phenomenon resulting from a major global crisis, the focus of the study on “how” change processes occur (Charmaz, Citation2014; Yin, Citation2014), and the infancy of the literature streams concerning BM, BMI and DCs in tourism research and particularly tourism crisis management (Breier et al., Citation2021; Jiang et al., Citation2021a).

A multiple case study design is preferred over a single-case study design because this study strives to obtain rich data by conducting a comparative analysis (Yin, Citation2014) among entrepreneurs who were actively adjusting their BMs by exploring new possibilities during the crisis. Yin (Citation2014) claims that the findings from case studies cannot be generalized to larger populations, because case selection informs the contribution of cases to build theories. A purposeful theoretical sampling approach was followed (Eisenhardt, Citation1989) to include the cases that are regarded to have a high potential to answer the research question and build theory (Yin, Citation2014). Given the number of cases, a minimum number of five cases (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaäna, Citation2014 ; Yin, Citation2014) or a range between four to ten cases is suggested (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). The selection relied on the first author’s pre-fieldwork of participating in a tourism local workshop just before the crisis hit, meeting with two researchers who had worked in this context previously, and meeting with Tromsø municipality about projects related to reviving the destination. The selection also referred to the authors’ familiarity with the context and the most recent relevant news from the local press, the web pages and social media of the regional destination management organizations, and the Norwegian Hospitality Association (NHO).

To gain information about the potential cases, the content of their web pages and blogs were also explored. Seven cases were selected by reference to entrepreneurs who own companies operating in nature tourism in northern Norway to attain a deep understanding of the main differences and similarities among them in terms of how they address the crisis (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Van Burg et al., Citation2020; Yin, Citation2014). The context of nature tourism was considered relevant due to the importance of this form of tourism in the region (Lee et al., Citation2017), which is highly vulnerable to global crises as a result of its dependence on international tourists (Seeler et al., Citation2021). These cases had other common elements: being active during summer 2020 (products and/or COVID measurements and/or new cancellation policies), surviving at least the first year of the crisis, and hence being in the process of building resilience, dynamically applying changes to their BMs, and agreeing to contribute to this research.

Along with Eriksson (Citation2014), who emphasized the importance of time span in DC studies to address change as a cornerstone, this study reflects on the potential of a longitudinal qualitative approach. This approach has the potential to capture the dynamic and learning aspects inherent to the DCs on which resilient BMs can be built. Hence, this empirical study was conducted during the pandemic over 10 months (July 2020–April 2021). As the main source of primary data, 14 semi-structured interviews were conducted with the entrepreneurs (informants) as the key persons in charge of designing and adapting new BMs, which took place over two rounds. Secondary data were also collected by reviewing the contents of cases’ webpages, reports, social media (the most recent posts), personal blogs, and press to enable evidence convergence when performing an analysis of the primary data (Yin, Citation2014). The interviews were conducted following a guide representing the relevant aspects of the literature. In particular, the three phases of plan, project and preparedness (Pedersen & Ritter, Citation2020) were used to structure the interviews. Questions concerning changes in the components of the companies’ BMs (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Citation2010; Teece, Citation2010) before and during the crisis were asked. The first round took place immediately after the first reopening of the borders following the COVID-19 travel restrictions in Norway in July, August and September 2020. Given that travel restrictions have been continued, the second round was conducted during February, March and April 2021 based on insight from the first interview round together with the companies’ most recent social media posts concerning new products, plans and strategies. The interviews from the first round lasted between 1 and 1.5 h, while the second-round interviews each lasted an average of 30 min. All interviews were conducted online via Zoom and then transcribed. shows a summary of case characteristics.

Table 1. Case description summary.

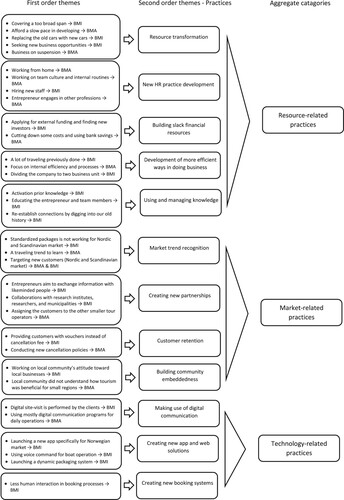

The data analysis consisted of a thematic analysis, and NVivo 12 was applied for coding both primary and secondary data as the aim was to recognize systematically relevant themes in data to set the stage for further data analysis, answer the research question and generate theory (Charmaz, Citation2014; Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, Citation2019). GT coding and memo-writing were followed as suggested by Charmaz (Citation2014). Beginning with the within-case analysis, the first coding cycle was carried out through open coding to provide interpretive labels (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). The initial labels (open codes) were mostly based on their relevance to the research question, prior literature and the interview guide or they may simply have emerged from the data during case analysis (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). For instance, given the literature and Teece’s (Citation2007) framework, the perception of opportunity and threats as well as changes to BM components provided useful insights into the coding procedure. Next, to search for patterns and themes and decide on which initial codes can answer the research question, focused coding was performed as the second coding cycle to make cross-case comparisons underlying the main themes, patterns, and categories. For this purpose, several memos were also developed at two coding stages concerning the relationships among the codes both within and across cases, for instance, the memos concerning the first impression of focused codes and comparing actual changes to promised changes. As such, the initial open codes were merged, revised, deducted, and categorized based on their relevance, for example, a variety of codes related to new products or any change in products were merged and categorized using the two main codes of BMIs or BM adjustment (BMAs). For better illustration see , which shows the structure of data in terms of first and second-order themes identified across the data analysis (coding) in addition to three main aggregate categories, resource-, market- and technology-oriented practices.

Findings

This chapter strives to present the main findings concerning how tourism entrepreneurs have addressed this crisis by changing their BMs by way of building and applying their DCs. Relying on the findings discovered at two stages during this crisis, a comprehensive picture is illustrated in terms of the various DCs that lead to BM changes over time. The recognized DC-based practices are explained as, resource-, market- or technology-related practices by reference to BMI (innovations) or any incremental change to the existing BM elements (adjustments). is a graphical illustration of the main findings and present several quotations from the interviews to explain DCs, practices, BM changes, and interrelated practices.

Resource-related practices

Resource-related practices and the consequent BM changes are illustrated in detail in , which shows that the DC-based entrepreneurial practices that are inherently resource-based are the most crucial and are characterized by five practices: resource transformation, new human resource (HR) practice development, building slack financial resources, development of more efficient ways of doing business, and using and managing knowledge. Resource transformation practices explain how agile a company is in aligning its BM with certain new opportunities or altering its resource base to switch to a new business area. Almost all the cases had to cultivate such capabilities of changing their BMs primarily by adjusting value creation, delivery and capture and then by innovating the value proposition. This practice led in one case, to the creation of a new BM in addition to the existing BM.

Table 2. Resource-related practices and the consequent BM changes.

The next imperative practice, employed by almost all cases, focuses on HR and explicates how companies are required to develop new HR management practices to overcome the crisis. Here, the DCs mostly set the stage for the adjustments in value creation and delivery. To overcome the crisis, three cases emphasized the importance of having slack financial resources in terms of raising extra funding either externally through innovation grants (innovations) or internally through prior savings (adjustments). Among the resource-related practices, the two practices of knowledge management and the development of more efficient ways of doing business more than others resulted in the implementation of innovations, as the cases needed to innovatively change value proposition, creation and capture. These two practices, which mostly stimulate BMIs represent innovative DCs, whereas new HR practices development underlies adaptive DCs. Furthermore, the two practices of resource transformation and building slack financial resources result from both adaptive and innovative DCs and set the stage for both BMIs and BMAs equally, thus such DCs can be called adaptive-innovative DCs.

Market-related practices

demonstrates market-related practices alongside BM changes. These business practices include market trend recognition, creating new partnerships, customer retention, and building community embeddedness. Given market trend recognition, all seven cases were able to recognize new market trends; here changes mostly informed value creation for the new domestic market and were either extension of current products or inventions of new offers based on the needs and desires of the new guest segment. Interestingly, the majority of cases (five) further cultivated the capability to make new partners during the pandemic as suggested by the second data collection round. This cultivation might have occurred because the task of acquiring such an innovative capability and enacting the related practices requires time; since this crisis has lasted much longer than expected, and stopped most tourism activities, it has thus allowed for more free time to be invested in finding new partners to address the crisis collectively and innovatively alter value creation and delivery. This entrepreneurial practice arises from having an innovative DC, which mostly results in BMIs.

Table 3. Market-related practices and the consequent BM changes.

The next practice is focused on retaining the customers who booked their trips either before or during the crisis. For this purpose, three cases had to make certain adjustments in their terms and conditions. Two cases pointed to the importance of building community embeddedness through either moving towards the local market (innovation in value proposition) or involving locals as a critical aspect of the value creation and delivery processes. Market trend recognition and customer retention underpin adaptive capabilities, which mostly inform BMAs while building community embeddedness arises from an adaptive-innovative capability.

Technology-related practices

Technology-related entrepreneurial practices are shown in , where the findings suggest that the companies needed to apply technology by conducting these three practices: making use of digital communication, creating new booking systems, and developing new apps and web solutions. The former practice is based on an adaptive capability and has been developed by obtaining digital communication skills to practice home officing and new methods of communication. An exception is Alpha, which started to use digital site visits as a new alternative to physical site visits, thus the former value creation has been changed innovatively to generate a new competitive advantage.

Table 4. Technology-related practices and the consequent BM changes.

Based on the second data round, Epsilon elaborated on how the company has invested in state-of-the-art technological solutions to deliver an innovative value proposition (a new app for a new Norwegian segment) as well as innovatively change value creation, delivery, and capture (a new technological tool and a dynamic packaging system). Furthermore, Epsilon argued that the pandemic resulted in tourism activities remaining on-hold, and hence, it has freed up time and resources, which were transformed and targeted towards technological advancement. To remove physical interactions in booking processes and increase efficiency, two cases have launched new online booking systems. The two latter practices (creating new booking systems, apps and web solutions) resulted from innovative capabilities.

DCs types

As discussed previously, the findings show three types of DCs consist of innovative, adaptive and adaptive-innovative. Accordingly, synthesizes and summarizes the findings concerning DC types and their underlying practices across the cases. Given BMIs and BMAs, Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Epsilon mostly implemented BMIs, whereas Delta, Zeta and Eta are focused mainly on BMAs. Among the 12 practices, the five practices of creating new partnerships, new HR practice development, market trend recognition, making use of digital communication and resource transformation were put into practice by almost all the cases. These practices mostly inform the application of adaptive DCs rather than innovative DCs, except for the creation of new partnerships.

Table 5. DCs types and underlying practices with respect to BM changes across cases.

Discussion

This research aimed to explore how tourism entrepreneurs change their BMs to tackle the crisis and to develop a taxonomy of DC-based entrepreneurial practices underlying BM changes. Thus, the overall purpose of the current study was to bridge the knowledge gap in terms of providing a more comprehensive understanding of what underlies a DC as integral to BM changes in the face of crisis (Inigo et al., Citation2017; Jiang et al., Citation2021b; Kump et al., Citation2019; Mansour et al., Citation2019; Mezger, Citation2014; Schilke et al., Citation2018). Hence, this study made theoretical contribution to the DC literature by further enriching the DCs perspective. As shown in , 12 critically important DC-based practices are identified and categorized into resource-, market-, and technology-related practices. In comparison with other classifications of DCs that can be found in the literature (Inigo et al., Citation2017; Jiang et al., Citation2021b; Mansour et al., Citation2019; Mezger, Citation2014), this taxonomy discusses DCs more thoroughly concerning their type (innovative, adaptive, or adaptive-innovative) and the underlying practices, that clarify the operationalization of the DCs that give rise to BM changes in various ways.

For instance, compared to the most recent study by Jiang et al. (Citation2021b), which discussed resource-based practices, the current study goes beyond prior typologies by investigating the practices empirically, and also focuses on the elements of the market and technology. Prior studies pinpointed (Inigo et al., Citation2017; Mezger, Citation2014) the latter two elements in terms of sensing and seizing technological and market-based knowledge to build BMIs. In addition, the results provide a deeper understanding of the nature of DCs (Leih et al., Citation2015), which can vary given that BMAs result from adaptive capabilities, while BMIs rely on innovative capabilities (Jiang et al., Citation2021b; Saebi, Citation2015). Consistent with Jiang et al. (Citation2021b), it can be concluded that even on a low scale, those cases that succeeded in developing innovative capabilities and enacting the relevant practices (for instance Beta and Gamma) signify the creation of BMIs regardless of how many practices are implemented; therefore, the nature of DCs, whether innovative or adaptive, explains BM changes.

Following prior studies (Inigo et al., Citation2017; Saebi, Citation2015), BM changes on the right side of , are characterized as BMAs resulting from incremental changes and BMIs resulting from radical changes in terms of the configuration of a new value proposition, which demands the alignment across BM components through the establishment of a new mechanism for value creation and capture (Mezger, Citation2014; Teece, Citation2018). The new value proposition can be configured through a new BM whose components are changed simultaneously (Mezger, Citation2014). Similarly, Inigo et al. (Citation2017) highlighted radical BMIs that embrace systematic changes across value propositions. Furthermore, as the findings suggest, innovations are more likely to occur when companies conduct practices that are resource- or technology-related, whereas market-related practices mostly provoke adjustments, except for the practice of creating new partnerships. Likewise, Kump et al. (Citation2019) argued that being aware of customer needs and market trends supports an adaptive capability rather than an innovative capability. This claim is in contrast with Mezger’s (Citation2014) findings that state market-oriented practices significantly contribute to BMIs. Nonetheless, the importance of integrating external competences and resources through the creation of new partnerships is highlighted by reference to BMIs (Mezger, Citation2014) and supported by our research through reflection on the temporal aspect of DCs.

This research also contributes to the DC literature by reflecting on the temporal aspects of DCs (Eriksson, Citation2014; Jiang et al., Citation2021b; Schilke et al., Citation2018), which is accomplished by examining DCs for two stages during this crisis. Five informants claimed that the pandemic had a long duration and that being unable to engage in any international tourism activities made more time available to encourage innovations, although two informants asserted at their first interview that they could not find much free time to consider innovations. While the changes during the first stage mostly informed adjustments, later in the crisis, innovations were more prevalent than adjustments. This finding is in line with those of a recent study by Breier et al. (Citation2021), which regarded free time as a driver of BMIs. In addition, Schilke et al. (Citation2018) argued that time is a critical factor regarding the evolution of the DCs underlying changes since DCs grow as long as organizations acquire experience through learning-by-doing. Considering this temporal aspect, two innovative practices, creating new partnerships and creating new apps and web solutions, which also mainly underlie BMIs, were developed further during this crisis, as the second round of data denotes, whereas the four practices of new HR practice development, resource transformation, using and managing knowledge, and building slack financial resources were invoked when the crisis hit and then enhanced afterward, as demonstrated by the second interview round.

Given BMIs, first, start-ups and then businesses in growth are notably seeking new opportunities for innovations (more so than the incumbent), because it is usually easier for smaller firms to transform, as they can adapt more flexibly (Jiang et al., Citation2019) and have “fewer fixed assets to redeploy, and fewer established positions to re-engineer” (Leih et al., Citation2015, p. 32). Incumbents, however, have learned how to adapt to exogenous shocks from their experience of previous recessions (Cucculelli & Peruzzi, Citation2020); such experience is highlighted by Eta, that learned how to allocate financial resources efficiently after experiencing the 2008 financial crisis. Relatedly, companies that hold limited slack resources respond to crises reactively rather than proactively (Jiang et al., Citation2021b).

To address the matter of recovery in general, the cases have pursued various approaches. While some changed their market focus from international to domestic guests, others concentrated on BMAs and mobilizing their resources for winter 2021. Although domestic visitors can accelerate recovery and contribute significantly to building resilience, returning to business-as-usual may lead to overcompensation for the revenue that is lost due to travel restrictions (Gössling et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the great dependence of Arctic tourism on international arrivals makes it vulnerable to adversities that result in border closure. Although several cases admit that they had always considered hosting domestic guests and customizing offers, none had tried to approach this segment before the pandemic, meaning that if companies had targeted domestic guests previously, the companies could have adapted more efficiently. Such a finding corresponds to the study by Ritter and Pedersen (Citation2020), who indicated that some DC-based practices that were understood as complex and costly before this crisis was suddenly perceived as practical and critical during this crisis. Indeed, this issue also demands collective dedication from all stakeholders to promote Arctic winter tourism for domestic guests to not only ensure resilience at the firm and industry levels but also try to prevent a return to a business-as-usual approach in which overcompensation could pose additional challenges. Similarly, Seeler et al. (Citation2021) argued that the future recovery and sustainability of Norwegian tourism strongly depends on designing a new value proposition for domestic guests to mitigate the industry’s vulnerability as a result of heavy reliance on international guests.

Conclusions

This research strives to examine how tourism entrepreneurs in Arctic change their BMs in light of their DCs to tackle the crisis and enhance resilience. Relying on the temporal qualitative data from seven small companies, the results illustrate a comprehensive overview of various DCs (innovative, adaptive, or adaptive-innovative) that are operationalized through various practices and lead to either BMAs or BMIs over time. This research identifies 12 DC-based entrepreneurial practices in three areas: resource, market, and technology. Thus, this study contributes to the literature concerning BMI and DCs in tourism crisis management. However, this research has some limitations in addition to its contributions.

Due to the small number of cases, which were small nature tourism companies in the Arctic, the findings might not be applicable to larger organizations or settings other than tourism. Considering that the entire tourism industry has grappled with the pandemic, more research is required in a broader sense. Given the methodology and pandemic, the current research faces several challenges and inevitable shortcomings that can be addressed by future endeavors. The research results rely mainly on online interviews, as the interviewer could not examine the data further through observation. Hence, researchers can bridge such gaps after the pandemic by implementing a mixture of data collection methods to investigate the performance of resilient BMs post-pandemic, which is as important as investigating such BMs during the pandemic. Moreover, more research is needed to determine whether transformations during the crisis would remain permanently postcrisis even after returning to normal following the crisis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Battisti, M., & Deakins, D. (2017). The relationship between dynamic capabilities, the firm’s resource base and performance in a post-disaster environment. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(1), 78–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615611471

- Biggs, D., Hicks, C., Cinner, J., & Hall, C. (2015). Marine tourism in the face of global change: The resilience of enterprises to crises in Thailand and Australia. Ocean & Coastal Management, 105, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.12.019

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2011). Grounded theory: A practical guide. Sage Publications.

- Breier, M., Kallmuenzer, A., Clauss, T., Gast, J., Kraus, S., & Tiberius, V. (2021). The role of business model innovation in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92(102723), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102723

- Brück, T., Llussá, F., & Tavares, J. (2011). Entrepreneurship: The role of extreme events. European Journal of Political Economy, 27, S78–S88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2011.08.002

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publication.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.): techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE Publications.

- Cucculelli, M., & Peruzzi, V. (2020). Post-crisis firm survival, business model changes, and learning: Evidence from the Italian manufacturing industry. Small Business Economics, 54(2), 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0044-2

- Dahles, H., & Susilowati, T. (2015). Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.01.002

- Duarte Alonso, A., Kok, S. K., Bressan, A., O’Shea, M., Sakellarios, N., Koresis, A., Koresis, A., Solis, M. A. B., & Santoni, L. J. (2020). COVID-19, aftermath, impacts, and hospitality firms: An international perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102654

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

- Eisenhardt, K., & Graebner, M. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Eriksson, T. (2014). Processes, antecedents and outcomes of dynamic capabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2013.05.001

- Foss, N., & Saebi, T. (2017). Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? Journal of Management, 43(1), 200–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316675927

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Hall, C., Prayag, G., & Amore, A. (2017). Tourism and resilience: Individual, organisational and destination perspectives (Vol. 5). Channel View Publications.

- Inigo, E., Albareda, L., & Ritala, P. (2017). Business model innovation for sustainability: Exploring evolutionary and radical approaches through dynamic capabilities. Industry and Innovation, 24(5), 515–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2017.1310034

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B., & Verreynne, M. (2019). Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(6), 882–900. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2312

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B., & Verreynne, M. (2021a). Building dynamic capabilities in tourism organisations for disaster management: Enablers and barriers. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1900204

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B., & Verreynne, M. (2021b). A resource-based typology of dynamic capability: Managing tourism in a turbulent environment. Journal of Travel Research, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211014960

- Kraus, S., Clauss, T., Breier, M., Gast, J., Zardini, A., & Tiberius, V. (2020). The economics of COVID-19: Initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(5), 1067–1092. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-04-2020-0214

- Kump, B., Engelmann, A., Kessler, A., & Schweiger, C. (2019). Towards a dynamic capabilities scale: Measuring sensing, seizing, and transforming capacities. Industrial and Corporate Change, 28(5), 1149–1172. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dty054

- Lee, Y.-S., Weaver, D., & Prebensen, N. (2017). Arctic tourism experiences production, consumption and sustainability. CABI.

- Leih, S., Linde, G., & Teece, D. (2015). Business model innovation and organizational design: A dynamic capabilities perspective. In N. Foss, & T. Saebi (Eds.), Business model innovation: The organizational dimension (pp. 24–42). Oxford University Press.

- Leonidou, L., Leonidou, C., Fotiadis, T., & Aykol, B. (2015). Dynamic capabilities driving an eco-based advantage and performance in global hotel chains: The moderating effect of international strategy. Tourism Management, 50, 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.03.005

- Manolova, T., Brush, C., Edelman, L., & Elam, A. (2020). Pivoting to stay the course: How women entrepreneurs take advantage of opportunities created by the COVID-19 pandemic. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 38(6), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620949136

- Mansour, H., Holmes, K., Butler, B., & Ananthram, S. (2019). Developing dynamic capabilities to survive a crisis: Tourism organizations’ responses to continued turbulence in Libya. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2277

- Matteucci, X., & Gnoth, J. (2017). Elaborating on grounded theory in tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 65, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.003

- McDermott, K., Kurucz, E., & Colbert, B. (2018). Social entrepreneurial opportunity and active stakeholder participation: Resource mobilization in enterprising conveners of cross-sector social partnerships. Journal of Cleaner Production, 183, 121–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.010

- McKercher, B., & Chon, K. (2004). The over-reaction to SARS and the collapse of Asian Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 716–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.11.002

- Mezger, F. (2014). Toward a capability-based conceptualization of business model innovation: Insights from an explorative study. R&D Management, 44(5), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12076

- Miles, M., Huberman, A., & Saldaäna, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons.

- Pedersen, C. L., & Ritter, T. (2020). Preparing your business for a post-pandemic world. Harvard Business Review. Digital article at HBR.org.

- Ratten, V. (2020). Coronavirus (Covid-19) and entrepreneurship: Cultural, lifestyle and societal changes. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(4), 747–761. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-06-2020-0163

- Ritter, T., & Pedersen, C. (2020). Analyzing the impact of the coronavirus crisis on business models. Industrial Marketing Management, 88, 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.014

- Saebi, T. (2015). Evolution, adaptation, or innovation? A contingency framework on business model dynamics. In N. Foss, & T. Saebi (Eds.), Business model innovation: The organizational dimension (pp. 147–168). Oxford University Press.

- Saunders, M. N., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Schaltegger, S. (2020). Sustainability learnings from the COVID-19 crisis. Opportunities for resilient industry and business development. Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal, 12(5), 889–897. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-08-2020-029

- Schilke, O., Hu, S., & Helfat, C. (2018). Quo vadis, dynamic capabilities? A content-analytic review of the current state of knowledge and recommendations for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 390–439. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0014

- Seeler, S., Høegh-Guldberg, O., & Eide, D. (2021). Impacts on and responses of tourism SMEs and MEs on the COVID-19 pandemic – the case of Norway. In S. Kulshreshtha (Ed.), Virus outbreaks and tourism mobility (pp. 177–193). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.2307/259271

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- Teece, D. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

- Teece, D. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 172–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003

- Teece, D. (2018). Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.06.007

- Teece, D., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Thomas, R., & Wood, E. (2014). Innovation in tourism: Re-conceptualising and measuring the absorptive capacity of the hotel sector. Tourism Management, 45, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.03.012

- Van Burg, E., Cornelissen, J., Stam, W., & Jack, S. (2020). Advancing qualitative entrepreneurship research: Leveraging methodological plurality for achieving scholarly impact. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 46(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720943051

- Yin, R. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

- Zahra, S., Sapienza, H., & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 917–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00616.x