ABSTRACT

Sustainable tourism development asks for coordinated and collective action where destination management organisations (DMOs) are considered a crucial steering stakeholder. The aim of this study is to explore the current state of implementation of the internationally renowned destination sustainability standards from the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) in Alpine destinations (Switzerland, Austria, Germany, and Italy). Drawing from a survey (n = 80) with destination managers, it explores (1) the attributed importance, (2) the self-assessed level of implementation, as well as (3) the expected future importance of the GSTC criteria. Despite the indicated importance, the degree of implementation lags significantly behind. This lack of implementation is critical, especially since the DMOs attach even greater importance to these issues in the future. Further research needs to address how to close the identified gap between the perceived importance and actual implementation to advance in this urgent challenge of sustainable transformation.

Introduction

In the academic discourse, the aspects of sustainability in tourism have been growing exponentially since 1987, according to a recent bibliometric analysis from Niñerola et al. (Citation2019). Moreover, sustainable development is not only gaining importance as a theoretical development concept in the academic literature but also in the strategic development and implementation plan of various tourism actors (Bonzanigo et al., Citation2016). The Covid-19 crisis currently highlights the necessity for resilient and sustainable tourism forms and, thus, is a key strategic goal in the ongoing discussions about the future of the tourism industry sustainability (e.g. One Planet Vision for a Responsible Recovery in the Tourism sector (UNWTO, Citation2020)). The transition towards a sustainable tourism system is especially crucial in a sensitive ecosystem-like alpine destination where the negative impacts of climate change, as well as the societal challenges that often come from the inherent seclusion, are increasingly noticeable.

The complexity of sustainability, and especially in the context of the extremely fragmented tourism destinations, asks for collective and coordinated action to implement measures towards a more sustainable tourism development where the local destination management organisation (DMO) as a steering organisation plays a central role. However, there is still little empirical research on the consideration and level of implementation of different sustainability aspects of local DMOs as well as on the self-perceived role of the DMO in the context of sustainable development. Therefore, the objective of this web-based survey research is to gain a better understanding of how sustainability is translated into practice in mountain destinations by exploring the following research questions:

Which aspects of sustainable tourism, according to the GSTC destination criteria, are currently being considered important by local DMOs in alpine destinations?

To what degree have these aspects already been implemented?

How is their future importance assessed?

Furthermore, this explorative study investigates the perceived role of the local DMO in the interplay with other tourism stakeholders and the political authorities towards sustainable development.

The paper contains first an overview of relevant literature on sustainable development in mountain destination, sustainable tourism governance and the role of the local DMOs in it. Then, an overview of the applied methodology is given and the main results from the survey are presented. Last, the results are discussed and set into context regarding the existing literature and further research possibilities to deepen the understanding of the crucial role of local DMOs in the transformation towards more sustainable tourism is given.

Literature review

Sustainable development in mountain destinations

Sustainability in tourism is becoming a crucial development paradigm. Sustainable tourism development is built on the concept of sustainable development coined in the Brundtland Report in 1987, which balances ecological, social, and economic development to ensure prosper conditions also for future generations. As emphasised by the UNWTO (Citation2005, p. 2), “Sustainable tourism is not a discrete or special form of tourism. Rather, all forms of tourism should strive to be more sustainable”. To achieve this path of sustainability transformation, concrete and impactful measures must be taken by stakeholders in the industry, society, and politics.

In sensitive ecosystem-like alpine tourism destination especially ecological impacts are receiving greater awareness. The importance of sustainable development in fragile mountain ecosystems has already been acknowledged in a chapter of the action plan Agenda 21 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Rogora et al. (Citation2018) highlight in their long-term study in the Swiss, Austrian, and Italian Alpine regions the rapid response of these ecosystems to climate change. Effects like limited snow coverage, impacts on freshwater ecosystems or increases in soil temperature have been reported. Due to their high altitude and topology, these environments also show high levels of biodiversity (Winkler et al., Citation2016) and a major threat to this biodiversity above the tree line is climate change (Rogora et al., Citation2018). Additionally, mountainous regions are experiencing a more rapid warming than the global average, and it is expected to further accelerate in the twenty-first century (Gobiet et al., Citation2014; Mountain Research Initiative EDW Working Group, Citation2015). Moreover, the various ecological impacts of the ongoing temperature increase and change in irrigation patterns lead to lower natural snow reliability, and studies show that the number of snow days decreased since the 1980s by 20–60% (Marty, Citation2008). This threatens the currently still prevailing business model of winter sport destinations (Bonzanigo et al., Citation2016; Steiger et al., Citation2019) and the necessity of sustainability has thus also received greater attention from a wider audience outside the academia.

Sustainable tourism development in Alpine destination has been researched in various empirical studies. These studies show that in practice, measures of varying severity have been put in place by tourism stakeholders in the recent decades which now results in different degrees of sustainability transformations. As described by Dornier and Mauri (Citation2018), tourism in the Alpine space (including the eight countries Switzerland, Austria, Liechtenstein, Germany, Italy, France, Monaco, and Slovenia) is becoming more diversified and different perspectives and levels of analysis are necessary to address the various issues. This variety has been researched in different mountainous regions (Paunović & Jovanović, Citation2019) or between different countries in the Alpine region (Kuščer et al., Citation2017). Paunović and Jovanović (Citation2019) conclude in their comparative study of the Alps and Dinarides that in the Alps transdisciplinary development policies are better implemented due to a longer tradition in transnational sustainability efforts (e.g. Alpine Convention). Their research on social representations focused on differences between stakeholder integration, planning for sustainable development, leadership values and priorities of the overall destination development. Kuščer et al. (Citation2017) relate in their comparative research the sustainable tourism development in different destinations in Austria, Switzerland, and Slovenia to the destination’s level of innovation and contextual environment. Different stages of development were illustrated, whereas Switzerland was outperforming Austria and Slovenia in most aspects. Furthermore, Paunović and Jovanović (Citation2017) also researched a country-specific case in their qualitative study on the implementation of sustainable development in the German Alps and concluded that stakeholder engagement, cross-border cooperation, and indicators for sustainable tourism are key themes to consider. Lastly, the cross-stakeholder perspective on a DMO level is considered valuable to manage visitor streams or create incentives for a holistic experience within a destination, that encourage guests to extend their stays and thereby reducing the usage of transportation (Morrison, Citation2019; Pérez Guilarte & Lois González, Citation2018; Reinhold et al., Citation2015).

Sustainable tourism governance

Tourism is considered a multi-stakeholder industry with various objectives and interests which success depends on the active involvement of these stakeholders (Byrd, Citation2007). Nguyen et al. (Citation2019), however, observe that the common stakeholder involvement is only a complementary part of the overall approach towards sustainable destination achievements, which must also include non-human actors such as place, culture, or technology, and the bottom-up power of such “tourismscapes”, as they are named by the authors. Their conceptual framework incorporates these unclaimed voices and transitions them, together with those of the key actors, into destination governance. Furthermore, for successful sustainable destination development, Roxas et al. (Citation2020) argue that effective governance is a key aspect and the interaction between the different stakeholders like authorities, tourism businesses, local community, and visitors needs to be further clarified. It needs a collective effort, well-thought structures, and clear responsibilities for this change to happen. To deal with these challenges in a systematic and democratic way, the notion of governance from social science literature has become increasingly acknowledged in tourism research (Bramwell & Lane, Citation2011; Hall, Citation2011). Niñerola et al. (Citation2019) show in their bibliometric analysis of sustainable tourism literature of the last 30 years that there is increasing research focus on strategic issues like tourism governance for sustainable development. However, even though the concept of governance is widely used in academia and by policymakers, there is no consensus on its definition (Nunkoo, Citation2017). Generally speaking, “Governance is ultimately concerned with creating the conditions for ordered rule and collective action” (Stoker, Citation1998, p. 17). There have been different studies about sustainability governance, researching, for example, the role of the state (Bramwell, Citation2011), the political environment as a necessary enabler (Mihalič et al., Citation2016), the role of trust, power and social capital (Nunkoo, Citation2017), indicators to evaluate tourism governance (Pulido-Fernández & La Pulido-Fernández, Citation2018), and also studies on framework interaction and possible changes of these roles (Roxas et al., Citation2020) or research focusing on governance and subsidiarity aspects regional tourism organisations (RTOs) (Zahra, Citation2011).

The DMOs are a key player to instil change in the way local tourism service provide tourism services. The role of non-state actors deemphasising the power of the state in the social network is increasingly considered in the pluralistic approach to policy-making implied by the governance concept (Hezri & Dovers, 2006 in Nunkoo, Citation2017). Several studies emphasise the importance of public-private interaction where government and non-government stakeholders work together on destination governance (Roxas et al., Citation2020). According to Roxas et al. (Citation2020, p. 390) “there has been a scarce discussion on the roles, synergy, and co-responsibilities of tourism stakeholders”. This discussion becomes even more important when considering the current shift of the role of the DMO from pure marketing towards management and strategic destination development (UNWTO, Citation2019). These changing roles of management organisation and actors are also considered one of four trends in the tourism governance literature (dos Anjos & Kennell, Citation2019).

Up to date, the implementation of sustainability measures is based on voluntary initiatives that are ideally anchored within a wider destination strategy. To orientate the measures, voluntary industry standards and certification schemes are becoming an important guideline. The practice and application of certification and industry standards in sustainable tourism has also received attention in research (Bricker & Schultz, Citation2011; Font & Harris, Citation2004; Font & Sallows, Citation2002; Klintman, Citation2012). As the issue of sustainable development gains urgency, the number of certification schemes and industry standards is also growing exponentially. Derkx and Glasbergen (Citation2014) have analysed the role meta-governance concepts and their potential to address what they call “orchestration deficit” in various fields (organic agriculture, fair labour, and sustainable tourism). In sustainable tourism, global standard setters such as the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) have addressed the need for meta-governance and created a bottom-up process of voluntary collaboration. GSTC Partnership was launched in 2007 as a coalition of 32 partners, initiated by the Rainforest Alliance, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the United Nations Foundation (UN Foundation), and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and merged in 2010 with the Sustainable Tourism Stewardship Council (STSC). The goal was to develop a set of baseline criteria to come to a common understanding of how sustainable tourism can be defined and operationalised (GSTC, Citation2021).

The GSTC criteria have become an international reference point for defining and operationalising sustainable tourism for all tourism stakeholders (Derkx & Glasbergen, Citation2014). Having such an internationally accepted guiding framework helps to have a common ground to evaluate initiatives and certifications. Sustainability standards thereby “are used for education and awareness-raising, policy-making for businesses and government agencies and other organization types, measurement and evaluation, and as a basis for certification” (GSTC, Citation2022a). Thus, for the research aim of this paper, the GSTC criteria will also serve as a guiding framework to better understand the current sustainable development of Alpine destinations.

The role of local DMOs in sustainable tourism governance

Given the complexity of sustainable development but also the inherent complexity of tourism, collective action, efficient planning, and management processes are required (dos Anjos & Kennell, Citation2019). Therefore, a coordinating body is crucial to efficiently achieve a transformation towards sustainable tourism. As sustainable development is a long-term strategic goal, it needs to be considered beyond its operational tasks and thus, the DMO plays a key role in formulating a vision and integrating sustainability into the overall destination strategy or even elaborating a specific sustainable tourism development plan (Morrison, Citation2019; Wagenseil & Zemp, Citation2016). Morrison (Citation2019) predicts “the DMO of the future to be the forefront in promoting sustainable tourism and other initiatives designed to protect the environment” (p. 669). The DMO emerges as a key player for destination development and management even though its mandate is defined to different extents. As indicated by Pearce (Citation2016), the destination management literature is diverse and often, the term DMO is not explicitly defined and the “M” ranges from marketing to comprehensive management and development functions. However, the role of the DMO is currently changing more and more from a pure marketing purpose to a broader management and strategic role in order to enhance the destination’s competitiveness (UNWTO, Citation2019). The DMO itself has different governance structures that range from a single public authority to public-private partnership models to also, however rarely, entirely private models.

Fundamental roles and responsibilities of a DMO regarding sustainable development lie among others, within strategic planning, formulation (or participation in formulation), and implementation of the destination’s tourism policy, tourism product, and business development (UNWTO, Citation2019). An assessment study of sustainability indicators in the Drakensberg Mountains in South Africa underlines the importance of a centralised knowledge management and monitoring solution. The research examined the sustainability approaches of individual stakeholders and identified a clear need for synchronised action to overcome the limitations in the overall concept of sustainability that they consider to exist when different stakeholders operate in the same area (Mutana & Mukwada, Citation2017).

The DMOs have such a coordinating role within a tourism destination and are therefore an important player in the sustainability transition. Besides the local DMO, also local political authorities have a guiding role and are significant to set the necessary policy framework for sustainable development. The DMO can be seen as a link between the political authorities (national, regional, and local) that should steer sustainable development with their policies and the local tourism industry that should carry out the measures and thus, contribute with sustainable tourism offers to such a development. Such coordinating actors are necessary to keep the big picture in mind, ensure a mid to long-term planning horizon and to establish compromise between often conflicting economic, environmental, and social interests in tourism development. The interplay between authorities, DMOs and tourism service providers and the cooperation between these actors but also between different destinations are important. As an example, Bonzanigo et al. (Citation2016) outlined that over the last decade, many cooperative research projects regarding climate change adaptation in the alpine region have been financed by the European Commission indicating a belief in this approach.

The DMO represents an important strategic tourism player within a destination. DMOs are perceived to attract tourists to a destination and represent tourism industry interests (Hall & Veer, Citation2016). Various research regarding the role of the DMO in a destination have been carried out in the context of competitiveness (Minguzzi, Citation2006), success factors (Volgger & Pechlaner, Citation2014), crisis management and organisational learning (Blackman & Ritchie, Citation2008), as well as coordination (Beritelli et al., Citation2015). However, so far, only few studies explicitly researched the role of the DMO in terms of sustainable development (e.g. regarding the mindfulness and social responsibility of destination management (Morgan, Citation2012); relating to resilience (Pechlaner et al., Citation2019), or the perceived and actual role of DMO (Wagenseil & Zemp, Citation2016)). Wagenseil and Zemp (Citation2016) indicated in their study that the need for sustainable tourism planning can be observed in organisational adjustments like creating positions responsible for sustainable development. Even though the tourism industry is known to be fragmented, DMOs and government can have a guiding role to achieve common long-term goals. Jones et al. (Citation2014), for instance, attribute a leading role in sustainability to hotel chains, but they also point to the need for a central information channel regarding the topic. Adding on this, it should be noted that in rural Alpine regions often small independent lodging establishments are found. The study by Wagenseil and Zemp (Citation2016) further shows that DMOs consider having the necessary skills to become a sustainability leader in a destination, however, they currently lack the necessary financial and time resources. Thus, little empirical research on local DMOs and their role in sustainable tourism governance and their interpretation of the importance and implementation of sustainable development has been done so far. Within the tourism literature, there are only few but very recent studies that have been published after the completion of the empirical research part of this study but nonetheless are important to mention in this context: the study by Haid et al. (Citation2021), which qualitatively examines the implementation of sustainability measures in Tyrol and New Zealand and the study by Rivera et al. (Citation2021) which examines the influence of Covid-19 and a possible increase in demand for sustainable tourism products on DMOs sustainability efforts.

Research goals

The review of the literature shows that in the implementation of sustainability measures, tourism businesses have a large impact lever; however, DMOs can also play an important role in the sustainability transformation of a destination. This study aims to further contribute to the above-mentioned research gap regarding the role of local DMOs. Therefore, Alpine mountain DMOs in Switzerland, Germany, Austria, and Italy are surveyed regarding their self-assessment of the current importance and implementation of sustainable destination development, their understanding of their role as sustainability enabler as well as potential barriers. The guidelines from GSTC for evaluating destination sustainability have been used as a basis for the evaluation. Within this framework, four areas are considered: sustainable management, socio-economic sustainability, cultural sustainability, and environmental sustainability. This research also aims to further the discussion on the role of DMOs in the path towards sustainable tourism and should give insights on potential challenges that DMOs face to put the strategy into process

Especially the relation between different sustainability aspects and their current and future importance can give some indication of where DMOs perceive that increased future effort will lie. Furthermore, the hypothesis is made that, in general, the DMOs consider sustainability or at least aspects of it as more important than they have already succeeded to implement measures. This could indicate a prevailing attitude-behaviour gap meaning that even though sustainability is considered as important, the behaviour is not always accordingly. Research concerning sustainable tourist behaviour has already shown that this effect prevails (Antimova et al., Citation2012; Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014). This is a well-described phenomenon on the individual behaviour level regarding sustainable consumption and is proven in many different consumer areas (fashion consumption (Park & Lin, Citation2020), transportation choices (Haider et al., Citation2019), renewable energy (Claudy et al., Citation2013), food consumption (Vermeir & Verbeke, Citation2006)). Thus, having indicators from the survey of Alpine DMOs about perceived importance and actual implementation allows having an idea if this phenomenon can also be observed for institutional players like a DMO. Furthermore, the reported challenges that hinder them to act more sustainably are also of interest to gain a better understanding of these challenges and address them in the future.

Research methodology

Survey design

This study takes an explorative approach to better understand the self-identified roles of the local DMOs in the sustainability transformation and their overall assessment of the importance and implementation of various sustainability aspects. The GSTC has developed global standards for sustainable tourism and travel (GSTC Destination Criteria version 2, published January 2020). In a widely consulted process, an internationally renowned set of criteria for sustainable destination development was created (Derkx & Glasbergen, Citation2014). These criteria serve as a basic guideline for sustainable destination development and are also considered in destination certification schemes by major certification bodies (e.g. Biosphere, Vireo, EarthCheck). In this context, it needs to be noted that the GSTC does not conduct destination certifications itself but certifies third parties that aim to do such assessments, which ensures comparable quality standards (GSTC, Citation2022b). As a proxy variable for sustainable development a selection of the destination criteria from GSTC was used to operationalise the rather abstract term of sustainable development and have an instrument to quantitatively survey the level of importance and implementation of these items.

The final survey instrument was a self-administered questionnaire consisting of fixed choice questions. The survey consisted of three main parts. The first part focused on the DMOs and destinations’ characteristics such as number of employees, number of overnights and seasonality. The second part of the survey covered the DMO’s understanding of responsibility towards sustainable development and the DMO’s sustainability efforts. For example, DMOs were asked who they perceive to be the carrier of the main responsibility of sustainability tasks in their destinations, whether sustainability was already integrated into their mandate, if a respective sustainability certification was achieved, as well as the factors they perceive to be in support or opposition of a more sustainable development of their destinations. The third and last section of the survey asked DMOs to rate 23 GSTC destination criteria (GSTC, Citation2019) from their perspective in terms of current importance and implementation, as well as future importance. A selection of 23 criteria out of the 38 criteria in total was chosen based on experts’ opinion on which criteria were deemed most relevant for European Alpine destinations and balanced the length of the survey to reduce risk of early termination from respondents. For example, criteria were excluded if the fulfilment of such was presumed to be common practice or empowered by law or regulations. Finally, 9 criteria from the Sustainable Management section (out of 11 criteria), 2 criteria from Socio-economic Sustainability section (out of 8), 3 criteria from the Cultural Sustainability section (out of 7) and 9 criteria (out of 12) from the Environmental Sustainability section were included in the survey as shown in . To operationalise the criteria, the original description of the criteria was translated into German. Also, with the goal of increasing the response rate each criterion was shortened and limited to its essential statement. Respondents were then asked to rate each criterion three times on a five-point Likert-scale. Firstly, on how important they perceive this criterion to be for their destination (1 = not important at all/5 = very important). Secondly, how well they think their destination fulfils this criterion today (1 = not at all/5 = fully) and lastly, if this criterion will increase or decrease in importance for their destination in the future (1 = strongly decrease/5 = strongly increase).

Table 1. The selected 23 GSTC criteria used in the survey.

Data collection

The aim of this study is to gain insights how DMOs themselves perceive the importance of sustainability, the current implementation and their role and responsibilities within a destination. Thus, a quantitative survey questionnaire with Alpine DMOs is considered a suitable method to get to know more about the perception of DMOs in the sustainability discourse. The research focused on Alpine destinations in Switzerland, Austria, Germany, and Italy (South Tyrol) due to similar cultural and language backgrounds to ensure comparability. For the data collection, a purposive sampling strategy was followed where through the websites of the national and regional tourism organisations, the Alpine destinations were identified. A total sample of 355 local and regional Alpine DMOs met the study objective. There were no criteria set that would limit any DMO from participation unless its geographical location was outside of the German-speaking part of the Alpine Convention. However, city destinations were not included in the survey to ensure greater homogeneity in the sample and since only a minority of Alpine destinations could even be considered city destinations. The DMOs were then contacted via personal E-mail and asked to participate in the online survey. The targeted respondents were people in management positions since managers can provide the most valuable insights on strategic issues and the development of destinations (Crouch, Citation2011).

The preliminary survey was pre-tested in Switzerland, which resulted in a few minor linguistical adjustments. The final survey was sent via e-mail with a link to all 355 identified DMOs in July 2020. A reminder was sent after four weeks, which resulted in a total field time of two months. Finally, a total of 80 completed surveys, resulting in a response rate of 23%, were used for the analysis.

Findings

The following chapter is divided into three parts. First, the characteristics of the sample are described. Second, the role and responsibility of sustainable development within a destination are analysed. Third, the destination criteria from GSTC are evaluated depending on the attributed importance (current and future) and the level of implementation. The data was analysed using descriptive analysis and a paired sample t-test. Descriptive statistics were sought to describe the sample and the characteristics of the DMOs who participated in the survey. A paired sample t-test was applied to discover differences in the means to reveal whether DMOs responses regarding the attributed importance (current) and actual implementation differ significantly on average. The postulated hypothesis is that DMOs rank the importance of a sustainability item higher than it is implemented in the destination, thus, showing to a certain degree an attitude-behaviour gap.

Characteristics of the sample

The final sample consists of 20 DMOs from Switzerland (25%), 12 from Germany (15%), 27 from Austria (33.8%) and 21 from Italy (26.3%). The majority (61.3%) of DMOs have 10 or less people employed, another fourth of the surveyed DMOs employ more than 20 persons and 15% indicate a size between 11 and 20 employees. In terms of overnights in 2019 roughly half (51.3%) reported less than half a million, a third (31.3%) reported more than a million and 17.6% reported in between. Finally, 88.4% of the respondents are in a management position (11.6% indicated other), whereas the vast majority (78.2%) of the respondents held the position of CEO in the DMO. Thus, the respondents are assumed to be knowledgeable about the current strategic and operational orientation of the DMO and qualified to participate in this study. shows in more detail the characteristics of the DMOs that participated in the survey.

Table 2. Characteristics of the sample.

Role and responsibility

This research aims to better understand the perspective of the local DMOs regarding their self-identified role and the different tasks that arise in the sustainability transformation of a destination. 61% of the surveyed DMOs indicated that their mandate explicitly demands a sustainability orientation. However, when asking if the DMOs considered themselves currently capable to be a sustainability leader in their destination, 58% declined. The main hindrances (indicated on a five-point Likert-scale) are lack of time (4.2), financial resources (4.0) and personnel resources (4.0). Interestingly, a lack of urgency (2.8) or know-how (2.8) does not seem to be a critical reason for a lack of leadership in this area. Moreover, the DMOs that already saw themselves capable to be a sustainability leader wished for further political support (4.2), better political frameworks (4.1) and more personnel resources to implement projects (4.1).

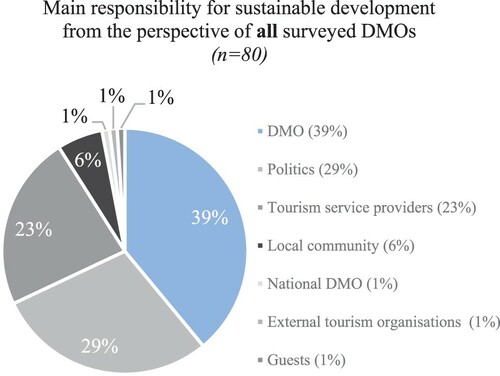

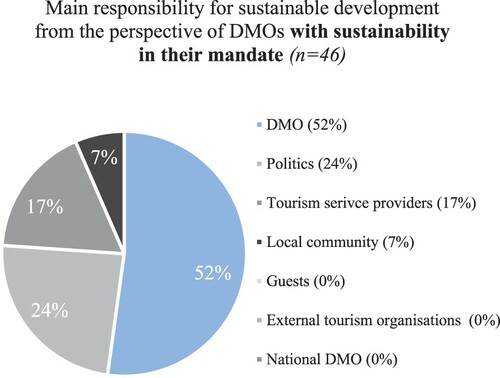

The main responsibility for a sustainable tourism development of a destination is by a majority seen outside their organisation (61%) as illustrated in . DMOs indicate that they see the main responsibility with stakeholders such as political authorities (29%) and local tourism providers (23%) or even the local community (6%). However, at least 39% indicate that they see the main responsibility for a sustainable destination development by themselves. Looking closer at the DMOs that have sustainability integrated into their mandate (), a slight majority see the main responsibility by themselves (52%). In contrast, considering only those that indicate to have no current integration of sustainability in their mandate (n = 29), the main responsibility is even clearer seen outside their organisation (79%), for example, with political authorities (38%) or local tourism providers (28%) and only 21% see themselves as having the main responsibility for a sustainable destination development.

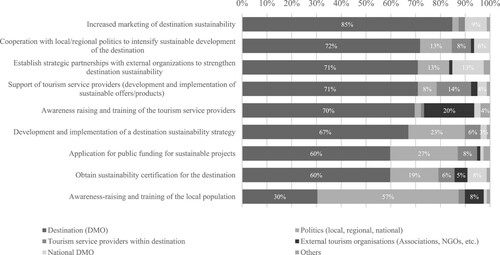

Additionally, when asking about different tasks for a sustainable destination development, the attributed main responsibility shifts among the various stakeholders. Details of the assessment of main responsibilities according to the different tasks can be found in . The marketing aspect is clearly seen as a task of main responsibility from the perspective of the DMO (85%). Also, aspects like building cooperation with local/regional politics (72%) or establishing strategic partnerships with external organisations (71%) to strengthen sustainable development of the destination are on the top priorities for DMOs. Moreover, with the support of local tourism service providers regarding the development and implementation of sustainable tourism products (71%) but also for the development and implementation of a destination-specific sustainability strategy (67%), the DMO is seen to overtake a leading role. The task of awareness-raising and training of tourism service providers falls into the responsibility of DMOs (70%), whereas that of the local population is seen as a responsibility of political authorities (57%) and external tourism organisations like NGOs are also considered to contribute their share of responsibility (20%).

Furthermore, those DMOs that indicated in a task of that they see the main responsibility by themselves were then additionally asked if they were already fulfilling these tasks. The tasks that a great majority indicated to be already fulfilling are Support of tourism service providers (73%), Cooperation with local/regional politics (71%) and Awareness-raising and training of tourism service providers (65%). The tasks that are indicated to be least fulfilled are Obtaining a sustainability certification for the destination (24%) and Awareness-raising and training of the local population (46%).

Importance versus implementation

The final part of the survey looked at the importance (current and future) as well as the level of implementation of the GSTC destination criteria. The overview of the mean results for each criterion regarding current and future importance and the current level of implementation can be found in .

Current importance: First, the aspects that scored highest (mean) in current importance are Intangible heritage (4.16), Access for all (3.95), Destination management strategy and action plan (3.83), Low-impact transportation (3.56) and Wildlife interaction (3.38). The criteria with the lowest importance are Light and noise pollution (2.70), Risk and crisis management (2.77), Visitor engagement and feedback (2.84), Solid waste (2.85) and Managing visitor volumes and activities (2.88) as well as Climate change adaptation (2.88) and Monitoring and reporting (2.88).

Current implementation: Second, the aspects which ranked highest concerning current implementation are Intangible heritage (3.89), Access for all (3.43), Destination management strategy and action plan (3.25), Low-impact transportation (2.96) and Wildlife interaction (2.86). They coincide with the aspects that were also rated highest in terms of current importance. This shows that the aspects that are considered most important also have the highest level of implementation relative to each other. The aspects that are least fulfilled are Monitoring and reporting (1.92), Light and noise pollution (1.93), Visitor engagement and feedback (2.00), Protection of sensitive environments (2.01) and Risk and crisis management (2.08).

Future importance: Third, looking into the future, the respondents were asked to indicate whether they considered the criteria to strongly increase (5) or strongly decrease. Therefore, everything above 3 indicates an increase; the higher the mean, the more strongly this increase is evaluated. Considering the temporal change in importance of the different criteria, a general increasing trend towards the future can be observed. This indicates the respondent’s belief that the sustainability topics will gain in importance in the future (be it for political, regulatory or demand reasons). The criteria Destination management strategy and action plan (4.23), Intangible heritage (4.19), Low-impact transportation (4.08), Destination management responsibility (4.03) and Access for all (4.01) are considered to increase the most in the future. The currently rather low ranked criteria in terms of importance Climate change adaptation (3.84), as well as Managing visitor volumes and activities (3.77) and Monitoring and reporting (3.75) are considerably more important in the future (in the top ten ranking regarding increase in importance). The criteria that showed the lowest increase in importance in the future are Risk and crisis management (3.23), Light and noise pollution (3.27), Protection of cultural assets (3.45), Visitor management at cultural sites (3.48) and Visitor engagement and feedback (3.49).

Table 3. Overview of means regarding current and future importance and current implementation.

Throughout all three asked dimensions, the criteria Visitor engagement and feedback and Light and noise pollution consistently ranked among the lowest means, whereas the criteria Destination management strategy and action plan, Access for all and Intangible heritage consistently ranked among the highest.

Furthermore, the hypothesis regarding importance and implementation is that even though the different criteria are considered important and even more important in the future, the current level of implementation does not reflect this in the same intensity. Therefore, a paired sample t-test analysis was made (at a significance level of 0.95). The indicated importance today was compared with the actual level of implementation for each evaluated GSTC criteria (details in Table A1) to validate that the implementation is at a lower intensity than the considered importance. Doing so, the difference between the mean of the level of the attributed importance is compared to the mean level of implementation. Table A1 shows that all aspects are consistently rated higher in their importance than they are already implemented. The results of the paired t-test analysis confirm the statistical significance of these differences. The effects of these differences are of medium size (Cohen’s d between 0.5 and 0.8); only the criteria Protection of cultural assets and Intangible heritage show a small effect size.

Discussion

Role and responsibility

The topic of sustainability is becoming an increasingly important aspect in the destination development of the surveyed Alpine DMOs. This research addresses the important question of who should take responsibility for sustainable tourism development. Previous studies on the role of DMOs demonstrate that they are capable to create a sustainable vision for destination and strategically position them in the market, centralise knowledge management and monitor solutions (Bonzanigo et al., Citation2016; Morrison, Citation2019; Mutana & Mukwada, Citation2017). This survey illustrates a certain strategic embeddedness as 61% indicate that their mandate integrates a sustainable orientation. Regarding the different tasks, the development and implementation of an overarching destination sustainability strategy is consequently seen most likely as the main responsibility. This emphasises the initially described trend of DMOs moving from a pure marketing organisation towards managing a destination (UNWTO, Citation2019), giving it a strategic vision for the future. However, a majority decline when asked if they are capable to be a sustainability leader within their destination. Even though the awareness for the issue is given and certain aspects are even anchored in their strategy and mandate, there still seems to be lack of translating it into practice. When asking for those reasons, a general lack of financing, time, and personnel resources were mentioned. A possible solution could be to better embed these tasks into the existing job description of the employees or even create a position responsible for sustainable development. This would allow having a person on the team who has the promotion of sustainability within the destination in their job description and therefore has the ability and goal to continuously integrate sustainability aspects into a variety of projects. This is also often a mandatory step in many certification programmes for destinations or national sustainability initiatives (e.g. TourCert, Green Destinations, Green Scheme of Slovenian Tourism, Sustainable Travel Finland) and helps to counteract the capacity issue to deal with sustainability in the operative daily business.

Further, it should be highlighted that a lack of urgency, know-how or suitable political frameworks seem only to be secondary reasons. Thus, this research shows that awareness is present, and sustainability is increasingly being integrated, at least at a strategic level, into destination development. However, the lack of financial and human resources currently hinders a comprehensive operational implementation, which needs to be addressed more decisively by DMOs, for example, by appointing sustainability coordinators in the destinations. Also, a further transition from pure marketing to management organisation might give the DMOs official capacities to act as a changemaker within a destination. Given current tourism developments and increasing political pressure regarding internationally agreed sustainability goals, a sustainable orientation will sooner or later become an essential part of a destination’s development. Furthermore, there are also first-mover destinations in the Alpine region that are already in the process of holistically implementing a sustainable destination development strategy and are using this progress in their clear positioning towards their guests. As sustainable tourism offerings are also increasingly desired by guests, it can be advantageous to be among the destinations that intend to offer a credible sustainable tourism offering. The current pandemic has shown in various surveys of travellers that the topic of sustainability has gained in importance and will also play an increasingly important role in future booking intentions (cf. booking.com’s sustainable travel report 2021).

Finally, the discussion on responsibility also shows the interconnectedness with other tourism stakeholders. A majority of 61% assign the main responsibility for sustainable development to other stakeholders, and only 39% see the DMOs themselves in that role. From their perspective, political authorities (29%) as well as local tourism operator (23%) are seen in the main role. This illustrates the described complexity of sustainable tourism governance in the literature and emphasises the call for further discussions on the roles, synergies and co-responsibilities from Roxas et al. (Citation2020). Surely, this also depends on the specific organisation of tourism in the respective destination and needs to take those features into consideration. It would be helpful to expand on this issue in a qualitative research approach that investigates different organisational settings to get a better understanding of the interplay between these crucial stakeholders to remove barriers to a sustainable tourism transition.

Importance versus implementation

This research gives an indication about the DMOs focus on sustainable development. Aspects like accessibility, low-impact transportation, sustainability-oriented management but also socio-cultural aspects like intangible heritage are at the forefront and comparably progressed in terms of implementation. Interestingly the criterion Risk and crisis management ranks second to last in terms of current importance and although it is increasing in importance, this increase is smaller compared to the other criteria, so that it even ranks last in terms of future importance. Given that the survey took place amid the pandemic in June and July 2020, this seems rather surprising, as one might have expected a heightened awareness of risk management based on current experience. However, it must also to be considered that in the summer of 2020, many non-pharmaceutical interventions were reduced, and domestic tourism increased in these mountain destinations due to the satisfaction of a pandemic-related need for nature and space. Thus, the feeling of having already overcome the worst could well have played a role in answering the questions. Another interesting result is the Visitor engagement and feedback criterion which consistently ranks among the lowest in all three dimensions surveyed. This criterion where general satisfaction and quality aspects are being monitored seems to be one of the rather typical KPIs use in tourism, such as other socio-economic indicators like overnight, arrival and country of origin statistics and would be expected to rank higher in importance. Especially, since the resident engagement and feedback criterion is, on average, ranked higher. A similar pattern of consistent low ranks emerges for Light and noise pollution, but this is not surprising considering that the destinations under study are more remote natural destinations that do not have to deal with these issues in the same ways as, for example, urban destinations. In general, it can be stated that all the four dimensions of the GSTC destination criteria catalogue are being considered and there is no strong indication that the DMOs focus on just one sustainability dimension. Therefore, the holistic concept of the sustainability seems to be acknowledged.

Based on the results of this study, the DMOs are not yet fully capable of fulfilling the various sustainability criteria. The operationalisation of these criteria will require further strategic discussions and decisions at DMO and destination level on how the DMO can embrace and achieve these new responsibilities where the expansion of the mandate and the provision of the necessary resources will become necessary to adequately cope with this task in the medium and long term.

Moreover, there is a clear and statistically significant gap between the level of importance that the DMOs attribute to the different sustainability criteria and how they are fulfilling these already. The level of importance is consistently higher than the level of fulfilment. This illustrates an awareness of the importance of sustainability and looking into the future, this importance is, on average, assessed even higher than today, however, the implementation is lacking behind. This gives an indication to a possible intention/attitude-behaviour gap, a phenomenon that is observed on individual environmental/sustainable consumption behaviour in various consumer good areas (e.g. Claudy et al., Citation2013; Haider et al., Citation2019; Park & Lin, Citation2020; Vermeir & Verbeke, Citation2006). Finally, when discussing the importance and implementation of individual GSTC determination criterion, it is important to mention again that only a selection of the most important criteria was included in the survey, trading off comprehensiveness versus early termination rates of participants due to length.

Conclusion and further research possibilities

This study explores the attributed importance and level of implementation of the internationally renowned GSTC destination criteria for sustainable tourism development. The focus is put on Alpine destinations as there the various demanding tasks ranging from ecological challenges like climate change to social challenges of seclusion, cultural heritage, and local value creation are increasingly noticeable, making a progressive sustainability transformation necessary. The DMOs play a strategic and multiplying role in the development plans of a destination and were the study object of this research. The literature review has shown that the knowledge about the sustainability assessment (importance and implementation) from the perspective of such an influential tourism stakeholder is currently limited. This study has confirmed the hypothesis that although the importance of sustainability has been recognised and to some extent already integrated into the strategic orientation, the current level of implementation consistently lags. This means that the apparent attitude-behaviour gap, as widely discussed on an individual level regarding sustainable behaviour (e.g. Antimova et al., Citation2012; Claudy et al., Citation2013; Haider et al., Citation2019; Park & Lin, Citation2020; Vermeir & Verbeke, Citation2006) also plays a role in the context of institutional actors. Further research should address this and investigate possible measures to reduce this gap and increase the implementation of sustainable practices. The sooner this transition is made possible, the more advantageous it is also in terms of strengthening the destination’s positioning. Especially, as the respondents indicated a significant increase in the importance of these issues.

Even though the overall sample is above the critical threshold of 30 participants and allows for a valuable overall analysis of the issue, the respective sample size when zooming into different countries is too small to carry out a statistically sound analysis. Thus, for future research, it would be interesting to investigate country-specific characteristics or even develop some sort of additional clustering of destinations for the analysis (e.g. main seasonality, customer segments, destination size, destination type (e.g. lake destinations, skier or non-skier destinations), or the governance structures) to better understand the current implementation of sustainability in Alpine tourism (e.g. specific product development, the transfer of the sustainability development in the destination’s marketing, the customer recognition, or the direct and indirect impacts of sustainability certifications). These additional insights are valuable to inform suitable policy and regulatory interventions to support and incentivize a sustainable transition in Alpine tourism destinations.

The findings of this explorative study also highlight the need for more concrete action by destination managers. Although it is commendable that a majority have included sustainability in their strategic considerations, concrete implementation evidence is still lacking. Destination managers need to be aware of their crucial role in planning and positioning a destination and motivating businesses to implement sustainability measures for a more sustainable future for Alpine destinations. It might be helpful to join regional or national sustainable development initiatives to profit from this knowledge and experience dissemination. Furthermore, the involvement of local stakeholders in a destination action plan through committees or other collaborative modes is key to bring about a broad-based sustainability transition.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Antimova, R., Nawijn, J., & Peeters, P. (2012). The awareness/attitude-gap in sustainable tourism: A theoretical perspective. Tourism Review, 67(3), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371211259795

- Beritelli, P., Buffa, F., & Martini, U. (2015). The coordinating DMO or coordinators in the DMO?: An alternative perspective with the help of network analysis. Tourism Review, 70(1), 24–42. https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/246673/

- Blackman, D., & Ritchie, B. W. (2008). Tourism crisis management and organizational learning. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(2–4), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v23n02_04

- Bonzanigo, L., Giupponi, C., & Balbi, S. (2016). Sustainable tourism planning and climate change adaptation in the Alps: A case study of winter tourism in mountain communities in the Dolomites. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(4), 637–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1122013

- Bramwell, B. (2011). Governance, the state and sustainable tourism: A political economy approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.576765

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.580586

- Bricker, K. S., & Schultz, J. (2011). Sustainable tourism in the USA: A comparative look at the global sustainable tourism criteria. Tourism Recreation Research, 36(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2011.11081668

- Byrd, E. T. (2007). Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Review, 62(2), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605370780000309

- Claudy, M. C., Peterson, M., & O’Driscoll, A. (2013). Understanding the attitude-behavior gap for renewable energy systems using behavioral reasoning theory. Journal of Macromarketing, 33(4), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146713481605

- Crouch, G. I. (2011). Destination competitiveness: An analysis of determinant attributes. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362776

- Derkx, B., & Glasbergen, P. (2014). Elaborating global private meta-governance: An inventory in the realm of voluntary sustainability standards. Global Environmental Change, 27, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.016

- Dornier, R., & Mauri, C. (2018). Overview: Tourism sustainability in the alpine region: The major trends and challenges. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 10(2), 136–139. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-12-2017-0078

- dos Anjos, F. A., & Kennell, J. (2019). Tourism, governance and sustainable development. Sustainability, 11(16), 4257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164257

- Font, X., & Harris, C. (2004). Rethinking standards from green to sustainable. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 986–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.001

- Font, X., & Sallows, M. (2002). Setting global sustainability standards: The Sustainable Tourism Stewardship Council. Tourism Recreation Research, 27(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2002.11081353

- Gobiet, A., Kotlarski, S., Beniston, M., Heinrich, G., Rajczak, J., & Stoffel, M. (2014). 21st century climate change in the European Alps – A review. The Science of the Total Environment, 493, 1138–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.050

- GSTC (Ed.). (2019). GSTC destination criteria: Version 2.0. Global Sustainable Tourism Council.

- GSTC. (2021, September 22). GSTC history. https://www.gstcouncil.org/about/gstc-history/

- GSTC. (2022a). GSTC criteria overview. https://www.gstcouncil.org/gstc-criteria/

- GSTC. (2022b). About the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC). https://www.gstcouncil.org/about/

- Haid, M., Albrecht, J. N., & Finkler, W. (2021). Sustainability implementation in destination management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 312, 127718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127718

- Haider, S. W., Zhuang, G., & Ali, S. (2019). Identifying and bridging the attitude-behavior gap in sustainable transportation adoption. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 10(9), 3723–3738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-019-01405-z

- Hall, C. M. (2011). A typology of governance and its implications for tourism policy analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 437–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.570346

- Hall, C. M., & Veer, E. (2016). The DMO is dead. Long live the DMO (or, why DMO managers don’t care about post-structuralism). Tourism Recreation Research, 41(3), 354–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2016.1195960

- Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2014). Sustainability in the global hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2012-0180

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.05.012

- Klintman, M. (2012). Issues of scale in the global accreditation of sustainable tourism schemes: Toward harmonized re-embeddedness? Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 8(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2012.11908085

- Kuščer, K., Mihalič, T., & Pechlaner, H. (2017). Innovation, sustainable tourism and environments in mountain destination development: A comparative analysis of Austria, Slovenia and Switzerland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4), 489–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1223086

- Marty, C. (2008). Regime shift of snow days in Switzerland. Geophysical Research Letters, 35(12), L12501. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL033998

- Mihalič, T., Šegota, T., Knežević Cvelbar, L., & Kuščer, K. (2016). The influence of the political environment and destination governance on sustainable tourism development: A study of Bled, Slovenia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(11), 1489–1505. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1134557

- Minguzzi, A. (2006). Destination competitiveness and the role of destination management organization (DMO): An Italian experience. In L. Lazzeretti & C. S. Petrillo (Eds.), Tourism local systems and networking (pp. 211–222). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080462387-23

- Morgan, N. (2012). Time for ‘mindful’ destination management and marketing. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1–2), 8–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.07.003

- Morrison, A. M. (2019). Marketing and managing tourism destinations (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Mountain Research Initiative EDW Working Group. (2015). Elevation-dependent warming in mountain regions of the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(5), 424–430. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2563

- Mutana, S., & Mukwada, G. (2017). An exploratory assessment of significant tourism sustainability indicators for a Montane-based route in the Drakensberg Mountains. Sustainability, 9(7), 1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071202

- Nguyen, T. Q. T., Young, T., Johnson, P., & Wearing, S. (2019). Conceptualising networks in sustainable tourism development. Tourism Management Perspectives, 32, 100575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100575

- Niñerola, A., Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V., & Hernández-Lara, A.-B. (2019). Tourism research on sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 11(5), 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051377

- Nunkoo, R. (2017). Governance and sustainable tourism: What is the role of trust, power and social capital? Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(4), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.10.003

- Park, H. J., & Lin, L. M. (2020). Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. Journal of Business Research, 117, 623–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.025

- Paunović, I., & Jovanović, V. (2017). Implementation of sustainable tourism in the German Alps: A case study. Sustainability, 9(2), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020226

- Paunović, I., & Jovanović, V. (2019). Sustainable mountain tourism in word and deed: A comparative analysis in the macro regions of the Alps and the Dinarides. Acta Geographica Slovenica, 59(2), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.3986/AGS.4630

- Pearce, D. G. (2016). Destination management: Plans and practitioners’ perspectives in New Zealand. Tourism Planning & Development, 13(1), 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2015.1076511

- Pechlaner, H., Zacher, D., Eckert, C., & Petersik, L. (2019). Joint responsibility and understanding of resilience from a DMO perspective – An analysis of different situations in Bavarian tourism destinations. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(2), 146–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-12-2017-0093

- Pérez Guilarte, Y., & Lois González, R. C. (2018). Sustainability and visitor management in tourist historic cities: The case of Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 13(6), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1435665

- Pulido-Fernández, J. I., & La Pulido-Fernández, M. d. C. (2018). Proposal for an indicators system of tourism governance at tourism destination level. Social Indicators Research, 137(2), 695–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1627-z

- Reinhold, S., Laesser, C., & Beritelli, P. (2015). 2014 st. Gallen consensus on destination management. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(2), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.03.006

- Rivera, J., Pastor, R., & Gomez Punzon, J. (2021). The impact of the Covid-19 on the perception of DMOs about the sustainability within destinations: A European empirical approach. Tourism Planning & Development, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.1914149

- Rogora, M., Frate, L., Carranza, M. L., Freppaz, M., Stanisci, A., Bertani, I., Bottarin, R., Brambilla, A., Canullo, R., Carbognani, M., Cerrato, C., Chelli, S., Cremonese, E., Cutini, M., Di Musciano, M., Erschbamer, B., Godone, D., Iocchi, M., Isabellon, M., … Matteucci, G. (2018). Assessment of climate change effects on mountain ecosystems through a cross-site analysis in the Alps and Apennines. The Science of the Total Environment, 624, 1429–1442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.155

- Roxas, F. M. Y., Rivera, J. P. R., & Gutierrez, E. L. M. (2020). Mapping stakeholders’ roles in governing sustainable tourism destinations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.09.005

- Steiger, R., Scott, D., Abegg, B., Pons, M., & Aall, C. (2019). A critical review of climate change risk for ski tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(11), 1343–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1410110

- Stoker, G. (1998). Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal, 50(155), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2451.00106

- UNWTO. (2005). Making tourism more sustainable: A guide for policy makers. United Nations Environment Programme, Division of Technology, Industry and Economics; World Tourism Organization.

- UNWTO. (2019). UNWTO guidelines for institutional strengthening of Destination Management Organizations (DMOs): Preparing DMOs for new challenges. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284420841

- UNWTO. (2020). One planet vision for a responsible recovery of the tourism sector. https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-06/one-planet-vision-responsible-recovery-of-the-tourism-sector.pdf

- Vermeir, I., & Verbeke, W. (2006). Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 19(2), 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-005-5485-3

- Volgger, M., & Pechlaner, H. (2014). Requirements for destination management organizations in destination governance: Understanding DMO success. Tourism Management, 41, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.09.001

- Wagenseil, U., & Zemp, M. (2016). Sustainable tourism in mountain destinations: The perceived and actual role of a destination management organization. In B. Koulov & G. Zhelezov (Eds.), Sustainable mountain regions: Challenges and perspectives in Southeastern Europe (pp. 137–148). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27905-3_10

- Winkler, M., Lamprecht, A., Steinbauer, K., Hülber, K., Theurillat, J.P., Breiner, F., Choler, P., Ertl, S., Gutiérrez Girón, A., Rossi, G., Vittoz, P., Akhalkatsi, M., Bay, C., Benito Alonso, J.L., Bergström, T., Carranza, M. L., Corcket, E., Dick, J., Erschbamer, B., … Pauli, H. (2016). The rich sides of mountain summits – A pan-European view on aspect preferences of alpine plants. Journal of Biogeography, 43(11), 2261–2273. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12835

- Zahra, A. L. (2011). Rethinking regional tourism governance: The principle of subsidiarity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.576764

Appendix

Table A1. Paired sample t-test statistics: current implementation vs. current importance.